Abstract

Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC), the most common primary liver cancer, is a significant contributor to worldwide cancer-related deaths. Various medical imaging techniques, including computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, and ultrasound, play a crucial role in accurately evaluating HCC and formulating effective treatment plans. Artificial Intelligence (AI) technologies have demonstrated potential in supporting physicians by providing more accurate and consistent medical diagnoses. Recent advancements have led to the development of AI-based multi-modal prediction systems. These systems integrate medical imaging with other modalities, such as electronic health record reports and clinical parameters, to enhance the accuracy of predicting biological characteristics and prognosis, including those associated with HCC. These multi-modal prediction systems pave the way for predicting the response to transarterial chemoembolization and microvascular invasion treatments and can assist clinicians in identifying the optimal patients with HCC who could benefit from interventional therapy. This paper provides an overview of the latest AI-based medical imaging models developed for diagnosing and predicting HCC. It also explores the challenges and potential future directions related to the clinical application of AI techniques.

1 Introduction

Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC), the most common primary liver malignancy, is linked to high mortality rates and stands as a leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide (1). Accurate diagnosis and staging of HCC are crucial for improving patient survival rates and treatment outcomes. However, early diagnosis of HCC presents a significant challenge, especially for individuals with chronic liver disease. A notable characteristic of liver cancer is its strong association with liver fibrosis, with over 80% of hepatocellular carcinomas (HCCs) developing in fibrotic or cirrhotic livers (2). This indicates that liver fibrosis plays a vital role in the liver’s premalignant environment.

Medical imaging techniques, including Computed Tomography (CT), Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), and Ultrasound (US), play an essential role in the diagnosis and staging of HCC, supplementing clinical findings, biological markers, and blood tests. CT scans provide detailed cross-sectional images of the liver, aiding in the identification and characterization of tumors (3). MRI offers superior soft tissue contrast, making it invaluable for assessing the extent of liver cancer (4). US, a non-invasive and cost-effective imaging modality, can detect liver tumors by generating liver images using sound waves (5). However, each of these imaging methods has its limitations. For instance, CT scans expose patients to ionizing radiation, potentially heightening the risk of radiation-induced cancer. Moreover, CT scans can be expensive and less accessible in certain healthcare settings. While MRI can produce high-quality images, it can be time-consuming and may not be suitable for patients with claustrophobia or those with metal implants. US has limitations in image quality, particularly in patients with obesity or excessive intestinal gas. Recently, advanced MRI techniques, such as MR Elastography (MRE) and gadoxetic acid-enhanced MRI, have been introduced for liver imaging. These techniques provide high-resolution images without the harmful effects of radiation (6). MRE measures the stiffness of liver tissue, which can assist in differentiating between benign and malignant liver tumors. Gadoxetic acid-enhanced MRI offers dynamic imaging of the liver and can enhance the detection and characterization of HCC.

Diagnosing HCC poses significant challenges. These challenges arise from the prevalence of typical radiological features that are common to other liver tumors or benign conditions. Such similarities in imaging characteristics can lead to misdiagnosis or delayed diagnosis. As a result, patients with liver lesions exhibiting these typical features may require histological confirmation or rigorous monitoring to ensure accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment.

In recent years, the potential of Artificial Intelligence (AI) techniques in diagnosing HCC has been the subject of extensive research. These techniques have been explored for various purposes such as detecting and evaluating HCC, facilitating treatment, and predicting treatment response (7–13). Numerous studies have investigated the use of AI models in conjunction with different modalities, including electronic health record (EHR) reports, clinical parameters, biological markers, and blood test results, for diagnosing liver cancer (14, 15). AI techniques have emerged as powerful tools capable of extracting valuable insights from voluminous EHRs and developing multimodal AI methods. These methods provide a more comprehensive and accurate depiction of the liver’s internal structure and function.

While many researchers have shown interest in exploring the potential of AI techniques in liver cancer research, there remains a gap in comprehensively evaluating the implementation of single-modal and multi-modal AI techniques for diagnosing HCC. This study aims to bridge this gap by providing a comprehensive review of the most recently developed AI-based techniques that utilize both single and multi-modal data for diagnosing HCC. AI-based techniques hold the potential to enhance early diagnosis, improve diagnostic accuracy, and improve treatment outcomes for patients with HCC. This pivotal area of research could lead to significant advancements in liver cancer diagnosis and prediction.

2 Methodology and materials

This research explores the application of AI methodologies in diagnosing and prognosticating primary liver cancer, specifically HCC. The objective is to encapsulate the latest and most relevant discoveries in this rapidly evolving field.

A thorough literature review was conducted using databases such as PubMed, Scopus, Semantic Scholar, IEEEXplore, and Web of Science, up until March 31, 2024. During this process, several key terms such as “artificial intelligence”, “deep learning”, “machine learning”, “liver cancer”, “hepatocellular carcinoma”, “multi-modal”, “medical imaging”, “US”, “CT”, and “MRI” were searched in the title and/or abstract or all field. References from relevant articles were examined to identify additional qualifying publications.

An expert review of the eligible literature was carried out, and the most informative and pertinent citations were chosen for inclusion. The studies selected were those that integrated AI techniques with medical imaging datasets, including US, CT, and MRI, in conjunction with Electronic Health Records (EHR) and clinical parameters. Studies that did not utilize medical imaging techniques or AI models specifically targeting primary liver cancer were excluded.

The search was confined to peer-reviewed articles, conference proceedings, dissertations, and book chapters published in English from January 2010 to March 2024. These publications were retrieved, screened, and reviewed by the authors. One researcher then undertook the data extraction, focusing on the methods and results of each study.

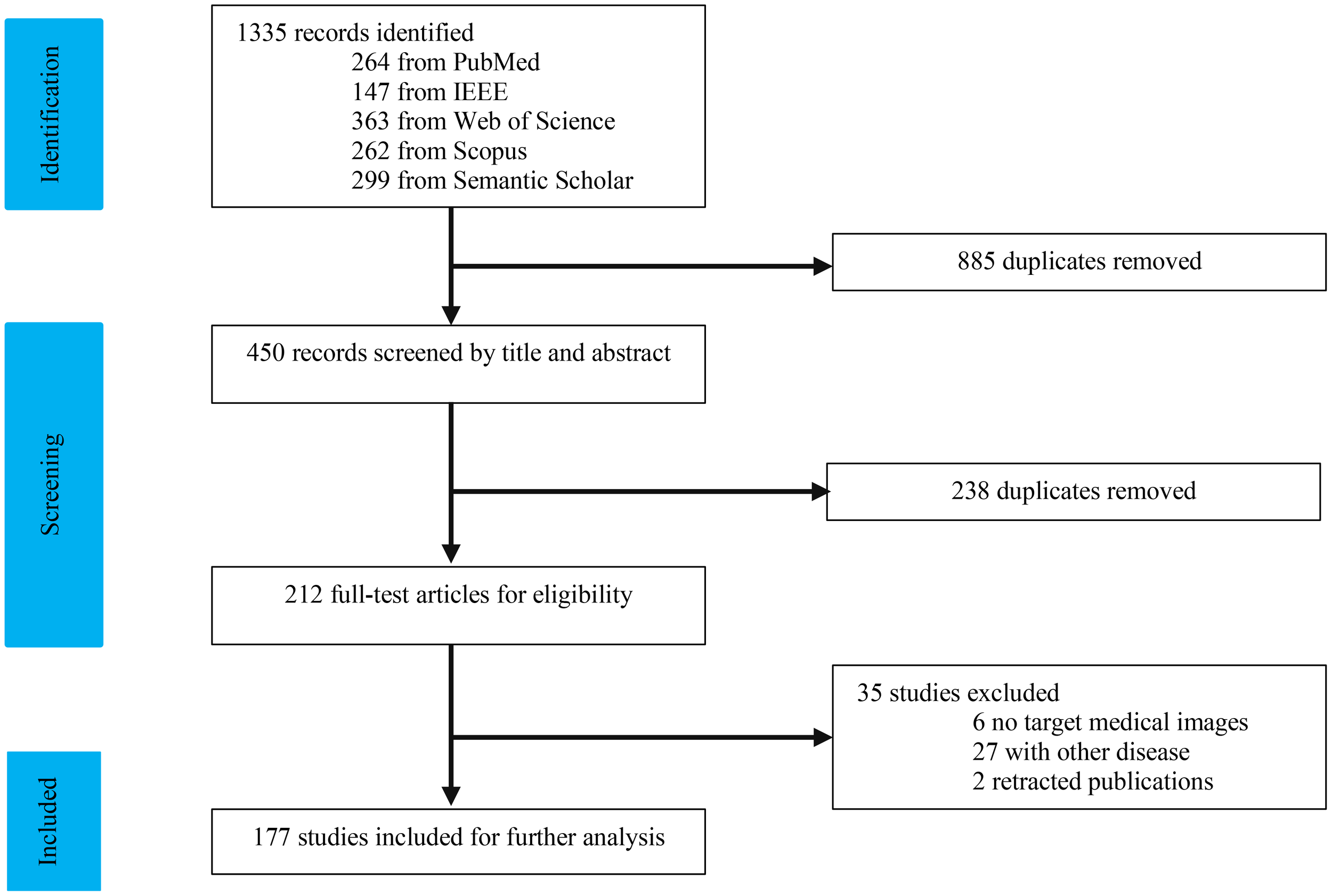

As depicted in Figure 1, our study selection process began with 1334 records. After removing 885 duplicates, we screened 450 records. The title and abstract screening led to the exclusion of 240 studies, leaving 210 for full-text review. Following a comprehensive evaluation, 177 articles (7, 16–186) were deemed suitable for this study. We categorized the modalities into four groups: US (n = 34), CT (n = 95), MRI (n = 34), and multi-modal (n=19). The characteristics of the included studies are detailed in Tables 1–10.

Figure 1

Flowchart of study selection.

Table 1

| Ref | Year | AI Model | US Method | Task | Dataset | AUC | Accuracy | Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (17) | 2010 | FSVM | B-mode US | Classify benign and malignant liver lesions | 200 images | 0.984 | 0.97 | 1 | 0.955 |

| (17) | 2010 | FSVM | B-mode US | Classify benign and malignant liver lesions | 450 images | 0.971 | 0.951 | 0.92 | 0.955 |

| (18) | 2011 | Two-step neural network | B-mode US | Classify FLLs | 111 images (88 patients) |

~ | 0.864 | ~ | ~ |

| (18) | 2011 | Two-step neural network | B-mode US | Detect FLLs | 111 images (88 patients) |

~ | 0.903 | ~ | ~ |

| (7) | 2014 | NNE | B-mode US | Diagnosis of FLLs | 108 patients | ~ | 0.95 | ~ | ~ |

| (19) | 2015 | ANN | B-mode US | Diagnosis of FLLs | 115 patients | ~ | >0.96 | ~ | ~ |

| (20) | 2017 | ANN | B-mode US | Diagnosis of FLLs | 110 images | ~ | 0.972 | 0.98 | 0.957 |

| (21) | 2018 | SVM | B-mode US | Classify benign and malignant liver lesions | 189 images (94 patients) |

~ | 0.966 | 0.969 | 0.998 |

| (22) | 2019 | Supervised DL | B-mode US | Detection and characterization of FLLs as benign and malignant |

Training set: 367 images (367 patients), Test set: 177 patients |

Training: mean ACU:0.935 for detection, mean ACU: 0.916 for characterization, Test: mean ACU: 0.891 for detection |

~ | ~ | ~ |

| (23) | 2020 | CNN | B-mode US | Characterization of FLLSs as benign or malignant |

Training: 16500 images (1446 Patients), Internal validation: 4125 images (369 patients), External validation: 3718 images (328 patients) |

Training: mean ACU: 0.765~0.925 Internal validation: mean ACU: 0.859~0.966 External validation: mean ACU: 0.750~0.924 |

~ | ~ | ~ |

| (24) | 2020 | CNN | B-mode US | Differentiate HCC and PAR | GE9 dataset | 0.91 | 0.8484 | 0.8679 | 0.8295 |

| (24) | 2020 | CNN | B-mode US | Differentiate HCC and PAR | GE7 dataset | 0.95 | 0.91 | 0.9437 | 0.8838 |

| (25) | 2021 | LR, k-NN, MLP, RF, SVM |

B-mode US | Characterization of FLLSs as benign or malignant |

114 patients Training: 91, Test:23 |

Mean AUC: 0.737~0.816 | Mean accuracy: 0.729~0.843 | ~ | ~ |

| (26) | 2021 | DL | B-mode US | Diagnosis of FLLs | 4309 images (3873 patients) | 0.947 | 0.822 | 0.867 | 0.987 |

| (27) | 2021 | CNN | B-mode US | Diagnosis of FLLs | 40397 images (3847 patients) | ~ | 0.949 | 0.736 | 0.978 |

| (28) | 2021 | CNN | B-mode US | Classify benign and malignant liver lesions | 911 images (596 patients) | 0.860 | 0.84 | 0.87 | 0.78 |

| (29) | 2021 | CNN | Endoscopic US | Classify benign and malignant liver lesions | 210685 images (256 patients) | 0.861 (image), 0.904 (video) | ~ | 0.9(image), 1 (video) | 0.71(image), 0.80(video) |

| (30) | 2021 | SVM | B-mode US | Differentiate HCC and ICC | 226 patients, Training: 149 Test: 38 External validation: 39 |

Training: 0.840~0.975, Test: 0.711~0.936, External validation: 0.730~0.874 |

Training: 0.7047~0.8926, Test:: 0.7105~0.8684, External validation: 0.6923 ~0.8718 |

Training: 0.7742~0.9677, Test: 0.7~0.9, External validation: 0.6667~0.8887 |

Training: 0.6864 ~0.8729, Test: 0.7143 ~0.8571, External validation: 0.6667~0.8667 |

| (31) | 2021 | SVM | B-mode US | Prediction of pathological grading of HCC | 193 patients Training: 128 Test: 32 External validation: 33 |

Training: 0.788~0.977, Test: 0.72~0.874, External validation: 0.77~0.849 |

Training: 0.7422~0.9219, Test:: 0.6875~0.8438, External validation: 0.6667 ~0.8182 |

Training: 0.6471~0.902, Test: 0.5714~0.8571, External validation: 0.75 |

Training: 0.8052 ~0.9351, Test: 0.72 ~0.84, External validation: 0.619~0.8571 |

| (32) | 2022 | CNN | B-mode US | Diagnosis of FLLs | 70950 images | ~ | 0.934 | 0.675 | 0.96 |

| (33) | 2022 | DL | B-mode US | Diagnosis of HCC | 407 patients | 0.936 | 0.864 | 0.96 | 0.769 |

| (34) | 2022 | ResNet18 | B-mode US | Differentiate and predict HCC | 513 patients | 0.855(training), 0.709 (validation) | ~ | ~ | ~ |

| (35) | 2023 | CNN | Quantitative US | Diagnosis of hepatic steatosis | 173 patients | 0.97 | ~ | 0.90 | 0.91 |

| (36) | 2012 | ANN | CEUS | Diagnosis of FLLs | 112 patients | ~ | 0.9442 | 0.932 | 0.897 |

| (37) | 2014 | DL | CEUS | Diagnosis of FLLs | 22 patients | ~ | 0.8636 | 0.8333 | 0.8750 |

| (38) | 2015 | SVM | CEUS | Diagnosis of FLLs | 52 video sequences | ~ | 0.903 | 0.931 | 0.869 |

| (39) | 2017 | SVM | CEUS | Classify benign and malignant liver lesions | 98 patients | 0.918 | 0.94 | 87.1 | |

| (40) | 2018 | DCCA -MKL | CEUS | Classify benign and malignant liver lesions | 93 patients | 0.953 | 0.9041 | 0.9356 | 0.8689 |

| (41) | 2018 | ANN | CEUS | Differentiating benign from malignant liver lesions |

106 lesions | 0.829~0.883 | 0.80~0.811 | ||

| (42) | 2019 | 3D CNN | CEUS | Classify aHCC and FNH | 4420 images | ~ | 0.931 | 0.945 | 0.936 |

| (43) | 2020 | SVM | CEUS | Differentiation between aHCC and FNH | 257 images | 0.944 | ~ | 0.9476 | 0.9362 |

| (44) | 2021 | DL | CEUS | Classify five types of FLLs | 273 video files (91 patients) |

~ | 0.88 | ~ | ~ |

| (45) | 2021 | CNN | CEUS | Classify benign and malignant liver lesions | 363 patients | 0.934 | 0.91 | 0.927 | 0.851 |

| (46) | 2021 | SVM | CEUS | Preoperative histological grading | 235 HCC lesions: 65 high grade and 170 low grade lesions |

0.665~0.785 | ~ | ~ | ~ |

| (47) | 2022 | ML | CEUS | Classify benign and malignant liver lesions | 87 images (72 patients) |

0.840 | 0.84 | 0.76 | 0.92 |

| (48) | 2024 | CNN-LSTM | CEUS | Classify benign and malignant liver lesions | 440 patients | 0.91 | ~ | 0.95 | 0.7 |

| (48) | 2024 | 3D-CNN | CEUS | Classify benign and malignant liver lesions | 440 patients | 0.88 | ~ | 0.96 | 0.55 |

| (48) | 2024 | ML-TIC | CEUS | Classify benign and malignant liver lesions | 440 patients | 0.78 | ~ | 0.96 | 0.21 |

AI-based US approaches for HCC diagnosis.

aHCC, a typical HCC; AUC, area under the curve; CNN, convolutional neural network; DCCA –MKL, deep canonical correlation analysis and multiple kernel learning; DL, deep learning; FNH, focal nodular hyperplasia; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; iANN, improved artificial neural network; ML- TIC, machine learning based time-intensity curve; NNE, neural network ensemble; PAR, cirrhotic parenchyma; SVM, support vector machine; US, ultrasound.

Table 2

| Ref | Year | AI Model | Imaging method | Task | Dataset | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (49) | 2015 | Model based Shape Constraints and Deformable Graph Cut | CT | Liver segmentation | 3DIRCADb | VOE=9.15 |

| (49) | 2015 | Model based Shape Constraints and Deformable Graph Cut | CT | Liver segmentation | Sliver07 | VOE=62.4 |

| (53) | 2017 | CNN + MRFs | CT | Liver segmentation | Hospital dataset | Dice= 0.83 |

| (54) | 2017 | U-Net | CT | Liver segmentation | 3DIRCADb | Dice=0.923, VOE=14.21 |

| (55) | 2018 | Faster R-CNN | CT | Liver segmentation | SLIVER07 | VOE = 5.06,VD = 0.09 |

| (55) | 2018 | Faster R-CNN | CT | Liver segmentation | 3DIRCADb | VOE = 0.0867, VD = 0.57 |

| (56) | 2018 | V-net | CT | Liver segmentation | 3DIRCADb | Dice=0.874, VOE=21.85 |

| (56) | 2018 | V-net | CT | Liver segmentation | SLIVER07 | Dice=0.872, VOE=21.15 |

| (57) | 2018 | H Dense UNet | CT | Liver segmentation | 3DIRCADb | Dice=0.930, VOE=12.87 |

| (57) | 2018 | H Dense UNet | CT | Liver segmentation | SLIVER07 | Dice=0.927, VOE=13.29 |

| (58) | 2018 | U-net+ GAN | CT | Liver segmentation | 3DIRCADb | Dice= 0.94 |

| (59) | 2019 | Channel-UNet | CT | Liver segmentation | 3DIRCADb | Dice= 0.984 |

| (60) | 2020 | BS U-Net | CT | Liver segmentation | LiTS | Dice= 0.961 |

| (61) | 2020 | RA U-Net | CT | Liver segmentation | 3DIRCADb | Dice= 0.830, VOE = 4.5 |

| (61) | 2020 | RA U-Net | CT | Liver segmentation | LiTS | Dice= 0.961, VOE = 7.4 |

| (62) | 2020 | Multi-Layer U-Net | CT | Liver segmentation | 3DIRCADb | Dice = 0.9645 |

| (62) | 2020 | Multi-Layer U-Net | CT | Liver segmentation | LiTS | Dice = 0.9638 |

| (63) | 2020 | 3DResUNet | CT | Liver segmentation | 3DIRCADb | Dice = 0.958 |

| (64) | 2020 | CNN | CT | Liver segmentation | Hospital dataset | Dice = 0.949 |

| (65) | 2020 | BATA-Unet | CT | Liver segmentation | MICCAI | Dice=0.9788, VOE=4.5, RVD=0.04%, ASD=0.05mm, MSD=0.08mm |

| (65) | 2020 | BATA-Unet | CT | Liver segmentation | 3DIRCAD | Dice=0.9671, VOE=0.115, RVD=0.08%, ASD=0.14mm, MSD=0.16mm |

| (66) | 2021 | Multi Res U-Net | CT | Liver segmentation | 3DIRCADb | Dice= 0.88 |

| (67) | 2021 | DenseXNet | CT | Liver segmentation | 3DIRCADb | Dice= 0.968 |

| (67) | 2021 | DenseXNet | CT | Liver segmentation | LiTS | Dice= 0.9668 |

| (68) | 2021 | T3scGAN | CT | Liver segmentation | LiTS | Dice= 0.961 |

| (69) | 2021 | 2.5D light-weight nnU-Net | CT | Liver segmentation | LiTS | Dice= 0.962 |

| (70) | 2021 | 2.5D U-Net | CT | Liver segmentation | LiTS | Dice= 0.928 |

| (71) | 2021 | 2.5D P U-Net | CT | Liver segmentation | LiTS | Dice= 0.962 |

| (72) | 2021 | DFS U-Net | CT | Liver segmentation | LiTS | Dice= 0.949 |

| (73) | 2021 | MSN-Net | CT | Liver segmentation | LiTS | Dice= 0.942 |

| (74) | 2021 | U-Net | CT | Liver segmentation | LiTS | Dice=0.9693 for training, Dice=0.9077 for validation, Dice=0.9084 for testing |

| (75) | 2022 | Casecade DL | CT | Liver segmentation | LiTS | Dice= 0.9564, VOE=0.0828 |

| (76) | 2022 | PADLLS | CT | Liver segmentation | SLIVER07 | Dice= 0.957, VOE=0.0814 |

| (76) | 2022 | PADLLS | CT | Liver segmentation | 3DIRCADb | Dice= 0.965, VOE=0.0666 |

| (77) | 2022 | DALU-Net | CT | Liver segmentation | Custom | Dice=0.899 |

| (78) | 2022 | nnU-Net | CT | Liver segmentation | LiTS-IRCAD | global Dice=0.974, |

| (79) | 2023 | SLIC-DGN | CT | Liver segmentation | LiTS17 | Acc=0.991, Dice=0.911, Mean IoU=0.908, Sen= 0.994, Recall=0.994, Prec=0.912 |

| (80) | 2023 | DD-UDA | multi-phase CT | Liver segmentation | LiTS & MPCT-FLLs | IoU=0.823 (PV), IoU=0.811 (ART), IoU=0.800 (NC) |

| (81) | 2023 | RMAU-Net | CT | Liver segmentation | LiTS | Dice=0.9552 |

| (81) | 2023 | RMAU-Net | CT | Liver segmentation | 3D-IRCABb | Dice=0.9697 |

| (82) | 2023 | AIM-Unet | CT | Liver segmentation | CHAOS | Dice=0.9786, Jac=0.9610 |

| (82) | 2023 | AIM-Unet | PET/CT | Liver segmentation | Clinical data | Dice=0.9738, Jac=0.9495 |

| (83) | 2023 | MAD-UNet | CT | Liver segmentation | LiTS17 | Dice=0.9727 |

| (83) | 2023 | MAD-UNet | CT | Liver segmentation | Sliver07 | Dice=0.9752 |

| (83) | 2023 | MAD-UNet | CT | Liver segmentation | 3DIRCADb | Dice=0.9691 |

| (84) | 2023 | Eres-UNet++ | CT | Liver segmentation | LiTS | Acc=0.958, IoU=0.921, F1-Score=0.959, Recall=0.96 |

| (85) | 2023 | Dual-path Network with Swin Transformer Encoding | CT | Liver segmentation | LiTS | Dice=0.962 |

| (86) | 2024 | Spider-UNet | CT | Liver segmentation | LiTS17& 2018 MICCAI | Dice= 0.459 |

| (86) | 2024 | 3D UNet | CT | Liver segmentation | LiTS17& 2018 MICCAI | Dice= 0.54 |

| (86) | 2024 | V-Net | CT | Liver segmentation | LiTS17& 2018 MICCAI | Dice= 0.57 |

| (86) | 2024 | FCN-RNN | CT | Liver segmentation | LiTS17& 2018 MICCAI | Dice= 0.58 |

| (86) | 2024 | LSTM-Unet | CT | Liver segmentation | LiTS17& 2018 MICCAI | Dice=0.59 |

| (86) | 2024 | 3DRes-Unet | CT | Liver segmentation | LiTS17& 2018 MICCAI | Dice= 0.62 |

| (86) | 2024 | MP-UNet | CT | Liver segmentation | LiTS17& 2018 MICCAI | Dice= 0.625 |

| (86) | 2024 | 3D VGN | CT | Liver segmentation | LiTS17& 2018 MICCAI | Dice= 0.649 |

| (86) | 2024 | UMCT | CT | Liver segmentation | LiTS17& 2018 MICCAI | Dice= 0.65 |

| (86) | 2024 | nnU-Net | CT | Liver segmentation | LiTS17& 2018 MICCAI | Dice= 0.675 |

| (86) | 2024 | 3D-GCCN | CT | Liver segmentation | LiTS17& 2018 MICCAI | Dice= 0.70 |

| (86) | 2024 | Improved V-Net | CT | Liver segmentation | LiTS17& 2018 MICCAI | Dice= 0.7253 |

| (87) | 2024 | SADSNet | CT | Liver segmentation | LITS | Dice= 0.9703 |

| (87) | 2024 | SADSNet | CT | Liver segmentation | 3DIRCADb | Dice= 0.9611 |

| (87) | 2024 | SADSNet | CT | Liver segmentation | SLIVER | Dice= 0.9740 |

| (88) | 2024 | SD-Net | CT | Liver segmentation | LiTS | Dice>0.94 |

| (89) | 2024 | LRENet | CT | Liver segmentation | LiTS, 3Dircadb01 & Clinical data | Acc=0.9769, IoU=0.8608, Dice=0.9252 |

| (49) | 2015 | CNN | phase enhanced CT |

Liver tumor segmentation | 26 images | Prec=0.867 |

| (90) | 2016 | End-to-end 3D FCN with CRF | CT | Liver tumor segmentation | SLIVER07 | VOE =5.42, VD =1.75 |

| (51) | 2017 | FCN | CT | Liver tumor segmentation | 2 databases Training: 3809 images |

VOE =15.6~38.2, 8.1~19.1 for each dataset |

| (50) | 2017 | CNN | CT | Liver tumor detection and segmentation | 246 tumors (97 new tumors) |

True positive rate =0.72~0.86 for detection |

| (57) | 2018 | H Dense UNet | CT | Liver tumor segmentation | 3DIRCADb & LiTS | Dice =0.824 |

| (91) | 2018 | FCN | CT | Liver tumor segmentation | Clinical data | True positive rate=0.964 |

| (92) | 2018 | ResNet based SSD | CT | Liver tumor segmentation | Clinical data | Prec =0.533 |

| (93) | 2019 | Nested U-Net | CT | Liver tumor segmentation | LiTS | Pixel accuracy =0.9997, IoU =0.7917, Rand Index=0.9106 |

| (59) | 2019 | Channel-UNet | CT | Liver tumor segmentation | 3DIRCADb | Dice =0.940 |

| (94) | 2019 | 3D Residual U-Net | CT | Liver tumor segmentation | 109 volumes | Dice =0.69, Sen= 0.682 |

| (60) | 2020 | BS U-Net | CT | Liver tumor segmentation | LiTS | Dice =0.569 |

| (61) | 2020 | RA U-Net | CT | Liver tumor segmentation | 3DIRCADb | Dice =0.977, VOE =25.5 |

| (61) | 2020 | RA U-Net | CT | Liver tumor segmentation | LiTS | Dice =0.595, VOE =38.9 |

| (62) | 2020 | Multi-Layer U-Net | CT | Liver tumor segmentation | 3DIRCADb | Dice =0.7334 |

| (62) | 2020 | Multi-Layer U-Net | CT | Liver tumor segmentation | LiTS | Dice =0.7369 |

| (95) | 2020 | SegNet | CT | Liver tumor segmentation | 3DIRCADb | Dice =0.9522 |

| (96) | 2020 | Modified SegNet | CT | Liver tumor segmentation | 3DIRCADb | True positive rate= 0.988 |

| (67) | 2021 | DenseXNet | CT | Liver tumor segmentation | 3DIRCADb | Dice =0.764 |

| (67) | 2021 | DenseXNet | CT | Liver tumor segmentation | LiTS | Dice =0.6911 |

| (70) | 2021 | 2.5D U-Net | CT | Liver tumor segmentation | LiTS | Dice =0.672 |

| (71) | 2021 | 2.5D P U-Net | CT | Liver tumor segmentation | LiTS | Dice =0.735 |

| (68) | 2021 | CGBS-Net | CT | Liver tumor segmentation | Hospital dataset | Dice =0.9641 |

| (45) | 2022 | TransNUNet | CT | Liver tumor segmentation | LiTS | Dice =0.9793 (training), Dice=0.9196 (testing) |

| (45) | 2022 | TransUNet | CT | Liver tumor segmentation | LiTS | Dice=0.9456 (training), Dice=0.8713 (testing) |

| (45) | 2022 | UNet | CT | Liver tumor segmentation | LiTS | Dice=0.8619 (training), Dice=0.7185 (testing) |

| (45) | 2022 | UNet3+ | CT | Liver tumor segmentation | LiTS | Dice=0.9531 (training), Dice=0.8261 (testing) |

| (97) | 2023 | MANet | CT | Liver tumor segmentation | 3DIRCADb | Dice=0.64, IoU =0.5227, Acc =0.9947, Sen =0.624, Spec =0.999,VOE =0.4773 |

| (97) | 2023 | MANet | CT | Liver tumor segmentation | LiTS | Dice=0.8145, IoU =0.7084, Acc =0.9947, Sen =0.8723, Spec =0.997, VOE =29.15 |

| (79) | 2023 | SLIC-DGN | CT | Liver tumor segmentation | LiTS17 | Dice=0.9, IoU =0.892, Acc =0.987, Sen =0.979, Spec =0.887 |

| (98) | 2023 | Three-path structure with MSFF, MFF, EI, and EG | CT | Liver tumor segmentation | LiTS17 | Dice=0.8555, IoU =0.9045, Acc =0.9979, Sen =0.8682, Spec =0.9993 |

| (99) | 2023 | En–DeNet | CT | Liver tumor segmentation | 3DIRCADb | Dice=0.8481, Acc =0.8808, Prec =0.8613 |

| (99) | 2023 | En–DeNet | CT | Liver tumor segmentation | LiTS | Dice=0.8594, Acc =0.9217, Prec =0.894 |

| (84) | 2023 | Eres-UNet++ | CT | Liver tumor segmentation | LiTS | IoU =0.84, Acc =0.893, F1 score =0.913 |

| (85) | 2023 | Dual-path Network with Swin Transformer Encoding | CT | Liver tumor segmentation | LiTS | Dice=0.681 |

| (100) | 2023 | Enhanced M-RCNN | CT | Liver tumor segmentation | LiTS17 | Dice=0.957, VOE =9.5 |

| (100) | 2023 | Enhanced M-RCNN | CT | Liver tumor segmentation | Sliver07 | Dice=0.9731, VOE =5.37 |

| (82) | 2023 | AIM-Unet | CT | Liver tumor segmentation | LiTS | Dice=0.756 |

| (82) | 2023 | AIM-Unet | CT | Liver tumor segmentation | 3DIRCADb | Dice=0.655 |

| (81) | 2023 | RMAU-Net | CT | Liver tumor segmentation | LiTS | Dice=0.7616 |

| (81) | 2023 | RMAU-Net | CT | Liver tumor segmentation | 3DIRCADb | Dice=0.8307 |

| (87) | 2024 | SADSNet | CT | Liver tumor segmentation | LiTS | Dice=0.8781 |

| (87) | 2024 | SADSNet | CT | Liver tumor segmentation | 3DIRCADb | Dice=0.8750 |

| (101) | 2024 | SEU2-Net | CT | Liver tumor segmentation | PUFH | Dice=0.9504, IoU =0.9055, Acc =0.997 |

| (101) | 2024 | SEU2-Net | CT | Liver tumor segmentation | LiTS | Dice=0.9093, IoU =0.8337, Acc =0.9986 |

| (89) | 2024 | LRENet | CT | Liver tumor segmentation | LiTS, 3Dircadb01, Clinical data | Dice=0.7312, IoU =0.5763, Acc =0.7548 |

| (102) | 2024 | DS-HPSNet | CT | Liver tumor segmentation | 3Dircadb1 | Dice=0.815, Sen =0.807, Prec =0.83 |

| (102) | 2024 | DS-HPSNet | CT | Liver tumor segmentation | MSD | Dice=0.749, Sen =0.726, Prec =0.762 |

| (64) | 2020 | CNN | CECT | Liver segmentation | Clinical data | Dice= 0.961 |

| (103) | 2022 | CNN | CECT | Liver tumor segmentation | 58 patients | Dice=0.987, Prec =0.967 |

| (104) | 2023 | 3D UNet | CECT | Liver segmentation | 170 patients | Best Dice=0.95 |

| (105) | 2023 | U-net | CECT | Liver segmentation | 259 patients | Dice=0.96 |

| (105) | 2023 | U-net | CECT | Liver tumor segmentation | 259 patients | Dice=0.86 |

AI-driven CT models for segmentation of liver and liver tumors.

3DIRCADb, 3D Image Reconstruction for Comparison of Algorithm Database; 3DIRCADb01, 3D Image Rebuilding for Comparison of Algorithms Database; Acc, accuracy; AUC, area under the curve; CECT, Contrast-enhanced CT; DD-UDA, dual discriminator-based unsupervised domain adaptation; DS-HPSNet: Dual-stream Hepatic Portal Vein segmentation Network; EG, edge-guiding; EI, edge-inspiring; En–DeNet, Encoder–Decoder Network; FCN, fully convolutional network; CNN, convolutional neural networks; HFSNet, hierarchical fusion strategy of deep learning networks; IoU, intersection over union; LiTS, liver tumor segmentation; LiTS17, liver tumor segmentation 2017; LRENet, location-related enhancement network; MAD-UNet, multi-scale attention and deep supervision-based 3D UNet; MCC, Matthews’s correlation coefficient; MFF, multi-channel feature fusion; MRFs, Markov random fields; MSD, medical segmentation decathlon hepatic vessel segmentation dataset; MSFF, multi-scale selective feature fusion; PADLLS, pipeline for automated deep learning liver segmentation; Prec, precision; RD DLIR-H, high-strength deep learning image reconstruction; RD DLIR-M, medium-strength deep learning image reconstruction; RMAU-Net, residual multi-scale attention U-Net; VOE, Volume overlap error; SD-Net, semi-supervised double-cooperative network; Sen, sensitivity; SLIC-DGN, SLIC-based deep graph network; Spec, specificity; VOE, volume overlap error.

Table 3

| Ref | Year | AI Model | Tasks | Imaging method | Dataset | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (110) | 2018 | CNN | Characterization of liver lesions: classification in five categories, and malignant (HCC and non-HCC liver cancers) vs indeterminate and benign lesions (hemangiomas and cysts) |

Three-phase CT | Training: 460 patients Testing: 100 patients |

Acc =0.84, AUC =0.92 Classification: Training: Median Acc=0.95~0.97, Testing: Median Acc=0.48−0.84, Sen=0.11~1, Malignant vs the rest: Testing: Median AUC=0.61~0.92 |

| (111) | 2018 | Mics-CNN | Detect FLLs | Multi-phase CT | 89 patients | F1 score =0.82 |

| (91) | 2018 | FCN | Detect liver metastases | CT | 20 patients | Acc =0.946 |

| (106) | 2019 | ML | Distinguish HCC from non-HCC lesions in cirrhotic patients | CT | 13920 images (178 patients) | AUC =0.81 for training set, AUC=0.66 for external validation set |

| (107) | 2019 | SVM, k-NN, Ensemble classifier |

Characterization of FLLs as malignant or benign |

CT | 179 patients: 98 benign and 81 malignant lesions |

Acc=0.966~0.983, Spec=0.9423~0.9703 for HCC |

| (111) | 2019 | CNN | Characterization of FLLs (five categories) |

CT | 89 patients | Sen=0.79~1 |

| (52) | 2019 | DNN | Classify HEM, HCC and MET | CT | 225 images | Acc =0.9939, Sen=1, Spec=0.9909 |

| (108) | 2020 | ANN, SVM, CNN |

Classification of nodular, diffuse and massive HCC | CT | 165 images: 46 diffuse tumors, 43 nodular tumors And 76 massive tumors |

Average AUC=0.957~0.990, Average Acc=0.926~0.984 (average values for all three models) |

| (109) | 2020 | MP-CDN (3 models) |

Detect HCC from other FLLs | Multi-phase CT | 342 patients with 449 lesions (194 HCC), Training set: 359 lesions Test set: 90 lesions |

Acc=0.811~0.856, AUC=0.862~0.925, Sen=0.744~0.923, Spec=0.725~0.941 |

| (113) | 2020 | CNN, SVM |

Differentiation between HCC and ICC | Multi-phase CT | 187 HCC and 70 ICC lesions | Acc =0.88, TPR=0.9518 for HCC, TPR=0.6944 for ICC |

| (25) | 2020 | Radiomics eXtreme Gradient Boosting |

Grading of HCC | CT | Training: 237 Patients, Testing: 60 patients |

Training: AUC=0.6915~0.9964,Acc=0. 6118~0.9705, Sen=0.6067~0.9551, Spec=0.5135~0.8041, Testing: AUC=0.6128~0.8014, Acc=0.483~0.7, Sen=0.4348~0.6522, Spec=0.3784~0.8108 |

| (116) | 2020 | CNN | Detect liver cancer in hepatitis patients | CT | NHIRD | Acc =0.98, Sen =0.783, Spec =0.990, Prec =0.793, F1 score =0.788, MCC =0.777, AUC =0.886 |

| (116) | 2020 | SVM | Detect liver cancer in hepatitis patients | CT | NHIRD | Acc =0.961,Sen =0.343,Spec =0.987, Prec =0.533, F1 score =0.417, MCC =0.409, AUC =0.665 |

| (116) | 2020 | RNN | Detect liver cancer in hepatitis patients | CT | NHIRD | Acc =0.945,Sen =0.357,Spec =0.969, Prec =0.329, F1 score =0.342, MCC =0.314, AUC =0.945 |

| (116) | 2020 | LSTM | Detect liver cancer in hepatitis patients | CT | NHIRD | Acc =0.936, Sen =0.349, Spec =0.967, Prec =0.353, F1 score =0.351, MCC =0.317, AUC =0.936 |

| (116) | 2020 | GRU | Detect liver cancer in hepatitis patients | CT | NHIRD | Acc =0.960, Sen =0.529, Spec =0.978, Prec =0.500, F1 score =0.514, MCC =0.493, AUC =0.960 |

| (112) | 2021 | multi-modality and multi-scale CNN | Characterization of FLLs: malignant (HCC, ICC and metastasis) versus benign lesions (cyst, hemangioma, and FNH), classification of FLLs (Six-class) |

CT | 616 FLLs | Detection: Average Prec=0.828, Classification: Binary classification: Acc=0.825, AUC=0.921, Sen =0.766~0.884, Spec=0.766~0.884, Six-class classification: Acc=0.734, AUC=0.766~0.983, Sen =0.466~0.931, Spec=0.919~0.986 |

| (117) | 2021 | HCCNet | Detect HCC | CT | 7512 patients, Internal test: 385, External test: 556 |

Internal testing: Acc =0.81, Sen =0.784, Spec =0.844, F1 score =0.824, External testing: Acc =0.813, Sen =0.894, Spec =0.74, F1 score =0.819 |

| (118) | 2021 | STIC | Classify HCC and ICC | CT | 723 patients | Acc =0.862, AUC =0.893 |

| (118) | 2021 | STIC | Detect malignant hepatic tumors | CT | 723 patients | Acc =0.726 |

| (119) | 2021 | MDL-CNN | Detect HCC, hepatic cysts, MET, HEM | CT | 4212 images | Dice =0.957 |

| (119) | 2021 | MDL-CNN | Classify HCC, hepatic cysts, MET, HEM | CT | 4212 images | Dice =0.9878 |

| (120) | 2021 | multi-scale CNN | Detect hepatic cysts, HEM, MET |

CT | 1290 images | Acc =0.873 |

| (112) | 2021 | multi-modality and multi-scale CNN | Detect FLLs, including HCC, ICC, MET, hepatic cysts, HEM, FNH | CT | 616 images | Prec =0.828, F1 score =0.878 |

| (112) | 2021 | multi-modality and multi-scale CNN | Classify FLLs (Binary) |

CT | 616 images | Acc =0.825 |

| (112) | 2021 | multi-modality and multi-scale CNN | Classify FLLs (Six-class) |

CT | 616 images | Acc =0.734 |

| (114) | 2021 | ML-EM | Detection and classification of malignant liver lesions (HCC and secondary liver lesions) |

CT | 1638 images | Detection: Acc =0.9839~1, AUC=0.99−1.00 Classification: Acc =0.7638~0.8701, AUC=0.77~0.99 |

| (121) | 2021 | Mask R-CNN | Detect primary hepatic malignancies in HCC patients | CT | 1350 images (1320 patients) | Sen =0.848 |

| (122) | 2021 | CNN | Diferentiating ICC from HCC | Three-phase CT | 617 patients | Acc =0.61, Sen =0.75, Spec =0.88, AUC =0.87 |

| (122) | 2021 | CNN | Diferentiating pHCC from mHCC |

Three-phase CT | 617 patients | Acc =0.61, Sen =0.62, Spec =0.68, AUC =0.68 |

| (123) | 2022 | SVM | Classify HCC, MET, HHs | CT | 452 patients | Acc =0.88 |

| (124) | 2022 | Googlenet | Detect and classify FLLs | CT | 3D-IRCADb01 | Acc =0.93, F1 score =0.9255, Dice =0.64 |

| (124) | 2022 | Unet | Detect and classify FLLs | CT | 3D-IRCADb01 | Acc =0.9865, F1 score =0.9875, Dice =0.83 |

| (124) | 2022 | Dense 3D | Detect and classify FLLs | CT | 3D-IRCADb01 | Acc =0.89, Dice =0.94 |

| (124) | 2022 | Dense-Net | Detect and classify FLLs | CT | 3D-IRCADb01 | Acc =0.92, F1 score =0.93 |

| (124) | 2022 | SegNet VGG-16 | Detect and classify FLLs | CT | 3D-IRCADb01 | Acc =0.86 |

| (124) | 2022 | GMM | Detect and classify FLLs | CT | 3D-IRCADb01 | Acc =0.9538 |

| (124) | 2022 | SVM +RF | Detect and classify FLLs | CT | 3D-IRCADb01 | Acc =0.91 |

| (125) | 2023 | RD DLIR-M | Detect FLLs | CT | 296 patients | Acc =0.8741, Sen =0.749, Spec =0.579 |

| (125) | 2023 | RD DLIR-H | Detect FLLs | CT | 296 patients | Acc =0.7926, Sen =0.625,Spec =0.417 |

| (126) | 2023 | ML | Detect hepatic | CT | LI-RADS2018 | Acc =0.701, Sen =0.67,Spec =0.91 |

| (127) | 2023 | DL-CB | Detect FLLs | CT | 68 patients | Acc =0.733 |

| (127) | 2023 | DL-CB | Detect HCC | CT | 68 patients | Acc =0.704 |

| (115) | 2023 | Modified Unet-60 | Detect and classify FLLs | CT | 3Dircadb | Acc =0.9861, Sen =0.9722, Spec =1, Dice =0.9859 |

| (115) | 2023 | AdaBoost M1 | Detect and classify FLLs | CT | 3Dircadb | Acc =0.9072, Sen =0.9247, Spec =0.8797 |

| (115) | 2023 | SVM | Detect and classify FLLs | CT | 3Dircadb | Acc =0.9517, Sen =0.9576, Spec =0.9422 |

| (115) | 2023 | KNN | Detect and classify FLLs | CT | 3Dircadb | Acc =0.9387, Sen =0.9531, Spec =0.9256 |

| (115) | 2023 | Naïve Bayes | Detect and classify FLLs | CT | 3Dircadb | Acc =0.9194, Sen =0.9365, Spec =0.8991 |

| (115) | 2023 | Random forest | Detect and classify FLLs | CT | 3Dircadb | Acc =0.9486, Sen =0.9538, Spec =0.9388 |

| (115) | 2023 | DNN | Detect and classify FLLs | CT | 3Dircadb | Acc =0.9838, Sen =0.9909, Spec =1 |

| (115) | 2023 | ANN | Detect and classify FLLs | CT | 3Dircadb | Acc =0.8889, Sen =0.8288,Spec =0.9523 |

| (115) | 2023 | MLP | Detect and classify FLLs | CT | 3Dircadb | Acc =0.8915, Sen =0.8801,Spec =0.9038, Dice =0.8905 |

| (115) | 2023 | CNN | Detect and classify FLLs | CT | 3Dircadb | Acc =0.88 |

| (115) | 2023 | CNN | Detect and classify FLLs | CT | 3Dircadb | Acc =0.96 |

| (115) | 2023 | CNN | Detect and classify FLLs | CT | 3Dircadb | Acc =0.8958 |

| (115) | 2023 | CNN | Detect and classify FLLs | CT | 3Dircadb | Acc =0.869 |

| (115) | 2023 | KNN, SVM, RF | Detect and classify FLLs | CT | 3Dircadb | Acc =0.966 |

| (128) | 2024 | HFS-Net | Detect HCC | CT | 595 patients | Sen =0.843, Prec =0.755, F1 score =0.796, Dice =0.828 |

| (129) | 2004 | SVM | Detect hypodense hepatic lesions | CECT | 56 images (51 patients) |

Sen =0.90 |

| (129) | 2004 | SVM | Classify hypodense hepatic lesions | CECT | 56 images (51 patients) |

Sen =0.95 |

| (130) | 2019 | CNN | Classify FNH and HCA | CECT | 98 patients | AUC =0.824 |

AI-based CT models for diagnosing HCC.

3DIRCADb, 3D image reconstruction for comparison of algorithm database; Acc, accuracy; ANN, artificial neural network; AUC,area under the curve; CNN, convolutional neural networks; DCNN, deep convolutional neural networks; DL-CB, deep-learning-based contrast-boosting; DNN, deep neural network; FCN, fully convolutional network; FNH, focal nodular hyperplasia; GRU, gated recurrent unit; HCA, hepatocellular adenoma; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HEM, hemangioma; HFS-Net, hierarchical fusion strategy of deep learning networks; ICC, intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma; KNN, K-nearest neighbors KNN; LI-RADS2018, liver imaging reporting and data system version 2018; LSTM, long short-term memory; MCC, Matthews’s correlation coefficient; MDL-CNN, multi-channel deep learning CNN; MET, metastatic carcinoma; ML, machine learning; ML-EM, multi-level ensemble model; NHIRD, national health insurance research database; Prec,precision; RD DLIR-H, high-strength deep learning image reconstruction; RD DLIR-M, medium-strength deep learning image reconstruction; RNN, recurrent neural network; Sen, sensitivity; Spec, specificity; SVM, support vector machine.

Table 4

| Ref | Year | AI Model | Tasks | Imaging modality | Dataset | Internal validation Results | External validation Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (133) | 2021 | Multi-task DL | Predict future MVI in HCC | CT | 366 patients, Training:281, Testing: 85 |

AUC=0.836 | ~ |

| (134) | 2021 | TwinLiverNet | Predict TACE in HCC patients | CT | 97 images (92 patients) |

Acc=0.825, Sen=0.817, Spec=0.833 |

~ |

| (134) | 2021 | LiverNet | Predict TACE in HCC patients | CT | 97 images (92 patients) |

Acc=0.741, Sen=0.717, Spec=0.767 |

~ |

| (134) | 2021 | Baseline Net (no augm) |

Predict TACE in HCC patients | CT | 97 images (92 patients) |

Acc=0.433, Sen=0.40, Spec=0.467 |

~ |

| (134) | 2021 | Baseline Net (data augm) | Predict TACE in HCC patients | CT | 97 images (92 patients) |

Acc=0.567, Sen=0.533, Spec=0.60 |

~ |

| (131) | 2021 | cML+DL | Predict TACE in HCC patients | CT | 310 patients | AUC=0.994 | ~ |

| (72) | 2021 | ResNet-18 (AP) |

Predict MVI in HCC patients | CT | 309 patients, Training:216, Validation: 93, External testing: 164 |

Acc=0.68, Sen=0.96, Spec=0.56, AUC=0.82 |

Acc=0.66, Sen=0.8, Spec=0.62, AUC=0.75 |

| (72) | 2021 | ResNet-18 (AP +CF) |

Predict MVI in HCC patients | CT | 309 patients, Training:216, Validation: 93, External testing: 164 |

Acc=0.72, Sen=0.96, Spec=0.62, AUC=0.85 |

Acc=0.71, Sen=0.82, Spec=0.67, AUC=0.78 |

| (72) | 2021 | SVM (CF) | Predict MVI in HCC patients | CT | 309 patients, Training:216, Validation: 93, External testing: 164 |

Acc=0.77, Sen=0.71, Spec=0.8, AUC=0.78 |

Acc=0.7, Sen=0.77, Spec=0.67, AUC=0.76 |

| (72) | 2021 | SVM (AP + CF) | Predict MVI in HCC patients | CT | 309 patients, Training:216, Validation: 93, External testing: 164 |

Acc=0.6, Sen=0.93, Spec=0.46, AUC=0.7 |

Acc=0.57, Sen=0.9, Spec=0.47, AUC=0.68 |

| (81) | 2021 | 3D-CNN | Predict MVI in HCC patients | CT | 405 patients, Training:324, Validation:81 |

Acc=0.852, Sen=0.932, Spec=0.757, AUC=0.906, F1 score=0.872 |

~ |

| (135) | 2019 | ML | Predict HCC recurrence postresection | CECT | 470 patients, Training:210, Internal testing: 107; External testing: 153 |

Pre: AUC=0.84, Post: AUC=0.859 |

Pre: AUC=0.803, Post: AUC=0.813 |

| (136) | 2020 | ML | Predict pathological grade of HCC | CECT | 297 patients, training:237, test:60 |

Acc=0.5333, Sen=0.6522, Spec=0.4595, AUC=0.6698 | ~ |

| (137) | 2021 | CDLM | Predict MVI in HCC patients | CECT | 306 patients, validation:115 | Acc=0.73, Sen=0.574, Spec=0.869, AUC=0.736 |

~ |

| (132) | 2022 | DL based clinical-radiological model | Predict MVI in HCC patients | CECT | 283 patients, Training:198, Testing: 85 |

Acc=0.9647, Sen=0.9091, Spec=0.9730, Prec=0.894, F1 score=0.870, AUC=0.909 |

~ |

| (132) | 2022 | Xception | Predict MVI in HCC patients | CECT | 283 patients, Training:198, Testing: 85 |

Acc=0.7059, Sen=0.6364, Spec=0.7162, Prec=0.432, F1 score=0.359, AUC=0.759 |

~ |

| (132) | 2022 | VGG16 | Predict MVI in HCC patients | CECT | 283 patients, Training:198, Testing: 85 |

Acc=0.7294, Sen=0.5455, Spec=0.7568, Prec=0.524, F1 score=0.343, AUC=0.639 |

~ |

| (132) | 2022 | VGG19 | Predict MVI in HCC patients | CECT | 283 patients, Training:198, Testing: 85 |

Acc=0.6824, Sen=0.5455, Spec=0.7027, Prec=0.460, F1 score=0.308, AUC=0.705 |

~ |

| (132) | 2022 | ResNet50 | Predict MVI in HCC patients | CECT | 283 patients, Training:198, Testing: 85 |

Acc=0.8118, Sen=0.7273, Spec=0.8243, Prec=0.565, F1 score=0.5, AUC=0.880 |

~ |

| (132) | 2022 | InceptionV3 | Predict MVI in HCC patients | CECT | 283 patients, Training:198, Testing: 85 |

Acc=0.7529, Sen=0.8182, Spec=0.7432, Prec=0.289, F1 score=0.462, AUC=0.724 |

~ |

| (132) | 2022 | InceptionResNetV2 | Predict MVI in HCC patients | CECT | 283 patients, Training:198, Testing:85 |

Acc=0.7294, Sen=0.5455, Spec=0.7568, Prec=0.339, F1 score=0.343, AUC=0.717 |

~ |

| (138) | 2023 | DL-based multi-input CNN | Predict recurrence risk for recurrence-free survival in HCC patients | Muti-phase CT | 218 patients, Training:152, Internal validation:66, External validation:74 |

C-index=0.627 | C-index=0.630 |

AI-based CT models for HCC prognostication.

AP, arterial phase; CF, clinical factors; C-index, concordance index; cML, conventional machine learning; Multi-modal DNN, multi-modal deep neural network; MVI, microvascular invasion; nnU-Net, 3D neural network; OS, overall survival; TACE, trans-arterial chemoembolization.

Table 5

| Ref | Year | AI Model | Task | Imaging method | Dataset (training/test) | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (141) | 2012 | Iterative watershed algorithm and ANN | Liver segmentation | MRI | 115 images | Average Acc=0.94 |

| (142) | 2016 | 3D fast marching algorithm and neural network |

Liver tumor segmentation | T1-weighted MRI | Medic Medical Center (10 patients), TCIA (6 patients) | mean volumetric overlap error=0.2743, mean percentage volume error=0.1573, Average surface distance (mm)=0.58, RMS surface distance (mm)=1.20, Maximal surface distance (mm)=6.29 |

| (143) | 2018 | FCNN | Liver axial segmentation | Late-Phase MRI | Total: 90 patients, Training: 57, Validation: 5, Testing: 20 |

Dice=0.946 ± 0.018, RVE(%)=4.20 ± 3.34 |

| (143) | 2018 | FCNN | Liver OrthoMean segmentation | Late-Phase MRI | Total: 90 patients, Training: 57, Validation:5, Testing: 20 |

Dice= 0.951 ± 0.018, RVE(%)=4.20 ± 3.65 |

| (143) | 2018 | FCNN | Tumor axial segmentation | Late-Phase MRI | Total: 90 patients, Training set: 57, Validation set: 5, Testing: 20 |

Dice=0.627 ± 0.241, RVE(%)=48.9 ± 53.3 |

| (143) | 2018 | FCNN | Tumor OrthoMean segmentation | Late-Phase MRI | Total: 90 patients, Training: 57, Validation: 5, Testing: 20 |

Dice=0.647 ± 0.210, RVE(%)=35.9 ± 28.2 |

| (144) | 2019 | 2D U-net CNN | Liver segmentation | T1-weighted MRI | 498 patients | Dice=0.95 ± 0.03 |

| (144) | 2019 | 2D U-net CNN | Liver segmentation | T2-weighted MRI | 498 patients | Dice=0.92 ± 0.05 |

| (145) | 2020 | Radiomics-guided DUN-GAN | Liver lesion segmentation | multi-phase non-contrast MRI | 250 patients | Dice=0.9347 |

| (146) | 2020 | 4D k-means clustering estimation |

Liver segmentation | multi-phase MRI | Total: 25 datasets, Training: 10, Validation:15 |

HH=1.76mm, Dice=0.95, Volume Error =3.18% |

| (147) | 2020 | Wide U-Net CNN | Liver Segmentation | T2-weighted MRI | Total: 31 patients | average Dice =0.86 (Liver Vasculature) |

| (140) | 2021 | EIS-Net | Liver segmentation | T1-weighted MRI | 219 patients, Training:127 Validation: 28 Testing: 44 |

for tumors <3cm DSC: p = 0.090, MHD: p = 0.385, MAD: p = 0.142 |

| (140) | 2021 | AS-Net | Liver segmentation | T1-weighted MRI | 219 patients, Training:127 Validation: 28 Testing: 44 |

for tumors >3cm DSC: p = 0.002, MHD: p = 0.003, MAD: p = 0.018 |

| (148) | 2021 | DCNN+TR+RF | Liver segmentation | T1-weighted MRI | LI-RADS | Validation: Dice=0.91, VOE=17, RVD=-0.04, ASSD (mm)=2.47, MSSD (mm)=25.91, External validation: Dice=0.91, VOE=16, RVD=-0.01, ASSD (mm)=2.67, MSSD (mm)=26.96 |

| (149) | 2021 | U-net | Segmentation | T2-weighted MRI | Total: 713 patients, Training: 505, Validation:104, Testing:104 |

Validation: Dice=0.984, Test: Dice=0.983 |

| (150) | 2021 | United adversarial learning | Liver tumor segmentation and detection |

multi-modality NCMRI (T1FS pre-contrast MRI, T2FS MRI, and DWI) | 255 subjects | Dice=0.8363, p-Acc=0.9775, IoU=0.813, TPR=0.9213, TNR=0.9375, Acc=0.9294 |

| (150) | 2021 | Mask R-CNN | Liver tumor segmentation and detection |

multi-modality NCMRI (T1FS pre-contrast MRI, T2FS MRI, and DWI) | 255 subjects | Dice=0.7517, p-Acc=0.9621, IoU=0.6830, TPR=0.80, TNR=0.832, Acc=0.8157 |

| (150) | 2021 | FT-MTL-Net | Liver tumor segmentation and detection |

multi-modality NCMRI (T1FS pre-contrast MRI, T2FS MRI, and DWI) | 255 subjects | Dice=0.7758, p-Acc=0.9648, IoU=0.7064, TPR=0.814, TNR=0.8413, Acc=0.8275 |

| (150) | 2021 | Tripartite-GAN | Liver tumor segmentation and detection |

multi-modality NCMRI (T1FS pre-contrast MRI, T2FS MRI, and DWI) | 255 subjects | IoU=0.7342, TPR=0.8682, TNR=0.8968, Acc=0.8824 |

| (150) | 2021 | Faster R-CNN | Liver tumor segmentation and detection |

multi-modality NCMRI (T1FS pre-contrast MRI, T2FS MRI, and DWI) | 255 subjects | IoU=0.6643, TPR=0.7863, TNR=0.8226, Acc=0.8039 |

| (150) | 2021 | U-net | Liver tumor segmentation and detection |

multi-modality NCMRI (T1FS pre-contrast MRI, T2FS MRI, and DWI) | 255 subjects | Dice=0.7888, p-Acc=0.9657, IoU=0.5833 |

| (150) | 2021 | Rg-GAN | Liver tumor segmentation and detection |

multi-modality NCMRI (T1FS pre-contrast MRI, T2FS MRI, and DWI) | 255 subjects | Dice=0.8065, p-Acc=0.9672, IoU=0.6017 |

| (151) | 2022 | 4D DL based on 3D CNN and LSTM | HCC lesion segmentation | T1-weighted MRI | Total: 190 patients, Training: 110, Validation: 40, Internal testing:40 |

Internal test: Dice=0.825, HD=12.84, VS=0.891, External test: Dice=0.786, HD=21.14, VS=0.89 |

| (151) | 2022 | 3D U-net | HCC lesion segmentation | T1-weighted MRI | Total: 190 patients, Training: 110, Validation: 40, Internal testing:40 |

Internal test: Dice=0.669, HD=22.39, VS=0.751, External test: Dice=0.604, HD=44.47, VS=0.786 |

| (151) | 2022 | nnU-net | HCC lesion segmentation | T1-weighted MRI | Total: 190 patients, Training: 110, Validation: 40, Internal testing:40 |

Internal test: Dice=0.833, HD=10.75, VS=0.88, External test: Dice=0.783, HD=38.61, VS=0.854 |

| (151) | 2022 | RA-Unet | HCC lesion segmentation | T1-weighted MRI | Total: 190 patients, Training: 110, Validation: 40, Internal testing:40 |

Internal test: Dice=0.797, HD=23.88, VS=0.87, External test: Dice=0.749, HD=55.60, VS=0.854 |

| (152) | 2022 | 3D CNN | Liver segment segmentation | MRI | Total: 782 patients, Training:367, Validation:157, Testing: 158, Clinical evaluation set: 100 |

Average Dice=0.902, Average MSD (mm)=3.34, Average HD (mm) =3.61, Average RV= 1.01 |

| (153) | 2022 | nnU-Net | Lliver parenchyma, portal veins, and hepatic veins segmentation | T1-weighted MRI | 30 patients | liver parenchyma: Mean Dice=0.936, portal veins: Median Dice=0.659, hepatic veins: Median Dice=0.548 |

| (139) | 2023 | Cascaded Network | Liver segmentation | T1-Weighted MRI | CHAOS | Dice=0.9515, IoU=0.921, Acc=0.997 |

| (139) | 2023 | Deep action learning with 3D UNet | Liver segmentation | T1-Weighted MRI | CHAOS | Dice=0.806 |

| (139) | 2023 | Contrastive Semi Supervised Learning Approach with UNet | Liver segmentation | T1-Weighted MRI | CHAOS | Dice=0.859 |

| (139) | 2023 | W-Net with attention gates | Liver segmentation | T1-Weighted MRI | CHAOS | Dice=0.8812 |

| (139) | 2023 | Source Free Unsupervised UNet | Liver segmentation | T1-Weighted MRI | CHAOS | Dice=0.8840 |

| (139) | 2023 | Bidirectional Searching Neural Net | Liver segmentation | T1-Weighted MRI | CHAOS | Dice=0.898 |

| (139) | 2023 | Mask R-CNN | Liver segmentation | T1-Weighted MRI | CHAOS | Dice=0.8 |

| (139) | 2023 | Geomatric Edge Enhancement based Mask R-CNN | Liver segmentation | T1-Weighted MRI | CHAOS | Dice=0.91 |

| (154) | 2023 | UNet + + | Liver segmentation | MRI | Total: 105 patients Training set: 83, Validation set: 11, Internal testing:11 |

Validation: average Dice=0.91, Internal testing: average Dice=0.92 |

| (154) | 2023 | UNet + + | Liver tumor segmentation | MRI | Total: 105 patients Training: 83, Validation: 11, Internal testing:11 |

Validation: average Dice=0.612, Internal testing: average Dice=0.687 |

| (155) | 2023 | nnU-Net | Liver and liver vessles segmentation | T1-weighted MRI | Total: 170 patients Training set: 136, Validation set:34 |

Dice=0.77, ASSD=3.235, HD95 = 11.276 |

| (156) | 2024 | 3D residual U-Net | Liver segmentation | MRCP | 250 (225/25) | Dice=0.8 |

| (140) | 2024 | DCNN | Liver segmentation | T1-weighted MRI | 470 patients, Training set: 329, Validation set: 70, Internal testing: 71 External validation set: LiverHccSeg dataset |

Training: mean Dice=0.968, mean MHD=1.876, mean MAD=0.538 Validation: mean Dice=0.966, mean MHD=1.949, mean MAD=0.541 Internal testing: mean Dice=0.967, mean MHD=1.852, mean MAD=0.545 External testing: mean Dice=0.962, mean MHD=2.711, mean MAD=0.705 Public testing: mean Dice=0.928, mean MHD=6.893, mean MAD=1.625 |

| (157) | 2024 | Isensee 2017 network | Liver segmentation | T1-weighted MRI, T2-weighted MRI | 128 patients | average Dice =0.88 |

| (157) | 2024 | Isensee 2017 network | Liver tumor segmentation | T1-weighted MRI, T2-weighted MRI | 128 patients | average Dice =0.53 |

AI-based MRI models for liver and liver tumors segmentation.

ANN, artificial neural network; AS-Net, all-stage-net; ASSD, average symmetric surface distance; CHAOS, combined healthy abdominal organ segmentation grant challenge; EIS-Net, early-intermediate-stage-net; HD95, Hausdorff Distance 95; MBH T2WI, conventional multi-breath-hold (MBH) T2WI; MICCAI, medical image computing and computer assisted intervention; NCMRI, multi-modality non-contrast magnetic resonance imaging; Radiomics-guided DUN-GAN, radiomics-guided densely-UNet-nested generative adversarial networks; SBH-T2WI, single-breath-hold T2-weighted MRI; TCIA, the cancer imaging archive.

Table 6

| Ref | Year | AI Model | Tasks | Imaging method | Dataset | Internal Testing Results | External Testing Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (160) | 2019 | 3D CNN | Discriminating primary and metastatic liver tumors | diffusion weighted MRI (DW-MRI) | Training: 74, Validation: 33, Testing: 23 |

Acc=0.83, Average Prec=0.75, AUC=0.80, Spec=0.67, Sen=0.93, Prec=0.83, Fe-score=0.83 |

~ |

| (159) | 2019 | CNN | Classify liver lesions (six types) | multi-phasic MRI | Training:434, Testing:60 |

Acc=0.897, Prec=0.722, Recall=0.826 |

~ |

| (158) | 2019 | CNN-based DLS | Classify FLLs include HCC | multi-phasic MRI | Training:434, Testing:60 |

Overall Acc=0.90, Overall Sen=0.94, Overall Spec=0.97 |

~ |

| (158) | 2019 | CNN-based DLS | Classify common hepatic lesions | T1-weighted MRI | Training:434, Testing:60 |

Acc=0.943 | Acc=0.92, Sen=0.92, Spec=0.98 |

| (165) | 2019 | Extremely randomized trees classifier |

Classify FLLs (five types) | T2-weighted MRI | 95 patients | Overall Acc=0.77 | ~ |

| (16) | 2020 | AlexNet+ transfer learning | distinguish LI-RADS grade 3 liver tumors from combined higher-grades 4 and 5 tumors for HCC diagnosis | multiphase MRI | LI-RADS dataset, Training (60%), Validation (20%), Testing (20%) | Acc=0.90, Sen=1.0, Prec=0.835, AUC=0.95 | ~ |

| (161) | 2020 | CNN | Classify HCC | MRI | Total: 1210 patients (31608 images), External validation: 201 patients (6816 images) |

AUC=0.951, Sen=0.919, Spec=0.941 |

~ |

| (161) | 2020 | CNN+ clinical data | Classify HCC | MRI | Total: 1210 patients (31608 images), External validation: 201 patients (6816 images) |

AUC=0.951, Sen=0.957, Spec=0.904 |

~ |

| (161) | 2020 | CNN+ clinical data | Classify metastatic malignancy | MRI | Total: 1210 patients (31608 images), External validation: 201 patients (6816 images) |

AUC=0.985, Sen=0.946, Spec=1 |

~ |

| (161) | 2020 | CNN+ clinical data | Classify primary malignancy except HCC | MRI | Total: 1210 patients (31608 images), External validation: 201 patients (6816 images) |

AUC=0.905, Sen=0.733, Spec=0.964 |

~ |

| (148) | 2021 | DCNN | Detect HCC | T1-weighted MRI | LI-RADS | Sen_20 = 0.73, Sen_50 = 0.55, AFPR=2.81, Dice=0.4 |

~ |

| (148) | 2021 | DCNN+TR | Detect HCC | T1-weighted MRI | LI-RADS | Sen_20 = 0.73, Sen_50 = 0.55, AFPR=0.77, Dice=0.49 |

~ |

| (148) | 2021 | DCNN+RF | Detect HCC | T1-weighted MRI | LI-RADS | Sen_20 = 0.73, Sen_50 = 0.55, AFPR=0.85, Dice=0.47 |

~ |

| (148) | 2021 | DCNN+TR+RF | Detect HCC | T1-weighted MRI | LI-RADS | Sen_20 = 0.73, Sen_50 = 0.55, AFPR=0.62, Dice=0.49 |

Sen_20 = 0.75, Sen_50 = 0.66, AFPR=0.75, Dice=0.48 |

| (149) | 2021 | ResNet50 | Liver cirrhosis identification | T2-weighted MRI | Total: 713 patients, Training: 505, Validation:104, Testing:104 |

Acc=0.99, Sen=0.98, Spec=0.96 |

Acc=0.96, Sen=0.98, Spec=0.79 |

| (149) | 2021 | DTL | Liver cirrhosis classification | T2-weighted MRI | Total: 713 patients, Training: 505, Validation:104, Test:104 |

Acc=0.88 | Acc=0.91 |

| (166) | 2020 | CNN | Detect HCC | MRI | Training:455 patients, Testing:45 patients |

Sen=0.87, Spec=0.93, AUC=0.90 | ~ |

| (166) | 2020 | CNN | Classify FLLs | MRI | Training:1210 patients, Testing:201 patients |

Sen=0.405~1, Spec=0.673~1, AUC=0.841−0.989 |

~ |

| (166) | 2020 | CNN | Distinction LI-RADS 3 & LI-RADS 4/5 tumors | MRI | 89 images from 59 patients | Acc=0.767~0.9, Sen=0.756~0.889 |

~ |

| (166) | 2020 | CNN | Classify HCC & non-HCC lesions | MRI | Training:140 patients, Testing:10 patients |

Acc=0.873, Sen=0.82, Spec=0.927 |

~ |

| (166) | 2020 | CNN RF | HCC detection | MRI | 171 patients | Dice=0.48, Sen=0.66~0.75 |

~ |

| (167) | 2021 | GoogLeNet (Inception-V1) | Classify HCC & normal histopathology images | MRI | 29 patients | Acc=0.9137, Sen=0.9216, Spec=0.9057 |

~ |

| (164) | 2021 | CNN | Classify HCC | MRI | 118 patients | Overall Acc=0.873 | ~ |

| (164) | 2021 | CNN | Classify non-HCC | MRI | 118 patients | Acc=0.941, Sen=0.82, Spec=0.927 |

~ |

AI-based MRI models for diagnosing HCC.

AFP, α-fetoprotein; AFPR, the average false positive rate; CDLM, combined deep learning model; cMRI, conventional magnetic resonance imaging (including T2 + DWI + DCE); DCE, dynamic contrast enhanced; DLCR, deep learning combined radiomics; DLF, deep learning features; DTL, deep transfer learning; DW-MRI, diffusion weighted MRI; EOB-MRI, gadoxetic acid-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging; i-RAPIT, intelligent-augmented model for risk assessment of post liver transplantation; LASSO, the least absolute shrinkage and selection operator; LI-RADS, liver imaging reporting and data system; MCAT, multimodality-contribution-aware TripNet; MRE, magnetic resonance elastography; PD-L1, programmed death-ligand 1.

Table 7

| Ref | Year | AI Model | Tasks | Imaging modality | Dataset | Internal Testing Results | External Testing Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (170) | 2021 | First CapsNet Network | Predict survival outcomes on liver transplantation patients with HCC | MRI | Training:87 patients, Testing:22 patients |

Acc=0.64, F1 score=0.61 |

~ |

| (168) | 2021 | H-DARnet | Predict MVI in HCC patients | T2-weighted MRI | Training:168 patients, Testing:57 patients |

Acc=0.826, Sen=0.795, Spec=0.738, AUC=0.775 |

~ |

| (168) | 2021 | Vgg19 | Predict MVI in HCC patients | T2-weighted MRI | Training:168 patients, Testing:57 patients |

Acc=0.505, Sen=0.446, Spec=0.629, AUC=0.537 |

~ |

| (168) | 2021 | AlexNet | Predict MVI in HCC patients | T2-weighted MRI | Training:168 patients, Testing:57 patients |

Acc=0.515, Sen=0.446, Spec=0.662, AUC=0.573 |

~ |

| (168) | 2021 | SqueezeNet | Predict MVI in HCC patients | T2-weighted MRI | Training:168 patients, Testing:57 patients |

Acc=0.54, Sen=0.461, Spec=0.708, AUC=0.625 |

~ |

| (168) | 2021 | ResNet50 | Predict MVI in HCC patients | T2-weighted MRI | Training:168 patients, Testing:57 patients |

Acc=0.545, Sen=0.453, Spec=0.746, AUC=0.626 |

~ |

| (168) | 2021 | GoogleNet | Predict MVI in HCC patients | T2-weighted MRI | Training:168 patients, Testing:57 patients |

Acc=0.605, Sen=0.553, Spec=0.713, AUC=0.649 |

~ |

| (168) | 2021 | DenseNet121 | Predict MVI in HCC patients | T2-weighted MRI | Training:168 patients, Testing:57 patients |

Acc=0.625, Sen=0.586, Spec=0.711, AUC=0.678 |

~ |

| (168) | 2021 | SE-DenseNet121 | Predict MVI in HCC patients | T2-weighted MRI | Training:168 patients, Testing:57 patients |

Acc=0.705, Sen=0.753, Spec=0.60, AUC=0.738 |

~ |

| (168) | 2021 | Simple-SE-DenseNet | Predict MVI in HCC patients | T2-weighted MRI | Training:168 patients, Testing:57 patients |

Acc=0.735, Sen=0.754, Spec=0.696, AUC=0.769 |

~ |

| (187) | 2021 | Fusion DL model | Predict MVI in HCC patients | EOB-MRI | Training:329 patients; external test: 115 patients | ~ | Acc=0.757, Sen=0.704, Spec=0.803, AUC=0.802 |

| (187) | 2021 | CDLM | Predict MVI in HCC patients | EOB-MRI | Training:329 patients; external test: 115 patients | ~ | Acc=0.757, Sen=0.704, Spec=0.803, AUC=0.812 |

| (171) | 2021 | DLF | Predict PD-L1 expression level in HCC patients |

T2-weighted MRI | 103 patients | 5-Fold cross validation: Acc=0.854, F1-score=0.703, Spec=0.947, Prec=0.892, Recall=0.633, AUC=0.852 |

~ |

| (171) | 2021 | radiomics-based model+DLF | Predict PD-L1 expression level in HCC patients |

T2-weighted MRI | 103 patients | 5-Fold cross validation: Acc=0.887, F1-score=0.764, Spec=0.981, Prec=0.948, Recall=0.660, AUC=0.897 |

~ |

| (172) | 2023 | SVM | Predict MVI in HCC patients | multi-parameter MRI | Training:297 patients, Testing: 100 patients |

Acc=0.64, Sen=0.8065, Spec=0.5652, AUC=0.766 |

~ |

| (172) | 2023 | ResNet18 | Predict MVI in HCC patients | multi-parameter MRI | Training:297 patients, Testing: 100 patients |

Acc=0.73, Sen=0.7097, Spec=0.7391, AUC=0.7938 |

~ |

| (169) | 2023 | KNN | Predict TACE outcomes for HCC patients | T2-weighted MRI | Training: 115 patients, Testing; 29 patients |

Acc=0.655, Sen=0.538, Spec=0.75, AUC=0.669 |

Acc=0.536, Sen=0.857, Spec=0.357, AUC=0.615 |

| (169) | 2023 | SVM | Predict TACE outcomes for HCC patients | T2-weighted MRI | Training: 115 patients, Testing; 29 patients |

Acc=0.621, Sen=0.769, Spec=0.563, AUC=0.688 |

Acc=0.679, Sen=0.786, Spec=0.714, AUC=0.712 |

| (169) | 2023 | Lasso | Predict TACE outcomes for HCC patients | T2-weighted MRI | Training: 115 patients, Testing; 29 patients |

Acc=0.655, Sen=0.769, Spec=0.813, AUC=0.745 |

Acc=0.679, Sen=0.929, Spec=0.5, AUC=0.663 |

| (169) | 2023 | DNN | Predict TACE outcomes for HCC patients | T2-weighted MRI | Training: 115 patients, Testing; 29 patients |

Acc=0.759, Sen=0.923, Spec=0.688, AUC=0.837 |

Acc=0.714, Sen=0.714, Spec=0.857, AUC=0.796 |

AI-based MRI models for HCC prognostication.

CDLM, contrast-dependent learning model; EOB-MRI, gadoxetic acid-enhanced MRI; MVI, Microvascular Invasion; TACE, transarterial chemoembolization.

Table 8

| Ref | Year | AI Model | Task | Imaging method | Dataset | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (144) | 2019 | 2D U-Net | Liver segmentation | T1-weighted MRI+ T2-weighted MRI+CT | Total: 498 subjects | CT: Dice=0.94 ± 0.06, T1-weighted MRI: Dice=0.95 ± 0.03, T2-weighted MRI: Dice=0.92 ± 0.05 |

| (174) | 2019 | CycleGAN- DADR |

Liver segmentation | CT+MRI | LiTS+multi-phasic MRI images of 20 patients with HCC | Dice=0.74 |

| (112) | 2021 | APA2Seg-Net | Liver segmentation | CBCT+MRI | LiTS | CBCT: Median Dice=0.903, Mean Dice=0.893, Median ASD=5.882, Mean ASD=5.886, MRI: Median Dice=0.918, Mean Dice=0.921, Median ASD=1.491, Mean ASD=1.860 |

| (175) | 2022 | Unsupervised domain adaptation framework | Liver segmentation | MRI+CT | LiTS+ CHAOS | Dice= 0.912 ± 0.037 |

| (173) | 2023 | SWTR-Unet | Joint liver and hepatic lesion segmentation |

MRI+CT | 61440 MRI images + 189600 CT images | Diceliver=0.98 ± 0.02, Dicelesion=0.81 ± 0.28, HDliver=1.02 ± 0.18, HDlesion=7.03 ± 17.37 |

Summary of studies evaluating AI-based multi-modal models for liver and liver tumors segmentation.

CycleGAN- DADR, CycleGAN based domain adaptation via disentangled representations.

Table 9

| Ref | Year | AI Model | Task | Imaging modality | Dataset | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (176) | 2020 | DCNN | Diagnosis HCC | CT + 20 biological markers |

Total: 766 Training:536 Validation: 153 Testing:77 |

|

| (161) | 2020 | Google Inception-ResNet V2 CNN + autoencoder neural network CNN | Diagnosis HCC | MRI + 16 biological markers |

Total: 38424 images Training:31608 images from 1210 patients Validation: 6816 images from 201 patients |

AUC=0.946 for distinguishing malignant from benign liver tumors, AUC=0.985 for classifying HCC AUC=0.998 for classifying metastatic tumors, AUC=0.963 for classifying other primary malignancies |

| (177) | 2021 | Xception CNN | Diagnosis HCC | CT+ 20 clinical parameters |

Total: 37084 Training: 29104, Validation: 3816, Testing:4164 |

Acc = 0.869, Prec =0.896, Recall =0.869, F1 score =0.867 |

| (118) | 2021 | STIC | Classify HCC and ICC | Multi-phase CECT+clinical data | Total: 723 patients, Training:499, Testing:113, External testing: 111 |

Acc=0.862, AUC=0.893 |

| (178) | 2021 | STIC | Diferential diagnosis of malignant hepatic tumors |

Multi-phase CECT+clinical data | Total: 723 patients, Training:499, Testing:113, External testing: 111 |

Acc=0.726, |

| (179) | 2021 | SVM | Classify aHCC and FNH | CEUS+ radiologist’s | 266 patients | AUC=0.93, Sen=0.935, Spec=0.849 |

| (180) | 2022 | DL | Classify benign and malignant liver lesions | CEUS+clinical factors | 303 patients | AUC=0.957, Acc=0.94, Sen=0.966, Spec=0.905 |

| (181) | 2023 | Multi-modal DNN + Transfer learning & fine-tuned | Multi-class liver cancer diagnosis | CT+ pathology data | Average Acc=0.9606, AUC=0.832 |

AI-based multi-modal models for diagnosing HCC.

Table 10

| Ref | Year | AI Model | Task | Imaging method | Dataset | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (182) | 2020 | Cox-PH | Predict MVI in HCC patients | CT + 9 clinical parameters |

Total:145 Training set: 145 |

AUC=0.79 |

| (183) | 2021 | GhostNet/CNN | Predict TACE response for HCC therapy | CT + clinical evaluation (clinical parameters and biological markers) |

Training:319 patients, Validation: 80 patients |

AUC=0.98, Acc=0.98 |

| (170) | 2021 | First CapsNet network + Second CapsNet network | Predict survival outcomes on liver transplantation patients with HCC | MRI + pathology | Training:87 patients, Testing:22 patients |

Acc=0.68, F1 score=0.65 |

| (170) | 2021 | First CapsNet network + RBF network | Predict survival outcomes on liver transplantation patients with HCC | MRI + Clinical signatures | Training:87 patients, Testing:22 patients |

Acc=0.78, F1 score=0.75 |

| (170) | 2021 | Second CapsNet network + RBF network | Predict survival outcomes on liver transplantation patients with HCC | Pathology + clinical | Training:87 patients, Testing:22 patients |

Acc=0.77, F1 score=0.73 |

| (170) | 2021 | i-RAPIT | Predict survival outcomes on liver transplantation patients with HCC | Clinical+MRI+pathology features | Training:87 patients, Testing:22 patients |

Acc=0.87, F1 score=0.84, Recall=0.80, Prec=0.89 |

| (184) | 2021 | Radiomics, CNN | Predict MVI in HCC patients | MRI + 22 clinical parameters |

Total: 601 Training set:461 Test set:140 |

AUC= 0.915, Overall Acc=0.793 |

| (133) | 2021 | UNet, radiomics, multi-task deep learning neural network (MTNet) |

Predict MVI in HCC patients | CT+ 22 biological markers |

Total: 366 Training set:281 Validation set: 85 |

Training set: AUC=0.877, Validation set: AUC=0.836 |

| (185) | 2022 | Baseline+MCAT | Histologic grading of HCC | T2-weighted MRI + T1-weighted MRI +DCE MRI | 59 patients | Acc=0.8344, Sen=0.8725, Prec=0.8942, F1-score=0.8877 |

| (185) | 2022 | Baseline+MAWM | Histologic grading of HCC | T2-weighted MRI + T1-weighted MRI +DCE MRI | 59 patients | Acc=0.7922, Sen=0.8291, Prec=0.8197, F1-score=0.8382 |

| (185) | 2022 | Baseline+TripNet | Histologic grading of HCC | T2-weighted MRI + T1-weighted MRI +DCE MRI | 59 patients | Acc=0.7854, Sen=0.7944, Prec=0.8235, F1-score=0.7867 |

| (186) | 2022 | DLCR | Predict Ki-67 expression in HCC patients | cMRI + AFP | Total: 108 patients, Training: 87 patients, Internal validation:21 patients External Testing: 43 patients |

Validation: Acc=0.81, Sen=0.80, Spec=0.82, PPV=0.78, NPV=0.80, AUC=0.84 External Testing: Acc=0.72, Sen=0.72, Spec=0.72, PPV=0.68, NPV=0.71, AUC=0.74 |

| (186) | 2022 | DLCR | Predict Ki-67 expression in HCC patients | cMRI + AFP + MRE |

Total: 108 patients, Training: 87 patients, Internal validation:21 patients external Testing: 43 patients |

Validation: Acc=0.87, Sen=0.86, Spec=0.93, PPV=0.84, NPV=0.87, AUC=0.90 External Testing: Acc=0.83, Sen=0.80, Spec=0.86, PPV=0.78, NPV=0.80, AUC=0.83 |

| (138) | 2023 | ResNet18 | Predict MVI in HCC patients | CT+multi-parameter MRI | Training:297 patients, Testing: 100 patients |

Traing: Acc=0.8923,Sen=0.8908, Spec=0.8933, AUC=0.9558, Testing: Acc=0.8, Sen=0.7742, Spec=0.8116, AUC=0.8191 |

| (138) | 2023 | ResNet18 +SVM | Predict MVI in HCC patients | CT+multi-parameter MRI | Training:297 patients, Testing: 100 patients |

Traing: Acc=0.9293, Sen=0.9160, Spec=0.9382, AUC=0.9804 Testing: Acc=0.82, Sen=0.7742, Spec=0.8406, AUC=0.8415 |

AI-based multi-modal models for prognostication of HCC.

APA2Seg-Net, anatomy-preserving domain adaptation to segmentation network; Cox-PH, Cox-proportional hazard; STIC, spatial extractor-temporal encoder-integration-classifier; SWTR-Unet, SWIN-transformer-Unet.

3 Artificial intelligence techniques

AI techniques, including Machine Learning (ML) and Deep Learning (DL), have been extensively investigated in application and interest within the field of liver cancer research (187–190). ML utilizes data to develop algorithms that can identify specific behavioral patterns and build predictive models. The objective of ML is to create a model that leverages statistical dependencies and correlations within a dataset, eliminating the need for explicit programming. This process is divided into two stages: training and validation. During the training stage, the model is exposed to a portion of the available data (training dataset). In the validation stage, the model’s performance is evaluated on a separate subset of the dataset (test dataset) to assess its ability to generalize its training performance to unseen data. Well-known ML algorithms, such as Support Vector Machines (SVM) and Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs), have been applied in HCC management (191, 192).

DL technology, a subset of ML, has shown remarkable efficacy in the analysis of liver images. This is largely due to its ability to process large volumes of data through multiple layers of artificial neurons. These neurons are engineered to emulate the intricate structure of the human brain and its biological neural networks. A unique characteristic of DL algorithms is that these layers of features are not manually constructed with human expertise. Rather, they are autonomously learned from data using a general-purpose learning procedure. This facilitates an end-to-end mapping from the input to the output, essentially converting the image into classification methods. In ML methods, success is contingent upon accurate segmentation and the selection of expert-designed features. DL approaches can surmount these limitations as they can identify the regions of the image most associated with the outcome through self-training. Moreover, they can discern the features of the region that informed the decision through multiple layers.

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) are presently the most prevalent DL algorithms employed for the diagnosis and management of HCC (193–195). The uniqueness of CNNs compared to Fully Connected Networks lies in their ability to capture spatial hierarchies through convolutional and pooling layers, their parameter efficiency due to shared weights, and their effectiveness in processing structured data like images and videos. The fundamental principles of CNNs include local connections, shared weights, pooling, and the use of numerous layers. These components collectively enhance the accuracy and efficiency of the entire system. A standard CNN model is composed of an input layer, an output layer, and several hidden layers. These hidden layers encompass convolutional layers, pooling layers, and fully-connected layers. By repeatedly applying convolution and pooling, fully-connected layers are subsequently utilized for classification or predictions. There exists a variety of layer combinations, and numerous Deep Neural Network (DNN) architectures have been successfully implemented for HCC diagnosis and prediction. These include Fully Convolutional Networks (FCNs) (196), 3D U-Net (197), Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) (198), Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) (199, 200), Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) (16, 201), AlexNet (202), and VGGNet-19 (203). These models are specifically engineered to eliminate fully connected layers and restore spatial dimensions, thereby augmenting DL capabilities even when there is a scarcity of labeled data. However, it is imperative to address domain adaptation and dataset bias to ensure the success of transfer learning (TL). This is because these factors can significantly influence the performance and generalizability of the models.

In contrast to CNNs, Fully Convolutional Networks (FCNs) are engineered to preserve spatial information, thereby enhancing their effectiveness for pixel-level predictions. This attribute renders FCNs particularly apt for liver tumor segmentation, as they employ convolutional layers in lieu of fully connected ones (196).

U-Net, conversely, utilizes an encoder-decoder model equipped with skip connections. This architecture enables it to amalgamate local and global context information, thereby augmenting object localization precision. Despite the limitations posed by scarce training data, 3D U-Net has exhibited remarkable results in the classification of liver lesions (197).

RNNs, encompassing Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) and Gated Recurrence Unit (GRU), are specifically tailored to scrutinize sequential data by capturing temporal dependencies. These models have been successfully deployed for predicting HCC recurrence post liver transplantation (198). By addressing the vanishing gradients issue and capitalizing on temporal dependencies, they have substantially enhanced prediction accuracy.

Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) offer a variety of techniques for graph convolution, which are instrumental in clinically predicting Microvascular Invasion (MVI) in Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC) (199). These techniques include spectral-based and spatial-based GCN approaches, each carrying unique computational implications. DenseGCN, a contemporary architecture, has been introduced for the identification of liver cancer. It integrates advanced techniques such as similarity network fusion and denoising autoencoders, significantly boosting detection accuracy (200).

Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) have demonstrated their value in generating synthetic images and augmenting data across a range of medical applications. In the realm of liver tumor detection, Tripartite GAN offers a cost-effective and non-invasive alternative by generating contrast-enhanced MRI images, eliminating the need for contrast agent injection (201). Another promising application is the Mask-Attention GAN, which generates realistic tumor images in CT scans for training and evaluation purposes (16).

Transfer Learning (TL) strategies have been employed in the field of medical imaging to mitigate overfitting issues arising from limited data. Within the TL framework, knowledge can be shared and transferred between different tasks. The workflow comprises two steps: pretraining on a large dataset and fine-tuning on the target dataset. Essentially, by fine-tuning the DL architecture, the knowledge gleaned from one dataset can be transferred to a dataset procured from another center.

4 AI-based US techniques

US is recommended in clinical guidelines for the detection of HCC in patients with cirrhosis. However, its efficacy can be influenced by several factors, including operator experience, equipment quality, and patient morphology. Previous studies have indicated that the sensitivity of HCC detection using conventional US ranges from 59% to 78% (204). To enhance sensitivity and specificity, various US modalities have been explored. For instance, Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound (CEUS) has been demonstrated to improve the sensitivity of HCC detection. These models serve as invaluable tools for predicting HCC recurrence, guiding treatment decisions, and improving patient outcomes. This study investigates the most recently developed AI-based approaches for evaluating detection, prognostication, treatment response, and survival in HCC. Table 1 provides a summary of the results from studies evaluating AI-based US approaches for HCC diagnosis.

4.1 Diagnosis of focal liver lesions

This section outlines the recently developed AI-based US models for diagnosing HCC. These applications encompass diagnosing focal liver lesions (FLLs), distinguishing between benign and malignant liver lesions, differentiating HCC from focal nodular hyperplasia (FNH), cirrhotic parenchyma (PAR), and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC) (see Table 1). Among these studies, Bharti et al. (21) proposed a Support Vector Machine (SVM) model that integrates three classifiers using B-mode US data to assess and differentiate various stages of liver disease, achieving a classification accuracy of 96.6%.

In 2020, Brehar et al. (24) demonstrated that a CNN model, trained on two distinct US machine datasets (GE9 and GE7), surpassed conventional ML models (SVM, Random Forest (RF), Multi-Layer Perceptron, and AdaBoost) in differentiating between HCC and PAR. The proposed model achieved Area Under the Curve (AUC) values of 0.91 and 0.95 and accuracies of 84.84% and 91% in the GE9 and GE7 datasets, respectively. In 2023, Jeon et al. (35) proposed a CNN model using quantitative US data from 173 patients for diagnosing hepatic steatosis, achieving an AUC of 0.97, a sensitivity of 90%, and a specificity of 91%.

CEUS generally outperforms B-mode US in diagnosing FLLs and HCC, and AI has augmented its capabilities in identifying potential malignancies. Several research groups have studied the differentiation of benign and malignant FLLs (refer to Table 1). In 2020, Huang et al. (43) investigated the use of an SVM model for evaluating diagnostic accuracy when differentiating between atypical HCCs (aHCC) and FNH using CEUS data. The proposed SVM model achieved an AUC of 0.944, a sensitivity of 94.76%, and a specificity of 93.62%.

In 2021, Căleanu et al. (44) proposed a DL model to classify five types of FLLs using CEUS data, obtaining a general accuracy of 88%. Hu et al. (45) investigated a CNN model trained on four-phase CEUS video data from 363 patients. The proposed CNN model achieved an accuracy of 91% and an AUC of 0.934 on the testing dataset, slightly outperforming resident radiologists and matching experts.

4.2 Characterization of focal liver lesions

In a study conducted by Virmani et al. (7), a Neural Network Ensemble (NNE) model was proposed to distinguish a normal liver from four distinct liver lesions, achieving an impressive accuracy of 95%. The diagnoses for the included liver lesions were confirmed through experienced radiologists, clinical follow-ups, and other associated findings.

In 2017, Hassan et al. (20) introduced an ANN model that achieved a classification accuracy of 97.2% for benign and malignant FLLs. In 2019, Schmauch et al. (22) developed a supervised DL model, specifically a CNN, utilizing a French radiology public challenge dataset for diagnosing FLLs. The model was capable of detecting FLLs and categorizing them as benign (such as cyst, FNH, and angioma) or malignant (like HCC, metastasis), achieving a mean AUC of 0.935 and 0.916 in the training dataset. Despite promising results, further validation is required due to the limited number of images used for training.

In 2020, Yang et al. (23) conducted a multicenter study to develop a Deep Convolutional Neural Network (DCNN) using an US database, along with background and clinical parameters (such as HBV, HCV, lesion margin, morphology) for characterizing FLLs. The model achieved an AUC of 0.924 for distinguishing benign from malignant lesions in the external validation dataset. The model demonstrated superior accuracy compared to clinical radiologists and CECT, albeit slightly lower than Contrast-Enhanced Magnetic Resonance Imaging (CE-MRI) (87.9%). This approach could potentially enhance radiologists’ performance and reduce the reliance on CECT/CEMR and biopsy.