Abstract

This study is a retrospective analysis of our case series and literature review of aggressive B-cell lymphomas with MYC rearrangements that show immunophenotypic immaturity, including expression of terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT), weak or negative CD20, and the absence of surface membrane immunoglobulin (smIg) and light chains. Although classified as diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) or high-grade B-cell lymphoma (HGBCL), these cases sometimes resemble B-lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma (B-ALL/LBL) immunophenotypically, creating diagnostic ambiguity. We report four cases: three diagnosed as HGBCL-MYC/BCL2 with TdT expression, and one as B-ALL with MYC rearrangement. Case 1 developed from follicular lymphoma with TdT-positive blastoid transformation. Case 2 showed widespread disease, complex cytogenetics, weak TdT positivity, and absence of light chain. Case 3 displayed scattered TdT expression and surface light chain restriction. Case 4, initially diagnosed as a mature B-cell neoplasm, was ultimately reclassified as B-ALL with MYC rearrangement and focal TdT expression. In all cases, CD20 expression was weak or negative. These overlapping immunophenotypes between mature B-cell neoplasms and lymphoblastic leukemia were also documented in previous reports of 89 patients with various MYC-rearranged mature B-cell lymphoma subtypes. Through review, we identified the patient population with tumor cells showing less than 10% positive TdT expression, weak or negative CD20, and absence of smIg and light chain expression. Conversely, B-ALL with MYC rearrangement also exhibits aberrant immunophenotypes, such as negative to weak TdT expression and variable CD20, smIg, or light chain expression. Notably, this phenotypic immaturity appears closely linked to the presence of MYC rearrangement. In contrast, recent studies have shown that TdT-positive DLBCL/HGBCL-MYC/BCL2 and B-ALL with MYC rearrangement have distinct molecular features. In conclusion, an analysis of 93 cases, including our four cases, suggests that MYC rearrangement contributes to immature immunophenotypic profiles in both lymphoma and leukemia, emphasizing the importance of a refined classification that integrates morphology, immunophenotype, and genetics.

1 Introduction

About 2% of cases of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) or high-grade B-cell lymphoma (HGBCL) with MYC and BCL2 rearrangements show expression of terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT) (1). These cases also exhibit other immature immunohistochemical features, such as the weak/absence of CD20 expression, lack of surface membrane immunoglobulin (smIg), and no light chain detection. There is ongoing debate over whether these lymphomas should be classified as B-lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma (B-ALL/LBL) or DLBCL/HGBCL (2–4). However, the 5th WHO classification now categorizes them as DLBCL/HGBCL-MYC/BCL2 (with or without BCL6 rearrangement) with TdT expression (5). Conversely, differential diagnosis should consider a rare B-ALL/LBL variant with MYC rearrangement, displaying characteristics of mature B-cell lymphomas (BCLs), such as CD20 positivity, TdT negativity, smIg expression, light chain restriction, and the IGH-BCL2 translocation (5). In MYC-rearranged B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia (BCP-ALL), which is common in pediatric cases and typically characterized by the absence of smIg and light chains, some instances have also shown characteristics of mature B cells (6).

We present a case of HGBCL-MYC/BCL2 with TdT expression that evolved from FL, along with two other cases of HGBCL-MYC/BCL2 with TdT and one case of B-ALL with MYC rearrangement, all diagnosed and treated at our institutions. Additionally, we reviewed previously reported cases of aggressive BCLs (1–4, 7–15), B-ALL/LBL (16–24), and BCP-ALL (6, 25–33) with MYC rearrangement that exhibit immunophenotypically diverse immature patterns, including varying TdT, CD20, smIg, and light chain expressions.

2 Case report

2.1 Case 1

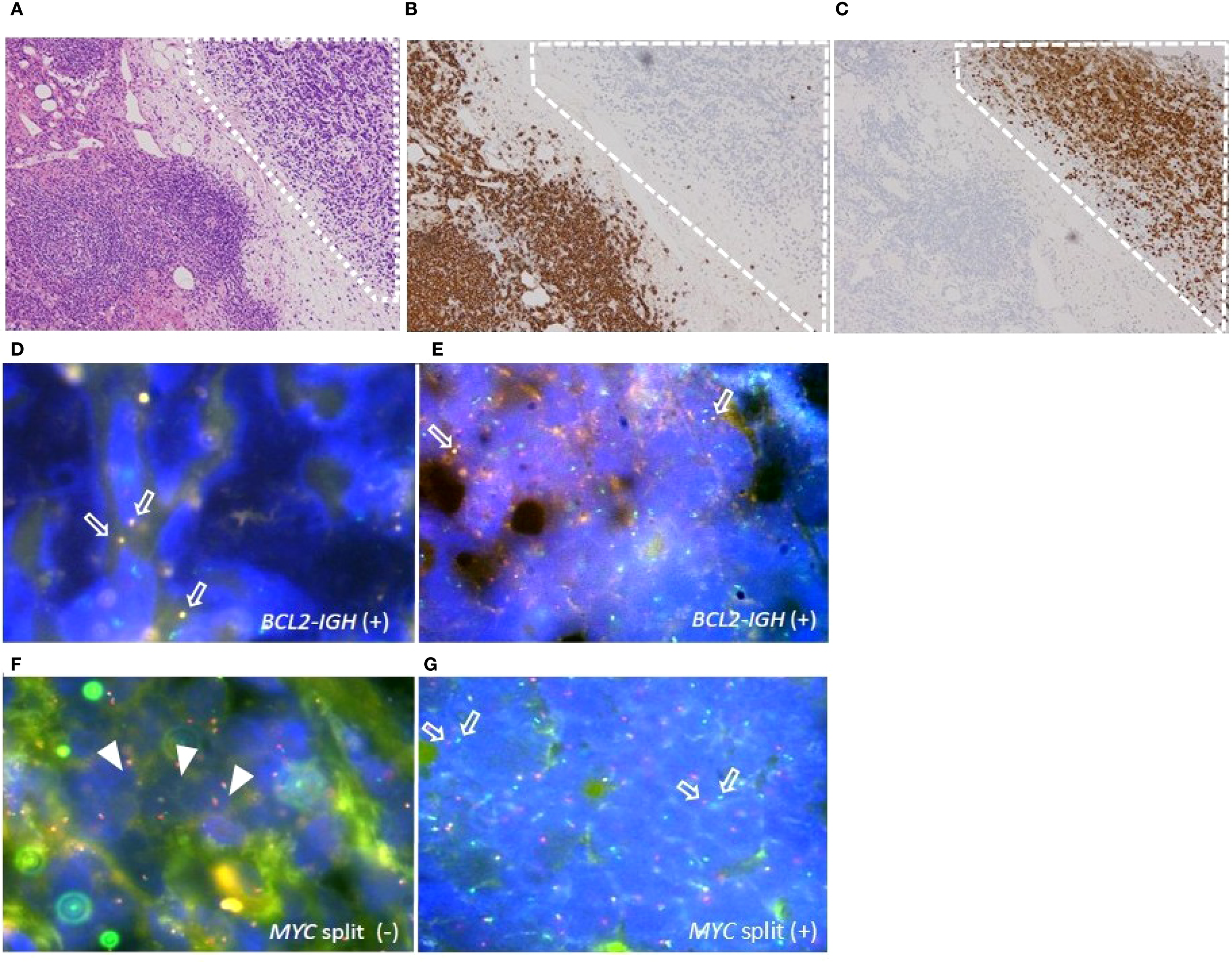

A 76-year-old woman visited our hospital with low back pain linked to intraperitoneal lymphadenopathy exhibiting 18F-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (18F-FDG) uptake on positron emission tomography–computed tomography (PET/CT). The biopsy of the affected lymph nodes showed two distinct histological components. The central region of the lymph nodes was marked by multiple follicles containing proliferating small to medium-sized atypical lymphocytes. Notably, each follicle housed 6–15 centroblasts viewed under high-power microscopy, and a follicular dendritic cell meshwork surrounded the nodules (Supplementary Figure S1A). In addition, a group of atypical lymphoid cells with condensed chromatin was also present in the adipose tissue around the lymph nodes (Figure 1A). In the initial lesion, atypical lymphoid cells tested positive for CD10, CD20, CD21, and BCL-2 (Supplementary Figure S1B) but were negative for CD3, confirming the diagnosis of FL grade 2. In the subsequent lesion, atypical lymphoid cells tested negative for CD3 and CD20 (lesion surrounded by dashed square in Figure 1B), while being positive for CD10, CD79a, BCL-2, PAX-5, Ki-67, and TdT (Figure 1C), indicating the presence of a B-LBL component. Tissue fluorescence in situ hybridization (t-FISH) using the Vysis LSI IGH/BCL2 Dual Color Fusion Probe (Abbott, Abbott Park, IL) showed fusion signals for IGH and BCL2 in both the FL and B-LBL components (Figures 1D, E). Additionally, MYC rearrangement was observed only in the B-LBL component, detected by t-FISH with the Vysis LSI MYC Dual Color Break Apart Rearrangement Probe (Abbott) (Figures 1F, G) (Table 1). The bone marrow (BM) examination revealed the presence of a small number of CD20-positive but TdT-negative atypical lymphoid cells, suggesting infiltration of the BM by the FL component. According to the Ann Arbor disease staging system, we diagnosed Case 1 as stage IV HGBCL-MYC/BCL2 with TdT expression, transformed from FL. Although the patient temporarily responded to G-CHOP therapy, comprising obinutuzumab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone, the disease relapsed systemically after five cycles, without FL components. Presently, the patient is receiving salvage chemotherapy with fractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone (hyper-CVAD) alternating with high-dose methotrexate and cytarabine therapy, as blinatumomab was ineffective.

Figure 1

Histopathologic features of the adipose tissue around the biopsied lymph nodes in case 1. (A) B-lymphoblastic lymphoma (LBL) component (surrounded by dashed square) examined by Hematoxylin-Eosin (HE) staining, original magnification ×40. (B, C) IHC staining for CD20 (B) and TdT (C) in B-LBL component (surrounded by dashed square), original magnification ×40. (D–G) Tissue fluorescence in situ hybridization (t-FISH) analyses for IGH/BCL2 and MYC rearrangement. (D, E) t-FISH for IGH/BCL2 in FL component (D) and in B-LBL component (E). Arrows indicate the fusion signals of IGH/BCL2. (F, G) t-FISH for MYC split analyses in FL component (F) and in B-LBL component (G). Arrowheads indicate the fusion, and arrows indicate the split signals of c-MYC gene.

Table 1

| Case | Age /Gender | Disease subtype | Ann Arbor disease stage (lymphoma lesion) | Chromosomal rearrangement | Immunohistochemistry | Flow cytometry | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MYC | BCL2 | other | ||||||

| 1 | 76/F | tFL | IVA (BM, mesenteric LN) |

+ | + | – | LN: CD20-, CD5-, CD3-, CD10+, CD79a+, TdT+ (100%), PAX5+, BCL-2+, BCL-6+ (50%) BM: CD20+ (scatter), TdT+ (scatter) |

LN: CD5-, CD10+, CD19+, CD20+ (62.5%), CD22-, λ+ BM: CD5-, CD10+, CD19+, CD20+ (69.3%), CD22+, CD34-, CD79a+, TdT+ (21.9%), λ+ |

| 2 | 80/F | HGBCL | IVB (BM, retroperitoneal LN, heart, stomach, adrenal gland, kidney, bone) |

+ | + | BCL6 rearrangement | LN: CD3-, CD5-, CD20+ (10%), CD79a+, CD10+, BCL-2+, BCL-6+ (90%), TdT+ (5%) BM: data not available |

LN: CD5-, CD10+, CD19+, CD20 (0.9%), CD22-, CD79a+, TdT- (0.9%), lc- BM: data not available |

| 3 | 73/M | HGBCL | IVB (BM, retroperitoneal LN, para-aortic LN, hepatic hilar LN、heart) |

+ | + | – | LN: CD3-, CD5-, CD10+, CD20 -, CD34-, CD38+, CD79a+, CD138-, BCL-2+, BCL-6– (10%), EBER-, TdT+ (~5%), PAX5+ BM: CD3-, CD10+, CD38+, CD79a+, TdT- |

LN: CD5-, CD10+, CD19+, CD20 (4.5%), CD22+, CD34-, CD38+, CD79a+, λ+ BM: CD1a– (0.5%), CD5-, CD10+, CD19+, CD20– (9.6%), CD22+, CD34–, CD38+, CD138-, TdT– (1.2%)、lc- |

| 4 | 85/M | B-ALL | IVB (BM) |

+ | – | – | CD10+, CD20– (5%), CD38+, CD79a+, TdT+ (50%), BCL-2- | CD1a–, CD5-, CD10+, CD19+, CD20–(1.5%), CD38+, CD22+, CD79a+, CD34–, TdT– (1.1%), λ+ |

Clinical, cytogenetic, and immunophenotypic manifestation of aggressive B-cell lymphomas and B-ALL with concomitant MYC rearrangement in our hospitals.

tFL, transformed follicular lymphoma; HGBCL, high-grade B-cell lymphoma; B-ALL, B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia; M, male; F, female; BM, bone marrow; LN, lymph node; lc, light chain.

2.2 Case 2

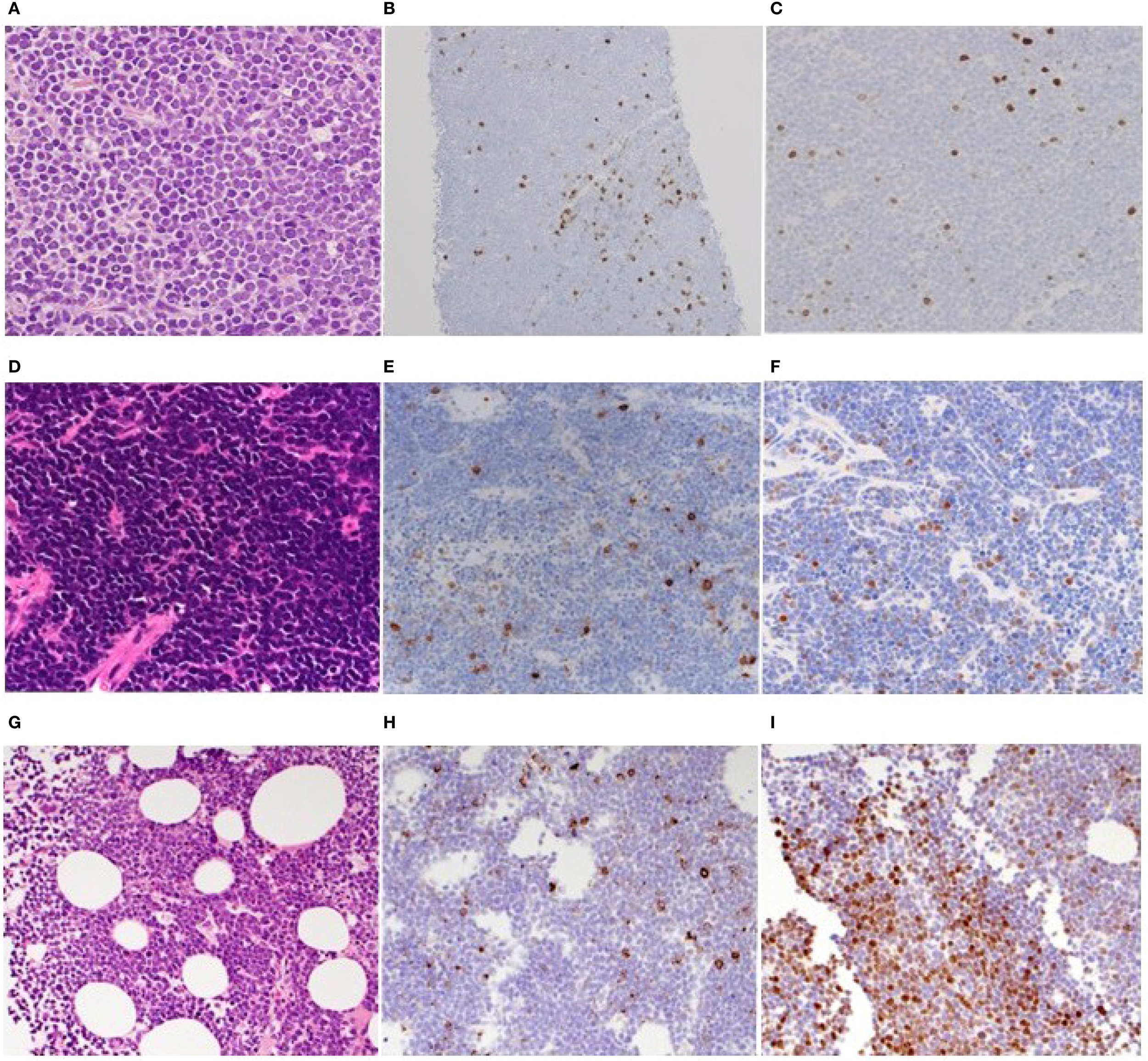

An 80-year-old woman was referred to our hospital due to symptoms of systemic decline, including chest discomfort, loss of appetite, swelling in her lower legs, and back pain lasting several weeks. PET/CT scans revealed widespread abnormal 18F-FDG-avid lesions across multiple sites: bilateral adrenal glands, pancreas, perinephric and right femoral lumbar muscles, pelvic cavity, atrial septum, soft tissue around the Th3 vertebral body, uterine endometrium, and bones. A biopsy of the retroperitoneal tumor showed proliferation of small, atypical lymphoid cells with high nuclear-to-cytoplasm ratio (Figure 2A; Supplementary Figure S2A), positive for CD10, CD19, CD79a, BCL-2 (Supplementary Figure S2B), BCL-6 (Supplementary Figure S2C), and c-MYC (Supplementary Figure S2D) by immunohistochemistry. About 10% of tumor cells tested positive for CD20 (Figure 2B), and 5% were weakly positive for TdT (Figure 2C). Flow cytometry analysis showed that the tumor cells did not express smIg. Chromosomal analysis with G-banding indicated a complex abnormality: 50, XX, add(5)(q11.2),?t(8;14)(q24;q32), +12, t(14;18)(q32;q21), +20. The standard double-color FISH tests confirmed that all tumor cells had translocations involving IGH/BCL2 and IGH/MYC, along with a BCL6 gene rearrangement (Table 1). Overall, we diagnosed Case 2 with stage IV HGBCL-MYC/BCL2 and BCL6 rearrangements, along with an unusual TdT-positive component. Despite treatment with EPOCH chemotherapy, including doxorubicin, vincristine, etoposide, cyclophosphamide, and prednisolone, the disease progressed, and the patient died on day 41.

Figure 2

Histopathologic features of the biopsied specimens of cases 2-4. (A–C). Retroperitoneal tumorous lesion of case 2. HE-stained biopsied specimen (×100) (A) and IHC staining for CD20 (B) and TdT (×40) (C). (D–F). Retroperitoneal tumorous lesion of case 3. HE-stained biopsied specimen (×100) (D) and IHC staining for CD20 (E) and TdT (×40) (F). (G–I). Bone marrow of case 4. HE-stained biopsied specimen (×100) (G) and IHC staining for CD20 (H) and TdT (×40) (I).

2.3 Case 3

A 73-year-old man presented to our hospital with two months of fatigue and one week of left lower abdominal pain. Blood tests indicated elevated LDH levels and kidney impairment. An enhanced-contrast CT scan showed a large mass in the left retroperitoneal area involving the left ureter, along with enlarged lymph nodes around the right hepatic artery and near the aorta. Biopsy of the retroperitoneal mass revealed proliferation of small to medium atypical lymphoid cells with high nuclear-to-cytoplasm ratios (Figure 2D; Supplementary Figure S3A). These cells tested positive for CD10, CD79a, PAX-5, BCL-2, BCL-6 (10-20%), and c-MYC (Supplementary Figures S3B–G), but most tumor cells were negative for CD20 (Figure 2E) on immunohistochemistry. Of note, about 5% of the tumor cells scatteredly tested positive for TdT (Figure 2F). Flow cytometry analysis showed that the tumor cells did not express smIg. In addition, Epstein-Barr virus early RNA in situ hybridization (data not shown). Chromosomal analysis via G-banding identified a complex abnormality including a 48, XY karyotype with multiple deletions, additions, and translocations, including -2, -6, -8, -13, -14, t(14;18)(q32;q21), -17, -19, +21, and other marker chromosomes. Conventional double-color FISH confirmed that all tumor cells carried gene rearrangements of BCL2 and MYC (Table 1). Based on our findings, we diagnosed the case asstage IV HGBCL-MYC/BCL2 with abnormal TdT expression. Despite the patient receiving EPOCH chemotherapy, the disease returned within three months. We then gave the patient DeVIC therapy, which included dexamethasone, etoposide, ifosfamide, and carboplatin, as a temporary treatment; however, new lesions developed in the lung and hilar lymph nodes. The patient was then treated with CAR-T therapy, and they have since stayed in remission with a complete response.

2.4 Case 4

An 85-year-old man was referred to our hospital, presenting with fever and fatigue. Laboratory tests showed elevated LDH levels and increased white blood cell counts. Peripheral blood and bone marrow samples contained approximately 20% and 80% abnormal small lymphocytes, respectively. There was no lymphadenopathy or splenomegaly on plain CT. Flow cytometry of bone marrow cells identified a CD45-dim population positive for CD10, CD19, CD79a, CD22, CD38, and light chain restriction for kappa, while negative for CD1a, CD3, CD34, TdT, and CD20. Due to rapid progression, we initially diagnosed it as a stage IV CD20-negative mature B-cell neoplasm and treated it with prednisolone. Unfortunately, he died from alveolar hemorrhage caused by disseminated intravascular coagulation on hospital day 3. Subsequently, biopsy revealed the bone marrow was filled with blastoid cells (Figure 2G) immunohistochemically positive for CD20 (partial) (Figure 2H), CD10, CD79a (Supplementary Figures S4A, B), CD38, TdT (focal, about 50%) (Figure 2I), and c-MYC (Supplementary Figure S4C), but negative for BCL-2 (Supplementary Figure S4D). FISH analysis showed split signals for MYC and no IGH-BCL2 fusion. G-banding revealed complex chromosomal abnormalities, including additions at 1(p11), 3(p21), deletions on chromosomes 15 and 19, and other unspecified alterations (Table 1). The final diagnosis was B-ALL with MYC rearrangement.

3 Discussion

Although the first three cases in our series were initially identified as mature B-cell malignancies, their tumor cells displayed immunophenotypic features typical of immature B cells. These cells were weakly or negatively stained for CD20, lacked smIg and light chains, and showed variable TdT expression, including scattered, weak, or diffuse patterns. Our four cases of BCL showed cytogenetic abnormalities involving either MYC and BCL2 rearrangements or combinations of MYC, BCL2, and BCL6 rearrangements. This contrasts with earlier studies that reported multiple cases of BCL with an immature phenotype and only a MYC rearrangement (1, 2, 4, 7, 9, 16). Furthermore, many BCL cases with MYC and BCL2 rearrangements are derived from transformed follicular lymphoma (FL), where the MYC rearrangement typically occurs during transformation. Our findings overall indicate that MYC rearrangement is more likely to result in abnormal immature cell types than other genetic defects. We gathered case reports and series of aggressive B-cell lymphomas (including DLBCL, HGBCL, Burkitt lymphoma, mantle cell lymphoma, and B-lymphoblastic lymphoma) from PubMed that showed MYC rearrangement through FISH or G-banding, and displayed unusual immature B-cell features like TdT positivity on immunohistochemistry, CD20 negativity, or loss of flow cytometric smIg. (Supplementary Table S1). In this context, TdT expression in BCLs varies from scattered and weak to diffuse, unlike the diffuse pattern typical of B-ALL. In 49 reported cases, including our three patients, TdT-positive BCL cells often lack smIg, show light chain restriction, and are CD20 positive. These features can be misleading but usually indicate the presence of both “immature” tumor components and mature B-cell components. Several studies have highlighted this as a diagnostic challenge (1, 3, 4, 8). Typically, TdT positivity is considered when 10% or more of tumor cells are positive in immunohistochemistry (34), but in mature BCLs with MYC rearrangement, this should be interpreted with caution. Previous studies on double/triple hit lymphoma and HGBCL with MYC rearrangement have reported cases with a few percent of TdT-positive cells, rather than being negative, due to the presence of immature B-cell features despite TdT expression below 10%. (3, 7, 8, 35, 36). On the other hand, cases of HGBCL/DLBCL-MYC/BCL2 and HGBCL with MYC rearrangement may show no TdT expression, along with missing smIg, light chain, and CD20. This highlights the variable TdT expression in immature cells found within aggressive mature B-cell lymphomas (3, 9, 37–39).

These irregular marker patterns, similar to those in ALL, are evident in our case 4, where neoplastic lymphoid cells displayed weak CD20 and focal TdT expression by immunohistochemistry, and flow cytometry showed light chain expression in tumor cells. This underscores the complexity of immunophenotypic profiles.

These phenotypes were also observed in BCP-ALL cases with MYC rearrangement (6, 25–33). We chose B-ALL/BCP-ALL cases that had previously been reported, where MYC rearrangement was confirmed by FISH or G-banding, and TdT expression was evaluated by flow cytometry (Supplementary Table S2). Several studies show that MYC rearrangement affects abnormal expression patterns of TdT, CD20, smIg, and light chains in B-ALL (6, 17–33). Looking back at the UKALLXII/ECOG-ACRIN E2993 study, researchers found that B-ALL cases with MYC rearrangement show significant diversity, including cases that are both TdT-positive and -negative, as well as smIg-positive and -negative (40). Reports have also documented TdT-positive and smIg-positive B-ALL cases with MYC rearrangements (17–24). Additionally, a study on pediatric BCP-ALL found that cases without smIg and light chain expression, and with MYC rearrangement, had similar variability in CD20 expression across Japanese and international cohorts. However, TdT expression was less common in the Japanese group and more prevalent internationally (6). Additionally, weak TdT expression has been observed in several cases of MYC-rearranged B-ALL and BCP-ALL (19, 24, 25, 30). According to other genetic studies, BCLs with MYC rearrangement often contain genetic abnormalities linked to mature B-cell lymphomas (1), whereas B-ALL with MYC rearrangement often lacks additional mutations (41). Since both types show abnormal immature B-cell features despite different genetic characteristics besides MYC rearrangement, it is suggested that the MYC rearrangement may play a role in this phenomenon.

4 Limitation

Our analysis has several limitations. This study is a case series that brings together previously reported cases to get a deeper understanding of the disease. However, for statistical analysis, problems like unclear disease definition, a small sample size, and potential biases still exist, and these need to be addressed in future studies. It’s based on studies of the immune system and cells after the fact, but the specific molecular genetic mechanisms behind B-cell maturation with MYC rearrangement are still unknown. Additionally, evaluating TdT staining can be somewhat subjective. For example, in previous B-ALL studies, some cases without TdT might still have fewer than 10% TdT-positive cells, while others might be considered TdT-positive even if less than 10% of tumor cells express TdT. As shown in the table, B-ALL/BCP-ALL phenotypes are mainly evaluated using flow cytometry, whereas BCLs are primarily evaluated using immunohistochemistry. This difference in evaluation methods should also be carefully noted. Additionally, in BCLs, cases that show weak TdT positivity in immunohistochemistry may appear negative in flow cytometry, showing how the two methods can produce different results. In pediatric B-ALL with MYC rearrangement, cases with smIg expression are rare. The specific case also involved an MLL rearrangement (23). Since B-ALL cases with MLL rearrangements and smIg positivity have been reported separately (42), we cannot exclude the possibility that MLL rearrangements also contribute to B-cell immaturity. Regarding treatment, CAR-T therapy was successful in Case 3. Multiple studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of CAR-T therapy for relapsed or refractory HGBCL with DHL/THL (43, 44). However, only one case with TdT expression has been reported (45), and in that instance, the patient relapsed after CAR-T therapy, which differs from Case 3. We’re looking forward to more such cases being reported.

5 Conclusion

We propose that MYC rearrangement might play a role in the varying levels of immaturity seen in B-cell lymphoma/leukemia, irrespective of cell origin or other gene mutations. This is evidenced by findings such as weak or missing CD20, negative smIg and light chain, and TdT expression that varies from absent, scattered, weak, focal, to diffuse.Even under the current WHO classification diagnostic criteria, there are some cases of MYC-rearranged B-cell lymphoma/leukemia with aberrant immature features in which it is difficult to determine whether the disease should be diagnosed as B-ALL/LBL or mature BCL. One possible fundamental reason for this diagnostic challenge is that MYC rearrangement may drive B cells to exhibit both tumor proliferative capacity and aberrant immaturity.

Statements

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because data supporting this study’s findings are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. However, due to privacy or ethical restrictions, the data are not publicly available. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to Junya Kuroda, junkuro@koto.kpu-m.ac.jp.

Ethics statement

The study was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards (IRBs) of Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine (ERB-G-C-424-9) and Japanese Red Cross Kyoto Daiichi Hospital. The patient gave informed consent for the study procedures and the publication of the case report. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

DK: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. TF: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. RI: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. HO: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. TT: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SM: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YS: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. TK: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. HU: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. MT: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software. AM-H: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Visualization. JK: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Data curation, Project administration, Software, Supervision, Validation.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients and their families. We thank Ms. Natsumi Sakamoto-Inada for the excellent technical support.

Conflict of interest

JK serves as a consultant for Janssen Pharmaceuticals, AbbVie, Pfizer, BeOne, and Bristol-Myers Squibb BMS, received research funding from Kyowa Kirin, Chugai Pharmaceutical, Japan Blood Product Organization, Asahikasei, and Mochida Pharmaceutical, and received honoraria from Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Kyowa Kirin, Chugai Pharmaceutical, Ono Pharmaceutical, Sanofi, BMS, Novartis, AbbVie, Pfizer, Nippon Shinyaku, BeOne, Amgen, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, and Astellas Pharmaceutical. SM received honoraria from Sanofi and Ono Pharmaceutical. TT received honoraria from BMS, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Sanofi, Kyowa Kirin, and Chugai Pharmaceutical. TF received honoraria from Takeda Pharmaceutical. YS received honoraria from Ono Pharmaceutical, BMS, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Sanofi, Kyowa Kirin, Takeda Pharmaceutical, and Chugai Pharmaceutical.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Grammarly Pro (Grammarly Inc.) was used for English language editing purposes only. The authors have thoroughly reviewed and verified the accuracy and integrity of all AI-generated content.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fonc.2025.1684005/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Figure 1Histopathologic features of the central region of biopsied lymph node in case 1. (A). Follicular lymphoma (FL) component examined by Hematoxylin-Eosin (HE) staining, original magnification ×40. (B). FL component examined by the immunohistochemical staining (IHC) for BCL-2, original magnification ×40.

Supplementary Figure 2Histopathologic features of the biopsied retroperitoneal tumorous lesion in case 2. (A). HE-stained biopsied specimen, original magnification ×40. (B–D). IHC examinations for BCL-2 (×40) (B), BCL-6 (×40) (C), and c-MYC (×40) (D).

Supplementary Figure 3Histopathologic features of the biopsied retroperitoneal tumorous lesion in case 3. HE-stained biopsied specimen, original magnification (×40) (A), and IHC examinations for CD10 (×40) (B), CD79a (×40) (C), PAX-5 (×40) (D), BCL-2 (×40) (E), BCL-6 (×40) (F), and c-MYC (×40) (G).

Supplementary Figure 4Histopathologic features of the bone marrow biopsied specimen in case 4. IHC examinations for CD10 (×40) (A), CD79a (×40) (B), MYC (×40)(C), and BCL-2 (×40) (D).

Supplementary Table 1Clinical, cytogenetic, and immunophenotypic manifestation of aggressive B-cell lymphomas with concomitant MYC rearrangement.

Supplementary Table 2Clinical, cytogenetic, and immunophenotypic manifestation of B-ALL and BCP-ALL with concomitant MYC rearrangement.

References

1

Bhavsar S Liu YC Gibson SE Moore EM Swerdlow SH . Mutational landscape of tdT+ Large B-cell lymphomas supports their distinction from B-lymphoblastic neoplasms. Am J Surg Pathol. (2022) 46:71–82. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000001750

2

Soliman DS Al-Sabbagh A Ibrahim F Taha RY Nawaz Z Elkourashy S et al . High-grade B-cell neoplasm with surface light chain restriction and tdt co expression evolved in a MYC-rearranged diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: A dilemma in classification. Case Rep Hematol. (2017) 2017:6891957. doi: 10.1155/2017/6891957

3

Moench L Sachs Z Aasen G Dolan M Dayton V Courville EL . Double- and triple-hit lymphomas can present with features suggestive of immaturity, including TdT expression, and create diagnostic challenges. Leuk Lymphoma. (2016) 57:2626–35. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2016.1143939

4

Ok CY Medeiros LJ Thakral B Tang G Jain N Jabbour E et al . High-grade B-cell lymphomas with TdT expression: a diagnostic and classification dilemma. Mod Pathol. (2019) 32:48–58. doi: 10.1038/s41379-018-0112-9

5

WHO Classification of Tumours . Hematolymphoid Tumours (2022). Available online at: https://tumourclassification.iarc.who.int/ (Accessed June 20, 2025).

6

Sakaguchi K Imamura T Ishimaru S Imai C Shimonodan H Fujita N et al . NationwidestudyofpediatricB-cellprecursoracute lymphoblastic leukemia with chromosome 8q24/MYC Rearrangement in Japan. Pediatr Blood Cancer. (2020) 67:e28341. doi: 10.1002/pbc.28341

7

Geyer JT Subramaniyam S Jiang Y Elemento O Ferry JA de Leval L et al . Lymphoblastic transformation of follicular lymphoma: a clinicopathologic and molecular analysis of 7 patients. Hum Pathol. (2015) 46:260–71. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2014.10.021

8

Aukema SM Croci GA Bens S Oehl-Huber K Wagener R Ott G et al . Mantle cell lymphomas with concomitant MYC and CCND1 breakpoints are recurrently TdT positive and frequently show high-grade pathological and genetic features. Virchows Arch. (2021) 479:133–45. doi: 10.1007/s00428-021-03022-8

9

Kelemen K Braziel RM Gatter K Bakke TC Olson S Fan G . Immunophenotypic variations of Burkitt lymphoma. Am J Clin Pathol. (2010) 134:127–38. doi: 10.1309/AJCP93LJPTRQPDKR

10

Fujimoto A Ikejiri F Arakawa F Ito S Okada Y Takahashi F et al . Simultaneous discordant B-lymphoblastic lymphoma and follicular lymphoma. Am J Clin Pathol. (2021) 155:308–17. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/aqaa126

11

Liu H Xu-Monette ZY Tang G Wang W Kim Y Yuan J et al . EBV+ high-grade B cell lymphoma with MYC and BCL2 and/or BCL6 rearrangements: a multi-institutional study. Histopathology. (2022) 80:575–88. doi: 10.1111/his.14585

12

Wang W Hu S Lu X Young KH Medeiros LJ . Triple-hit B-cell lymphoma with MYC, BCL2, and BCL6 translocations/rearrangements: clinicopathologic features of 11 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. (2015) 39:1132–9. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000434

13

Snuderl M Kolman OK Chen YB Hsu JJ Ackerman AM Dal Cin P et al . B-cell lymphomas with concurrent IGH-BCL2 and MYC rearrangements are aggressive neoplasms with clinical and pathologic features distinct from Burkitt lymphoma and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Am J Surg Pathol. (2010) 34:327–40. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181cd3aeb

14

Bischin AM Dorer R Aboulafia DM . Transformation of follicular lymphoma to a high-grade B-cell lymphoma with MYC and BCL2 translocations and overlapping features of burkitt lymphoma and acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A case report and literature review. Clin Med Insights Blood Disord. (2017) 10:1179545X17692544. doi: 10.1177/1179545X17692544

15

Slot LM Hoogeboom R Smit LA Wormhoudt TA Biemond BJ Oud ME et al . B-lymphoblastic lymphomas evolving from follicular lymphomas co-express surrogate light chains and mutated gamma heavy chains. Am J Surg Pathol. (2016) 186:3273–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2016.07.027

16

Meznarich J Miles R Paxton CN Afify Z . Pediatric B-cell lymphoma with lymphoblastic morphology, tdT expression, MYC rearrangement, and features overlapping with burkitt lymphoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer. (2016) 63:938–40. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25907

17

Mufti GJ Hamblin TJ Oscier DG Johnson S . Common ALL with pre-B-cell features showing (8;14) and (14;18) chromosome translocations. Blood. (1983) 62:1142–6. doi: 10.1182/blood.V62.5.1142.1142

18

Hirzel AC Cotrell A Gasparini R Sriganeshan V . Precursor B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma with L3 morphology, philadelphia chromosome, MYC gene translocation, and coexpression of tdT and surface light chains: A case report. Case Rep Pathol. (2013) 2013:679892. doi: 10.1155/2013/679892

19

Higa B Alkan S Barton K Velankar M . Precursor B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia with FAB L3 (i.e., Burkitt’s leukaemia/lymphoma) morphology and co-expression of monoclonal surface light chains and Tdt: report of a unique case and review of the literature. Pathology. (2009) 41:495–8. doi: 10.1080/00313020903040988

20

Drexler HG Messmore HL Menon M Minowada J . A case of TdT-positive B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Am J Clin Pathol. (1986) 85:735–8. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/85.6.735

21

Secker-Walker L Stewart E Norton J Campana D Thomas A Hoffbrand V et al . Multiple chromosome abnormalities in a drug resistant TdT positive B-cell leukemia. Leuk Res. (1987) 11:155–61. doi: 10.1016/0145-2126(87)90021-x

22

Loh ML Samson Y Motte E Moreau LA Dalton V Waters S et al . Translocation (2;8)(p12;q24) associated with a cryptic t(12;21)(p13;q22) TEL/AML1 gene rearrangement in a child with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. (2000) 122:79–82. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(00)00293-4

23

Meeker ND Cherry AM Bangs CD Frazer JK . A pediatric B lineage leukemia with coincident MYC and MLL translocations. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. (2011) 33:158–60. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e3181e65c39

24

Li Y Gupta G Molofsky A Xie Y Shihabi N McCormick J et al . B Lymphoblastic Leukemia/Lymphoma with Burkitt-like morphology and IGH/MYC rearrangement: report of three cases in adult patients. Am J Surg Pathol. (2018) 42:269–76. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000982

25

Navid F Mosijczuk AD Head DR Borowitz MJ Carroll AJ Brandt JM et al . Acute lymphoblastic leukemia with the (8;14)(q24;q32) translocation and FAB L3 morphology associated with a B-precursor immunophenotype: the Pediatric Oncology Group experience. Leukemia. (1999) 13:135–41. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2401244

26

Rawlinson NJ Baker P Kahwash SB . Burkitt’s leukemia with an atypical immunophenotype: report of a case and review of literature. Lab Hematol. (2011) 17:27–31. doi: 10.1532/LH96.11004

27

Hassan R Felisbino F Stefanoff CG Pires V Klumb CE Dobbin J et al . Burkitt lymphoma/leukaemia transformed from a precursor B cell: clinical and molecular aspects. Eur J Haematol. (2008) 80:265–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2007.00992.x

28

Sato Y Kurosawa H Fukushima K Okuya M Arisaka O . Burkitt-type acute lymphoblastic leukemia with precursor B-cell immunophenotype and partial tetrasomy of 1q: A case report. Med (Baltimore). (2016) 95:e2904. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000002904

29

Gupta AA Grant R Shago M Abdelhaleem M . Occurrence of t(8;22)(q24.1;q11.2) involving the MYC locus in a case of pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia with a precursor B cell immunophenotype. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. (2004) 26:532–4. doi: 10.1097/01.mph.0000132736.31514.28

30

Herbrueggen H Mueller S Rohde J Arias Padilla L Moericke A Attarbaschi A et al . Treatment and outcome of IG-MYC+ neoplasms with precursor B-cell phenotype in childhood and adolescence. Leukemia. (2020) 34:942–6. doi: 10.1038/s41375-019-0606-6

31

Pegoraro L Palumbo A Erikson J Falda M Giovanazzo B Emanuel BS et al . A 14;18 and an 8;14 chromosome translocation in a cell line derived from an acute B-cell leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. (1984) 81:7166–70. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.22.7166

32

Uemura S Hasegawa D Yokoi T Nino N Tahara T Tamura A et al . Refractory double-hit lymphoma/leukemia in childhood mimicking B-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia at initial presentation. Rinsho Ketsueki. (2017) 58:143–9. doi: 10.11406/rinketsu.58.143

33

Liu W Hu S Konopleva M Khoury JD Kalhor N Tang G et al . De novo MYC and BCL2 double-hit B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia (BCP-ALL) in pediatric and young adult patients associated with poor prognosis. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. (2015) 32:535–47. doi: 10.3109/08880018.2015.1087611

34

Drexler HG Menon M Minowada J . Incidence of TdT positivity in cases of leukemia and lymphoma. Acta Haematol. (1986) 75:12–7. doi: 10.1159/000206072

35

Bhavsar S Gibson S Moore E Swerdlow S . Frequency and significance of tdT expression in large B-cell lymphomas. Abstracts from USCAP 2019: hematopathology (1234-1434). Mod Pathol. (2019) 32:9–11. doi: 10.1038/s41379-019-0227-7

36

Qiu L Xu J Lin P Cohen EN Tang G Wang SA et al . Unique pathologic features and gene expression signatures distinguish blastoid high-grade B-cell lymphoma from B-acute lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma. Haematologica. (2023) 108:895–9. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2022.281646

37

Khanlari M Medeiros LJ Lin P Xu J You MJ Tang G et al . Blastoid high-grade B-cell lymphoma initially presenting in bone marrow: a diagnostic challenge. Mod Pathol. (2022) 35:419–26. doi: 10.1038/s41379-021-00909-4

38

Rodriguez-Pinilla SM Dojcinov S Dotlic S Gibson SE Hartmann S Klimkowska M et al . Aggressive B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas: a report of the lymphoma workshop of the 20th meeting of the European Association for Haematopathology. Virchows Arch. (2024) 484:15–29. doi: 10.1007/s00428-023-03579-6

39

Wu D Wood BL Dorer R Fromm JR . Double-Hit” mature B-cell lymphomas show a common immunophenotype by flow cytometry that includes decreased CD20 expression. Am J Clin Pathol. (2010) 134:258–65. doi: 10.1309/AJCP7YLDTJPLCE5F

40

Paietta E Roberts KG Wang V Gu Z Buck GAN Pei D et al . Molecular classification improves risk assessment in adult BCR-ABL1-negative B-ALL. Blood. (2021) 138:948–58. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020010144

41

Bomken S Enshaei A Schwalbe EC Mikulasova A Dai Y Zaka M et al . Molecular characterization and clinical outcome of B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia with IG-MYC rearrangement. Haematologica. (2023) 108:717–31. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2021.280557

42

Sajaroff EO Mansini A Rubio P Alonso CN Gallego MS Coccé MC et al . B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia with mature phenotype and MLL rearrangement: report of five new cases and review of the literature. Leuk Lymphoma. (2016) 57:2289–97. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2016.1141407

43

Kamdar M Solomon SR Arnason J Johnston PB Glass B Bachanova V et al . Lisocabtagene maraleucel versus standard of care with salvage chemotherapy followed by autologous stem cell transplantation as second-line treatment in patients with relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphoma (TRANSFORM): results from an interim analysis of an open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet. (2022) 399:2294–308. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00662-6

44

Ghafouri S Fenerty K Schiller G de Vos S Eradat H Timmerman J et al . Real-world experience of axicabtagene ciloleucel and tisagenlecleucel for relapsed or refractory aggressive B-cell lymphomas: A single-institution experience. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. (2021) 21:861–72. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2021.07.002

45

Singh A Asghar I Kohler L Snower D Hakim H Lebovic D et al . TdT positive lymphoma with MYC, BCL2 and BCL6 rearrangements: A review of diagnosis and treatment. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. (2022) 14:e2022018. doi: 10.4084/MJHID.2022.018

Summary

Keywords

B-cell lymphoma, MYC rearrangement, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase, CD20, immunophenotypic immaturity, surface membrane immunoglobulin

Citation

Kato D, Fujino T, Isa R, Okamoto H, Tsukamoto T, Mizutani S, Shimura Y, Kobayashi T, Uchiyama H, Taniwaki M, Miyagawa-Hayashino A and Kuroda J (2025) Case Report: Immunophenotypically diverse immature patterns, including variable TdT expression, in aggressive B-cell lymphomas and leukemia with MYC rearrangement. Front. Oncol. 15:1684005. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2025.1684005

Received

12 August 2025

Accepted

29 September 2025

Published

09 October 2025

Volume

15 - 2025

Edited by

Robert Ohgami, The University of Utah, United States

Reviewed by

Sayalee Potdar, Emory University, United States

Shih-Sung Chuang, Chi Mei Medical Center, Taiwan

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Kato, Fujino, Isa, Okamoto, Tsukamoto, Mizutani, Shimura, Kobayashi, Uchiyama, Taniwaki, Miyagawa-Hayashino and Kuroda.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Junya Kuroda, junkuro@koto.kpu-m.ac.jp

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.