- 1Department of Interventional Radiology, The First People’s Hospital of Linhai, Linhai, China

- 2Department of Radiology, Xuzhou Central Hospital, Xuzhou, China

- 3Department of General Surgery, The First People’s Hospital of Linhai, Linhai, China

Background: Transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) and systemic therapy are frequently applied for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), but their combined therapeutic potential remains uncertain. Here, the clinical efficacy and safety of TACE together with rivoceranib plus camrelizumab in Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) stage C HCC were investigated.

Methods: Between January 2021 and December 2024, 167 consecutive cases of BCLC stage C HCC were retrospectively analyzed. Eighty-three received rivoceranib-camrelizumab with TACE, and 84 received rivoceranib-camrelizumab alone. Comparisons of baseline characteristics, tumor response, long-term outcomes, and adverse events were conducted.

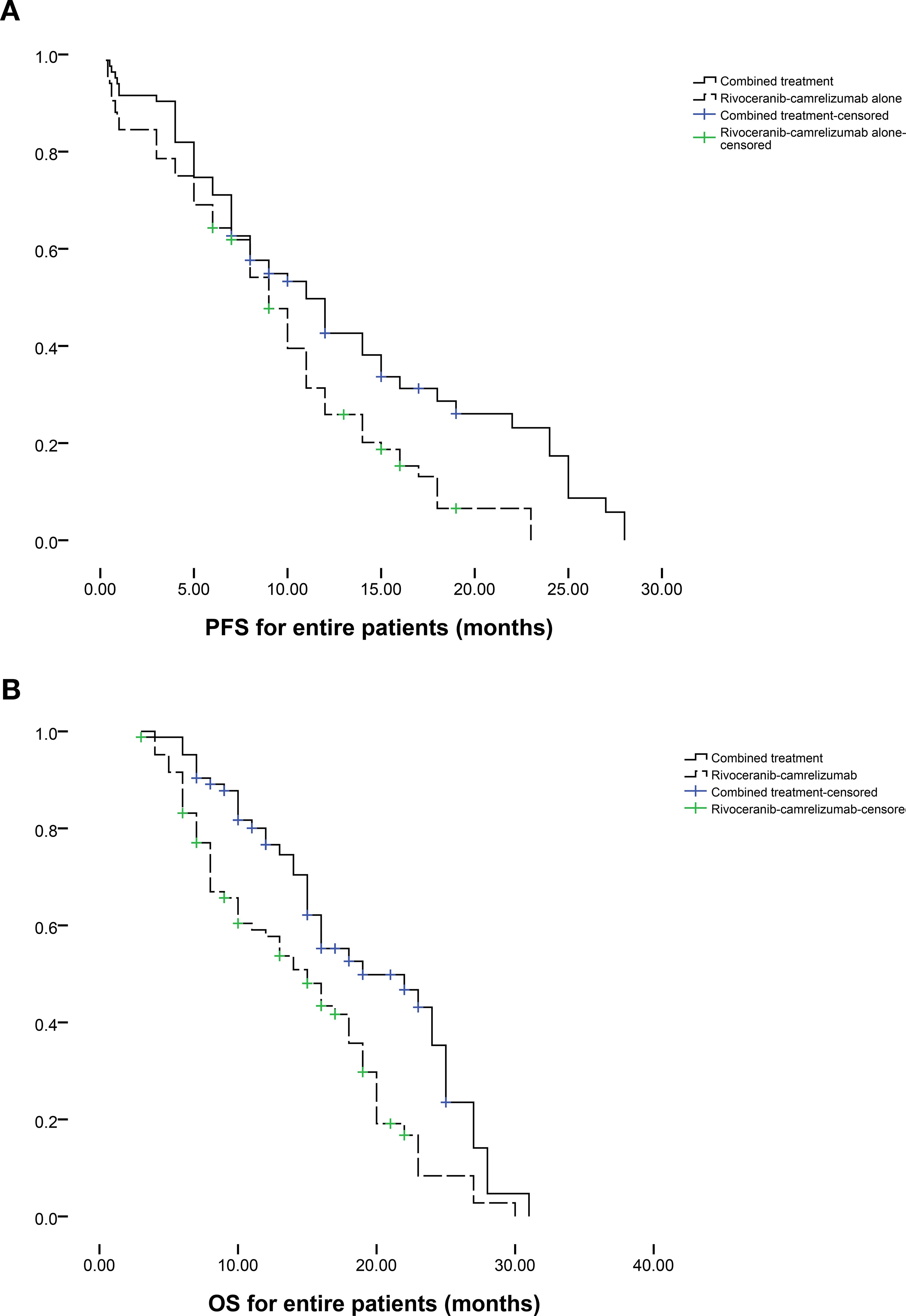

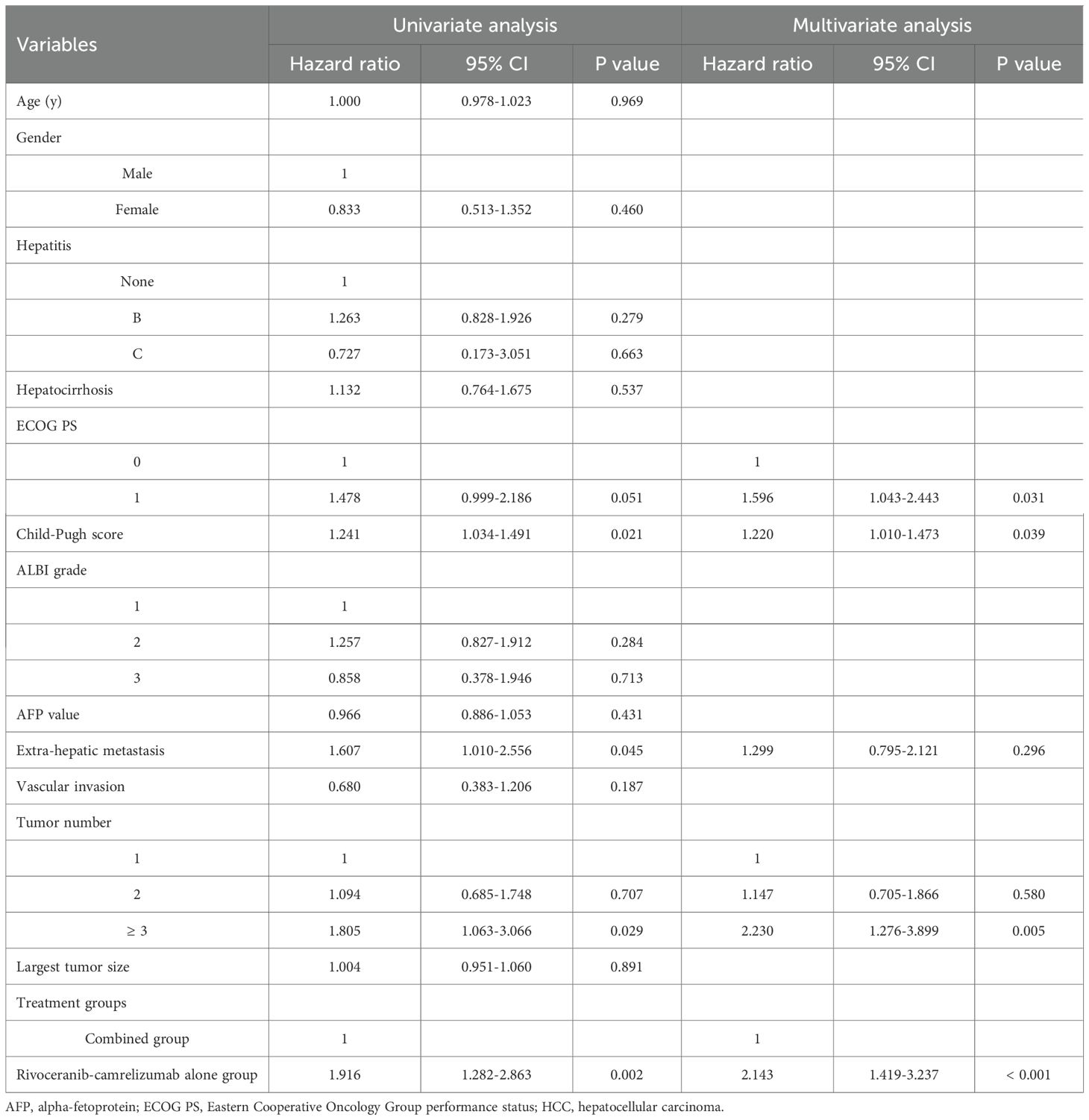

Results: Baseline variables were balanced between groups. Combination therapy achieved significantly higher partial (39.8% vs. 20.2%, P = 0.006) and objective response rates (50.6% vs. 29.7%, P = 0.006) than systemic therapy alone. Median progression-free survival (PFS: 11.0 vs. 9.0 months, P = 0.008) and overall survival (OS: 19.0 vs. 15.0 months, P = 0.001) were both longer in the combination group. Cox regression identified combined treatment as an independent predictor of extended PFS and OS. Post-embolization symptoms occurred only in the TACE group but no grade 3-4 events were observed, and rates of systemic treatment-related adverse events were comparable between groups.

Conclusions: Adding TACE to rivoceranib-camrelizumab has the potential to improve tumor response and survival in BCLC stage C HCC without compromising safety.

Introduction

Despite its global prevalence, the curative resection of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) lesions is feasible in only about 20% of patients (1, 2). In 2023, the Asia-Pacific HCC Trials Group showed that 7% to44% of HCC patients presented with Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) stage C disease at diagnosis in the Asia-Pacific regions (3). Among the Asia-Pacific regions, China had the highest incident rate (44%) of BCLC stage C HCC (3). According to BCLC guidelines, systemic therapy is the recommended first-line approach for these patients (4–6).

Contemporary systemic regimens for HCC increasingly combine tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) with immune checkpoint inhibitors (4–6). Until recently, sorafenib and lenvatinib were the standard first-line TKIs in this context (6). However, in 2023, the CARES-310 trial demonstrated that rivoceranib plus camrelizumab significantly improved both progression-free survival (PFS: 5.6 vs. 3.7 months, P < 0.001) and overall survival (OS: 22.1 vs. 15.2 months, P < 0.001) in comparison with sorafenib in unresectable HCC (6), establishing this combination as a novel first-line standard (6).

Despite advances in systemic therapy, local interventions remain central to HCC management (7). Transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) is the most frequently employed locoregional therapy (7), and recent studies have suggested additive benefits when TACE is combined with lenvatinib or lenvatinib-camrelizumab (4, 5). However, whether TACE can similarly enhance outcomes with rivoceranib-camrelizumab remains untested.

Here, the efficacy and safety of the combination of TACE and rivoceranib-camrelizumab in BCLC stage C HCC were investigated.

Methods

Study design

This single-center study retrospective received approval from the The First People’s Hospital of Linhai City Ethics Committee (Linyilunshen-2024-002) and performed as per the Declaration of Helsinki. Given its retrospective nature, written informed consent requirements for this study were waived.

From January 2021 to December 2024, we included 167 consecutive patients with BCLC stage C HCC who received rivoceranib-camrelizumab with (n = 83) or without TACE (n = 84). The patients chose combined treatment or rivoceranib-camrelizumab alone treatment based on their family economic condition. Baseline demographics, treatment response, survival outcomes, and adverse events were recorded.

Inclusion criteria were: (a) confirmed BCLC stage C HCC; (b) Child-Pugh class A or B liver function; (c) Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status 0-1; and (d) at least one measurable lesion per modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (mRECIST) criteria. Exclusion criteria included: (a) age <18 or >80 years; (b) prior anticancer therapy for HCC; (c) concomitant malignancy; or (d) complete main-portal-vein tumor thrombus because this is the contraindication for TACE.

American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases guidelines were used for HCC diagnosis (8). Collected data included age, sex, hepatitis status, liver function tests, ECOG score, imaging findings, treatment response, PFS, OS, and adverse events.

Treatments and follow-up

In the combination group, conventional TACE was performed first (details in Supplementary Materials), followed approximately 10 days later by rivoceranib-camrelizumab therapy. Patients in the monotherapy group received rivoceranib-camrelizumab alone.

All patients were monitored at 1, 3, and 6 months, then every 3 months until death, loss to follow-up, or June 30, 2025. Subsequent interventions including ablation, radiotherapy, or alternative systemic therapies were permitted after tumor progression. Follow-up assessments involved complete blood counts, coagulation profiling, tests for liver and kidney function, serum electrolytes, and computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans. Tumor response was evaluated as per the mRECIST criteria. The first evaluation of tumor response was performed at 1 month, then every 3 months after treatment with the contrast-medium enhanced CT and/or MRI. PFS represented the interval between the start of treatment and documented progression, death, or final follow-up, while OS was measured from initiation of treatment to death or final follow-up. Adverse events were graded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria (version 5.0).

Statistical analyses

Means ± standard deviation or medians (interquartile range) are used when reporting continuous variables, which were compared as appropriate with t-tests or Mann-Whitney U tests, while categorical variables were assessed with χ² or Fisher’s exact tests. PFS and OS were evaluated with Kaplan-Meier curves and log-rank tests. Risk factors for OS were explored via a Cox regression approach, in which factors with P < 0.1 in the univariate analyses were retained for multivariate analysis. SPSS 16.0 was used for all statistical testing.

Results

Participant characteristics

Baseline clinical data for all 167 patients are presented in Table 1, and the patient selection process is depicted in Figure 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics were well balanced between the cohorts, indicating no significant baseline differences.

Treatment response

Treatment response outcomes are detailed in Table 2. Compared with rivoceranib-camrelizumab alone, the combination of TACE with rivoceranib-camrelizumab resulted in a markedly higher partial response rate (39.8% vs. 20.2%, P = 0.006) and a superior overall objective response rate (50.6% vs. 29.7%, P = 0.006). Rates of complete response (10.8% vs. 9.5%, P = 0.778), stable disease (42.2% vs. 54.8%, P = 0.104), and progressive disease (7.6% vs. 15.5%, P = 0.093) were comparable between groups.

Table 2. Treatment response based on modified response evaluation criteria in solid tumors criteria.

Survival

Patients follow-up intervals ranged from 3-31 months (median 12 months). During follow-up, tumor progression occurred in 42 individuals in the combination group and 53 in the rivoceranib-camrelizumab group. The median PFS was markedly longer in the combination group (11.0 vs. 9.0 months, P = 0.008; Figure 2a). The one- and two-year rates of PFS were 42.6% and 25.9% for the combination group versus 17.4% and 0% for the monotherapy group, respectively. Among those who progressed in the combination group, 14 underwent microwave ablation, 13 received radioactive seed implantation, and the remainder received conservative care. For patients progressing on rivoceranib-camrelizumab alone, 13 underwent TACE, 12 received hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy, 8 underwent microwave ablation, 6 received radioactive seed placement, and the remaining patients were managed conservatively. Female sex (P = 0.058), ECOG performance status (PS) of 0 (P = 0.089), lower Child-Pugh score (P = 0.033), no extrahepatic metastasis (P = 0.086), and combined therapy (P = 0.011) were correlated with longer PFS in univariate analyses. Multivariate analysis confirmed that combined treatment independently predicted improved PFS (P = 0.012, Table 3).

At the end of follow-up, 41 deaths had occurred in the combination group and 63 in the rivoceranib-camrelizumab group. The median OS was prolonged substantially in the combination group (19.0 vs. 15.0 months, P = 0.001; Figure 2b). One- and two-year OS rates were 76.6% and 57.7% for the combined-treatment group versus 35.3% and 8.4% for the single-treatment group. Univariate Cox regression revealed associations between longer OS and ECOG PS 0 (P = 0.051), lower Child-Pugh score (P = 0.021), absence of extrahepatic metastasis (P = 0.045), and combined therapy (P = 0.002). The tumor number ≥ 3 was the predictor of shorter OS (P = 0.029). Multivariate analysis again identified that ECOG PS 0 (P = 0.031), lower Child-Pugh score (P = 0.039), and combined therapy were predictors of prolonged OS (P < 0.001). The tumor number ≥ 3 was the predictor of shorter OS (P = 0.005, Table 4).

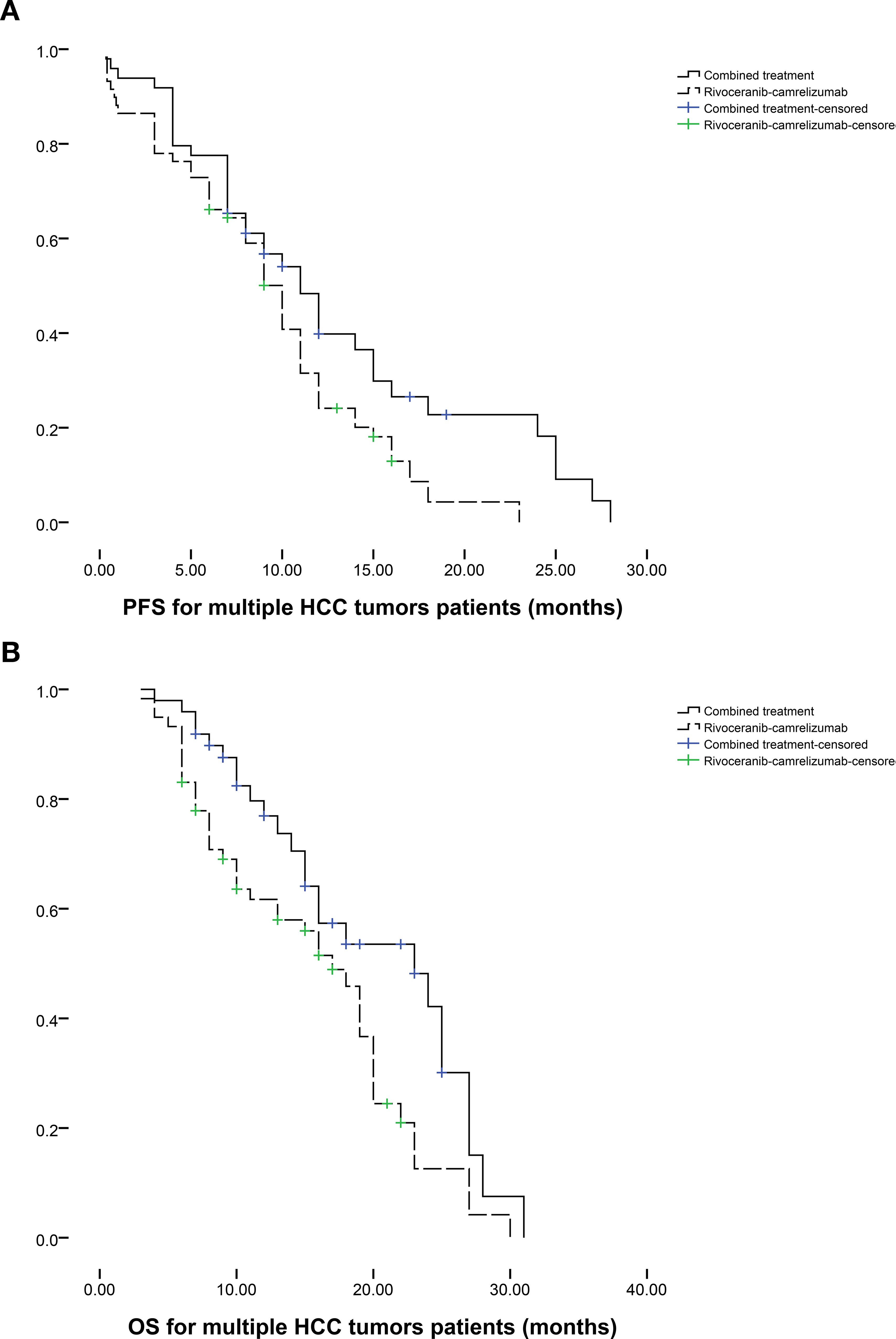

Subgroup analyses stratified by tumor number further supported these findings. Among patients with a single HCC lesion (n = 34 in the combination group; n = 25 in the monotherapy group), median PFS favored the combination group (12 vs. 8 months, P = 0.095; Figure 3a), while median OS was significantly improved (19 vs. 12 months, P = 0.003; Figure 3b). In patients with multiple tumors (n = 49 vs. n = 59), both PFS (11 vs. 10 months, P = 0.039; Figure 4a) and OS (23 vs. 17 months, P = 0.019; Figure 4b) were prolonged substantially in the combination group.

Figure 3. The comparison of (a) PFS and (b) OS between 2 groups based on the patients with single HCC tumor.

Figure 4. The comparison of (a) PFS and (b) OS between 2 groups based on the patients with multiple HCC tumors.

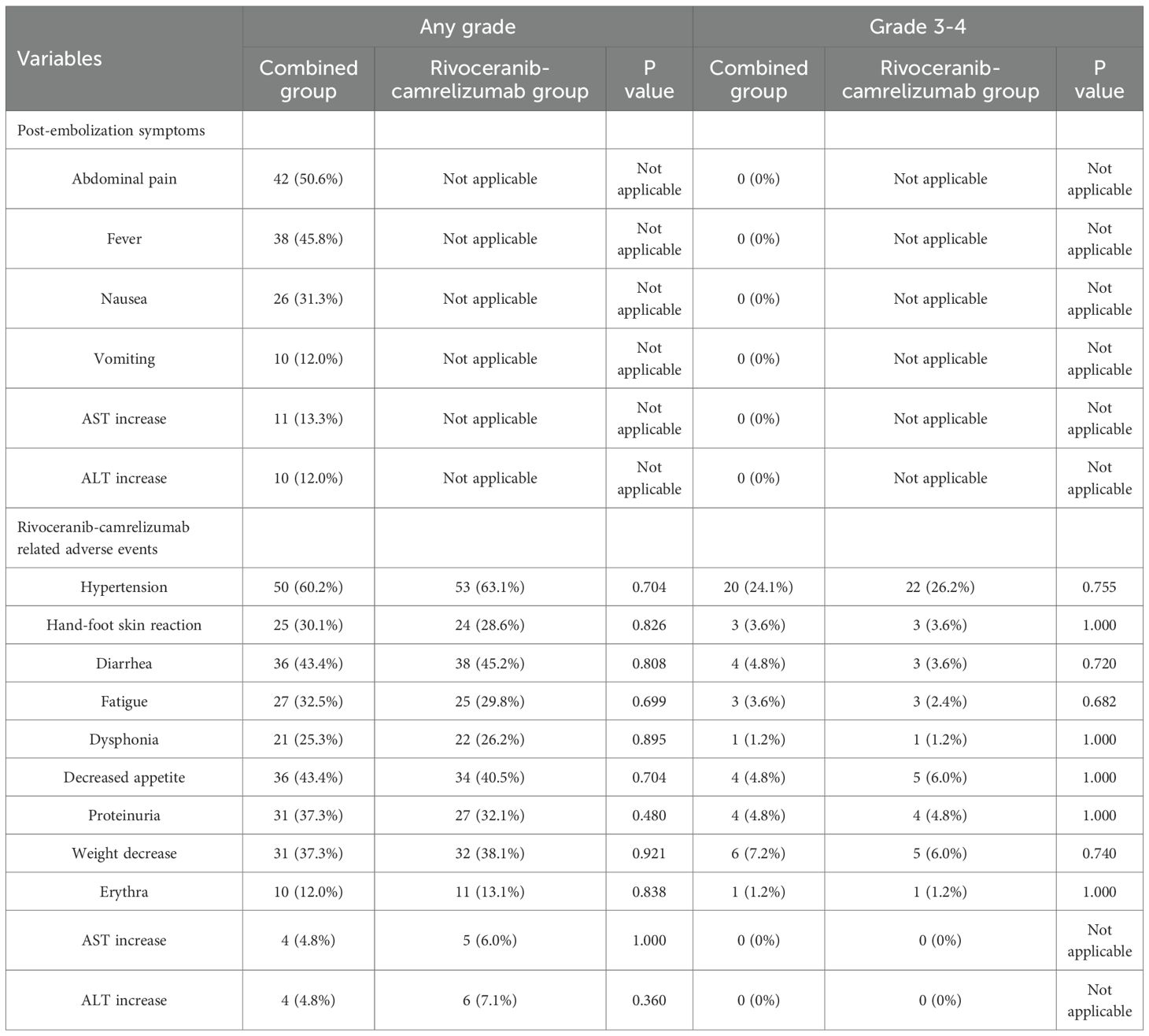

Adverse events

Adverse event profiles are summarized in Table 5. As expected, TACE-specific post-embolization symptoms occurred only in the combination group but were limited to grade 1-2 severity, and no grade 3-4 post-embolization reactions were observed. The incidence of rivoceranib-camrelizumab-related toxicities was similar between the two cohorts (Table 5).

Discussion

Patients diagnosed with BCLC stage C HCC generally have little opportunity for curative resection, making systemic therapy the cornerstone of first-line treatment (3, 9, 10). Historically, the TKIs sorafenib and Lenvatinib represented the standard of care but provided only modest survival advantages (11–13). More recently, PD-1 or PD-L1 checkpoint inhibitors have exhibited favorable efficacy and tolerability profiles in advanced HCC (14, 15).

Rivoceranib is a highly selective, small-molecule TKI directed against VEGFR2. It exerts antitumor activity not only by blocking tumor cell proliferation and neovascularization but also by counteracting the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (6). Compared with sorafenib, rivoceranib demonstrates stronger VEGFR2 specificity (16). The humanized IgG4 monoclonal antibody camrelizumab binds with high affinity to PD-1 binding (17). Together, rivoceranib and camrelizumab act synergistically, and their combination has emerged as a novel first-line regimen for advanced HCC (6).

TACE is the most frequently employed locoregional therapy in the context of HCC management (7). However, TACE induces intratumoral hypoxia, which upregulates vascular endothelial growth factor expression and promotes angiogenesis, potentially facilitating tumor progression or metastasis (16, 18). As a result, TACE is often paired with TKIs to offset these effects and enhance antitumor efficacy (9, 16). In the present study, combining TACE with rivoceranib-camrelizumab yielded a substantially higher objective response rate than rivoceranib-camrelizumab alone (50.6% vs. 29.7%, P = 0.006). This finding aligns with Wu et al. (4), who reported superior response rates with TACE plus systemic therapy compared to TACE alone (57.9% vs. 32.6%, P = 0.012) in BCLC stage C patients. However, the result of objective response rate in this present study may be influenced by several factors, such as the retrospective design, potential selection bias, and limited baseline tumor burden characterization. Therefore, further well designed prospective clinical trials should be conducted to validate this result.

Multivariate Cox regression conducted herein confirmed that combined therapy independently predicted longer PFS and OS, supporting a synergistic interaction between TACE and rivoceranib-camrelizumab. Locoregional therapy may potentiate immune checkpoint inhibition by releasing tumor antigens and reshaping the microenvironment, thereby improving immunotherapy responsiveness (19). Here, the median PFS and OS values in the combination group were 11 and 19 months, respectively, which were shorter than the 13.5-month PFS and 24.1-month OS reported in the CHANCE2211 trial (19). This difference likely reflects our exclusive enrollment of BCLC stage C patients, whereas CHANCE2211 included both stage B and C populations.

Furthermore, ECOG PS 0 and lower Child-Pugh score were also the predictors of longer OS, while tumor number ≥ 3 was the predictor of shorter OS in this study. ECOG PS and Child-Pugh score indicate the patients’ body condition and liver function, which are significantly associated with OS. Tumor number is an important factor of tumor burden. Larger tumor burden usually indicates shorter OS (20).

Subgroup analyses further demonstrated consistent benefits of the combined regimen in patients with either single or multiple tumors. Both single and multiple HCC tumor patients exhibited longer PFS and OS in combined group than rivoceranib-camrelizumab alone group. Although PFS improvement did not reach statistical significance in the single-tumor subgroup, the P value of 0.095 also had the tendency of significance. This result may be attributed to the limited sample size rather than absence of effect. Notably, Cox regression did not identify tumor number as a determinant of PFS or OS. These findings indicated that the treatment efficacy of combined treatment may not be influenced by the number of tumors.

Although TACE inevitably introduces post-embolization symptoms, these were mild and transient, with no grade 3-4 events observed (21). The incidence of systemic therapy-related adverse events did not differ significantly between groups, suggesting that adding TACE does not compromise the safety profile of rivoceranib-camrelizumab.

This study has limitations. First, its retrospective design raises potential for selection bias and unmeasured confounders. Prospective randomized trials are warranted to validate our findings. Second, being a single-center investigation limits generalizability, underscoring the need for multicenter studies. Third, the modest sample size may have reduced the power to detect some subgroup differences.

Conclusion

In summary, our analysis suggests that incorporating TACE into rivoceranib-camrelizumab therapy can enhance clinical efficacy for BCLC stage C HCC without increasing toxicity.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by The First People’s Hospital of Linhai City Ethics Committee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The ethics committee/institutional review board waived the requirement of written informed consent for participation from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin because this is a retrospective study.

Author contributions

RZ: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Methodology. Z-XZ: Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Software. X-ZL: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. KM: Methodology, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fonc.2025.1710686/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Villanueva A. Hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. (2019) 380:1450–62. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1713263

2. Forner A, Reig M, and Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. (2018) 391:1301–14. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30010-2

3. Sim YK, Chong MC, Gandhi M, Pokharkar YM, Zhu Y, Shi L, et al. Real-world data on the diagnosis, treatment, and management of hepatocellular carcinoma in the asia-pacific: the INSIGHT study. Liver Can. (2023) 13:298–313. doi: 10.1159/000534513

4. Wu J, Zeng J, Wang H, Huo Z, Hou X, and He D. Efficacy and safety of transarterial chemoembolization combined with lenvatinib and camrelizumab in patients with BCLC-defined stage C hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Oncol. (2023) 13:1244341. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2023.1244341

5. Jin ZC, Chen JJ, Zhu XL, Duan XH, Xin YJ, Zhong BY, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors and anti-vascular endothelial growth factor antibody/tyrosine kinase inhibitors with or without transarterial chemoembolization as first-line treatment for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (CHANCE2201): a target trial emulation study. EClinicalMedicine. (2024) 72:102622. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2024.102622

6. Qin S, Chan SL, Gu S, Bai Y, Ren Z, Lin X, et al. Camrelizumab plus rivoceranib versus sorafenib as first-line therapy for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (CARES-310): a randomised, open-label, international phase 3 study. Lancet. (2023) 402:1133–46. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00961-3

7. Titano J, Noor A, and Kim E. Transarterial chemoembolization and radioembolization across barcelona clinic liver cancer stages. Semin Intervent Radiol. (2017) 34:109–15. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1602709

8. Chalasani N, Younossi Z, Lavine JE, Charlton M, Cusi K, Rinella M, et al. The diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Practice guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. (2018) 67:328–57. doi: 10.1002/hep.29367

9. Zhu HD, Li HL, Huang MS, Yang WZ, Yin GW, Zhong BY, et al. Transarterial chemoembolization with PD-(L)1 inhibitors plus molecular targeted therapies for hepatocellular carcinoma (CHANCE001). Signal Transduct Target Ther. (2023) 8:58. doi: 10.1038/s41392-022-01235-0

10. Peng Z, Fan W, Zhu B, Wang G, Sun J, Xiao C, et al. Lenvatinib combined with transarterial chemoembolization as first-line treatment for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: A phase III, randomized clinical trial (LAUNCH). J Clin Oncol. (2023) 41:117–27. doi: 10.1200/JCO.22.00392

11. Kudo M, Finn RS, Qin S, Han KH, Ikeda K, Piscaglia F, et al. Lenvatinib versus sorafenib in first-line treatment of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet. (2018) 391:1163–73. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30207-1

12. Cheng AL, Kang YK, Chen Z, Tsao CJ, Qin S, Kim JS, et al. Efficacy and safety of sorafenib in patients in the Asia-Pacific region with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a phase III randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. (2009) 10:25–34. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70285-7

13. Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, Hilgard P, Gane E, Blanc JF, et al. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. (2008) 359:378–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708857

14. Qin S, Ren Z, Meng Z, Chen Z, Chai X, Xiong J, et al. Camrelizumab in patients with previously treated advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a multicentre, open-label, parallel-group, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. (2020) 21:571–80. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30011-5

15. Zhu AX, Finn RS, Edeline J, Cattan S, Ogasawara S, Palmer D, et al. Pembrolizumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma previously treated with sorafenib (KEYNOTE-224): a non-randomised, open-label phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. (2018) 19:940–52. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30351-6

16. Gu J, Ma L, Zhang Z, Zhu X, Xu G, and Du C. TACE plus apatinib and camrelizumab versus TACE plus apatinib for CNLC Stage III hepatocellular carcinoma:comparison of the clinical efficacy and safety. J Intervent Radiol. (2025) 34:756–61. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1008-794X.2025.07.013

17. Markham A and Keam SJ. Camrelizumab: first global approval. Drugs. (2019) 79:1355–61. doi: 10.1007/s40265-019-01167-0

18. Qiu Z, Shen L, Chen S, Qi H, Cao F, Xie L, et al. Efficacy of apatinib in transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE) refractory intermediate and advanced-stage hepatocellular carcinoma:A propensity score matching analysis. Cancer Manag Res. (2019) 11:9321–30. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S223271

19. Jin ZC, Zhong BY, Chen JJ, Zhu HD, Sun JH, Yin GW, et al. Real-world efficacy and safety of TACE plus camrelizumab and apatinib in patients with HCC (CHANCE2211): a propensity score matching study. Eur Radiol. (2023) 33:8669–81. doi: 10.1007/s00330-023-09754-2

20. Han G, Berhane S, Toyoda H, Bettinger D, Elshaarawy O, Chan AWH, et al. Prediction of survival among patients receiving transarterial chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma: A response-based approach. Hepatology. (2020) 72:198–212. doi: 10.1002/hep.31022

Keywords: transarterial chemoembolization, camrelizumab, rivoceranib, hepatocellular carcinoma, intervention

Citation: Zhu R, Zhang Z-X, Lu X-Z and Mao K (2025) Transarterial chemoembolization with rivoceranib and camrelizumab for BCLC stage C hepatocellular carcinoma. Front. Oncol. 15:1710686. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2025.1710686

Received: 22 September 2025; Accepted: 27 November 2025; Revised: 23 November 2025;

Published: 10 December 2025.

Edited by:

Bin-Yan Zhong, The First Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University, ChinaReviewed by:

Yanqiao Ren, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, ChinaSang Yi Moon, Dong-A University, Republic of Korea

Copyright © 2025 Zhu, Zhang, Lu and Mao. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Rui Zhu, emh1cjA4MTJAMTYzLmNvbQ==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Rui Zhu

Rui Zhu Zi-Xuan Zhang2†

Zi-Xuan Zhang2†