Abstract

Persistent leukocytosis, massive splenomegaly, and eosinophilia are common manifestations in patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs), particularly in those with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML). CML is characterized by the BCR::ABL fusion gene, typically associated with the t(9;22)(q34;q11) translocation. Herein, we report a case of myeloid neoplasm with a rare variant translocation, t(4;22)(q12;q11), involving the BCR::PDGFRA fusion gene and coexisting PDGFRA variants, accompanied by persistent leukocytosis, massive splenomegaly, and eosinophilia. Laboratory tests showed elevated white blood cell counts, with increased monocytes, neutrophils, and eosinophils. Bone marrow aspiration revealed a granulocytic-erythrocytic ratio of 189:1, marked granulocytic hyperplasia, and numerous immature granulocytes. Genetic testing confirmed an uncommon BCR::PDGFRA and coexisting PDGFRA mutations (c.1666G>A and c.1701A>G), confirming the diagnosis of myeloid neoplasm with BCR::PDGFRA rearrangement. Treatment with imatinib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, resulted in a continuous complete molecular response (CMR). To our knowledge, this is the first report to demonstrate the clinical and cytogenetic manifestations of BCR::PDGFRA positive myeloid neoplasm coexisting PDGFRA mutations. Furthermore, it emphasizes the effectiveness of targeted therapy and the significance of personalized management.

Introduction

Myeloid neoplasms, characterized by abnormal proliferation and accumulation of myeloid cells, require an integrated diagnostic approach encompassing clinical presentation, peripheral blood analysis, bone marrow examination, and cytogenetic/molecular testing to prevent misdiagnosis (1). The breakpoint cluster region (BCR) gene, located on chromosome 22q11, fused with the Abelson murine leukemia (ABL) gene on chromosome 9q34, is the hallmark of chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) (2, 3). Previous reports indicate that BCR cytogenetic variants do not always involve BCR::ABL fusion gene (two separate genes abnormally join together, forming a novel fusion gene); instead, BCR has been shown to fuse with other tyrosine kinase genes, including fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 (FGFR1), platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha (PDGFRA), ret proto-oncogene (RET), and JAK2 (4). The most common BCR fusion is BCR::ABL, while BCR::PDGFRA is rare. BCR::PDGFRA was first identified in patients with atypical chronic myeloid leukemia (aCML) associated with the t(4;22)(q12;q11) translocation (5). This disorder type is classified under Myeloid/Lymphoid neoplasms with eosinophilia and tyrosine kinase gene fusions (MLN-TK), a new entity defined in the WHO 2022 Classification of Hematolymphoid Tumors and is labeled as sensitive to tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs, a class of targeted drugs that block the activity of abnormal proteins driving cancer growth) (6, 7). Otherwise, an activating mutation of PDGFRA is also sensitive to TKIs. Therefore, identifying rare fusion genes like BCR::PDGFRA or PDGFRA mutations is critical because they often predict responsiveness to targeted therapies, offering patients more effective and less toxic treatment options compared to conventional chemotherapy. However, co-existence of BCR::PDGFRA and PDGFRA variants in one patient has not been reported and the sensitivity to TKIs is unknown.

Case presentation

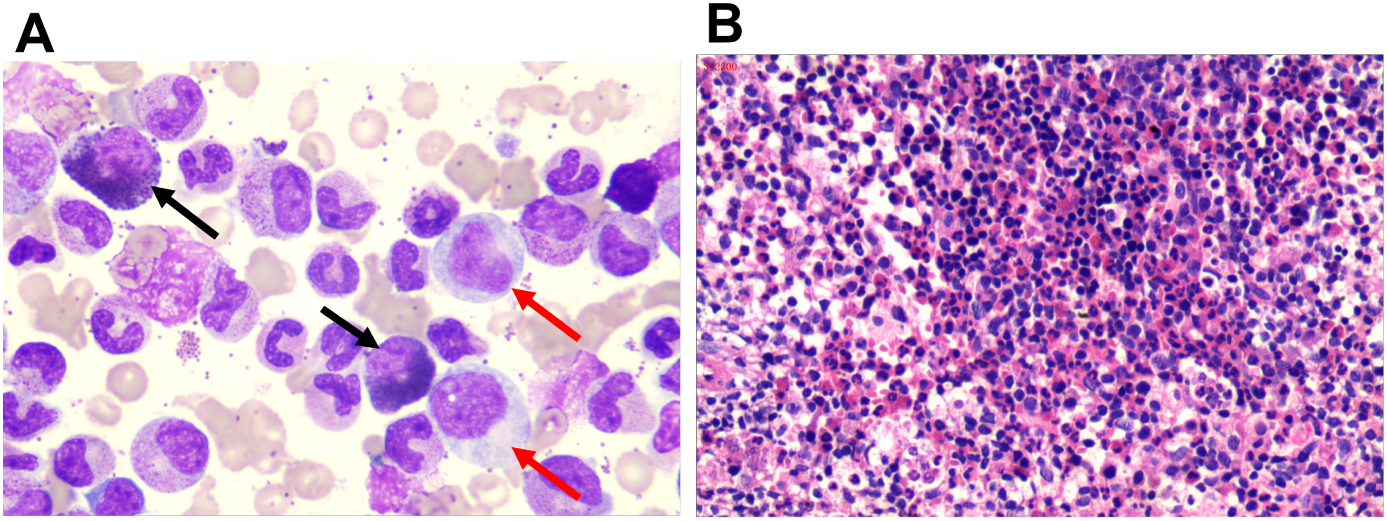

A 59-year-old man visited the hospital on June 06, 2023, after complaining of abdominal distension and fatigue for one month. The physical examination revealed abdominal bloating and an enlarged spleen. There was no significant swelling of the superficial lymph nodes or liver. Blood tests revealed significant leukocytosis, with an elevated white blood cell (WBC) count of 152.61×109/L. Neutrophils accounted for 84% of the WBC, eosinophils for 4%, and monocytes for 9%. Low hemoglobin levels (57 g/L) and reduced platelet count (63×109/L). The peripheral blood smear revealed an increase in neutrophil precursors, with myelocytes at 9% and metamyelocytes at 5%. Bone marrow aspiration revealed hypercellularity, with a granulocytic to erythrocytic ratio (G/E ratio) of 189:1 and granulocytic hyperplasia accounting for 94.5% of cells. Twenty percent of the neutrophilic myelocytes showed megaloblastoid alterations and occasional nuclear-cytoplasmic asynchrony. The eosinophil count was increased, accounting for 9% of all cells with normal shape (Figure 1A). An examination of the entire slide indicated erythroid, lymphoid, and megakaryocytic cells all had normal morphology, with no dysplastic characteristics. Bone marrow biopsy revealed a very vigorous growth of hematopoietic tissue with essentially no adipose tissue (Figure 1B). The hematopoietic tissue had a considerably higher G/E ratio, with numerous segmented neutrophils and a few immature myeloid cells. The abdominal ultrasonography revealed large splenomegaly with a longitudinal dimension of 17.51 cm, thickness of 6.23 cm, and 5.4 cm extension below the ribcage.

Figure 1

Bone marrow morphological characteristics of the patient. (A) Bone marrow smear showing granulocytic hyperplasia. Red arrows point to nuclear-cytoplasmic asynchrony, and the black arrow indicates eosinophilia (10×100). (B) Bone marrow biopsy stained with hematoxylin and eosin, revealing a hypercellular marrow with an increased granulocyte to erythrocyte ratio.

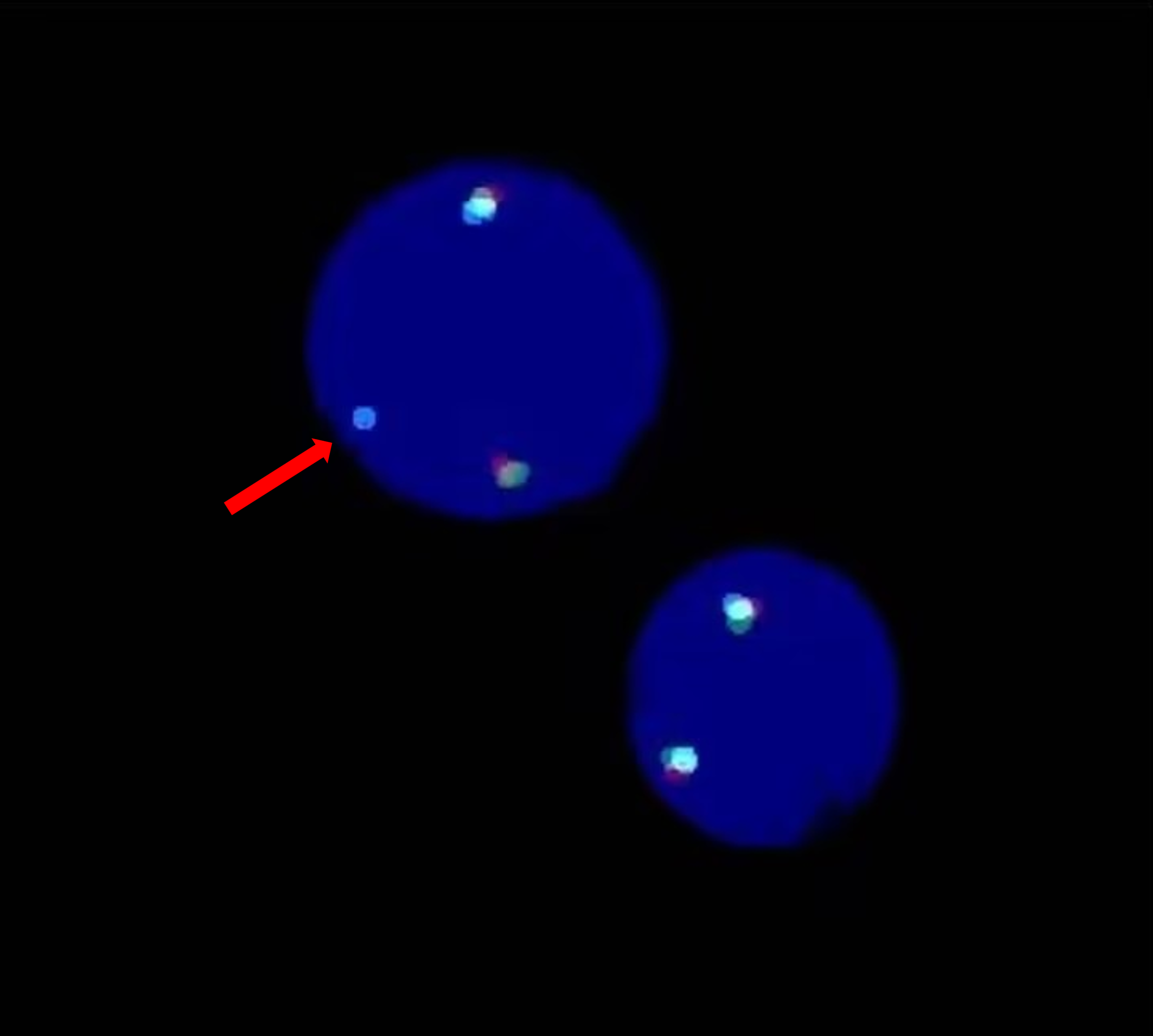

These findings strongly suggest a myeloid neoplasm. However, tests for the BCR::ABL (P210, P190, and P230) were negative. Additionally, mutations in JAK2V617F, exon 9 of the CALR gene, and MPL w515L/K were also negative. Morphologically, the findings support the diagnosis of atypical chronic myeloid leukemia (aCML) with BCR::ABL negative. Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) was performed to detect the FIP1L1::PDGFRA because of obvious hypereosinophils. The chromosomal regions 4q12 of the FIP1LI gene locus, CHIC2, and PDGFRA were labeled with green, red, and cyan respectively. According to the literature on FISH detection of CHIC2 deficiency, FIP1L1::PDGFRA fusion, and PDGFRA translocation (8), it is known that if there is FIP1L1::PDGFRA, it appears as a dual color fusion signal of green and cyan. Obviously, our FISH testing did not detect this signal.

However, 64% of cells exhibited a separate signal for PDGFRA (cyan), distinct from the green and red signals, indicating a rearrangement of PDGFRA (Figure 2).

Figure 2

FISH image showing a rearrangement of the PDGFRA gene. A separate signal for PDGFRA (cyan) was detected (red arrow).

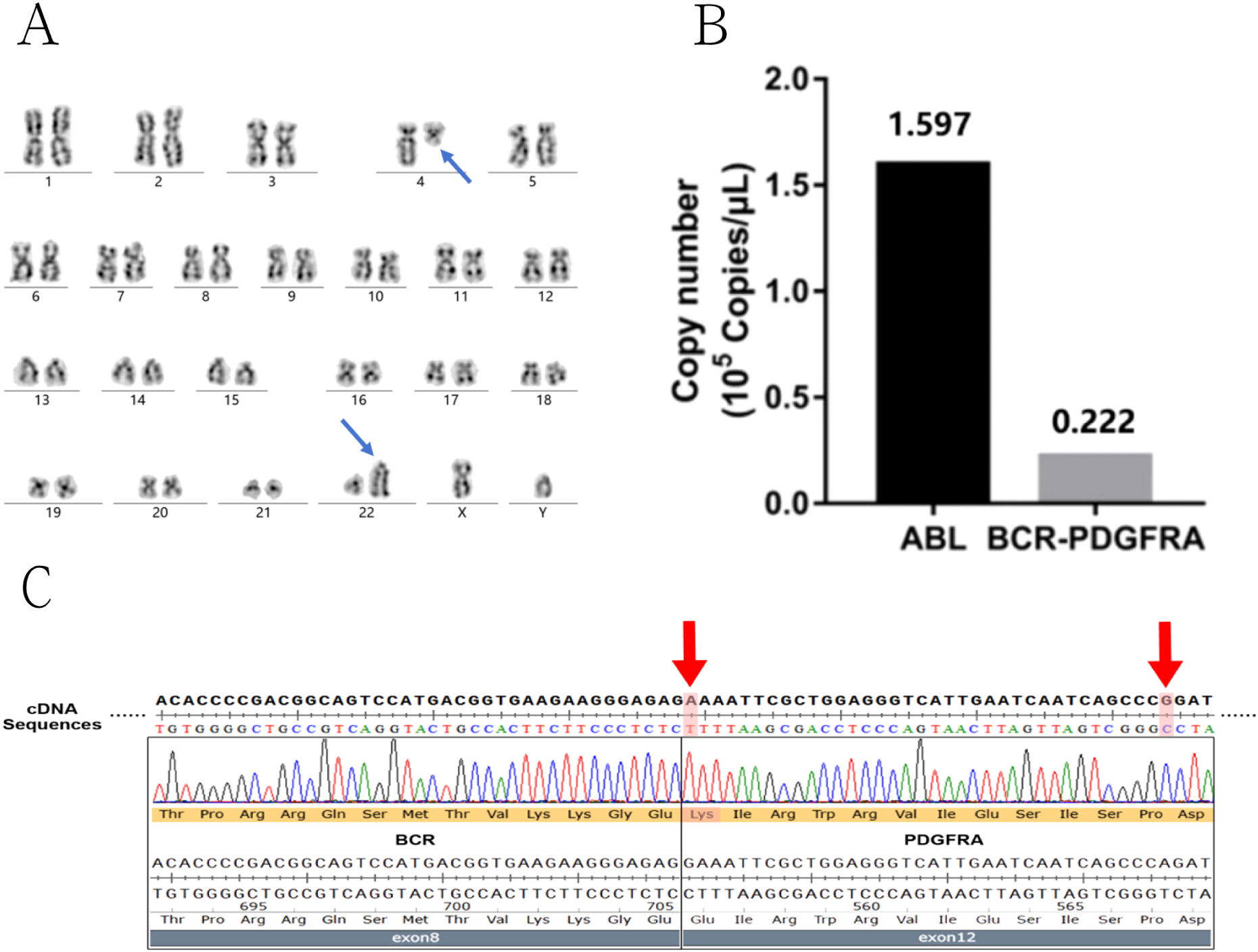

Chromosomal karyotype analysis revealed 46,XY,t(4;22)(q12;q11), implying that the companion gene for the rearrangement could be the BCR gene on chromosome 22q11 (Figure 3A). Real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (real-time RT-PCR) validated the fusion of the BCR::PDGFRA (Figure 3B). The fusion breakpoint was found at the junction of exons 8/9 of the BCR and exon 12 of the PDGFRA, according to genetic sequencing. Furthermore, two mutations were found on the cDNA of the BCR::PDGFRA, within the PDGFRA gene (reference transcript: NM_006206.6) on exon 12: (1) a missense mutation, c.1666G>A, p.Glu556Lys, and (2) a synonymous mutation, c.1701A>G, p.Pro567= (Figure 3C). The c.1666G>A is novel and has not been descripted in the gnomAD data (https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/). Through multi-dimensional analysis using SIFT, PolyPhen-2, CADD, and ClinPred scores, it was discovered that missense mutation c.1666G>A has pathogenicity. This indicates that the presence of c.1666G>A mutation probably further aggravates the occurrence and development of the disease. As for c.1701A>G mutation, it is described as benign in the gnomAD data. At the same time, using the splicing prediction tool SpliceAI, it was found that synonymous mutation c.1701A>G does not disrupt canonical or cryptic splice sites and is non-pathogenic. The c.1701A>G mutation has no clinical significance. Hence, the patient was diagnosed with myeloid neoplasms including the BCR::PDGFRA and coexisting PDGFRA mutations.

Figure 3

Genetic detection results of BCR::PDGFRA fusion and related mutations in the patient. (A) Karyotype analysis displaying t(4;22) translocation (blue arrow). (B) Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of BCR::PDGFRA gene showed positive fusion copies of 13.91%. (C) Sequencing analysis the fusion breakpoint was located at the junction of exon 8/9 of the BCR and exon 12 of the PDGFRA. The two mutations on the exon12 of PDGFRA were also detected (red arrow).

The BCR::PDGFRA induces gain-of-function modifications in PDGFRA, which are sensitive to TKIs like imatinib and facilitating the reduction of leukemic cell proliferation and improving patient outcomes (4). Based on previous reports PDGFRA rearrangement is relatively sensitive to imatinib. Therefore, the patient was initially treated with hydroxyurea to reduce WBC. On June 20, 2023, he initiated imatinib (100 mg/day) as an oral tyrosine kinase inhibitor, following a reduction in WBC count to 50×109/L. Three months after treatment, WBC numbers normalized, anemia improved to 122 g/L, and platelet count recovered to 102×109/L, resulting in hematological remission. After six months of treatment, the spleen size was significantly reduced. The BCR::PDGFRA was no longer detectable by the quantitative RT-PCR test, indicating a complete molecular response (CMR, defined as the absence of detectable disease-specific molecular markers). The patient’s condition has stabilized as of Dec 2025, and he is being monitored further.

Discussion

Importantly, it is understood that the most common rearrangement involving the PDGFRA gene is the FIP1L1::PDGFRA (9).Several fusion partners of PDGFRA in MPNs associated with eosinophilia, including BCR, ETV6, KIF5B, CDK5RAP2, STRN, TNKS2, and FOXP1, have been documented in the form of case reports/series (5, 10–15). The Philadelphia chromosome was not found in our report. Alternatively, we discovered that the BCR::PDGFRA was positive. PDGFRA gene on the chromosome 4q12 region encodes a tyrosine kinase receptor (16). According to the literature, five other PDGFRA fusion partners and more than 20 PDGFRB fusion partners have been reported in association with eosinophilia-associated myeloproliferative neoplasms. Although these abnormalities are very uncommon, they are associated with excellent responses to imatinib (17–19). Furthermore, our case meets the diagnostic criteria of MLN-TK as it carries the BCR::PDGFRA and presents with eosinophilia (6). Therefore, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, imatinib, is the first line therapeutic agent for the treatment of this category of diseases. In this example, Imatinib 100mg once daily was administered as a first-line treatment when white blood cells decreased below 50 ×109/L by utilizing hydroxyurea. Imatinib particularly inhibits the tyrosine kinase activity of the fusion protein, leading to a reduction in leukemic cell growth. The dose and length of imatinib or other TKIs therapy are dictated by the patient’s reaction and tolerance to the medicine. Regular follow-up with complete blood counts, bone marrow exams, and molecular testing is required to assess treatment response and detect any evidence of disease progression or transformation to acute leukemia. Treatment is highly customized and is determined by a lot of characters, including the patient’s age, overall health, illness features, and therapy response. To get the best potential outcome, myeloid neoplasms with BCR::PDGFRA should be managed by a team of hematology and oncology specialists.

Table 1 shows that only 12 cases of BCR::PDGFRA (including our present case) have been recorded worldwide up to now. The review included cases of myeloid neoplasm (n=1), CML (n=1), atypical CML (n=2), CML-like myeloproliferative disorder (n=1), chronic eosinophilic leukemia (CEL, n=2), therapy-related AML (n=1), mixed phenotypic acute leukemia (n=1), T-lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma (T-ALL, n=1), Pre-B cell ALL (n=1), and myeloproliferative. These studies demonstrate the diversity of hematopoietic malignancies resulting from BCR::PDGFRA, as well as the critical necessity for precise diagnostic tools to guide proper treatment. All patients (6/6, including our present case) who received imatinib treatment survived, and the others treated with chemotherapy or stem cell transplantation had a worse survival outcome. The findings further demonstrate the efficacy of targeted therapy. As for now, these cases have been classified into myeloid/lymphoid neoplasms with PDGFRA rearrangement.

Table 1

| Case | Age/sex | Clinical assessment | CBC | Peripheral blood smear | Bone marrow examination | Diagnosis | Treatment | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1(the present case) | 59/M | Bilateral lower limb edema; splenomegaly | Increased platelet count, neutrophil number, leukocyte, and erythrocyte. | Immature myeloid cells | hypercellular | Myeloid neoplasm | Imatinib | Survival |

| 2 (21) | 32/M | Splenomegaly | Leukocytosis | Immature granulocytes, basophilia, and eosinophilia | hypercellular | CML | Imatinib | Survival |

| 3 (5) | 37/M | Splenomegaly | Leukocytosis | Increase of eosinophils and also of normal and atypical megakaryocytes. | Myeloid hyperplasia with pronounced promyelocytes and some blasts | Atypical CML | Matched alloHSCT | Survival |

| 4 (11) | 57/M | Splenomegaly Lymphadenopathy | Leukocytosis | Anemia, leukocytosis with increased granulocytes and precursors | Myeloid hyperplasia and mild eosinophilia | Atypical CML | Imatinib | Survival |

| 5 (5) | 3/M | Enlarged tonsils; lymphadenopathy liver and spleen enlargement | Leukocytosis | NA | myeloid hyperplasia | CML-like myeloproliferative disorder with extramedullary T-lymphoid blast crisis | Auto-HSCT PR Allo-HSCT (MSD) | Dead |

| 6 (22) | 37/M | Abdominal discomfort and palpable spleen | Leukocytosis | NA | NA | Myeloproliferative neoplasm | Imatinib | Survival |

| 7 (10) | 47/M | Diffuse ecchymosis Multiple lymphadenopathies Hepatosplenomegaly | Leukocytosis | NA | Increased cellularity with 73% blast cells | Pre-B cell ALL | Imatinib | Survival |

| 8 (12) | 37/M | NA | NA | NA | NA | CEL | NA | NA |

| 9 (12) | 41/M | NA | NA | NA | NA | CEL | NA | NA |

| 10 (13) | 45/W | Cervical lymphadenopathy | Leukocytosis | A predominance of blasts, medium to large with oval or irregular nuclei, condensed chromatin, negligible nucleoli, and minimal, ungranulated cytoplasm without Auer rods. | Predominantly composed of blasts | Mixed phenotypic acute leukemia | Imatinib mesylate, cytarabine, and idarubicin | Survival |

| 11 (14) | 56/M | Splenomegaly and lymphadenopathy | Leukocytosis | NA | Immature lymphoid cells | T-ALL | Induction CR within 3mo after the diagnosis; intensive induction and consolidation Regimens, treatment was followed by maintenance therapy for a total of 2 year | Survival |

| 12 (23) | 77/M | Lymphadenopathy | Leukocytosis | Increased white cell count with rapidly elevated eosinophilia and basophilia | Multilineage dysplasia and focal eosinophilia. | Therapy related AML | Intensive chemotherapy received for B-ALL and complex karyotype | Dead |

Clinical presentations and treatment outcomes of cases with BCR::PDGFRA.

Genetic testing is critical for identifying specific gene mutations associated with myeloid neoplasms, such as JAK2, CALR, and MPL (20). In this case, the identification of two mutations in exon 12 of the PDGFRA gene—the missense mutation c.1666G>A, which results in the amino acid substitution p.Glu556Lys, and the synonymous mutation c.1701A>G, which does not change the amino acid p.Pro567—adds another layer of complexity to the patient’s genetic profile and potential pathogenesis. To further verify the significance of genetic mutations, the SIFT, PolyPhen-2, CADD, ClinPred scores and Splice AI prediction technology provided sufficient evidence. The c.1666G>A missense mutation is pathogenic. It remains unclear whether this mutation is a gain-of-function mutation or a loss-of-function mutation. There are no relevant studies at present, and future research is required to elucidate the correlation between this mutation and the manifestation of the disease. Furthermore, multi-dimensional technical detection proves that synonymous c.1701A>G mutations do not affect the function of the gene.

Anyway, through targeted therapy (imatinib), the patient has been well controlled as well as other MLN-TK with PDGFRA rearrangement (Table 1). Our case study has confirmed that even in patients with PDGFRA mutations, imatinib can achieve CMR for those with BCR::PDGFRA. This avoids unnecessary chemotherapy for these patients and ensures that they receive the most appropriate targeted therapy.

Furthermore, this brief communication adds to the literature on this rare entity, highlighting the importance of targeted therapy in Ph negative myeloproliferative neoplasms.

Key takeaways

The BCR::PDGFRA has only been reported in 11 cases in the literature. Our case discovery revealed that the patient not only had BCR::PDGFRA but also PDGFRA mutations. Moreover, the PDGFRA c.1666G>A mutation is novel and its coexistence with PDGFRA rearrangement is the first report up to now. Although the effect of c.1666G>A mutation in the BCR::PDGFRA is unknown, the targeted therapy using imatinib can enable the patient to achieve CMR. This indicates that timely targeted treatment can have a positive effect on such patients.

Statements

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/supplementary material.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Medical Ethics Committee of the General Hospital of Southern Theater Command. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article. Written informed consent was obtained from the participant/patient(s) for the publication of this case report.

Author contributions

ZX: Conceptualization, Data curation, Validation, Writing – original draft. CL: Formal Analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft. PZ: Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. NH: Formal Analysis, Resources, Writing – review & editing. XH: Investigation, Software, Writing – review & editing. JZ: Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing. YF: Software, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. MG: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. LO: Formal Analysis, Resources, Writing – review & editing. YG: Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. YL: Data curation, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation grant number 2022A1515220044; Guangzhou Science and Technology Project number 2025A03J3273.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

ThapaBFazalSParsiMRogersHJ. Myeloproliferative neoplasms. In: Statpearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing (2025). Available online at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK531464/.

2

SuryanarayanKHungerSPKohlerSCarrollAJCristWLinkMPet al. Consistent involvement of the BCR gene by 9;22 breakpoints in pediatric acute leukemias. Blood. (1991) 77:324–30. doi: 10.1182/blood.V77.2.324.324

3

RoumiantsevSKrauseDSNeumannCADimitriCAAsieduFCrossNCet al. Distinct stem cell myeloproliferative/T lymphoma syndromes induced by ZNF198-FGFR1 and BCR-FGFR1 fusion genes from 8p11 translocations. Cancer Cell. (2004) 5:287–98. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(04)00053-4

4

PeirisMNLiFDonoghueDJ. BCR: A promiscuous fusion partner in hematopoietic disorders. Oncotarget. (2019) 10:2738–2754. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.26837

5

BaxterEJHochhausABoluferPReiterAFernandezJMSenentLet al. The t(4;22)(q12;q11) in atypical chronic myeloid leukaemia fuses BCR to PDGFRA. Hum Mol Genet. (2002) 11:1391–7. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.12.1391

6

ReiterAMetzgerothGCrossNCP. How I diagnose and treat myeloid/lymphoid neoplasms with tyrosine kinase gene fusions. Blood. (2025) 145:1758–68. doi: 10.1182/blood.2023022417

7

KaurPKhanWA. Myeloid/lymphoid neoplasms with eosinophilia and platelet derived growth factor receptor alpha (PDGFRA) rearrangement. In: LiW, editor. Leukemia. Brisbane (AU): Exon Publications (2022). Available online at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK586201/.

8

FinkSRBelongieKJPaternosterSFSmoleySAPardananiADTefferiAet al. Validation of a new three-color fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) method to detect CHIC2 deletion, FIP1L1/PDGFRA fusion and PDGFRA translocations. Leuk Res. (2009) 33:843–6. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2008.11.016

9

CoolsJDeAngeloDJGotlibJStoverEHLegareRDCortesJet al. A tyrosine kinase created by fusion of the PDGFRA and FIP1L1 genes as a therapeutic target of imatinib in idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome. N Engl J Med. (2003) 348:1201–14. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa025217

10

ReiterAGotlibJ. Myeloid neoplasms with eosinophilia. Blood. (2017) 129:704–714. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-10-695973

11

TrempatPVillalvaCLaurentGArmstrongFDelsolGDastugueNet al. Chronic myeloproliferative disorders with rearrangement of the platelet-derived growth factor alpha receptor: A new clinical target for STI571/glivec. Oncogene. (2003) 22:5702–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206543

12

SafleyAMSebastianSCollinsTSTiradoCAStenzelTTGongJZet al. Molecular and cytogenetic characterization of a novel translocation t(4;22) involving the breakpoint cluster region and platelet-derived growth factor receptor-alpha genes in a patient with atypical chronic myeloid leukemia. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. (2004) 40:44–50. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20014

13

ErbenPGosencaDMüllerMCReinhardJScoreJDel ValleFet al. Screening for diverse PDGFRA or PDGFRB fusion genes is facilitated by generic quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction analysis. Haematologica. (2010) 95:738–44. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.016345

14

WangHYThorsonJABroomeHERashidiHHCurtinPTDell’AquilaML. t(4;22)(q12;q11.2) involving presumptive platelet-derived growth factor receptor a and break cluster region in a patient with mixed phenotype acute leukemia. Hum Pathol. (2011) 42:2029–36. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2010.07.028

15

YigitNWuWWSubramaniyamSMathewSGeyerJT. BCR-PDGFRA fusion in a T lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma. Cancer Genet. (2015) 208:404–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergen.2015.04.007

16

CurtisCEGrandFHMustoPClarkAMurphyJPerlaGet al. Two novel imatinib-responsive PDGFRA fusion genes in chronic eosinophilic leukaemia. Br J Haematol. (2007) 138:77–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06628.x

17

JovanovicJVScoreJWaghornKCilloniDGottardiEMetzgerothGet al. Low-dose imatinib mesylate leads to rapid induction of major molecular responses and achievement of complete molecular remission in FIP1L1-PDGFRA-positive chronic eosinophilic leukemia. Blood (2007) 109:4635–40. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-10-050054

18

DavidMCrossNCBurgstallerSChaseACurtisCDangRet al. Durable responses to imatinib in patients with PDGFRB fusion gene-positive and BCR-ABL-negative chronic myeloproliferative disorders. Blood. (2007) 109:61–4. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-024828

19

ApperleyJFGardembasMMeloJVRussell-JonesRBainBJBaxterEJet al. Response to imatinib mesylate in patients with chronic myeloproliferative diseases with rearrangements of the platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta. N Engl J Med. (2002) 347:481–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020150

20

EaswarASiddonAJ. Genetic landscape of myeloproliferative neoplasms with an emphasis on molecular diagnostic laboratory testing. Life (Basel) (2021) 11:1158. doi: 10.3390/life11111158

21

GaoLXuYWengLCTianZG. A rare cause of persistent leukocytosis with massive splenomegaly: Myeloid neoplasm with BCR-PDGFRA rearrangement-case report and literature review. Med (Baltimore). (2022) 101:e29179. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000029179

22

SinghMKSasikumaran Nair RemaniABhaveSJMishraDKAroraNPariharM. Detection of BCR/PDGRFα fusion using dual colour dual fusion BCR/ABL1 probe: an illustrative report. Indian J Hematol Blood Transfus. (2019) 35:570–574.

23

ZhouJPapenhausenPShaoH. Therapy-related acute myeloid leukemia with eosinophilia, basophilia, t(4;14)(q12;q24) and PDGFRA rearrangement: A case report and review of the literature. Int J Clin Exp Path. (2015) 8:5812–20.

Summary

Keywords

BCR::PDGFRA fusion, imatinib, myeloproliferative neoplasm, PDGFRA variants, tyrosine kinase inhibitors

Citation

Xiao Z, Lu C, Zhang P, Han N, He X, Zhang J, Feng Y, Guan M, Ouyang L, Gao Y and Li Y (2026) Case Report: Co-existence of BCR::PDGFRA gene fusion and PDGFRA variants in myeloid neoplasm with persistent leukocytosis, large splenomegaly, and eosinophilia. Front. Oncol. 16:1671293. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2026.1671293

Received

22 July 2025

Revised

26 January 2026

Accepted

29 January 2026

Published

17 February 2026

Volume

16 - 2026

Edited by

Raffaele Palmieri, University of Rome Tor Vergata, Italy

Reviewed by

Jia Yin, First Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University, China

Tommaso Caravita Di Toritto, UOSD Ematologia ASL Roma 1, Italy

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Xiao, Lu, Zhang, Han, He, Zhang, Feng, Guan, Ouyang, Gao and Li.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yonghua Li, lyhood@126.com

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.