- 1Nottingham Children’s Hospital, Nottingham, UK

- 2University of Nottingham Division of Child Health, Nottingham, UK

The prevention and/or rescue of babies at risk of bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) has focused upon the use of maternal antenatal steroids (1), surfactant (2), diuretics (3), and postnatal use of steroids along with various ventilator support strategies.

With regard to the evidence informing the use of steroids, there is no lack of data. Systemic corticosteroid administration (predominantly dexamethasone) through the immediate postnatal (4), moderate early (5) and late (6) periods, result in improved pulmonary outcomes (4–6) at a cost of short-term adverse effects (4). The use of corticosteroid treatment to treat or prevent development of established BPD remains controversial, however, largely due to concerns of neurodevelopmental sequelae. These are largely driven by one study (7), but as a whole, the inclusion of very varied steroid administration strategies in the same analyses make interpretation difficult.

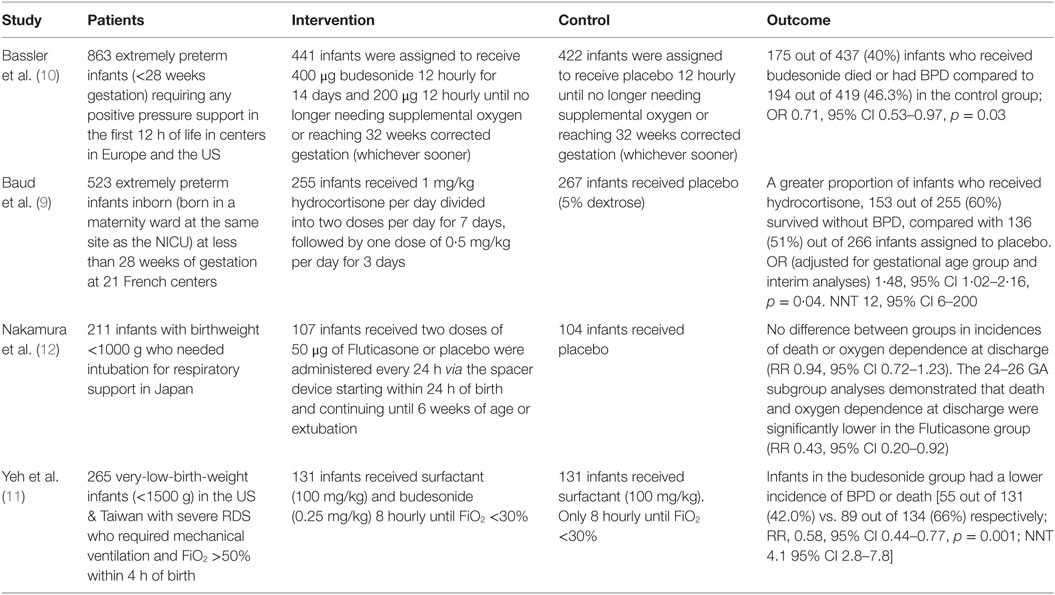

Recently, a series of multicentre, randomized, adequately powered, controlled trials (summarized in Table 1) have examined the use of alternative corticosteroids [hydrocortisone or betamethasone (8)] at lower systemic doses (9) or lung administration either through nebulization (10) or direct instillation (11) to limit systemic exposure.

The PREMILOC study (9) of low-dose hydrocortisone (1 mg/kg for 7 days with a 3-day wean; 8.5 mg/kg cumulative dose) recruited 523 extremely premature infants within the first day of life. The primary outcome was survival without BPD at 36 weeks of post menstrual age. The trial was stopped early due to “financial and technical support limitations,” and the planned analysis was adjusted as a result. 153 (60%) out of 255 infants assigned to receive hydrocortisone and 136 (51%) out of 266 infants assigned to placebo, survived without BPD. The effect size, adjusted for gestation, and the effect of repeated analyses in the statistical method was statistically significant – OR 1·48 (95% CI 1·02–2·16; p = 0·04). The number needed to treat (NNT) to achieve one BPD-free survival was 12 (95% CI 6–200). There was a significantly increased risk of late onset sepsis in those born at 24–25 weeks gestation given hydrocortisone (33/83; 40%) compared with placebo (21/90; 23%). Unfortunately, long-term neurodevelopmental outcome is not yet reported; however, MRI findings as a surrogate were available in 80% of the survivors with 30% of infants in each group demonstrating detectable lesions at term-corrected gestations.

The NEUROSIS trial (10) of inhaled budesonide (400 μg twice daily via a spacer for 2 weeks, then once daily until supplemental oxygen was not required or infant reached 32 weeks PMA) or placebo recruited 863 infants who needed respiratory pressure support in 40 centers in 9 European countries. Primary outcome was identical to the PREMILOC study (except rate of death or BPD at 36 weeks PMA). In a per-protocol analysis of 437 infants randomized to receive budesonide, 175 (40%) died or developed BPD compared with 194 out of 419 (46.3%) infants in the placebo group (effect size OR 0.71; 95% CI 0.53–0.97; p = 0.03). Those receiving budesonide appeared to come out of oxygen earlier and fewer babies required re-intubation. Unfortunately, neurodevelopmental outcomes are as yet unreported. In contrast, these were reported in a multicentre trial from Japan, where infants were randomized to receive inhaled fluticasone (n = 107) or placebo (n = 104). No significant differences were detected between the groups with respect to either the frequency of death, oxygen dependence at discharge, or neurodevelopmental impairment at 18 months and 3 years PMA. In subgroup analyses, the frequencies of death and oxygen dependence at discharge were significantly decreased in the fluticasone group for infants born at 24–26 weeks and for infants with chorioamnionitis, regardless of the gestational age at birth (12).

In the study by Yeh et al. (11), 265 very-low-birth-weight (<1500 g) infants with severe respiratory distress syndrome requiring invasive ventilation were randomised to receive either intratracheal surfactant alone or in a combination mixed with budesonide (0.25 mg or 1 ml/kg). Doses were repeated every 8 h until infants, required less than 30% oxygen, were extubated or had received a maximum of six doses. The primary outcome measure was again identical to the two other studies. Infants in the combined surfactant-budesonide group had a lower incidence of BPD or death (55 out of 131, 42%) compared with those in the surfactant-only group (89 out of 134, 66%) (RR 0.58; 95% CI 0.44–0.77; p < 0.001). The NNT was 4.1 (95% CI 2.8–7.8). With 85% of the cohort under follow-up at 30 months of age, the proportions of infants described as having “neurodevelopmental impairment” were 26 out of 85 (30.6%) in the intervention group compared with 34 out of 87 (39.1%) in the control group, with follow-up ongoing.

The four recent studies report the use of local/lower dose corticosteroid to prevent BPD/death and find a significant beneficial effect, at least in selected groups of babies. This is unsurprising as efficacy has really not been in doubt, although, it is encouraging that a reduced dose exerts a similar effect. It is disappointing that, as yet, the factor limiting adoption, neurodevelopmental impairment, has not been reported in three of these studies, and these studies are unlikely to change practice until it is.

While these data add to evidence for preventing BPD, there remains a large void in the evidence base informing the treatment of those with established severe BPD. Indeed, the current studies appear to show no promise for this small group of infants as the proportion of infants with very severe BPD was no different between treatment and control groups in the PREMILOC study (9). Management for these infants is likely to vary to an even greater degree than the approach taken across units or countries (13) with the use of steroids for all premature infants (14). One approach extrapolates the strategy used for childhood interstitial lung disease (15) but restricts it to those considered to have life-threateningly very severe BPD with an objective measure of severity.

While the studies that have been completed need follow-up in order to report neurodevelopmental outcome, the pendulum does appear to have come back toward the center in terms of steroid use in preventing BPD. In the case of established, very severe BPD, it is not just a case of “more studies are needed,” one study would be a start.

Author Contributions

JB conceived the idea and provided the structure of the commentary. MH wrote the first draft. Both authors agreed the final draft.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1. Roberts D, Dalziel S. Antenatal corticosteroids for accelerating fetal lung maturation for women at risk of preterm birth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2006) (3):CD004454. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004454.pub2

2. Egberts J, Brand R, Walti H, Bevilacqua G, Bréart G, Gardini F. Mortality, severe respiratory distress syndrome, and chronic lung disease of the newborn are reduced more after prophylactic than after therapeutic administration of the surfactant Curosurf. Pediatrics (1997) 100(1):E4. doi:10.1542/peds.100.1.e4

3. Stewart A, Brion LP, Ambrosio-Perez I. Diuretics acting on the distal renal tubule for preterm infants with (or developing) chronic lung disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2011) (9):CD001817. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001817.pub2

4. Doyle LW, Ehrenkranz RA, Halliday HL. Early (< 8 days) postnatal corticosteroids for preventing chronic lung disease in preterm infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2014) (5):CD001146. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001146.pub4

5. Halliday HL, Ehrenkranz RA, Doyle LW. Moderately early (7-14 days) postnatal corticosteroids for preventing chronic lung disease in preterm infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2003) (1):CD001144. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001144

6. Doyle LW, Ehrenkranz RA, Halliday HL. Late (> 7 days) postnatal corticosteroids for chronic lung disease in preterm infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2014) (5):CD001145. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001145.pub3

7. Shinwell ES, Karplus M, Reich D, Weintraub Z, Blazer S, Bader D, et al. Early postnatal dexamethasone treatment and increased incidence of cerebral palsy. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed (2000) 83(3):F177–81. doi:10.1136/fn.83.3.F177

8. Smolkin T, Ulanovsky I, Jubran H, Blazer S, Makhoul IR, et al. Experience with oral betamethasone in extremely low birthweight infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed (2014) 99(6):F517–8. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2014-306619

9. Baud O, Maury L, Lebail F, Ramful D, El Moussawi F, Nicaise C, et al. Effect of early low-dose hydrocortisone on survival without bronchopulmonary dysplasia in extremely preterm infants (PREMILOC): a double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre, randomised trial. Lancet Lond Engl (2016) 387(10030):1827–36. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00202-6

10. Bassler D, Plavka R, Shinwell ES, Hallman M, Jarreau P-H, Carnielli V, et al. Early inhaled budesonide for the prevention of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. N Engl J Med (2015) 373(16):1497–506. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1501917

11. Yeh TF, Chen CM, Wu SY, Husan Z, Li TC, Hsieh WS, et al. Intratracheal administration of budesonide/surfactant to prevent bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med (2016) 193(1):86–95. doi:10.1164/rccm.201505-0861OC

12. Nakamura T, Yonemoto N, Nakayama M, Hirano S, Aotani H, Kusuda S, et al. Early inhaled steroid use in extremely low birthweight infants: a randomised controlled trial. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed (2016) 309943. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2015-309943

13. Ogawa R, Mori R, Sako M, Kageyama M, Tamura M, Namba F. Drug treatment for bronchopulmonary dysplasia in Japan: questionnaire survey: Drug treatment for BPD in Japan. Pediatr Int (2015) 57(1):189–92. doi:10.1111/ped.12584

14. Job S, Clarke P. Current UK practices in steroid treatment of chronic lung disease. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed (2015) 100(4):F371. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2014-308060

Keywords: bronchopulmonary dysplasia, corticosteroids, prematurity, oxygen, neurodevelopment

Citation: Hurley M and Bhatt JM (2016) Where Are We Now with the Role of Steroids in the Management of Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia in Extremely Premature Babies? Front. Pediatr. 4:85. doi: 10.3389/fped.2016.00085

Received: 11 July 2016; Accepted: 29 July 2016;

Published: 10 August 2016

Edited by:

Luis Garcia-Marcos, University of Murcia, SpainReviewed by:

Maroun Jean Mhanna, Case Western Reserve University, USACopyright: © 2016 Hurley and Bhatt. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jayesh Mahendra Bhatt, amF5ZXNoLmJoYXR0QG51aC5uaHMudWs=

Matthew Hurley

Matthew Hurley Jayesh Mahendra Bhatt

Jayesh Mahendra Bhatt