- Texas Christian University Harris College of Nursing and Health Sciences, Fort Worth, TX, USA

The American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) recently published a consensus statement on the recommended number of hours of sleep in infants and children. The AASM expert panel identified seven health categories in children influenced by sleep duration, a component of sleep quality. For optimal health and general function, children require a certain number of hours of sleep each night. Limited data exist to subjectively assess sleep in this population. Practitioners must evaluate overall sleep quality not simply sleep duration. The purpose of this article is to provide a mini-review of the self-report sleep measures used in children. The authors individually completed a review of the literature for this article via an independent review followed by collaborative discussion. The subjective measures included in this mini-review have been used in children, but not all measures have reported psychometrics. Several tools included in this mini-review measure subjective sleep in children but with limited reliabilities or only preliminary psychometrics. Accurate measurement of self-reported sleep in children is critical to identify sleep problems in this population and further detect associated health problems. Ongoing studies are warranted to establish reliable and valid measures of self-reported sleep in children to accurately detect health problems associated with poor sleep quality. This mini-review of the literature is an important first step to identify the most reliable subjective sleep measures in children.

Introduction

The American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) published a consensus statement on the recommended number of hours of sleep in infants and children (1). For optimal health, children require a certain number of hours of sleep each night. However, limited reported resources support clinicians on how to best measure sleep in children and, more importantly, how to improve sleep in this population. Although variability based on genetics, medical, behavioral, and environmental environments exists in the need for sleep in children, health providers need this information to discuss, educate, and promote better sleep practices in children.

Experts who studied and defined sleep and developed sleep promotion approaches are represented in a number of professional organizations, AASM, American Association of Sleep Technologists, and Sleep Research Society, making widespread dissemination of this information a challenge. Easy access to such information is needed to support evidence-based practice and to determine best self-report sleep measures for children and adolescents, especially in cases without a sleep disorder. This information is not well disseminated among the many clinicians who want to accurately measure sleep but cannot spend an inordinate amount of time accessing the most reliable sleep measures in children, but rather need them easily accessible. A gap in the literature exists to describe best measures of self-reported sleep for children and adolescents without sleep disorders. Practitioners must evaluate overall sleep quality not simply sleep duration as recommended by the AASM consensus statement.

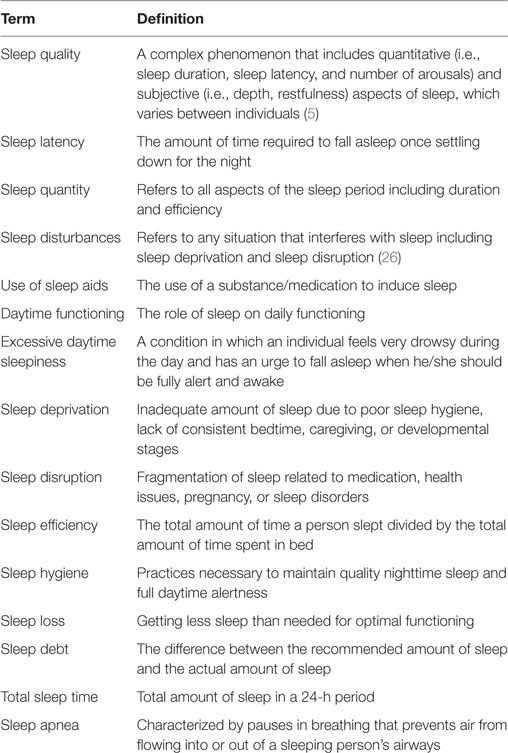

Understanding adult sleep characteristics provides a baseline to study clinical conditions that deviate from the expected norm (2). Children with limited number and quality of hours slept may exhibit many potential health problems if they do not receive adequate sleep. This mini-review describes self-report sleep measures in children, sleep components measured, and tool psychometrics when available. Although much information has been previously reported by Spruyt and Gozal (3), this review further examines the tools that measure the construct of sleep in this population. Clinicians who assess sleep in the pediatric populations want to know the tool used is accurately assessing sleep quality without assuming a sleep disorder. The authors provide a list of frequently used terms to define sleep components in Table 1.

Methods

The authors accessed several databases to complete the literature review: Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), PubMed, Embase, Academic Science Complete, Cochrane Library, and the Joanna Briggs Institute. No time period limits were placed and key terms included sleep, child*, self-report, and subjective, and measure. Inclusion criteria were (a) English language, (b) quantitative and qualitative design, (c) subjective measures of sleep using self-report only, and (d) child able to provide self-reported sleep regardless of age. Exclusion criteria included no parental, custodial, teacher, or other proxy report of sleep. Searches using keywords child* and self-report sleep yielded over 200 articles; when measure was added to the search 64 articles were identified. Following review of the abstracts, only eight met inclusion criteria. The authors identified two literature reviews of measures of self-reported sleep in children and used those reports’ citations to expand the search. Authors also reviewed STOP, THAT, and One Hundred Other Sleep Scales (4) in an effort to exhaust the literature. The reasons included tool unavailability in the English language, abstracts only available for review, and challenges to access certain tools.

Measures

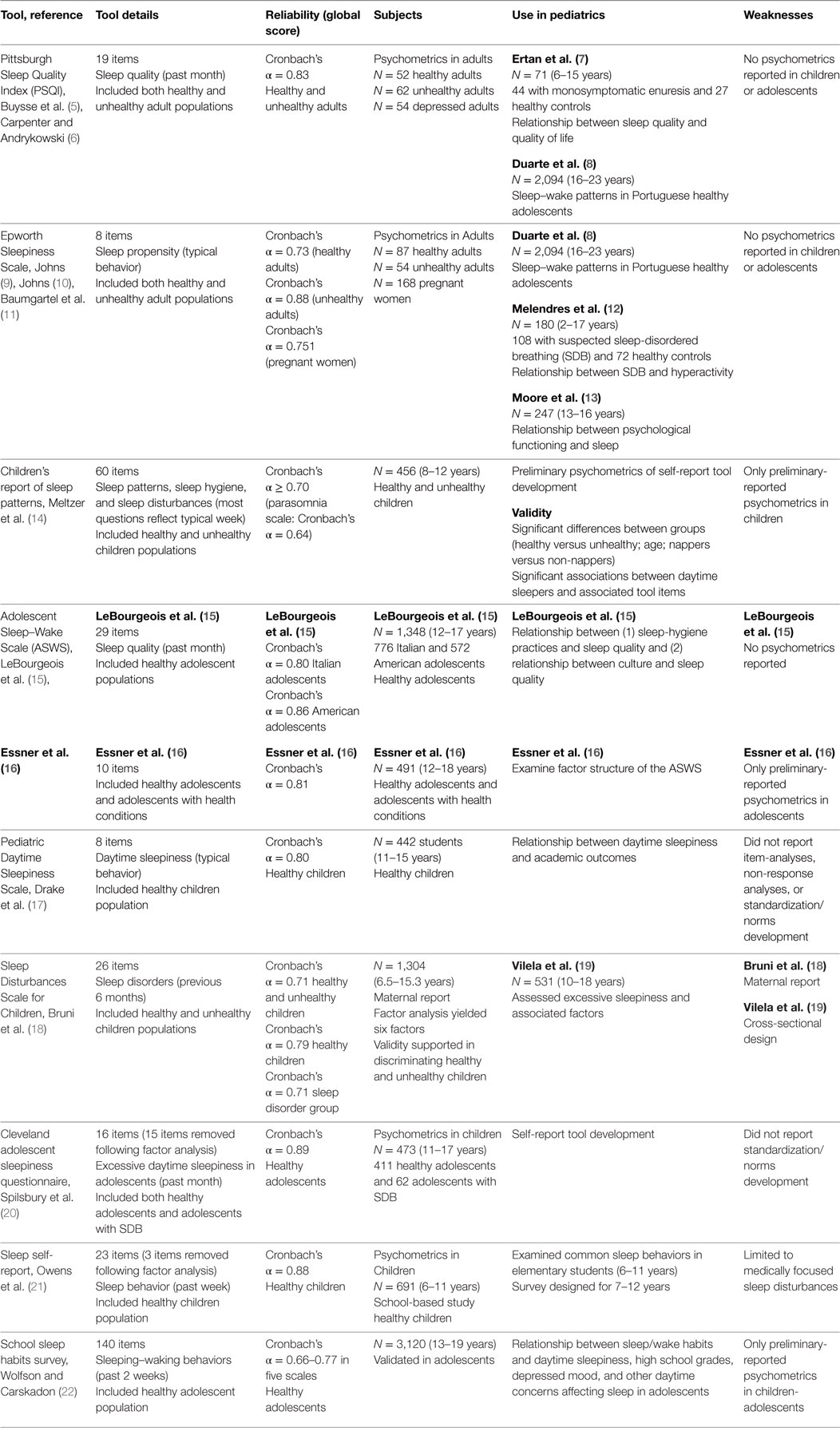

Subjective assessment of sleep is a critical component of sleep measurement in children because self-reported sleep in children is as valid as objectives measures of sleep; what children report as troublesome to them must be considered when making decisions about their health. Although the authors of the current mini-review agree with the Spruyt and Gozal (3) report on the lack of psychometrics, validation, and misuse of many pediatric sleep measures, the information derived from the self-reported measurement of sleep in children is clinically valuable. The summary of the self-report tools in this mini-review is found in Table 2.

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI)

The PSQI was developed to measure the complex multidimensional phenomenon of sleep quality and address the components of what constitutes sleep including: sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleep medications, and daytime dysfunction in the past month (5). The PSQI is composed of 19 self-rated questions and five questions rated by a bed partner or roommate. Only the self-rated items are used in scoring the scale. The dimension scores are summed to produce a global score (range 0–21). Cronbach’s alpha was 0.83 for the global score following examination in a group of healthy and unhealthy adults. Test–retest reliability (average interval of 28 days) assessed with a subset of 91 patients determined the internal consistency was 0.85 for the global score and 0.65–0.84 for the subscales (6).

The PSQI was used in adolescents and children to examine sleep disturbances and the association with health problems (7) and school performance (8). Ertan et al. (7) explored the relationship between sleep and quality of life in 44 children with monosymptomatic enuresis. Duarte et al. (8) conducted a correlational epidemiological, cross-sectional study of 2,094 students aged 16–23 years (M = 15.82 ± 1.25) in regards to their sleep patterns and academic performance. Neither study established the psychometrics for the PSQI limiting the usefulness of the PSQI in pediatrics.

Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS)

The ESS measures daytime sleepiness and consists of eight items (situations) where individuals assess how likely they would fall asleep (9). A sum of responses is calculated for a total score ranging from 0 to 24 with higher numbers representing greater sleepiness (9). The original intent was for subjects to use the recent past as a frame of reference in completing the scale and for clinicians and researchers to instruct subjects to focus on dozing and not tiredness or sleepiness.

Psychometrics were initially conducted by Johns (10) comparing adult students with sleep disorders and a normative sample of medical students. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.88 in adults with sleep disorders and 0.73 in medical students, respectively (10). Further psychometrics were performed and confirmatory analysis done in one half of a sample of pregnant women (N = 168) (11). The overall Cronbach’s alpha of the ESS was acceptable reliability of an established instrument (α = 0.751). The Cronbach’s alpha for the overall score without item seven (α = 0.708) was less than when it was included in the overall score (α = 0.751) (10).

The ESS has been used in children and adolescents to examine the relationship of sleep-disordered breathing and hyperactivity (12) and psychological functioning and sleep (13). However, no psychometrics for the ESS in children has been established. Melendres et al. (12) were the first to use a modified ESS in children. However, their study included both parent- and child-reported sleepiness. They did not report how many children provided self-reported daytime sleepiness and, again, did not perform psychometrics. Moore et al. (13) used the terms sleep duration, any variation in sleep duration, and sleepiness as a proxy for sleep disorders.

Children’s Report of Sleep Patterns (CRSPs)

The CRSP was developed and tested in 456 children aged 8–12 years to measure sleep patterns in children (14). The Cronbach’s α is 0.70–0.76 for the sleep disturbances scales (one of the three modules contained within the CRSP). The authors did not provide reliabilities for the other subscales; sleep pattern and sleep hygiene indices. The CRSP was validated through multimodal efforts using parental report and child report, and the objective measure of actigraphy.

Adolescent Sleep–Wake Scale (ASWS)

The ASWS has been used to examine sleep quality (15). The ASWS measures the quality of sleep based on specific nighttime behaviors including going to bed and falling asleep (latency), maintaining sleep, reinitiating sleep, and returning to wakefulness. The ASWS is a 29-item self-report measure that assesses sleep quality in 12- to 18-year-old adolescents in the past month (15). Reported Cronbach α was between 0.80 and 0.86 in this population.

The factor structure of the ASWS was examined in a recent study by Essner et al. (16) in a population of adolescents with and without health conditions. Following factor analysis, the total scale was reduced to 10 items. Falling asleep and reinitiating sleep were combined into one factor loading in the final analysis. Reported Cronbach α was 0.81 for the total sample.

Pediatric Daytime Sleepiness Scale (PDSS)

The PDSS was developed and tested in a population of 442 middle school students (11–15 years) to examine the relationship of daytime sleepiness and academic outcomes (17). Psychometrics of the PDSS included a total of eight items with acceptable factor loadings. Internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) for the total scale was 0.81 and 0.80 on the split-half sample (17).

The PDSS was designed to measure daytime sleepiness. The researchers indicated this measure assesses daily sleep patterns including total sleep time, weekday bed time, and weekday wake time (17). The recall period that the child was asked to respond to the items is unclear.

Sleep Disturbances Scale for Children (SDSC)

The SDSC is a 27-item scale tested in 1,304 children and adolescents ages ranging from 6.5 to 15.3 years in Rome to evaluate sleep disturbances in children (18). However, Bruni et al. (18) had mothers to complete the measures rather than self-report. The SDSC had good internal consistency between the control and sleep disorders groups; Cronbach’s alpha was 0.79 and 0.71, respectively, and Cronbach’s alpha on the total score was (r = 0.71) (18).

The SDSC was further evaluated in a population of 531 adolescents in both public and private schools to measure factors that influence excessive daytime sleepiness in this population (18). Vilela et al. (19) included items on sleep deficit on the weekends compared to the weekdays to determine a sleep deficit score. This study was a cross-sectional design and may require more longitudinal assessment (19).

Cleveland Adolescent Sleepiness Questionnaire (CASQ)

The CASQ was developed specifically to measure daytime sleepiness in adolescents. The CASQ was used in adolescents with sleep-ordered breathing and a healthy adolescent sample and was developed to measure sleepiness in adolescents 11–17 years of age (20). Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was first conducted on half of the healthy sample (N = 181) and revealed a final 4-factor solution explaining 55% of the variance; “sleep in school,” “alert in school,” “sleep in the evening,” and “sleep during transport.” Psychometrics indicated a Cronbach’s alpha 0.89. Whether this tool is useful in a healthy adolescent population to clinically assess sleep is not clear.

Sleep Self-Report (SSR)

The SSR is a 26-item measure developed and administered to 691 grade school children aged 7–12 years to measure sleep habits and prevalence of common medical and behavioral sleep disturbances in young children (21) and was designed to assess components similar to the parent version of this tool, the Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire. Components include bedtime behavior, sleep onset, sleep duration, behavior occurring during sleep, and night wakenings, parasomnias, and morning waking/daytime sleepiness. Factor analysis yielded 23 items. A total score resulted in an alpha coefficient of.88 (21).

The authors propose that this tool measures sleep habits and medical/behavioral disturbances. The tool is limited to medically focused sleep disturbances, such as pain and possibly night terrors, and is not comprehensive.

School Sleep Habits Survey

The goal of the study was to document the relationship of sleep/wake habits and daytime sleepiness, high school grades, depressed mood, and other daytime concerns affecting sleep in adolescents (22). The survey includes items on school performance (grades), daytime sleepiness, sleep/wake problems, and depressive mood. This tool has multiple items on trauma or potential traumatic injury that do not have adequate rationale for their inclusion in this tool. Further, the authors do not discuss these items within their narrative when reporting outcomes of sleep in adolescents (22).

The scoring of this tool may not be apparent to clinicians who want to use this survey in practice and is burdensome to the general clinician for use in clinical practice to make assumptions about sleep quality in normal adolescence. The items that were labeled were found on the Sleep for Science webpage (23).

Discussion

Measuring all components of sleep quality in children is important due to the potential health problems sequential to poor sleep quality. Subjective measures rely on having the appropriate developmental tool available to the population of interest. Measurement results may vary based on ability of children to provide an accurate self-report. Many tools lack reported psychometric evaluation and have limited reliability.

The self-report measures in this mini-review were chosen based on the authors’ access to the measures and that the tool was used to measure self-reported sleep in children and adolescents. Many of the reviewed subjective measures lacked consistent use of terminology in regards to sleep components or lack of rationale for chosen components or factors associated with poor sleep (13, 20). Descriptive literature often lacked ongoing large clinical trials to examine tool utility in measuring sleep quality in children over time (5, 9, 14–18, 20–22). When measuring sleep in children with potential limited recall and the potential for chronic poor sleep in children, longitudinal assessment of sleep in children is warranted.

The PSQI and ESS have been used widely in adults with acceptable reliabilities (5, 6, 9–11). Despite the lack of psychometrics of these tools in children and adolescents, the PSQI and ESS have been examined in children and adolescents with sleep disturbances and the association with health problems including academic performance (8), enuresis (7), hyperactivity (12), and psychological functioning (13).

The CRSP (14), The ASWS (16), The PDSS (17), SDSC (18), CASQs (20), and SSR (21) have been developed for children and adolescents and have preliminary psychometrics performed with acceptable reliabilities in the population they were tested.

The SDSC and the CASQ were tested in populations of children with and without sleep disorders and have not been further reported in the literature (18, 20). In addition, the SSR examined sleep habits in young children and the presence of sleep disturbances (21). While the SSR was examined in a normal population of elementary school children, it was designed to identify sleep disturbances. The CASQ was developed to measure daytime sleepiness in adolescents, a typical problem in this population and showed promise in being able to discern between daytime sleepiness and sleep disorders (20). The CASQ when used in another study by Vilela et al. (19) reported that adolescents with higher scores on the CASQ were associated with the presence of sleep disorders. The SDSC also measures sleep disturbances in children with known or presumed sleep disorders. In addition, the SSR was used to examine the relationship between sleep habits and common medical and behavioral sleep disturbances. The CASQ, SDSC, and the SSR have not been repeated in the literature and have only been used to identify children and adolescents with sleep disorders and not a normative sample. Therefore, these tools may not be applicable in assessing sleep quality in healthy children and adolescents in the clinical setting.

The ASWS has been used to measure sleep quality in adolescents (15, 16). The researchers reported the reliabilities of these measures, but the value in assessing sleep in healthy children has not been established over time. Further exploration of these measures in healthy adolescents is needed to address the various reasons why adolescents may have poor sleep quality.

The School Sleep Habits Survey was a lengthy survey used in adolescents to identify the many issues precluding this population from getting adequate sleep. The researchers did not provide rationales for item inclusion. The items, specifically on trauma or injury and their relationship to sleep in adolescents, are not clear.

The AASM consensus statement clearly recommends that health professionals take a proactive approach in addressing, educating and promoting healthy sleep practices in children (1). Children and adolescents have many reasons for poor sleep quality and sleep is critical to everyday functioning and overall health. Addressing sleep quality in all children is necessary. Poor sleep quality impacts academic performance attention, cognition, and mood in adolescents specifically (8, 24). Further, sleep problems in adolescent survivors of cancer have been found to correlate with poorer psychosocial outcomes including depressive symptoms in this population (25).

Sleep is important for overall functioning in healthy children and adolescents. These measures provide support for their use in clinical and research settings. Moore et al. (13) highlight the need to understand the relationship between sleep and psychological functioning, such as depression, in adolescents. Specific targeted questions to children able to provide self-report on their own sleep as they can with the assessment with pain is critical to meeting their entire health care needs.

Implications

Establishing the psychometrics of these tools is critical to have reliable measures of self-reported sleep in children and adolescents. Many of the sleep measures have not been used over time in the population in which they were initially tested limiting the ability to determine their clinical value and feasibility in clinical practice. Finally, clinicians need sleep measures they can easily administer during a busy clinical day. Ascertaining self-reported sleep in this population yields the most valuable data in the absence of objective sleep measures.

The concept of sleep and the components of sleep important to daily functioning and overall health in children remains unclear to the general clinician. Children reporting sleepiness during the daytime are not alert, able to function well enough to learn, engage in social relationships, engage in athletics, or drive.

One possible explanation for the lack of comprehensive and well-designed subjective measures of sleep is the lack of understanding of the concept of sleep. The authors of this review paper were not able to identify any literature addressing the concept of sleep. Before best measures of self-reported sleep in children can be developed, the concept of sleep requires further attention in healthy children.

Author Contributions

AE and LB contributed equally to the literature search, summation of the literature, and revisions of the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final version of this revised manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Funding

The authors have no funding sources to declare.

References

1. Paruthi S, Brooks LJ, D’Ambrosio C, Hall WA, Kotagal S, Lloyd RM, et al. Consensus statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine on the recommended amount of sleep for healthy children: methodology and discussion. J Clin Sleep Med (2016) 12(11):1549–61. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.6288

2. Carskadon MA, Dement WC. Normal human sleep: an overview. In: Kryger MH, Roth T, Dement WC, editors. Principles and Practice of Sleep Medicine. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders (2011). p. 16–26.

3. Spruyt K, Gozal D. Pediatric sleep questionnaires as diagnostic epidemiological tools: a review of currently available instruments. Sleep Med Rev (2011) 15(1):19–32. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2010.07.005

4. Shahid A, Wilkinson K, Marcu S, Shapiro CM, editors. STOP, THAT and One Hundred Other Sleep Scales. New York: Springer Science & Business Media (2012).

5. Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res (1989) 28:193–213. doi:10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4

6. Carpenter JS, Andrykowski MA. Psychometric evaluation of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index. J Psychosom Res (1998) 45:5–13. doi:10.1016/S0022-3999(97)00298-5

7. Ertan P, Yilmaz O, Calayan M, Sogut A, Aslan S, Yuksel H. Relationship of sleep quality and quality of life in children with monosymptomatic enuresis. Child Care Health Dev (2009) 35:469–75. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2214.2009.00940.x

8. Duarte J, Nelas P, Chaves C, Ferreira M, Coutinho E, Cunha M. Sleep-wake patterns and their influence on school performance in Portuguese adolescents. Aten Primaria (2014) 46:160–4. doi:10.1016/S0212-6567(14)70085-X

9. Johns M. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth Daytime Sleepiness Scale. Sleep (1991) 14:540–5.

10. Johns MW. Reliability and factor analysis on the Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Sleep (1992) 15(4):376–81.

11. Baumgartel K, Terhorst L, Conley Y, Roberts JM. Psychometric evaluation of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale in an obstetric population. Sleep (2013) 14:116–21. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2012.10.007

12. Melendres CS, Lutz JM, Rubin ED, Marcus CL. Daytime sleepiness and hyperactivity in children with suspected sleep-disordered breathing. Pediatrics (2004) 114:768–75. doi:10.1542/peds.2004-0730

13. Moore M, Kirchner L, Drotar D, Johnson N, Rosen C, Ancoli-Israel S, et al. Relationships among sleepiness, sleep time, and psychological functioning in adolescents. J Pediatr Psychol (2009) 34:117–83. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jsp039

14. Meltzer LJ, Avis KT, Biggs S, Reynolds AC, Crabtree VM, Bevans KB. The Children’s Report of Sleep Patterns (CRSP): a self-report measure of sleep for school-aged children. J Clin Sleep Med (2013) 9(3):235–45. doi:10.5664/jcsm.2486

15. LeBourgeois MK, Giannotti F, Cortesi F, Wolfson AR, Harsh J. The relationship between reported sleep quality and sleep hygiene in Italian and American adolescents. Pediatrics (2005) 115:257–65. doi:10.1542/peds.2004-0815H

16. Essner B, Noel M, Myrvik M, Palermo T. Examination of the factor structure of the Adolescent Sleep–Wake Scale (ASWS). Behav Sleep Med (2015) 13(4):296–307. doi:10.1080/15402002.2014.896253

17. Drake C, Nickel C, Burduvali E, Roth T, Jefferson C, Pietro B. The Pediatric Daytime Sleepiness Scale (PDSS): sleep habits and school outcomes in middle-school children. Sleep (2003) 26(4):455–8.

18. Bruni O, Ottaviano S, Guidetti V, Romoli M, Innocenzi M, Cortesi M, et al. The Sleep Disturbance Scale for Children (SDSC): construction and validation of an instrument to evaluate sleep disturbances in childhood and adolescence. J Sleep Res (1996) 5:251–61. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2869.1996.00251.x

19. Vilela TS, Bittencourt LR, Tufik S, Moreira GA. Factors influencing excessive daytime sleepiness in adolescents. J Pediatr (Rio J) (2016) 92(2):149–55. doi:10.1016/j.jped.2015.05.006

20. Spilsbury JC, Drotar D, Rosen CL, Redline S. The Cleveland Adolescent Sleepiness Questionnaire: a new measure to assess excessive daytime sleepiness in adolescents. J Clin Sleep Med (2007) 3(6):603–12.

21. Owens JA, Spirito A, McGuinn M, Nobile C. Sleep habits and sleep disturbances in elementary school-aged children. J Dev Behav Pediatr (2000) 21(1):27–36. doi:10.1097/00004703-200002000-00005

22. Wolfson AR, Carskadon MA. Sleep schedules and daytime functioning in adolescents. Child Dev (1998) 69(4):875–87. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.1998.tb06149.x

23. Sleep for Science. Research Instruments [Internet]. East Providence, RI: E. P. Bradley Hospital (2016). Available from http://www.sleepforscience.org/contentmgr/showdetails.php/id/93

24. Kuula L, Pesonen AK, Martikainen S, Kajantie E, Lahti J, Strandberg T, et al. Poor sleep and neurocognitive function in early adolescence. Sleep Med (2015) 16(10):1207–12. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2015.06.017

25. Simola P, Laitalainen E, Liukkonen K, Virkkula P, Kirjavainen T, Pitkäranta A, et al. Sleep disturbances in a community sample from preschool to school age. Child Care Health Dev (2012) 38(4):572–80. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2214.2011.01288.x

Keywords: sleep, subjective, self-report, children, measure

Citation: Erwin AM and Bashore L (2017) Subjective Sleep Measures in Children: Self-Report. Front. Pediatr. 5:22. doi: 10.3389/fped.2017.00022

Received: 09 November 2016; Accepted: 26 January 2017;

Published: 13 February 2017

Edited by:

Marie Leiner, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, USAReviewed by:

Mario Barreto, Sapienza University, ItalySandrine Rossi, University of Caen Lower Normandy, France

Copyright: © 2017 Erwin and Bashore. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Andrea M. Erwin, YW5kcmVhLmVyd2luQHRjdS5lZHU=

Andrea M. Erwin

Andrea M. Erwin Lisa Bashore

Lisa Bashore