- Division of Neonatology, Department of Pediatrics, University of California, San Diego, San Diego, CA, United States

When parents face a potentially life-limiting fetal diagnosis in pregnancy, they then have a series of decisions to make. These include confirmatory testing, termination, and additional choices if they choose to continue the pregnancy. A perinatal palliative team provides a safe, compassionate, and caring space for parents to process their emotions and discuss their values. In a shared decision-making model, the team explores how a family's faith, experiences, values, and perspectives shape the goals for care. For some families, terminating a pregnancy for any reason conflicts with their faith or values and pursuing life prolonging treatments in order to give their baby the best chances for survival is the most important. For others, having a postnatal confirmatory diagnosis of a life limiting or serious medical condition gives them the assurance they need to allow their child a natural death. Others want care to be comfort-focused in order to maximize the time they have to be together as a family. Through this journey, a perinatal palliative team can provide the support and encouragement for families to express their goals and wishes, as well as find meaning and hope.

Introduction

During pregnancy, ultrasounds and blood test results in the first two trimesters provide information about the fetus' health. When these results suggest a potentially life-limiting fetal diagnosis, parents are faced with a series of decisions. The first choices involve whether to obtain more diagnostic information via invasive or non-invasive tests during the pregnancy. Invasive testing includes chorionic villus sampling or amniocentesis in order to check for genetic mutations or aneuploidy. Parents need to weigh the risks of invasive testing against their desire for more information and greater certainty to help them with time-sensitive decisions. Although rates of pregnancy loss have been difficult to estimate, a recent meta-analysis suggests no significant risk of miscarriage with chorionic villus sampling and a miscarriage risk of 1:300 with amniocentesis (1). There are other risks associated with invasive testing, however, including bleeding, Rh sensitization, rupture of membranes, and infection (2). The recommended time frame to perform these invasive tests, between 10 and 20 weeks' gestation, is exactly when concerns about the fetus are raised and therefore a relatively narrow window of time in which to make decisions about testing (3). Diagnostic results may take up to 1–2 weeks to return. Although prenatal genetic testing has been expanded to include exome sequencing, it unfortunately cannot identify all possible abnormalities. Despite these limitations, the results may determine whether some families continue the pregnancy.

As an alternative, parents may first choose to decline invasive testing and opt for non-invasive testing which includes cell-free DNA screening and additional imaging. Cell-free DNA screening has a high sensitivity and specificity for Trisomy 21 and Trisomy 18, but lower performance for Trisomy 13, other chromosomal anomalies, and microdeletions (4). If non-invasive cell-free DNA screening is suggestive of a genetic abnormality, invasive testing is still needed to confirm the diagnosis before termination. Additional imaging includes fetal echocardiogram, three-dimensional fetal ultrasound, or fetal magnetic resonance imaging. For advice and opinion on the suspected diagnosis and outcomes, parents may also want to consult with pediatric subspecialists. What adds to the complexity of the situation is that maternal fetal medicine specialists have two patients: the mother and the fetus. Their duty is to separate information about the risks and benefits of various choices for both patients, recognizing that decisions made will have linked outcomes (5). As such, the maternal fetal medicine specialist will also review for the mother potential pregnancy complications associated with fetal anomalies: preeclampsia, preterm labor, polyhydramnios, and mirror syndrome (6–10).

After gathering as much data as possible, parents will consider whether or not to terminate the pregnancy. This decision often must be made within days or a couple of weeks after learning about a fetal abnormality. While many technologies offer to improve diagnostic certainty or prognostication, parents need to know about limitations in predicting survival and outcome variability. Each test, imaging modality, and consultation is an option for parents to pursue or decline. For some families, terminating a pregnancy is not consistent with their faith or values so undergoing invasive or non-invasive testing to inform a decision to terminate does not make sense. It is possible that a life-limiting fetal diagnosis may not be discovered until after termination is no longer an option, but families may still want information to prepare themselves for possible outcomes. Other families may feel the degree of uncertainty associated with some information acquired during pregnancy is not worth the additional stress. And some families want more time to process the news before obtaining more data.

Perinatal Palliative Consultation

“Perinatal palliative care refers to a coordinated care strategy that comprises options for obstetric and newborn care that include a focus on maximizing quality of life and comfort for newborns with a variety of conditions considered to be life-limiting in early infancy. With a dual focus on ameliorating suffering and honoring patient values, perinatal palliative care can be provided concurrently with life-prolonging treatment” (11). There is a misconception that palliative care applies only to cases where the goals are to allow a natural death. In fact, perinatal palliative teams advocate primarily for respect of parental wishes, supporting a spectrum of goals from comfort-focused to life-prolonging care. A perinatal palliative team is typically multidisciplinary including a physician, nurse, social worker, and spiritual counselor (12). Some palliative teams are imbedded within fetal diagnostic centers, enabling simultaneous palliative consultation (13). For centers without integrated palliative teams, however, there are barriers to early referral and palliative consultation might not occur for weeks (14). Because decisions to terminate often need to occur relatively quickly, families who chose termination are likely to miss the opportunity for perinatal palliative consultation. In practice, consultation with a perinatal palliative team most frequently occurs after parents have declined termination with plans instead to continue the pregnancy (15). No matter which decision parents make (i.e., to terminate or continue the pregnancy), however, all parents experience losses, find themselves planning for a future they did not hope for or expect, and can benefit from the additional support for decision-making that perinatal palliative teams can provide (16).

Providing support to parents as they make decisions is central to the perinatal palliative consultation. Amidst the variable and sometimes overwhelming emotions that parents can experience, the perinatal palliative team allows parents to explore their goals in order to promote shared decision-making with regard to obstetric management as well as postnatal care for the baby. Mixed, changing, and sometimes conflicting feelings of shock, concern, disbelief, denial, anger, love, shame, hope, and guilt are normal for parents to experience when hearing serious news about their baby (17). The perinatal palliative team fosters a safe, compassionate, and supportive environment for parents to process their emotions and discuss their values (18). Without the ability to address their feelings or spiritual distress, parents may not be ready to explore their hopes for their baby's care, let alone make changes to the plan of care. For example, a spiritual counselor on the perinatal palliative team is especially important if a parent is worried about the “right” thing to do with respect to her faith. Addressing the meaning of the situation in the context of her faith is necessary before approaching decision-making about treatment options for the baby. By validating and reflecting what parents express and in turn building trust, the perinatal palliative team can support a parent's voice in decision-making and facilitate communication between parents and other medical teams (19).

Birth Plans

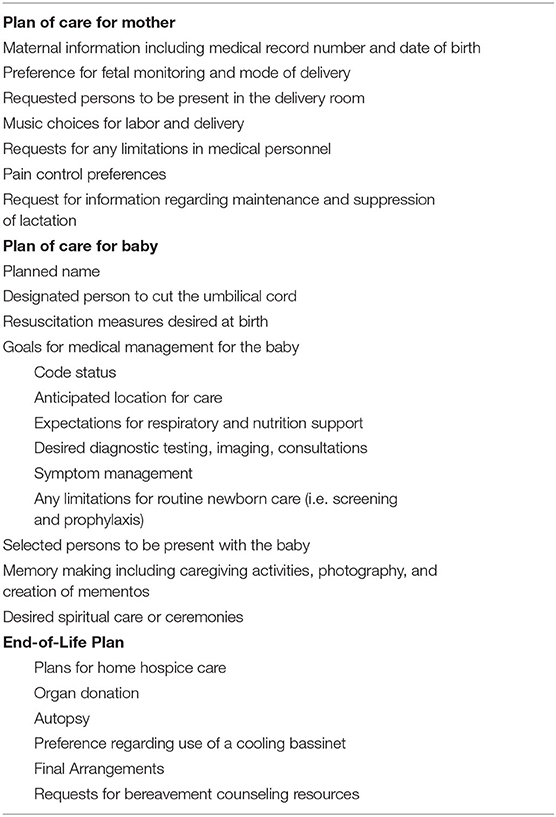

One way in which the perinatal palliative team supports a parent's voice and decisions is to collaborate on a birth plan. A birth plan is similar to an advanced directive for the pregnancy, delivery, and neonatal care. By sharing their birth plan with the medical team, families create additional opportunities for informed and shared decision-making. A birth plan documents parental hopes, wishes, and goals of care, serving as a communication tool for the entire medical team. Personalized birth plans vary in content but generally address the following components: pain control for the mother, preference for fetal monitoring, mode of delivery, who to be present in the delivery room, resuscitation measures desired at birth, medical management for the baby, as well as wishes for memory making, and ceremonies (20). Table 1 presents suggested topics for a birth plan. Writing a birth plan allows parents to identify and articulate goals ahead of time before a potentially overwhelming emotional moment. Parents have reported that creating and using a birth plan gave them a sense of control, was therapeutic, and helped them feel prepared (21).

The most challenging sections of the birth plan to complete usually address fetal monitoring, mode of delivery, and goals of care for baby's management. The 2019 ACOG Committee Opinion on Perinatal Palliative Care states that, “Decisions regarding the appropriateness of intrapartum fetal monitoring in cases like this should be individualized” (11). Some families are willing to accept the possibility of their baby's death during unmonitored labor in order to avoid the operative risks of cesarean section. Other families would rather have fetal monitoring during labor and if necessary, cesarean delivery for fetal distress, to increase the chances for their baby to be born alive. For example, some may want the opportunity for the entire family to meet the baby or to perform a ceremony at birth. For some families, having a postnatal confirmatory diagnosis of a life-limiting or serious medical condition gives them the assurance they need to allow their child to have a natural death. And other families may want to pursue life-prolonging treatments in order to give their baby the best chances for survival.

The uncertainty of whether the baby will survive the pregnancy and birth can make planning for the neonatal period challenging. Some families are ready to consider in detail the choices for baby's care after birth while other families want to defer those decisions until after the baby is born. The perinatal palliative team can help to explain how care for the newborn can be adapted to align with the goals of care. For example, families may want a time-limited trial of respiratory and nutrition support in order to see if the baby can breathe or eat on her or his own. If the baby is unable to breathe independently or feed by mouth safely, then families will need to consider whether providing long-term ventilation or artificial nutrition aligns with their goals for care. As it was during pregnancy, each test, imaging modality, and consultation for the baby is an option for parents to pursue or decline.

The birth plan will vary based on a family's faith, values, and experiences. For example, some families will want specific spiritual care or ceremonies after birth to honor their faith. But there are also some universal themes (22). Janvier et al. found that among families with children who lived with Trisomy 13 or 18, there were “common hopes to bring their child home, give their child a good life, and be together/a family” (23). Parents often have an intrinsic need to feel that they have “done the best that they could” for their child and want to avoid having regrets in the future (24). Maintaining hope is an important source of strength for parents when facing difficult situations (25). A parent's hope can change with time and new information, from hoping for a normal pregnancy, to hoping the baby will be healthier than predicted, to hoping that the baby will be alive at birth to meet the family. During goals of care planning, the perinatal palliative team can encourage and help families to maintain hope as circumstances change. Nearing the day of delivery, parents may worry about future regrets in choosing comfort-focused care, and want time-limited trials of therapy until the baby's diagnosis is confirmed. It is important to validate that concerns about regret can inform the goals of care and to acknowledge that allowing time to pass might reduce parental decision regret (26). There is also the possibility that at birth, the baby's presentation may not match the prenatal diagnosis thereby suggesting a different prognosis. Health care providers need to be flexible and remember that the birth plan serves as a guide for both mother and baby care providers, but it can be modified at any point before and after delivery. Ultimately, what is most important is that parents are supported, ideally by perinatal palliative teams alongside other medical teams, to discuss and express the rationale behind their decisions.

Memory Making

Whether the goals of care are focused on life-prolongation or comfort, most families whose baby may have a short life want to plan for memory making. The perinatal palliative team offers expertise and experience to support parents in the many ways they want to make memories. Memory making includes “any intervention or experience that encourages contact or interaction between the parents and newborn and any intervention that results in the creation or collection of mementos” (27). Mementos include molds of the baby's hands and feet, foot and handprints, blankets, hats, and clothing that the baby touched, as well as crib cards, hospital bands, and other personal items that were associated with the baby in the hospital. Now I Lay Me Down to Sleep is a non-profit international organization which offers free professional retouched photography to families who have a baby with a life-limiting condition (28). Families may want to take their own photographs or hire a photographer instead. Although parents may not want to see photos of their child right away, the portrait sessions give them the opportunity to have documentation of their child's life available for when they are ready. After the death of an infant, interviewed families emphasize the importance of having as many parenting experiences as possible to reflect upon in bereavement (29). Opportunities for caregiving can include bathing, dressing, and holding their baby as well as talking, singing, and playing music with their baby (30). Families recall that they needed encouragement and guidance to overcome their hesitation in order to spend time with their newborn (31). Some families introduce their baby to siblings and relatives to officially welcome him or her into the family. Making memories can not only validate the importance of the newborn's life and death but also create a sense of identity for individuals as parents, siblings, and grandparents.

Comfort Focused-Care

If families choose comfort-focused care for their baby, there may be an opportunity to continue the caregiving at home with hospice support. A hospice physician and team provide expertise in end-of-life care at home and ongoing bereavement counseling for the immediate family. A designated pediatrician is customarily not needed unless the goals of care change to include life-prolonging interventions. If the baby is unlikely to survive the trip home, some parents may want to room-in with the baby in the hospital while some families may not have the financial or logistical capacity to room-in. The perinatal palliative team can provide inpatient support to the primary neonatal team who will attend to the baby's pain and symptom management as well as support the family through the dying process. Many parents have little to no experience with death and will want to know what their baby will look like and feel in the last hours of living (32). Generally, babies in the dying process will become less active, sleeping more as time goes on. Any ability to swallow saliva will become impaired. With less intake, decreased urine and stool output is expected. Cool hands and feet along with mottling of the skin is normal. Less commonly, newborns may need treatment for seizures in the dying process. Eventually, when the baby is no longer conscious, periods of apnea, or Cheyne-Stokes pattern respirations will occur. Ordinary techniques to soothe babies, such as holding, rocking, and swaddling, are usually successful to minimize discomfort. Occasionally, morphine or lorazepam may be needed for symptom management of pain or agitation, respectively. Normalizing the signs of dying for families may reduce their anxiety and distress when the time comes. It is not possible to predict when death will occur, but it is possible to prepare families for the unpredictability of death. Using words such as “weeks not months,” “days not weeks,” or “hours not days,” can be helpful (33).

If medically possible, families can choose organ or tissue donation to create a hopeful and positive legacy. Organ procurement teams have specialized training and are the preferred communicators to maintain ethical and clinical standards while initiating organ donation discussions. Referrals to organ procurement organizations should be made in a timely manner when death is anticipated and may occur before birth (34). In addition, some families may agree to a full or limited autopsy to inform subsequent pregnancies or to improve medical knowledge for future families. Others may decline autopsy because they do not need more information, or their faith and values are not congruent with allowing an autopsy. Families may choose final arrangements based on family or faith traditions as well as their budget. Generally, cremation is less expensive than burial but the cost can vary by mortuary and location (35). Some parents will want to designate a relative or friend to do research and get quotes on available services and some families will prefer to do this work on their own.

After a baby dies, some families will want extended time with the baby and may want to use a cooling bassinet to decrease the rate that the body deteriorates (36). Others will say goodbye a few hours after the baby dies. There are physical and emotional aspects of lactation that need to be addressed. Some mothers will want to suppress breast milk production but need education on how to avoid painful engorgement and mastitis. Others will want to continue expressing and donate breast milk as a way to help other families and find meaning in the context of their loss and grief (37). It is important to recommend grief resources and counseling for families whether they go home with hospice or stay in the hospital setting. Some families may prefer to visit online bereavement resources first and others will want to start mental health therapy immediately (38, 39). The perinatal palliative team continues to support families as they make choices to honor their baby that may include a funeral, celebration of life, and donations to charities or research. Additionally, the team often maintains contact with families in bereavement. It is important to share with families that there are no right or wrong ways to grieve or feel when a baby dies.

Conclusion

Through the journey with a potentially life-limiting fetal diagnosis in pregnancy, a perinatal palliative team can provide the encouragement families need to make decisions based on their faith, values, and experiences. The team has the expertise to create a safe, compassionate, and caring environment for parents to process a number of intense emotions and discuss their values. Although parents must confront uncertainty and complex decision-making for both the mother and baby, perinatal palliative teams support parents to express their goals as well as find meaning and hope.

Author Contributions

KM-A agrees to be accountable for and conceived, drafted, revised, and approved all aspects of the work.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1. Salomon LJ, Sotiriadis A, Wulff CB, Odibo A, Akolekar R. Risk of miscarriage following amniocentesis or chorionic villus sampling: systematic review of literature and updated meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. (2019) 54:442–51. doi: 10.1002/uog.20353

2. Alfirevic Z, Mujezinovic F, Sundberg K. Amniocentesis and chorionic villus sampling for prenatal diagnosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2003) 2003:CD003252. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003252

3. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists' Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics Committee on Genetics Society for Maternal–Fetal Medicine. Practice bulletin No. 162: prenatal diagnostic testing for genetic disorders. Obstet Gynecol. (2016) 127:e108–22. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001405

4. Palomaki GE, Deciu C, Kloza EM, Lambert-Messerlian GM, Haddow JE, Neveux LM, et al. DNA sequencing of maternal plasma reliably identifies trisomy 18 and trisomy 13 as well as down syndrome: an international collaborative study. Genet Med. (2012) 14:296–305. doi: 10.1038/gim.2011.73

5. Marty CM, Carter BS. Ethics and palliative care in the perinatal world. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. (2018) 23:35–8. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2017.09.001

6. Burwick RM, Pilliod RA, Dukhovny SE, Caughey AB. Fetal hydrops and the risk of severe preeclampsia. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. (2019) 32:961–5. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2017.1396312

7. Nelson DB, Chalak LF, McIntire DD, Leveno KJ. Is preeclampsia associated with fetal malformation? A review and report of original research. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. (2015) 28:2135–40. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2014.980808

8. Kornacki J, Adamczyk M, Wirstlein P, Osiński M, Wender-Ozegowska E. Polyhydramnios — frequency of congenital anomalies in relation to the value of the amniotic fluid index. Ginekol Polska. (2017) 88:442–5. doi: 10.5603/GP.a2017.0081

9. Norton ME, Chauhan SP, Dashe JS. Society for maternal-fetal medicine (SMFM) clinical guideline #7: nonimmune hydrops fetalis. Am J Obstetrics Gynecol. (2015) 212:127–39. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.12.018

10. Quaresima P, Homfray T, Greco E. Obstetric complications in pregnancies with life-limiting malformations. Curr Opin Obstetrics Gynecol. (2019) 31:375–87. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0000000000000583

11. Perinatal palliative care: ACOG COMMITTEE OPINION Number 786. Obstet Gynecol. (2019) 134:e84–9. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003425

12. Balaguer A, Martín-Ancel A, Ortigoza-Escobar D, Escribano J, Argemi J. The model of palliative care in the perinatal setting: a review of the literature. BMC Pediatr. (2012) 12:25. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-12-25

13. Kukora S, Gollehon N, Laventhal N. Antenatal palliative care consultation: implications for decision-making and perinatal outcomes in a single-centre experience. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. (2017) 102:F12–6. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2016-311027

14. Marc-Aurele KL, Nelesen R. A five-year review of referrals for perinatal palliative care. J Palliat Med. (2013) 16:1232–6. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2013.0098

15. Marc-Aurele KL, Hull AD, Jones MC, Pretorius DH. A fetal diagnostic center's referral rate for perinatal palliative care. Ann Palliat Med. (2017) 7:177–85. doi: 10.21037/apm.2017.03.12

16. Lou S, Jensen LG, Petersen OB, Vogel I, Hvidman L, Møller A, et al. Parental response to severe or lethal prenatal diagnosis: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Prenat Diagn. (2017) 37:731–43. doi: 10.1002/pd.5093

17. Luz R, George A, Spitz E, Vieux R. Breaking bad news in prenatal medicine: a literature review. J Reprod Infant Psychol. (2017) 35:14–31. doi: 10.1080/02646838.2016.1253052

18. O'Connell O, Meaney S, O'Donoghue K. Anencephaly; the maternal experience of continuing with the pregnancy. incompatible with life but not with love. Midwifery. (2019) 71:12–8. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2018.12.016

19. Moro TT, Kavanaugh K, Savage TA, Reyes MR, Kimura RE, Bhat R. Parent decision making for life support decisions for extremely premature infants: from the prenatal through end-of-life period. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. (2011) 25:52–60. doi: 10.1097/JPN.0b013e31820377e5

20. Limbo DR, Wool C, Carter B (editors). Handbook of Perinatal and Neonatal Palliative Care: A Guide for Nurses, Physicians, and Other Health Professionals. 1 ed. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company (2019). doi: 10.1891/9780826138422

21. Cortezzo DE, Bowers K, Cameron Meyer M. Birth planning in uncertain or life-limiting fetal diagnoses: perspectives of physicians and parents. J Palliat Med. (2019) 22:1337–45. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2018.0596

22. Blakeley C, Smith DM, Johnstone ED, Wittkowski A. Parental decision-making following a prenatal diagnosis that is lethal, life-limiting, or has long term implications for the future child and family: a meta-synthesis of qualitative literature. BMC Med Ethics. (2019) 20:56. doi: 10.1186/s12910-019-0393-7

23. Janvier A, Farlow B, Barrington KJ. Parental hopes, interventions, and survival of neonates with trisomy 13 and trisomy 18. Am J Med Genet Part C Semin Med Genet. (2016) 172:279–87. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.31526

24. Côté-Arsenault D, Denney-Koelsch E. “Have no regrets:” parents' experiences and developmental tasks in pregnancy with a lethal fetal diagnosis. Soc Sci Med. (2016) 154:100–9. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.02.033

25. Janvier A, Barrington K, Farlow B. Communication with parents concerning withholding or withdrawing of life-sustaining interventions in neonatology. Semin Perinatol. (2014) 38:38–46. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2013.07.007

26. Wool C, Limbo R, Denny-Koelsch EM. “I would do it all over again”: cherishing time and the absence of regret in continuing a pregnancy after a life-limiting diagnosis. J Clin Ethics. (2018) 29:227–36.

27. Thornton R, Nicholson P, Harms L. Scoping review of memory making in bereavement care for parents after the death of a newborn. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. (2019) 48:351–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jogn.2019.02.001

28. Now I Lay Me Down to Sleep | Now I Lay Me Down To Sleep. (2019). Available online at: https://www.nowilaymedowntosleep.org/ (accessed August 29, 2019).

29. Tan JS, Docherty SL, Barfield R, Brandon DH. Addressing parental bereavement support needs at the end of life for infants with complex chronic conditions. J Palliat Med. (2012) 15:579–84. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2011.0357

30. Wool C, Catlin A. Perinatal bereavement and palliative care offered throughout the healthcare system. Ann Palliat Med. (2018) 8(Suppl. 1):S22–9. doi: 10.21037/apm.2018.11.03

31. Abraham A, Hendriks MJ. “You can only give warmth to your baby when it's too late”: parents' bonding with their extremely preterm and dying child. Qual Health Res. (2017) 27:2100–15. doi: 10.1177/1049732317721476

32. Catlin A, Carter B. Creation of a neonatal end-of-life palliative care protocol. J Perinatol. (2002) 22:184–95. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7210687

33. Bodtke S, Ligon K. Hospice and Palliative Medicine Handbook: A Clinical Guide. 1st ed. Lexington: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform (2016).

34. Medicare Medicaid programs; hospital conditions of participation; identification of potential organ tissue eye donors transplant hospitals' provision of transplant-related data–HCFA. Final rule. Fed Regist. (1998) 63:33856–75.

35. How Much Does it Cost to Cremate? The Living Urn. Available online at: https://www.thelivingurn.com/blogs/news/how-much-does-it-cost-to-cremate

36. Smith P, Vasileiou K, Jordan A. Healthcare professionals' perceptions and experiences of using a cold cot following the loss of a baby: a qualitative study in maternity and neonatal units in the UK. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2020) 20:175. doi: 10.1186/s12884-020-02865-4

37. Cole JCM, Schwarz J, Farmer M-C, Coursey AL, Duren S, Rowlson M, et al. Facilitating milk donation in the context of perinatal palliative care. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. (2018) 47:564–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jogn.2017.11.002

38. Still, Standing Magazine. Available online at: https://stillstandingmag.com/

39. Glow in the Woods. Available online at: http://www.glowinthewoods.com/

Keywords: perinatal palliative care (PPC), decision-making, pregnancy, life-limiting fetal diagnoses, decisions

Citation: Marc-Aurele KL (2020) Decisions Parents Make When Faced With Potentially Life-Limiting Fetal Diagnoses and the Importance of Perinatal Palliative Care. Front. Pediatr. 8:574556. doi: 10.3389/fped.2020.574556

Received: 20 June 2020; Accepted: 10 September 2020;

Published: 22 October 2020.

Edited by:

Elvira Parravicini, Columbia University, United StatesReviewed by:

Charlotte Wool, York College of Pennsylvania, United StatesMarlyse Frieda Haward, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, United States

Copyright © 2020 Marc-Aurele. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Krishelle L. Marc-Aurele, a21hdXJlbGVAaGVhbHRoLnVjc2QuZWR1

Krishelle L. Marc-Aurele*

Krishelle L. Marc-Aurele*