- 1Department of Exercise and Nutrition Sciences, Milken Institute School of Public Health, The George Washington University, Washington, DC, United States

- 2Department of Psychology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, United States

Introduction

Sugar-sweetened beverage (SSB) intake contributes to obesity and cardiometabolic disease (1). Children's SSB consumption considerably exceeds public health recommendations (2), and efforts to reduce intake have had limited success (3). In addition to high sugar content, many SSBs also contain caffeine, and caffeinated SSBs are the predominant source of caffeine intakes among youth (4). Sugar activates central reward pathways, and similar to drugs of abuse, stimulates dopamine release (5), and meets several criteria for addiction (6). Chronic caffeine intake causes tolerance and withdrawal in children (7), which are core behavioral indicators of substance use disorders (SUDs) (6).

Compelling evidence for addictive-like responses to excess sugar intake is emerging, with accumulating support in rodent models (5). Synergistic biopsychological effects of caffeine and sugar may reinforce unfavorable beverage consumption patterns (7). SSBs are a novel stimulus from an evolutionarily standpoint, yet products containing sugar and caffeine (e.g., energy drinks) are increasingly available (8) and heavily advertised to children (7). Children have developing brains and less inhibitory control compared to adults, and thus, are particularly vulnerable to addictive substances (9). Added caffeine in already highly palatable SSBs increases their hedonic and reinforcing properties (10) and may further promote excess added sugar intakes (11).

Emerging evidence indicates that children's consumption of highly processed foods, typically high in added sugar and/or saturated fat, can lead to an addictive process reflected by core behavioral indicators of SUDs (12). These include craving, loss of control, tolerance, and withdrawal (12). Children who demonstrate more signs of addiction in their highly processed food consumption are more likely to have higher reward drive for food and higher body mass index (12). Signs of addiction have also been reported among children in response to frequent SSB consumption (13, 14). In our qualitative study (14), parents of children 8–17 years old reported that children experienced physical and affective withdrawal symptoms when caffeinated SSB intake was restricted. Similarly, Falbe et al. (13) reported that adolescents, who reported habitual SSB consumption, regardless of whether SSBs were caffeinated or caffeine-free indicated increased SSB cravings and headaches, and decreased motivation, contentment, concentration, and well-being during 72 h of SSB cessation. It is likely that other aspects of addiction (e.g., tolerance, craving, repeated unsuccessful efforts to reduce) represent important and overlooked obstacles to sustained SSB reduction. Herein, we propose that children's SSB consumption may reflect SUD symptomology and focus specifically on caffeinated SSBs, which are manufactured to contain a highly rewarding mixture of added sugar and caffeine, two ingredients that do not naturally occur in combination.

DSM-5 Substance Use Criteria Are Highly Applicable to Children's SSB Intake

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) contains 11 criteria for SUDs (6). The DSM-5 describes a continuum of SUD severity, spanning mild (2–3 symptoms), moderate (4–5 symptoms), and severe (≥6 symptoms). Not all criteria need to be met to constitute a SUD. In our prior work in development and validation of the dimensional Yale Food Addiction Scale for Children 2.0 (dYFAS-C 2.0) (15), problem-focused symptoms (e.g., failure to fulfill obligations due to recurrent substance use) were seldom reported in children, which is consistent with other SUDs. Thus, these items were removed from the measure. In contrast, symptoms of mechanistic dysfunction (e.g., loss of control, craving, tolerance, withdrawal) were widely endorsed among children and were associated with severe eating pathology and obesity (15). Thus, over-reliance on problem-focused criteria that interfere with day-to-day functioning, which are less relevant for children, may lead to underdiagnosis of SUDs in youth even when key indicators of addictive behavior are present (15).

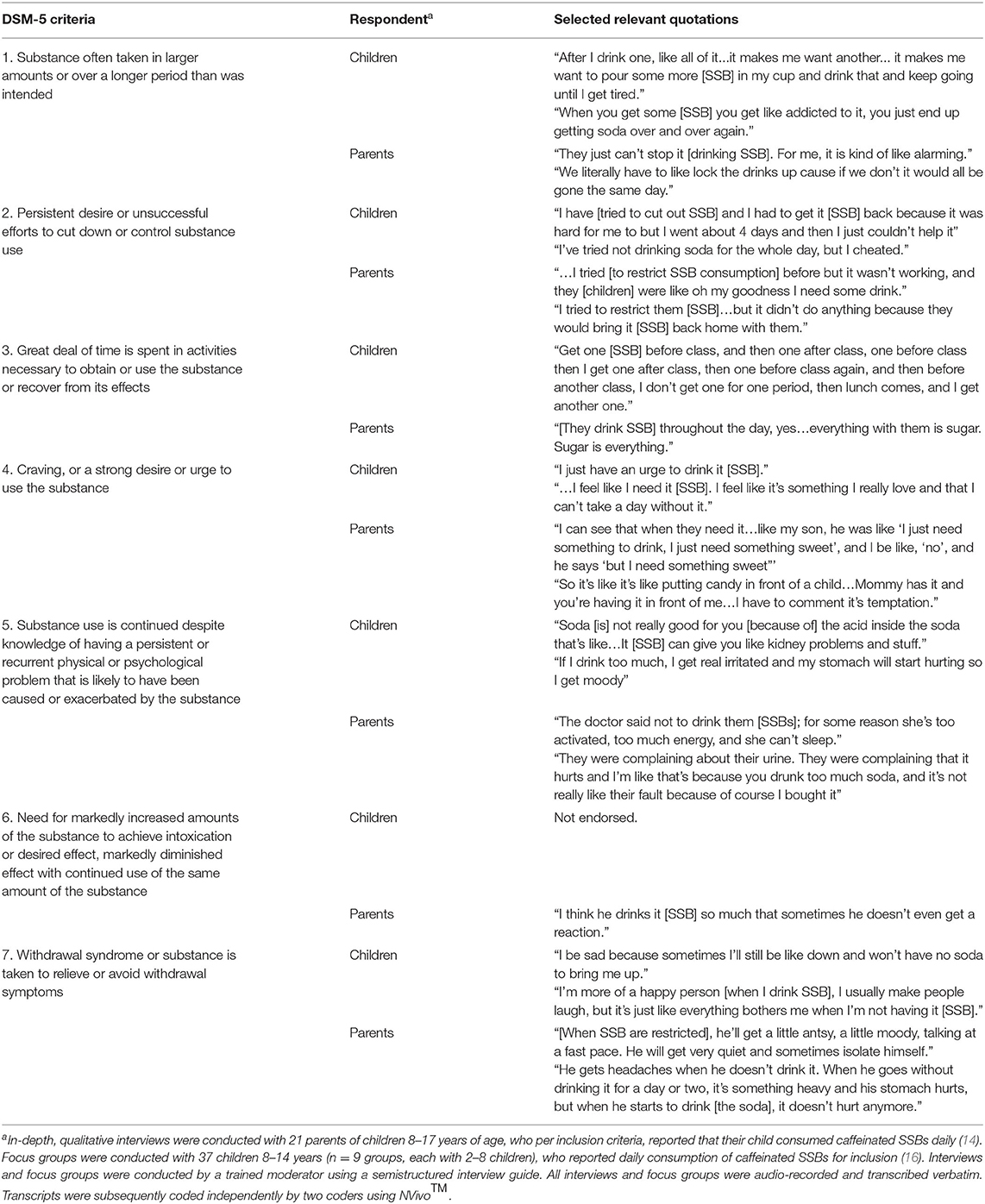

We examined the extent to which responses during in-depth interviews with parents (n = 21) (14) and focus groups with children (n = 37) (16) about SSB consumption (two separate cohorts, not dyads) reflected DSM-5 SUD criteria. We specifically focused on criteria pertaining to mechanistic dysfunction (Table 1). Details of the parent interviews and focus groups with children who reported daily caffeinated SSB consumption were previously published and are described elsewhere (14, 16).

Table 1. Parent and/or child-reported sugar-sweetened beverage consumption behaviors consistent with DSM-5 substance use disorder (SUD) criteria.

Behaviors consistent with 5 of the 7 DSM-5 SUD criteria pertinent to children and reflective of mechanistic dysfunction (see criteria in Table 1) were endorsed by both children and parents. One mechanistic criterion that was not widely endorsed was the need to spend a great deal of time in activities to obtain, use, or recover from the substance. This is not surprising, given that caffeinated SSBs are widely available and have a mild intoxication effect. Limited endorsement of this criterion is also consistent with findings previously reported for food and cigarettes (15). Interestingly, tolerance (#6 in Table 1) was endorsed by parents, but not by children, and may be due to tolerance being a complex concept that may not be recognized by children.

Discussion

Consideration of SUD symptomology in future efforts to reduce children's SSB intake (and specifically caffeinated SSB intake) is warranted. For example, parallels between children's SSB consumption behaviors and well-documented patterns in SUDs further emphasize the need for beverage companies to stop marketing SSBs to youth (17). This is especially important for “non-traditional,” caffeinated SSBs such as sugar-sweetened teas, coffees, and energy drinks, sales of which have been increasing among youth (18). Incorporation of psycho-behavioral approaches used in complex and multifactorial SUDs may be useful for addressing excess SSB consumption among children. For example, children may be taught to identify situations where they experience cravings for SSB and to use self-regulation strategies to successfully reduce SSB consumption (19). Furthermore, interventions may benefit from identifying and addressing situational and contextual cues for children's SSB intake, which may result from learned associations developed over time through repeated SSB exposure (20). Addressing withdrawal symptoms or other aversive physical and affective responses when SSB intake is being reduced may be a particularly important treatment target.

Children begin consuming caffeinated SSBs at much younger ages than is typical for other addictive substances. Thus, interventions to address SSB intake require more active participation from parents than traditional SUDs. Furthermore, dietary behaviors in childhood track into adolescence and adulthood, underscoring the need to address SSB intake early in life. Reported use of SSBs to reduce negative affect is particularly concerning because intentional use of a substance to improve mood may generalize to use of other substances later in life (7). The current SUD criteria have been criticized for being context-dependent and overemphasizing problems that may arise rather than mechanisms that underpin the behavior (21). Consumption of SSBs to cope with negative emotions may serve as an important potential indicator of problematic substance use and may be particularly relevant for children, who are less likely to endorse problem-focused criteria, relative to adults (15). However, future research is required to determine the utility that adding this as a formal criteria would provide beyond the existing criteria.

Leveraging existing SUD frameworks provides a unique opportunity to enhance existing efforts to reduce children's SSB consumption. This may be especially critical for children from disadvantaged backgrounds, who are at disproportionate risk of suffering from SUDs (22) and consume the largest quantities of SSBs (2). Striking parallels between children's SSB consumption and SUD criteria emphasize the need to create and disseminate tools to identify problematic SSB consumption behaviors in high-risk children, with the goal of tailoring counseling and resources to elicit and sustain SSB behavior change.

Author Contributions

ACS, LP, and ANG designed the project. ACS wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors revised the manuscript and approve of the final version submitted to Frontiers in Pediatrics.

Funding

This project was supported by a KL2 Career Development Award (PI: Sylvetsky), under Parent Award Numbers UL1TR001876 and KL2TR001877 from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or NCATS.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1. Hu FB. Resolved: there is sufficient scientific evidence that decreasing sugar-sweetened beverage consumption will reduce the prevalence of obesity and obesity-related diseases. Obes Rev. (2013) 14:606–19. doi: 10.1111/obr.12040

2. Rosinger A, Herrick K, Gahche J, Park S. Sugar-sweetened beverage consumption among U.S. Youth, 2011–2014. NCHS Data Brief. 2017:1–8.

3. Kirkpatrick SI, Raffoul A, Maynard M, Lee KM, Stapleton J. Gaps in the evidence on population interventions to reduce consumption of sugars: a review of reviews. Nutrients. (2018) 10:1036. doi: 10.3390/nu10081036

4. Knight CA, Knight I, Mitchell DC, Zepp JE. Beverage caffeine intake in US consumers and subpopulations of interest: estimates from the Share of Intake Panel survey. Food Chem Toxicol. (2004) 42:1923–30. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2004.05.002

5. Avena NM, Rada P, Hoebel BG. Evidence for sugar addiction: behavioral and neurochemical effects of intermittent, excessive sugar intake. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. (2008) 32:20–39. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2007.04.019

6. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edn. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. (2013).

7. Temple JL. Review: trends, safety, and recommendations for caffeine use in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2019) 58:36–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2018.06.030

9. Kolb B, Gibb R. Brain plasticity and behaviour in the developing brain. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2011) 20:265–76.

10. Griffiths RR, Vernotica EM. Is caffeine a flavoring agent in cola soft drinks? Arch Fam Med. (2000) 9:727–34. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.8.727

11. Keast RS, Swinburn BA, Sayompark D, Whitelock S, Riddell LJ. Caffeine increases sugar-sweetened beverage consumption in a free-living population: a randomised controlled trial. Br J Nutr. (2015) 113:366–71. doi: 10.1017/S000711451400378X

12. Parnarouskis L, Schulte EM, Lumeng JC, Gearhardt AN. Development of the highly processed food withdrawal scale for children. Appetite. (2019) 147:104553. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2019.104553

13. Falbe J, Thompson HR, Patel A, Madsen KA. Potentially addictive properties of sugar-sweetened beverages among adolescents. Appetite. (2019) 133:130–7. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2018.10.032

14. Sylvetsky AC, Visek AJ, Turvey C, Halberg S, Weisenberg JR, Lora K, et al. Parental concerns about child and adolescent caffeinated sugar-sweetened beverage intake and perceived barriers to reducing consumption. Nutrients. (2020) 12:885. doi: 10.3390/nu12040885

15. Schiestl ET, Gearhardt AN. Preliminary validation of the Yale Food Addiction Scale for Children 2.0: a dimensional approach to scoring. Eur Eat Disord Rev. (2018) 26:605–17. doi: 10.1002/erv.2648

16. Sylvetsky AC, Visek AJ, Halberg S, Rhee K, Ongaro Z, Essel KE, et al. Beyond taste and easy access: physical, cognitive, interpersonal, and emotional reasons for sugary drink consumption among children and adolescents. Appetite. (2020) 155:104826. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2020.104826

17. Powell LM, Wada R, Khan T, Emery SL. Food and beverage television advertising exposure and youth consumption, body mass index and adiposity outcomes. Can J Econ. (2017) 50:345–64. doi: 10.1111/caje.12261

18. Vercammen KA, Koma JW, Bleich SN. Trends in energy drink consumption among U.S. adolescents and adults, 2003–2016. Am J Prev Med. (2019) 56:827–33. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.12.007

19. Rhee KE, Kessl S, Manzano MA, Strong DR, Boutelle KN. Cluster randomized control trial promoting child self-regulation around energy-dense food. Appetite. (2019) 133:156–65. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2018.10.035

20. Grenard JL, Stacy AW, Shiffman S, Baraldi AN, MacKinnon DP, Lockhart G, et al. Sweetened drink and snacking cues in adolescents: a study using ecological momentary assessment. Appetite. (2013) 67:61–73. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2013.03.016

21. Martin CS, Langenbucher JW, Chung T, Sher KJ. Truth or consequences in the diagnosis of substance use disorders. Addiction. (2014) 109:1773–8. doi: 10.1111/add.12615

Keywords: sugar, beverages, obesity, caffeine, soda

Citation: Sylvetsky AC, Parnarouskis L, Merkel PE and Gearhardt AN (2020) Children's Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Consumption: Striking Parallels With Substance Use Disorder Symptoms. Front. Pediatr. 8:594513. doi: 10.3389/fped.2020.594513

Received: 13 August 2020; Accepted: 02 October 2020;

Published: 12 November 2020.

Edited by:

Richard Eugene Frye, Phoenix Children's Hospital, United StatesReviewed by:

Tammy Chung, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, United StatesSatinder Aneja, Sharda University, India

Copyright © 2020 Sylvetsky, Parnarouskis, Merkel and Gearhardt. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Allison C. Sylvetsky, YXN5bHZldHNAZ3d1LmVkdQ==

Allison C. Sylvetsky

Allison C. Sylvetsky Lindsey Parnarouskis

Lindsey Parnarouskis Patrick E. Merkel

Patrick E. Merkel Ashley N. Gearhardt

Ashley N. Gearhardt