- Griffith Health, Griffith University, Southport, QLD, Australia

For perinatal palliative care (PPC) to be truly holistic, it is imperative that clinicians are conversant in the cultural, spiritual and religious needs of parents. That cultural, spiritual and religious needs for parents should be sensitively attended to are widely touted in the PPC literature and extant protocols, however there is little guidance available to the clinician as to how to meet these needs. The objective of this review article is to report what is known about the cultural, spiritual and religious practices of parents and how this might impact neonates who are born with a life-limiting fetal diagnosis (LLFD). The following religions will be considered—Islam, Buddhism, Hinduism, Judaism, and Christianity—in terms of what may be helpful for clinicians to consider regarding rituals and doctrine related to PPC. Data Sources include PubMed, Ovid, PsycInfo, CINAHL, and Medline from Jan 2000–June 2020 using the terms “perinatal palliative care,” “perinatal hospice,” “cultur*,” and “religiou*.” Inclusion criteria includes all empirical and research studies published in English that focus on the cultural and religious needs of parents who opted to continue a pregnancy in which the fetus had a life-limiting condition or had received perinatal palliative care. Gray literature from religious leaders about the Great Religions were also considered. Results from these sources contributing to the knowledge base of cultural, spiritual and religious dimensions of perinatal palliative care are considered in this paper.

Introduction

Perinatal palliative care (PPC) is a specialized branch of pediatric palliative care that considers an interdisciplinary strategy for the care of newborns with life-limiting or life-threatening conditions. The World Health Organization defines palliative care as the “primary goal for the provision of a good quality of life for those with life-threatening diseases.” This expands to palliative care for children and infants as a specialized field that extends to the family of children and infants. The WHO has set up principles of palliative care for children, and it includes the following points: “(a) Complete care of the infant must be taken including mind, soul, and body; (b) Moral support to the family should be provided; (c) Palliative care should start when the decision for not providing any more intensive care has been made; and (d) Care should be implemented even when resources are limited” (1).

For PPC to be truly holistic, it is imperative that clinicians must be conversant in the cultural, spiritual, and religious needs of parents. The need for cultural, spiritual, and religious considerations to be sensitively attended to is widely touted in the literature on PPC and extant protocols; however, there is little guidance available to the clinician on meeting these needs.

In recent times, most life-limiting fetal diagnoses (LLFD) are made during the prenatal period at a time that should represent hope and joy for parents and families. When faced with an LLFD, however, these hopes and dreams of a healthy child fade. It is at the margins of life and death that people consider the existential questions of life and their spirituality, and, at times, they may even question their religious beliefs. The death of their child will lead to maladaptive grief, long-term diminished quality of life, and symptoms linked to psychological morbidity if parents are unable to reconcile these very personal needs (2). Religious, cultural, and spiritual beliefs can bring profound comfort and healing for parents faced with an LLFD, and the majority of parents want the healthcare team to have the sensitivity and skills to discuss and tend to these needs (2).

While it is not possible for the clinician to be knowledgeable about all religious tenets and cultural norms encountered in practice, having the knowledge of the most common religions and how these religious tenets apply to infants with an LLFD or that are born at the margins of viability can assist parents greatly. Sadeghi et al. (3) identified that belief in the force of the supernatural, the need for comfort of the soul, and human dignity for the newborn were the important dimensions for parents of the infants who were not expected to survive (3).

The large variations in religious practice are known from the outset, and it is beyond the reach of this review to identify and accept all of these variations exhaustively. The objective of this review is to report on what is known about the cultural, spiritual, and religious practices of parents and how this might impact the neonates who are born with an LLFD. The following religions will be considered in terms of what may be helpful for clinicians to consider regarding rituals and doctrine related to PPC: Islam, Buddhism, Hinduism, Judaism, and Christianity.In addition, cultural and spiritual needs will be addressed.

Materials and Methods

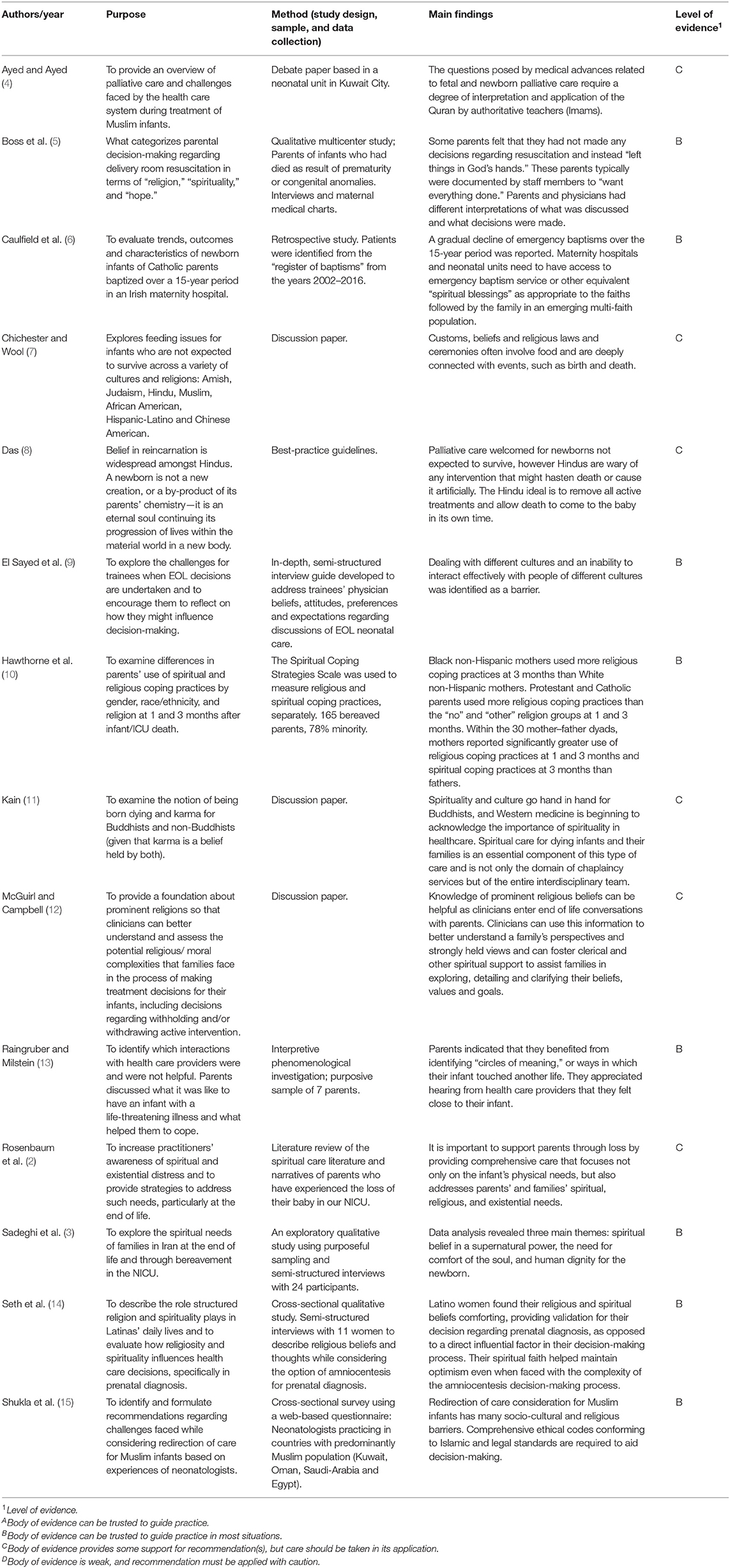

Data sources for this review included PubMed, Ovid, PsycInfo, CINAHL, and Medline. The data from January 2000 to August 2020 were collected using the terms “perinatal palliative care,” “perinatal hospice,” “cultur*,” “spiritual*,” and “religiou*.” The inclusion criteria included all empirical and research studies published in English that focused on the cultural, spiritual, and religious needs of parents who opted to continue with their pregnancy, where the fetus had a life-limiting condition or had received PPC. Results from these studies contributing to the knowledge base of cultural and religious dimensions of PPC are considered in this review. Table 1 provides details of the types of papers included and their level of evidence.

In addition to these published papers, sources discussing the principles of the Great Religions were also included to provide a background about religious doctrine, beliefs, and current global demographics.

Discussion

Religious Considerations for Parents

We live in a multicultural, multi-faith world, where religion is seemingly more important than it has ever been, with four out of five people identifying as belonging to an organized faith (16). Christianity is the fastest growing religion, with Islam and Hinduism also experiencing global growth (16). Medicine, in particular, does not accept religious concepts and practices as part of the medical model (17); however, it is increasingly important in considering how faith intersects with the biomedical and psychosocial model of health. Having one's religious and spiritual beliefs recognized brings comfort and may also promote optimism, even when facing a complex prenatal diagnosis with uncertain outcomes (14).

Religion is somewhat simpler to define than spirituality. It considers beliefs, practices, and rituals and may also include beliefs about spirits, both good (angels) and bad (demons). Religion can be observed either publicly, as part of a community, or privately, and often as both (18). It is estimated that 78% of Americans have belief in God, with another 15% believing in a “higher power” or something “bigger than themselves.” In terms of prayer, 84% of Americans believe that their chance of recovery is increased by the act of praying for the sick; 79% believe in the presence of “miracles”; and 72% perceive that God can cure incurable conditions (2). Having religious beliefs can assist people by bringing some order to life when events make life untenable with the offering of rituals, traditions, and guidance. Further, the concept of an “afterlife,” or existential heaven, may bring great comfort to parents faced with an infant with an LLFD.

In a discussion paper, McGuirl and Campbell (12) claimed that knowledge of the most common religious beliefs is helpful for clinicians in having end-of-life conversations with parents who are making decisions for their children, including the decision on withholding and/or withdrawing from active involvement in interventions. However, there are also studies that associate religious beliefs with an increased propensity toward life-prolonging care that may prolong the suffering of infants with life-limiting conditions (2).

In the Southeast and East Asian community, religious and spiritual values may also directly affect the pregnancy decisions linked to genetics. Leung et al. (19) stated that while Chinese women in Hong Kong generally support the termination of pregnancy in the early stages for chromosomal defects and non-medical reasons, religious context is a major contributor to the negative attitudes toward termination. Notably, most women in the study also accepted that for an undesired fetal gender, termination should not be performed. Meanwhile, the health values of some strongly traditional Southeast Asian groups concentrate on the unity of mind and body and may clash with the biomedical model practiced in the United States. Surgery, for instance, is considered a breach of the “conscience”; blood is considered irreplaceable once drawn; and prenatal treatment is considered unnecessary because pregnancy is not considered a disease (20).

It is critical that clinicians are aware of the importance of inquiring about the social and religious affiliations of a patient, as these do not always correlate with the specified religious affiliation of the patient and these are important guiding principles in perinatal decision-making.

Islam

Islam impacts all aspects of daily living: from eating to clothing to health practices. Islam has been pursued for more than 1,400 years, originating from Mohammad in Mecca, Arabia, who is believed to be the last prophet sent by God (Allah, translated literally as “God”). Clinicians should be aware of the Five Pillars of Islam and work with families to understand how this belief may influence their decision-making when having a baby with an LLFD. For Muslims, the Five Pillars are five broad principles that allow them to live a good and responsible life. These include the following: The Declaration of Faith (Shahada); praying five times a day (Salat); giving charity (Zakah); fasting during the month of Ramadan (Sawm); and a pilgrimage to Mecca at least once (Hajj). It is important that healthcare providers are cognizant and do not confuse Islamic traditions with cultural traditions.

Comprised of 24.1% of the global population (21), Muslims believe that Allah is in control of both the beginning and the end of life. All outcomes, including death, are predetermined by Allah (21). The teachings of their holy book (the Quran) influences healthcare practices and the pivotal moments of life, such as birth, death, and illness (4). Table 2 provides guidance to clinicians caring for infants of Muslim families.

For practitioners of Islam (Muslims), the pervasive belief is that curative medical interventions come from Allah, and healthcare professionals are the medium for delivering the will of Allah. The Quran provides guidance and is considered the source of healing for psychological and spiritual distress. If family members, including infants and children, require surgical or medical measures, the Quran can be used as an addendum to resolve theological, social, and cultural needs (4).

To facilitate decision-making, rigorous ethical codes are required that adhere to the Islamic social and legal standards (15). When an LLFD is made, the Quran states quite clearly that a pregnancy should not be terminated for reasons that might include financial fears or fears that the parent/s will not be able to care for their infant after birth. However, when considering extremely premature infants born at <25 weeks of gestation (12), the “legal opinion” of the Islamic society is that two specialist physicians need to be involved in the decision-making, and while for some Muslims the sole decision-maker might be the physician who is treating the infant, the parents should always be involved in the decision-making with as much autonomy afforded to them in their decision-making role. The treating physician should, however, freely consult with other pediatricians/neonatologists and caregivers.

The steps of the legal process following the diagnosis of an LLFD according to the Islamic society are as follows: confirmation of lethal malformations by ultrasound and/or chromosomal analysis; approval of the malformation by at least two neonatology and perinatology specialists; documentation of the type of malformation in the medical records of the mother; obtaining the written consent from parents or their delegates; termination of the pregnancy is permitted if the gestational age is longer than 19 weeks, but only if the continuation of the pregnancy is expected to result in the death of the mother and if fetal death in utero is confirmed. The infant can receive PPC if born alive (4).

In summary, clinicians need to take care in exploring with families the role of their religion in decision-making and to have some awareness of the teachings and beliefs that guide their daily lives. An understanding of their religious needs provides a framework for discussion and allows the healthcare team to support the parents through difficult decision-making processes (12).

Buddhism

Buddhism is a faith that was established more than 2,500 years ago in India by Siddhartha Gautama (“the Buddha”). Comprised of 6.9% of the global population, Buddhists recognize suffering as central to human existence. Suffering is unavoidable and life-limiting illness serves to prompt reflection on the ultimate meaning of life. Death is associated with rebirth (reincarnation), and having serene surroundings at the time of death and during the dying process is important to the dignity of the person and for their rebirth (21). Although Buddhists believe that death is a part of life, the religion is not somber, but it is full of serenity, hope, and wisdom, but recognizing that suffering is unavoidable, just as death is unavoidable. Central to this is a belief in karma (as is also in Hinduism), or the sum of one's actions (and inactions) in their current and previous states of existence. The sum of these karmic actions decides their fate in future existences, influencing how they will be reincarnated and what they will be reincarnated as. Karma, however, is not isolated to Hinduism and Buddhism: in America, 27% of the population were reported to have belief in reincarnation and “some form of karma” (11). In 2014, Kain explored the notion of being born after dying and karma for Buddhists and non-Buddhists, in a discussion paper, reported the dilemma of the karmic “baggage” of being born after dying. Because Buddhist scripture does not delineate at which point death occurs along the continuum, whether at the beginning of life or at the end, Buddhist parents can take comfort by realizing that their infant being reborn as a human suggests that their child already had a degree of untarnished karmic “baggage.” Buddhist traditions accept human birth as a beneficial rebirth since the conditions for a sentient being to attain enlightenment are ideal only as a human being, which is the ultimate objective for the Buddhist practitioner (11).

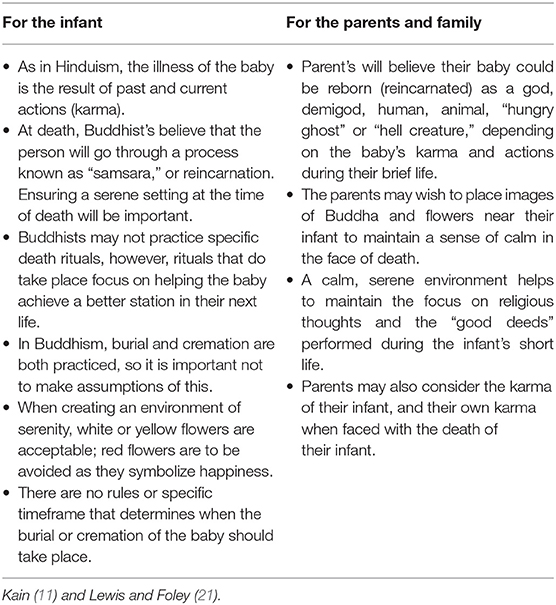

Table 3 summarizes what clinicians need to know in terms of caring for infants of Buddhist families, especially for both the infant and the parents.

Essentially, when the death of their infant becomes imminent, Buddhist parents need to be able to focus on caring for the spiritual state of the infant rather than unnaturally prolonging the life of their child, as this will encourage a good rebirth. It is important for medication to not interfere with consciousness. When caring for Buddhist families, the clinician will benefit from demonstrating the “right understanding” (this is an appreciation of the four noble truths: the truth of suffering; the truth of the cause of suffering; the truth of the end of suffering; and the truth of the course that frees us from suffering) and an understanding of mindfulness (the whole-body-and-mind awareness of the present moment), which in turn creates good karma for the child and encourages the well-being of the child. In both its present state and as a living being, this will benefit the child in the current life and for the next life to come (11).

Christianity

Christianity is a monotheistic Abrahamic faith. Its ideology is based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ of Nazareth, practiced by over 30% of the global population. Its followers, known as Christians, include many denominations: in the Western world, Roman Catholic; Protestant (Adventist, Anabaptist, Anglican, Baptist, Calvinist, Evangelical, Holiness, Lutheran, Methodist, and Pentecostal); in the East, Eastern Catholic; Eastern Orthodox; Oriental Orthodox Church of the East (Nestorian); and in Nontrinitarian, Jehovah's Witness; Latter Day Saint; and Oneness Pentecostal.

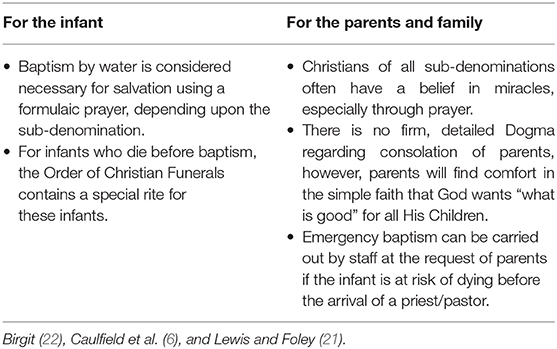

In Christianity, Jesus is considered the savior, and although beliefs vary between sub-denominations, most Christians view illness as a natural process of the body and even as a testing of their faith. While the death of an infant represents profound loss, most Christians view death as being part of the will of God (7). Table 4 provides guidance for clinicians caring for infants of Christian families, especially for both the infant and the parents.

In a qualitative multicenter study, Boss et al. (5) described some parents whose infants had died due to severe prematurity or congenital defects as being reluctant to make any decisions regarding resuscitation. These parents were described as wanting matters “left … in God's hands,” yet typically they were documented to be most likely to “want everything done.” In this study, for most parents, faith, spirituality, and hope have influenced the decision-making process.

Prayer is an important component for Christians, regardless of the sub-denomination, and may be directed to one or all the holy trinity: God, the Holy Spirit, and/or Jesus Christ. Baptism, which is a Christian rite of entry into Christianity, almost always through the use of water, is another important ritual, usually performed near the time of birth. According to Birgit (22), the onus is upon parents to seek baptism if their infant dies at birth or is imminently dying as the unbaptized infant cannot “seek truth” or choose to behave in an “ethical way.” Christians believe that the baptized child who dies will end up in heaven, but there are reasons for hope that, in the presence of God, children who die without baptism will still feel the joy of everlasting life (i.e., enter Heaven) (22).

Caulfield et al. (6) have recommended that, in order to fulfill the needs of families in an emerging multi-faith community, maternity hospitals and neonatal units need to have access to emergency baptism services or other similar “spiritual blessings.” In a study to evaluate trends of infants of Catholic parents baptized over a 15-year period at an Irish maternity hospital, Caulfield et al. (6) reported a gradual decline of emergency baptisms.

Access to emergency baptism services is important, because, in the early stages of grief of parents whose infant had died, 37% of the parents (who were all Christian) said that their religious beliefs were challenged and that they questioned their faith (10). Parents in a study by Hawthorne et al. (10) expressed their anger and betrayal toward God (to whom they had prayed for help) for being cruel and unjust and the perception that they were being punished by His failure to protect their child; 9% said that they had lost their trust in God. While one of the most important early sacraments in Christianity is Baptism (22), it is important for clinicians to be mindful that many Christians may not subscribe to the point of view outlined in the study by Hawthorne et al.

Hinduism

Hinduism, with its origins and traditions dating back more than 4,000 years, is considered the oldest religion in the world. Hinduism is practiced by 15.1% globally and is a broad term that describes many subgroups of the religion, which influence its practice and customs. Most forms of Hinduism are henotheistic, adulating a single deity (Brahman), but other gods and goddesses are still acknowledged by their followers. In the scriptures and wisdom heritages of the Vedic tradition, however, all of them have their individual origins (8). Hinduism, irrespective of tradition, offers a systematic explanation of life and death that most Hindus accept. The term “life” translates to “the atma,” which can be interpreted as the “soul” (8). In Hinduism, achieving a state of Nirvana (or “oneness with God”) is the primary purpose. Similar to Buddhism, disease and illness are considered the result of karmic actions, and death is simply a passage because the atma has no beginning or end (21). Hindus believe in reincarnation, so a newborn is not a “new” creation but a perpetual being continuing its progression of lives in a new body.

In terms of infants born with an LLFD, the Bhagavat Purana (a revered Hindu text) affords personhood to the fetus at 180 days of gestation as the embryo begins to develop awareness and beings to feel pain (8). The Dharmashastras (the treatises of Hinduism) view the termination of pregnancy (the “killing” of a human fetus is referred to as “bhrunahatya”) as a sin; however, in less traditional Hindu families, termination may not be seen this way.

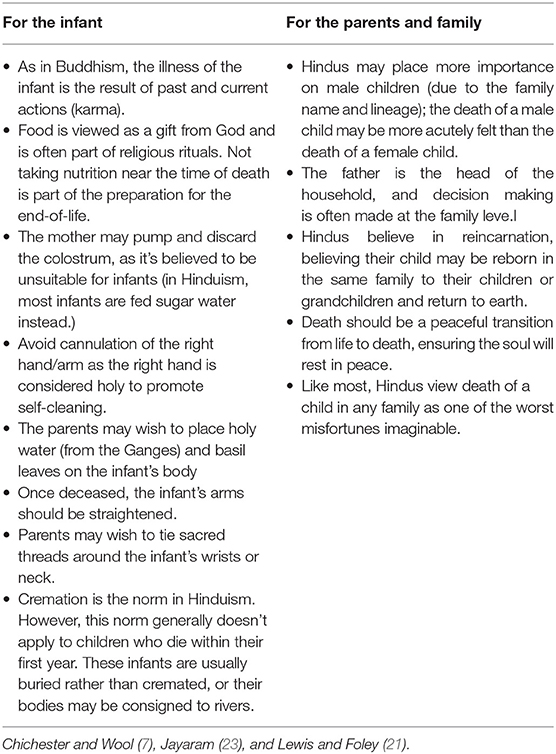

Clinicians should be aware that more importance is placed on the male child in Hinduism, given that they continue the lineage of the family, including the name. Therefore, it is more likely that the death of a male infant will be more acutely felt in traditional Hindu families than the death of a female infant (23). In the Hindu tradition, palliative care is considered appropriate for infants who are not expected to survive. Any interventions that might hasten death are not considered appropriate, and where possible, all active treatments should be ceased and the death of the infant should be allowed to happen in its own time (8). Table 5 provides guidance for clinicians caring for infants of Hindu families, especially for both the infant and the parents.

Judaism

Judaism is practiced by <0.2% of the global population. Judaism is the oldest monotheistic religion, dating back nearly 4,000 years. The followers of Judaism believe in one God who, through ancient prophets, revealed himself. Its primary religious beliefs revolve around a code of ethics with four groupings of Jewish beliefs: reform (largest affiliation [35%] of American Jews), reconstructionist (an evolving civilization of the Jewish people), conservative (“traditional” Judaism outside of North America), and orthodox (adherence to a traditional understanding of Jewish law; this includes Haredi and Hasidic). Jewish clergy are known as Rabbi. Psalms, as the last prayer of confession (vidui), are conducted at the bedside of the person (21).

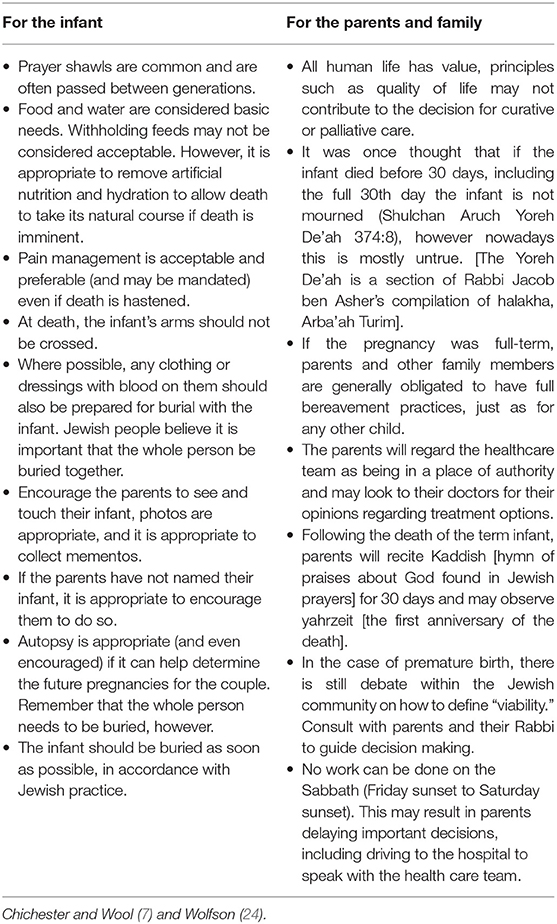

Table 6 provides guidance for caring for infants of Jewish families, especially for both the infant and the parents.

A prematurely born infant is referred to as a “Nefel”: the same word is often applied to an abortus or an infant born with major life-incompatible defects. The word Nefel, in Jewish culture, refers to an infant who lacks sufficient hair and nail growth; is born in the eighth month of pregnancy; and survives for <30 days. Relevant social rules are different for a Nefel in Judaism compared to a well term infant (12).

It was once thought that if the infant dies, up to and including, on the full 30th day, then the infant is not mourned (Shulchan Aruch Yoreh De'ah 374:8); however, nowadays this is mostly untrue. [The Yoreh De'ah is a section of Rabbi Jacob ben Asher's compilation of halakha, Arba'ah Turim]. It has been reported that Jewish parents still feel a keen sense of loss and grief when an infant dies before the thirty-day benchmark (24).

Spiritual considerations for parents

Though used interchangeably, faith and spirituality are different from each other. Spirituality is more difficult to define because there are no common characteristics that were agreed upon. It is a broader concept that each individual defines for themselves (18). Spiritual care is distinctly different from identifying and resolving specific health problems: It is about being present in the journey of “making meaning” at the pivotal times in one's life.

In an explorative study about relevant sense-making activities, whether through prayer and/or meditation, first-time mothers established two key themes to help them deal with the life-threatening illness of their infants: (a) looking for meaning circles and (b) using intuitive/spiritual experiences to find meaning (13). Similarly, Sadeghi et al. (3) found three spiritual themes identified by parents that had lost an infant following an LLFD: a philosophical belief in the forces of the supernatural; the need for the comfort of the soul; and human dignity for the newborn (3).

To help parents make meaning and meet their spiritual needs when faced with perinatal death, the parents should be encouraged to consider how their infant has touched other lives besides their own; this includes other family members, particularly grandparents, who would have had their own hopes and dreams for the child. Raingruber and Milstein (13) propose that parents imagine the waves that circle around just one pebble tossed into a pool and that this enables parents to recognize how the life and/or death of their child form others. Parents will gain an insight into the life and death of their baby by focusing on these waves (13). These simple practices do not require parents to follow a particular religion, and comfort can be found in simple acts of making meaning. It is important to support parents through their loss by providing care that also addresses the spiritual, religious, and, existential needs of the parents and families (2).

In 2017, Hawthorne et al. explored the disparities between gender, race/ethnicity, and religion in the use of spiritual and religious coping strategies by parents after the death of a child. The study found that non-Hispanic black mothers were more likely to use religious coping strategies than non-Hispanic white mothers. Christian parents used more religious coping practices than the other groups, and mothers reported considerably more use of religious and spiritual coping practices than fathers (10). This study concluded that black mothers were more religious than they were spiritual, and the mothers were more spiritual and religious than the fathers in coping with the loss of an infant, providing some guidance to healthcare professionals on how to support bereaved parents of diverse races/ethnicities and religions. It has been identified in Latino women that their religious and spiritual beliefs were found to be intensely comforting. Their combined beliefs helped them to validate the decisions they had made in response to an LLFD. Their spirituality helped them to maintain a sense of optimism even when faced with difficult decisions following complex amniocentesis findings (14).

Cultural Considerations for Parents

Culture refers to the collective deposit of information, experience, opinions, principles, behaviors, meanings, hierarchies, faith, notions of time, responsibilities, spatial relationships, concepts of the world, and material objects and belongings acquired through person and community by a group of people over different periods of time (25).

In 2008, Davies et al. conducted a survey demonstrating that almost 40% of healthcare professionals cited “cultural differences” as a barrier to providing palliative care. This was particularly so among ethnic minorities whose cultures were poorly understood, including Latino, Indian, and Native and African Americans. Cultural gaps extended to language barriers, religious differences, and mistrust of healthcare providers and care of health practitioners who did not have the same racial or cultural context and who did not recognize these differences (26). In a study that explored the challenges for trainee neonatologists, dealing with different cultures and the inability to interact effectively with people of different cultures were identified as significant when the trainee had different faith and religious beliefs to those of the parents and families. The trainees were more likely to respond with anxiety, wariness, and even anger or fear to unknown cultures or unfamiliar cultures when working with parents that are making the end-of-life decisions about their infant (9).

No matter how committed, highly trained, and dedicated the healthcare team is, when caring for parents and their infant with an LLFD, an expert understanding of how families function, spiritually, cross-culturally, and existentially, presents a considerable challenge in PPC.

Conclusions

It is not surprising that families rely on their faith and spirituality in times of crisis to help them make sense of the path to the end of life. This analysis revealed why healthcare practitioners need to become familiar with the definitions of the moral and religious ideas that arise in their clinical field or specialization for parents and families. Regardless of the religious, spiritual, or cultural beliefs, all parents facing the death of their infant due to an LLFD require a compassionate, supportive, and knowledgeable healthcare service. Life and death are momentous occasions in the life cycle, and when the two occur in close proximity, beliefs and religious ceremonies become even more profound. All members of the healthcare team providing care to parents from the moment of the diagnosis through the palliation of to death of the infant require a unique skill set, including the ability to pay attention to, and the knowledge of, religious, spiritual, and cultural needs of the parents.

Author Contributions

VK conceptualized and designed the review, drafted the manuscript, and is solely responsible for data collection and interpretation of the literature data.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1. WHO. WHO Definition of Palliative Care. (2020). Available online at: https://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/ (accessed June 25, 2020).

2. Rosenbaum JL, Smith JR, Zollfrank R. Neonatal end-of-life spiritual support care. J Perinatal Neonatal Nurs. (2011) 25:61–9. doi: 10.1097/JPN.0b013e318209e1d2

3. Sadeghi N, Hasanpour M, Heidarzadeh M, Alamolhoda A, Waldman E. Spiritual needs of families with bereavement and loss of an infant in the neonatal intensive care unit: a qualitative study. J Pain Sympt Manage. (2016) 52:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.12.344

4. Ayed M, Ayed A. Fetal and newborn palliative care in islam-when to be considered. Case Rep Lit Rev. (2018) 2:1–8.

5. Boss RD, Hutton N, Sulpar LJ, West AM, Donohue PK. Values parents apply to decision-making regarding delivery room resuscitation for high-risk newborns. Pediatrics. (2008) 122:583–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1972

6. Caulfield FM, Ihidero OA, Carroll M, Dunworth M, Hunt M, McAuliffe D, et al. Spiritual care in neonatology: analysis of emergency baptisms in an Irish neonatal unit over 15 years. Irish J Med Sci. (2019) 188:607–12. doi: 10.1007/s11845-018-1894-y

7. Chichester M, Wool C. The meaning of food and multicultural implications for perinatal palliative care. Nurs Women's Health. (2015) 19:224–35. doi: 10.1111/1751-486X.12204

8. Das A. Withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment for newborn infants from a Hindu perspective. Early Hum Dev. (2012) 88:87–8. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2011.12.004

9. El Sayed MF, Chan M, McAllister M, Hellmann J. End-of-life care in Toronto neonatal intensive care units: challenges for physician trainees. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. (2013) 98:F528–33. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2012-303000

10. Hawthorne DM, Youngblut JM, Brooten D. Use of spiritual coping strategies by gender, race/ethnicity, and religion at 1 and 3 months after infant's/child's intensive care unit death. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. (2017) 29:591–9. doi: 10.1002/2327-6924.12498

11. Kain VJ. Babies born dying: just bad karma? A discussion paper. J Relig Health. (2014) 53:1753–8. doi: 10.1007/s10943-013-9779-x

12. McGuirl J, Campbell D. Understanding the role of religious views in the discussion about resuscitation at the threshold of viability. J Perinatol. (2016) 36:694–8. doi: 10.1038/jp.2016.104

13. Raingruber B, Milstein J. Searching for circles of meaning and using spiritual experiences to help parents of infants with life-threatening illness cope. J Holistic Nurs. (2007) 25:39–49. doi: 10.1177/0898010106289859

14. Seth SG, Goka T, Harbison A, Hollier L, Peterson S, Ramondetta L, et al. Exploring the role of religiosity and spirituality in amniocentesis decision-making among Latinas. J Genet Couns. (2011) 20:660–73. doi: 10.1007/s10897-011-9378-5

15. Shukla VV, Ayed AK, Ayed MK. Considerations for redirection of care in muslim neonates: issues and recommendations. Kuwait Med J. (2018) 50:417–21.

16. Stark R. The Triumph of Faith: Why the World Is More Religious Than Ever. Wilmington, DE: ISI Books (2015).

17. Lüddeckens D, Schrimpf M. Medicine, Religion, Spirituality: Global Perspectives on Traditional, Complementary, and Alternative Healing. Bielefeld, NC: Transcript (2018).

18. Koenig HG, McCullough ME, Larson DB. Handbook of Religion and Health. New York, NY; Oxford: Oxford University Press (2001).

19. Leung TN, Ching Chau MM, Chang JJ, Leung TY, Fung TY, Lau TK. Attitudes towards termination of pregnancy among Hong Kong Chinese women attending prenatal diagnosis counselling clinic. Prenat Diagn. (2004) 24:546–51. doi: 10.1002/pd.950

20. Tsai GJ, Cameron CA, Czerwinski JL, Mendez-Figueroa H, Peterson SK, Noblin SJ. Attitudes towards prenatal genetic counseling, prenatal genetic testing, and termination of pregnancy among southeast and east asian women in the United States. J Genet Couns. (2017) 26:1041–58. doi: 10.1007/s10897-017-0084-9

21. Lewis P, Foley D. Assessing spirituality and religious practices. In: Health Assessment in Nursing Australia and New Zealand Edition. 2 ed. Wolters Kluwer Health (Sydney) (2014). p. 194–220.

22. Birgit J. What Happens to Babies Who Die Before Baptism? (2018). Available online at: http://catholiclifeinourtimescom/babies-die-baptism/ (accessed December 26, 2020).

23. Jayaram V. Hinduism - Coping With the Death of a Child in the Family. (2020). Available online at: https://www.hinduwebsite.com/random/chidrendeath.asp (accessed June 26, 2020).

24. Wolfson R. Part 2: neonatal death. In: Federation of Jewish Men's Clubs, editor. A Time to Mourn, a Time to Comfort: A Guide to Jewish Bereavement (The Art of Jewish Living). 2nd ed. Jewish Lights (Woodstock) (2005).

25. Hofstede GH, Hofstede GJ, Minkov M. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind: Intercultural Cooperation and Its Importance for Survival. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill (2010).

Keywords: perinatal palliative care, parents, religious needs, cultural needs, spiritual needs

Citation: Kain VJ (2021) Perinatal Palliative Care: Cultural, Spiritual, and Religious Considerations for Parents—What Clinicians Need to Know. Front. Pediatr. 9:597519. doi: 10.3389/fped.2021.597519

Received: 21 August 2020; Accepted: 12 February 2021;

Published: 30 March 2021.

Edited by:

Brian S. Carter, Children's Mercy Hospital, United StatesReviewed by:

Christopher Collura, Mayo Clinic, United StatesSteven Leuthner, Medical College of Wisconsin, United States

Copyright © 2021 Kain. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Victoria J. Kain, di5rYWluQGdyaWZmaXRoLmVkdS5hdQ==

Victoria J. Kain

Victoria J. Kain