- 1Department of Pediatrics, Division of Children's Health Services Research, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN, United States

- 2Indiana Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute (CTSI), Research Jam, Indianapolis, IN, United States

- 3Kraft Center for Community Health, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, United States

- 4Department of Nutrition, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, United States

- 5Department of Pediatrics, Center for Pediatric and Adolescent Comparative and Effectiveness Research, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN, United States

Objective: Pediatricians are well positioned to discuss early life obesity risk, but optimal methods of communication should account for parent preferences. To help inform communication strategies focused on early life obesity prevention, we employed human-centered design methodologies to identify parental perceptions, concerns, beliefs, and communication preferences about early life obesity risk.

Methods: We conducted a series of virtual human-centered design research sessions with 31 parents of infants <24 months old. Parents were recruited with a human intelligence task posted on Amazon's Mechanical Turk, via social media postings on Facebook and Reddit, and from local community organizations. Human-centered design techniques included individual short-answer activities derived from personas and empathy maps as well as group discussion.

Results: Parents welcomed a conversation about infant weight and obesity risk, but concerns about health were expressed in relation to the future. Tone, context, and collaboration emerged as important for obesity prevention discussions. Framing the conversation around healthy changes for the entire family to prevent adverse impacts of excess weight may be more effective than focusing on weight loss.

Conclusions: Our human-centered design approach provides a model for developing and refining messages and materials aimed at increasing parent/provider communication about early life obesity prevention. Motivating families to engage in obesity prevention may require pediatricians and other health professionals to frame the conversation within the context of other developmental milestones, involve the entire family, and provide practical strategies for behavioral change.

Introduction

Overweight and obesity now affect over 41 million children under the age of 5 (1), an epidemic that is apparent worldwide (2, 3). Childhood obesity negatively impacts health (4–11) and is known to track along the life course (12, 13), increasing the risk for many related adult diseases (14). As such, prevention is key, with early life holding the most promise for addressing the obesity epidemic (15).

Pediatricians can help curb the obesity epidemic through screening, communication, and anticipatory guidance. Beginning at age two, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends measuring BMI and screening for obesity-related comorbidities as part of routine primary care, but research indicates that parents (16) and providers (17, 18) often avoid the subject. In addition to time and resource constraints, providers report feeling uncomfortable about raising the issue, uncertainty about how best to communicate with families about weight, and concern about how families will respond (19). Obesity counseling in infancy may be even more challenging – despite evidence of modifiable risk factors (14) – because parents may be unaware of the importance of prevention and because there is no standard recommendation for treatment of overweight infants.

To inform the development of a communication strategy focused on helping pediatricians and parents of young children engage in conversations about obesity prevention, we employed a human-centered design (HCD) approach to gain a richer qualitative understanding of parents' perceptions, concerns, beliefs and communication preferences about early life obesity risk. HCD, which is increasingly being used within healthcare, is a generative, iterative process that includes: (1) insight, or developing an understanding of stakeholders and their needs; (2) ideation, or exploring options for “what could be”; and (3) implementation, or executing the intervention and testing prototypes (20). Additional core principals of HCD include developing deep empathy with end users and acknowledging lived experience as a credible form of expertise (21). As such, HCD is particularly effective in eliciting deep insights and creating solutions compatible with end stakeholders' needs (22) and may help broaden our understanding of factors not addressed by traditional qualitative approaches that tend to engage with participants in a consultative, rather than a collaborative manner (23). HCD shares many theoretical underpinnings of social behavioral research and implementation science; however, while these traditional approaches are useful to identify determinants of behavior change and evaluate how well a design solution works, HCD focuses on creating approaches and delivering solutions to problems based on a concerted effort to understand the specific needs and perspectives of users (24). HCD allows for iterative development and refinement of a customized and tailored solution, thereby increase the likelihood of user engagement. As such, HCD can help “move the needle” and galvanize new thinking around potential solutions intransigent problems (25). Previous work has shown that applying user-centered design can drive progress for health-related behavioral interventions (26).

HCD has been successfully used to create tools for enhancing communication interventions (27) but to our knowledge, has not been applied to elicit parent perspectives of early life obesity risk. We hypothesized that a HCD approach could identify key views of obesity risk and parental preferences regarding risk communication for young children.

Methods

Study Design

We collaborated with the Indiana Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute's Patient Engagement Core (28), Research Jam (RJ), a multi-disciplinary team of trained HCD experts and health services researchers with experience applying HCD techniques to health services research through a combination of qualitative research and design research methodologies (29–31). Study protocols were approved by the Indiana University Institutional Review Board.

We (CM, LP, and ERC) conducted a series of online HCD activities with parents of children <24 months of age that focused on exploring underlying attitudes, beliefs, and communication preferences related to early life obesity. All activities took place virtually on FocusVision's Revelation (32) a user-friendly, online qualitative research platform that allows researchers to craft activities for participants to complete using their personal computer or smart phone. Using social media-style interactions, Revelation strives to engage participants in activity-based research, enabling them to share their thoughts, feelings, photographs and video, all of which deliver rich, deep insights into their lives.

Parent Recruitment

RJ recruited parents between July and December 2020 via: (1) a Human Intelligence Task (HIT) posted on MTurk, a large, online crowdsourcing marketplace frequently used for survey studies (33); (2) social media; and (3) local professional organizations our University has partnered with in previous work.

Amazon's Mechanical Turk (MTurk) identifies online “workers” who meet specific, predefined criteria and alerts them of HITs to complete for compensation. Workers read brief descriptions and preview the tasks before working on them. MTurk allows researchers to imbed prescreening questions that constrain who can see and complete particular HITs. We programed our HIT to reach workers who: (1) were at least 18 years old; (2) lived in the US; (3) had least 1 child <24 months of age; and (4) were able to read and write in English. Parents who completed the survey were reimbursed through Amazon's pre-determined fee schedule.

We also posted study information on various social media platforms, including Facebook (parenting groups, RJ and Indiana CTSI pages), and on the sub-Reddit r/parents.

Finally, we shared a study flier with local community organizations who serve parents, including the IUPUI Center for Young Children, Tabernacle Presbyterian Church in Indianapolis, the local office of the Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) Program, the Indiana State Department of Health, and Indiana CTSI coalitions.

Through an electronic link or QR code, we directed parents to a RedCap page containing an overview of study activities. Interested parents were screened for eligibility, provided an electronic consent, and completed a brief demographic survey. We selected a subset of these parents to ensure diversity of child age, income, and mother/father role on a first come, first serve basis. We then emailed these parents full study details, instructions, and a link to FocusVision's Revelation webpage.

Human-Centered Design Activities

Parents then engaged in a series of online activities designed by RJ focused on perceptions of parenting advice, health in infancy, obesity prevention, and communication preferences. To facilitate discussion, we grouped parents based on child age (<12 months or 13–24 months old) and household income (below or above $50,000). Activities consisted of three open-ended questions focused on parenting and obesity, and three personas/empathy exercises followed by discussion. These activities were designed based loosely on a health-belief model (34) which assumes that parental involvement in childhood obesity prevention is partly determined by their perception of the likelihood, seriousness, and potential consequences of their child's obesity risk. Parents performed activities asynchronously throughout a week-long engagement period. We monitored their progress, asked follow-up questions, and sent reminders to complete the activities when needed. Parents spent approximately 1.5 h to complete the activities and were compensated $50. Revelation activities took place during the spring of 2021.

Open-Ended Questions

The open-ended questions were completed individually; the first two questions were shared so others in the group could respond and discuss. The questions were developed to gain an understanding of perceptions around health and healthy behaviors for infants and toddlers (“What do you think is most important for making sure your baby is healthy?”); to understand what kinds of unsolicited advice parents get in their daily lives, how the advice is received, and factors impacting how advice was received (“Tell a story about a time you were given parenting advice that you didn't ask for. What was the advice and what was your reaction?”); and to elicit underlying attitudes around obesity (“Define obesity in your own words. What other words do you associate with obesity?”).

Personas/Empathy Exercises

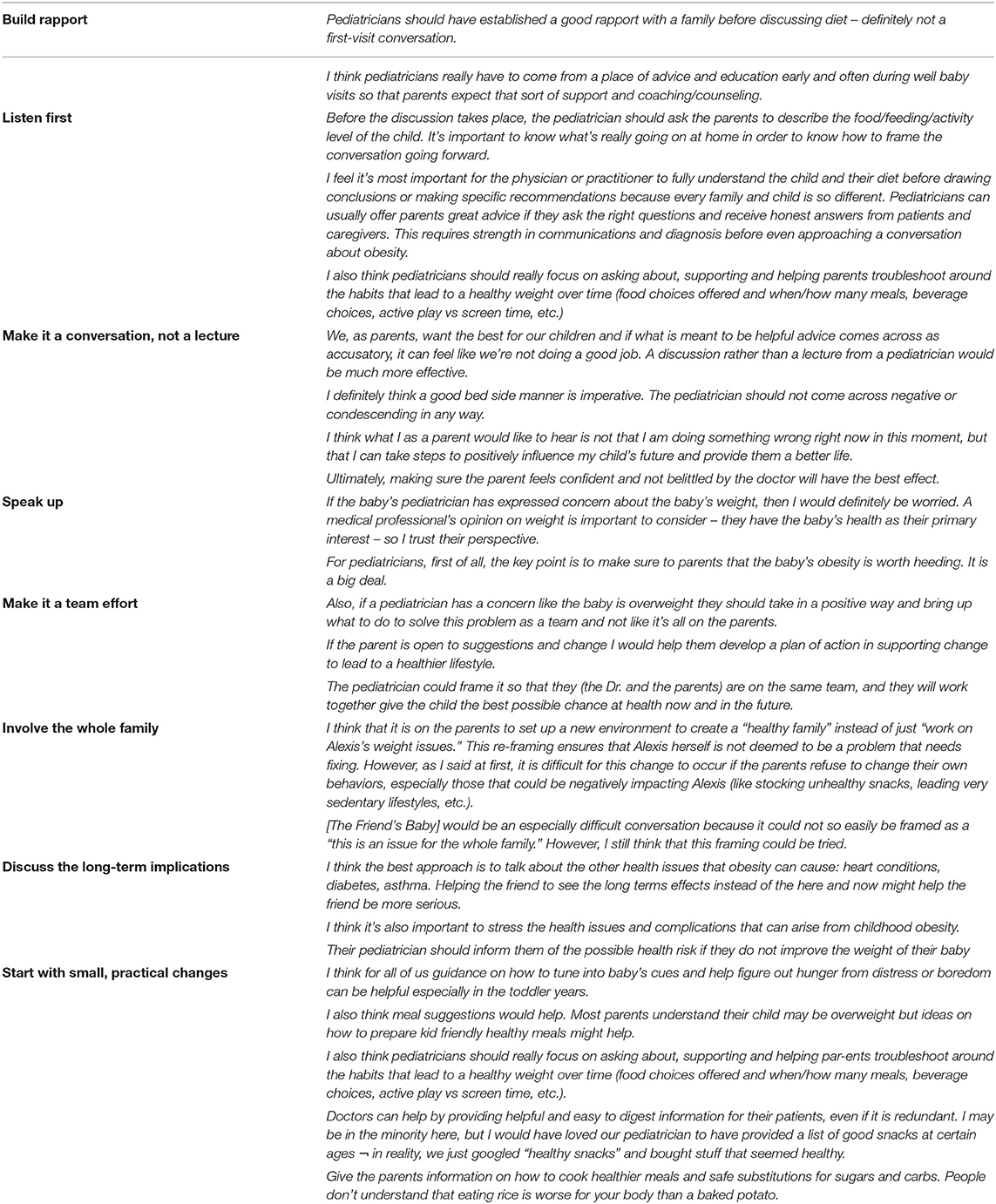

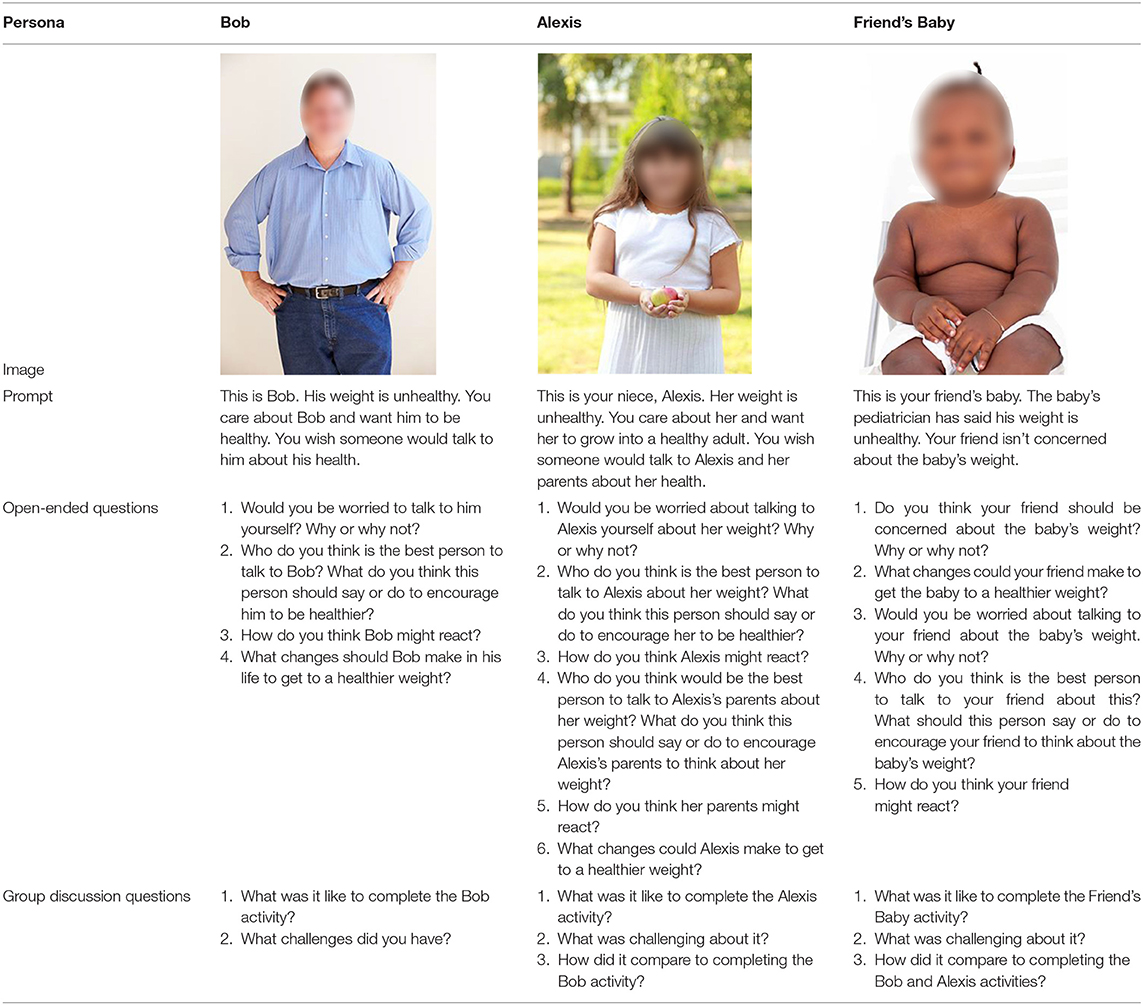

Personas (35) (e.g., fictitious representations of a person used to capture important characteristics and build empathy) and empathy maps (36) (e.g., a structured tool used to build empathy for an individual by thinking about what they say, think, feel, and do in a particular situation) are techniques used in HCD to help designers build empathy with the “customer” for whom they are designing. We developed three individual persona and empathy map exercises within Revelation that explored parents' beliefs and communication preferences about obesity and overweight at different periods in the life course. Each persona displayed a stock image of someone with unhealthy weight, an exercise prompt, and a series of open-ended questions for parents to complete on their own time. The subject of the persona became increasingly younger in each series, such that the final persona was focused on a baby with an unhealthy weight. Specific components of the activities are shown in Table 1. Parents then convened as a group to reflect on the activity.

Table 1. Human-centered design activities completed in revelation: persona and empathy map activities, discussion prompts, and group discussion questions.

Data Analysis

Two members of RJ independently coded responses from four parents (one per group) as well as all four Friend's Baby discussions. The four parents were chosen because they had a high completion rate and thorough answers. The coders allowed codes to emerge from the data and then met to refine their coding structures. The coders then divided the remaining discussions and responses and coded them using the final coding structure.

Results

Session Participation

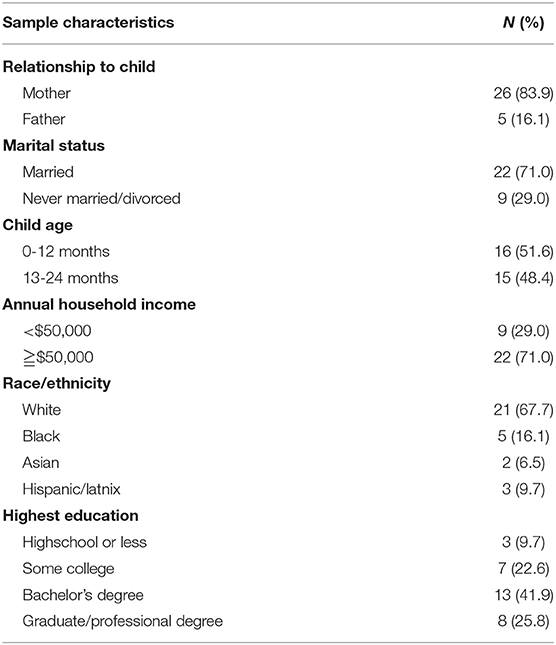

From a pool of 163 parents who consented to the study, we invited 63 to participate in Revelation after excluding invalid and incomplete responses; 31 participated and 27 (87.1%) completed all of the activities (Table 2).

Session Findings

Parental Views About Obesity and Obesity Risk

Seven overarching themes emerged from the persona/empathy map exercises. Table 3 presents additional statements from parents.

Table 3. Parental views about obesity and obesity risk in the first 1,000 days: additional statements from the persona/empathy map activities.

Perception That Obesity Is More Than Just About Weight

A majority of parents defined obesity as having a high weight for length in addition to associated health problems or negative impacts to quality of life. They were less concerned about body mass index alone.

- [Obesity is] the point when it's no longer just carrying an extra 30-50 pounds [but] when it starts to seriously hinder a person's quality of life and health.

- I think it's possible to be technically obese by the numbers (though I believe that BMI is outdated) and still be as healthy (or healthier) than someone of average weight.

Anxiety and Stigma

A common sentiment expressed by parents during the Bob Activity was anxiety about labeling:

- The questions made me have to assume things about Bob based on the way he looks, so I didn't want to assume.

Societal stigma was apparent in the discussions. Parents were concerned that conversations about weight would harm Bob and Alexis and were especially hesitant to discuss Alexis's weight for fear of causing trauma.

- Even though I am worried about [Bob's] health, he might feel like I'm attacking his appearance or even his character because being obese is viewed by society as an indicator of ugliness and laziness.

- No one (even a family member) should be sitting down with Alexis and talking about her weight. There are just already too many toxic messages about young girls and their bodies/weight. – I would not want to set her up for future eating disorders or something else.

The Belief That Obesity Is More Impactful at Older Ages

Parents did not challenge the idea that a conversation around infant weight was appropriate, but were less concerned about obesity risk in early life than during the Bob and Alexis activities. Parents viewed early habits as easier to change.

- If there is a noticeable problem by age 3 or 4 then an intervention might be necessary.

- I did find myself not concerned whatsoever with the weight of the baby, slightly concerned with the weight of Alexis, and most concerned with the weight of Bob.

Pediatricians Are Important Sources of Health Information

Parents expressed during the Friend's Baby Activity that they would take weight-related concerns by their child's pediatrician seriously.

- If the baby's pediatrician has expressed concern about the baby's weight, then I would definitely be worried. A medical professional's opinion on weight is important to consider – they have the baby's health as their primary interest – so I trust their perspective.

Uncertainty About Risk and Management of Obesity in Infancy Compared to Older Ages

When discussing whether infants could have overweight, parents believed that infant weight fluctuations are normal and that most infants grow out of weight issues.

- This baby may be overweight, but as long as it fluctuates and he is developing on track, that seems like the MOST important part. Maybe down the line if the baby seems to be going up and up on the weight charts it could be looked at as a more significant trend and not just a spurt of insignificant weight increase.

Some parents expressed that “baby fat” is not concerning, or was a sign of a healthy baby. They expressed that once a baby begins moving more, the weight would naturally drop off.

- I don't think I would be overly concerned about the baby having a bigger weight in the beginning. So many babies lose their “baby fat” once they become mobile and really get into walking, climbing, jumping, and dancing.

Parents were confident of the causes and long-term impacts of obesity during the Bob and Alexis activities, and had opinions and recommendations for lifestyle changes that could improve their health, they were less knowledgeable during the Friend's Baby activity.

- I am less clear on what the healthy standards are for decreasing weight in babies, so I don't feel qualified to give advice in this area.

More Concern About Developmental Delays and Underweight Than Overweight and Obesity

Similar to findings from the Bob Activity, parents expressed that infant weight itself is not concerning unless there are associated health problems, and placed a higher value on attributes such as childhood happiness: most importantly, we want him to be healthy and feel good and meeting developmental milestones. They expressed more concern about having a baby with underweight than with overweight.

- If it were my child, I would start to be concerned if my baby was healthy and also seemed to be abnormally fixated on food or if they were missing gross motor milestones because it was hard to move themselves around.

- When I think about babies and weight, my mind initially goes to a baby not gaining enough weight; I do not ever [think about] a baby being overweight.

Parents Know Best

Parents shared many examples of unsolicited advice they had received about their child's diet or eating habits, but emphasized that they knew best when it comes to their own children.

- Every child is different and you just have to find out what works for yours. I don't take offense when people try to give me advice because maybe it's what worked for them but I also take into account that I know my children better than anyone.

Parental Preferences Regarding Early Life Obesity Risk Communication

Parents were also asked about their preferences in a health professional approach to obesity risk communication. Eight key themes emerged from their answers (Table 4).

Parents repeatedly expressed that if their child's pediatrician was concerned about their child's weight, they would also be concerned (Speak up), but they preferred to have pediatricians build a strong relationship with them prior to discussing overweight in their infants (Build rapport). They also suggested that health professionals ask about the family's current habits before giving advice (Listen first). During the Bob and Alexis activities, the parents suggested that this approach could help identify barriers to healthy lifestyle changes (e.g., food insecurity or underlying medical issues), enabling targeted advice. To avoid defensive responses, parents recommended approaching the issue as a conversation rather than a lecture, and using language to help them feel encouraged and empowered, not judged (Make it a conversation, not a lecture).

Parents also suggested pediatricians frame conversations as a team effort between themselves and the parents, in part by offering direct support (Make it a team effort). Along those lines, parents suggested having family members join in the healthy lifestyle changes that Bob and Alexis were attempting (Involve the whole family). In this way, they could be supportive of the person needing to lose weight and also create a healthy family context within which to make these changes. Parents thought this would also be a better approach because it focuses on what “we” could do to be healthy instead of what “you” needed to do.

In terms of specific content, parents recommended framing the conversation around the long-term health implications of obesity to help them understand the seriousness of the issue (Discuss the long-term implications of unhealthy weight). Parents also agreed that habits were easier to change at younger ages and believed that small changes could make a big difference (Start with small, practical changes so parents do not feel overwhelmed). They identified specific areas of need, including resources to recognize fullness cues, ideas for active play, and healthy diet recommendations.

Discussion

Using an online research tool called Revelation (32) and a HCD approach, we engaged parents of children <2 years of age in discussions around parenting, obesity, and communication about obesity and health. Our final sample included a diverse sample of 31 parents recruited based on household income and caregiving role. Results highlight the translational potential of using HCD to inform the design of a communication strategy that helps motivate families to engage in early life obesity prevention.

Our findings reinforce prior studies suggesting that parents are often not concerned about weight in infancy and tend to believe that children “grow out” of weight problems (37). Although parents welcomed a conversation about infant weight and obesity risk, there was a strong belief that BMI is not a useful measure for overweight and obesity in the absence of related health problems. Few parents perceived excess weight in infancy as an issue causing immediate health risks; rather, they were most concerned about infant weight when they perceived it to affect other aspects of development. Other research has similarly found that parents' immediate concerns relating to overweight were in relation to initiation of walking and other developmental milestones (38). Therefore, framing weight-related conversations in this context, as opposed to focusing on obesity or measures of weight-for-length, seems most likely to influence parental receptiveness to engage in preventative interventions.

At the same time, parents in our study overwhelmingly agreed that healthy habits are easiest to achieve earlier in life. While they were somewhat knowledgeable about obesity prevention and risk in older children and adults, our study also revealed gaps in knowledge regarding which habits in infancy lead to unhealthy weight. There were gaps in parental understanding of infant feeding and mobility, specifically regarding how to recognize fullness, active play ideas for different ages, as well as age-appropriate healthy eating. Parents also described being inundated with unsolicited advice about their child's diet or eating habits, causing uncertainty or anxiety.

We also found that parents of infants were open to obesity prevention intervention and guidance. When asked how they would prefer to receive anticipatory guidance about obesity risk during infancy, parents overwhelmingly identified pediatricians as the best, most trusted source of health information. This mirrors research in older populations (39). When prompted to think about how pediatricians should frame the conversation, it was clear that early life obesity is a sensitive topic. Our findings suggest that pediatricians initiate anticipatory guidance around obesity prevention at birth, building a relationship with parents over time, and focus conversations more on making practical changes to build healthy habits early than on obesity prevention per se. For example, while parents resisted the idea of “dieting” for their infants, they recognized the importance of nutrition and expressed interest in having specific, focused recommendations for healthy meals and snacks. Unlike most existing obesity prevention efforts that target mothers (40, 41), they recommended that information about how to make healthy changes engage non-maternal caregivers (e.g., fathers).

Parents expect providers to be explicit when there is a weight concern, but they also emphasized a preference for positivity and encouragement their approach. Parents discussed feeling defensive, personally attacked, hurt, embarrassed, offended, and upset by unsolicited advice about parenting and suggested that physicians be mindful of these possible reactions when providing anticipatory guidance about obesity risk. Our findings also suggest that tailoring interventions to the child's age, gender, and specific family dynamics is critical, as noted by others (42).

Despite the importance of obesity prevention, interventions delivered to infants tend to report low levels of parental engagement, as well as modest effects on children's weight outcomes (43–45). One key step to engaging parents in preventive efforts is improving their recognition of obesity risk (46, 47). However, evidence shows that mothers underestimate their infants' overweight (18, 38, 48), are uncertain whether infants are susceptible to being or becoming overweight (18), and may not be aware of risk factors during infancy that are important for obesity prevention (18). In other research, parents who have inaccurate perceptions of their child's obesity risk are more likely to ignore appropriate health messages (49). Some evidence further indicates that attempts by pediatricians to correct parents' misperceptions about child weight may damage rapport and ultimately fail if such messages fail to account for parent preferences (49). The findings from this study may help inform efforts to communicate obesity risk in the pediatric setting, a key step to developing effective interventions.

Limitations

There were several limitations to this study. One limitation was the low numbers of fathers we were able to recruit. Further research should identify preferences and needs unique to fathers. We were not able to recruit the desired number of parents with incomes below $50,000 perhaps due to the online recruitment and engagement methods used. This may have limited the feedback and perspectives of those most affected by obesity and its comorbidities. We grouped participants by income level and child age to facilitate discussion, but participants' views were more homogenous than expected. Selection bias may have played a role, but we did not collect information on eligible parents who did not consent to participate. COVID-related stressors (e.g., food insecurity or feeding practices) (50) influenced parental responses, but we did not ask about this. Finally, our HCD approach, which provides a framework to understand the communication preferences and experiences of parents who are the target of obesity-prevention efforts, does not mimic traditional qualitative research approaches. The design methods we employed were primarily oriented toward generative solutions of defined problems within a small sample, rather than toward theory and hypotheses building as expected from more traditional research methods.

Implications for Research and Practice

Implications for practice: Nonetheless, our HCD approach with the insight of parents successfully identified their perceptions, attitudes, and beliefs about risk of obesity in their young children. How we effectively communicate around obesity is an important topic as treatment paradigms shift more upstream toward prevention; our findings may be helpful in creating communication strategies to help parents and providers engage in these discussions. We learned that parents were receptive to prevention but were uncertain about early life obesity management, highlighting an opportunity for education. Encouragingly, parents were confident in their ability to make good choices for their children and, when uncertain, looked to their pediatrician for health advice. Our findings demonstrate the importance of a non-judgmental communication approach. Discussions should frame the conversation within the context of other developmental milestones, involve the entire family, and provide practical strategies for behavioral change.

Implications for research: Our findings support Matheson's et al. (51) call for design methodologies as research tools for chronic disease prevention. HCD, which provides a framework by which to understand the needs of stakeholders, may ultimately improve uptake, acceptability and usability of early life obesity interventions by ensuring that parents remain at the center of prevention efforts.

In conclusion, the findings of this study highlight important views of obesity risk and parental preferences regarding communication of risk for young infants. Our use of human-centered design releveled important opportunities to develop and refine messages and materials aimed at increasing parent/provider communication about early life obesity prevention.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Indiana University Institutional Review Board. The Ethics Committee waived the requirement of written informed consent for participation.

Author Contributions

EC contributed to the conception and design of the study and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. CM and LP contributed to the design of the study, performed the analysis, and interpreted the results. ET, SW, and AC contributed to manuscript revision. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported in part by NIH Grants K01DK114383 and K24DK10598. Research Jam: Indiana Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute's Patient Engagement Core (PEC) is supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Clinical and Translational Sciences Award [UL1TR002529]. No funder or sponsor had a role in the design and conduct of the study, collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript, or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. World Health Organization Comission on Ending Childhood Obesity. Report of the Comission on Ending Childhood Obesity. Geneva (2016).

2. Friedrich M. Global obesity epidemic worsening. Jama. (2017) 318: 603. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.10693

3. Collaborators GO. Health effects of overweight and obesity in 195 countries over 25 years. N Engl J Med. (2017) 377:13–27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1614362

4. Freedman DS, Khan LK, Dietz WH, Srinivasan SR, Berenson GS. Relationship of childhood obesity to coronary heart disease risk factors in adulthood: the Bogalusa Heart Study. Pediatrics. (2001) 108:712–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.3.712

5. Must A, Strauss RS. Risks and consequences of childhood and adolescent obesity. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. (1999) 23 (Suppl 2):S2-11. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800852

6. Dietz WH. Overweight and precursors of type 2 diabetes mellitus in children and adolescents. J Pediatr. (2001) 138:453–4. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2001.113635

7. Taveras EM, Rifas-Shiman SL, Camargo CA, Jr., et al. Higher adiposity in infancy associated with recurrent wheeze in a prospective cohort of children. J Allerg Clin Immunol. (2008) 121:1161–66 e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.03.021

8. Franks PW, Hanson RL, Knowler WC, Sievers ML, Bennett PH, Looker HC. Childhood obesity, other cardiovascular risk factors, and premature death. N Engl J Med. (2010) 362:485–93. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0904130

9. Biro FM, Wien M. Childhood obesity and adult morbidities. Am J Clin Nutr. (2010) 91:1499S−1505S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2010.28701B

10. Sinha R, Fisch G, Teague B, et al. Prevalence of impaired glucose tolerance among children and adolescents with marked obesity. N Engl J Med. (2002) 346:802–10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012578

11. Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity among adults and youth: United States, 2011-2014. NCHS Data Brief. (2015) 219:1–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.732

12. Whitaker RC, Wright JA, Pepe MS, Seidel KD, Dietz WH. Predicting obesity in young adulthood from childhood and parental obesity. N Engl J Med. (1997) 337:869–73. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199709253371301

13. Serdula MK, Ivery D, Coates RJ, Freedman DS, Williamson DF, Byers T. Do obese children become obese adults? A review of the literature. PrevMed. (1993) 22:167–77. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1993.1014

14. Baidal JAW, Locks LM, Cheng ER, Blake-Lamb TL, Perkins ME, Taveras EM. Risk factors for childhood obesity in the first 1,000 days: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. (2016) 50:761–79. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.11.012

15. Lumeng JC, Taveras EM, Birch L, Yanovski SZ. Prevention of obesity in infancy and early childhood: a National Institutes of Health workshop. JAMA Pediatr. (2015) 169:484–90. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.3554

16. Gillespie J, Midmore C, Hoeflich J, Ness C, Ballard P, Stewart L. Parents as the start of the solution: a social marketing approach to understanding triggers and barriers to entering a childhood weight management service. J Hum Nutr Diet. (2015) 28:83–92. doi: 10.1111/jhn.12237

17. Huang TT, Borowski LA, Liu B, et al. Pediatricians' and family physicians' weight-related care of children in the U. S. Am J Prev Med. (2011) 41:24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.03.016

18. Dinkel D, Snyder K, Kyvelidou A, Molfese V. He's just content to sit: a qualitative study of mothers' perceptions of infant obesity and physical activity. BMC Public Health. (2017) 17:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4503-5

19. Abdin S, Heath G, Welch RK. Health professionals' views and experiences of discussing weight with children and their families: a systematic review of qualitative research. Child Care Health Dev. (2021) 47:562–74. doi: 10.1111/cch.12854

20. Chen E, Leos C, Kowitt SD, Moracco KE. Enhancing community-based participatory research through human-centered design strategies. Health Promot Pract. (2020) 21:37–48. doi: 10.1177/1524839919850557

22. Hassi L, Laakso M. Making sense of design thinking. IDBM papers vol 1. International Design Business Management Program, Aalto University (2011). p. 50-62.

23. Giacomin J. What is human centred design? Des. (2014) 17:606–23. doi: 10.2752/175630614X14056185480186

24. Noël G, Luig T, Heatherington M, Campbell-Scherer D. Developing tools to support patients and healthcare providers when in conversation about obesity: the 5As team program. Inf Des J. (2018) 24:131–50. doi: 10.1075/idj.00004.noe

25. Tolley E. Traditional Socio-Behavioral Research and Human-Centered Design: Similarities, Unique Contributions and Synergies. Durham: FHI (2017). p. 360.

26. Graham AK, Munson SA, Reddy M, et al. Integrating user-centered design and behavioral science to design a mobile intervention for obesity and binge eating: mixed methods analysis. JMIR Form Res. (2021) 5:e23809. doi: 10.2196/23809

27. Abedini NC, Merel SE, Hicks KG, et al. Applying Human-Centered Design to Refinement of the Jumpstart Guide, a Clinician- and Patient-Facing Goals-of-Care Discussion Priming Tool. J Pain Symptom Manag. (2021) 62:1283–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2021.06.012

28. What is Research Jam. Available online at: https://researchjam.org (accessed October 15, 2021).

29. Sanematsu H, Wiehe S. Learning to look: design in health services research. Touchpoint. (2014):TP06-2P82.

30. Sanematsu H, Wiehe S. How do you do? Design research methods and the “hows” of community based participatory research. In: McTavis L, Brett-MacLean P, eds. Insight 2: Engaging the health humanities. University of Alberta Department of Art and Design (2013). Available online at: http://www.insight2.healthhumanities.ca/publication/InSight2_Publication.pdf

31. Sanematsu H. 53. Fun with Facebook: the impact of focus groups on the development of awareness campaigns for adolescent health J Adolesc Health. (2011) 48:S44–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.11.099

32. FocusVision Revelation Online Qualitative Research Platform (2020). https://www.focusvision.com/products/qualitative-research-revelation/ (accessed April 21, 2020)

33. Mason W, Suri S. Conducting behavioral research on Amazon's mechanical turk. Behav Res Methods Mar. (2012) 44:1–23. doi: 10.3758/s13428-011-0124-6

34. Janz NK, Becker MH. The health belief model: a decade later. Health Educ Q. (1984) 11:1–47. doi: 10.1177/109019818401100101

35. Miaskiewicz T, Kozar KA. Personas and user-centered design: how can personas benefit product design processes? Des Stud. (2011) 32:417–30. doi: 10.1016/j.destud.2011.03.003

36. Gray D, Brown S, Macanufo J. Gamestorming: A playbook for innovators, rulebreakers, and changemakers. O'Reilly Media, Inc. (2010).

37. Lee JM, Lim S, Zoellner J, et al. Don't children grow out of their obesity? Weight transitions in early childhood. Clin Pediatr. (2010) 49:466–9. doi: 10.1177/0009922809356466

38. Bentley F, Swift JA, Cook R, Redsell SA. “I would rather be told than not know” - A qualitative study exploring parental views on identifying the future risk of childhood overweight and obesity during infancy. BMC Public Health. (2017) 17:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4684-y

39. Eneli IU, Kalogiros ID, McDonald KA, Todem D. Parental preferences on addressing weight-related issues in children. Clin Pediatr. (2007) 46:612–8. doi: 10.1177/0009922807299941

40. Davison KK, Gicevic S, Aftosmes-Tobio A, et al. Fathers' representation in observational studies on parenting and childhood obesity: a systematic review and content analysis. Am J Public Health. (2016) 106:e14–21. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303391a

41. Butler ÉM, Fangupo LJ, Cutfield WS, Taylor RW. Systematic review of randomised controlled trials to improve dietary intake for the prevention of obesity in infants aged 0–24 months. Obes Rev. (2021) 22:e13110. doi: 10.1111/obr.13110

42. Brown CL, Perrin EM. Obesity prevention and treatment in primary care. Acad Pediatr. (2018) 18:736–45. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2018.05.004

43. Rossiter C, Cheng H, Appleton J, Campbell KJ, Denney-Wilson E. Addressing obesity in the first days in high risk infants: systematic review. Matern Child Nutr. (2021) 17:e13178. doi: 10.1111/mcn.13178

44. Narzisi K, Simons J. Interventions that prevent or reduce obesity in children from birth to five years of age: a systematic review. J Child Health Care. (2020) 25:320–34. doi: 10.1177/1367493520917863

45. Askie LM, Espinoza D, Martin A, et al. Interventions commenced by early infancy to prevent childhood obesity—The EPOCH Collaboration: an individual participant data prospective meta-analysis of four randomized controlled trials. Pediatr Obes. (2020) 15:e12618. doi: 10.1111/ijpo.12618

46. Mareno N. Parental perception of child weight: a concept analysis. J Adv Nurs. (2014) 70:34–45. doi: 10.1111/jan.12143

47. Rhee KE, DeLago CW, Arscott-Mills T, Mehta SD, Davis RK. Factors associated with parental readiness to make changes for overweight children. Pediatrics. (2005) 116:E94–E101. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2479

48. Brown CL, Skinner AC, Yin HS, et al. Parental perceptions of weight during the first year of life. Acad Pediatr. (2016) 16:558–64. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2016.03.005

49. Pasch LA, Penilla C, Tschann JM, et al. Preferred child body size and parental underestimation of child weight in Mexican-American families. Matern Child Health J. (2016) 20:1842–8. doi: 10.1007/s10995-016-1987-z

50. Adams EL, Caccavale LJ, Smith D, Bean MK. Food insecurity, the home food environment, and parent feeding practices in the era of COVID-19. Obesity. (2020) 28:2056–63. doi: 10.1002/oby.22996

Keywords: obesity prevention, parents, human-centered design (HCD), communication, early life

Citation: Cheng ER, Moore C, Parks L, Taveras EM, Wiehe SE and Carroll AE (2022) Communicating Risk for Obesity in Early Life: Engaging Parents Using Human-Centered Design Methodologies. Front. Pediatr. 10:915231. doi: 10.3389/fped.2022.915231

Received: 07 April 2022; Accepted: 01 June 2022;

Published: 28 June 2022.

Edited by:

Nicholas P. Hays, Nestle, SwitzerlandReviewed by:

Julie Lanigan, University College London, United KingdomMeghan JaKa, HealthPartners Institute for Education and Research, United States

Copyright © 2022 Cheng, Moore, Parks, Taveras, Wiehe and Carroll. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Erika R. Cheng, ZWNoZW5nQGl1LmVkdQ==

Erika R. Cheng

Erika R. Cheng Courtney Moore2

Courtney Moore2 Lisa Parks

Lisa Parks Elsie M. Taveras

Elsie M. Taveras Sarah E. Wiehe

Sarah E. Wiehe Aaron E. Carroll

Aaron E. Carroll