Abstract

Berberine-containing plants have been traditionally used in different parts of the world for the treatment of inflammatory disorders, skin diseases, wound healing, reducing fevers, affections of eyes, treatment of tumors, digestive and respiratory diseases, and microbial pathologies. The physico-chemical properties of berberine contribute to the high diversity of extraction and detection methods. Considering its particularities this review describes various methods mentioned in the literature so far with reference to the most important factors influencing berberine extraction. Further, the common separation and detection methods like thin layer chromatography, high performance liquid chromatography, and mass spectrometry are discussed in order to give a complex overview of the existing methods. Additionally, many clinical and experimental studies suggest that berberine has several pharmacological properties, such as immunomodulatory, antioxidative, cardioprotective, hepatoprotective, and renoprotective effects. This review summarizes the main information about botanical occurrence, traditional uses, extraction methods, and pharmacological effects of berberine and berberine-containing plants.

Introduction

Berberine

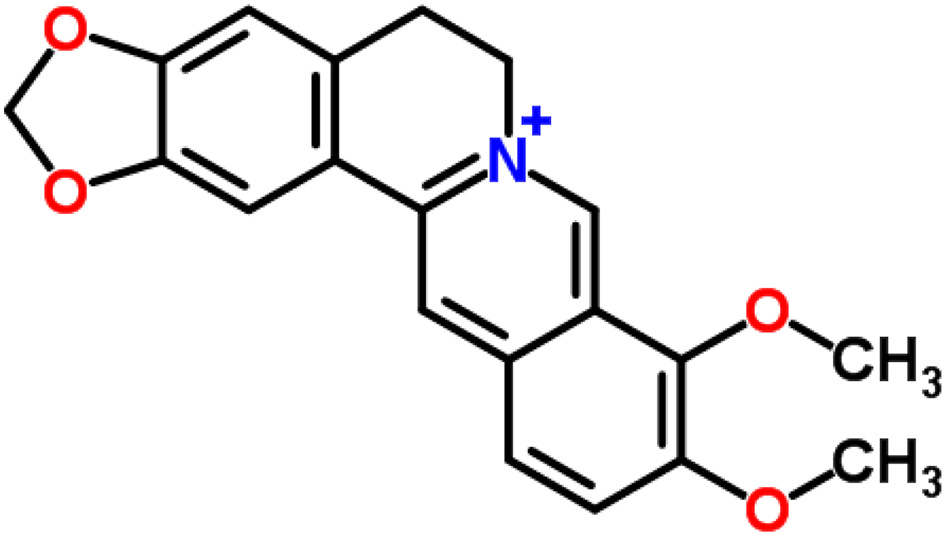

Berberine(5,6-dihydro-9,10-dimethoxybenzo[g]-1,3-benzodioxolo[5,6-a] quinolizinium) Figure 1, is a nonbasic and quaternary benzylisoquinoline alkaloid, a relevant molecule in pharmacology and medicinal chemistry. Indeed, it is known as a very important natural alkaloid for the synthesis of several bioactive derivatives by means of condensation, modification, and substitution of functional groups in strategic positions for the design of new, selective, and powerful drugs (Chen et al., 2005).

Figure 1

Berberine structure (according to ChemSpider database).

Traditional use of berberine-containing species

In the Berberidaceae family, the genus Berberis comprises of ~450–500 species, which represent the main natural source of berberine. Plants of this genus are used against inflammation, infectious diseases, diabetes, constipation, and other pathologies (Singh A. et al., 2010). The oldest evidence of using barberry fruit (Berberis vulgaris) as a blood purifying agent was written on the clay tablets in the library of Assyrian emperor Asurbanipal during 650 BC (Karimov, 1993). In Asia, the extensive use of the stem, stem bark, roots, and root bark of plants rich in berberine, particularly Berberis species, has more than 3000 years of history. Moreover, they have been used as raw material or as an important ingredient in Ayurvedic and traditional Chinese medicine (Birdsall, 1997; Kirtikar and Basu, 1998; Gupta and Tandon, 2004; Kulkarni and Dhir, 2010). In Ayurveda, Berberis species have been traditionally used for the treatment of a wide range of infections of the ear, eye, and mouth, for quick healing of wounds, curing hemorrhoids, indigestion and dysentery, or treatment of uterine and vaginal disorders. It has also been used to reduce obesity, and as an antidote for the treatment of scorpion sting or snakebite (Dev, 2006). Berberine extracts and decoctions are traditionally used for their activities against a variety of microorganisms including bacteria, viruses, fungi, protozoa, helminthes, in Ayurvedic, Chinese, and Middle-Eastern folk medicines (Tang et al., 2009; Gu et al., 2010).

In Yunani medicine, Berberis asiatica has multiple uses, such as for the treatment of asthma, eye sores, jaundice, skin pigmentation, and toothache, as well as for favoring the elimination of inflammation and swelling, and for drying ulcers (Kirtikar and Basu, 1998). Decoction of the roots, and stem barks originating from Berberis aristata, B. chitria, and B. lycium (Indian Berberis species), have been used as domestic treatment of conjunctivitis or other ophthalmic diseases, enlarged liver and spleen, hemorrhages, jaundice, and skin diseases like ulcers (Rajasekaran and Kumar, 2009). On the other hand, the use of decoction of Indian barberry mixed with honey has also been reported for the treatment of jaundice. Additionally, it has been reported the use of decoction of Indian barberry and Emblic myrobalan mixed with honey in the cure of urinary disorders as painful micturition (Kirtikar and Basu, 1998). Numerous studies dealing with its antimicrobial and antiprotozoal activities against different types of infectious organisms (Vennerstrom et al., 1990; Stermitz et al., 2000; Bahar et al., 2011) have been assessed so far. Moreover, it has been used to treat diarrhea (Chen et al., 2014) and intestinal parasites since ancient times in China (Singh and Mahajan, 2013), and the Eastern hemisphere, while in China it is also used for treating diabetes (Li et al., 2004).

Nowadays, a significant number of dietary supplements based on plants containing berberine (Kataoka et al., 2008) are used for reducing fever, common cold, respiratory infections, and influenza (Fabricant and Farnsworth, 2001). Another reported use for berberine-containing plants is their application as an astringent agent to lower the tone of the skin. Also, positive effects were observed on the mucous membranes of the upper respiratory tract and gastrointestinal system with effects on the associated ailments (Chen et al., 2014; Yu et al., 2016).

In southern South America leaves and bark of species of the genus Berberis are used in traditional medicine administered for mountain sickness, infections, and fever (San Martín, 1983; Houghton and Manby, 1985; Anesini and Perez, 1993).

Furthermore, there are other genera which contain berberine. The genus Mahonia comprises of several species that contain berberine. Within them, M. aquifolium has been traditionally used for various skin conditions. Due to its main alkaloid (berberine), is known to be used in Asian medicine for its antimicrobial activity. Coptidis rhizoma (rhizomes of Coptis chinensis), another plant which contains berberine, is a famous herb very frequently used in traditional Chinese medicine for the elimination of toxins, “damp-heat syndromes”, “purge fire”, and to “clear heat in the liver” (Tang et al., 2009). Table 1 gathers a synthesis of the main traditional uses of species containing berberine.

Table 1

| Family | Scientific name | Traditional uses | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Annonaceae | Annickia chlorantha (Oliv.) Setten & Maas (ex-Enantia chlorantha Oliv.) | Treat jaundice, hepatitis A, B, C, and D, conjunctivitis, leishmaniasis, medicine for cuts and infected wounds, sores and ulcers, antipyretic for various fevers, tuberculosis, vomiting of blood, urinary tract infections, treatment of fatigue, rheumatism, treat malaria symptoms, aches, wounds, boils, vomiting, yellow bitter, chills, sore, spleen in children and body pains, skin ailments, intercostal pain and to promote conception, intestinal worms, intestinal spasms, malaria and sexual asthenia, treat coughs and wounds; rickettsia fever, treat of sleeping sickness and dysentery, hemostatic and rickettsia, treat yellow fever and typhoid fever, treat diabetes, treat syphilis, and other infectious diseases, poliomyelitis, treat hypertension, treat HIV and prostate cancer | Oliver, 1960; Sandberg, 1965; Bouquet, 1969; Hamonniere et al., 1975; Onwuanibe, 1979; Burkill, 1985; Gill and Akinwumi, 1986; Gbile et al., 1988; Vennerstrom and Klayman, 1988; Vennerstrom et al., 1990; Adjanohoun et al., 1996; Nguimatsia et al., 1998; Kayode, 2006; Odugbemi et al., 2007; Ehiagbonare and Onyibe, 2008; Jiofack et al., 2008, 2009; Kadiri, 2008; Ogbonna et al., 2008; Olowokudejo et al., 2008; Betti and Lejoly, 2009; Ndenecho, 2009; Adeyemi et al., 2010; Noumi, 2010; Noumi and Anguessin, 2010; Noumi and Yumdinguetmun, 2010; Bele et al., 2011; Din et al., 2011; Ngono Ngane et al., 2011; Oladunmoye and Kehinde, 2011; Gbolade, 2012; Musuyu Muganza et al., 2012; Tsabang et al., 2012; Betti et al., 2013; Borokini et al., 2013; Fongod, 2014; Ishola et al., 2014; Ohemu et al., 2014 |

| Annickia pilosa (Exell) Setten & Maas (ex-Enantia pilosa Exell) | Medicine for cuts | Versteegh and Sosef, 2007 | |

| Annickia polycarpa (DC.) Setten & Maas ex I.M.Turner (ex-Enantia polycarpa (DC.) Engl. & Diels) | Treat cuts, antiseptic to treat sores, stomach ulcers, leprosy and ophthalmia, treatment of skin infections and sores, treat jaundice, and treat fever including malaria and to promote wound healing, against intestinal problems | Irvine, 1961; Bouquet and Debray, 1974; Ajali, 2000; Govindasamy et al., 2007; Versteegh and Sosef, 2007 | |

| Rollinia mucosa (Jacq.) Baill. | Treat of tumors | Hartwell, 1982 | |

| Xylopia polycarpa (DC.) Oliv. | Treat wounds, ulcers, leprosy, rheumatism, stomach and gall-bladder problems, eye diseases, for conception, diarrhea, malaria, fevers and sleeping disorders | Neuwinger, 1996 | |

| Berberidaceae | Berberis actinacantha Mart. | Antipyretic | San Martín, 1983 |

| Berberis aquifolium Pursh | Skin conditions, treat eczema, acne, conjunctivitis and herpes, alleviate the symptoms of psoriasis, treat diarrhea and in higher doses to treat constipation, improvement of blood flow to the liver, stimulate intestinal secretions and bile flow, treat jaundice, hepatitis, cirrhosis and general digestive problems, treatment of gall bladder disease, hemorrhages and a few forms of cancer, fungal infections, dysentery, anti-inflammatory properties, stomach problems, sore womb following childbirth and/or menstruation | King, 1898; Ritch-Krc et al., 1996 | |

| Berberis aristata DC. | Treat allergies, metabolic disorders, ophthalmia, and other eye diseases, treat bleeding piles, anti-osteoporosis, treat skin diseases, menorrhagia, fever, diarrhea, dysentery, cholera, jaundice, ear and urinary tract infections, anti-bacterial, anti-fungal, anti-inflammatory, analgesic, anti-pyretic, jaundice, piles, malaria, laxative, anti-scorbutic, anti-diabetic, and anti-hepatopathic | Bhattacharjee et al., 1980; Duke and Beckstrom-Sternberg, 1994; Küpeli et al., 2002; Acharya and Rokaya, 2005; Chhetri et al., 2005; Kunwar and Adhikari, 2005; Sharma et al., 2005; Joshi and Joshi, 2007; Meena et al., 2009; Shahid et al., 2009; Phondani et al., 2010; Saraf et al., 2010; Tiwary et al., 2010; Sati and Joshi, 2011; Yogesh et al., 2011 | |

| Berberis asiatica Roxb. ex DC. | Jaundice, diabetes mellitus, wound healing, asthma; drying unhealthy ulcers, anti-inflammatory, swelling, treat pneumococcal infections, eye (conjunctivitis) and ear diseases, rheumatism, fever, stomach disorders, skin disease (hyperpigmentation), malarial fever, laxative, teeth problems (toothache), and headache | Watt, 1883; Kirtikar and Basu, 1933; Samhita, 1963; Hashmi and Hafiz, 1986; Bhandari et al., 2000; Shah and Khan, 2006; Uniyal et al., 2006; Uprety et al., 2010; Maithani et al., 2014 | |

| Berberis buxifolia Lam. | Treat infections | Anesini and Perez, 1993; Mølgaard et al., 2011 | |

| Berberis chitria Buch.-Ham. ex Lindl. | Treat skin disease, jaundice, rheumatism, affection of eyes (household treatment for conjunctivitis, ophthalmic, bleeding piles), ulcers, skin diseases, enlarged liver and spleen | Watt, 1883; Kirtikar and Basu, 1933; Sir and Chopra, 1958 | |

| Berberis darwinii Hook. | Antipyrectic, anti-inflammatory, treat stomach pains, indigestion, and colitis | Montes and Wilkomirsky, 1987 | |

| Berberis empetrifolia Lam. | Treat mountain sickness | San Martín, 1983 | |

| Berberis integerrima Bunge. | Antipyretic, treat diabetes, bone fractures, rheumatism, radiculitis, heart pain, stomach aches, kidney stones, tuberculosis, chest pain, headaches, constipation, and wound | Khalmatov, 1964; Khodzhimatov, 1989; Baharvand-Ahmadi et al., 2016 | |

| Berberis jaeschkeana C. K. Schneid. | Treat eye diseases | Kala, 2006 | |

| Berberis koreana Palib. | Antipyretic, treat gastroenteritis, sore throats, and conjunctivitis | Ahn, 2003 | |

| Berberis leschenaultia Wall. ex Wight & Arn. | Antipyretic, cold and complications during post-natal period | Rajan and Sethuraman, 1992 | |

| Berberis libanotica Ehrenb. ex C. K. Schneid. | Treat rheumatic and neuralgic diseases, anti-inflammatory, treat arthritis and muscular pain | El Beyrouthy et al., 2008; Esseily et al., 2012 | |

| Berberis lycium Royle | Treat eye diseases, febrifuge, jaundice, diarrhoea, menorrhagia, piles, backache, dysentery, earache, fracture, eye ache, pimples, boils, wound healing, cough and throat pain, intestinal colic, diabetes, throat pain, scabies, bone fractures, sun blindness, against stomachache and intestinal problems | Zaman and Khan, 1970; ul Haq and Hussain, 1993; Bushra et al., 2000; Kaur and Miani, 2001; Hamayun et al., 2003; Ahmed et al., 2004; Abbasi et al., 2005, 2009, 2010; Shah and Khan, 2006; Zabihullah et al., 2006; Hussain et al., 2008; Sood et al., 2010 | |

| Berberis microphylla G. Forst. (ex-Berberis heterophylla Juss. ex Poir.) | Febrifuge, anti-inflammatory and treat diarrhea | Muñoz, 2001 | |

| Berberis oblonga (Regel) C. K. Schneid | Heart tonic, treat neurasthenia, antipyretic, antidiarrheal, treat rheumatism, eye diseases and wounds of the mouth, jaundice, stomach aches, back pain and arthralgia | Khalmatov, 1964; Sezik et al., 2004; Pak, 2005 | |

| Berberis petiolaris Wall. ex G. Don | Treat malarial fever, diarrhea, conjunctivitis, and jaundice | Karimov, 1993 | |

| Berberis pseudumbellata R. Parker | Diuretic, treat jaundice, intestinal disorders, eye diseases, oxytocic and throat ache, stomach problems and ulcers | Kala, 2006; Khan and Khatoon, 2007; Singh et al., 2009; Khan et al., 2016 | |

| Berberis thunbergii DC. | Anti-inflammatory | Küpeli et al., 2002 | |

| Berberis tinctoria Lesch. | Antimicrobial for skin disease, jaundice, affection of eyes, treat menorrhagia, diarrhea, and rheumatism | Fyson, 1975; Satyavati et al., 1987 | |

| Berberis umbellata Wall. ex G. Don | Treating fever, jaundice, nausea, eye disorders and skin problems, tonic | Singh et al., 2012 | |

| Berberis vulgaris L. | Antiarrhythmic, sedative, anticancer, heal internal injuries, remove kidney stones, treat sore throat and fever | Tantaquidgeon, 1928; Chaudhury et al., 1980; Zovko Koncić et al., 2010 | |

| Caulophyllum thalictroides (L.) Michaux | Menstrual cramps, relieve the pain of childbirth, promote prompt delivery, treat colics, cramps, hysteria, rheumatism, uterine stimulant, inducer of menstruation, and antispasmodic | Castleman, 1991; Hutchens, 1992 | |

| Jeffersonia diphylla (L.) Pers. | Antispasmodic, diuretic, emetic, expectorant, treat diarrhea, dropsy, gravel and urinary problems, emetic, expectorant, treat sores, ulcers and inflamed parts | Uphof, 1959; Duke and Ayensu, 1985; Foster and Duke, 1990; Coffey, 1993; Moerman, 1998; Lust, 2014 | |

| Mahonia fortunei (Lindl.) Fedde | Anticancer, febrifuge, antiodontalgic, treat testicular swelling and arthritic pain | Duke and Ayensu, 1985; He and Mu, 2015 | |

| Mahonia napaulensis DC. | Diuretic, demulcent, treat dysentery and inflammations of the eyes | Chopra et al., 1986; Manandhar, 2002 | |

| Nandina domestica Thunb. | Antitussive, astringent, febrifuge, stomachic and tonic, treat of fever in influenza, acute bronchitis, whooping cough, indigestion, acute gastro-enteritis, tooth abscess, pain in the bones, muscles and traumatic injuries, and antirheumatic | Kariyone and Koiso, 1971; Duke and Ayensu, 1985; Fogarty, 1990 | |

| Sinopodophyllum hexandrum (Royle) T. S. Ying | Regulate menstruation, promote the circulation of blood, treat amenorrhea, difficult labor and retention of dead fetus or placenta | Kong et al., 2010 | |

| Menispermaceae | Tinospora sinensis (Lour.) Merr (ex-Tinospora cordifolia (Willd.) Miers) | Tonic, antiperiodic, anti-spasmodic, anti-inflammatory, antiarthritic, anti-allergic, anti-diabetic, improve the immune system, antistress, anti-leprotic and anti-malarial activities | Singh et al., 2003 |

| Papaveraceae | Argemone albiflora Hornem (ex-Argemone alba F. Lestib.) | Anthydropic, cathartic, diaphoretic, diuretic, demulcent, emetic, purgative, treat jaundice, skin ailments, colds, colics and wounds | Smyth, 1903; Foster and Duke, 1990 |

| Argemone mexicana L. | Analgesic, antispasmodic, sedative, treat warts, cold sores, cutaneous affections, skin diseases, itches, treat cataracts, treat dropsy, jaundice, treat chronic skin diseases, expectorant, treat coughs and chest complaints, demulcent, emetic, expectorant, laxative and antidote to snake poisoning | Uphof, 1959; Pesman, 1962; Usher, 1974; Stuart and Smith, 1977; Emboden, 1979; Chopra et al., 1986; Coffey, 1993; Chevallier, 1996 | |

| Argemone platyceras L. | Treat respiratory ailments as asthma, cough, bronchitis and pneumonia | Emes et al., 1994 | |

| Bocconia frutescens L. | Treat skin conditions (ulcers and eruptions) and respiratory tract infections (bronchistis and tuberculosis) | Martinez, 1977, 1984 | |

| Chelidonium majus L. | Treat ophthalmic diseases (remove films from the cornea of the eye), mild sedative, antispasmodic, relaxing the muscles of the bronchial tubes and intestines, treat warts, alterative, anodyne, antispasmodic, cholagogue, diaphoretic, diuretic, hydrogogue, narcotic, purgative, treat bronchitis, whooping cough, asthma, jaundice, gallstones and gallbladder pains, anticancer, analgesic, treat stomach ulcer, treat get rid of warts, ringworm and corns | Launert, 1981; Grieve, 1984; Phillips and Foy, 1990; Phillips and Rix, 1991; Chevallier, 1996; Lust, 2014 | |

| Corydalis solida subsp. brachylova | Anodyne, antibacterial, antispasmodic, hallucinogenic, calm the nerves, sedative for insomnia, CNS stimulant, painkiller, treat painful menstruation, lowering the blood pressure, traumatic injury and lumbago | Launert, 1981; Bown, 1995 | |

| Corydalis solida subsp. slivenensis (Velen.) Hayek (ex-Corydalis slivenensis Velen.) | |||

| Corydalis solida subsp. tauri cola | |||

| Corydalis turtschaninovii Besser (ex-Corydalis ternata (Nakai) Nakai) | Treat memory dysfunction, treat gastric, duodenal ulcer, cardiac arrhythmia disease, rheumatism and dysmenorrhea | Tang and Eisenbrand, 1992; Kamigauchi and Iwasa, 1994; Orhan et al., 2004; Houghton et al., 2006 | |

| Eschscholzia californica Cham. | Sedative, diuretic, relieve pain, relax spasms, promote perspiration, treat nervous tension, anxiety, insomnia, urinary incontinence (especially in children), narcotic, relieve toothache, antispasmodic, analgesic and suppress the flow of milk in lactating women | Coffey, 1993; Bown, 1995; Chevallier, 1996; Moerman, 1998 | |

| Glaucium corniculatum (L.) Rud. subsp. corniculatum | Reduce warts, antitusive, treat CNS disturbances, sedative, cooling, and mild laxative | Al-Douri, 2000; Al-Qura'n, 2009; Hayta et al., 2014 | |

| Macleaya cordata (Willd.) R.Br. | Analgesic, antioedemic, carminative, depurative, diuretic, treat insect bites, and ringworm | Grieve, 1984; Duke and Ayensu, 1985 | |

| Macleaya microcarpa (Maxim.) Fedde | Treat some skin diseases and inflammation | Deng and Qin, 2010 | |

| Papaver dubium L. | Sudorific, diuretic, expectorant and ophthalmia | Chopra et al., 1986 | |

| Papaver dubium var. lecoquii | |||

| Papaver rhoeas L. var. chelidonioides | Ailments in the elderly and children, mild pain reliever, treat irritable coughs, reduce nervous over-activity, anodyne, emollient, emmenagogue, expectorant, hypnotic, slightly narcotic, sedative, treat bronchial complaints and coughs, insomnia, poor digestion, nervous digestive disorders and minor painful conditions, treat jaundice, fevers, and anticancer | Uphof, 1959; Launert, 1981; Grieve, 1984; Duke and Ayensu, 1985; Phillips and Foy, 1990; Bown, 1995; Chevallier, 1996 | |

| Papaver hybridum L. | Treat dermatologic diseases, anti-infective, diuretic, sedative, and antitussive | Rivera Núñez and Obon de Castro, 1996; Ali et al., 2018 | |

| Ranunculaceae | Coptis chinensis Franch. | Control of bacterial and viral infections, relax spasms, lower fevers, stimulate the circulation, treat diabetes mellitus, analgesic, locally anaesthetic, antibacterial, antipyretic, bitter, blood tonic, carminative, cholagogue, digestive, sedative, stomachic, vasodilator, treat diarrhoea, acute enteritis and dysentery, treat insomnia, fidget, delirium due to high fever, leukaemia and otitis media, treat conjunctivitis, skin problems (acne, boils, abscesses and burns whilst), mouth, tongue ulcers, swollen gums, and toothache | Uphof, 1959; Usher, 1974; Duke and Ayensu, 1985; Yeung, 1985; Bown, 1995 |

| Coptis japonica (Thunb.) Makino | Control of bacterial and viral infections, relax spasms, lower fevers, stimulate the circulation, locally analgesic and anaesthetic, anti-inflammatory, stomachic, treat conjunctivitis, intestinal catarrh, dysentery, enteritis, high fevers, inflamed mouth and tongue | Kariyone and Koiso, 1971; Usher, 1974; Grieve, 1984; Bown, 1995 | |

| Coptis teeta Wall. | Control of bacterial and viral infections, relaxes spasms, lowers fevers and stimulate the circulation, locally analgesic, anaesthetic, ophthalmic and pectoral diseases, effective antibacterial, treat dysentery | Stuart and Smith, 1977; Duke and Ayensu, 1985; Bown, 1995 | |

| Hydrastis canadensis L. | Treat disorders of the digestive system and mucous membranes, treat constipation, antiperiodic, antiseptic, astringent, cholagogue, diuretic, laxative, stomachic, tonic, treat disorders affecting the ears, eyes, throat, nose, stomach, intestines, and vagina | Uphof, 1959; Weiner, 1980; Grieve, 1984; Mills, 1985; Foster and Duke, 1990; Coffey, 1993; Bown, 1995; Chevallier, 1996; Lust, 2014 | |

| Xanthorhiza simplicissima Marshall | Treat mouth ulcers, stomach ulcers, colds, jaundice, treat piles, and digestive disorders | Weiner, 1980; Foster and Duke, 1990; Moerman, 1998 | |

| Rutaceae | Phellodendron amurense Rupr. | Treat gastroenteritis, abdominal pain and diarrhea, antiinflammator, immunostimulator and treat cancer (antitumor activities) | Uchiyama et al., 1989; Park et al., 1999 |

| Act strongly on the kidneys, detoxicant for hot damp conditions, treat meningitis, conjunctivitis, antibacterial, antirheumatic, aphrodisiac, bitter stomachic, cholagogue, diuretic, expectorant, febrifuge, hypoglycaemic, treat ophtalmia, skin, vasodilator and tonic, treat acute diarrhoea, dysentery, jaundice, vaginal infections (with Trichomonas vaginalis), acute urinary tract infections, enteritis, boils, abscesses, night sweats and skin diseases, and expectorant | Kariyone and Koiso, 1971; Usher, 1974; Stuart and Smith, 1977; Grieve, 1984; Yeung, 1985; Bown, 1995; Chevallier, 1996 | |

| Zanthoxylum monophyllum Tul. | Treat eye infections and dark vomitus | Hirschhorn, 1981; Eric Brussell, 2004 |

Traditional uses of berberine-containing species.

Botanical sources of berberine

Berberine has been detected, isolated, and quantified from various plant families and genera including Annonaceae (Annickia, Coelocline, Rollinia, and Xylopia), Berberidaceae (Berberis, Caulophyllum, Jeffersonia, Mahonia, Nandina, and Sinopodophyllum), Menispermaceae (Tinospora), Papaveraceae (Argemone, Bocconia, Chelidonium, Corydalis, Eschscholzia, Glaucium, Hunnemannia, Macleaya, Papaver, and Sanguinaria), Ranunculaceae (Coptis, Hydrastis, and Xanthorhiza), and Rutaceae (Evodia, Phellodendron, and Zanthoxyllum) (Table 2). The genus Berberis is well-known as the most widely distributed natural source of berberine. The bark of B. vulgaris contains more than 8% of alkaloids, berberine being the major alkaloid (about 5%) (Arayne et al., 2007).

Table 2

| Family | Scientific name | Common name | Used part | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Annonaceae | Annickia chlorantha (Oliv.) Setten & Maas (ex-Enantia chlorantha Oliv.) | African whitewood, african yellow wood Epfoué, Péyé, Nfol, Poyo | Bark | Mell, 1929 |

| Annickia pilosa (Exell) Setten & Maas (ex-Enantia pilosa Exell) | – | Bark | Buzas and Egnell, 1965 | |

| Annickia polycarpa (DC.) Setten & Maas ex I. M. Turner (ex-Enantia polycarpa (DC.) Engl. & Diels) | African yellow wood | Bark | Buzas and Egnell, 1965 | |

| Coelocline polycarpa A.DC. | Yellow-dye tree of Soudan | Bark | Henry, 1949 | |

| Rollinia mucosa (Jacq.) Baill. | Biriba, wild sweet sop, wild cashina | Fruit | Chen et al., 1996 | |

| Xylopia macrocarpa A.Chev. | Jangkang | Stem bark | Willaman and Schubert, 1961 | |

| Xylopia polycarpa (DC.) Oliv. | – | Stem bark | Willaman and Schubert, 1961 | |

| Berberidaceae | Berberis aetnensis C.Presl | – | Roots | Bonesi et al., 2013 |

| Leaves | Musumeci et al., 2003 | |||

| Root | Henry, 1949 | |||

| Berberis amurensis Rupr. | Barberry | Stem & roots | Tomita and Kugo, 1956 | |

| Berberis aquifolium Pursh | Oregon grape | Roots | Parsons, 1882 | |

| Berberis aristata DC. | Tree turmeric | Bark | Chakravarti et al., 1950 | |

| Roots | Singh A. et al., 2010 | |||

| Stem | ||||

| Raw herb | Singh R. et al., 2010 | |||

| Extract | ||||

| Fruit | Kamal et al., 2011 | |||

| Roots | Andola et al., 2010a,c | |||

| Roots | Rashmi et al., 2009 | |||

| Roots | Singh and Kakkar, 2009 | |||

| Roots | Srivastava et al., 2004 | |||

| Roots | Srivastava et al., 2001 | |||

| Bark | Willaman and Schubert, 1961 | |||

| Berberis asiatica Roxb. ex DC. | Chutro, rasanjan (Nep); marpyashi (Newa); daruharidra, darbi (Sans) | Roots | Andola et al., 2010b | |

| Roots | Andola et al., 2010c | |||

| Roots | Srivastava et al., 2004 | |||

| Roots, stem, bark | Willaman and Schubert, 1961 | |||

| Berberis barandana Vidal. | – | ND | Willaman and Schubert, 1961 | |

| Berberis beaniana C. K. Schneid. | Kang song xiao bo (pinyin, China) | – | Steffens et al., 1985 | |

| Berberis chitria Buch.-Ham. ex Lindl. | Chitra, indian barberry | Whole plant | Hussaini and Shoeb, 1985 | |

| Roots | Srivastava et al., 2006a,b,c | |||

| Berberis concinna Hook.f. | Barberry | Stem bark | Tiwari and Masood, 1979 | |

| Berberis congestiflora Gay | Michay | Leaves and stem | Torres et al., 1992 | |

| Berberis coriaria Royle ex Lindl. | – | Stem bark | Tiwari and Masood, 1979 | |

| Berberis croatica Mart. ex Schult. & Schult.f. | Croatian barberry | Roots | Končić et al., 2010 | |

| Roots | Kosalec et al., 2009 | |||

| Berberis darwinii Hook. | Michai, calafate | Roots | Richert, 1918 | |

| Leaves | Urzúa et al., 1984 | |||

| Stem-bark | Habtemariam, 2011 | |||

| Berberis densiflora Raf. | – | Leaves | Khamidov et al., 1997b | |

| Berberis floribunda Wall. ex G.Don | Nepal barberry | Roots | Chatterjee, 1951 | |

| Berberis fortunei Lindl. | Fortune's Mahonia | Wood | Willaman and Schubert, 1961 | |

| Berberis guimpelii K. Koch & C. D. Bouché | – | Roots | Petcu, 1965a | |

| Berberis heteropoda Schrank | – | Root bark | Willaman and Schubert, 1961 | |

| Berberis himalaica Ahrendt | – | Stem-bark | Chatterjee et al., 1952 | |

| Berberis horrida Gay | – | Leaves and stem | Torres et al., 1992 | |

| Berberis iliensis Popov | – | Young shoots | Karimov and Shakirov, 1993 | |

| Roots | Dzhalilov et al., 1963 | |||

| Berberis integerrima Bunge. | – | Root | Karimov et al., 1993 | |

| Leaves | Karimov et al., 1993; Khamidov et al., 1996c, 1997b | |||

| Berberis jaeschkeana C. K. Schneid. | Jaeschke's Barberry | – | Rashid and Malik, 1972 | |

| Berberis jamesonii Lindl (ex-Berberis glauca Benth) | – | – | Willaman and Schubert, 1961 | |

| Berberis japonica R.Br | Japanese Mahonia | Wood, root | Willaman and Schubert, 1961 | |

| Berberis kawakamii Hayata | – | Roots | Yang and Lu, 1960a | |

| Berberis koreana Palib. | Korean barberry | Bark of the stem | Petcu, 1965b | |

| Bark of the roots | ||||

| Seeds | ||||

| Stem | ||||

| Roots | ||||

| – | Kostalova et al., 1982 | |||

| Roots | Yoo et al., 1986 | |||

| Leaves | ||||

| Berberis lambertii R. Parker | – | Roots | Chatterjee and Banerjee, 1953 | |

| Berberis laurina Thunb | Laurel barberry | Roots | Gurguel et al., 1934; Willaman and Schubert, 1961 | |

| Berberis leschenaultii Wall. ex Wight & Arn (ex-Mahonia leschenaultii (Wall. ex Wight & Arn.) Takeda) | – | Bark | Willaman and Schubert, 1961 | |

| Berberis libanotica Ehrenb. ex C. K. Schneid. | – | Root | Bonesi et al., 2013 | |

| Berberis lycium Royle | Boxthorn barberry | Roots | Andola et al., 2010c | |

| Berberis microphylla G. Forst. (ex-Berberis heterophylla Juss. ex Poir. Berberis buxifolia Lam.) | Patagonian barberry, magellan barberry, calafate | Roots | Freile et al., 2006 | |

| – | Rashid and Malik, 1972 | |||

| Berberis mingetsensis Hayata | – | Roots | Yang and Lu, 1960b | |

| Berberis nummularia Bunge | Nummular barberry | Young shoots | Karimov et al., 1993 | |

| Berberis morrisonensis Hayata | – | Roots | Yang, 1960a,b | |

| Stem | ||||

| – | ||||

| Berberis nepalensis Spreng. (ex-Mahonia acanthifolia Wall. ex G.Don) | – | – | Willaman and Schubert, 1961 | |

| Berberis nervosa Pursh | Dwarf Oregon-grape | – | Willaman and Schubert, 1961 | |

| Berberis oblonga (Regel) C. K. Schneid | Oblong barberry | Stem | Karimov and Lutfullin, 1986; Gorval' and Grishkovets, 1999 | |

| Leaves | Khamidov et al., 2003 | |||

| Roots | Tadzhibaev et al., 1974 | |||

| Berberis petiolaris Wall. ex G. Don | Chochar | Roots | Huq and Ikram, 1968 | |

| Berberis pseudumbellata R. Parker | – | Roots | Andola et al., 2010b | |

| Stem bark | ||||

| – | Pant et al., 1986 | |||

| Berberis repens Lindl. | Creeping mahonia, creeping Oregon grape, creeping barberry, or prostrate barberry | – | Willaman and Schubert, 1961 | |

| Berberis sargentiana C. K. Schneid. | Sankezhen | – | Liu, 1992 | |

| Berberis swaseyi Buckley | – | – | Willaman and Schubert, 1961 | |

| Berberis thunbergii DC. | Japanese barberry | Stem | Khamidov et al., 1997a | |

| Leaves | Khamidov et al., 1997a | |||

| Berberis tinctoria Lesch. | Nilgiri barberry | Roots | Srivastava and Rawat, 2007 | |

| Berberis trifolia (Cham. & Schltdl.) Schult. & Schult.f. | – | Root, stem | Willaman and Schubert, 1961 | |

| Berberis turcomanica Kar. ex Ledeb. | – | Leaves | Khamidov et al., 1996a,b,c | |

| Berberis umbellata Wall. ex G.Don | Himalayan barberry | Roots | Singh et al., 2012 | |

| Berberis vulgaris L. | Barberry | Stems and roots | Imanshahidi and Hosseinzadeh, 2008 | |

| Roots | Končić et al., 2010 | |||

| Roots | Kosalec et al., 2009 | |||

| Berberis waziristanica Hieron. | – | Root bark | Atta-ur-Rahma and Ahmad, 1992 | |

| Caulophyllum thalictroides (L.) Michaux (ex-Leontice thalictroides L.) | Blue cohosh | – | Willaman and Schubert, 1961 | |

| Jeffersonia diphylla (L.) Pers. | Twinleaf | – | Willaman and Schubert, 1961 | |

| Mahonia borealis Takeda | – | – | Willaman and Schubert, 1961 | |

| Mahonia fortunei (Lindl.) Fedde | Fortune's Mahonia | wood | Willaman and Schubert, 1961 | |

| Mahonia napaulensis DC. (ex- Mahonia griffithii; ex-Mahonia manipurensis Takeda; Mahonia sikkimensis Takeda) | Nepal Barberry | bark | Willaman and Schubert, 1961 | |

| Mahonia simonsii Takeda | – | – | Willaman and Schubert, 1961 | |

| Nandina domestica Thunb. | Nandina, heavenly bamboo or sacred bamboo | bark, root | Willaman and Schubert, 1961 | |

| Sinopodophyllum hexandrum (Royle) T.S.Ying | Himalayan May Apple, Indian may apple | Root, rhizome | Willaman and Schubert, 1961 | |

| Menispermaceae | Tinospora sinensis (Lour.) Merr. (ex-Tinospora cordifolia) (Willd.) Miers | Gulbel, indian tinospora | Stem | Srinivasan et al., 2008 |

| – | Singh et al., 2003 | |||

| Papaveraceae | Argemone albiflora Hornem. (ex-Argemone alba F.Lestib.) | White prickly poppy, Bluestem pricklypoppy | Aerial part and roots | Slavikova et al., 1960 |

| Foote, 1932 | ||||

| Israilov and Yunusov, 1986 | ||||

| Argemone hybrida R.Otto & Verloove | – | Leaves and stem | Israilov and Yunusov, 1986 | |

| Argemone mexicana L. | Prickly poppy | Apigeal parts, seeds | Haisova and Slavik, 1975; Israilov and Yunusov, 1986; Fletcher et al., 1993 | |

| Leaves | Bapna et al., 2015 | |||

| Seeds | Fletcher et al., 1993 | |||

| – | Singh, 2014 | |||

| – | Majumder et al., 1956; Hakim et al., 1961; Misra et al., 1961 | |||

| Superterranean parts | Slavikova and Slavik, 1955 | |||

| Roots | ||||

| – | Santos and Adkilen, 1932; de Almeida Costa, 1935; Misra et al., 1961; Doepke et al., 1976; Abou-Donia and El-Din, 1986; Monforte-Gonzalez et al., 2012 | |||

| Roots | Pathak et al., 1985; Kukula-Koch and Mroczek, 2015 | |||

| Leaves and capsules | Schlotterbeck, 1902 | |||

| Whole plant | Bose et al., 1963; Haisova and Slavik, 1975 | |||

| Latex | Santra and Saoji, 1971 | |||

| Argemone ochroleuca Sweet | Chicalote | Seeds | Fletcher et al., 1993 | |

| Argemone platyceras L. | Chicalote poppy, crested poppy | Leaves and stem | Israilov and Yunusov, 1986 | |

| Argemone subintegrifolia Ownbey | – | Aerial part | Stermitz et al., 1974 | |

| Argemone squarrosa Greene | Hedgehog pricklypoppy | Aerial part | Stermitz, 1967 | |

| Bocconia frutescens L. | Plume poppy, tree poppy, tree celandine, parrotweed, sea oxeye daisy, john crow bush | Leaves | Slavik and Slavikova, 1975 | |

| Roots, stalks, leaves | Taborska et al., 1980 | |||

| Chelidonium majus L. | Celandine poppy | Roots | Jusiak, 1967 | |

| Corydalis chaerophylla DC. | Fitweed | Roots | Jha et al., 2009 | |

| Corydalis ophiocarpa Hook. f. et Thoms | Fitweed | Manske, 1939 | ||

| Corydalis solida subsp. brachyloba | Fitweed | Aerial parts | Sener and Temizer, 1988, 1991 | |

| Corydalis solida subsp. slivenensis (Velen.) Hayek (ex-Corydalis slivenensis Velen.) | Fitweed | – | Kiryakov et al., 1982a,b | |

| Corydalis solida subsp. tauricola | Fitweed | – | Kiryakov et al., 1982b | |

| Rhizome | Sener and Temizer, 1990 | |||

| Corydalis turtschaninovii Besser. (ex-Corydalis ternata (Nakai) Nakai) | Fitweed | Tubers | Lee and Kim, 1999 | |

| Eschscholzia californica Cham. | Californian poppy | Roots | Gertig, 1964 | |

| Glaucium corniculatum (L.) Rud. subsp. corniculatum | Blackspot Hornpoppy | Aerial parts | Doncheva et al., 2014 | |

| – | Slavik and Slavikova, 1957 | |||

| Glaucium grandiflorum Boiss. & A.Huet | Red Horned Poppy, Grand-flowered Horned Poppy | Aerial part | Phillipson et al., 1981 | |

| Hunnemannia fumariifolia Sweet | Mexican Tulip Poppy, Golden Cup | Roots | Slavikova and Slavik, 1966 | |

| Macleaya cordata (Willd.) R.Br. | Plume poppy | – | Kosina et al., 2010 | |

| Macleaya microcarpa (Maxim.) Fedde | Poppy | Roots | Pěnčíková et al., 2011 | |

| Papaver dubium L. | Long-Head Poppy | Roots | Slavik et al., 1989 | |

| Papaver dubium var. lecoquii | Long-Head Poppy | Latex | Egels, 1959 | |

| Papaver rhoeas L. var. chelidonioides | Corn Poppy | Roots | Slavík, 1978 | |

| Papaver hybridum L. | Poppy | Aerial part | Phillipson et al., 1981 | |

| Sanguinaria canadensis L. | Bloodroot | Greathouse, 1939 | ||

| Ranunculaceae | Coptis chinensis Franch. | Chinese goldthread | Roots | Jin and Shan, 1982 |

| Roots | Lou et al., 1982 | |||

| Coptis japonica (Thunb.) Makino | Japanese goldthread | Rhizome | Kubota et al., 1980 | |

| Coptis teeta Wall. | Gold thread | Rhizome | Chen and Chen, 1988 | |

| Rhizome | Zhang et al., 2008 | |||

| Roots | ||||

| Hydrastis canadensis L. | Goldenseal | – | Baldazzi et al., 1998 | |

| – | Leone et al., 1996 | |||

| Xanthorhiza simplicissima Marshall | Yellowroot | Root, stem, and leaves | Okunade et al., 1994 | |

| Rutaceae | Evodia meliaefolia (Hance ex Walp.) Benth. | – | Bark | Perkin and Hummel, 1895 |

| Phellodendron amurense Rupr. | Amur cork tree | Bark | Chiang et al., 2006 | |

| Root bark | Zhang et al., 2008 | |||

| Trunk bark | ||||

| Perennial Branch bark | ||||

| Annual branches | ||||

| Leaves | ||||

| Phellodendron chinense C. K. Schneid. | Chinese cork tree | Bark | Chan et al., 2007 | |

| Phellodendron chinense var. glabriusculum C. K. Schneid. (ex-Phellodendron wilsonii Hayata & Kaneh.) | Chinese cork tree | Bark, branch, leaf and heartwood | Chen, 1981 | |

| – | Tan et al., 2013 | |||

| Bark | Chen, 1982 | |||

| Phellodendron lavallei Dode | Lavalle corktree | Bark | Yavich et al., 1993 | |

| Zanthoxylum monophyllum (Lam.) P. Wilson | Palo rubio | Stem and branches | Stermitz and Sharifi, 1977 | |

| Zanthoxylum quinduense Tul. | – | – | Ladino and Suárez, 2010 |

Botanical sources of berberine.

Berberine is also widely present in barks, leaves, twigs, rhizomes, roots, and stems of several medicinal plants species, including Argemone mexicana (Etminan et al., 2005), Berberis aristata, B. aquifolium, B. heterophylla, B. beaniana, Coscinium fenestratum (Rojsanga and Gritsanapan, 2005), C. chinensis, C. japonica, C. rhizome, Hydratis canadensis (Imanshahidi and Hosseinzadeh, 2008), Phellodendron amurense, P. chinense, Tinospora cordifolia (Khan et al., 2011), Xanthorhiza simplicissima (Bose et al., 1963; Knapp et al., 1967; Sato and Yamada, 1984; Steffens et al., 1985; Inbaraj et al., 2001; Liu et al., 2008a; Srinivasan et al., 2008; Vuddanda et al., 2010). Several researches found that berberine is widely distributed in the barks, roots, and stems of plants, nevertheless, bark and roots are richer in berberine compared to other plant parts (Andola et al., 2010a,b). In the Papaveraceae family, Chelidonium majus is another important herbal source of berberine (Tomè and Colombo, 1995). An important number of plants for medicinal use, such as Coptidis rhizoma and barberry, are the natural sources with the highest concentration of berberine. Barberries, such as Berberis aristata, B. aquifolium, B. asiatica, B. croatica, B. thunbergii, and B. vulgaris, are shrubs grown mainly in Asia and Europe, and their barks, fruits, leaves, and roots are often widely used as folk medicines (Imanshahidi and Hosseinzadeh, 2008; Kosalec et al., 2009; Andola et al., 2010c; Kulkarni and Dhir, 2010). Different research groups have reported that maximum berberine concentration accumulates in root (1.6–4.3%) and in most of the Berberis species, plants that grow at low altitude contain more berberine compared to higher altitude plants (Chandra and Purohit, 1980; Mikage and Mouri, 1999; Andola et al., 2010a). However, a correlation could not be established within the results of berberine concentration regarding to species and season of the year (Srivastava et al., 2006a,c; Andola et al., 2010c; Singh et al., 2012). Comparative studies of berberine concentration contained in different species of the same genus have been reported, e.g., higher berberine content in B. asiatica (4.3%) in comparison to B. lycium (4.0%), and B. aristata (3.8%). Meanwhile, Srivastava et al. (2004) documented a higher berberine content in root of B. aristata (2.8%) compared with B. asiatica (2.4%) (Andola et al., 2010a). Seasonal variation of berberine concentration has been reported, e.g., the maximum yield of berberine for B. pseudumbellata was obtained in the summer harvest, and was 2.8% in the roots and 1.8% for the stem bark, contrary to that reported in the roots of B. aristata, where the berberine concentration (1.9%) is higher for the winter harvest (Rashmi et al., 2009). These variations may be caused to multiple factors, among which stand out: (i) the intraspecific differences, (ii) location and/or, (iii) the analytical techniques used. Table 2 gathers a synthesis of the main species containing berberine.

Extraction methods

Berberine, a quaternary protoberberine alkaloid (QPA) is one of the most widely distributed alkaloid of its class. Current studies suggest that isolation of the QPA alkaloids from their matrix can be performed using several methods. The principles behind these methods consist of the interconversion reaction between the protoberberine salt and the base. The salts are soluble in water, stable in acidic, and neutral media, while the base is soluble in organic solvents. Thus during the extraction procedure, the protoberberine salts are converted in their specific bases and further extracted in the organic solvents (Marek et al., 2003; Grycová et al., 2007).

In the case of berberine, the classical extraction techniques like maceration, percolation, Soxhlet, cold or hot continuous extraction are using different solvent systems like methanol, ethanol, chloroform, aqueous, and/or acidified mixtures. Berberine's sensitivity to light and heat is the major challenge for its extraction. Hence, exposure to high temperature and light could lead to berberine degradation and thus influencing its matrix recovery. In his study Babu et al. (2012) demonstrated that temperature represent a crucial factor in both extraction and drying treatments prior extraction. The yield of berberine content in C. fenestratum stem tissue samples was higher in case of samples dried under the constant shade with 4.6% weight/weight (w/w) as compared to samples dried in oven at 65°C (1.32% w/w) or sun drying (3.21% w/w). As well hot extraction procedure with methanol or ethanol at 50°C gave lower extraction yields when compared with methanol or ethanol cold extraction at −20°C. Thus, berberine content in the shade-dried samples was 4.6% (w/w) for methanolic cold extraction and 1.29% (w/w) for methanolic hot extraction (Babu et al., 2012).

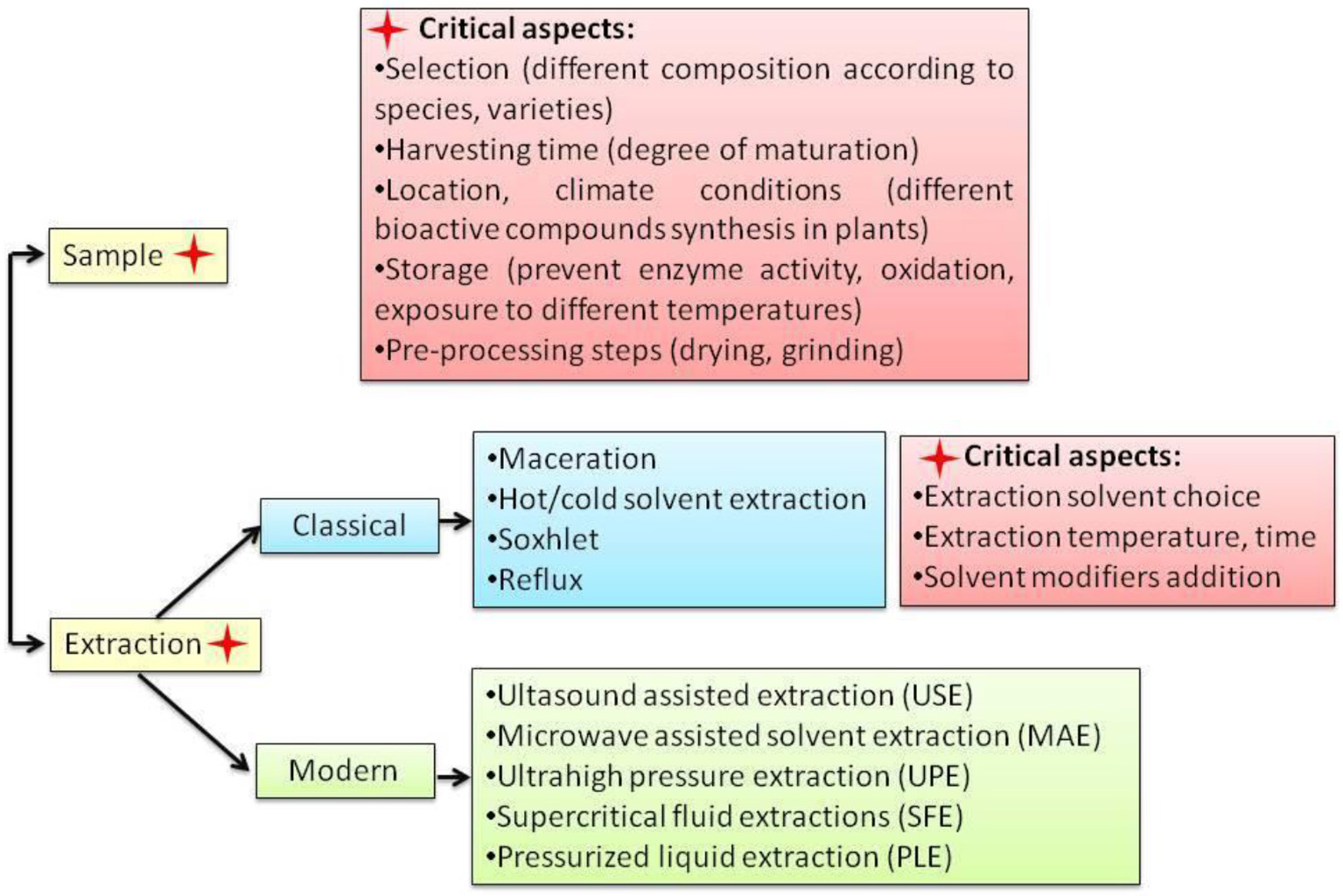

Along with extraction temperature, the choice of solvents is considered a critical step in berberine extraction as well (Figure 2). As seen in Table 3, methanol, ethanol, aqueous or acidified methanol or ethanol are the most used extraction solvents. The acidified solvents (usually with the addition of 0.5% of inorganic or organic acids) are used to combine with free base organic alkaloids and transform them in alkaloid salts with higher solubility (Teng and Choi, 2013). The effect of different inorganic acids like hydrochloric acid, phosphoric acid, nitric acid, and sulfuric acid as well as the effect of an organic acid like acetic acid were tested on berberine content and other alkaloids in rhizomes of Coptis chinensis Franch by Teng and Choi (2013). In this case, 0.34% phosphoric acid concentration was considered optimal. Moreover, when compared to other classical extraction techniques like reflux and Soxhlet extraction, the cold acid assisted extraction gave 1.1 times higher berberine yields.

Figure 2

Short view on berberine extraction methods.

Table 3

| Sample (weight) | Extraction method | Detection method | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dried stem powder Coscinium fenestratum (Gaertn.) (1 g) | Extraction solvents (ES): water, methanol–water (1:1. v/v), and methanol Sonication (15 min, room temperature) Centrifugation (2,800 rpm, 15 min) Filtration and evaporation Extracts resolubilization (methanol:water, 9:1 v/v) | HPLC - DAD Column: ODS, Chromolith, RP-18e,100 × 4.6 mm Mobile Phases: Methanol/Deionized Water (90:10, v/v) Flow: 0.5 mL/min, Temperature: 25°C UV Spectrophotometric Analysis | Akowuah et al., 2014 |

| C. fenestratum (Gaertn.) (10 g) | ES: methanol Hot extraction: sample refluxed with ES for 3 h Filtration and evaporation. Extracts resolubilization (methanol) | TLC Adsorbent: Silica Gel GF 254 Solvent system: n-Butanol: Ethyl acetate: Acetic acid (2.5:1.5:1, v/v/v) Detection: 254 and 366 nm | Arawwawala and Wickramaar, 2012 |

| Cold extraction: sample extraction with ES for 24 h Filtration and evaporation. Extracts resolubilization (methanol) | |||

| Dried C. fenestratum (0.1 g) | ES: absolute methanol Cold extraction: sample extraction at −20°C Hot extraction: water bath sample extraction at 50°C ES: absolute ethanol Cold extraction sample extraction at −20°C Hot extraction: water bath sample extraction at 50°C Samples centrifugation (10 min at 10°C after cooling down) Samples filtration | HPLC Column: C18, 250 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm Mobile Phases: Acetonitrile/0.1% Trifluro-acetic acid (50:50, v/v) Detection: 344 nm Flow: 0.8 mL/min | Babu et al., 2012 |

| C. fenestratum (1,000g) Capsules (containing 62.5 mg C. fenestratum) | ES: petroleum ether, chloroform, methanol (1L each) Soxhlet extraction: with each ES for 3 days at (30–40°C) ES: methanol (10 mL) Extraction for 1 h Filtration and evaporation Resolubilisation in methanol (5 mL) | HPLC Column: Luna C18, 150 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm, Phenomenex Mobile Phases: (A) Potassium dihydrogen phosphate (pH −2.5) and (B) Acetonitrile Detection: 220 nm Flow: 1 mL/min HPTLC Adsorbent: Silica Gel 60F 254 Solvent system: n-Butanol: Glacial acetic acid: Water (8:1:1, v/v/v) Detection: 350 nm for all measurements | Jayaprakasam and Ravi, 2014 |

| Tinospora cordifolia (Willd.), Tribulus terrestris (L.), Emblica officinalis (Gaertn.) (3 g) | ES: chloroform Dried sample trituration with ammonia solution Drying at room temperature Extraction with ES for 1h Chloroform phase extraction with 5% sulfuric acid (x 3) Basification of acid extract with sodium carbonate (pH −9) Extraction of basified solution with chloroform (X 3) Evaporation of chloroform phase (temperature under 50°C) Residue solubilization with methanol | UV-VIS UV absorbance: 348 nm | Joshi and Kanaki, 2013 |

| Cortex phellodendri (2 g) | Ultrahigh pressure extraction (UPE) Optimal parameters: ES: ethanol (69.1%), liquid-solid ratio−31.3, extracting pressure−243.30 MPa, extraction time−2 min | HPLC Column: Hypersil ODS C18, 250 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm Mobile Phases: (A) 0.3% triethanolamine aqueous solution (pH − 3.5) Detection: 265 nm Temperature: 30°C Flow: 1 mL/min | Guoping et al., 2012 |

| Rhizome of Coptis chinensis Franch (1 g) | Supercritical fluid extraction Extraction time: up to 3 h Temperature: 60°C Pressure: from 200 to 500 bar Flow-rate of carbon dioxide (gaseous state): 1 L/min Flow-rate of modifier: 0.4 mL/min. Organic solvent modifier systems: ethanol-modified supercritical carbon dioxide, methanol-modified supercritical carbon dioxide, 1,2-propanediol-modified supercritical carbon dioxide, 5% Tween 80 in methanol-modified supercritical carbon dioxide, 5% Tween in ethanol-modified supercritical carbon dioxide | HPLC Column: Diamonsil C18, 250 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm Mobile Phases: 33 mM Potassium dihydrogen phosphate : acetonitrile (70:30, v/v) Detection: 345 nm Flow: 1 mL/min | Liu et al., 2006 |

| Soxhlet extraction ES: hydrochloric acid: methanol (1: 100, v/v) Time: 8 h | |||

| Cortex pellodendri amurensis (1 g) | Ultrahigh pressure extraction ES: ethanol (50 %), liquid-solid ratio −30: 1, extracting pressure −400 MPa, extraction time −4 min, extraction temperaturte −40°C Ultrasonic extraction ES: 70% ethanol Sample soaking for 24 h in 40 ml ES Sonic extraction for 60 min at 30°C | HPLC- DAD Column: Daisopak SP-120-5-ODS_BP, 250 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm Mobile Phases: (A) acetonitrile and (B) phosphoric acid: water (0.7:100, v/v) Detection: 345 nm Temperature: 25°C Flow: 1 mL/min | Liu et al., 2013 |

| Heat reflux extraction ES: 70% ethanol Sample soaking for 24 h in 40 ml ES Sample extraction for 4 h at boiling state | |||

| Soxhlet extraction ES: 70% ethanol Sample soaking for 24 h in 40 ml ES Sample extraction: 4 h | |||

| Goldenseal (Hydrastis canadensis L.) (2, 5, 5 g) | Pressurized hot water extraction ES: water at 140°C, Optimal parameters: pressure: 50 bars and flow rate: 1 mL/min, Time: 15 min Reflux extraction ES: methanol (200 mL) Sonication: 4 h at 80°C Ultrasonic extraction ES: methanol (50 mL) Reflux: 6 h with continuous stirring | HPLC-DAD Column: Zorbax eclipse Plus C 18, 75 x 4.6 mm, 3.5 μm Mobile phases: (A) 0.1 % Formic Acid (pH 2.7) and (B) methanol Detection: 242 nm Temperature: 35°C Flow: 1 mL/min MS Detection: ESI (+) Capillary temperature: 200°C, Sheath gas: 80, Capillary voltage: 20 V, Tube lens voltage: 5V | Mokgadi et al., 2013 |

| Berberis aristata DC (1.5 g), Berberis aristata herb extract (0.1 g), Ayurvedic form (6 g) | Crude herb reflux extraction ES: methanol (100 mL) for 1 h in a water bath Filtratio Reextraction with ES (50 mL) for 30 min (× 2) Filtrates combination and concentration to 50 mL Herb extracts ultrasonic extraction ES: methanol (up to 10 mL) Sonication Filtration | HPLC Column: Zorbax ODS II, 250 x 4.6 mm, 5 μm Mobile phase: potassium hydrogen phosphate buffer (pH 2.5)/ acetonitrile Detection: 346 nm Temperature: 40°C Flow: 1 mL/min | Singh R. et al., 2010 |

| Ayrvedic form ultrasonic extraction ES: methanol (up to 25 mL) Sonication | |||

| Berberis aristata DC root | Soxhlet extraction ES: ethanol Berberine isolation Ethanolic extract concentration to obtain a syrup mass Dissolvation in hot water and filtration Acidification (36.5% w/v hydrochloric acid) Cool: ice bath - 30 min, overnight in refrigerator | HPTLC Stationary phase: precoated silica gel 60GF254 Mobile phases: n-butanol: glacial acetic acid: water (12:3:4 v/v/v) Temperature: 33 ± 5°C Detection: 350 nm | Patel, 2013 |

| Mahonia manipurensis (Takeda) stem bark (100 g) | Cold extraction ES: 80% methanol (1,000 mL) Stirring at room temperature Extract concentration | TLC Stationary phase: precoated silica gel G F254 Mobile phase: hexane: ethyl acetate: methanol (56:20:5) Fraction purification: positive test using Dragendroff's reagent Further analysis of purified fraction Mobile phase: chloroform: ethyl acetate: diethylamine: methanol: 20% ammonium hidroxide (6:24:1.5:6:0.3) | Pfoze et al., 2014 |

| HPLC Column: Water Symmetry C18, 250 x 4.6 mm, 5 μm Mobile phase: methanol/ formic acid buffer (0.1%, v/v) Detection: 346 nm Flow: 1 mL/min | |||

| UV-VIS UV spectra: 200–500 nm | |||

| ESI-MS | |||

| Coscinium fenestratum (100 g) | Maceration ES: 80% ethanol (500 ml), 160 h Shaken: 80 h (200 rpm), stand: 80 h Reextraction: 48 h, shaken: 24 h, stand: 24 h Combined extracts concentration Evaporation to dryness (dry extract) Resolubilisation in 80% ethanol (10 mg dry extract/mL) | TLC Stationary phase: Silica gel GF254 Mobile phase: ethyl acetate : butanol : formic acid : water (50:30:12:10); Detection: 366 nm | Rojsanga and Gritsanapan, 2005 |

| Argemone mexicana | Soxhlet extraction ES: methanol Evaporation to dryness Resolubilisation in methanol (known concentration) | HPTLC Stationary phase: precoated silica gel 60F254 Mobile phases: toluene: ethyl acetate (9:3, v/v). Detection: 266 nm | Samal, 2013 |

| Tinospora cordifolia (20 g) | Microwave assisted extraction (MAE) ES: 80% ethanol Irradiation power: 60%, Extraction time: 3 min Soxhlet extraction ES: ethanol, for 3 h Filtration Concentration | HPTLC Mobile phases: methanol: acetic acid: water (8: 1: 1, v/v/v). Detection: 366 nm | Satija et al., 2015 |

| Maceration ES: ethanol (200 mL), 7 days, occasional stirring | |||

| Berberis aristata, Berberis tinctoria (800 g) | Hot extraction ES: methanol (2.5 L) (X2) Extraction time: 3 h Temperature: 50°C Extract concentration under vacuum | HPLC Column: Unisphere C18, 150 x 4.6 mm, 5 μm Mobile phase: (A) 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid and (B) acetonitrile (60:40, v/v) Detection: 350 nm Temperature: 30°C Flow: 1 mL/min | Shigwan et al., 2013 |

| Coptis chinensis Franch. (1g) | Acid assisted extraction ES: several inorganic acids (hydrochloric acid, phosphoric acid, nitric acid, and sulfuric acid) and one organic acid (acetic acid) Extraction time:1–8 h, Acid concentrations: 0–1% Solvent to sample ratios: 20–60 mL/g Maceration at 25°C Filtration Dilution to 100 mL final volume | HPLC Column: XTerra C18, 250 x 4.6 mm Mobile phase: (A) acetonitrile and (B) 25 mmol/L potassium dihydrogen phosphate,(27:75, v/v) Detection: 345 nm Temperature: 30°C | Teng and Choi, 2013 |

| Soxhlet extraction ES: 50% ethanol (100 mL), 4 h at 70°C Extract evaporation to dryness Resolubilization in ES (up to 100 mL final volume) | |||

| Heating reflux extraction ES: 50% ethanol Soaked for 1 h Extraction: 4 h at 70°C (heated water bath) Filtration Dilution (up to 100 mL final volume) | |||

| Rabbit plasma (100 μl) | Mixing 100 μl sample with 3% formic acid in acetonitrile (200 μl) Vortex: 30 s Centrifugation: 10 min at 4°C Evaporation of supernatant: under nitrogen stream at 40°C | LC-ESI-MS HPLC system Column: Capcell Pakc18 MG, 100 × 2.1 mm, 5 μm with Security Guard C18, 4 × 2 mm, 5 μm Mobile Phases: (A) 0.4% formic acid solution and (B) 0.2 % formic acid solution in methanol (60:40, v/v) | Liu et al., 2011 |

| Residue solubilization: in 100 μl of 20% methanol | Temperature: 25°C Flow: 0.4 mL/min MS detection: Source: ESI (+) Quantification: MRM mode | ||

| Rat plasma | Solid phase extraction (SPE) Cartridges: Oasis HLB (1 cc, 30 mg) Pre-conditioning: 2 mL methanol Equilibrtating: | UPLC-MS/MS UPLC system Column: 120 EC-C18, 50 × 4.6 mm, 2.7 μm with Security Guard C18, 4 × 2 mm, 5 μm Mobile Phases: (A) 10 mM ammonium acetate in water (pH- 4.5) and (B) acetonitrile Temperature: 35°C Flow: 0.8 mL/min MS detection: Source: ESI (+) Quantification: MRM mode | Liu M. et al., 2015 |

| Rat plasma Rat tissue | Rat plasma ES: methanol Mixing sample (200 μl) with internal standard (40 μl) and ES (560 μl) Vortex: 20 s Centrifugation: 10 min, 12,000x g Filtration | UPLC-MS/MS UPLC system Column: Acquity BEH C18, 50 × 2.1 mm, 1.7 μm Mobile Phases: (A) acetonitrile and (B) formic acid: water (0.1:99.9, v/v) Flow: 0.25 mL/min MS detection: Source: ESI (+) Quantification: MRM mode | Wang et al., 2016 |

| Rat tissue Grinding: 3 mL physiological saline with 600 mg tissue Centrifugation: 10 min, 12,000x g, 4°C Mixing supernatant (200 μl) with internal standard (40 μl) and ES (560 μl) Vortex: 20 s Centrifugation: 10 min, 12,000x g Filtration | |||

| Rat plasma | Evaporation of 10 ul IS in the working tube Mixing sample (200 μl) with internal evaporated standard Vortex: 1 min Mixing sample with 10 μl 1% formic acid and 200 μl acetone Vortex: 2 min Centrifugation: 10 min, 10,000 rpm Mixing supernatant with 200 μl methanol Vortexing, centrifugation Mixing supernatant wit 400 μl acetonitrile Vortexing, centrifugation Evaporation to dryness (37°C, under nitrogen stream) Resolubilization in methanol | LC-MS/MS LC system Column: Zorbax Eclipse XDB-C18, 150 × 2.1 mm, 3.5 μm Mobile Phases: (A) acetonitrile and (B) water with 1% acetic acid and 0.001 mol/L ammonium acetate Flow: 0.2 mL/min MS detection: Source: ESI (+) Quantification: MRM mode | Xu et al., 2015 |

| Rat plasma | ES: 90% methanol Mixing sample (100 μl) with internal standard (10 μl) and ES (100 μl) Vortex: 1 min Centrifugation: 10 min, 12,000 rpm, 4°C Supernatant evaporation to dryness under nitrogen stream Resolubilization (100 μl ES) | UPLC-MS/MS UPLC system Column: Acquity UPLC BEH C18, 50 × 2.1 mm, 1.7 μm Mobile Phases: (A) formic acid: water (0.1:99.9, v/v) and (B) acetonitrile Flow: 0.4 mL/min MS detection: Source: ESI Quantification: MRM mode | Yang et al., 2017 |

Extraction and detection methods for berberine in different herbal and biological matrixes.

Large solvent volumes and long extraction time represent other drawbacks of conventional extraction methods (Mokgadi et al., 2013). For example, Rojsanga and Gritsanapan (2005) used maceration process to extract 100 g of C. fenestratum plant material with a total volume of 3,200 mL solvent (80% ethanol) over a period of 416 h. Furthermore, in a different study, Rojsanga et al. (2006) used several classical extraction techniques like maceration, percolation, and Soxhlet extraction to extract the berberine from C. fenestratum stems. This time even if the extracted plant material was in a lower amount than the previous study (30 vs. 100 g), large solvent volumes (2,000 mL for maceration, 5,000 mL for percolation, and 600 mL for Soxhlet extraction) over long time periods (7 days for maceration and 72 h for Soxhlet extraction) were employed (Rojsanga and Gritsanapan, 2005; Rojsanga et al., 2006).

Large solvent volumes are characteristic for other conventional methods too. Shigwan et al. (2013) extracted berberine from Berberis aristata and B. tinctoria powdered stem bark (800 g) using hot extraction (50°C for 3 h) with 2,500 mL methanol (Shigwan et al., 2013).

Even though conventional methods are widely used in berberine extraction, a number of other different methods have been developed lately. This led to an improved extraction efficiency, a decreased extraction time and solvents' volumes used in the extraction. Thus, ultrasound assisted solvent extraction (USE), microwave-assisted solvent extraction (MAE), ultrahigh pressure extraction (UPE), and supercritical fluid extractions (SFE), pressurized liquid extraction (PLE) have been successfully used as alternative extraction techniques with better results when compared with classical extraction methods.

Ultrasonically and microwave-assisted extraction are considered green, simple, efficient, and inexpensive techniques (Alupului et al., 2009).

Teng and Choi (2013) extracted berberine from Rhizome coptidis by optimized USE. Using response surface methodology, they identified that the optimal extraction conditions were 59% ethanol concentration, at 66.22°C within 46.57 min. A decrease in the extraction time (39.81 min) was obtained by Chang (2013). He used the combination of ionic liquids solutions as green solvents with USE to extract berberine from Coptis chinensis in order to apply an environmentally friendly approach (Chang, 2013). Moreover, in their study, Xu et al. (2017) compared several extraction tehniques like USE, distillation, and Soxhlet extraction in order to establish an high-efficient method for phellodendrine, berberine, and palmatine extraction from fresh Phellodendron bark (Cortex phellodendri). In the case of berberine, the combination of simple or acidified solvent (water, ethanol, and methanol) with the adjustment of the specific setting characteristics to each extraction type enabled them to determine the highest extraction yield. They concluded that the use of USE and hydrochloric acid-acidified methanol were the most efficient in extracting berberine. The USE extraction yield was significantly higher when compared to distillation and Soxhlet extraction, with values of ~100 mg/g toward 50 and 40 mg/g berberine, respectively (Xu et al., 2017).

The important reduction in organic solvent and extraction time determined the increasing interest in MAE, too. Lately, MAE was used as a green and cost-effective alternative to conventional methods. Using central composite design, Satija et al. (2015) successfully optimized the MAE parameters in terms of irradiation power, time, and solvent concentration to extract berberine form Tinospora cardifolia. They compared two classical extraction techniques like maceration and Soxhlet extraction with MAE under optimized conditions (60% irradiation power, 80% ethanol concentration, and 3 min extraction time). The results showed that MAE extraction had the highest yield of berberine content with 1.66% (w/w) while Soxhlet and maceration had 1.04 and 0.28% (w/w), respectively. Their study is emphasizing the dramatic time reduction in case of MAE (3 min) when compared with Soxhlet extraction (3 h) and maceration (7 days) together with solvent and energy consumption (Satija et al., 2015).

Another novel extraction technique considered to be environmentally friendly is UPE. The interest toward this extraction technique is increasing because it presents several advantages toward classical extraction techniques like increased extraction yields, higher quality of extracts, less extraction time, and decreased solvent consumption (Xi, 2015). These are achieved at room temperature by applying different pressure levels (from 100 to 600 MPa) between the interior (higher values) and the exterior of cells (lower values) in order to facilitate the transfer of the bioactive compounds through the plant matrices in the extraction solvent (Liu et al., 2006, 2013). In the study regarding berberine content in Cortex phellodendri, Guoping et al. (2012) made a comparison between UPE, MAE, USE, and heat reflux extraction techniques. They observed that the higher extraction yield and the lower extraction time was obtained in case of UPE with 7.7 mg/g and 2 min extraction time toward reflux, USE and MAE with 5.35 mg/g and 2 h, 5.61 mg/g and 1 h. and 6 mg/g and 15 min, respectively (Guoping et al., 2012).

Super critical fluid extraction is another environmentally friendly efficient technique used in phytochemical extraction. Because the extraction is performed in the absence of light and oxygen, the degradation of bioactive compounds is reduced. Also, the inert and non-toxic carbon dioxide used as a main extraction solvent in combination with various modifiers (e.g., methanol) and surfactants (e.g., Tween 80) at lower temperatures and relatively low pressure, allows the efficient extraction of bioactive compounds (Liu et al., 2006; Farías-Campomanes et al., 2015). In case of berberine extraction from the powdered rhizome of Coptis chinensis Franch, the highest recovery of berberine was obtained when 1,2-propanediol was used as a modifier of supercritical CO2 (Liu et al., 2006).

Pressurized liquid extraction, also known as pressurized fluid extraction, pressurized solvent extraction, and accelerated solvent extraction (ASE) is considered a green technology used for compounds extraction from plants (Mustafa and Turner, 2011). Compared with conventional methods, PLE increases the extraction yield, decreases time and solvent consumption, and protects sensitive compounds. In their study, Schieffer and Pfeiffer (2001) compared different extraction techniques like PLE, multiple USE, single USE, and Soxhlet extraction in order to extract berberine from goldenseal (Hydrastis canadensis). When compared in terms of extraction yield the results are comparable, ~42 mg/g berberine, except single USE with slightly lower content (37 mg/g berberine). Big differences were observed in the extraction time, PLE requiring only 30 min for a single sample extraction compared to 2 h for multiple extraction techniques or 6 h for Soxhlet extraction (Schieffer and Pfeiffer, 2001).

When referring to berberine extraction from biological samples, the extraction process is relatively simple and involves several steps like sample mixing with extraction solvents (e.g., methanol, acetone, acetonitrile), vortex, centrifugation followed by supernatant evaporation under nitrogen stream (Table 3). Other extraction techniques like solid phase extraction (SPE) can also be applied.

Analytical techniques

After extraction and purification, the separation and quantification of berberine are commonly resolved by chromatographic methods. According to literature studies, berberine determination in plants was predominantly performed using methods like UV spectrophotometry (Joshi and Kanaki, 2013), HPLC (Babu et al., 2012; Akowuah et al., 2014), HPTLC and TLC (Rojsanga and Gritsanapan, 2005; Arawwawala and Wickramaar, 2012; Samal, 2013), capillary electrophoresis (Du and Wang, 2010), while berberine content in biological fluids was mainly achieved by using LC-MS (Deng et al., 2008; Feng et al., 2010), UPLC-MS (Liu M. et al., 2015; Liu L. et al., 2016), UHPLC/Q-TOF-MS (Wu et al., 2015).

UV-Vis spectrophotometry can be considered as one of the most rapid detection methods for berberine quantitative analysis from plant extracts. Based on the Beer-Lambert law, berberine concentration can be determined according to its absorption maxima at 348 nm. Joshi and Kanaki (2013) quantified berberine in Rasayana churna samples in the range of 2–20 μg/mL, the interference with other compounds being avoided by the specific isolation of the alkaloid fraction (Joshi and Kanaki, 2013).

Next, high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) is a versatile, robust, and widely used technique for the qualitative and quantitative analysis of natural products (Sasidharan et al., 2011). This approach is widely used in berberine identification and quantification. Generally, the choices of stationary phase in berberine separation are variants of C18-based silica column (Table 3) with a mobile phase consisting of simple or acidified solvents like water, methanol, or acetonitrile, used as such or in combination with phosphate buffers. Normally, the identification and separation of berberine can be accomplished using either isocratic or gradient elution system. Berberine identification is further accomplished using high sensitivity UV or DAD (diode array detectors) detectors. For example, Shigwan et al. (2013) developed in his study a reverse phase HPLC method with photodiode array detection (PDA) to quantify berberine from Berberis aristata and B. tinctoria. They used a Unisphere-C18 column (5 μm, 4.6 × 150 mm) with an isocratic gradient of acidified water (with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid) and acetonitrile (60:40, v/v) to elute berberine within 5 min. The developed method was reproducible, validated, precise, and specific for berberine quantification (with a concentration range between 0.2 and 150 μg/mL; Shigwan et al., 2013).

Two other commonly used techniques in berberine quantification are thin layer chromatography (TLC) and high performance thin layer chromatography (HTPLC). Sometimes, these methods are preferred over HPLC, offering the possibility of running several samples simultaneously along with the use of small amount of both samples and mobile phases (Samal, 2013). For these reasons, Samal (2013) used an HPTLC method to quantify berberine from A. mexicana L. using toluene and ethyl acetate (9:3, v/v) as mobile phases, and a silica gel plate as stationary phase, they developed a simple, rapid, and cost-effective method for berberine quantification. The LOD (0.120 μg) and LOQ (0.362 μg) of the method are in accordance with high-quality requirements.

Following the same principles (small sample volume, high separation efficiency, and short analysis time), capillary electrophoresis (CE) was successfully used in berberine analysis. Du and Wang (2010) used CE with end-column electrochemiluminescence (ECL) detection for berberine analysis in both tablets and Rhizoma coptidis. Using a 4 min analysis time, a small sample volume (3.3 nL) and a LOD of (5 × 10−9 g/mL), the developed method proved to be highly sensitive and with good resolution (Du and Wang, 2010).

Besides UV, HPLC, HTPLC, TLC, and CE, other detection methods like liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (LC/MS) are currently employed to quantify berberine in biological fluids. Generally, it is considered a powerful technique for the analysis of complex samples because it offers rapid and accurate information about the structural composition of the compounds, especially when tandem mass spectrometry (MSn) is applied. For example, Xu et al. (2015) developed a sensitive an accurate LC-MS/MS method to determine berberine and other seven components in rat plasma using multiple reactions monitoring (MRM) mode. Compounds separation was optimized using six different types of reverse-phase columns, and two different mobile phases (methanol–water and acetonitrile–water with different additives). Additives like formic acid, acetic acid, and ammonium acetate were added in different concentrations as follows: 0.1, 0.5, 1, and 2% for formic acid, 0.1, 0.5, 1, and 2% for acetic acid and 0.0001, 0.001, 0.01 mol/L for ammonium acetate. The method was also tested in terms of specificity, linearity, lower limit of quantification (LLOQ), precision, accuracy, and stability (Xu et al., 2015).

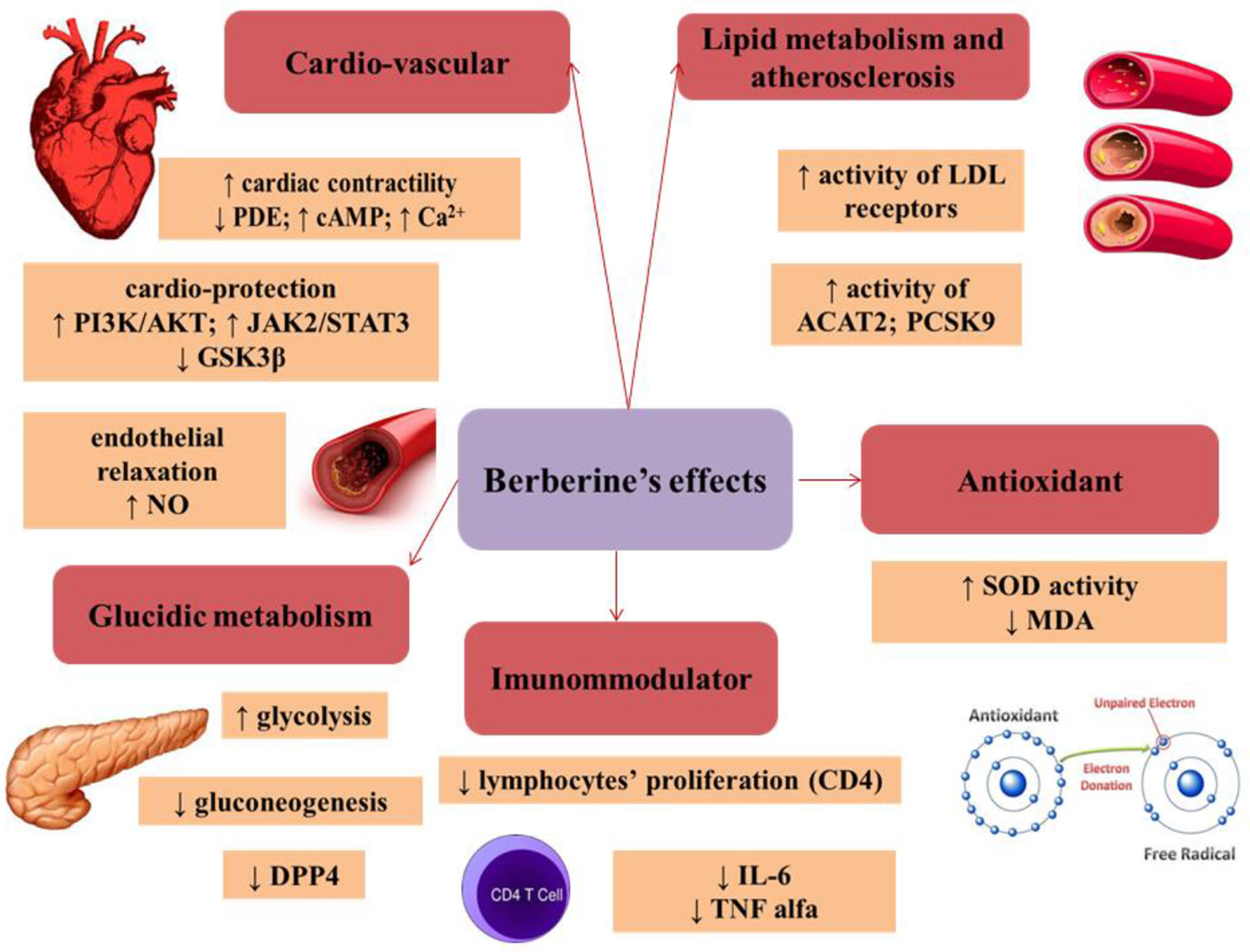

Antioxidant effect

Under normal conditions, the body maintains a balance between the antioxidant and pro-oxidant agents (reactive oxygen species—ROS and reactive nitrogen species—RNS; Rahal et al., 2014).

The imbalance between pro and antioxidants occurs in case of increased oxidative stress (Bhattacharyya et al., 2014).

The oxidative stress builds up through several mechanisms: an increase in the production of reactive species, a decrease in the levels of enzymes involved in blocking the actions of pro-oxidant compounds, and/or the decrease in free radical scavengers (Pilch et al., 2014).

An experimental study demonstrated the effect of berberine on lipid peroxidation after inducing chemical carcinogenesis in small animals (rats). An increase in LPO (lipid peroxidation) was observed after carcinogenesis induction, but also its significant reversal after berberine administration (30 mg/kg). Berberine shows therefore at least partial antioxidant properties, due to its effect on lipid peroxidation (Thirupurasundari et al., 2009).

Other mechanisms involved in the antioxidant role of berberine are: ROS/RNS scavenging, binding of metals leading to the transformation/oxidation of certain substances, free-oxygen removal, reducing the destructiveness of superoxide ions and nitric oxide, or increasing the antioxidant effect of some endogenous substances. The antioxidant effect of berberine was comparable with that of vitamin C, a highly-potent antioxidant (Shirwaikar et al., 2006; Ahmed et al., 2015).

The increase in blood sugar leads to oxidative stress not by generating oxygen reactive species but by impairing the antioxidant mechanisms. Administration of berberine to rats with diabetes mellitus increased the SOD (superoxide dismutase) activity and decreased the MDA (malondialdehyde) level (marker of lipid peroxidation). This antioxidant effect of berberine could explain the renal function improvement in diabetic nephropathy (Liu et al., 2008b).

The oxidative stress plays an important role in the pathogenesis of many diseases. The beneficial effect of berberine is presumed to reside mostly in its antioxidant role.

Cardiovascular effects of berberine

Effect on cardiac contractility

The beneficial effect of berberine in cardiac failure was demonstrated in a study on 51 patients diagnosed with NYHA (New York Heart Association) III/IV cardiac failure with low left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and premature ventricular contractions and/or ventricular tachycardia. These patients received tablets containing 1.2 g berberine/day, together with conventional therapy (diuretics, ACEI—angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors, digoxin, nitrates) for 2 weeks. An increase in LVEF was observed in all patients after this period, but also a decrease in the frequency and complexity of premature ventricular contractions. The magnitude of the beneficial effect was in direct proportion with the plasma concentration of berberine (Zeng, 1999).

The cardioprotective effect during ischemia

Berberine can provide cardio-protection in ischemic conditions by playing various roles at different levels: modulation of AMPK (AMP—activated kinase) activity, AKT (protein kinase B) phosphorylation, modulation of the JAK/STAT (Janus kinase/signal transducers and activators of transcription) pathway and of GSK3β (glycogen synthase kinase 3β; Chang et al., 2016). AMPK is an important enzyme playing an essential role in cellular metabolism and offering protection in ischemic conditions by adjusting the carbohydrate and lipid metabolism, the function of cell organelles (mitochondria, endoplasmic reticulum) and the apoptosis (Zaha et al., 2016).

Berberine activates the PI3K (phosphoinositide 3-kinase)/AKT pathway which is considered a compensatory mechanism limiting the pro-inflammatory processes and apoptotic events in the presence of aggressive factors. The activation of this pathway is associated with a reduction of the ischemic injury through the modulation of the TLR4 (toll-like receptor 4)-mediated signal transduction (Hua et al., 2007).

Several supporting data indicate that the JAK2/STAT3 signaling plays an important role in cardioprotection against ischemia-reperfusion injury (Mascareno et al., 2001).

GSK3β is a serine/threonine protein-kinase, an enzyme involved in reactions associated to important processes at the cellular level: metabolization, differentiation, proliferation, and apoptosis. Berberine inhibits this kinase, thereby exercising its cardioprotective effect (Park et al., 2014).

Effects on the endothelium

Berberine induces endothelial relaxation by increasing NO production from arginine through the activity of eNOS (endothelial nitric oxide synthase) which is considered a key element in the vasodilation process. Besides increasing the NO level, it also up-regulates eNOS mRNA. Furthermore, berberine facilitates the phosphorylation of eNOS and its coupling to HSP 90 (heat shock proteins), which consequently increases NO production (Wang et al., 2009).

Moreover, berberine reduces endothelial contraction by reducing COX-2 expression. Any imbalance in COX 1 or 2 activity may alter the ratio between prothrombotic/antithrombotic and vasodilator/vasoconstrictor effects (Liu L. et al., 2015).

The beneficial effect of berberine on the TNFα-induced endothelial contraction was also recorded, as well as an increase in the level of PI3K/AKT/eNOS mRNA (Xiao et al., 2014).

The role of berberine in atherosclerosis

Atherogenesis is a consequence of high blood lipid levels and is associated with inflammatory changes in the vascular wall. Berberine interferes with this process by up-regulating the expression of SIRT1 (silent information regulator T1) and by inhibiting the expression of PPARγ (peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ). SIRT1 is a NAD-dependent deacetylase. The SIRT1 enzyme has many targets (PPARγ, p53), all playing different roles in atherogenesis (Chi et al., 2014).

The role of berberine in lipid metabolism

The effects of berberine on lipid metabolism are also the consequence of its effects on LDL cholesterol receptors. On one hand, these receptors are stabilized by an extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)-dependent pathway, and on the other, berberine increases the activity of LDL receptors through the JNK pathway (Cicero and Ertek, 2009).

Moreover, berberine has an effect on ACAT (cholesterol acyltransferases), a class of enzymes that transform cholesterol into esters, thus playing an essential role in maintaining cholesterol homeostasis in different tissues. There are two types of ACAT enzymes, ACAT1, and ACAT2. ACAT1 is a ubiquitous enzyme, while ACAT2 can be found only in hepatic cells and enterocytes. Berberine influences the activity of ACAT2 without an effect on ACAT1, therefore reducing the intestinal absorption of cholesterol and decreasing its plasmatic level (Chang et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2014).

The hypolipidemic effect of berberine is also a result of its action on PCSK9 (proprotein convertase subtilisin kexin 9). This enzyme can attach itself to LDL receptors, leading to a decrease in LDL metabolization and an increase in its blood level (Xiao et al., 2012).

In a clinical trial, 63 patients with dyslipidemia were randomly divided in three groups. The first group was treated with berberine (1,000 mg/day), the second with simvastatin (20 mg/day) and the third with a combination of berberine and simvastatin. The authors reported a 23.8% reduction in LDL-C levels in patients treated with berberine, a 14.3% reduction in those treated with simvastatin and a 31.8% LDL-C reduction in the group treated with both simvastatin and berberine. This result demonstrates that berberine can be used alone or in association with simvastatin in the treatment of dyslipidemia (Kong et al., 2008).

The role of berberine in glucose metabolism

Many studies demonstrated that berberine lowers blood sugar, through the following mechanisms:

- Inhibition of mitochondrial glucose oxidation and stimulation of glycolysis, and subsequently increased glucose metabolization (Yin et al., 2008a).

- Decreased ATP level through the inhibition of mitochondrial function in the liver, which may be the probable explanation of gluconeogenesis inhibition by berberine (Xia et al., 2011).

- Inhibition of DPP 4 (dipeptidyl peptidase-4), a ubiquitous serine protease responsible for cleaving certain peptides, such as the incretins GLP1 (glucagon-like peptide-1) and GIP (gastric inhibitory polypeptide); their role is to raise the insulin level in the context of hyperglycemia. The DPP4 inhibition will prolong the duration of action for these peptides, therefore improving overall glucose tolerance (Al-masri et al., 2009; Seino et al., 2010).

Berberine has a beneficial effect in improving insulin resistance and glucose utilization in tissues by lowering the lipid (especially triglyceride) and plasma free fatty acids levels (Chen et al., 2011).

The effect of berberine (1,500 mg day) on glucose metabolism was also demonstrated in a pilot study enrolling 84 patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. The effect, including on HbA1c, was comparable to that of metformin (1,500 mg/day), one of the most widely used hypoglycemic drugs. In addition, berberine has a favorable influence on the lipid profile, unlike metformin, which has barely any effect (Yin et al., 2008b).

Hepatoprotective effect of berberine

The hepatoprotective effect of berberine was demonstrated on lab animals (mice), in which hepatotoxicity was induced by doxorubicin. Pretreatment with berberine significantly reduced both functional hepatic tests and histological damage (inflammatory cellular infiltrate, hepatocyte necrosis; Zhao et al., 2012).

The mechanism by which berberine reduces hepatotoxicity was also studied on CCl4 (carbon tetrachloride)-induced hepatotoxicity. Berberine lowers the oxidative and nitrosamine stress and also modulates the inflammatory response in the liver, with favorable effects on the changes occurring in the liver. Berberine prevents the decrease in SOD activity and the increase in lipid peroxidation and contributes to the reduction in TNF-α, COX-2, and iNOS (inducible nitric oxide synthase) levels. The decrease in transaminase levels supports the hypothesis according to which berberine helps maintain the integrity of the hepatocellular membrane (Domitrović et al., 2011).

Nephroprotective effect of berberine