- 1Institute of Biology and Biotechnology, University of Rzeszów, Rzeszów, Poland

- 2Institute for Adriatic Crops and Karst Reclamation, Split, Croatia

- 3Institute for Marine and Coastal Research, University of Dubrovnik, Dubrovnik, Croatia

- 4Independent Researcher, Korčula, Croatia

- 5Department of Agricultural Botany, Faculty of Agriculture, University of Zagreb, Zagreb, Croatia

The Adriatic islands in Croatia, usually divided into two archipelagos – the Kvarner and Dalmatian islands – is one of the largest groups of islands in Europe. Over 40 islands are still inhabited. Unfortunately the traditional use of medicinal plants was never properly documented there. Our data comes from 343 interviews carried out in 36 islands, including the 15 largest islands of the archipelago. The medicinal plants are mainly used to make herbal infusions or decoctions, occasionally medicinal liqueurs, syrups, compresses, or juices squeezed out of raw plants. We recorded the use of 146 taxa, among them 131 with at least one medicinal purpose and 15 only for tea. The frequency curve of use is relatively steep – several plants are used very frequently and most are reported only by one or two informants, which can be explained both by the large geographical spread of the area, and even more so by the devolution of local knowledge and disappearance of gathering practices due to specialization in tourism, modernization and depopulation. Most of the gathered plants already occur in ancient and medieval herbals and are a part of the pan-Mediterranean pharmacopoeia.

Introduction

The view that contemporary folk knowledge about medicinal plants in Europe stems mainly from older herbals and contains little indigenous ancient knowledge was first expressed by Józef Rostafiński at the end of the 19th century (Köhler, 2015). Similar reductionist statements have appeared recently (Leonti, 2011). They are however counterbalanced by those who try to document the ethnomedical knowledge for reasons other than only finding new medicinal species. For example, the use of medicinal plants is entwined with issues such as the protection of rare plants and their overharvesting (Barata et al., 2016; Grigoriadou et al., 2020; Papageorgiou et al., 2020). The cultural aspects of healing with the use of herbs are also important and have been summarized by Quave et al. (2012). Plants are not a mere collection of phytochemicals but are set in traditional practices. They have stories and magical meanings attached to them, which can make it difficult to draw the line between ritual and medicinal use (Moerman, 1979; Heinrich, 2000). For example, in Poland, plants are usually blessed on certain occasions and later used for fumigation both in cases of obvious illness easily classified by biomedical science, folk illness (like “fright”), or sheerly to deter bad luck or “evil” forces (Łuczaj, 2012). Nowadays medicinal or herbal tea plants are often collected to “connect to nature” (Grasser et al., 2012). Another broadly discussed issue is the continuum of food and medicine (e.g., Pieroni and Price, 2006; Etkin, 2008). Investigating local uses of plants is also important in the light of growing medical pluralism in Europe (Uibu, 2020).

The study of locally used medicinal plants in the Balkans started with a paper by Leopold Glück, a pharmacist from Sarajevo (Glück, 1892). In recent years a lot of effort was put into the documentation of ethnomedicinal practices in the mainland Balkan Peninsula, especially in remote mountainous areas (Pieroni and Quave, 2014). Such research was carried out in all Balkan countries, including Slovenia (Lumpert and Kreft, 2017; Povšnar et al., 2017; Mattalia et al., 2020); Bosnia-Herzegovina (Šarić-Kundalić et al., 2009; Šarić-Kundalić et al., 2010; Šarić-Kundalić et al., 2011; Ferrier et al., 2015), Serbia (Pieroni et al., 2011; Šavikin et al., 2013; Zlatković et al., 2014; Jarić et al., 2015; Živković et al., 2020), Kosovo (Mustafa et al., 2012; Mustafa et al., 2020); Northern Macedonia (Pieroni et al., 2013; Rexhepi et al., 2013), Greece (Tsioutsiou et al., 2019), Montenegro (Menković et al., 2014), Albania (Pieroni, 2008; Pieroni et al., 2015) and Bulgaria (Ivancheva and Stantcheva, 2000; Nedelcheva and Dogan, 2015). Field research concerning the traditional use of medicinal plants was also carried out in mainland Croatia (Pieroni et al., 2003; Pieroni and Giusti, 2008; Vitasović-Kosić et al., 2017; Varga et al., 2019; Žuna Pfeiffer et al., 2020) but was lacking in the islands. In general, such research in the islands of the eastern part of the Mediterranean Sea has been somewhat neglected. Only Axiotis et al. (2018) studied medicinal plants used in the eastern part of the Egean archipelago of Greece (and found 108 species of plants used there medicinally), Papageorgiou et al. (2020) studied Lemnos, and Bulut (2016) – Marmara Island off the coast of Istanbul.

Previous research on the documentation of traditional use of medicinal plants on Croatian islands is only restricted to a few small ethnographic notes, either listing a few names of medicinal plants on Krk (Žic, 1900) and Korčula (Baničević, 2000), or, in the case of Šolta, mixing local names and local uses with uses from handbooks (Sule, 2010). Several published (printed) herbals and herbal manuscripts have been produced on the territory of present-day Croatia since 1603. For a list and overview, seeKrnjak (2019) and Kujundžić (2020). However, none of these sources were written on the islands.

Islands have been of great importance in developing ecological and evolutionary concepts but are little studied by ethnobotanists (Łuczaj et al., 2019a; Łuczaj et al., 2019b). The main model explaining biological diversity on islands is the so-called island biogeography theory formulated by MacArthur and Wilson (1967). It has only been tested once in our previous publication on the use of wild vegetables in the same study area (Łuczaj et al., 2019a). The results of this study suggested that the model has little application to ethnobotany of wild vegetables due to greater complexity and fuzziness of knowledge about plants compared to merely biogeographical species distributions of plants or animals. However, we think that it should be tested on more datasets to draw more general conclusions.

One may also wonder to what extend islands tend to preserve more knowledge than the mainland due to a certain degree of population isolation or, quite the contrary, to what extent their pharmacopoeias are degraded due to the effects of island biogeography (such as local knowledge or useful species endangered by dying out on small islands). We may also question whether the islands of the Mediterranean have been isolated at all. In the past, sea transport was very important and often more efficient than land routes, which does not change the fact that Croatian island human populations show an extremely high level of inbreeding (Łuczaj et al., 2019a). In our ethnobotanical research concerning wild vegetables in the Adriatic islands we observed only very weak island biogeography effects and a general geographical trend of decreasing numbers of the species used from Kvarner in the west to eastern Dalmatian islands (Łuczaj et al., 2019a). In the case of plants used to flavor alcoholic drinks, this northwest to southeast pattern was not visible (Łuczaj et al., 2019b). In both studies we found some locally used species with their traditions of use restricted to one or two islands.

In view of the aforementioned phenomena, the aim of our study was to:

1. Record which taxa are used in the local pharmacopoeias in the islands.

2. Establish if such variables as island size, population size, flora or its isolation are correlated with the number of species used.

We formulated a hypothesis that the length of the total medicinal plant list per island, as well as the mean number of species per informant is positively correlated with:

1. The number of species reported in the floras of particular islands. The link between the flora and plant use is obvious: the more species available the more likely it is that more species are used.

2. The area of the island. A larger area within which interviews were carried out meant a larger chance for different species to be found as well as a smaller similarity in village traditions due to larger physical distance between villages.

3. The number of inhabitants. The more people live on the island, the more exchange of knowledge is likely to happen and there are more knowledge holders.

4. The proximity of mainland (i.e., is negatively correlated with the distance from the mainland of Croatia). We assumed that in less isolated islands, whose inhabitants have more social contacts with the mainland, there is more opportunity for the exchange of knowledge.

Hypotheses no. two and four directly test the island biogeography theory and no. one and three result from it indirectly.

Materials and Methods

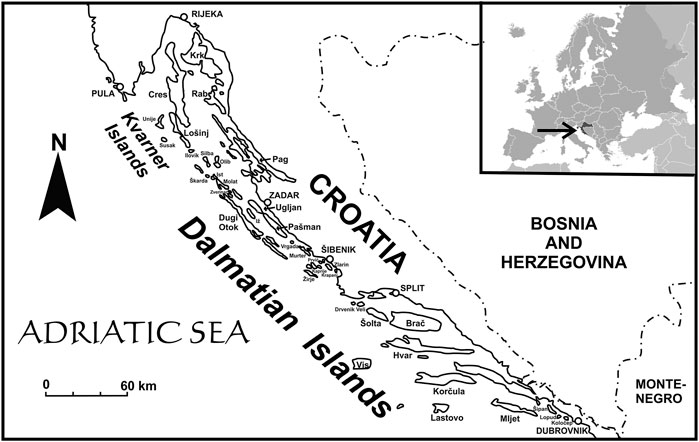

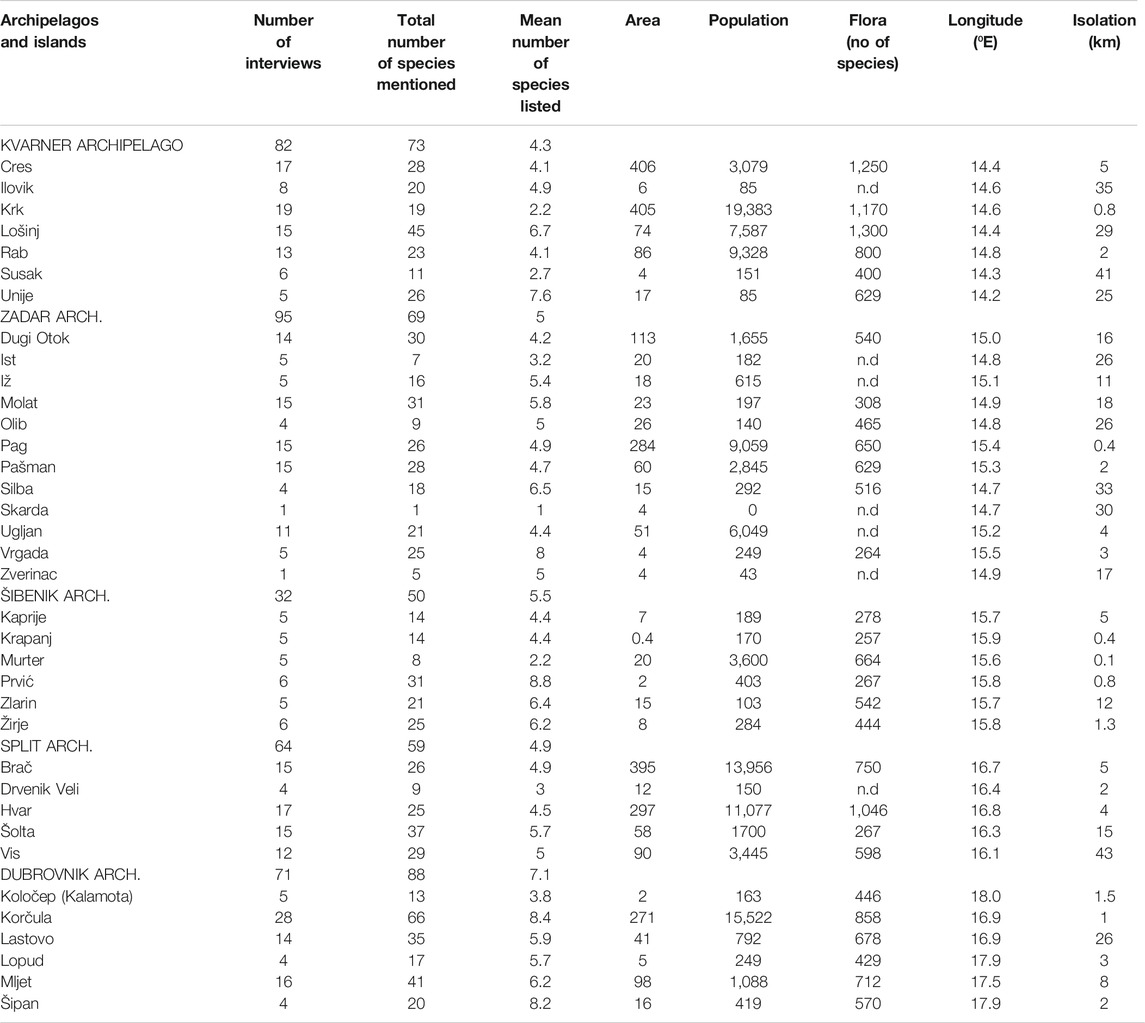

The study is part of a larger project on the ethnobotany of the Adriatic islands, from which only data about wild vegetables and plants used to flavor alcoholic drinks have been published so far (Łuczaj et al., 2019a; Łuczaj et al., 2019b). The research was performed between 2013 and 2018, with most interviews carried out in 2016 and 2017. We asked several questions about plant uses (wild edibles, tools, etc.). One of the questions behind these studies concerned the identification of plants that were used medicinally by the respondents or by their relatives in the past. The data in the spreadsheet come from 343 interviews with single people, couples, or rarely groups of a few neighbors. The mean age of respondents was 69 (median 70, minimum 24, maximum 96, 62% were female, 38% male). There are 47 inhabited islands in Croatia. However, some of them are only inhabited in summer, by one person or family, or by newcomers. We managed to interview people from 36 islands, including the fifteen largest islands, each with an area above 40 square km (Figure 1 and Table 1).

The study follows the guidelines of best practices in ethnopharmacological research outlined by Heinrich et al. (2018). We applied the typical methods of ethnobotany: in-depth semi-structured interviews starting from freelisting, and supplemented, if possible, by walks around the places where the respondents gathered plants and could identify the supplied names. Most informants were recommended locally as “those who name/gather plants”. Some informants were encountered directly in the fields or gardens. The interviews were performed in Croatian, the native language of the inhabitants. All the interviewees declare themselves as Croats and speak this language as their first language, apart from a few interviewees from Cres, who use Italian and Croat interchangeably. All the respondents were either Roman-Catholics or at least originated from Roman-Catholic families. The interviews concerned different aspects of plant use, but here we present data only on medicinal and herbal tea uses from respondents who possessed such knowledge. The informants were selected from people who were born on the islands and had their ancestry there. We decided to combine the answers about medicinal plants and recreational teas, as there is a large overlap between them – self-gathered local tea mixes are often drunk for digestion, and the border between tea plants and medicinal plants is difficult to draw (Sõukand and Kalle, 2013). We only included plants directly used by the informants or used by their ancestors in the past. The aim of study (documentation of traditional plant uses) was explained to the respondents. Prior informed oral consent was always sought.

Philips and Gentry’s (1993) use value index (UV) was applied to estimate the cultural importance of species:

where

In order to look for the sources of variability in the richness of the local pharmacopoeias we correlated the number of species used per single informant and the number of species in the island’s pharmacopoeia with geographical variables such as population size (from 2011), island area (km2), shortest distance to the mainland, geographical longitude and the number of species in the flora. The number of species in the flora was extracted from Nikolić et al. (2008) and supplemented by the works of Milović et al. (2016) for Olib and Pandža et al. (2011) for Vrgada.

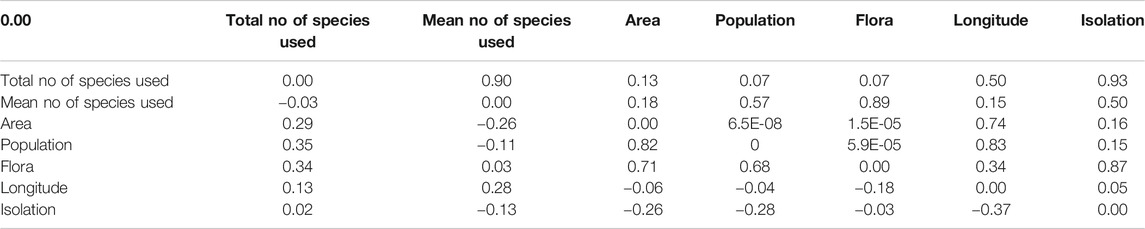

Statistical analysis was performed using open access PAST software (Hammer et al., 2001). The significance and strength of the relationships between variables was assessed using the Pearson correlation coefficient. Normality of the distribution of variables was tested with the Shapiro-Wilk test. All the variables had normal distribution.

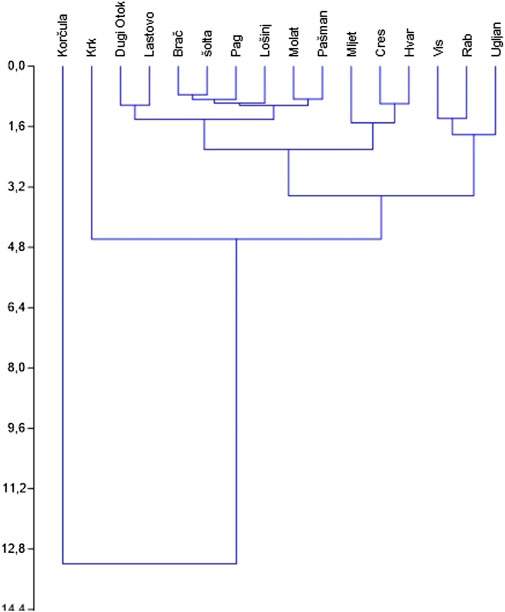

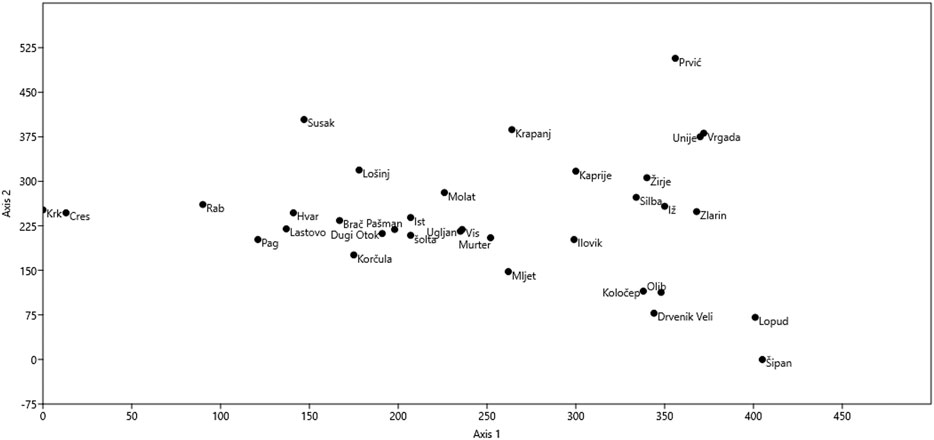

To visualize the similarity in medicinal species lists between the islands, we performed Detrended Component Analysis (DCA) on species level (Hill and Gauch, 1979). We plotted the results of DCA on the two main axes that caused the distribution of the data to visualize potential overlap and variation in the species composition used in different islands. Another way of visualizing the diversity of species composition on different islands was a numeral taxonomy dendrogram obtained by clustering. We used the most common method of clustering, i.e., Unweighted Pair Group Method with Arithmetic Mean (UPGMA), using Euclidean distance (Sokal and Michener, 1958; Bailey, 1994).

Plants were identified using standard floras available in this area of Europe, including guides for the identification of Croatian flora (Domac, 1994; Nikolić, 2019), Pignatti’s Flora of Italy (Pignatti, 1982) and the (Flora Croatica Database). Plant names were updated to be consistent with (The Plant List). Voucher specimens were collected on the islands where they were used, usually with the assistance of the respondents. They were deposited in the herbarium of Warsaw University (WA) with a small subset in the herbarium of the University of Zagreb, Faculty of Agriculture (ZAGR).

In our analyses, we divided islands into five groups (sub-archipelagos) corresponding to their administrative location in five regions (županija): 1) Kvarner islands, 2) Zadar islands (North Dalmatian Islands), 3) Šibenik islands, 4) Split islands (Central Dalmatian Islands), and 5) Dubrovnik islands (South Dalmatian Islands).

Results

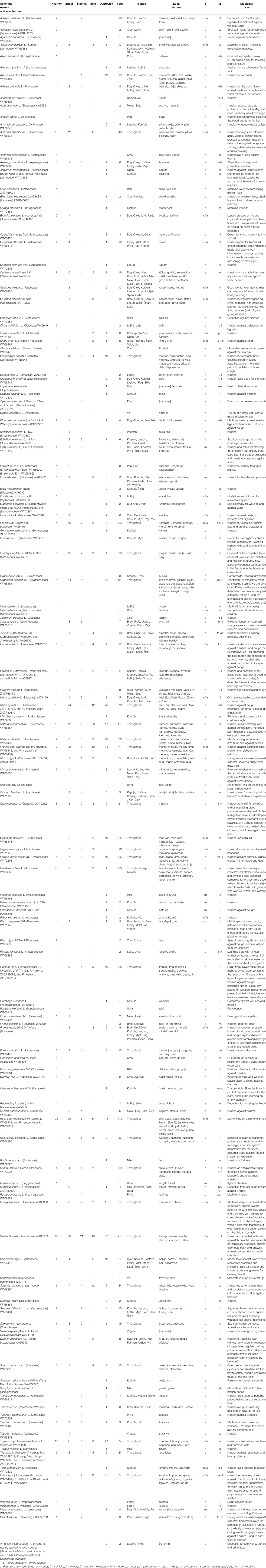

We recorded the use of 146 taxa from 59 families and identified the use of 131 of them for at least one medicinal purpose (Table 2). The remaining 15 species were used as a “healthy herbal tea”. The frequency curve is quite steep and 43 of them were recorded only in one interview, and 15 in two interviews, and only 88 were recorded in more than two interviews. Out of all the archipelagos within the Adriatic islands, the largest number of taxa both in terms of the total number of species (88) and the mean number of species listed per interview was recorded in the Dubrovnik archipelago (Table 1). The lowest number of species per interview was recorded in Kvarner. The shortest list of species (50) was recorded in the Šibenik archipelago (probably due to the smaller area and number of islands as well as the smallest number of interviews). When we look at single islands, the longest list of medicinal plants used was recorded on Korčula (66 species), Lošinj (45), Mljet (41), Šolta (37), Lastovo (35) and Molat (31). The highest mean number of species listed (Table 1) was recorded on Prvić (8.8), Korčula (8.4) and Šipan (8.2).

Most collected parts are aerial parts (flowering shoots with leaves or just leaves - 38% of use reports, flowers - 18%, fruits - 15%, underground organs - 0.8%).

A large majority of plants are collected from the wild (77%). As many as 66% are native to the flora and 13% are alien species. As many as 44% of the collected species are cultivated, so there is a large overlap between the two categories of wild and cultivated (e.g., Salvia offcinalis, Ruta graveolens, etc.).

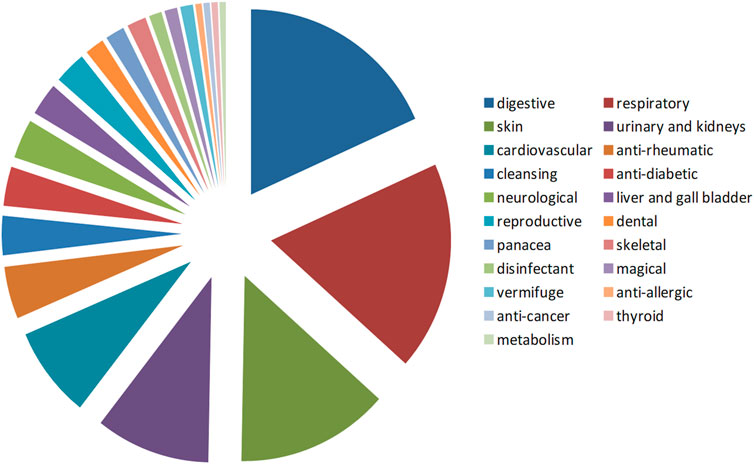

Infusion is the most common form of herb use. Decoction and steeping in rakija is rarely used. Rakija is the local term for spirits distilled from fruits (mainly grapes in this study area). The most commonly cured ailments are digestive (18.3%), respiratory (13.7%) and skin (11.7%) problems. These three types constituted half of all the use reports (Figure 2).

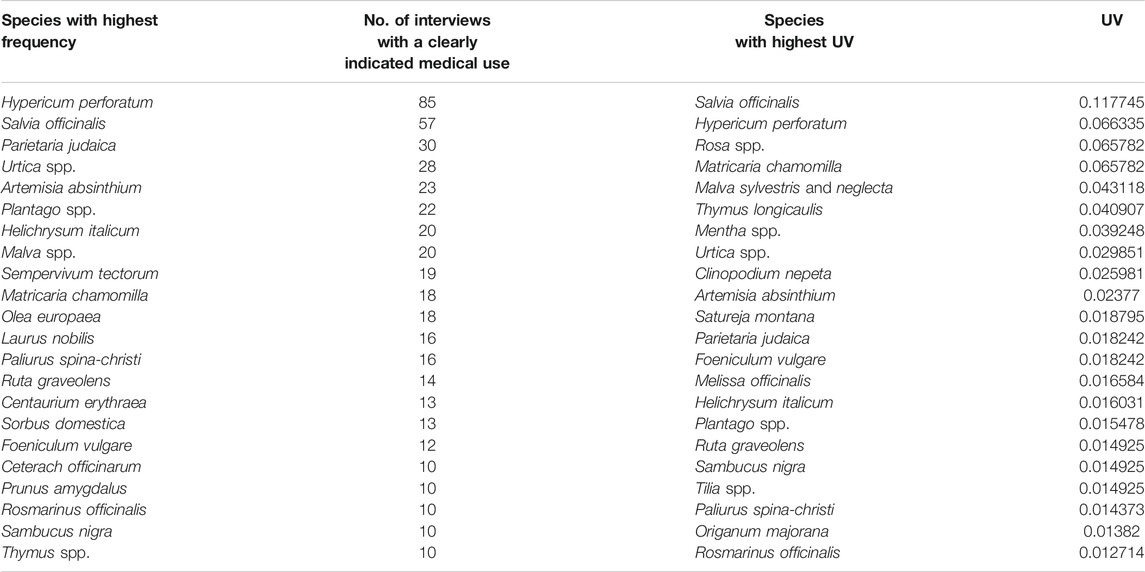

The most commonly used medicinal plants in the area are: Hypericum perforatum, Salvia officinalis, Parietaria judaica, Urtica spp., Artemisia absinthium, Plantago spp., Helichrysum italicum, Malva spp., Sempervivum tectorum and Matricaria chamomilla (Table 3). When cultural importance was expressed by the Use Value index, the species with highest score were: Salvia officinalis, Hypericum perforatum, Rosa spp., Matricaria chamomilla, Malva spp., Thymus spp., Mentha spp., Urtica spp., Clinopodium nepeta and Artemisia absinthium (also Table 3).

TABLE 3. The most frequently used medicinal plants in the study area and the plants with the highest use value.

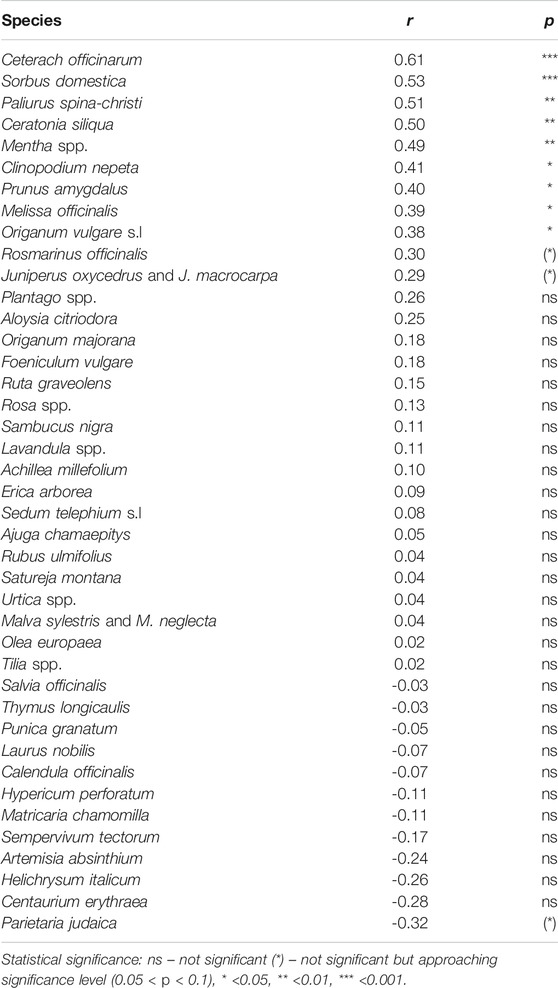

Most of the common species are used throughout the study area, from the Kvarner to the Dubrovnik Archipelago. If we look at correlations between island’s geographical longitude and proportion of interviews in which a given species is listed on the island, only a few species yield positive correlation indicating a tendency to be used more in the eastern part of the study area. The strongest such correlation was shown for Ceterach officinarum, Sorbus domestica and Paliurus spina-christi (Table 4). There were no significant negative correlations, which would indicate grouping uses in the western part of the study area.

TABLE 4. Correlation between the island’s geographical longitude and the species frequency (on a scale of 0–1) on particular islands.

Multivariate Analysis and Correlations

Korčula is singled out in cluster analysis as the most dissimilar to other islands (Figure 3). In DCA analysis islands from the same sub-archipelago tend to be grouped close to each other (Figure 4), especially in the case of Kvarner. We did not find any significant correlations (Table 5) between the number of medicinal plants listed per island or mean number of species listed in an interview per island with geographical variables (size of island, population, longitude, number of species in the flora). Thus all of the hypotheses presented in the introduction can be rejected. The largest correlation (but still not significant) was between the total number of species used on an island and its population (r = 0.35), number of species in the flora of the island (0.34) and the area (0.29). For mean number of species per interview the largest correlation was longitude (0.28).

FIGURE 3. Dendrogram showing UPGMA clustering (with Euclidean distance) of islands (those where over 10 interviews were carried out).

FIGURE 4. Detrended Correspondence Analysis biplot illustrating the two main axes of variability in the medicinal plant lists used in the studied islands.

TABLE 5. Correlation matrix of the variables studied (data for 29 islands, those for which the number of species in their flora is known). Left-bottom corner – correlation coefficient r, Right-top corner p values. Correlation matrix for the studied variables.

Discussion

Some More Interesting Plant Uses

Aloysia citriodora is commonly used on Korčula as a recreational herbal tea and as a stomachic; it is much less known outside this island. According to a local legend, it was brought by a sailor from South America a long time ago and people shared the plant with each other.

Artemisia caerulescens is a rare coastal absinth species which was highly prized on Cres for aromatic liqueur-making. The tradition has now nearly ceased due to the disappearance of the plant, whose habitats were destroyed by the tourism industry and which has been overharvested.

Bay (Laurus nobilis) is a spice and medicinal plant commonly used throughout the coast of Croatia. It is usually the leaves that are used; however, on Cres and Rab, there is a tradition of making a syrup from its fruits and using it to fight coughs as well as of using bay oil (“lumberovo ulje”) medicinally, especially as an externally applied vermifuge.

Two species of horsetail rarely used in Europe, Equisetum ramosissimum and E. telmateia, are used medicinally on Rab and Pag.

Satureja visianii is an endemic savory species restricted to Pelješac Peninsula and Korčula Island. It is included in herbal teas on par with Satureja montana.

Importance of a 40-day Period

An interesting phenomenon in the Adriatic folk pharmacopoeia is the importance of the period of 40 days for the maceration of plants in olive oil or keeping them in rakija. This is especially the case for “kantarion” Hypericum ointment for skin problems. The number of days was also mentioned e.g. on the occasion of making Plantago cough syrup or herbal liqueurs. The number 40 may have been chosen because of its importance in the Catholic liturgical year-Ascension Day comes forty days after Easter and Lent also lasts forty days; children are traditionally christened 40 days after birth (Đapo, 2015). Also quarantine, which was invented by the Republic of Ragusa (city Dubrovnik) for its visitors and lasted 30 days, and was later adopted by other circum-Mediterranean cities, especially by the Venetians, was extended to last 40 days until ship crew were allowed in a city (Anonymous, 2013).

Trava Iva

In Croatia “trava iva” is primarily the name of Teucrium montanum, a plant highly prized along most of the Croatian coast (Šugar, 2008). There are a number of sayings about this plant (e.g., “trava iva (od) mrtva čini/pravi živa”-it “brings the dead to life”) which illustrate its nature of panacea. On the islands Teucrium montanum is rare, and two other species are named trava iva and given the same powers. These are Ajuga chamepytis in the Zadar Archipelago and Teucrium polium (throughout). Iva is an ancient plant name in southeastern Europe. It was also used to name the closely related Ajuga iva (L.) Schreb. Iva/iwa describes various plants in different European languages, e.g. iwa for Salix caprea in Polish and continental Croatian, for Taxus baccata in German, and Latvian īwe also for T. baccata (Brückner, 1927), ivy for Hedera helix and ground ivy for Glechoma hederacea in English, and the Latin name Iva for a plant from the Ambrosiaceae family.

Fright

On the island of Korčula the local use of medicinal plants preserved some traditions of curing folk illnesses classified as “fright”- situations when a child would get frightened, cry a lot and become restless-using Marrubium peregrinum, Ruta graveolens, Vitex agnus-castus or charcoal oak. The illness is known in folk pharmacopoeias throughout Europe (e.g., see Kujawska et al., 2017). This type of folk illness was however forgotten on other islands.

Changes

The use of medicinal plants in the Adriatic islands has undergone dramatic changes due to shifts in lifestyle. Previous economic activities oriented toward fishery and agriculture (mainly viticulture, olive growing and sheep husbandry) has given way to a lifestyle dominated by dependence on tourism. The population is aging and composed mainly of retired people; many return to the islands from a life-long stay in Zagreb, Split, Rijeka, Zadar, the United States or Australia. Many of them are sailors-skippers of private yachts in France or Monaco. An important factor in changes in the local plant use, apart from the smaller connection to nature, is the disappearance of habitats suitable for collecting herbs. Most medicinal herbs in the islands, such as Salvia officinalis, Hypericum perforatum, Ruta graveolens, Satureja montana etc. have been associated with open rocky habitats grazed by sheep. Nowadays, maquis and Pinus halepensis encroach on the former pastures and even the most common aromatic herbs become rare. Ruderal weed habitats are also becoming species-poor due to the use of herbicides in orchards and the cessation of cultivation of wheat. Matricaria chamomilla, which was once collected from semi-spontaneous localities in gardens, now has to be sown every year. The lack of wild herbs has shifted the use of medicinal plants to those that come from the garden, where Lamiaceae plants dominate. Some new uses reflect general fashions in the whole area of south-eastern Europe, e.g., the popularity of Helichrysum italicum oil makes the species more popular as a part of herbal and liqueur mixes. The same goes for olive leaf herbal tea.

The most commonly used medicinal plants are used throughout the area. However, some regionalisms can be observed. For example Parietaria judaica, Elymus repens, Plantago spp. and Ruta graveolens are used mainly in the northern part of the study area. It must be stressed that the large majority of plants used in the islands, apart from some alien species, have been present in the European medical tradition since the times of Dioscorides (see e.g., Dioscorides et al., 2000; Leonti and Verpoorte, 2017; Krnjak, 2019).

Comparison With Other Areas

The list of medicinal taxa used – 131 species - is not very long, taking into consideration the fact that it is spread over a few hundred kilometers and divided into islands with different histories. For comparison, Papageorgiou et al. (2020) recorded the harvesting of 144 species of medicinal plants just on one island (Lemnos) in Greece, and Axiotis et al. (2018) found 109 species of medicinal importance on only nine east Egean islands. Vitasović-Kosić et al. (2017) found 90 species used in Ćićarija, a small part of Istria in mainland Croatia, and Varga et al. (2019) found 83 species of medicinal plants used in a small region of inland Dalmatia. The unifying factor for the pharmacopoeias must be the fact that the islands have a very similar climate and vegetation, most of them composed of typical Mediterranean maquis, agricultural land and remnants of Quercus ilex forests. Only the westernmost Kvarner island has a slightly cooler climate with submediterranean influences.

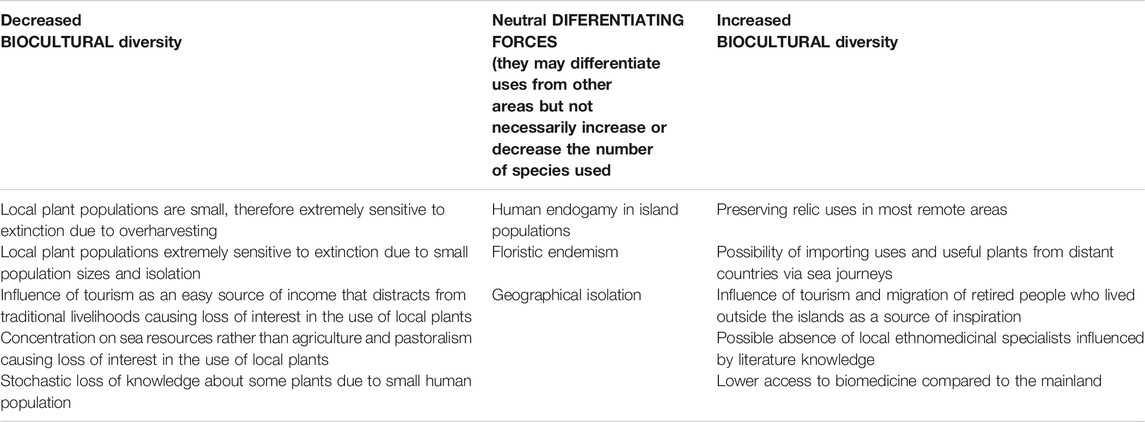

Insularity

In order to establish the extent to which local pharmacopoeias are impoverished by the insular character of the region, we tried to create a model for island pharmacopoeia that would take into account all the phenomena associated with being on an island that we observed or heard about from our informants (Table 6). We divided these forces into three domains. The first one is all the phenomena that might increase the richness of uses of plants due to their island location. Here we can mention limited access to biomedical services, which can help to maintain the tradition of local herbal medicine. Another is the possibility of long distance influence from sailors who bring new plants and uses from far-away countries. For example, the use of Aloysia citriodora is very widespread in Korčula. The plant is little known in the other islands. Specialized use can also stem from the existence of endemic plants (Redžić, 2009). The only endemic plant we found in use is Satureja visianii (Nikolić et al., 2020). The use of endemic plants is definitely more possible in archipelagos which were isolated from the mainland longer than the Croatian islands, e.g., in the islands of Greece (e.g., Axiotis et al., 2018). The majority of plants used in our study are common wild and cultivated pan-Mediterranean taxa. Isolation from the mainland also helps to give a local character to plant uses, especially given that endogamy in human populations is very strong on the islands. This is in contrast to the mainland of southern Croatia, where exogamy is very common – men have found wives from different villages – but as we found in our previous studies (Dolina et al., 2016), it is always the woman who moves to the man’s village (virilocality). This helps to exchange information on plants between villages – it is transferred between daughters-in-law and mothers-in-law from different villages. On the other hand endogamy, prevalent on the islands, can also conserve unique plant uses without bringing any new influence.

The different driving forces of diversity presented, some more advantageous for larger islands, some for the small, are probably responsible for the fact that overall correlations between the studied variables were not significant (Table 5). It was rather the historical and social trajectories of each island that are more important. The similarity of neighboring islands with each other (seeFigure 4) suggests that there has been an exchange of medicinal knowledge between them. This comes as no surprise, as very often two fishing villages from two islands facing each other were often involved in common fishing enterprises, which resulted in an exchange of marriage partners. We recorded such stories for Hvar and Vis, Pag and Rab etc.

One of the most important forces influencing local pharmacopoeas on some islands is the presence of local herbal specialists. The presence of such individuals may help maintain the general knowledge of medicinal herbs, but may also have a homogenizing effect if their knowledge is influenced by popular literature. On a few middle-sized islands, we have found influential local amateur herbalists who serve as the main hub of knowledge circulation on a given island. It is them who experiment with new species (often based on data from literature) or teach people how to name plants. For example, Mr Ivan Bamba Čumbelić on Mljet is active not only in this domain but is generally a social institution for this island. On Lastovo, Mr Giovanni Santi, who originates from the island, returned there after living abroad, retired and started an essential oil distillery as well as building a healing pyramid. On Šolta, Mr Dinko Sule publishes a local periodical devoted to the island’s history, culture and biology (Bašćina). He is also both a reservoir of past uses and an influential person on the island. Practically every conversation on plants with the locals started with them directing us to their local herb specialist. However, a large proportion of the islands, particularly the small ones, are devoid of individuals who are particularly interested in medical herbs, and people now only use or know a few basic plants. Similarly to the domain of wild vegetables (Łuczaj et al., 2019a), Korčula stands out in the medicinal plant domain as an island with a very vivid local community interested in preserving their tradition and using local resources. This island not only has the most widespread use of wild vegetables and the longest list of wild vegetables used but also the longest list of medicinal herbs in active use. Interestingly, also a small island of Šipan in the same sub-archipelago showed a very high level of knowledge of its inhabitants expressed by a large mean number of species listed.

Limitations

The limitation of our study was an unequal number of interviews made in the islands. Nowadays, only a portion of the population claim to use medicinal plants, hence the difficulties in providing a larger number of interviews. We did not want to artificially set the number of interviews the same and rather chose to go for a saturation point when finding a new knowledgeable informant proved difficult. We believe that in many smaller islands we interviewed all such individuals.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The name of the repository can be found below: http://repozytorium.ur.edu.pl/handle/item/5756. Voucher specimen numbers are in Table 2.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the host Institution: Institute of Biology and Biotechnology of Rzeszow University. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements. Written informed consent was not obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author Contributions

Concept of the study and first draft of the paper–ŁŁ. All the authors read and approved the final version of the paper and took part in the field study including interviewing and voucher specimen collection: ŁŁ (30 islands), IV-K (22 islands), MJ-D (6 islands), KD (5 islands) and MJ (1 island).

Funding

The research was financed by funds from the Ministry of Science and Higher Education, the National Science Center in Poland (NCN) (2015/19/B/HS3/00471).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to the inhabitants of the islands for their amazing cooperation in the research.

References

Anonymous, (2013). Etymologia: Quarantine. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 19 (2), 263. doi:10.3201/eid1902.et1902

Axiotis, E., Halabalaki, M., and Skaltsounis, L. A. (2018). An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in the Greek islands of North Aegean region. Front. Pharmacol. 9, 409. doi:10.3389/fphar.2018.00409

Bailey, K. (1994). Typologies and taxonomies: an intriduction to classification techniques. London-New Delhi: Sage Publications.

Barata, A. M., Rocha, F., Lopes, V., and Carvalho, A. M. (2016). Conservation and sustainable uses of medicinal and aromatic plants genetic resources on the worldwide for human welfare. Ind. Crops Prod. 88, 8–11. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2016.02.035

Bulut, G. (2016). Medicinal and wild food plants of Marmara island (balikesir-Turkey). Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 85(2). doi:10.5586/asbp.3501

Dioscórides , , Osbaldeston, T. A., and Wood, R. P. (2000). De materia medica: being an herbal with many other medicinal materials: written in Greek in the first century of the common era: a new indexed version in modern English.

Dolina, K., Jug-Dujaković, M., Luczaj, L., and Vitasović-Kosić, I. (2016). A century of changes in wild food plant use in coastal Croatia: the example of Krk and Poljica. Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 85 (3). doi:10.5586/asbp.3508

Etkin, N. L. (2008). Edible medicines: an ethnopharmacology of food. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

Ferrier, J., Šaćiragić, L., Trakić, S., Chen, E. C., Gendron, R. L., Cuerrier, A., et al. (2015). An ethnobotany of the lukomir highlanders of Bosnia & herzegovina. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 11 (1), 81. doi:10.1186/s13002-015-0068-5

Flora Croatica Database. Available at: https://hirc.botanic.hr/fcd/. (Accessed Sep 15, 2020).

Glück, L. (1892). Narodni lijekovi iż bilinstva u Bosni. Glasnik Zemaljskog Muzeja u Bosni i Heregovini 4 (2), 134–167.

Grasser, S., Schunko, C., and Vogl, C. R. (2012). Gathering "tea" - from necessity to connectedness with nature. Local knowledge about wild plant gathering in the Biosphere Reserve Grosses Walsertal (Austria). J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomedicine 8(1), 31. doi:10.1186/1746-4269-8-31

Grigoriadou, K., Krigas, N., Lazari, D., and Maloupa, E. (2020). Sustainable use of mediterranean medicinal-aromatic plants. Feed additives. Academic Press, 57–74.

Hammer, Ø., Harper, D. A. T., and Ryan, P. D. (2001). PAST: paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis. Palaeontol. Electronica 4, 9.

Heinrich, M. (2000). Ethnobotany and its role in drug development. Phytother. Res. 14, 479–488. doi:10.1002/1099-1573(200011)14:7<479::AID-PTR958>3.0.CO;2-2

Heinrich, M., Lardos, A., Leonti, M., Weckerle, C., Willcox, M., Applequist, W., et al. (2018). Best practice in research: consensus statement on ethnopharmacological field studies - ConSEFS. J. Ethnopharmacology 211, 329–339. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2017.08.015

Hill, M. O., and Gauch, H. G. (1980). Detrended correspondence analysis: an improved ordination technique. In: van der Maarel, editor. Classification and ordination - symposium on advances in vegetation science, nijmegen, The Netherlands, 1979.Dordrecht: Springer p. 47–58.

Ivancheva, S., and Stantcheva, B. (2000). Ethnobotanical inventory of medicinal plants in Bulgaria. J. Ethnopharmacology 69 (2), 165–172. doi:10.1016/s0378-8741(99)00129-4

Jarić, S., Mačukanović-Jocić, M., Djurdjević, L., Mitrović, M., Kostić, O., Karadžić, B., et al. (2015). An ethnobotanical survey of traditionally used plants on Suva planina mountain (south-eastern Serbia). J. Ethnopharmacol. 175, 93–108. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2015.09.002

Köhler, P. (2015). The romantic myth about the antiquity of folk botanical knowledge and its fall - Józef rostafiński's case. Abhps 3 (1), 99–108. doi:10.11590/abhps.2015.1.06

Krnjak, I. (2019). Hrvatske ljekaruše u svjetlu antičke medicine i suvremene fitoterapije. (Zagreb: Doctoral dissertation, University of Zagreb Faculty of Pharmacy and Biochemistry)Available at: https://zir.nsk.hr/islandora/object/pharma:1167/datastream/PDF/download.

Kujawska, M., Klepacki, P., and Łuczaj, Ł. (2017). Fischer’s plants in folk beliefs and customs: a previously unknown contribution to the ethnobotany of the Polish-Lithuanian-Belarusian borderland. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 13 (1), 20. doi:10.1186/s13002-017-0149-8

Kujundžić, N. (2020). Great folk medicine book from poljica (Bratulic's Folk Medicine Book). Acta Med. Hist. Adriat. 18 (1), 89–104. doi:10.31952/amha.18.1.5

Leonti, M. (2011). The future is written: impact of scripts on the cognition, selection, knowledge and transmission of medicinal plant use and its implications for ethnobotany and ethnopharmacology. J. Ethnopharmacology 134 (3), 542–555. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2011.01.017

Leonti, M., and Verpoorte, R. (2017). Traditional Mediterranean and European herbal medicines. J. Ethnopharmacology 199, 161–167. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2017.01.052

Lumpert, M., and Kreft, S. (2017). Folk use of medicinal plants in Karst and Gorjanci, Slovenia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 13 (1), 16. doi:10.1186/s13002-017-0144-0

Łuczaj, Ł. (2012). A relic of medieval folklore: Corpus Christi Octave herbal wreaths in Poland and their relationship with the local pharmacopoeia. J. Ethnopharmacol. 142 (1), 228–240. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2012.04.049

Łuczaj, Ł., Jug-Dujaković, M., Dolina, K., Jeričević, M., and Vitasović-Kosić, I. (2019a). The ethnobotany and biogeography of wild vegetables in the Adriatic islands. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 15 (1), 18. doi:10.1186/s13002-019-0297-0

Łuczaj, Ł., Jug-Dujaković, M., Dolina, K., and Vitasović-Kosić, I. (2019b). Plants in alcoholic beverages on the Croatian islands, with special reference to rakija travarica. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 15 (1), 51. doi:10.1186/s13002-019-0332-1

MacArthur, R. H., and Wilson, E. O. (1967). The theory of island biogeography. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Mattalia, G., Sõukand, R., Corvo, P., and Pieroni, A. (2020). Dissymmetry at the Border: Wild Food and Medicinal Ethnobotany of Slovenes and Friulians in NE Italy. Econ. Bot. 74, 1–14. doi:10.1007/s12231-020-09488-y

Menković, N., Šavikin, K., Zdunić, G., Milosavljević, S., and Živković, J. (2014). Medicinal plants in northern Montenegro: traditional knowledge, quality, and resources Ethnobotany and biocultural diversities in the Balkans. New York, NY: Springer, 197–228.

Milović, M., Kovačić, S., Jasprica, N., and Stamenković, V. (2016). Contribution to the study of Adriatic island flora: Vascular plant species diversity in the Croatian Island of Olib. Nat. Croat. 25(1), 25–54. doi:10.20302/NC.2016.25.2

Moerman, D. E. (1979). Symbols and selectivity: a statistical analysis of native American medical ethnobotany. J. Ethnopharmacology 1 (2), 111–119. doi:10.1016/0378-8741(79)90002-3

Mustafa, B., Hajdari, A., Krasniqi, F., Hoxha, E., Ademi, H., Quave, C. L., et al. (2012). Medical ethnobotany of the Albanian Alps in Kosovo. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomedicine 8 (1), 6. doi:10.1186/1746-4269-8-6

Mustafa, B., Hajdari, A., Pulaj, B., Quave, C. L., and Pieroni, A. (2020). Medical and food ethnobotany among Albanians and Serbs living in the Shtërpcë/Štrpce area, South Kosovo. J. Herbal Med. 22, 100344. doi:10.1016/j.hermed.2020.100344

Nedelcheva, A., and Dogan, Y. (2015). An ethnobotanical study on wild medicinal plants sold in the local markets at both sides of the Bulgarian - Turkish border. Planta Med. 81 (16), PW_13. doi:10.1055/s-0035-1565637

Nikolić, T. Editor (2019). Flora Croatica 4 ‐ Vaskularna flora Republike Hrvatske. Zagreb: Alfa d.d.

Nikolić, T., Antonić, O., Alegro, A. L., Dobrović, I., Bogdanović, S., and Liber, Z. (2008). Plant species diversity of Adriatic islands: An introductory survey. Plant Biosyst. 142, 435–445. doi:10.1080/11263500802410769

Nikolić, T., Fois, M., and Milašinović, B. (2020). The endemic and range restricted vascular plants of Croatia: diversity, distribution patterns and their conservation status. Phytotaxa. 436(2), 125–140. doi:10.11646/phytotaxa.436.2.3

Pandža, M., Milović, M., Krpina, V., and Tafra, D. (2011). Vascular flora of the Vrgada islets (Zadar archipelago, eastern Adriatic). Nat. Croat. 20 (1), 97–116.

Papageorgiou, D., Bebeli, P. J., Panitsa, M., and Schunko, C. (2020). Local knowledge about sustainable harvesting and availability of wild medicinal plant species in Lemnos island, Greece. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 16 (1), 1–23. doi:10.1186/s13002-020-00390-4

Philips, O., and Gentry, A. H. (1993). The Useful Plants of Tambopata, Peru: I. Statistical Hypotheses Tests with A New Quantitative Technique. Econ. Bot. 47(1), 15–32. doi:10.1007/BF02862203

Pieroni, A., and Giusti, M. E. (2008). The remedies of the folk medicine of the Croatians living in Cićarija, northern Istria. Coll. Antropol. 32 (2), 623–627.

Pieroni, A., Giusti, M. E., Münz, H., Lenzarini, C., Turković, G., and Turković, A. (2003). Ethnobotanical knowledge of the Istro-Romanians of Žejane in Croatia. Fitoterapia 74 (7-8), 710–719. doi:10.1016/j.fitote.2003.06.002

Pieroni, A., Giusti, M. E., and Quave, C. L. (2011). Cross-Cultural Ethnobiology in the Western Balkans: Medical Ethnobotany and Ethnozoology Among Albanians and Serbs in the Pešter Plateau, Sandžak, South-Western Serbia. Hum. Ecol. 39 (3), 333. doi:10.1007/s10745-011-9401-3

Pieroni, A., Ibraliu, A., Abbasi, A. M., and Papajani-Toska, V. (2015). An ethnobotanical study among Albanians and Aromanians living in the Rraicë and Mokra areas of Eastern Albania. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 62 (4), 477–500. doi:10.1007/s10722-014-0174-6

Pieroni, A. (2008). Local plant resources in the ethnobotany of Theth, a village in the Northern Albanian Alps. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 55 (8), 1197–1214. doi:10.1007/s10722-008-9320-3

Pieroni, A., and Price, L. (2006). Eating and healing: traditional food as medicine. New York: CRC Press.

Pieroni, A., and Quave, C. L. (2014). Ethnobotany in the Balkans: Quo Vadis? Ethnobotany and biocultural diversities in the Balkans. New York, NY: Springer, 1–9.

Pieroni, A., Rexhepi, B., Nedelcheva, A., Hajdari, A., Mustafa, B., Kolosova, V., et al. (2013). One century later: the folk botanical knowledge of the last remaining Albanians of the upper Reka Valley, Mount Korab, Western Macedonia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomedicine 9 (1), 22. doi:10.1186/1746-4269-9-22

Povšnar, M., Koželj, G., Kreft, S., and Lumpert, M. (2017). Rare tradition of the folk medicinal use of Aconitum spp. is kept alive in Solčavsko, Slovenia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 13 (1), 45. doi:10.1186/s13002-017-0171-x

Quave, C. L., Pardo-de-Santayana, M., and Pieroni, A. (2012). Medical ethnobotany in Europe: from field ethnography to a more culturally sensitive evidence-based cam? Evidence-based complementary and alternative medicine, 2012, 156846. doi:10.1155/2012/156846Evid. Based Complement. Alternat Med.

Redžić, S. (2009). Potential use of vascular endemic plants as a source of new medicines. Afr. J. Tradit. Complement. Altern. Med. 46, 465–466.

Rexhepi, B., Mustafa, B., Hajdari, A., Rushidi-Rexhepi, J., Quave, C. L., and Pieroni, A. (2013). Traditional medicinal plant knowledge among Albanians, Macedonians and Gorani in the Sharr Mountains (Republic of Macedonia). Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 60 (7), 2055–2080. doi:10.1007/s10722-013-9974-3

Sõukand, R., and Kalle, R. (2013). Where does the border lie: Locally grown plants used for making tea for recreation and/or healing, 1970s-1990s Estonia. J. Ethnopharmacology 150(1), 162–174. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2013.08.031

Šarić-Kundalić, B., Dobeš, C., Klatte-Asselmeyer, V., and Saukel, J. (2010). Ethnobotanical study on medicinal use of wild and cultivated plants in middle, south and west Bosnia and Herzegovina. J. Ethnopharmacol. 131 (1), 33–55. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2010.05.061

Šarić-Kundalić, B., Dobeš, C., Klatte-Asselmeyer, V., and Saukel, J. (2011). Ethnobotanical survey of traditionally used plants in human therapy of east, north and north-east Bosnia and Herzegovina. J. Ethnopharmacol. 133 (3), 1051–1076. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2010.11.033

Šarić-Kundalić, B., Klatte-Asselmeyer, V., Dobeš, C., and Saukel, J. (2009). Ethnobotanical use of wild and cultivated plants in traditional medicine of Middle Bosnia and Herzegovina. Planta Med. 75 (09), PB23. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1234435

Šavikin, K., Zdunić, G., Menković, N., Živković, J., Ćujić, N., Tereščenko, M., et al. (2013). Ethnobotanical study on traditional use of medicinal plants in South-Western Serbia, Zlatibor district. J. Ethnopharmacol. 146 (3), 803–810. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2013.02.006

Sokal, R., and Michener, C. (1958). A statistical method for evaluating systematic relationships. University of Kansas Science Bulletin, 38, 1409–1438.

Sule, D. (2010). Zanimljivosti iz biljnog i životnjskog svijeta otoka Šolte. Bašćina. 19, 32–60. doi:10.4314/njm.v19i3.60237

The Plant List. Available at:http://theplantlist.org/. (Accessed Jan 15, 2019).

Tsioutsiou, E. E., Giordani, P., Hanlidou, E., Biagi, M., De Feo, V., and Cornara, L. (2019). Ethnobotanical Study of Medicinal Plants Used in Central Macedonia, Greece. Evidence-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2019, 1. doi:10.1155/2019/4513792

Uibu, M. (2020). The emergence of new medical pluralism: the case study of Estonian medical doctor and spiritual teacher Luule Viilma. Anthropol. Med. 1–16. doi:10.1080/13648470.2020.1785843

Varga, F., Šolić, I., Dujaković, M. J., Łuczaj, Ł., and Grdiša, M. (2019). The first contribution to the ethnobotany of inland Dalmatia: medicinal and wild food plants of the Knin area, Croatia. Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 88 (2), 1. doi:10.5586/asbp.3622

Vitasović-Kosić, I., Juračak, J., and Łuczaj, Ł. (2017). Using Ellenberg-Pignatti values to estimate habitat preferences of wild food and medicinal plants: an example from northeastern Istria (Croatia). J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 13 (1), 31. doi:10.1186/s13002-017-0159-6

Zlatković, B. K., Bogosavljević, S. S., Radivojević, A. R., and Pavlović, M. A. (2014). Traditional use of the native medicinal plant resource of Mt. Rtanj (Eastern Serbia): Ethnobotanical evaluation and comparison. J. Ethnopharmacol. 151 (1), 704–713. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2013.11.037

Žuna Pfeiffer, T., Krstin, L., Špoljarić Maronić, D., Hmura, M., Eržić, I., and Bek, N. (2020). An ethnobotanical survey of useful wild plants in the north-eastern part of Croatia (Pannonian region). Plant Biosyst. 154(4), 463–473. doi:10.1080/11263504.2019.1635222

Žic, I. (1900). Vrbnik na otoku Krku. Narodni život i običaji. Zbornik za narodni život i običaje južnih Slavena 5, 51–83.

Keywords: ethnobotany, traditional medicine, herbal medicine, island biogeography, ethnomedicine, herbal teas, Croatia

Citation: Łuczaj Ł, Jug-Dujaković M, Dolina K, Jeričević M and Vitasović-Kosić I (2021) Insular Pharmacopoeias: Ethnobotanical Characteristics of Medicinal Plants Used on the Adriatic Islands. Front. Pharmacol. 12:623070. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.623070

Received: 29 October 2020; Accepted: 04 March 2021;

Published: 07 May 2021.

Edited by:

Zora Dajic Stevanovic, University of Belgrade, SerbiaReviewed by:

Anely Nedelcheva, Sofia University, BulgariaSol Cristians, National Autonomous University of Mexico, Mexico

Copyright © 2021 Łuczaj, Jug-Dujaković, Dolina, Jeričević and Vitasović-Kosić. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Łukasz Łuczaj, bHVrYXN6Lmx1Y3phakBpbnRlcmlhLnBs

Łukasz Łuczaj

Łukasz Łuczaj Marija Jug-Dujaković2

Marija Jug-Dujaković2 Katija Dolina

Katija Dolina Mirjana Jeričević

Mirjana Jeričević Ivana Vitasović-Kosić

Ivana Vitasović-Kosić