- 1Department of Immunology and Pathogenic Biology, Yanbian University Medical College, Yanji, China

- 2Department of Pathology and Physiology, Yanbian University Medical College, Yanji, China

Melanoma is aggressive and can metastasize in the early stage of tumor. It has been proved that dihydroartemisinin (DHA) positively affects the treatment of tumors and has no apparent toxic and side effects. Our previous research has shown that DHA can suppress the formation of melanoma. However, it remains poorly established how DHA impacts the invasion and metastasis of melanoma. In this study, B16F10 and A375 cell lines and metastatic tumor models will be used to investigate the effects of DHA. The present results demonstrated that DHA inhibited the proliferative capacity in A375 and B16F10 cells. As expected, the migration capacity of A375 and B16F10 cells was also reduced after DHA administration. DHA alleviated the severity and histopathological changes of melanoma in mice. DHA induced expansion of CD8+CTL in the tumor microenvironment. By contrast, DHA inhibited Treg cells infiltration into the tumor microenvironment. DHA enhanced apoptosis of melanoma by regulating FasL expression and Granzyme B secretion in CD8+CTLs. Moreover, DHA impacts STAT3-induced EMT and MMPS in tumor tissue. Furthermore, Metabolomics analysis indicated that PGD2 and EPA significantly increased after DHA administration. In conclusion, DHA inhibited the proliferation, migration and metastasis of melanoma in vitro and in vivo. These results have important implications for the potential use of DHA in the treatment of melanoma in humans.

Introduction

Melanoma is a malignant tumor with a progressively higher prevalence and worse prognosis worldwide. Melanoma is an aggressive form of skin cancer that often results in early metastasis due to the loss of cell adhesion of the primary tumor, leading to high mortality rates (Ferlay et al., 2015). Furthermore, melanoma is more prone to spread than any other form of skin carcinomas, with the lungs being the most common site of distant metastasis, few satisfactory treatments are available, except for surgery. The FDA presently approved immune checkpoint inhibitors for use in patients with advanced melanoma, such as Nivolumab and Pembrolizumab (Topalian et al., 2019), and immune checkpoint therapy markedly reduced cancer burden and improved both progression-free survival and response rates in patients with advanced melanoma. Nevertheless, patients who ceased CTLA-4/PD-1 blockade therapy due to severe irAEs experienced a higher relapse rate or significant toxicity after resuming anti-PD1 treatment at a relatively high speed (Pollack et al., 2018). Furthermore, the benefits of Anti-PD1 therapy are only temporary, most patients who undergo monotherapy develop drug resistance. While the FDA has also approved several immunotherapies for patients with advanced melanoma, the response rates are generally low, and the severe side effects of immunotherapy can be fatal for patients. Therefore, it is urgent to develop a safer, more effective drug with fewer side effects to gradually inhibit the distant metastatic ability of melanoma and reduce the mortality rate of patients.

Dihydroartemisinin (DHA), the principal artemisinin extracted from the traditional Chinese medicine Artemisia annua, has better water solubility and antimalarial activity compared to other artemisinin derivatives (Lin et al., 1989). In addition, several researchers have demonstrated that DHA is minimally toxic to normal cells (Efferth and Kaina, 2010). It has not only been applied as an antimalarial drug. Still, it has also proven anti-tumor properties, such as lung cancer (Yan et al., 2018), breast cancer (Yao et al., 2018), prostate cancer (Paccez et al., 2019), ovarian cancer (Li et al., 2017). DHA has previously been shown to exhibit toxic effects on various cancer cells by facilitating cell cycle arrest (Lin et al., 1989), promoting apoptosis (Thongchot et al., 2018), preventing angiogenesis (Ho et al., 2014), and abrogating cancer invasion and metastasis (Cheong et al., 2020). Our previous studies demonstrated that DHA inhibits melanoma in situ and promotes autophagy (Yu et al., 2020). However, how DHA affects the development of metastatic melanoma is still being explored.

It is widely known that metastasis is a significant factor in tumor mortality, accounting for 90% deaths. Alarmingly, recent studies have indicated that metastases may occur early in melanoma development or before the primary tumor has formed. Currently, only the treatment methods used to inhibit melanoma migration and metastasis are not perfect. Therefore, inhibition of metastasis is considered to be the primary treatment for melanoma.

In the current research, we have closely examined the immunomodulatory activity and anti-tumor capacity of DHA on melanoma using in vitro and in vivo assays. In addition to demonstrating growth-inhibitory and pro-apoptotic properties of DHA in melanoma cells, our studies show that DHA can stimulate the immune response to melanoma in vivo. The activity of DHA on the lymphocyte component of the tumor microenvironment may be a key finding in the tumor immune escape response (Simiczyjew et al., 2020). Therefore, our conclusions disclosed another facet of the inhibitory effects of DHA on melanoma, which might have potential clinical implications.

Materials and Methods

The Cell Lines and Cell Culture

The B16F10 cells were purchased from the Fudan IBS Cell Center (China). The A375 cells were a gift from Associate professor Yingshi Piao from the Department of pathology and physiology, Yanbian University, China. All cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM, Gibco, Gaithersburg, MD), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco, Gaithersburg, MD) 1% penicillin/streptomycin mixture in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37°C.

Construction of the Mouse Melanoma Model

8-to-10-week-old female C57BL/6 mice were obtained from the Experimental Animal Centre of Yanbian University. Mice were housed in Specific pathogen Free conditions. The Experimental Animal Ethical Committee approved all studies and procedures of Yanbian University before the initiation of the experiment (SYXK (ji) 2020-0009). The mice were injected via the tail vein with 2 × 106 B16F10 cells in 400 ml of phosphate-buffered saline to build the experimental melanoma lung metastasis model. Dihydroartemisinin was administered to mice by gavage at both high and low doses (25/50 mg/kg/d) every day, and the mice were sacrificed after 28 days of continuous gavage treatment.

Cell Proliferation Assay

The influence of DHA on the proliferation of B16F10 cells was measured by Cell Counting Kit-8 assay (Dijindo, Japan). B16F10 cells in the mid-log phase were plated at a density of 5 × 103 cells per well for 24 h in a 200 μL medium. The medium was then substituted with DMEM containing different concentrations of DHA (total volume of 200 µL per well). A375 cells were plated in 96-well plates at a density of 1 × 105 cells per well and treated with different concentrations of DHA for 48 h. MTT (5 mg/ml) was added and then incubated at 37°C in the dark for 4 h. The addition of DMSO stopped the reaction. After a further 48 h of incubation, the proliferation rate of the cells was calculated by measuring the absorbance (OD = 450 nm).

Wound Healing Assay

Cells were seeded on 6 well plates. After the cells have reached 100% confluence, a wound is scraped out on the monolayer using a conventional pipette tip, and the dislodged cells or any loose cell debris is removed by washing with PBS. Different concentration gradients of DHA were added for culture and photographed at 0, 12, 24, and 48 h, respectively.

Cell Migration Assays

Cell migration assays were performed with transwell inserts (Corning, NY, United States). A375 or B16F10 cells were placed into the upper chamber, and serum below DMEM-1% FBS medium was added as a chemoattractant in the lower chamber. 4–6 h later, different concentrations of DHA were inserted. The cells were incubated for 24 h and then fixated with methanol and stained with saponin solution for 8 min. The migratory situation was known by observing the cells that migrate to the lower side of the filter in a microscope. The experiment was repeated in triplicate.

H&E Staining and Immunohistochemistry

After 4 weeks, the mice were euthanized, and lung samples were removed for paraffin-embedded cross-sections. These sections were carefully placed in 50°C incubators overnight, and the sections were first stained with hematoxylin and then with eosin. These slides were washed in distilled water and then dehydrated through graded alcohol, dried at room temperature, and observed histopathological changes under the microscope. After dissolving off the wax from the sections with xylene, they were hydrated with graded alcohol. The sections were first rinsed with PBS and exposed to citric acid buffer for 20 min for antigen retrieval. The Ki-67 (1:400), Foxp3 (1:100), CD4 (1:100), and CD8 (1:400) mAb were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology and incubated on sections overnight according to those antibody instructions. The sections were exposed to the appropriate horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody and developed in a dark room at the ambient temperature of 10 min. The sections were rinsed with tap water, and the substrate reaction was terminated. The cells were counted from the infection site in five serials sections, the numbers of infiltration cells were averaged in more than five power microscopic fields (HPFs, 0.07 mm2).

Western Blotting Assay

RIPA containing PMSF, protease inhibitor, and phosphotransferase inhibitors were used for protein extraction. Measurement of protein concentrations in lung tissue and cells using a bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit (Solarbio, Beijing, China). Equal amounts of protein were then loaded onto SDS-PAGE mini-gels, run, and transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Roche, Switzerland). These were then blocked with 5% skimmed milk and incubated overnight with the relevant primary antibody. N-cadherin (1:1,000), ZEB1 (1:1,000), Snail (1:1,000), and Twist (1:1,000) mAb were obtained from Proteintech (Rosemont, IL, United States); caspase-3 (1:500), Cleaved-caspase-3 (1:500), caspase-8 (1:1,000), Cleaved-caspase-8 (1:500), p-Ezrin (1:1,000), Ezrin (1:1,000), p-STAT3 (1:500), STAT3 (1:500), p-STAT1 (1:500), STAT1 (1:500), p-AKT (1:1,000), AKT (1:1,000), p-P65 (1:500) and P65 (1:1,000) mAb supplied by Cell Signaling Technology (Boston, MA, United States); β-actin, Vimentin (1:1,000), E-cadherin (1:1,000), MMP-2 (1:1,000), MMP-9 (1:1,000), p-Ezrin (1:1,000) and Ezrin (1:1,000) mAb were provided by Abcam (Cambridge, United Kingdom). Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies are used for the detection of primary antibodies. Finally, the membranes were scanned using a Bio-Rad Gel imaging system (Bio-Rad, United States) after visualization treatment using the ECL reagent. Protein expressions were analyzed with ImageJ software.

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

ELISA kits (Mbbiology biological, China) were used to assess the expression levels of AST, ALT, Cr, and β2-MG on the sera collected from each group. Experimental samples were taken in triplicate and repeated three times.

Immunofluorescence Analysis

Paraffin-embedded cross-sections of lung tissue from each experimental group were processed as described previously. The FITC-conjugated CD8, Cy3-conjugated Fas (1:200, Bioss, Beijing, China) and Cy3-conjugated Granzyme B mAb (1:200, Absin, Shanghai, China) were respectively used and DAPI to visualize the nuclei. Capture images of the cell signals with a fluorescent microscope.

Statistical Analysis

All data were analyzed with GraphPad Prism 7.0 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, United States) and exhibited as the means ± SD. The significance of differences was determined using the Student’s t-test and one-way ANOVA analysis of variance followed by Dunnett’s test. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

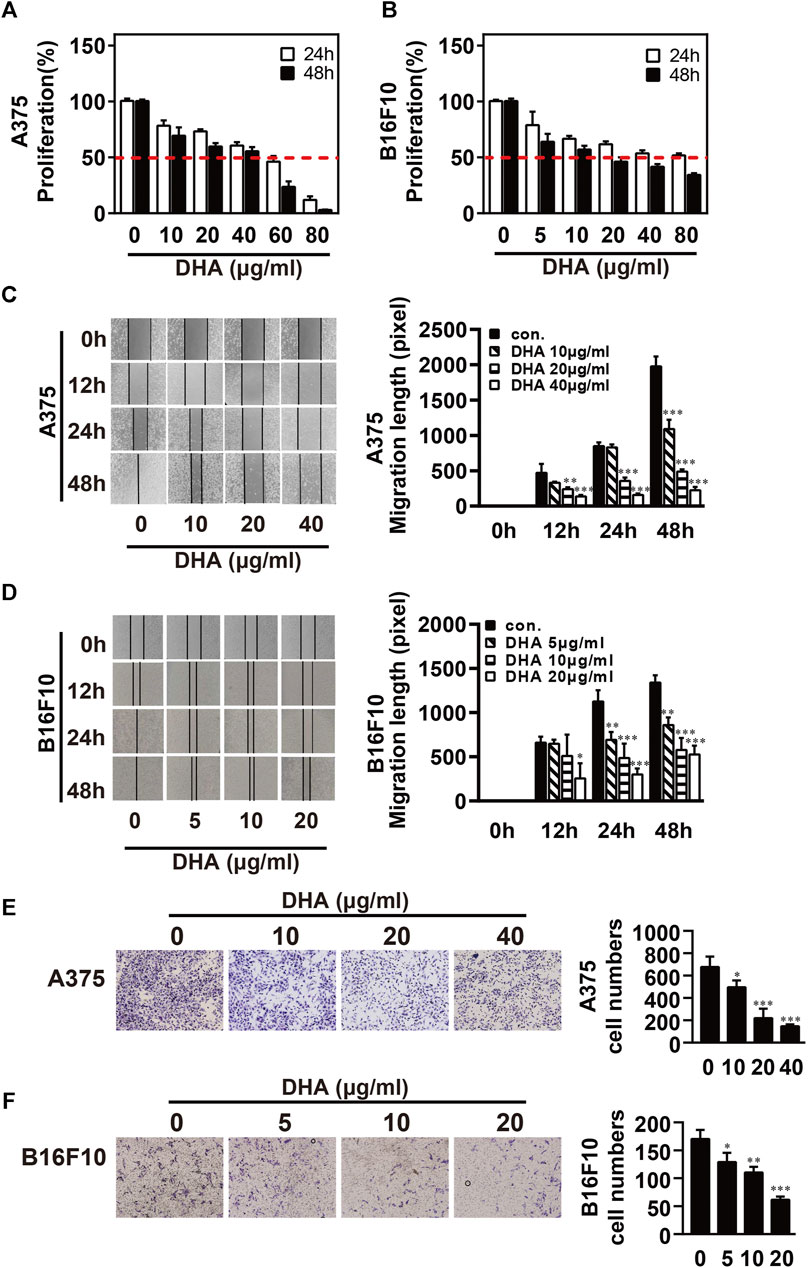

DHA Inhibits the Proliferation and Migration Ability of Melanoma Cells

To investigate the inhibitory effect of DHA on melanoma, A375 and B16F10 cells were treated with DHA by different concentrations. Cell proliferative capacity was detected by MTT or CCK-8 assay at 24 and 48 h (Figures 1A,B). The results indicated the viability of A375 and B16F10 cells was markedly reduced in a time- and dose-dependent manner. IC50 values of DHA inhibition in melanoma cells were used in subsequent experiments. To further evaluate the effect of DHA on the migration of melanoma cells, A375 and B16F10 cells were treated with different concentrations of DHA. Wound healing assay indicated that the lateral migration capacity of A375 was markedly weakened in a dose-dependent manner after DHA treatment compared to the control group (Figure 1C). As expected, the migration of B16F10 was also inhibited by DHA-treated groups (Figure 1D). Moreover, similar results were shown by transwell migration assay in A375 and B16F10 cells (Figures 1E,F). These results demonstrated that DHA markedly suppressed the proliferation and migration ability of A375 and B16F10 cells in vitro.

FIGURE 1. DHA inhibits the proliferation and migration ability of melanoma cells. (A,B) Melanoma cells were treated with different concentrations of DHA (A375: 0, 10, 20, 40 μg/ml, B16F10: 0, 5, 10, 20 μg/ml), then cell viability was assessed by MTT assay or CCK-8 assay. (C,D) Wound healing assay for demonstrating the inhibitory effect of DHA on the migration of melanoma cells. (E,F) Melanoma cells were treated with indicated concentrations of DHA for 24 h, and the invasive capacity was determined by the transwell migration assay. The experiments were repeated at least three times independently, and the data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001 compared to control group).

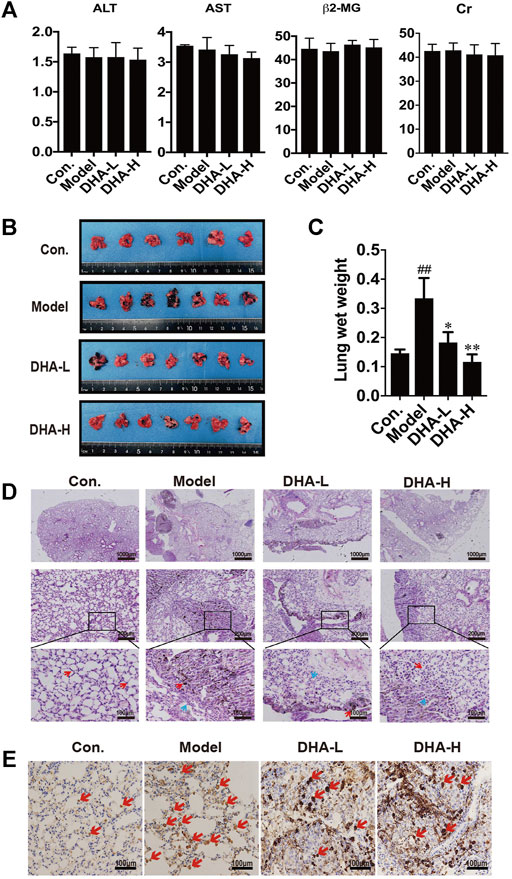

DHA Inhibits Lung Metastasis of Melanoma in vivo

To investigate the therapeutic effect of DHA in vivo, melanoma lung metastasis mouse models were established. Mice were injected with B16F10 cells via tail vein, and then DHA was administered by daily oral gavage at a dose of 25 mg/kg/day or 50 mg/kg from day 0 to day 28. All mice were observed daily for signs and weighed. The mice were sacrificed 24 h after the last gavage treatment. To examine whether DHA is poisonous to mice, ALT, AST, β2-MG and Cr expression was measured by ELISA. The results showed no significant differences in ALT, AST, β2-MG and Cr before and after DHA administration (Figure 2A). Furthermore, the mouse lungs from the model group were bearing a high burden of metastatic melanoma nodules compared with the control group. Following DHA treatment, the number of melanoma nodules was markedly decreased. It can also be seen that no large metastatic lung nodule was observed in lung tissue after high-dose DHA treatment (Figure 2B). Consistent with the above results, DHA treatment reduced the lung’s wet weight and normalized status (Figure 2C, p < 0.05).

FIGURE 2. DHA inhibits pulmonary metastasis of melanoma in mice (A) Detection of ALT, AST, β2-MG, and Cr of liver function and renal function in mouse serum by ELISA. (B) Gross images of metastatic tumor tissues and normal tissues (n ≥ 6). (C) The wet lung weight of mice was weighed (##p < 0.01 vs control group; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01 vs model group). (D) Immunopathological damage was assessed by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of the lung tissues. The red arrow indicated melanoma cells of lung metastatic; The blue arrow indicated alveolar duct structure (up×40, scale bars = 1,000 µm; middle×200, scale bars = 200 µm; down×400, scale bars = 100 µm). (E) Tumor tissues of lung metastasis were stained with Ki-67 by immunohistochemistry.

The tendency observed for lung metastases was also confirmed by histopathology. In model group, we observed multiple melanoma metastases with many infiltrating melanoma cells. Metastatic melanoma nodules were present throughout the lung, and there were numerous aggregated neoplastic foci. After DHA administration, lung metastasis of melanoma was significantly inhibited. Compared with model group, metastatic melanoma nodules were markedly reduced, accompanied by the disappearance of aggregated melanoma foci and fewer melanoma cells infiltration (Figure 2D). Moreover, the proliferation of melanoma cells was verified by IHC staining. The result showed that DHA treatment significantly reduced Ki67 positive cells in lung tissue (Figure 2E). Collectively, the above results indicated that DHA could alleviate lung metastasis of melanoma in mice.

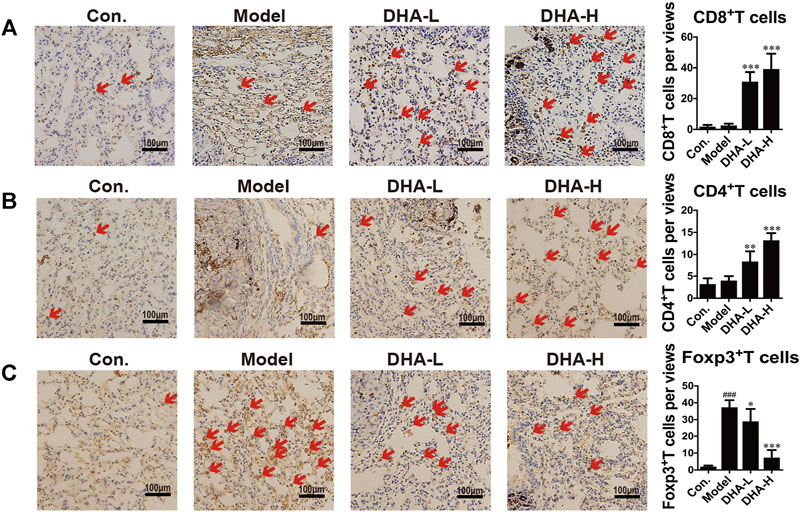

DHA Affects T Cell Subsets in Tumor Microenvironment

To verify the effect of DHA on T cell subsets in melanoma lung metastasis, IHC staining analysis was performed. Few CD8+T cells were present in the model group. On the contrary, normalization in the number of CD8+T cells was observed in DHA-treated mice (red arrows), and CD8+T cells were distributed in clusters and infiltrated into the tumor microenvironment (Figure 3A). The numbers of CD4+T cells were also markedly increased in the tumor microenvironment after DHA treatment (Figure 3B). Moreover, DHA treatment significantly reduced Foxp3+cells infiltration into tumor tissues and returned to levels similar to those in the wide-type mice (Figure 3C). Thus, DHA promoted the CD8+CTL and suppressed the Treg infiltration into the tumor microenvironment in melanoma mice.

FIGURE 3. DHA effectively suppresses melanoma severity through enhancing T cell-mediated anti-tumor immune reaction (A–C). Tumor tissues of lung metastasis were stained with A: CD8, B: CD4, and C: Foxp3 by immunohistochemical (Original magnification: ×400, scale bars = 100 µm) (###p < 0.001 vs control group; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 vs model group).

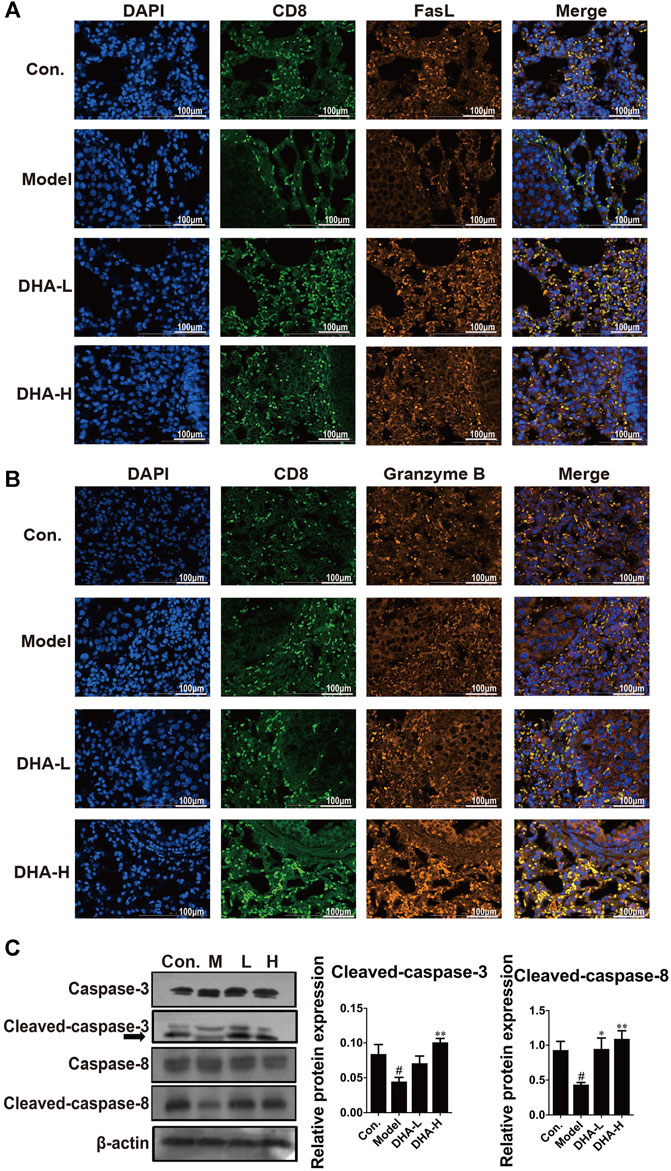

DHA Enhances the CD8+CTLs-Mediated Apoptotic Pathway

Next, we examined the expression of FasL and the secretion of Granzyme B in CD8+CTLs by immunofluorescence in tumor tissue. Compared with the control group, there were fewer FasL+CD8+CTLs cells and Granzyme B+CD8+CTLs cells in the model group. In contrast, FasL+CD8+CTLs cells were remarkably up-regulated after DHA treatment (Figure 4A). Moreover, DHA treatment markedly increased the expression of Granzyme B in the CD8+CTLs cells (Figure 4B).

FIGURE 4. DHA enhances FasL and Granzyme B and activates apoptotic pathways in CD8+CTLs. The expression levels of (A) FasL+CD8+T, and (B) Granzyme B+CD8+T before and after DHA treatment (Original magnification: ×400, scale bars = 100 µm). (C) Effect of DHA on caspase-related proteins in tumor and normal tissues. The protein expression levels of Cleaved-caspase-3, Caspase-3, Cleaved-caspase-8 and Caspase-8, as determined by Western blotting assay. β-actin was used as the loading control (#p < 0.05 vs control group; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 vs model group).

In general, FasL-induced apoptosis involves activating caspases responsible for killing tumor cells (Green and Llambi, 2015). To in-depth evaluate the cascade of apoptosis following DHA treatment, the expression of caspase proteins was determined. As expected, compared with the model group, the expression of Cleaved-caspase-3 and Cleaved-caspase-8 were enhanced in a dose-dependent way after DHA treatment (Figure 4C). These results suggested that DHA facilitated apoptosis by modulating the anti-tumor immune function of CD8+CTLs.

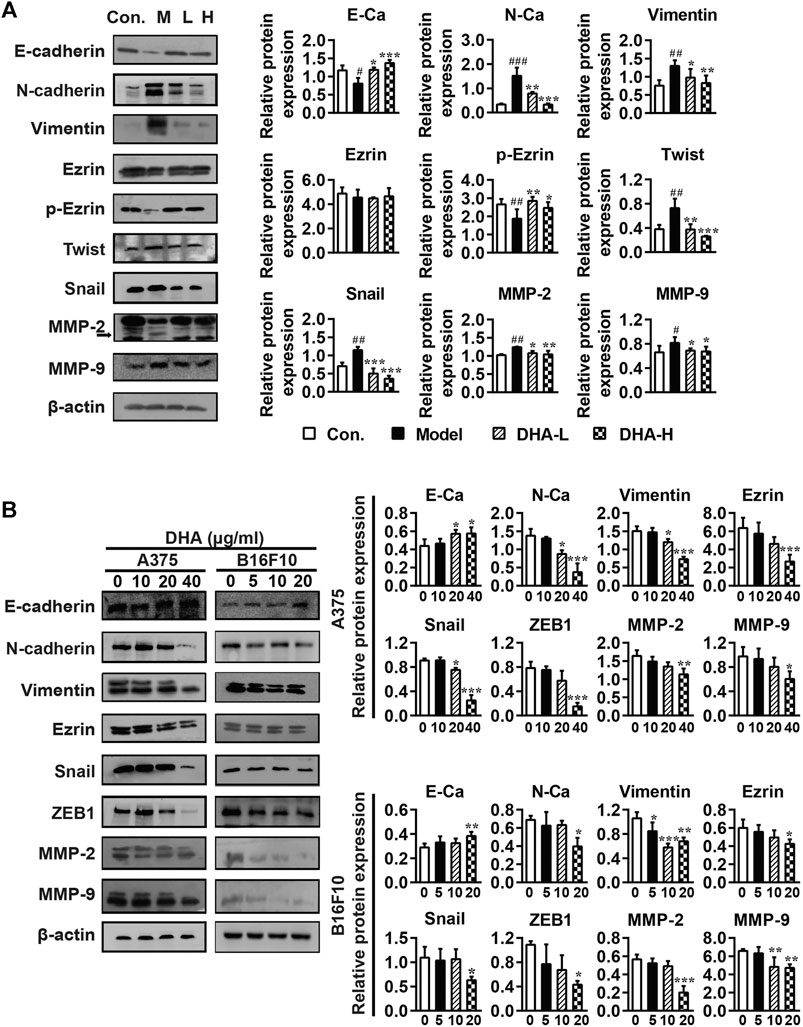

DHA Affects Cell Metastasis Through the EMT Process in Melanoma

Tumor cells undergoing EMT phenotypic changes usually involve losing epithelial properties and acquiring mesenchymal properties, reflecting enhanced metastatic and invasive properties (Caramel et al., 2013). To confirm whether the anti-metastatic properties of DHA are mediated by modulating the EMT process, specific proteins of EMT were determined by Western blotting. As shown in Figure 5A, DHA reversed EMT changes in tumor tissues, causing E-cadherin and p-Ezrin reinventing and the re-inhibition of Vimentin, N-cadherin, Snail, and Twist expression compared to the model group. Subsequently, tumor metastasis-related proteins MMP-2 and MMP-9 were determined. It was found that the expression levels of MMP-2 and MMP-9 were lower after DHA administration than in the model group.

FIGURE 5. DHA affects cell metastasis through the EMT process in melanoma (A) Effect of DHA on EMT and MMPs expression in tumor and normal tissues (#p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001 vs control group; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 vs model group). (B) Effect of different concentrations of DHA on the expression of EMT and MMPs expression in A375 cells and B16F10 cells (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001 compared to control group). β-actin was used as the loading control.

Besides, the effects of DHA on the expression of EMT and MMPs-related proteins were further demonstrated in A375 and B16F10 cells. Compare with the control group, the expression of E-cadherin was significantly increased, while the expression of Vimentin, Ezrin, N-cadherin, Snail, ZEB1, MMP-2 and MMP-9 were significantly decreased after DHA administration in A375 and B16F10 cells (Figure 5B). We also examined the morphological changes of melanoma cells after administration. It can be revealed that A375 cells are spindle-shaped and polygonal. The A375 cells with DHA treatment attained an epithelial morphology, lost cell polarity, and acquired dispersed morphology. Similarly, it could be observed that B16F10 cells formed pseudopod-like protrusions with robust migration and metastasis ability in the control group, while the DHA-treatment group tended to have the opposite morphology (Supplementary Figure 1). The above results suggested that DHA affects cell metastasis through the EMT process of melanoma in vivo and in vitro.

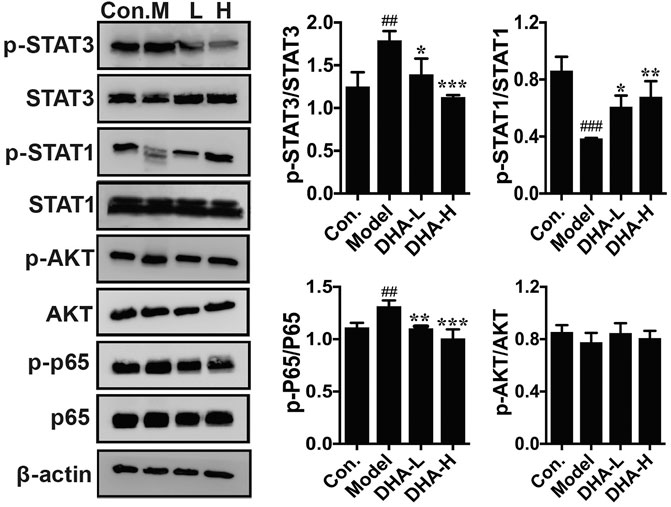

DHA Inhibits Pulmonary Metastases of Melanoma via Affecting STAT1/STAT3 Signaling Pathway

The acquisition of an aggressive and motile phenotype by metastatic tumor cells is a prerequisite for the metastatic cascade. At the same time, frequent activation of STAT is associated with EMT initiation, thereby enhancing tumor development and progression. The critical proteins of its associated signaling pathway were examined to clarify the specific signaling pathway through which DHA inhibited melanoma metastasis. The phosphorylation of STAT3 and p65 expression were markedly reduced in the DHA-treated group compared to the model group. By contrast, phosphorylation of STAT1 expression was increased significantly after DHA treatment. However, the expression of p-Akt was not remarkably different in the groups (Figure 6). The above results indicated that DHA could infect melanoma lung metastasis by impacting the STAT1/STAT3 signaling pathway.

FIGURE 6. DHA affects the STAT signaling pathway in pulmonary metastases from melanoma. The protein levels of p-STAT3/STAT3, p-STAT1/STAT1, p-Akt/Akt, and p-P65/P65 were detected by western blot assay (##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001 vs control group; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 vs model group).

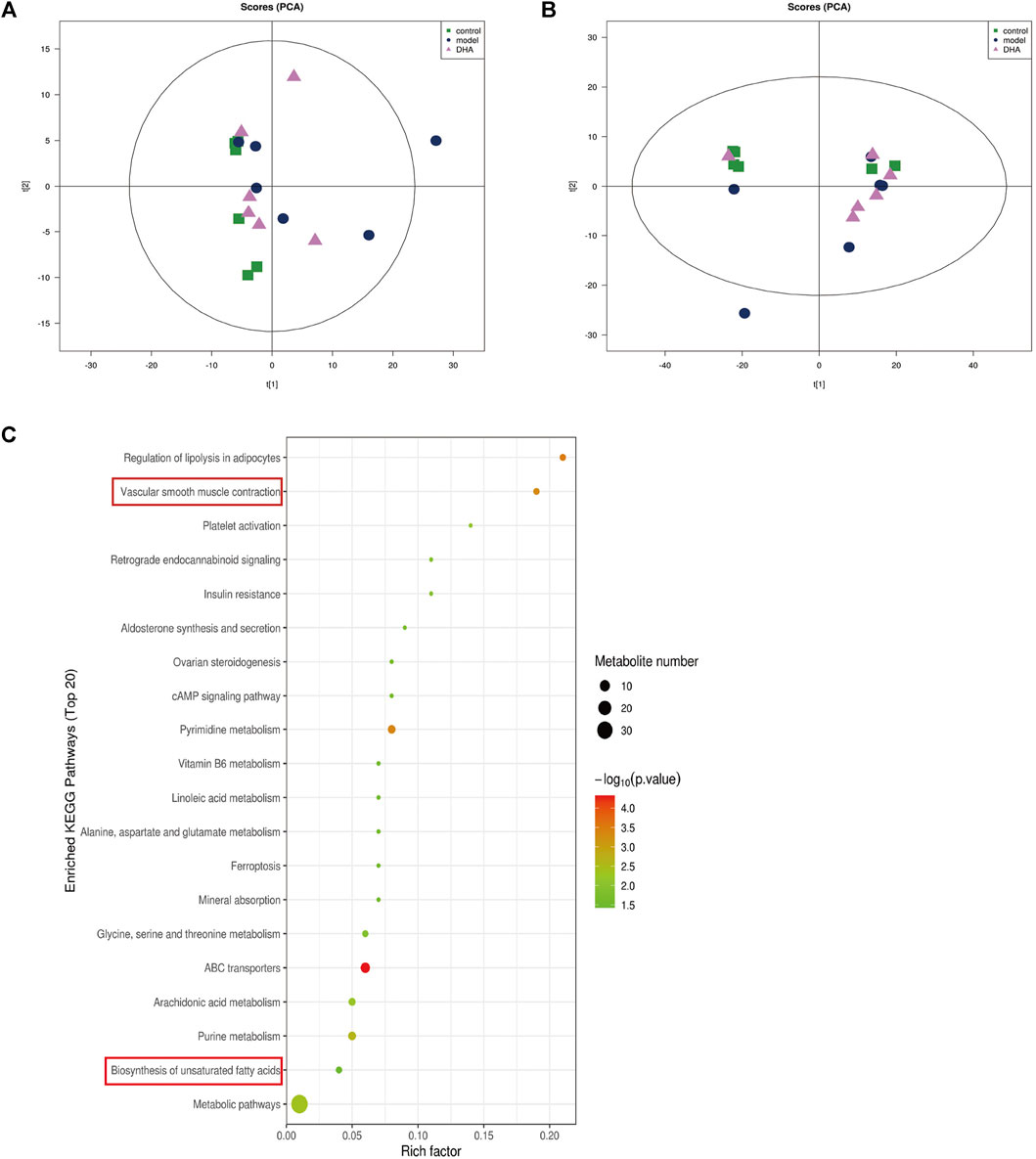

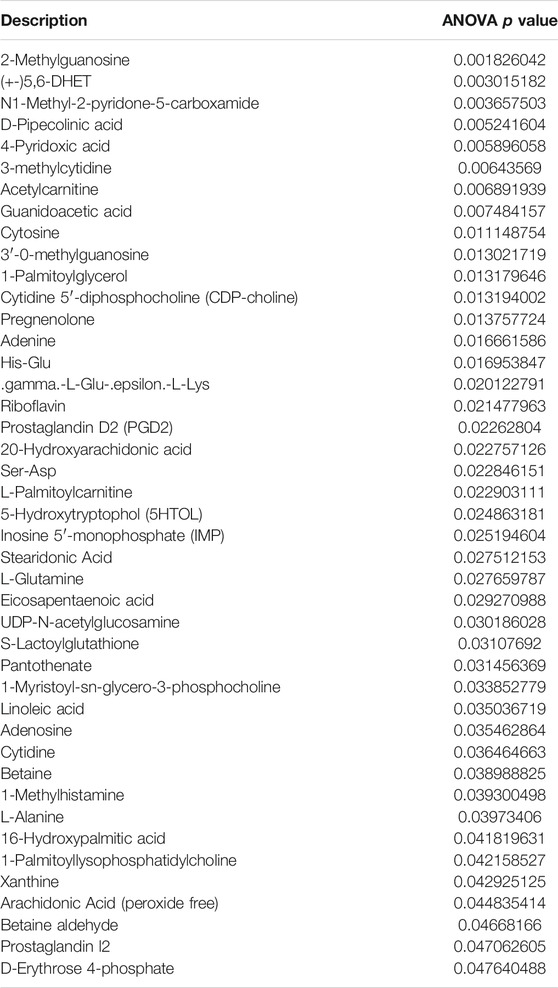

DHA Regulates Metabolic Pathways in Lung Metastasis of Melanoma in Mice

Recent studies have demonstrated that metabolism is significantly associated with tumorigenesis and metastasis (Luengo et al., 2017; Kosmopoulou et al., 2020; Li et al., 2016). Based on the strategy of tumor immunotherapy with metabolic regulation, UHPLC-Q-TOF-MS technology was used. The PCA method used the corrected positive and negative ion data to explore lung tissue metabolic spectrum changes. The results showed that the groups were quite different, and each group was separated (Figures 7A,B). Through untargeted metabolomic analysis, 43 metabolites differentiators were found (Table 1). Among them, compared with the control group, 5 notable metabolites (1-Palmitoylglycerol, Adenine,.gamma. -L-Glu-. epsilon. -L-Lys, UDP-N-acetylglucosamine, D-Erythrose 4-phosphate) were significantly increased in the model group, while DHA treatment markedly downgraded the 1-Palmitoylglycerol, Adenine,.gamma. -L-Glu-. epsilon. -L-Lys, UDP-N-acetylglucosamine, and D-Erythrose 4-phosphate expression levels. By contrast, 7 notable metabolites such as Eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), Arachidonic Acid, (+-)5,6-DHET, D-Pipecolinic acid, Acetylcarnitine, 3′-O-methylguanosine, Prostaglandin D2 (PGD2) were significantly decreased in the model group than that control group, while DHA administration markedly up-regulated the 7 notable metabolites expression levels (data not shown). PGD2 was found to be a potent inhibitor of melanoma cell replication in vitro (Stringfellow and Fitzpatrick, 1979; Bhuyan et al., 1986), and EPA has proved a potential anti-melanoma metabolite (Pappalardo et al., 2015). In the current study, the KEGG pathway enrichment map showed that PGD2 belongs to the Vascular smooth muscle contraction metabolic pathway and EPA belongs to the Biosynthesis of unsaturated fatty acids metabolic pathway, the P. values of the KEGG profile shown that they are significantly correlated (Figure 7C). The results indicated that non-targeted metabolomics could screen out the differential metabolites in lung tissues after DHA treatment and understand the involved pathways through the differential metabolites, which makes a preliminary screening for our subsequent experiments on specific targets of DHA treatment of melanoma lung metastasis, as well as for the next step in our experimental program.

FIGURE 7. DHA affects cancer tissue metabolism in lung metastasis of melanoma in mice. Mice were sacrificed after 28 days of continuous gavage treatment, and lung tissue was collected for non-targeted metabolomics analysis (A) PCA atlas of cancer tissue samples in positive ion mode in each group. (B) OPLS-DA atlas of tumor tissue samples in positive ion mode in each group. (C) DHA affected metabolic pathways of tumor tissue in mice with melanoma lung metastasis.

TABLE 1. The non-targeted metabolomics analysis identified 43 differential metabolites, focusing on Prostaglandin D2 and Eicosapentaenoic acid, marked with red arrows.

Discussion

At present, more and more studies focus on elucidating the molecular mechanism of DHA’s anticancer activity. The advantages of DHA as a new class of anti-tumor agents are evident, including good tolerance, low cross-resistance (Sá et al., 2018), low toxicity to normal tissues and cells (Xu et al., 2016), and synergistic with many other conventional anti-tumor drugs (Feng et al., 2014). Oral DHA is rapidly absorbed in the gastrointestinal tract and reaches Cmax, approximately 1–2 h after administration (Dai et al., 2019). The multiple bioactivities of DHA in cancer include inhibition of tumor proliferation, promotion of apoptosis, and suppression of angiogenesis and tumor metastasis. Studies suggested that DHA mediates the microRNA-mRNA regulatory network to promote both apoptosis and angiogenesis in pancreatic cancer (Li et al., 2016). In addition, DHA impedes colony formation, proliferation and induction of ferry death in lung cancer cells by blocking the PRIM2/SLC7A11 axis (Yuan et al., 2020). In our research, DHA suppressed the proliferation, migration and metastasis of melanoma cells in vitro and decreased the severity of melanoma and histopathological changes in the lungs of mice. Furthermore, DHA treatment significantly reversed the EMT changes in melanoma cells, affecting the expression of the associated proteins.

EMT has a determinant role in tumorigenesis and metastasis (Floor et al., 2011). DHA inhibited EMT of ovarian cancer, thereby reducing its metastasis to the lung, liver and intestine (Bao, 2011; Liu et al., 2018). In breast cancer, DHA inhibits EMT by reducing TGF-β production and decreasing phosphorylation of Smad2 and Smad3 (Li et al., 2020). In a similar vein, Ju et al. observed that DHA inhibited breast cancer metastasis by reducing the production of MMPs, TGF-β, and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) (Ju et al., 2018). It has been confirmed that activation of STAT3 could induce EMTs and MMPs and may cause a progressive shift in cell phenotype towards a mesenchymal morphology with implications for the invasive, intravascular and extravascular steps of the metastatic cascade (Rokavec et al., 2014). In this study, treatment with DHA significantly reduced STAT3 phosphorylation. In addition, Wang et al. found that IFNα2b markedly regulated the STAT1/STAT3 balance in host lymphocytes and melanoma cells. The pSTAT1/pSTAT3 ratio in tumor cells could be a potent predictor for assessing the clinical treatment of melanoma (Wang et al., 2007). Furthermore, Khan et al. demonstrated that overexpression of the ACE C domain in macrophages induced their differentiation into a distinct M1 phenotype in response to melanoma stimulation and increased activation of NF-κB and STAT1, which blocked the activation STAT3 and STAT6 (Khan et al., 2019). Interestingly, in our study, phosphorylation of STAT3 and p65 expression were markedly reduced in the DHA group. By contrast, phosphorylation of STAT1 expression was significantly enhanced after DHA treatment. In addition, DHA also has been shown to inhibit the development of non-small cell lung cancer metastasis by inhibiting the NF-κB/GLUT1 axis (Jiang et al., 2016) and has been demonstrated to enhance the anti-pancreatic cancer potential of gemcitabine via inhibition of the NF-κB axis (Wang et al., 2010). Therefore, we suggest that DHA suppressed melanoma invasiveness by reducing MMPs and EMT activity and expression through inhibiting the constitutive activities STAT3/NF-κB and accelerating the STAT1.

Activated CTLs are the most potent immune effector cells in the body, exerting a robust anti-tumor immune response through various pathways. CTLs act by producing anti-tumor cytokines like perforin and granzyme or by-products killing tumor cells via the Fas/FasL pathway. In pancreatic cancer, Zhou et al. found that DHA enhanced the activity of T cells and promoted the secretion of perforin, Granzyme B, and IFN-γ (Zhou et al., 2013). Fas and its receptors FasL and caspase-3/8 are components of the pathway that controls the acceptance of apoptosis in tumor cells (Nagata and Golstein, 1995). Apoptosis can be actuated by extrinsic pathways, which include the enactment of cell surface death receptors, or intrinsic pathways, in which modifications within the astuteness of the mitochondrial membrane initiate the discharge of cytochromes. These pathways focalize at the level of effector caspases. When activated, the effector caspases then cleave the cytoskeleton and nuclear proteins, such as PARP, thus starting the cytolytic program (Fulda and Debatin, 2006). Yeo et al. found that DHA promotes caspase-dependent apoptosis of hepatocellular carcinoma SK-Hep-1 cells by a specific protein 1 pathway (Im et al., 2018). Similar to our results, treatment with DHA markedly activated FasL, cleaved caspase-3, and cleaved caspase-8 in the lung metastasis model, supporting the assumption that tumor death occurred in a manner consistent with apoptosis in this study. In addition, the balance of Treg/CTLs was significantly associated with anti-tumor immunity. Treg suppresses the pernicious effect of CTLs by secreting IL-10 and TGF-β, thus realizing tumor immune escape (Ohue and Nishikawa, 2019). It has been shown that DHA inhibits the production of TGF-β (Yao et al., 2018; Li et al., 2020) and TNF-α (Su et al., 2019). Zhang et al. revealed that DHA could enhance the proportion of Treg and CD8+T cells and decrease the expression of proinflammatory cytokines (Zhang et al., 2020). Noori et al. observed that, in pancreatic cancer, DHA had the function of inhibiting Treg and increasing IFN-γ production (Noori and Hassan, 2011). Therefore, it is likely possible that DHA influences Treg/CD8+CTL cells’ balance and inhibits the induction of caspase-dependent apoptosis in the tumor microenvironment. The utility of cytokines in melanoma lung metastasis is to be further examined.

The tumor microenvironment is always accompanied by metabolic processes different from normal cells. Batista et al. used nuclear magnetic resonance to study serum metabolomics from patients with cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma and found many metabolites involving multiple metabolic pathways (Batista et al., 2018). In our experiment, Metabolomics analysis indicated that PGD2 and EPA significantly increased after DHA administration, which is closely related to suppressing tumors metastasis (Table 1). Shyu et al. have revealed that PGD2 was co-localized with H-rev107, suppressed testis cell migration and invasion by the PGD2-cAMP-SOX9 signal pathway (Shyu et al., 2013).

Furthermore, PGD2 levels in cystadenocarcinoma of the ovary have been demonstrated to impede the growth of ovarian cancer cells in vitro and in vivo and prolong the survival of nude mice with these tumors (Kikuchi et al., 1986). Furthermore, Stringfellow et al. found that the PGD2 formed by malignant melanoma cells in vitro was inverse proportion to their metastatic potentials. PGD2 also controls pulmonary metastasis of malignant melanoma (Pappalardo et al., 2015). EPA belongs to a family of long-chain n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, commonly used as a nutritional supplement to treat tumor-related cachexia (Sharma et al., 2005). It was previously proposed that the EPA can directly influence tumor development, inhibit tumor cell migration, and promote apoptosis, thereby affecting tumor metastasis. Wan et al. have shown that EPA induces growth suppression on epithelial ovarian cancer cells through inhibiting PPAR and p53 overexpression (Wan et al., 2016). Yamada et al. indicated that the EPA interacted with the activated C kinase 1 receptor and inhibited melanoma cell proliferation via protein kinase C signaling (Yamada et al., 2019). Our dates indicated that PGD2 and EPA were markedly reduced in the model group, but there was a regression trend after DHA administration. These results suggest that DHA treatment for lung metastasis of melanoma may be related to disturbance of metabolism in vivo to some extent. Due to the limitations of untargeted metabolomics, this experiment only preliminarily revealed the possible biological material basis of melanoma lung metastasis, suggesting that DHA inhibition of melanoma lung metastasis may be related to amino acid metabolism, fatty acid metabolism, and other small molecule substance metabolism. However, whether the metabolism of other body fluids or tissues, such as blood, urine, and liver, is different or related to lung tissue metabolism in the lung metastasis model of melanoma requires further testing.

In summary, our study shows that DHA has anti-proliferative and anti-metastatic effects on melanoma cells, and confirms these effects in a mouse model of lung metastasis. Our results provide the experimental basis for the application of DHA in the treatment of melanoma and as a valuable drug for the treatment of metastatic melanoma.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics Statement

The animal study was reviewed and approved by the Yanbian University ethicalguidelines for animal care and use.

Author Contributions

GJ designed the general framework of this research and guided the experiment. XR guided the investigation and analyzed the data. QZ and LJ jointly completed these experiments and analyzed the data. QJ, QW, MS, QY, HL, FL, and HL assisted in tissue sample collection.

Funding

This research was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant numbers 81960305, 61671098 and 81460255.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphar.2021.727275/full#supplementary-material

References

Bao, S. (2011). Dihydroartiminisin Inhibits the Growth and Metastasis of Epithelial Ovarian Cancer. Oncol. Rep. 27(1), 101–108. doi:10.3892/or.2011.1505

Batista, A. D., Barros, C. J. P., Costa, T. B. B. C., de Godoy, M. M. G., Silva, R. D., Santos, J. C., et al. (2018). Proton Nuclear Magnetic Resonance-Based Metabonomic Models for Non-invasive Diagnosis of Liver Fibrosis in Chronic Hepatitis C: Optimizing the Classification of Intermediate Fibrosis. World J. Hepatol. 10, 105–115. doi:10.4254/wjh.v10.i1.105

Bhuyan, B. K., Badiner, G. J., Adams, E. G., and Chase, R. (1986). Cytotoxicity of Combinations of Prostaglandin D2 (PGD2) and Antitumor Drugs for B16 Melanoma Cells in Culture. Invest. New Drugs 4, 315–323. doi:10.1007/BF00173504

Caramel, J., Papadogeorgakis, E., Hill, L., Browne, G. J., Richard, G., Wierinckx, A., et al. (2013). A Switch in the Expression of Embryonic EMT-Inducers Drives the Development of Malignant Melanoma. Cancer Cell 24, 466–480. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2013.08.018

Cheong, D. H. J., Tan, D. W. S., Wong, F. W. S., and Tran, T. (2020). Anti-malarial Drug, Artemisinin and its Derivatives for the Treatment of Respiratory Diseases. Pharmacol. Res. 158, 104901. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2020.104901

Dai, T., Jiang, W., Guo, Z., Xie, Y., and Dai, R. (2019). Comparison of In Vitro/In Vivo Blood Distribution and Pharmacokinetics of Artemisinin, Artemether and Dihydroartemisinin in Rats. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 162, 140–148. doi:10.1016/j.jpba.2018.09.024

Efferth, T., and Kaina, B. (2010). Toxicity of the Antimalarial Artemisinin and its Dervatives. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 40, 405–421. doi:10.3109/10408441003610571

Feng, X., Li, L., Jiang, H., Jiang, K., Jin, Y., and Zheng, J. (2014). Dihydroartemisinin Potentiates the Anticancer Effect of Cisplatin via mTOR Inhibition in Cisplatin-Resistant Ovarian Cancer Cells: Involvement of Apoptosis and Autophagy. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 444, 376–381. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.01.053

Ferlay, J., Soerjomataram, I., Dikshit, R., Eser, S., Mathers, C., Rebelo, M., et al. (2015). Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: Sources, Methods and Major Patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int. J. Cancer 136, E359–E386. doi:10.1002/ijc.29210

Floor, S., van Staveren, W. C., Larsimont, D., Dumont, J. E., and Maenhaut, C. (2011). Cancer Cells in Epithelial-To-Mesenchymal Transition and Tumor-Propagating-Cancer Stem Cells: Distinct, Overlapping or Same Populations. Oncogene 30, 4609–4621. doi:10.1038/onc.2011.184

Franke, V., Berger, D. M. S., Klop, W. M. C., van der Hiel, B., van de Wiel, B. A., Ter Meulen, S., et al. (2019). High Response Rates for T-VEC in Early Metastatic Melanoma (Stage IIIB/C-IVM1a). Int. J. Cancer 145, 974–978. doi:10.1002/ijc.32172

Fulda, S., and Debatin, K. M. (2006). Extrinsic versus Intrinsic Apoptosis Pathways in Anticancer Chemotherapy. Oncogene 25, 4798–4811. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1209608

Green, D. R., and Llambi, F. (2015). Cell Death Signaling. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 7, a006080. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a006080

Ho, W. E., Peh, H. Y., Chan, T. K., and Wong, W. S. (2014). Artemisinins: Pharmacological Actions beyond Anti-malarial. Pharmacol. Ther. 142, 126–139. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2013.12.001

Im, E., Yeo, C., Lee, H. J., and Lee, E. O. (2018). Dihydroartemisinin Induced Caspase-dependent Apoptosis through Inhibiting the Specificity Protein 1 Pathway in Hepatocellular Carcinoma SK-Hep-1 Cells. Life Sci. 192, 286–292. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2017.11.008

Jiang, J., Geng, G., Yu, X., Liu, H., Gao, J., An, H., et al. (2016). Repurposing the Anti-malarial Drug Dihydroartemisinin Suppresses Metastasis of Non-small-cell Lung Cancer via Inhibiting NF-Κb/glut1 axis. Oncotarget 7, 87271–87283. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.13536

Ju, R. J., Cheng, L., Peng, X. M., Wang, T., Li, C. Q., Song, X. L., et al. (2018). Octreotide-modified Liposomes Containing Daunorubicin and Dihydroartemisinin for Treatment of Invasive Breast Cancer. Artif. Cell Nanomed Biotechnol 46, 616–628. doi:10.1080/21691401.2018.1433187

Khan, Z., Cao, D. Y., Giani, J. F., Bernstein, E. A., Veiras, L. C., Fuchs, S., et al. (2019). Overexpression of the C-Domain of Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Reduces Melanoma Growth by Stimulating M1 Macrophage Polarization. J. Biol. Chem. 294, 4368–4380. doi:10.1074/jbc.RA118.006275

Kikuchi, Y., Miyauchi, M., Oomori, K., Kita, T., Kizawa, I., and Kato, K. (1986). Inhibition of Human Ovarian Cancer Cell Growth In Vitro and in Nude Mice by Prostaglandin D2. Cancer Res. 46, 3364–3366.

Kosmopoulou, M., Giannopoulou, A. F., Iliou, A., Benaki, D., Panagiotakis, A., Velentzas, A. D., et al. (2020). Human Melanoma-Cell Metabolic Profiling: Identification of Novel Biomarkers Indicating Metastasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 2436. doi:10.3390/ijms21072436

Li, X., Ba, Q., Liu, Y., Yue, Q., Chen, P., Li, J., et al. (2017). Dihydroartemisinin Selectively Inhibits PDGFRα-Positive Ovarian Cancer Growth and Metastasis through Inducing Degradation of PDGFRα Protein. Cell Discov 3, 17042. doi:10.1038/celldisc.2017.42

Li, Y., Wang, Y., Kong, R., Xue, D., Pan, S., Chen, H., et al. (2016). Dihydroartemisinin Suppresses Pancreatic Cancer Cells via a microRNA-mRNA Regulatory Network. Oncotarget 7, 62460–62473. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.11517

Li, Y., Zhou, X., Liu, J., Gao, N., Yang, R., Wang, Q., et al. (2020). Dihydroartemisinin Inhibits the Tumorigenesis and Metastasis of Breast Cancer via Downregulating CIZ1 Expression Associated with TGF-Β1 Signaling. Life Sci. 248, 117454. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2020.117454

Lin, A. J., Lee, M., and Klayman, D. L. (1989). Antimalarial Activity of New Water-Soluble Dihydroartemisinin Derivatives. 2. Stereospecificity of the Ether Side Chain. J. Med. Chem. 32, 1249–1252. doi:10.1021/jm00126a017

Liu, Y., Gao, S., Zhu, J., Zheng, Y., Zhang, H., and Sun, H. (2018). Dihydroartemisinin Induces Apoptosis and Inhibits Proliferation, Migration, and Invasion in Epithelial Ovarian Cancer via Inhibition of the Hedgehog Signaling Pathway. Cancer Med. 7, 5704–5715. doi:10.1002/cam4.1827

Luengo, A., Gui, D. Y., and Vander Heiden, M. G. (2017). Targeting Metabolism for Cancer Therapy. Cell Chem. Biol. 24, 1161–1180. doi:10.1016/j.chembiol.2017.08.028

Nagata, S., and Golstein, P. (1995). The Fas Death Factor. Science 267, 1449–1456. doi:10.1126/science.7533326

Namdar, A., Mirzaei, R., Memarnejadian, A., Boghosian, R., Samadi, M., Mirzaei, H. R., et al. (2018). Prophylactic DNA Vaccine Targeting Foxp3+ Regulatory T Cells Depletes Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells and Improves Anti-melanoma Immune Responses in a Murine Model. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 67, 367–379. doi:10.1007/s00262-017-2088-6

Noori, S., and Hassan, Z. M. (2011). Dihydroartemisinin Shift the Immune Response towards Th1, Inhibit the Tumor Growth In Vitro and In Vivo. Cell. Immunol. 271, 67–72. doi:10.1016/j.cellimm.2011.06.008

Ohue, Y., and Nishikawa, H. (2019). Regulatory T (Treg) Cells in Cancer: Can Treg Cells Be a New Therapeutic Target? Cancer Sci. 110, 2080–2089. doi:10.1111/cas.14069

Paccez, J. D., Duncan, K., Sekar, D., Correa, R. G., Wang, Y., Gu, X., et al. (2019). Dihydroartemisinin Inhibits Prostate Cancer via JARID2/miR-7/miR-34a-dependent Downregulation of Axl. Oncogenesis 8, 14. doi:10.1038/s41389-019-0122-6

Pappalardo, G., Almeida, A., and Ravasco, P. (2015). Eicosapentaenoic Acid in Cancer Improves Body Composition and Modulates Metabolism. Nutrition 31, 549–555. doi:10.1016/j.nut.2014.12.002

Pollack, M. H., Betof, A., Dearden, H., Rapazzo, K., Valentine, I., Brohl, A. S., et al. (2018). Safety of Resuming Anti-PD-1 in Patients with Immune-Related Adverse Events (irAEs) during Combined Anti-CTLA-4 and Anti-PD1 in Metastatic Melanoma. Ann. Oncol. 29, 250–255. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdx642

Rokavec, M., Öner, M. G., Li, H., Jackstadt, R., Jiang, L., Lodygin, D., et al. (2014). IL-6R/STAT3/miR-34a Feedback Loop Promotes EMT-Mediated Colorectal Cancer Invasion and Metastasis. J. Clin. Invest. 124, 1853–1867. doi:10.1172/JCI73531

Sá, J. M., Kaslow, S. R., Krause, M. A., Melendez-Muniz, V. A., Salzman, R. E., Kite, W. A., et al. (2018). Artemisinin Resistance Phenotypes and K13 Inheritance in a Plasmodium Falciparum Cross and Aotus Model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 115, 12513–12518. doi:10.1073/pnas.1813386115

Sharma, A., Belna, J., Logan, J., Espat, J., and Hurteau, J. A. (2005). The Effects of Omega-3 Fatty Acids on Growth Regulation of Epithelial Ovarian Cancer Cell Lines. Gynecol. Oncol. 99, 58–64. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.05.024

Shyu, R. Y., Wu, C. C., Wang, C. H., Tsai, T. C., Wang, L. K., Chen, M. L., et al. (2013). H-rev107 Regulates Prostaglandin D2 Synthase-Mediated Suppression of Cellular Invasion in Testicular Cancer Cells. J. Biomed. Sci. 20, 30. doi:10.1186/1423-0127-20-30

Simiczyjew, A., Dratkiewicz, E., Mazurkiewicz, J., Ziętek, M., Matkowski, R., and Nowak, D. (2020). The Influence of Tumor Microenvironment on Immune Escape of Melanoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 8359. doi:10.3390/ijms21218359

Stringfellow, D. A., and Fitzpatrick, F. A. (1979). Prostaglandin D2 Controls Pulmonary Metastasis of Malignant Melanoma Cells. Nature 282, 76–78. doi:10.1038/282076a0

Su, T., Li, F., Guan, J., Liu, L., Huang, P., Wang, Y., et al. (2019). Artemisinin and its Derivatives Prevent Helicobacter Pylori-Induced Gastric Carcinogenesis via Inhibition of NF-Κb Signaling. Phytomedicine 63, 152968. doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2019.152968

Thongchot, S., Vidoni, C., Ferraresi, A., Loilome, W., Yongvanit, P., Namwat, N., et al. (2018). Dihydroartemisinin Induces Apoptosis and Autophagy-dependent Cell Death in Cholangiocarcinoma through a DAPK1-BECLIN1 Pathway. Mol. Carcinog. 57, 1735–1750. doi:10.1002/mc.22893

Topalian, S. L., Hodi, F. S., Brahmer, J. R., Gettinger, S. N., Smith, D. C., McDermott, D. F., et al. (2019). Five-Year Survival and Correlates Among Patients with Advanced Melanoma, Renal Cell Carcinoma, or Non-small Cell Lung Cancer Treated with NivolumabFive-Year Survival and Correlates Among Patients with Advanced Melanoma, Renal Cell Carcinoma, or Non–small Cell Lung Cancer Treated with Nivolumab. JAMA Oncol. 5, 1411. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.2187

Wan, X. H., Fu, X., and Ababaikeli, G. (2016). Docosahexaenoic Acid Induces Growth Suppression on Epithelial Ovarian Cancer Cells More Effectively Than Eicosapentaenoic Acid. Nutr. Cancer 68, 320–327. doi:10.1080/01635581.2016.1142581

Wang, S. J., Gao, Y., Chen, H., Kong, R., Jiang, H. C., Pan, S. H., et al. (2010). Dihydroartemisinin Inactivates NF-kappaB and Potentiates the Anti-tumor Effect of Gemcitabine on Pancreatic Cancer Both In Vitro and In Vivo. Cancer Lett. 293, 99–108. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2010.01.001

Wang, W., Edington, H. D., Rao, U. N., Jukic, D. M., Land, S. R., Ferrone, S., et al. (2007). Modulation of Signal Transducers and Activators of Transcription 1 and 3 Signaling in Melanoma by High-Dose IFNalpha2b. Clin. Cancer Res. 13, 1523–1531. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1387

Xu, C. C., Deng, T., Fan, M. L., Lv, W. B., Liu, J. H., and Yu, B. Y. (2016). Synthesis and In Vitro Antitumor Evaluation of Dihydroartemisinin-Cinnamic Acid Ester Derivatives. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 107, 192–203. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2015.11.003

Yamada, H., Hakozaki, M., Uemura, A., and Yamashita, T. (2019). Effect of Fatty Acids on Melanogenesis and Tumor Cell Growth in Melanoma Cells. J. Lipid Res. 60, 1491–1502. doi:10.1194/jlr.M090712

Yan, X., Li, P., Zhan, Y., Qi, M., Liu, J., An, Z., et al. (2018). Dihydroartemisinin Suppresses STAT3 Signaling and Mcl-1 and Survivin Expression to Potentiate ABT-263-Induced Apoptosis in Non-small Cell Lung Cancer Cells Harboring EGFR or RAS Mutation. Biochem. Pharmacol. 150, 72–85. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2018.01.031

Yao, Y., Guo, Q., Cao, Y., Qiu, Y., Tan, R., Yu, Z., et al. (2018). Artemisinin Derivatives Inactivate Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts through Suppressing TGF-β Signaling in Breast Cancer. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 37, 282. doi:10.1186/s13046-018-0960-7

Yu, R., Jin, L., Li, F., Fujimoto, M., Wei, Q., Lin, Z., et al. (2020). Dihydroartemisinin Inhibits Melanoma by Regulating CTL/Treg Anti-tumor Immunity and STAT3-Mediated Apoptosis via IL-10 Dependent Manner. J. Dermatol. Sci. 99, 193–202. doi:10.1016/j.jdermsci.2020.08.001

Yuan, B., Liao, F., Shi, Z. Z., Ren, Y., Deng, X. L., Yang, T. T., et al. (2020). Dihydroartemisinin Inhibits the Proliferation, Colony Formation and Induces Ferroptosis of Lung Cancer Cells by Inhibiting PRIM2/SLC7A11 Axis. Onco Targets Ther. 13, 10829–10840. doi:10.2147/OTT.S248492

Zhang, T., Zhang, Y., Jiang, N., Zhao, X., Sang, X., Yang, N., et al. (2020). Dihydroartemisinin Regulates the Immune System by Promotion of CD8+ T Lymphocytes and Suppression of B Cell Responses. Sci. China Life Sci. 63, 737–749. doi:10.1007/s11427-019-9550-4

Keywords: dihydroartemisinin, melanoma, metastasis, EMT, tumor microenvironment

Citation: Zhang Q, Jin L, Jin Q, Wei Q, Sun M, Yue Q, Liu H, Li F, Li H, Ren X and Jin G (2021) Inhibitory Effect of Dihydroartemisinin on the Proliferation and Migration of Melanoma Cells and Experimental Lung Metastasis From Melanoma in Mice. Front. Pharmacol. 12:727275. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.727275

Received: 18 June 2021; Accepted: 23 August 2021;

Published: 02 September 2021.

Edited by:

Kunlin Zhang, Institute of Psychology (CAS), ChinaReviewed by:

Fu Peng, Sichuan University, ChinaLinli Zhang, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, China

Copyright © 2021 Zhang, Jin, Jin, Wei, Sun, Yue, Liu, Li, Li, Ren and Jin. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xiangshan Ren, cmVueHNoQHlidS5lZHUuY24=; Guihua Jin, Z2hqaW5AeWJ1LmVkdS5jbg==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Qi Zhang1†

Qi Zhang1† Linbo Jin

Linbo Jin Quanxin Jin

Quanxin Jin Fangfang Li

Fangfang Li Guihua Jin

Guihua Jin