Abstract

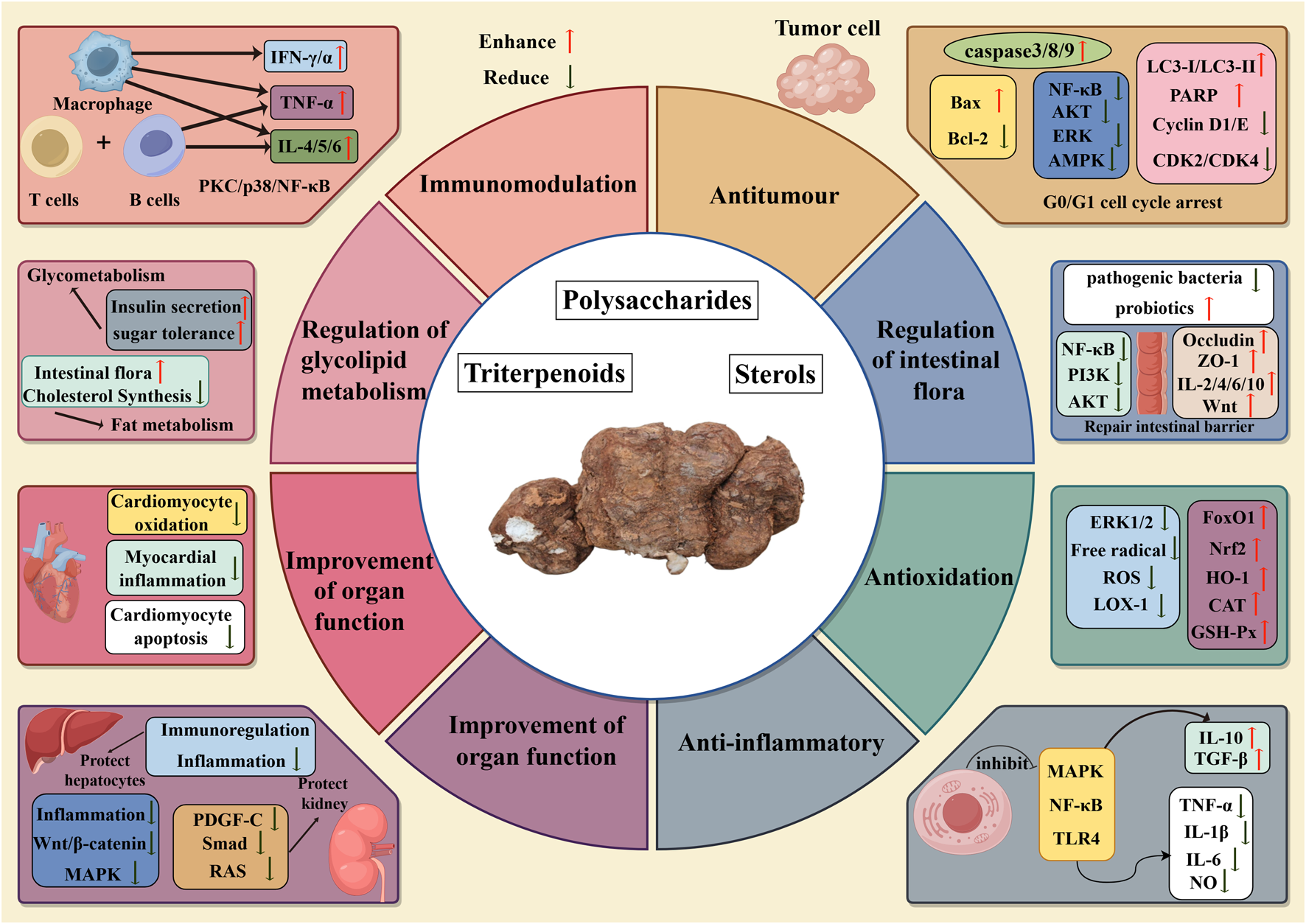

The Latin name of Wolfiporia cocos is Wolfiporia cocos (F.A. Wolf) Ryvarden & Gilb, it a medicinal and edible mushroom belonging to the family Polyporaceae. Traditional Chinese medicine believes that it can strengthen the spleen, diuretic, tranquillise the mind and dispel dampness. So far, the chemical and active metabolites isolated and extracted from Wolfiporia cocos are mainly polysaccharides, triterpenoids, and sterols. Modern pharmacology has found that these chemical and active metabolites have a wide range of pharmacological effects, including antitumour, antioxidation, anti-inflammatory, immunomodulation, regulation of intestinal flora, regulation of glycolipid metabolism, and improvement of organ function. By applying Poria cocos, Poria, Wolfiporia cocos, Wolfiporia cocos (F.A. Wolf) Ryvarden & Gilb as search terms, we searched all the relevant studies on Poria cocos from Web of Science and PubMed databases and classified these categories of chemical and active metabolites according to the main research content of each literature and summarized its mechanism of action, updated its latest research results, and discussed the direction of further research in the future to provide a better reference for future clinical applications with better therapeutic effects and potential medicinal value.

1 Introduction

Wolfiporia cocos (F.A. Wolf) Ryvarden & Gilb. is the current accepted Latin name, and it formerly was known as MacrohyWolfiporia cocos (Schwein.) I. Johans. & Ryvarden., Poria cocos (syn. Wolfiporia cocos), Poria cocos F.A. Wolf, Pachyma cocos (Schwein.) Fr., and Sclerotium cocos Schwein (Li et al., 2022), which is known as “Fuling” in China and is now widely used in China, Japan and other parts of Asia. It is a healthcare edible mushroom belonging to the family Polyporaceae, which grows on the roots of pine trees in China (Nie et al., 2020). Wolfiporia cocos was first recorded in the famous Chinese medical book “Shennong Bencao Jing” and has been used for 2000 years (Li et al., 2019a). It is a kind of traditional Chinese medicine used for both food and medicine, which can strengthen the spleen, diuretic, tranquillize the mind and dispel dampness (Ng et al., 2024). Existing studies have shown that the active metabolites of Wolfiporia cocos are mainly triterpenoids, polysaccharides, sterols, and others, of which the active metabolites have biological functions such as antitumour (Li et al., 2024; Yue et al., 2023), regulation of intestinal flora (Lai et al., 2023), improvement of organ function (Jiang et al., 2022; Wu et al., 2023a), immunomodulation (Zhang W. et al., 2023), anti-inflammatory (Wu et al., 2023b), antioxidation (Fang et al., 2021), and regulation of glycolipid metabolism (Pan et al., 2023). By applying Poria cocos, Poria, Wolfirporia cocos, Wolfiporia cocos (F.A. Wolf) Ryvarden & Gilb as search terms, we searched all the relevant studies on Wolfiporia cocos from Web of Science and PubMed databases and classified these categories of chemical and active metabolites according to the main research content of each literature and summarized its mechanism of action, updated its latest research results, and discussed the direction of further research in the future to provide a better reference for future clinical applications with better therapeutic effects and potential medicinal value.

2 Active ingredients in Wolfiporia cocos

2.1 Polysaccharides

Polysaccharides refer to a class of high molecular weight metabolites, which are composed of more than 10 monosaccharides and are connected by glycosidic bonds. Wolfiporia cocos polysaccharides, as one of the main active ingredients of Wolfiporia cocos, account for about 84% of the active ingredients in Wolfiporia cocos sclerotia (Li et al., 2019b). Wolfiporia cocos polysaccharides can be divided into two categories based on their structure: glucans and heteropolysaccharides, with heteropolysac-charides mainly consisting of glucose, galactose, and mannose (Huang Q. et al., 2007). Chihara et al. (1970) extracted Pachyman from Wolfiporia cocos, which is mainly composed of β-(1→3)-D-glucan and also contains a small amount of β-(1→6) glycosidic side chains. Narui et al. (Narui et al., 1980) demonstrated through experiments that the structure of Pachyman extracted from Wolfiporia cocos mycelium cultured in the laboratory is almost identical to that extracted from Wolfiporia cocos grown in nature. The research results of Wang et al. (Wang et al., 2004) urther confirmed that the main component of Wolfiporia cocos polysaccharides is β-(1→3)-D-glucan. According to their solubility, Wolfiporia cocos polysaccharides are divided into water soluble polysaccharides (WPCP) whose backbone is composed of (1,6)-α-galactan and (1,3)-β-mannoglucan and alkaline soluble polysaccharides (APCP) whose backbone is composed of (1,3)-β-D-glucan (Zhao et al., 2023). Details are provided in Table 1.

TABLE 1

| Components | Monosaccharide composition | Structural features | Pharmacological mechanism | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H11 | Glu | (1,3) -(1,6)-β-D-glucan | Antitumour | Kanayama et al. (1983) |

| PCS1 | Fuc: Man: Gal: Glc = 9.2: 25.7: 47.9: 17.1 | (1→3)-D-Glc-(1→6)-D-Glc; (1→6)-D-Gal, (1→4, 6)-D-Gal, (1→2, 6)-D-Man, (1→3,6)-D-Man | Not available | Wang et al. (2004) |

| PCS2 | Fuc: Man: Gal: Glc = 1.5: 8.8: 6.5: 82.4 | (1→3)-D-Glu, (1, terminal)-D-Glu, (1→6)-D-Glu, (1→2)-D-Gal, (1→3,6)-D-Man | Not available | Wang et al. (2004) |

| PCS3-I | Fuc: Xyl: Man: Gal: Glc = 9.0: 4.0: 39.3: 10.4: 37.2 | Not available | Not available | Wang et al. (2004) |

| PCS3-II | Glc = 98.4 | (1→3)-β-D-glucan with a linear | Not available | Wang et al. (2004) |

| PCS4-I | Fuc: Man: Glc = 1.2: 2.9: 93.1 | (1→3)-β-D-glucan with some β-(1→6) and (1→2) linked branches | Not available | Wang et al. (2004) |

| PCS4-II | Glc = 97.2 | (1→3)-β-D-glucan with some β-(1→6) and (1→2) linked branches | Not available | Wang et al. (2004) |

| wc-PCM0 | Fuc: Ara: Xyl: Man: Gal: Glc = 4.1: 3: 2.5: 61.7 | Not available | Antitumour | Jin et al. (2003a) |

| wc-PCM1 | Fuc: Man: Gal: Glc = 10.5:24.5: 37.5: 30.6 | Not available | Antitumour | Jin et al. (2003a) |

| wc-PCM2 | Fuc: Man: Gal: Glc = 3.4: 12.5: 13.4: 70.7 | Not available | Antitumour | Jin et al. (2003a) |

| wb-PCM0 | Xyl: Glu: Ara:Man: Gal: Glc = 3.9: 71.1: 71.1: 6.1: 3.9: 11.4 | (1,3)-α-D-glucan, β-D-mannose, β-D-galactose | Antitumour | Jin et al. (2003a) |

| wb-PCM1 | Man: Glu: Gal = 7.7: 73.1: 19.2 | Not available | Antitumour | Jin et al. (2003a) |

| wb-PCM3-I | Fuc: Ara: Man: Gal: Glc = 1.0: 2.2: 95.6: 20.5 | (1→3)-α-D-glucan | Not available | Jin et al. (2003b) |

| wb-PCM3-II | Fuc: Ara: Xyl: Man: Gal: Glc = 2.6: 2.0: 1.2: 2.0: 91.4 | (1→3)-β-D-glucan | Not available | Jin et al. (2003b) |

| wb-PCM4-I | Man: Glu = 5.8: 94.1 | Not available | Not available | Jin et al. (2003b) |

| wb-PCM4-II | Glu: Gal = 76.1: 23.9 | (1→3)-β-D-glucan | Not available | Jin et al. (2003b) |

| wc-PCM0 | Fuc: Ara: Xyl: Man: Gal: Glc = 4.1: 3: 2.5: 61.7: 15 | Not available | Not available | Jin et al. (2003b) |

| wc-PCM1 | Fuc: Xyl: Man: Gal: Glc = 10.5: 24.5: 37.5: 30.6 | Not available | Not available | Jin et al. (2003b) |

| wc-PCM2 | Fuc: Xyl: Man: Gal: Glc = 3.4: 12.5: 13.4: 70.7 | Not available | Not available | Jin et al. (2003b) |

| wc-PCM3-I | Xyl: Man: Glu = 6.4: 16.7: 76.9 | Protein-bound (1→3)-β-D-glucan | Not available | Jin et al. (2003b) |

| wc-PCM3-II | Glu | Not available | Not available | Jin et al. (2003b) |

| wc-PCM4-I | Not available | Not available | Not available | Jin et al. (2003b) |

| wc-PCM4-II | Not available | Not available | Not available | Jin et al. (2003b) |

| ac-PCM0 | Xyl: Man: Glc = 1.4: 1: 43 | Not available | Antitumour | Jin et al. (2003a) |

| ac-PCM1 | Fuc: Man: Gal: Glc = 4.5: 15.8: 23.9: 53.4 | Not available | Antitumour | Jin et al. (2003a) |

| ac-PCM2 | Fuc: Man: Gal: Glc = 0.8: 19.1: 29.7: 51.4 | Not available | Antitumour | Jin et al. (2003a) |

| ab-PCM0 | Man: Gal: Glc = 9.2: 11.1: 21.5 | Not available | Antitumour | Jin et al. (2003a) |

| ab-PCM1 | Fuc: Ara: Xyl: Man: Gal: Glc = 7.9: 4.0: 2.6: 10.5: 27.6: 47.3 | Not available | Antitumour | Jin et al. (2003a) |

| ab-PCM2 - II | Man: Gal: Glc = 5.6: 13.1: 81.2 | Not available | Antitumour | Jin et al. (2003a) |

| PCSC | Man: Gal: Ara = 92: 6.2: 1.3 | Not available | Immunomodulation | Lee and Jeon (2003) |

| PCM3 - II | Glu | Not available | Antitumour | Zhang et al. (2006) |

| Pi-PCM0 | Ara: Xyl: Man: Gal: Glc = 2.5: 1.5: 70.6: 18.5: 7 | Not available | Antitumour | Huang et al. (2007b) |

| Pi-PCM1 | Fuc: Ara: Xyl: Man: Gal: Glc = 10.9: 1.0: 2.8: 23.6: 36.5: 25.2 | Not available | Antitumour | Huang et al. (2007b) |

| Pi-PCM2 | Fuc: Man: Gal: Glc = 1.9: 29.6: 38.9: 29.7 | Not available | Antitumour | Huang et al. (2007b) |

| Pi-PCM3-I | Glu | Not available | Not available | Huang et al. (2007b) |

| Pi-PCM3-II | Man: Gal: Glc = 10.9: 21.0: 68.1 | Not available | Not available | Huang et al. (2007b) |

| Pi-PCM4-I | Glu | (1→3)-β-D-glucan | Not available | Huang et al. (2007b) |

| Pi-PCM4-II | Gal: Glc = 45.6: 54.4 | (1→3)-β-D-glucan | Not available | Huang et al. (2007b) |

| PCP-I | Fuc: Man: Glc: Gal = 1: 1.81: 0.27: 7.27 | Not available | Immunomodulation | Wu et al. (2016) |

| PCP-II | Fuc: Man: Glc: Gal = 1: 1.63: 0.16: 6.29 | Not available | Immunomodulation | Wu et al. (2016) |

| PCWPW | Fuc: Man: Glc: Gal = 15.3: 36.8: 7.2: 40.4 | Not available | Antidepressant/Immunomodulation | Zhang et al. (2023a) |

| PCWPS | Fuc: Man: Glc: Gal = 10.1: 30.07: 16.6: 41.47 | Not available | Antidepressant/Immunomodulation | Zhang et al. (2023a) |

| CMP33 | Glu | Not available | Antitumour | Liu et al. (2019) |

| CMP-1 | Glu | (1→3)-β-D-glucan | Immunomodulation | Liu et al. (2021) |

| CMP-2 | Man: Glc = 0.03:1 | Not available | Immunomodulation | Liu et al. (2021) |

| PCP-1C | Fuc: Man: Gal: Glc = 14.6: 17.4: 43.5: 24.4 | Not available | Anti-inflammatory | Cheng et al. (2021) |

| EPS - 0M | Glc: Man: Gal: Fuc: Rha = 17.3:46.3:19.9:8.7:5.0 | Not available | Anti-inflammatory/Immunomodulation | Li et al. (2023) |

| EPS - 0.1M | Glc: Man: Gal: Fuc: Rha = 11.5:46.5:21.9:10.7:5.6 | Not available | Anti-inflammatory/Immunomodulation | Li et al. (2023) |

| IPS - 0M | Glc: Man: Gal: Fuc: Rha = 79.7:8.9:5.5:1.7:3.1 | Not available | Anti-inflammatory | Li et al. (2023) |

| IPS - 0.1M | Glc: Man: Gal: Fuc: Rha = 50.3:20.9:16.1:6.0:4.0 | Not available | Anti-inflammatory/Immunomodulation | Li et al. (2023) |

Polysaccharides from Wolfiporia cocos.

2.2 Triterpenoids

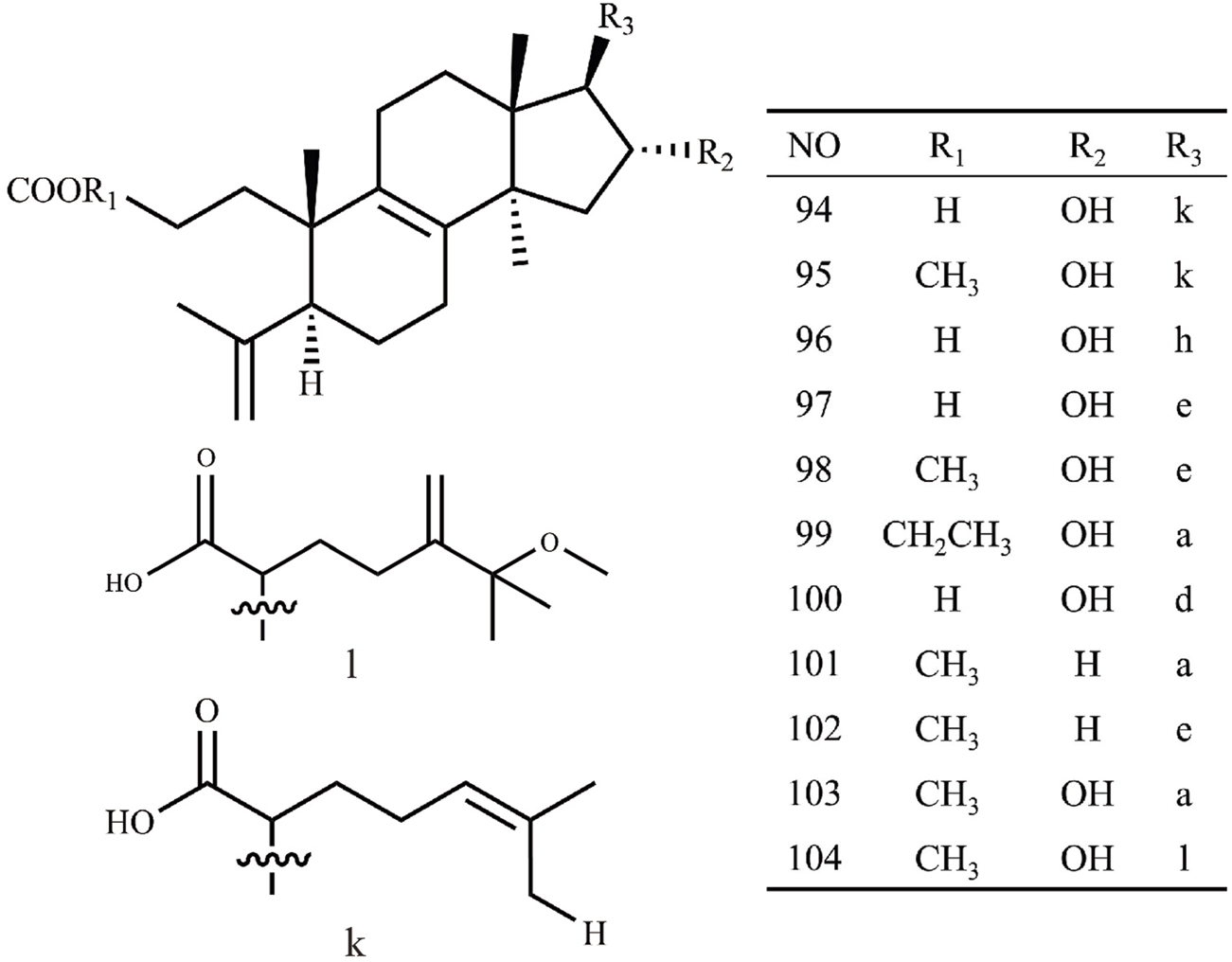

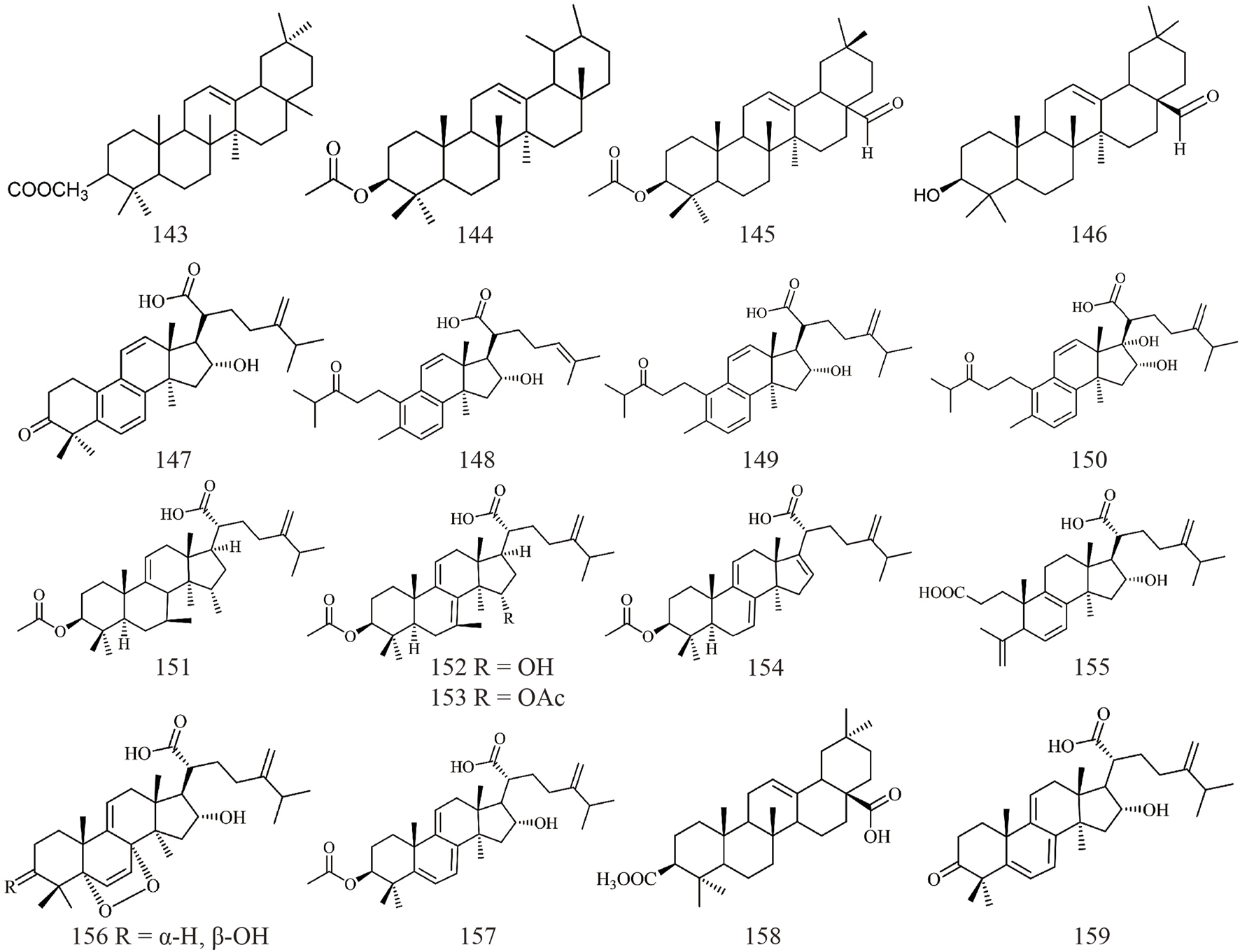

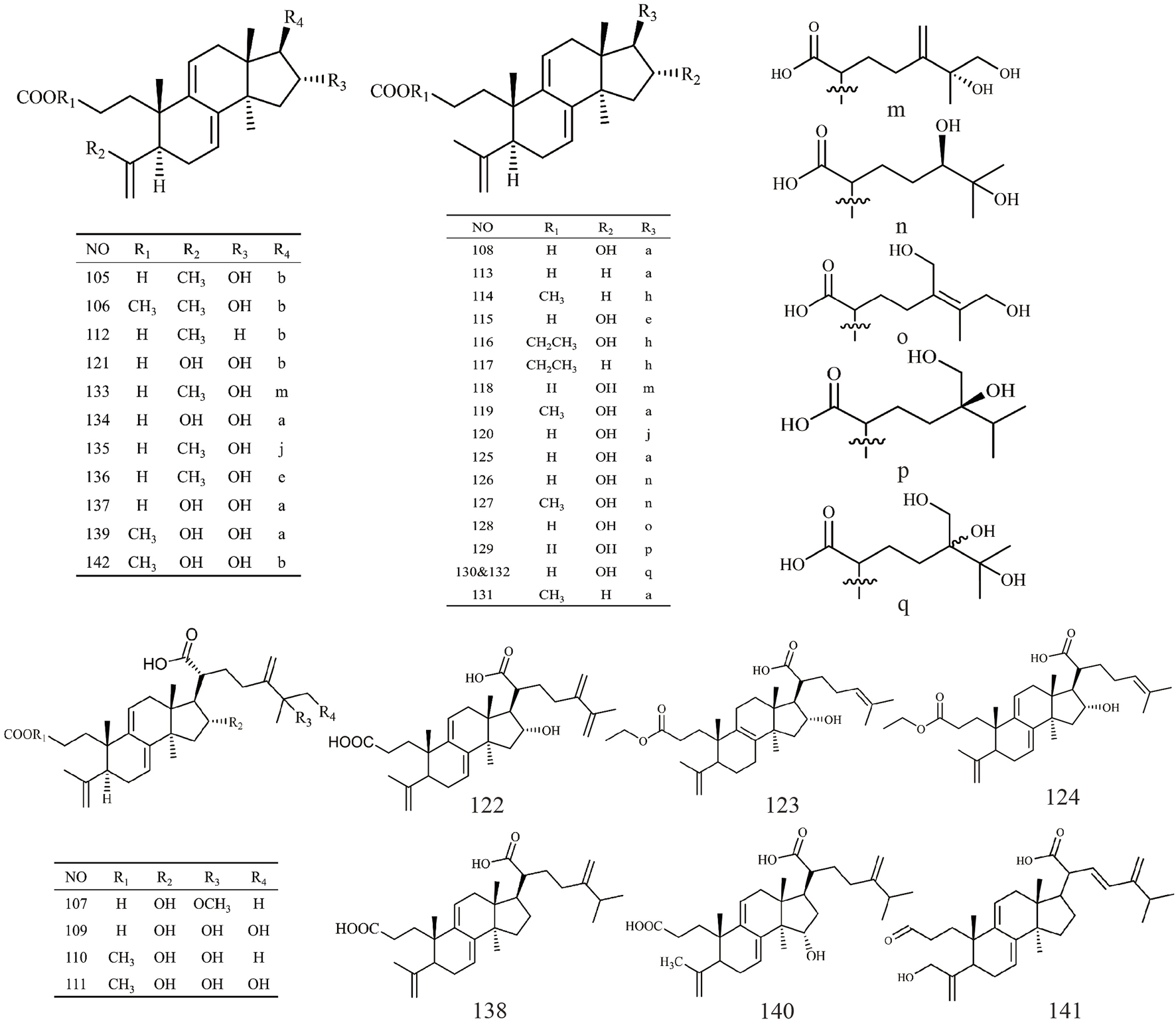

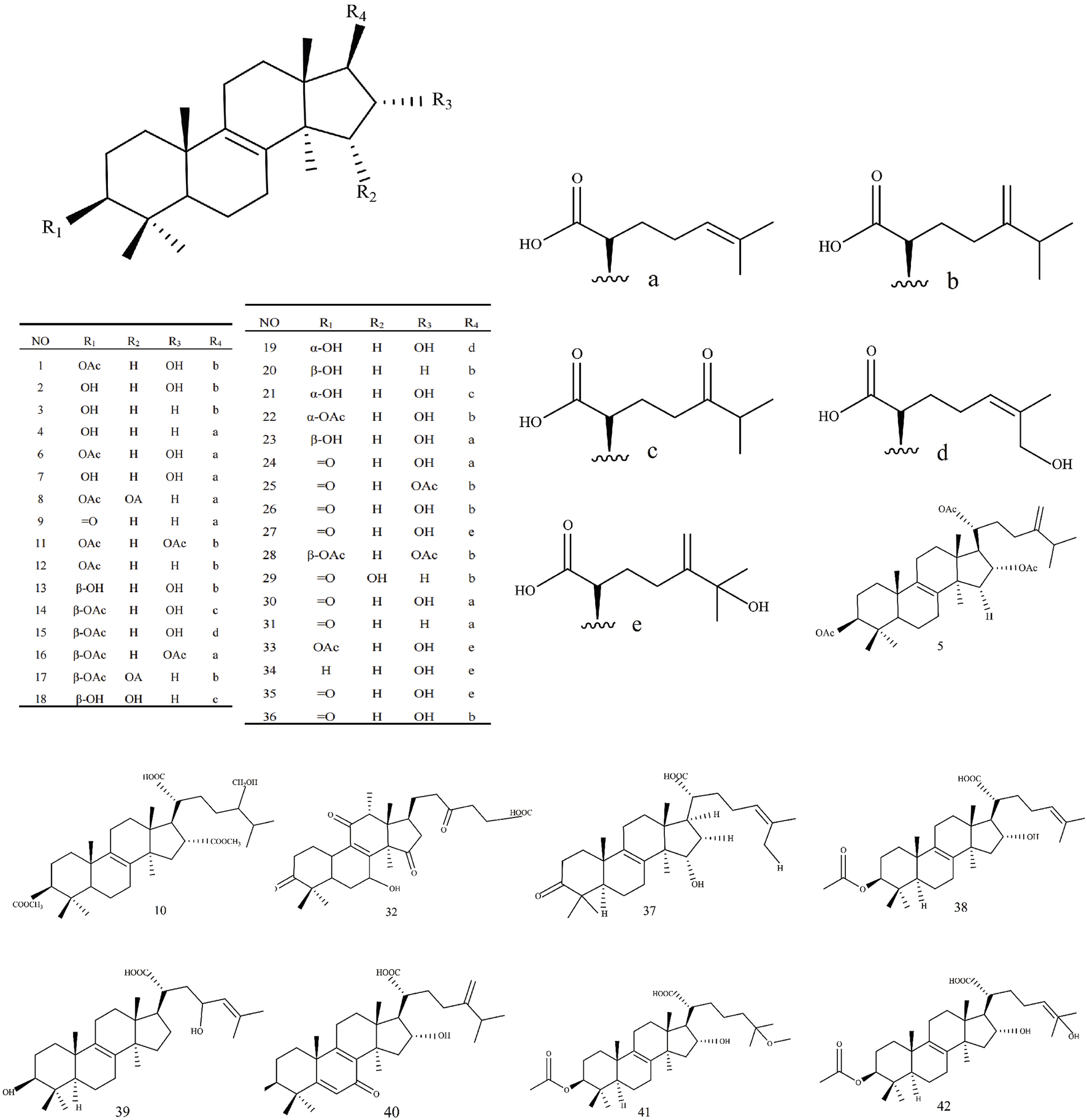

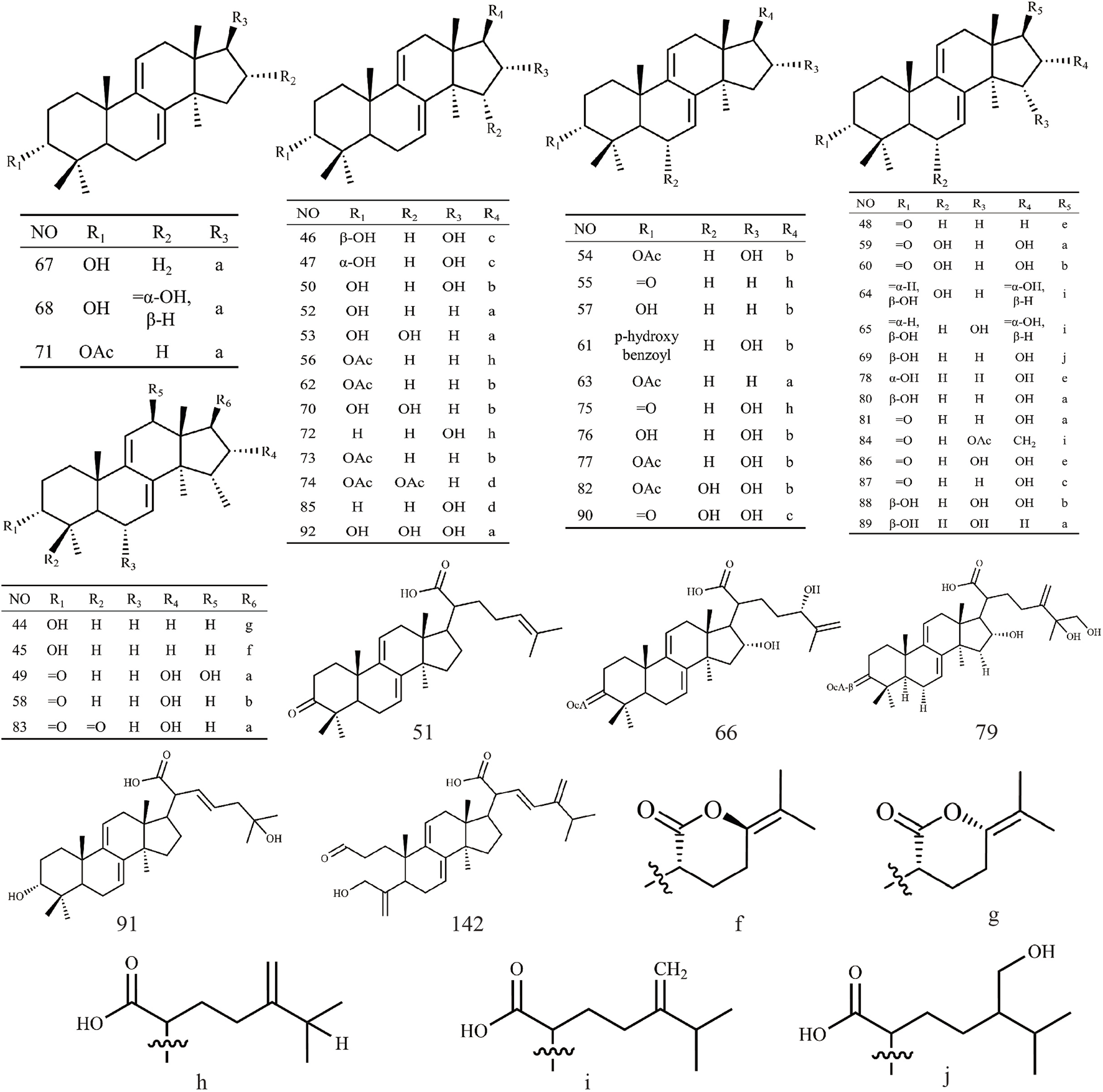

Triterpenoids, as one of the main active ingredients of Wolfiporia cocos, have a basic parent nucleus composed of 30 carbon atoms, and their structure can be regarded as a polymer of six isoprene units (Chen et al., 2018a). So far, more than 100 triterpenes with different skeletons have been discovered, among which pentacyclic triterpenes and tetracyclic triterpenes have the highest content (Andre et al., 2016). The triterpenoids in Wolfiporia cocos are mainly divided into two categories based on their number of rings: tetracyclic triterpenoids and pentacyclic triterpenoids, with tetracyclic triterpenoids dominating. We classified 159 triterpenoids obtained from the literature based on their different molecular backbone characteristics and grouped triterpenoids with similar molecular backbones. Details are provided in Table 2 and Figures 1–5.

TABLE 2

| No | Chemical components | Formula | Molecular mass | Pharmacological properties | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lanosta-8-ene type triterpenes | |||||

| 1 | Pachymic acid | C33H52O5 | 527.37 | Regulation of glycolipid metabolism, anti-inflammatory, antioxidation, inhibition of LDH and α-glucosidase activity | Li et al. (2017) |

| 2 | Tumulosic acid | C31H50O4 | 485.36 | Anti-inflammatory | Fu et al. (2018) |

| 3 | Eburicoic acid | C31H50O3 | 470.72 | Regulation of glycolipid metabolism, antioxidation, inhibition of LDH activity | Li et al. (2017) |

| 4 | Trametenolic acid | C30H48O3 | 456.7 | Antioxidation, inhibition of LDH activity | Li et al. (2017) |

| 5 | Methyl pachymate | C34H56O6 | 560.8 | Not available | Wang et al. (1993) |

| 6 | 3-O-acetyl-16α-hydroxytrametenolic acid | C32H50O5 | 513.35 | Inhibition α-glucosidase activity | Ma et al. (2023) |

| 7 | 16α-hydroxytrametenolic acid | C30H48O4 | 471.34 | Anti-inflammatory | Nukaya et al. (1996) |

| 8 | Versisponic acid E | C35H54O5 | 554.8 | Regulation of glycolipid metabolism | Chen et al. (2019) |

| 9 | Oxotrametenolic acid | C30H46O4 | 470.68 | Not available | Lee et al. (2017a) |

| 10 | O-acetylpachymic acid-25-ol | C35H56O7 | 588.81 | Not available | Wang and Wan (1998) |

| 11 | O-acetylpachymic acid | C35H54O6 | 570.8 | Not available | Wang et al. (1993) |

| 12 | Acetyl eburicoic acid | C33H52O4 | 512.76 | Antitumour | León et al. (2004) |

| 13 | 3β,16α-dihydroxy-7-oxo-24-methyllanosta-8,24(31)-dien-21-oic acid | C31H48O5 | 523.34 | Not available | Lai et al. (2016) |

| 14 | 3β-acetyloxy-16α-hydroxy-24-oxolanost-8-en-21-oic acid | C32H50O6 | 529.35 | Not available | Zou (2019) |

| 15 | 3β-acetyloxy-16α,26-dihydroxylanosta-8,24-dien-21-oic acid | C32H50O6 | 529.35 | Not available | Zou (2019) |

| 16 | 3β,16α-bis(acetyloxy)-29-hydroxylanosta-8,24-dien-21-oic acid | C34H52O7 | 571.36 | Not available | Zou (2019) |

| 17 | 3β,16α-bis(acetyloxy)-24-methylenelanost-8-en-21-oic acid | C35H54O6 | 569.38 | Not available | Zou (2019) |

| 18 | 3β,15α-dihydroxy-24-oxolanosta-8-en-21-oic acid | C30H48O5 | 487.34 | Not available | Zou (2019) |

| 19 | 3α,16α,25-trihydroxylanosta-8,24-dien-21-oic acid | C30H48O5 | 487.34 | Not available | Zou (2019) |

| 20 | Hispindic acid B | C31H50O4 | 485.36 | Not available | Zou (2019) |

| 21 | Daedaleanic acid B | C30H48O5 | 487.34 | Not available | Zou (2019) |

| 22 | 3-epi-pachymic acid | C33H52O5 | 527.37 | Not available | Zou (2019) |

| 23 | 16α-hydroxyeburiconic acid | C31H48O4 | 483.35 | Not available | Zou (2019) |

| 24 | 16α-hydroxy-3-oxolanosta-8,24-dien-21-oic acid | C30H46O4 | 469.33 | Not available | Zou (2019) |

| 25 | 16α-acetyloxyeburiconic acid | C33H50O5 | 525.35 | Not available | Zou (2019) |

| 26 | 16α,29-dihydroxyeburiconic acid | C31H48O5 | 499.34 | Not available | Zou (2019) |

| 27 | 16α,25-dihydroxydehydroeburiconic acid | C31H48O5 | 499.34 | Not available | Zou (2019) |

| 28 | 16-O-acetylpachymic acid | C35H54O6 | 569.38 | Not available | Zou (2019) |

| 29 | 15α-hydroxyeburiconic acid | C31H48O4 | 483.34 | Not available | Zou (2019) |

| 30 | Pinicolic acid E | C30H46O4 | 470.68 | Regulation of glycolipid metabolism | Chen et al. (2019) |

| 31 | Pinicolic acid A | C30H46O3 | 454.68 | Stimulating glucose uptake and improving insulin sensitivity, antibacterial | Chen et al. (2019) |

| 32 | Ganoderic acid | C30H44O7 | 516.66 | Not available | Wang and Wan (1998) |

| 33 | 25-hydroxypachymic acid | C33H52O6 | 544.76 | Not available | Zheng and Yang (2008) |

| 34 | 25-hydroxy-3-epitumulosic acid | C31H49O5 | 501.72 | Inhibition of TPA-induced EBV-EA, cytotoxicity to HL60 | Akihisa et al. (2009) |

| 35 | 16α,25-dihydroxyeburicoic acid | C31H47O5 | 499.7 | Inhibition of TPA-induced EBV-EA, cytotoxicity to CRL1579 | Akihisa et al. (2009) |

| 36 | 16α-hydroxyeburicoic acid | C20H28O4 | 332.43 | Not available | Akihisa et al. (2009) |

| 37 | 15α-hydroxy-3-oxolanosta-8,24-dien-21-oic acid | C30H46O4 | 469.33 | Not available | Zou et al. (2019) |

| 38 | 3β-ethanoyl-16α,23-dihydroxy-lanosta-8(9),24(25)-diene-21-oic acid | C32H50O6 | 553.35 | Not available | Wang (2019) |

| 39 | 3β,23-dihydroxy-lanosta-8(9),24(25)-diene-21-oic acid | C30H49O4 | 473.36 | Not available | Wang (2019) |

| 40 | 3α,16α-dihydroxy-7-oxo-lanosta-5(6),8(9),24(31)-trien-21-oic acid | C31H46O5 | 521.32 | Not available | Wang (2019) |

| 41 | Ceanphytamic acid B | C33H53O6 | 545.77 | Antitumour | Chen et al. (2018a) |

| 42 | Ceanphytamic acid A | C32H49O6 | 529.73 | Antitumour | Chen et al. (2018a) |

| 43 | 3-O-formyleburicoic acid | Not available | Not available | Not available | Hui et al. (2016) |

| Lanosta-7,9(11)-diene type triterpenes | |||||

| 44 | Porilactone B | C30H45O3 | 453.34 | Stimulating glucose uptake and improving insulin sensitivity | Chen et al. (2019) |

| 45 | Porilactone A | C30H45O3 | 453.33 | Stimulating glucose uptake and improving insulin sensitivity | Chen et al. (2019) |

| 46 | Poriacosones B | C30H46O5 | 485.32 | Not available | Zheng and Yang (2008) |

| 47 | Poriacosones A | C30H46O5 | 485.32 | Not available | Zheng and Yang (2008) |

| 48 | Polyporenic acid C | C31H46O4 | 481.33 | Regulation of glycolipid metabolism, Cytotoxic to K562, anti-inflammatory, Antitumour | Zheng and Yang (2008) |

| 49 | Pinicolic acid F | C30H47O6 | 503.34 | Stimulating glucose uptake and improving insulin sensitivity | Chen et al. (2019) |

| 50 | Dehydrotumulosic acid | C31H48O4 | 483.35 | Anti-inflammatory, inhibition α-glucosidase activity | Ma et al. (2023) |

| 51 | Dehydrotrametenonic acid | C30H44O3 | 452.67 | Not available | Akihisa et al. (2004) |

| 52 | Dehydrotrametenolic acid | C30H46O3 | 453.34 | Anti-inflammatory, antioxidation, inhibition of LDH activity | Akihisa et al. (2004) |

| 53 | Dehydrosulphurenic acid | C33H50O6 | 542.74 | Anti-inflammatory | Dong et al. (2015) |

| 54 | Dehydropachymic acid | C33H50O5 | 526.75 | Stimulating glucose uptake and improving insulin sensitivity, anti-inflammatory, antioxidation, inhibition of LDH activity, Antitumour | Li et al. (2017) |

| 55 | Dehydroeburiconic acid | C33H50O5 | 526.75 | Antitumour | Tai et al. (1995) |

| 56 | Dehydroeburicoic acid monoacetate | C33H50O4 | 510.75 | Antitumour | Lai et al. (2016) |

| 57 | Dehydroeburicoic acid | C33H50O3 | 494.75 | Anti-inflammatory, Antitumour | Fu et al. (2018) |

| 58 | 6α-hydroxypolyporenic acid C | C31H46O5 | 498.69 | Not available | Wang (2019) |

| 59 | 6,16α-dihydroxydehydrotrametenonic acid | C30H44O5 | 483.31 | Not available | Zou (2019) |

| 60 | 6,16α-dihydroxydehydroeburiconic acid | C31H46O5 | 497.32 | Not available | Zou (2019) |

| 61 | 3β-p-hydroxybenzoyldehydrotumulosic acid | C38H52O6 | 603.36 | Anti-inflammatory | Yasukawa et al. (1998) |

| 62 | 3β-hydroxy-16α-acetoxy-lanosta-7,9(11),24-trien-21-oic acid | C32H48O5 | 511.34 | Not available | Zou et al. (2019) |

| 63 | 3β-acetoxylanosta-7,9(11),24-trien-21-oic acid | C32H48O4 | 496.72 | Cytotoxic to K562 | Lai et al. (2016) |

| 64 | 3β,16α,29-trihydroxy-24-methyllanosta-7,9(11),24(31)-trien-21-oic acid | C32H48O5 | 523.33 | Not available | Lai et al. (2016) |

| 65 | 3β,16α,30-trihydroxy-24-methyllanosta-7,9(11),24(31)-trien-21-oic acid | C32H48O5 | 523.33 | Not available | Lai et al. (2016) |

| 66 | 3β-acetoxy-16α,24β-dihydroxylanosta-7,9(11),25-trien-21-oic acid | C32H48O6 | 551.33 | Not available | Lai et al. (2016) |

| 67 | Lanosta-7,9(11),24-trien-21-oic acid | C31H48O2 | 452.71 | Antitumour | Lai et al. (2016) |

| 68 | 3β,16α-dihydroxylanosta-7,9(11),24-trien-21-oic acid | C30H46O4 | 470.68 | Anti-inflammatory | Akihisa et al. (2004) |

| 69 | 3β,16α-dihydroxy-24-hydroxymethyllanosta-7,9(11)-dien-21-oic acid | C31H50O5 | 501.35 | Not available | Zou (2019) |

| 70 | 3β,15α-dihydroxylanosta-7,9(11),24-triene-21-oic acid | C31H48O4 | 484.71 | Not available | Dong et al. (2015) |

| 71 | 3-O-acetyl-16α-hydroxy-dehydrotrametenolic acid | C32H48O5 | 511.34 | Not available | Tai et al. (1995) |

| 72 | 3-epidehydrotumulosic acid | C31H48O4 | 484.71 | Not available | Tai et al. (1995) |

| 73 | 3-epidehydropachymic acid | C31H48O4 | 484.71 | Inhibition α-glucosidase activity | Ma et al. (2023) |

| 74 | 3,15-O-diacetyl-dehydrotrametenolic Acid | C34H50O6 | 577.35 | Not available | Chen et al. (2019) |

| 75 | 29-hydroxypolyporenic acid C | C31H46O5 | 498.69 | Not available | Zheng and Yang (2008) |

| 76 | 29-hydroxydehydrotumulosic acid | C31H48O5 | 499.34 | Anti-inflammatory | Cai and Cai (2011) |

| 77 | 29-hydroxydehydropachymic acid | C33H50O6 | 541.35 | Anti-inflammatory | Cai and Cai (2011) |

| 78 | 25-hydroxy-3-epi-dehydrotumulosic acid | C32H50O5 | 514.73 | Not available | Tai et al. (1995) |

| 79 | 25,26-dihydroxydehydropachymic acid | C33H50O7 | 557.34 | Not available | Zou (2019) |

| 80 | 16α-hydroxydehydrotrametenolic acid | C30H46O4 | 469.33 | Not available | Zou (2019) |

| 81 | 16α-hydroxydehydrotrametenonic acid | C30H44O4 | 467.31 | Not available | Zou (2019) |

| 82 | 16α-hydroxydehydropachymic acid | C33H50O6 | 542.74 | Anti-inflammatory | Nukaya et al. (1996) |

| 83 | 16α-hydroxy-3-oxolanosta-7,9(11),24-trien-21-oic acid | C30H44O4 | 468.67 | Not available | Chen et al. (2019) |

| 84 | 16α-acetyloxy- 24-methylene-3-oxolanosta-7,9(11)-dien-21-oic acid | C33H48O5 | 523.34 | Not available | Zou et al. (2019) |

| 85 | 16α,27-dihydroxydehydrotrametenoic acid | C30H46O5 | 485.33 | Inhibition of TPA-induced EBV-EA | Akihisa et al. (2009) |

| 86 | 16α,25-dihydroxydehydroeburiconic acid | C31H46O5 | 497.33 | Not available | Zou (2019) |

| 87 | 16-hydroxy-3,24-dioxolanosta-7,9(11)-dien-21-oic acid | C30H44O5 | 483.31 | Not available | Zou (2019) |

| 88 | 15α-hydroxydehydrotumulosic acid | C31H48O5 | 499.34 | Inhibition of TPA-induced EBV-EA | Akihisa et al. (2007) |

| 89 | 15α-hydroxydehydrotrametenolic acid | C30H46O4 | 469.33 | Not available | Zou (2019) |

| 90 | Poricoic acid ZI | C30H43O6 | 499.31 | Not available | Wang (2019) |

| 91 | Poricoic acid ZE | C30H46O4 | 493.33 | Anti-renal fibrosis | Wang (2019) |

| 92 | Poricoic acid ZL | C30H47O5 | 487.34 | Not available | Wang (2019) |

| 93 | 3-O-formyl-dehydrotrametenolic acid | Not available | Not available | Not available | Hui et al. (2016) |

| 3,4-seco-lanostan-8-ene type triterpenes | |||||

| 94 | Poricoic acid G | C30H46O5 | 485.33 | Cytotoxicity to HL60 | Mizushina et al. (2004) |

| 95 | Poricoic acid GM | C31H47O5 | 499.7 | Inhibition of TPA-induced EBV-EA | Akihisa et al. (2009) |

| 96 | Poricoic acid H | C31H48O5 | 499.34 | Cytotoxicity to HL60 | Mizushina et al. (2004) |

| 97 | Poricoic acid HM | C32H49O5 | 513.73 | Inhibition of TPA-induced EBV-EA | Akihisa et al. (2009) |

| 98 | 25-hydroxyporicoic acid H | C30H48O6 | 504.7 | Not available | Akihisa et al. (2007) |

| 99 | Poricoic acid GE | C30H46O5 | 486.68 | Not available | Dong et al. (2015) |

| 100 | Poricoic acid ZA | C30H46O6 | 502.68 | Anti-renal fibrosis | Wang et al. (2017) |

| 101 | Poricoic acid ZJ | C31H48O5 | 523.34 | Not available | Wang (2019) |

| 102 | Poricoic acid ZK | C31H47O4 | 483.34 | Not available | Wang (2019) |

| 103 | Poricoic acid ZR | C31H48O6 | 539.33 | Not available | Wang (2019) |

| 104 | 25-methoxy-29-hydroxyporicoic acid HM | C33H52O7 | 559.36 | Not available | Zou (2019) |

| 3,4-seco-lanostan-7,9(11)-diene type triterpenes | |||||

| 105 | Poricoic acid A | C31H46O5 | 497.32 | Antitumour, inhibition α-glucosidase and activity | Ma et al. (2023) |

| 106 | Poricoic acid AM | C32H48O5 | 512.72 | Inhibition of TPA-induced EBV-EA | Tai et al. (1993) |

| 107 | 25-methoxyporicoic acid A | C32H48O6 | 527.33 | Inhibition of TPA-induced EBV-EA, Antitumour | Akihisa et al. (2009) |

| 108 | Poricoic acid B | C30H44O5 | 483.31 | Antitumour, inhibition α-glucosidase activity | Ma et al. (2023) |

| 109 | 25-hydroxyporicoic acid C | C31H45O5 | 497.68 | Inhibition of TPA-induced EBV-EA, cytotoxicity to HL60 | Akihisa et al. (2009) |

| 110 | Poricoic acid DM | C32H48O6 | 527.33 | Inhibition of TPA-induced EBV-EA | Tai et al. (1993) |

| 111 | 26-hydroxyporicoic acid DM | C32H48O7 | 544.72 | Inhibition of TPA-induced EBV-EA | Akihisa et al. (2009) |

| 112 | Poricoic acid C | C31H46O4 | 481.33 | Inhibition α-glucosidase activity | Ma et al. (2023) |

| 113 | 16-deoxyporicoic acid B | C30H44O4 | 467.32 | Antitumour | Akihisa et al. (2007) |

| 114 | Poricoic acid CM | C32H48O4 | 496.72 | Inhibition of TPA-induced EBV-EA | Akihisa et al. (2007) |

| 115 | Poricoic acid D | C31H46O6 | 513.32 | Stimulating glucose uptake and improving insulin sensitivity | Tai et al. (1993) |

| 116 | Poricoic acid AE | C33H50O5 | 526.75 | Not available | Yang et al. (2009) |

| 117 | Poricoic acid CE | C33H50O4 | 510.75 | Not available | Yang et al. (2009) |

| 118 | Poricoic acid L | C31H46O7 | 553.31 | Stimulating glucose uptake and improving insulin sensitivity | Chen et al. (2019) |

| 119 | Poricoic acid BM | C31H46O5 | 498.69 | Not available | Tai et al. (1995) |

| 120 | Poricoic acid E | C30H44O6 | 500.67 | Not available | Tai et al. (1995) |

| 121 | Poricoic acid F | C30H47O6 | 503.34 | Not available | Chen et al. (2019) |

| 122 | 16α-hydroxy-3,4-secolanosta-4(28),7,11(9),24(31),25(27)-pentaene- 3,21-dioic acid | C31H44O5 | 495.31 | Not available | Dong et al. (2017) |

| 123 | 16α-hydroxy-3,4-seco-lanosta-4(28),8,24-triene-3,21-dioic acid-3-ethyl ester | C32H50O5 | 513.36 | Not available | Dong et al. (2017) |

| 124 | 16α-hydroxy-3,4-seco-lanosta-4(28),7(9),11,24-tetraene-3,21-dioic acid-3-ethyl ester | C32H48O5 | 511.34 | Not available | Dong et al. (2017) |

| 125 | Poricoic acid I | C31H47O6 | 515.33 | Regulation of glycolipid metabolism | Chen et al. (2019) |

| 126 | Poricoic acid J | C31H47O7 | 531.33 | Stimulating glucose uptake and improving insulin sensitivity | Chen et al. (2019) |

| 127 | Poricoic acid JM | C32H49O7 | 545.34 | Regulation of glycolipid metabolism | Chen et al. (2019) |

| 128 | Poricoic acid K | C31H47O7 | 533.34 | Regulation of glycolipid metabolism | Chen et al. (2019) |

| 129 | Poricoic acid M | C30H46O7 | 541.31 | Regulation of glycolipid metabolism | Chen et al. (2019) |

| 130 | Poricoic acid N | C31H48O8 | 571.32 | Stimulating glucose uptake and improving insulin sensitivity | Chen et al. (2019) |

| 131 | 16-deoxyporicoic acid BM | C31H47O4 | 483.35 | Not available | Chen et al. (2019) |

| 132 | Poricoic acid O | C31H48O8 | 571.32 | Stimulating glucose uptake and improving insulin sensitivity | Chen et al. (2019) |

| 133 | Poricoic acid ZB | C31H46O7 | 553.31 | Not available | Wang (2019) |

| 134 | Poricoic acid ZC | C30H44O6 | 523.3 | Anti-renal fibrosis | Wang (2019) |

| 135 | Poricoic acid ZD | C31H47O7 | 531.33 | Anti-renal fibrosis | Wang (2019) |

| 136 | Poricoic acid ZG | C30H46O6 | 525.31 | Antifibrotic | Chen et al. (2019) |

| 137 | Poricoic acid ZM | C30H46O6 | 525.31 | Not available | Wang (2019) |

| 138 | Poricoic acid ZO | C31H44O4 | 503.31 | Not available | Wang (2019) |

| 139 | Poricoic acid ZP | C31H45O6 | 513.32 | Not available | Wang (2019) |

| 140 | Poricoic acid ZN | C31H46O5 | 521.32 | Not available | Wang (2019) |

| 141 | Poricoic acid ZV | C30H46O4 | 493.33 | Not available | Wang (2019) |

| 142 | Poricoic acid ZQ | C32H48O6 | 551.33 | Not available | Wang (2019) |

| Other type triterpenes | |||||

| 143 | Β-amyrin acetate | C32H52O2 | 468.75 | Not available | Wang and Wan (1998) |

| 144 | Α-amyrin acetate | C32H52O2 | 468.75 | Not available | Yang et al. (2019) |

| 145 | Oleanolic acid 3-O-acetate | C32H50O4 | 498.73 | Not available | Yang et al. (2019) |

| 146 | Oleanolic acid | C30H48O3 | 456.7 | Not available | Dianpeng et al. (1998) |

| 147 | Daedaleanic acid F | C31H43O4 | 479.31 | Regulation of glycolipid metabolism | Chen et al. (2019) |

| 148 | Daedaleanic acid E | C30H42O4 | 489.3 | Stimulating glucose uptake and improving insulin sensitivity | Chen et al. (2019) |

| 149 | Daedaleanic acid D | C31H45O4 | 481.33 | Stimulating glucose uptake and improving insulin sensitivity | Chen et al. (2019) |

| 150 | Daedaleanic acid A | C31H46O4 | 482.69 | Stimulating glucose uptake and improving insulin sensitivity | Chen et al. (2019) |

| 151 | Coriacoic acid D | C35H52O7 | 584.78 | Not available | Lee et al. (2017b) |

| 152 | Coriacoic acid C | C35H50O5 | 550.77 | Not available | Lee et al. (2017b) |

| 153 | Coriacoic acid B | C35H52O6 | 568.78 | Not available | Lee et al. (2017b) |

| 154 | Coriacoic acid A | C33H48O4 | 508.73 | Not available | Lee et al. (2017b) |

| 155 | 6,7-dehydroporicoic acid H | C31H45O5 | 497.68 | Inhibition of TPA-induced EBV-EA | Akihisa et al. (2009) |

| 156 | 5α,8α-peroxydehydrotumulosic acid | C31H46O6 | 513.32 | Not available | Akihisa et al. (2007) |

| 157 | 3β-acetyloxy-16α-hydroxy-24-methy-lenelanosta-5,7(9),11-tetraene-21-oic acid | C33H48O5 | 523.34 | Not available | Dong et al. (2017) |

| 158 | 3-acetoxy oleanolic acid | C32H52O4 | 500.75 | Not available | Yang et al. (2014) |

| 159 | 16α-hydroxy-3-oxo-24-methyllanosta-5,7,9(11),24(31)-tetraen-21-oic acid | C31H44O4 | 503.31 | Not available | Lai et al. (2016) |

Triterpenoids from Wolfiporia cocos.

FIGURE 1

Structures of Lanosta-8-ene type triterpenes in Wolfiporia cocos.

FIGURE 2

Structures of Lanosta-7,9(11)-diene type triterpenes in Wolfiporia cocos.

FIGURE 3

Structures of 3,4-seco-lanostan-8-ene type triterpenes in Wolfiporia cocos.

FIGURE 4

Structures of 3,4-seco-lanostan-7,9(11)-diene type triterpenes in Wolfiporia cocos.

FIGURE 5

Structures of other type triterpenes in Wolfiporia cocos.

2.3 Sterols

Sterol metabolites are a class of steroids, all of which have cyclopentane dihydrophenanthrene as their basic structure and are steroids containing hydroxyl groups (Yalcinkaya et al., 2024). Sterol metabolites mainly contain ergosterol and pregnancy sterols (Chen et al., 2018b). The representative metabolites of ergosterols mainly include ergosta-7.22-dien-3β-ol,ce-revisterol,ergosta-7-en-3β-ol (Jinming et al., 2001), β-sitosterol (Tong et al., 2010) and stigmas-terol (Ni et al., 2019). Representative metabolites of pregnancy sterols include pregn-7-ene-2β,3a,15a,20-tetrol and pregna-7-en-3a,11a,15a,20-quad-roil (Chen et al., 2018b). Details are provided in Table 3.

TABLE 3

| Chemical components | Formula | Molecular mass | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ergosterol | C28H44O | 396.65 | Yaoita et al. (2002) |

| (22E) -ergosta-5, 7, 9(11),22-tetraen-3β-ol | C28H44O | 396.65 | Yaoita et al. (2002) |

| Ergosta-5, 7-dien-3β-ol | C28H44O | 396.65 | Yaoita et al. (2002) |

| (22E) -ergosta-8(14),22-dien-3β-ol | C28H46O | 398.66 | Yaoita et al. (2002) |

| (22E) -ergosta-6, 8(14),22-trien-3β-ol | C28H44O | 396.65 | Yaoita et al. (2002) |

| (22E) -ergosta-7, 22-dien-3β-ol | C28H46O | 398.66 | Yaoita et al. (2002) |

| Ergost-7-en-3β-ol | C28H48O | 400.68 | Yaoita et al. (2002) |

| Ergosterol peroxide | C28H44O3 | 428.65 | Li et al. (2004) |

| Pregn-7-ene-2β, 3α, 15α, 20-tetrol | C21H34O4 | 350.49 | Chen et al. (2018b) |

| 3β,5α-dihydroxy-ergosta-7,22-dien-6-one | C28H46O3 | 430.66 | Yang et al. (2014) |

| 3β,5α,9α-trihydroxy-ergosta-7,22-diene-6one | C28H46O4 | 446.66 | Yang et al. (2014) |

| Ergosta-7,22-diene-3-one | C28H44O | 396.65 | Yang et al. (2014) |

| 6,9-epoxy-ergosta-7,22-diene-3-ol | C28H46O2 | 414.66 | Yang et al. (2014) |

| Ergosta-4,22-diene-3one | C28H46O | 398.66 | Yang et al. (2014) |

| Ergosta-5,6-epoxy-7,22-dien-3-ol | C28H46O2 | 414.66 | Yang et al. (2014) |

| Preg-7-ene-2β,3α,15α,20-tetrol | C21H31O4 | 347.47 | Tong et al. (2010) |

| Β-sitosterol | C31H52O2 | 456.74 | Tong et al. (2010) |

| 9,11 - dehydroergosterol peroxide | C28H44O3 | 428.65 | Lee et al. (2018) |

Sterols from Wolfiporia cocos.

2.4 Other ingredients

In addition to polysaccharides, triterpenoids, and sterols, there are also some other types of chemical metabolites in Wolfiporia cocos. Such as tricyclic diterpenes (Shen et al., 2012) and sohiracillinone (Chen et al., 2018a). Organic acids and their esters include protocatechuic acid, palmitic acid, ethyl palmitate, methyl palmitate, trimethyl citrate, dimethyl(R)-malate, di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate, dibutyl phthalate, octadecanoic acid, octacosyl acid and pentacosanoic acid (Yang et al., 2019). In addition, 51 proteins were isolated and identified from the fermentation broth of Wolfiporia cocos. Some studies have found that volatile oil metabolites from Wolfiporia cocos (Jie et al., 2014) contain abundant trace elements required by the human body, such as iron, zinc, manganese, potassium, sodium, selenium, calcium and phosphorus. Among them, iron has the highest content, followed by zinc and manganese (Xi and Zhang, 2022).

3 Pharmacological mechanism of active ingredients in Wolfiporia cocos

3.1 Antitumour activity

A large number of studies have found that the anticancer effect of the active ingredients in Wolfiporia cocos on lung cancer (Jiang and Duanmu, 2021), breast cancer (Jeong et al., 2015), gastric cancer (Lu et al., 2018), liver cancer (Huang et al., 2006), pancreatic cancer (Cheng et al., 2013), and kidney cancer (Li et al., 2024) may inhibit tumor cell proliferation and metastasis and induce tumor cell apoptosis by regulating some signal pathways and the expression level of tumor-related cytokines.

Recent pharmacological studies have uncovered the antitumor mechanisms associated with bioactive components derived from Wolfiporia cocos. Pachymic acid (PA) has been shown to disrupt tumor cell architecture and induce apoptosis in renal tumor cells via upregulation of tumor protein p53-inducible nuclear protein 2 (TP53INP2) and tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6), alongside activation of pro-apoptotic pathways involving caspase-8, caspase-3, and PARP (Li et al., 2024). Chen et al. (2015) demonstrated that PA inhibits migration and invasion of gallbladder cancer cells in a dose-dependent manner by downregulating tumor-associated proteins including PCNA, ICAM-1, RhoA, p-Akt, and p-ERK1/2, mediated through inhibition of the AKT and ERK pathways. Ling et al. (2011) showed that PA suppresses invasion and metastasis of MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 breast cancer cells by inhibiting the NF-κB signaling pathway and MMP-9 activity. Wang et al. (2022) demonstrated that PA inhibits gastric cancer (GC) cell viability and proliferation in a concentration-dependent manner. This reduction in GC cell adhesion effectively hampers metastasis and invasion. PA also significantly alters the expression of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT)-related proteins, including E-cadherin, N-cadherin, and Vimentin, while concurrently decreasing the levels of metastasis-related proteins, including matrix metalloproteinases MMP-2 and MMP-9, along with tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinase 1.

Chen et al. (2022) demonstrated that poricoic acid A (PAA) exhibits significant therapeutic effects on T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL). Both in vitro and in vivo models showed that PAA markedly reduced T-ALL cell viability, induced G2 phase cell cycle arrest, and triggered apoptosis by exacerbating mitochondrial dysfunction and generating excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS). Additionally, PAA was found to induce autophagy and ferroptosis in T-ALL cells by regulating the AMPK/mTOR and LC3 signaling pathways, thus amplifying its therapeutic effects. Ma et al. (2021a) reported that PAA triggers apoptosis in SKOV3 ovarian cancer cells through mitochondrial and death receptor pathways in a concentration-dependent manner. Its antitumor mechanisms involve inhibition of the mTOR/p70S6K signaling pathway, an increase in LC3-I and LC3-II protein levels, activation of caspase-3, caspase-8, and caspase-9, and modulation of pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic protein expression.

Jiang et al. (2022) discovered that Wolfiporia cocos polysaccharides can dose-dependently inhibit the proliferation of lung cancer cells and suppress the migration and invasion of A549 cells by downregulating MMP-2 and MMP-9 through inhibition of the NF-κB signaling pathway. Moreover, neutral polysaccharide metabolites (Chen and Chang, 2004) and triterpenoids (Ukiya et al., 2002) isolated from Wolfiporia cocos have been reported to inhibit the proliferation and differentiation of HL-60 human leukemia cells. Lin et al. (Lin et al., 2020) discovered that the fucose-containing mannoglucan polysaccharide (FMGP) extracted from Wolfiporia cocos significantly inhibits the metastasis of CL1-5 lung cancer cells. FMGP achieves this by inhibiting the TGFβ RI/FAK/AKT signaling pathway and reducing the expression of the metastasis-associated protein Slug. Table 4 summarizes the antitumor bioactivities of Wolfiporia cocos extraction.

TABLE 4

| Model used | Extracts metabolites | Cancer type | Cell line | Human/Mice cell | Activities | Dose range tested | Duration | Minimal active concentration | Control | Sample sources | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In vivo/In vitro | Poricoic acid A | Leukemia | T-ALL | Human | ↑ROS, ↑MDA, ↓GSH. | In vivo: low dose of PAA (5 mg/kg) and high dose of PAA (10 mg/kg), In vitro:1.25 μM–50 μM | In vivo-4 weeks In vitro-24 h | IC50: JURKAT: 4.31 μM MOLT-3: 10.73 μM ALL-SIL: 8.89 μM RPMI-8402: 11.21 μM |

Negative | Wolfiporia cocos surface layer | Chen et al. (2022) |

| In vitro | Pachymic acid | Bladder Cancer | EJ | Human | ↑PARP, ↑ROS, ↑DR5, ↑Bax, ↓Bcl-2 | 0 μM–30 μM | 24 h | 20 μM | Negative | — | Jeong et al. (2015) |

| In vitro | Pachymic acid | Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma | CNE-1/CNE-2 | Human | ↑p-ATM, ↑p-ATR, ↑P-Chk-1, ↑P-Chk-2 | 0 μM–30 μM | 72 h | CNE-1: 13.2 μM CNE-2: 4.8 μM | Negative | — | Zhang et al. (2017) |

| In vitro | Pachymic acid | Gallbladder Cancer | GBC-SD | Human | ↓PCNA, ↓RhoA, ↓ICAM-1, ↓p-ERK1/2 | 10 µg/mL-50 μg/mL | 48 h | 10 μg/mL | Negative | — | Chen et al. (2015) |

| In vivo/In vitro | Pachymic acid | Lung Cancer | NCI-H23/NCI-H460 | Human | ↑ROS, ↑JNK, ↑ER. | In vivo:10, 30, 60 mg/kg, In vitro:0 μM–160 μM | In vivo-3weeks(5 day/week) In vitro-24 h | 20 µM | Negative | — | Ma et al. (2015) |

| In vitro | Polyporenic acid C | Lung Cancer | A549 | Human | ↓PI3-kinase/Akt | 0 μM–200 μM | 72 h | 6 μM | Negative | Poria cocos mushroom kernel | Ling et al. (2009) |

| In vitro | Poricoic acid A/B | Liver Cancer | HepG2 | Human | ↑ROS, ↓COX-2. ↓CDK1, ↓MMP-9 | 0 µg/mL-100 μg/mL | 72 h | 25 μg/mL | Positive | Wolfiporia cocos surface layer | Yue et al. (2023) |

| In vivo | Polysaccharide derivatives | Liver Cancer | HepG2/S-180 | Human | ↑Bax, ↓Bcl-2 | 20 mg/kg | 8days | 0.005 mg/mL | Negative | Wolfiporia cocos mycelia | Huang et al. (2006) |

| In vitro | Pachymic acid | Cervical Carcinoma | Caski | Human | ↓CyclinD1, ↓TRIM9, ↓GSK-3β, ↓C-Myc | 0 μmol/L-20.0 μmol/L | 48 h | 2.5 μmol/L | Negative | Wolfiporia cocos mushroom kernel | Shen and Weng (2020) |

| In vitro | Pachymic acid | Osteosarcoma | HOS | Human | ↑PTEN, ↓p-Akt | 0 μg/mL-50 μg/mL | 72 h | 10 μg/mL | Negative | — | Wen et al. (2018) |

| In vitro | Pachymic acid | Ovarian Cancer | HO-8910 | Human | ↑E-cadherin, ↓COX-2, ↓ β-catenin | 0.5μM–2 μM | 72 h | 0.5 μM | Negative | — | Gao et al. (2015) |

| In vivo/In vitro | Poricoic acid A | Ovarian Cancer | SKOV3 | Human | ↑LC3-I, ↑LC3-II. | In vivo:10 mg/kg,In vitro: 0 μg/mL-80 μg/mL | In vivo-6weeks In vitro-24 h | 30 μg/mL | Negative | — | Ma et al. (2021b) |

| In vitro | Pachymic acid | Prostate Cancer | LNCaP/DU145 | Human | ↓Bad, ↓Bcl-2 | 0 μg/mL-40 μg/mL | 48 h | 10 μg/mL | Negative | Wolfiporia cocos mushroom kernel | Gapter et al. (2005) |

| In vitro | Polysaccharide | Breast Cancer | MDA-MB-231 | Human | ↓SATB1 | 50 mg/L-200 mg/L | 20 h | 100 mg/L | Negative | — | Hu et al. (2019) |

| In vitro | Pachymic acid | Breast Cancer | MDA-MB-231/MCF-7 | Human | ↓PMA, ↓MMP-9 | 0 μM–30 μM | 48 h | — | Negative | — | Ling et al. (2011) |

| In vivo/In vitro | Pachymic acid | Breast Cancer | MDA-MB-231 | Human | ↑PARP, ↓CyclinD1, ↓CDK2, ↓CDK4, ↓Bcl-2/Bax | In vivo:700 mg/kg, In vitro: 5 μg/mL-150 μg/mL | In vivo-25 days In vitro-96 h | 5 μg/mL | Negative/Positive | the ethanol extract of Wolfiporia cocos | Jiang and Fan (2020) |

| In vitro | Pachymic acid | Squamous Carcinoma Of Tongue | CAL-27 | Human | ↑PARP, ↓CyclinD1, ↓CDK2, ↓CXCR4 | 2 μmol/L-8 μmol/L | 48 h | 2 μmol/L | Negative | — | Fan et al. (2021) |

| In vivo/Invitro | Pachymic acid | Kidney Cancer | A498 | Human | ↑TP53INP2, ↑TRAF6 | In vivo: 30/60 mg/kg, Invitro: 0 μM–80 μM | In vivo-28 days In vitro-72 h | 20 μM | Negative | — | Li et al. (2024) |

| In vitro | Pachymic acid | Gastric Cancer | — | Human | ↓MMP2, ↓MMP-9, ↓TIMP1 | 0 μmol/L-160 μmol/L | 28 h | 20 μmol/L | Negative | — | Wang et al. (2022) |

| In vivo/In vitro | Pachymic acid | Gastric Cancer | MKN-49P/SGC-7901 | Human | ↑PPAR, ↓JAK2, ↓HIF1α, ↓Bcl-2/Bax, ↓STAT3 | In vivo: 60 μM, In vitro: 60 mg/kg | In vivo-10 days In vitro-48 h | — | Negative | — | Lu et al. (2018) |

| In vitro | Pachymic acid polyporenic acid C Dehydropachymic acid | Pancreatic Cancer | PANC-1/MIA PaCa-2/AsPc-1/BxPc-3 | Human | ↓KRAS, ↓MMP-7 | 0 µg/mL-80 μg/mL | 72 h | Panc-1: 24.5 μg/mL MiaPaca-2: 23.0 μg/mL AsPc-1: 11.3 μg/mL BxPc-3: 1.0 μg/mL |

Negative | Wolfiporia cocos mushroom kernel | Cheng et al. (2013) |

| In vivo/In vitro | Pachymic acid | Pancreatic Cancer | PANC-1/MIA PaCa-2 | Human | ↑XBP-1s, ↑ATF4, ↑Hsp70, ↑CHOP, ↑p-eIF2α | In vivo: 25/50 mg/kg, In vitro: 0 μM–30 μM | In vivo-5weeks In vitro-24 h | 15 μM | Negative | — | Cheng et al. (2015) |

| In vitro | Dehydroeburicoic acid | Ovarian Cancer | A2780 | Human | ↓MAPKs - caspase3 | 10–100 μM | 24 h | — | Positive | Wolfiporia cocos mushroom kernel | Lee et al. (2017a) |

Antitumor activities in Wolfiporia cocos extraction.

3.2 Regulation of intestinal flora

The gut microbiota is the largest microbial community in the host’s body, known as the 'invisible organ of the human body'. The metabolic capacity of the human gut microbiota is an important factor in affecting nutrient absorption, immune regulation, the maintenance of health and the triggering of disease (Miao et al., 2016). Studies have demonstrated that carboxymethyl Poria polysaccharides (CMP) extracted from Wolfiporia cocos significantly mitigate colon damage induced by 5-fluorouracil (5-FU). This protective effect is associated with the inhibition of reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, an increase in the levels of catalase (CAT), glutathione peroxidase (GSH Px), and glutathione (GSH), as well as a reduction in the expression of pro-inflammatory markers such as NF-κB, p-p38, and Bax. Simultaneously, CMP enhances the expression of the antioxidant factors Nrf2 and Bcl-2. Moreover, CMP is effective in ameliorating gut microbiota dysbiosis caused by 5-FU, promoting an increase in the proportions of beneficial taxa such as Bacteroidetes, lactobacilli, butyrate-producing bacteria, and acetate-producing bacteria, while restoring overall gut microbiota diversity (Wang et al., 2018). Another investigation indicated that CMP can alleviate the cytotoxic effects of 5-FU, while concurrently enhancing the expression of tight junction proteins and related adhesion molecules, thus strengthening the intestinal barrier against GC (Yin et al., 2022). Yu et al. (2022) reported that Poria cocos polysaccharides (PCP) alleviate Chronic Non-Bacterial Prostatitis by modulating gut microbiota. Notably, after fermentation by the human gut microbiota, there was significant enrichment of Parabacterioides, Fusicatenibacter, and Parasutterella. These bacteria metabolize PCP to produce Haloperidol glucuronide and 7-ketodeoxycholic acid, which promote the expression of Alox15 and Pla2g2f in colon epithelium, while downregulating Cyp1a1 and Hsd17b7, thereby inhibiting inflammatory responses. This suggests that the metabolites Haloperidol glucuronide and 7-ketodeoxycholic acid may act as signaling molecules within the gut-prostate axis.

Lai et al. (2022) found that the water-soluble polysaccharide (PCX), water-insoluble polysaccharide (PCY) and triterpenoid saponin (PCZ) in Poria cocos can increase the number of lactobacilli in the intestine and change the content of short chain peptides in intestinal metabolites. Another study found that PCX, alkali soluble polysaccharide and triterpenoid acids have a protective effect on cisplatin induced intestinal injury, mainly by reducing the relative abundance of pathogenic bacteria such as Proteus mirabilis, cyanobacteria, ruminococcaceae and spirobacteriaceae, and promoting the growth of probiotics such as erysipelotticaae and prevotelacae (Zou et al., 2021). Lai et al. (2023) found that PCX can lower levels of inflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-1β, decrease the infiltration of inflammatory cells, and improve intestinal mucosal integrity and barrier function. This was achieved by increasing the relative abundance of beneficial gut microbiota and reducing harmful microbial populations, as manifested by elevated short-chain fatty acid (SCFAs) levels.

Xu et al. (2019) found through experiments that 16α - hydroxytrametinoic acid extracted from Wolfiporia cocos activates glucocorticoid receptor agonists, inhibits the activation of PI3K and Akt, to reduce the phosphorylation of downstream IκB and NF-κB, effectively alleviate TNF - α induced barrier damage in Caco-2 monolayer intestinal epithelial cells. This provides an improved strategy for adjuvant dietary therapy to restore intestinal health. Duan et al. (2023) upregulated the expression of intestinal Occludin and ZO-1, downregulated serum endotoxin, DAO, D-lactate, and intestinal myeloperoxidase (MPO) levels by extracting PCP, enhanced intestinal physical barrier, and increased the expression of MUC2, β-resistin, and SIgA in intestinal tissue, to enhance intestinal biochemical barrier. This indicates that PCP can be used as a functional food to regulate intestinal mucosal function, thereby improving the health of the intestine and host. Moreover, research has found that PCP can not only improve intestinal mucosal barrier function but also increase the diversity of intestinal microbiota to improve antibiotic associated diarrhea in mice (Xu et al., 2023). Table 5 summarizes the bioactivities of Wolfiporia cocos extraction in regulating of intestinal flora.

TABLE 5

| Model used | Extracts metabolites | Cell line/Model | Human/Mice cell | Activities | Dose range tested | Duration | Control | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In vivo | Carboxymethylated pachyman | Colon cancer CT26 | Mice | Increases the proportion of Bacteroidetes, lactobacilli, butyrate producing bacteria, acetate producing bacteria and SCFAs levels | 25 mg/kg | 14 days | Negative/Positive | Wang et al. (2018) |

| In vivo | Poria cocos polysaccharides | ApcMin/+ mice | — | Increases intercellular adhesion protein complexes and beneficial bacteria and reduces potentially pathogenic bacteria | 40 mg/kg | 4 weeks | Negative/Positive | Yin et al. (2022) |

| In vivo | Water-insoluble polysaccharide | C57BL/6 | Mice | Increase in norank_f__Muribaculaceae, unclassified_f__Lachnospiraceae abundance and SCFAs. decrease in Escherichia - Shigella, Staphylococcus and Acinetobacter | 300 mg/kg | 10 days | Negative | Lai et al. (2023) |

| In vivo/In vitro | Poria cocos polysaccharides | Sprague-Dawley mice | — | Increase Parabacteroides, Fusicatenibacter and Parasutterella | In vivo: 250 mg/kg In vitro: Male fecal fermentation | In vivo: 28 days In vitro: 8 h | Negative | Yu et al. (2022) |

| In vivo | Water-soluble polysaccharides, Water-insoluble polysaccharides, Triterpenoid saponins | — | — | Increase lactic acid bacteria and SCFAs levels | PCX: 300 mg/kg, PCY: 300 mg/kg, PCZ: 150 mg/kg | 15 days | Negative | Lai et al. (2022) |

| In vivo | Poria powder, Water - soluble polysaccharides, Alkali - soluble polysaccharides, Triterpene acids | C57BL/6 | Mice | Decrease in Proteobacteria, Cyanobacteria, Ruminococcaceae and Helicobacteraceae. Increase in Erysipelotrichaceae and Prevotellaceae | PP: 2.0 g/kg, WP: 7.6 mg/kg, AP: 1.3 g/kg, TA: 6.0 mg/kg | 13 days | Negative | Zou et al. (2021) |

| In vitro | 16α - Hydroxytrametenolic acid | Caco – 2/293T/RAW 264.7 | Mice | Inhibition of PI3K/Akt/NF-κB signaling pathway | 10 μM–80 μM | 24 h | Negative/Positive | Xu et al. (2019) |

Regulation of intestinal flora activities in Wolfiporia cocos extraction.

3.3 Antioxidation activity

Oxidation refers to the chemical reaction process between substances and oxygen, oxidative stress is a pathological state in which the redox homeostasis of an organism is imbalanced. It arises from the excessive production of reactive nitrogen species and ROS by the organism when subjected to external or internal stimuli, thereby breaking the original dynamic balance mechanism (Tabei et al., 2023). There are reports proving that supplementing exogenous antioxidants can eliminate free radicals and delay disease progression (Rahbari et al., 2015). However, artificially synthesized antioxidants are harmful to human health, such as liver damage and gout (Wang et al., 2016). Therefore, in this era of pursuing health and wellness, it is necessary to develop natural antioxidants to replace the current artificially synthesized antioxidants.

Recent experimental results have shown that the antioxidant capacity of hydroxymethyl PCP derivatives (PCP-C1, PCP-C2, PCP-C3) is directly related to the degree of carboxymethylation. The results showed that these derivatives possessed free radical scavenging and ferrous ion chelating efficacy, among which PCP-C3 protected renal cells from oxalate-induced oxidative damage, increased cell viability and antioxidant enzyme activities, and reduced the accumulation of harmful oxidative stress products. This suggests that PCP-C3 is a potential anticholinergic drug with great potential (Li CY. et al., 2021). Zhao et al. (2020) found that PCP effectively alleviated oxidative stress induced by oxidised low-density lipoprotein (oxLDL) by decreasing ROS and malondialdehyde (MDA) levels in vascular smooth muscle cells, while increasing superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity. By activating the ERK1/2 signalling pathway, the translocation of Nrf2 and the expression of heme oxygenase-1 were promoted, and the upregulation of Lectin-like oxidised LDL receptor-1 (LOX-1) was inhibited to reduce the uptake of oxLDL, which enhanced the antioxidant capacity of the cells. Fang et al. (2021) found that Wolfiporia cocos extract significantly reduced oxidative stress caused by ROS such as hydrogen peroxide, thereby inhibiting the activity of matrix metalloproteinases and reducing the degradation of collagen. At the same time, it can also upregulate the level of transforming growth factor beta 1 (TGF-β1), promote the regeneration and repair of skin cells, enhance the expression of antioxidant related proteins, and further enhance the antioxidant capacity of skin. This indicates that Wolfiporia cocos extract effectively delays the process of skin aging, providing the strong scientific basis for the development of new anti-aging cosmetics.

Wu et al. (2020) demonstrated through experiments that PCP has significant reducing and good scavenging abilities against DPPH, superoxide anions and hydroxyl radical and may be one of the main material bases for its antioxidant properties. Tang et al. (2014) found that PCP derivatives (PCP-1, PCP-2, and PCP-3) exhibit the ability to scavenge hydroxyl radicals and ABTS radicals, and they function through chelation of ferrous ions, thereby reducing the concentration of free ferrous ions and inhibiting oxidative stress responses. Xu et al. (2020) found that Wolfiporia cocos, an ingredient in Bajitianwan (BJTW), can reduce malondialdehyde (MDA) levels in the brain while simultaneously increasing the concentrations of catalase (CAT) and glutathione peroxidase (GSH Px) in serum. This dual action not only mitigates oxidative stress but also facilitates the upregulation of Forkhead box O1 (FoxO1) expression in bone tissue and enhances the levels of superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2), thereby providing protection to both the bone and nervous system from oxidative damage. This suggests that BJTW has great potential in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease and osteoporosis. Table 6 summarizes the bioactivities of Wolfiporia cocos extraction in antioxidation.

TABLE 6

| Model used | Extracts metabolites | Cell line/Model | Human/Mice cell | Activities | Dose range tested | Duration | Control | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In vitro | Carboxymethylated, Poria cocos polysaccharides | — | — | Scavenging free radicals and chelating ferrous ions | 20 μg/mL-100 μg/mL | 24 h | Negative/Positive | Li et al. (2021a) |

| In vitro | Poria cocos polysaccharides | VSMCs | Human | Inhibition of oxidized low-density lipoprotein-induced oxidative stress | 50 μg/mL-200 μg/mL | 24 h | Negative | Zhao et al. (2020) |

| In vitro | Poria cocos polysaccharides | Hs68 | Human | Scavenging of DPPH, superoxide anion and hydroxyl radicals | 100 μg/mL-400 μg/mL | 24 h | Negative | Wu et al. (2020) |

| In vitro | Poria cocos polysaccharides | — | — | Scavenging hydroxyl radicals, ABTS radicals and chelating ferrous ions | 1 mg/mL 10 mg/mL | 4 h | Negative/Positive | Tang et al. (2014) |

Antioxidant activities in Wolfiporia cocos extraction.

3.4 Anti-inflammatory activity

Inflammatory responses are known to be present in various disease processes. A study reported that CMP could regulate the balance of pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines in intestinal tissues by decreasing the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6) and increasing the levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines (IL-10, TGF-β), significantly preventing inflammatory bowel disease in mice (Liu et al., 2018). Song et al. (2018) found that PCP inhibits RANKL induced osteoclastogenesis by suppressing the activity of NFATc1 and the phosphorylation of ERK and STAT3. This suggests that PCP prevents and attenuates pathological fractures caused by bone resorption by interfering with the signalling pathway, decreasing osteoclast differentiation, and reducing bone resorption. Wu et al. (2022) established a fungal infection-induced peritonitis (FIP) mouse model and observed that polysaccharide compounds significantly alleviated inflammatory infiltration and cellular apoptosis in the thymus and spleen tissues. This effect is attributed to the reduction of inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β, effectively ameliorating the inflammatory response. Additionally, PCP was found to decrease the levels of oxidative stress markers, including malondialdehyde (MDA) and myeloperoxidase (MPO), thereby mitigating oxidative damage. Wang et al. (2024) established a mouse model of bleomycin (BLM)-induced pulmonary fibrosis and found that PA inhibited BLM-induced increases in NLRP3, ASC, IL-1 β, P20, and TXNIP, decreased the levels of pro-inflammatory factors (IL -6 and TNF- α), and increased the level of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 in mouse lung tissue. It also reduced the levels of hydroxyproline and MDA in lung tissue and increased the activities of superoxide dismutase and glutathione peroxidase.

Li W. et al. (2021) explored the potential protective mechanism of PCP on compulsory spondylitis by establishing in the ApoE−/− mice model induced by high-fat diet, and found that PCP can inhibit the increase of serum inflammatory mediators and blood lipids. Through experiments, it was found that PCP can significantly reduce the release of inflammatory mediators TNF - α, IL-6, and NO in serum, thereby protecting blood vessels from inflammatory invasion and reducing the elevation of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, triglycerides, and total cholesterol in blood lipids. It also inhibits the activation of TLR4/NF-κB pathway in the aorta and blocks the expression of MMP-2 and ICAM-1. This indicates that PCP can intervene in ankylosing spondylitis by reducing inflammatory factors and blood lipid levels. Gui et al. (2021) conducted experiments by establishing a mouse model of fecal - induced peritonitis. They discovered that PA effectively ameliorated the pathological changes in the lung tissue of rats with pneumonia. This was achieved by inhibiting the activation of the NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways, thereby reducing the release of inflammatory cytokines. Simultaneously, PA could also inhibit cell apoptosis, which further protected the damaged tissues and promoted the resolution of inflammation. These findings revealed the therapeutic potential of PA in inflammatory diseases and provided a scientific basis for the development of new anti-inflammatory drugs. Wu et al. (2023b) established a mouse model of osteoarthritis (OA) and found that PA promotes the expression of SIRT6, which inhibits the activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway. This modulation leads to a reduction in the production of inflammatory mediators such as inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), as well as the suppression of IL-1β-induced inflammatory responses. Additionally, PA was found to reverse the abnormal upregulation of matrix metalloproteinase-3 and platelet-activating factor-5 in OA chondrocytes, while also downregulating the expression of type II collagen and aggrecan. These findings indicate that PA holds significant potential for the treatment of osteoarthritis. Table 7 summarizes the bioactivities of Wolfiporia cocos extraction in anti-inflammatory.

TABLE 7

| Model used | Extracts metabolites | Cell line/Model | Human/Mice cell | Activities | Dose range tested | Duration | Control | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In vivo | Poria cocos polysaccharides | FIP | — | Reduction TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β levels | 200 mg/kg, 400 mg/kg | 21 days | Negative | Wu et al. (2022) |

| In vivo | Pachymic Acid | BLM | — | Decreases IL-6 and IL-1β levels. Increases IL-10 levels | 25, 50,100 mg/kg | 28 days | Negative/Positive | Wang et al. (2024) |

| In vivo | Poria cocos polysaccharides | HFD | — | Reduction TNF-α, IL-6, and NO levels | 100 mg/kg, 200 mg/kg, 400 mg/kg | 11weeks | Negative | Li et al. (2021b) |

| In vivo/In vitro | Pachymic acid | Osteoarthritis in mice | — | Reduction NO, PGE2, TNF-α, IL-6, iNOS, COX-2 release | In vivo: 50 mg/kg, in vitro: 20 μM | In vivo: 8weeks, In vitro:48 h | Negative | Wu et al. (2023b) |

| In vitro | coriacoic acid A, coriacoic acid B, dehydroeburiconic acid, eburicoic acid, poricoic acid C | RAW 264.7 | Mice | Inhibition of iNOS, COX-2 and NF-κB protein levels and reduction of LPS-induced phosphorylation of IKKα and IκBα | 50 μM–100 μM | 24 h | Negative/Positive | Lee et al. (2017b) |

Anti-inflammatory activities in Wolfiporia cocos extraction.

3.5 Immunomodulation activity

Wolfiporia cocos has immunomodulatory effects, and its extract can be used as a natural immune agent. There are reports indicating that PCP can increase NO by activating the Ca (2+)/PKC/p38/NF - κ B signalling pathway, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6 and intracellular calcium level, thereby enhancing the immune response of RAW 264.7 macrophages (Pu et al., 2019). Liu et al. (2021) found that Wolfiporia cocos derivatives CMP-1 and CMP-2 have a triple helix structure, which can improve the secretion of NO, TNF - α, and IL-6 by increasing the expression of iNOS, TNF–α and IL-6 mRNA, and enhance the immune function of RAW 264.7 macrophages.

Liu et al. (2020) established a model of anthrax protective antigen (APA) by extracting polysaccharide PCP-I from Wolfiporia cocos as an immune adjuvant. They found that PCP-I not only significantly enhanced anthrax specific anti APA antibodies, toxin neutralizing antibodies, anti-APA antibody affinity, as well as IgG1 and IgG2a levels, but also increased the frequency of APA specific memory B cells, increased the proliferation of PA specific spleen cells, significantly stimulated IL-4 secretion, enhanced the activation of dendritic cells in vitro, and improved the survival rate of mice immunized with anthrax lethal toxins. This indicates that polysaccharide PCP-I extracted from Wolfiporia cocos can activate immune signalling pathways, trigger immune synergy, and provide more effective immune responses. PCP-I is a very promising immune adjuvant. Chao et al. (2021) discovered that tumulosic acid, poronic acid C, and three-epi dehydrotumulosic acid—components of lanostane triterpenoids extracted from Wolfiporia cocos—can significantly stimulate the secretion of IFN-γ by mouse spleen cells. Concurrently, these lanostane triterpenoids activate natural killer cells, enhancing non-specific (innate) immunity and promoting the Th1 immune response, which leads to increased IFN-γ secretion. Additionally, they reduce the secretion of IL-4 and IL-5, cytokines associated with allergic reactions and the Th2 immune response. This research demonstrates that extracts from Wolfiporia cocos have the ability to modulate the Th1/Th2 immune response, potentially reducing the incidence of allergic diseases and positioning them as promising candidates for the development of anti-allergic therapies.

Liu et al. (2022) found that PCP significantly increased the activity of four enzymes related to immunity and energy metabolism (phenoloxidase, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, hexokinase, and fatty acid synthase), thereby significantly enhancing the cellular immunity of silkworms, including the ability of hemocyte phagocytosis, microaggregation and spreading. This indicates that PCP can regulate the immune system by enhancing cellular immunity, modulating immune responses, and regulating the expression levels of physiological metabolism related genes. Zhang W. et al. (2023) found that the polysaccharides PCWPW and PCWPS from Wolfiporia cocos contain some fucose and mannose residues, which could interact with mannose receptor on the surface of macrophages. By experimentally treating the polysaccharides PCWPW and PCWPS with the inhibitors, the secretion of TNFα was inhibited and NF-κB and MAP. Table 8 summarizes the bioactivities of Wolfiporia cocos extraction in immunomodulation.

TABLE 8

| Model used | Extracts metabolites | Cell line/Model | Human/Mice cell | Activities | Dose range tested | Duration | Control | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In vitro | Poria cocos polysaccharides | RAW 264.7 | Mice | Increase NO and activation of Ca(2+)/PKC/p38/NF-κ B | — | 72 h | Negative | Pu et al. (2019) |

| In vitro | Carboxymethyl pachymaran | RAW 264.7 | Mice | Upregulation of mRNA expression of iNOS, TNF-α and IL-6 | 12.5 μg/mL- 400 μg/mL | 24 h | Negative/Positive | Liu et al. (2021) |

| In vivo/In vitro | Polysaccharide PCP-I | J774A.1/BMDCs | Mice | Activation of T cells and IL-4 secretion | — | 68 h | Negative/Positive | Liu et al. (2020) |

| In vivo | lanostane Triterpenoids | BALB/c | — | Stimulation of IFN-γ and inhibition of the Th2 response | 2.5, 5, 10, 20 mg/kg | 9weeks | Negative/Positive | Chao et al. (2021) |

| In vivo | Poria cocos polysaccharides | Bombyx mori | — | Regulation immune signal recognition | 0.1, 0.2, 0.4 μg/larval | 24 h | Negative | Liu et al. (2022) |

| In vitro | PCWPW/PCWPS | RAW264.7 | Mice | Activates MAPK, NF-κB and promotes TNF-αsecretion, mRNA expression | 200, 400, 800 μg/mL | 24 h | Negative/Positive | Zhang et al. (2023a) |

Immunomodulation activities in Wolfiporia cocos extraction.

3.6 Regulation of glycolipid metabolism

Wolfiporia cocos regulates metabolism mainly by regulating glucose and lipid metabolism disorders. Glucose metabolism is a complex process of sugar synthesis and decomposition in the body, and abnormal enzymes and other factors involved in synthesis and metabolism will lead to glucose metabolism disorders (Zhang et al., 2022). Genetic, environmental, or pathological conditions can lead to abnormal levels of blood lipids and lipoproteins, resulting in lipid metabolism (Badmus et al., 2022). Studies have shown that crude extracts of Wolfiporia cocos and its triterpenoids such as dehydrotumulosic acid, dehydrotrametinonic acid and pachymic acid can significantly reduce postprandial blood glucose in db/db mice. Further studies on a mouse model treated with streptozotocin showed that the crude extract of Wolfiporia cocos and triterpenoids exhibited insulin sensitizing activity, but not insulin releasing activity. This suggests that the active ingredients of Wolfiporia cocos may enhance insulin sensitivity through a pathway that is not dependent on PPAR-γ, thereby reducing blood glucose levels (Li et al., 2011).

Hyperlipidemia is an important factor leading to atherosclerosis. Some experimental studies have proved that after treatment with Wolfiporia cocos, hyperlipidemia and related lipid metabolite abnormalities were significantly improved (Miao et al., 2016). Kim et al. (2019) found that Poria cocos Wolf (PCW) extract can effectively improve liver steatosis. In vitro HepG2 cell experiments and in vivo high-fat diet mouse models, it was found that PCW can significantly reduce triglyceride levels in cells and mouse liver while affecting the expression of genes related to fat production, fatty acid oxidation, endoplasmic reticulum stress, and autophagy. PCW reduces fat production and promotes fatty acid oxidation by activating AMPK and its downstream pathways while inhibiting endoplasmic reticulum stress and inducing autophagy. These findings indicate that Wolfiporia cocos has the potential to be used for the treatment of hepatic steatosis. Sun et al. (2019) found that PCX extracted from the sclerotia of Wolfiporia cocos can significantly enhance glucose and lipid metabolism, as well as reduce liver steatosis in ob/ob mice. The mechanism of action for PCX involves increasing the abundance of butyrate-producing bacteria in the intestine, which in turn elevates intestinal butyrate levels, enhances the integrity of the intestinal mucosa, and activates the intestinal PPAR-γ pathway. Zhu et al. (2022) by establishing a high-fat diet (HFD) - induced obese mouse model, it was found that Wolfiporia cocos oligosaccharides(PCO) can reverse the imbalance of gut microbiota and changes in microbial metabolites, repair the intestinal barrier, reduce hyperglycemia, glucose tolerance, and insulin resistance in HFD mice, decrease the size of adipocytes, inhibit fat accumulation, and improve the disorder of glucose and lipid metabolism. This indicates that PCO, as a novel prebiotic, has great potential in the treatment of glucose and lipid metabolism diseases. Wang et al. (2023) found that CMP can significantly reduce fat weight and serum lipids, improve glucose tolerance, effectively reduce lipid droplet content in liver tissue, and promote cholesterol and lipid metabolism by reducing the synthesis of liver bile acids. They also found that CMP regulates the metabolism of glucose and lipid and energy balance by enhancing the abundances of Bifidobacterium, Bacteroides, and Akkermansia intestinal microbiota. Pan et al. (2023) found that Wolfiporia cocos acid can alleviate lipid metabolism disorders in mouse primary liver cells induced by OA-palmitic acid by activating SIRT6 signalling pathway. By using molecular docking, it was found that SIRT6/PPAR - α can promote fatty acid oxidation and SIRT6/Nrf2 can enhance antioxidant activity. The interaction between the two is a new target for the treatment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Table 9 summarizes the bioactivities of Wolfiporia cocos extraction in regulating of glycolipid metabolism.

TABLE 9

| Model used | Extracts metabolites | Cell line/Model | Activities | Dose range tested | Duration | Control | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In vivo/In vitro | Dehydrotumulosic acid, Dehydrotrametenolic acid, Pachymic acid | db/db/C57BL mice | Enhancement insulin sensitivity to lower blood sugar | In vivo: 1, 5, 10 mg/kg. In vitro: 10、40、100 μM | 24 h | Negative/Positive | Li et al. (2011) |

| In vivo | Wolfiporia powder | HLA mice | Regulation of fatty acid and sterol lipid metabolism | 250 mg/kg | 6weeks | Negative | Miao et al. (2016) |

| In vivo/In vitro | Poricoic acid, Pachymic acid Ergosterol | HepG2/C57BL/6 mice | Inhibition lipogenesis and stimulates fatty acid oxidation | In vivo: 100,300 mg/kg, In vitro: poricoic acid: 6.25–100 μM, pachymic acid/ergosterol: 0.63–10 μM | In vivo: 6weeks, In vitro: 24 h | Negative | Kim et al. (2019) |

| In vivo | Water insoluble polysaccharide | ob/ob mice | Improvement of intestinal mucosal integrity and activation of intestinal PPAR-γ pathway | 1 g/kg-1, 0.5 g/kg-1 | 4 weeks | Negative/Positive | Sun et al. (2019) |

| In vivo | Poria cocos oligosaccharides | HFD mice | Regulation of BAs, SCFAs and tryptophan metabolites | 200 mg/kg | 16 weeks | Negative | Zhu et al. (2022) |

| In vitro | Pachymic acid | MPHs | Promotion fatty acid oxidation and reduces lipid deposition | 12 μM–50 μM | 24 h | Negative | Pan et al. (2023) |

Regulation of glycolipid metabolism activities in Wolfiporia cocos extraction.

3.7 Improvement of organ function

Through research, it has been found that the active ingredients in Wolfiporia cocos have the ability to improve the function of human organs such as the heart (Xie et al., 2023), liver (Jiang et al., 2022) and kidneys (Wu et al., 2023a). Table 10 summarizes the bioactivities of Wolfiporia cocos extraction in improving of organ function.

TABLE 10

| Model used | Extracts metabolites | Cell line/Model | Human/Mice cell | Mechanism | Dose range tested | Duration | Control | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In vivo | Pachymic acid | HS mice | — | Inhibition of cardiomyocyte apoptosis | 7.5, 15 mg/kg | 3days | Negative | Liu et al. (2023) |

| In vivo | Poria cocos polysaccharides | MI/RI mice | — | Inhibition of ROS production thereby reducing cardiomyocyte apoptosis | 100, 200 mg/kg | 7days | Negative/Positive | Xie et al. (2023) |

| In vitro | Pachymic acid | H9c2 | Human | Reduces TNF-α, IL-1, and IL-6 release and inhibits apoptosis in cardiomyocytes | 0.125–20 μM | 24 h | Negative | Li et al. (2015) |

| In vivo | Poria cocos polysaccharides | NASH | — | Inhibition NF - κB activation and CCL3/CCR1 mRNA expression. Protects liver tissue | 150, 300 mg/kg | 4 weeks | Negative | Tan et al. (2022) |

| In vivo | Poria cocos polysaccharides | Gao-Binge | — | Inhibition the CYP2E1/ROS/MAPKs signaling pathway. Ameliorates apoptosis in liver cells | 25, 50, 100 mg/kg | 16 days | Negative/Positive | Jiang et al. (2022) |

| In vivo/In vitro | Poria cocos polysaccharides | APAP/AML12 | Mice | Decrease TNF-β and TNFsR-Ⅰ levels. Reduces hepatocyte inflammation | In vivo: 200, 400 mg/kg, In vitro: 20, 40 g/L | In vivo:14days, In vitro:48 h | Negative/Positive | Wu et al. (2019) |

| In vivo | Poria cocos polysaccharides | APAP | — | Decrease serum levels of TNF-α, IL-6, and increase expression of AKR7A, c-Jun, and Bcl-2 in liver tissue | 200, 400 mg/kg | 14days | Negative | Wu et al. (2018) |

| In vivo/In vitro | Poricoic acid A | UUO/NRK-49F | Mice | Inhibition twist, snail1, MMP-7, and PAI-1. reduces renal fibroblast production | In vivo: 10 mg/kg, In vitro: 10 μM | In vivo: 2weeks, In vitro: 48 h | Negative/Positive | Chen et al. (2023) |

| In vivo/In vitro | Poricoic acid A | DKD/MPC5 | — | Increase LC3 and ATG5 levels and decrease p62 and FUNDC1 levels. Reduces kidney injury | In vivo: 10, 20 mg/kg, In vitro:0 μg/mL-200μg/mL | In vivo: 4 weeks, In vitro: 24 h | Negative | Wu et al. (2023a) |

| In vitro | Poricoic acid A | TGF-β1/NRK-49F | Mice | Inhibit PDGF-C, Smad3 and MAPK signaling pathways. Reduce renal fibroblast proliferation | 1μM–20 μM | 24 h | Negative | Li et al. (2021c) |

| In vivo | Pachymic acid | CKD | — | Upregulates renal klotho levels and inhibits the Wnt/β - catenin signaling pathway. Reduces renal inflammation | 10 mg/kg | 4 weeks | Negative/Positive | Younis et al. (2022) |

| In vitro | Poricoic acid ZA | TGF-β1/ANGII | — | Inhibition the renin-angiotensin system and the TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway. Reduce renal fibrosis | 10 μM | Negative/Positive | Wang et al. (2017) |

The mechanism of improving organ function in Wolfiporia cocos extraction.

3.7.1 Improve heart function

A study has reported that by establishing a myocardial ischemia (MI/RI) rat model, Wolfiporia cocos polysaccharides reduce the levels of LDH, CK-MB, IL-1 β, IL-18, and MDA in myocardial tissue. At the same time, they reduce the relative expression levels of Bax, cleaved caspase-3, RhoA, ROCK1, and p-MYPT-1 proteins, as well as increase the relative expression levels of SOD and Bcl-2 proteins in myocardial tissue, thereby improving tissue edema and microcirculation disorders, and weakening pathological damage and myocardial cell apoptosis. Meanwhile, by downregulating the levels of RhoA, ROCK1, and downstream signalling factor p-MYPT-1 in MI/RI rat myocardial tissue, the activation of the Rho ROCK signalling pathway is inhibited, the activation of inflammasomes is reduced, and myocardial cell oxidation and inflammatory damage are alleviated, thereby reducing myocardial cell apoptosis (Xie et al., 2023). Liu et al. (2023) found that the triterpenoid compound PA extracted from Wolfiporia cocos can reduce the levels of IL-1 β, IL-6, and TNF-α by inhibiting the pro-inflammatory NF-κB signalling pathway, thereby improving hematopoietic shock (HS) - induced cardiac inflammation. Coincidentally, PA weakens the increase in HS induced cardiac monocyte/macrophage and neutrophil infiltration, as well as inhibits HS induced M1 polarization and exaggerates M2 polarization in myocardial tissue, reducing cardiac damage, inhibiting cell apoptosis, and improving cardiac inflammatory response. Li et al. (2015) found that PA exhibited significant effects in inhibiting lipopolysaccharide (LPS) - induced apoptosis and inflammatory response in H9c2 cardiomyocytes. Through PA treatment, the upregulation and release of TNF-α, IL -1, and IL-6 inflammatory factors in myocardial cells can be significantly reduced. At the same time, PA inhibits LPS induced myocardial cell apoptosis by suppressing the phosphorylation of extracellular regulated kinase (Erk) 1/2 and p38 signalling pathways. This discovery suggests that PA may be a potentially effective drug for treating LPS induced myocarditis and apoptosis, providing a new strategy for treating inflammation related cardiovascular diseases.

3.7.2 Improve liver function

In the early stages, research on carboxy methyl Poria cocos polysaccharide (CMPCP) for chronic viral hepatitis has been conducted. Through experiments, it was found that CMPCP can improve liver function and enhance non-specific cell-mediated immune function, without cytotoxic effects. This study was a preliminary investigation of the use of Wolfiporia cocos in the treatment of liver diseases (Guo et al., 1984). With the constant evolution of social times, pressures and other factors have led to an increasing intake of alcohol, gradually making alcoholic liver disease (ALD) the leading chronic liver disease worldwide, placing a heavy burden on the global public health system (Zhang N. et al., 2023). There are research reports that the active Poria cocos polysaccharide (PCP-1C) improves ALD by inhibiting the TLR4/NF-κB and CYP2E1/ROS/MAPK pathways, repairing the intestinal barrier and reducing LPS leakage, thereby reducing liver injury, inflammation, oxidative stress, and intestinal leakage (Jiang et al., 2022). Tan et al. (2022) established a non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) model by administering methionine and choline deficiency diet to C57BL/6 mice for 4 weeks. They found that Wolfiporia cocos polysaccharides can reshape the composition of intestinal bacteria by significantly increasing the relative abundance of Faecalibaculum and reducing the endotoxin load level from intestinal bacteria. This suggests that Wolfiporia cocos polysaccharides can provide a new potential strategy for the prevention and treatment of NASH. Wu et al. (2019) demonstrated through experiments that PCP can reduce Hsp90 cells, be beneficial for acetaminophen-induced liver cell damage, and enhance its hepatoprotective effect. PCP (Wu et al., 2018) can alleviate liver injury in a dose-dependent manner by downregulating the expression of NF-κB/p65 and IkB α.

3.7.3 Improve kidney function

Chen et al. (2023) found that inducing renal interstitial fibrosis in rats or mice by establishing unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO), and PAA from Wolfiporia cocos can promote β-catenin K49 deacetylation, significantly inhibit renal fiber cell activation, and improve renal function. At the same time, Wu et al. (2023a) by establishing a model of diabetes nephropathy (DKD) and extracting PAA from Wolfiporia cocos, found that PAA can significantly reduce the levels of blood sugar and urinary protein in mice, control renal fibrosis, and downregulate FUNDC1 to promote mitosis, thus having a beneficial impact on the damage of capsular cells in DKD and effectively alleviating renal damage. There is experimental evidence (Li Q. et al., 2021) that PAA inhibits the PDGF-C, Smad3, and MAPK pathways to suppress TGF-β1 induced ECM accumulation, fibrosis formation, and proliferation in renal fibroblasts. Fu et al. (2022) found that Wolfiporia cocos polysaccharides can not only induce proliferation and differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells, but also reduce the level of pro-inflammatory cytokines to improve kidney morphology, thereby improving chronic kidney disease. Younis et al. (2022) found through experiments that PA has an upregulation effect on renal klotho, thereby inhibiting Wnt/β - catenin reactivation and downregulating RAS gene expression, which brings benefits to the treatment of chronic kidney disease (CKD). At the same time, Wang et al. (2017) confirmed that Poricoic acid ZA extracted from Wolfiporia cocos is used as a renin-angiotensin system inhibitor for the treatment of CKD. It blocks the interaction between Smad2/3-TGF β RI proteins and inhibits Smad2/3 phosphorylation, thereby inhibiting RAS the TGF - β/Smad pathway, ultimately leading to the treatment of chronic kidney disease.

4 Toxicology