Abstract

Multifunctional ligand-binding domains have revolutionized cell biology by enabling the precise visualization and manipulation of fused proteins of interest through small molecule probes. Employing these domains is labor-intensive and low-throughput, limiting studies to only small subsets of proteins at a time. However, advancements in high-throughput technologies like pooled protein tagging have enabled the tagging of proteins across the entire proteome with ligand-binding domains. This allows for the generation of complex cell libraries where each cell expresses a different protein fused to a generic, ligandable handle. These libraries unlock opportunities to explore the proteome with a versatile toolbox of small molecule probes designed to interact with the fused tags, allowing researchers to visualize protein localization, induce protein misfolding, manipulate protein-protein interactions, modulate protein stability, and more in a scalable, systematic manner. This review explores recent studies employing multifunctional domains at proteome scale, delving into how the associated chemical probes have been employed to enable insights into endogenous protein function, cellular processes, and disease mechanisms. Additional multifunctional ligand-binding domains are discussed that can be used in pooled protein tagging, as well as their potential strengths and weaknesses. We also discuss potential applications in drug discovery such as high-throughput screening for therapeutic targets with insights for bifunctional ligand optimization. By integrating pooled protein tagging with ligand-binding domains and chemical probes, we highlight how the fusion of chemical biology and functional genomics is paving the way for innovative research avenues and transformative advances in cell biology and pharmacology.

1 Introduction

Genetic tagging of cellular proteins has transformed molecular and cellular biology research by enabling precise control over protein behavior, allowing researchers to study protein localization, function, interactions, and local environment. Ligand-binding domains are a family of protein tags that bind small molecule ligands with a broad range of applications, enabling precise dissection of protein function in living cells based on the chosen ligand. Despite the versatility of ligand-binding domains, their large-scale application has been hindered by the challenges associated with single-gene tagging approaches. Traditional methods for endogenous tagging, such as homologous recombination or CRISPR-mediated knock-in, are labor-intensive and inherently low-throughput, requiring individual genetic modifications for each target protein followed by screening for properly-modified clones. As a result, studies employing multifunctional ligand-binding domains have typically been restricted to focused experiments studying individual proteins. To address some of these limitations, arrayed tagging of endogenous genes by homology directed repair (HDR) with a small protein tag has provided an effective solution for systematic protein labeling (Cho et al., 2022). However, even with these advancements, the need for gene-specific donor designs has remained a bottleneck. Overexpression-based protein fusions that use ectopically expressed proteins fused to tags reveal insight into protein function at scale (Yen et al., 2008; Poirson et al., 2024) although time-intensive molecular cloning and differences in expression levels relative to endogenous contexts should be taken into consideration.

Recent advancements in genomic engineering have enabled endogenous pooled protein tagging approaches, facilitating the systematic study of protein function at scale. Such strategies, when combined with multifunctional ligand-binding domains, allow for proteome-wide interrogation of endogenous protein dynamics using a common set of chemical probes. This review explores key studies that have leveraged protein tagging to enable high-throughput imaging, protein destabilization, induced proximity, and targeted protein degradation. Additionally, we examine the latest technological developments in genome-scale tagging and their implications for studying protein function in complex cellular systems. Finally, we consider future directions, including promising ligandable domains for use in pooled systems, as well as the application of these tools for drug discovery. By integrating chemical biology with pooled screening methodologies, this emerging field is poised to provide transformative insights into proteome organization, protein function, and therapeutic target discovery.

2 Proteome-scale pooled tagging approaches

CRISPR-based endogenous gene tagging methods and ORFeome libraries have made it possible to move beyond single-protein experiments and systematically study thousands of proteins in a pool. These large-scale approaches are vital for systematic functional studies, especially when combined with chemical probes to interrogate protein behavior, localization, and interactions on a proteome-wide level. Tagging endogenous genes allows for the opportunity to investigate proteins under their native regulatory control, allowing capture of physiological expression patterns, stoichiometries, and post-transcriptional regulation. While the aforementioned properties are often lost in overexpression systems, better control over the expression and composition of the expressed genes provides alternative benefits. In this section, we review the state-of-the-art approaches for generating pooled tag libraries.

2.1 Retroviral-based tagging systems

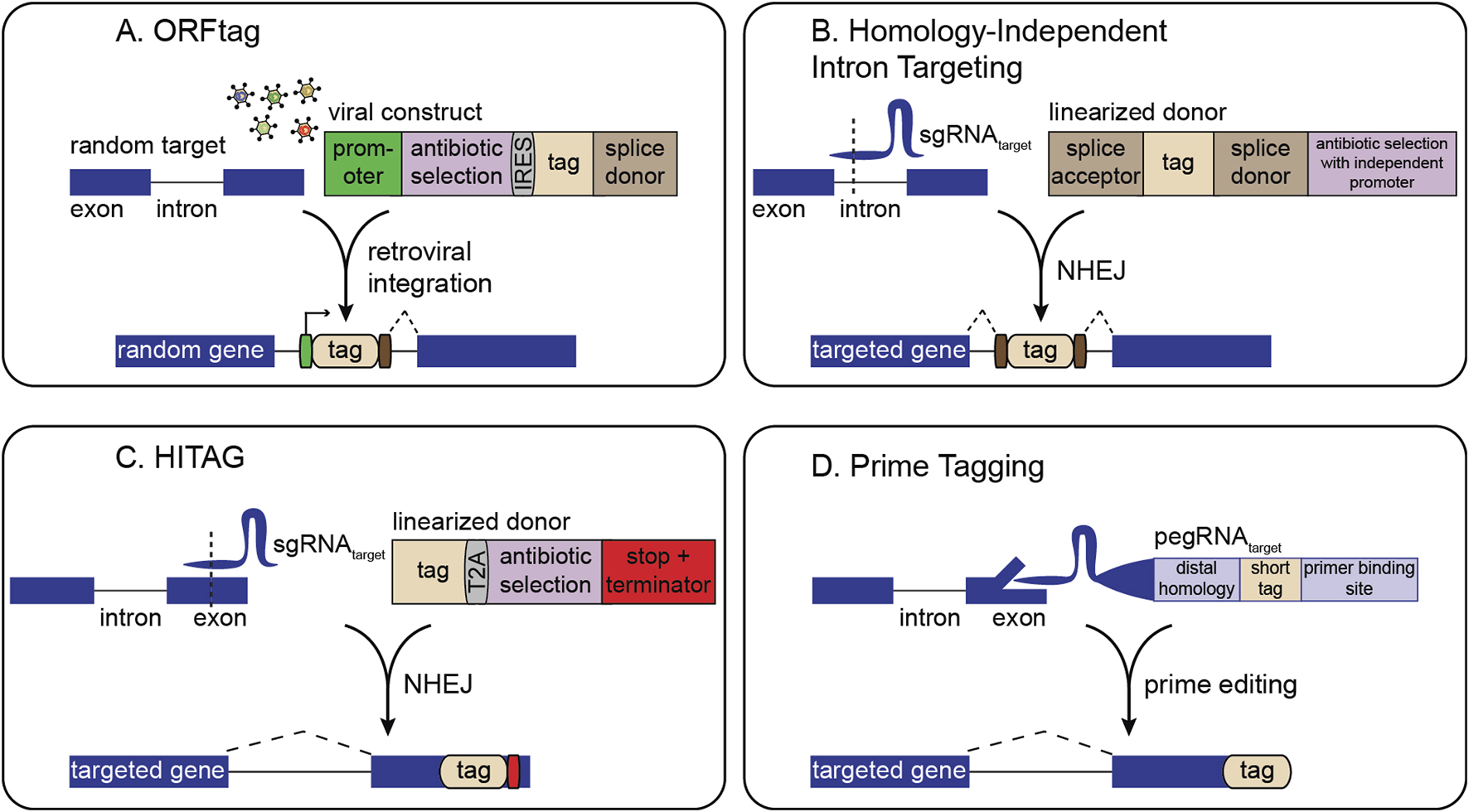

Early generic tagging strategies used retroviral vectors to insert synthetic exons carrying a fluorescent protein flanked by splice acceptor and donor sites to a random location in the genome (Jarvik et al., 1996, Jarvik et al., 2002; Sigal et al., 2006a; Sigal et al., 2006b; Cohen et al., 2008). Although cell lines generated in these initial approaches were not studied in a pooled fashion, they laid groundwork for methods such as ORFtag (Nemčko et al., 2024), which uses a splice donor in a retroviral cassette to achieve internal fusions under an exogenous promoter. These systems can be pooled, and antibiotic markers can be included in the cassette to enable straightforward selection of cells that have integrated the tag (Figure 1A). Identification of tagged sites is performed by inverse PCR-related methods (Nemčko et al., 2024).

FIGURE 1

Overview of strategies for pooled gene tagging. (A) ORFtag utilizes viral integration of a synthetic exon with a splice donor to drive the expression of protein fragments. (B) Homology-independent intron targeting utilizes site-specific integration of a synthetic exon for internal protein tagging. (C) HITAG utilizes site-specific integration of a tag targeting exonic regions near stop codons. (D) Prime tagging uses prime editing to precisely insert short tags directly at protein termini (C-terminal tagging depicted here).

2.2 CRISPR-based pooled tagging

Several methodologies harness CRISPR-induced double-strand breaks (DSBs) combined with non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ) for tag insertion. Here, the only gene-specific reagent required is a single-guide RNA (sgRNA) to direct Cas9 to the locus of interest. A second sgRNA can linearize a generic donor plasmid, facilitating homology-independent tag integration (Figures 1B,C). This design allows the generation of complex cell libraries in which each cell carries a distinct, endogenously tagged protein. For instance, homology-independent intron targeting from Shalem and colleagues integrates synthetic exons within introns, leveraging the fact that introns often harbor many viable CRISPR target sites (Figure 1B) (Serebrenik et al., 2019; Serebrenik et al., 2024; Reicher et al., 2020; Reicher et al., 2024; Sansbury et al., 2025). The resulting fusions are scarless, as even if indels occur, they are outside the splice sites and thus restricted to the intron rather than the coding sequence. Selection markers can also be placed outside the splice sites for easy enrichment of genomic integration events without disrupting the tagged protein. This approach predominantly generates internal gene fusions, thus enabling screening of many fusion varieties for each gene, increasing the likelihood of finding non-disruptive insertion points.

Other NHEJ-driven methods favor inserting tags within exons at or near protein termini (Lackner et al., 2015; Schmid-Burgk et al., 2016; Suzuki et al., 2016). Although NHEJ-based tag integration tends to be high fidelity, exon tagging may result in frameshifts at either end of the tag. Thus, current pooled NHEJ-based exon tagging approaches, such as the ‘high-throughput insertion of tags across the genome’ (HITAG) system, rely on C-terminal tagging where in-frame fusion at the 5′ end is ensured by downstream selection markers, and an exogenous stop codon and termination sequence is used at the 3′ end (Figure 1C) (Kim et al., 2024). NHEJ-based tagging libraries can be analyzed either by inverse PCR or by sgRNA sequencing, making them easily compatible with methods such as single cell RNA sequencing or in situ sequencing (Feldman et al., 2019; Sansbury et al., 2025).

Precise, indel-free N- or C-terminal tagging of endogenous genes can be achieved by prime editing-based pooled tagging, which avoids NHEJ and provides flexibility in choosing the integration site relative to the target sequence (Figure 1D) (Sanchez et al., 2024). Although powerful, pooled prime tagging is currently limited to tags that can be encoded within a pegRNA. Future pooled prime editing approaches can incorporate recombinase landing pads to integrate larger tags (Anzalone et al., 2022; Yarnall et al., 2023; Pandey et al., 2025).

2.3 ORF libraries and overexpression approaches

For studying proteins that are not natively expressed in a given cell line, or where robust overexpression is desired, researchers can turn to exogenous expression libraries (Yang et al., 2011; ORFeome Collaboration, 2016; Tycko et al., 2020; Tycko et al., 2024; Alerasool et al., 2022; DelRosso et al., 2023; Lacoste et al., 2024; Moon et al., 2024; Poirson et al., 2024; Wilson et al., 2024). These libraries, often driven by strong promoters, can also be tagged with fluorophores or multifunctional domains. However, overexpression can introduce non-physiological artifacts, underscoring their complementary use with endogenous tagging approaches. Although exogenous expression can lead to supraphysiological protein levels, expression can sometimes approximate endogenous levels depending on the protein and system used. Therefore, investigators should empirically assess expression in their experimental context. Beyond standard biochemical and high-throughput methods, cytometry-based and live-cell pulse-chase strategies have been utilized for quantifying ligand-binding domain fusion protein abundance and turnover (Cattoglio et al., 2019; Layer et al., 2020).

Regardless of the tagging strategy, the capacity to produce large libraries of tagged proteins opens the door to systematically deploying small molecule probes against the proteome. By coupling these pooled tag systems with chemical modulators or fluorescent ligands, investigators can map subcellular localization changes, affect protein stability, or induce non-native protein-protein interactions in a high-throughput manner.

3 HaloTag-based pooled tagging enables insights into proteome dynamics

HaloTag, derived from a bacterial haloalkane dehalogenase, is one of the most versatile multifunctional ligand-binding domains (Los et al., 2008; Encell et al., 2012; England et al., 2015). Its covalent reaction with chloroalkane ligands proceeds efficiently in mammalian cells, comparable to binding rates exhibited by biotin-streptavidin, providing fast bio-orthogonal labeling that resists hydrolysis and washout (Encell et al., 2012). Multiple HaloTag variants exist, including the stable HaloTag7 and metastable HaloTag2 (Encell et al., 2012; Tae et al., 2012; Huppertz et al., 2024). This flexibility has led to a broad palette of HaloTag ligands for cellular imaging, protein purification, targeted protein modulation, and more. When combined with pooled gene tagging, HaloTag can be fused to many proteins in parallel, creating libraries of endogenously tagged proteins as demonstrated by Scalable POoled Targeting with a LIgandable Tag at Endogenous Sites (SPOTLITES) (Serebrenik et al., 2024; Sansbury et al., 2025). These cell libraries can then be treated with a toolbox of cell-permeable HaloTag ligands to enable visualization and perturbation of the proteome in a variety of ways (Figure 2) (Hoelzel and Zhang, 2020).

FIGURE 2

Summary of HaloTag ligands that can be deployed on SPOTLITES libraries. (A) Fluorescent HaloTag ligands like HaloTag-TMR can be used for visualization of protein levels and localization patterns. (B) Hydrophobic tags can induce destabilization of HaloTag2 which can lead to proteotoxic stress responses. (C) Proximity between HaloTag and other ligand-binding domains or other proteins such as E3 ligases can be induced with a suite of bifunctional ligands. (D) The metastable HaloTag2 can be stabilized by treatment with non-covalent binder HALTS1. (E) A large toolbox of biosensors has been developed for HaloTag. (F) Tagged proteins can be easily purified with chloroalkane resins.

3.1 Pooled labeling with fluorescent HaloTag ligands to visualize proteome dynamics

By treating SPOTLITES-derived cell libraries with fluorescent HaloTag ligands, researchers can quickly assess multitudes of protein localization patterns across various cell compartments at single-cell resolution. A range of fluorescent HaloTag ligands has been developed, offering diverse spectral properties and compatibility with different biochemical environments (Figure 2A) (Los et al., 2008; Grimm et al., 2015). Recent work has demonstrated robust visualization of proteins in most organelles and subcellular structures in HAP1, HEK 293, and HeLa cells, and has enabled insight into the endogenous localization patterns of poorly annotated proteins (Sansbury et al., 2025). Beyond proteome imaging at baseline conditions, pooled imaging is well suited for exploring proteome remodeling at the level of expression and localization induced by various stressors or disease models.

3.2 Pooled protein destabilization provides insights into compartment-specific proteostasis mechanisms

Another distinctive advantage of HaloTag arises from its capacity to respond to hydrophobic tagging. When metastable HaloTag2 binds small molecules appended with hydrophobic moieties like adamantane, it mimics partially misfolded proteins, inducing proteotoxic stress and becoming engaged by proximal protein quality control factors (Figure 2B) (Neklesa et al., 2011; Neklesa et al., 2013; Tae et al., 2012). Targeting HaloTag2 to various compartments followed by induced misfolding has illuminated compartment-specific stress responses in the cytosol (Neklesa et al., 2013), ER (Raina et al., 2014), and the Golgi apparatus (Serebrenik et al., 2018; Hellerschmied et al., 2019). This approach has been recently scaled to a pooled format with SPOTLITES, enabling systematic insight into compartment- and even subcompartment-specific proteotoxic stress responses (Sansbury et al., 2025). Treatment of the cell pool with a hydrophobic HaloTag ligand followed by single-cell transcriptomics to identify both the tagged protein and the distinct transcriptional response in each cell provided a map of spatially-restricted proteotoxic stress responses, and revealed proteostasis-related interactions between organelles (Sansbury et al., 2025). By integrating SPOTLITES with genetic models of diseases like proteinopathies, pooled hydrophobic tagging will allow for detailed dissection of proteostasis states during disease progression and identify new opportunities for therapeutic intervention.

3.3 Pooled protein recruitment to profile molecular functions and develop next-generation induced proximity therapies

Pooled HaloTag fusion libraries treated with generic bifunctional ligands can be leveraged to screen induced protein-protein interactions at scale, enabling unique functional genomics studies linking function to proximity (Figure 2C). These screens additionally hold translational significance for chemically induced proximity (CIP) therapies, which harness a small molecule to bridge a “target” protein to an “effector” protein, as exemplified by targeted protein degradation (TPD) where E3 ligases like VHL or CRBN are recruited to degrade neo-substrates (Bondeson et al., 2015; Winter et al., 2015; Burslem and Crews, 2020). Existing CIP technologies rely on just a few known effectors, utilized primarily for TPD; however, recent proteome-scale proximity screens demonstrate that many other effectors can degrade, stabilize, or otherwise modify target proteins, vastly broadening the CIP landscape (Poirson et al., 2024; Serebrenik et al., 2024).

Pooled recruitment screens based on the SPOTLITES platform used HaloTag-fused proteins recruited to a fluorescent target or an essential target to identify previously unrecognized effectors by fluorescence- or cell growth-based enrichment, respectively (Serebrenik et al., 2024). This work converged on known TPD effectors as well as members of the C-terminal-to-LisH (CTLH) complex and other components of the proteostasis machinery as potent degraders. SPOTLITES-based recruitment offers multiple advantages: (1) endogenous effector tagging preserves physiological expression and stoichiometry, (2) internal tagging allows screening of multiple insertion sites that may favor specific orientations between target and effector, and (3) modular ligands facilitate testing different linker designs and chemical warheads for optimal activity. These pooled approaches accommodate diverse readouts such as fluorescence, viability, or complex phenotypic assays (Kahnwald et al., 2024), and importantly, can be applied not only to TPD but also to protein stabilization, disaggregation, and other post-translational modifications.

By systematically interrogating novel effector–target pairs, recruitment screens uncover both protein function and highlight the wealth of potent modulators in the proteome with unique properties such as cell type-specific expression (Jevtić et al., 2021) or high essentiality in disease contexts (Ottis et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2019; Kurimchak et al., 2022; Hanzl et al., 2023). These datasets will thus provide a starting point for uncovering new biological pathways and targeting a variety of disease mechanisms with selective and resistance-tolerant CIP therapies.

3.4 Other HaloTag ligands and their applications for pooled labeling

An expanding suite of functional HaloTag ligands stands poised for diverse high-throughput applications (Hoelzel and Zhang, 2020). Bifunctional molecules that recruit HaloTag to orthogonal ligand-binding domains such as FKBP, DHFR, or SNAP-tag (see Section 4 for discussion of other ligand-binding domains), can enable multiplexed control of protein-protein interactions, some of which can be triggered or reversed by light-activated chemical groups (Ballister et al., 2014; Zimmermann et al., 2014; Parvez et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2017). Moreover, targeted protein depletion can be achieved using HaloPROTACs recruiting VHL or CRBN E3 ligases, offering an acute protein depletion alternative to genomic- or transcript-based knockdown methods like CRISPR or RNAi and reducing the confounding effects of genetic adaptation (Buckley et al., 2015; Tovell et al., 2019; Ody et al., 2023). Conversely, ligands such as HALTS1 can stabilize HaloTag2-fused proteins, allowing bidirectional pharmacological control of protein levels (Figure 2D) (Neklesa et al., 2013). Additionally, environment-sensitive fluorophores permit real-time readouts of metabolites, ion concentrations, and protein folding states in living cells (Figure 2E) (Liu et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2020). Ligands fused to resins can be used to capture HaloTag-fused proteins of interest (Figure 2F). By combining these ligands with pooled HaloTag libraries and sequencing-based readouts, researchers gain the ability to probe myriad aspects of protein function and regulation systematically, from rapid degradation studies to detailed investigations of local chemical microenvironments.

3.5 Limitations for pooled ligand-binding assays

Despite the flexibility offered by HaloTag and other ligand-binding domains, several practical and conceptual limitations must be considered. First, ligands may have inconsistent labeling efficiencies when faced with targets expressed at varying levels and cellular environments. Furthermore, downstream effects of labeling can vary: in hydrophobic tagging applications, metastable fusion proteins may completely misfold, whereas more stable fusions may be less acutely affected. Bifunctional ligands designed for induced proximity can also miss certain protein-protein interactions if linker length and flexibility are not properly tuned. Additional concerns, like off-target binding and other ligand-specific considerations such as membrane permeability must be accounted for with different tag systems (see Section 4). Second, the gene tagging process itself can disrupt protein stability or function, particularly with larger tags, though this can be alleviated by testing multiple insertion sites per protein as part of the pooled tagging approach. In diploid cells, heterozygous integration is likely to occur depending on the tagging method used, which may complicate methods such as pooled degradation screens that would rely on perturbation of the entirety of a given protein. Finally, no single tagging platform suits all genes: intron-based methods fail when genes lack introns, while certain proteins cannot tolerate terminal tagging. While these issues do not negate the advantages of pooled ligand-binding assays, they highlight the importance of careful experimental design and follow-up validation.

4 Alternative domains and probes

A widely used strategy for visualizing and targeting specific proteins of interest (POIs) involves fusions with fluorescent or split fluorescent proteins (Feng et al., 2017; Romei and Boxer, 2019), affinity tags (Kimple et al., 2013), nanobodies (de Beer and Giepmans, 2020; Stevens et al., 2024), and degron tags (Natsume and Kanemaki, 2017). Recently, the use of ligand-binding domains has emerged as a “swiss army knife” approach for manipulating POIs (Table 1). By switching among different probes, one can readily repurpose a single domain for numerous applications such as fluorescent labeling, protein-protein interaction studies, stabilization or destabilization, targeted degradation, quantitative proteomics, purification, drug screening, biosensing, and scaffolding. Several alternatives orthogonal to the widely-used HaloTag have been developed over the years, each offering distinct advantages and drawbacks depending on the experimental context.

TABLE 1

| Tag | Size | Type of Ligand | Examples of common or pooled screening applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Small molecule-based probes | |||

| HaloTag2/HaloTag7 | 33 kDa | Chloroalkane derivatives | Imaging, protein interactions, degradation (Los et al., 2008; Serebrenik et al., 2024; Sansbury et al., 2025) |

| SNAP-tag/SNAP-tag2 | 20 kDa | Benzylguanine (BG) and benzylchloropyrimidine (CP) derivatives; Expanded pyrimidine derivatives (SNAP-tag2) | Imaging, pulldown assays, proximity labeling, degradation, protein interaction (Keppler et al., 2003; Dreyer et al., 2023; Kühn et al., 2024) |

| CLIP-tag | 20 kDa | O2-benzylcytosine (BC) derivatives | Dual labeling, co-localization studies (Gautier et al., 2008; Wilhelm et al., 2021) |

| eDHFR | 18 kDa | Trimethoprim (TMP) and Methotrexate (MTX) derivatives | Imaging, degradation, stabilization (Etersque et al., 2023; Mo et al., 2022) |

| BromoTag | 15 kDa | Diazepine-based derivatives | Induced degradation (Bond et al., 2021) |

| BromoCatch | 13 kDa | Diazepine-based derivatives with electrophilic warheads | Fluorescent labeling, biotin-based detection (Rodriguez-Rios et al., 2025) |

| β-lactamase | 29 kDa | β-lactam substrates; non-β-lactam β-lactamase inhibitors | Fluorescent labeling (Mizukami et al., 2009; Minoshima et al., 2023) |

| PYP-tag/Y-FAST | 14 kDa | 7-hydroxycoumarin-3-carboxylic acid derivatives (PYP); 4-hydroxybenzylidene-rhodanine derivatives (Y-FAST) | Live-cell imaging (Hori et al., 2009; Plamont et al., 2016) |

| ACP/MCP | 9 kDa | CoA derivatives: PPTase-labeled (ACP), SFP synthase-labeled (MCP) | Extracellular/Plasma membrane labeling, dual labeling (George et al., 2004) |

| cTag | 5.8 kDa | Benzolactam derivatives | Induced proximity, cell signaling (Vedagopuram et al., 2025) |

| mgTag | 4.3 kDa | PT-179 derivatives | Induced proximity, cell signaling (Vedagopuram et al., 2025) |

| LplA Acceptor Peptide | 13–22 aa | Lipoic acid and alkyl azide derivatives | Fluorescent labeling, biochemical assays (Fernández-Suárez et al., 2007; Puthenveetil et al., 2009; Yao et al., 2012) |

| Tetracysteine | 6 aa | FlAsH/ReAsH (organo-arsenicals) | Imaging with minimal steric interference (Griffin et al., 1998; Martin et al., 2005) |

| FKBP12 | 12 kDa | Rapamycin derivatives | Induced proximity, degradation, dimerization (Clackson et al., 1998; Kolos et al., 2018; Robers et al., 2009; Nabet et al., 2018) |

| Protein-associated probes | |||

| SpyTag/SpyCatcher | 13 aa (SpyTag); 15 kDa (SpyCatcher) | Protein-protein binding | Protein conjugation (Zakeri et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2020) |

| SnoopTag/SnoopCatcher | 12 aa (SnoopTag); 12 kDa (SnoopCatcher) | Protein-protein binding | Protein interaction studies (Veggiani et al., 2016) |

| ABI1/PYL | 33 kDa (ABI1); 20 kDa (PYL1) | Abscisic acid-based derivatives | Dimerization (Liang et al., 2011), Induced proximity (Poirson et al., 2024) |

| NanoBiT | 1.3 kDa (peptide); 18 kDa (polypeptide) | Peptide-protein binding | Quantitative luminescence assays (Dixon et al., 2016; Schwinn et al., 2018) |

| iLOV/LOV2 | 10 kDa (iLOV) −15 kDa | n/a | Optogenetics and light control of proteins (Chapman et al., 2008; Strickland et al., 2012) |

| ALFA/NbALFA | 15 aa (ALFA); 13 kDa (NbALFA) | ALFA‐tag specific nanobody (NbALFA) | High-affinity labeling (Götzke et al., 2019; Stevens et al., 2024) and induced proximity (Poirson et al., 2024) |

| eGFP/vhhGFP | 27 kDa (eGFP); 14 kDa (vhhGFP) | GFP-specific nanobody (vhhGFP) | Induced proximity (Poirson et al., 2024), high-affinity tagging (Stevens et al., 2024; Li et al., 2012) |

| Variable probes | |||

| Split inteins | Varies | n/a | Protein editing (Shah and Muir, 2014; David et al., 2015; Beyer et al., 2025) |

Summary of common protein tags amenable to pooled knock-in.

4.1 Small molecule–based probes

Domains for binding probes can be broadly categorized into self-labeling domains that directly form covalent bonds with their ligands, enzyme-mediated systems in which exogenous enzymes catalyze the bond formation, and non-covalent domains that rely on high-affinity binding rather than covalent linkage. Self-labeling protein (SLP) tags provide simple schemes that require only the tag and its cognate ligand. SNAP-tag is an SLP derived from human O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase (AGT) and binds covalently to O6-benzyl -guanine and -chloropyrimidine derivatives (Keppler et al., 2003; Corrêa et al., 2013). SNAP-tag is smaller (20 kDa) than HaloTag (33 kDa), making it less likely to interfere with the tagged protein. However, the SNAP-tag has slower labeling kinetics and some SNAP-tag ligands suffer from limited cell permeability, restricting its use in live-cell imaging (Dreyer et al., 2023). The engineered SNAP-tag2 improves labeling speed and fluorescence brightness and can be used in conjugation with pyrimidine-based substrates optimized for improved kinetics and cell permeability (Kühn et al., 2024). SNAP-tag has been used in many applications from targeted degradation to induction of protein-protein interactions (Kindermann et al., 2003; Bottanelli et al., 2016; Yu et al., 2019; McCutcheon et al., 2020; Dotson and Ngo, 2022; Pol et al., 2024; Seabrook et al., 2024). The CLIP-tag, also derived from AGT (Gautier et al., 2008) binds O2-benzylcytosine derivatives, enabling orthogonal labeling alongside SNAP-tag for co-localization studies (Wilhelm et al., 2021). Comparable in size to SNAP-tag, the 18 kDa Escherichia coli dihydrofolate reductase (eDHFR) binds trimethoprim (TMP)- and methotrexate-based ligands to allow bioorthogonal labeling in mammalian cells for applications from fluorescent imaging to degradation (Baker et al., 1981; Etersque et al., 2023; Rana et al., 2024). Further improvements to eDHFR TMP now allow for fast, covalent labeling (Chen et al., 2012; Mo et al., 2022). The BromoTag system is a 15 kDa inducible degron platform that employs a BRD4 bromodomain L387A variant tag to enable rapid target degradation via heterobifunctional bumped PROTACs (Bond et al., 2021). Complementing this, the 13 kDa SLP-based BromoCatch system utilizes a bromodomain-derived tag compatible with functionalized diazepine probes with an electrophilic group being developed for a wide range of applications, including protein-protein interaction assays, purification, targeted degradation, and live-cell fluorescence imaging (Rodriguez-Rios et al., 2025).

Additional self-labeling tags include the 29 kDa TEM-1 β-lactamase inhibitor-based tags (Mizukami et al., 2009; Minoshima et al., 2023), as well as the 14 kDa photoactive yellow protein PYP-tag (Hori et al., 2009) and its reversible derivative Y-FAST (Plamont et al., 2016). Among the smaller tags that covalently bind small molecules, ACP (Acyl Carrier Protein) and MCP (mutated ACP D36T/D39G), 9 and 8 kDa respectively, allow selective dual labeling on the cell surface using CoA derivatives with respective phosphopantetheinyl transferases (George et al., 2004). Two compact covalent tags, cTag (5.8 kDa) and mgTag (4.3 kDa), mediate group-transfer reactions with their respective ligands (Vedagopuram et al., 2025). cTag employs an engineered C1 domain containing a reactive cysteine residue, while mgTag features an engineered zinc-finger domain with a cysteine for reactivity. cTag specifically binds ligands bearing cysteine-reactive benzolactam scaffolds, whereas mgTag engages immunomodulatory drug (IMiD) derivatives, such as the molecular glue PT-179 (Mercer et al., 2024) modified with a group-transfer linker, in a cereblon-dependent manner.

A variety of short peptide tags exist that rely on exogenous delivery of an enzyme to catalyze covalent bond formation between the tag and its ligand; many of these tags are suitable only for cell surface labeling and have been reviewed elsewhere (Wolf et al., 2021). The Escherichia coli Lipoic Acid Ligase (LplA) Acceptor Peptides, as small as 13 amino acids, are notable for enabling specific intracellular protein tagging with a variety of probes (Fernández-Suárez et al., 2007; Puthenveetil et al., 2009; Yao et al., 2012); although the requirement of LplA to physically interact with its substrates may limit the compartments amenable for pooled protein tagging. In addition, a minimal six-amino acid tetracysteine motif binds FlAsH/ReAsH dyes for fluorescence imaging (Griffin et al., 1998) but its specificity is limited (Stroffekova et al., 2001). Optimized tetracysteine sequences with improved ligand affinity and fluorescence have since been developed (Martin et al., 2005).

Non-covalent small molecule interactions are exemplified by mutant forms of human FKBP12 (e.g., FKBPF36V, 12 kDa), which bind rapamycin-derived probes (Choi et al., 1996; Clackson et al., 1998). This system is routinely used for chemically induced proximity, targeted protein degradation, intracellular imaging, and more (Kohler and Bertozzi, 2003; Inoue et al., 2005; Banaszynski et al., 2006a; Banaszynski et al., 2006b; Robers et al., 2009; Kolos et al., 2018; Nabet et al., 2018; Du et al., 2023).

4.2 Protein-associated probes

Many fusion tags utilize peptide-based ligands or specifically bind other proteins which can be genetically encoded yet lack the chemical flexibility and minimal size of small molecule ligands. Nevertheless, these systems can still be functionalized with a variety of probes and delivered extracellularly. SpyTag/SpyCatcher, derived from the Streptococcus pyogenes CnaB2 domain of a fibronectin-binding protein, FbaB (Zakeri et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2020) and SnoopTag/SnoopCatcher, derived from a Streptococcus pneumoniae adhesin, RrgA (Veggiani et al., 2016) form spontaneous isopeptide bonds, creating robust covalent linkages used for protein conjugation with options for chemical diversification. Likewise, ABA-based PYR/PYL domains (Liang et al., 2011) enable ligand-dependent dimerization for induced proximity or degradation (Poirson et al., 2024; Han et al., 2025). NanoBiT (Dixon et al., 2016) and its variants (Schwinn et al., 2018) reconstitutes a split-luciferase signal, yielding sensitive, quantitative assays of protein interactions. For optogenetics, small flavin-binding domains iLOV/LOV2 (Chapman et al., 2008; Strickland et al., 2012) regulate protein function via light but demand specialized setups.

Nanobody-binding domains represent another large category of tags, with prominent examples including ALFA/NbALFA (Götzke et al., 2019) and eGFP/vhhGFP (Li et al., 2012) which exploit short peptide epitopes recognized by high-affinity nanobodies. These systems have been used for many applications from imaging to inducing protein-protein interactions, even in pooled systems (de Beer and Giepmans, 2020; Poirson et al., 2024; Stevens et al., 2024). Finally, split intein-based tags allow for specific and flexible protein editing through a covalent trans splicing reaction (Shah and Muir, 2014). Proteins can be tagged with split inteins terminally (David et al., 2015) or internally by using two orthogonal split intein pairs (Beyer et al., 2025). After splicing, inteins leave behind a minimal footprint (≤10 amino acids) defined by the intein-specific “extein” sequence along with a peptide tag of choice that can include non-canonical amino acids for compatibility with a wide variety of probes (Yi et al., 2024; Beyer et al., 2025).

4.3 Ideal next-generation domains and probes

Although existing ligand-binding domains offer an impressive array of functionalities, no single system perfectly satisfies all research needs. An ideal “next-generation” fusion domain for large-scale tagging approaches would have the following attributes: 1) orthogonal to endogenous cellular machinery, preventing unintended labeling, interactions, or interference; 2) monomeric with a minimal size and footprint to help preserve the proper fold, function, and binding interfaces of the fused protein; 3) high tag stability would further minimize perturbation of the structure of the protein it is fused to; 4) the tag would have a high-quality monoclonal antibody for orthogonal detection and biochemical isolation. On the ligand side, 5) a chemically versatile scaffold with rapid, high-affinity, and specific binding to ensure quantitative labeling; 6) such ligands should be easily customized for imaging, degradation, recruitment, or other modifications, and 7) would not require additional enzymes or components for binding. Such a tag system would be highly effective for proteome-scale pooled tag libraries.

5 Conclusions and perspectives

Pooled protein tagging with multifunctional ligand-binding domains has enabled new approaches for cell biology that combine chemical biology and functional genomics for high-throughput protein interrogation at both endogenous and exogenous expression levels. By coupling pooled tag libraries with specialized ligands ranging from fluorescent probes to bifunctional molecules, researchers can systematically investigate protein localization, stability, interactions, and more in diverse cell models. This convergence of technologies offers unique insights into proteostasis and disease mechanisms, laying the groundwork for next-generation therapeutic strategies, including those utilizing induced proximity.

Looking ahead, there remains ample opportunity to expand existing pooled tagging approaches into new disease contexts, such as cancer and neurodegeneration, to gain unique insights on the relevant protein dynamics, interactions, or responses to protein misfolding. Furthermore, exploring so-far untested domains and probes in a proteome-wide context will enable additional systematic insights into cellular environments. Finally, continued large-scale tagging efforts will iteratively pave the way for comprehensive proteome-wide libraries of high-fidelity fusions which can be utilized in subsequent tagging experiments. Incorporating multiple tag fusion variations for each protein will be especially valuable for protein–protein interaction studies, where proper alignment can make the difference between a fleeting contact and a functionally relevant complex. In tandem with the ongoing development of new domains and ligands, these integrative strategies promise to push the frontier of systematic studies of the proteome, bridging functional genomics and chemical biology and opening up exciting avenues for both fundamental discovery and translational research.

Statements

Author contributions

KL: Writing – review and editing, Writing – original draft. YS: Writing – review and editing, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by R00AG075256 from NIH/NIA, awarded to Y.V.S.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

AlerasoolN.LengH.LinZ.-Y.GingrasA.-C.TaipaleM. (2022). Identification and functional characterization of transcriptional activators in human cells. Mol. Cell82, 677–695.e7. 10.1016/j.molcel.2021.12.008

2

AnzaloneA. V.GaoX. D.PodrackyC. J.NelsonA. T.KoblanL. W.RaguramA.et al (2022). Programmable deletion, replacement, integration and inversion of large DNA sequences with twin prime editing. Nat. Biotechnol.40, 731–740. 10.1038/s41587-021-01133-w

3

BakerD. J.BeddellC. R.ChampnessJ. N.GoodfordP. J.NorringtonF. E.SmithD. R.et al (1981). The binding of trimethoprim to bacterial dihydrofolate reductase. FEBS Lett.126, 49–52. 10.1016/0014-5793(81)81030-7

4

BallisterE. R.AonbangkhenC.MayoA. M.LampsonM. A.ChenowethD. M. (2014). Localized light-induced protein dimerization in living cells using a photocaged dimerizer. Nat. Commun.5, 5475. 10.1038/ncomms6475

5

BanaszynskiL. A.ChenL.-C.Maynard-SmithL. A.OoiA. G. L.WandlessT. J. (2006a). A rapid, reversible, and tunable method to regulate protein function in living cells using synthetic small molecules. Cell126, 995–1004. 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.025

6

BanaszynskiL. A.LiuC. W.WandlessT. J. (2006b). Characterization of the FKBP·rapamycin·FRB ternary complex [J. am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 4715−4721]. J. Am. Chem. Soc.128, 15928. 10.1021/ja0699788

7

BeyerJ. N.SerebrenikY. V.ToyK.NajarM. A.FeiermanE.RaniszewskiN. R.et al (2025). Intracellular protein editing enables incorporation of noncanonical residues in endogenous proteins. Science388, eadr5499. 10.1126/science.adr5499

8

BondA. G.CraigonC.ChanK.-H.TestaA.KarapetsasA.FasimoyeR.et al (2021). Development of BromoTag: A “bump-and-hole”-PROTAC system to induce potent, rapid, and selective degradation of tagged target proteins. J. Med. Chem.64, 15477–15502.

9

BondesonD. P.MaresA.SmithI. E. D.KoE.CamposS.MiahA. H.et al (2015). Catalytic in vivo protein knockdown by small-molecule PROTACs. Nat. Chem. Biol.11, 611–617. 10.1038/nchembio.1858

10

BottanelliF.KromannE. B.AllgeyerE. S.ErdmannR. S.Wood BaguleyS.SirinakisG.et al (2016). Two-colour live-cell nanoscale imaging of intracellular targets. Nat. Commun.7, 10778. 10.1038/ncomms10778

11

BuckleyD. L.RainaK.DarricarrereN.HinesJ.GustafsonJ. L.SmithI. E.et al (2015). HaloPROTACS: use of small molecule PROTACs to induce degradation of HaloTag fusion proteins. ACS Chem. Biol.10, 1831–1837. 10.1021/acschembio.5b00442

12

BurslemG. M.CrewsC. M. (2020). Proteolysis-targeting chimeras as therapeutics and tools for biological discovery. Cell181, 102–114. 10.1016/j.cell.2019.11.031

13

CattoglioC.PustovaI.WaltherN.HoJ. J.Hantsche-GriningerM.InouyeC. J.et al (2019). Determining cellular CTCF and cohesin abundances to constrain 3D genome models. Elife8, e40164.

14

ChapmanS.FaulknerC.KaiserliE.Garcia-MataC.SavenkovE. I.RobertsA. G.et al (2008). The photoreversible fluorescent protein iLOV outperforms GFP as a reporter of plant virus infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.105, 20038–20043. 10.1073/pnas.0807551105

15

ChenZ.JingC.GallagherS. S.SheetzM. P.CornishV. W. (2012). Second-generation covalent TMP-tag for live cell imaging. J. Am. Chem. Soc.134, 13692–13699. 10.1021/ja303374p

16

ChoN. H.CheverallsK. C.BrunnerA.-D.KimK.MichaelisA. C.RaghavanP.et al (2022). OpenCell: endogenous tagging for the cartography of human cellular organization. Science375, eabi6983. 10.1126/science.abi6983

17

ChoiJ.ChenJ.SchreiberS. L.ClardyJ. (1996). Structure of the FKBP12-rapamycin complex interacting with the binding domain of human FRAP. Science273, 239–242. 10.1126/science.273.5272.239

18

ClacksonT.YangW.RozamusL. W.HatadaM.AmaraJ. F.RollinsC. T.et al (1998). Redesigning an FKBP-ligand interface to generate chemical dimerizers with novel specificity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.95, 10437–10442. 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10437

19

CohenA. A.Geva-ZatorskyN.EdenE.Frenkel-MorgensternM.IssaevaI.SigalA.et al (2008). Dynamic proteomics of individual cancer cells in response to a drug. Science322, 1511–1516. 10.1126/science.1160165

20

CorrêaI. R.JrBakerB.ZhangA.SunL.ProvostC. R.LukinavičiusG.et al (2013). Substrates for improved live-cell fluorescence labeling of SNAP-tag. Curr. Pharm. Des.19, 5414–5420. 10.2174/1381612811319300011

21

DavidY.Vila-PerellóM.VermaS.MuirT. W. (2015). Chemical tagging and customizing of cellular chromatin states using ultrafast trans-splicing inteins. Nat. Chem.7, 394–402. 10.1038/nchem.2224

22

de BeerM. A.GiepmansB. N. G. (2020). Nanobody-based probes for subcellular protein identification and visualization. Front. Cell. Neurosci.14, 573278. 10.3389/fncel.2020.573278

23

DelRossoN.TyckoJ.SuzukiP.AndrewsC.MukundA.LiongsonI.et al (2023). Large-scale mapping and mutagenesis of human transcriptional effector domains. Nature616, 365–372. 10.1038/s41586-023-05906-y

24

DixonA. S.SchwinnM. K.HallM. P.ZimmermanK.OttoP.LubbenT. H.et al (2016). NanoLuc complementation reporter optimized for accurate measurement of protein interactions in cells. ACS Chem. Biol.11, 400–408. 10.1021/acschembio.5b00753

25

DotsonH. L.NgoJ. T. (2022). SNAP-tag and HaloTag fused proteins for HaSX8-inducible control over synthetic biological functions in engineered mammalian cells. bioRxiv. 10.1101/2022.08.12.503781

26

DreyerR.PfukwaR.BarthS.HunterR.KlumpermanB. (2023). The evolution of SNAP-tag labels. Biomacromolecules24, 517–530. 10.1021/acs.biomac.2c01238

27

DuZ.WangW.LuoS.ZhangL.YuanS.HeiY.et al (2023). Self-renewable tag for photostable fluorescence imaging of proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc.145, 18968–18976. 10.1021/jacs.3c06102

28

EncellL. P.Friedman OhanaR.ZimmermanK.OttoP.VidugirisG.WoodM. G.et al (2012). Development of a dehalogenase-based protein fusion tag capable of rapid, selective and covalent attachment to customizable ligands. Curr. Chem. Genomics6, 55–71. 10.2174/1875397301206010055

29

EnglandC. G.LuoH.CaiW. (2015). HaloTag technology: a versatile platform for biomedical applications. Bioconjug. Chem.26, 975–986. 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.5b00191

30

EtersqueJ. M.LeeI. K.SharmaN.XuK.RuffA.NorthrupJ. D.et al (2023). Regulation of eDHFR-tagged proteins with trimethoprim PROTACs. Nat. Commun.14, 7071. 10.1038/s41467-023-42820-3

31

FeldmanD.SinghA.Schmid-BurgkJ. L.CarlsonR. J.MezgerA.GarrityA. J.et al (2019). Optical pooled screens in human cells. Cell179, 787–799.e17. 10.1016/j.cell.2019.09.016

32

FengS.SekineS.PessinoV.LiH.LeonettiM. D.HuangB. (2017). Improved split fluorescent proteins for endogenous protein labeling. Nat. Commun.8, 370. 10.1038/s41467-017-00494-8

33

Fernández-SuárezM.BaruahH.Martínez-HernándezL.XieK. T.BaskinJ. M.BertozziC. R.et al (2007). Redirecting lipoic acid ligase for cell surface protein labeling with small-molecule probes. Nat. Biotechnol.25, 1483–1487. 10.1038/nbt1355

34

GautierA.JuilleratA.HeinisC.CorrêaI. R.JrKindermannM.BeaufilsF.et al (2008). An engineered protein tag for multiprotein labeling in living cells. Chem. Biol.15, 128–136. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2008.01.007

35

GeorgeN.PickH.VogelH.JohnssonN.JohnssonK. (2004). Specific labeling of cell surface proteins with chemically diverse compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc.126, 8896–8897. 10.1021/ja048396s

36

GötzkeH.KilischM.Martínez-CarranzaM.Sograte-IdrissiS.RajavelA.SchlichthaerleT.et al (2019). The ALFA-tag is a highly versatile tool for nanobody-based bioscience applications. Nat. Commun.10, 4403. 10.1038/s41467-019-12301-7

37

GriffinB. A.AdamsS. R.TsienR. Y. (1998). Specific covalent labeling of recombinant protein molecules inside live cells. Science281, 269–272. 10.1126/science.281.5374.269

38

GrimmJ. B.EnglishB. P.ChenJ.SlaughterJ. P.ZhangZ.RevyakinA.et al (2015). A general method to improve fluorophores for live-cell and single-molecule microscopy. Nat. Methods12 (244–50), 244–250. 10.1038/nmeth.3256

39

HanM.FuM. L.ZhuY.ChoiA. A.LiE.BezneyJ.et al (2025). Programmable control of spatial transcriptome in live cells and neurons. Nature, 1–11. 10.1038/s41586-025-09020-z

40

HanzlA.CasementR.ImrichovaH.HughesS. J.BaroneE.TestaA.et al (2023). Functional E3 ligase hotspots and resistance mechanisms to small-molecule degraders. Nat. Chem. Biol.19, 323–333. 10.1038/s41589-022-01177-2

41

HellerschmiedD.SerebrenikY. V.ShaoL.BurslemG. M.CrewsC. M. (2019). Protein folding state-dependent sorting at the Golgi apparatus. Mol. Biol. Cell30, 2296–2308. 10.1091/mbc.E19-01-0069

42

HoelzelC. A.ZhangX. (2020). Visualizing and manipulating biological processes by using HaloTag and SNAP-tag technologies. Chembiochem21, 1935–1946. 10.1002/cbic.202000037

43

HoriY.UenoH.MizukamiS.KikuchiK. (2009). Photoactive yellow protein-based protein labeling system with turn-on fluorescence intensity. J. Am. Chem. Soc.131, 16610–16611. 10.1021/ja904800k

44

HuppertzM. C.WilhelmJ.GrenierV.SchneiderM. W.FaltT.PorzbergN.et al (2024). Recording physiological history of cells with chemical labeling. Science383 (6685), 890–897. 10.1126/science.adg0812

45

InoueT.HeoW. D.GrimleyJ. S.WandlessT. J.MeyerT. (2005). An inducible translocation strategy to rapidly activate and inhibit small GTPase signaling pathways. Nat. Methods2, 415–418. 10.1038/nmeth763

46

JarvikJ. W.AdlerS. A.TelmerC. A.SubramaniamV.LopezA. J. (1996). CD-tagging: a new approach to gene and protein discovery and analysis. Biotechniques20, 896–904. 10.2144/96205rr03

47

JarvikJ. W.FisherG. W.ShiC.HennenL.HauserC.AdlerS.et al (2002). In vivo functional proteomics: mammalian genome annotation using CD-tagging. Biotechniques33 (852–4), 852–856. 10.2144/02334rr02

48

JevtićP.HaakonsenD. L.RapéM. (2021). An E3 ligase guide to the galaxy of small-molecule-induced protein degradation. Cell Chem. Biol.28, 1000–1013. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2021.04.002

49

KahnwaldM.MählenM.OostK. C.LiberaliP. (2024). Advances in optical pooled screening to map spatial complexity. Nat. Biotechnol., 1–3. 10.1038/s41587-024-02434-6

50

KepplerA.GendreizigS.GronemeyerT.PickH.VogelH.JohnssonK. (2003). A general method for the covalent labeling of fusion proteins with small molecules in vivo. Nat. Biotechnol.21, 86–89. 10.1038/nbt765

51

KimJ.KratzA. F.ChenS.ShengJ.KimH. K.ZhangL.et al (2024). High-throughput tagging of endogenous loci for rapid characterization of protein function. Sci. Adv.10, eadg8771. 10.1126/sciadv.adg8771

52

KimpleM. E.BrillA. L.PaskerR. L. (2013). Overview of affinity tags for protein purification. Curr. Protoc. Protein Sci.73, 9.9.1–9.9.23. 10.1002/0471140864.ps0909s73

53

KindermannM.GeorgeN.JohnssonN.JohnssonK. (2003). Covalent and selective immobilization of fusion proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc.125, 7810–7811. 10.1021/ja034145s

54

KohlerJ. J.BertozziC. R. (2003). Regulating cell surface glycosylation by small molecule control of enzyme localization. Chem. Biol.10, 1303–1311. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2003.11.018

55

KolosJ. M.VollA. M.BauderM.HauschF. (2018). FKBP ligands-where we are and where to go?Front. Pharmacol.9, 1425. 10.3389/fphar.2018.01425

56

KühnS.NasufovicV.WilhelmJ.KompaJ.de LangeE. M. F.LinY.-H.et al (2024). SNAP-tag2: faster and brighter protein labeling. bioRxiv. 10.1101/2024.08.28.610127

57

KurimchakA. M.Herrera-MontávezC.Montserrat-SangràS.Araiza-OliveraD.HuJ.Neumann-DomerR.et al (2022). The drug efflux pump MDR1 promotes intrinsic and acquired resistance to PROTACs in cancer cells. Sci. Signal.15, eabn2707. 10.1126/scisignal.abn2707

58

LacknerD. H.CarréA.GuzzardoP. M.BanningC.MangenaR.HenleyT.et al (2015). A generic strategy for CRISPR-Cas9-mediated gene tagging. Nat. Commun.6, 10237. 10.1038/ncomms10237

59

LacosteJ.HaghighiM.HaiderS.RenoC.LinZ.-Y.SegalD.et al (2024). Pervasive mislocalization of pathogenic coding variants underlying human disorders. Cell187, 6725–6741.e13. 10.1016/j.cell.2024.09.003

60

LayerJ. H.ChristyM.PlacekL.UnutmazD.GuoY.DavéU. P.et al (2020). LDB1 enforces stability on direct and indirect oncoprotein partners in leukemia. Mol. Cell. Biol.40, 1–28.

61

LiT.BourgeoisJ.-P.CelliS.GlacialF.Le SourdA.-M.MecheriS.et al (2012). Cell-penetrating anti-GFAP VHH and corresponding fluorescent fusion protein VHH-GFP spontaneously cross the blood-brain barrier and specifically recognize astrocytes: application to brain imaging. FASEB J.26, 3969–3979. 10.1096/fj.11-201384

62

LiangF.-S.HoW. Q.CrabtreeG. R. (2011). Engineering the ABA plant stress pathway for regulation of induced proximity. Sci. Signal.4, rs2. 10.1126/scisignal.2001449

63

LiuY.MiaoK.LiY.FaresM.ChenS.ZhangX. (2018). A HaloTag-based multicolor fluorogenic sensor visualizes and quantifies proteome stress in live cells using solvatochromic and molecular rotor-based fluorophores. Biochemistry57, 4663–4674. 10.1021/acs.biochem.8b00135

64

LosG. V.EncellL. P.McDougallM. G.HartzellD. D.KarassinaN.ZimprichC.et al (2008). HaloTag: a novel protein labeling technology for cell imaging and protein analysis. ACS Chem. Biol.3, 373–382. 10.1021/cb800025k

65

MartinB. R.GiepmansB. N. G.AdamsS. R.TsienR. Y. (2005). Mammalian cell-based optimization of the biarsenical-binding tetracysteine motif for improved fluorescence and affinity. Nat. Biotechnol.23, 1308–1314. 10.1038/nbt1136

66

McCutcheonD. C.LeeG.CarlosA.MontgomeryJ. E.MoelleringR. E. (2020). Photoproximity profiling of protein-protein interactions in cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc.142, 146–153. 10.1021/jacs.9b06528

67

MercerJ. A. M.DeCarloS. J.Roy BurmanS. S.SreekanthV.NelsonA. T.HunkelerM.et al (2024). Continuous evolution of compact protein degradation tags regulated by selective molecular glues. Science383, eadk4422. 10.1126/science.adk4422

68

MinoshimaM.UmenoT.KadookaK.RouxM.YamadaN.KikuchiK. (2023). Development of a versatile protein labeling tool for live-cell imaging using fluorescent ß-lactamase inhibitors. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl.62, e202301704. 10.1002/anie.202301704

69

MizukamiS.WatanabeS.HoriY.KikuchiK. (2009). Covalent protein labeling based on noncatalytic beta-lactamase and a designed FRET substrate. J. Am. Chem. Soc.131, 5016–5017. 10.1021/ja8082285

70

MoJ.ChenJ.ShiY.SunJ.WuY.LiuT.et al (2022). Third-generation covalent TMP-tag for fast labeling and multiplexed imaging of cellular proteins. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl.61, e202207905. 10.1002/anie.202207905

71

MoonH. C.HerschlM. H.PawlukA.KonermannS.HsuP. D. (2024). A combinatorial domain screening platform reveals epigenetic effector interactions for transcriptional perturbation. bioRxiv. 10.1101/2024.10.28.620683

72

NabetB.RobertsJ. M.BuckleyD. L.PaulkJ.DastjerdiS.YangA.et al (2018). The dTAG system for immediate and target-specific protein degradation. Nat. Chem. Biol.14, 431–441. 10.1038/s41589-018-0021-8

73

NatsumeT.KanemakiM. T. (2017). Conditional degrons for controlling protein expression at the protein level. Annu. Rev. Genet.51, 83–102.

74

NeklesaT. K.NoblinD. J.KuzinA. P.LewS.SeetharamanJ.ActonT. B.et al (2013). A bidirectional system for the dynamic small molecule control of intracellular fusion proteins. ACS Chem. Biol.8, 2293–2300. 10.1021/cb400569k

75

NeklesaT. K.TaeH. S.SchneeklothA. R.StulbergM. J.CorsonT. W.SundbergT. B.et al (2011). Small-molecule hydrophobic tagging-induced degradation of HaloTag fusion proteins. Nat. Chem. Biol.7, 538–543. 10.1038/nchembio.597

76

NemčkoF.HimmelsbachM.LoubiereV.YelagandulaR.PaganiM.FaschingN.et al (2024). Proteome-scale tagging and functional screening in mammalian cells by ORFtag. Nat. Methods21, 1668–1673. 10.1038/s41592-024-02339-x

77

OdyB. K.ZhangJ.NelsonS. E.XieY.LiuR.DoddC. J.et al (2023). Synthesis and evaluation of cereblon-recruiting HaloPROTACs. Chembiochem24, e202300498. 10.1002/cbic.202300498

78

ORFeome Collaboration (2016). The ORFeome Collaboration: a genome-scale human ORF-clone resource. Nat. Methods13, 191–192. 10.1038/nmeth.3776

79

OttisP.PalladinoC.ThiengerP.BritschgiA.HeichingerC.BerreraM.et al (2019). Cellular resistance mechanisms to targeted protein degradation converge toward impairment of the engaged ubiquitin transfer pathway. ACS Chem. Biol.14, 2215–2223. 10.1021/acschembio.9b00525

80

PandeyS.GaoX. D.KrasnowN. A.McElroyA.TaoY. A.DubyJ. E.et al (2025). Efficient site-specific integration of large genes in mammalian cells via continuously evolved recombinases and prime editing. Nat. Biomed. Eng.9, 22–39. 10.1038/s41551-024-01227-1

81

ParvezS.LongM. J. C.LinH.-Y.ZhaoY.HaegeleJ. A.PhamV. N.et al (2016). T-REX on-demand redox targeting in live cells. Nat. Protoc.11, 2328–2356. 10.1038/nprot.2016.114

82

PlamontM.-A.Billon-DenisE.MaurinS.GauronC.PimentaF. M.SpechtC. G.et al (2016). Small fluorescence-activating and absorption-shifting tag for tunable protein imaging in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.113, 497–502. 10.1073/pnas.1513094113

83

PoirsonJ.ChoH.DhillonA.HaiderS.ImritA. Z.LamM. H. Y.et al (2024). Proteome-scale discovery of protein degradation and stabilization effectors. Nature628, 878–886. 10.1038/s41586-024-07224-3

84

PolS. A.LiljenbergS.BarrJ.SimonG.Wong-DilworthL.PatersonD. L.et al (2024). Induced degradation of SNAP-fusion proteins. RSC Chem. Biol.5, 1232–1247. 10.1039/d4cb00184b

85

PuthenveetilS.LiuD. S.WhiteK. A.ThompsonS.TingA. Y. (2009). Yeast display evolution of a kinetically efficient 13-amino acid substrate for lipoic acid ligase. J. Am. Chem. Soc.131, 16430–16438. 10.1021/ja904596f

86

RainaK.NoblinD. J.SerebrenikY. V.AdamsA.ZhaoC.CrewsC. M. (2014). Targeted protein destabilization reveals an estrogen-mediated ER stress response. Nat. Chem. Biol.10, 957–962. 10.1038/nchembio.1638

87

RanaS.DranchakP.DahlinJ. L.LamyL.LiW.OliphantE.et al (2024). Methotrexate-based PROTACs as DHFR-specific chemical probes. Cell Chem. Biol.31, 221–233.e14. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2023.09.014

88

ReicherA.KorenA.KubicekS. (2020). Pooled protein tagging, cellular imaging, and in situ sequencing for monitoring drug action in real time. Genome Res.30, 1846–1855. 10.1101/gr.261503.120

89

ReicherA.ReinišJ.CiobanuM.RůžičkaP.MalikM.SiklosM.et al (2024). Pooled multicolour tagging for visualizing subcellular protein dynamics. Nat. Cell Biol.26, 745–756. 10.1038/s41556-024-01407-w

90

RobersM.PinsonP.LeongL.BatchelorR. H.GeeK. R.MachleidtT. (2009). Fluorescent labeling of proteins in living cells using the FKBP12 (F36V) tag. Cytom. A75, 207–224. 10.1002/cyto.a.20649

91

Rodriguez-RiosM.CraigonC. G.NakasoneM. A.BondA. G.DorwardM.EdmondsA. K.et al (2025). BromoCatch: a self-labelling tag platform for protein analysis and live cell imaging. bioRxiv, 647551. 10.1101/2025.04.07.647551

92

RomeiM. G.BoxerS. G. (2019). Split green fluorescent proteins: scope, limitations, and outlook. Annu. Rev. Biophys.48, 19–44. 10.1146/annurev-biophys-051013-022846

93

SanchezH. M.LapidotT.ShalemO. (2024). High-throughput optimized prime editing mediated endogenous protein tagging for pooled imaging of protein localization. bioRxiv, 2024.09.16.613361. 10.1101/2024.09.16.613361

94

SansburyS. E.SerebrenikY. V.LapidotT.SmithD. G.BurslemG. M.ShalemO. (2025). Pooled tagging and hydrophobic targeting of endogenous proteins for unbiased mapping of unfolded protein responses. Mol. Cell85, 1868–1886.e12. 10.1016/j.molcel.2025.04.002

95

Schmid-BurgkJ. L.HöningK.EbertT. S.HornungV. (2016). CRISPaint allows modular base-specific gene tagging using a ligase-4-dependent mechanism. Nat. Commun.7, 12338. 10.1038/ncomms12338

96

SchwinnM. K.MachleidtT.ZimmermanK.EggersC. T.DixonA. S.HurstR.et al (2018). CRISPR-mediated tagging of endogenous proteins with a luminescent peptide. ACS Chem. Biol.13, 467–474. 10.1021/acschembio.7b00549

97

SeabrookL. J.FrancoC. N.LoyC. A.OsmanJ.FredlenderC.ZimakJ.et al (2024). Methylarginine targeting chimeras for lysosomal degradation of intracellular proteins. Nat. Chem. Biol.20, 1566–1576. 10.1038/s41589-024-01741-y

98

SerebrenikY. V.HellerschmiedD.ToureM.López-GiráldezF.BrooknerD.CrewsC. M. (2018). Targeted protein unfolding uncovers a Golgi-specific transcriptional stress response. Mol. Biol. Cell29, 1284–1298. 10.1091/mbc.E17-11-0693

99

SerebrenikY. V.ManiD.MaujeanT.BurslemG. M.ShalemO. (2024). Pooled endogenous protein tagging and recruitment for systematic profiling of protein function. Cell Genom4, 100651. 10.1016/j.xgen.2024.100651

100

SerebrenikY. V.SansburyS. E.KumarS. S.Henao-MejiaJ.ShalemO. (2019). Efficient and flexible tagging of endogenous genes by homology-independent intron targeting. Genome Res.29, 1322–1328. 10.1101/gr.246413.118

101

ShahN. H.MuirT. W. (2014). Inteins: nature’s gift to protein chemists. Chem. Sci.5, 446–461. 10.1039/C3SC52951G

102

SigalA.MiloR.CohenA.Geva-ZatorskyN.KleinY.AlalufI.et al (2006a). Dynamic proteomics in individual human cells uncovers widespread cell-cycle dependence of nuclear proteins. Nat. Methods3, 525–531. 10.1038/nmeth892

103

SigalA.MiloR.CohenA.Geva-ZatorskyN.KleinY.LironY.et al (2006b). Variability and memory of protein levels in human cells. Nature444, 643–646. 10.1038/nature05316

104

StevensT. A.TomaleriG. P.HazuM.WeiS.NguyenV. N.DeKalbC.et al (2024). A nanobody-based strategy for rapid and scalable purification of human protein complexes. Nat. Protoc.19, 127–158. 10.1038/s41596-023-00904-w

105

StricklandD.LinY.WagnerE.HopeC. M.ZaynerJ.AntoniouC.et al (2012). TULIPs: tunable, light-controlled interacting protein tags for cell biology. Nat. Methods9, 379–384. 10.1038/nmeth.1904

106

StroffekovaK.ProenzaC.BeamK. G. (2001). The protein-labeling reagent FLASH-EDT2 binds not only to CCXXCC motifs but also non-specifically to endogenous cysteine-rich proteins. Pflugers Arch.442, 859–866. 10.1007/s004240100619

107

SuzukiK.TsunekawaY.Hernandez-BenitezR.WuJ.ZhuJ.KimE. J.et al (2016). In vivo genome editing via CRISPR/Cas9 mediated homology-independent targeted integration. Nature540, 144–149. 10.1038/nature20565

108

TaeH. S.SundbergT. B.NeklesaT. K.NoblinD. J.GustafsonJ. L.RothA. G.et al (2012). Identification of hydrophobic tags for the degradation of stabilized proteins. Chembiochem13, 538–541. 10.1002/cbic.201100793

109

TovellH.TestaA.ManiaciC.ZhouH.PrescottA. R.MacartneyT.et al (2019). Rapid and reversible knockdown of endogenously tagged endosomal proteins via an optimized HaloPROTAC degrader. ACS Chem. Biol.14, 882–892. 10.1021/acschembio.8b01016

110

TyckoJ.DelRossoN.HessG. T.BanerjeeA.MukundA.VanM. V.et al (2020). High-throughput discovery and characterization of human transcriptional effectors. Cell183, 2020–2035. 10.1016/j.cell.2020.11.024

111

TyckoJ.VanM. V.DelRossoN.YeH.YaoD.ValbuenaR.et al (2024). Development of compact transcriptional effectors using high-throughput measurements in diverse contexts. Nat. Biotechnol., 1–14. 10.1038/s41587-024-02442-6

112

VeggianiG.NakamuraT.BrennerM. D.GayetR. V.YanJ.RobinsonC. V.et al (2016). Programmable polyproteams built using twin peptide superglues. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.113, 1202–1207. 10.1073/pnas.1519214113

113

VedagopuramS.SindiS. H.ChaudharyS. K.PerguR.SinghP.KarajE.et al (2025). Ultrasmall chemogenetic tags with group-transfer ligands. bioRxiv, 653252. 10.1101/2025.05.10.653252

114

WangL.HiblotJ.PoppC.XueL.JohnssonK. (2020). Environmentally sensitive color-shifting fluorophores for bioimaging. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl.59, 21880–21884. 10.1002/anie.202008357

115

WilhelmJ.KühnS.TarnawskiM.GotthardG.TünnermannJ.TänzerT.et al (2021). Kinetic and structural characterization of the self-labeling protein tags HaloTag7, SNAP-tag, and CLIP-tag. Biochemistry60, 2560–2575. 10.1021/acs.biochem.1c00258

116

WilsonC. M.PommierG. C.RichmanD. D.SamboldN.HussmannJ. A.WeissmanJ. S.et al (2024). Combinatorial effector targeting (COMET) for transcriptional modulation and locus-specific biochemistry. bioRxiv, 2024.10.28.620517. 10.1101/2024.10.28.620517

117

WinterG. E.BuckleyD. L.PaulkJ.RobertsJ. M.SouzaA.Dhe-PaganonS.et al (2015). DRUG DEVELOPMENT. Phthalimide conjugation as a strategy for in vivo target protein degradation. Science348, 1376–1381. 10.1126/science.aab1433

118

WolfP.GavinsG.Beck-SickingerA. G.SeitzO. (2021). Strategies for site-specific labeling of receptor proteins on the surfaces of living cells by using genetically encoded peptide tags. Chembiochem22, 1717–1732. 10.1002/cbic.202000797

119

YangX.BoehmJ. S.YangX.Salehi-AshtianiK.HaoT.ShenY.et al (2011). A public genome-scale lentiviral expression library of human ORFs. Nat. Methods8, 659–661. 10.1038/nmeth.1638

120

YaoJ. Z.UttamapinantC.PoloukhtineA.BaskinJ. M.CodelliJ. A.SlettenE. M.et al (2012). Fluorophore targeting to cellular proteins via enzyme-mediated azide ligation and strain-promoted cycloaddition. J. Am. Chem. Soc.134, 3720–3728. 10.1021/ja208090p

121

YarnallM. T. N.IoannidiE. I.Schmitt-UlmsC.KrajeskiR. N.LimJ.VilligerL.et al (2023). Drag-and-drop genome insertion of large sequences without double-strand DNA cleavage using CRISPR-directed integrases. Nat. Biotechnol.41, 500–512. 10.1038/s41587-022-01527-4

122

YenH.-C. S.XuQ.ChouD. M.ZhaoZ.ElledgeS. J. (2008). Global protein stability profiling in mammalian cells. Science322, 918–923. 10.1126/science.1160489

123

YiH. B.LeeS.SeoK.KimH.KimM.LeeH. S. (2024). Cellular and biophysical applications of genetic code expansion. Chem. Rev.124, 7465–7530. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.4c00112

124

YuQ.PourmandiN.XueL.GondrandC.FabritzS.BardyD.et al (2019). A biosensor for measuring NAD+ levels at the point of care. Nat. Metab.1, 1219–1225. 10.1038/s42255-019-0151-7

125

ZakeriB.FiererJ. O.CelikE.ChittockE. C.Schwarz-LinekU.MoyV. T.et al (2012). Peptide tag forming a rapid covalent bond to a protein, through engineering a bacterial adhesin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.109, E690–E697. 10.1073/pnas.1115485109

126

ZhangH.AonbangkhenC.TarasovetcE. V.BallisterE. R.ChenowethD. M.LampsonM. A. (2017). Optogenetic control of kinetochore function. Nat. Chem. Biol.13, 1096–1101. 10.1038/nchembio.2456

127

ZhangL.Riley-GillisB.VijayP.ShenY. (2019). Acquired resistance to BET-PROTACs (proteolysis-targeting chimeras) caused by genomic alterations in core components of E3 ligase complexes. Mol. Cancer Ther.18, 1302–1311. 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-18-1129

128

ZhangY.SohnC.LeeS.AhnH.SeoJ.CaoJ.et al (2020). Detecting protein and post-translational modifications in single cells with iDentification and qUantification sEparaTion (DUET). Commun. Biol.3, 420. 10.1038/s42003-020-01132-8

129

ZimmermannM.CalR.JanettE.HoffmannV.BochetC. G.ConstableE.et al (2014). Cell-permeant and photocleavable chemical inducer of dimerization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl.53, 4717–4720. 10.1002/anie.201310969

Summary

Keywords

pooled protein tagging, SPOTLITES, HaloTag, induced proximity, hydrophobic tagging, protein degradation, CRISPR knock-in

Citation

Larrimore KE and Serebrenik YV (2025) Utilizing small molecules to probe and harness the proteome by pooled protein tagging with ligandable domains. Front. Pharmacol. 16:1593844. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2025.1593844

Received

14 March 2025

Accepted

03 June 2025

Published

23 June 2025

Volume

16 - 2025

Edited by

Madhu Sudhan Ravindran, Bristol Myers Squibb, United States

Reviewed by

Bingbing Li, Oregon Health and Science University, United States

Utpal P. Davé, Indiana University Bloomington, United States

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Larrimore and Serebrenik.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yevgeniy V. Serebrenik, yevgeniy.serebrenik@rutgers.edu

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.