Abstract

6-Nitrodopamine (6-ND) has potent positive chronotropic and inotropic effects. At a very low dose, i.e., 10 fM, it causes potentiation of the positive chronotropic effects induced by catecholamines in the rat atria, indicating a distinct mechanism of action. Cyclase-associated proteins (CAP-1 and CAP-2) are potential receptors for 6-ND in human cardiomyocytes. Since cyclic 3′,5′-cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) plays a fundamental role in the positive inotropic effects of classical catecholamines, it was further investigated whether 6-ND potentiates the positive inotropic effects induced by classical catecholamines in the rat isolated perfused heart. Human-induced pluripotent stem cell (hiPSC)-derived cardiomyocytes were harvested and lysed, and following appropriate separation procedures, membrane proteins were incubated with 6-ND-derivatized agarose, centrifuged, and the proteins retained in the agarose eluted with 6-ND (1 mM). The proteins isolated from the chemical pulldown assay were fractionated by SDS-PAGE, the bands were cut and hydrolyzed in situ with trypsin, and then separated and sequenced. A total of 817 proteins were generated, and following screening using UniProt “Retrieve/ID Mapping” function and Gene Ontology cellular component category, 124 proteins were identified as membrane proteins. These experiments identified three proteins that modulate adenylyl cyclase (AC) activity (CAP-1, CAP-2, and STIM1), which are compatible with the pharmacological findings reported for 6-ND in the rat heart. As expected, 6-ND strongly potentiates the inotropic effect induced by noradrenaline in Langendorff’s preparation. In conclusion, 6-ND-induced potentiation of catecholamine-induced chronotropic and inotropic effects is due to the modulation of adenylyl cyclase activity, probably via direct interactions with CAP-1 and CAP-2.

1 Introduction

6-Nitrodopamine (6-ND) is a novel endogenous catecholamine that exerts potent and long-lasting positive chronotropic and inotropic responses in the isolated rat heart (Britto-Júnior et al., 2022; 2023a; Zatz and De Nucci, 2024). In rat isolated right atria, 6-ND at a concentration as low as 10 fM markedly potentiates the positive chronotropic effects induced by the classical catecholamines dopamine, noradrenaline, and adrenaline (Britto-Júnior et al., 2023b). Interestingly, the low concentration (100 nM) of selective β1-adrenoceptor antagonists atenolol, betaxolol, and metoprolol significantly reduced both basal atrial rates and 6-ND-induced positive chronotropism (Britto-Júnior et al., 2022). This result implies that these drugs act as 6-ND receptor antagonists (Britto-Júnior et al., 2023b). More recently, 4-nitropropanolol (Sparaco et al., 2022) has been identified as a more selective 6-ND receptor antagonist in the rat isolated right atrium (Oliveira et al., 2024b); however, the receptor of 6-ND is yet to be identified.

Human-induced pluripotent stem cell (hiPSC)-derived cardiomyocytes (Di Baldassarre et al., 2018) reproduce the molecular mechanisms involved in heart disorders such as long QT syndrome (Keller et al., 2005), catecholamine polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (Itzhaki et al., 2012), and Brugada syndrome (Davis et al., 2012), thus offering a suitable translational model for investigating the expression of 6-ND receptors. Therefore, we employed hiPSC-derived cardiomyocytes to explore the potential targets for 6-ND, using a chemical pulldown approach, in which 6-ND was immobilized on agarose beads and incubated with cardiomyocyte membrane extracts. The purified proteins were then fractionated by SDS-PAGE; the bands were cut and hydrolyzed with trypsin, and the peptide mixtures were separated through UPLC and analyzed using mass spectrometry. Protein identification was carried out using the MaxQuant search-engine to query the UniProt Homo Sapiens database. In the competitive assay, 4-nitropropranolol, here referred to as a selective 6-ND antagonist, was added to the protein extract, and the proteins retained on the beads were subtracted from that obtained in the absence of 4-nitropropranolol. Three proteins that modulate the adenylyl cyclase (AC) activity were identified. Because cyclic 3′,5′-cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) plays a fundamental role in the positive inotropic effects of classical catecholamines (Guellich et al., 2014), we demonstrated the synergistic effects of 6-ND with noradrenaline on the positive inotropic response by using the Langendorff isolated heart perfusion model.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Chemical pulldown assay and protein separation

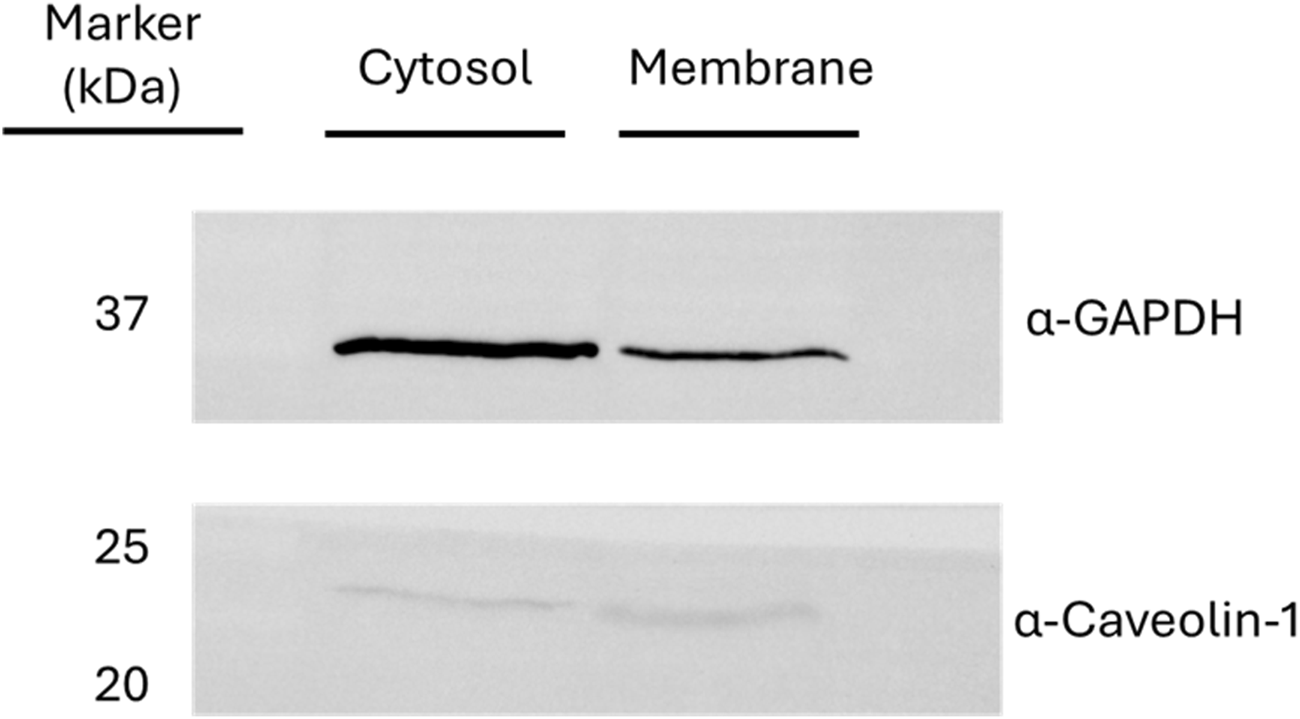

Actively beating hiPSC-derived cardiomyocytes (iPS-DF19-9-7T, WiCell Research Institute, Madison, Unites States) were harvested and lysed with a specific membrane protein enrichment protocol. Cardiomyocytes were treated using a Mem-PER™ Plus Membrane Protein Extraction kit (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, United States), according to the manufacturer’s protocol to enrich the protein membrane protein extract. In brief, 50 × 106 cardiomyocytes were added to 7.5 mL of permeabilization buffer, vortexed, and incubated for 10 min at 4°C with constant mixing. The supernatant, comprising cytosolic proteins, was collected by centrifuging for 15 min at 21,000 g. Solubilization buffer (5 mL) was added to the pellet, vortexed, and incubated for 30 min at 4°C with constant mixing. The supernatant, comprising the membrane proteins, was collected by centrifugation for 15 min at 21,000 g. The quantification of the extracted proteins was performed using the Pierce 660 nm assay (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, United States). The efficiency of the fractionation procedure was analyzed by Western blot assays, monitoring specific markers for each cell compartment (GAPDH for cytosol and caveolin-1 for membrane) with specific antibodies (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1

SDS-PAGE of proteins eluted from the chemical pulldown (lane PD) and from the pre-clearing (lane PC). The molecular weight markers are also reported.

2.2 Chemical pulldown assay

For the pre-clearing step, 1.5 mg of the membrane extract was incubated (2 h) with 200 μL of naked PureCube Carboxy Agarose beads (Cube Biotech, Monheim, Germany) at 4°C to adsorb the protein background. The beads were centrifuged at 240 g for 2 min, and the supernatant was collected and then incubated with 200 μL of the resin derivatized with 6-ND overnight at 4°C. The naked agarose was washed with membrane extract buffer provided by the Mem-PER™ kit, and the proteins retained on the naked agarose were eluted with a solution of 1 mM of 6-ND. The eluted proteins were fractionated by SDS-PAGE. The gel was stained with GelCode™ Blue Safe Protein Stain (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States) and destained with Milli-Q water (PC lane in Figure 2).

FIGURE 2

Western blot assays for the verification of the fractionated lysis. The presence of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and caveolin-1 was monitored as markers of cytosolic and membrane fraction, respectively.

The supernatant was incubated overnight with the 6-ND-derivatized agarose and then centrifuged, and the pellet was washed with membrane extract buffer provided by the Mem-PER™ kit. The proteins retained on the 6-ND-derivatized agarose were eluted with a solution of 1 mM of 6-ND (PD lane in Figure 2).

In the competitive assay, 1 mM of 4-nitropropanolol was added to the membrane protein extract collected after the 6-ND pulldown assay and then incubated with the resin derivatized with 6-ND overnight at 4°C. The supernatant was removed, and the resin was washed with membrane extraction buffer provided by the Mem-PER™ kit. The proteins retained on the resin were eluted with a solution of 1 mM of 6-ND.

To define the interactors shared between 4-nitropropanolol and 6-ND, we identified the proteins retained on the beads in the competitor assay and subtracted this list from that obtained in the absence of the competitor, as described above.

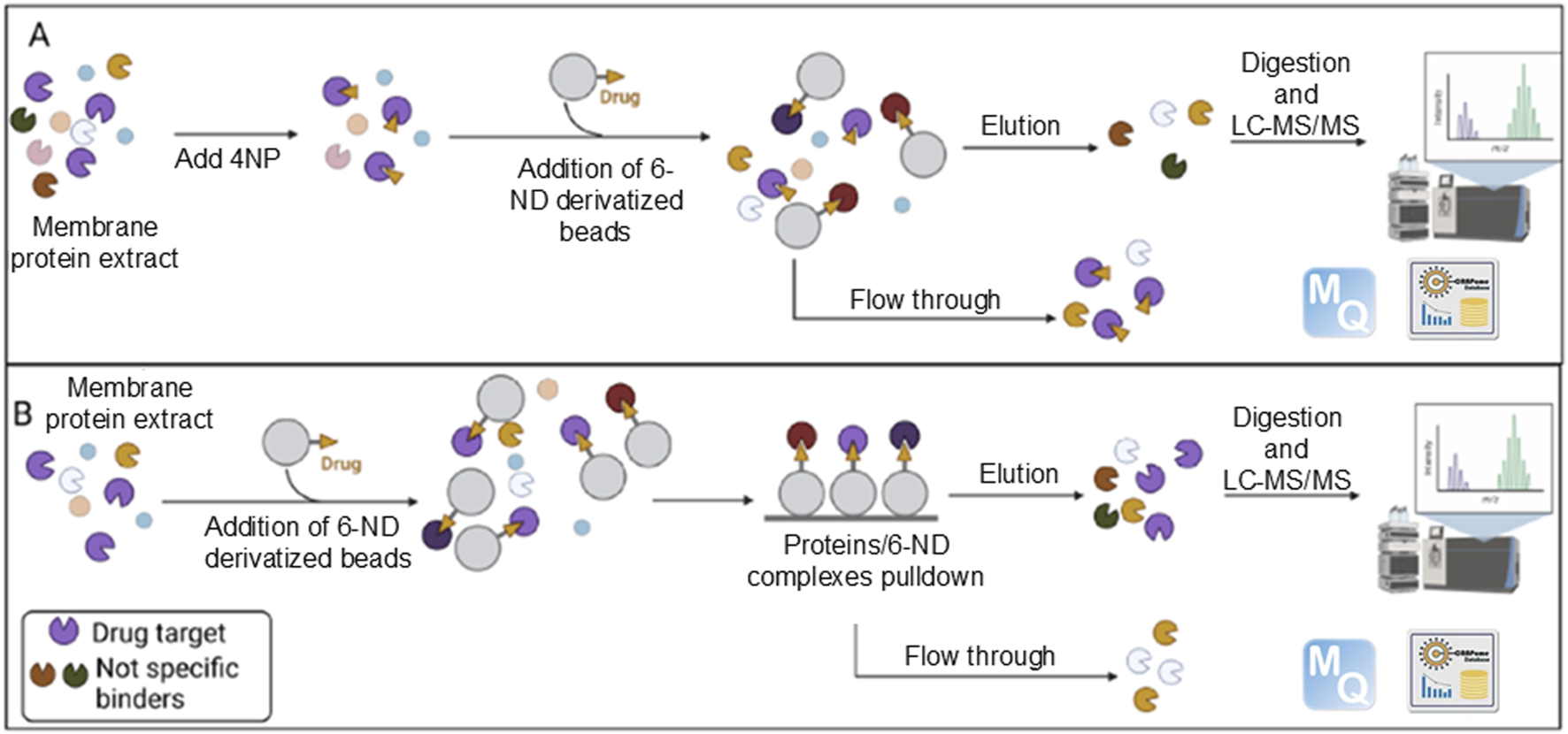

2.3 Protein separation and identification

The proteins derived from chemical pulldown were fractionated by SDS-PAGE. The gel was stained with GelCode™ Blue Safe Protein Stain (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States) and destained with Milli-Q water. A total of nine bands were cut and in situ-hydrolyzed by trypsin (Iaconis et al., 2017). Peptide mixtures were extracted in 0.2% HCOOH and ACN and vacuum-dried using a SpeedVac System (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Peptide mixtures from the hydrolyzed gel bands were analyzed on an Orbitrap Exploris 240 instrument equipped with a Nanospray Flex ion source and coupled with a Vanquish Neo nanoUPLC system. Samples were fractionated using a C18 capillary reverse-phase column (150 mm, 75, 2 μm 100 Å) at a flow rate of 250 nL/min. A linear gradient of eluent B (0.2% formic acid in 95% acetonitrile) in A (0.2% formic acid and 2% acetonitrile in LC-MS grade water) was used from 2% to 90% in 77 min. The MS/MS method, based on a data-dependent acquisition (DDA) mode, recorded a single full-scan spectrum in the 375–1,200 m/z range, followed by fragmentation spectra of the top 20 ions (MS/MS scan) selected according to the intensity and charge state (+2, +3, and multi-charges), with a dynamic exclusion time of 40 s. Protein identification was carried out using MaxQuant software (v.1.5.2.8), with the UniProt Homo Sapiens database, as previously described (Palinski et al., 2021). A diagram illustrating the above-described steps is presented in Figure 3.

FIGURE 3

Graphical summary of the experimental strategy. Enriched membrane proteins were incubated with beads covalently coupled to 6-ND, either in the presence (A) or in the absence (B) of 4-nitropropranolol (4NP). Proteins binding to 6-ND and retained on the beads were subsequently eluted and identified through LC-MS/MS analysis. Adapted form Iacobucci et al. (2023), licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Nonspecific contaminants were also removed for comparison using the Contaminant Repository for Affinity Purification (CRAPome) 2.0 web tool (https://reprint-apms.org). Contaminants defined as proteins reported in at least 50% of similar experiments were discarded from the initial lists (Iacobucci et al., 2022).

2.4 Functional clustering analysis

Cell compartment enrichment analysis was carried out using FunRich 3.1.3 (Fonseka et al., 2021) software by querying the Gene Ontology database. The Benjamini–Hochberg adjusted p-value (FDR) and fold enrichment cutoffs were 0.001 and 3, respectively. The biological process over-representation analysis was performed using the ClueGO 2.5.7 app (Bindea et al., 2009) of the Cytoscape platform (FDR < 0.05).

2.5 Animals

Adult male Wistar rats (280–320 g) were obtained from the Central Animal House at the University of Campinas (CEMIB-UNICAMP; São Paulo, Brazil). All experimental protocols were approved by the Ethics Committee for Animal Use of the UNICAMP (CEUA; Protocol No. 5746-1/2021; 5831-1/2021), following the Brazilian Guidelines for the Production, Maintenance, and Use of Animals for Teaching or Research from the National Council of Control in Animal Experimentation (CONCEA), and the ARRIVE guidelines (Percie du Sert et al., 2020). Three individuals were housed in each cage placed on ventilated shelters at a humidity of 55% ± 5% and a temperature of 24°C ± 1°C under a 12-h light–dark cycle. Animals received filtered water and standard rodent food ad libitum.

2.6 Langendorff’s isolated perfused heart preparation and measurements of heart contractile function

Heparin (1,000 IU/kg) was previously injected intraperitoneally into the animals to prevent blood clotting, and euthanasia was performed by administering isoflurane overdose, as previously described (Britto-Júnior et al., 2023a). Exsanguination was performed to confirm the euthanasia. The chest was opened, the heart was rapidly excised, the ascending aorta was cannulated, and the heart was mounted on a nonrecirculating Langendorff apparatus. The isolated heart was perfused with Krebs–Henseleit’s solution (pH 7.4, 37°C) equilibrated with a carbogen gas mixture (95% O2: 5% CO2) at a constant flow (10 mL/min), and left ventricular end-diastolic pressure (LVEDP) was maintained between 4 and 8 mmHg during the initial equilibrium of the experiment (Britto-Júnior et al., 2023a). A water-filled latex balloon, connected to the pressure transducer (MLT1199 BP Transducer, ADInstruments, Inc., Dunedin, NZ), was inserted into the left ventricle (LV) via the mitral valve. Left ventricular systolic pressure (LVSP), left ventricular end-diastolic pressure (LVeDP), and heart rate (HR) were continuously recorded using a PowerLab System (ADInstruments, Inc., Dunedin, NZ). Only hearts that presented a basal heart rate between 250 and 300 bpm were employed in the experiments.

The hearts were allowed to equilibrate for at least 10 min, and the effects of a 1-min infusion (100 μL/min) 6-nitrodopamine (0.01, 0.1, or 1 pM final concentration) were evaluated. Each heart was subjected to only one infusion. Changes were monitored for 30 min. To investigate the synergism between 6-nitrodopamine and noradrenaline in the Langendorff’s perfused heart analysis, the following protocols were employed. One-minute (100 μL/min) infusion of 6-nitrodopamine (0.001 or 0.01 pM, final concentration) was performed, and then, a single bolus of noradrenaline (1 pmol) was administered, and the heart was monitored for 15 min. One heart was used for a single drug and infusion. Data obtained from the Landendorff preparations (heart rate, LVDP, dP/dt max, and RPP) were expressed as left ventricular developed pressure (LVDP), calculated using the following formula: LVSP − LVeDP, and expressed in mmHg. The rate pressure product (RPP) was defined as the product of HR and LVDP: RPP = (HR × LVDP). The maximal rate of increase in the left ventricular pressure (+dP/dtmax) was monitored continuously using a pressure transducer connected to a PowerLab system (AD Instrument, Australia).

2.7 Statistical analysis

Data obtained from the Langendorff preparations were represented by mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Comparison between baseline values and those obtained during drug stimulation in the same sample was performed using the paired t-test. Comparison between two groups was performed using the unpaired t-test. Comparisons among three or more groups were evaluated using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by the Newman–Keuls test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

2.8 Chemicals and reagents

Noradrenaline was obtained from Cayman Chemicals (Michigan, United States). 6-Nitrodopamine was acquired from Toronto Research Chemicals (Ontario, CA). PureCube Carboxy Agarose Beads were purchased from Cube Biotech (Monheim, Germany). Trypsin, the Mem-PER™ Plus Membrane Protein Extraction Kit, Pierce 660 nm Protein Assay, GelCode™ Blue Safe Protein Stain, Orbitrap Exploris 240 (Mass Spectrometer), and Vanquish Neo nanoUPLC System were acquired from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, United States). 4-NO2-propranolol was synthesized as described elsewhere (Sparaco et al., 2022). Sodium chloride (NaCl), potassium chloride (KCl), calcium chloride (CaCl2), magnesium sulfate (MgSO4), sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3), potassium phosphate mono-basic (KH2PO4), and glucose were acquired from Merck KGaA (Darmstadt, Germany).

3 Results

3.1 Identification of 6-ND targets in cardiomyocytes

The proteins identified from the pre-clearing (PC lane) were discarded from the protein list obtained in the chemical pulldown (PD lane). The remaining proteins were filtered against the proteins listed in the Contaminant Repository for Affinity Purification (CRAPome) 2.0 (Mellacheruvu et al., 2013). At the end of this procedure, 869 potential 6-ND direct and indirect interactors were obtained (Supplementary Table S1). Another pulldown experiment was performed in the presence of an excess of 4-nitro-propranolol, the 6-ND antagonist. Eighty-two proteins were retained on the beads and represent the specific interactors of 6-ND (Table 1), and 52 have already been identified in the pulldown with 6-ND. By subtracting these 52 proteins from the 869 potential 6-ND direct and indirect interactors, a list of 817 proteins was obtained (Supplementary Table S2), which represent the interactors shared between 6-ND and 4-nitropropranolol experiments.

TABLE 1

| Uniprot ID | Protein name | Gene name | Sequence coverage [%] | Razor + unique peptides | Unique peptides |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P35914 | Hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA lyase, mitochondrial | HMGCL | 10.2 | 4 | 4 |

| Q96DB5 | Regulator of microtubule dynamics protein 1 | RMDN1 | 10.8 | 4 | 4 |

| Q9H3N1 | Thioredoxin-related transmembrane protein 1 | TMX1 | 12.1 | 4 | 4 |

| P07858 | Cathepsin B | CTSB | 12.4 | 5 | 5 |

| P48047 | ATP synthase subunit O, mitochondrial | ATP5PO | 15 | 4 | 4 |

| Q16698 | 2,4-dienoyl-CoA reductase, mitochondrial | DECR1 | 15.8 | 4 | 4 |

| Q8NBJ7 | Inactive C-alpha-formylglycine-generating enzyme 2 | SUMF2 | 16.3 | 4 | 4 |

| Q9BPW8 | Protein NipSnap homolog 1 | NIPSNAP1 | 16.5 | 5 | 4 |

| P51572 | B-cell receptor-associated protein 31 | BCAP31 | 17.5 | 4 | 4 |

| Q9BVK6 | Transmembrane emp24 domain-containing protein 9 | TMED9 | 19.1 | 5 | 4 |

| O15400 | Syntaxin-7 | STX7 | 19.9 | 4 | 4 |

| O95571 | Persulfide dioxygenase ETHE1, mitochondrial | ETHE1 | 20.9 | 4 | 4 |

| Q96CN7 | Isochorismatase domain-containing protein 1 | ISOC1 | 21.1 | 4 | 4 |

| P09429 | High-mobility group protein B1 | HMGB1 | 21.4 | 4 | 4 |

| P09012 | U1 small-nuclear ribonucleoprotein A | SNRPA | 22.3 | 4 | 3 |

| P62258 | 14-3-3 protein epsilon | YWHAE | 23.1 | 4 | 4 |

| P61019 | Ras-related protein R2A | RAB2A | 23.1 | 4 | 2 |

| P30041 | Peroxiredoxin-6 | PRDX6 | 23.2 | 4 | 4 |

| P61106 | Ras-related protein R14 | RAB14 | 23.3 | 5 | 5 |

| Q9NXA8 | NAD-dependent protein deacylase sirtuin-5, mitochondrial | SIRT5 | 23.9 | 6 | 6 |

| P20340 | Ras-related protein R6A | RAB6A | 24 | 6 | 6 |

| Q9NP72 | Ras-related protein R18 | RAB18 | 24.3 | 4 | 4 |

| P62826 | GTP-binding nuclear protein Ran | RAN | 24.5 | 5 | 5 |

| Q7Z4W1 | L-xylulose reductase | DCXR | 24.6 | 4 | 4 |

| O95292 | Vesicle-associated membrane protein-associated protein B/C | VAPB | 24.7 | 5 | 4 |

| O15173 | Membrane-associated progesterone receptor component 2 | PGRMC2 | 26.5 | 5 | 5 |

| Q86V81 | THO complex subunit 4 | ALYREF | 26.8 | 4 | 4 |

| P0DPI2 | Glutamine amidotransferase-like class 1 domain-containing protein 3A, mitochondrial | GATD3A | 27.2 | 6 | 6 |

| Q9H9Z2 | Protein lin-28 homolog A | LIN28A | 27.8 | 4 | 4 |

| P27144 | Adenylate kinase 4, mitochondrial | AK4 | 28.7 | 4 | 4 |

| P30086 | Phosphatidylethanolamine-binding protein 1 | BP1 | 28.9 | 4 | 4 |

| P51148 | Ras-related protein R5C | RAB5C | 29.2 | 5 | 4 |

| P61586 | Transforming protein RhoA | RHOA | 29.5 | 7 | 6 |

| Q15691 | Microtubule-associated protein RP/EB family member 1 | MAPRE1 | 30.6 | 5 | 5 |

| Q9UIJ7 | GTP:AMP phosphotransferase AK3, mitochondrial | AK3 | 33.5 | 7 | 7 |

| P63104 | 14-3-3 protein zeta/delta | YWHAZ | 35.5 | 8 | 7 |

| P09211 | Glutathione S-transferase P | GSTP1 | 36.2 | 5 | 5 |

| O00264 | Membrane-associated progesterone receptor component 1 | PGRMC1 | 36.9 | 8 | 7 |

| O75947 | ATP synthase subunit d, mitochondrial | ATP5PD | 37.9 | 6 | 6 |

| P46782 | 40S ribosomal protein S5 | RPS5 | 41.7 | 8 | 8 |

| Q99497 | Protein/nucleic acid deglycase DJ-1 | PARK7 | 43.9 | 4 | 4 |

| Q99714 | 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase type-2 | HSD17B10 | 47.9 | 7 | 7 |

| P63244 | Receptor of activated protein C kinase 1 | RACK1 | 54.9 | 15 | 15 |

| O15382 | Branched-chain-amino-acid aminotransferase, mitochondrial | BCAT2 | 12.2 | 4 | 4 |

| P23526 | Adenylhomocysteinase | AHCY | 12.7 | 5 | 5 |

| Q8NBX0 | Saccharopine dehydrogenase-like oxidoreductase | SCCPDH | 13.1 | 4 | 4 |

| P09486 | SPARC | SPARC | 13.2 | 4 | 4 |

| P24752 | Acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase, mitochondrial | ACAT1 | 14.3 | 4 | 4 |

| Q7L592 | Protein arginine methyltransferase NDUFAF7, mitochondrial | NDUFAF7 | 14.7 | 4 | 4 |

| Q13510 | Acid ceramidase | ASAH1 | 14.7 | 5 | 5 |

| P82650 | 28S ribosomal protein S22, mitochondrial | MRPS22 | 14.7 | 4 | 4 |

| P50148 | Guanine nucleotide-binding protein G(q) subunit alpha | GNAQ | 15.3 | 4 | 4 |

| P78310 | Coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor | CXADR | 15.3 | 5 | 5 |

| P17612 | cAMP-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit alpha | PRKACA | 15.7 | 4 | 4 |

| P17174 | Aspartate aminotransferase, cytoplasmic | GOT1 | 16.7 | 4 | 4 |

| Q15738 | Sterol-4-alpha-carboxylate 3-dehydrogenase, decarboxylating | NSDHL | 17.2 | 4 | 4 |

| Q12907 | Vesicular integral-membrane protein VIP36 | LMAN2 | 17.4 | 6 | 6 |

| O43464 | Serine protease HTRA2, mitochondrial | HTRA2 | 18.3 | 5 | 5 |

| Q9BWD1 | Acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase, cytosolic | ACAT2 | 19.4 | 4 | 4 |

| Q9Y371 | Endophilin-B1 | SH3GLB1 | 19.5 | 5 | 5 |

| Q9H2U2 | Inorganic pyrophosphatase 2, mitochondrial | PPA2 | 20.1 | 5 | 5 |

| Q9Y2S7 | Polymerase delta-interacting protein 2 | POLDIP2 | 20.4 | 5 | 5 |

| Q6NVY1 | 3-hydroxyisobutyryl-CoA hydrolase, mitochondrial | HIBCH | 22 | 6 | 6 |

| P52907 | F-actin-capping protein subunit alpha-1 | CAPZA1 | 22 | 4 | 3 |

| Q9Y3F4 | Serine–threonine kinase receptor-associated protein | STRAP | 22.6 | 4 | 4 |

| A8MXV4 | Nucleoside diphosphate-linked moiety X motif 19 | NUDT19 | 23.2 | 5 | 5 |

| Q4G0N4 | NAD kinase 2, mitochondrial | NADK2 | 23.5 | 6 | 6 |

| Q9BTV4 | Transmembrane protein 43 | TMEM43 | 23.5 | 5 | 5 |

| P16422 | Epithelial cell adhesion molecule | EPCAM | 23.6 | 7 | 7 |

| Q9BXW7 | Haloacid dehalogenase-like hydrolase domain-containing 5 | HDHD5 | 24.1 | 7 | 7 |

| O75521 | Enoyl-CoA delta isomerase 2, mitochondrial | ECI2 | 24.9 | 5 | 5 |

| P16219 | Short-chain-specific acyl-CoA dehydrogenase, mitochondrial | ACADS | 25.5 | 7 | 7 |

| O43148 | mRNA cap guanine-N7 methyltransferase | RNMT | 25.8 | 8 | 8 |

| O94905 | Erlin-2 | ERLIN2 | 26.8 | 8 | 8 |

| P00387 | NADH-cytochrome b5 reductase 3 | CYB5R3 | 27.6 | 5 | 5 |

| P45954 | Short-/branched-chain-specific acyl-CoA dehydrogenase, mitochondrial | ACADSB | 29.9 | 8 | 8 |

| P50453 | Serpin B9 | SERPINB9 | 30.6 | 9 | 9 |

| P62140 | Serine/threonine–protein phosphatase PP1-beta catalytic subunit | PPP1CB | 36.4 | 12 | 2 |

| O00330 | Pyruvate dehydrogenase protein X component, mitochondrial | PDHX | 13 | 5 | 5 |

| Q9ULV4 | Coronin-1C | CORO1C | 13.5 | 6 | 6 |

| Q9NZW5 | MAGUK p55 subfamily member 6 | MPP6 | 16.7 | 8 | 8 |

| P04040 | Catalase | CAT | 21.1 | 8 | 8 |

List of proteins retained on the beads following the chemical pulldown experiment performed using an excess of 4-nitro-propranolol.

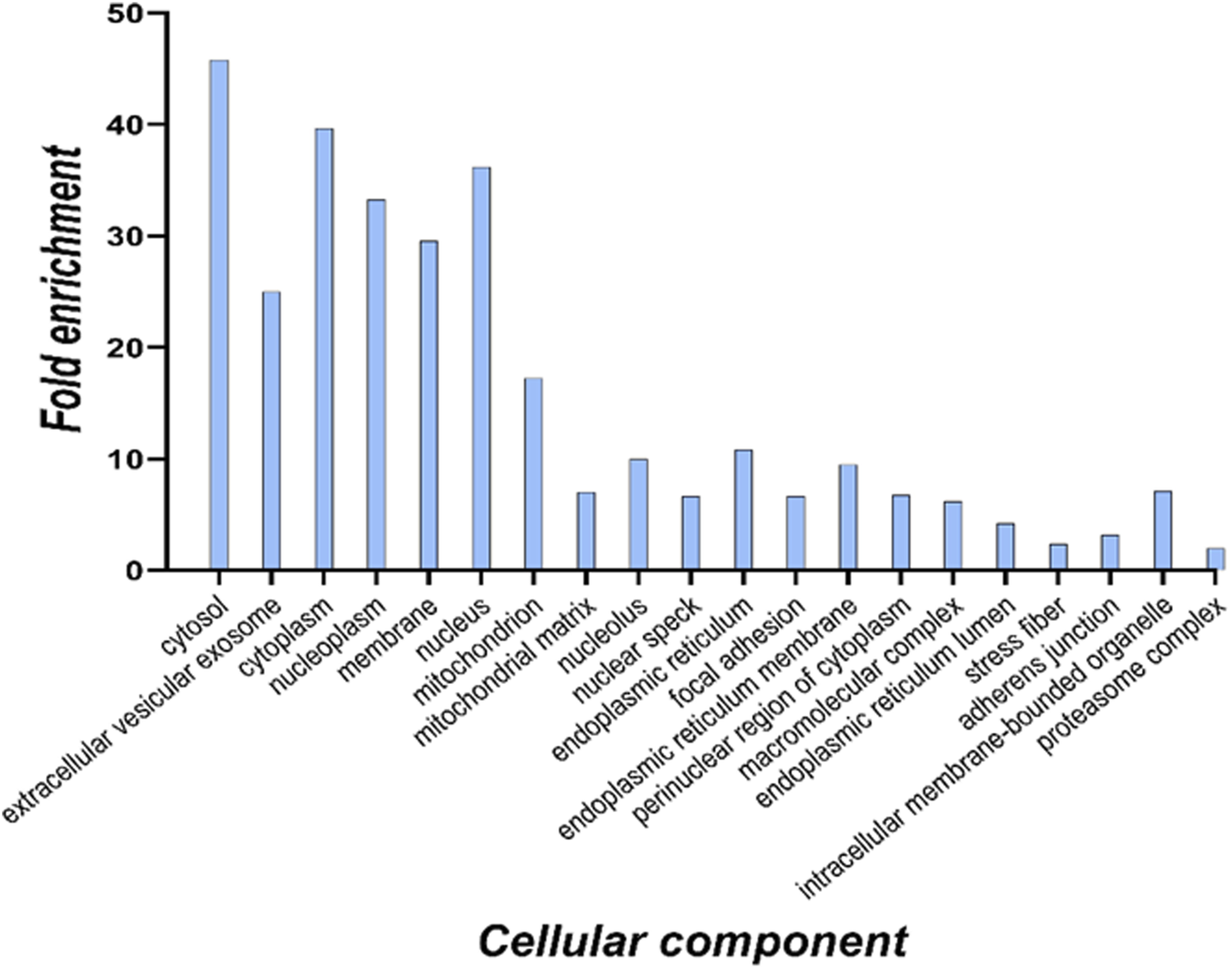

3.2 Functional enrichment analysis of 6-ND targets

To define cell components enriched in the targets of 6-ND within cardiomyocytes, an over-representation analysis was performed on the 817 proteins in common with the competitor. The identified proteins were functionally analyzed using the FunRich 3.1.3 search engine, in order to interrogate the Gene Ontology database for subcellular localizations. The terms were considered significant when the FDR was <0.001 and the fold enrichment was higher than 3. The results are reported in the histogram in Figure 4.

FIGURE 4

Cellular component analysis of all identified 6-ND targets based on the Gene Ontology database. For each enriched term, the histogram displays the fold enrichment value.

The cellular component analysis suggested a distribution of potential 6-ND targets through different cell compartments. This finding was expected since the membrane protein extract was partially contaminated also with cytosolic proteins, as suggested by the Western blot assay (Figure 1).

Therefore, in light of our interest in potential cell surface targets, the UniProt “Retrieve/ID Mapping” function (Pundir et al., 2016) was used; the total protein list was further screened according to the Gene Ontology cellular component category, and only those genes whose annotation contained the term “membrane” were considered for further analyses. From the initial list of 869 entries, only 124 (Table 2) were selected because they satisfied the previous restriction criteria.

TABLE 2

| Uniprot ID | Protein name | Gene name | Sequence coverage [%] | Razor + unique peptides | Unique peptides |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A0FGR8 | Extended synaptotagmin-2 | ESYT2 | 12.3 | 10 | 10 |

| O00186 | Syntaxin-binding protein 3 | STXBP3 | 14.4 | 10 | 10 |

| O14672 | Disintegrin and metalloproteinase domain-containing protein 10 | ADAM10 | 19.9 | 15 | 15 |

| O14936 | Peripheral plasma membrane protein CASK | CASK | 28.3 | 25 | 25 |

| O15031 | Plexin-B2 | PLXNB2 | 15.6 | 23 | 22 |

| O43278 | Kunitz-type protease inhibitor 1 | SPINT1 | 34.8 | 18 | 18 |

| Q01518 | Adenylyl cyclase-associated protein 1 | CAP1 | 39.6 | 18 | 18 |

| O43865 | S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase-like protein 1 | AHCYL1 | 20.2 | 12 | 5 |

| O60488 | Long-chain-fatty-acid--CoA ligase 4 | ACSL4 | 13.9 | 6 | 6 |

| P10644 | cAMP-dependent protein kinase type I-alpha regulatory subunit | PRKAR1A | 10 | 5 | 5 |

| O75923 | Dysferlin | DYSF | 12.8 | 20 | 20 |

| Q9UKS6 | Protein kinase C and casein kinase substrate in neuron protein 3 | PACSIN3 | 11.8 | 5 | 5 |

| O75976 | Carboxypeptidase D | CPD | 21.4 | 28 | 28 |

| O94875 | Sorbin and SH3 domain-containing protein 2 | SORBS2 | 15.2 | 12 | 11 |

| O94973 | AP-2 complex subunit alpha-2 | AP2A2 | 42.2 | 19 | 19 |

| Q15019 | Septin-2 | SEPTIN2 | 37.4 | 11 | 11 |

| P78310 | Coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor | CXADR | 24.7 | 10 | 10 |

| P05067 | Amyloid-beta precursor protein | APP | 19.5 | 14 | 12 |

| P05186 | Alkaline phosphatase, tissue-nonspecific isozyme | ALPL | 13 | 5 | 5 |

| P07384 | Calpain-1 catalytic subunit | CAPN1 | 14.6 | 10 | 10 |

| P07947 | Tyrosine–protein kinase Yes | YES1 | 32.2 | 9 | 8 |

| P07948 | Tyrosine–protein kinase Lyn | LYN | 22.1 | 9 | 9 |

| P08069 | Insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor | IGF1R | 11.2 | 15 | 12 |

| P15151 | Poliovirus receptor | PVR | 14.6 | 4 | 4 |

| Q9BRK5 | 45 kDa calcium-binding protein | SDF4 | 11.6 | 5 | 5 |

| P08582 | Melanotransferrin | MELTF | 16.9 | 11 | 11 |

| O75955 | Flotillin-1 | FLOT1 | 10.8 | 5 | 5 |

| Q6NZI2 | Caveolae-associated protein 1 | CAVIN1 | 14.4 | 5 | 5 |

| P12830 | Cadherin-1 | CDH1 | 11.3 | 8 | 7 |

| P12931 | Proto-oncogene tyrosine–protein kinase Src | SRC | 34.1 | 16 | 11 |

| P14735 | Insulin-degrading enzyme | IDE | 11.7 | 12 | 12 |

| P48426 | Phosphatidylinositol 5–phosphate 4-kinase type-2 alpha | PIP4K2A | 16 | 6 | 4 |

| P17655 | Calpain-2 catalytic subunit | CAPN2 | 11.3 | 7 | 7 |

| P18084 | Integrin beta-5 | ITGB5 | 17.1 | 12 | 12 |

| P18564 | Integrin beta-6 | ITGB6 | 15.2 | 10 | 10 |

| Q13449 | Limbic system-associated membrane protein | LSAMP | 14.2 | 5 | 5 |

| P26232 | Catenin alpha-2 | CTNNA2 | 35.4 | 15 | 15 |

| P01876 | Immunoglobulin heavy constant alpha 1 | IGHA1 | 22.4 | 7 | 4 |

| P29323 | Ephrin type-B receptor 2 | EPHB2 | 12.6 | 9 | 8 |

| P49841 | Glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta | GSK3B | 17.4 | 6 | 4 |

| P31327 | Carbamoyl–phosphate synthase [ammonia], mitochondrial | CPS1 | 23.2 | 29 | 29 |

| Q96CX2 | BTB/POZ domain-containing protein KCTD12 | KCTD12 | 29.5 | 11 | 11 |

| P35241 | Radixin | RDX | 48 | 20 | 20 |

| P35611 | Alpha-adducin | ADD1 | 30.4 | 19 | 18 |

| Q9ULV4 | Coronin-1C | CORO1C | 53.2 | 25 | 24 |

| P46940 | Ras GTPase-activating-like protein IQGAP1 | IQGAP1 | 12.4 | 21 | 21 |

| P31323 | cAMP-dependent protein kinase type II-beta regulatory subunit | PRKAR2B | 32.3 | 9 | 9 |

| P49757 | Protein numb homolog | NUMB | 14.9 | 8 | 8 |

| Q9Y5X3 | Sorting nexin-5 | SNX5 | 11.9 | 4 | 4 |

| P50570 | Dynamin-2 | DNM2 | 10.5 | 8 | 8 |

| P53041 | Serine/threonine–protein phosphatase 5 | PPP5C | 12.6 | 6 | 6 |

| P53618 | Coatomer subunit beta | COPB1 | 24.8 | 20 | 20 |

| P54578 | Ubiquitin carboxyl–terminal hydrolase 14 | USP14 | 31.6 | 14 | 14 |

| P54753 | Ephrin type-B receptor 3 | EPHB3 | 16.2 | 14 | 11 |

| Q9H4A6 | Golgi phosphoprotein 3 | GOLPH3 | 16.1 | 4 | 4 |

| P21796 | Voltage-dependent anion-selective channel protein 1 | VDAC1 | 45.6 | 11 | 11 |

| P27105 | Erythrocyte band 7 integral membrane protein | STOM | 46.5 | 11 | 11 |

| P08174 | Complement decay-accelerating factor | CD55 | 10.5 | 5 | 5 |

| P40123 | Adenylyl cyclase-associated protein 2 | CAP2 | 17.6 | 8 | 8 |

| Q01650 | Large neutral amino acid transporter small subunit 1 | SLC7A5 | 13.6 | 7 | 7 |

| Q01844 | RNA-binding protein EWS | EWSR1 | 14.3 | 7 | 7 |

| Q02487 | Desmocollin-2 | DSC2 | 11.5 | 9 | 9 |

| Q06787 | Synaptic functional regulator FMR1 | FMR1 | 21.5 | 13 | 12 |

| Q08209 | Serine/threonine–protein phosphatase 2B catalytic subunit alpha isoform | PPP3CA | 18.8 | 9 | 6 |

| Q08554 | Desmocollin-1 | DSC1 | 10.5 | 9 | 9 |

| Q12959 | Disks large homolog 1 | DLG1 | 17.3 | 17 | 17 |

| Q13153 | Serine/threonine–protein kinase PAK 1 | PAK1 | 25.5 | 5 | 3 |

| Q13177 | Serine/threonine–protein kinase PAK 2 | PAK2 | 27.3 | 11 | 5 |

| Q13356 | RING-type E3 ubiquitin–protein ligase PPIL2 | PPIL2 | 12.3 | 5 | 5 |

| O95210 | Starch-binding domain-containing protein 1 | STBD1 | 17.6 | 5 | 5 |

| Q13564 | NEDD8-activating enzyme E1 regulatory subunit | NAE1 | 15.7 | 8 | 8 |

| Q13586 | Stromal interaction molecule 1 | STIM1 | 12.8 | 7 | 7 |

| Q13740 | CD166 antigen | ALCAM | 25.9 | 14 | 14 |

| Q13884 | Beta-1-syntrophin | SNTB1 | 17.1 | 8 | 8 |

| Q14126 | Desmoglein-2 | DSG2 | 18.5 | 15 | 15 |

| P09104 | Gamma-enolase | ENO2 | 23.5 | 5 | 4 |

| Q14699 | Raftlin | RFTN1 | 33.4 | 15 | 15 |

| Q14BN4 | Sarcolemmal membrane-associated protein | SLMAP | 15.5 | 11 | 11 |

| O75781 | Paralemmin-1 | PALM | 42.1 | 16 | 14 |

| Q15642 | Cdc42-interacting protein 4 | TRIP10 | 33.6 | 15 | 15 |

| Q16625 | Occludin | OCLN | 10.2 | 5 | 5 |

| Q5T0N5 | Formin-binding protein 1-like | FNBP1L | 12.4 | 8 | 8 |

| Q5T2T1 | MAGUK p55 subfamily member 7 | MPP7 | 11.5 | 6 | 6 |

| Q9Y639 | Neuroplastin | NPTN | 26.4 | 11 | 11 |

| Q86X29 | Lipolysis-stimulated lipoprotein receptor | LSR | 11.7 | 6 | 6 |

| Q8IZL8 | Proline-, glutamic acid-, and leucine-rich protein 1 | PELP1 | 16.6 | 13 | 13 |

| Q8N3R9 | MAGUK p55 subfamily member 5 | MPP5 | 25.8 | 15 | 15 |

| Q92692 | Nectin-2 | NECTIN2 | 23.8 | 10 | 10 |

| Q93052 | Lipoma-preferred partner | LPP | 30.6 | 17 | 17 |

| P98172 | Ephrin-B1 | EFNB1 | 23.7 | 5 | 5 |

| Q96D71 | RalBP1-associated Eps domain-containing protein 1 | REPS1 | 11.8 | 8 | 8 |

| Q96IF1 | LIM domain-containing protein ajuba | AJUBA | 16.7 | 7 | 7 |

| Q96J84 | Kin of IRRE-like protein 1 | KIRREL1 | 10.6 | 7 | 7 |

| O43493 | Trans-Golgi network integral membrane protein 2 | TGOLN2 | 30.5 | 13 | 13 |

| Q99523 | Sortilin | SORT1 | 19 | 17 | 17 |

| Q99829 | Copine-1 | CPNE1 | 12.8 | 8 | 8 |

| Q96QA5 | Gasdermin-A | GSDMA | 18.4 | 7 | 7 |

| P50148 | Guanine nucleotide-binding protein G(q) subunit alpha | GNAQ | 30.6 | 10 | 7 |

| Q9BZF1 | Oxysterol-binding protein-related protein 8 | OSBPL8 | 13.3 | 12 | 12 |

| Q9H223 | EH domain-containing protein 4 | EHD4 | 16.6 | 7 | 6 |

| P07858 | Cathepsin B | CTSB | 19.8 | 6 | 6 |

| Q9H4M9 | EH domain-containing protein 1 | EHD1 | 23.6 | 11 | 7 |

| P16422 | Epithelial cell adhesion molecule | EPCAM | 33.1 | 10 | 10 |

| Q9UBC2 | Epidermal growth factor receptor substrate 15-like 1 | EPS15L1 | 16 | 12 | 12 |

| Q9UDY2 | Tight junction protein ZO-2 | TJP2 | 10.3 | 9 | 9 |

| Q9UEY8 | Gamma-adducin | ADD3 | 12.3 | 8 | 8 |

| Q9UH65 | Switch-associated protein 70 | SWAP70 | 13.8 | 8 | 8 |

| Q9UHB6 | LIM domain and actin-binding protein 1 | LIMA1 | 24.5 | 17 | 17 |

| Q9BRK3 | Matrix remodeling-associated protein 8 | MXRA8 | 14.5 | 8 | 8 |

| Q9UMX0 | Ubiquilin-1 | UBQLN1 | 31.1 | 10 | 5 |

| Q9UNF0 | Protein kinase C and casein kinase substrate in neuron protein 2 | PACSIN2 | 33.7 | 16 | 15 |

| Q9UPT5 | Exocyst complex component 7 | EXOC7 | 15.6 | 11 | 11 |

| Q14254 | Flotillin-2 | FLOT2 | 23.4 | 10 | 10 |

| P08138 | Tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 16 | NGFR | 11.9 | 4 | 4 |

| P63244 | Receptor of activated protein C kinase 1 | RACK1 | 64.7 | 18 | 18 |

| Q9Y6I3 | Epsin-1 | EPN1 | 13.7 | 4 | 4 |

| P35232 | Prohibitin | PHB | 43.4 | 10 | 10 |

| P51148 | Ras-related protein Rab-5C | RAB5C | 32.9 | 5 | 5 |

| P61586 | Transforming protein RhoA | RHOA | 47.2 | 8 | 8 |

| P62491 | Ras-related protein Rab-11A | RAB11A | 31.5 | 7 | 6 |

| P63000 | Ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 1 | RAC1 | 38 | 7 | 7 |

| P80723 | Brain acid-soluble protein 1 | BASP1 | 75.3 | 9 | 9 |

| Q9P0L0 | Vesicle-associated membrane protein-associated protein A | VAPA | 22.9 | 5 | 4 |

| Q9Y696 | Chloride intracellular channel protein 4 | CLIC4 | 30 | 4 | 4 |

List of proteins screened according to the Gene Ontology cellular localization in membrane. The UniProt ID, the protein and gene names, the sequence coverage 9(%), and the number of identified peptides are also reported.

Surprisingly, 116 proteins among the 124 are present in the list of the competitor binding proteins (Table 3). This finding highlights an almost complete overlapping between the sets of membrane protein targets recognized by the two active drugs, suggesting their involvement in stimulation/regulation of common regulative processes.

TABLE 3

| Uniprot ID | Protein name | Gene name | Sequence coverage [%] | Razor + unique peptides | Unique peptides |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A0FGR8 | Extended synaptotagmin-2 | ESYT2 | 12.3 | 10 | 10 |

| O00186 | Syntaxin-binding protein 3 | STXBP3 | 14.4 | 10 | 10 |

| O14672 | Disintegrin and metalloproteinase domain-containing protein 10 | ADAM10 | 19.9 | 15 | 15 |

| O14936 | Peripheral plasma membrane protein CASK | CASK | 28.3 | 25 | 25 |

| O15031 | Plexin-B2 | PLXNB2 | 15.6 | 23 | 22 |

| O43278 | Kunitz-type protease inhibitor 1 | SPINT1 | 34.8 | 18 | 18 |

| Q01518 | Adenylyl cyclase-associated protein 1 | CAP1 | 39.6 | 18 | 18 |

| O43865 | S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase-like protein 1 | AHCYL1 | 20.2 | 12 | 5 |

| O60488 | Long-chain-fatty-acid--CoA ligase 4 | ACSL4 | 13.9 | 6 | 6 |

| P10644 | cAMP-dependent protein kinase type I-alpha regulatory subunit | PRKAR1A | 10 | 5 | 5 |

| O75923 | Dysferlin | DYSF | 12.8 | 20 | 20 |

| Q9UKS6 | Protein kinase C and casein kinase substrate in neuron protein 3 | PACSIN3 | 11.8 | 5 | 5 |

| O75976 | Carboxypeptidase D | CPD | 21.4 | 28 | 28 |

| O94875 | Sorbin and SH3 domain-containing protein 2 | SORBS2 | 15.2 | 12 | 11 |

| O94973 | AP-2 complex subunit alpha-2 | AP2A2 | 42.2 | 19 | 19 |

| Q15019 | Septin-2 | SEPTIN2 | 37.4 | 11 | 11 |

| P05067 | Amyloid-beta precursor protein | APP | 19.5 | 14 | 12 |

| P05186 | Alkaline phosphatase, tissue-nonspecific isozyme | ALPL | 13 | 5 | 5 |

| P07384 | Calpain-1 catalytic subunit | CAPN1 | 14.6 | 10 | 10 |

| P07947 | Tyrosine–protein kinase Yes | YES1 | 32.2 | 9 | 8 |

| P07948 | Tyrosine–protein kinase Lyn | LYN | 22.1 | 9 | 9 |

| P08069 | Insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor | IGF1R | 11.2 | 15 | 12 |

| P15151 | Poliovirus receptor | PVR | 14.6 | 4 | 4 |

| Q9BRK5 | 45-kDa calcium-binding protein | SDF4 | 11.6 | 5 | 5 |

| P08582 | Melanotransferrin | MELTF | 16.9 | 11 | 11 |

| O75955 | Flotillin-1 | FLOT1 | 10.8 | 5 | 5 |

| Q6NZI2 | Caveolae-associated protein 1 | CAVIN1 | 14.4 | 5 | 5 |

| P12830 | Cadherin-1 | CDH1 | 11.3 | 8 | 7 |

| P12931 | Proto-oncogene tyrosine–protein kinase Src | SRC | 34.1 | 16 | 11 |

| P14735 | Insulin-degrading enzyme | IDE | 11.7 | 12 | 12 |

| P48426 | Phosphatidylinositol 5-phosphate 4-kinase type-2 alpha | PIP4K2A | 16 | 6 | 4 |

| P17655 | Calpain-2 catalytic subunit | CAPN2 | 11.3 | 7 | 7 |

| P18084 | Integrin beta-5 | ITGB5 | 17.1 | 12 | 12 |

| P18564 | Integrin beta-6 | ITGB6 | 15.2 | 10 | 10 |

| Q13449 | Limbic system-associated membrane protein | LSAMP | 14.2 | 5 | 5 |

| P26232 | Catenin alpha-2 | CTNNA2 | 35.4 | 15 | 15 |

| P01876 | Immunoglobulin heavy constant alpha 1 | IGHA1 | 22.4 | 7 | 4 |

| P29323 | Ephrin type-B receptor 2 | EPHB2 | 12.6 | 9 | 8 |

| P49841 | Glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta | GSK3B | 17.4 | 6 | 4 |

| P31327 | Carbamoyl–phosphate synthase (ammonia), mitochondrial | CPS1 | 23.2 | 29 | 29 |

| Q96CX2 | BTB/POZ domain-containing protein KCTD12 | KCTD12 | 29.5 | 11 | 11 |

| P35241 | Radixin | RDX | 48 | 20 | 20 |

| P35611 | Alpha-adducin | ADD1 | 30.4 | 19 | 18 |

| P46940 | Ras GTPase-activating-like protein IQGAP1 | IQGAP1 | 12.4 | 21 | 21 |

| P31323 | cAMP-dependent protein kinase type II-beta regulatory subunit | PRKAR2B | 32.3 | 9 | 9 |

| P49757 | Protein numb homolog | NUMB | 14.9 | 8 | 8 |

| Q9Y5X3 | Sorting nexin-5 | SNX5 | 11.9 | 4 | 4 |

| P50570 | Dynamin-2 | DNM2 | 10.5 | 8 | 8 |

| P53041 | Serine/threonine–protein phosphatase 5 | PPP5C | 12.6 | 6 | 6 |

| P53618 | Coatomer subunit beta | COPB1 | 24.8 | 20 | 20 |

| P54578 | Ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase 14 | USP14 | 31.6 | 14 | 14 |

| P54753 | Ephrin type-B receptor 3 | EPHB3 | 16.2 | 14 | 11 |

| Q9H4A6 | Golgi phosphoprotein 3 | GOLPH3 | 16.1 | 4 | 4 |

| P21796 | Voltage-dependent anion-selective channel protein 1 | VDAC1 | 45.6 | 11 | 11 |

| P27105 | Erythrocyte band 7 integral membrane protein | STOM | 46.5 | 11 | 11 |

| P08174 | Complement decay-accelerating factor | CD55 | 10.5 | 5 | 5 |

| P40123 | Adenylyl cyclase-associated protein 2 | CAP2 | 17.6 | 8 | 8 |

| Q01650 | Large neutral amino acid transporter small subunit 1 | SLC7A5 | 13.6 | 7 | 7 |

| Q01844 | RNA-binding protein EWS | EWSR1 | 14.3 | 7 | 7 |

| Q02487 | Desmocollin-2 | DSC2 | 11.5 | 9 | 9 |

| Q06787 | Synaptic functional regulator FMR1 | FMR1 | 21.5 | 13 | 12 |

| Q08209 | Serine/threonine–protein phosphatase 2B catalytic subunit alpha isoform | PPP3CA | 18.8 | 9 | 6 |

| Q08554 | Desmocollin-1 | DSC1 | 10.5 | 9 | 9 |

| Q12959 | Disks large homolog 1 | DLG1 | 17.3 | 17 | 17 |

| Q13153 | Serine/threonine–protein kinase PAK 1 | PAK1 | 25.5 | 5 | 3 |

| Q13177 | Serine/threonine–protein kinase PAK 2 | PAK2 | 27.3 | 11 | 5 |

| Q13356 | RING-type E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase PPIL2 | PPIL2 | 12.3 | 5 | 5 |

| O95210 | Starch-binding domain-containing protein 1 | STBD1 | 17.6 | 5 | 5 |

| Q13564 | NEDD8-activating enzyme E1 regulatory subunit | NAE1 | 15.7 | 8 | 8 |

| Q13586 | Stromal interaction molecule 1 | STIM1 | 12.8 | 7 | 7 |

| Q13740 | CD166 antigen | ALCAM | 25.9 | 14 | 14 |

| Q13884 | Beta-1-syntrophin | SNTB1 | 17.1 | 8 | 8 |

| Q14126 | Desmoglein-2 | DSG2 | 18.5 | 15 | 15 |

| P09104 | Gamma-enolase | ENO2 | 23.5 | 5 | 4 |

| Q14699 | Raftlin | RFTN1 | 33.4 | 15 | 15 |

| Q14BN4 | Sarcolemmal membrane-associated protein | SLMAP | 15.5 | 11 | 11 |

| O75781 | Paralemmin-1 | PALM | 42.1 | 16 | 14 |

| Q15642 | Cdc42-interacting protein 4 | TRIP10 | 33.6 | 15 | 15 |

| Q16625 | Occludin | OCLN | 10.2 | 5 | 5 |

| Q5T0N5 | Formin-binding protein 1-like | FNBP1L | 12.4 | 8 | 8 |

| Q5T2T1 | MAGUK p55 subfamily member 7 | MPP7 | 11.5 | 6 | 6 |

| Q9Y639 | Neuroplastin | NPTN | 26.4 | 11 | 11 |

| Q86X29 | Lipolysis-stimulated lipoprotein receptor | LSR | 11.7 | 6 | 6 |

| Q8IZL8 | Proline-, glutamic acid-, and leucine-rich protein 1 | PELP1 | 16.6 | 13 | 13 |

| Q8N3R9 | MAGUK p55 subfamily member 5 | PALS1 | 25.8 | 15 | 15 |

| Q92692 | Nectin-2 | NECTIN2 | 23.8 | 10 | 10 |

| Q93052 | Lipoma-preferred partner | LPP | 30.6 | 17 | 17 |

| P98172 | Ephrin-B1 | EFNB1 | 23.7 | 5 | 5 |

| Q96D71 | RalBP1-associated Eps domain-containing protein 1 | REPS1 | 11.8 | 8 | 8 |

| Q96IF1 | LIM domain-containing protein ajuba | AJUBA | 16.7 | 7 | 7 |

| Q96J84 | Kin of IRRE-like protein 1 | KIRREL1 | 10.6 | 7 | 7 |

| O43493 | Trans-Golgi network integral membrane protein 2 | TGOLN2 | 30.5 | 13 | 13 |

| Q99523 | Sortilin | SORT1 | 19 | 17 | 17 |

| Q99829 | Copine-1 | CPNE1 | 12.8 | 8 | 8 |

| Q96QA5 | Gasdermin-A | GSDMA | 18.4 | 7 | 7 |

| Q9BZF1 | Oxysterol-binding protein-related protein 8 | OSBPL8 | 13.3 | 12 | 12 |

| Q9H223 | EH domain-containing protein 4 | EHD4 | 16.6 | 7 | 6 |

| Q9H4M9 | EH domain-containing protein 1 | EHD1 | 23.6 | 11 | 7 |

| Q9UBC2 | Epidermal growth factor receptor substrate 15-like 1 | EPS15L1 | 16 | 12 | 12 |

| Q9UDY2 | Tight junction protein ZO-2 | TJP2 | 10.3 | 9 | 9 |

| Q9UEY8 | Gamma-adducin | ADD3 | 12.3 | 8 | 8 |

| Q9UH65 | Switch-associated protein 70 | SWAP70 | 13.8 | 8 | 8 |

| Q9UHB6 | LIM domain and actin-binding protein 1 | LIMA1 | 24.5 | 17 | 17 |

| Q9BRK3 | Matrix remodeling-associated protein 8 | MXRA8 | 14.5 | 8 | 8 |

| Q9UMX0 | Ubiquilin-1 | UBQLN1 | 31.1 | 10 | 5 |

| Q9UNF0 | Protein kinase C and casein kinase substrate in neuron protein 2 | PACSIN2 | 33.7 | 16 | 15 |

| Q9UPT5 | Exocyst complex component 7 | EXOC7 | 15.6 | 11 | 11 |

| Q14254 | Flotillin-2 | FLOT2 | 23.4 | 10 | 10 |

| P08138 | Tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 16 | NGFR | 11.9 | 4 | 4 |

| Q9Y6I3 | Epsin-1 | EPN1 | 13.7 | 4 | 4 |

| P35232 | Prohibitin | PHB | 43.4 | 10 | 10 |

| P62491 | Ras-related protein Rab-11A | RAB11A | 31.5 | 7 | 6 |

| P63000 | Ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 1 | RAC1 | 38 | 7 | 7 |

| P80723 | Brain acid-soluble protein 1 | BASP1 | 75.3 | 9 | 9 |

| Q9P0L0 | Vesicle-associated membrane protein-associated protein A | VAPA | 22.9 | 5 | 4 |

| Q9Y696 | Chloride intracellular channel protein 4 | CLIC4 | 30 | 4 | 4 |

List of proteins screened according to the Gene Ontology cellular localization in the membrane. The UniProt ID, the protein and gene names, the sequence coverage (%), and the number of identified peptides are also reported. The proteins identified also in the experiment with the competitor are highlighted in bold.

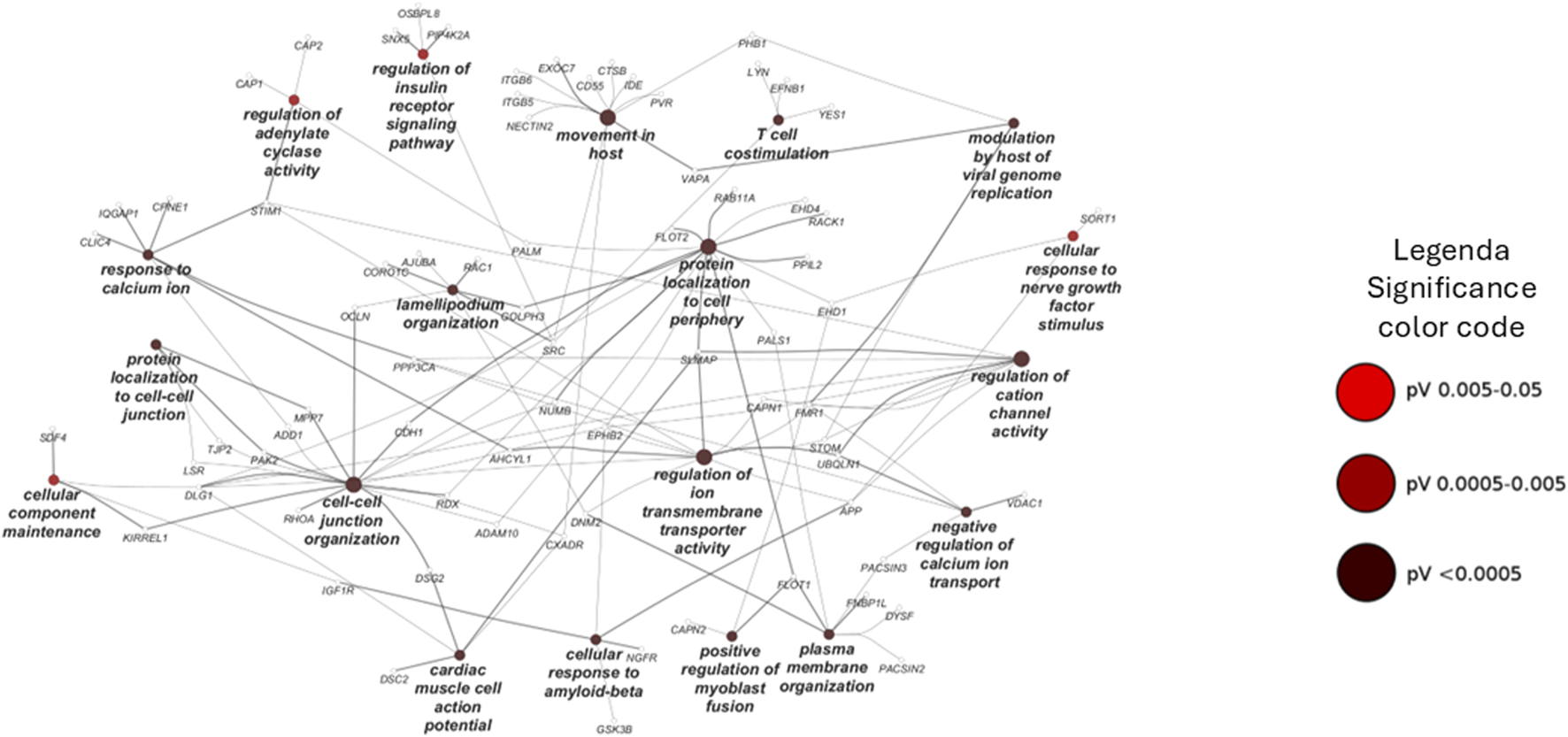

3.3 Functional clustering analysis

Cell compartment enrichment analysis was carried out using Funrich 3.1.3 software by querying the Gene Ontology database. The Benjamini–Hochberg-adjusted p-value (FDR) and fold enrichment cutoffs were 0.001 and 3, respectively. The biological process over-representation analysis was performed using the ClueGO 2.5.7 app of the Cytoscape platform (FDR < 0.05), and the functional clustering analysis is represented in Figure 5.

FIGURE 5

Pathways enrichment analysis through ClueGO based on the biological process database. Network representation of the enriched pathway in the chemical pulldown experiment. The node sizes are proportional to the FDR values.

3.4 Positive chronotropic and inotropic effects induced by 6-ND in Langendorff’s preparation

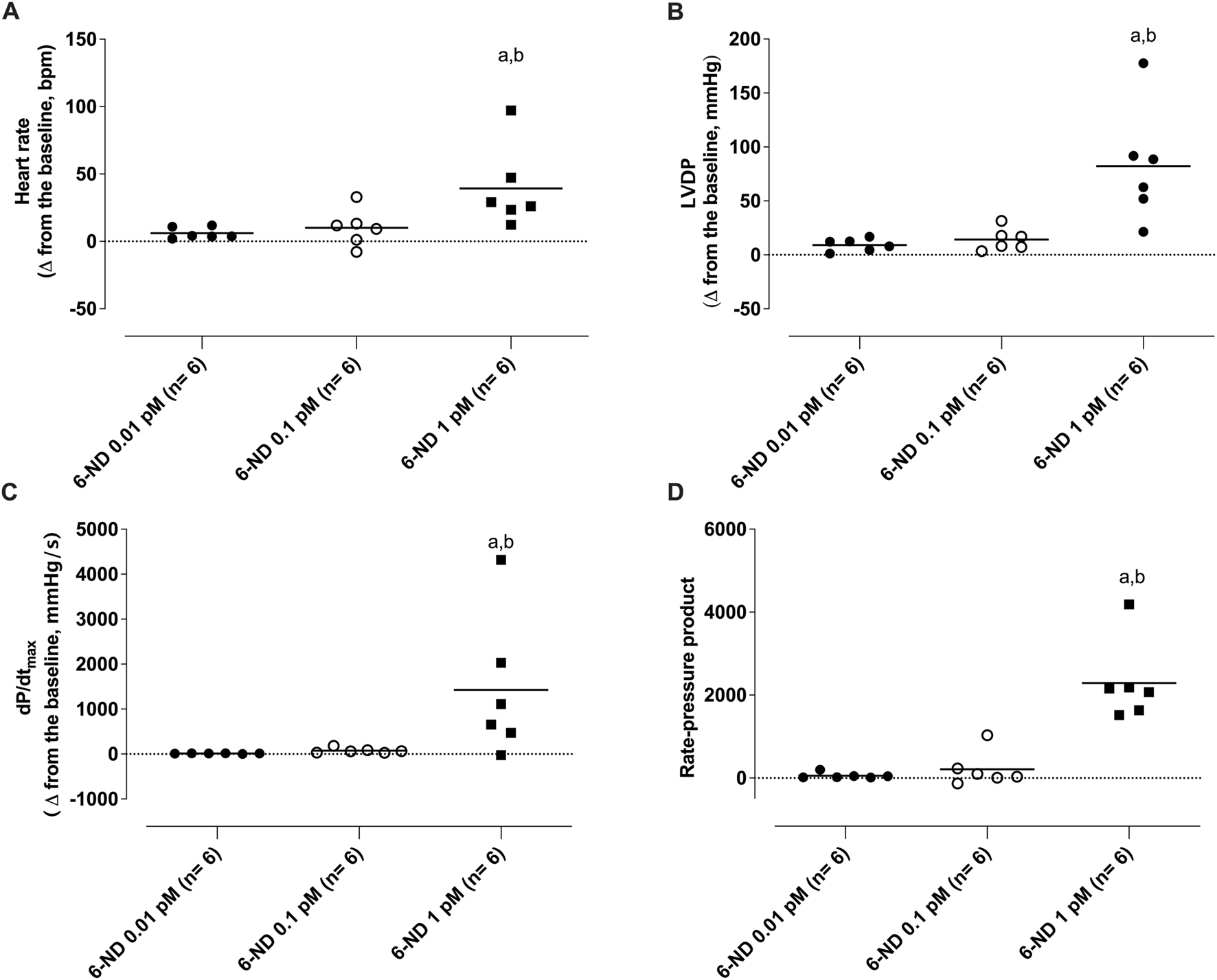

At low concentrations, 6-nitrodopamine (0.01 and 0.1 pM) had no chronotropic and/or inotropic effect. However, at a higher concentration (1 pM), 6-ND infusion significantly increased the heart rate (Figure 6A), LVDP (Figure 6B), dP/dt (max) (Figure 6C), and RPP (Figure 6D).

FIGURE 6

Effect of 1-min infusion of 6-nitrodopamine (6-ND) in the heart rate (HR, (A)), left ventricular developed pressure (LVDP, (B)), maximum rate of pressure development (dP/dtmax, (C)), and rate pressure product (RPP, (D)). aP < 0.05 compared with the lowest concentration of 6-ND (0.01 pM) in each panel; bP < 0.05 compared with the second concentration of 6-ND (0.1 pM) in each panel. NA, noradrenaline.

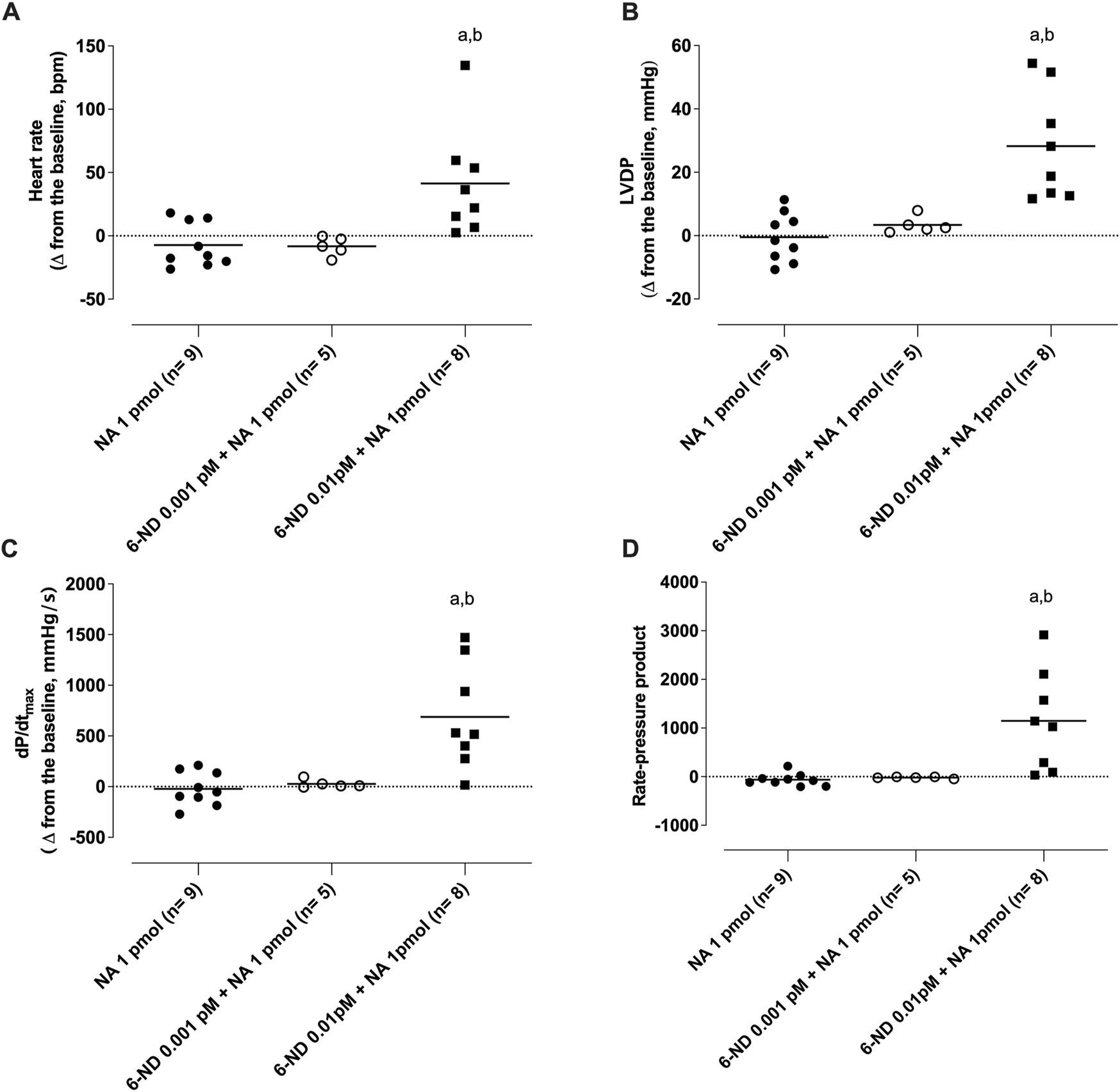

3.5 Interactions of 6-nitrodopamine with noradrenaline on the isolated rat heart (Langendorff’s preparation)

Bolus injection of noradrenaline (1 pmol) had no effect on the heart rate frequency (Figure 7A), LVDP (Figure 7B), dPdt (max) (Figure 7C), and RPP (Figure 7D). One-min infusion of 6-nitrodopamine (0.001 pM) alone did not alter any of these parameters either. However, infusion of 6-nitrodopamine (0.01 pM) significantly increased the heart rate frequency (Figure 7A), LVDP (Figure 7B), dP/dt (max) (Figure 7C), and RPP (Figure 7D) when noradrenaline (1 pmol) was injected at the end of the infusion (1 min).

FIGURE 7

Interaction of 6-nitrodopamine (6-ND) with noradrenaline (NA) on the heart rate ((A)), left ventricular developed pressure (LVDP, (B)), maximum rate of pressure development (dP/dtmax, (C)), and rate pressure product (RPP, (D)). One-minute infusion (100 mL/min) of 6-ND (0.001 or 0.01 pM; right panels) was performed in the absence and presence of a single bolus of noradrenaline (1 pmol). ANOVA, followed by the Newman–Keuls post-test, was applied. aP < 0.05 compared with the NA 1 pmol in each panel; bP < 0.05 compared with the 6-ND 0.001 pM + NA 1 pmol.

4 Discussion

Mammalian hearts express β1- and β2-adrenoceptor subtypes, both of which are involved in the increases in tissue cAMP due to AC activation (Brodde, 2007). Catecholamines such as noradrenaline and adrenaline bind to G-protein–β adrenoceptors, releasing the stimulatory G-protein subunit (Gas) inside the cardiomyocyte, activating AC (Motiejunaite et al., 2021). The generated cAMP binds to protein kinase A (PKA)–R subunits, leading to PKA activation (Liu et al., 2022). Increased PKA activity increases Ca2+ levels, leading to enhanced cardiac muscle contractility. Our study using the Langendorff’s preparation clearly demonstrated that 1-min infusion of the perfused heart with a very low concentration of 6-ND (0.1 pM) markedly potentiated the positive chronotropic and inotropic responses induced by noradrenaline. Thus, these pharmacological data seem to be of great value in identifying the 6-ND receptor. Because cAMP-activated PKA is a central regulator of heart chronotropism and inotropism, it is possible that remarkable potentiation caused by 6-ND could be due to AC pathway activation.

The 116 proteins were identified as potential receptors for this novel endogenous catecholamine by using a chemical proteomics approach based on the affinity purification procedure coupled to mass spectrometry for protein identification. The experiments were performed to purify and identify the cardiomyocyte membrane proteins, obtained from cell lysates, bound to 6-ND agarose and inhibited by the selective 6-ND antagonist 4-nitropropranolol (Sparaco et al., 2022; Oliveira et al., 2024a). The number is not surprising since the ligand concentration (in the micromolar or millimolar range) is high to facilitate protein uptake. The AP-MS-based methods present many advantages; they are not time-consuming, do not require the use of specific tools such as antibodies, and allows direct identification of proteins without any bias or prediction. However, it entails limitations since it is an in vitro method, and therefore, it can lead to identification of physically real but not physiologically meaningful interactions (Ziegler et al., 2013). Furthermore, false-positive interacting proteins can be extracted upon binding with matrix or with the linker between the beads and the molecule, which can also partially affect the binding process (Tabana et al., 2023). Nevertheless, this approach remains one of the most widely used preliminary and unbiased exploration strategies for exploring protein–ligand interactions and characterizing protein binders to small molecules in various contexts (Babak et al., 2015; Smith et al., 2023; Saltzman et al., 2024). A similar affinity purification method was used to identify dopamine targets in a human embryo kidney cell line (HEK293; Weigert Muñoz et al., 2023). A comparison of the 205 interactors identified in this study with the 869 interactors here reported revealed 30 common proteins. It is worth mentioning that CAP-1, CAP-2, and STIM-1 were absent in the dopamine interactomes.

In the rat isolated right atrium, 6-ND, as a positive chronotropic agent, is 100 times more potent than noradrenaline and adrenaline and 10,000 times more potent than dopamine (Britto-Júnior et al., 2022). As a positive inotropic agent in the rat isolated heart, 6-ND was 1,000 times more potent than noradrenaline and 10,000 times more potent than adrenaline (Britto-Júnior et al., 2022). Thus, the results of the functional pharmacological approaches are of paramount importance to identify the 6-ND receptor.

One distinct characteristic of 6-ND action in the heart, as compared to the classical catecholamines, is its remarkable ability to potentiate the positive chronotropic (Britto-Júnior et al., 2022) and inotropic (Britto-Júnior et al., 2023a) effects induced by noradrenaline, adrenaline, and dopamine and, as shown here, the positive inotropic effect induced by noradrenaline. As mentioned above, binding to transmembrane β-adrenoceptors, to stimulate cAMP-dependent PKA activation in cardiomyocytes, is considered the initial step in cardiomyocyte activation by the classical catecholamines (Liu et al., 2022). It is unlikely that 6-ND acts as a partial agonist on β-adrenoceptors since the increases in the atrial rate induced by PDE-3 inhibitors such as dipyridamole, cilostazol, and milrinone are virtually abolished by pre-incubation with 6-ND, whereas those induced by dopamine, noradrenaline, and adrenaline are unaffected (Britto-Júnior et al., 2023a). Another finding that indicates a lack of effect on β-adrenoceptors is that the pre-incubation of the atria with the protein kinase inhibitor H-89 abolished the increases in the heart rate induced by dopamine, noradrenaline, and adrenaline but only attenuated the increase induced by 6-ND (Britto-Júnior et al., 2023a). The absence of adrenoceptor proteins bound to the 6-ND agarose under our experimental conditions is notable. Thus, modulation of cAMP levels could be a mechanism by which 6-ND could synergize with the classical catecholamines.

Cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases (PDEs) modulate cyclic nucleotide signaling by degrading cAMP and 3′,5′-cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP). There are 11 PDE superfamilies [PDE1–11 (Bender and Beavo, 2006)], and the heart/myocytes express mRNA for all but PDE6 (Hashimoto et al., 2018). The major PDE expressed by human cardiomyocytes is PDE1C (Bork et al., 2023), which is a dual PDE substrate, metabolizing both cAMP and cGMP. Inhibition of PDE3 and PDE4 activity increases the atrial rate (Dolce et al., 2021), and PDE1 inhibition enhances cardiomyocyte contractility through a PKA-dependent mechanism (Muller et al., 2021). Therefore, considering that 6-ND does not increase cAMP levels in human platelets (Nash et al., 2022) and of the 817 cardiomyocyte proteins that are bound to 6-ND, none were identified as cAMP- or cGMP-PDE signaling, advocating that 6-ND does not directly modulate PDE activity. It is interesting that the three membrane proteins directly involved in the modulation of AC, namely, cyclase associated protein-1 (CAP-1; Kakurina et al., 2018), CAP-2 (Pelucchi et al., 2023), and STIM-1 (El Assar et al., 2022), are bound to 6-ND agarose, with the binding selectively blocked by 4-nitropropranol, being candidates for the 6-ND receptor.

Purification of the adenylyl cyclase complex from the yeasts Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Field et al., 1990) and Schizosaccharomyces pombe (Kawamukai et al., 1992) identified the presence of a 70-kDA protein (CAP), whose amino-terminal domain is associated with the AC catalytic area. This protein interaction with AC allows the enzyme to respond appropriately to its regulatory proteins (Vojtek and Cooper, 1993). Homologs for CAP1 and CAP2 have been identified in Homo sapiens (Matviw et al., 1992; Yu et al., 1994) and in Rattus norvegicus (Swiston et al., 1995); however, the patterns of CAP1 and CAP2 expression varied significantly in adult rat tissues. Interestingly, mRNA levels for CAP2 were significantly higher than those for CAP1 in the rat heart (Swiston et al., 1995).

CAP-1 binds and activates adenylyl cyclase in mammalian cells (Zhang et al., 2021). In PCCL3 thyroid follicular cells, overexpression of CAP-1 caused a marked leftward shift in the forskolin dose–response curve, whereas negative modulation of CAP-1 resulted in a significant rightward shift (Zhang et al., 2021). It is interesting that although 6-ND potentiates the positive chronotropic effect of classical catecholamines, it strongly reduces the positive chronotropic (Kaumann et al., 2009) and inotropic (Christ et al., 2009) effects induced by PDE3 inhibitors, indicating a dual ability to modulate AC. Ablation of CAP2 in mice causes dilated cardiomyopathy associated with severe reduction in the heart rate (Peche et al., 2013). It is interesting that the two human CAP proteins are distinct enough to suggest that they may have different regulatory roles (Yu et al., 1994). Whether they have different ability to modulate AC in the heart is under current investigation. Direct quantification of cAMP levels following stimulation with 6-ND and classical catecholamines may yield additional insights into 6-ND signaling within cardiomyocytes. Furthermore, silencing CAP-1 and CAP-2 mRNA expressions should elucidate the modulatory functions of these proteins in the mechanism of action of 6-ND.

Stromal interaction protein (STIM1) is expressed in cardiomyocytes (Liu et al., 2023) and has a single transmembrane domain (Hooper et al., 2000); it is located in the sarcoplasmic reticulum and plasma membrane (Soboloff et al., 2012), and it is also associated with adenylyl cyclase activation (Motiani et al., 2018). Changes in cytosolic Ca2+ levels are known to either enhance or depress cAMP production through various Ca2+-sensitive AC isoforms (Willoughby et al., 2012). Of the nine transmembrane AC isoforms described so far, AC1 and AC8 are the major Ca2+-activated isoforms, whereas AC5 and AC6 are subjected to direct inhibition by physiological Ca2+ in the cytosol. Cardiac-specific deletion of STIM1 in mice causes a reduction in the heart rate and sinus arrest, together with a potentiation of the autonomic response to cholinergic signaling (Zhang et al., 2016). Although the negative chronotropism is compatible with the lack of the 6-ND effect, there is no evidence that 6-ND potentiates cholinergic effects (Oliveira et al., 2024b). It is interesting that STIM1 can also act as a Ca2+ sensor by activating store-operated calcium channels (SOCCs) following sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ store depletion (Zhang et al., 2005). STIM1 can bind Ca2+ under resting conditions, but, after store depletion, STIM1 can interact with Orai channels to activate the store-operated Ca2+ entry (Rosenberg et al., 2021), raising the possibility that 6-ND may modulate calcium transport. Indeed, one of the identified interactors with 6-ND is dysferlin, a 238-kDa transmembrane protein with multiple Ca2+-binding domains, which mediates Ca2+-dependent membrane fusion in striated muscle cells. Dysferlin-knockout (KO) mice develop a dilated cardiomyopathy characterized by decreased left ventricular ejection fraction and reduced heart rate (Paulke et al., 2024). Although both cardiac phenotypes are compatible with a reduction in 6-ND action, our findings that potentiation by 6-ND on catecholamine action on rat perfused heart is also observed in smooth muscle (Britto-Júnior et al., 2023a) and that the expression of dysferlin is restricted to the skeletal muscle (Chernova et al., 2022) exclude dysferlin as the primary 6-ND target in the heart. Indeed, the cardiac phenotypes in dysferlin-KO mice only become evident in mice over 32 weeks of age (Paulke et al., 2024), whereas the effects reported here are observed acutely. Calpains are 6-ND interactors; they constitute a conservative family of Ca2+-dependent intracellular cysteine proteases commonly expressed in all cells (Goll et al., 2003). Two ubiquitous forms of calpains have been identified (Taneike et al., 2011), namely, m- (CAP1) and m-(CAP2), which are activated by micromolar and millimolar calcium concentrations, respectively. Calpain-1 is the primary isoform expressed in cardiomyocytes (Zhang et al., 2024) and plays a critical role in normal heart function by cleaving several target proteins (Patterson et al., 2011). Both Capn1 and Capn2 are heterodimers presenting an 80-kDa catalytic subunit and a common 28-kDa regulatory subunit (calpain 4). Although cardiac-specific deletion of calpain 4 resulted in decreased protein levels of Capn1 and Capn2, no cardiac phenotypes under baseline conditions were observed, a finding not compatible with the acute effects reported here for 6-ND.

Noradrenaline is rapidly degraded by momoamino oxidases (Manzoor and Hoda, 2020), and inhibition of these enzymes by 6-ND could cause potentiation of the inotropic effect of NA. However, 6-ND caused 20% and 30% of inhibition of MAO-A and MAO-B, respectively, at 1 mM; at 100 nM, no inhibition of either enzyme was observed (Fuguhara et al., 2025). Inhibition of catecholamine uptake by 6-ND could potentiate both the positive chronotropic and inotropic effects induced by classical catecholamines. Transporter-mediated uptake plays a major role in determining both the magnitude and duration of the catecholamine effect (Gasser, 2021). There are two types of monoamine transporters, namely, a high-affinity with low capacity to transport monoamines, such as NET (Engelhartet et al., 2020), a low-affinity with high capacity like organic cation transporters (OCT 1–3, Amphoux et al., 2006; Bacq et al., 2012), and the plasma membrane monoamine transporter (PMAT; Torres et al., 2003; Engel et al., 2004). However, it is unlikely that 6-ND could interact with catecholamine uptake since, in our experimental settings, none of these proteins were bound to the 6-ND-derivatized agarose.

The use of human-induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes is associated with some constraints, such as limited capacity to evaluate contractility, altered maturation properties, and reduced survivability (Shead et al., 2024). Purification of the 6-ND receptor from rat neonatal ventricular myocytes may provide further indication of the importance of the cyclase-associated proteins CAP-1 and CAP-2.

5 Conclusion

6-Nitrodopamine-induced potentiation of the catecholamines’ chronotropic and inotropic effects is due to the modulation of adenylyl cyclase activity, probably via direct interactions with CAP-1 and CAP-2.

Statements

Data availability statement

The data presented in the study are deposited in the PRIDE repository, accession number PXD066711.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the studies on humans in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements because only commercially available established cell lines were used. The animal study was approved by the Ethics Committee in Animal Use of UNICAMP. The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

IC: Investigation, Writing – review and editing. VM: Investigation, Writing – review and editing. JB-J: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. ATL: Investigation, Writing – review and editing. EA: Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. ASP: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. II: Investigation, Writing – review and editing. FC: Investigation, Writing – review and editing. MM: Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. SP: Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. GD: Investigation, Writing – review and editing. EC: Investigation, Writing – review and editing. ADS: Investigation, Writing – review and editing. AC: Investigation, Writing – review and editing. FeF: Investigation, Writing – review and editing. FrF: Investigation, Writing – review and editing. VS: Investigation, Writing – review and editing. BS: Investigation, Writing – review and editing. RS: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – review and editing. PC: Investigation, Writing – original draft. SV: Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. GC: Conceptualization, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. GDN: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. Financial support was received by Sao Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) grants 2021/14414-8 (JB-J.), 2021/13593-6 (ATL), 2017/15175-1 (EA), and 2019/16805-4 (GDN) and the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) grant 303839/2019-8 (GDN).

Acknowledgments

Charles Nash PhD edited the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphar.2025.1597035/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Figure S1SDS-PAGE of proteins eluted from the chemical pulldown (lane PD) and from the pre-clearing (lane PC). The molecular weight markers are also reported.

Supplementary Figure S2Western blot assays for the verification of the fractionated lysis.

Glossary

- 6-ND

6-Nitrodopamine

- AC

Adenylyl cyclase

- CAP-1

Cyclase-associated protein 1

- CAP-2

Cyclase-associated protein 2

- STIM1

Stromal interaction molecule 1

- hiPSCs

Human-induced pluripotent stem cells

- SDS-PAGE

Sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- GAPDH

Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- HCOOH

Formic acid

- ACN

Acetonitrile

- DDA

Data-dependent acquisition

- CRAPome

Contaminant Repository for Affinity Purification

- FDR

False discovery rate

- LVEDP

Left ventricular end-diastolic pressure

- LVDP

Left ventricular developed pressure

- LVSP

Left ventricular systolic pressure

- HR

Heart rate

- RPP

Rate pressure product

- +dP/dtmax

Maximum rate of pressure development

- SEM

Standard error of the mean

- ANOVA

Analysis of variance

- NaCl

Sodium chloride

- KCl

Potassium chloride

- CaCl2

Calcium chloride

- MgSO4

Magnesium sulfate

- NaHCO3

Sodium bicarbonate

- KH2PO4

Potassium phosphate mono-basic

- PC lane

Pre-clearing lane

- PD lane

Pulldown lane

- PKA

Protein kinase A

- PDE

Phosphodiesterase

- cGMP

Cyclic guanosine monophosphate

- UPLC

Ultra performance liquid chromatography

- PMAT

Plasma membrane monoamine transporter

- NET

Norepinephrine transporter

- OCT

Organic cation transporter

- SOCCs

Store-operated calcium channels

References

1

AmphouxA.VialouV.DrescherE.BrüssM.Mannoury La CourC.RochatC.et al (2006). Differential pharmacological in vitro properties of organic cation transporters and regional distribution in rat brain. Neuropharmacology50 (8), 941–952. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2006.01.005

2

BabakM. V.MeierS. M.HuberK. V. M.ReynissonJ.LeginA. A.JakupecM. A.et al (2015). Target profiling of an antimetastatic RAPTA agent by chemical proteomics: relevance to the mode of action. Chem. Sci.6 (4), 2449–2456. 10.1039/c4sc03905j

3

BacqA.BalasseL.BialaG.GuiardB.GardierA. M.SchinkelA.et al (2012). Organic cation transporter 2 controls brain norepinephrine and serotonin clearance and antidepressant response. Mol. Psychiatry17 (9), 926–939. 10.1038/mp.2011.87

4

BenderA. T.BeavoJ. A. (2006). Cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases: molecular regulation to clinical use. Pharmacol. Rev.58 (3), 488–520. 10.1124/pr.58.3.5

5

BindeaG.MlecnikB.HacklH.CharoentongP.TosoliniM.KirilovskyA.et al (2009). ClueGO: a cytoscape plug-in to decipher functionally grouped gene ontology and pathway annotation networks. Bioinformatics25 (8), 1091–1093. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp101

6

BorkN. I.SubramanianH.KurelicR.NikolaevV. O.RybalkinS. D. (2023). Role of phosphodiesterase 1 in the regulation of real-time cGMP levels and contractility in adult mouse cardiomyocytes. Cells12 (23), 2759. 10.3390/cells12232759

7

Britto-JúniorJ.de OliveiraM. G.Dos Reis GatiC.CamposR.MoraesM. O.MoraesM. E. A.et al (2022). 6-NitroDopamine is an endogenous modulator of rat heart chronotropism. Life Sci.307, 120879. 10.1016/j.lfs.2022.120879

8

Britto-JúniorJ.LimaA. T.FuguharaV.MonicaF. Z.AntunesE.De NucciG. (2023a). Investigation on the positive chronotropic action of 6-nitrodopamine in the rat isolated atria. Naunyn Schmiedeb. Arch. Pharmacol.396 (6), 1279–1290. 10.1007/s00210-023-02394-9

9

Britto-JúniorJ.LimaA. T.FuguharaV.DassowL. C.Lopes-MartinsR. Á. B.CamposR.et al (2023b). 6-Nitrodopamine is the most potent endogenous positive inotropic agent in the isolated rat heart. Life (Basel)13 (10), 2012. 10.3390/life13102012

10

BroddeO. E. (2007). Beta-adrenoceptor blocker treatment and the cardiac beta-adrenoceptor-G-protein(s)-adenylyl cyclase system in chronic heart failure. Naunyn Schmiedeb. Arch. Pharmacol.374 (5-6), 361–372. 10.1007/s00210-006-0125-7

11

ChernovaO. N.ChekmarevaI. A.MavlikeevM. O.YakovlevI. A.KiyasovA. P.DeevR. V. (2022). Structural and ultrastructural changes in the skeletal muscles of dysferlin-deficient mice during postnatal ontogenesis. Ultrastruct. Pathol.46 (4), 359–367. 10.1080/01913123.2022.2105464

12

ChristT.Galindo-TovarA.ThomsM.RavensU.KaumannA. J. (2009). Inotropy and L-type Ca2+ current, activated by beta1- and beta2-adrenoceptors, are differently controlled by phosphodiesterases 3 and 4 in rat heart. Br. J. Pharmacol.156 (1), 62–83. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2008.00015.x

13

DavisR. P.CasiniS.van den BergC. W.HoekstraM.RemmeC. A.DambrotC.et al (2012). Cardiomyocytes derived from pluripotent stem cells recapitulate electrophysiological characteristics of an overlap syndrome of cardiac sodium channel disease. Circulation125 (25), 3079–3091. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.066092

14

Di BaldassarreA.D’AmicoM. A.IzzicupoP.GaggiG.GuarnieriS.MariggiòM. A.et al (2018). Cardiomyocytes derived from human CardiopoieticAmniotic fluids. Sci. Rep.8 (1), 12028. 10.1038/s41598-018-30537-z

15

DolceB.ChristT.Grammatika PavlidouN.YildirimY.ReichenspurnerH.EschenhagenT.et al (2021). Impact of phosphodiesterases PDE3 and PDE4 on 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor4-mediated increase of cAMP in human atrial fibrillation. Naunyn Schmiedeb. Arch. Pharmacol.394 (2), 291–298. 10.1007/s00210-020-01968-1

16

El AssarM.García-RojoE.Sevilleja-OrtizA.Sánchez-FerrerA.FernándezA.García-GómezB.et al (2022). Functional role of STIM-1 and Orai1 in human microvascular aging. Cells11 (22), 3675. 10.3390/cells11223675

17

EngelK.ZhouM.WangJ. (2004). Identification and characterization of a novel monoamine transporter in the human brain. J. Biol. Chem.279, 50042–50049. 10.1074/jbc.M407913200

18

EngelhartD. C.GranadosJ. C.ShiD.SaierM. H.JrBakerM. E.AbagyanR.et al (2020). Systems biology analysis reveals eight SLC22 transporter subgroups, including OATs, OCTs, and OCTNs. Int. J. Mol. Sci.21 (5), 1791. 10.3390/ijms21051791

19

FieldJ.XuH. P.MichaeliT.BallesterR.SassP.WiglerM.et al (1990). Mutations of the adenylyl cyclase gene that block RAS function in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Science247 (4941), 464–467. 10.1126/science.2405488

20

FonsekaP.PathanM.ChittiS. V.KangT.MathivananS. (2021). FunRich enables enrichment analysis of OMICs datasets. J. Mol. Biol.433 (11), 166747. 10.1016/j.jmb.2020.166747

21

FuguharaV.De OliveiraM. G.Aguiar da SilvaC. A.GuazzelliP. R.PetersonL. W.De NucciG. (2025). Cardiovascular effects of 6-nitrodopamine, adrenaline, noradrenaline, and dopamine in normotensive and hypertensive rats. Front. Pharmacol. 16, 1557997. 10.3389/fphar.2025.1557997

22

GasserP. J. (2021). Organic cation transporters in brain catecholamine homeostasis. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol.266, 187–197. 10.1007/164_2021_470

23

GollD. E.ThompsonV. F.LiH.WeiW.CongJ. (2003). The calpain system. Physiol. Rev.83 (3), 731–801. 10.1152/physrev.00029.2002

24

GuellichA.MehelH.FischmeisterR. (2014). Cyclic AMP synthesis and hydrolysis in the normal and failing heart. Pflugers Arch.466 (6), 1163–1175. 10.1007/s00424-014-1515-1

25

HashimotoT.KimG. E.TuninR. S.AdesiyunT.HsuS.NakagawaR.et al (2018). Acute enhancement of cardiac function by phosphodiesterase type 1 inhibition. Circulation138 (18), 1974–1987. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.030490

26

HooperJ. D.ScarmanA. L.ClarkeB. E.NormyleJ. F.AntalisT. M. (2000). Localization of the mosaic transmembrane serine protease corin to heart myocytes. Eur. J. Biochem.267 (23), 6931–6937. 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2000.01806.x

27

IacobucciI.La MannaS.CipolloneI.MonacoV.CanèL.CozzolinoF. (2023). From the discovery of targets to delivery systems: how to decipher and improve the metallodrugs’ actions at a molecular level. Pharmaceutics15 (7), 1997. 10.3390/pharmaceutics15071997

28

IacobucciI.MonacoV.CanèL.BibbòF.CioffiV.CozzolinoF.et al (2022). Spike S1 domain interactome in non-pulmonary systems: a role beyond the receptor recognition. Front. Mol. Biosci.9, 975570. 10.3389/fmolb.2022.975570

29

IaconisD.MontiM.RendaM.van KoppenA.TammaroR.ChiaravalliM.et al (2017). The centrosomal OFD1 protein interacts with the translation machinery and regulates the synthesis of specific targets. Sci. Rep.7 (1), 1224. 10.1038/s41598-017-01156-x

30

ItzhakiI.MaizelsL.HuberI.GepsteinA.ArbelG.CaspiO.et al (2012). Modeling of catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia with patient-specific human-induced pluripotent stem cells. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol.60 (11), 990–1000. 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.02.066

31

KakurinaG. V.KolegovaE. S.KondakovaI. V. (2018). Adenylyl cyclase-associated protein 1: structure, regulation, and participation in cellular processes. Biochem. (Mosc).83 (1), 45–53. 10.1134/S0006297918010066

32

KaumannA. J.Galindo-TovarA.EscuderoE.VargasM. L. (2009). Phosphodiesterases do not limit beta1-adrenoceptor-mediated sinoatrial tachycardia: evidence with PDE3 and PDE4 in rabbits and PDE1-5 in rats. Naunyn Schmiedeb. Arch. Pharmacol.380 (5), 421–430. 10.1007/s00210-009-0445-5

33

KawamukaiM.GerstJ.FieldJ.RiggsM.RodgersL.WiglerM.et al (1992). Genetic and biochemical analysis of the adenylyl cyclase-associated protein, cap, in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Mol. Biol. Cell3 (2), 167–180. 10.1091/mbc.3.2.167

34

KellerS. H.PlatoshynO.YuanJ. X. (2005). Long QT syndrome-associated I593R mutation in HERG potassium channel activates ER stress pathways. Cell Biochem. Biophys.43 (3), 365–377. 10.1385/CBB:43:3:365

35

LiuP.YangZ.WangY.SunA. (2023). Role of STIM1 in the regulation of cardiac energy substrate preference. Int. J. Mol. Sci.24 (17), 13188. 10.3390/ijms241713188

36

LiuY.ChenJ.FontesS. K.BautistaE. N.ChengZ. (2022). Physiological and pathological roles of protein kinase A in the heart. Cardiovasc. Res.118 (2), 386–398. 10.1093/cvr/cvab008

37

ManzoorS.HodaN. (2020). A comprehensive review of monoamine oxidase inhibitors as Anti-Alzheimer’s disease agents: A review. Eur. J. Med. Chem.206, 112787. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112787

38

MatviwH.YuG.YoungD. (1992). Identification of a human cDNA encoding a protein that is structurally and functionally related to the yeast adenylyl cyclase-associated CAP proteins. Mol. Cell Biol.12 (11), 5033–5040. 10.1128/mcb.12.11.5033-5040.1992

39

MellacheruvuD.WrightZ.CouzensA. L.LambertJ. P.St-DenisN. A.LiT.et al (2013). The CRAPome: a contaminant repository for affinity purification-mass spectrometry data. Nat. Methods10 (8), 730–736. 10.1038/nmeth.2557

40

MotianiR. K.TanwarJ.RajaD. A.VashishtA.KhannaS.SharmaS.et al (2018). STIM1 activation of adenylyl cyclase 6 connects Ca2+ and cAMP signaling during melanogenesis. EMBO J.37 (5), e97597. 10.15252/embj.201797597

41

MotiejunaiteJ.AmarL.Vidal-PetiotE. (2021). Adrenergic receptors and cardiovascular effects of catecholamines. Ann. Endocrinol. Paris.82 (3-4), 193–197. 10.1016/j.ando.2020.03.012

42

MullerG. K.SongJ.JaniV.WuY.LiuT.JeffreysW. P. D.et al (2021). PDE1 inhibition modulates Cav1.2 channel to stimulate cardiomyocyte contraction. Circ. Res.129 (9), 872–886. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.121.319828

43

NashC. E. S.AntunesN. J.Coelho-SilvaW. C.CamposR.De NucciG. (2022). Quantification of cyclic AMP and cyclic GMP levels in Krebs-Henseleit solution by LC-MS/MS: application in washed platelet aggregation samples. J. Chromatogr. B Anal. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci.1211, 123472. 10.1016/j.jchromb.2022.123472

44

OliveiraD. L.CardosoV. F.Britto-JúniorJ.FuguharaV.FrecenteseF.SparacoR.et al (2024a). The negative chronotropic effects of (±)-propranolol and (±)-4-NO2-propranolol in the rat isolated right atrium are due to blockade of the 6-nitrodopamine receptor. Naunyn Schmiedeb. Arch. Pharmacol.9. 10.1007/s00210-024-03463-3

45

OliveiraM. G.Britto-JuniorJ.Martins DiasD. R.PereiraL. G. S.ChiavegattoS.HermawanI.et al (2024b). Neurogenic-derived 6-nitrodopamine is the most potent endogenous modulator of the mouse urinary bladder relaxation. Nitric Oxide153, 98–105. 10.1016/j.niox.2024.10.010

46

PalinskiW.MontiM.CamerlingoR.IacobucciI.BocellaS.PintoF.et al (2021). Lysosome purinergic receptor P2X4 regulates neoangiogenesis induced by microvesicles from sarcoma patients. Cell Death Dis.12 (9), 797. 10.1038/s41419-021-04069-w

47

PattersonC.PortburyA. L.SchislerJ. C.WillisM. S. (2011). Tear me down: role of calpain in the development of cardiac ventricular hypertrophy. Circ. Res.109 (4), 453–462. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.239749

48

PaulkeN. J.FleischhackerC.WegenerJ. B.RiedemannG. C.CretuC.MushtaqM.et al (2024). Dysferlin enables tubular membrane proliferation in cardiac hypertrophy. Circ. Res.135 (5), 554–574. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.124.324588

49

PecheV. S.HolakT. A.BurguteB. D.KosmasK.KaleS. P.WunderlichF. T.et al (2013). Ablation of cyclase-associated protein 2 (CAP2) leads to cardiomyopathy. Cell Mol. Life Sci.70 (3), 527–543. 10.1007/s00018-012-1142-y

50

PelucchiS.MacchiC.D'AndreaL.RossiP. D.SpecianiM. C.StringhiR.et al (2023). An association study of cyclase-associated protein 2 and frailty. Aging Cell22 (9), e13918. 10.1111/acel.13918

51

Percie du SertN.AhluwaliaA.AlamS.AveyM. T.BakerM.BrowneW. J.et al (2020). Reporting animal research: explanation and elaboration for the ARRIVE guidelines 2.0. PLoS Biol.18 (7), e3000411. 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000411

52

PundirS.MartinM. J.O’DonovanC.UniProt Consortium (2016). UniProt tools. Curr. Protoc. Bioinforma.53, 1.29.1–1.29.15. 10.1002/0471250953.bi0129s53

53

RosenbergP.ZhangH.BrysonV. G.WangC. (2021). SOCE in the cardiomyocyte: the secret is in the chambers. Pflugers Arch.473 (3), 417–434. 10.1007/s00424-021-02540-3

54

SaltzmanA. B.ChanD. W.HoltM. V.WangJ.JaehnigE. J.AnuragM.et al (2024). Kinase inhibitor pulldown assay (KiP) for clinical proteomics. Clin. Proteomics21 (1), 3. 10.1186/s12014-023-09448-3

55

SmithR. J.MilneR.LopezV. C.WiedemarN.DeyG.SyedA. J.et al (2023). Chemical pulldown combined with mass spectrometry to identify the molecular targets of antimalarials in cell-free lysates. STAR Protoc.4 (1), 102002. 10.1016/j.xpro.2022.102002

56

SoboloffJ.RothbergB. S.MadeshM.GillD. L. (2012). STIM proteins: dynamic calcium signal transducers. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol.13 (9), 549–565. 10.1038/nrm3414

57

SparacoR.ScognamiglioA.CorvinoA.CaliendoG.FiorinoF.MagliE.et al (2022). Synthesis, chiral resolution and enantiomers absolute configuration of 4-Nitropropranolol and 7-Nitropropranolol. Molecules28 (1), 57. 10.3390/molecules28010057

58

SheadK. D.HuethorstE.BurtonF.LangN. N.MylesR. C.SmithG. L.et al (2024). Human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes for preclinical cardiotoxicity screening in cardio-oncology. JACC CardioOncol.6 (5), 678–678. 10.1016/j.jaccao.2024.07.012

59

SwistonJ.HubbersteyA.YuG.YoungD. (1995). Differential expression of CAP and CAP2 in adult rat tissues. Gene165 (2), 273–277. 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00522-8

60

TabanaY.BabuD.FahlmanR.SirakiA. G.BarakatK. (2023). Target identification of small molecules: an overview of the current applications in drug discovery. BMC Biotechnol.23 (1), 44. 10.1186/s12896-023-00815-4

61

TaneikeM.MizoteI.MoritaT.WatanabeT.HikosoS.YamaguchiO.et al (2011). Calpain protects the heart from hemodynamic stress. J. Biol. Chem.286 (37), 32170–32177. 10.1074/jbc.M111.248088

62

TorresG. E.GainetdinovR. R.CaronM. G. (2003). Plasma membrane monoamine transporters: structure, regulation and function. Nat. Rev. Neurosci.4 (1), 13–25. 10.1038/nrn1008