Abstract

Introduction:

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) has become a global burden, with inappropriate antibiotic prescribing being an important contributing factor. Antibiotic prescribing guidelines play an important role in improving the quality of antibiotic use, provided they are evidence-based and regularly updated. As a result, they help reduce AMR, which is a critical challenge in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Consequently, the objective of this study was to evaluate local, national, and international antibiotic prescribing guidelines currently available—especially among LMICs—and previous challenges, in light of the recent publication of the WHO AWaRe book, which provides future direction.

Methodology:

Google Scholar and PubMed searches were complemented by searching official country websites to identify antibiotic prescribing guidelines, especially those concerning empiric treatment of bacterial infections, for this narrative review. Data were collected on the country of origin, income level, guideline title, year of publication, development methodology, issuing organization, target population, scope, and coverage. In addition, documentation on implementation strategies, compliance, monitoring of outcome measures, and any associated patient education or counseling efforts were reviewed to assess guideline utilization.

Results/findings:

A total of 181 guidelines were included, with the majority originating from high-income countries (109, 60.2%), followed by lower-middle-income (40, 22.1%), low-income (18, 9.9%), and upper-middle-income (14, 7.7%) countries. The GRADE methodology was used in only 20.4% of the sourced guidelines, predominantly in high-income countries. Patient education was often underemphasized, particularly in LMICs. The findings highlighted significant disparities in the development, adaptation, and implementation of guidelines across different WHO regions, confirming the previously noted lack of standardization and comprehensiveness in LMICs.

Conclusion:

Significant disparities exist in the availability, structure, and methodological rigor of antibiotic prescribing guidelines across countries with different income levels. Advancing the development and implementation of standardized, context-specific guidelines aligned with the WHO AWaRe framework—and supported by equity-focused reforms—can significantly strengthen antimicrobial stewardship and help address the public health challenge of AMR.

1 Introduction

Inappropriate antibiotic usage is now a critical global health issue as it is a leading cause of antimicrobial resistance (AMR), which results in the reduced effectiveness of antimicrobials (Godman et al., 2021; Aldarhami, 2023; Baran et al., 2023; Ho et al., 2024). According to current estimates, AMR causes nearly 1.17 million deaths annually, with the number of deaths likely to more than double by 2050 if key issues and challenges are not addressed (Murray et al., 2022; Do et al., 2023). Infections caused by resistant bacteria increase morbidity and treatment costs, along with higher mortality and the risk of such infections spreading (Dadgostar, 2019; Wagenlehner and Dittmar, 2022; Spellberg et al., 2025; Wan et al., 2025). The impact of AMR is likely to be greater in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where the infection burden is higher and antimicrobial choices and usage are impacted by high levels of patient co-payments (Godman et al., 2021; Sulis et al., 2022; Khan et al., 2024; Lewnard et al., 2024; Sartorius et al., 2024; Saleem et al., 2025a).

In response to this critical public health issue, the World Health Organization (WHO, 2015) developed the Global Action Plan (GAP) on AMR, which led to the creation of National Action Plans (NAPs) aimed at encouraging countries to address the emerging public health threat of AMR (WHO, 2016). The purpose of the NAPs is to facilitate effective policy and stewardship measures to reduce the prevalence of AMR within each country (Godman et al., 2022; Willemsen et al., 2022; Charani et al., 2023). However, there have been concerns regarding the implementation of NAPs, especially in LMICs, due to resource constraints and shortage of trained personnel (Chua et al., 2021; Godman et al., 2022; Ohemu, 2022; Saleem et al., 2022). Notably, the fourth objective of NAPs emphasizes the development and implementation of clinical practice guidelines to promote the appropriate use of antimicrobials. These serve as tools for promoting rational prescribing practices and reducing the inappropriate use of antibiotics within countries. Clinical guidelines can be defined as documents that provide recommendations for clinical practice, aiming to minimize variability in care, particularly when scientific evidence is limited or when multiple therapeutic options are available (Steinberg et al., 2011; Johnson et al., 2021). The development and implementation of evidence-based guidelines support clinical decision-making by enhancing the quality of care, improving patient outcomes, and promoting the efficient use of resources (Sackett et al., 1996). The publication and implementation of antibiotic guidelines are regarded as important educational measures, especially for physicians in LMICs. This is because robust clinical guidelines are believed to significantly improve the quality of antibiotic prescribing across all sectors of care (Cooper et al., 2020; D’Arcy et al., 2021; Foxlee et al., 2021; Akhloufi et al., 2022; Boltena et al., 2023). As a result, adherence to published guidelines is increasingly incorporated into antimicrobial stewardship programs (ASPs) both in hospitals and primary care settings, often as part of agreed quality indicator targets (Versporten et al., 2018; Foxlee et al., 2021; Chigome et al., 2023; Funiciello et al., 2024; Lubanga et al., 2024). ASPs increasingly play a pivotal role in monitoring the implementation of national or regional guidelines to improve clinical outcomes across all sectors while minimizing the consequences of inappropriate antibiotic use (Nathwani et al., 2019; Brinkmann and Kibuule, 2020; Akhloufi et al., 2022; Siachalinga et al., 2022; Haseeb et al., 2023). ASPs in high-income countries (HICs) are often supported by electronic health records (EHRs)—digital systems that store patient medical information and can be integrated with clinical decision support tools. As a result, EHRs facilitate the monitoring of prescribing practices, facilitate audits, and help ensure adherence to national or institutional guidelines as part of ASPs. However, there have been concerns about implementing ASPs in LMICs due to resource limitations and personnel issues shortages; encouragingly, this is now beginning to change despite previous challenges (Cox et al., 2017; Brinkmann and Kibuule, 2020; Godman et al., 2021; Borde et al., 2022; Siachalinga et al., 2022).

Meanwhile, there is often a lack of national AMR surveillance, especially within LMICs, which limits the development of national evidence-based guidelines and the subsequent implementation of targeted policies to improve future antibiotic use (Woolf et al., 1999; Ohemu, 2022; Do et al., 2023; Okolie et al., 2023; Kiggundu et al., 2023; Mustafa et al., 2024). HICs often have access to resources for comprehensive guideline development, including local antimicrobial resistance data, systematic reviews, and advanced methodologies, including GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation) (Barker et al., 2021). Conversely, LMICs frequently rely on expert opinions and internationally derived guidelines to help improve antibiotic prescribing, which may not be well-adapted to local AMR patterns and healthcare contexts. Moreover, due to resource constraints, implementing such guidelines or establishing such programs is more challenging in LMICs. In addition to this, adherence to national or international guidelines remains highly variable, especially across LMICs, leading to inappropriate and excessive use of antibiotics, which may be a reflection of concerns about the local relevance of adapted guidelines (Sulis et al., 2020; Thi et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2022; Mahmudul Islam et al., 2024).

Consequently, there is a need to evaluate the availability and scope of current national and international antibiotic guidelines. It is important to identify disparities in their development, adaptation, and implementation. These insights can inform strategies to improve guideline adherence, particularly by assessing the extent to which local AMR patterns are incorporated into guideline updates. We acknowledge that the WHO AWaRe book has recently been published, covering 35 common infections across healthcare sectors; this builds on the WHO AWaRe classification, which is part of the Essential Medicines List (Moja et al., 2024; WHO, 2022; Sharland et al., 2019). However, this guidance may require local adaption based on local resistance patterns. In addition, many existing local or national guidance may be outdated, highlighting the urgent need for updates—especially in light of the recent United Nations General Assembly (UN-GA) target, which calls for 70% of antibiotics used across sectors to come from the Access group (United Nations, 2024). We are also aware that the WHO AWaRe classification system is increasingly being used across studies, including those conducted in LMICs, to assess current antibiotic use patterns and set targets for ASPs—a trend that is expected to continue (Saleem et al., 2025a; Saleem et al., 2025b).

In view of the rising global threat of AMR, coupled with the variability in national and local antibiotic prescribing practices, the first objective of this review was to assess the availability, scope, and quality of current antibiotic prescribing guidelines across countries of varying income levels, specifically to identify gaps in guideline development and adaptation. This review also aimed to evaluate the degree to which current guidelines incorporate the WHO AWaRe book recommendations and address key components such as patient education, AMR surveillance, and stewardship strategies (Funiciello et al., 2024; Moja et al., 2024). By identifying these gaps and emphasizing the importance of locally adapted, evidence-based guidelines, this review seeks to contribute to ongoing global efforts to optimize antibiotic use, reduce the reliance on broad-spectrum antibiotics, and assist in achieving the NAP goals, especially in LMICs. This is viewed as essential for meeting the UN-GA target of reducing AMR and increasing the use of Access antibiotics (United Nations, 2024).

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study design

This study was conducted as a narrative review to comprehensively analyze antibiotic prescribing guidelines from diverse regions and income-level countries. The main objective was to identify disparities in guideline development, adaptation, and implementation, providing a robust understanding of current practices in antibiotic prescribing at local, national, and international levels. We have used this approach in multiple previous publications (Godman et al., 2021; Godman et al., 2022; Chigome et al., 2023; Haseeb et al., 2023) and believed this design is better suited to the heterogeneity of the included studies and the descriptive goals of the review, especially given the wide variation in regions and income levels included.

2.2 Search strategy

A comprehensive search was conducted between June and September 2024 to identify eligible antibiotic prescribing guidelines. The primary sources for data collection and extraction were Google Scholar and PubMed, alongside other search engines, with most of the data obtained directly from Google and official country websites. We first conducted a PubMed search using MeSH terms and Boolean operators, including “antibiotic prescribing guideline*,” “clinical practice guideline*,” or “antibiotic guideline*” in the title. Subsequently, we used Google as a search engine to locate guidelines not included in the medical literature but available online. This approach was conducted based on the assumption that a significant number of guidelines might be published by scientific societies or governmental agencies and made available on the internet without being captured by formal literature repositories.

We subsequently accessed possible antibiotic prescribing guidelines by analyzing official country websites. The search for guidelines on official country websites was conducted manually using a structured and systematic approach. For every country, the official website of the Ministry of Health, or equivalent national health authority, was identified via a Google search. Furthermore, country-specific AMR National Action Plan pages were examined as they often linked to or referenced available antibiotic prescribing guidelines. This method ensured that both recent and archived guidelines could be identified, even in countries with limited digital infrastructure or non-indexed resources.

2.2.1 Eligibility criteria

A country was included if it had at least one publicly accessible antibiotic prescribing guideline available in English that met the review’s inclusion criteria. Countries were not excluded based on income level or geographic region.

2.2.2 Guideline inclusion criteria

This review focused on bacterial infections and clinical syndromes that are commonly managed with antibiotic therapy. Inclusion criteria encompassed any English-language antibiotic prescribing guidelines from across all income countries that provided specific treatment recommendations, including antibiotic names, dosages, and durations. To ensure a comprehensive overview, local, national, and international guidelines were considered.

2.2.3 Exclusion criteria

Guidelines were excluded if they focused solely on infection prevention or non-antibiotic therapies. Additionally, guidelines that lacked detailed prescribing information, such as those offering only general guidance without specifying antibiotic names, dosages, or durations, were excluded. Finally, documents not published in English were excluded due to translation constraints. In addition, English is recognized as the international scientific language.

2.3 Information sought for each guideline

For each guideline included, we collected general information on the country of origin and its geographic location according to WHO regions and its income classification—i.e., low-income, lower-middle, upper-middle, and high-income—based on the World Bank classification (World Bank, 2025), consistent with our previous reviews (Saleem et al., 2025a; Saleem et al., 2025c). Additional data were extracted on the guideline title, year of publication, development methodology, issuing organization, target population, scope, and extent of local adaptation. We also noted whether the guidelines addressed current AMR patterns and included implementation strategies, compliance and monitoring, outcome measures, and patient education or counseling components. These key variables and their distribution across guidelines are visually summarized in Figure 1. Patient-related data were collected due to their recognized role in influencing antibiotic prescribing and dispensing, especially in LMICs (Nair et al., 2019; Antwi et al., 2020; Khan et al., 2020; Ramdas et al., 2025). Effective patient counseling is increasingly regarded as essential to enhance adherence to prescribed antibiotics, educate patients on the importance of completing treatment courses, and raise awareness of the risks associated with misuse (Saleem et al., 2025a; Saleem et al., 2025c; Balea et al., 2025; Sakeena et al., 2018; Hunter and Owen, 2024).

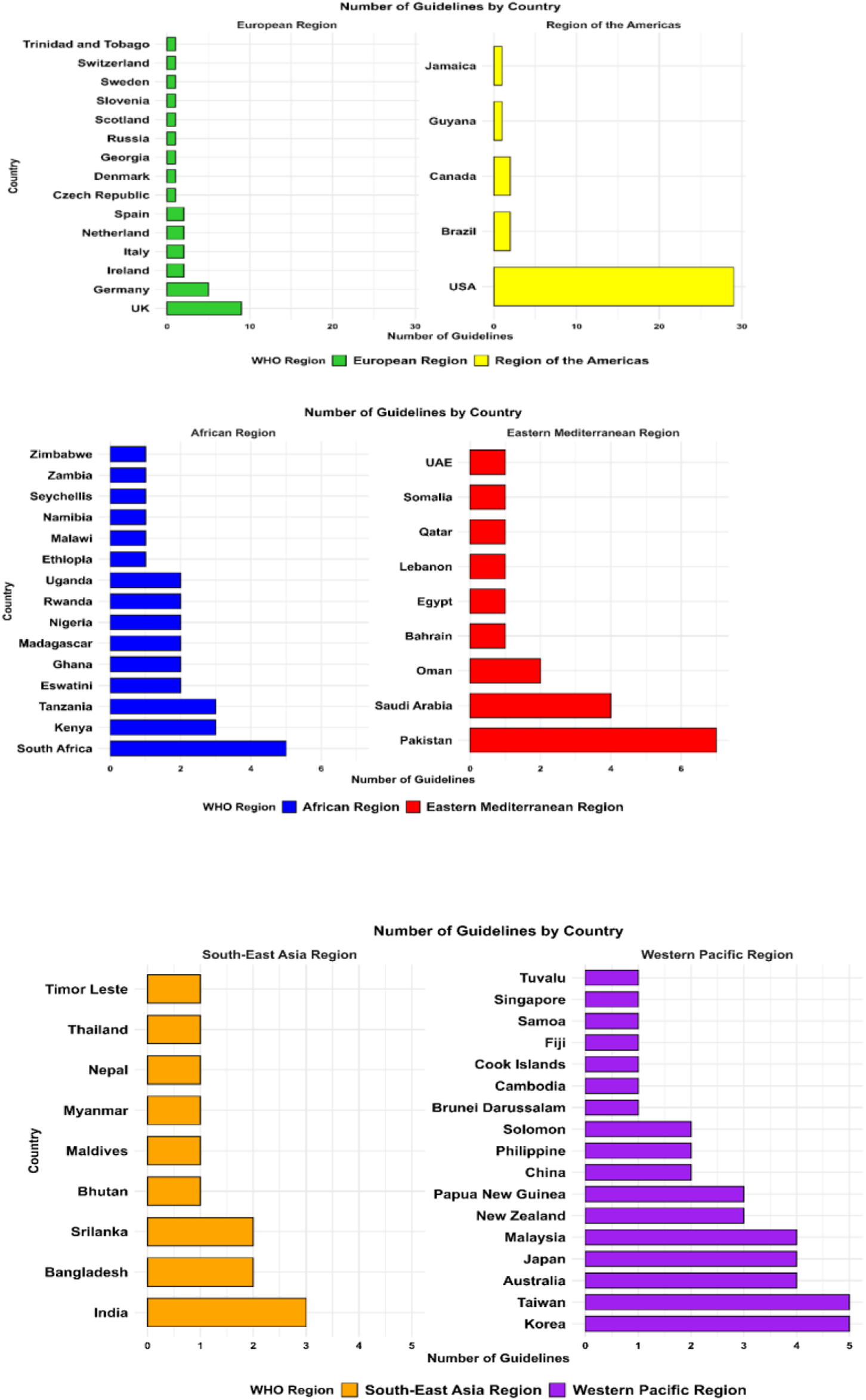

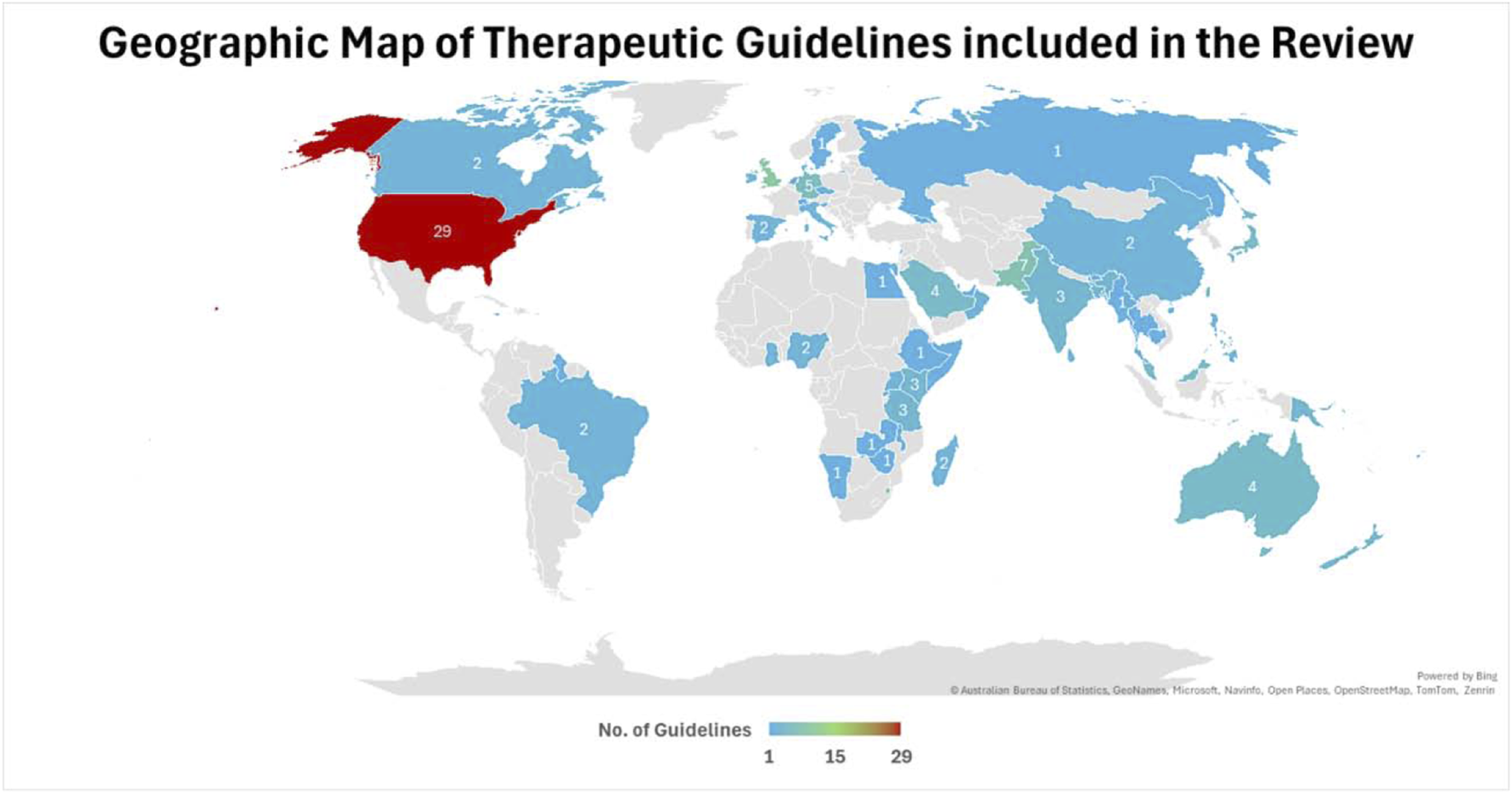

FIGURE 1

Geographical distribution of included antibiotic prescribing guidelines by WHO regions.

As part of our data extraction process, we also assessed whether each guideline utilized a structured evidence-based grading methodology, specifically the GRADE framework. For each guideline, we recorded whether GRADE was explicitly mentioned as part of the guideline development methodology. This included checking the methodology sections of the guidelines for references to GRADE terminology, use of evidence quality ratings (e.g., “low,” “moderate,” and “high” certainty), and the presence of structured recommendation grading. This enabled us to evaluate the extent to which evidence-based approaches were incorporated into the development of antibiotic prescribing guidelines by various country income groups. Each guideline was thoroughly reviewed to determine whether it included information on AMR patterns and patient counseling. As a result, we aimed to provide a thorough evaluation of current antibiotic guidelines and their applicability across various healthcare settings.

For the purpose of this review, a guideline was considered “outdated” if it was published more than 10 years before the date of data collection, i.e., prior to 2014, and showed no evidence of revision, update, or endorsement in more recent policy documents or on websites. This cutoff was chosen based on international best practices, which recommend regular updates to clinical guidelines every 3–5 years to ensure alignment with evolving evidence, AMR trends, and AMS practices.

2.4 Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was not needed for this study as we included only readily available published material and no patients were involved in the study.

3 Results

We retrieved 335 antibiotic prescribing guidelines, with the majority of data obtained directly from Google and official country websites. Of these, 181 guidelines met our inclusion criteria, provided sufficient information for our review, and were subsequently described in detail. Figure 2 illustrates the guideline selection process.

FIGURE 2

Flow diagram illustrating the process of identification, screening, eligibility assessment, and inclusion of antibiotic prescribing guidelines reviewed in this study.

The general characteristics of the included antibiotic prescribing guidelines are summarized in Table 1 and Supplementary Table S1.

TABLE 1

| Characteristic | Number of guidelines (% total) |

|---|---|

| Income group | |

| HICs | 109 (60.22) |

| UMICs | 14 (7.73) |

| LMICs | 40 (22.10) |

| LICs | 18 (9.94) |

| Global | |

| European guidelines | 13 (7.18) |

| WHO regions | |

| African Region | 29 (16) |

| Eastern Mediterranean Region | 19 (10.5) |

| European Region | 31 (17.13) |

| Region of the Americas | 35 (19.3) |

| Southeast Asia Region | 13 (7) |

| Western Pacific Region | 41 (23) |

| Scope | |

| International | 45 (24.86) |

| National | 116 (64.09) |

| Local | 20 (11.05) |

| Grade methodology used | |

| Yes | 37 (20.44) |

| No | 144 (79.56) |

Characteristics of included guidelines in the review.

NB: HIC, high-income country; UMIC, upper-middle income country; LMIC, lower-middle income country; and LIC, low-income country.

3.1 Distribution by income group and WHO region

Most guidelines (n = 109; 60.2%) originated from HICs, followed by lower-middle-income countries with 40 guidelines (22.1%), low-income countries (LICs) with 18 guidelines (9.9%), and upper-middle-income countries with 14 guidelines (7.7%). The geographical distribution also varied significantly, with the European Region and the Region of the Americas contributing the majority of guidelines, while the African and Southeast Asian regions were underrepresented. Figure 3 illustrates the geographical distribution of antibiotic prescribing guidelines among the countries worldwide.

FIGURE 3

Geographical distribution of included antibiotic prescribing guidelines among the countries.

3.2 Methodological approaches and use of GRADE

Out of the 181 guidelines, only 37 (20.4%) explicitly referenced the use of the GRADE framework. The majority of these were from HICs, reflecting higher methodological standards and resources for evidence synthesis (Jackson et al., 2020; NICE CAP Guideline, 2019a; Autore et al., 2023; Sanford Guideline, 2024). For example, the UK’s NICE and the USA’s IDSA guidelines extensively apply the GRADE methodology to support transparency and methodological rigor (NICE Guidelines, 2023; Tamma et al., 2024).

In contrast, most guidelines from LMICs relied on expert consensus or non-transparent development processes, often lacking structured grading of recommendations (Bartlett et al., 1998; BSMMU Guideline Bangladesh, 2023; Antibiotic Guidelines Myanmar, 2019). For example, guidelines from Pakistan and Bhutan primarily relied on literature reviews without systematic evidence-based grading, resulting in broad recommendations (MMIDSP Guideline, 2022; Ministry of Health Bhutan, 2018). Details are mentioned in Table 2 and Supplementary Table S2.

TABLE 2

| Global guidelines | Guideline abbreviation | Publication date | Methodology | Prepared by | Scope | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Europe | EAU GUIDELINES UI | 2024 | Evidence-based review and expert consensus | EAU | International | Bonkat et al. (2017) |

| ESCMID ED ST Guidelines | 2024 | Evidence-based review and expert consensus | ESCMID and EAHP | International | Schoffelen et al. (2024) | |

| ERS/ESICM/ESCMID/ALAT CAP-Guidelines | 2023 | GRADE | ERS/ESICM/ESCMID/ALAT | National | Martin-Loeches et al. (2023) | |

| ESCMID–EUCIC Guidelines | 2019 | Evidence-based review and expert consensus | ESCMID and EUCIC | International | Tacconelli et al. (2019) | |

| ERS guidelines for AB | 2017 | GRADE | ERS | International | Polverino et al. (2017) | |

| ERS-HAP/VAP Guidelines | 2017 | GRADE | ERS/ESICM/ESCMID/ALAT | International | Torres et al. (2017) | |

| ESCMID Meng. Guidelines | 2016 | GRADE | Microbiology ESCMID | International | Van de Beek et al. (2016) | |

| ESMO-febrile neutropenia | 2016 | GRADE | ESMO | International | Klastersky et al. (2016) | |

| Blue Book | 2016 | Evidence-based review and expert consensus | OUP and ESPID | International | Butler (2016) | |

| ESC-Endocarditis-G | 2015 | Evidence-based expert consensus | ESC-EACTS and EANM | International | Habib et al. (2016) | |

| EAU/ESPU-UTI | 2015 | Literature review (evidence-based) | EAU/ESPU | International | Stein et al. (2015) | |

| EAU UTI Guidelines | 2014 | GRADE | EAU | International | Debast et al. (2014) | |

| ESCMID-ST Guidelines | 2012 | GRADE | ESCMID/ESCMID STG | International | Pelucchi et al. (2012) |

| Income level | Country | Guideline abbreviation | Publication date | Methodology | Prepared by | Scope | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| African Region | ||||||||

| HIC | Seychelles | Seychelles STGs | 2003 | Combined local medical practice experience with relevant international standards | MOH | National | Ministry of Health Seychelles (2003) | |

| UMIC | Namibia | Namibia STG | 2011 | Evidence based guidelines | MOH and SC | National | Ministry of Health Namibia (2011) | |

| LMIC | Eswatini | Eswatini STG-EML 2020 | 2020 | Evidence-based recommendations aligned with WHO EML | MOH | National | Ministry of Health Eswatini (2020) | |

| Eswatini STG-EML 2012 | 2012 | Evidence-based guidelines | MOH | National | Ministry of Health Eswatini (2012) | |||

| Ghana | Ghana COVID-19 STG | 2020 | Evidence-based review, expert consensus, and local AMR | MOH | National | Ministry of Health Ghana (2020) | ||

| GNDP STG | 2017 | Based on evidence quality RCTs, clinical studies, and expert opinions | MOH | National | Ministry of Health Ghana (2017a) | |||

| Kenya | Kenya AMS Guidelines | 2020 | Based on AMS spectrum, development, and implementation of systems and interventions | MOH | National | Ministry of Health Kenya (2020) | ||

| Kenya AMS Protocol | 2020 | Multiregional stepwise stewardship intervention: 18-month ASP adaptation | KNRF | Local | Gitaka et al. (2020) | |||

| Kenya AMS Guidelines | 2012 | GRADE | MMS | National | Agweyu et al. (2012) | |||

| Nigeria | Nigeria ICU Guidelines | 2023 | Based on evidence-based published data and local prospective antibiograms | Expert Committee | National | Oladele et al. (2023) | ||

| Nigeria STG | 2016 | Evidence-based guidelines | MOH | National | Ministry of Health Nigeria (2016) | |||

| Tanzania | STG/NEMLIT | 2021 | NEMLIT new edition aligns with WHO recommendations | MOH/CD | National | Ministry of Health Tanzania (2021) | ||

| AMS Policy Guidelines | 2020 | Evidence-based recommendations aligned with WHO AMR Action Plan and local data | MOH | National | Ministry of Health Tanzania (2020) | |||

| STG-NEMLIT | 2017 | Evidence-based recommendations, expert consensus, and local AMR data | MOH | National | Ministry of Health Tanzania (2017) | |||

| Zambia | ENC Guidelines | 2014 | Evidence-based guidelines | MCD/MCH | National | Ministry of Health Zambia (2014) | ||

| LIC | Ethiopia | Ethiopia PH STGs | 2014 | Evidence-based recommendations aligned with WHO EML and local disease burden | MOH | National | Ministry of Health Ethiopia (2014) | |

| Malawi | MSTG 5th Edition | 2015 | Evidence-based guidelines | MOH | National | Ministry of Health Malawi (2015) | ||

| Madagascar | (Madagascar IG) Guide | 2020 | Evidence-based, expert consensus, and local disease burden | Ministry of Public Health | National | Ministry of Health Madagascar (2020) | ||

| Antibiotika Tsara | 2018 | Digital tool combining local AMR data and stewardship algorithms | SPIM | Local | SPIM. Antibiotika Tsara (2018) | |||

| Rwanda | Rwanda Guidelines | 2022 | Based on available evidence and literature review | MOH | National | Ministry of Health Rwanda (2022) | ||

| Rwanda COVID-19 Guidelines | 2020 | Evidence-based expert consensus in alignment with WHO recommendations | RBC | National | Ministry of Health Rwanda (2020) | |||

| South Africa | SA Hospital AMR Guidelines | 2023 | Policy framework aligned with WHO and national AMR action plans | NDH | National | Department of Health South Africa (2023) | ||

| Africa CDC Guidelines | 2021 | Evidence-based expert consensus in alignment with local AMR data | Africa CDC and OHT | International | African Union (2021) | |||

| AMPATH Guidelines | 2017 | Laboratory-driven, local antibiograms and diagnostic protocols | AMPATH | National | AMPATH Antibiotic Guide (2017) | |||

| SA CAP Guidelines | 2017 | Evidence-based expert consensus | SATC | National | Boyles et al. (2017) | |||

| SAASP Pocket Guide | 2014 | Evidence-based expert consensus and local resistance data | SAASP | National | SAASP (2014) | |||

| Uganda | Uganda Clinical Guidelines | 2023 | Evidence-based expert consensus | MOH | National | Ministry of Health Uganda (2023) | ||

| Uganda Guidelines | 2020 | Ugandan approach combines WHO guidance, national policies, and local innovation | MOH | National | Ministry of Health Uganda (2020) | |||

| Zimbabwe | EDLIZ Guidelines | 2015 | Evidence-based guidelines | NMTPAC/MOH | National | Ministry of Health Zimbabwe (2015) | ||

| Eastern Mediterranean Region | ||||||||

| HIC | Bahrain | TG and pathways | 2022 | Evidence-based guidelines | NHRA | National | NHRA Bahrain (2022) | |

| Oman | Oman AMS Guidelines | 2016 | Evidence-based recommendations and expert consensus aligned with international standards | MOH | National | Ministry of Health Oman (2016) | ||

| Oman SAP Guidelines | 2015 | National Antimicrobial Subcommittee (surgical team practice-based) | MOH | National | Ministry of Health Oman (2015) | |||

| Qatar | Qatar CAP Guidelines | 2016 | Evidence-based recommendations aligned with WHO standards | MOH | National | Ibrahim (2016) | ||

| Saudi Arabia | UTI infection protocol | 2023 | Evidence-based recommendations aligned with IDSA, WHO, and local AMR | MOH | National | Ministry of Health Saudi Arabia (2023) | ||

| Lower RTI protocol | 2020 | Evidence-based expert consensus | MOH | National | Ministry of Health Saudi Arabia (2020) | |||

| NAT-G for CAP–HAP Adults | 2018 | Evidence-based selection and local epidemiology of antimicrobial resistance | MOH | National | Ministry of Health Saudi Arabia (2018) | |||

| Saudi CAP In adults | 2017 | Evidence-based recommendations, expert consensus, and literature review | SPIDS | National | Alzomor et al. (2017) | |||

| UAE | UAE IAI Guidelines | 2022 | Evidence-based recommendations aligned with local AMR data | N-ASC | National | Ministry of Health UAE (2022) | ||

| LMIC | Egypt | Egypt Preauthorization Guidelines | 2022 | Based on Egyptian Hospital Antimicrobial Data | EDA/NARC | National | Egypt Drug Authority Guideline (2022) | |

| Lebanon | LSIDCM CAP Guidelines | 2014 | Evidence-based recommendations adapted to Lebanese local AMR | LSIDCM | National | Moghnieh et al. (2014) | ||

| Pakistan | ||||||||

| Bahria Hospital Guidelines | 2023 | Hospital formulary and stewardship-driven recommendations | BIH | Local | Bahria International Hospital Guideline (2023) | |||

| Typhoid Management Guidelines | 2022 | Evidence-based local resistance surveillance and expert consensus | MMIDSP | National | MMIDSP Guideline (2022) | |||

| DRAP Guidelines | 2022 | Regulatory framework aligned with WHO Global Action Plan on AMR | DRAP | National | DRAP Guidelines (2022) | |||

| PCS COPD Guideline | 2020 | Evidence-based | PCS | Local | Pakistan Chest Society Guideline (2020) | |||

| MMIDSP IDSP and PARN Guidelines | 2019 | Evidence-based recommendations and expert consensus | MMIDSP IDSP/PARN | Local | IDSP and PARN Guidelines (2019) | |||

| PCS Guidelines for CAP in adults | 2017 | Evidence-based expert consensus and local resistance data | PCS | National | Bokhari et al. (2017) | |||

| SGP Pakistan | 2015 | Evidence-based locally adapted sepsis management | AKU | Local | Hashmi et al. (2015) | |||

| LIC | Somalia | Somali STGs | 2015 | Evidence-based data aligned with WHO EML | MOH | National | Ministry of Health Somalia (2015) | |

| European Region | ||||||||

| HIC | Czech Republic | Czech CDI Guidelines | 2022 | Evidence-based guideline updated version | DID | Local | Beneš et al. (2022) | |

| Denmark | Danish Antibiotic Guidelines | 2013 | Evidence-based practices, laboratory testing, and rational use of antibiotics | DHMA | National | Danish Health and Medicine Authority Guidelines (2013) | ||

| Germany | German LRTI Guidelines | 2024 | Clinical experts collaborated on recommendations | GSPID/AWMF | National | Mauritz et al. (2024) | ||

| Pediatric CAP Guidelines | 2020 | Evidence-based review and expert consensus | PCAP-DGPI/GPP | National | Rose et al. (2020) | |||

| German ABS Guidelines | 2016 | Evidence-based grading according to the AWMF Guidance Manual | GSID | International | De With et al. (2016) | |||

| GT Guidelines | 2015 | Evidence-based review, expert consensus | GSO and HNS | National | Windfuhr et al. (2016) | |||

| German CAPNETZ Guidelines | 2009 | Key points based on the Oxford Center for evidence-based structures | Paul-Ehrlich-SC, GRS, GSI, and CAPNETZ | National | Höffken et al. (2009) | |||

| Ireland | CHI-Antimicrobial Guidelines | 2020 | Evidence-based recommendations, local resistance data, and expert consensus | CHI | National | CHI Guideline Ireland (2020) | ||

| PiPc children Guidelines | 2016 | Two-round modified Delphi consensus method | DGP RCS/CPRG | Local | Barry et al. (2016) | |||

| Italy | UTI-Ped-ER Guidelines | 2023 | GRADE | UTI-Ped-ER | Local | Autore et al. (2023) | ||

| SITA-SIP COVID-19 Guidelines | 2021 | GRADE | SITA/SIP | National | Bassetti et al. (2021) | |||

| Netherlands | SWAB CAP Guidelines | 2024 | GRADE | SWAB/NVALT | National | Guideline Netherlands (2024) | ||

| CDSS-Antibiotics-2022 | 2022 | Developed CDSS for empirical antibiotic therapy, involving stakeholders | Erasmus MC and UMC | Local | Akhloufi et al. (2022) | |||

| Russia | COPD Guidelines | 2018 | Evidence-based review and expert consensus | RRS | National | Aisanov et al. (2018) | ||

| Scotland | CDI Guidelines | 2014 | Evidence-based recommendations and expert consensus | NHS, HPN, and HPS | National | Health Protection Scotland (2014) | ||

| Slovenia | Slovenia Neurosurgical Guidelines | 2014 | Evidence-based recommendations for neurosurgical prophylaxis | SMA | National | Slovenian Guidelines (2014) | ||

| Spain | MSF Clinical Guidelines | 2024 | Evidence-based, context-adapted protocols for resource-limited settings | MSF | International | MSF Clinical guidelines (2024) | ||

| V Spanish Consensus Guidelines | 2022 | Systematic review of scientific evidence, Delphi process, and GRADE | VSCC | National | Gisbert et al. (2022) | |||

| Sweden | Swedish CAP Guidelines | 2012 | Evidence-based review and expert consensus | SSID | National | Spindler et al. (2012) | ||

| Switzerland | Swiss PAP Guidelines | 2022 | Evidence-based, database-informed surgical prophylaxis | PIGS | National | Paioni et al. (2022) | ||

| Trinidad and Tobago | T&T ARI Guidelines | 2020 | GRADE | MOH | National | Nagassar (2020) | ||

| UK | GMMMG Guidelines | 2024 | Evidence-based | GM HCCM | Local | Greater Manchester (2024) | ||

| BSW ICB Guidelines | 2024 | Evidence-based | BSW-ICB | Local | BSW ICB Guidelines UK (2024) | |||

| Pneumonia NICE Guidelines | 2023 | GRADE | NICE | International | NICE Guidelines (2023) | |||

| BTS Guidelines | 2020 | GRADE | BTS | National | Smith et al. (2020) | |||

| UK BASH HIV NG | 2020 | Evidence-based review and expert consensus | BASHH | National | Chirwa et al. (2021) | |||

| AMP Dentistry-GPG | 2020 | GRADE | FDS-RCS | National | GP Guidelines UK (2020) | |||

| HAP NICE Guidelines | 2019 | Evidence-based review and expert consensus | NICE | International | NICE HAP Guideline (2019) | |||

| CAP-APG | 2019 | GRADE | NICE | International | NICE CAP Guideline (2019) | |||

| BSAC Guidelines ED | 2012 | Evidence-based review, expert consensus | BSAC | National | Gould et al. (2012b) | |||

| UMIC | Georgia | GPAS CAP Guidelines | 2023 | Evidence-based review and expert consensus | Children’s healthcare | National | Georgia Pediatric Antibiotic Stewardship (2023) | |

| Region of the Americas | ||||||||

| HIC | Canada | CCPG-rhinosinusitis | 2011 | Evidence-based review and expert consensus | CSOHNS and CRWG | National | Desrosiers et al. (2011) | |

| CA-MRSA-2006 | 2006 | Evidence-based review and expert consensus | CMA and CIDS | Local | Barton et al. (2006) | |||

| United States | IDSA Guidelines | 2024 | GRADE | IDSA | International | Tamma et al. (2024) | ||

| Sanford-VAP | 2024 | Evidence-based recommendations | Jay P. Sanford | International | Sanford Guideline (2024) | |||

| CDC-Antibiotic- | 2024 | Evidence-based practices and expert consensus | CDC | National | CDC Guidelines (2024) | |||

| SCCM-corticosteroids | 2024 | GRADE | SCCM | international | Chaudhuri et al. (2024) | |||

| IWGDF/IDSA-DFI | 2023 | GRADE | IWGDF and IDSA | International | Senneville et al. (2024) | |||

| Michigan UTI Guidelines | 2021 | Evidence-based review and expert consensus | MHHA | International | MHHA Guideline (2021) | |||

| AAP-Red Book- | 2021 | GRADE | AAP | International | Red Book (2021) | |||

| IWGDF/IDSA-DFI | 2020 | GRADE | (IWGDF/IDSA | International | Lipsky et al. (2020) | |||

| ATS CAP Guideline | 2019 | GRADE | ATS &IDSA | International | Jackson et al. (2020) | |||

| IDSA OPAT Guidelines | 2018 | GRADE | IDSA | International | Norris et al. (2019) | |||

| IDSA Diarrhea | 2018 | GRADE | IDSA | International | Randel (2018) | |||

| IDSA/SHEA CDI Guidelines | 2017 | GRADE | IDSA/SHEA | International | McDonald et al. (2018) | |||

| Adult and pediatric APG | 2017 | Evidence-based and systematic review consensus | DOH | National | CDC (2017) | |||

| AAO-HNS-OME | 2016 | Evidence-based review and expert consensus | AAO-HNS | International | Rosenfeld et al. (2016) | |||

| ACG-diarrhea- | 2016 | Evidence-based review and expert consensus | ACG | International | Riddle et al. (2016) | |||

| ACP/CDC-ARTI | 2016 | Evidence-based practices | ACP/CDC | National | Bredemeyer (2016) | |||

| AAO-HNS Guidelines | 2015 | GRADE | AAO-HNS | International | Rosenfeld et al. (2015) | |||

| IDSA-SSTI-Guidelines | 2014 | Evidence-based review and expert consensus | IDSA | International | Stevens et al. (2014) | |||

| ASHP-surgical | 2013 | GRADE | ASHP, IDSA, SIS, and SHEA | International | Bratzler et al. (2013) | |||

| IDSA ABRS Guidelines | 2012 | GRADE | IDSA | International | Chow et al. (2012) | |||

| AAP-UTI | 2011 | GRADE | AAP | International | Roberts et al. (2011) | |||

| CAP Guidelines PIDS/IDSA | 2011 | GRADE | PIDS and IDSA | International | Bradley et al. (2011) | |||

| ACC/AHA-IE- | 2008 | Evidence-based and expert consensus | ACC/AHA | International | Nishimura et al. (2008) | |||

| AAO-HNS-sinusitis- | 2007 | Evidence-based recommendations | AAO-HNS | International | Rosenfeld et al. (2007) | |||

| ACCP CG | 2006 | GRADE | ACCP | International | Braman (2006) | |||

| IDSA GAS-pharyngitis | 2002 | Evidence-based systematic review consensus | IDSA | International | Bisno et al. (2002) | |||

| IDSA-ID- | 2001 | Evidence-based systematic review consensus | IDSA | International | Guerrant et al. (2001) | |||

| AAP-CPG-sinusitis | 2001 | Evidence-based systematic review consensus | AAP | National | Pediatrics (2001) | |||

| IDSA CAP Guidelines | 1998 | Expert consensus and literature review | CID and IDSA | International | Bartlett et al. (1998) | |||

| UMIC | Brazil | Brazilian CAP Guidelines | 2009 | Evidence-based recommendations, expert consensus, and literature review | BTS | National | Corrêa et al. (2009) | |

| Brazilian CAP Guidelines | 2004 | Evidence-based recommendations and expert consensus | BSP | National | Nascimento-Carvalho and Souza-Marques (2004) | |||

| Guyana | Guyana STG | 2015 | Evidence-based recommendations, expert consensus, and local AMR | MOH | National | Ministry of Health Guyana (2015) | ||

| Jamaica | Jamaican UTI Guidelines | 2018 | Evidence-based review and expert consensus | JKKF | National | Young Peart et al. (2018) | ||

| Southeast Asia Region | ||||||||

| UMIC | Maldives | Maldives NAMSP | 2020 | National policy framework for antimicrobial stewardship and resistance control | MOH | National | Ministry of Health Maldives (2020) | |

| Thailand | Asthma Guidelines | 2022 | Evidence-based | TAC | National | Kawamatawong et al. (2022) | ||

| Bangladesh | BSMMU Guidelines | 2023 | Evidence-based recommendations aligned with local antibiograms | BSMMU/WHO | National | BSMMU Guideline Bangladesh (2023) | ||

| Bangladesh STG | 2021 | Evidence-based protocols aligned with WHO standards | MOH | National | Ministry of Health Bangladesh (2021a) | |||

| AP for BIRDEM Hospital | 2021 | Hospital-specific recommendations based on local AMR data and expert consensus | BGH | Local | BIRDEM Hospital Bangladesh (2021) | |||

| LMIC | Bhutan | Bhutan-ABG | 2018 | Evidence-based review and expert consensus | MOH | National | Ministry of Health Bhutan (2018) | |

| Timor-Leste | Antibiotic Guidelines HNG | 2016 | Evidence based guidelines | HNGV | National | Hospital Guidelines Timor Leste (2016) | ||

| India | Indian ICU-IC Guidelines | 2019 | Evidence-based recommendations, systematic reviews, and expert consensus | ICMR/CCS | Local | Kulkarni et al. (2019) | ||

| ICU Antibiotic Guidelines | 2019 | Evidence-based expert consensus aligned with local AMR data | ISCCM | National | Khilnani et al. (2019) | |||

| India AMR Guidelines | 2016 | Evidence-based protocols aligned with WHO GAP | NCDC/MOH | National | Ministry of Health Guideline India (2016) | |||

| Myanmar | Myanmar NOGTH Guidelines | 2019 | Evidence-based recommendations aligned with WHO standards to combat AMR | GTH and WHO | Local | Antibiotic Guidelines Myanmar (2019) | ||

| Sri Lanka | Sri Lanka AMR Guidelines | 2024 | Evidence-based guidelines | SCM/MOH/NIM | National | Ministry of Health Srilanka (2016) | ||

| SLMA Guidelines | 2014 | Evidence-based guidelines | SLMA | National | SLMA Guidelines (2014) | |||

| Western Pacific Region | ||||||||

| HIC | Australia | TG Antibiotic Guidelines | 2024 | Evidence-based recommendations | TGL | National | Therapeutic Guidelines Australia (2024) | |

| CHQ-P Antibiocard | 2024 | Initial treatment recommendations, AS, daily review, and TDM. | CHQ-P | Local | CHQHospital. Children (2022) | |||

| SAP Guidelines | 2021 | Evidence-based review and expert consensus | Govt. SAAGAR | Local | SAP Guideline Australia (2021) | |||

| KHA-CARI UTI Guidelines | 2015 | GRADE | KHA-CARI | National | McTaggart et al. (2015) | |||

| Brunei Darussalam | Brunei Darussalam GAPP | 2019 | Stewardship-focused recommendations and expert consensus aligned with WHO standards | MOH | National | Ministry of health Brunei Darussalam (2019) | ||

| Cook Islands | Cook Islands-ABG | 2023 | Evidence-based local AMR data | MOH | National | Ministry of Health Cook Islands (2023) | ||

| Japan | JGA CD Guidelines | 2023 | Evidence-based recommendations, expert consensus, and local data | JGA | National | Ihara et al. (2024) | ||

| JSSI Guidelines | 2021 | GRADE Delphi method | JSSI | International | Ohge et al. (2021) | |||

| Japan AMS Manual | 2017 | Evidence-based recommendations, expert consensus, and RCTS. | MOH/LWHSBT/IDCD | National | Ministry of Health Japan (2017) | |||

| JRS CAP Guidelines | 2006 | Evidence-based recommendations, expert consensus, and local data | JRS | National | Miyashita et al. (2006) | |||

| Korea | Korean AGE Guidelines | 2019 | GRADE | KSID/KSAD | National | Kim et al. (2019) | ||

| Korean UTI Guidelines | 2018 | Evidence-based local resistance and expert consensus | KSID | National | Kang et al. (2018) | |||

| KGU-CAP- | 2018 | Evidence-based review and expert consensus | KGU | National | Lee et al. (2018) | |||

| KGU-ARTI | 2017 | Evidence-based review, expert consensus | KGU | National | Yoon et al. (2017) | |||

| Korea BJI Guidelines | 2014 | GRADE | KSC | National | Korean Society for Chemotherapy et al. (2014) | |||

| New Zealand | BPACnzprimary care AG | 2024 | Evidence-based review, expert consensus, and local AMR | BPACnz | Local | bpacnz Guide New Zealand (2024) | ||

| BPACnz-ABGuide | 2017 | Evidence-based review and expert consensus | BPAC | National | bpacnz Guide New Zealand (2017) | |||

| ANZPID-ASAP Guidelines | 2016 | Evidence-based recommendations, expert consensus, and local AMR | ANZPID-ASAP | National | ANZPID-ASAP Guideline (2016) | |||

| Singapore | Singapore SAP Guidelines | 2022 | ADAPTE method and evidence-based grading | NCID | National | Chung et al. (2022) | ||

| Taiwan | Taiwan MDRO Guidelines | 2022 | Evidence-based recommendations, expert consensus, and local Ardita | TSM and iDST | National | Sy et al. (2022) | ||

| Taiwan UP Guidelines | 2011 | Evidence-based consensus guidelines aligned with international standards and local AMR data | TUA | National | Chou et al. (2011) | |||

| Taiwan CAP Guidelines | 2008 | Based on epidemiologic data, clinical studies, laboratory investigations, and imaging studies | TPA | National | Lee et al. (2007) | |||

| Taiwan Surgical Prophylaxis Guidelines | 2004 | Evidence-based recommendations, expert consensus, and local resistance data | IDSC/TSA | National | IDSC Taiwan Surgical Association (2004) | |||

| Taiwan UTI Guidelines | 2000 | Based on expert consensus and review of the existing literature | IDSC/TSA | National | IDSC Taiwan Guidelines (2000) | |||

| UMIC | China | Chinese HAP/VAP Guidelines | 2018 | GRADE | CTS and CMA | National | Shi et al. (2019) | |

| CTS CAP Guidelines | 2016 | Evidence-based recommendations, expert consensus, and local data | CTS and CMA | National | Cao et al. (2018) | |||

| Fiji | Fiji Antibiotic Guidelines | 2019 | Evidence-based expert opinion | MOH and MSGF | National | Ministry of Health Fiji (2019a) | ||

| Malaysia | Malaysia NAG | 2024 | Evidence-based guidelines evolve over time | MOH | National | Ministry of Health Malaysia (2024) | ||

| Malaysia NAG | 2014 | Aligns with the AMS Program and incorporates updated evidence on AMR | MOH | National | Ministry of Health Malaysia (2014) | |||

| PPUKM Guidelines | 2012 | Interdisciplinary panel updates evidence-based guidelines | MOH | National | PPUKM Malaysia Guideline (2012) | |||

| Malaysia NAG | 2008 | Based on current evidence, drug formulary, and AMR patterns | MOH | National | Ministry of Health Malaysia (2008) | |||

| LMIC | Cambodia | CPG SAT guidelines | 2016 | Revision of the original practice guidelines | SHCH/HMC | International | SHCH/HMC (2016) | |

| Papua New Guinea | PNG HIV Guidelines | 2019 | Evidence-based recommendations, expert consensus, and data | NDOH | National | National department of Health Papua New Guinea (2019) | ||

| PNG Pediatric STGs | 2016 | Evidence-based expert review | PSPG | National | STGs Papua New Guinea (2016) | |||

| PNG Adult STGs | 2012 | Evidence based scoping reviews, field research, and epidemiological principles | NDOH/WHO | National | NDOH/WHO Papua New Guinea (2012) | |||

| Philippines | PIDS Antibiotic Guidelines | 2017 | Review of evidence-based local and international guidelines and literature | NAGCOM | National | NAGCOM Philippine Guideline (2017) | ||

| PSMID UTI Guidelines | 2015 | Evidence-based recommendations, expert consensus, and local AMR | PSMID | National | PSMID UTI Guidelines Philippine (2015) | |||

| Samoa | PIOA Guidelines | 2017 | Evidence-based guidelines | PIOA | Local | PIOA Guidelines Samoa (2017) | ||

| LIC | Tuvalu | TST Guidelines | 2010 | Evidence-based practice | MOH | National | Ministry of Health Tuvalu (2010) | |

| Solomon | Pacific Islands Pediatric STGs | 2017 | Evidence-based pediatric care protocols | UNICEF and WHO | National | STGs Solomon (2017) | ||

| Solomon Islands NCD Guidelines | 2011 | Evidence-based, WHO recommendations and local and international input | MOH/MS and WHO | National | Ministry of Health Solomon (2011) | |||

Global variation in antibiotic prescribing guidelines.

NB: HIC, high-income country; UMIC, upper-middle income country; LMIC, lower-middle income country; and LIC, low-income country.

3.3 Scope and coverage of guidelines

Antibiotic prescribing guidelines differed substantially in scope, focus, and strategy as a result of variations in epidemiology, cultural context, and healthcare infrastructure within the regions. Guidelines from HICs were generally more detailed, including diagnostic criteria, age-specific dosing, and alternative regimens. For example, USA IWGDF/IDSA guidelines for diabetic foot infection incorporate pathogen-specific approaches (Senneville et al., 2024), while guidelines from LMICs, such as those from Ethiopia and Malawi, typically use syndromic management protocols without referencing pathogen-specific resistance data (Ministry of Health Ethiopia, 2014; Ministry of Health Malawi, 2015) (Supplementary Table S2).

3.4 Implementation and monitoring strategies

Only a limited number of guidelines, primarily from HICs, included implementation strategies such as audit and feedback mechanisms, performance indicators, or integration with EHR systems (Jackson et al., 2020; NICE CAP Guideline, 2019; Bisno et al., 2002; NICE HAP Guideline, 2019). For instance, the Netherlands and Sweden have institutionalized prescribing audits within their national EHR infrastructure to support stewardship programs (Akhloufi et al., 2022; Spindler et al., 2012). In contrast, guidelines from many LMICs, such as Nigeria and Bangladesh, lacked such structured implementation frameworks, largely due to limited digital health infrastructure and financial constraints (Ministry of Health Nigeria, 2016; Ministry of Health Bangladesh, 2021a).

3.5 Patient education and communication features

The majority of guidelines emphasized the importance of patient counseling. However, those from LMICs often lacked modern communication strategies to support effective implementation. Patient education was notably underrepresented, particularly in LMIC guidelines. HIC guidelines, such as those from the UK and Canada, commonly include patient-facing leaflets, risk communication tools, and checklists to facilitate counseling (Greater Manchester, 2024; Desrosiers et al., 2011). In contrast, guidelines from LICs such as Malawi and Ethiopia rarely provide structured education materials, contributing to gaps in patient engagement and adherence (Ministry of Health Ethiopia, 2014; Ministry of Health Malawi, 2015). Moreover, modern communication tools such as mobile applications, SMS-based adherence reminders, and visual aids, including infographics, were rarely utilized, limiting the potential for patient engagement and behavior change in these settings (see Supplementary Table S2).

3.6 AMR surveillance and local adaptation

Guidelines from HICs typically incorporated recent AMR data into their recommendations. For example, national guidelines from Australia and the Netherlands rely on routine national antibiograms (Guideline Netherlands, 2024; Therapeutic Guidelines Australia, 2024). Conversely, many LMIC guidelines, such as those from Eswatini and Ethiopia, are considered outdated as they were published over 10 years ago and made no reference to local surveillance data or antibiograms (Ministry of Health Ethiopia, 2014; Ministry of Health Eswatini, 2012). This lack of local data hampers effective empiric prescribing and contributes to the overuse of broad-spectrum antibiotics in these countries. Supplementary Table S2 provides examples of guideline recency and AMR data inclusion by income group.

4 Discussion

Since the development of antibiotic prescribing guidelines is usually an expensive and time-consuming process, requiring an expert’ team developed on the basis of the best available evidence, systematic reviews, and sound clinical understanding, there are likely to be disparities among countries with different income levels. HICs generally had more extensive and consistently updated clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) compared to LMICs, largely due to greater demand for care and better access to the resources, infrastructure, and expertise required for the development of such guidelines (Owolabi et al., 2018). For example, guidelines from the UK’s NICE, the US IDSA, and the Netherlands’ SWAB are based on rigorous methodologies, frequent updates, and comprehensive AMR integration (Greater Manchester, 2024; Tamma et al., 2024; Guideline Netherlands, 2024). Meanwhile, guidelines from LMICs, such as Nigeria’s National STGs and Ethiopia’s Standard Treatment Guidelines, particularly those from LICs, fell short in terms of coverage, quality, and content (Ministry of Health Ethiopia, 2014; Ministry of Health Nigeria, 2016).

As evidence-based decision-making has become a global standard for health interventions, the GRADE framework is increasingly used for the development of clinical guidelines (Baral et al., 2012; Park et al., 2015; Boon et al., 2021). HICs, supported by robust infrastructure and expert panels, have extensively implemented GRADE to provide transparency and methodological strength in recommendations (Bayona et al., 2017). For example, guidelines developed by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), the American Thoracic Society (ATS), and UK bodies such as NICE and the British Thoracic Society (BTS) used GRADE consistently to integrate high-quality evidence and improve the implementation of antibiotic prescribing protocols (Jackson et al., 2020; NICE Guidelines, 2023; Smith et al., 2020; Gould et al., 2012a). In contrast, LMICs often rely on expert consensus due to limited resources, training, and access to evidence (Mzumara et al., 2023). Although several LMICs, including Pakistan, Ghana, Timor-Leste, and Rwanda, have developed evidence-based national treatment guidelines, their development is typically challenged by limited surveillance data, restricted funding, and suboptimal laboratory infrastructure (MMIDSP Guideline, 2022; Ministry of Health Ghana, 2017a; Hospital Guidelines Timor Leste, 2016; Ministry of Health Rwanda, 2022). These limitations also impede the routine use of systematic reviews and localized AMR data to inform prescribing.

Strengthening national efforts to combat AMR requires the development of guidelines that are both globally informed and locally applicable, as emphasized by the WHO. However, many LMICs lack the necessary infrastructure to support such efforts, particularly in terms of robust AMR surveillance systems. In these countries, either there is no routine national antibiogram reporting or the systems are fragmented and limited to isolated institutions (Gandra et al., 2020; Peters et al., 2024; Iskandar et al., 2021). A strong surveillance system typically includes nationwide coverage alongside standardized data collection, timely reporting, and integration with treatment guideline development (Nsubuga et al., 2011; Yang et al., 2020). The absence of these features in several LMICs undermines the ability to track resistance patterns and update empiric treatment guidelines accordingly (Gandra et al., 2020). Consequently, prescribers might find it challenging to match their practices with the WHO AWaRe book guidance; however, the AWaRe system provides a good starting point, particularly given its increasing use to monitor antibiotic use, including among LMICs, and the ongoing efforts to strengthen surveillance systems in these settings (Do et al., 2023; Iskandar et al., 2021; Tawfick et al., 2023). As a result, many LMICs are now working to implement more effective resistance surveillance in line with WHO goals. Local adaptation of the AWaRe guidance is key to support its use and enhance the effective management of infectious diseases. Local resistance trends contained within national and regional AMR surveillance data must inform first-line treatment choices, ensuring that guideline recommendations reflect local resistance profiles rather than relying merely on global trends (Mastrangelo et al., 2021). For instance, Rwanda’s susceptibility-guided empiric therapy and Kenya’s formulary mapping provide an example of how national guidance can be customized based on local data (Ministry of Health Rwanda, 2022; Gitaka et al., 2020). However, many LMICs lack comprehensive antibiograms, resulting in empiric overuse of broad-spectrum antibiotics, which should now be limited under the WHO AWaRe framework and guidance. This was evident in several guidelines included in our review. This included those from Nigeria, Ethiopia, and Malawi, which provided syndromic treatment recommendations without referencing local resistance data (Ministry of Health Ethiopia, 2014; Ministry of Health Malawi, 2015; Ministry of Health Nigeria, 2016). Addressing this gap involves investment in laboratory infrastructure and the training of healthcare professionals to correctly interpret and apply surveillance (Nishimura et al., 2008). This is important if LMICs are to achieve their AMR goals within their NAPs.

In HICs, AMS initiatives usually involve EHR audits, rapid diagnostics, and multidisciplinary stewardship teams to enhance appropriate antibiotic use. These technologies and institutional structures are usually lacking in LMICs. Scaling up such efforts across sectors will be critical to limiting unnecessary empiric antibiotic use and enhancing treatment outcomes (Bankar et al., 2022).

Financial barriers may also restrict the implementation of guidelines in LMICs as appreciable resources are typically needed in guideline development and adaptation (Baral et al., 2012). Technical requirements, ethical considerations, infrastructural barriers, and overburdened health systems, coupled with the lack of sufficient funding, typically prevent effective and meaningful implementation of clinical trials and other studies in LMICs to improve future antibiotic use. Consequently, it can be difficult to make conclusions regarding the applicability of guidelines that are applicable in HICs but could be a problem among LMICs (Stokes et al., 2016). To achieve success, strategies need to be adapted to overcome local resistance profiles, invest in AMS activities and diagnostics, and develop global partnerships to turn theory into practical and equitable solutions to address AMR in LMICs.

Educating key stakeholders, including prescribers and patients, about WHO AWaRe principles, including the importance of prioritizing Access over Watch antibiotics and avoiding unnecessary broad-spectrum antibiotic use, can strengthen AMS efforts at the population level (Saleem et al., 2025c). This is because patient education and counseling play crucial roles in improving antibiotic use, especially in LMICs, and enhancing healthcare outcomes (Saleem et al., 2025c). Counseling interventions often incorporate practical tools and follow-up care to support adherence. The British Thoracic Society’s 2020 Long-Term Macrolide Guidelines suggest written materials on therapy risks/benefits, whereas the ACCP 2006 Chronic Cough Guidelines advise patients on symptom relief and the self-limiting nature of viral bronchitis (Smith et al., 2020; Braman, 2006). Post-discharge instructions, including those in the SCCM 2020 Sepsis Guidelines, incorporate monitoring for secondary infections and corticosteroid-related side effects (Weiss et al., 2020). Effective counseling not only reduces unnecessary antibiotic use but also educates patients to engage in stewardship efforts, which include reducing requests and expectations for antibiotics for self-limiting viral infections for themselves or their children (Saleem et al., 2025c). In combination, these strategies connect clinical practice and community education, creating a unified front to reduce unnecessary antibiotic use and associated AMR, which is particularly important in LMICs (Mastrangelo et al., 2021).

We acknowledge that our study has limitations. We considered only English-language guidelines that were openly accessible, potentially leading to an overrepresentation of guidelines from HICs, particularly those in the European Region. There were also several countries for which we could not find guidance documents, and we encourage these countries to make their guidelines open-access and readily available to key stakeholder groups, including the general public. Similarly, our research might have missed documents depending on the search queries and engines used. However, we sought to include as many guiding documents as possible. Consequently, we believe our findings are robust and provide valuable direction for future work.

5 Conclusion

We found significant disparities in the availability, structure, and methodological rigor of guidelines across countries with different income levels. HICs commonly apply evidence-based frameworks such as GRADE, incorporate local AMR data, and have embedded stewardship strategies in the development of their antibiotic guidelines. This contrasts with many guidelines from LMICs, which remain generalized, outdated, and often rely on expert opinion due to limited resources, diagnostic capacity, and surveillance infrastructure. The incorporation of WHO AWaRe Book recommendations, as well as the extent to which current guidelines addressed patient education, AMR surveillance, and stewardship strategies, was also more evident in guidelines from HICs. In contrast, these components were often lacking in guidelines from LMICs, with patient education and surveillance data particularly underrepresented. The WHO AWaRe framework and Book provide a vital stepping stone, especially for LMICs; however, its successful implementation in LMICs relies on equity-led reforms. By prioritizing context-specific guidelines, increasing funding for diagnostics and stewardship, and fostering global partnerships, LMICs can transform the AWaRe framework and the associated guidance into practical and effective solutions to combat rising AMR rates. This approach will not only addresses current disparities but also help preserve the efficacy of antibiotics for future generations.

Statements

Author contributions

EJ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. ZS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. BG: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. MU: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review and editing. AA: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review and editing. AH: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review and editing. JM: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. MQ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. SA: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphar.2025.1600787/full#supplementary-material

References

1

African Union (2021). “African antibiotic treatment guidelines for common bacterial infections and syndromes—recommended antibiotic treatments,” in Neonatal and pediatric patients. Available online at: https://africaguidelines.onehealthtrust.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Guidelines_Adults_Peds_English.pdf.

2

AgweyuA.OpiyoN.EnglishM. J. B. p. (2012). Experience developing national evidence-based clinical guidelines for childhood pneumonia in a low-income setting-making the GRADE?BMC Pediatr.12, 1–12. 10.1186/1471-2431-12-1

3

AisanovZ.AvdeevS.ArkhipovV.BelevskiyA.ChuchalinA.LeshchenkoI.et al (2018). Russian guidelines for the management of COPD: algorithm of pharmacologic treatment. PMC, 183–187.

4

AkhloufiH.van der SijsH.MellesD. C.van der HoevenC. P.VogelM.MoutonJ. W.et al (2022). The development and implementation of a guideline-based clinical decision support system to improve empirical antibiotic prescribing. BMC Med. Inf. Decis. Mak.22 (1), 127. 10.1186/s12911-022-01860-3

5

AldarhamiA. (2023). Identification of novel bacteriocin against staphylococcus and bacillus species. Int. J. Health Sci.17 (5), 15–22.

6

AlzomorO.AlhajjarS.AljobairF.AleniziA.AlodyaniA.AlzahraniM.et al (2017). Management of community-acquired pneumonia in infants and children: clinical practice guidelines endorsed by the saudi pediatric infectious diseases society. Int. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med.4 (4), 153–158. 10.1016/j.ijpam.2017.12.002

7

AMPATH Antibiotic Guide (2017). Chapter 7: Central nervous system infections. South Africa: In Antibiotic guide. Available online at: https://www.ampath.co.za/storage/12/Chapter-7-Central-Nervous-System-Infections.pdf.

8

AntwiA.StewartA.CrosbieM. (2020). Fighting antibiotic resistance: a narrative review of public knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions of antibiotics use. Perspect. public health140 (6), 338–350. 10.1177/1757913920921209

9

ANZPID-ASAP Guideline (2016). ANZPID-ASAP guidelines for antibiotic duration and IV-Oral switch in children, newzealand. Available online at: https://starship.org.nz/search/?k=antibiotic%20guidelines&m_us=Health%20Professional.

10

AutoreG.BernardiL.GhidiniF.La ScolaC.BerardiA.BiasucciG.et al (2023). Antibiotic prophylaxis for the prevention of urinary tract infections in children: guideline and recommendations from the Emilia-Romagna pediatric urinary tract infections (UTI-Ped-ER) study group,Antibiot. (Basel).12, 1040. 10.3390/antibiotics12061040

11

Bahria International Hospital Guideline (2023). Antibiotic guideline 2023. Lahore, Pakistan: Bahria International Hospital. Available online at: https://bahriainternationalhospital.com/5952-2/.

12

BaleaL. B.GulestøR. J. A.XuH.GlasdamS. (2025). Physicians’, pharmacists’, and nurses’ education of patients about antibiotic use and antimicrobial resistance in primary care settings: a qualitative systematic literature review. Front. Antibiotics3, 1507868. 10.3389/frabi.2024.1507868

13

BankarN. J.UgemugeS.AmbadR. S.HawaleD. V.TimilsinaD. R. (2022). Implementation of antimicrobial stewardship in the healthcare setting. Cureus14 (7), e26664. 10.7759/cureus.26664

14

BaralS. D.WirtzA.SifakisF.JohnsB.WalkerD.BeyrerC. (2012). The highest attainable standard of evidence (HASTE) for HIV/AIDS interventions: toward a public health approach to defining evidence. Public health Rep.127 (6), 572–584. 10.1177/003335491212700607

15

BaranA.KwiatkowskaA.PotockiL. (2023). Antibiotics and bacterial Resistance—A short story of an endless arms race. Int. J. Mol. Sci.24 (6), 5777. 10.3390/ijms24065777

16

BarkerT. H.DiasM.SternC.PorrittK.WiechulaR.AromatarisE.et al (2021). Guidelines rarely used GRADE and applied methods inconsistently: a methodological study of Australian guidelines. J. Clin. Epidemiol.130, 125–134. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.10.017

17

BarryE.O'BrienK.MoriartyF.CooperJ.RedmondP.HughesC. M.et al (2016). PIPc study: development of indicators of potentially inappropriate prescribing in children (PIPc) in primary care using a modified Delphi technique. BMJ6 (9), e012079. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012079

18

BartlettJ. G.BreimanR. F.MandellL. A.FileT. M. (1998). Community-acquired pneumonia in adults: guidelines for management. The infectious diseases society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis.26 (4), 811–838. 10.1086/513953

19

BartonM.HawkesM.MooreD.ConlyJ.NicolleL.AllenU.et al (2006). Guidelines for the prevention and management of community‐associated methicillin‐resistant staphylococcus aureus: a perspective for Canadian health care practitioners. Can. J. Infect. Dis. Med. Microbiol.17, 4C–24C. 10.1155/2006/971352

20

BassettiM.GiacobbeD. R.BruzziP.BarisioneE.CentanniS.CastaldoN.et al (2021). Clinical management of adult patients with COVID-19 outside intensive care units: guidelines from the Italian society of anti-infective therapy (SITA) and the Italian society of pulmonology (SIP). Infect. Dis. Ther.10 (4), 1837–1885. 10.1007/s40121-021-00487-7

21

BayonaH.OwolabiM.FengW.OlowoyoP.YariaJ.AkinyemiR.et al (2017). A systematic comparison of key features of ischemic stroke prevention guidelines in low-and middle-income vs. high-income countries. J. neurological Sci.375, 360–366. 10.1016/j.jns.2017.02.040

22

BenešJ.StebelR.MusilV.KrůtováM.VejmelkaJ.KohoutP. (2022). Updated Czech guidelines for the treatment of patients with colitis due to Clostridioides difficile. Klin. Mikrobiol. Infekc. Lek.28 (3), 77–94.

23

BisnoA. L.GerberM. A.GwaltneyJ. M.JrKaplanE. L.SchwartzR. H.Infectious Diseases Society of America (2002). Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of group A streptococcal pharyngitis. Infectious diseases society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis.35 (2), 113–125. 10.1086/340949

24

BokhariN.AkhtarS.IzharM.AliW.BashirN. (2017). Pakistan chest society. Guidelines for the management of community acquired pneumonia in adults. Available online at: https://www.pakistanchestsociety.pk/wp-content/uploads/79_archives.pdf.

25

BoltenaM. T.WoldieM.SiranehY.SteckV.El-KhatibZ.MorankarS. (2023). Adherence to evidence-based implementation of antimicrobial treatment guidelines among prescribers in Sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Pharm. Policy Pract.16 (1), 137. 10.1186/s40545-023-00634-0

26

BonkatG.BartolettiR.BruyereF.CaiT.GeerlingsS.KövesB.et al (2017). EAU guidelines on urological infections. Eur. Assoc. urology18, 22–26.

27

BoonM. H.ThomsonH.ShawB.AklE. A.LhachimiS. K.López-AlcaldeJ.et al (2021). Challenges in applying the GRADE approach in public health guidelines and systematic reviews: a concept article from the GRADE public health group. J. Clin. Epidemiol.135, 42–53. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.01.001

28

BordeK.MedisettyM. K.MuppalaB. S.ReddyA. B.NosinaS.DassM. S.et al (2022). Impact of an antimicrobial stewardship intervention on usage of antibiotics in coronavirus disease-2019 at a tertiary care teaching hospital in India. IJID Reg.3, 15–20. 10.1016/j.ijregi.2022.02.003

29

BoylesT. H.BrinkA.CalligaroG. L.CohenC.DhedaK.MaartensG.et al (2017). South African guideline for the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. J. Thorac. Dis.9 (6), 1469–1502. 10.21037/jtd.2017.05.31

30

bpacnz Guide New Zealand. (2024). Available online at: https://bpac.org.nz/antibiotics/guide.aspx.

31

bpacnz New Zealand (2017). The bpacnz antibiotic guide. Available online at: https://bpac.org.nz/2017/docs/abguide.pd (Accessed September 02, 2024).

32

BradleyJ. S.ByingtonC. L.ShahS. S.AlversonB.CarterE. R.HarrisonC.et al (2011). The management of community-acquired pneumonia in infants and children older than 3 months of age: clinical practice guidelines by the pediatric infectious diseases society and the infectious diseases society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis.53 (7), e25–e76. 10.1093/cid/cir531

33

BramanS. S. J. C. (2006). Chronic cough due to acute bronchitis: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest129 (1), 95S-103S–103S. 10.1378/chest.129.1_suppl.95S

34

BratzlerD. W.DellingerE. P.OlsenK. M.PerlT. M.AuwaerterP. G.BolonM. K.et al (2013). Clinical practice guidelines for antimicrobial prophylaxis in surgery. Surg. Infect.14 (1), 73–156. 10.1089/sur.2013.9999

35

BredemeyerM. (2016). ACP/CDC provide guidelines on the use of antibiotics for acute respiratory tract infection. American Family Physician, 1016. Available online at: https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2016/1215/p1016.html.

36

BrinkmannI.KibuuleD. (2020). Effectiveness of antibiotic stewardship programmes in primary health care settings in developing countries. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm.16 (9), 1309–1313. 10.1016/j.sapharm.2019.03.008

37

BSMMU Guideline Bangladesh (2023). BSMMU guidelines. Available online at: https://forms.bsmmu.ac.bd/antibiotic_guideline/list.html (Accessed June 11, 2024).

38

BSW ICB Guidelines UK (2024). Management of infection guidance for primary Care,UK. Available online at: https://bswtogether.org.uk/medicines/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2025/01/FULL-antibiotics-guidance-update-Dec-2024-recurrent-UTI-update.pdf (Accessed September 24, 2024).

39

ButlerK. (2016). Manual of childhood infections. Oxford University Press.

40

CaoB.HuangY.SheD. Y.ChengQ. J.FanH.TianX. L.et al (2018). Diagnosis and treatment of community‐acquired pneumonia in adults: 2016 clinical practice guidelines by the Chinese thoracic society, Chinese medical association. Clin. Respir. J.12 (4), 1320–1360. 10.1111/crj.12674

41

CDC Guidelines (2024). Adult antibiotic prescribing guidelines. Available online at: https://cha.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Telligen-Version-CDC-Outpatient-Antibiotic-Treatment-Guidelines.pdf (Accessed June 14, 2024).

42

CDC (2017). Adult antibiotic prescribing guidelines. Available online at: https://www.health.ny.gov/publications/1174_8.5x11.pdf (Accessed June 13, 2024).

43

CharaniE.MendelsonM.PallettS. J. C.AhmadR.MpunduM.MbamaluO.et al (2023). An analysis of existing national action plans for antimicrobial Resistance—Gaps and opportunities in strategies optimising antibiotic use in human populations. Lancet Glob. Health11 (3), e466–e474. 10.1016/S2214-109X(23)00019-0

44

ChaudhuriD.NeiA. M.RochwergB.BalkR. A.AsehnouneK.CadenaR.et al (2024). 2024 focused update: guidelines on use of corticosteroids in sepsis, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and community-acquired pneumonia. Natl. Libr. Med.52 (5), e219–e233. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000006172

45

CHI Guideline Ireland (2020). Antimicrobial guidelines, Ireland. Available online at: https://www.iaem.ie/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Antimicrobial-Guidelines-2020.pdf (Accessed August 02, 2024).

46

ChigomeA.RamdasN.SkosanaP.CookA.SchellackN.CampbellS.et al (2023). A narrative review of antibiotic prescribing practices in primary care settings in South Africa and potential ways forward to reduce antimicrobial resistance. Antibiotics12 (10), 1540. 10.3390/antibiotics12101540

47

ChirwaM.DaviesO.CastelinoS.MpengeM.NyatsanzaF.SethiG.et al (2021). United Kingdom British association for sexual health and HIV national guideline for the management of epididymo-orchitis, 2020. Natl. Libr. Med.32 (10), 884–895. 10.1177/09564624211003761

48

ChouY.-H.YangS. S.HsiehC. H.ChangC. P. (2011). Taiwanese recommendations for antimicrobial prophylaxis in urological surgery. Urol. Sci.22 (2), 63–69. 10.1016/s1879-5226(11)60014-6

49

ChowA. W.BenningerM. S.BrookI.BrozekJ. L.GoldsteinE. J. C.HicksL. A.et al (2012). IDSA clinical practice guideline for acute bacterial rhinosinusitis in children and adults. Clin. Infect. Dis.54 (8), e72–e112. 10.1093/cid/cir1043

50

CHQHospital. Children’s health Queensland paediatric antibiocard: empirical antibiotic guidelines. (2022). Available online at: https://www.childrens.health.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0037/176878/Antibiocard.pdf.

51

ChuaA. Q.VermaM.HsuL. Y.Legido-QuigleyH. (2021). An analysis of national action plans on antimicrobial resistance in southeast Asia using a governance framework approach. Lancet Regional Health–Western Pac.7, 100084. 10.1016/j.lanwpc.2020.100084

52

ChungW. T. G.ShafiH.SeahJ.PurnimaP.PatunT.KamK. Q.et al (2022). National surgical antibiotic prophylaxis guideline in Singapore. Ann. Acad. Med. Singap.51 (11), 695–711. 10.47102/annals-acadmedsg.2022273

53

ControlN. C. F. D.National treatment guidelines for antimicrobial use in infectious diseases. (2016). Available online at: https://ncdc.mohfw.gov.in/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/File622.pdf.

54

CooperL.SneddonJ.AfriyieD. K.SefahI. A.KurdiA.GodmanB.et al (2020). Supporting global antimicrobial stewardship: antibiotic prophylaxis for the prevention of surgical site infection in low-and middle-income countries (LMICs): a scoping review and meta-analysis. JAC-Antimicrobial Resist.2 (3), dlaa070. 10.1093/jacamr/dlaa070

55

CorrêaR. d.A.LundgrenF. L. C.Pereira-SilvaJ. L.Frare e SilvaR. L.CardosoA. P.LemosA. C. M.et al (2009). Brazilian guidelines for community-acquired pneumonia in immunocompetent adults-2009. J. Bras. Pneumol.35, 574–601. 10.1590/s1806-37132009000600011

56

CoxJ. A.VliegheE.MendelsonM.WertheimH.NdegwaL.VillegasM. V.et al (2017). Antibiotic stewardship in low-and middle-income countries: the same but different?Clin. Microbiol. Infect.23 (11), 812–818. 10.1016/j.cmi.2017.07.010

57

DadgostarP. (2019). Antimicrobial resistance: implications and costs. Infect. drug Resist.12, 3903–3910. 10.2147/IDR.S234610

58

Danish Health and medicine Authority Guidelines (2013). Guidelines on prescribing antibiotics, Denmark. Available online at: https://www.sundhedsstyrelsen.dk/-/media/Udgivelser/2013/Publ2013/Guidelines-on-prescribing-antibiotics.ashx.

59

D’ArcyN.Ashiru-OredopeD.OlaoyeO.AfriyieD.AkelloZ.AnkrahD.et al (2021). Antibiotic prescribing patterns in Ghana, Uganda, Zambia and Tanzania hospitals: results from the global point prevalence survey (G-PPS) on antimicrobial use and stewardship interventions implemented. Antibiotics10 (9), 1122. 10.3390/antibiotics10091122

60

DebastS. B.BauerM. P.KuijperE. J.European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (2014). European society of clinical microbiology and infectious diseases: update of the treatment guidance document for Clostridium difficile infection. Clin. Microbiol. Infect.20, 1–26. 10.1111/1469-0691.12418

61

Department of Health South Africa (2023). Guidelines for the prevention and containment of antimicrobial resistance in South African hospitals. Available online at: https://knowledgehub.health.gov.za/system/files/elibdownloads/2023-04/Guidelines%2520for%2520the%2520prevention%2520and%2520containment%2520of%2520AMR%2520in%2520SA%2520hospitals.pdf (Accessed: June 16, 2024).

62

DesrosiersM.EvansG. A.KeithP. K.WrightE. D.KaplanA.BouchardJ.et al (2011). Canadian clinical practice guidelines for acute and chronic rhinosinusitis. Allergy, Asthma and Clin. Immunol.7, 2–38. 10.1186/1710-1492-7-2

63

De WithK.AllerbergerF.AmannS.ApfalterP.BrodtH. R.EckmannsT.et al (2016). Strategies to enhance rational use of antibiotics in hospital: a guideline by the German society for infectious diseases. Infection. 44, 395–439. 10.1007/s15010-016-0885-z

64

DoP. C.AssefaY. A.BatikawaiS. M.ReidS. A. (2023). Strengthening antimicrobial resistance surveillance systems: a scoping review. BMC Infect. Dis.23 (1), 593. 10.1186/s12879-023-08585-2

65