Abstract

Background:

While elevated plasma ceramides are independently associated with increased cardiovascular risk in patients with coronary artery disease (CAD), the impact of current lipid-modifying drugs on ceramides, remains under-researched. This study examines the effect of PCSK9 inhibitors on plasma ceramides in patients with CAD who had received statin therapy.

Methods:

Comparing the effect of PCSK9i vs. statin on ceramide levels. The primary outcome was percent change in ceramide levels. Subgroup analyses were done to explore potential treatment effect differences.

Results:

Among 292 patients (44% statin group, 56% PCSK9i group), baseline characteristics were broadly similar. PCSK9i use significantly reduced ceramide levels compared to statin therapy: Cer 16:0 decreased by −22.93% (95% CI, −29.73% to −16.14%), Cer 18:0 by −24.54% (95% CI, −33.07 to −16.01), and Cer 24:0 by −34.82% (95% CI, −48.41 to −21.23). PCSK9i also significantly lowered LDL-C by 29.63%, triglycerides by 16.69%, and total cholesterol by 10.25%, while modestly increasing HDL-C. Sensitivity and subgroup analyses confirmed the consistent ceramide-lowering effect of PCSK9i across various patient demographics and baseline characteristics.

Conclusion:

PCSK9i is associated with significant reduction in distinct ceramide concentrations, compared statin therapy only.

Highlights

We demonstrate that PCSK9i therapy significantly reduces distinct ceramide species (Cer 16:0, Cer 18:0, Cer 24:1 and Cer 24:0), which are independently associated with increased cardiovascular risk in patients with coronary artery disease.

Our findings highlight the potential clinical implications of PCSK9 inhibitors in reducing cardiovascular risk beyond LDL-C lowering.

Our study addresses a significant gap in the current literature by investigating the differential impact of PCSK9 inhibitors and statins on plasma ceramide levels in patients with coronary artery disease.

Introduction

An increasing body of research has identified plasma ceramides as important prognostic markers in patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) (Choi et al., 2021). Ceramides are bioactive molecules involved in various cellular processes, and trials in rodents have demonstrated that the disease condition can be improved by modulating the ceramide profile (Chaurasia et al., 2019; Summers et al., 2019; Bharath et al., 2015). Recent study also demonstrated that the effect of Cer16:0 - CYSLTR2/P2RY6 - GPCRs (G-protein-coupled receptors) signaling on the progression of atherosclerosis in both humans and mice (Zhang et al., 2025). Targeting ceramide lowering therapy may be a key breakthrough in future anti-atherosclerotic treatment.

Lipid-lowering therapy is essential in the treatment of coronary heart disease (Mach et al., 2025). PCSK9, a protein generated by the liver, primarily regulates the levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in the blood by influencing the degradation of LDL-C receptors and acts as a vital part of this process (Emma et al., 2020). A post hoc analysis of the ODYSSEY OUTCOMES trial using the baseline apolipoprotein profile for high-risk assessment can indicate the potential benefits that patients will receive from the alirocumab (Reijnders et al., 2025). This suggests that PCSK9 inhibitors (PCSK9i) might be effective in reducing residual risk by diminishing other lipid molecules, in addition to its impact on LDL-C (O'Donoghue et al., 2019; Klug et al., 2024). Interestingly, lipid-lowering medication such as statins and PCSK9 inhibitors also reduce ceramide levels (Ng et al., 2014; Tarasov et al., 2014; Ye et al., 2020). Additionally, rosuvastatin dose-dependently decreases plasma ceramide—independent of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) reduction—in men with metabolic syndrome (Ng et al., 2014). A previous study showed that PCSK9 inhibitor treatment in 24 hypercholesterolemic patients led to a significant reduction in specific ceramides (Cer 16:0, Cer 18:0, Cer 24:1, and Cer 24:0), and the reduction in ceramides did not correlate with the reduction in LDL-C13. However, there are no direct comparisons available to evaluate the efficacy of the two lipid-lowering medication (Statin vs. PCSK9i), and the previous studies both suffered from small sample sizes.

We performed a study on retrospective clinical data to compare the effects of Statins and PCSK9 inhibitors on reducing the plasma ceramide concentrations in CAD patients. These effects may offer valuable therapeutic opportunities in CAD patients exposure to high ceramide level.

Methods

Study design and population

Patients diagnosed with CAD who underwent at least two plasma ceramide examinations at Beijing Anzhen Hospital, Capital Medical University, were screened between March 2023 and May 2025 (Patients with multivessel coronary artery disease undergo staged treatment of the affected vessels, with interventions spaced approximately 1 month apart). Exclusion criteria included: 1. patients previously treated with PCSK9i before enrollment; 2. patients with a time interval between serial ceramide measurements of less than 3 weeks or more than 6 weeks; 3. patients with incomplete clinical data regarding lipid-lowering treatment protocols. Study participants were categorized based on the initiation of PCSK9i therapy after the first ceramide examination (Treatment group: PCSK9i combined with statin, Placebo group: statin only or combined with ezetimibe). The primary efficacy endpoint was the percentage change in plasma ceramide from baseline to repeated measurement in the PCSK9i group compared with the placebo group. Baseline was defined as the last measurement prior to the first dose of PCSK9i. The study protocol was in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Beijing Anzhen Hospital (IRB number: KS2023081), with informed consent obtained from all participants.

Data collection

Upon initial discharge, these patients are prescribed two doses of PCSK9 inhibitors. We gathered patients over 4–5 weeks to ensure they received a consistent PCSK9i dosage (Evolocumab 140 mg/Alirocumab 75 mg i.h. Biw). The demographic variables comprised age and sex. Clinical and laboratory data encompassed 1. medical history pertaining to diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and ischemic stroke; 2. baseline and serial measurements of serum lipid levels, including total cholesterol (TC), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), triglycerides (TG), as well as plasma ceramide levels (Cer 16:0, Cer 18:0, Cer 24:1, and Cer 24:0); and 3. lipid-lowering medications administered during hospitalization, specifically statins, ezetimibe, and PCSK9 inhibitors.

Measurement of ceramide level

Patients fasted overnight for 8 h before their scheduled ICA. On the morning of the initial and follow-up ICA visits, 500 μL blood samples were taken. Plasma was separated within an hour and stored at −80 °C for later analysis. Plasma samples were thawed at 4 °C, mixed with internal standards, and treated with isopropanol for protein precipitation. After vortexing and centrifuging at 4000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C, the supernatant was transferred to a 96-well plate for ceramide analysis (Cer 16:0, Cer 18:0, Cer 24:1, and Cer 24:0) using an LC-MS/MS system. The methods used in the laboratory and the quality control procedures have been described in detail in prior reports (Zhang et al., 2023).

Statistical analysis

The prespecified primary efficacy estimand involved an assessment of the mean treatment effect of PCSK9 inhibitors in comparison to placebo within a population that adheres to statin therapy. Post hoc statistical power was calculated for each ceramide species based on the observed effect size (Cohen’s d) derived from the group differences and the actual sample size of the study. All analyses demonstrated excellent statistical power (>0.94).

Continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation or median (IQR) based on normality assessed by Shapiro-Wilk tests. Baseline characteristics were compared between treatment groups (Statin vs. PCSK9i plus statin) using independent t-tests (normal distributions), Mann-Whitney U tests (non-normal distributions). Categorical variables were presented as frequencies (percentages) and compared between groups using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. Ceramide levels were assessed at baseline (T0) and 1-month follow-up (T1). Change values (Δ) were calculated as T1 – T0, relative reduction (Δ %) were calculated as (T1 –T0)/T0 × 100%. Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) model with age as a covariate was conducted to assess the differences in the time-averaged percent change in ceramide levels from baseline between the PCSK9i and statin groups. For the pairwise comparisons between these groups, the least-squares (LS) means, standard errors, and two-sided 95% confidence intervals were calculated and reported. Moreover, Propensity Score Matching (PSM,genetic, 1:1) and Generalized Linear Mixed Model (model < - nlme::lme (Δ_Ceramide % ∼ PCSK9i + Age + Sex + Hypertension + Diabetes + Stroke + LDL-C_T0 + HDL-C_T0 + TG_T0 + TC_T0, random = ∼1|id) was conducted as a sensitivity analysis to assess the association between PCSK9 inhibitor treatment and percentage change in Ceramide. Subgroup analysis was carried out to confirm whether the association of PCSK9i with change in ceramide was consistent across all pre-specified subgroups (Sex, Hypertension, Diabetes and LDL-C concentration at baseline). Statistical analyses were conducted using R Programming Language 4.3.2 (Vienna, Austria). Treatment comparisons for primary end points were performed at the full significance level of P < 0.05.

Results

Patient characteristics

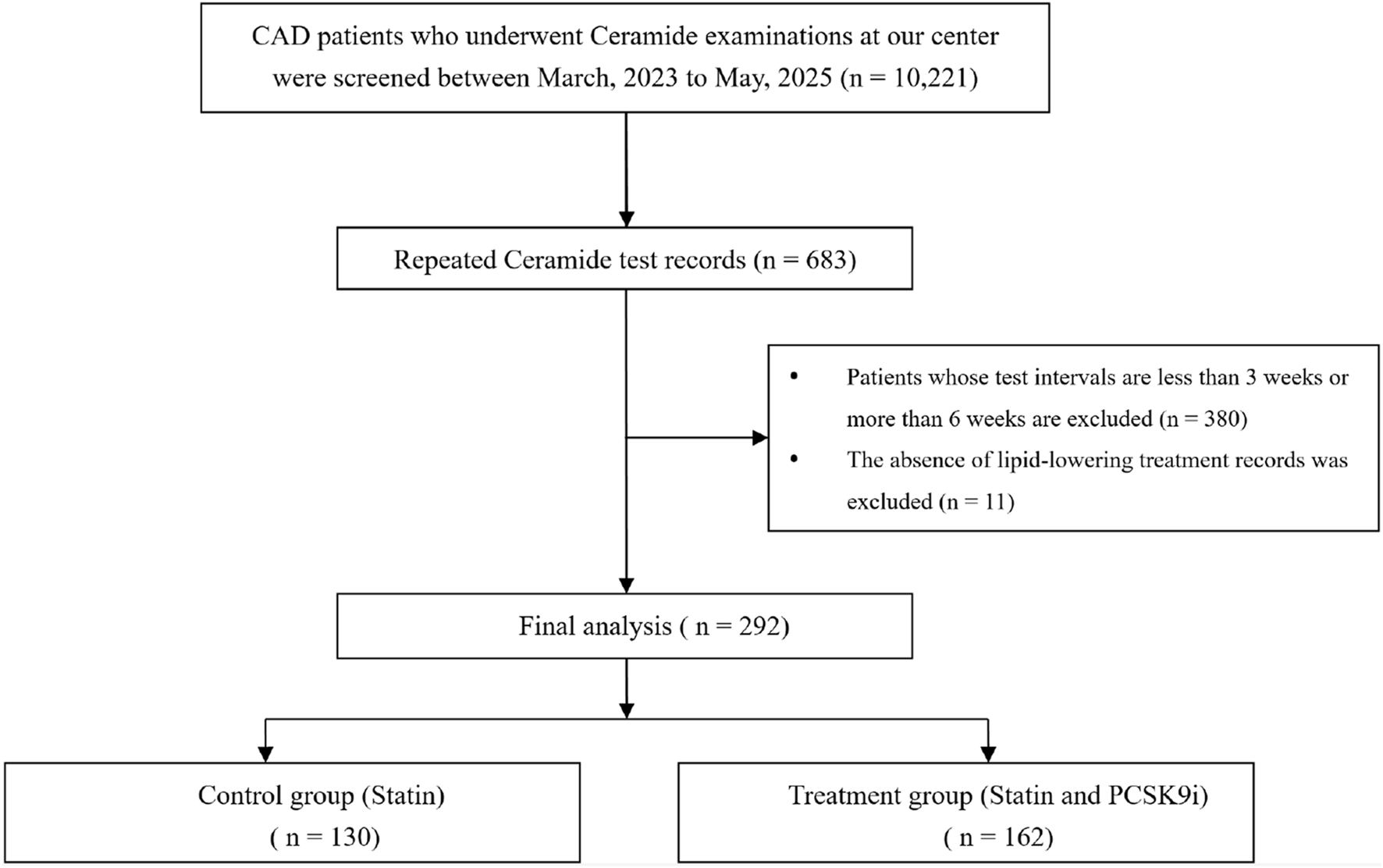

The baseline characteristics of the study population (N = 292), stratified by the use of PCSK9i at discharge, are presented in Table 1. Of these, 130 (44%) in the statin group and 162 (56%) in the PCSK9i group. The median age was 61 years, 58 participants (20%) were female. Among these patients, 181 participants (62.0%) had established hypertension, while diabetes (73.7%), stroke (6.1%) were prevalent. Baseline characteristics were broadly similar across groups. The most frequently used lipid-lowering medications were atorvastatin (44.6% vs. 59.3%), and rosuvastatin (50% vs. 38.9%). Ezetimibe use differed significantly between groups (31.5% vs. 0%, p < 0.001). The flowchart of patients enrolled are summarized in Figure 1.

TABLE 1

| Characteristic | No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Statin n = 130 |

PCSK9i (+statin) n = 162 |

|

| Age, median (IQR), years | 61 (54, 67) | 61 (53, 68) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Female | 25 (19.2%) | 33 (20.4%) |

| Male | 105 (80.8%) | 129 (79.6%) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 78 (60.0%) | 103 (63.6%) |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 56 (43.1%) | 56 (34.6%) |

| Stroke, n (%) | 5 (3.8%) | 13 (8.0%) |

| Lipid-modifying therapy, n (%) | ||

| Atorvastatin, 20 mg | 58 (44.6%) | 96 (59.3%) |

| Rosuvastatin, 10 mg | 65 (50.0%) | 63 (38.9%) |

| Other statin | 7 (3.4%) | 3 (1.8%) |

| Ezetimibe, 10 mg | 41 (31.5%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Lipid measures at baseline, median (IQR), mmol/L | ||

| LDL cholesterol | 1.67 (1.31, 2.26) | 2.42 (1.93, 2.97) |

| HDL cholesterol | 1.06 (0.91, 1.23) | 1.05 (0.92, 1.25) |

| Triglycerides | 1.33 (0.92, 1.85) | 1.67 (1.18, 2.40) |

| Total cholesterol | 3.19 (2.75, 4.01) | 4.06 (3.42, 4.76) |

| Ceramide measures at baseline, median (IQR), umol/L | ||

| Cer 16:0 | 0.22 (0.17, 0.28) | 0.25 (0.20, 0.32) |

| Cer 18:0 | 0.07 (0.05, 0.08) | 0.08 (0.06, 0.12) |

| Cer 24:1 | 0.69 (0.54, 0.97) | 0.85 (0.62, 1.07) |

| Cer 24:0 | 2.89 (2.18, 3.70) | 3.50 (2.51, 4.75) |

| Cer 16:0/Cer 24:0 | 0.078 (0.060, 0.096) | 0.073 (0.061, 0.089) |

| Cer 18:0/Cer 24:0 | 0.023 (0.016, 0.033) | 0.022 (0.017, 0.032) |

| Cer 24:1/Cer 24:0 | 0.25 (0.18, 0.34) | 0.24 (0.18, 0.32) |

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study cohort at baseline.

Abbreviations: HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, high-density lipoprotein.

FIGURE 1

Flowchart of study process. Abbrevation: CAD coronary artery disease, PCSK9i proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 inhibitors.

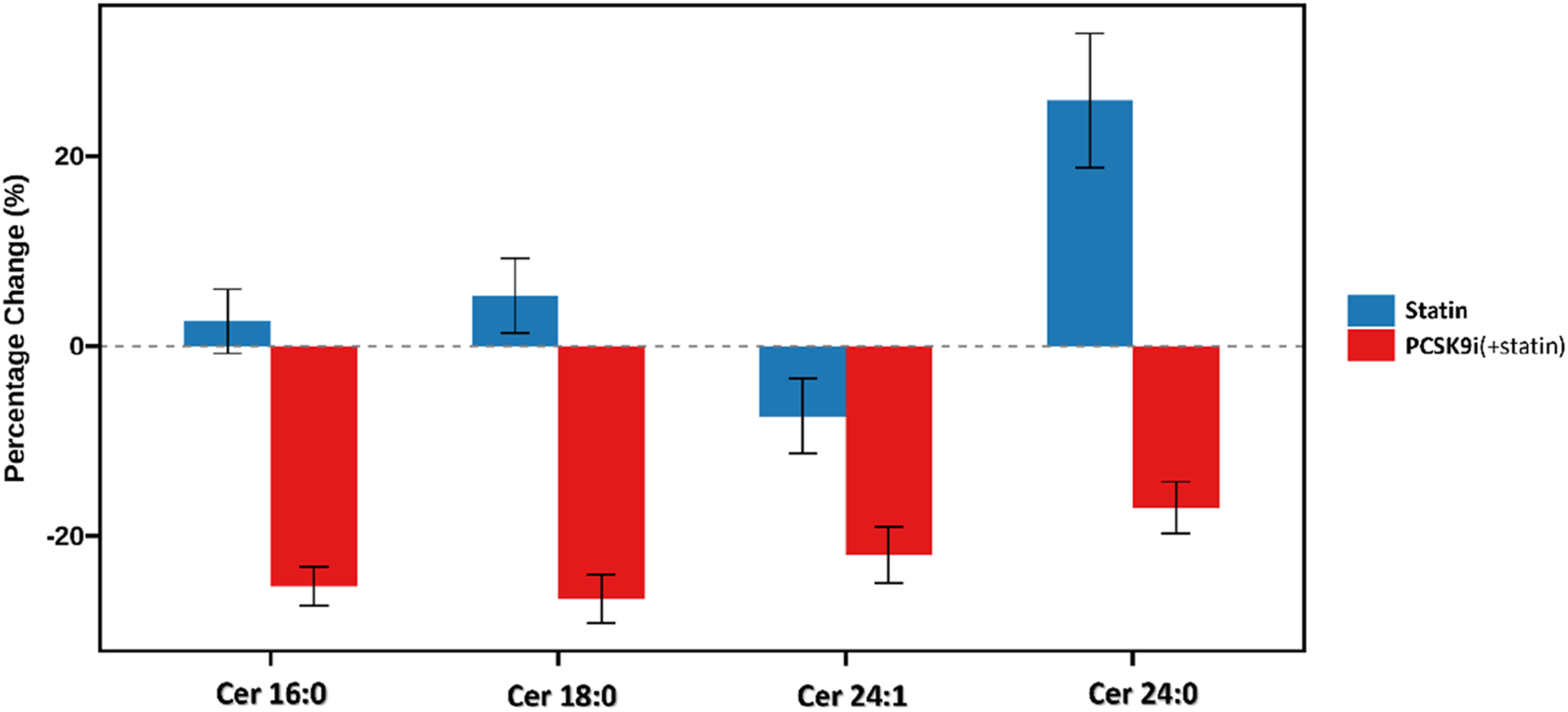

Primary efficacy end point

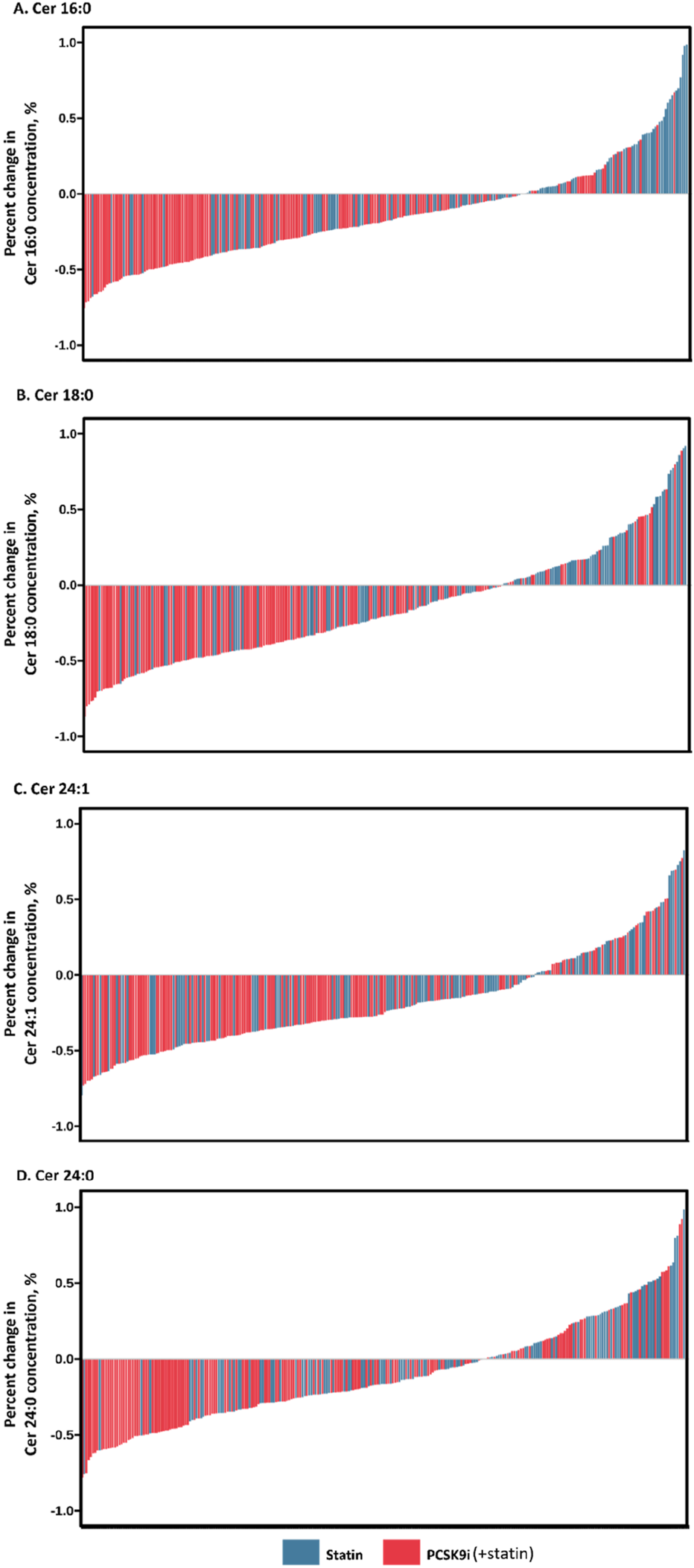

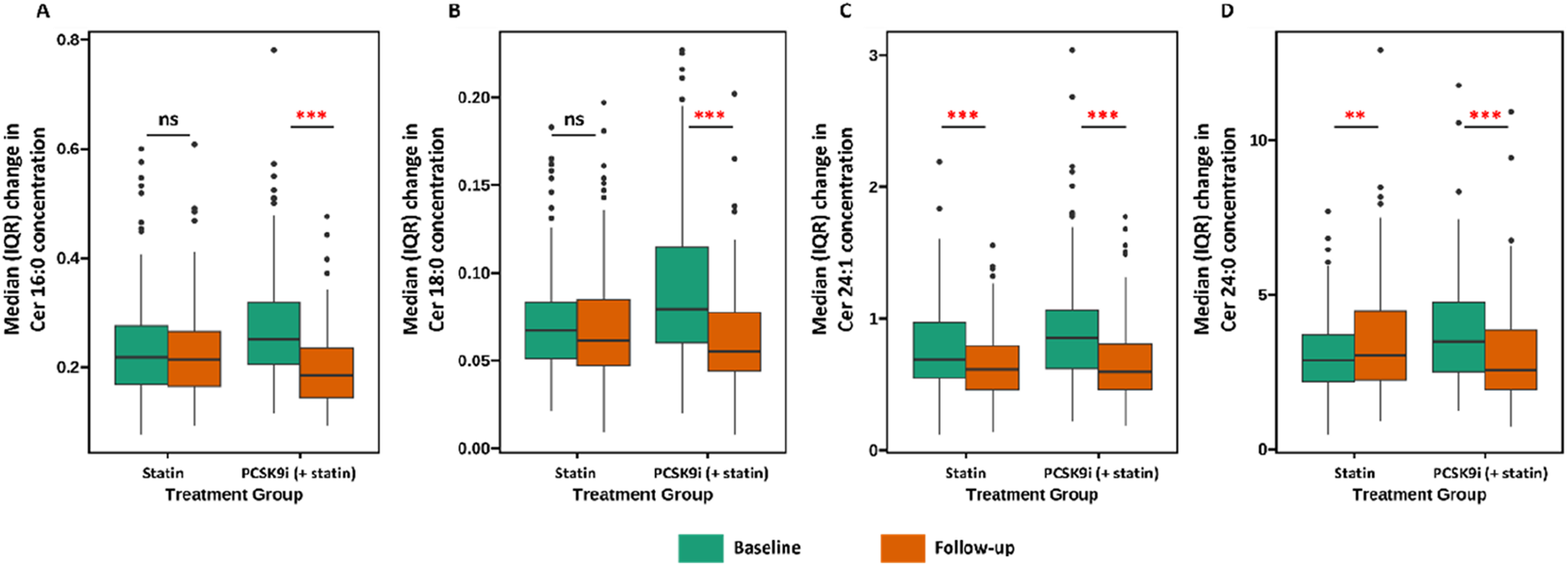

The change in Ceramide from baseline with PCSK9i and statin for the primary efficacy end points are shown in Table 2 and Figure 2. The group that received PCSK9i showed a statin-adjusted time-averaged percent change in Cer 16:0 from baseline to 4 weeks of −22.93% (95% CI, −29.73% to −16.14%). For the Cer 18:0, least-squares mean differences between PCSK9i and placebo were −24.54 (95% CI, −33.07 to −16.01. For the Cer 24:0, the LS mean change from baseline compared to placebo was −34.82% (95% CI, −48.41 to −21.23). The treatment effects of PCSK9i and statins on Cer 24:1 lowering were not significantly different (p = 0.056), and the LS mean placebo-adjusted change from baseline with PCSK9i was −8.76% (95% CI, −17.7 to 0.19). The percentage change in Ceramide from baseline with different lipid lowering therapy in individual patients is shown as a waterfall plot in Figure 3. The absolute reduction from baseline in Ceramide with PCSK9i and statin treatment only are shown in Figure 4. Changes in other atherogenic lipids are shown in Table 2 with significant mean reductions relative to statin of 29.63% in LDL-C, 16.69% in triglycerides, and 10.25% in total cholesterol. PCSK9i and statins increased high-density lipoprotein cholesterol by 3.83%, and 2.12%, respectively.

TABLE 2

| Variable | Statin, %change | PCSK9i (+statin), %change | Statin-adjusted change, LS mean % (95%CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ceramide measures at baseline, mean (SD), umol/L | ||||

| Cer 16:0 | 0.20 (0.10) | 0.30 (0.10) | NA | NA |

| LS mean changea | −0.15 | −23.09 | −22.93 (−29.73 to −16.14) | <0.001 |

| LS mean changeb | −2.59 | −25.51 | −22.91 (−32.36 to −13.46) | <0.001 |

| Cer 18:0 | 0.10 (0.03) | 0.10 (0.05) | NA | NA |

| LS mean changea | 1.19 | −23.35 | −24.54 (−33.07 to −16.01) | <0.001 |

| LS mean changeb | 5.52 | −22.89 | −28.42 (−39.00 to −17.84) | <0.001 |

| Cer 24:1 | 0.80 (0.35) | 0.90 (0.45) | NA | NA |

| LS mean changea | −10.66 | −19.41 | −8.76 (−17.70 to 0.19) | 0.056 |

| LS mean changeb | −5.79 | −17.18 | −11.40 (−22.08 to −0.72) | 0.032 |

| Cer 24:0 | 3.10 (1.29) | 3.80 (1.71) | NA | NA |

| LS mean changea | 21.37 | −13.45 | −34.82 (−48.41 to −21.23) | <0.001 |

| LS mean changeb | 21.92 | −14.82 | −36.75 (−51.58 to −21.92) | <0.001 |

| Lipid measures at baseline, mean (SD), mmol/L | ||||

| LDL cholesterol | 1.80 (0.72) | 2.50 (1.06) | NA | NA |

| LS mean changea | −4.22 | −33.85 | −29.63 (−40.27 to −18.98) | <0.001 |

| HDL cholesterol | 1.10 (0.29) | 1.10 (0.26) | NA | NA |

| LS mean changea | 3.83 | 2.12 | −1.71 (−8.71 to 5.29) | 0.632 |

| Triglycerides | 1.60 (1.24) | 2.10 (1.53) | NA | NA |

| LS mean changea | 6.9 | −9.79 | −16.69 (−25.43 to −7.96) | <0.001 |

| Total cholesterol | 3.40 (0.89) | 4.20 (1.30) | NA | NA |

| LS mean changea | −8.78 | −19.04 | −10.25 (−19.99 to −0.52) | 0.040 |

Percent changes in ceramides and other lipid parameters.

Abbreviations: HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, high-density lipoprotein; LS, least-squares.

ANCOVA, model.

Generalized Linear Mixed Model.

FIGURE 2

Percentage change in plasma ceramide concentrations after lipid-lowering therapy.

FIGURE 3

Percentage change in Ceramide concentration during month of treatment. Waterfall plots demonstrate individual absolute changes from baseline in Ceramide concentration ((A) Cer 16:0, (B) Cer 18:0, (C) Cer 24:1, (D) Cer 24:0) at month with statins and PCSK9 inhibitors.

FIGURE 4

Association between treatment (Statin vs. PCSK9i) and changes in ceramide concentration ((A) Cer 16:0, (B) Cer 18:0, (C) Cer 24:1, (D) Cer 24:0). Data are presented as medians (lines), IQRs (boxes), 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles (whiskers), and outliers (solid dots). ** (p < 0.01), *** (p < 0.001), ns (p > 0.05).

Sensitivity analyses

After PSM, 122 patients in the PCSK9i group and 122 patients in the statin group were selected (Supplementary Table 1; Supplementary Figure 1). The use of PCSK9i was associated with an absolute reduction from baseline in Ceramide compared with those with statin only (Table 3). Additionally, for the Generalized Linear Mixed Model, the effect of PCSK9i on ceramide reduction was consistent and independent of age, sex, hypertension, diabetes, and baseline values.

TABLE 3

| Variable | Statin, %change | PCSK9i (+statin), %change | Statin-adjusted change, LS mean % (95%CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ceramide measures at baseline, mean (SD), umol/L | ||||

| Cer 16:0 | 0.20 (0.10) | 0.30 (0.11) | NA | NA |

| LS mean changea | −1.75 | −20.7 | −18.95 (−26.07 to −11.83) | <0.001 |

| Cer 18:0 | 0.10 (0.03) | 0.10 (0.04) | NA | NA |

| LS mean changea | 1.53 | −21.65 | −23.18 (−32.67 to −13.70) | <0.001 |

| Cer 24:1 | 0.80 (0.35) | 0.90 (0.48) | NA | NA |

| LS mean changea | −10.8 | −19.26 | −8.46 (−17.59 to 0.66) | 0.070 |

| Cer 24:0 | 3.10 (1.27) | 3.90 (1.65) | NA | NA |

| LS mean changea | 21.42 | −12.43 | −33.86 (−49.67 to −18.04) | <0.001 |

| Lipid measures at baseline, mean (SD), mmol/L | ||||

| LDL cholesterol | 1.80 (0.71) | 2.50 (1.11) | NA | NA |

| LS mean changea | −6.48 | −30.63 | −24.15 (−36.18 to −12.12) | <0.001 |

| HDL cholesterol | 1.10 (0.24) | 1.10 (0.28) | NA | NA |

| LS mean changea | 3.66 | 2.27 | −1.39 (−9.56 to 6.77) | 0.738 |

| Triglycerides | 1.60 (1.27) | 2.10 (1.66) | NA | NA |

| LS mean changea | 8.79 | −8.48 | −17.27 (−26.85 to −7.69) | <0.001 |

| Total cholesterol | 3.40 (0.88) | 4.3 (1.35) | NA | NA |

| LS mean changea | −7.66 | −22.74 | −15.08 (−21.53 to −8.63) | <0.001 |

Percent changes in ceramides and other lipid parameters after PSM.

Abbreviations: HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, high-density lipoprotein; LS, least-squares.

ANCOVA model.

Subgroup analyses

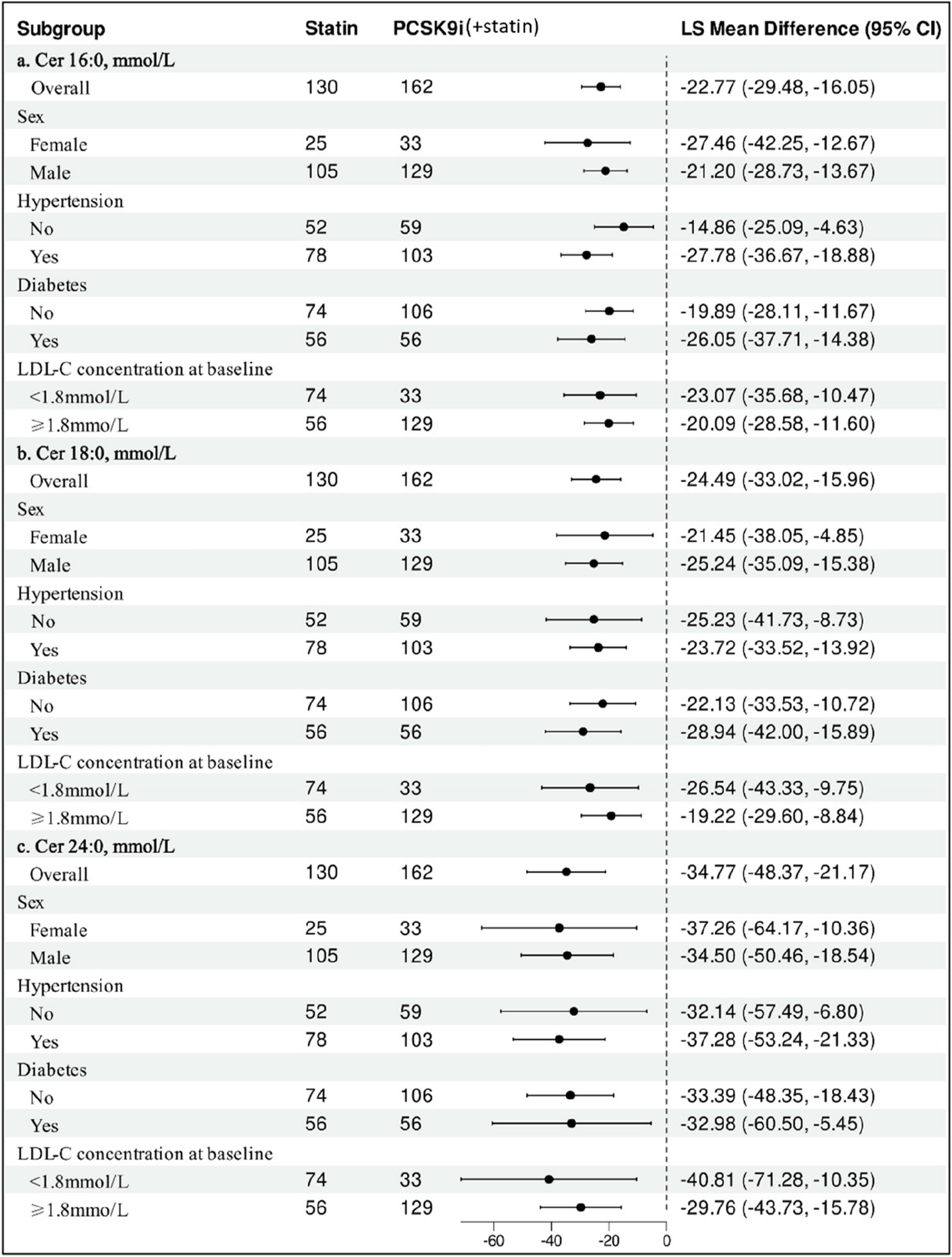

The impact of PCSK9i on change in ceramide among various subgroups is shown in Figure 5. The results remained consistent showing that PCSK9i was associated with a significant reduction of ceramide concentration.

FIGURE 5

Subgroup Analysis of Statin-adjusted Percentage Change in Ceramide from Baseline to month with PCSK9i. Data are least-squares mean differences and 95% confidence intervals. The difference in the percentage change from baseline between PCSK9i and Statin was analyzed for each subgroup with the use of a ANCOVA model after adjusting age for repeated measures.

Discussion

This retrospective study firstly demonstrated that PCSK9i was further reduced ceramide levels beyond statins in the early stage of treatment. Our data shows that PCSK9 inhibitors reduced 3 distinct cardiovascular mortality associated plasma ceramide species that consistent with previous study (Ye et al., 2020; Hilvo et al., 2018). Cer 16:0, Cer 18:0 and Cer 24:1 decreased by 23%, 23%, and 19%, respectively. The change in Cer24:0, a protective or negative lipid species, respond differently to lipid-lowering therapy is a novelty finding. Cer 24:0 concentrations were significantly elevated in subjects treated only with statins, whereas treatment with PCSK9 inhibitors resulted in a significant reduction. Previously published study reported that treatment with PCSK9 inhibitors was associated with a 20%–40% reduction in Cer 24:0 (Ye et al., 2020; Hilvo et al., 2018). Additionally, the PCSK9 loss-of-function mutation (R46L) showed a 6.4% decrease in Cer 24:0, whereas simvastatin resulted in significant (25%) reductions, as reported in the study by Laaksonen (Jänis et al., 2013). The precise mechanisms are not clear, possibly due to the significant distribution of Cer 24:0 in the non-HDL lipoprotein fractions (Hilvo et al., 2018). Statin-adjusted reduction in Cer 16:0, Cer 18:0 and Cer 24:0 of up to 22.9%, 24.5%, and 34.8%, respectively, were also observed. The effects of PCSK9 inhibitors did not show a greater reduction in Cer 24:1 when administered alongside statins. Subgroup analyses showed that PCSK9i therapy significantly reduced ceramide concentration, regardless of the sex, LDL-C at baseline, or the presence of comorbidity (hypertension and diabetes). The change in LDL-C and other lipoprotein reported here was expected and is consistent with recent studies (Filippatos et al., 2018; Sabatine et al., 2017).

Lipid-lowering treatments reduce cardiovascular risk by less than one-third, which leaves many patients still susceptible to cardiovascular-disease events (Schwartz et al., 2018; Adhyaru and Jacobson, 2018). Therefore, achieving extreme reductions in LDL-C may not be necessary, and the benefit of lipid-lowering treatment may not be limited only to LDL-C (Tokgozoglu et al., 2025). Lp(a) levels were associated with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and risk of future cardiovascular events (Arnold et al., 2024). Recent meta-analyses from the 47 RCTs have demonstrated that an average of 27% Lp(a) reduction was achieved with PCSK9i therapy (Rivera et al., 2025). Furthermore, higher baseline Lp(a) levels are linked to a greater reduction in major adverse cardiovascular events and more significant Lp(a) reduction from PCSK9i (O'Donoghue et al., 2019; Bittner et al., 2020). Trials on cardiovascular outcomes with Lp(a) reduction using directly targeting Lp(a) therapies are still ongoing (NCT05563246, NCT05537571) (Nissen et al., 2024; Nicholls et al., 2025). However, there is no therapy specifically targeting the sphingolipid pathway.

Ceramides, biologically active molecular lipids, have causal roles in the process of LDL aggregation and significantly affect the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis (Edsfeldt et al., 2016; Park et al., 2004). The presence of elevated ceramide content in LDL particles may continue to signify a substantial cardiovascular risk despite having achieved the guideline-recommended LDL-C levels. Emerging data are suggesting that high ceramide may suffer substantial residual cardiovascular risk than LDL-C. Distinct plasma ceramide are key predictors of cardiovascular death in patients with stable CAD and acute coronary syndrome (ACS), but higher LDL-C levels did not correlate with an increase in high-risk patients (Laaksonen et al., 2016). Additionally, previous study found that patients with low LDL-C (<100 mg/dL) and high ceramides had a 16% annual incidence of cardiovascular events, compared to 3.7% for those with low LDL-C and low ceramides (Meeusen et al., 2018). Studies in rodent models reveal that alleviating inflammation and robust protective effects are achieved by reducing ceramide in the heart (Hadas et al., 2020). Targeting key enzymes in the ceramide metabolism shows promise as a therapeutic strategy in preclinical models (Choi et al., 2021). It is hence plausible to hypothesize that reducing ceramide levels may hold significant potential when combined with current interventions. Given the modest but significant reduction in ceramide levels, PCSK9 inhibitors may be used in the selection of CAD patients with higher ceramide levels for individualized treatments. Whether lowering ceramide and the extent of ceramide lowering required to reduces the risk of cardiovascular events is also not known.

Potential mechanisms

The mechanisms relating changes in plasma ceramide with lipid-lowering therapy are not clear. Ceramides are produced in the liver and integrated into VLDL and LDL during its formation and release, a process partly facilitated by microsomal triglyceride transfer protein (Iqbal et al., 2015; Hammad et al., 2010). The reduction in ceramide may therefore reflect a decrease in the number of VLDL and LDL particles due to lipid-lowering therapy (Hilvo et al., 2018). Additionally, our findings indicate similar reductions in plasma Ceramide after adjusting for the LDL-C, which suggests that PCSK9i might lower plasma Ceramide through a different pathway beyond LDL-C lowering. Previous studies have demonstrated that the reduction in distinct sphingolipid species was similar for mice and humans with PCSK9 deficiency, suggesting a possible interaction between upregulation of the LDL receptor and circulating ceramide levels (Jänis et al., 2013).

Limitation

Although we have carefully defined the time period for the repeated measurements to reduce confounding bias, the post hoc power analysis indicated excellent statistical power (>0.94) for detecting differences in all ceramide species reported in the current study. However, the study still has inherent flaws typical of retrospective research. A lack of information about statin use before admission, and information on use of antihypertensive drugs or diabetic medication, may interfere with the results. Additionally, sensitivity analysis and subgroup analysis were also consistent with the main analysis. Residual confounding by unmeasured or poorly measured factors, such as dietary changes and exercise intensity, may also impact changes in ceramide concentrations (Mathews et al., 2017; Reidy et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2017). The last concern is the imbalance of genders in the research sample. Larger studies, and longer exposure time are necessary to clarify whether changes in ceramide profiles affect the risk of progression of atherosclerosis and cardiovascular events.

Conclusion

The present study demonstrate that PCSK9 inhibitors effectively decreased levels of distinct ceramides in patients with CAD while receiving statins. These findings strengthen the understanding of pathophysiologic mechanisms by which PCSK9 inhibitors affect sphingolipid pathway and have provided novelty insight for the design of drugs targeting the reduction of ceramides.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Beijing Anzhen Hospital, Capital Medical University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

LZ: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft. YD: Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Writing – review and editing. YZ: Funding acquisition, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 82270345). All other authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphar.2025.1726925/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

ACS, Acute Coronary Syndrome; ANCOVA, Analysis of covariance; CAD, Coronary Artery Disease; CI, Confidence Intervals; GPCRs, G-Protein-Coupled Receptors; HDL-C, High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol; LDL-C, Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol; LS, Least-Squares; PCSK9i, Proprotein Convertase Subtilisin/Kexin type 9 inhibitors; PSM, Propensity Score Matching; TC, Total Cholesterol; TG, Triglycerides; VLDL, Very Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol.

References

1

Adhyaru B. B. Jacobson T. A. (2018). Safety and efficacy of statin therapy. Nat. Rev. Cardiol.15 (12), 757–769. 10.1038/s41569-018-0098-5

2

Arnold N. Blaum C. Goßling A. Brunner F. J. Bay B. Ferrario M. M. et al (2024). C-reactive protein modifies lipoprotein(a)-related risk for coronary heart disease: the BiomarCaRE project. Eur. Heart J.45 (12), 1043–1054. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehad867

3

Bharath L. P. Ruan T. Li Y. Ravindran A. Wan X. Nhan J. K. et al (2015). Ceramide-initiated protein phosphatase 2A activation contributes to arterial dysfunction in vivo. Diabetes64 (11), 3914–3926. 10.2337/db15-0244

4

Bittner V. A. Szarek M. Aylward P. E. Bhatt D. L. Diaz R. Edelberg J. M. et al (2020). Effect of alirocumab on Lipoprotein(a) and cardiovascular risk after acute coronary syndrome. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol.75 (2), 133–144. 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.10.057

5

Chaurasia B. Tippetts T. S. Mayoral M. R. Liu J. Li Y. Wang L. et al (2019). Targeting a ceramide double bond improves insulin resistance and hepatic steatosis. Science365 (6451), 386–392. 10.1126/science.aav3722

6

Choi R. H. Tatum S. M. Symons J. D. Summers S. A. Holland W. L. (2021). Ceramides and other sphingolipids as drivers of cardiovascular disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol.18 (10), 701–711. 10.1038/s41569-021-00536-1

7

Edsfeldt A. Dunér P. Ståhlman M. Mollet I. G. Asciutto G. Grufman H. et al (2016). Sphingolipids contribute to human atherosclerotic plaque inflammation. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol.36 (6), 1132–1140. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.116.305675

8

Emma M. R. Giannitrapani L. Cabibi D. Porcasi R. Pantuso G. Augello G. et al (2020). Hepatic and circulating levels of PCSK9 in morbidly obese patients: relation with severity of liver steatosis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids1865 (12), 158792. 10.1016/j.bbalip.2020.158792

9

Filippatos T. D. Kei A. Rizos C. V. Elisaf M. S. (2018). Effects of PCSK9 inhibitors on other than low-density Lipoprotein cholesterol lipid variables. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. Ther.23 (1), 3–12. 10.1177/1074248417724868

10

Hadas Y. Vincek A. S. Youssef E. Żak M. M. Chepurko E. Sultana N. et al (2020). Altering sphingolipid metabolism attenuates cell death and inflammatory response after myocardial infarction. Circulation141 (11), 916–930. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.041882

11

Hammad S. M. Pierce J. S. Soodavar F. Smith K. J. Al Gadban M. M. Rembiesa B. et al (2010). Blood sphingolipidomics in healthy humans: impact of sample collection methodology. J. Lipid Res.51 (10), 3074–3087. 10.1194/jlr.D008532

12

Hilvo M. Simolin H. Metso J. Ruuth M. Öörni K. Jauhiainen M. et al (2018). PCSK9 inhibition alters the lipidome of plasma and lipoprotein fractions. Atherosclerosis269, 159–165. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2018.01.004

13

Iqbal J. Walsh M. T. Hammad S. M. Cuchel M. Tarugi P. Hegele R. A. et al (2015). Microsomal triglyceride transfer protein transfers and determines plasma concentrations of ceramide and sphingomyelin but not glycosylceramide. J. Biol. Chem.290 (43), 25863–25875. 10.1074/jbc.M115.659110

14

Jänis M. T. Tarasov K. Ta H. X. Suoniemi M. Ekroos K. Hurme R. et al (2013). Beyond LDL-C lowering: distinct molecular sphingolipids are good indicators of PCSK9 deficiency. Atherosclerosis228 (2), 380–385. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2013.03.029

15

Klug E. Q. Llerena S. Burgess L. J. Fourie N. Scott R. Vest J. et al (2024). Efficacy and safety of lerodalcibep in patients with or at high risk of cardiovascular disease: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Cardiol.9 (9), 800–807. 10.1001/jamacardio.2024.1659

16

Laaksonen R. Ekroos K. Sysi-Aho M. Hilvo M. Vihervaara T. Kauhanen D. et al (2016). Plasma ceramides predict cardiovascular death in patients with stable coronary artery disease and acute coronary syndromes beyond LDL-cholesterol. Eur. Heart J.37 (25), 1967–1976. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw148

17

Mach F. Koskinas K. C. Roeters van Lennep J. E. Tokgözoğlu L. Badimon L. Baigent C. et al (2025). ESC/EAS scientific document group. 2025 focused update of the 2019 ESC/EAS guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias. Eur. Heart J.46 (42), 4359–4378. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaf190

18

Mathews A. T. Famodu O. A. Olfert M. D. Murray P. J. Cuff C. F. Downes M. T. et al (2017). Efficacy of nutritional interventions to lower circulating ceramides in young adults: FRUVEDomic pilot study. Physiol. Rep.5, e13329. 10.14814/phy2.13329

19

Meeusen J. W. Donato L. J. Bryant S. C. Baudhuin L. M. Berger P. B. Jaffe A. S. (2018). Plasma ceramides. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol.38 (8), 1933–1939. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.118.311199

20

Ng T. W. Ooi E. M. Watts G. F. Chan D. C. Weir J. M. Meikle P. J. et al (2014). Dose-dependent effects of rosuvastatin on the plasma sphingolipidome and phospholipidome in the metabolic syndrome. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab.99 (11), E2335–E2340. 10.1210/jc.2014-1665

21

Nicholls S. J. Ni W. Rhodes G. M. Nissen S. E. Navar A. M. Michael L. F. et al (2025). Oral muvalaplin for lowering of Lipoprotein(a): a randomized clinical trial. JAMA333 (3), 222–231. 10.1001/jama.2024.24017

22

Nissen S. E. Wang Q. Nicholls S. J. Navar A. M. Ray K. K. Schwartz G. G. et al (2024). Zerlasiran—A small-interfering RNA targeting lipoprotein(a): a phase 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA332 (23), 1992–2002. 10.1001/jama.2024.21957

23

O'Donoghue M. L. Fazio S. Giugliano R. P. Stroes E. S. G. Kanevsky E. Gouni-Berthold I. et al (2019). Lipoprotein(a), PCSK9 inhibition, and cardiovascular risk. Circulation139 (12), 1483–1492. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.037184

24

Park T. S. Panek R. L. Mueller S. B. Hanselman J. C. Rosebury W. S. Robertson A. W. et al (2004). Inhibition of sphingomyelin synthesis reduces atherogenesis in apolipoprotein E-knockout mice. Circulation110 (22), 3465–3471. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000148370.60535.22

25

Reidy P. T. Mahmassani Z. S. McKenzie A. I. Petrocelli J. J. Summers S. A. Drummond M. J. (2020). Influence of exercise training on skeletal muscle insulin resistance in aging: spotlight on muscle ceramides. Int. J. Mol. Sci.21, 1514. 10.3390/ijms21041514

26

Reijnders E. Bossuyt P. M. Jukema J. W. Ruhaak L. R. Romijn F. P. H. T. M. Szarek M. et al (2025). Multiplex Apolipoprotein panel improves cardiovascular event prediction and cardiovascular outcome by identifying patients who benefit from targeted PCSK9 inhibitor therapy. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol.45 (11), 2111–2123. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.124.322336

27

Rivera F. B. Cha S. W. Linnaeus L. C. Carado G. P. Magalong J. V. Tang V. A. et al (2025). Impact of proprotein convertase Subtilisin/Kexin type 9 inhibitors on Lipoprotein(a): a meta-analysis and meta-regression of randomized controlled trials. JACC Adv.4 (2), 101549. 10.1016/j.jacadv.2024.101549

28

Sabatine M. S. Giugliano R. P. Keech A. C. Honarpour N. Wiviott S. D. Murphy S. A. et al (2017). Evolocumab and clinical outcomes in patients with cardiovascular disease. N. Engl. J. Med.376 (18), 1713–1722. 10.1056/NEJMoa1615664

29

Schwartz G. G. Steg P. G. Szarek M. Bhatt D. L. Bittner V. A. Diaz R. et al (2018). Alirocumab and cardiovascular outcomes after acute coronary syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med.379 (22), 2097–2107. 10.1056/NEJMoa1801174

30

Summers S. A. Chaurasia B. Holland W. L. (2019). Metabolic messengers: ceramides. Nat. Metab.1 (11), 1051–1058. 10.1038/s42255-019-0134-8

31

Tarasov K. Ekroos K. Suoniemi M. Kauhanen D. Sylvänne T. Hurme R. et al (2014). Molecular lipids identify cardiovascular risk and are efficiently lowered by simvastatin and PCSK9 deficiency. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab.99 (1), E45–E52. 10.1210/jc.2013-2559

32

Tokgozoglu L. Orringer C. Catapano A. L. (2025). The year in cardiovascular medicine 2024: the top 10 papers in dyslipidaemias. Eur. Heart J.46 (15), 1412–1414. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaf077

33

Wang D. D. Toledo E. Hruby A. Rosner B. A. Willett W. C. Sun Q. et al (2017). Plasma ceramides, mediterranean diet, and incident cardiovascular disease in the PREDIMED trial (prevención con dieta mediterránea). Circulation135, 2028–2040. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.024261

34

Ye Q. Svatikova A. Meeusen J. W. Kludtke E. L. Kopecky S. L. (2020). Effect of proprotein convertase Subtilisin/Kexin type 9 inhibitors on plasma ceramide levels. Am. J. Cardiol.128, 163–167. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2020.04.052

35

Zhang L. Tan D. Zhang Y. Ding Y. Liang H. Zhang G. et al (2023). Ceramides and metabolic profiles of patients with acute coronary disease: a cross-sectional study. Front. Physiol.14, 1177765. 10.3389/fphys.2023.1177765

36

Zhang S. Lin H. Wang J. Rui J. Wang T. Cai Z. et al (2025). Sensing ceramides by CYSLTR2 and P2RY6 to aggravate atherosclerosis. Nature641 (8062), 476–485. 10.1038/s41586-025-08792-8

Summary

Keywords

PCSK9 inhibitors, statin, ceramide, coronary artery disease, lipid

Citation

Zhang L, Ding Y and Zeng Y (2025) Differential effects of PCSK9 inhibitors and statins on plasma ceramides in coronary artery disease. Front. Pharmacol. 16:1726925. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2025.1726925

Received

17 October 2025

Revised

23 November 2025

Accepted

03 December 2025

Published

18 December 2025

Volume

16 - 2025

Edited by

Prasanth Puthanveetil, Midwestern University, United States

Reviewed by

Rosaria Vincenza Giglio, University of Palermo, Italy

Tilla Worgall, Columbia University, United States

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Zhang, Ding and Zeng.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yong Zeng, zy_anzhen@163.com

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.