Abstract

Background:

Imipenem is a broad-spectrum carbapenem antibiotic for severe infections with significant pharmacokinetic (PK) variability. This review systematically synthesized published population pharmacokinetic (popPK) studies to identify key covariates and guide individualized dosing for patients with various conditions.

Methods:

A systematic PubMed and Web of Science search identified imipenem popPK models. Studies employing nonlinear mixed-effects modeling in patients with various conditions were included, and data were extracted independently by two reviewers via a standardized form. The study characteristics and PK parameter estimates were compared.

Results:

This systematic review of 18 popPK studies revealed that imipenem PKs were predominantly characterized by two-compartment models. The clearance of imipenem varied from 4.79 to 16.2 L/h in adults. Creatinine clearance (CLcr) was the most consistent and significant covariate for imipenem clearance, whereas body weight (BW) was frequently identified for volume of distribution. Other clinically relevant covariates, including the glomerular filtration rate (GFR), age, and serum ALB level, were also incorporated into the final models for specific patient subpopulations. All models applied internal validations, such as bootstrap and visual predicative check, but only three studies performed external validation.

Conclusion:

This review systematically integrates existing popPK models of imipenem, highlighting renal function and BW as key covariates. This study provides valuable insights for individualized dosing while identifying critical research gaps, particularly the need for external validation and focused studies in special populations.

1 Introduction

Imipenem, a broad-spectrum carbapenem antibiotic, possesses potent antibacterial activity against a diverse range of gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria, as well as anaerobic organisms (Dingle and Pitout, 2022). Its bactericidal action is mediated through the inhibition of bacterial cell wall synthesis (O’Donnell and Lodise, 2022). In the clinic, imipenem is widely utilized for the management of severe bacterial infections, including sepsis, pneumonia, intra-abdominal infections, and urinary tract infections (Chang et al., 2023; Fratoni et al., 2022; Heo, 2021; Marino et al., 2025; Titov et al., 2021). The primary objective of its dosing regimen is to maximize the duration during which plasma concentrations exceed the pathogen’s minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) (Song et al., 2025). Consequently, imipenem is commonly coadministered with cilastatin, a renal dehydropeptidase inhibitor, to prevent renal metabolism and inactivation, thereby ensuring that a sufficient amount of intact drug reaches the target site and maintains excellent clinical efficacy (Zhanel et al., 2018).

Despite its strong antibacterial potency, the clinical use of imipenem is accompanied by a range of noteworthy adverse effects. An analysis of 2,574 adverse event reports related to imipenem revealed that over half of the events involved individuals aged over 60 years. Previously unreported adverse reactions, including brain atrophy and delirium, have also been identified (Jia et al., 2025). Among the most concerning adverse effects is dose-dependent central neurotoxicity (Sutter et al., 2015). Reported potential targets for carbapenem-induced neurotoxicity include the GABAA receptor, glutathione S-transferase Pi, glutathione S-transferase Mu 1, and glutathione S-transferase A2 (de Lima et al., 2025). The incidence of this complication is significantly elevated in patients receiving high doses, those with renal impairment leading to drug accumulation, and individuals with preexisting central nervous system disorders (Miller et al., 2011). Furthermore, similar to other β-lactam antibiotics, imipenem may induce gastrointestinal disturbances, allergic manifestations such as skin rashes, and occasional eosinophilia (Foong et al., 2016; Hamao et al., 2025; Sivanandy et al., 2024). Notably, although cilastatin is employed to inhibit renal organic anion transporters (OATs) and prevent imipenem-induced nephrotoxicity, imipenem/cilastatin administration has been associated with alkaline urine, polyuria, crystalluria, and elevated plasma levels of urea, creatinine, and uric acid, indicating that potential nephrotoxic risk still requires close monitoring (Huo et al., 2019; Tahri et al., 2018). A more serious long-term challenge is the emergence and dissemination of carbapenem-resistant strains driven by inappropriate and extensive use, particularly when drug exposure remains at subtherapeutic levels for prolonged periods, exerting substantial selective pressure and posing a significant threat to global public health (Lechtig-Wasserman et al., 2021).

Given the complexities associated with its clinical application, the pharmacokinetic (PK) profile of imipenem is highly important. This antibiotic exhibits time-dependent bactericidal activity, the efficacy of which is commonly quantified by %fT>MIC, the percentage of the dosing interval during which plasma concentrations exceed the MIC (Fratoni et al., 2023; Khan et al., 2025). Accordingly, a precise understanding of its PK behavior and the maintenance of adequate drug exposure duration are essential for optimizing therapeutic outcomes and preventing the emergence of resistance. In clinical practice, significant interindividual and intraindividual variability in imipenem PK has been observed (Zou et al., 2019). This variability may be influenced by multiple factors, including patient age, body weight (BW), renal function, comorbid conditions, and drug‒drug interactions. For example, impaired renal function can lead to reduced drug clearance and subsequent drug accumulation (Bricheux et al., 2018). However, in patients with obesity, the volume of drug distribution tends to increase, potentially necessitating adjustments to the dosing regimen to maintain effective plasma drug concentrations (Chen et al., 2024). Furthermore, variations in drug concentrations across different infection sites can impact treatment efficacy (Alikhani et al., 2025). Such PK variability presents substantial challenges for appropriate clinical use, highlighting the urgent need to develop individualized dosing strategies that ensure both efficacy and safety.

To address these challenges, population pharmacokinetic (popPK) modeling offers a valuable methodological approach. PopPK utilizes sparsely collected data from routine clinical settings and applies nonlinear mixed-effects models to simultaneously estimate typical population parameter values (fixed effects) as well as interindividual and residual variability (random effects) (Yao et al., 2025). This enables a deeper understanding of the key factors driving PK differences within specific patient subgroups. Although many studies have been conducted to develop popPK models for imipenem, these investigations are dispersed across diverse patient populations. The final model structures and the significant covariates identified often vary, and a systematic integration and comparison are currently lacking. Therefore, this review aims to comprehensively synthesize and systematically evaluate published popPK studies on imipenem. It focuses on assessing and analyzing the structural model employed, the key covariates identified along with their quantitative influences, and comparing the application and validation of these models across various special populations.

2 Methods

2.1 Search of published population pharmacokinetic models

A systematic literature search was performed via PubMed and Web of Science to identify published popPK models of imipenem. The search covered the period from database inception until August 2025. The following key terms were used: “imipenem” AND (“population pharmacokinetics” OR “population pharmacokinetic” OR “pharmacokinetic analysis” OR “pharmacokinetic model” OR “NONMEM” OR “nonlinear mixed effect model”). All the retrieved articles were thoroughly reviewed and cross-verified by two independent investigators.

2.2 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were included if they met the following criteria: (1) involved human subjects receiving imipenem therapy (healthy volunteers or patients); (2) employed nonlinear mixed-effects modeling for pharmacokinetic analysis; (3) provided a complete popPK model description; and (4) were published in English.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) studies using noncompartmental or nonparametric methods; (2) non-research study or secondary publications; (3) insufficient details on model structure or parameter estimates; (4) studies limited to external validation of existing models; (5) applications of previously published models without new modeling efforts; and (6) studies focused on combinations other than imipenem-cilastatin, such as imipenem-cilastatin-relebactam.

2.3 Data extraction

Data were extracted independently by two reviewers via a predesigned standardized form. Any discrepancies were resolved through discussion or by a third reviewer. The extracted information included the following: (1) study design features: year of publication, country, study type (prospective/retrospective), population description, sample size, dosing regimen, sampling schedule, bioanalytical methodology, etc.; (2) participant demographics: age, sex, BW, etc.; and (3) popPK model characteristics: compartmental model, software used, model evaluation techniques, parameter estimates, and significant covariates, etc.

3 Results

3.1 Literature search and study inclusion

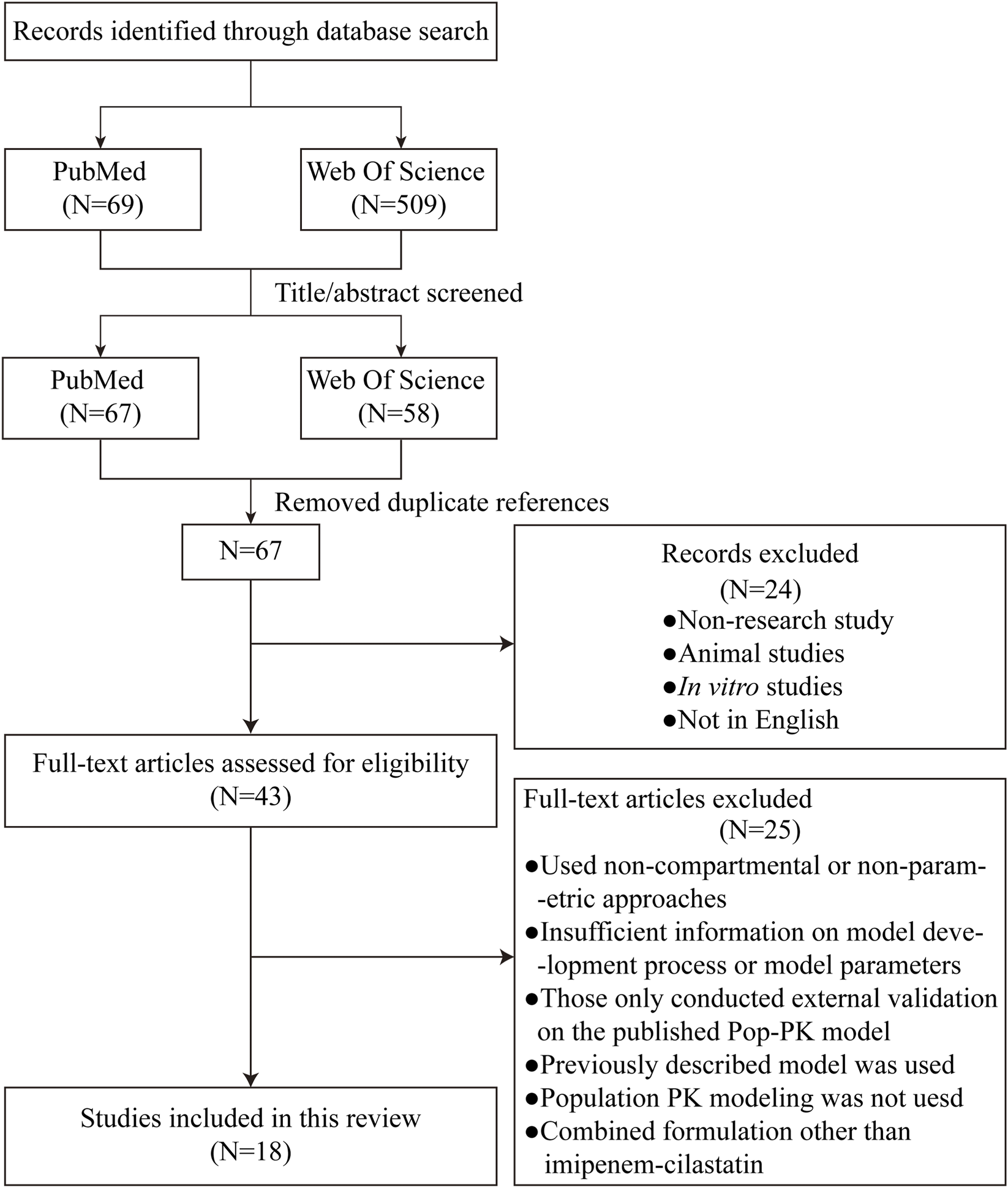

A total of 69 (PubMed) and 509 (Web of Science) potentially relevant articles were initially identified through the implemented search strategies. After screening the titles and abstracts, 67 (PubMed) and 58 (Web of Science) articles remained for further evaluation. After removing duplicates and performing a full-text assessment, 18 studies meeting the inclusion criteria were ultimately included in this review (Bai et al., 2024; Chen et al., 2020b; Couffignal et al., 2014; Dao et al., 2022; de Velde et al., 2020; Dinh et al., 2022; Dong et al., 2019; Ikawa et al., 2008; Jaruratanasirikul et al., 2021; Lafaurie et al., 2023; Lamoth et al., 2009; Li and Xie, 2019; Li et al., 2020; Nguyen et al., 2021; Por et al., 2021; Truong et al., 2025; Wang et al., 2024; Yoshizawa et al., 2013) (Figure 1). The key characteristics of these selected studies are summarized in Table 1. The included patients were from 10 different countries. Five studies were conducted in China, two in France, two in Japan, two in Switzerland, two in the Netherlands, and two in Vietnam. In the view of study design, 10 studies are prospective and the other 8 are retrospective. Single studies were reported from Belgium, Thailand, and the United States. The publication years of these articles spanned from 2008 to 2025. Considerable variation in sample size was observed across the studies, ranging from 10 patients (Ikawa et al., 2008) to 247 patients (Chen et al., 2020b), but the sample sizes for most studies are limited. The study populations were predominantly composed of critically ill patients; however, several studies have focused on specific groups, such as patients with burns, abdominal infections, hematological malignancies, or neutropenia. Patients with organ support, such as CRRT and ECMO, were also analyzed. Additionally, the target populations were not limited to adults but also included neonates and children.

FIGURE 1

Flow chart of the article retrieval and screening process.

TABLE 1

| Study | Author and year | Country | Study type | Patient group | Number of patients | Sample size |

Gender (M/F) |

Age (year) | Weight (kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ikawa et al. (2008) | Japan | Prospective | Patients with intraabdominal infections | 10 | NR | NR | 43.7 ± 14.9 | 56.7 ± 10.5 |

| 2 | Lamoth et al. (2009) | Switzerland | Retrospective | Febrile Neutropenic Patients with Hematological Malignancies | 57 | 159 | 44/13 | 58 (17–78) | 73 (41–135) |

| 3 | Yoshizawa et al. (2013) | Japan | Retrospective | Neonates and children | Neonates: 60 Children: 39 |

Neonates: blood: 335 urinary: 108 Children: blood: 230 urinary: 155 |

Neonates: 30/30; Children: 26/13 |

Neonates: 0.0288 ± 0.0227; Children: 9.61 ± 3.16 |

Neonates: 2.93 ± 0.7 Children: 29.5 ± 10.9 |

| 4 | Couffignal et al. (2014) | France | Prospective | Critically ill patients with suspected ventilator-associated pneumonia | 51 | 297 | 41/10 | 60 (28–84) | 77 (45–126) |

| 5 | Li and Xie (2019) | Belgium | Retrospective | Critically Ill patients with CRRT | 20 | 134 | 16/4 | 55.5 (42.8–69.8) | 72 (62.5–82.5) |

| 6 | Dong et al. (2019) | China | Prospective | Children with hematological malignancies | 56 | 136 | 30/26 | 4.86 ± 2.33 | 18.65 ± 6.90 |

| 7 | Li et al. (2020) | China | Prospective | Critically Ill patients with CRRT | 30 | blood: 209 effluent: 174 |

23/7 | 61.67 ± 19.77 | 70.2 ± 13.68 |

| 8 | Chen et al. (2020b) | China | Retrospective | Critically Ill patients with/without ECMO | 247 | 580 | 167/80 | 67 (20–97) | 65 (37.5–110.0) |

| 9 | de Velde et al. (2020) | Netherlands | Retrospective | Critically ill patients | 26 | 138 | 18/8 | 51 (39–54) | 75 (66–85) |

| 10 | Nguyen et al. (2021) | Vietnam | Prospective | AECOPD | 44 | 84 | 41/3 | 65 (60-72) | 50 (47–55) |

| 11 | Jaruratanasirikul et al. (2021) | Thailand | Prospective | Critically ill patients with/without ECMO | 50 | 534 | 35/15 | 56.2 (40.95–66.6) | 62.9 (52.8–70.0) |

| 12 | Por et al. (2021) | USA | Prospective | Burn patients with/without CVVH | 23 | 81 | 6/17 | With CVVH: 55 ± 19.99 Without CVVH: 51.09 ± 19.03 |

With CVVH: 89.6 ± 22.38 Without CVVH: 105.06 ± 28.66 |

| 13 | Dao et al. (2022) | Switzerland | Retrospective | Neonates | 82 | 173 | 38/44 | GA: 26.9 (24.2–41.3) w PNA: 21 (2.1–153) d PMA: 31 (25.6–48.3) w |

1.16 (0.5–4.1) |

| 14 | Dinh et al. (2022) | Vietnam | Prospective | Critically-Ill patients | 24 | 139 | 18/6 | 57.5 ± 19.9 | 51.3 ± 8.6 |

| 15 | Bai et al. (2024) | China | prospective | Critically Ill sepsis | 51 | 196 | 33/18 | 56.45 ± 18.76 | 70.21 ± 72.01 |

| 16 | Lafaurie et al. (2023) | France | Prospective | Neutropenic adult patients | 16 | 118 | 7/9 | 37 (18.3–78.3) | 65.5 (48–101) |

| 17 | Truong et al. (2025) | Netherlands | Retrospective | Critically ill and non-critically ill patients | 151 | 322 | 151/0 | 63 (51–72) | 70 (61.2–82) |

| 18 | Wang et al. (2024) | China | Retrospective | Elderly patients | 120 | 370 | 78/42 | 72 (68, 81) | 65 (59, 65.33) |

Demographics of patients for all population pharmacokinetic studies included in this review.

The age and weight values are presented as the means ± SDs or medians (ranges). USA, United States of America; M/F, Male/Female; AECOPD, Acute Exacerbations of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; w, week; d, day; CRRT, Continuous Renal Replacement Therapy; CVVH, continuous venous hemofiltration; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; GA, gestational age; PNA, postnatal age; PMA, Postmenstrual age; NR, no record.

As presented in Supplementary Table S1, the recommended therapeutic dose of imipenem for most adult patients with infections is 1,000–2,000 mg per day, which is administered in three to four intravenous infusions. For children and neonates weighing less than 40 kg, a dosage of 15 mg/kg every 6 h is recommended, with a maximum daily dose not exceeding 2 g. In the present review, the majority of the dosing regimens were consistent with these recommendations; however, five studies (Dinh et al., 2022; Jaruratanasirikul et al., 2021; Li and Xie, 2019; Por et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2024) reported a maximum daily dose of 4,000 mg. Furthermore, the imipenem dosage was not specified in Truong et al. (2025) Study. The timing of sample collection varied considerably across the studies. For example, in Wang et al. (2024) Study, only trough concentration samples were collected, whereas in de Velde et al. (2020) Study, blood samples were obtained at peak, intermediate, and trough time points. The remaining studies collected samples at multiple time points. Nearly all studies employed high-performance liquid chromatography with ultraviolet detection (HPLC-UV) for the quantification of imipenem concentrations in blood samples. An exception was Lamoth et al. (2009) Study, which utilized HPLC alone, and Chen et al., (2020b) Study and Dao et al. (2022) Study, in which liquid chromatography‒tandem mass spectrometry (LC‒MS/MS) was applied.

3.2 Population pharmacokinetic analyses

PopPK modeling approaches across the included studies are summarized in Table 2. The most frequently employed software was NONMEM, which was applied in 11 investigations to generate popPK models (Chen et al., 2020b; Dao et al., 2022; de Velde et al., 2020; Dong et al., 2019; Ikawa et al., 2008; Jaruratanasirikul et al., 2021; Lamoth et al., 2009; Li and Xie, 2019; Truong et al., 2025; Wang et al., 2024; Yoshizawa et al., 2013). In contrast, Monolix was used in four studies (Couffignal et al., 2014; Dinh et al., 2022; Lafaurie et al., 2023; Nguyen et al., 2021). Alternative tools included Phoenix NLME, which was implemented in two studies, and Pumas, which was utilized in one study (Bai et al., 2024; Li et al., 2020; Por et al., 2021). Model evaluation relied on both basic and advanced internal validation techniques. Most studies had performed internal validation. Goodness-of-fit (GOF) plots are routinely examined, and methods such as bootstrapping and visual predictive checks (VPCs) are also commonly employed to assess model robustness. In contrast, only three studies had performed external validation. By employing an independent dataset distinct from the modeling data for validation, it is possible to transcend the limitations of the model’s original application scope, thereby enhancing its predictive stability in real-world settings. Structurally, one- and two-compartment models are predominantly used to characterize imipenem pharmacokinetics. In particular, the one-compartment model is often preferred in clinical population analyses because it could describe imipenem elimination based on sparse data. However, a three-compartment model was implemented in Li et al. (2020) Study and Ikawa et al. (2008) Study to characterize the PK profile of imipenem.

TABLE 2

| Study | Author and year | Compartments | Population typical value | Inter-individual variability (IIV) | Residual variability (RV) | Model evaluation method | Software |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ikawa et al. (2008) | 3-CMT | CL: 9.42 L/h V1: 4.66 L V2: 5.08 L V3: 4.57 L Q2: 5.74 L/h Q3: 31.6 L/h |

CL: 26.9% V1: 47.5% V2: 37.1% V3: 86.2% |

Additive: 1.13 mg/L | NR | NONMEM Crystal Ball 2000 |

| 2 | Lamoth et al. (2009) | 1-CMT | CL: 16.2 L/h V: 33.5 L |

CL: 17% | Residual error: 59% | NR | NONMEM |

| 3 | Yoshizawa et al. (2013) | Neonates 1-CMT Children 2-CMT |

Neonates CLr: 0.0783 L/h/kg CLnr: 0.138 L/h/kg V: 0.466 L/kg Children CLr: 0.187 L/h/kg CLnr: 0.0711 L/h/kg V1: 0.203 L/kg V2: 0.0569 L/kg Q: 0.0621 L/h/kg |

Neonates CLr: 39.2% CLnr: 33.4% Children CLr: 17.7% CLnr: 39.5% V1: 17.1% |

Neonates Proportional: 25.2% Additive: 0.483 mg/L Children Proportional: 27.9% |

GOF parameter sensitivity leverage analyses VPC |

NONMEM |

| 4 | Couffignal et al. (2014) | 2-CMT | CL: 13.2 L/h V1: 20.4 L V2: 9.8 L Q: 12.2 L/h |

CL: 38% V1: 31% |

Proportional: 33% | GOF VPC NPDE Bootstrap |

Monolix |

| 5 | Li and Xie (2019) | 1-CMT | CLbody: 6.11 L/h Vd: 34.2 L |

CLbody: 36.6% Vd: 47.2% |

Proportional: 26.3% | pcVPC NPDE SIR GOF |

NONMEM |

| 6 | Dong et al. (2019) | 2-CMT | CL: 8.6 L/h Q: 0.996 L/h V1: 7.2 L V2: 6.51 L |

CL: 18.8% V1: 9.2% |

Proportional: 39.5% Additive: 0.205 mg/L |

Bootstrap GOF NPDE |

NONMEM |

| 7 | Li et al. (2020) | 3-CMT | CLc: 8.825 L/h CLd: 0.093 L/h Qcp: 1.572 L/h Qcd: 0.392 L/h Vc: 24.264 L Vp: 33.035 L Vd: 0.012 L |

CLc: 35.394% CLd: 31.624% Qcp: 156.718% Vc: 54.996% Vp: 97.659% |

Plasma Proportional: 23.655% Additive: 0.584 mg/L Effluent Proportional: 43.652% Additive: 0.384 mg/L |

Bootstrap VPC |

Phoenix NLME |

| 8 | Chen et al. (2020b) | 2-CMT | CL: 8.88 L/h Q: 1.74 L/h V1: 20.5 L V2: 8.86 L |

CL: 17.7% V1: 14.8% |

Proportional: 6.2% Additive: 0.003 mg/L |

Bootstrap VPC GOF |

NONMEM |

| 9 | de Velde et al. (2020) | 2-CMT | NONMEM Ke: 0.637 h−1 Kcp: 0.166 h−1 Kpc: 0.195 h−1 Vc: 29.6 L Pmetrics Ke: 0.681 h−1 Kcp: 0.374 h−1 Kpc: 0.495 h−1 Vc: 31.1 L |

NONMEM Ke: 19% Pmetrics Ke: 34% Kcp: 81.2% Kpc: 72% Vc: 42.6% |

NONMEM Proportional: 34.8% Pmetrics Gamma: 3.4 |

VPC NPC GOF Bootstrap |

NONMEM and Pmetrics |

| 10 | Nguyen et al. (2021) | 1-CMT | CL: 7.88 L/h V: 15.1 L |

CL: 29.4% V: 10.7% |

Proportional: 23.3% | Bootstrap VPC GOF NPDE |

Monolix |

| 11 | Jaruratanasirikul et al. (2021) | 2-CMT | CL: 13.3 L/h V1: 13.6 L V2: 16.9 L Q: 24.3 L/h |

CL: 51% V1: 66.9% V2: 56% |

Proportional: 18.3% Additive: 0.216 mg/L |

pcVPC NPDE bootstrap | NONMEM |

| 12 | Por et al. (2021) | 2-CMT | CL: 15.31 L/h V1: 32.67 L V2: 41.23 L Q: 11 L/h |

CL: 30.5% V1: 36.1% |

Proportional: 30% | NPDE Bootstrap VPC External validation |

Pumas |

| 13 | Dao et al. (2022) | 1-CMT | CL: 0.21 L/h V: 0.73 L |

CL: 20% | Proportional: 37% Additive: 0.04 mg/L |

Bootstrap pcVPC GOF |

NONMEM |

| 14 | Dinh et al. (2022) | 2-CMT | CL: 4.79 L/h V1: 11.1 h V2: 8.82 L Q: 11.1 L/h |

CL: 38.7% V1: 56.3% V2: 69.4% Q: 110% |

Proportional: 22.1% Additive: 0.445 mg/L |

GOF NPDE VPC Bootstrap |

Monolix |

| 15 | Bai et al. (2024) | 2-CMT | CL: 11.357 L/h Q: 7.645 L/h V1: 16.378 L V2: 10.904 L |

CL: 35.748% V1: 89.853% V2: 8.319% |

Proportional: 30.37% | Bootstrap VPC GOF |

Phoenix NLME |

| 16 | Lafaurie et al. (2023) | 1-CMT | Neutropenia CL: 14.3 L/h V: 20.7 L After neutropenia recovery CL: 10.9 L/h V: 14.5 L |

Neutropenia CL: 19.8% V: 17.4% After neutropenia recovery CL: 21.8% V: 27.8% |

Neutropenia Proportional: 15.9% Additive: 0.42 mg/L After neutropenia recovery Proportional: 36.1% Additive: 0.3 mg/L |

GOF NPDE |

Monolix |

| 17 | Truong et al. (2025) | 2-CMT | CL: 14.6 L/h V1: 28.7 L V2: 21.4 L Q: 2.9 L/h |

CL: 35.9% | Proportional: 38.30% | Bootstrap VPC GOF External validation |

NONMEM |

| 18 | Wang et al. (2024) | 2-CMT | CL: 13.1 L/h V1: 11.7 L V2: 29.3 L Q: 11.9 L/h |

CL: 8.32% | Additive: 0.575 mg/L | GOF pcVPC Bootstrap External validation |

NONMEM |

Results from population pharmacokinetic models of imipenem included in the systematic review.

CMT, compartment; CL, clearance; CLc, clearance of the central compartment; CLd, clearance of the dialysis compartment; CLr, clearance of plasma drug; CLnr, clearance of urine drug; CLbody, endogenous clearance; Q, intercompartmental clearance; Qcp, intercompartment clearance between the central and peripheral compartments; Qcd, intercompartment clearance between the central and dialysis compartments; Q2, intercompartmental clearance (peripheral compartment 1); Q3, intercompartmental clearance (peripheral compartment 2); V1, volume of central compartment; V2, volume of peripheral compartment/peripheral compartment 1; V3, volume of peripheral compartment 2; Vd, volume of distribution; Ke, the elimination rate constant; Kcp, rate constant from the central to peripheral compartment; Kpc, rate constant from the peripheral to central compartment; GOF, goodness‒of-fit plots; VPC, visual predictive check; NPDE, normalized prediction distribution errors; pcVPC, prediction-corrected visual predictive check; SIR, sampling importance resampling procedure; NR, no record.

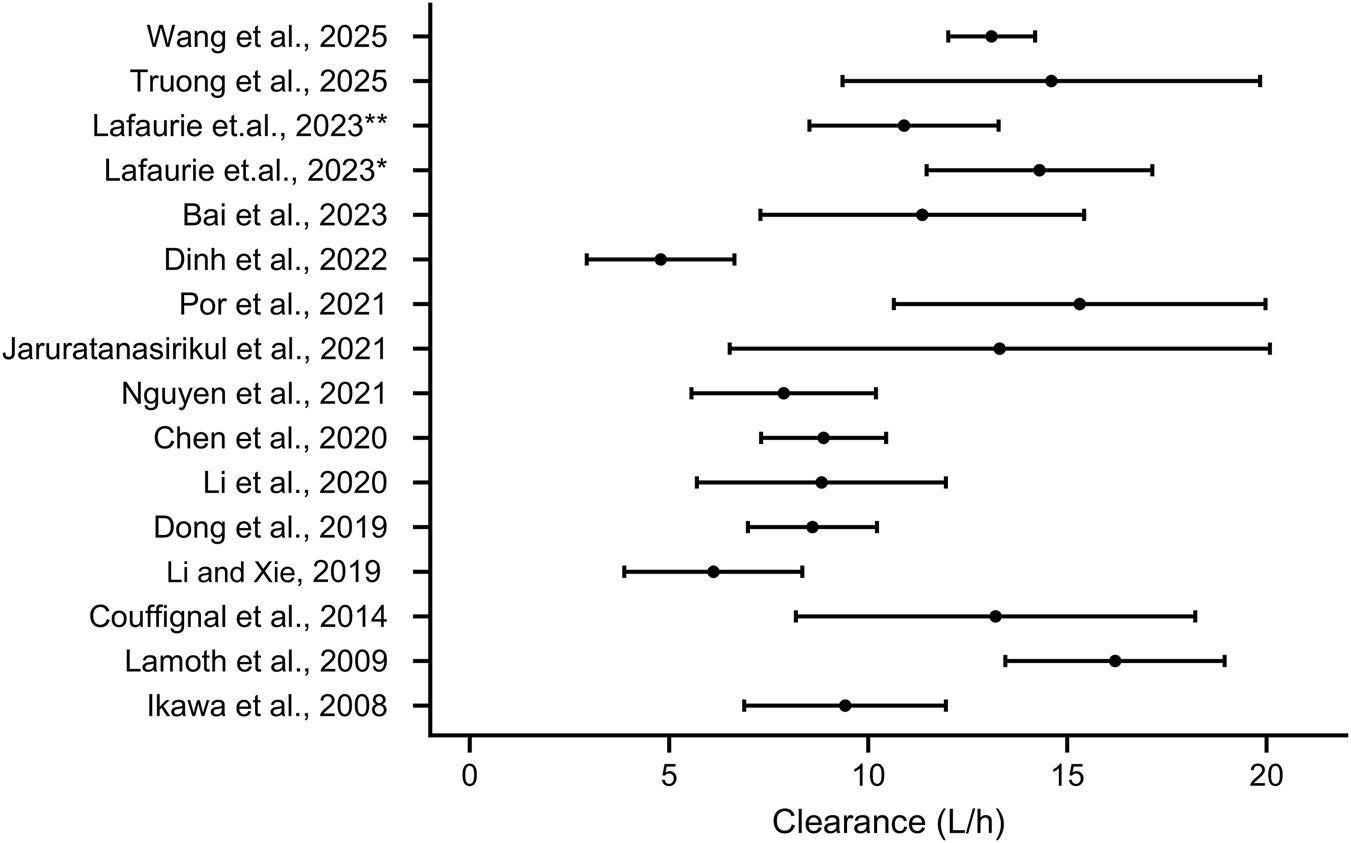

The reviewed studies demonstrated considerable variability in the estimated PK parameters of imipenem. The estimations of imipenem Clearance (CL) are shown in Table 2 ad Figure 2, which range from as low as 0.0783 L/h/kg in neonates (Yoshizawa et al., 2013) to as high as 16.2 L/h in febrile neutropenic patients with hematological malignancies (Lamoth et al., 2009). Regarding distribution volumes, in two-compartment models, the central volume of distribution (V1) varies between 0.203 L/kg in children (Yoshizawa et al., 2013) and 32.67 L in burn patients undergoing CVVH (Por et al., 2021).

FIGURE 2

The estimation of imipenem clearance of adults in various study. * indicates patients with neutropenia, ** indicates patients recovery from neutropenia.

The evaluation of covariates affecting imipenem pharmacokinetics is presented in Table 3. Among the factors assessed, creatinine clearance (CLcr) was the most consistently significant covariate, being identified in 10 out of 11 studies that tested it and serving as the sole predictor in the final models of Nguyen et al. (2021), Bai et al. (2024), Truong et al. (2025), Wang et al. (2024), and Dinh et al. (2022) Study. BW was also frequently retained and was incorporated into 8 out of 14 studies where it was evaluated (Chen et al., 2020b; Couffignal et al., 2014; Dao et al., 2022; Dong et al., 2019; Jaruratanasirikul et al., 2021; Lamoth et al., 2009; Por et al., 2021). In contrast, age was examined in 11 studies but was included in only one final model (Dong et al., 2019), whereas gender was not selected as a significant covariate in any of the 10 studies that considered it. Notable population-specific covariates were also identified. For example, the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) significantly influences imipenem clearance in febrile neutropenic patients with hematological malignancies (de Velde et al., 2020; Jaruratanasirikul et al., 2021; Lamoth et al., 2009). In critically ill patients, imipenem clearance is affected by clinical factors such as burn injury, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), diuresis, the GFR, and the serum ALB concentration. Neonate populations are influenced by BW, gestational age (GA), postnatal age (PNA), and serum creatinine (SCr) (Dao et al., 2022), whereas only CLcr is significant in elderly patients (Wang et al., 2024).

TABLE 3

| Study | Author and year | Covariate analysis method | Covariates screened | Covariates incorporated | Formulation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ikawa et al. (2008) | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| 2 | Lamoth et al. (2009) | NR | BW, eGFRCG | eGFRCG on CL BW on V |

CL = 10.7 + 4.79 × eGFR/100 (mL/min) V = 33.5 × BW/70 |

| 3 | Yoshizawa et al. (2013) | NR | Age, gender, and dose | NR | NR |

| 4 | Couffignal et al. (2014) | Forward inclusion (p < 0.05) | Age, gender, TBW at inclusion and TBW change (between the 4th dose and admission), SAPS II score, the SOFA score, the oedema score, serum ALB, CLcr4h, PEEP, arterial PaO2FiO2 ratio, and the presence of septic shock | CLcr4h on CL TBW and ALB on V1 |

CL = 13.2 × (CLcr/86.4)0.2 V1 = 20.4 × (BW/77)1.3 × (ALB/18)(−1.1) |

| 5 | Li and Xie, 2019 | Forward inclusion (p < 0.05) | Age, gender, BW, patient type (with or without burn), degree of diuresis, urine output, APACHE II score, and %TBSA | Residual diuresis and burn jury on CL | CLtotal = CLCRRT + CLbody CLCRRT = Sd × CRRTintensity × BW/1,000 CLbody = 6.11 × (1 + θBURN) × (1 + θDIUR) × eηCLbody θBURN = 0; non-urned patients θBURN = 0.817; burn patients θDIUR = 0; patients with anuria θDIUR = 0.434; patients with oliguria θDIUR = 0.659; patients with preserved diuresis |

| 6 | Dong et al. (2019) | Forward inclusion ΔOFV > 3.84 (p < 0.05) Backward elimination ΔOFV > 6.635 (p < 0.01) |

Age, BW, CLcrSchwartz | Age, BW, and CLcrSchwartz on CL BW on V1, V2, and Q |

CL = 8.6 × (BW/18)0.75 × (age/4.69)0.265 × (CLcr/214)0.509 V1 = 7.2 × (BW/18) V2 = 6.51 × (BW/18) Q = 0.996 × (BW/18)0.75 |

| 7 | Li et al. (2020) | Forward inclusion ΔOFV > 6.63 (p < 0.01) Backward elimination ΔOFV > 10.83 (p < 0.001) |

Age, gender, weight, sepsis, sepsis shock, ventilatory assistance, course of treatment, AKI, Scr, CLcrCG, blood flow, Qd, replacement fluid flow, APACHE II score, and SOFA score | CLcrCG on CLc Qd on CLd |

CLc = 8.825 × (CLcr/50.896)0.221 × eηCLc CLd = 0.093 × (Qd/500)1.944 × eηCLd |

| 8 | Chen et al., (2020b) | Forward inclusion ΔOFV > 3.84 (p < 0.05) Backward elimination ΔOFV > 7.88 (p < 0.005) |

Age, gender, BW, HT, BMI, SCR, CLcrCG, ALT, AST, ALB, TBIL, HGB, PLT, ECMO, CRRT, type of infection | CLcrCG, BW, and ECMO on CL | With ECMO CL = 8.88 × (CLcr/59.1)0.295 × (BW/65.0)0.306 × e1.16×eηCL Without ECMO CL = 8.88 × (CLcr/59.1)0.295 × (BW/65.0)0.306 × eηCL |

| 9 | de Velde et al. (2020) | Forward inclusion ΔOFV > 3.84 (p < 0.05) Backward elimination ΔOFV > 10.83 (p < 0.001) |

TBW, IBW, LBW, eGFRCG, eGFRMDRD-4, eGFRCKD-EPI, and eGFRJelliffe | eGFRCKD-EPI on Ke | NONMEN Ke = 0.637 × ((eGFRCKD-EPI-abs)/119)0.655 × eη Pmetrics Ke = Kei, med × ((eGFRCKD-EPI-abs)/119)Ke(cov)i, med |

| 10 | Nguyen et al. (2021) | Forward inclusion ΔOFV > 6.635 (p < 0.01) Backward elimination ΔOFV > 10.828 (p < 0.001) |

Age, gender, weight, BMI, CLcrCG, Anthonisen score, CLcrMDRD-4, respiratory distress, and diuretics intake | CLcrCG on CL | CL = 7.88 × (CLcr/75.54)0.532 × eηCL |

| 11 | Jaruratanasirikul et al. (2021) | Forward inclusion ΔOFV > 3.84 (p < 0.05) Backward elimination ΔOFV > 6.64 (p < 0.01) |

Age, gender, actual BW, ideal BW, ABW, BMI, the use of ECMO support, ECMO type, ECMO flow rate, duration of ECMO, APACHE II scores, SOFA scores, CLcrCG, eGFRMDRD-4, eGFRMDRD-6, eGFRCKD-EPI, AKI, mechanical ventilation support, serum ALB, fluid balance, use of inotropes, septic shock, and mean arterial blood pressure | eGFRCKD-EPI on CL ABW on V1 |

CL = 13.3 + 0.112 × (eGFRCKD-EPI -89) V1 = 13.8 − 0.348 × (ABW-60) |

| 12 | Por et al. (2021) | Forward inclusion ΔOFV > 3.84 (p < 0.05) |

Age, total body weight, LBW, CLcrCG, TBSA, total second-degree burn surface area, total third-degree burn surface area, serum ALB, urine output, and use of CVVH | BW and ALB on Vc ALB on Vp With CVVH CLcrCG, WT on CL Without CVVH BW on CL |

Vc = 32.67 × (BW/99.5)0.74 × (ALB/2.7)(−1.17) × eηVc Vp = 41.23 × (ALB/2.7)(−3.68) Without CVVH: CL = 15.31 × (CLcr/145.83)0.46 × (BW/99.5)0.33 × eηCL With CVVH CL = 13.78 × (BW/99.5)0.75 × eηCL + 1.56 |

| 13 | Dao et al. (2022) | Forward inclusion Backward elimination |

Gender, BW, GA, PNA, PMA, SGA, SCr, and concomitant treatments | BW, GA, PNA, SCr on CL BW on V |

CL = 0.21 × (BW/1.16)0.75 × (1 + 0.22 × (PNA-21)/21) × (1 + 1.31 × (GA-26.9)/26.9) × (46.6/SCr)0.2 V = 0.73 × (BW/1.16)0.75 |

| 14 | Dinh et al. (2022) | COSSAC method | Age, gender, actual BW, serum ALB, CLcrCG, UNIT (ICU vs. non-ICU), VASO use and mechanical ventilation | CLcrCG on CL | CL = 4.79 × e(0.00642 × CLcr) |

| 15 | Bai et al. (2024) | Forward inclusion ΔOFV > 3.84 (p < 0.05) Backward elimination ΔOFV > 6.6 (p < 0.01) |

Age, gender, BW, course, Scr, CLcrCG, SOFA score, APACHE II score, sepsis, AKI, septic shock and ventilation | CLcrCG on CL | CL = 11.357 × (CLcr/99.896)0.473 × eη |

| 16 | Lafaurie et al. (2023) | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| 17 | Truong et al. (2025) | Forward inclusion (p < 0.01) Backward elimination (p < 0.001) |

Age, gender, TBW, ABW, IBW, HT, BMI, BSA, UNIT (ICU vs. non-ICU), CLcrCG, eGFRCKD-EPI, and eGFRMDRD-4 | CLcrCG on CL | CL = 14.6 × (CLcrCG/87.6)0.462 |

| 18 | Wang et al. (2024) | Forward inclusion ΔOFV > 3.84 (p < 0.05) Backward elimination ΔOFV > 6.63 (p < 0.01) |

CLcrCG, CRP, WBC, and CRRT | CLcrCG on CL | CL = 13.1 × (CLcr/71)(0.263) × eηCL |

Selection of covariates in the population pharmacokinetic models from the included studies.

CL, clearance; CLc: clearance of the central compartment; CLd, clearance of the dialysis compartment; V1, volume of central compartment; Q, intercompartmental clearance; V2, Volume of Peripheral Compartment/Peripheral Compartment 1; Ke, the elimination rate constant; CLcr, clearance creatinine; Qd, dialysate flow; APACHE, acute physiology and chronic health evaluation score; SOFA, sequential organ failure assessment; BMI, body mass index; BW, body weight; HT, height; ALT, alanine transaminase; AST, aspartate transaminase; ALB, albumin; TBIL, total bilirubin in serum; HGB, hemoglobin; PLT, platelet count; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; CRRT, continuous renal replacement therapy; %TBSA, percentage of burned total body surface area; BSA, body surface area; CRRTintensity, the sum of ultrafiltration rate and dialysis rate; θBURN, factor for the influence of burn injury on CLbody; θDIUR (Oliguria), factor for the influence of oliguria on CLbody; θDIUR (Preserved diuresis), factor for the influence of preserved diuresis on CLbody; CLcrCG, clearance creatinine estimated by Cockcroft and Gault equation; CLcrMDRD-4, clearance creatinine estimated by four-variable Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation; AKI, acute kidney injury; Scr, serum creatinine; TBW, total body weight; IBW, ideal body weight; LBW, lean body weight; eGFRCG, estimated glomerular filtration rate measured by Cockcroft–Gault equation; eGFRMDRD-4, estimated glomerular filtration rate measured by four-variable Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation; eGFRCKD-EPI, estimated glomerular filtration rate measured by the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation; eGFRJelliffe, estimated glomerular filtration rate measured by the Jelliffe’s equation; CKD-EPI-abs, absolute CKD-EPI (i.e., CKD-EPI, multiplied by BSA); ABW, adjusted body weight; GA, gestational age; PNA, postnatal age; SGA, small for gestational age; PMA, postmenstrual age; SAPS II, score, Simplified Acute Physiology Score; PEEP, positive end-expiratory pressure; PaO2FiO2, partial pressure of oxygen/fractional inspired oxygen; CLcr4h, 4 h creatinine clearance; CRP, C-reactive protein; WBC, white blood cell count; VASO, vasopressor; COSSAC, conditional sampling use for stepwise approach based on correlation tests; NR, no record.

4 Discussion

Imipenem is a beta-lactam carbapenem antibiotic characterized by its broad-spectrum antibacterial activity and high stability against beta-lactamases. It is frequently employed as a critical therapeutic agent for severe infections caused by multidrug-resistant pathogens (Armin et al., 2023; Barbier et al., 2023; Kaya et al., 2022). Given its narrow therapeutic window (high doses of imipenem are prone to induce neurotoxicity and nephrotoxicity), pathogens with increased drug resistance and significant interindividual variability in pharmacokinetics, popPK modeling is essential for its optimal use (Chen et al., 2020a; Huo et al., 2020; Martínez Delgado et al., 2022; Slama, 2008). However, although several popPK studies have been published, the sources of PK variability are unclear. Therefore, this review is the first to synthesize recent advances in imipenem popPK and summarize the covariates that significantly affect imipenem exposure.

This systematic review included a total of 18 studies from various countries, five of which were conducted in China. Notably, only three studies enrolled more than 100 patients, whereas the smallest study included only 10 participants. As popPK models rely on group data to estimate parameters, studies with small samples often lack statistical power, making it difficult to accurately identify and quantify the influence of key covariates on imipenem PK. In addition, small sample sizes may significantly constrain the robustness and generalizability of the developed models (Berisha and Liss, 2024). Restricted sample representation can introduce bias, thereby limiting the model’s capacity to reflect the true variability in pharmacokinetic profiles across real-world patient populations, particularly among those with high heterogeneity. Therefore, larger-scale studies are warranted in the future to increase the reliability of individualized dosing strategies for imipenem.

Among the studies included in this review, NONMEM was the most extensively utilized tool for popPK analysis. The two-compartment model is most frequently employed to characterize the PK of imipenem, which closely aligns with its in vivo distribution properties. Following administration, imipenem rapidly distributes into highly perfused tissues and moderately perfused organs, a phase described by the intercompartment clearance (Q) between the central (V1) and peripheral (V2) compartments. This is followed by a comparatively slower elimination phase, governed predominantly by the total CL. The two-compartment model effectively captures the characteristic feature of the drug concentration‒time curve, which exhibits an initial rapid decline (distribution phase) followed by a slower decline (elimination phase), striking an optimal balance between model complexity and biological plausibility.

Although the two-compartment model is most commonly applied, some investigations have explored the use of one- or three-compartment models. The one-compartment model benefits from structural simplicity and fewer parameters, facilitating easier fitting and convergence. However, its major limitation lies in the inability to accurately depict the pronounced distribution phase of imipenem, often resulting in underestimation of early plasma concentrations and potential bias in AUC estimation. In contrast, a three-compartment model could theoretically offer a more refined characterization of the slow distribution phase into deep tissues, such as adipose or poorly perfused regions, potentially enabling a more precise depiction of the in vivo processes (van de Bool et al., 2015). This advantage becomes particularly relevant in studies investigating imipenem PK in nonplasma compartments, for example, peritoneal fluid (Ikawa et al., 2008) and the dialysate of CRRT (Li et al., 2020). By employing a three-compartment model, researchers are better able to quantify drug disposition in these specific biological compartments, which often exhibit kinetics distinct from both central and shallow peripheral compartments. Nevertheless, this model demands extensively rich sampling data for reliable identification of all the parameters. Given the typically sparse nature of clinical data, the three-compartment model often exhibits unstable convergence, high uncertainty in parameter estimates, and a tendency for overfitting (Rambiritch et al., 2016).

Substantial interindividual variability in PK parameters was observed across studies utilizing a two-compartment model (CL: 4.79–15.31 L/h; V1: 7.2–32.67 L; V2: 2.9–41.23 L; Q: 0.996–24.3 L/h). Some studies focused on the same clinical group, but the intra-group variability in PK parameters was also large. For example, the CL in adult critical ill patients varied from 4.79 to 14.6 L/h. This heterogeneity can be attributed primarily to the considerable pathophysiological diversity among the investigated patient populations, which included critically ill subjects with or without ECMO support, elderly patients, children with hematological malignancies, burn patients with or without receiving CVVH, and critically ill patients with suspected ventilator-associated pneumonia. These groups differ markedly in terms of fluid balance, organ function, and hemodynamic status. Notably, the highest CL value (15.31 L/h) in two-compartment model was reported in burn patients with or without CVVH (Por et al., 2021). This elevation is explained by the hyperdynamic circulatory state characteristic of major burns, which involves increased cardiac output and enhanced renal blood flow, thereby accelerating the elimination of imipenem from the kidney (Stanojcic et al., 2018). Furthermore, CVVH contributes to drug elimination by providing an additional clearance pathway (Corona et al., 2022). Similarly, markedly enlarged volumes are frequently documented in critically ill patients, particularly those with sepsis or severe burns (Dickinson and Kollef, 2011; Pruskowski, 2020; Roberts and Lipman, 2009). This phenomenon is associated with capillary leakage, tissue edema, and expansion of the extracellular fluid volume (Roberts and Lipman, 2009). ECMO support may also further increase the apparent distribution volume due to drug adsorption to the circuit (Ahsman et al., 2010; Jelliffe, 2016). It is important to identify and successfully incorporate covariate that can explain the inter-individual variability in the final model.

The majority of studies included in this review predominantly involved critically ill patients. This focus can be attributed to the complex clinical presentations, rapid disease progression, and high mortality rates observed in this population, which consequently make them a priority for clinical intervention and research (Reignier et al., 2025). However, other patient groups also warrant considerable investigation, particularly elderly, infant, and child patients. Elderly patients often present with multiple comorbidities, declining physiological function, and altered PK profiles, predisposing them to adverse outcomes and complicated clinical courses (Medellín-Garibay et al., 2022). Neo et al. reported that carbapenems induced seizures in 2.4% of elderly patients, a prevalence substantially higher than the 0.2%–0.7% range documented in the literature (Neo et al., 2020). In contrast, neonates and children are characterized by ongoing growth and development, resulting in significant differences from adults in terms of organ function, immune status, and drug response. These distinctions lead to unique disease manifestations, therapeutic requirements, and prognostic features. In support of this, a study by Pevzner et al. demonstrated that imipenem/cilastatin was associated with more pronounced nephrotoxicity in neonates, underscoring the need for greater caution in antibiotic selection and dosing in this vulnerable group (Pevzner et al., 2023). Despite the urgent clinical needs in these specific populations, only a limited number of popPK studies targeting these populations were identified in the present review. This indicates a significant research gap, highlighting the necessity for future investigations to prioritize the pharmacokinetics of imipenem in these distinct patient subgroups.

Renal function is known to be the primary determinant of imipenem clearance (Gorham et al., 2022). Consequently, popPK analyses are needed to quantify the impact of renal impairment and other covariates in populations with varying degrees of kidney function. Renal function can be estimated by different equations, commonly CLcr by Cockcroft-Gault equation, eGFR by MDRD and CKD-EPI equations. However, these equations differ in accuracy, especially for special populations like the critically ill, obese and elderly. Among the studies included in this review, CLcr was identified as a statistically significant covariate in ten investigations, eGFR in three, and Scr in one. This distribution reflects the prevalent utilization of CLcr as a routine biomarker for renal function assessment and dosage individualization in clinical practice. When renal function decreases and glomerular filtration capacity becomes impaired, Scr, a waste product of muscle metabolism, cannot be effectively eliminated. Consequently, elevated Scr levels directly indicate diminished renal filtration function. However, Scr is considered a relatively delayed indicator because of the considerable functional reserve of the kidneys; a significant reduction in the GFR must occur before Scr increases noticeably (Romano et al., 2013; Yoo et al., 2019). Furthermore, Scr levels are influenced by factors such as age, sex, muscle mass, and diet (Levey et al., 1999). Therefore, Scr is commonly employed in conjunction with age, sex, and ethnicity for estimating the GFR or CLcr via established equations to better reflect renal functional status in clinical settings (Brown et al., 2013; Inker et al., 2021; Levey et al., 2006; Winter et al., 2012). Recently, Mitton et al. reported that the GFR estimated via the CKD-EPI equation is not related to the plasma level of imipenem in critically ill patients (Mitton et al., 2022). This indicated that the accuracy in estimating renal function of different formulations may introduce bias in covariate effect estimation, and further influence the performance of final model and accuracy of dosing recommendation. It suggests that the plasma concentration of imipenem in critically ill patients cannot be predicted solely on the basis of GFR and that therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) is a safe and effective approach to ensure precision dosing. Additionally, future studies should include more samples and covariates to facilitate the development of a more precise imipenem popPK model.

In the study by Li et al., conventional renal biomarkers such as CLcr, GFR, and Scr were not identified as statistically significant covariates (Li and Xie, 2019). This observation is explained by the fact that their research focused on critically ill patients undergoing CRRT. In this population, drug clearance is substantially influenced by extracorporeal support, thereby limiting the ability of traditional renal function indicators to accurately reflect the actual elimination rate of medications. Alternatively, the model developed by Li et al. (2020) incorporates residual diuresis as a meaningful variable. The clinical relevance of utilizing residual diuresis for dose adjustment has been supported by previous PK investigations. For example, Yu et al. introduced residual diuresis as a significant covariate when developing a popPK model for vancomycin in critically ill patients receiving CRRT (Yu et al., 2023). Similarly, Ulldemolins et al. demonstrated its considerable impact on optimizing meropenem dosing regimens in a comparable patient population (Ulldemolins et al., 2015). Collectively, these findings underscore that residual diuresis serves as an essential and nonnegligible parameter for guiding individualized drug therapy in patients receiving CRRT.

BW was identified as another key covariate characterizing imipenem distribution and elimination and was incorporated into the final model in six of the reviewed studies. For hydrophilic antibacterial agents such as imipenem, PK behavior is closely associated with extracellular fluid volume and renal function, and BW serves as a fundamental metric for estimating body composition and normalizing renal function (Alobaid et al., 2016; Meng et al., 2017). This parameter is particularly relevant in pediatric populations or patients with significant weight fluctuations, where it forms the basis for individualized dosing regimens (Gade et al., 2018; Natale et al., 2017). Consequently, it is frequently included in pharmacokinetic models to increase its predictive accuracy.

In addition to BW and renal function markers, age is commonly considered a demographic covariate, although its significance varies across populations (Sanghavi et al., 2024). This review revealed that age is a meaningful covariate in models involving children (Dong et al., 2019) and neonates (Dao et al., 2022). During early development, age serves as a surrogate for dynamic changes in body size, body composition, and renal function. Keij et al. provided age-specific dose recommendations for pooled popPK studies of intravenous and oral amoxicillin in neonates (Keij et al., 2023). In contrast, the influence of age is often supplanted by more direct physiological or biochemical indicators. Therefore, most adult popPK models do not retain age as a significant covariate.

Notably, most of the included studies relied solely on internal validation, such as bootstrapping, GOF plots, and VPC, whereas only three investigations performed external validation (Por et al., 2021; Truong et al., 2025; Wang et al., 2024). If only internal data were used for validation, the good predictive performance of the model would only be reflected in its own center, making its generalizability to other patient groups uncertain. Therefore, future research should prioritize rigorous external evaluation of these models through multicenter data to verify their predictive ability across diverse clinical settings.

5 Conclusion

In conclusion, of the 18 studies systematically evaluated in this review, popPK models for imipenem have been successfully established across different patient subpopulations. A two-compartment model was predominantly employed to characterize the imipenem popPK model. Notably, markers of renal function were consistently identified as the most significant covariates influencing imipenem exposure, which aligns with imipenem’s primary renal elimination. BW and patient age were also demonstrated to substantially impact PK parameters, necessitating their consideration during therapy. Future research should focus on quantifying the effects of under investigated covariates. Importantly, rigorous external validation was conducted to verify the predictive robustness and general applicability of these models in diverse clinical environments.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Author contributions

PZ: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft. YZ: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Writing – original draft. JZ: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Writing – review and editing. YY: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Writing – review and editing. GL: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Writing – review and editing. XW: Conceptualization, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review and editing. ZY: Conceptualization, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This work is funded by Hangzhou Municipal Health Science and Technology Plan (Project No. A20220991).

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphar.2025.1738055/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Ahsman M. J. Hanekamp M. Wildschut E. D. Tibboel D. Mathot R. A. A. (2010). Population pharmacokinetics of midazolam and its metabolites during venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in neonates. Clin. Pharmacokinet.49 (6), 407–419. 10.2165/11319970-000000000-00000

2

Alikhani M. S. Nazari M. Hatamkhani S. (2025). Enhancing antibiotic therapy through comprehensive pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic principles. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol.15, 1521091. 10.3389/fcimb.2025.1521091

3

Alobaid A. S. Hites M. Lipman J. Taccone F. S. Roberts J. A. (2016). Effect of obesity on the pharmacokinetics of antimicrobials in critically ill patients: a structured review. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents47 (4), 259–268. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2016.01.009

4

Armin S. Fallah F. Karimi A. Karbasiyan F. Alebouyeh M. Rafiei Tabatabaei S. et al (2023). Antibiotic susceptibility patterns for carbapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae. Int. J. Microbiol.2023, 8920977. 10.1155/2023/8920977

5

Bai J. Wen A. Li Z. Li X. Duan M. (2024). Population pharmacokinetics and dosing optimisation of imipenem in critically ill patients. Eur. J. Hosp. Pharm.31 (5), 434–439. 10.1136/ejhpharm-2022-003403

6

Barbier F. Hraiech S. Kernéis S. Veluppillai N. Pajot O. Poissy J. et al (2023). Rationale and evidence for the use of new beta-lactam/beta-lactamase inhibitor combinations and cefiderocol in critically ill patients. Ann. Intensive Care13 (1), 65. 10.1186/s13613-023-01153-6

7

Berisha V. Liss J. M. (2024). Responsible development of clinical speech AI: bridging the gap between clinical research and technology. NPJ Digit. Med.7 (1), 208. 10.1038/s41746-024-01199-1

8

Bricheux A. Lenggenhager L. Hughes S. Karmime A. Lescuyer P. Huttner A. (2018). Therapeutic drug monitoring of imipenem and the incidence of toxicity and failure in hospitalized patients: a retrospective cohort study. Clin. Microbiol. Infect.25 (3), 383.e381–383.e384. 10.1016/j.cmi.2018.11.020

9

Brown D. L. Masselink A. J. Lalla C. D. (2013). Functional range of creatinine clearance for renal drug dosing: a practical solution to the controversy of which weight to use in the cockcroft-gault equation. Ann. Pharmacother.47 (7-8), 1039–1044. 10.1345/aph.1S176

10

Chang C.-Y. Lee Y.-L. Huang Y.-T. Ko W. C. Ho M. W. Hsueh P. R. (2023). In vitro activity of imipenem/relebactam, meropenem/vaborbactam and comparators against Enterobacterales causing urinary tract infection in Taiwan: results from the study for monitoring antimicrobial resistance trends (SMART), 2020. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents61 (6), 106815. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2023.106815

11

Chen I. L. Lee C.-H. Hsiao S.-C. Shih F. Y. (2020a). Interactions between carbapenems and valproic acid among the patients in the intensive care units. J. Crit. Care62, 151–156. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2020.12.005

12

Chen W. Zhang D. Lian W. Wang X. Du W. Zhang Z. et al (2020b). Imipenem population pharmacokinetics: therapeutic drug monitoring data collected in critically ill patients with or without extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.64 (6), e00385-20. 10.1128/AAC.00385-20

13

Chen Y. Han Y. Guo F. Yu Z. (2024). Model-informed precision dosing of imipenem in an Obese adolescent patient with augmented renal clearance and history of schizophrenia. Infect. Drug Resist.17, 761–767. 10.2147/idr.s450294

14

Corona A. Veronese A. Santini S. Cattaneo D. (2022). “CATCH” study: correct antibiotic therapy in continuous hemofiltration in the critically ill in continuous renal replacement therapy: a prospective observational study. Antibiot. (Basel, Switz.)11 (12), 1811. 10.3390/antibiotics11121811

15

Couffignal C. Pajot O. Laouénan C. Burdet C. Foucrier A. Wolff M. et al (2014). Population pharmacokinetics of imipenem in critically ill patients with suspected ventilator-associated pneumonia and evaluation of dosage regimens. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol.78 (5), 1022–1034. 10.1111/bcp.12435

16

Dao K. Fuchs A. André P. Giannoni E. Decosterd L. A. Marchetti O. et al (2022). Dosing strategies of imipenem in neonates based on pharmacometric modelling and simulation. J. Antimicrob. Chemother.77 (2), 457–465. 10.1093/jac/dkab394

17

de Lima K. A. de Souza A. G. Chaves Filho A. J. M. Oliveira J. V. S. de Carvalho M. A. J. Mottin M. et al (2025). Integrative behavior analysis, oxidative stress markers determination and molecular docking to investigate proconvulsant action of betalactamic carbapenems. Neurotoxicology110, 155–167. 10.1016/j.neuro.2025.08.003

18

de Velde F. de Winter B. C. M. Neely M. N. Yamada W. M. Koch B. C. P. Harbarth S. et al (2020). Population pharmacokinetics of imipenem in critically ill patients: a parametric and nonparametric model converge on CKD-EPI estimated glomerular filtration rate as an impactful covariate. Clin. Pharmacokinet.59 (7), 885–898. 10.1007/s40262-020-00859-1

19

Dickinson J. D. Kollef M. H. (2011). Early and adequate antibiotic therapy in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock. Curr. Infect. Dis. Rep.13 (5), 399–405. 10.1007/s11908-011-0206-8

20

Dingle T. C. Pitout J. (2022). The ins and outs of susceptibility testing for new β-Lactam/β-Lactamase inhibitor combinations for gram-negative organisms. J. Clin. Microbiol.60 (7), e0080721. 10.1128/jcm.00807-21

21

Dinh T. D. Nguyen H. N. Le B. H. Nguyen T. T. Nguyen H. L. (2022). Population-based pharmacokinetics and dose optimization of imipenem in Vietnamese critically-ill patients. Infect. Drug Resist.15, 4575–4583. 10.2147/IDR.S373348

22

Dong L. Zhai X.-Y. Yang Y.-L. Wang L. Zhou Y. Shi H. Y. et al (2019). Population pharmacokinetics and dosing optimization of imipenem in children with hematological malignancies. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.63 (6), e00006–e00019. 10.1128/AAC.00006-19

23

Foong K. S. Lee A. Pekez M. Bin W. (2016). Imipenem/cilastatin-induced acute eosinophilic pneumonia. BMJ Case Rep.2016, bcr2016214804. 10.1136/bcr-2016-214804

24

Fratoni A. J. Mah J. W. Nicolau D. P. Kuti J. L. (2022). Imipenem/cilastatin/relebactam pharmacokinetics in critically ill patients with augmented renal clearance. J. Antimicrob. Chemother.77 (11), 2992–2999. 10.1093/jac/dkac261

25

Fratoni A. J. Berry A. V. Liu X. Chen X. Wu Y. Nicolau D. P. et al (2023). Imipenem/funobactam (formerly XNW4107) in vivo pharmacodynamics against serine carbapenemase-producing Gram-negative bacteria: a novel modelling approach for time-dependent killing. J. Antimicrob. Chemother.78 (9), 2343–2353. 10.1093/jac/dkad242

26

Gade C. Christensen H. R. Dalhoff K. P. Holm J. C. Holst H. (2018). Inconsistencies in dosage practice in children with overweight or obesity: a retrospective cohort study. Pharmacol. Res. Perspect.6 (3), e00398. 10.1002/prp2.398

27

Gorham J. Taccone F. S. Hites M. (2022). Drug regimens of novel antibiotics in critically ill patients with varying renal functions: a rapid review. Antibiot. (Basel, Switz.)11 (5), 546. 10.3390/antibiotics11050546

28

Hamao N. Ito I. Konishi S. Tanabe N. Yasutomo Y. Kadowaki S. et al (2025). Incidence of and risk factors for side effects associated with antibiotic treatment for pneumonia. J. Infect. Chemother.31 (9), 102789. 10.1016/j.jiac.2025.102789

29

Heo Y.-A. (2021). Imipenem/cilastatin/relebactam: a review in gram-negative bacterial infections. Drugs81 (3), 377–388. 10.1007/s40265-021-01471-8

30

Huo X. Meng Q. Wang C. Zhu Y. Liu Z. Ma X. et al (2019). Cilastatin protects against imipenem-induced nephrotoxicity via inhibition of renal organic anion transporters (OATs). Acta Pharm. Sin. B9 (5), 986–996. 10.1016/j.apsb.2019.02.005

31

Huo X. Meng Q. Wang C. Wu J. Zhu Y. Sun P. et al (2020). Targeting renal OATs to develop renal protective agent from traditional Chinese medicines: protective effect of apigenin against Imipenem-induced nephrotoxicity. Phytotherapy Res.34 (11), 2998–3010. 10.1002/ptr.6727

32

Ikawa K. Morikawa N. Ikeda K. Ohge H. Sueda T. (2008). Development of breakpoints of carbapenems for intraabdominal infections based on pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in peritoneal fluid. J. Infect. Chemother.14 (4), 330–332. 10.1007/s10156-008-0624-1

33

Inker L. A. Eneanya N. D. Coresh J. Tighiouart H. Wang D. Sang Y. et al (2021). New Creatinine- and cystatin C-Based equations to estimate GFR without race. N. Engl. J. Med.385 (19), 1737–1749. 10.1056/NEJMoa2102953

34

Jaruratanasirikul S. Boonpeng A. Nawakitrangsan M. Samaeng M. (2021). NONMEM population pharmacokinetics and Monte Carlo dosing simulations of imipenem in critically ill patients with life-threatening severe infections during support with or without extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in an intensive care unit. Pharmacotherapy41 (7), 572–597. 10.1002/phar.2597

35

Jelliffe R. (2016). Challenges in individualizing drug dosage for intensive care unit patients: is augmented renal clearance what we really want to know? Some suggested management approaches and clinical software tools. Clin. Pharmacokinet.55 (8), 897–905. 10.1007/s40262-016-0369-4

36

Jia P. Zhou Y. Gao Y. Wang S. Yin J. Lian Y. et al (2025). Real-world pharmacovigilance investigation of imipenem/cilastatin: signal detection using the FDA adverse event reporting system (FAERS) database. Front. Pharmacol.16, 1524159. 10.3389/fphar.2025.1524159

37

Kaya C. Konstantinović J. Kany A. M. Andreas A. Kramer J. S. Brunst S. et al (2022). N-Aryl mercaptopropionamides as broad-spectrum inhibitors of Metallo-β-Lactamases. J. Med. Chem.65 (5), 3913–3922. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c01755

38

Keij F. M. Schouwenburg S. Kornelisse R. F. Preijers T. Mir F. Degraeuwe P. et al (2023). Oral and intravenous amoxicillin dosing recommendations in neonates: a pooled population pharmacokinetic study. Clin. Infect. Dis.77 (11), 1595–1603. 10.1093/cid/ciad432

39

Khan A. B. Abdul-Aziz M. H. Hindle L. Lipman J. Simelela F. Omar S. (2025). Continuous versus intermittent bolus dosing of beta-lactam antibiotics in a South African multi-disciplinary intensive care unit: a randomized controlled trial. J. Infect.90 (5), 106487. 10.1016/j.jinf.2025.106487

40

Lafaurie M. Burdet C. Hammas K. Goldwirt L. Berçot B. Sauvageon H. et al (2023). Population pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of imipenem in neutropenic adult patients. Infect. Dis. Now.53 (1), 104625. 10.1016/j.idnow.2022.09.020

41

Lamoth F. Buclin T. Csajka C. Pascual A. Calandra T. Marchetti O. (2009). Reassessment of recommended imipenem doses in febrile neutropenic patients with hematological malignancies. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.53 (2), 785–787. 10.1128/AAC.00891-08

42

Lechtig-Wasserman S. Liebisch-Rey H. Diaz-Pinilla N. Blanco J. Fuentes-Barreiro Y. V. Bustos R. H. (2021). Carbapenem therapeutic drug monitoring in critically ill adult patients and clinical outcomes: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Antibiot. (Basel, Switz.)10 (2), 177. 10.3390/antibiotics10020177

43

Levey A. S. Bosch J. P. Lewis J. B. Greene T. Rogers N. Roth D. (1999). A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: a new prediction equation. Modification of diet in renal disease study group. Ann. Intern. Med.130 (6), 461–470. 10.7326/0003-4819-130-6-199903160-00002

44

Levey A. S. Coresh J. Greene T. Stevens L. A. Zhang Y. L. Hendriksen S. et al (2006). Using standardized serum creatinine values in the modification of diet in renal disease study equation for estimating glomerular filtration rate. Ann. Intern. Med.145 (4), 247–254. 10.7326/0003-4819-145-4-200608150-00004

45

Li S. Xie F. (2019). Population pharmacokinetics and simulations of imipenem in critically ill patients undergoing continuous renal replacement therapy. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents53 (1), 98–105. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2018.10.006

46

Li Z. Bai J. Wen A. Shen S. Duan M. Li X. (2020). Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic analysis of critically ill patients undergoing continuous renal replacement therapy with imipenem. Clin. Ther.42 (8), 1564–1577.e8. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2020.06.010

47

Marino A. Pipitone G. Venanzi R. E. Cosentino F. Ippolito R. Costa R. et al (2025). Restoring control: real-world success with imipenem-relebactam in critical MDR Infections-A multicenter observational study. Pathog. (Basel, Switz.)14 (7), 685. 10.3390/pathogens14070685

48

Martínez Delgado S. Mínguez Sabater A. Ladrón A. P. Aguilera Sancho-Tello M. V. García Eliz M. Conde I. (2022). Ertapenem neurotoxicity in liver transplantation. Rev. Espanola Enfermedades Dig.114 (4), 240–241. 10.17235/reed.2021.8469/2021

49

Medellín-Garibay S. E. Romano-Aguilar M. Parada A. Suárez D. Romano-Moreno S. Barcia E. et al (2022). Amikacin pharmacokinetics in elderly patients with severe infections. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci.175, 106219. 10.1016/j.ejps.2022.106219

50

Meng L. Mui E. Holubar M. K. Deresinski S. C. (2017). Comprehensive guidance for antibiotic dosing in Obese adults. Pharmacotherapy37 (11), 1415–1431. 10.1002/phar.2023

51

Miller A. D. Ball A. M. Bookstaver P. B. Dornblaser E. K. Bennett C. L. (2011). Epileptogenic potential of carbapenem agents: mechanism of action, seizure rates, and clinical considerations. Pharmacotherapy31 (4), 408–423. 10.1592/phco.31.4.408

52

Mitton B. Paruk F. Gous A. Chausse J. Milne M. Becker P. et al (2022). Evaluating the usefulness of the estimated glomerular filtration rate for determination of imipenem dosage in critically ill patients. South Afr. Med. J.112 (9). 10.7196/SAMJ.2022.v7112i7199.16371

53

Natale S. Bradley J. Nguyen W. H. Tran T. Ny P. La K. et al (2017). Pediatric obesity: pharmacokinetic alterations and effects on antimicrobial dosing. Pharmacotherapy37 (3), 361–378. 10.1002/phar.1899

54

Neo H.-Y. Tan K.-T. Caroline C. Wei-Han Ng D. Pei-Ying Ho E. Lim J. P. et al (2020). Higher rates of carbapenem-related seizures in older hospitalised adults. Intern. Med. J.50 (1), 123–127. 10.1111/imj.14693

55

Nguyen T.-M. Ngo T.-H. Truong A.-Q. Vu D. H. Le D. C. Vu N. B. et al (2021). Population pharmacokinetics and dose optimization of ceftazidime and imipenem in patients with acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Pharmaceutics13 (4), 456. 10.3390/pharmaceutics13040456

56

O’Donnell J. N. Lodise T. P. (2022). New perspectives on antimicrobial agents: imipenem-relebactam. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.66 (7), e0025622. 10.1128/aac.00256-22

57

Pevzner I. B. Brezgunova A. A. Popkov V. A. Sintsov M. Y. Andrianova N. V. Zorova L. D. et al (2023). The effects of antibiotic therapy on neonatal sepsis-associated acute kidney injury. Life Sci.338, 122359. 10.1016/j.lfs.2023.122359

58

Por E. D. Akers K. S. Chung K. K. Livezey J. R. Selig D. J. (2021). Population pharmacokinetic modeling and simulations of imipenem in burn patients with and without continuous venovenous hemofiltration in the military health system. J. Clin. Pharmacol.61 (9), 1182–1194. 10.1002/jcph.1865

59

Pruskowski K. A. (2020). Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of antimicrobial agents in burn patients. Surg. Infect.22 (1), 77–82. 10.1089/sur.2020.375

60

Rambiritch V. Naidoo P. Maharaj B. Pillai G. (2016). Population pharmacokinetic modeling of glibenclamide in poorly controlled South African type 2 diabetic subjects. Clin. Pharmacol.8, 83–92. 10.2147/CPAA.S102676

61

Reignier J. Rice T. W. Arabi Y. M. Casaer M. (2025). Nutritional support in the ICU. BMJ388, e077979. 10.1136/bmj-2023-077979

62

Roberts J. A. Lipman J. (2009). Pharmacokinetic issues for antibiotics in the critically ill patient. Crit. Care Med.37 (3), 840–859. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181961bff

63

Romano T. G. Schmidtbauer I. Silva F. M. d. Q. Pompilio C. E. D'Albuquerque L. A. C. Macedo E. (2013). Role of MELD score and serum creatinine as prognostic tools for the development of acute kidney injury after liver transplantation. PloS One8 (5), e64089. 10.1371/journal.pone.0064089

64

Sanghavi K. Ribbing J. Rogers J. A. Ahmed M. A. Karlsson M. O. Holford N. et al (2024). Covariate modeling in pharmacometrics: general points for consideration. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst. Pharmacol.13 (5), 710–728. 10.1002/psp4.13115

65

Sivanandy P. Manirajan P. Wen Qi O. Teng Khai O. Chun Wei O. Wei Ying N. et al (2024). A systematic review of efficacy and safety of newer drugs approved from 2016 to 2023 for the treatment of complicated urinary tract infections. Ann. Med.56 (1), 2403724. 10.1080/07853890.2024.2403724

66

Slama T. G. (2008). Clinical review: balancing the therapeutic, safety, and economic issues underlying effective antipseudomonal carbapenem use. Crit. Care (London, Engl.)12 (5), 233. 10.1186/cc6994

67

Song J. Pang X. Chen H. Zhang P. Ying M. Xu R. et al (2025). Prevalence of on time administration of carbapenem and its impact on PK/PD target attainment in hospitalized patients: a multicenter retrospective study. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol.15, 1690269. 10.3389/fcimb.2025.1690269

68

Stanojcic M. Abdullahi A. Rehou S. Parousis A. Jeschke M. G. (2018). Pathophysiological response to burn injury in adults. Ann. Surg.267 (3), 576–584. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002097

69

Sutter R. Rüegg S. Tschudin-Sutter S. (2015). Seizures as adverse events of antibiotic drugs: a systematic review. Neurology85 (15), 1332–1341. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002023

70

Tahri A. Lahyani A. Kallel R. Ayadi F. Boudawara T. Sahnoun Z. (2018). Exposure to imipenem/cilastatin causes nephrotoxicity and even urolithiasis in Wistar rats. Toxicology404-405, 59–67. 10.1016/j.tox.2018.05.011

71

Titov I. Wunderink R. G. Roquilly A. Rodríguez Gonzalez D. David-Wang A. Boucher H. W. et al (2021). A randomized, double-blind, multicenter trial comparing efficacy and safety of imipenem/cilastatin/relebactam Versus piperacillin/tazobactam in adults with hospital-acquired or ventilator-associated bacterial pneumonia (RESTORE-IMI 2 study). Clin. Infect. Dis.73 (11), e4539–e4548. 10.1093/cid/ciaa803

72

Truong A. Q. Smeets T. J. L. Terrier J. Li L. Dao X. C. Strojil J. et al (2025). Inadequate imipenem dosing in patients with decreased kidney function: a global clinical pharmacokinetic study. Clin. Microbiol. Infect.31 (9), 1518–1525. 10.1016/j.cmi.2025.05.005

73

Ulldemolins M. Soy D. Llaurado-Serra M. Vaquer S. Castro P. Rodríguez A. H. et al (2015). Meropenem population pharmacokinetics in critically ill patients with septic shock and continuous renal replacement therapy: influence of residual diuresis on dose requirements. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.59 (9), 5520–5528. 10.1128/AAC.00712-15

74

van de Bool C. Rutten E. P. A. Franssen F. M. E. Wouters E. F. M. Schols A. M. W. J. (2015). Antagonistic implications of sarcopenia and abdominal obesity on physical performance in COPD. Eur. Respir. J.46 (2), 336–345. 10.1183/09031936.00197314

75

Wang J. Fang Q. Luo X. Jin L. Zhu H. (2024). Population pharmacokinetics and dosing optimization of imipenem in Chinese elderly patients. Front. Pharmacol.15, 1524272. 10.3389/fphar.2024.1524272

76

Winter M. A. Guhr K. N. Berg G. M. (2012). Impact of various body weights and serum creatinine concentrations on the bias and accuracy of the cockcroft-gault equation. Pharmacotherapy32 (7), 604–612. 10.1002/j.1875-9114.2012.01098.x

77

Yao Y. Zhang L. Chen D. Qin S. Meng M. Guo Q. (2025). Global research on the utilization of population pharmacokinetic model: a bibliometric analysis from 2000 to 2024. Front. Pharmacol.16, 1548023. 10.3389/fphar.2025.1548023

78

Yoo J.-J. Kim S. G. Kim Y. S. Lee B. Lee M. H. Jeong S. W. et al (2019). Estimation of renal function in patients with liver cirrhosis: impact of muscle mass and sex. J. Hepatology70 (5), 847–854. 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.12.030

79

Yoshizawa K. Ikawa K. Ikeda K. Ohge H. Morikawa N. (2013). Population pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic target attainment analysis of imipenem plasma and urine data in neonates and children. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J.32 (11), 1208–1216. 10.1097/INF.0b013e31829b5880

80

Yu Z. Liu J. Yu H. Zhou L. Zhu J. Liang G. et al (2023). Population pharmacokinetics and individualized dosing of vancomycin for critically ill patients receiving continuous renal replacement therapy: the role of residual diuresis. Front. Pharmacol.14, 1298397. 10.3389/fphar.2023.1298397

81

Zhanel G. G. Lawrence C. K. Adam H. Schweizer F. Zelenitsky S. Zhanel M. et al (2018). Imipenem-relebactam and meropenem-vaborbactam: two novel Carbapenem-β-Lactamase inhibitor combinations. Drugs78 (1), 65–98. 10.1007/s40265-017-0851-9

82

Zou L. Meng F. Hu L. Huang Q. Liu M. Yin T. (2019). A novel reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatographic assay for the simultaneous determination of imipenem and meropenem in human plasma and its application in TDM. J. Pharm. Biomed. Analysis169, 142–150. 10.1016/j.jpba.2019.01.039

Summary

Keywords

covariates, creatinine clearance, imipenem, model, population pharmacokinetics

Citation

Zhang P, Zhao Y, Zhu J, Yang Y, Liang G, Wang X and Yu Z (2026) Population pharmacokinetics of imipenem in different populations for individualized dosing: a systematic review. Front. Pharmacol. 16:1738055. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2025.1738055

Received

03 November 2025

Revised

04 December 2025

Accepted

24 December 2025

Published

14 January 2026

Volume

16 - 2025

Edited by

Caisheng Wu, Xiamen University, China

Reviewed by

Huaijun Zhu, Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital, China

Jing Wang, Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Zhang, Zhao, Zhu, Yang, Liang, Wang and Yu.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xia Wang, wangxia1@qdu.edu.cn; Zhenwei Yu, yzw_srrsh@zju.edu.cn

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.