Abstract

The digitalization of human life has impacted many aspects of politics in the last two decades. Intra-party decision-making is one of them. While new political parties appear to be rather native digital organizations, established parties are increasingly beginning to incorporate online tools into their internal processes. However, not much is known about how intra-party selectorates evaluate the digitalization of a crucial decision-making process. This study asks whether party members who participate in candidate selection support online consultations—or not. Using an original large-N dataset on the preferences of party members attending candidate selection assemblies for the German Bundestag, we determine variables that increase or decrease the likelihood to support the introduction of online consultations as part of intra-party democracy. Our results show that attitudes toward digitalization do not depend on a generational or a partisan factor, as might have been expected. Instead, we highlight that digitalization support is first and foremost related to, on the one hand, the seniority in the party, and, on the other, on one's preferences toward inclusion. We relate these findings to the distribution of powers and incentives within the party and discuss both the implications of these results and what they might mean for established parties trying to reform.

Introduction

Candidate selection nests at the core of intra-party democracy (IPD). The selection of the candidates for the next election is a central moment in any political party's life, and the possibility to take part in this decision is an important exclusive feature of party membership (Scarrow, 2014, p. 181–185; Hazan and Rahat, 2010). In the age of digitalization (Mergel et al., 2019), and of an arguable crisis of the political parties (Coller et al., 2018), the introduction of online consultations, be it in addition or replacement of more traditional candidate selection processes, might be a way for established parties to modernize their functioning and adapt to the changing expectations of voters regarding their inner democracy (Barberà et al., 2021b). This paper interrogates the amount of support for the introduction of such tools amongst the selectorate of German parties, and wonders under which circumstances they would be willing to adopt such consultations.

Indeed, existing studies suggest that political parties and their MPs somewhat adapted to the general trend of digitalization (Zittel, 2015; Lioy et al., 2019; Blasio and Viviani, 2020; Dommett et al., 2020; Gerbaudo, 2021), which has sometimes spurred changes in the party organization, interactions between different party levels and actors as well as the distribution of power. Regarding candidate selection, the question of digitalization as a potentially non-hierarchic process of selection has an impact on classical party features such as inclusion/exclusion or centralization/decentralization of the party decision-making (Barnea and Rahat, 2007; Kenig, 2009; Kernell, 2015; André et al., 2017; Cordero and Coller, 2018).

However, the question of digital candidate selection in the light of intra-party democracy in general (Cross and Katz, 2013; see also Bille, 2001; Höhne, 2013; Kernell, 2015; Theocharis and de Moor, 2021) is still new and needs more attention in academic research. When it is studied, it usually investigates how parties deal with these tools once they are in place (e.g., Dommett and Rye, 2018), and rarely to understand the sociological context in which this kind of organizational questions might arise in the first place, especially in long-established parties. Therefore, this study asks which factors explain support or rejection of digitalization of candidate selection processes in long-established German political parties. Our research takes this matter as a case study with a party comparative approach to investigate the broader topics of intra-party democracy, party organization, and how the institutionalization of new processes may occur.

We answer our interrogation by drawing on an original and representative dataset about German candidate selection in the run-up for the 2017 Bundestag election (#BuKa2017). Germany is an exciting case since its candidate selection processes are well-known for their long-standing stability and lack of innovation (Zeuner, 1970; Roberts, 1988; Schüttemeyer, 2002; Schüttemeyer and Sturm, 2005; Höhne, 2017; Schüttemeyer and Pyschny, 2020). We use a hierarchical binomial logistic regression to test our hypotheses and illuminate the rationale for supporting or opposing digitalization in the established German parties in the 2017 Bundestag. In the first section, we will start by exploring the literature on digital intra-party democracy, to develop our main hypotheses. We will then present both the specific case of German candidate selection processes, the data we analyzed, and the details of the methods that were used, before moving on to the results of our multivariate analysis. We then measure the factors that promote or inhibit support for the introduction of online consultations and show that this preference depends both on holding objective positions of power, and on personal preferences toward party inclusion. We conclude by discussing the most critical aspects of our results and their limitations, highlighting the potential for further studies and our contribution to the field of candidate selection and IPD research in general.

Inclusion, Modernity and Party Incentives: The Tricky Question of Digitalizing Intra-Party Democracy

Digitalization has sometimes been framed as a potential way out of a supposed crisis, affecting representative democracies in general and political parties in particular, as their number of members declined and their legitimacy was increasingly questioned (Margolis and Resnick, 2000, p. 2; Margolis et al., 2003; Dalton, 2004; Armingeon and Guthman, 2014; Kölln, 2014). In this context, it was presented as a potentially more deliberative and inclusive technology (Berg and Hofmann, 2021), from a perspective that assumes the solution would be found through more direct democracy, as opposed to more representative democracy. Whether or not digitalization can indeed lead to more satisfactory intra-party democracy, whether this would then lead to halt parties' decline, and what kind of obstacles parties might encounter in including more online tools in their decision-making arsenal, are reasonably new questions. They have, however, been attracting attention from the academic literature in recent years, specifically through a multiplication of case-studies or small-scale comparisons, which highlighted the fact that not all parties and party systems were equally eager nor equipped to handle digitalization (Thuermer et al., 2016; Bennett et al., 2017; Lisi, 2019) and showed how dependent on party context the general results were. Most studies on parties digitalization were also analyzing new and populist parties (Mikola, 2017; Lanzone and Rombi, 2018; Caiani et al., 2021), which have been arguably keener in embracing this trend than established parties and have tended to equate this push toward more direct and inclusive democracy as the only path toward more democracy in general. The conclusion of this research is somewhat ambiguous. Some evidence was indeed found of digitalization rekindling interest for political parties. Digitalization has for example been shown to lead to more involvement of party members and supporters, with greater member satisfaction (Lioy et al., 2019; Deseriis, 2020), some authors are going as far as to say it might hold the keys to “party renewal” (Chadwick and Stromer-Galley, 2016), or that it answers to “the need to radically update the organizational forms of politics and adapt them to the digital era” (Gerbaudo, 2019, p. 190). However, not all the evidence supports this positive evaluation (Kernell, 2015; Trittin-Ulbrich et al., 2021), as critics argue that the hyper-centralization of party processes in some countries did not disappear with digitalization (Blasio and Viviani, 2020; Cepernich and Fubini, 2020), or that very low participation rates will lead to parties' attempts at deepening democratization to feel like “empty vessels” (Vittori, 2020).

The assessment of the costs and benefits for parties to include more online tools in their functioning is of course an important question, but one that sometimes tends to overshadow another question: whether parties are indeed likely to introduce such tools. Political parties are not only rational organizations, trying to maximize their voter share to reach power: they are also self-referential human creations, social circles based on interpersonal relations and, at best, a shared ideology. All these features rely on the involvement of their members—and therefore on members' satisfaction—to reach organizational goals (Harmel and Janda, 1994; Young and Cross, 2002; Neumann, 2013; Spier, 2019). Reforming intra-party democracy has also been proven to have ambiguous effects, with re-legitimization of the “improved” party structure not necessarily leading to better outcomes, be it in terms of legitimacy or membership counts (Ignazi, 2018). In this context, regarding the likelihood of such tools being implemented, it might matter more what the more involved members of the party think about digitalization than what digitalization can indeed be expected to achieve for them. That is the question we focus on here.

In recent years, the tendency has rather been for parties to offer more incentives to their members (Faucher, 2015; Gomez and Ramiro, 2019; Achury et al., 2020). Amongst them, the ability to select the candidates for the upcoming election might be one of the party functions members tend to consider with high interest, as it has been repeatedly found to be part of the most important objects of participation (Scarrow, 2014; Spier and Klein, 2015; Gomez et al., 2019). Nonetheless, the opinions of party members on the digitalization of candidate selection processes—and therefore how likely they are to support structural changes in this direction—have yet to be properly understood (Fitzpatrick, 2021). In a different context in a 2017 paper, Caroline Close, Camille Kelbel and Emilie van Haute assessed the support of “alternative candidate selection procedures” amongst voters in general. They found that their preferences were mixed, and depended on several variables, one of them being political involvement and activity, therefore opening the question of specific preferences of party members, that could very well differ from the general population (see also Shomer et al., 2016).

Our research, therefore, attempts to contribute to the question of the willingness of members of established parties to engage with digitalization, to generate deeper knowledge about the party members' views of intra-party democracy in general. Theoretically, we do so by relying on a set of literature-based hypotheses.

Hypotheses

The question of member involvement in political parties has been described by Panebianco (1988) as a tricky balance to strike for parties. According to him, the institutionalization and survival of political parties rely indeed on finding the most effective system of incentives, which must both be inclusive enough of grassroots members that outsiders will want to join the party, and selective enough that they reward the greater involvement of functionaries and party leadership (see also Randall and Svåsand, 2002). The introduction of online consultations in candidate selection processes—because it would be expected to have consequences on the final decision-making—is a change that would modify the ways party incentives are currently distributed in German established parties, and, therefore, raises questions about which type of members would be most interested in this potential new balance of incentives.

The first set of hypotheses about this matter relates to the relative novelty of the possibility for parties to offer online consultations. In this context, we could assume that this kind of incentives would be more interesting for party members whose social characteristics predispose them more toward the use of the internet. In this regard, previous research has shown that individual factors such as age, gender and education are correlated with how people engage and participate through digital tools, leading to several “digital divides” (Feezell et al., 2016; Hargittai and Jennrich, 2016; Schradie, 2018). A first hint in favor of this hypothesis could be found when comparing the composition of established parties to the composition of new populist parties and party-movements. If the latter tend to rely a lot more on digital tools, they also tend to have younger members and more female members than traditional parties (Lanzone and Rombi, 2018; Lavezzolo and Ramiro, 2018; Gomez and Ramiro, 2019), which hints at age and gender—and more generally social characteristics—being a possible factor. This hypothesis is also supported by the results of Close, Kelbel and van Haute for the general population of voters (Close et al., 2017), and is coherent with a more general discourse about the aspirations to more inclusive or “renewed” forms of democracy, that younger, more educated voters might share. Therefore, our first set of hypotheses can be broken down as such:

H1a: Younger party members are more likely to support online consultations in candidate selection than older party members.

H1b: Higher educated party members are more likely to support online consultations than party members with lower levels of education.

H1c: Female party members are more likely to support online consultations than male party members.

Candidate selection processes that are held in-person can also be assumed to favor more involved party members, or at least those who have enough time to go to candidate selection events. In this context, online consultations might result in the inclusion of usually more excluded party members, and therefore strip the more involved ones of an incentive that typically rewards their strong participation. As a result, more involved party members might be more reluctant to the introduction of such procedures. Literature also tends to show that familiarity and attachment with a specific organizational culture mostly occur among members who have been active in the party for many years, and have developed a kind of attachment over that time to the party's procedures and organizational reality (Walter-Rogg, 2013; Gauja, 2017; Schindler and Höhne, 2020). Therefore, our second set of hypotheses includes the following:

H2a: Party members who entered the party more recently are more likely to support online consultations than members who have been involved for a longer time.

H2b: Party members who dedicate less of their time to the party are more likely to support online consultations than members who are more regularly active in the party.

Similar reasoning pushes us toward our third set of hypotheses. Indeed, the will to protect the intra-party status-quo to guarantee access to important selective incentives might also be shared by another group of party members: those who hold one or several elected positions. Because the current procedures have led to them being selected as candidates or party board members in the past, and because they usually take part in the selection as it is, they might be more inclined to leave selection practices untouched. Mandate holders might also be concerned about their re-selection and re-election if the procedures were to change. This might be especially true for higher-ranked politicians, for whom political mandates constitute a professional activity from which they derive most, or all, of their income. They might also consider party members less informed about party affairs than they are, making the consultation of grassroots members more of a burden than a resource of interesting feedback (Spier and Klein, 2015, 99).

H3a: Grassroots party members are more likely to support online consultations than members who hold electoral mandates or party board positions.

H3b: The higher the mandate or board position party members hold, the more opposed to online consultations they are.

However, not all preferences regarding party organization must come from a self-serving mindset. They might also be related to what is considered by the respondent to be good in itself, either because of political ethics or of strategy. One of the main results from Close et al. (2017) about voters' preferences toward candidate selection procedures was a strong correlation with voters' conception of democracy. They noted that voters who distrusted representative democracy were more likely to support “alternative” candidate selection procedures, specifically those that involve tools of direct democracy. Regarding digitalization within parties, the process is generally considered jointly with calls for increased deliberation and participation (Gerl et al., 2018) and is often linked to higher levels of inclusion—mostly discussed in line with populism (Font et al., 2021). The topic of inclusion is also tied to the implementation of direct vs. representative intra-party democracy (García Lupato and Meloni, 2021). Party affiliation might also be considered, both because political-ideological opinions might play a role in the matter, and because party culture might also influence respondents. Because center-right parties are traditionally considered to be elite-born and less participation-oriented than leftist parties, this could be taken as an assumption that members of the Christian democratic parties CDU and CSU might be less interested in digitalization than members of more progressive parties. Beyond party affiliation, the perceived ideological discrepancy between one's party and their political preferences might also be a factor. Indeed, party members who feel further away from the line defended by their party might feel this way because they do not feel represented by the chosen candidates. Therefore, a change in the selection process might be an opportunity for them to see the party line shift toward one they would feel is a better choice. Therefore, our final set of hypotheses focuses on the attitudinal level and states as follows:

H4a: Party members who prefer processes based on the inclusion of members and direct democracy are more likely to support online consultations than members who prefer delegation-based processes.

H4b: Party members who are unsatisfied with the current candidate selection processes in their party are more likely to support online consultations than members who are satisfied with the current nomination system.

H4c: Members of left or progressive parties are more likely to support online consultations than members of the right and center-right ones.

H4d: Members who declared to have less ideological proximities with their party are more likely to support the introduction of online consultations than members who feel the party's line is completely coherent with their preferences.

Empirical Data and Methods

Candidate Selection in Germany

Germany is an interesting case when analyzing candidate selection for several reasons, the first of which being its unique mix of different procedures (Detterbeck, 2016; Deiss-Helbig, 2017; Höhne, 2017; Schindler, 2021; Berz and Jankowski, 2022). Indeed, members of the German Bundestag can be elected by one of two ways: either directly, by winning a relative majority of votes in single-member districts, or by being placed high enough on a closed party list to win a seat in the proportional vote that occurs at the level of the 16 federal states. For candidates, this system typically leads to double candidacies—both as direct and list candidates—to boost the chance to get a seat in the national parliament. For party organizations though, this system means they must organize candidate selections at both district and state-level, with different priorities and amounts of participants for each level.

The way that parties organize this selection is legally regulated in Germany and can only occur in one of two ways: Candidates can be nominated either at a general meeting, which can be attended by all interested party members who wish to participate in the process, or at a delegate conference, which is attended only by party members who have been elected by their lower-level colleagues. At the state level, parties almost exclusively hold delegate conferences for candidate nomination. At the district level, however, the Bundestag parties have made different choices between these two options (Detterbeck, 2016; Höhne, 2017): the Social Democratic Party (SPD) holds mainly—but not exclusively—delegate conferences, while the Christian Democratic Union holds a mix of both, with half of the district candidates being chosen through general meetings. The picture is similar for the Left Party. The Liberals (FDP) and the Green Party routinely have general meetings whereas the Bavarian Christian Social Union (CSU) summons only delegate conferences. This mix of selection processes presents a situation in which inclusion levels and logics of selection vary within the parties and between the parties for the same general election. These recruitment patterns make the German case particularly compelling for candidate selection analysis in general.

German political parties have been described to be stable organizations, enjoying large memberships, with reasonably weak elite-grassroots oppositions regarding party organization (Lübker, 2002). Nevertheless, as in several other representative democracies, established parties in Germany have been in turmoil in recent years, as socioeconomic and sociocultural cleavages appear to be shifting while the traditional party affiliations of certain social groups are changing (Hutter et al., 2019; Borucki and Fitzpatrick, 2021; Casal Bértoa and Rama, 2021). The 2017 election saw the populist radical right party—the Alternative for Germany (AfD), founded in 2013 and relying on a style of IPD very much based on direct participation (Heinze and Weisskircher, 2021; Höhne, 2021; Kamenova, 2021)—entering the national Parliament for the first time. In more recent years, the Social Democrats, the Christian Democrats, the Left, and the Green Party all engaged in discussions about potential reforms of their internal decision processes. Even so, the SPD installed online topical forums as an additional arena for preparing internal decision-making (Michels and Borucki, 2021).

Data, Methods, and Measurements

The analyzed dataset called #BuKa2017 is based on a large-scale study conducted by the German research institute IParl in the run-up to the 2017 election. Respondents were interviewed using interviewer-assisted standardized paper questionnaires at the respective nomination assemblies. The survey was designed to measure party members' attitudes toward the candidate selection process in which they were attending, be it either general meetings or delegate conferences at the state or district level. The polling institute “Policy Matters” (Berlin) conducted the field research between the autumn of 2016 and summer 2017. The 137 conferences studied were randomly selected (Table 1). The response rates were reasonably high with an overall rate of 54.7 percent, resulting in 9,275 completed questionnaires (Table 2).

Table 1

| Number of investigated | … at district | … at state | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| conferences: | level | level | |

| … left party | 15 | 8 | 23 |

| … green party | 15 | 8 | 23 |

| … social democrats | 15 | 8 | 23 |

| … liberals | 15 | 8 | 23 |

| … CDU | 12 | 7 | 22 |

| … CSU | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| … AfD | 22 | 8 | 22 |

| Total | 89 | 48 | 137 |

Number of investigated nomination conferences by party and election level.

Parties have been arranged from left to right, according to respondents' opinions measured on a left-right-scale.

Table 2

| Number of respondents… | … at district level | … at state level | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| … at a general meeting | 2,187 | 1,120 | 3,307 |

| … at a delegate conference | 1,794 | 4,174 | 5,968 |

| Total | 3,981 | 5,294 | 9,275 |

Number of respondents by type of conference and election level.

For this analysis, respondents who did not reply to the question about online consultations were excluded. Since the questions we ask in this paper refer to the long-established parties in the German party system, we decided to exclude data on the populist radical right party AfD, which is not considered one of these parties (Berbuir et al., 2015; Serrano et al., 2019; Zons and Halstenbach, 2019; Atzpodien, 2020). The resulting dataset includes 7,588 respondents, who represent very different types of party members, from newly arrived grassroots members to well-established professional politicians with a very long party involvement (Bukow and Jun, 2020; Schindler and Höhne, 2020). It should be noted, however, that the party members who participated in the candidate selection process—whether in general meetings or, even more so, in delegate conferences—are not representative of all party members. More committed and more interested party members usually tend to go to those events or are chosen to be delegates (Hazan and Rahat, 2010; Baras i Gómez et al., 2012; Close et al., 2017), which means the dataset is likely to overrepresent members who hold a mandate or a board position and underrepresent members who are more distanced or spend less time for in-person party activities. In our sample, 25% of the respondents reported to spend 8 h or less per month on party work, while only 3% of respondents stated to spend no time at all on party work (Table 3).

Table 3

| Min. | 1st Qu. | Median | Mean | 3rd Qu. | Max. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.00 | 8.00 | 15.00 | 24.34 | 30.00 | 420.00 |

Description of sample of respondents according to party activity per month (in hours).

While the dataset is not generally representative of party membership, it is a more accurate portrait of the party members that parties can rely on every day to do the “donkey work” (Webb et al., 2017), both internally and externally. It is also an approximation of the actual selectorate, which is what we are interested in here. Because they participate in party events, these members are also the ones who are more likely to make their opinions known, and therefore contribute to shape the party's organization and its priorities. It is, therefore, a subset of party members whose preferences might be better reflected in parties' choices of candidate selection processes.

Dependent Variable

The dependent variable ordinally scales party members' preferences regarding online consultation for candidate selection. The variable was covered in the questionnaire with the statement: “Online consultations of the party members should additionally be conducted when candidates are nominated,”1 asking if online consultations should be added to the current processes being used. The word used in the original German questionnaire (“Befragungen”) is stronger than mere polling for opinions, but not necessarily understood as binding either. Respondents could express their opinion by marking either (1) “fully agree,” (2) “tend to agree,” (3) “disagree somewhat,” or (4) “totally disagree.” The scale did not have a neutral point, but skipping the question was possible −7.2% of the respondents chose to do so. The variable was dichotomously recoded, to include either support or opposition to the introduction of digital consultations. This decision was taken because it makes the results less sensitive to socially determined response bias, such as moderacy and extreme response biases (Hui and Triandis, 1985; Greenleaf, 1992), while keeping the focus on what matters here, which is an expression of either support or opposition. Table 4 presents the responses to the dependent variable before the treatment of the data (Table 4).

Table 4

| Completely | Somewhat | Somewhat | Completely | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| agree | agree | disagree | disagree | NAs | Total |

| 13.3% | 28.2% | 31.3% | 21.0% | 7.2% | 100% |

| (N = 1,002) | (N = 2,306) | (N = 2,560) | (N = 1,720) | (N = 591) | (N = 8,179) |

Distribution of opinions about online consultations (non-dichotomized).

We deliberately chose not to propose more specific online consultation tools in the question because we wanted to measure gut-feeling support for the general idea of digitalizing intra-party democracy, not the pros and cons of one specific tool or another. It was therefore important that the respondents would be free to give the question the meaning that would come most naturally to them, as it was the condition to reveal what their priorities and anticipations are on the matter, without any suggestions from the questionnaire. Our fourth set of hypotheses was therefore designed to exploit this lack of specificity by capturing the various ideas that respondents might have associated with this question—for example, asking about the inclusiveness of selection processes and their transparency, or their relationship to political leanings.

Independent Variables

The independent variables are all taken from the questionnaire, which was designed to measure descriptive information of the surveyed population—such as age, gender, level of education or numbers of years spent as a party member—as well as personal preferences regarding the modes of candidates' selection, and indicators of political involvement.

The measure for political professionalization, relevant for H3, is the only variable that was significantly recoded from the original questionnaire. The respondents were asked to declare whether they had a position on the party board, and, if so, at which level (local, district, regional, state, national, or European level). They were also asked if they were an elected official, and if so at which level. Respondents also had the opportunity to declare whether they were a rank-and-file party member. Those three pieces of information were then combined into a dummy variable, that differentiates between grassroots members—who have declared themselves accordingly, and do not hold a position as a board member or elected official at any level—and two categories of members with specific positions. We have chosen to distinguish between those whose highest position is at the local, district, or regional level and those who hold at least one position at the state level or higher. This choice was made because it seems to us that it reproduces the well-known dichotomy suggested by Max Weber, between politicians who live “for” politics as a kind of hobby or honorary engagement, and politicians who can live “from” politics, as a professional activity (Weber, 1919). Indeed, the wages for those positions can be argued to only become high enough to really live off from at the state level, even if exceptions might exist. We therefore end up with an indicator that discriminates between grassroots party members, non-professional politicians, with only local positions, and professional politicians. Finally, the perceived ideological distance from the party line was calculated by asking respondents to rate their position as well as that of their respective party on an eleven-point scale, ranging from left to right. The difference between the two scores was then used to distinguish between respondents who say they fully agree with their party (no difference), slightly diverge from their party (1 or 2 point difference), or significantly diverge from their party (3 point difference or more).

Models

To identify predictors for support or opposition to online consultations, we decided to rely on hierarchical binomial logistic regression. The results presented here add a new set of variables for each of the hypotheses explained above, from the more individual ones to the more macro-level arguments. The binomial analysis was calculated for the models (including null models, not displayed on the figure) with the glm-function from the lme4 package in R.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

The first result that needs to be highlighted here is that most respondents do not support the introduction of online consultations for candidate selection. As a whole, 56% of our respondents reported that they were disagreeing slightly or completely with this statement in the questionnaire, showing that, for most of the selectorate at least, digitalization of party processes is not necessarily seen as progress, nor as a generally good thing.

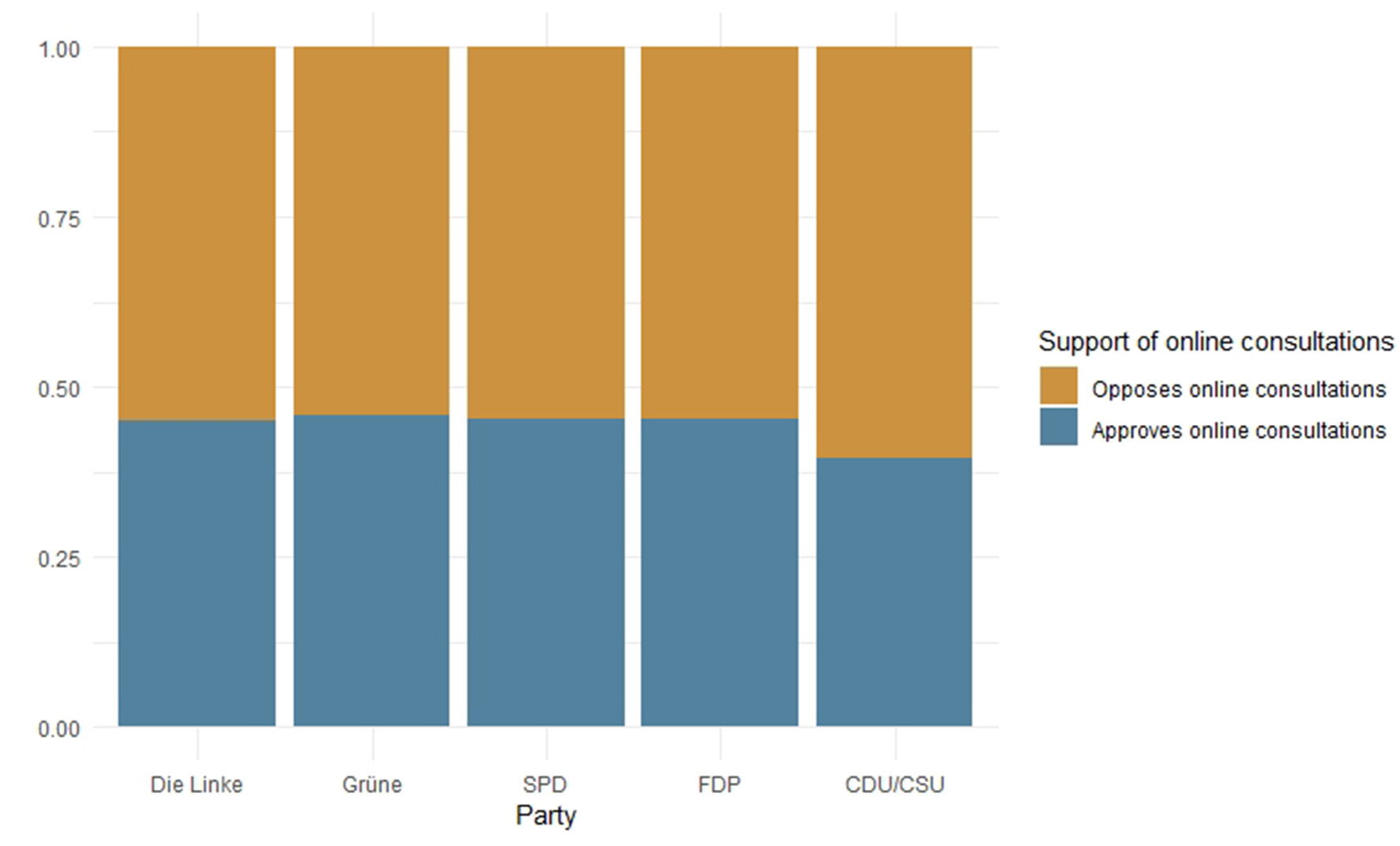

This result is all the more remarkable because it stays true in almost all constellations. In all parties surveyed, there is at least 50% rejection of digitalization (Figure 1), with the CDU and CSU expressing a slightly higher degree of opposition.2 If we reduce the dataset to grassroots members only and exclude any respondent with a mandate or a board position at any level, 52% oppose the introduction of online consultations in the candidate selection process.

Figure 1

Support of online consultations depending on party membership (in %).

Given this very stable, albeit short, majority against online consultations, any variables that would reduce support for this prospect would only lower the likelihood of a pre-existing minority opinion. Which of these variables causes lower support for digitalization nevertheless reveals a lot about the party structure, as the multivariate analysis will show.

Multivariate Analysis

The regression models that estimate the support for online consultations as a dependent variable are depicted in the following table (Table 5). As explained above, each model adds new variables that enable us to test one of the four sets of hypotheses that were stated at the beginning of the paper.

Table 5

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds-ratio | Confidence | Odds-ratio | Confidence | Odds-ratio | Confidence | Odds-ratio | Confidence | |

| interval | interval | interval | interval | |||||

| (Intercept) | 1.50** | 1.13–2.01 | 1.44* | 1.05–1.98 | 1.45 | 0.97–2.17 | 1.93* | 1.18–3.17 |

| Age | 0.99*** | 0.99–1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00–1.01 | 1.00 | 1.00–1.01 | 1.00 | 0.99–1.01 |

| Gender [women] | 1.08 | 0.98–1.20 | 1.03 | 0.92–1.15 | 0.98 | 0.86–1.13 | 0.94 | 0.81–1.09 |

| Education (pseudo metric of degree levels) | 0.94** | 0.89–0.98 | 0.94* | 0.89–0.99 | 0.93* | 0.87–0.99 | 0.92* | 0.85–0.98 |

| Time spent in party (in years) | 0.98*** | 0.98–0.99 | 0.99*** | 0.98–0.99 | 0.99*** | 0.98–0.99 | ||

| Activity [11–30 h/month] | 0.89 | 0.79–1.00 | 1.01 | 0.86–1.19 | 0.99 | 0.83–1.17 | ||

| Activity [31+ h/month] | 0.86* | 0.75–0.99 | 0.97 | 0.80–1.16 | 0.92 | 0.75–1.12 | ||

| Position [non-professional politician] | 0.90 | 0.77–1.05 | 1.07 | 0.90–1.27 | ||||

| Position [professional politician] | 0.44*** | 0.31–0.63 | 0.52** | 0.35–0.77 | ||||

| Preferred mode [delegate conf.] | 0.56*** | 0.48–0.64 | ||||||

| Satisfaction with participation [satisfied] | 0.71*** | 0.59–0.87 | ||||||

| Party [Die Linke] | 1.30* | 1.00–1.68 | ||||||

| Party [Grüne] | 1.24* | 1.02–1.50 | ||||||

| Party [SPD] | 1.32** | 1.09–1.60 | ||||||

| Party [FDP] | 1.24 | 0.98–1.58 | ||||||

| Distance to party line [moderate −1–2 points] | 1.07 | 0.92–1.25 | ||||||

| Distance to party line [important −3 points and more] | 1.21 | 0.96–1.51 | ||||||

| Number of obs. | 6,597 | 6,109 | 3,393 | 3,583 | ||||

| AIC | 9006.1 | 8282.2 | 5386.9 | 4715.5 | ||||

| BIC | 9033.2 | 8329.2 | 5443.5 | 4820.6 | ||||

| Log. Lik. | −4499.028 | −4134.075 | −2684.448 | −2340.746 | ||||

| McFadden pseudo-R2 | 0.13 | 0.20 | 0.48 | 0.55 | ||||

Regression models—dependent variable: support to online consultations.

Values given are odds-ratio, with confidence intervals. Numbers above 1 show a higher likelihood to support online consultations compared to the base category, number between 0 and 1 show a lower likelihood to support online consultations compared to the base category. 1 shows the absence of effect.

All assumptions for performing binomial logistic regression were checked. Models display no issues of multicollinearity, nor skewed residuals. Linearity of the logit for continuous variables was established. Hosmer-Lemeshow tests of goodness of fit were not significant.

Significance:

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.001.

Our first hypothesis predicted that a specific type of party members—younger, more educated, and female—would be more likely to support online consultations. As the variables tested by the H1 model show, this is not really the case. Indeed, gender is never a significant variable, and the estimated effect associated with it is very small. If age appears to be significant in the first model, it is no longer so when controlling for other variables, and it is associated with a null or near-zero effect associated with the distributions of respondents' ages that are against or for online consultations (see Table 6) —if the supporters of online consultations seem like they might be slightly younger, it is only extremely marginal. Whether 17 or 90 years old, party members almost seem to be just as likely to support digitalization.3 However, education does seem to have some influence, albeit a small one, but contrary to our original hypothesis: With each additional degree, the likelihood of supporting the introduction of online consultations decreases.

Table 6

| Min. | 1st Qu. | Median | Mean | 3dr Qu. | Max. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Opposes online consultations | 17 | 40 | 53 | 51,4 | 63 | 95 |

| Supports online consultations | 17 | 37 | 51 | 49,6 | 61 | 91 |

Distribution of the age of the respondents (in years) depending on their support or opposition to online consultations in candidate selection.

These results are in direct contradiction with our expectations. They also contradict the narratives often repeated and believed in the media about the necessity for parties to adapt to a new generation of voters with more demanding and direct ideas about democracy and politics by digitizing their IPD. It does not necessarily mean that said ideas are false (Lardeux and Tiberj, 2021), but it does tend to indicate that the party members of 2017, including the “younger” ones, are probably not that different from their elders, at least in terms of their preferences of intra-party democracy. They might, though, differ from younger voters that are not party members—or not part of the selectorate, and that parties might be interested in attracting (Borucki et al., 2021). It might also be an indication that the use of the internet, which has been available for public use for over 20 years, is no longer the generational marker it used to be (Initiative D21 e.V., 2021), especially in populations that tend to be highly educated, as is the case for party members (Katz and Mair, 1992; Spier and Klein, 2015). The fact that the education variable is contrary to our expectations—a higher degree does not increase support for online consultations, on the contrary—could also support the idea that digitalization is no longer as exclusive as it used to be. It does confirm other findings on the topic that show non-usage of online tools in party members is very rarely linked to technical issues (Gerl et al., 2018). It is also coherent with several of the effects developed below, that we could summarize as follows: the higher the social status, the lower the chances to be in favor of online consultations.

The variables tested in Model 2, related to H2, tend to support this statement. Indeed, we can see that the number of hours a month one is involved in the party cannot definitely be stated as influential. If there is a tendency toward more involved members opposing digital consultations slightly more, the effect is not clear enough to be considered significant. There is, however, an effect of the number of years spent in the party—of seniority –, as members involved for longer tend to oppose digital consultations more. Although the effect seems to be quite small, it adds up over the years and suggests that the question of introducing digitalization in intra-party democracy may be more a question of party familiarity and party control than a generational issue: the longer people have been involved in the party, the lower are the chances they would want to see their familiar environment change, and the more likely it is that they like the way things are currently being done.

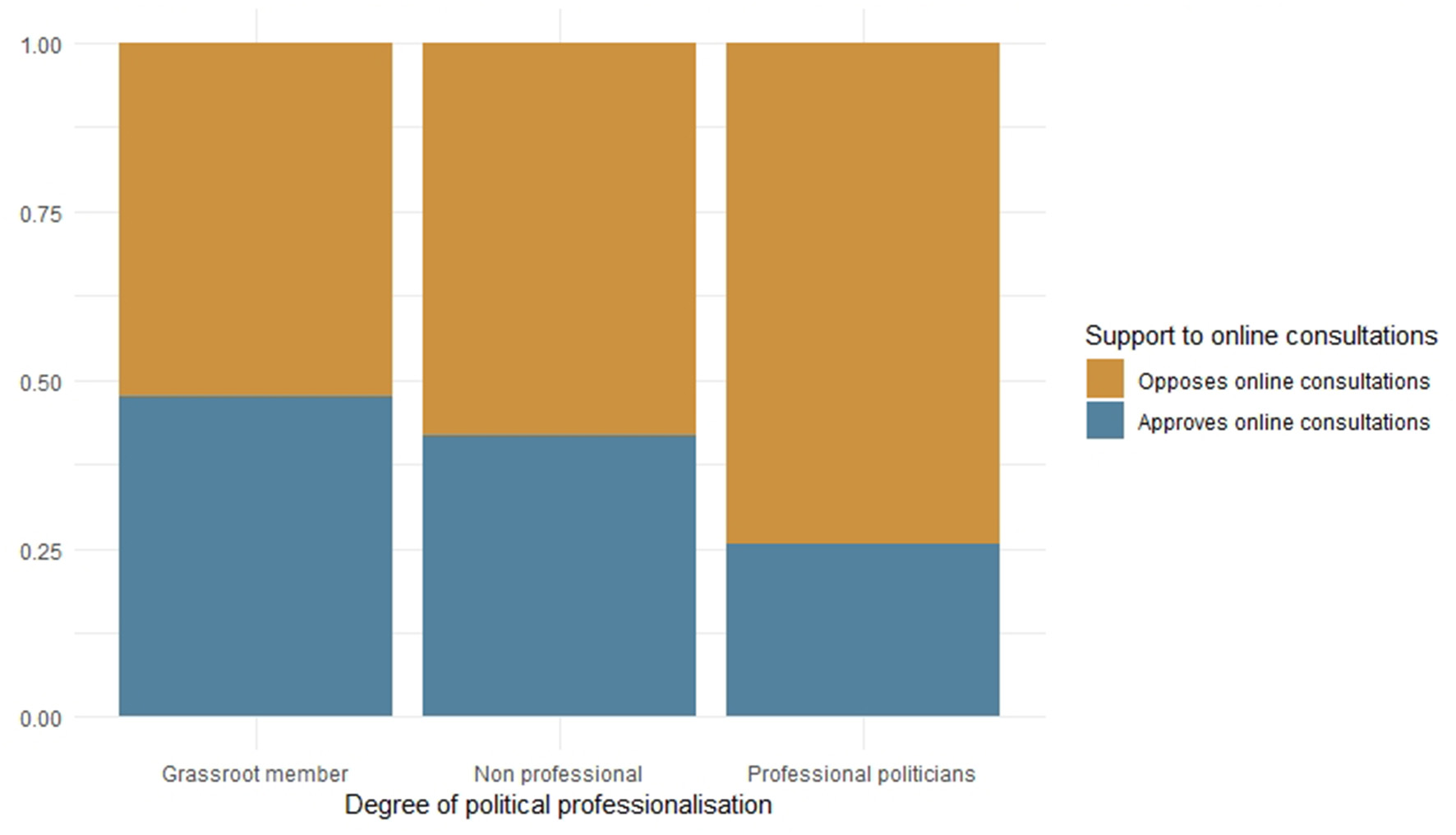

The interpretation in terms of power relations is supported by the introduction of the next variable. Namely, in Model H3 the question of political careers is added. We can see here that, in the same way as was demonstrated for H2, the higher the position, be it as a party board member or as a mandate-holder, the lower the chances are to support the introduction of online consultations. If the effect is not significant for the category of respondents we labeled “non-professional politicians,” who hold positions at the local level, it is very significant, and has a strong effect for “professional politicians,” with a national or European career background. This effect is also very evident in the data: If 52% of grassroots members opposed online consultations, this was the case for 74% of professional politicians (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Support of online consultations, depending on degree of political professionalization (in %).

The pattern that emerges in our first three models is, therefore, one that tends to confirm that the digitalization of candidate selection—and the increasing inclusion that can be expected to happen—poses a threat to members who currently hold a greater share of the power over party decisions, whether through mandates, board responsibilities, or simple seniority.

This hierarchical aversion toward digitalization cannot be understood outside of ideological preferences, and especially preferences for the inclusion of selection processes. Indeed, Model H4 shows that a predilection for more inclusive candidate selection processes tends to go together with the support of introducing online consultations. A leaning toward delegate conferences instead of general meetings strongly decreases the odds of supporting online consultations, and on the other hand, dissatisfaction with the participation opportunities in the party correlates with higher support for online consultations, following the results found in the general voter population (Close et al., 2017).

This interpretation of the results is supported when we analyze the other survey items that measure satisfaction with the current selection process in a party (Table 7).4 Indeed, believing that the current process is not democratic, not transparent or is too predictable has a significant effect on the respondents' support or opposition to online consultations. Therefore, digitalization appears to be supported by party members who perceive the party might lack intra-party democracy. This result highlights very plainly that, no matter what digitalization does to inclusion and democracy, the two concepts appear to be mentally related, at least for people in our sample. In contrast, feeling that the process is complicated, or inefficient, has a much smaller and statistically non-significant effect on the preferences on the issue of digitalization. This shows that global dissatisfaction with the process cannot be the reason for the increased support for digital tools at candidate selection: it is specifically dissatisfaction regarding the inclusion level that is relevant here.

Table 7

| H4 + democratic | H4 + transparent | H4 + predictable | H4 + efficient | H4 + complicated | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | Odds ratios | Odds ratios | Odds ratios | Odds ratios | Odds ratios |

| (Intercept) | 2.07 | 1.38 | 1.25 | 1.35 | 1.37 |

| Age | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Gender [women] | 0.98 | 0.99 | 0.97 | 1.01 | 0.99 |

| Education (pseudo metric of degree levels) | 0.93* | 0.93* | 0.93* | 0.93* | 0.93* |

| Time spent in party (in years) | 0.98*** | 0.98*** | 0.98*** | 0.98*** | 0.98*** |

| Activity [11–30 h/month] | 1.03 | 1.01 | 1.02 | 1.02 | 1.02 |

| Activity [31+ h/month] | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.98 | 0.97 |

| Position [non-professional politician] | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.90 | 0.91 | 0.91 |

| Position [professional politician] | 0.46*** | 0.45*** | 0.45*** | 0.45*** | 0.46*** |

| Is process democratic [not democratic] | 1.50*** | ||||

| Is process transparent [not transparent] | 1.28** | ||||

| Is process predicable [predictable] | 1.21** | ||||

| Is process efficient [not efficient] | 1.11 | ||||

| Is process complicated [complicated] | 1.12 | ||||

| Observations | 3,885 | 3,830 | 3,824 | 3,816 | 3,795 |

| AIC | 5232.881 | 5154.778 | 5149.795 | 5150.516 | 5115.349 |

| BIC | 5295.530 | 5217.284 | 5212.285 | 5212.986 | 5177.763 |

| McFadden pseudo-R2 | 0.50 | 0.51 | 0.51 | 0.51 | 0.51 |

Different version of the H4 models, including different set of variables to test for preferences.

Values given are odds-ratio. Numbers above 1 show a higher likelihood to support online consultations compared to the base category, number between 0 and 1 show a lower likelihood to support online consultations compared to the base category. 1 shows the absence of effect.

All assumptions for performing binomial logistic regression were checked. Models display no issues of multicollinearity, nor skewed residuals. Linearity of the logit for continuous variables was established. Hosmer-Lemeshow tests of goodness of fit were not significant.

Significance:

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.001.

The other variables we included in Model H4 appear to carry less weight in determining attitudes toward online consultations. Indeed, we can find that, as expected, it seems like all parties are more likely than the Christian Democratic Union to favor the introduction of digital tools in candidate selection, therefore, giving some credit to our theory of progressive orientation being a factor, but the measured effects appear to be quite small. We also find some evidence that greater disagreement with one's party's ideology might also lead to support for online consultations. In the latter case, statistical significance is not reached, which does not allow us to draw firm conclusions from the model.

Discussion and Summary

In this paper, we assessed the support for the introduction of online tools—namely online consultations—in candidate selection processes among the selectorate of the established German parties. Based on data collected by questionnaires passed at candidate selection conferences in the advent of the 2017 federal election, our analysis highlighted the distribution of such preferences, depending on sociological characteristics, objective individual positions in the party, and ideological as well as evaluative preferences. Our first main result is that support or opposition to the parties' digitalization is not—perhaps no longer—dependent on a generational difference. The stakes of the question do not lie in a supposed technological gap but in the way power and influence are distributed inside the party and how the selectorate conceives inclusion.

Although a narrow majority of respondents opposes digitalization no matter their party affiliation, we were nonetheless able to find a correlation between a higher likelihood of opposing online consultations and position in the party, be it in terms of number of years in the party, mandates and board positions held. Due to the sampling procedure of our respondents, our dataset tends to represent party members who are more involved than most others are. Considering this, the fact that most of our respondents oppose the idea of digital consultations tends to go in the same direction: the closer to the decision-making centers party members are, the less likely they are to support the introduction of online consultations. What we see here can be understood as a hierarchical reluctance to digitalize intra-party democracy at candidate selection and, more broadly, as a reluctance to make the nomination processes more inclusive at the expense of one's own influence or concerns.

This phenomenon is plausibly explained by a fear of loss of power and control if online consultations were to be introduced since such instruments might change power relations in parties and stimulate participatory demands (Dommett, 2018). Such a loss of power, at least to some extent, is indeed likely when substituting traditional communication channels by dialogical instruments like instant messaging or polls, as it would lower the costs of participation for party members—specifically the costs regarding time (Caletal et al., 2013; Spier and Klein, 2015). The likely consequence would probably be a change in the profile of the selectorate (Vittori, 2020). Such tools might also create an artificial sense of proximity between a charismatic party leader and the grassroots members. This relationship would then be easy to use to weaken the legitimacy of the other layers of the intra-party hierarchy and eventually bypass them, exposing them to becoming irrelevant.

The profiles of the more reluctant subset of our respondents, therefore, hints at this intra-party power-sharing explanation, but our results also highlight that ideological preferences matter too. Indeed, and similarly to Close et al. (2017), our results show that the party members who are dissatisfied with the inclusion level of the process tend to favor the introduction of online consultations significantly more than those who are satisfied, which hints at the idea that preferences toward inclusion and toward digitalization tend to go hand in hand (Raniolo and Tarditi, 2019). It highlights the fact that for respondents—whether they oppose or support the introduction of online consultations—the general expectation is that these consultations would have some kind of effect on the number of party members actually involved in the decision-making: that, in the end, consultation would be participation. It also makes sense that the dissatisfaction might be greater for the party members who never benefitted from the incentives the party has to offer—in the form of mandates or board positions—than for those who have, therefore establishing a relationship between ideological preferences and objective social positions. Koo (2021) as well as Caletal et al. (2013) found that one's position in the party is related to their confidence and general satisfaction with the party processes. Nevertheless, not everyone dissatisfied with the inclusion level of members supports the introduction of online consultations: a certain level of mistrust toward digitalization might still be associated even in this group, which needs to be further researched to properly explain.

Most of the research on the digitalization of parties so far has focused on native digital parties and, therefore, often left-wing populist parties (Caiani et al., 2021; Gerbaudo, 2021). Our results show that this specific focus probably leads to overestimating digitalization's potential for parties. Our paper, therefore, advocates more interest for long-established parties in research about digitalization, to assess to which extent what seems to be true for newly founded populist movement parties can also apply to traditional ones.

The variables used here as an explanation do not offer an exhaustive analysis of the potential reasons for reluctance against of intra-party digitalization. Other explicative factors for our results can also be put forward. We could for example also hypothesize that for some members, the opposition might stem from the reluctance to have party culture be questioned and re-discussed. German established parties specifically rely on “consensus-oriented IPD” (Höhne, 2021), which members might have internalized as the only legitimate mode of internal decision-making, while digital tools could possibly be associated with a more plebiscitary kind of decision-making. It could also be argued that the reluctance for online consultations is related to the fact that members themselves do not wish to participate more (Schindler and Höhne, 2020). They could be happy to delegate their will if the process is efficient, supporting the idea of Hibbing and Theiss-Morse on stealth democracy (Hibbing and Theiss-Morse, 2002; Webb, 2013; Lavezzolo and Ramiro, 2018). Stealth democracy suggests an alternative to representative or direct democracy by stating that citizens are happy with democracies being run under the surface. When applied to party organizational research, this optimization implies the assumption that a share of low-active but happy members in parties would support the leadership's decisions for preserving a status-quo they are satisfied with. The fact that our data point toward a theory of power-holding and does not allow to test for the possibility of stealth democracy being prevalent in party members, does not mean both explanations cannot coexist and be found in further studies.

This paper also did not address what the implications would be for intra-party democracy to have or not have this type of consultations introduced, and notably did not specify how digital consultations would specifically be carried out, which leaves wide open the question of different preferences being potentially expressed should more information be specified. Finally, another limitation of this study comes from the fact that the respondents were members of the selectorate and not party members in general. If it enables us to highlight the strong relationship between power-holding and preferences about digitalization, it also excludes from our sample the members who are the most likely to feel sidelined and dissatisfied by candidate selection processes, as well as the completely inactive members. Again, further research, with slightly different methodologies—surveys of the entire membership, but also interviews or focus-groups of party members—might help to size more robustly our revealed discrepancy.

Looking at our findings and conclusions, the road ahead into the digital for intra-party democracy in established parties depends on the organizational design they want to create for the future (Barberà et al., 2021a). If they were to include more digitalization in their internal processes, they coincidently might re-integrate grassroots members who are dissatisfied with traditional decision-making procedures. The literature argues that more inclusive processes might end up more representative of the actual electorate of the parties (Achury et al., 2020), and might thus benefit parties in the long run. At the same time, the top and mid-level elites in the parties in charge of implementing those changes might also be less likely to support them, and most of the currently involved party members might not enjoy the change of pace. The ability to select the candidates is part of the important incentives parties can offer their members, and most of our respondents do not necessarily seem keen to have their voice diluted in this process. Pleasing one crowd without displeasing the other might still be a hard balance to strike for political parties.

It should be noted that these results, derived from data collected in 2016 and 2017, would most likely already slightly differ today, as the external shock created by the COVID-19 pandemic has forced parties across the world to adapt very quickly and partly involuntarily to an environment in which in-person meetings were compromised (for a German example: Settles et al., 2021). In the run-up for the 2021 election in Germany, digital nomination assemblies were made necessary (Borucki et al., 2020; Michl, 2021), and have been tested, used, and improved, which is likely to have affected the preferences of party members and party elites alike—though in which direction remains to be investigated. In the aftermaths of this 2021 election, German parties still appear to be looking for the right balance between inclusion and exclusion, as the CDU held an online and postal—non-binding—party primary in prevision of its leadership selection. The question of the different ways, digital or not, to rekindle partisan enthusiasm without the most involved members feeling betrayed does not seem like it will be settled any time soon. Research on digitalization points out that it is not enough to simply transfer structures to the digital, but that digitalization must be understood as a fundamental and comprehensive transformation. This insight also applies to the intra-party digitalization of candidate selection.

Funding

This article was based on the #BuKa2017 study of the Institute for Parliamentary Research (IParl), which was funded by the Foundation for Science and Democracy (SWuD). The work of IB's research group was funded by the Digital Society research program, funded by the Ministry of Culture and Science of the German State of North Rhine-Westphalia (Grant Number 005-1709-0003). Any other financial benefits or interests are not applicable.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2022.815513/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1.^All survey questions used to construct the statistical models in this paper are available, in the original German and translated into English, in the Appendix (Table A).

2.^Because the CSU only exists at the regional level, our nationwide dataset has a lot less respondents for the CSU than for any other party. For all statistical computation, they have therefore been considered jointly with their sister party, the CDU.

3.^The age variable is continuous, and party members tend to skew older than the general population. It could therefore be hypothesized that the result is here a consequence of this under-representation of younger party members in the survey. To test for this, the age variable was also recoded as a categorical generation variable and put in the model: the results were similarly not significant.

4.^These variables were not included in the regression models in Table 5 to keep the models both synthetic and methodologically sound.

References

1

AchuryS.ScarrowS. E.Kosiara-PedersenK.Van HauteE. (2020). The consequences of membership incentives: do greater political benefits attract different kinds of members?Party Politics26, 56–68. 10.1177/1354068818754603

2

AndréA.DepauwS.ShugartM. S.ChytilekR. (2017). Party nomination strategies in flexible-list systems. Party Politics23, 589–600. 10.1177/1354068815610974

3

ArmingeonK.GuthmanK. (2014). Democracy in crisis? The declining support for national democracy in European countries, 2007-2011. Euro. J. Polit. Res.53, 423–442. 10.1111/1475-6765.12046

4

AtzpodienD. S. (2020). Party competition in migration debates: the influence of the AfD on party positions in German State Parliaments. German Polit.10.1080/09644008.2020.1860211. [Epub ahead of print].

5

Baras i GómezM.Rodríguez-TeruelJ.Barberà i AresteÒ.BarrioA. (2012). Intra-Party Democracy and middle-level elites in Spain. Working papers Institut de Ciències Pol ítiques i Socials. Bd. 304 (Barcelona: Institut de Ciències Politiques i Socials).

6

BarberàO.SandriG.CorreaP.Rodríguez-TeruelJ. (2021b). Political parties transition into the digital era, in Digital Parties: The Challenges of Online Organisation and Participatio, eds BarberàO.SandriG.CorreaP.Rodríguez-TeruelJ. (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 1–22.

7

BarberàO.SandriG.CorreaP.Rodríguez-TeruelJ. (eds.). (2021a). Digital Parties: The Challenges of Online Organisation and Participation. Studies in Digital Politics and Governance. Cham: Springer.

8

BarneaS.RahatG. (2007). Reforming candidate selection methods a three-level approach. Party Polit.13, 375–394. 10.1177/1354068807075942

9

BennettW.SegerbergA.KnüpferC. (2017). The democratic interface: technology, political organization, and diverging patterns of electoral representation. Information Commun. Soc.21, 1655–1680. 10.1080/1369118X.2017.1348533

10

BerbuirN.LewandowskyM.SiriJ. (2015). The AfD and its sympathisers: finally a right-wing populist movement in Germany?Ger. Polit.24, 154–178. 10.1080/09644008.2014.982546

11

BergS.HofmannJ. (2021). Digital democracy. Internet Policy Rev.10, 1–23. 10.14763/2021.4.1612

12

BerzJ.JankowskiM. (2022). Local preferences in candidate selection. Evidence from a conjoint experiment among party leaders in Germany. Party Politics. 10.1177/2F13540688211041770. [Epub ahead of print].

13

BilleL. (2001). Democratizing a democratic procedure: myth or reality?: candidate selection in western european parties, 1960-1990. Party Polit.7, 363–380. 10.1177/1354068801007003006

14

BlasioE. D.VivianiL. (2020). Platform party between digital activism and hyper-leadership: the reshaping of the public sphere. Media Commun.8, 16–27. 10.17645/mac.v8i4.3230

15

BoruckiI.FitzpatrickJ. (2021). Tactical web use in bumpy times - a comparison of conservative parties' digital presence, in Digital Parties: The Challenges of Online Organisation and Participation, eds BarberàO.SandriP.CorreaG.Rodríguez-TeruelJ. (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 245–267.

16

BoruckiI.MaschL.JakobsS. (2021). Grundsätzlich bereit, aber doch nicht dabei - Eine Analyse der Mitarbeitsbereitschaft in Parteien anhand des Civic Voluntarism Models. Zeitschrift Politikwissenschaft31, 25–56. 10.1007/s41358-021-00251-w

17

BoruckiI.MichelsD.ZieglerS. (2020). No Need for a Coffee Break? - Party Work in the Digital Age. Regierungsforschung.de, 9. Avaialble online at: https://www.regierungsforschung.de/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Borucki_etal_CoffeeBreaks.pdf

18

BukowS.JunU. (2020). Continuity and Change of Party Democracies in Europe, 1st Edn. Wiesbaden: Springer. p. 366. 10.1007/978-3-658-28988-1

19

CaianiM.PadoanE.MarinoB. (2021). Candidate selection, personalization and different logics of centralization in new Southern European populism: the cases of podemos and the M5S. Government Opposition. 10.1017/gov.2021.9. [Epub ahead of print].

20

CaletalD.CochliaridoulE.MilzA. (2013). Innerparteiliche partizipation, in Parteien, Parteieliten und Mitglieder in einer Großstadt, eds Walter-RoggM.GabrielO. (Wiesbaden: Springer), 49–68.

21

Casal BértoaF.RamaJ. (2021). Polarization: what do we know and what can we do about it?Front. Polit. Sci.3, 687695. 10.3389/fpos.2021.687695

22

CepernichC.FubiniA. (2020). Italian parties and the digital challenge: between limits and opportunities. Contemporary Italian Polit.12, 1–22. 10.1080/23248823.2020.1863650

23

ChadwickA.Stromer-GalleyJ. (2016). Digital media, power, and democracy in parties and election campaigns: party decline or party renewal?Int. J. Press Polit.21, 283–293. 10.1177/1940161216646731

24

CloseC.KelbelC.van HauteE. (2017). What citizens want in terms of intra-party democracy: popular attitudes towards alternative candidate selection procedures. Polit. Stud.65, 646–664. 10.1177/0032321716679424

25

CollerX.CoderoG.Jaime-CastilloA. M. (eds.) (2018). The Selection of Politicians in Times of Crisis.Abingdon, VA; Oxfordshire; New York, NY: Routledge.

26

CorderoG.CollerX. (eds.) (2018). Democratizing Candidate Selection: New Methods, Old Receipts?Springer International Publishing, 99-121. 10.1007/978-3-319-76550-1

27

CrossW. P.KatzR.S. (eds.). (2013). The Challenges of Intra-Party Democracy.Oxford: Oxford University Press.

28

DaltonR. (2004). Democratic Challenges, Democratic Choices: The Erosion of Political Support in Advanced Industrial Democracies.Oxford: Oxford University Press.

29

Deiss-HelbigE. (2017). Les modes de sélection des candidats affectent-ils la représentation parlementaire des minorités d'origine étrangère ? Une analyse des élections législatives allemandes de 2013. Politique Sociétés36, 63–90. 10.7202/1040413ar

30

DeseriisM. (2020). Digital movement parties: a comparative analysis of the technopolitical cultures and the participation platforms of the Movimento 5 Stelle and the Piratenpartei. Information Commun. Soc.23, 1770–1786. 10.1080/1369118X.2019.1631375

31

DetterbeckK. (2016). Candidate selection in Germany: local and regional party elites still in control?Am. Behav. Scientist60, 837–852. 10.1177/0002764216632822

32

DommettK. (2018). Roadblocks to interactive digital adoption? Elite perspectives of party practices in the United Kingdom. Party Polit.26:135406881876119. 10.1177/2F1354068818761196

33

DommettK.FitzpatrickJ.MoscaL.GerbaudoP. (2020). Are digital parties the future of party organization? A symposium on the digital party: political organisation and online democracy by Paolo Gerbaudo. Italian Polit. Sci. Rev.51, 1–14. 10.1017/ipo.2020.13

34

DommettK.RyeD. (2018). Taking up the baton? New campaigning organisations and the enactment of representative functions. Politics38, 411–427. 10.1177/0263395717725934

35

FaucherF. (2015). New forms of political participation. Changing demands or changing opportunities to participate in political parties?Compar. Euro. Polit.13, 405–429. 10.1057/cep.2013.31

36

FeezellJ.ConroyM.GuerreroM. (2016). Internet use and political participation: engaging citizenship norms through online activities. J. Information Technol. Polit.13, 95–107. 10.1080/19331681.2016.1166994

37

FitzpatrickJ. (2021). The five-pillar model of parties' migration into the digital, in Digital Parties: The Challenges of Online Organisation and Participation, eds BarberàO.SandriG.CorreaP.Rodríguez-TeruelJ. (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 23–42.

38

FontN.GrazianoP.TsakatikaM. (2021). Varieties of inclusionary populism? SYRIZA, podemos and the five star movement. Government Opposition56, 163–183. 10.1017/gov.2019.17

39

García LupatoF.MeloniM. (2021). Digital intra-party democracy: an exploratory analysis of podemos and the labour party. Parliamentary Affairs gsab015. 10.1093/pa/gsab015

40

GaujaA. (2017). Party Reform. Comparative Politics.Oxford: Oxford University Press.

41

GerbaudoP. (2019). The Digital Party: Political Organisation and Online Democracy. London: Pluto Press.

42

GerbaudoP. (2021). Are digital parties more democratic than traditional parties? Evaluating Podemos and Movimento 5 Stelle's online decision-making platforms. Party Polit.27, 730–742. 10.1177/1354068819884878

43

GerlK.MarschallS.WilkerN. (2018). Does the internet encourage political participation? Use of an online platform by members of a German Political Party. Policy Internet10, 87–118. 10.1002/poi3.149

44

GomezR.RamiroL. (2019). The limits of organizational innovation and multi-speed membership: podemos and its new forms of party membership. Party Polit.25, 534–546. 10.1177/1354068817742844

45

GomezR.RamiroL.MoralesL.AjaJ. (2019). Joining the party: incentives and motivations of members and registered sympathizers in contemporary multi-speed membership parties. Party Polit.27, 779–790. 10.1177/1354068819891047

46

GreenleafE. A. (1992). Measuring extreme response style. Public Opin. Q.56, 328–351. 10.1086/269326

47

HargittaiE.JennrichK. (2016). The online participation divide, in The Communication Crisis in America, and How to Fix it, eds LloydM.FriedlandL. (New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan US), 199–213.

48

HarmelR.JandaK. (1994). An integrated theory of party goals and party change. J. Theor. Polit.6, 259–287. 10.1177/0951692894006003001

49

HazanR. Y.RahatG. (2010). Democracy Within Parties: Candidate Selection Methods and Their Political Consequences.Comparative Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

50

HeinzeA. S.WeisskircherM. (2021). No strong leaders needed? AfD party organisation between collective leadership, internal democracy, and “movement-party” strategy. Polit. Governance9, 263–274. 10.17645/pag.v9i4.4530

51

HibbingJ. R.Theiss-MorseE. (2002). Stealth Democracy: Americans' Beliefs About How Government Should Work. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

52

HöhneB. (2013). Rekrutierung von Abgeordneten des Europäischen Parlaments. Organisation, Akteure und Entscheidungen in Parteien.Opladen; Berlin; Toronto, ON: Verlag Barbara Budrich.

53

HöhneB. (2017). Wie stellen Parteien ihre Parlamentsbewerber auf? Das Personalmanagement vor der Bundestagswahl 2017, in Parteien, Parteiensysteme und politische Orientierungen. Aktuelle Beiträge aus der Parteienforschung, ed KoschmiederC. (Wiesbaden: Springer VS), 227–253.

54

HöhneB. (2021). How democracy works within a populist party: candidate selection in the alternative for Germany. Government and Opposition. 10.1017/gov.2021.33. [Epub ahead of print].

55

HuiC. H.TriandisH. C. (1985). The instability of response sets. Public Opin. Q.49, 253–260. 10.1086/268918

56

HutterS.AltiparmakisA.VidalG. (2019). Diverging Europe: the political consequences of the crises in a comparative perspective, in European Party Politics in Times of Crisis, eds KriesiH.HutterS. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 329–354.

57

IgnaziP. (2018). The four knights of intra-party democracy: a rescue for party delegitimation. Party Polit.26, 9–20. 10.1177/1354068818754599

58

Initiative D21 e.V. (2021). D21-Digital-Index 2021/2022 - J?hrliches Lagebild zur Digitalen Gesellschaft. Report Initiative D21. Available online at: https://initiatived21.de/app/uploads/2022/02/d21-digital-index-2021_2022.pdf

59

KamenovaV. (2021). Internal democracy in populist right parties: the process of party policy development in the alternative for Germany. Euro. Polit. Sci. Rev.13, 488–505. 10.1017/S1755773921000217

60

KatzR.MairP. (1992). The membership of political parties in European democracies, 1960-1990. Euro. J. Polit. Res.22, 329–345. 10.1111/j.1475-6765.1992.tb00316.x

61

KenigO. (2009). Democratization of party leadership selection: do wider selectorates produce more competitive contests?Elect. Stud.28, 240–247. 10.1016/j.electstud.2008.11.001

62

KernellG. (2015). Party nomination rules and campaign participation. Comp. Polit. Stud.48, 1814–1843. 10.1177/0010414015574876

63

KöllnA. K. (2014). Party membership in Europe: testing party-level explanations of decline. Party Polit.22, 465–477. 10.1177/1354068814550432

64

KooS. (2021). Does policy motivation drive party activism? A study of party activists in three Asian democracies. Party Polit.27, 187–201. 10.1177/1354068820908021

65

LanzoneM. E.RombiS. (2018). Selecting candidates online in Europe: a comparison among the cases of M5S, Podemos and European Green Party, in Democratizing Candidate Selection: New Methods, Old Receipts?, eds CorderoG.CollerX. (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 99–121. 10.1007/978-3-319-76550-1_5

66

LardeuxL.TiberjV. (eds.). (2021). Générations désenchantées? Jeunes et démocratie. Paris: La documentation francaise.

67

LavezzoloS.RamiroL. (2018). Stealth democracy and the support for new and challenger parties. Euro. Polit. Sci. Rev.10, 267–289. 10.1017/S1755773917000108

68

LioyA.Del ValleM. E.GottliebJ. (2019). Platform politics: party organisation in the digital age. Information Polity24, 41–58. 10.3233/IP-180093

69

LisiM. (2019). New challenges, old parties: party change in portugal after the European crisis, in Political Institutions and Democracy in Portugal: Assessing the Impact of the Eurocrisis, eds PintoA.TeixeiraC. (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 145–165.

70

LübkerM. (2002). Mitgliederentscheide und Urwahlen aus Sicht der Parteimitglieder: empirische Befunde der Potsdamer Mitgliederstudie. Zeitschrift Parlamentsfragen33, 716–739.

71

MargolisM.ResnickD. (2000). Politics as Usual: The Cyberspace 'Revolution'. London: Sage.

72

MargolisM.ResnickD.LevyJ. (2003). Major parties dominate, minor parties struggle: US elections and the internet, in Political Parties and the Internet: Net Gain?, eds GibsonR.NixonP.WardS. (London: Routledge) 51–69.

73

MergelI.EdelmannN.HaugN. (2019). Defining digital transformation: Results from expert interviews. Gov Info Q. 36:101385. 10.1016/j.giq.2019.06.002

74

MichelsD.BoruckiI. (2021). Die Organisationsreform der SPD 2017-2019: Jung, weiblich und digital?Polit. Vierteljahresschr.62, 121–148. 10.1007/s11615-020-00271-1

75

MichlF. (2021). Anything goes! - Zur Aufstellung von Wahlbewerbern in der Covid-19-Pandemie. Zeitschrift Parteienwissenschaften27, 29–36. 10.24338/mip-202129-36

76

MikolaB. (2017). Online primaries and intra-party democracy: candidate selection processes in Podemos and the Five Star Movement. IDP Revista de Internet Derecho y Política24, 37–49. 10.7238/idp.v0i24.3070

77

NeumannA. (2013). Das “Jahrzehnt der Parteireform” - Ein Überblick über die Entwicklungen, in Parteien ohne Mitglieder?, eds von AlemannU.MorlokM.SpierT. (Baden-Baden: Nomos), 239–247.

78

PanebiancoA. (1988). Political Parties: Organization and Power. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

79

RandallV.SvåsandL. (2002). Party institutionalization in new democracies. Party Polit.8, 5–29. 10.1177/1354068802008001001

80

RanioloF.TarditiV. (2019). Digital revolution and party innovations: an analysis of the Spanish case. Ital. Polit. Sci. Rev.50, 1–19. 10.1017/ipo.2019.27

81

RobertsG. (1988). The German Federal Republic: the two-lane route to bonn, in Candidate Selection in Comparative Perspective: The Secret Garden of Politics, eds GallagherM.MarshM. (London; Newbury Park, CA; New Delhi; Beverly Hills, CA: Sage), 94–118.

82

ScarrowS. (2014). Beyond Party Members: Changing Approaches to Partisan Mobilization.Oxford: Oxford University Press.

83

SchindlerD. (2021). More free-floating, less outward-looking. How more inclusive candidate selection procedures (could) matter. Party Polit.27, 11201131. 10.1177/1354068820926477

84

SchindlerD.HöhneB. (2020). No need for wider selectorates? Party members' preferences for reforming the nomination of district and list candidates for the German Bundestag, in Politische Vierteljahresschrift (PVS): Continuity of Party Democracies in Europe, eds BukowS.JunU. (Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien), 283–308.

85

SchradieJ. (2018). The digital activism gap: how class and costs shape online collective action. Soc. Probl.65, 51–74. 10.1093/socpro/spx042

86

SchüttemeyerS. (2002). Wer wählt wen wie aus? Pfade in das unerschlossene Terrain der Kandidatenaufstellung. Gesellschaft Wirtschaft Politik51, 145–161.

87

SchüttemeyerS.PyschnyA. (2020). Kandidatenaufstellung zur Bundestagswahl 2017. Untersuchungen zu personellen und partizipatorischen Grundlagen demokratischer Ordnung. Zeitschrift Parlamentsfragen51, 189–211. 10.5771/0340-1758-2020-1-189

88

SchüttemeyerS. S.SturmR. (2005). Der Kandidat - das (fast) unbekannte Wesen: Befunde und Überlegungen zur Aufstellung der Bewerber zum Deutschen Bundestag. Zeitschrift Parlamentsfragen36, 539–553.

89

SerranoJ. C. M.ShahrezayeM.PapakyriakopoulosO.HegelichS. (2019). The rise of Germany's AfD: a social media analysis, in Proceedings of International Conference on Social Media and Society (Toronto, ON). p. 14–223. 10.1145/3328529.3328562

90

SettlesK.ShahgholiS.SiefkenS. (2021). Wahlkreisarbeit in der pandemie: mehr adaption als transformation. Zeitschrift Parlamentsfragen52, 758–775. 10.5771/0340-1758-2021-4-758

91

ShomerY.PutG. J.Gedalya-LavyE. (2016). Intra-party politics and public opinion: how candidate selection processes affect citizens' satisfaction with democracy. Polit. Behav.38, 509–534. 10.1007/s11109-015-9324-6

92

SpierT. (2019). Not dead yet? Explaining party member activity in Germany. German Polit.28, 282–303. 10.1080/09644008.2018.1528237

93

SpierT.KleinM. (2015). Party membership in Germany. Rather formal, therefore uncool?, in Party Members and Activists, eds GaujaA.van HauteE. (Abingdon, VA; Oxfordshire; New York, NY: Routledge), 84–99.

94

TheocharisY.de MoorJ. (2021). Creative participation and the expansion of political engagement, in Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics. Oxford University Press. 10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.1972

95

ThuermerG.RothS.Luczak-RöschM.O'HaraK. (2016). use, in- and exclusion in decision-making processes within political parties, in Proceedings of the 8th ACM Conference on Web Science (New York, NY: Association for Computing Machinery). p. 205–214. 10.1145/2908131.2908149

96

Trittin-UlbrichH.SchererA. G.MunroI.WhelanG. (2021). Exploring the dark and unexpected sides of digitalization: toward a critical agenda. Organization28, 8–25. 10.1177/1350508420968184

97