Abstract

Background/objective:

Allergic diseases, such as bronchial asthma, allergic rhinitis, atopic dermatitis, and psychiatric disorders, are major health issues. There have been reports that allergic diseases were associated with depression or anxiety disorders. This study aimed to investigate the association between these allergic diseases and the risk of developing overall psychiatric disorders in patients from Taiwan.

Methods:

This cohort study used the database of the Taiwan National Health Insurance Program. A total of 186,588 enrolled patients, with 46,647 study subjects who had suffered from allergic diseases, and 139,941 controls matched for sex and age, from the Longitudinal Health Insurance Dataset of 2000–2015, were selected from a sub-dataset of the National Health Insurance Research Database. Fine and Gray’s competing risk model analysis was used to explore the hazard ratio (HR), and 95% confidence interval, for the risk of allergic diseases being associated with the risk of developing psychiatric disorders during the 15 years of follow-up.

Results:

Of the study subjects, 5,038 (10.8%) developed psychiatric disorders when compared to 9,376 (6.7%) in the control group, with significant difference (p < 0.001). Fine and Gray’s competing risk model analysis revealed that the adjusted HR was 1.659 (95% CI = 1.602–1.717, p < 0.001). In this study, we found that the groups of atopic dermatitis alone and the allergic rhinitis + atopic dermatitis were associated with a lower risk of psychiatric disorders, but all the other four groups, such as bronchial asthma alone, allergic rhinitis alone, bronchial asthma + allergic rhinitis, bronchial asthma + atopic dermatitis, and the combination of all these three allergic diseases, were associated with a higher risk of psychiatric disorders.

Conclusion:

Allergic diseases are therefore associated with a 1.66-fold increased hazard of psychiatric disorders in Taiwan.

Introduction

Child and adolescent allergic diseases, such as bronchial asthma, allergic rhinitis, and atopic dermatitis, are common and have made an impact on the patients’ physical health (1–3). Furthermore, previous studies have shown the association between asthma and anxiety (4), depressive, bipolar, and overall mood disorders (5, 6), attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (7, 8), schizophrenia (9), and even dementia (10). Some studies have also demonstrated the associations between allergic rhinitis and depressive disorder (11, 12) or bipolar disorder (13). The association between atopic dermatitis and depressive and anxiety disorders has also been reported (14). However, another study found that allergic diseases such as rhinitis or urticarial are associated with a lower risk of schizophrenia (15). Therefore, a study is needed for the overall consideration of the association between these three common allergic diseases and important psychiatric disorders.

Psychiatric, or mental, disorders are defined as clinically significant behavioral or psychological syndromes, which are associated with present distress, disability, or an increased risk of suffering death, pain, or disability, and subsequent behavioral, psychological, or biological dysfunctions (16, 17). Previous studies have found that some psychiatric disorders are associated with several inflammatory diseases (18, 19), such as multiple sclerosis (20, 21), fibromyalgia (22, 23), or inflammatory bowel diseases (24). Psychological stressors related to these diseases might also contribute to both psychiatric and physical morbidity (25, 26).

Recent studies have been increasing on the interactions between allergy-related inflammatory or immunological factors and psychiatric disorders, such as depression (27), anxiety (28), bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia (29). However, further study is still needed to clarify the mechanisms underlying the association between allergic diseases and psychiatric disorders. Nevertheless, the association between allergic diseases and psychiatric disorders has not, as yet, been studied. Therefore, a nationwide, population-based study is necessary for the association between allergic diseases and the risk of psychiatric disorders for the clinicians who actually care for these patients.

Materials and Methods

Data Sources

The National Health Insurance (NHI) Program was launched in Taiwan in 1995, and as of June 2009, included contracts with 97% of the medical providers with approximately 23 million beneficiaries or more than 99% of the entire population (30, 31). The National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD), which contains all the claims data of the beneficiaries, uses the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes to record diagnoses (32). The details of the program have been documented in previous studies (22, 33–42).

A subset of the NHIRD, Longitudinal Health Insurance Database of a two million randomized sampled population in 2000–2015, was used to study the association between allergic diseases and the risk of psychiatric disorders. The present study used the NHIRD to identify patients with the diagnosis of allergic diseases, based on the ICD-9-CM codes, such as bronchial asthma (ICD-9-CM: 493.x), allergic rhinitis (ICD-9 CM code 477.X), and atopic dermatitis (ICD-9-CM code 691.X) during this period. The Institutional Review Board of the Tri-Service General Hospital approved this study and waived the need for individual written informed consent (IRB No. 2-105-05-040 and IRB No. 2-105-05-082).

Study Design and Sampled Participants

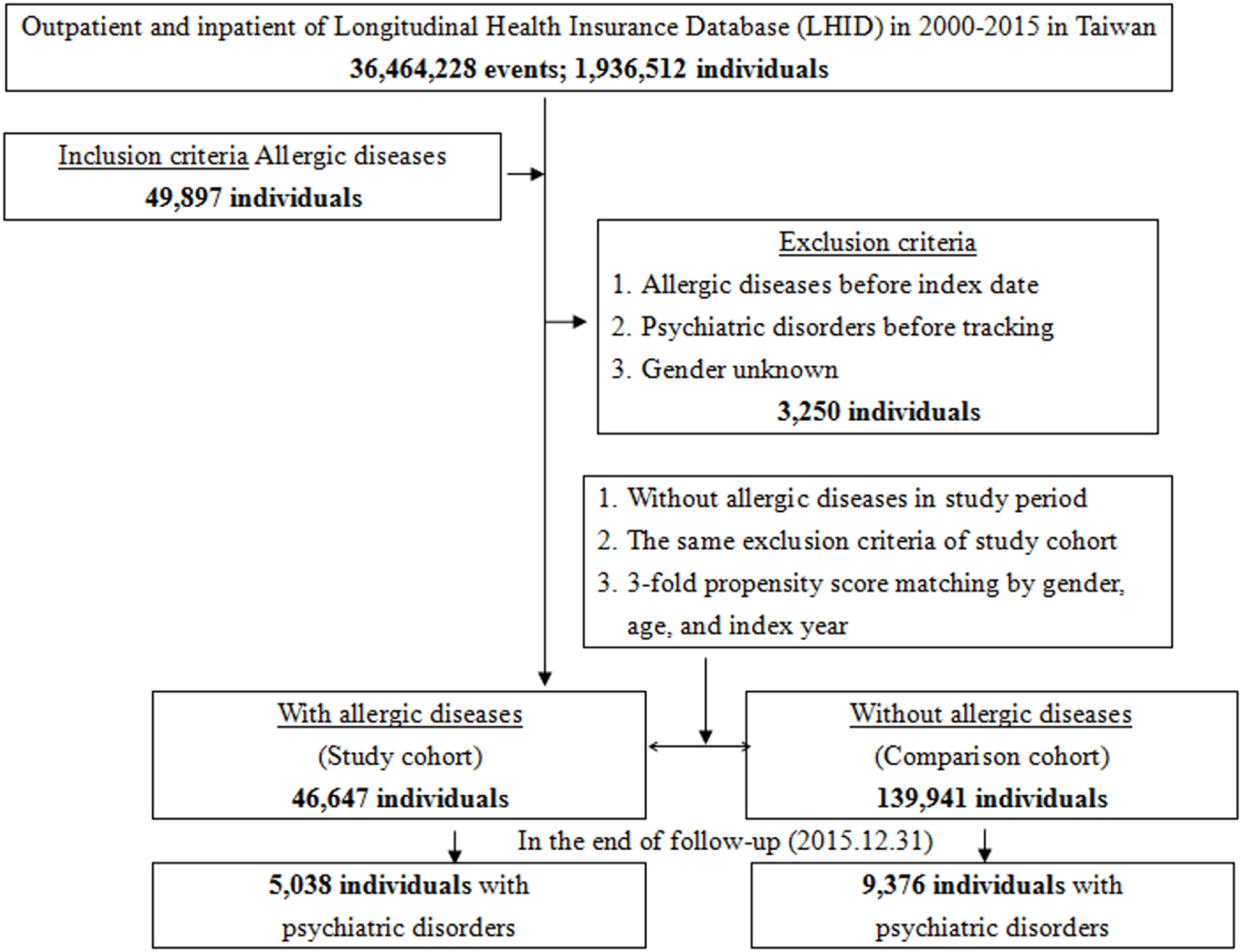

This study was of a population-based, matched-cohort design. Patients with newly diagnosed bronchial asthma, allergic rhinitis, or atopic dermatitis were selected from the Longitudinal Health Insurance Database from January 1, 2000, to December 31, 2015. The patients with asthma, allergic rhinitis, or atopic dermatitis before 2000 were excluded. This method could be viewed as a wash-out period to make sure all the allergic diseases were recent onset with references from other studies for the association between allergic diseases and psychiatric morbidity, using the NHIRD (6, 7, 11, 15). This wash out period method could avoid the carry-over bias from exposure to the pre-existing allergic diseases. In addition, the patients diagnosed with dementia, depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, eating disorders, bipolar disorders, sleep disorders, and psychotic disorders, before 2000, or before their first visit for asthma, allergic rhinitis, or atopic dermatitis were also excluded. Each enrolled patient was required to have made at least three outpatient visits within the 1-year study period for allergic diseases according to these ICD-9-CM codes. A total of the patients who were enrolled, including 46,647 subjects with allergic diseases and 139,941 controls without allergic diseases, were matched for age, sex, and index date (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Flowchart of the study sample selection from the National Health Insurance Research Database in Taiwan.

Covariates

The covariates included sex, age groups (<20, 20–49, ≥50 years), geographical area of residence (north, center, south, and east of Taiwan), urbanization level of residence (levels 1–4), and monthly income (in New Taiwan Dollars; <18,000, 18,000–34,999, and ≥35,000). The urbanization level of residence was defined according to the population and various indicators of the level of development. Level 1 was defined as a population of >1,250,000, and a specific designation as political, economic, cultural, and metropolitan development. Level 2 was defined as a population between 500,000 and 1,249,999 and as playing an important role in the politics, economy, and culture. Urbanization levels 3 and 4 were defined as a population between 149,999 and 499,999, and <149,999, respectively (43).

Comorbidities

Comorbidities were assessed using the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), which categorizes the comorbidities using the ICD-9-CM codes, scores each comorbidity category (44–49), and combines all scores to calculate a single comorbidity score. A score of zero indicates that no comorbidities were found, and higher scores indicate higher comorbidity burdens (31).

Major Outcome

All of the study participants were followed from the index date until the onset of dementia (ICD-9-CM codes: 290.0, 290.10, 290.11, 290.12, 290.13, 290.20, 290.21, 290.3, 290.41, 290.42, 290.43, 290.8, 290.9, and 331.0), anxiety disorders (ICD-9-CM 300), depressive disorders (ICD-9-CM 296.2–296.3, 300.4, and 311), eating disorders (anorexia nervosa 307.1, bulimia nervosa 307.51, and other disorders of eating 307.59), bipolar disorders (ICD-9-CM 296.0, and 296.4–296.8), sleep disorders (ICD-9-CM 307.4 and 780.5), and psychotic disorders (ICD-9-CM 295 and 297–298), withdrawal from the NHI program, or the end of 2015. In addition, each psychiatric diagnosis was required to have made at least three outpatient visits within the 1-year study period for psychiatric disorders according to these ICD-9-CM codes.

Statistical Analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS for Windows, version 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). χ2 and t tests were used to evaluate the distributions of the categorical and continuous variables, respectively, with a Fisher’s exact examination. Fine and Gray’s competing risk analysis was used to determine the risk of psychiatric disorders since death can act as a competing risk factor for psychiatric disorders (40, 50, 51). The results were presented as hazard ratio (HR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI). Differences in the risk of psychiatric disorders between the study and control groups were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method with the log-rank test. A two-tailed p value < 0.05 was considered to indicate the statistical significance.

Results

Baseline Characteristics of the Study Population

The baseline characteristics of the study population are depicted in Table 1. There were 46,647 subjects in the allergic diseases group and 139,941 non-allergic diseases in the control group, with a similar distribution of sex, age, marital status, education years, and monthly insured premiums. The mean CCR (SD) for the subjects was 1.32 (1.10) and 0.67 (1.68) for the allergic diseases and control group, respectively. The subjects had more medical visits in the spring and winter, with residence in the south, east, and offshore islands of Taiwan, living in levels 3 and 4 in urbanization, or seeking help in local hospitals than the control group (p < 0.001 for all). In the subjects with allergic diseases, 40,405 have asthma, 1,809, allergic rhinitis, and 4,433, atopic dermatitis.

Table 1

| Allergic diseases | With | Without | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||

| Variables | n | % | n | % | p |

| Total | 46,647 | 25.00 | 139,941 | 75.00 | |

| Gender | 0.999 | ||||

| Male | 27,162 | 58.23 | 81,486 | 58.23 | |

| Female | 19,485 | 41.77 | 58,455 | 41.77 | |

| Age (years) | 44.82 ± 30.58 | 44.83 ± 27.77 | 0.948 | ||

| Age group (years) | 0.999 | ||||

| <20 | 14,766 | 31.65 | 44,298 | 31.65 | |

| 20–49 | 6,174 | 13.24 | 18,522 | 13.24 | |

| ≥50 | 25,707 | 55.11 | 77,121 | 55.11 | |

| Married | 0.147 | ||||

| Without | 20,526 | 44.00 | 61,476 | 43.62 | |

| With | 26,121 | 56.00 | 79,465 | 56.38 | |

| Education (years) | 0.421 | ||||

| <12 | 13,757 | 29.49 | 40,997 | 29.30 | |

| ≥12 | 32,890 | 70.51 | 98,944 | 70.70 | |

| Insured premium (New Taiwan Dollars) | 0.437 | ||||

| <18,000 | 37,275 | 79.91 | 111,495 | 79.67 | |

| 18,000–34,999 | 5,520 | 11.83 | 16,642 | 11.89 | |

| ≥35,000 | 3,852 | 8.26 | 11,804 | 8.43 | |

| CCI_R | 1.32 ± 1.10 | 0.67 ± 1.68 | <0.001 | ||

| Season | <0.001 | ||||

| Spring (March–May) | 12,770 | 27.38 | 37,326 | 26.67 | |

| Summer (June–August) | 11,376 | 24.39 | 35,204 | 25.16 | |

| Autumn (September–November) | 10,095 | 21.64 | 30,807 | 22.01 | |

| Winter (December–February) | 12,406 | 26.60 | 36,604 | 26.16 | |

| Location | <0.001 | ||||

| Northern Taiwan | 16,460 | 35.29 | 56,914 | 40.67 | |

| Middle Taiwan | 12,150 | 26.05 | 38,437 | 27.47 | |

| Southern Taiwan | 13,324 | 28.56 | 35,541 | 25.40 | |

| Eastern Taiwan | 4,398 | 9.43 | 8,117 | 5.80 | |

| Outlets islands | 315 | 0.68 | 932 | 0.67 | |

| Urbanization level | <0.001 | ||||

| 1 (the highest) | 12,504 | 26.81 | 50,018 | 35.74 | |

| 2 | 18,131 | 38.87 | 59,219 | 42.32 | |

| 3 | 4,319 | 9.26 | 9,957 | 7.12 | |

| 4 (the lowest) | 11,693 | 25.07 | 20,747 | 14.83 | |

| Level of care | <0.001 | ||||

| Hospital center | 8,046 | 17.25 | 45,001 | 32.16 | |

| Regional hospital | 13,379 | 28.68 | 43,677 | 31.21 | |

| Local hospital | 25,222 | 54.07 | 51,263 | 36.63 | |

Characteristics of study at the baseline.

p: Chi-square/Fisher’s exact test on category variables and t-test on continue variables.

Without married: un-married, divorce, spouse death, and unknown.

CCI_R, Charlson comorbidity index removed dementia.

Allergic Diseases Associated With Psychiatric Disorders

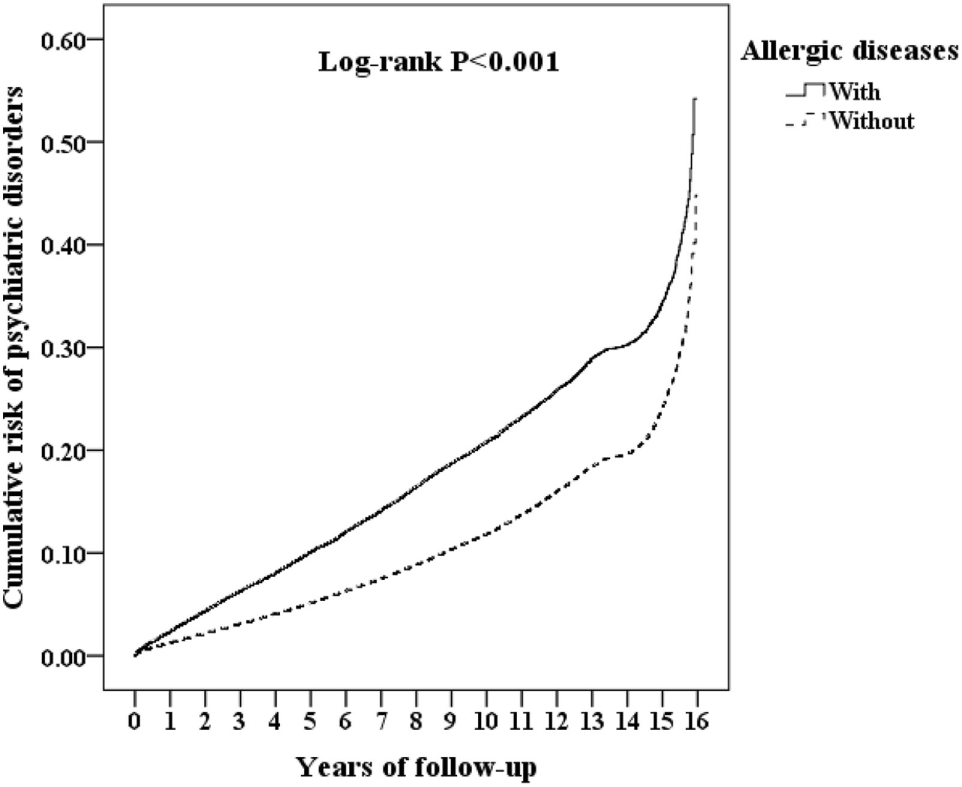

Of the study subjects, 5,038 (10.8%) developed psychiatric disorders when compared to 9,376 (6.7%) in the control group, in the 15-year follow-up. We have also examined the risk of psychiatric disorders associated with allergic diseases. After adjusting for age, sex, CCI scores, and all the covariates, the Fine and Gray’s survival analysis revealed that the adjusted HR for psychiatric disorders was 1.659 for the subjects (95% CI = 1.602–1.717, p < 0.001) when compared with the control group. With reference to the female subjects, the male subjects were associated with a higher risk of psychiatric disorders. With reference to the younger group (aged < 20 years), older age groups (aged 20–49 years and aged ≥ 50 years) were associated with a higher risk of psychiatric disorders (p < 0.001) (Table 2). Figure 2 shows the Kaplan–Meier analysis for the cumulative incidence of psychiatric disorders in the study subjects and the control groups (log-rank test, p < 0.001).

Table 2

| Model | Competing risk in the model | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Variables | Adjusted HR | 95% CI | 95% CI | p |

| Allergic diseases | ||||

| Without | Reference | |||

| With | 1.659 | 1.602 | 1.717 | <0.001 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 1.108 | 1.072 | 1.146 | <0.001 |

| Female | Reference | |||

| Age group (years) | ||||

| <20 | Reference | |||

| 20–49 | 3.807 | 3.375 | 4.293 | <0.001 |

| ≥50 | 8.747 | 7.819 | 9.784 | <0.001 |

Factors of psychiatric disorders by using Fine and Gray’s competing risk model.

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; adjusted HR, adjusted variables listed in Table 1.

Figure 2

Kaplan–Meier for the cumulative risk of psychiatric disorders stratified by allergic diseases with the log-rank test.

Furthermore, each single increased score of CCI was associated with a 2% increased risk of psychiatric disorders, and study subjects who sought medical help in the summer (adjusted HR 0.914, p < 0.001), autumn (adjusted HR 0.748, p < 0.001), and winter (adjusted HR 0.921, p < 0.001) were associated with a lower risk of psychiatric disorders (data not shown). Study subjects who live in urbanization level 3 were associated with a lower risk of psychiatric disorders than those in level 4 (adjusted HR 0.817, p < 0.001). Study subjects who sought medical help in the medical centers (adjusted HR 0.504, p < 0.001) and regional hospitals (adjusted HR 0.635, p < 0.001) were associated with a lower risk of psychiatric disorders than those in the local hospitals (data not shown).

Association Between Different Allergic Diseases and Risk of Psychiatric Disorders

Table 3 reveals that the association between each group of allergic diseases and the individual psychiatric disorders using Fine and Gray’s competing risk model. The subjects with atopic dermatitis were associated with a decreased risk of overall and individual psychiatric disorders.

Table 3

| Allergic diseases (with vs. without) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Psychiatric disorders subgroup | Adjusted HR | 95% CI | 95% CI | p |

| Overall | 1.659 | 1.602 | 1.717 | <0.001 |

| Dementia | 1.193 | 1.152 | 1.234 | <0.001 |

| Anxiety | 2.397 | 2.315 | 2.481 | 0.009 |

| Eating disorders | 2.646 | 2.555 | 2.739 | <0.001 |

| Anorexia nervosa | 2.573 | 2.485 | 2.663 | 0.003 |

| Bulimia nervosa | – | – | – | – |

| Other disorders of eating | 3.087 | 2.981 | 3.195 | 0.003 |

| Depression | 1.412 | 1.364 | 1.461 | <0.001 |

| Bipolar disorders | 1.124 | 1.086 | 1.163 | 0.001 |

| Sleep disorders | 2.302 | 2.223 | 2.383 | 0.007 |

| Psychotic disorders | 1.192 | 1.151 | 1.234 | 0.003 |

|

|

||||

| Asthma | 1.780 | 1.719 | 1.842 | <0.001 |

| Dementia | 1.293 | 1.249 | 1.339 | 0.007 |

| Anxiety | 2.579 | 2.491 | 2.669 | <0.001 |

| Eating disorders | 2.943 | 2.842 | 3.046 | 0.010 |

| Anorexia nervosa | 2.861 | 2.763 | 2.961 | 0.003 |

| Bulimia nervosa | – | – | – | – |

| Other disorders of eating | 3.434 | 3.316 | 3.554 | <0.001 |

| Depression | 1.482 | 1.431 | 1.533 | 0.004 |

| Bipolar disorders | 1.180 | 1.139 | 1.221 | <0.001 |

| Sleep disorders | 2.483 | 2.398 | 2.570 | <0.001 |

| Psychotic disorders | 1.260 | 1.217 | 1.304 | 0.001 |

|

|

||||

| Allergic rhinitis | 1.156 | 1.117 | 1.197 | <0.001 |

| Dementia | 0.329 | 0.317 | 0.340 | 0.027 |

| Anxiety | 1.806 | 1.744 | 1.870 | 0.001 |

| Eating disorders | 0.000 | – | – | 0.989 |

| Anorexia nervosa | 0.000 | – | – | 0.976 |

| Bulimia nervosa | – | – | – | – |

| Other disorders of eating | 0.000 | – | – | 0.992 |

| Depression | 1.818 | 1.756 | 1.882 | <0.001 |

| Bipolar disorders | 1.303 | 1.258 | 1.349 | <0.001 |

| Sleep disorders | 1.342 | 1.296 | 1.389 | <0.001 |

| Psychotic disorders | 1.331 | 1.285 | 1.377 | <0.001 |

|

|

||||

| Allergic dermatitis | 0.256 | 0.247 | 0.265 | 0.031 |

| Dementia | 0.272 | 0.263 | 0.282 | 0.030 |

| Anxiety | 0.190 | 0.183 | 0.196 | 0.025 |

| Eating disorders | 0.000 | – | – | 0.986 |

| Anorexia nervosa | 0.000 | – | – | 0.977 |

| Bulimia nervosa | – | – | – | – |

| Other disorders of eating | 0.000 | – | – | 0.993 |

| Depression | 0.211 | 0.204 | 0.219 | 0.028 |

| Bipolar disorders | 0.246 | 0.238 | 0.255 | 0.034 |

| Sleep disorders | 0.317 | 0.306 | 0.328 | 0.006 |

| Psychotic disorders | 0.162 | 0.156 | 0.167 | 0.005 |

Factors of psychiatric disorders subgroup stratified by allergic diseases subgroup by using Fine and Gray’s competing risk model.

PYs, person-years; adjusted HR, adjusted hazard ratio: adjusted for the variables listed in Table 1; CI, confidence interval.

In addition, the patients with allergic diseases who live in the middle (adjusted HR: 1.118, p < 0.001), southern (adjusted HR: 1.055, p = 0.003), and eastern Taiwan (adjusted HR: 1.596, p < 0.001) showed slightly higher risk of psychiatric disorders, with reference of those who live in northern Taiwan. The patients who live in area of urbanization level 3 (adjusted HR: 0.763, p < 0.001) showed lower risk of psychiatric disorders, with reference of those who live in the urbanization level 4. The patients who sought for medical help in the hospital centers (adjusted HR: 0.504, p < 0.001) and regional hospitals (adjusted HR: 0.635, p < 0.001) showed lower risk of psychiatric disorders with the reference of local hospitals (Data not shown).

Table 4 reveals the adjusted HR of affective disorders (adjusted HR: 1.385, p = 0.001, in which depression with adjusted HR: 1.412, p = 0.001, and bipolar disorders with adjusted HR: 1.124, p = 0.001), anxiety disorders (adjusted HR: 2.397, p = 0.009), psychotic disorders (adjusted HR: 1.192 p = 0.003), and dementia (adjusted HR: 1.193, p < 0.001) in patients with allergic diseases, when compared to the patients those without allergic diseases.

Table 4

| Allergic diseases (with vs. without) | Competing risk in the model | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Psychiatric disorders subgroup | Adjusted HR | 95% confidence interval (CI) | 95% CI | p |

| Affective disorders | 1.385 | 1.337 | 1.434 | 0.001 |

| Depression | 1.412 | 1.364 | 1.461 | <0.001 |

| Bipolar disorders | 1.124 | 1.086 | 1.163 | 0.001 |

| Anxiety disorders | 2.397 | 2.315 | 2.481 | 0.009 |

| Psychotic disorders | 1.192 | 1.151 | 1.234 | 0.003 |

| Dementia | 1.193 | 1.152 | 1.234 | <0.001 |

Hazard ratio (HR) of affective, anxiety, psychotic disorders, and dementia in patients with vs. without allergic diseases.

We divided the subjects with allergic diseases into six groups: bronchial asthma alone, allergic rhinitis alone, atopic dermatitis alone, bronchial asthma + allergic rhinitis, bronchial asthma + atopic dermatitis, allergic rhinitis + atopic dermatitis, and a combination of all these three allergic diseases. In this study, we found that the groups of atopic dermatitis alone and allergic rhinitis + atopic dermatitis were associated with a lower risk of psychiatric disorders, but the other four groups were associated with a higher risk of psychiatric disorders (Table 5).

Table 5

| Competing risk in the model | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Allergic diseases | 95% CI | 95% CI | p | |

| Without | Reference | |||

| Asthma | 1.780 | 1.719 | 1.842 | <0.001 |

| Allergic rhinitis | 1.156 | 1.117 | 1.197 | <0.001 |

| Atopic dermatitis | 0.256 | 0.247 | 0.265 | 0.031 |

| Asthma + allergic rhinitis | 1.770 | 1.713 | 1.896 | <0.001 |

| Asthma + atopic dermatitis | 1.723 | 1.673 | 1.852 | <0.001 |

| Allergic rhinitis + atopic dermatitis | 0.554 | 0.213 | 0.966 | 0.018 |

| Asthma + allergic rhinitis + atopic dermatitis | 3.702 | 1.613 | 24.978 | 0.027 |

Factors of psychiatric disorders by using Cox regression and Fine and Gray’s competing risk model.

Risk of Psychiatric Disorders Stratified by Covariates

We analyzed the data by the stratification of the factors such as sex, age, marital status, education levels, urbanization level, geographic areas of residence, seasons of medical visits, monthly insured premiums, and levels of care from medical services providers. We found that the subjects, who were either male or female, married or not married, and in different educational years, urbanization levels, residence areas, seasons of visits, insured premiums, and levels of care, were associated with an increased risk of psychiatric disorders. In the different age groups, subjects aged < 20 years were associated with a lower risk of psychiatric disorder, while subjects in other age groups (≥20 years) were associated with a higher risk (Table 6).

Table 6

| Allergic diseases (with vs. without) | Competing risk in the model | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Stratified | Adjusted HR | 95% CI | 95% CI | p |

| Total | 1.659 | 1.602 | 1.717 | <0.001 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 1.705 | 1.646 | 1.765 | <0.001 |

| Female | 1.604 | 1.549 | 1.660 | <0.001 |

| Age group (years) | ||||

| <20 | 0.832 | 0.804 | 0.861 | 0.027 |

| 20–49 | 2.752 | 2.658 | 2.849 | 0.007 |

| ≥50 | 1.651 | 1.595 | 1.709 | 0.001 |

| Married | ||||

| Without | 1.631 | 1.575 | 1.688 | 0.004 |

| With | 1.660 | 1.603 | 1.718 | 0.001 |

| Education (years) | ||||

| <12 | 3.140 | 3.032 | 3.250 | <0.001 |

| ≥12 | 1.266 | 1.222 | 1.310 | 0.011 |

| Insured premium (New Taiwan Dollars) | ||||

| <18,000 | 1.651 | 1.595 | 1.709 | 0.007 |

| 18,000–34,999 | 2.543 | 2.455 | 2.632 | <0.001 |

| ≥35,000 | 1.457 | 1.407 | 1.508 | 0.015 |

| Season | ||||

| Spring | 1.599 | 1.545 | 1.655 | <0.001 |

| Summer | 1.677 | 1.620 | 1.736 | <0.001 |

| Autumn | 1.645 | 1.589 | 1.703 | 0.002 |

| Winter | 1.708 | 1.649 | 1.768 | <0.001 |

| Urbanization level | ||||

| 1 (the highest) | 1.326 | 1.280 | 1.372 | <0.001 |

| 2 | 1.634 | 1.578 | 1.691 | <0.001 |

| 3 | 1.757 | 1.697 | 1.818 | 0.001 |

| 4 (the lowest) | 1.883 | 1.818 | 1.949 | <0.001 |

| Level of care | ||||

| Hospital center | 1.402 | 1.354 | 1.451 | <0.001 |

| Regional hospital | 1.315 | 1.270 | 1.361 | 0.017 |

| Local hospital | 2.023 | 1.954 | 2.094 | <0.001 |

Factors of psychiatric disorders stratified by variables listed in the table by using Fine and Gray’s competing risk model.

PYs, person-years; adjusted HR, adjusted hazard ratio: adjusted for the variables listed in Table 1; CI, confidence interval.

HR Analysis of Psychiatric Disorders in Patients With Different Medications for the Treatment of Asthma

The different medications of treatment durations more than 30 days for the treatment of bronchial asthma were grouped into four classes by the number of subjects who had used these medications: oral prednisolone, inhaled steroids, beta-agonist, aminophylline, leukotriene receptor antagonists, and anti-IgE antibody (omalizumab). Oral prednisolone usage was associated with a lower risk of developing psychiatric disorders in bronchial asthma patients. Besides, usage of beta-agonist, aminophylline, and leukotriene receptor antagonists was also associated with a lower risk of developing psychiatric disorders while adjusted with all the covariates and comorbidities, either with or without prednisolone usage (Table 7).

Table 7

| Medications use | Psychiatric disorders n(%) |

Crude HR (95% CI) | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | Without prednisolone Adjusted HR (95% CI) |

With prednisolone Adjusted HR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prednisolone | |||||

| Yes (n = 20,202) | 2,011 (9.95) | 0.706 (0.465–0.801)** | 0.713 (0.472–0.813)** | N/A | N/A |

| No (n = 20.203) | 2,849 (14.10) | Reference | Reference | ||

|

|

|||||

| Inhaled steroids | |||||

| Yes (n = 8,612) | 988 (11.47) | 0.942 (0.802–1.051) | 0.970 (0.834–1.167) | 0.982 (0.857–1.266) | 0.912 (0.818–1.109) |

| No (n = 31,793) | 3,872 (12.18) | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

|

|

|||||

| Beta-agonist | |||||

| Yes (n = 21,720) | 2,041 (9.40) | 0.623 (0.511–0.729)*** | 0.684 (0.522–0.800)** | 0.697 (0.529–0.824)* | 0.662 (0.513–0.789)** |

| No (n = 18,685) | 2,819 (15.09) | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

|

|

|||||

| Aminophylline | |||||

| Yes (n = 21,898) | 2,020 (9.22) | 0.601 (0.499–0.714)*** | 0.654 (0.513–0.824)** | 0.632 (0.492–0.810)** | 0.678 (0.527–0.883)* |

| No (n = 18,507) | 2,840 (15.35) | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

|

|

|||||

| Leukotriene receptor antagonists | |||||

| Yes (n = 3,345) | 291 (8.70) | 0.706 (0.459–0.816)** | 0.710 (0.469–0.826)** | 0.709 (0.468–0.825)** | 0.712 (0.472–0.829)** |

| No (n = 37,060) | 4,569 (12.33) | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

|

|

|||||

| Anti-IgE antibody | |||||

| Yes (n = 27) | 1 (3.70) | 0.308 (0.007–0.995)* | 0.420 (0.010–1.097) | 0.683 (0.145–2.894) | No patients |

| No (n = 40,378) | 4,859 (12.03) | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

HRs of patients with psychiatric disorders by medication use compared with patients with oral prednisolone use.

Adjusted HR, adjusted hazard ratio: adjusted for the variables listed in Table 1; CI, confidence interval.

*p < 0.05.

**p < 0.01.

***p < 0.001.

Discussion

In this study, we examined the association between the overall allergic diseases and the risk of psychiatric disorders. After adjusting the covariates, the adjusted HR was 1.659 for the subjects (95% CI = 1.602–1.717, p < 0.001) when compared with the control group. In other words, the adult patients with allergic diseases had a 1.66-fold increased risk of developing psychiatric disorders. The Kaplan–Meier analysis revealed that the study subjects had a significantly higher 15-year psychiatric disorders-free survival rate than the controls.

Bronchial asthma and allergic rhinitis were associated with the risk of overall psychiatric disorders, but atopic dermatitis was associated with a lower risk of psychiatric disorders. Bronchial asthma was associated with the risk of individual psychiatric disorders, such as dementia, anxiety disorders, depressive disorders, eating disorders, bipolar disorders, sleep disorders, and psychotic disorders, but allergic rhinitis was associated with a lower risk of dementia and an increased risk of other psychiatric disorders. However, the increasing number of allergic diseases was associated with an increased risk of psychiatric disorders. In comparison to the previous studies for individual allergic diseases in several psychiatric disorders, such as anxiety disorders, depressive disorders, bipolar disorders, schizophrenia, and ADHD (4, 6–8, 10–15, 43), this is the first study on the topic of the association of allergic diseases and the broader spectrum of psychiatric disorders. Atopic dermatitis seems to be an exception in these allergic diseases, by being associated with a lower risk of psychiatric disorders, even though previous reports found that atopic dermatitis are associated with ADHD and autism spectrum disorders (52–55). Further study is needed to clarify the association between atopic dermatitis and the risk of psychiatric disorders.

The results of this study showed the association between overall allergic diseases and the risk of psychiatric disorders, which echoed the findings of other studies on the association between the overall allergic or atopic diseases and the risk of psychiatric disorders: for example, children with eczema, asthma, or hay fever had more emotional, conduct, and hyperactivity problems in a cross-sectional study in Denmark (56), and atopic diseases might be associated with an elevated risk of developing depression in a birth cohort study in Finland (57). Several studies have reported the associations between bronchial asthma or other atopic diseases and psychiatric disorders, such as affective disorders, anxiety disorders, schizophrenia, substance-related disorders, autism-spectrum disorders, or ADHDs (9, 58–62). Some researchers have also reported the associations between atopic dermatitis and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, or speech disorders in childhood (63), and the association between allergic rhinitis and the risk of suicides and depression (64). Furthermore, parental exposure to occupational asthmagens might also be associated with children autism-spectrum disorders (65). Previous studies have also reported the associations between other immune or inflammation-related diseases, such as periodontitis (66), gluten-related illnesses (67), amyotrophiclateral sclerosis (68), psoriasis (69), food or other allergies (70), and idiopathic environmental intolerance (71) and the risk of psychiatric disorders. Conversely, psychiatric disorders might also affect the immune systems (72). In this study, the overall allergic diseases were associated with affective disorders, anxiety disorders, psychotic disorders, and dementia, respectively. The interplay between allergic diseases and psychiatric disorders, therefore, warrant further study.

The underlying mechanism of the association between allergic diseases and psychiatric disorders remains unclear. The “orchestration” of the pro-inflammatory cytokines plays an important role in the pathogenesis of allergy-related diseases, such as asthma (73). Reports have shown that cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-6, tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), IL-10, and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1/CCL2 might be well associated with depressive, bipolar, or anxiety disorders (74, 75). Reports also show that dementia is related to peripheral pro-inflammatory factors released by periodontal inflammatory mediators such as C-reactive protein, IL-6, haptoglobin, TNF-α, and fibrinogen (76–78). Furthermore, some studies have also found that inflammation play an important role in eating disorders (79, 80) and sleep disorders (81–83).

Additionally, we have included several psychosocial factors in the analysis, such as marital status, educational level, monthly insured premiums, urbanization level, and residence. In comparison to the allergy-disease subjects who sought medical help in the local hospitals, study subjects who received medical help from medical centers or regional hospitals were associated with a lower risk of psychiatric disorders. These findings suggest that disadvantageous socioeconomic factors might well contribute to the risk of psychiatric disorders.

We found that the study subjects of those aged < 20 years had a lower risk in developing psychiatric disorders. We therefore hypothesize that the reason for a lower risk is that the maximal follow-up time is 15 years, which might not have, as yet, reached the age of onset of the most major psychiatric disorders for the patients of allergic diseases (84). Further study is needed to clarify the association between age and the risk of psychiatric disorders in the patients with allergic diseases.

Furthermore, we found that oral prednisolone usage was associated with a lower risk of developing psychiatric disorders in bronchial asthma patients. Moreover, the usage of beta-agonist, aminophylline, and leukotriene receptor antagonists was also associated with a lower risk of developing psychiatric disorders, with or without prednisolone usage. The mechanisms and effects of these medications on the risk of psychiatric disorders in bronchial asthma patients merit further study.

Limitations

The present study has several limitations that warrant consideration. First, similar to previous studies using the NHIRD on allergic diseases as aforementioned, not all the data were recorded in the NHIRD, and we were unable to evaluate the severity, weakness severity, laboratory parameters, or lung function examinations in asthma patients. Second, other factors, such as genetic, psychosocial, and environmental factors, were not included in the dataset. Third, for patients who have to pay for their own for over-the-counter drugs for the allergic diseases, their self-medications would not have been included in the NHIRD. There is no study about the rates of self-medications for these allergic diseases. However, due to the high coverage of medical providers (97%) and beneficiaries (more than 99%) of the NHI system in Taiwan, most of the people would ask for help from the NHI-contracted hospital or clinics for their allergic diseases.

Strength of This Study

One of the primary strengths of this study is the use of ICD-9 codes, and a number of studies have demonstrated the accuracy and validity of several diagnoses in the NHIRD, including DM (85, 86), cancer (87–89), myocardial infarction (85, 90, 91), and central nervous system diseases, such as Tourette syndrome (92), and stroke (85, 93–95), outcomes (89), mortality (85, 96), or comorbidity (89, 96). In a wide spectrum of conditions, some studies have also demonstrated the concordance between Taiwan’s National Health Survey and the NHIRD on various diagnoses (97), medication usage (97), and health system utilizations (97, 98). Correspondingly, the long-term observation period from 2000 to 2015 allowed for more credibility, when compared with other similar studies, to propose physical mechanisms and plausible hypotheses. Finally, and most importantly, we have tried to explain the mutual biological and psychological mechanism between the allergic diseases and the psychiatric disorders.

Conclusion

We have evaluated the risk of psychiatric disorders in association with the allergic diseases such as asthma, allergic rhinitis, and atopic dermatitis in Taiwan’s population, using the representative population-based data. We have demonstrated that the patients with allergic diseases were at a significantly higher risk of psychiatric disorders than the control group. Further studies are therefore needed for patients with allergic diseases not only to prevent its clinical exacerbation but also to decrease the possibility of developing psychiatric disorders. We sincerely hope that this study will provide the necessary information for an earlier intervention for patients with allergic diseases.

Statements

Ethics statement

The Institutional Review Board of the Tri-Service General Hospital approved this study and waived the need for individual written informed consent (IRB No. 2-105-05-040 and IRB No. 2-105-05-082).

Author contributions

N-ST, H-AC, and W-CC conceived, planned, and conducted this study. C-HC and W-SC contributed to the data analysis and interpretation. Y-CK, C-CC, H-WY, Y-CC, and S-Y contributed to this data interpretation. N-ST wrote the draft. All the authors approved this manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported in part by the Tri-Service General Hospital Research Foundation (TSGH-C106-002, TSGH-C106-106, and TSGH-C107-004). These funding agencies did not influence the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1

Hong S Son DK Lim WR Kim SH Kim H Yum HY et al The prevalence of atopic dermatitis, asthma, and allergic rhinitis and the comorbidity of allergic diseases in children. Environ Health Toxicol (2012) 27:e2012006.10.5620/eht.2012.27.e2012006

2

Grize L Gassner M Wuthrich B Bringolf-Isler B Takken-Sahli K Sennhauser FH et al Trends in prevalence of asthma, allergic rhinitis and atopic dermatitis in 5–7-year old Swiss children from 1992 to 2001. Allergy (2006) 61(5):556–62.10.1111/j.1398-9995.2006.01030.x

3

Yan DC Ou LS Tsai TL Wu WF Huang JL . Prevalence and severity of symptoms of asthma, rhinitis, and eczema in 13- to 14-year-old children in Taipei, Taiwan. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol (2005) 95(6):579–85.10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61022-8

4

Lee YC Lee CT Lai YR Chen VC Stewart R . Association of asthma and anxiety: a nationwide population-based study in Taiwan. J Affect Disord (2016) 189:98–105.10.1016/j.jad.2015.09.040

5

Lin TC Lee CT Lai TJ Lee CT Lee KY Chen VC et al Association of asthma and bipolar disorder: a nationwide population-based study in Taiwan. J Affect Disord (2014) 168:30–6.10.1016/j.jad.2014.06.033

6

Chen MH Su TP Chen YS Hsu JW Huang KL Chang WH et al Higher risk of developing major depression and bipolar disorder in later life among adolescents with asthma: a nationwide prospective study. J Psychiatr Res (2014) 49:25–30.10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.10.015

7

Chen MH Su TP Chen YS Hsu JW Huang KL Chang WH et al Asthma and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a nationwide population-based prospective cohort study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry (2013) 54(11):1208–14.10.1111/jcpp.12087

8

Chen MH Su TP Chen YS Hsu JW Huang KL Chang WH et al Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, tic disorder, and allergy: is there a link? A nationwide population-based study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry (2013) 54(5):545–51.10.1111/jcpp.12018

9

Wang WC Lu ML Chen VC Ng MH Huang KY Hsieh MH et al Asthma, corticosteroid use and schizophrenia: a nationwide population-based study in Taiwan. PLoS One (2017) 12(3):e0173063.10.1371/journal.pone.0173063

10

Chen MH Li CT Tsai CF Lin WC Chang WH Chen TJ et al Risk of dementia among patients with asthma: a nationwide longitudinal study. J Am Med Dir Assoc (2014) 15(10):763–7.10.1016/j.jamda.2014.06.003

11

Chen MH Su TP Chen YS Hsu JW Huang KL Chang WH et al Allergic rhinitis in adolescence increases the risk of depression in later life: a nationwide population-based prospective cohort study. J Affect Disord (2013) 145(1):49–53.10.1016/j.jad.2012.07.011

12

Hsu CL Wang TC Shen TC Huang YJ Lin CL Sung FC . Risk of depression in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis: a nationwide population-based retrospective cohort study. J Affect Disord (2016) 206:294–9.10.1016/j.jad.2016.09.001

13

Chen MH Lan WH Hsu JW Huang KL Chen YS Li CT et al Risk of bipolar disorder among adolescents with allergic rhinitis: a nationwide longitudinal study. J Psychosom Res (2015) 79(6):533–6.10.1016/j.jpsychores.2015.08.009

14

Cheng CM Hsu JW Huang KL Bai YM Su TP Li CT et al Risk of developing major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders among adolescents and adults with atopic dermatitis: a nationwide longitudinal study. J Affect Disord (2015) 178:60–5.10.1016/j.jad.2015.02.025

15

Chen YH Lee HC Lin HC . Prevalence and risk of atopic disorders among schizophrenia patients: a nationwide population based study. Schizophr Res (2009) 108(1–3):191–6.10.1016/j.schres.2008.12.021

16

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. USA: American Psychiatric Association (1994).

17

Stein DJ Phillips KA Bolton D Fulford KW Sadler JZ Kendler KS . What is a mental/psychiatric disorder? From DSM-IV to DSM-V. Psychol Med (2010) 40(11):1759–65.10.1017/S0033291709992261

18

Marrie RA Walld R Bolton JM Sareen J Walker JR Patten SB et al Rising incidence of psychiatric disorders before diagnosis of immune-mediated inflammatory disease. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci (2017):1–10.10.1017/S2045796017000579

19

Marrie RA Walld R Bolton JM Sareen J Walker JR Patten SB et al Increased incidence of psychiatric disorders in immune-mediated inflammatory disease. J Psychosom Res (2017) 101:17–23.10.1016/j.jpsychores.2017.07.015

20

Marrie RA Reingold S Cohen J Stuve O Trojano M Sorensen PS et al The incidence and prevalence of psychiatric disorders in multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. Mult Scler (2015) 21(3):305–17.10.1177/1352458514564490

21

Marrie RA Horwitz R Cutter G Tyry T Campagnolo D Vollmer T . The burden of mental comorbidity in multiple sclerosis: frequent, underdiagnosed, and undertreated. Mult Scler (2009) 15(3):385–92.10.1177/1352458508099477

22

Chao PC Chien WC Chung CH Chu CW Yeh CB Huang SY et al Cognitive enhancers associated with decreased risk of injury in patients with dementia: a nationwide cohort study in Taiwan. J Investig Med (2017) 66(3):684–92.10.1136/jim-2017-000595

23

Cunningham NR Tran ST Lynch-Jordan AM Ting TV Sil S Strotman D et al Psychiatric disorders in young adults diagnosed with juvenile fibromyalgia in Adolescence. J Rheumatol (2015) 42(12):2427–33.10.3899/jrheum.141369

24

Chen YT Su JS Tseng CW Chen CC Lin CL Kao CH . Inflammatory bowel disease on the risk of acute pancreatitis: a population-based cohort study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol (2016) 31(4):782–7.10.1111/jgh.13171

25

Suarez AL Feramisco JD Koo J Steinhoff M . Psychoneuroimmunology of psychological stress and atopic dermatitis: pathophysiologic and therapeutic updates. Acta Derm Venereol (2012) 92(1):7–15.10.2340/00015555-1188

26

Sgambato D Miranda A Ranaldo R Federico A Romano M . The role of stress in inflammatory bowel diseases. Curr Pharm Des (2017) 23(27):3997–4002.10.2174/1381612823666170228123357

27

Voorhees JL Tarr AJ Wohleb ES Godbout JP Mo X Sheridan JF et al Prolonged restraint stress increases IL-6, reduces IL-10, and causes persistent depressive-like behavior that is reversed by recombinant IL-10. PLoS One (2013) 8(3):e58488.10.1371/journal.pone.0058488

28

Trueba AF Ritz T Trueba G . The role of the microbiome in the relationship of asthma and affective disorders. Adv Exp Med Biol (2016) 874:263–88.10.1007/978-3-319-20215-0_13

29

Altamura AC Buoli M Pozzoli S . Role of immunological factors in the pathophysiology and diagnosis of bipolar disorder: comparison with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci (2014) 68(1):21–36.10.1111/pcn.12089

30

Ho Chan W . Taiwan’s healthcare report 2010. EPMA J (2010) 1(4):563–85.10.1007/s13167-010-0056-8

31

Needham DM Scales DC Laupacis A Pronovost PJ . A systematic review of the Charlson comorbidity index using Canadian administrative databases: a perspective on risk adjustment in critical care research. J Crit Care (2005) 20(1):12–9.10.1016/j.jcrc.2004.09.007

32

Chinese Hospital Association. ICD-9-CM English-Chinese Dictionary. Taipei, Taiwan: Chinese Hospital Association Press (2000).

33

Huang HL Ho SY Li CH Chu FY Ciou LP Lee HC et al Bronchial asthma is associated with increased risk of chronic kidney disease. BMC Pulm Med (2014) 14:80.10.1186/1471-2466-14-80

34

Tzeng NS Hsu YH Ho SY Kuo YC Lee HC Yin YJ et al Is schizophrenia associated with an increased risk of chronic kidney disease? A nationwide matched-cohort study. BMJ Open (2015) 5(1):e006777.10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006777

35

Tang YJ Ho SY Chu FY Chen HA Yin YJ Lee HC et al Is zolpidem associated with increased risk of fractures in the elderly with sleep disorders? A nationwide case cross-over study in Taiwan. PLoS One (2015) 10(12):e0146030.10.1371/journal.pone.0146030

36

Yang CW Tzeng NS Yin YJ Li CH Chen HA Chiu SH et al Angiotensin receptor blockers decrease the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events in patients with end-stage renal disease on maintenance dialysis: a nationwide matched-cohort study. PLoS One (2015) 10(10):e0140633.10.1371/journal.pone.0140633

37

Tzeng NS Chung CH Yeh CB Huang RY Yuh DY Huang SY et al Are chronic periodontitis and gingivitis associated with dementia? A nationwide, retrospective, matched-cohort study in Taiwan. Neuroepidemiology (2016) 47(2):82–93.10.1159/000449166

38

Tzeng NS Chang HA Chung CH Lin FH Yeh CB Huang SY et al Risk of psychiatric disorders in Guillain-Barre syndrome: a nationwide, population-based, cohort study. J Neurol Sci (2017) 381:88–94.10.1016/j.jns.2017.08.022

39

Tzeng NS Chung CH Lin FH Huang CF Yeh CB Huang SY et al Magnesium oxide use and reduced risk of dementia: a retrospective, nationwide cohort study in Taiwan. Curr Med Res Opin (2017) 34(1):163–9.10.1080/03007995.2017.1385449

40

Tzeng NS Chung CH Lin FH Yeh CB Huang SY Lu RB et al Headaches and risk of dementia. Am J Med Sci (2017) 353(3):197–206.10.1016/j.amjms.2016.12.014

41

Chien WC Chung CH Lin FH Chang HA Kao YC Tzeng NS . Is weight control surgery associated with increased risk of newly onset psychiatric disorders? A population-based, matched cohort study in Taiwan. J Med Sci (2017) 37(4):137–49.10.4103/jmedsci.jmedsci_94_16

42

Tzeng NS Chung CH Lin FH Yeh CB Huang SY Lu RB et al Risk of dementia in adults with ADHD: a nationwide, population-based cohort study in Taiwan. J Atten Disord (2017).10.1177/1087054717714057

43

Chang CY Chen WL Liou YF Ke CC Lee HC Huang HL et al Increased risk of major depression in the three years following a femoral neck fracture – a national population-based follow-up study. PLoS One (2014) 9(3):e89867.10.1371/journal.pone.0089867

44

McGrogan A Madle GC Seaman HE de Vries CS . The epidemiology of Guillain-Barré syndrome worldwide. Neuroepidemiology (2009) 32(2):150–63.10.1159/000184748

45

van den Berg B Walgaard C Drenthen J Fokke C Jacobs BC van Doorn PA . Guillain-Barre syndrome: pathogenesis, diagnosis, treatment and prognosis. Nat Rev Neurol (2014) 10(8):469–82.10.1038/nrneurol.2014.121

46

Willison HJ Jacobs BC van Doorn PA . Guillain-Barre syndrome: surveillance and cost of treatment strategies – authors’ reply. Lancet (2017) 389(10066):253–4.10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30047-8

47

Group SG-BST. Randomised trial of plasma exchange, intravenous immuno-globulin, and combined treatments in Guillain-Barre syndrome. Plasma exchange. Lancet (1997) 349(9047):225–30.10.1016/S0140-6736(96)09095-2

48

van den Berg B Bunschoten C van Doorn PA Jacobs BC . Mortality in Guillain-Barre syndrome. Neurology (2013) 80(18):1650–4.10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182904fcc

49

Wong AHY Umapathi T Shahrizaila N Chan YC Kokubun N Fong MK et al The value of comparing mortality of Guillain-Barré syndrome across different regions. J Neurol Sci (2014) 344(1–2):60–2.10.1016/j.jns.2014.06.021

50

Marzona I Baviera M Vannini T Tettamanti M Cortesi L Riva E et al Risk of dementia and death in patients with atrial fibrillation: a competing risk analysis of a population-based cohort. Int J Cardiol (2016) 220:440–4.10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.06.235

51

Blanche P Proust-Lima C Loubere L Berr C Dartigues JF Jacqmin-Gadda H . Quantifying and comparing dynamic predictive accuracy of joint models for longitudinal marker and time-to-event in presence of censoring and competing risks. Biometrics (2015) 71(1):102–13.10.1111/biom.12232

52

Billeci L Tonacci A Tartarisco G Ruta L Pioggia G Gangemi S . Association between atopic dermatitis and autism spectrum disorders: a systematic review. Am J Clin Dermatol (2015) 16(5):371–88.10.1007/s40257-015-0145-5

53

Lee CY Chen MH Jeng MJ Hsu JW Tsai SJ Bai YM et al Longitudinal association between early atopic dermatitis and subsequent attention-deficit or autistic disorder: a population-based case-control study. Medicine (2016) 95(39):e5005.10.1097/MD.0000000000005005

54

Liao TC Lien YT Wang S Huang SL Chen CY . Comorbidity of atopic disorders with autism spectrum disorder and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Pediatr (2016) 171:248–55.10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.12.063

55

Strom MA Fishbein AB Paller AS Silverberg JI . Association between atopic dermatitis and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in U.S. children and adults. Br J Dermatol (2016) 175(5):920–9.10.1111/bjd.14697

56

Hammer-Helmich L Linneberg A Obel C Thomsen SF Tang Mollehave L Glumer C . Mental health associations with eczema, asthma and hay fever in children: a cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open (2016) 6(10):e012637.10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012637

57

Timonen M Jokelainen J Hakko H Silvennoinen-Kassinen S Meyer-Rochow VB Herva A et al Atopy and depression: results from the Northern Finland 1966 Birth Cohort Study. Mol Psychiatry (2003) 8(8):738–44.10.1038/sj.mp.4001274

58

Jonsdottir U Lang JE . How does autism spectrum disorder affect the risk and severity of childhood asthma?Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol (2017) 118(5):570–6.10.1016/j.anai.2017.02.020

59

Heck S Al-Shobash S Rapp D Le DD Omlor A Bekhit A et al High probability of comorbidities in bronchial asthma in Germany. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med (2017) 27(1):28.10.1038/s41533-017-0026-x

60

To T Ryckman K Zhu J Williams D Feldman LY Larsen K et al Mental health services claims and adult onset asthma in Ontario, Canada. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract (2017) 5(5):1388–93.e3.10.1016/j.jaip.2017.02.016

61

Miyazaki C Koyama M Ota E Swa T Mlunde LB Amiya RM et al Allergic diseases in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry (2017) 17(1):120.10.1186/s12888-017-1281-7

62

Schans JV Cicek R de Vries TW Hak E Hoekstra PJ . Association of atopic diseases and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Neurosci Biobehav Rev (2017) 74(Pt A):139–48.10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.01.011

63

Silverberg JI . Selected comorbidities of atopic dermatitis: atopy, neuropsychiatric, and musculoskeletal disorders. Clin Dermatol (2017) 35(4):360–6.10.1016/j.clindermatol.2017.03.008

64

Amritwar AU Lowry CA Brenner LA Hoisington AJ Hamilton R Stiller JW et al Mental health in allergic rhinitis: depression and suicidal behavior. Curr Treat Options Allergy (2017) 4(1):71–97.10.1007/s40521-017-0110-z

65

Singer AB Burstyn I Thygesen M Mortensen PB Fallin MD Schendel DE . Parental exposures to occupational asthmagens and risk of autism spectrum disorder in a Danish population-based case-control study. Environ Health (2017) 16(1):31.10.1186/s12940-017-0230-8

66

Sperr M Kundi M Tursic V Bristela M Moritz A Andrukhov O et al Prevalence of comorbidities in periodontitis patients compared to the general Austrian population. J Periodontol (2017) 89:1–13.10.1902/jop.2017.170333

67

Brietzke E Cerqueira RO Mansur RB McIntyre RS . Gluten related illnesses and severe mental disorders: a comprehensive review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev (2018) 84:368–75.10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.08.009

68

Longinetti E Mariosa D Larsson H Ye W Ingre C Almqvist C et al Neurodegenerative and psychiatric diseases among families with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurology (2017) 89(6):578–85.10.1212/WNL.0000000000004179

69

Pompili M Innamorati M Forte A Erbuto D Lamis DA Narcisi A et al Psychiatric comorbidity and suicidal ideation in psoriasis, melanoma and allergic disorders. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract (2017) 21(3):209–14.10.1080/13651501.2017.1301482

70

Aberle D Wu SE Oklu R Erinjeri J Deipolyi AR . Association between allergies and psychiatric disorders in patients undergoing invasive procedures. Psychosomatics (2017) 58(5):490–5.10.1016/j.psym.2017.03.015

71

Weiss EM Singewald E Baldus C Hofer E Marksteiner J Nasrouei S et al Differences in psychological and somatic symptom cluster score profiles between subjects with idiopathic environmental intolerance, major depression and schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res (2017) 249:187–94.10.1016/j.psychres.2016.12.057

72

Larsen JB Iversen VC Reitan SK . Association of psychosis, affective disorders and diseases affecting the immune system. Nord J Psychiatry (2017) 72:145–9.10.1080/08039488.2017.1402952

73

Castillo EF Zheng H Yang XO . Orchestration of epithelial-derived cytokines and innate immune cells in allergic airway inflammation. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev (2017) 39:19–25.10.1016/j.cytogfr.2017.11.004

74

Kohler CA Freitas TH Stubbs B Maes M Solmi M Veronese N et al Peripheral alterations in cytokine and chemokine levels after antidepressant drug treatment for major depressive disorder: systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol Neurobiol (2017).10.1007/s12035-017-0632-1

75

Rosenblat JD McIntyre RS . Bipolar disorder and immune dysfunction: epidemiological findings, proposed pathophysiology and clinical implications. Brain Sci (2017) 7(11):E144.10.3390/brainsci7110144

76

D’Aiuto F Graziani F Tete S Gabriele M Tonetti MS . Periodontitis: from local infection to systemic diseases. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol (2005) 18(3 Suppl):1–11.

77

Farhad SZ Amini S Khalilian A Barekatain M Mafi M Barekatain M et al The effect of chronic periodontitis on serum levels of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in Alzheimer disease. Dent Res J (Isfahan) (2014) 11(5):549–52.

78

Holmes C El-Okl M Williams AL Cunningham C Wilcockson D Perry VH . Systemic infection, interleukin 1beta, and cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry (2003) 74(6):788–9.10.1136/jnnp.74.6.788

79

Raevuori A Lukkariniemi L Suokas JT Gissler M Suvisaari JM Haukka J . Increased use of antimicrobial medication in bulimia nervosa and binge-eating disorder prior to the eating disorder treatment. Int J Eat Disord (2016) 49(6):542–52.10.1002/eat.22497

80

Succurro E Segura-Garcia C Ruffo M Caroleo M Rania M Aloi M et al Obese patients with a binge eating disorder have an unfavorable metabolic and inflammatory profile. Medicine (2015) 94(52):e2098.10.1097/MD.0000000000002098

81

Troester N Palfner M Schmidberger E Olschewski H Avian A . Sleep related breathing disorders and inflammation – the missing link? A Cohort study evaluating the interaction of inflammation and sleep related breathing disorders and effects of treatment. PLoS One (2015) 10(9):e0137594.10.1371/journal.pone.0137594

82

Irwin MR Olmstead R Breen EC Witarama T Carrillo C Sadeghi N et al Cognitive behavioral therapy and tai chi reverse cellular and genomic markers of inflammation in late-life insomnia: a randomized controlled trial. Biol Psychiatry (2015) 78(10):721–9.10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.01.010

83

Irwin MR Opp MR . Sleep health: reciprocal regulation of sleep and innate immunity. Neuropsychopharmacology (2017) 42(1):129–55.10.1038/npp.2016.148

84

Yin H Xu G Tian H Yang G Wardenaar KJ Schoevers RA . The prevalence, age-of-onset and the correlates of DSM-IV psychiatric disorders in the Tianjin Mental Health Survey (TJMHS). Psychol Med (2017) 48(3):473–87.10.1017/S0033291717001878

85

Cheng CL Chien HC Lee CH Lin SJ Yang YH . Validity of in-hospital mortality data among patients with acute myocardial infarction or stroke in national health insurance research database in Taiwan. Int J Cardiol (2015) 201:96–101.10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.07.075

86

Lin CC Lai MS Syu CY Chang SC Tseng FY . Accuracy of diabetes diagnosis in health insurance claims data in Taiwan. J Formos Med Assoc (2005) 104(3):157–63.

87

Liang JA Sun LM Muo CH Sung FC Chang SN Kao CH . The analysis of depression and subsequent cancer risk in Taiwan. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev (2011) 20(3):473–5.10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-1280

88

Li-Ting C Chung-Ho C Yi-Hsin Y Pei-Shan H . The development and validation of oral cancer staging using administrative health data. BMC Cancer (2014) 14:380.10.1186/1471-2407-14-380

89

Yang CC Chen PC Hsu CW Chang SL Lee CC . Validity of the age-adjusted charlson comorbidity index on clinical outcomes for patients with nasopharyngeal cancer post radiation treatment: a 5-year nationwide cohort study. PLoS One (2015) 10(1):e0117323.10.1371/journal.pone.0117323

90

Cheng CL Lee CH Chen PS Li YH Lin SJ Yang YH . Validation of acute myocardial infarction cases in the national health insurance research database in taiwan. J Epidemiol (2014) 24(6):500–7.10.2188/jea.JE20140076

91

Hsieh CY Chen CH Li CY Lai ML . Validating the diagnosis of acute ischemic stroke in a national health insurance claims database. J Formos Med Assoc (2015) 114(3):254–9.10.1016/j.jfma.2013.09.009

92

Chou IC Lin HC Lin CC Sung FC Kao CH . Tourette syndrome and risk of depression: a population-based cohort study in Taiwan. J Dev Behav Pediatr (2013) 34(3):181–5.10.1097/DBP.0b013e3182829f2b

93

Cheng CL Kao YH Lin SJ Lee CH Lai ML . Validation of the national health insurance research database with ischemic stroke cases in Taiwan. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf (2011) 20(3):236–42.10.1002/pds.2087

94

Sung SF Hsieh CY Lin HJ Chen YW Yang YH Li CY . Validation of algorithms to identify stroke risk factors in patients with acute ischemic stroke, transient ischemic attack, or intracerebral hemorrhage in an administrative claims database. Int J Cardiol (2016) 215:277–82.10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.04.069

95

Tseng HP Lin FJ Chen PT Mou CH Lee SP Chang CY et al Derivation and validation of a discharge disposition predicting model after acute stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis (2015) 24(6):1179–86.10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2015.01.010

96

Yang H Chen YH Hsieh TF Chuang SY Wu MJ . Prediction of mortality in incident hemodialysis patients: a validation and comparison of CHADS2, CHA2DS2, and CCI scores. PLoS One (2016) 11(5):e0154627.10.1371/journal.pone.0154627

97

Wu CS Lai MS Gau SS Wang SC Tsai HJ . Concordance between patient self-reports and claims data on clinical diagnoses, medication use, and health system utilization in Taiwan. PLoS One (2014) 9(12):e112257.10.1371/journal.pone.0112257

98

Yu ST Chang HY Lin MC Lin YH . Agreement between self-reported and health insurance claims on utilization of health care: a population study. J Clin Epidemiol (2009) 62(12):1316–22.10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.01.016

Summary

Keywords

bronchial asthma, allergic rhinitis, atopic dermatitis, psychiatric disorders, risk factors, cohort study, Taiwan National Health Insurance Program, National Health Insurance Research Database

Citation

Tzeng N-S, Chang H-A, Chung C-H, Kao Y-C, Chang C-C, Yeh H-W, Chiang W-S, Chou Y-C, Chang S-Y and Chien W-C (2018) Increased Risk of Psychiatric Disorders in Allergic Diseases: A Nationwide, Population-Based, Cohort Study. Front. Psychiatry 9:133. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00133

Received

04 December 2017

Accepted

28 March 2018

Published

24 April 2018

Volume

9 - 2018

Edited by

Drozdstoy Stoyanov Stoyanov, Plovdiv Medical University, Bulgaria

Reviewed by

Massimiliano Aragona, Crossing Dialogues Association, Italy; Marianna Atanassova Murdjeva, Plovdiv Medical University, Bulgaria

Updates

Copyright

© 2018 Tzeng, Chang, Chung, Kao, Chang, Yeh, Chiang, Chou, Chang and Chien.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Wu-Chien Chien, chienwu@ndmctsgh.edu.tw

Specialty section: This article was submitted to Psychopathology, a section of the journal Frontiers in Psychiatry

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.