- 1College of Arts and Sciences, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, United States

- 2Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust, Oxford, United Kingdom

- 3Department of Forensic Psychiatry, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom

Aims: We aimed to review prison healthcare expenditure internationally.

Objectives: To systematically review healthcare spending on prisoners worldwide, examine comparability between countries, and develop guidelines to improve reporting.

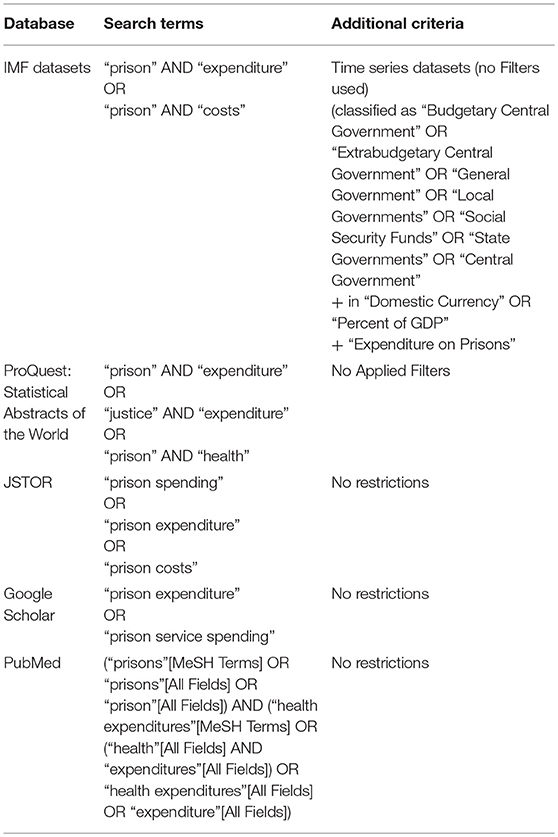

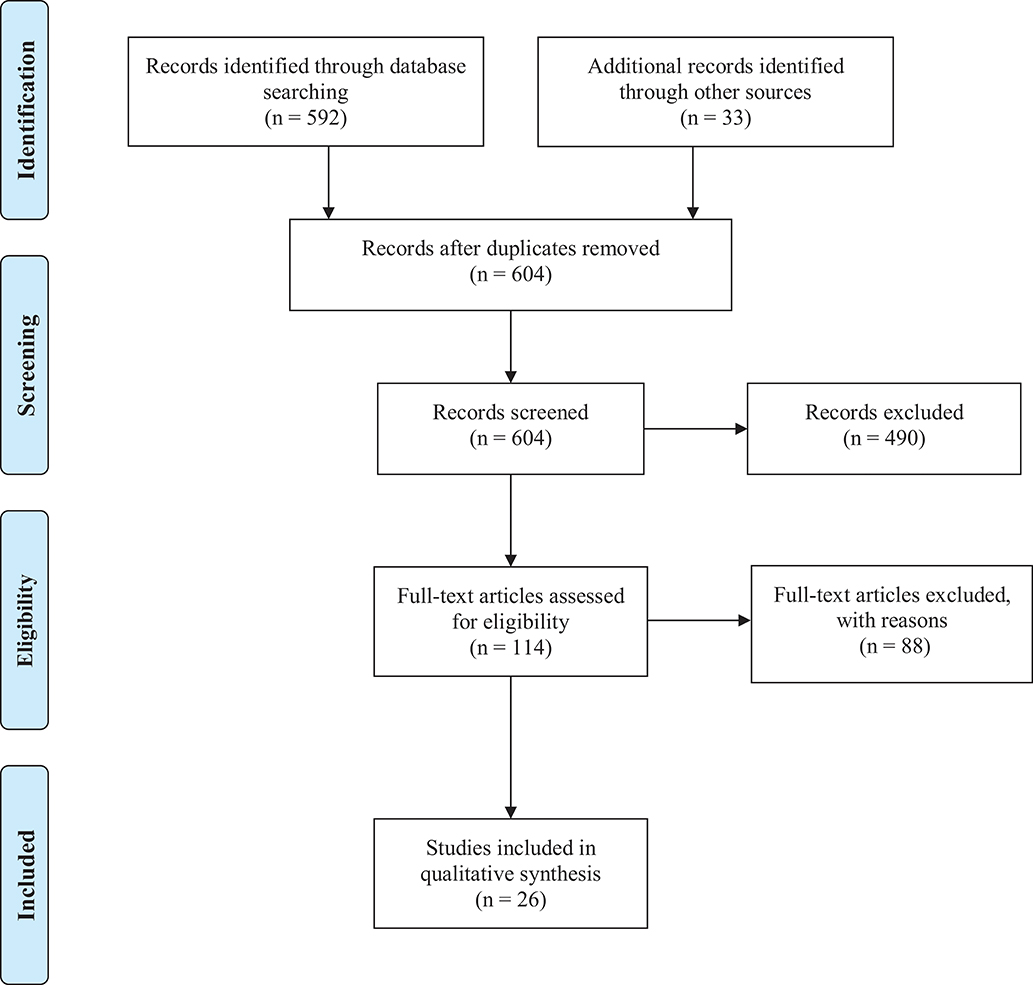

Methods: Five bibliographic indexes (International Monetary Fund, ProQuest: Statistical Abstracts of the World, PubMed, Google Scholar, and JSTOR) were searched for the costs of prison and prison healthcare, supplemented with country-specific searches for the 20 countries with the highest prison populations. Information on overall healthcare costs, their breakdown by categories, and their proportion to overall prison expenditure was extracted. PRISMA guidelines were followed.

Results: Prison healthcare expenditure data was identified for 10 countries, and overall operating costs were reported for 12 countries. The most commonly reported healthcare cost was for primary medical care. Healthcare costs reporting varied widely, and few countries were comparable. We developed a set of guidelines for consistent and transparent reporting of healthcare costs.

Conclusions: Few countries report the costs of healthcare services in prison. When reported, there is a lack of clarity and consistency as to what is included. Using the proposed reporting guidelines would enable national trends and international comparisons to be investigated, and any recommended benchmarks to be monitored.

Introduction

Healthcare in prison varies widely across countries, and differences in service provision contribute to morbidity and mortality outcomes inside custody (1) and on release (2). Many studies have examined disease prevalence rates, and prevention, care, and treatment in prison (3, 4), but the current evidence base lacks information on the costs of healthcare services. Combined with information on the prevalence of healthcare problems, international comparisons of prison health expenditure could better inform decisions on the levels of appropriate funding, enable benchmarks to be monitored, and allow for planning of service provision.

Information on the costs of operating prisons have been published since the 1950s (5), including a 2004 report of international costs (6). However, no review of prison healthcare costs across countries currently exists. Government and other reports of healthcare costs in prisons have been published, but it is not clear in reporting what particular services are included, which examine variously “medical care” (7), “prison hospitals” (8), or “prisoner health” (9). Furthermore, what is included within these categories is not clear. Scotland, for instance, lists mental health and dental care as prison healthcare expenditures (10), while Australia provides only a single overarching figure for prisoner health (9).

In this systematic review, we have aimed to provide an international overview of the annual costs of prisoner healthcare, what healthcare services are included in the identified reports, and calculate the proportion of overall prison operating budgets allocated to health. In addition, we develop and propose reporting guidelines.

Methods

Search Strategy

We searched IMF, ProQuest: Statistical Abstracts of the World, Google Scholar, JSTOR, and PubMed databases. We performed non-country specific searches, with a combination of keywords: “prison” OR “justice,” AND “expenditure,” “spending,” OR “costs” (Table 1 for details). Then, additional targeted searches on Google Web and government databases (e.g., Statistics Canada) were conducted for the 20 countries with the largest prison population (11) and countries included in a previous review of recidivism rates (12), with a combination of keywords: country name AND “prison healthcare cost,” country name AND “ministry of justice,” country name AND “prison” AND “expenditure” OR “service.” No language or publication date restrictions were set, and the most recent and relevant cost report was identified. When necessary, correctional services were contacted to clarify data. A review protocol [CRD42018102534] was submitted and published on the PROSPERO register of systematic review during data extraction.

Per-prisoner estimates for each country were calculated as follows:

1) Identifying total expenditures from the included reports (excluding the US and Germany, which reported per-prisoner expenditure based on all state prison populations)

2) Calculation of per-prisoner cost (using the prison population from World Prison Brief statistics) (13). If the prison population was not available for the same year as the cost report, the following year's prison population was used;

3) Conversion of per-prisoner cost estimate into inflation-adjusted 2016 International US dollars (using “CCEMG-EPPI-Center Cost Converter” external database). Stage 1 and 2 computational values (GDP deflator and PPP) of the validated conversion tool were obtained from IMF World Economic Outlook Database. Costs were first adjusted for inflation within original economy [using GDP deflator values], and then to purchasing power parity/price level between countries (14).

The cost conversions in this review may be limited by using purchasing power parities for Gross Domestic Product, which cover a broader array of goods and services than context-specific purchasing power parities (e.g., healthcare or technology purchasing power parities). However, based on the heterogeneity of costs and inventories reported by countries, purchasing power parities for Gross Domestic Product appeared to be more fitting for this review than context-specific conversion factors (14).

Study Design

Geographical

Official national and regional data were extracted from search engines. Unofficial regional data was found for one country (15), but was not included.

Data Items

The measurements and descriptions of economic costs were limited to direct prison operating costs and/or healthcare costs. Studies reporting indirect costs to prisoners (e.g., productivity loss) were excluded. The most recent information was used. Most countries presented financial accounts for the 2015–16 or 2016–17 periods, so all cost outcomes were indexed to 2016 International US dollars.

Data Sources

Financial reports on prisons/correctional services solely were included. Datasets which did not specify relevant outcome measurements (i.e., prison operations, healthcare) or the population (i.e., whole country, adult prisoners) were excluded. Expenditure reporting on police, courts, or other services affiliated with Ministries of Justice was excluded, as were assessments of prisoner health services separate from expenditure data (16). Governments typically separate prison expenditures into capital and operating costs. Capital costs refer to fixed, one-time investments on buildings, equipment, or land. Operating costs of prisons refer to day-to-day running costs, accommodation-related costs, and staff costs (17). Ideally, prison healthcare broadly refers to the services in place to address health needs and reduce health risks. It can include primary and psychiatric care, and specialized services. Information for two other countries (Greece and Switzerland) were available but not used. They were not from official governmental sources, did not specify constituent elements of costs, and are likely to be underestimates (7, 15). Costs for Sweden did not include infrastructure costs and were also not included (18).

Data Extraction

One of the authors (SS) screened and extracted the data, excluding publications and data points that did not report costs, and determined the remit of the data (e.g., national, regional).

Data Analysis

Meta-analysis was not conducted due to heterogeneity in definition and measurement of cost outcomes.

Subgroup Comparison

We compared healthcare cost descriptions by country to account for differences in categorization of expenses. Descriptions for the most recent period are included. PRISMA guidelines were followed (Table S1, Figure 1). SS and SF assessed primary outcome measures of healthcare service costs and summary descriptions.

Results

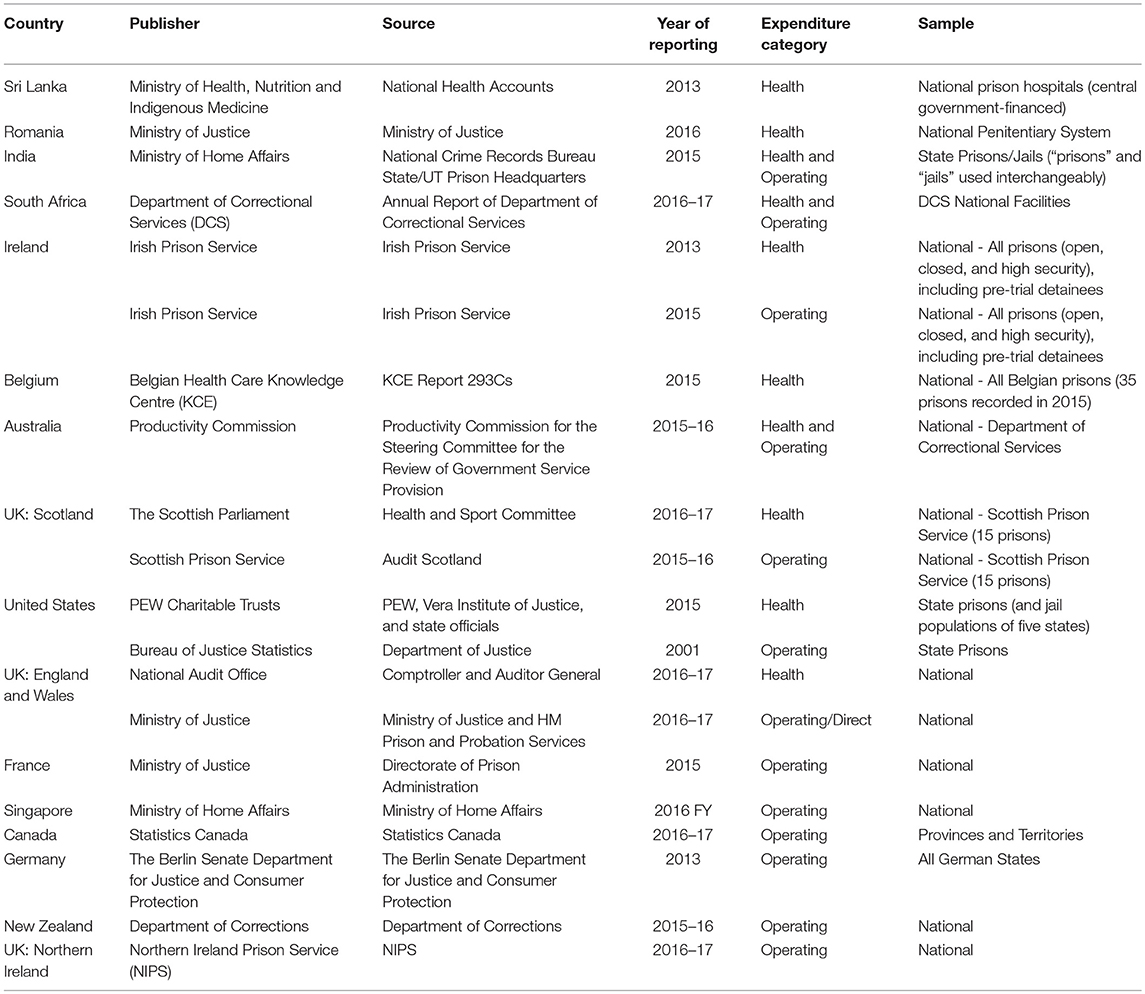

We identified official country reports of prison healthcare costs for 10 countries (Table 2).

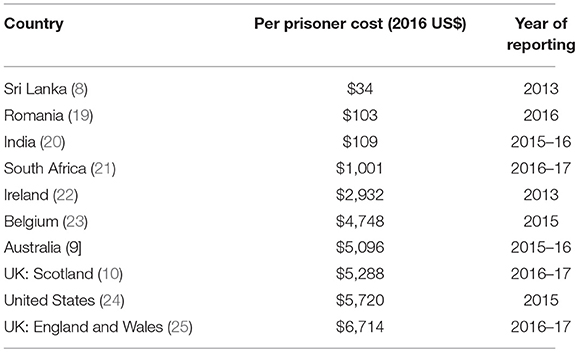

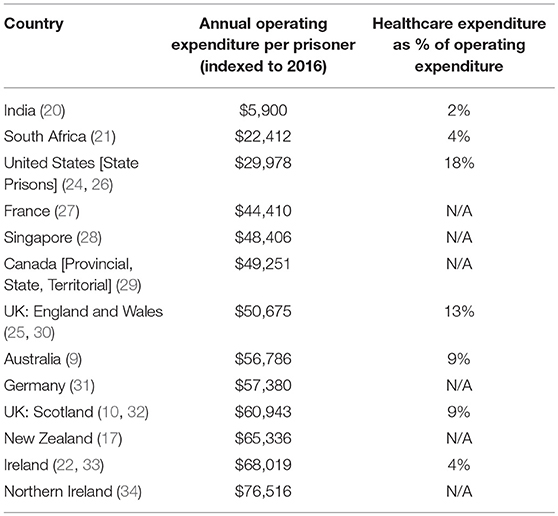

Annual healthcare expenditures per prisoner ranged from approximately $34 per year to $6,714 per year (Table 3). There was also wide variation in the percentage of operating costs attributable to healthcare, ranging from 2 to 18% (Table 4).

Table 4. Annual overall prison operating costs and healthcare expenditure as percentage of operating expenditures.

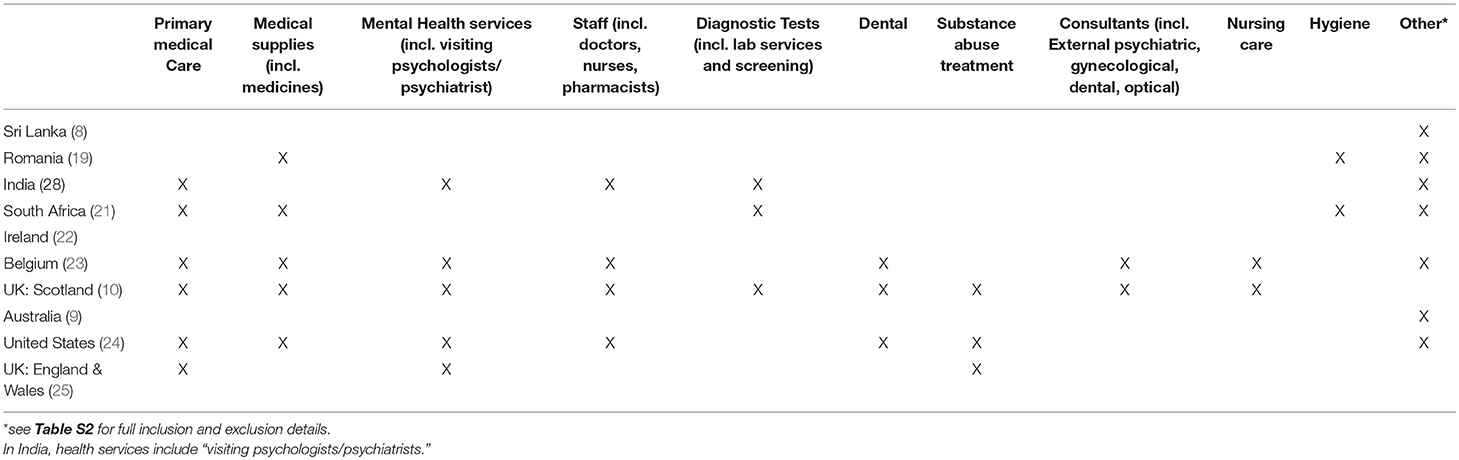

Seven countries described the constituent elements of healthcare spending, but these were not comparable (Table 5). The most commonly reported cost outcome was “primary medical care,” followed together by “medical supplies” (mostly medication) and “mental health services.” In the three countries (Sri Lanka, Ireland, Australia) that did not clarify expenditures, categorization varied from “curative care” (8) to “medical care” (22) to “prisoner health costs” (9). Most countries did not clarify how expenditure was allocated across services.

Discussion

In this systematic review, we identified 10 countries that have reported healthcare costs in prisons. In addition, we were able to calculate the proportion of overall operating expenditure allocated to healthcare in 7 countries. Among the 20 countries with the highest prison populations (11), only 4 reported operating and healthcare expenditures on prisoners (20, 21, 24, 25). There were large variations in how healthcare costs were defined across countries, and consistency and transparency is required to enable international comparison. We have sought to address this by developing guidelines for future reporting.

One other finding was that only two countries reported spending more than 10% of their overall prison operating budgets on prison health (24, 25). Additionally, we did not find any clear links between overall spending and the proportion on healthcare. Notably, Ireland had the highest overall operating expenditure per prisoner among the countries reporting healthcare costs, but only 4% of its budget was allocated toward healthcare, which put it among the countries with the lowest proportion (22, 33).

Seven of the 10 countries that reported on healthcare expenditure provided specific detail on the services provided. The breakdown of these services varied between countries. It was not clear in some cases whether staff expenses included salaries of allied health professionals such as pharmacists, technicians, dentists, and visiting doctors (23), or whether “medical supplies” included medicines and medical equipment (21). Dental services lacked sufficient detail (10, 24), and mental health services were defined inconsistently across countries, with some countries integrating addiction care into mental health services (10, 24, 25), but another not (20).

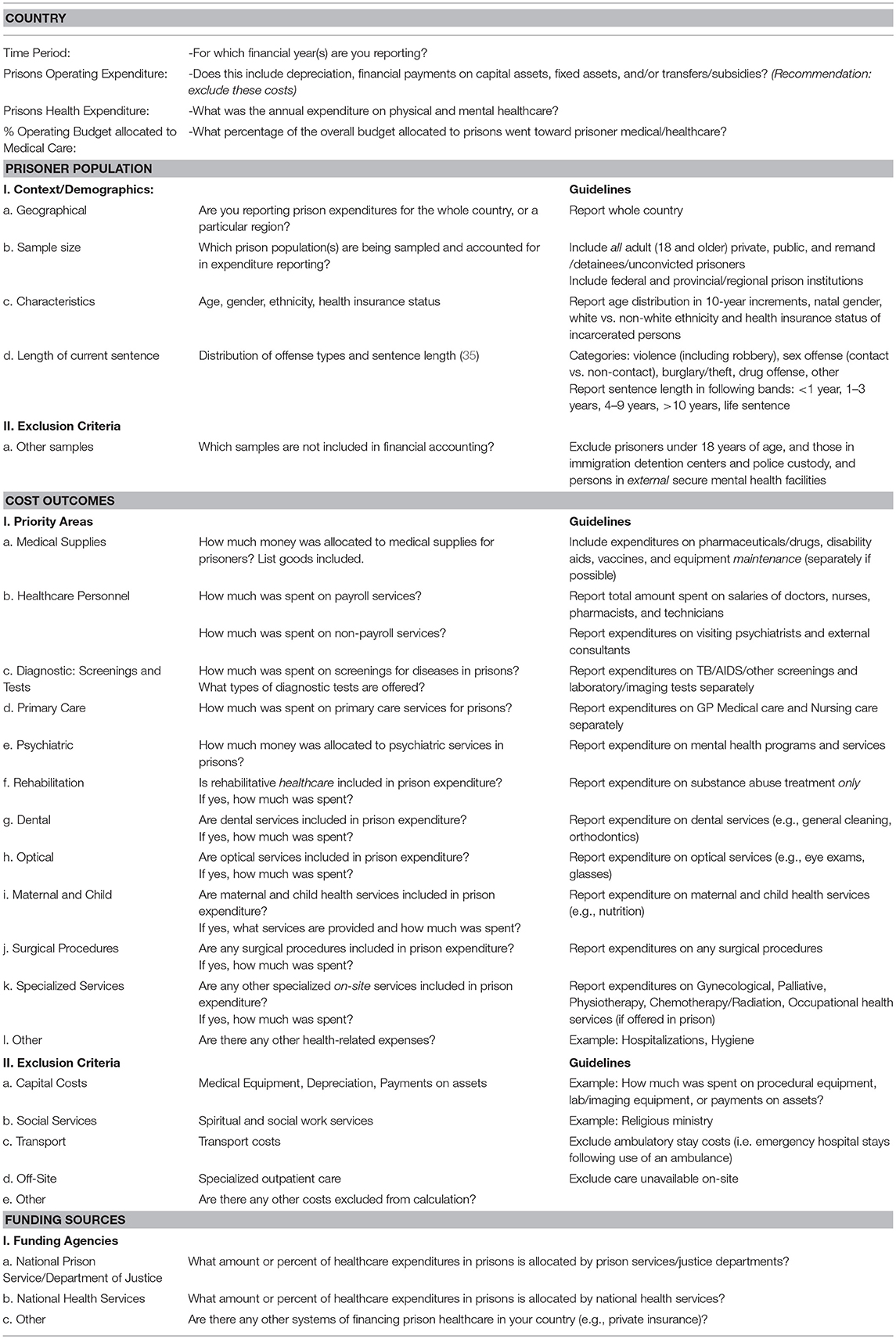

One main implication of these findings is that international comparisons of healthcare expenditures on prisoners are currently not possible due to lack of consistency and transparency in reporting. To address this, we have developed a brief checklist covering definitions, inclusion, and exclusion criteria, and sources of funding that contribute to prison healthcare (such as national health services or ministry of justice) (Table 6). This checklist follows the structure of existing national financial audits, and is based on examples of good practice based on the current review, those categories that appear to be most consistently reported, and previous context-specific reporting guidelines (12, 15, 24, 36). The current proposed checklist would enable international comparison of overall healthcare expenditure in prisons, and provide country specific breakdowns as to how resources are allocated. Consistent international reporting would assist in monitoring whether countries meet basic standards for prisoner health, and allow for examination of links between adverse health outcomes in prisoners and variation in services provided. It would also help to develop and monitor recommended levels of appropriate funding. Different governments are likely to have competing additional priorities of healthcare need (20, 21), which will be reflected in how resources are spent and be reported in this checklist. Systematic reporting of expenditure may lead to improved health outcomes for prisoners by, for example, targeting specific areas of need in future service provision. They could also lead to increased efficiency and a greater focus on prevention. We recommend that prison services include the checklist information in annual accounts, where expenditures are often separated by service category and funding source (37). We have sought to streamline these guidelines to assist in feasibility of completion, standardization, and integration into national financial audits.

Limitations

Using percentage allocations of overall operating expenditure allocated to healthcare does not necessarily allow for cross-country comparison. For example, Australia and Scotland made similar allocations, of ~9% (9, 10). However, due to the different descriptions of services provided, it is unclear whether the two countries provide equivalent healthcare services for prisoners. Some country estimates were based on limited data. For example, calculations for the US and Canada were limited by exclusion of federal prisons, constituting 19.9% of Canadian adult institutions and 7.9% of combined American state and federal institutions (13). There were variations in American prisons with regard to sources of funding, which may have underestimated costs in some states. For example, inpatient hospitalization costs were being met by insurance companies in some cases, but borne by the prison directly in others. Similarly, in some states, community mental health services covered some of the cost of prisoner treatment (24).

There are additional sources of information on healthcare services provided in prisons which we have not included in this review, as they do not provide detail on expenditure (16). Future work may look at such reviews of prison healthcare (for non-financial purposes) to provide a more detailed assessment of what services are provided, in conjunction with examining financial reporting.

Author Contributions

SF and SS conceived and designed the experiments. SF and SS performed the experiments. SS analyzed the data. SF, SS, and RC wrote the paper. SF supervised the project.

Funding

SF is funded by the Wellcome Trust (202836/Z/16/Z) and RC is supported by the Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00716/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Raimer BG, Stobo JD. Health care delivery in the Texas prison system: the role of academic medicine. JAMA (2004) 292:485–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.4.485

2. Young JT, Arnold-Reed D, Preen D, Bulsara M, Lennox N, Kinner SA. Early primary care physician contact and health service utilization in a large sample of recently released ex-prisoners in Australia: prospective cohort study. BMJ Open (2015) 5:1–11. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008021

3. Fazel S, Baillargeon J. The health of prisoners. Lancet (2011) 377:956–65. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61053-7

4. Fazel S, Ramesh T, Hawton K. Suicide in prisons: an international study of prevalence and contributory factors. Lancet Psychiatr. (2017) 4:946–52. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30430-3

5. Alexander ME. Do our prisons cost too much? Ann Am Acad Polit Soc Sci. (1954) 293:35–41. doi: 10.1177/000271625429300106

6. Farrell G, Clark K. What Does the World Spend on Criminal Justice? Helsinki European United Nations Institute for Crime Prevention and Control (2004).

7. Lambropoulou E. Greek Prisons' Expenditures. Athens: Institute for Regulatory Policy Research (2015). Available online at: http://www.inerp.gr/en/blog/184-greek-prisons-expenditures.html (Accessed May 24, 2018).

8. Sri Lanka National Health Accounts 2013. Colombo: Ministry of Health, Health Economics Cell. (2016). Avaialble online at: http://www.health.gov.lk/enWeb/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=621&Itemid=533 (Accessed May 24, 2018).

9. Report on Government Services Volume C: Justice 2017. Canberra: Productivity Commission for the Steering Committee for the Review of Government Service Provision (2017). Avaialble online at: https://www.pc.gov.au/research/ongoing/report-on-government-services/2017/justice/rogs-2017-volumec.pdf (Accessed May 21, 2018).

10. Healthcare in Prisons. Scottish Parliament: Health and Sport Committee (2017). Available online at: https://sp-bpr-en-prod-cdnep.azureedge.net/published/HS/2017/5/10/Healthcare-in-Prisons/5threport.pdf (Accessed June 4, 2018).

11. Institute for Criminal Policy Research. World Prison Brief. Highest to Lowest - Prison Population Total. London: Kings College (2017). Available online at: http://www.prisonstudies.org/highest-to-lowest/prison-population-total?field_region_taxonomy_tid=All

12. Fazel S, Wolf A. A systematic review of criminal recidivism rates worldwide: current difficulties and recommendations for best practice. PLoS ONE (2015) 10:e0130390. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0130390

13. Institute for Criminal Policy Research. World Prison Brief Data Prison population trend [by country]. London: Kings College. Available online at: http://www.prisonstudies.org/world-prison-brief-data

14. Shemilt I, Thomas J, Morciano M. A web-based tool for adjusting costs to a specific target currency and price year. Evid Policy (2010) 6:51–9. doi: 10.1332/174426410X482999

15. Moschetti K, Zabrodina V, Wangmo T, Holly A, Wasserfallen J-B, Elger BS, et al. The determinants of individual health care expenditures in prison: evidence from Switzerland. BMC Health Serv Res. (2018) 18:160. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-2962-8

16. Irish Prison Service. Health Care Standards. Dublin: Irish Prison Service (2011). Available online at: http://www.irishprisons.ie/wp-content/uploads/documents/hc_standards_2011.pdf (Accessed June 6, 2018).

17. Department of Corrections. Annual Financial Statements, Annual Report Part C. Wellington: Department of Corrections (2016). Available online at: http://www.corrections.govt.nz/__data/assets/pdf_file/0006/857742/Annual_Report_201516_Part_C.pdf (Accessed June 7, 2018).

18. Swedish Prison and Probation Service. Annual Budget 2017. Norrokoping: Swedish Prison and Probation Service (2017). Available online at: https://www.kriminalvarden.se/globalassets/publikationer/ekonomi/kriminalvardens-arsredovisning-2017.pdf (Accessed July 18, 2018).

19. Dragomir M, Ignat L. Budget of the National Administration of Penitentiaries. National Penitentiary Administration (2016). Available online at: http://anp.gov.ro/wp-content/uploads/rapoarte/buget%202016%20final.pdf (Accessed July 2, 2018).

20. National Crime Records Bureau. Prison Statistics 2015. New Delhi: Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India (2016). Available online at: http://ncrb.gov.in/StatPublications/PSI/Prison2015/Full/PSI-2015-_18-11-2016.pdf (Accessed June 4, 2018).

21. Department of Correctional Services. Annual Report 2016/17. Pretoria: Correctional Services, Republic of South Africa (2017). Available online at: http://www.dcs.gov.za/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/DCS-AR-2016_17-.pdf (Accessed June 5, 2018).

22. Irish Prison Service. Public Spending Code Quality Assurance Report for 2013. Dublin: Irish Prison Service, Department of Justice Equality (2014). 16 Available online at: http://www.irishprisons.ie/images/pdf/pscr_2013.pdf (Accessed June 6, 2018).

23. Mistiaen P, Dauvrin M, Eyssen M, Roberfroid D, San Miguel L, Vinck I. Health Care in Belgian Prisons: Current Situation Scenarios for the Future. Belgian Health Care Knowledge Center (KCE) (2017): Report 293Cs. Available online at: https://kce.fgov.be/sites/default/files/atoms/files/KCE_293Cs_Prisons_health_care_Synthese_1.pdf (Accessed June 7, 2018).

24. Huh K, Boucher A, McGaffey F, McKillop M, Schiff M. Prison Health Care Costs Quality. Philadelphia, PA: Pew Charitable Trusts (2017). Available online at: http://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/reports/2017/10/prison-health-care-costs-and-quality (Accessed May 16, 2018).

25. Morse A. Mental Health in Prisons. London: National Audit Office, Her Majesty's Prison & Probation Service (2017). Available online at: https://www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Mental-health-in-prisons.pdf (Accessed June 1, 2018).

26. Stephan JJ. State Prison Expenditures, 2001. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics (2004). Available online at: https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/spe01.pdf (Accessed May 16, 2018).

27. Ministry of Justice. Key Figures Prison Administration. France Ministry of Justice, Directorate of Prison Administration (2015). Available online at: http://www.justice.gouv.fr/art_pix/chiffres_cles_2015_UK.pdf(Accessed May 26, 2018)

28. Ministry of Home Affairs. Budget 2016 Revenue and Expenditure Estimates. Singapore Government: Ministry of Home Affairs (2016). Available online at: https://www.singaporebudget.gov.sg/data/budget_2016/download/3%20MHA%202016.pdf MHA 2016.pdf (Accessed May 25, 2018).

29. Statistics Canada. Operating Expenditures for Adult Correctional Services. Ottawa, ON: Statistics Canada (2018). Available online at: http://www5.statcan.gc.ca/cansim/a26?lang=eng&retrLang=eng&id=2510018&&pattern=&stByVal=1&p1=1&p2=31&tabMode=dataTable&csid= (Accessed May 19, 2018).

30. Ministry of Justice. Prison Performance Statistics 2016 to 2017. London: Ministry of Justice (2017). Available online at: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/prison-performance-statistics-2016-to-2017 (Accessed 16 May 2018).

31. Berlin Senate Department for Justice and Consumer Protection. The Prison System in Berlin. Berlin: State Department for Justice and Consumer Protection (2015). https://www.berlin.de/justizvollzug/_assets/senjustv/sonstiges/broschuere-justizvollzug-englisch.pdf (Accessed June 12, 2018).

32. Scottish Prison Service. SPS Annual Report and Accounts 2015-2016. Edinburgh: Scottish Prison Service (2016). Available online at: http://www.irishprisons.ie/wp-content/uploads/documents_pdf/2015_prisonspace_cost-1.pdf (Accessed June 4, 2018).

33. Irish Prison Service. Financial Reports: Cost of Prison Space 2015. Dublin: Irish Prison Service (2018). Available online at: http://www.irishprisons.ie/wp-content/uploads/documents/hc_standards_2011.pdf (Accessed June 6, 2018).

34. Northern Ireland Prison Service. Annual Report and Accounts 2016-17. Belfast: Northern Ireland Prison Service (2017). Available online at: https://www.justice-ni.gov.uk/sites/default/files/publications/justice/northern-ireland-prison-service-annual-report-and-accounts-2016-17.PDF (Accessed June 6, 2018).

35. Singleton N, Meltzer H, Gatward R. Psychiatric Morbidity Among Prisoners: Summary Report. London: Office for National Statistics. (1998).

36. Aebi MF, Tiago MM, Burkhardt C. SPACE I–Council of Europe Annual Penal Statistics: Prison Populations. Survey 2014. Strasbourg: Council of Europe.

37. Marshall T, Simpson S, Stevens A. Health Care in Prisons. Department of Health and the Directorate of Health Care of the Prison Service in England and Wales (1998-99). Available online at: https://www.birmingham.ac.uk/Documents/college-mds/haps/projects/HCNA/11HCNA3D3.pdf

Keywords: prison, custody, detention, costs, expenditure, guidelines, healthcare services

Citation: Sridhar S, Cornish R and Fazel S (2018) The Costs of Healthcare in Prison and Custody: Systematic Review of Current Estimates and Proposed Guidelines for Future Reporting. Front. Psychiatry 9:716. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00716

Received: 08 October 2018; Accepted: 06 December 2018;

Published: 20 December 2018.

Edited by:

Thomas Nilsson, University of Gothenburg, SwedenReviewed by:

Annette Opitz-Welke, Charité Universitätsmedizin Berlin, GermanyPeter Andiné, University of Gothenburg, Sweden

Copyright © 2018 Sridhar, Cornish and Fazel. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Seena Fazel, c2VlbmEuZmF6ZWxAcHN5Y2gub3guYWMudWs=

Shivpriya Sridhar

Shivpriya Sridhar Robert Cornish

Robert Cornish Seena Fazel

Seena Fazel