Abstract

Mounting evidence demonstrates a close relationship between sleep disturbance and mood disorders, including major depression disorder (MDD) and bipolar disorder (BD). According to the classical two-process model of sleep regulation, circadian rhythms driven by the light–dark cycle, and sleep homeostasis modulated by the sleep–wake cycle are disrupted in mood disorders. However, the exact mechanism of interaction between sleep and mood disorders remains unclear. Recent discovery of the glymphatic system and its dynamic fluctuation with sleep provide a plausible explanation. The diurnal variation of the glymphatic circulation is dependent on the astrocytic activity and polarization of water channel protein aquaporin-4 (AQP4). Both animal and human studies have reported suppressed glymphatic transport, abnormal astrocytes, and depolarized AQP4 in mood disorders. In this study, the “glymphatic dysfunction” hypothesis which suggests that the dysfunctional glymphatic pathway serves as a bridge between sleep disturbance and mood disorders is proposed.

Introduction

Mood disorders are a group of complex debilitating psychiatric diseases identified by symptoms centered on markedly disrupted emotions, including major depressive disorder (MDD) and bipolar disorder (BD) (1). Due to their high prevalence, the risk for recurrence and suicide, they remain a serious health concern worldwide (2, 3). However, the exact neurobiological mechanisms underlying mood disorders remain unclear, resulting in unsatisfactory treatment (2, 3).

Sleep disturbance is a common concomitant and prodromal symptom of mood disorders (1, 4, 5). Specifically, both the two processes of sleep regulation—circadian oscillator and sleep pressure—are disrupted in mood disorders (4, 6). On one hand, circadian rhythms are approximately 24-h patterns in physiology and behavior, which are regulated by molecular clocks in the suprachiasmatic nuclei (SCN) of the hypothalamus (7). Mounting evidence suggests that there are abnormalities of the clock genes in mood disorders, such as single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) (8–13), gene expression (14, 15), and gene–gene interactions (8). Excitingly, antidepressants including fluoxetine (16–18), ketamine (19, 20), and agomelatine (21) can reset the circadian clock along with the amelioration of mood symptoms. On the other hand, sleep pressure fluctuates with the sleep–wake cycle (6). Whereas, disturbance of the sleep–wake cycle has often been reported in mood disorders (22–24). Disturbed sleep architecture, especially decreased percentage of stage 3 non-rapid eye movement sleep (NREM III), represents decreased homeostatic drive for sleep (6). Actually, NREM III serves as a deep and recovery sleep, playing a vital role in the operation of the glymphatic system, and clearance of metabolic wastes (25, 26).

The glymphatic system is considered as an effective waste-removal system in the brain, which facilitates the exchange between the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and interstitial fluid (ISF), along with the potentially neurotoxic proteins such as amyloid-β (Aβ) (27), tau protein (28), and α-synuclein (29). Therefore, glymphatic impairment caused by sleep disturbance results in protein aggregation and increased risk for neurological diseases, such as Alzheimer's disease (AD) (30), Parkinson's disease (PD) (31), stroke (32, 33), and idiopathic normal cranial pressure hydrocephalus (iNPH) (34, 35). The water channel protein aquaporin-4 (AQP-4) is highly expressed on astrocytic endfeet and exerts significant influence in glymphatic transport (36). At present, accumulating evidence suggests the presence of abnormal astrocytes (37–43), depolarized AQP-4 (44–46), and dysfunctional glymphatic system (47, 48) in mood disorders. Therefore, we speculated that glymphatic dysfunction serves as an imperative intermediary factor between sleep disturbance and mood disorders.

In this study, we integrated available data from both animal and human studies regarding sleep in mood disorders and highlighted the core role of the glymphatic system. Furthermore, we discussed the glymphatic system dysfunction in mood disorders and identified the potential therapeutic opportunities for mood disorders based on sleep regulation and the glymphatic pathway.

Sleep Disturbance and Mood Disorders

The Model of Sleep Regulation

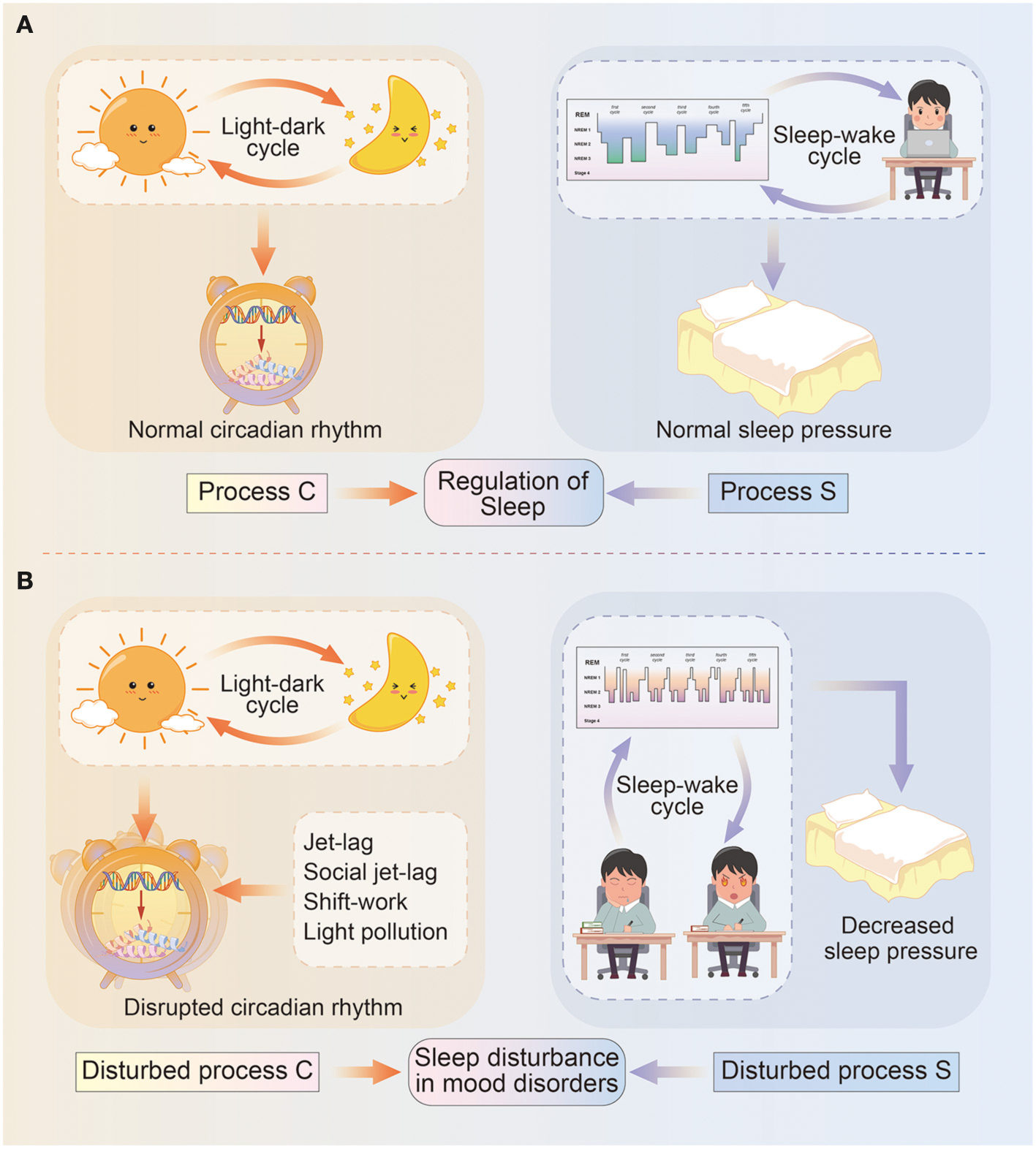

The classical two-process model of sleep regulation was first proposed by Borbély, and it consists of the process controlled by the circadian oscillator (Process C) and the homeostatic drive for the sleep–wake cycle (Process S). The two processes closely interact with each other but are also relatively independent (6) (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Diagram illustrating the two-process model of sleep regulation. (A) In normal circumstances, sleep regulation depends on the interaction between process C and process S. Specifically, process C represents the circadian rhythm driven by light–dark cycles, and circadian genes deliver circadian information via transcriptional–translational feedback loops and control physical and behavioral states. Process S means sleep pressure influenced by sleep–wake cycles, and include sleep architecture and daytime wakefulness. (B) In mood disorders, circadian rhythms (process C) are misaligned with light–dark cycles due to events such as jet-lag, social jet-lag, shift-work, light pollution, and so on; while sleep pressure (process S) is remarkably decreased due to longer sleep onset latency, a higher percentage of REM sleep, daytime sleepiness, or reduced need for sleep.

Circadian rhythms (Process C) are approximately 24-h rhythms in physiology and behavior, which are primarily driven by a hierarchy of cellular pacemakers located in the SCN (7). The most common measurements of the circadian rhythm are core body temperature and endogenous melatonin, other than the chronotype or morningness-eveningness (49). In fact, circadian rhythms are generated by a molecular clock in a network of positive and negative feedback loops. At the core of SCN timekeeping, the heterodimeric transcription factors CLOCK/BMAL1 translated from CLOCK and Brain and muscle ARNT-like 1 (BMAL1) genes, activate the Period (PER1–3) and Cryptochrome (CRY1–2) genes and initiate the circadian cycle. In turn, the dimer complex protein PER/CRY inhibit the activity of the CLOCK/BMAL1 proteins (50), exerting dominant effect in the negative feedback. As a critical complementary loop, the BMAL1 transcription is activated by the retinoic acid-related orphan receptor (ROR) protein at night, and repressed by the nuclear receptors REV-ERB α/β (encoded by NR1D1/2 genes) at daytime (51), respectively. In addition, other clock genes also participate in the regulation of circadian rhythms. The neuronal PAS domain protein 2 (NPAS2) functions similarly to CLOCK, while albumin gene D-site binding protein (DBP) acts cooperatively with CLOCK/BMAL1 (52, 53). The casein kinase I isoform δ/ε (CSNK1D/E) regulates levels of PER by phosphorylation-mediated degradation, and thus inhibits the activity of CLOCK/BMAL1 (54). The basic helix-loop-helix family 40/41 (BHLHE40/41, also known as DEC1/2) suppresses PER gene transcription via competing with CLOCK-BMAL1 for e-box element binding (55). The TIMELESS gene is also conceived required for circadian rhythmicity, however, the exact role in human clockwork is still unclear (56). These circadian genes expression rise and fall in rhythm, contributing to the regulation of 24-h physical and behavioral cycles (15).

Process S, also referred to as the sleep pressure gradually accumulates during wakefulness and declines during sleep (6). Especially, as deep sleep (NREM III) dominates in the early phases of sleep and dwindles with decreasing sleep pressure in the late phases. Conversely, sleep deficit such as sleep deprivation results in a longer and deeper NREM III to achieve recovery (57), implying greater sleep pressure. Therefore, NREM III sleep is considered as a representation of sleep pressure (6). Sleep electroencephalogram (EEG) and actigraphy are effective assessments of sleep pressure to detect sleep architecture.

According to the two-process model, proper alignment of Process C and S is essential for recovery sleep. Otherwise, the daytime sleep fails to fulfill the homeostatic sleep drive, manifesting as lighter and lacking of recovery sleep (NREM III) (58). Moreover, the daytime sleep decreases sleep pressure, causing a negative influence on the more effective nighttime sleep.

Sleep Disturbance in Mood Disorders

Disturbed Circadian Rhythms in Mood Disorders

Disruptions of the circadian rhythms are common in people exposed to jet-lag, social jet-lag, shift-work, as well as light pollution (light exposure at night) (59), and may lead to mood alterations (60, 61). Recently, a large population cross-sectional study (n = 91,105) using a wrist-worn accelerometer reported that lower relative amplitude of the circadian rhythm is associated with the lifetime prevalence of both MDD and BD (4). Individuals with circadian misalignment have higher depressive scores (62, 63). Moreover, a strong correlation between depressive symptoms and advances in dim light melatonin onset (DLMO) has been reported following an adjunctive multimodal chronobiological intervention organically combining psychoeducation, behavioral manipulation, and agomelatine intake (64). Bipolar disorder patients show delayed and decreased melatonin secretion during depressive and euthymic episodes (24, 65), with impaired psychosocial functioning and worse quality of life (24). In addition, manic and mixed episodes present with sustained phase advances, as well as a lower degree of rhythmicity corresponding to the severity of manic symptoms (66, 67). Apart from the daily (solar) cycle mentioned above, the lunar tidal cycles seem to entrain the mood cycles. In patients with rapid cycling BD, the periodicities in mood cycles have been observed to be synchronous with multiples of bi-weekly lunar tidal cycles (68).

The relationship between circadian rhythms and mood disorders is further supported by emerging genomic studies. In depressive cases, genetic association analyses have found SNPs in PER2 (10870), BMAL1 (rs2290035), NPAS2 (S471L), CRY2 (rs10838524), BHLHB2 (rs6442925), CLOCK (rs12504300), CSNK1E (rs135745), and TIMELESS (rs4630333 and rs1082214) (8, 9, 13). Single nucleotide polymorphisms in CSNK1E (rs135745), TIMELESS rs4630333, CRY2 (rs10838524), PER3 (rs707467 and rs10462020), RORB (rs1157358, rs7022435, rs3750420, and rs3903529), REV-ERBA (rs2314339) are strongly related to BD (8, 10–12, 69). In particular, CLOCK SNP rs1801260 contribute to the recurrence of mood episodes, while CRY2 SNP rs10838524 is significantly associated to rapid cycling BD (10, 70). Moreover, the arrhythmic expression of circadian genes including BMAL1, PER1–3, REV-ERBA, DBP, and BHLHE40/41, has been observed in postmortem brain tissues of MDD patients (15). Reduced amplitude of rhythmic expression for BMAL1, REV-ERBα, and DBP has been reported in fibroblast cultures of 12 BD patients (14). Recently, Park et al. have explored gene–gene interactions of clock genes using the non-parametric model-free multifactor-dimensionality reduction (MDR) method, and revealed optimal SNP combination models for predicting mood disorders (8). Specifically, the four-locus model differs between MDD (TIMELESS rs4630333, CSNK1E rs135745, BHLHB2 rs2137947, CSNK1E rs2075984) and BD (TIMELESS rs4630333, CSNK1E rs135745, PER3 rs228669, CLOCK rs12649507), supporting the clinical observation of different circadian characteristics in two disorders.

The Unbalanced Homeostatic Drive of Sleep in Mood Disorders

The sleep–wake cycle is significantly affected by mood disorders. Firstly, a disturbed sleep–wake cycle is one of the most common diagnostic criteria for mood disorders. Individuals suffering from manic or hypomanic episodes often show a reduced demand for the sleep, while depressive patients experience insomnia or hypersomnia (1). Delayed sleep–wake phase and evening chronotype is common in patients with mood disorders (24, 71, 72), and strongly associated with the severity of mood symptoms (73). Sleep deficits predict a poor prognosis with a higher risk of suicide (74). Furthermore, both polysomnography and self-reported studies have revealed longer sleep onset latency, a higher percentage of rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, more fragmentation of the sleep/wake rhythm, and daytime dysfunction in patients with mood disorders during the remission state relative to healthy controls (22, 75, 76). More importantly, sleep disturbance often serves as a prodrome of manic or depressive episodes. Several retrospective studies have revealed that sleep disturbance is the most robust early symptom of manic episodes and the sixth most common prodromal symptom of manic episodes (5, 23). Recently, a 10-year prospective study among adolescents and young adults reported that the sleep problem is a risk factor for the development of BD (77). Sleep abnormalities have also been highly related to subsequent depression (23, 78, 79). Moreover, sleep deprivation is reported to trigger manic-like behavior in animal models (80). Thus, some researchers speculate that a disturbed sleep–wake cycle is probably a causal factor triggering mood episodes. However, because of ethical reasons, sleep generally cannot be manipulated in human research and this weakens the causal evidence between the sleep–wake rhythm and mood disorders.

Chronotherapeutic Treatments in Mood Disorders

In response to the vital roles that Process C and S play in the onset and course of mood disorders, chronotherapeutic interventions have been successfully used. Sleep deprivation combined with bright light therapy has been implicated in improving depressive symptoms (72, 81–83), while virtual darkness therapy via blue-light-blocking increases the regularity of sleep and a rapid decline in manic symptoms (84). These treatments exert great influence on mood recovery by resetting the circadian clock. Also, the hormone melatonin (MT) secreted by the pineal gland acts on the circadian clock via MT1 receptors (85, 86), while the MT agonist agomelatine shows important properties for phase shifts of the clock and anti-depressive effects (21). Additionally, agomelatine functions as an antagonist for 5-HT2c receptors and modulates the master SCN clock via 5-HT innervations (87, 88). Similarly, other antidepressants can regulate the expression of the clock genes and thus affect the circadian rhythms (89). Fluoxetine, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) can shift electrical rhythms of the SCN and thus affect the behavior rhythm (16–18). Ketamine results in a rapid increase in glutamate level in the SCN and directly acts on NMDA receptors of the circadian clock in the epi-thalamic lateral habenula (LHb) (19, 20), suggesting that the rapid anti-depressive effects of ketamine might also be through the resetting of the circadian system (90). However, the mood stabilizer lithium is considered a clock-modifying drug in that it delays the sleep–wake cycle in healthy human and increase the length of the circadian period in non-human primates (91, 92). At the molecular level, lithium treatment can not only regulate the rhythm period via increasing PER2 mRNA levels, but also significantly augment the oscillation amplitude PER2 and CRY1 protein rhythms via inhibiting the phosphorylation of glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3B) (93, 94). Furthermore, the lithium efficacy is influenced by two GSK3B SNPs (rs334558 and rs3755557) (95). Considering all the above evidence, more pharmacological manipulations targeting the circadian rhythm and sleep drive are increasingly becoming plausible in the treatment of mood disorders.

Taken together, there seems to be a clear link between sleep disturbance and mood disorders, even though the underlying mechanisms remain unclear. The discovery of the glymphatic system provides researchers with insights into sleep-related diseases.

Sleep and the Glymphatic System

Overview of the Glymphatic System

The lymphatic system accounts for the clearance of ISF and it is also critical to both hydrostatic and homeostatic maintenance (96). With regard to lymphatic system in central nervous system (CNS), it consists of two interacting system, the glymphatic (glia-lymphatic) system and the meningeal lymphatic vessels (97). The glymphatic system is responsible for exchanging between CSF and ISF, and clearing solutes and metabolites from the brain parenchyma through a unique system of perivascular tunnels. More specifically, CSF produced by the choroid plexus and capillary influx is pumped deep into the brain parenchyma via arterial pulsation (36, 98). In the perivascular space (PVS), CSF exchanges with ISF, accompanied by clearance of soluble metabolic waste like Aβ (36). Indeed, large and eccentric PVS provides considerably less hydraulic resistance to CSF-ISF flow compared to concentric annular tunnel (99, 100). During the clearance of solutes, convection coexists with diffusion in the glymphatic system (101–103). It is argued that in the brain interstitium, small molecule transport is best explained by diffusion while convection becomes more predominant with increasing molecular size (104). However, the exact contributions of the two processes are highly dynamic and remain controversial, with one of the reasons being that the glymphatic influx and efflux are influenced by arousal state, pulse, respiration, body position, and more (98, 103, 105, 106). Moreover, CSF–ISF and solutes drain from the CNS via meningeal and cervical lymphatic vessels, as well as the cranial and spinal nerve roots (107, 108). Therefore, interference of the lymphatic system, such as ultraviolet photoablation of meningeal lymphatic vessels and ligation of cervical lymphatics, accounts for the stagnation of glymphatic flow and aggregation of metabolic wastes like Aβ (109, 110).

More importantly, the glymphatic system is supported by the water channel AQP4 which is primarily expressed by the astrocytic endfeet (36). Animals lacking AQP4 exhibit slower CSF influx and less interstitial solute clearance (70% reduction) (36, 111, 112). Deletion of the AQP4 in APP/PS1 transgenic mice results in increased interstitial Aβ plaque accumulation, cerebral amyloid angiopathy, as well as loss of synaptic protein and brain-derived neurotrophic factor in the hippocampus and cortex (113). However, it should be noted that the role of AQP4 in glymphatic clearance function are debated (103, 106). Smith et al. have found that AQP4 gene deletion mice exhibited a similar Aβ distribution as wildtype mice, suggesting that AQP4 gene deletion did not impair clearance of Aβ (114).

Sleep-Dependent Glymphatic Cycling

Emerging evidence reveals that the function of the glymphatic system fluctuates daily along with the sleep–wake cycle. A two-photon imaging study reported a 60% increase in the interstitial space and two-fold faster clearance of Aβ in natural sleep or anesthesia mice compared with awake mice (27). A coherent pattern of slow-wave activity and CSF influx has been observed during NREM sleep in humans, supporting the exciting possibility of sleep-regulated glymphatic function (25). However, recent evidence using contrast-enhanced MRI has revealed that the glymphatic system is controlled by the circadian rhythm rather than by the sleep–wake cycle (115, 116). The parenchymal redistribution of contrast agent is lowest during the light phase and highest during the dark phase in fully awake rats, regardless of normal or reversed light–dark cycles (115). The diurnal variation of glymphatic cycling persists even under constant light or anesthesia, suggesting the hypothesis that endogenous circadian oscillations determine glymphatic function (116). The discrepancy may be related to the extreme differences in the circadian rhythm between humans and rodents (117). Rodents are nocturnal animals with opposite circadian phase, and they are also poly-phasic sleepers with relatively low sleep drive (118). Presently, the exact contributions of the light–dark cycle, sleep–wake cycle, and other physiological rhythms remain unknown (116). Further studies are warranted to confirm the circadian control of the glymphatic system in humans.

Surprisingly, the deletion of AQP4 effectively eliminates the circadian rhythm in glymphatic fluid transport (116). A recent genomic study reports that AQP4-haplotype influences sleep homeostasis in NREM sleep and response to prolonged wakefulness (119), providing supporting evidence for the sleep-dependent glymphatic pathway. The high polarization of AQP4 in astrocytic endfeet is under the control of the circadian rhythm, and thus, modulates bulk fluid movement, CSF–ISF exchange, and solutes clearance (116). Conversely, there is also evidence that astrocytes repress SCN neurons and regulate circadian timekeeping via glutamate signaling (120). Thus, astrocytes and AQP4 present a checkpoint for the functional glymphatic system during deep sleep.

Considerable evidence suggests a causal relationship between sleep and regulation of the glymphatic flow, thus modulating protein clearance. Sleep disturbance (including shorter total sleep time, sleep fragmentation, and lack of NREM III) causes suppressed glymphatic function and a decline in the clearance of metabolic waste, hence contributing to the development and progression of various neurological diseases including AD (30), PD (31), stroke (32, 33), and iNPH (34, 35).

Taken together, the glymphatic function is considered as a brain fluid transport with astrocyte-regulated mechanisms, while glymphatic dysfunction is intimately associated with neurological diseases, especially neurodegenerative diseases with cognitive decline (30, 31).

Glymphatic Dysfunction in Mood Disorders

Abnormalities of Glymphatic Flow, Astrocytes, and AQP4 in Depression

Individuals suffering from depressive episodes always show diverse cognitive decline (1), including attention, memory, response inhibition, decision speed, and so on. Depression has been considered as a prodrome of dementia (121), with increased Aβ deposition reported in an (18) F-florbetapir positron emission tomography (PET) imaging study (122). These observations raise the exciting possibility that wide-spread disruption of the glymphatic system exists in depression. Recent animal studies using chronic unpredictable mild stress (CUMS) model have provided supporting evidence for the glymphatic dysfunction in depression (47, 48) (Table 1). In the CUMS model, animals were exposed to the various stressors randomly for several weeks and injected with fluorescence tracers from cisterna magna to estimate the glymphatic function (47, 48). The CSF tracer penetration in the brain of CUMS-treated mice was significantly decreased, and recovered to the control level after fluoxetine administration or polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) supplementation (47, 48). In parallel with the impaired glymphatic circulation, the increased deposition of Aβ has been observed (47, 48). Amyloid-β accumulation along the blood vessels, in turn, could impair glymphatic function by reducing PVS and increasing hydraulic resistance, and thus result in a more severe parenchymal build-up of Aβ and neuronal death (134). Another plausible explanation of PVS closure induced by CUMS is the alteration of arterial pulsation and compliance that triggered by neuroinflammation and restored by daily PUFA supplementation (48) (Table 1).

Table 1

| References | Studied cohort | Method | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Xia et al. (47) | CUMS model mice | Injection of tracers, immunohistochemistry | Impaired glymphatic circulation and increased accumulation of Aβ42, which can be reversed by fluoxetine treatment. Downregulated AQP4 expression in cortex and hippocampus, which can be reversed by fluoxetine treatment. |

| Liu et al. (48) | CUMS model mice | Injection of tracers, immunohistochemistry | Impaired glymphatic circulation and cerebrovascular reactivity, which can be reversed by PUFA supplementation. Decreased Aβ40 clearance, which can be reversed by PUFA supplementation and escitalopram treatment. Decreased astrocytes and AQP4 expression, which can be reversed by PUFA supplementation and escitalopram treatment. |

| Gong et al. (123) | CMS model mice | Immunohistochemistry | Decreased hippocampal astrocyte is passed on to offsprings via an epigenetic mechanism. |

| Czéh et al. (124) | Chronic psychosocial stress mice | Immunohistochemistry | Fluoxetine treatment prevented the stress-induced numerical decrease of astrocytes. |

| Kinoshita et al. (125) | VNUT-knockout mice | Immunohistochemistry, qPCR | Fluoxetine increased ATP exocytosis and BDNF in astrocytes. |

| Hisaoka-Nakashima et al. (126) | Rat primary astrocytes, C6 astroglia cells | qPCR, ELISA, western blotting | Mirtazapine treatment increased mRNA expression of GDNF and BDNF in astrocytes. |

| Wang et al. (127) | Mice | Western blotting | Ketamine promotes the activation of astrocyte. |

| Lasič et al. (128) | Rat primary astrocytes | Structured illumination microscopy and image analysis | Ketamine induced cholesterol redistribution in the plasmalemma of astrocytes. |

| Xue et al. (129) | CUS model rats | Immunohistochemistry, qPCR | Repetitive TMS at 5 Hz increased the expression of DAGLα and CB1R in hippocampal astrocytes and neurons. |

| Taler et al. (130) | CUMS model rats | Immunohistochemistry, western blotting, ELISA | Lithium can attenuate the reduction of AQP4 and disruption of the neurovascular unit in hippocampus. |

| Wang et al. (131) | LPS-induced depression model mice | Immunohistochemistry, qPCR | Inhibition of activated astrocytes ameliorates LPS-induced depressive-like behavior. |

| Portal et al. (132) | Cx43 KD male mice | Immunohistochemistry, western blotting | Inactivation of astroglial connexin 43 potentiated the antidepressant-like effects of fluoxetine. |

| Kong et al. (133) | CMS model mice | Immunohistochemistry, western blotting | AQP4 knockout disrupted fluoxetine-induced enhancement of hippocampal neurogenesis, as well as behavioral improvement. |

Glymphatic flow, astrocytes, and AQP4 in animal studies.

Aβ, amyloid-β; AQP4, aquaporin-4; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; BDNF, brain-derived neurotrophic factor; CB1R, cannabinoid type 1 receptor; CMS, chronic mild stress; CUMS, chronic unpredictable mild stress; CUS, chronic unpredictable stress; Cx43 KD, connexin 43 knock-down; DAGLα, diacylglycerol lipase alpha; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays; GDNF, glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor; GFAP, glial fibrillary acidic protein; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; mRNA, messenger RNA; PUFA, polyunsaturated fatty acid; qPCR, quantitative polymerase chain reaction; TMS, transcranial magnetic stimulation; VNUT, vesicular nucleotide transporter.

During the neuroinflammatory response, reactive astrocytosis, and AQP4 depolarization have been widely reported in depression (48). Abundant evidence indicated astrocytic abnormalities in patients with depression (Table 2). Golgi-staining of postmortem tissues from depressed suicide cases has revealed reactive astrocytosis within the cingulate cortex (37). Additionally, glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), one of the astrocyte-specific biomarkers, is reduced in depression-associated brain regions including the prefrontal cortex, cingulate cortex (38, 39), hippocampus (40), amygdala (41), locus coeruleus (44), cerebellum (146), thalamus, and caudate nuclei (42). A lower density of S100β-immunopositive astrocytes has been reported in the bilateral hippocampus and locus coeruleus of depressive patients compared to that of healthy controls (44, 135). Downregulated expression of AQP4 has been found in postmortem locus coeruleus and hippocampus in MDD patients (44, 136). More importantly, the reduction in astrocyte density is passed on to offsprings of depressive females via an epigenetic mechanism (123) (Table 1). Nevertheless, there are several contradictory results (Table 2). The density of astrocytes has been observed unchanged in the cingulate cortex and hippocampus of MDD patients (142, 144). A postmortem study using quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) have observed upregulated expression of GFAP and aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 family member L1 (ALDH1L1) in the basal ganglia of MDD patients (145). Another postmortem study using microarray analysis and qPCR has found upregulated expression of AQP4 in the prefrontal cortex of MDD patients. Obviously, the variety of studied methods involving Glogi-staining, Nissl-staining, qPCR, western blotting, and immunohistochemistry, contributes to the discrepancies.

Table 2

| References | Studied cohort | Tested sample | Method | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Torres-Platas et al. (37) | 10 Depressed suicides, 10HC | Postmortem tissue | Golgi-staining | Reactive astrocytosis within the cingulate cortex of depressive patients. |

| Torres-Platas et al. (42) | 22 Depressed suicides, 22HC | Postmortem tissue | Immunohistochemistry, qPCR | Downregulation of GFAP mRNA and protein in the mediodorsal thalamus and caudate nucleus of depressed suicides. |

| Webster et al. (38) | 15MDD, 15BD, 15HC | Postmortem tissue | In situ hybridization | Decreased level of GFAP mRNA in the cingulate cortex of BD patients. Decreased level of GFAP mRNA in the cingulate cortex of MDD patients (not significantly). |

| Gittins et al. (39) | 5MDD, 2BD, 9HC | Postmortem tissue | Immunohistochemistry | Decreased GFAP protein in the anterior cingulate cortex of patients with mood disorders. |

| Cobb et al. (40) | 17MDD, 17HC | Postmortem tissue | Immunohistochemistry | Decreased GFAP-positive astrocytes in the left hippocampus of depressive patients. |

| Altshuler et al. (41) | 11MDD, 10BD, 14HC | Postmortem tissue | Immunohistochemistry | Decreased GFAP-positive astrocytes in the amygdala of depressive patients. Unchanged GFAP-positive astrocytes in the amygdala of BD patients. |

| Bernard et al. (44) | 12MDD, 6BD, 9HC | Postmortem tissue | In situ hybridization | Downregulated expression of GFAP, S100B and AQP4 in locus coeruleus of MDD patients. |

| Gos et al. (135) | 9MDD, 6BD, 13HC | Postmortem tissue | Immunohistochemistry | Decreased S100β-immunopositive astrocytes in the bilateral hippocampus of depressive patients. |

| Medina et al. (136) | 13MDD, 10HC | Postmortem tissue | Microarray analysis, qPCR | Downregulated AQP4 mRNA expression in hippocampus of MDD patients. |

| Feresten AH et al. (137) | 34BD, 35HC | Postmortem tissue | Western blotting | Increased GFAP expression of in BA9 of BD patients. Unchanged levels of vimentin and ALDH1L1 in BA9 of BD patients. |

| Johnston-Wilson et al. (138) | 19MDD, 23BD, 23HC | Postmortem tissue | Western blotting | Decreased GFAP-positive astrocytes in BA10 of BD patients. |

| Toro et al. (139) | 15MDD, 15BD, 15HC | Postmortem tissue | Immunohistochemistry | Decreased GFAP-positive astrocytes in BA11/47 of BD patients. |

| Dean et al. (140) | 8BD, 20HC | Postmortem tissue | Western blotting, qPCR | Increased S100β in BA40 of BD patients. Decreased S100β in BA9 of BD patients. |

| Hercher et al. (141) | 20BD, 20HC | Postmortem tissue | Immunohistochemistry | Unchanged density of astrocytes in the frontal cortex of BD patients. |

| Williams et al. (142) | 20MDD, 16BD, 20HC | Postmortem tissue | Immunohistochemistry | Unchanged density of astrocytes in the cingulate cortex of patients with mood disorder. |

| Pantazopoulos et al. (143) | 11BD, 15HC | Postmortem tissue | Immunohistochemistry | Unchanged density of astrocytes in the amygdala and entorhinal cortex of BD patients. |

| Malchow et al. (144) | 8MDD, 8BD, 10HC | Postmortem tissue | Nissl-staining | Unchanged density of astrocytes in the hippocampus of patients with mood disorder. |

| Barley et al. (145) | 14MDD, 14BD, 15HC | Postmortem tissue | qPCR | Upregulated expression of GFAP and ALDH1L1 the basal ganglia of MDD patients. Upregulated expression of GFAP and ALDH1L1 the basal ganglia of BD patients (not significantly). |

| Fatemi et al. (146) | 15MDD, 15BD, 15HC | Postmortem tissue | Western blotting | Decreased GFAP in the cerebellum of patients with mood disorders. |

| Steiner et al. (147) | 9MDD, 5BD, 10HC | Postmortem tissue | Immunohistochemistry | No change in GFPA-immunopositive astrocytes of patients with mood disorder. |

| da Rosa et al. (148) | 52 manic BD, 52HC | Serum | meta-analysis | Increased S100β levels in serum of patients with manic episodes. |

| Zhao et al. (46) | 50BD II, 43HC | eDWI | ADCuh | Increased ADCuh values in bilateral SCP and cerebellar hemisphere, which positively associated with depressive scores. |

| Iwamoto et al. (149) | 11MDD, 11BD, 15HC | Postmortem tissue | Microarray analysis, qPCR | Upregulated expression of AQP4 in the prefrontal cortex of patients with mood disorders. |

Astrocytes and AQP4 in patients with mood disorder.

AQP4, aquaporin-4; ADCuh, apparent diffusion coefficient from ultra-high b-values; ALDH1L1, aldehyde dehydrogenase 1L1; BA, Brodmann area; BD, bipolar disorder; eDWI, enhanced diffusion-weighted imaging; GFAP, glial fibrillary acidic protein; HC, health control; mRNA, messenger RNA; qPCR, quantitative polymerase chain reaction; SCP, superior cerebellar peduncles.

However, emerging animal studies provide powerful evidence implying the pathological alterations of astrocytes and AQP4 in depression. Decreased astrocytes and downregulated AQP4 expression have been reported in various animal models of depression (47, 48, 123, 124, 130) (Table 1), supporting dysfunctional glymphatic transport in depression. Effective antidepressant therapy, such as fluoxetine (47, 124, 125), escitalopram (48), mirtazapine (126), ketamine (127, 128), and repetitive high-frequency transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) (129) could benefit the functioning of both astrocytes and AQP4, and hence alleviate depressive-like behaviors. Additionally, the synergistic agents of antidepressant—lithium—can attenuate the reduction of AQP4 and disruption of the neurovascular unit in the hippocampus of CUMS rats (130), resulting in a functioning glymphatic system. These therapeutic effects can be suppressed by AQP4 knockout. More specifically, AQP4 deficiency abolishes fluoxetine treatment-induced hippocampal neurogenesis and behavioral improvement in depressive mice (133). Recent studies indicate that the therapeutic option for depression is via the restoration of astrocytes function, AQP4, and glymphatic system (131, 132), which provide further supporting evidence for the critical role of glymphatic flow in depression.

Abnormalities of Astrocytes and AQP4 in Bipolar Disorders

To date, the role of the glymphatic function in BD has not been widely studied. However, astrocytic dysfunction has undoubtedly been implicated in the development of BD (43). Different from MDD, pictures from human postmortem studies in BD appear to be highly heterogeneous (Table 2). The density of GFAP-positive astrocytes is reported to be significantly increased in Brodmann area (BA) 9 (137) and reduced in BA10 (138), BA24 (38), BA11, and BA 47 (139), while the level of S100β has been reported to be increased in BA40 and reduced in BA9 (140). Other studies on human postmortem tissues from BD exhibit an unchanged density of astrocytes in the frontal cortex (141), cingulate cortex (142), amygdala (41, 143), hippocampus (144), entorhinal cortex (143), basal ganglia (145), dorsal raphe nucleus, and cerebellum (146). The considerable discrepancy is on account of various confounding factors, including phenotype (depressive episode, manic episode, or remission state) (150), cause of death (depressive suicide or physical diseases) (141, 144), comorbidity (150, 151), the methodology used (137, 144), and the brain regions studied (139, 140). Therefore, additional studies regarding diverse phenotypes of BD are essential to investigate state-related abnormalities of astrocytes (152). In patients with bipolar depression, a reduction in S100β-immunopositive astrocytes has been observe, but with no change in GFAP-immunopositive astrocytes (135, 147). As for manic states, in vivo studies have revealed increased serum levels of S100β, suggesting astrocytic activation (148).

Upregulated expression of AQP4 in the prefrontal cortex has been revealed in BD (149). Evaluation of the qualitative alterations of astrocytes (especially AQP4 function) is far much valuable than quantitative alterations. The apparent diffusion coefficient from ultra-high b-values (ADC uh), a parameter of enhanced diffusion-weighted imaging (eDWI), can reflect the function of AQP4 (45). In individuals suffering from bipolar depression, increased ADC uh values in bilateral superior cerebellar peduncles (SCP) and cerebellar hemisphere is positively associated with depressive scores, implying that a positive correlation exists between the upregulated expression of AQP4 and severity of depression (46). A plausible explanation is that increased and depolarized AQP4 impair water homeostasis and glymphatic transport in BD (149). Lithium is a classical mood-stabilizer, and its effect of regulating AQP4 function is discussed above (130). Additionally, other mood-stabilizers such as valproic acid, topiramate, and lamotrigine have been shown to inhibit AQP4 (153), and hence regulate directed glymphatic flow.

Even though direct evidence for glymphatic impairment in mood disorders is lacking, astrocytes and AQP4 abnormalities provide support to the hypothesis that glymphatic dysfunction functions as a bridge between sleep disturbance and mood disorders. Additionally, treatments for mood improvement, including medicines, light therapy, sleep invention, and TMS can regulate the function of astrocytes and AQP4. Therefore, AQP4-dependent glymphatic system may serve as a new therapeutic target in mood disorders.

Conclusion and Outlook

Mood symptoms often occur with the onset of sleep disturbance and ameliorate with improved sleep disturbance. Moreover, early-life sleep problems due to jet-lag, social jet-lag, shift-work, or light pollution can significantly increase the lifetime risk of mood disorders (60). In addition, sleep deprivation can directly trigger mania-like symptoms (80). Based on considerable evidence, a causal relationship between sleep disturbance and mood disorders is hypothesized (154). Therefore, how does disrupted sleep affect the development and phenotype of mood disorders? An intriguing possibility has emerged that glymphatic dysfunction serves as a bridge between sleep disturbance and mood disorders. Adequate sleep, especially deep sleep (NREM III), is a key factor in the functioning of the glymphatic system which accounts for the clearance of metabolic wastes. The effects of sleep on the glymphatic system are mainly dependent on the dynamic alterations of astrocytic function and AQP4 distribution (113, 119, 155). Significantly, suppressed glymphatic circulation, astrocytic abnormalities, and AQP4 depolarization are consistently reported in mood disorders, providing support for the posited hypothesis.

However, several limitations exist in this study. First, much of the existing evidence on the glymphatic system has been conducted in rodents and only a few in humans. Although sleep is an evolutionarily conserved physiological behavior, the reversed circadian rhythms and polyphasic sleep which reduces sleep pressure in rodents make it less representative. Most of the current human studies use invasive methods such as intrathecal injection of contrast agents, while the ADCuh value obtained from the emerging eDWI fails to identify the distribution of AQP4. Therefore, non-invasive methods to explore the glymphatic system in humans are necessary for future studies. Secondly, there is a lack of evidence of known metabolic wastes that fail to be cleared by the glymphatic system and trigger or exacerbate mood symptoms, such as Aβ in AD and α-synuclein in PD. Exploring the excessive metabolic wastes in mood disorders is warranted, and can provide promising biomarkers for indicating the occurrence and severity of mood disorders.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author contributions

TY, YQ, and LY defined the research questions and aims of the study. TY and YQ carried out the literature search, selected and interpreted relevant articles, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. XY made the original figure and tables. LY and XY critically appraised the texts, figure and tables, corrected them, and made suggestions for further improvement. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (81901319 and 81901706).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

- MDD

major depression disorder

- BD

bipolar disorder

- AQP4

aquaporin-4

- SCN

suprachiasmatic nuclei

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphisms

- NREM III

stage 3 non-rapid eye movement sleep

- CSF

cerebrospinal fluid

- ISF

interstitial fluid

- Aβ

amyloid-β

- AD

Alzheimer's disease

- PD

Parkinson's disease

- iNPH

idiopathic normal cranial pressure hydrocephalus

- EEG

electroencephalogram

- DLMO

dim light melatonin onset

- MDR

multifactor-dimensionality reduction

- REM

rapid eye movement sleep

- MT

melatonin

- SSRI

selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor

- LHb

lateral habenula

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- CNS

central nervous system

- PET

positron emission tomography

- RBD

REM sleep behavior disorder

- DTI

diffusion tensor imaging

- ALPS

analysis along the perivascular space

- CUMS

chronic unpredictable mild stress

- PUFA

polyunsaturated fatty acid

- GFAP

glial fibrillary acidic protein

- TMS

transcranial magnetic stimulation

- BA

Brodmann area

- ADC uh

the apparent diffusion coefficient from ultra-high b-values

- eDWI

enhanced diffusion-weighted imaging

- SCP

superior cerebellar peduncles

- PVS

perivascular space

- ALDH1L1

aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 family member L1

- qPCR

quantitative polymerase chain reaction.

Abbreviations

References

1.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). 5th edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing (2013).

2.

GrandeIBerkMBirmaherBVietaE. Bipolar disorder. Lancet (London, England). (2016) 387:1561–72. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00241-X

3.

O'Leary OF Dinan TG Cryan JF. Faster, better, stronger: towards new antidepressant therapeutic strategies. Eur J Pharmacol. (2015) 753:32–50. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2014.07.046

4.

LyallLMWyseCAGrahamNFergusonALyallDMCullenBet al. Association of disrupted circadian rhythmicity with mood disorders, subjective wellbeing, and cognitive function: a cross-sectional study of 91 105 participants from the UK Biobank. Lancet Psychiatry. (2018) 5:507–14. 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30139-1

5.

JacksonACavanaghJScottJ. A systematic review of manic and depressive prodromes. J Affect Disord. (2003) 74:209–17. 10.1016/S0165-0327(02)00266-5

6.

BorbélyAADaanSWirz-JusticeADeboerT. The two-process model of sleep regulation: a reappraisal. J Sleep Res. (2016) 25:131–43. 10.1111/jsr.12371

7.

YamazakiSNumanoRAbeMHidaATakahashiRUedaMet al. Resetting central and peripheral circadian oscillators in transgenic rats. Science. (2000) 288:682–5. 10.1126/science.288.5466.682

8.

ParkMKimSAYeeJShinJLeeKYJooEJ. Significant role of gene-gene interactions of clock genes in mood disorder. J Affect Disord. (2019) 257:510–7. 10.1016/j.jad.2019.06.056

9.

LavebrattCSjöholmLKSoronenPPaunioTVawterMPBunneyWEet al. CRY2 is associated with depression. PLoS ONE. (2010) 5:e9407. 10.1371/journal.pone.0009407

10.

SjöholmLKBacklundLChetehEHEkIRFrisénLSchallingMet al. CRY2 is associated with rapid cycling in bipolar disorder patients. PLoS ONE. (2010) 5:e12632. 10.1371/journal.pone.0012632

11.

Brasil RochaPMCamposSBNevesFSda Silva FilhoHC. Genetic association of the PERIOD3 (Per3) clock gene with bipolar disorder. Psychiatry Investig. (2017) 14:674–80. 10.4306/pi.2017.14.5.674

12.

McGrathCLGlattSJSklarPLe-NiculescuHKuczenskiRDoyleAEet al. Evidence for genetic association of RORB with bipolar disorder. BMC Psychiatry. (2009) 9:70. 10.1186/1471-244X-9-70

13.

PartonenTTreutleinJAlpmanAFrankJJohanssonCDepnerMet al. Three circadian clock genes Per2, Arntl, and Npas2 contribute to winter depression. Ann Med. (2007) 39:229–38. 10.1080/07853890701278795

14.

YangSVan DongenHPWangKBerrettiniWBućanM. Assessment of circadian function in fibroblasts of patients with bipolar disorder. Mol Psychiatry. (2009) 14:143–55. 10.1038/mp.2008.10

15.

LiJZBunneyBGMengFHagenauerMHWalshDMVawterMPet al. Circadian patterns of gene expression in the human brain and disruption in major depressive disorder. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2013) 110:9950–5. 10.1073/pnas.1305814110

16.

HorikawaKYokotaSFujiKAkiyamaMMoriyaTOkamuraHet al. Nonphotic entrainment by 5-HT1A/7 receptor agonists accompanied by reduced Per1 and Per2 mRNA levels in the suprachiasmatic nuclei. J Neurosci. (2000) 20:5867–73. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-15-05867.2000

17.

HorikawaKShibataS. Phase-resetting response to (+)8-OH-DPAT, a serotonin 1A/7 receptor agonist, in the mouse in vivo. Neurosci Lett. (2004) 368:130–4. 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.06.072

18.

ShibataSTsuneyoshiAHamadaTTominagaKWatanabeS. Phase-resetting effect of 8-OH-DPAT, a serotonin1A receptor agonist, on the circadian rhythm of firing rate in the rat suprachiasmatic nuclei in vitro. Brain Res. (1992) 582:353–6. 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90156-4

19.

Orozco-SolisRMontellierEAguilar-ArnalLSatoSVawterMPBunneyBGet al. A circadian genomic signature common to ketamine and sleep deprivation in the anterior cingulate cortex. Biol Psychiatry. (2017) 82:351–60. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.02.1176

20.

CuiYHuSHuH. Lateral habenular burst firing as a target of the rapid antidepressant effects of ketamine. Trends Neurosci. (2019) 42:179–91. 10.1016/j.tins.2018.12.002

21.

de BodinatCGuardiola-LemaitreBMocaërERenardPMuñozCMillanMJ. Agomelatine, the first melatonergic antidepressant: discovery, characterization and development. Nat Rev Drug Discov. (2010) 9:628–42. 10.1038/nrd3140

22.

JonesSHHareDJEvershedK. Actigraphic assessment of circadian activity and sleep patterns in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. (2005) 7:176–86. 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2005.00187.x

23.

JaussentIBouyerJAncelinMLAkbaralyTPérèsKRitchieKet al. Insomnia and daytime sleepiness are risk factors for depressive symptoms in the elderly. Sleep. (2011) 34:1103–10. 10.5665/SLEEP.1170

24.

BradleyAJWebb-MitchellRHazuASlaterNMiddletonBGallagherPet al. Sleep and circadian rhythm disturbance in bipolar disorder. Psychol Med. (2017) 47:1678–89. 10.1017/S0033291717000186

25.

FultzNEBonmassarGSetsompopKStickgoldRARosenBRPolimeniJRet al. Coupled electrophysiological, hemodynamic, and cerebrospinal fluid oscillations in human sleep. Science. (2019) 366:628–31. 10.1126/science.aax5440

26.

HablitzLMVinitskyHSSunQStægerFFSigurdssonBMortensenKNet al. Increased glymphatic influx is correlated with high EEG delta power and low heart rate in mice under anesthesia. Sci Adv. (2019) 5:eaav5447. 10.1126/sciadv.aav5447

27.

XieLKangHXuQChenMJLiaoYThiyagarajanMet al. Sleep drives metabolite clearance from the adult brain. Science. (2013) 342:373–7. 10.1126/science.1241224

28.

SimonMJWangMXMurchisonCFRoeseNEBoespflugELWoltjerRLet al. Transcriptional network analysis of human astrocytic endfoot genes reveals region-specific associations with dementia status and tau pathology. Sci Rep. (2018) 8:12389. 10.1038/s41598-018-30779-x

29.

van DijkKDBidinostiMWeissARaijmakersPBerendseHWvan de BergWD. Reduced α-synuclein levels in cerebrospinal fluid in Parkinson's disease are unrelated to clinical and imaging measures of disease severity. Eur J Neurol. (2014) 21:388–94. 10.1111/ene.12176

30.

RohJHHuangYBeroAWKastenTStewartFRBatemanRJet al. Disruption of the sleep-wake cycle and diurnal fluctuation of β-amyloid in mice with Alzheimer's disease pathology. Sci Transl Med. (2012) 4:150ra122. 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004291

31.

SundaramSHughesRLPetersonEMüller-OehringEMBrontë-StewartHMPostonKLet al. Establishing a framework for neuropathological correlates and glymphatic system functioning in Parkinson's disease. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. (2019) 103:305–15. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.05.016

32.

GaberelTGakubaCGoulayRMartinez De LizarrondoSHanouzJLEmeryEet al. Impaired glymphatic perfusion after strokes revealed by contrast-enhanced MRI: a new target for fibrinolysis?Stroke. (2014) 45:3092–6. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.006617

33.

PuTZouWFengWZhangYWangLWangHet al. Persistent malfunction of glymphatic and meningeal lymphatic drainage in a mouse model of subarachnoid hemorrhage. Exp Neurobiol. (2019) 28:104–18. 10.5607/en.2019.28.1.104

34.

RingstadGVatneholSASEidePK. Glymphatic MRI in idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. Brain. (2017) 140:2691–705. 10.1093/brain/awx191

35.

RingstadGValnesLMDaleAMPrippAHVatneholSSEmblemKEet al. Brain-wide glymphatic enhancement and clearance in humans assessed with MRI. JCI Insight. (2018) 3:e121537. 10.1172/jci.insight.121537

36.

IliffJJWangMLiaoYPloggBAPengWGundersenGAet al. A paravascular pathway facilitates CSF flow through the brain parenchyma and the clearance of interstitial solutes, including amyloid β. Sci Transl Med. (2012) 4:147ra111. 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003748

37.

Torres-PlatasSGHercherCDavoliMAMaussionGLabontéBTureckiGet al. Astrocytic hypertrophy in anterior cingulate white matter of depressed suicides. Neuropsychopharmacology. (2011) 36:2650–8. 10.1038/npp.2011.154

38.

WebsterMJO'GradyJKleinmanJEWeickertCS. Glial fibrillary acidic protein mRNA levels in the cingulate cortex of individuals with depression, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Neuroscience. (2005) 133:453–61. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.02.037

39.

GittinsRAHarrisonPJ. A morphometric study of glia and neurons in the anterior cingulate cortex in mood disorder. J. Affect. Disord. (2011) 133:328–32. 10.1016/j.jad.2011.03.042

40.

CobbJAO'NeillKMilnerJMahajanGJLawrenceTJMayWLet al. Density of GFAP-immunoreactive astrocytes is decreased in left hippocampi in major depressive disorder. Neuroscience. (2016) 316:209–20. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.12.044

41.

AltshulerLLAbulseoudOAFoland-RossLBartzokisGChangSMintzJet al. Amygdala astrocyte reduction in subjects with major depressive disorder but not bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. (2010) 12:541–9. 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2010.00838.x

42.

Torres-PlatasSGNagyCWakidMTureckiGMechawarN. Glial fibrillary acidic protein is differentially expressed across cortical and subcortical regions in healthy brains and downregulated in the thalamus and caudate nucleus of depressed suicides. Mol Psychiatry. (2016) 21:509–15. 10.1038/mp.2015.65

43.

PengLLiBVerkhratskyA. Targeting astrocytes in bipolar disorder. Exp Rev. Neurotherap. (2016) 16:649–57. 10.1586/14737175.2016.1171144

44.

BernardRKermanIAThompsonRCJonesEGBunneyWEBarchasJDet al. Altered expression of glutamate signaling, growth factor, and glia genes in the locus coeruleus of patients with major depression. Mol Psychiatry. (2011) 16:634–46. 10.1038/mp.2010.44

45.

XueyingLZhongpingZZhousheZLiGYongjinTChangzhengSet al. Investigation of apparent diffusion coefficient from ultra-high b-values in Parkinson's disease. Eur Radiol. (2015) 25:2593–600. 10.1007/s00330-015-3678-3

46.

ZhaoLLuoZQiuSJiaYZhongSChenGet al. Abnormalities of aquaporin-4 in the cerebellum in bipolar II disorder: an ultra-high b-values diffusion weighted imaging study. J Affect Disord. (2020) 274:136–43. 10.1016/j.jad.2020.05.035

47.

XiaMYangLSunGQiSLiB. Mechanism of depression as a risk factor in the development of Alzheimer's disease: the function of AQP4 and the glymphatic system. Psychopharmacology (Berl). (2017) 234:365–79. 10.1007/s00213-016-4473-9

48.

LiuXHaoJYaoECaoJZhengXYaoDet al. Polyunsaturated fatty acid supplement alleviates depression-incident cognitive dysfunction by protecting the cerebrovascular and glymphatic systems. Brain Behav Immun. (2020) 89:357–70. 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.07.022

49.

BauduccoSRichardsonCGradisarM. Chronotype, circadian rhythms and mood. Curr Opin Psychol. (2020) 34:77–83. 10.1016/j.copsyc.2019.09.002

50.

TakahashiJS. Molecular components of the circadian clock in mammals. Diabetes Obes Metab. (2015) 17(Suppl. 1):6–11. 10.1111/dom.12514

51.

PreitnerNDamiolaFLopez-MolinaLZakanyJDubouleDAlbrechtUet al. The orphan nuclear receptor REV-ERBalpha controls circadian transcription within the positive limb of the mammalian circadian oscillator. Cell. (2002) 110:251–60. 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00825-5

52.

DeBruyneJPWeaverDRReppertSM. CLOCK and NPAS2 have overlapping roles in the suprachiasmatic circadian clock. Nat Neurosci. (2007) 10:543–5. 10.1038/nn1884

53.

YamaguchiSMitsuiSYanLYagitaKMiyakeSOkamuraH. Role of DBP in the circadian oscillatory mechanism. Mol Cell Biol. (2000) 20:4773–81. 10.1128/MCB.20.13.4773-4781.2000

54.

AryalRPKwakPBTamayoAGGebertMChiuPLWalzTet al. Macromolecular assemblies of the mammalian circadian clock. Mol Cell. (2017) 67:770.e6–82.e6. 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.07.017

55.

HonmaSKawamotoTTakagiYFujimotoKSatoFNoshiroMet al. Dec1 and Dec2 are regulators of the mammalian molecular clock. Nature. (2002) 419:841–4. 10.1038/nature01123

56.

MazzoccoliGLaukkanenMOVinciguerraMColangeloTColantuoniV. A timeless link between circadian patterns and disease. Trends Mol Med. (2016) 22:68–81. 10.1016/j.molmed.2015.11.007

57.

RodriguezAVFunkCMVyazovskiyVVNirYTononiGCirelliC. Why does sleep slow-wave activity increase after extended wake? Assessing the effects of increased cortical firing during wake and sleep. J. Neurosci. (2016) 36:12436–47. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1614-16.2016

58.

NedergaardMGoldmanSA. Glymphatic failure as a final common pathway to dementia. Science. (2020) 370:50–6. 10.1126/science.abb8739

59.

FosterRGPeirsonSNWulffKWinnebeckEVetterCRoennebergT. Sleep and circadian rhythm disruption in social jetlag and mental illness. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. (2013) 119:325–46. 10.1016/B978-0-12-396971-2.00011-7

60.

InderMLCroweMTPorterR. Effect of transmeridian travel and jetlag on mood disorders: evidence and implications. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. (2016) 50:220–7. 10.1177/0004867415598844

61.

KalmbachDAPillaiVChengPArnedtJTDrakeCL. Shift work disorder, depression, and anxiety in the transition to rotating shifts: the role of sleep reactivity. Sleep Med. (2015) 16:1532–8. 10.1016/j.sleep.2015.09.007

62.

NguyenCMurrayGAndersonSFilipowiczAIngramKK. In vivo molecular chronotyping, circadian misalignment, and high rates of depression in young adults. J Affect Disord. (2019) 250:425–31. 10.1016/j.jad.2019.03.050

63.

MurrayJMSlettenTLMageeMGordonCLovatoNBartlettDJet al. Prevalence of circadian misalignment and its association with depressive symptoms in delayed sleep phase disorder. Sleep. (2017) 40:zsw002. 10.1093/sleep/zsw002

64.

RobillardRCarpenterJSFeildsKLHermensDFWhiteDNaismithSLet al. Parallel changes in mood and melatonin rhythm following an adjunctive multimodal chronobiological intervention with agomelatine in people with depression: a proof of concept open label study. Front Psychiatry. (2018) 9:624. 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00624

65.

RobillardRNaismithSLRogersNLScottEMIpTKHermensDFet al. Sleep-wake cycle and melatonin rhythms in adolescents and young adults with mood disorders: comparison of unipolar and bipolar phenotypes. Eur Psychiatry. (2013) 28:412–6. 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2013.04.001

66.

SalvatorePGhidiniSZitaGDe PanfilisCLambertinoSMagginiCet al. Circadian activity rhythm abnormalities in ill and recovered bipolar I disorder patients. Bipolar Disord. (2008) 10:256–65. 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00505.x

67.

GonzalezRTammingaCATohenMSuppesT. The relationship between affective state and the rhythmicity of activity in bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. (2014) 75:e317–22. 10.4088/JCP.13m08506

68.

WehrTA. Bipolar mood cycles and lunar tidal cycles. Mol Psychiatry. (2018) 23:923–31. 10.1038/mp.2016.263

69.

KripkeDFNievergeltCMJooEShekhtmanTKelsoeJR. Circadian polymorphisms associated with affective disorders. J Circadian Rhythms. (2009) 7:2. 10.1186/1740-3391-7-2

70.

LeeKYSongJYKimSHKimSCJooEJAhnYMet al. Association between CLOCK 3111T/C and preferred circadian phase in Korean patients with bipolar disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. (2010) 34:1196–201. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.06.010

71.

DrennanMDKlauberMRKripkeDFGoyetteLM. The effects of depression and age on the Horne-Ostberg morningness-eveningness score. J Affect Disord. (1991) 23:93–8. 10.1016/0165-0327(91)90096-B

72.

MaruaniJGeoffroyPA. Bright light as a personalized precision treatment of mood disorders. Front Psychiatry. (2019) 10:85. 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00085

73.

ParkHLeeHKLeeK. Chronotype and suicide: the mediating effect of depressive symptoms. Psychiatry Res. (2018) 269:316–20. 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.08.046

74.

StangeJPKleimanEMSylviaLGMagalhãesPVBerkMNierenbergAAet al. Specific mood symptoms confer risk for subsequent suicidal ideation in bipolar disorder with and without suicide attempt history: multi-wave data from step-BD. Depress Anxiety. (2016) 33:464–72. 10.1002/da.22464

75.

CretuJBCulverJLGoffinKCShahSKetterTA. Sleep, residual mood symptoms, and time to relapse in recovered patients with bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. (2016) 190:162–6. 10.1016/j.jad.2015.09.076

76.

WichniakAWierzbickaAJernajczykW. Sleep as a biomarker for depression. Int Rev Psychiatry. (2013) 25:632–45. 10.3109/09540261.2013.812067

77.

RitterPSHöflerMWittchenHULiebRBauerMPfennigAet al. Disturbed sleep as risk factor for the subsequent onset of bipolar disorder–data from a 10-year prospective-longitudinal study among adolescents and young adults. J Psychiatr Res. (2015) 68:76–82. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2015.06.005

78.

ChangPPFordDEMeadLACooper-PatrickLKlagMJ. Insomnia in young men and subsequent depression. The Johns Hopkins Precursors Study. Am J Epidemiol. (1997) 146:105–14. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009241

79.

BuysseDJAngstJGammaAAjdacicVEichDRösslerW. Prevalence, course, and comorbidity of insomnia and depression in young adults. Sleep. (2008) 31:473–80. 10.1093/sleep/31.4.473

80.

ArentCOValvassoriSSSteckertAVResendeWRDal-PontGCLopes-BorgesJet al. The effects of n-acetylcysteine and/or deferoxamine on manic-like behavior and brain oxidative damage in mice submitted to the paradoxal sleep deprivation model of mania. J Psychiatr Res. (2015) 65:71–9. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2015.04.011

81.

Lopez-RodriguezFKimJPolandRE. Total sleep deprivation decreases immobility in the forced-swim test. Neuropsychopharmacology. (2004) 29:1105–11. 10.1038/sj.npp.1300406

82.

ZhangBGaoYLiYYangJZhaoH. Sleep deprivation influences circadian gene expression in the lateral habenula. Behav Neurol. (2016) 2016:7919534. 10.1155/2016/7919534

83.

TermanMTermanJS. Light therapy for seasonal and nonseasonal depression: efficacy, protocol, safety, and side effects. CNS Spectr. (2005) 10:647–63;quiz 672. 10.1017/S1092852900019611

84.

HenriksenTESkredeSFasmerOBHamreBGrønliJLundA. Blocking blue light during mania - markedly increased regularity of sleep and rapid improvement of symptoms: a case report. Bipolar Disord. (2014) 16:894–8. 10.1111/bdi.12265

85.

YokotaHVijayasarathiACekicMHirataYLinetskyMHoMet al. Diagnostic performance of glymphatic system evaluation using diffusion tensor imaging in idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus and mimickers. Curr Gerontol Geriatr Res. (2019) 2019:5675014. 10.1155/2019/5675014

86.

ScottFFBelleMDDelagrangePPigginsHD. Electrophysiological effects of melatonin on mouse Per1 and non-Per1 suprachiasmatic nuclei neurones in vitro. J Neuroendocrinol. (2010) 22:1148–56. 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2010.02063.x

87.

AntleMCOgilvieMDPickardGEMistlbergerRE. Response of the mouse circadian system to serotonin 1A/2/7 agonists in vivo: surprisingly little. J Biol Rhythms. (2003) 18:145–58. 10.1177/0748730403251805

88.

DudleyTEDiNardoLAGlassJD. Endogenous regulation of serotonin release in the hamster suprachiasmatic nucleus. J Neurosci. (1998) 18:5045–52. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-13-05045.1998

89.

SpencerSFalconEKumarJKrishnanVMukherjeeSBirnbaumSGet al. Circadian genes Period 1 and Period 2 in the nucleus accumbens regulate anxiety-related behavior. Eur J Neurosci. (2013) 37:242–50. 10.1111/ejn.12010

90.

DuncanWCJr.SlonenaEHejaziNSBrutscheNYuKCParkLet al. Motor-activity markers of circadian timekeeping are related to ketamine's rapid antidepressant properties. Biol Psychiatry. (2017) 82:361–9. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.03.011

91.

KripkeDFJuddLLHubbardBJanowskyDSHueyLY. The effect of lithium carbonate on the circadian rhythm of sleep in normal human subjects. Biol Psychiatry. (1979) 14:545–8.

92.

WelshDKMoore-EdeMC. Lithium lengthens circadian period in a diurnal primate, Saimiri sciureus. Biol Psychiatry. (1990) 28:117–26. 10.1016/0006-3223(90)90629-G

93.

LiJLuWQBeesleySLoudonASMengQJ. Lithium impacts on the amplitude and period of the molecular circadian clockwork. PLoS ONE. (2012) 7:e33292. 10.1371/journal.pone.0033292

94.

SchnellASandrelliFRancVRippergerJABraiEAlberiLet al. Mice lacking circadian clock components display different mood-related behaviors and do not respond uniformly to chronic lithium treatment. Chronobiol Int. (2015) 32:1075–89. 10.3109/07420528.2015.1062024

95.

IwahashiKNishizawaDNaritaSNumajiriMMurayamaOYoshiharaEet al. Haplotype analysis of GSK-3β gene polymorphisms in bipolar disorder lithium responders and nonresponders. Clin Neuropharmacol. (2014) 37:108–10. 10.1097/WNF.0000000000000039

96.

AuklandKReedRK. Interstitial-lymphatic mechanisms in the control of extracellular fluid volume. Physiol Rev. (1993) 73:1–78. 10.1152/physrev.1993.73.1.1

97.

LouveauAPlogBAAntilaSAlitaloKNedergaardMKipnisJ. Understanding the functions and relationships of the glymphatic system and meningeal lymphatics. J Clin Invest. (2017) 127:3210–9. 10.1172/JCI90603

98.

MestreHTithofJDuTSongWPengWSweeneyAMet al. Flow of cerebrospinal fluid is driven by arterial pulsations and is reduced in hypertension. Nat Commun. (2018) 9:4878. 10.1038/s41467-018-07318-3

99.

ReyJSarntinoranontM. Pulsatile flow drivers in brain parenchyma and perivascular spaces: a resistance network model study. Fluids Barriers CNS. (2018) 15:20. 10.1186/s12987-018-0105-6

100.

TithofJKelleyDHMestreHNedergaardMThomasJH. Hydraulic resistance of periarterial spaces in the brain. Fluids Barriers CNS. (2019) 16:19. 10.1186/s12987-019-0140-y

101.

KoundalSElkinRNadeemSXueYConstantinouSSanggaardSet al. Optimal mass transport with Lagrangian workflow reveals advective and diffusion driven solute transport in the glymphatic system. Sci Rep. (2020) 10:1990. 10.1038/s41598-020-59045-9

102.

ThomasJH. Fluid dynamics of cerebrospinal fluid flow in perivascular spaces. J R Soc Interface. (2019) 16:20190572. 10.1098/rsif.2019.0572

103.

MestreHMoriYNedergaardM. The brain's glymphatic system: current controversies. Trends Neurosci. (2020) 43:458–66. 10.1016/j.tins.2020.04.003

104.

RayLIliffJJHeysJJ. Analysis of convective and diffusive transport in the brain interstitium. Fluids Barriers CNS. (2019) 16:6. 10.1186/s12987-019-0126-9

105.

KiviniemiVWangXKorhonenVKeinänenTTuovinenTAutioJet al. Ultra-fast magnetic resonance encephalography of physiological brain activity - glymphatic pulsation mechanisms?J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. (2016) 36:1033–45. 10.1177/0271678X15622047

106.

ChristensenJYamakawaGRShultzSRMychasiukR. Is the glymphatic system the missing link between sleep impairments and neurological disorders? Examining the implications and uncertainties. Prog Neurobiol. (2021) 198:101917. 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2020.101917

107.

MaQRiesMDeckerYMüllerARinerCBückerAet al. Rapid lymphatic efflux limits cerebrospinal fluid flow to the brain. Acta Neuropathol. (2019) 137:151–65. 10.1007/s00401-018-1916-x

108.

AhnJHChoHKimJHKimSHHamJSParkIet al. Meningeal lymphatic vessels at the skull base drain cerebrospinal fluid. Nature. (2019) 572:62–6. 10.1038/s41586-019-1419-5

109.

WangLZhangYZhaoYMarshallCWuTXiaoM. Deep cervical lymph node ligation aggravates AD-like pathology of APP/PS1 mice. Brain Pathol. (2019) 29:176–92. 10.1111/bpa.12656

110.

Da MesquitaSLouveauAVaccariASmirnovICornelisonRCKingsmoreKMet al. Functional aspects of meningeal lymphatics in ageing and Alzheimer's disease. Nature. (2018) 560:185–91. 10.1038/s41586-018-0368-8

111.

MestreHHablitzLMXavierALFengWZouWPuTet al. Aquaporin-4-dependent glymphatic solute transport in the rodent brain. Elife. (2018) 7:e40070. 10.7554/eLife.40070

112.

Tarasoff-ConwayJMCarareROOsorioRSGlodzikLButlerTet al. Clearance systems in the brain-implications for Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurol. (2015) 11:457–70. 10.1038/nrneurol.2015.119

113.

XuZXiaoNChenYHuangHMarshallCGaoJet al. Deletion of aquaporin-4 in APP/PS1 mice exacerbates brain Aβ accumulation and memory deficits. Mol Neurodegener. (2015) 10:58. 10.1186/s13024-015-0056-1

114.

SmithAJYaoXDixJAJinBJVerkmanAS. Test of the 'glymphatic' hypothesis demonstrates diffusive and aquaporin-4-independent solute transport in rodent brain parenchyma. Elife. (2017) 6:e27679. 10.7554/eLife.27679

115.

CaiXQiaoJKulkarniPHardingICEbongEFerrisCF. Imaging the effect of the circadian light-dark cycle on the glymphatic system in awake rats. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. (2020) 117:668–76. 10.1073/pnas.1914017117

116.

HablitzLMPláVGiannettoMVinitskyHSStægerFFMetcalfeTet al. Circadian control of brain glymphatic and lymphatic fluid flow. Nat Commun. (2020) 11:4411. 10.1038/s41467-020-18115-2

117.

CederrothCRAlbrechtUBassJBrownSADyhrfjeld-JohnsenJGachonFet al. Medicine in the fourth dimension. Cell Metab. (2019) 30:238–50. 10.1016/j.cmet.2019.06.019

118.

SimaskoSMMukherjeeS. Novel analysis of sleep patterns in rats separates periods of vigilance cycling from long-duration wake events. Behav Brain Res. (2009) 196:228–36. 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.09.003

119.

Ulv LarsenSMLandoltHPBergerWNedergaardMKnudsenGMHolstSC. Haplotype of the astrocytic water channel AQP4 is associated with slow wave energy regulation in human NREM sleep. PLoS Biol. (2020) 18:e3000623. 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000623

120.

BrancaccioMPattonAPCheshamJEMaywoodESHastingsMH. Astrocytes control circadian timekeeping in the suprachiasmatic nucleus via glutamatergic signaling. Neuron. (2017) 93:1420.e5–35.e5. 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.02.030

121.

MirzaSSWoltersFJSwansonSAKoudstaalPJHofmanATiemeierHet al. 10-year trajectories of depressive symptoms and risk of dementia: a population-based study. Lancet Psychiatry. (2016) 3:628–35. 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)00097-3

122.

WuKYLiuCYChenCSChenCHHsiaoITHsiehCJet al. Beta-amyloid deposition and cognitive function in patients with major depressive disorder with different subtypes of mild cognitive impairment: (18)F-florbetapir (AV-45/Amyvid) PET study. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. (2016) 43:1067–76. 10.1007/s00259-015-3291-3

123.

GongYSunX-LWuF-FSuC-JDingJ-HHuG. Female early adult depression results in detrimental impacts on the behavioral performance and brain development in offspring. CNS Neurosci Ther. (2012) 18:461–70. 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2012.00324.x

124.

CzéhBSimonMSchmeltingBHiemkeCFuchsE. Astroglial plasticity in the hippocampus is affected by chronic psychosocial stress and concomitant fluoxetine treatment. Neuropsychopharmacology. (2006) 31:1616–26. 10.1038/sj.npp.1300982

125.

KinoshitaMHirayamaYFujishitaKShibataKShinozakiYShigetomiE. Anti-depressant fluoxetine reveals its therapeutic effect via astrocytes. EBioMedicine. (2018) 32:72–83. 10.1016/j.ebiom.2018.05.036

126.

Hisaoka-NakashimaKTakiSWatanabeSNakamuraYNakataYMoriokaN. Mirtazapine increases glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor production through lysophosphatidic acid 1 receptor-mediated extracellular signal-regulated kinase signaling in astrocytes. Eur J Pharmacol. (2019) 860:172539. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2019.172539

127.

WangYXieLGaoCZhaiLZhangNGuoL. Astrocytes activation contributes to the antidepressant-like effect of ketamine but not scopolamine. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. (2018) 170:1–8. 10.1016/j.pbb.2018.05.001

128.

LasičELisjakMHorvatABoŽićMŠakanovićAAnderluhGet al. Astrocyte specific remodeling of plasmalemmal cholesterol composition by ketamine indicates a new mechanism of antidepressant action. Sci Rep. (2019) 9:10957. 10.1038/s41598-019-47459-z

129.

XueS-SXueFMaQ-RWangS-QWangYTanQ-Ret al. Repetitive high-frequency transcranial magnetic stimulation reverses depressive-like behaviors and protein expression at hippocampal synapses in chronic unpredictable stress-treated rats by enhancing endocannabinoid signaling. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. (2019) 184:172738. 10.1016/j.pbb.2019.172738

130.

TalerMAronovichRHenry HornfeldSDarSSassonEWeizmanAet al. Regulatory effect of lithium on hippocampal blood-brain barrier integrity in a rat model of depressive-like behavior. Bipolar Disord. (2020) 23:55–65. 10.1111/bdi.12962

131.

WangYNiJZhaiLGaoCXieLZhaoLet al. Inhibition of activated astrocyte ameliorates lipopolysaccharide- induced depressive-like behaviors. J Affect Disord. (2019) 242:52–9. 10.1016/j.jad.2018.08.015

132.

PortalBDelcourteSRoveraRLejardsCBullichSMalnouCEet al. Genetic and pharmacological inactivation of astroglial connexin 43 differentially influences the acute response of antidepressant and anxiolytic drugs. Acta Physiol. (Oxf). 2020:e13440. 10.1111/apha.13440

133.

KongHShaLLFanYXiaoMDingJHWuJHuG. Requirement of AQP4 for antidepressive efficiency of fluoxetine: implication in adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Neuropsychopharmacology. (2009) 34:1263–76. 10.1038/npp.2008.185

134.

HughesTMKullerLHBarinas-MitchellEJMackeyRHMcDadeEMKlunkWEet al. Pulse wave velocity is associated with β-amyloid deposition in the brains of very elderly adults. Neurology. (2013) 81:1711–8. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000435301.64776.37

135.

GosTSchroeterMLLesselWBernsteinH-GDobrowolnyHSchiltzKet al. S100B-immunopositive astrocytes and oligodendrocytes in the hippocampus are differentially afflicted in unipolar and bipolar depression: a postmortem study. J Psychiatr Res. (2013) 47:1694–9. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.07.005

136.

MedinaAWatsonSJBunneyWJrMyersRMSchatzbergABarchasJet al. Evidence for alterations of the glial syncytial function in major depressive disorder. J Psychiatr Res. (2016) 72:15–21. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2015.10.010

137.

FerestenAHBarakauskasVYpsilantiABarrAMBeasleyCL. Increased expression of glial fibrillary acidic protein in prefrontal cortex in psychotic illness. Schizophr Res. (2013) 150:252–7. 10.1016/j.schres.2013.07.024

138.

Johnston-WilsonNLSimsCDHofmannJPAndersonLShoreADTorreyEFet al. Disease-specific alterations in frontal cortex brain proteins in schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder. The Stanley Neuropathology Consortium. Mol Psychiatry. (2000) 5:142–9. 10.1038/sj.mp.4000696

139.

ToroCTHallakJEDunhamJSDeakinJF. Glial fibrillary acidic protein and glutamine synthetase in subregions of prefrontal cortex in schizophrenia and mood disorder. Neurosci Lett. (2006) 404:276–81. 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.05.067

140.

DeanBGrayLScarrE. Regionally specific changes in levels of cortical S100beta in bipolar 1 disorder but not schizophrenia. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. (2006) 40:217–24. 10.1111/j.1440-1614.2006.01777.x

141.

HercherCChopraVBeasleyCL. Evidence for morphological alterations in prefrontal white matter glia in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. J Psychiatry Neurosci. (2014) 39:376–85. 10.1503/jpn.130277

142.

WilliamsMRHamptonTPearceRKBHirschSRAnsorgeOThomMet al. Astrocyte decrease in the subgenual cingulate and callosal genu in schizophrenia. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. (2013) 263:41–52. 10.1007/s00406-012-0328-5

143.

PantazopoulosHWooT-UWLimMPLangeNBerrettaS. Extracellular matrix-glial abnormalities in the amygdala and entorhinal cortex of subjects diagnosed with schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (2010) 67:155–66. 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.196

144.

MalchowBStrockaSFrankFBernsteinH-GSteinerJSchneider-AxmannTet al. Stereological investigation of the posterior hippocampus in affective disorders. J Neural Transm (Vienna). (2015) 122:1019–33. 10.1007/s00702-014-1316-x

145.

BarleyKDrachevaSByneW. Subcortical oligodendrocyte- and astrocyte-associated gene expression in subjects with schizophrenia, major depression and bipolar disorder. Schizophr Res. (2009) 112:54–64. 10.1016/j.schres.2009.04.019

146.

FatemiSHLaurenceJAAraghi-NiknamMStaryJMSchulzSCLeeSet al. Glial fibrillary acidic protein is reduced in cerebellum of subjects with major depression, but not schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. (2004) 69:317–23. 10.1016/j.schres.2003.08.014

147.

SteinerJBielauHBrischRDanosPUllrichOMawrinCet al. Immunological aspects in the neurobiology of suicide: elevated microglial density in schizophrenia and depression is associated with suicide. J Psychiatr Res. (2008) 42:151–7. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.10.013

148.

da RosaMISimonCGrandeAJBarichelloTOsesJPQuevedoJ. Serum S100B in manic bipolar disorder patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. (2016) 206:210–5. 10.1016/j.jad.2016.07.030

149.

IwamotoKKakiuchiCBundoMIkedaKKatoT. Molecular characterization of bipolar disorder by comparing gene expression profiles of postmortem brains of major mental disorders. Mol Psychiatry. (2004) 9:406–6. 10.1038/sj.mp.4001437

150.

WooT-UWWalshJPBenesFM. Density of glutamic acid decarboxylase 67 messenger RNA-containing neurons that express the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor subunit NR2A in the anterior cingulate cortex in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (2004) 61:649–57. 10.1001/archpsyc.61.7.649

151.

SeredeninaTSorceSHerrmannFRMa MuloneXJPlastreOAguzziAet al. Decreased NOX2 expression in the brain of patients with bipolar disorder: association with valproic acid prescription and substance abuse. Transl Psychiatry. (2017) 7:e1206. 10.1038/tp.2017.175

152.

HarrisonPJGeddesJRTunbridgeEM. The emerging neurobiology of bipolar disorder. Trends Neurosci. (2018) 41:18–30. 10.1016/j.tins.2017.10.006

153.

HuberVJTsujitaMKweeILNakadaT. Inhibition of aquaporin 4 by antiepileptic drugs. Bioorg Med Chem. (2009) 17:418–24. 10.1016/j.bmc.2007.12.038

154.

MortonEMurrayG. An update on sleep in bipolar disorders: presentation, comorbidities, temporal relationships and treatment. Curr Opin Psychol. (2020) 34:1–6. 10.1016/j.copsyc.2019.08.022

155.

ZeppenfeldDMSimonMHaswellJDD'AbreoDMurchisonCQuinnJFet al. Association of perivascular localization of aquaporin-4 with cognition and alzheimer disease in aging brains. JAMA Neurol. (2017) 74:91–9. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.4370

Summary

Keywords

glymphatic system, depression, sleep, bipolar disorder, astrocyte, aquaporin-4

Citation

Yan T, Qiu Y, Yu X and Yang L (2021) Glymphatic Dysfunction: A Bridge Between Sleep Disturbance and Mood Disorders. Front. Psychiatry 12:658340. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.658340

Received

25 January 2021

Accepted

12 April 2021

Published

07 May 2021

Volume

12 - 2021

Edited by

Sarah Jane Baracz, University of New South Wales, Australia

Reviewed by

Casimiro Cabrera Abreu, Queens University, Canada; Jennaya Christensen, Monash University, Australia

Updates

Copyright

© 2021 Yan, Qiu, Yu and Yang.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xinfeng Yu yuxinfeng@zju.edu.cnLinglin Yang 2517106@zju.edu.cn; yang_linglin@163.com

This article was submitted to Mood and Anxiety Disorders, a section of the journal Frontiers in Psychiatry

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.