- 1Department of Paediatrics, Melbourne Medical School, Faculty of Medicine, Dentistry and Health Sciences, University of Melbourne, Parkville, VIC, Australia

- 2Centre for Adolescent Health Royal Children’s Hospital, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

- 3Murdoch Childrens Research Institute, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

- 4Faculty of Psychology, Universitas Airlangga, Surabaya, East Java, Indonesia

- 5Adolescent Health and Wellbeing, Telethon Kids Institute, Adelaide, Australia

- 6School of Public Health and Preventive Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Nursing & Health Sciences, Monash University, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

Objectives: Schools are increasingly recognized as important settings for mental health promotion, but it is unclear what actions schools should prioritize to promote student mental health and wellbeing. We undertook a policy review of global school-based mental health promotion policy documents from United Nations (UN) agencies to understand the frameworks they use and the actions they recommend for schools.

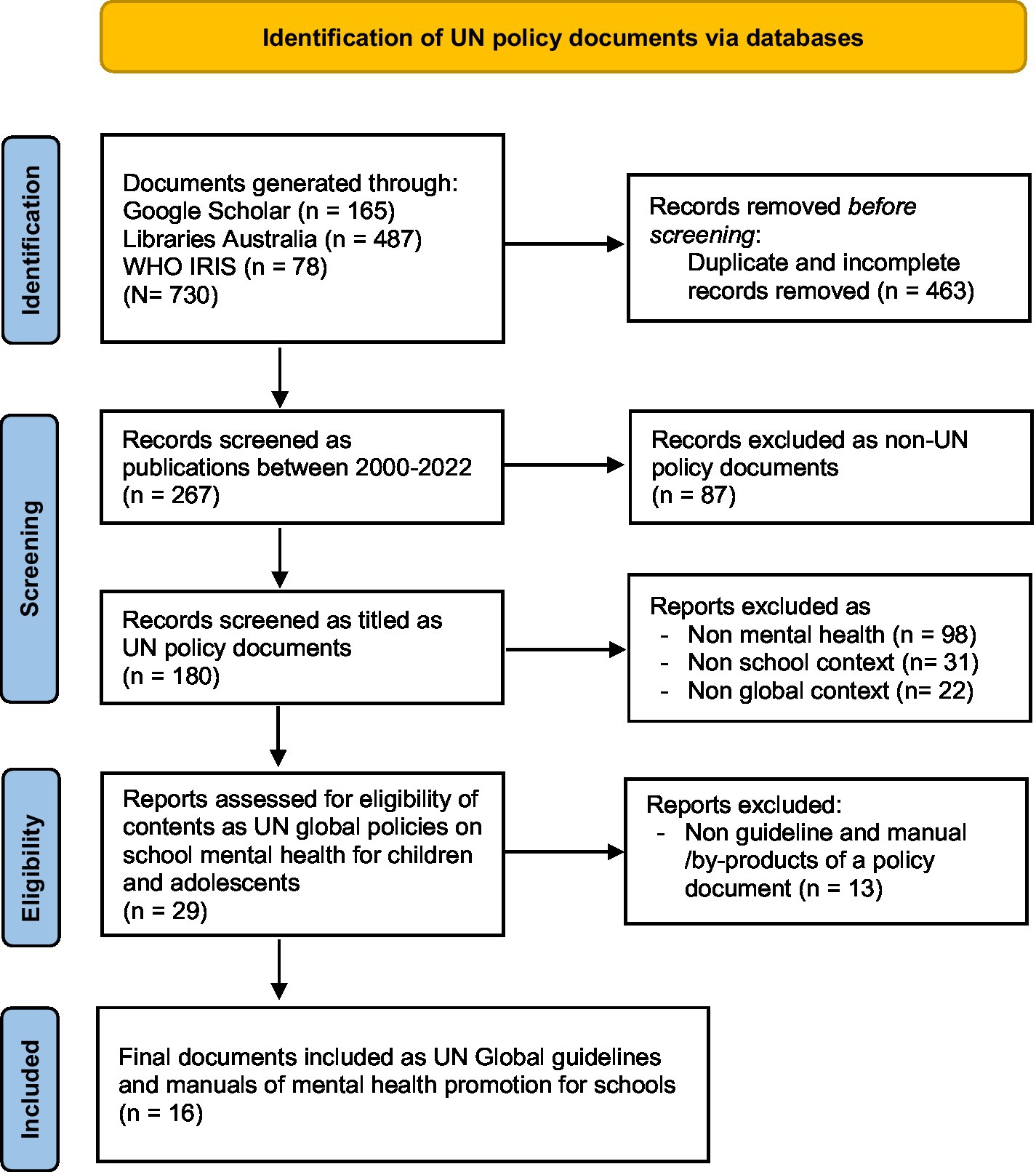

Methods: We searched for guidelines and manuals from UN agencies through the World Health Organization (WHO) library, the National Library of Australia and Google Scholar, from 2000 to 2021, using various combinations of search terms (e.g., mental health, wellbeing, psychosocial, health, school, framework, manual, and guidelines). Textual data synthesis was undertaken.

Results: Sixteen documents met inclusion criteria. UN policy documents commonly recommended a comprehensive school-health framework aimed at integrating actions to prevent, promote, and support mental health problems within the school community. The primary role of schools was framed around building enabling contexts for mental health and wellbeing. Terminology was relatively inconsistent across different guidelines and manuals, particularly around how comprehensive school health was conceptualized, which included aspects of scope, focus, and approach.

Conclusion: United Nations policy documents are oriented toward comprehensive school-health frameworks for student mental health and wellbeing that include mental health within wider health-promoting approaches. There are expectations that schools have the capabilities to deliver actions to prevent, promote and support mental health problems.

Implication: Effective implementation of school-based mental health promotion requires investments that facilitate specific actions from governments, schools, families, and communities.

Background

Mental health and wellbeing are recognized as major contemporary public health challenges, including in school-age children and adolescents (1–4). Students with mental health disorders are also appreciated to have poorer academic attainment, which suggests that addressing mental health and wellbeing is important for both health and education outcomes (5–7). In this context, schools are expected to act as settings that can deliver actions to promote positive mental health and wellbeing, prevent mental disorders, as well as manage student mental health needs, including identification, referral, and provision of support (8–11).

Guidelines and manuals can assist schools to develop their capacity to identify, prioritize, and deliver evidence-based, feasible, and contextualized approaches to mental health promotion for children and adolescents. Over the past few decades, various policies, guidelines, and manuals have been developed by governmental and non-governmental organizations at national, regional, and international levels. Globally, the United Nations (UN) agencies have maintained focus on promoting adolescent mental health and wellbeing among its member states by documenting policies in the form of guidelines and manuals. Several UN agency guidelines address mental health within broader approaches to school-health services or health promotion in schools, such as the World Health Organization (WHO) Global School Health Initiative, which first developed guidelines for Health-Promoting Schools in 1995 (12–14) and more recently developed global standards and indicators for Health-promoting Schools and an accompanying implementation guidance (15, 16). Other policies specifically focus on mental health and include the value of orienting member states and national governing bodies toward more preventive and promotive approaches to mental health and wellbeing in schools. This includes efforts by the United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) and United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) that require schools to assist students to develop appropriate social and emotional skills and engage in positive classroom behaviors (17, 18).

These UN policy documents are intended to serve as references for implementation but risk being inhibited by several challenges. First, each UN agency’s documents potentially speak to different audiences and sectors. UNICEF, for example, primarily speaks to social protection audiences, while UNESCO targets the education sector, and WHO is oriented to the health sector. Further uncertainty is around the extent to which these documents use common frameworks or approaches toward school-based mental health promotion. An additional challenge is that the language of “social and emotional wellbeing” is more typically used by the education sector than “mental health,” which is more commonly used by the health sector. These factors may lead to difficulties aligning different documents and inadvertently contribute to unclear expectations of schools’ roles in promoting mental health and wellbeing.

Given the potential breadth of this policy landscape and the implications of this for the multiple actions that schools could potentially take to promote mental health and wellbeing, we set out to identify what mental health promotion frameworks are used within the various global guidelines and manuals of school-based mental health promotion with the objective of understanding the specific actions schools can take to promote student mental health and wellbeing. Specifically, this study aimed to address two research questions: (1) To what extent are common frameworks used across the UN agency guidelines and manuals that are relevant for school-based mental health promotion? and (2) How should schools facilitate mental health promotion? We undertook a policy review that aimed to synthesize the key recommendations within global manuals and guidelines to develop an integrated understanding of the potential role of schools in promoting the mental health and wellbeing of school-age students.

Methods

We set out to review all UN agency manuals and guidelines of relevance to school-based mental health promotion. In this context, we defined a guideline as a report that consists of general principles that provide assistance in making decisions for specific circumstances or that give direction in setting standards or determining a course of action (19, 20). We defined a manual as a collection of instructions on how to perform an activity, which generally serves as a more practical resource or reference (21). The production of school mental health guidelines and manuals is a public health policy approach used by UN agencies; such documents are widely acknowledged for their credibility, practicality, and global relevance, both for high-income countries (HIC) and low-middle-income countries (LMIC). For this reason, this study focused on identifying UN agencies’ manuals and guidelines that were intended to be globally relevant.

Search strategy

Given our interest in scoping globally relevant manuals and guidelines intended to support mental health promotion in schools (22), we searched for reports from Google Scholar, through the National Library of Australia1 and using the Institutional Repository for Informational Sharing–World Health Organization (WHO-IRIS) library for documents published by the relevant UN agencies over the last two decades. We searched through WHO-IRIS as most health-related policy documents are stored in this platform, regardless of the UN agency that produces them. We aimed to identify reports published from 2000 to 2021, inclusive. One reviewer conducted the search between 1 May 2021 and 16 May 2022. The search strategy used a combination of the following terms: “mental health,” “wellbeing,” “psychosocial,” “health,” “mental disorder,” “mental illness,” “school,” “education,” “school health,” “children,” adolescent,” “manual,” “guidelines,” “policy,” and “framework” (see Supplementary Box S1 for the search strategy).

Eligibility criteria

We defined eligible documents as any UN agency guideline and manual on school-based mental health promotion published in English from 2000 to 2021. We excluded technical reports, country-level reports, regional-level reports, meeting reports, statistical reports, epidemiological reports, media resources, research papers, reviews of studies, editorials, books or codex, non-English texts, academic theses, and other texts.

Textual data analysis

The Joanna Briggs Institute’s guidance for synthesizing evidence from narrative, text, and opinion-based evidence was used for data synthesis for this policy review. Specifically, data synthesis was undertaken using a three-step categorization strategy, as detailed in McArthur (23). The first step is the conclusion process, where a conclusion for each document is generated to answer a research question. The second step is the categorization process, in which the reviewers read all conclusions and identify similarities that could be used to create one or more categories encompassing the various findings from the first step. The third step involves synthesizing findings, where the reviewers undertake a meta-synthesis of all categorized findings. The synthesizing is based on their expert opinion for generating a set of comprehensive statements that resemble important information in the review. The textual analytic process was generated into the NOTARI view for tabulation, which sorts conclusions and categorizations within their unitary synthesized finding to adequately represent the data (23).

We used the multi-tiered model of school-based mental health intervention as the framework for data extraction (9). The reasons for this are that: it has a long history of use; is relevant for both the education and health sector workforces across primary and secondary schools; and has the broadest scope (it addresses mental health needs that range from health promotion of relevance to the entire student body, to more targeted approaches for those at risk, as well as specific responses for the minority with a clinical diagnosis of mental disorder) (9, 24).

Results

The search identified 730 records, from which 16 globally relevant manuals and guidelines were included in the final policy review. Figure 1 outlines the search process referring to the PRISMA flow diagram (25), and the selected documents are listed in Supplementary Box S2. The largest number of reports (n = 12) came from WHO, with others from UNESCO, UNICEF, and collaborations of several UN agencies and their partners. A summary of relevant findings from these documents are listed in Table 1. These 16 globally oriented mental health policy documents span a wide scope of school-based mental health promotion, ranging from those that focus on universal or population approaches to health promotion to more selective and indicated interventions.

Table 1. Summary of relevant findings from the included UN agencies’ policy documents on school-based mental health promotion.

Seven different global school mental health policy approaches were identified: (1) Health-promoting Schools, a Global School Health Initiative from WHO that has recently been widely endorsed by other UN agencies, most notably UNESCO (13, 15); (2) the Child-Friendly Schools initiative from UNICEF (18); (3) the inter-agency initiative of Focusing Resources for Effective School Health (FRESH), from which the renewed focus on Health-promoting Schools has also emerged (17); (4) the INSPIRE Seven strategies for ending violence against children (26); (5) the Mental Health Gap Action Programme (27); (6) Accelerated Action for the Health of Adolescents from WHO (28); and (7) Helping Adolescents Thrive, a UN multiagency initiative (29). Three of these seven policy approaches were designed for schools and explicitly promoted a comprehensive school-health framework that acknowledges the importance of addressing mental health within a wider scope of health topics (13, 17, 18). The remaining four also acknowledge the importance of schools in attending to diverse health needs.

As might be expected, several of these policy documents show evidence of progression over time. For example, the WHO’s Health-promoting Schools framework shows progress from its early conceptualization in 2000 (13) into a set of eight global standards and indicators (15). Likewise, UNESCO’s FRESH progressed from an earlier guideline in 2002 (17) that advanced assessment strategies and tools by including detailed monitoring and evaluation guidelines in 2013 (30). There is also increasing evidence of inter-agency engagement. For example, the approach of Health-promoting Schools was first developed by WHO but has been redeveloped and co-branded with UNESCO (13, 16). Similarly, mhGAP-IG 2.0 (31) is the latest guideline and manual from WHO for reducing mental, neurological, and substance use disorders that follows earlier guidelines on the Mental Health Gap Action Program from 2008 and 2010 (32, 33).

Commonalities within the global manuals and guidelines

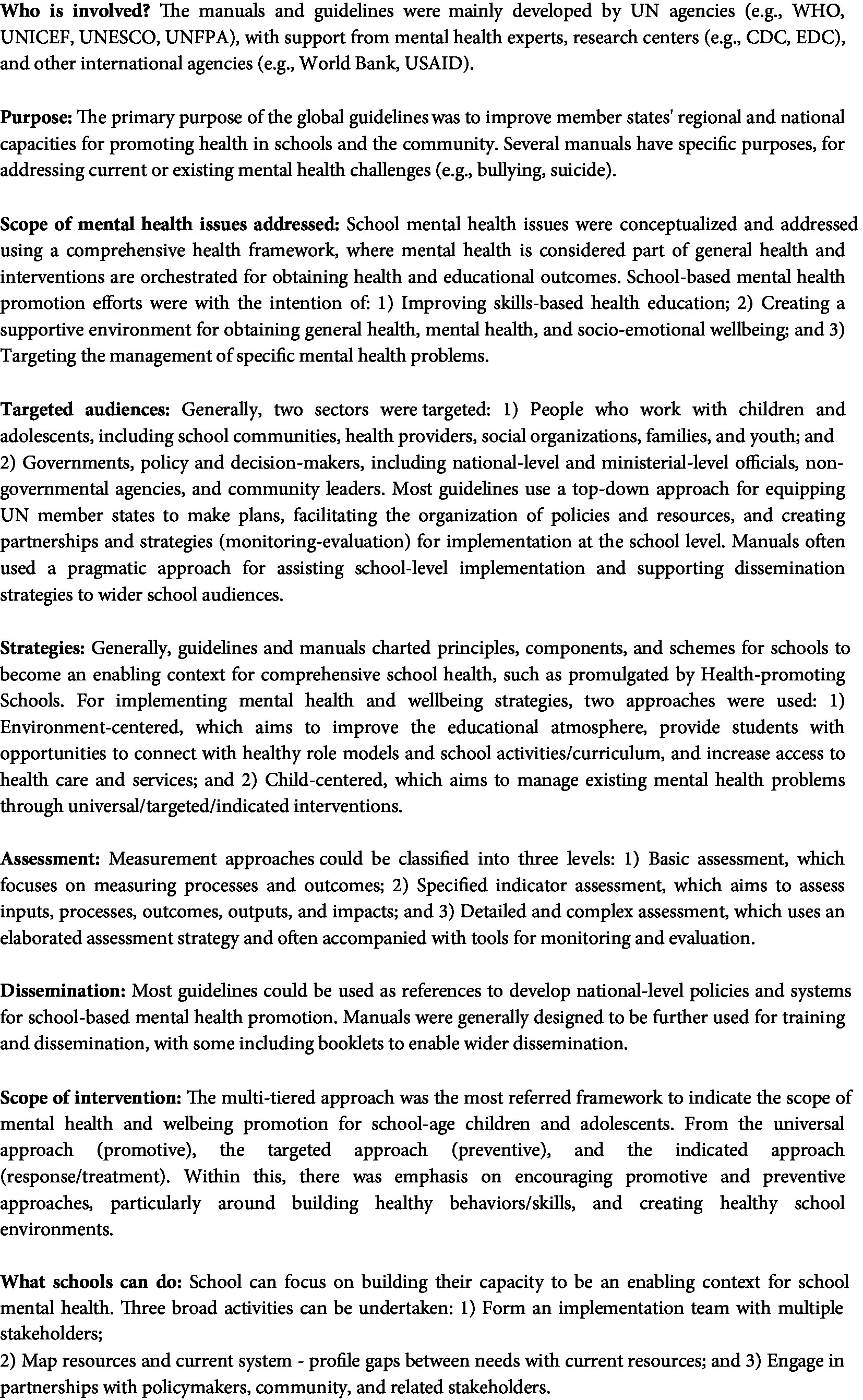

In general, we found much in common across these UN global policy documents (see Figure 2 for a summary of key points). UN policies on school-based mental health were predominantly oriented around a comprehensive school-health framework that is intended to holistically improve the health and wellbeing of all school community members, including students and teachers, as well as the wider community. Another common element within this framework is the recognition that collaboration between schools, governments, families, communities, and related stakeholders is required to implement comprehensive approaches to mental health promotion in schools.

Several manuals were developed to address more specific challenges facing schools and their communities, such as youth suicide (34), violence against children (26, 35, 36), and crisis interventions (37). We found that both generic mental health promotion documents and these more specific documents promote a comprehensive framework and acknowledge the diversity of mental health needs within any school community (13, 15–18, 38, 39). There are also clear expectations that schools are able to attend to a wide array of mental health needs within the school community. Schools are also expected to have the capacity to intervene when required to manage more specific mental health concerns, either for individuals (e.g., depression) or around common issues for a school community (e.g., climate crisis anxiety) (37, 40). The importance of a school’s social environment for mental health was also recognized (18, 41, 42). Schools are encouraged to facilitate preventive and promotive approaches through developing healthy social environments and providing activities to improve students’ mental health literacy and communication skills (43).

Another common feature was that these guidelines and manuals explicitly require the involvement of multiple stakeholders including school administrators, government organizations, community, and non-government organizations (NGOs). This requires action by schools to develop or improve functional networks with relevant related stakeholders, particularly governments and communities.

United Nations guidelines are intended to assist national and local governments to make plans, facilitate policies and supplies, and generate coordination and monitoring strategies. Consistent with this, several guidelines used a “top-down approach,” which was particularly evident around UN member states’ commitment to national school-health plans (15, 44, 45). In comparison, manuals are designed for more practical purposes and targeted schools themselves, with the goal of providing schools with tools that might assist them to implement mental health promotion programs (34, 42).

The manuals and guidelines clearly outlined principles, mechanisms, and systems for schools to promote health comprehensively and identified inclusive strategies to address mental health and wellbeing. Part of the comprehensiveness of the framework is that strategies for promoting mental health and wellbeing spanned from preventively oriented approaches to health promotion while also acknowledged the importance of access to health services. There were two elements to this comprehensive approach. The first was environment-centered, focused on improving the educational and relational atmosphere or ethos within a school (18, 42). The second was student-centered, focused on individual and problem-focused approaches, such as resilience-building or interventions to improve individual coping skills, social support, and self-esteem (39, 43). This latter approach also included access to health services when required. These two approaches were viewed as complementary to each other.

Most manuals suggested that structured approaches were needed to support dissemination, such as assessment tools and the inclusion of practical material for training. For example, several manuals included training modules to help deliver transferrable knowledge (concepts, principles, and strategies about program implementation) and equip learners with the skills and tools to apply this (13, 31, 35, 42). Most guidelines were appreciated as valuable references to relevant concepts, principles, and strategies. Within these, more typical approaches to dissemination, such as promoting the transferability of skill sets, were generally not described. Guidelines seemed particularly useful in informing policymakers and UN member state governments around developing national policies (17, 36, 38).

These globally oriented guidelines and manuals require national commitments for recommendations to be implemented, which is also supported by recommendations around monitoring and evaluation. These documents consistently included some recommendations for monitoring and evaluation, although these varied in their approaches. Some recommended a somewhat basic assessment consisting primarily of process and outcome evaluations (13, 41), while others recommended a broader assessment of program logic indicators, such as input, process, outcome, output, and impact evaluation (30, 37, 46). Several manuals provided a list of measurement tools and gave examples for developing an assessment approach at the school level, but without being framed within a wider approach to monitoring and evaluating national dissemination (39, 42, 43). A few recommended more complex assessment approaches and included strategies and assessment tools within the documentation (15, 46). The most comprehensive assessment strategy was articulated within the UNESCO FRESH model, which outlined different levels of assessments that ranged from the national level for assessing the existence, and the quality of national health education plans to the school level for assessing the extent that schools implemented skills-based education (30). These documents clearly expect schools to have the capacity to provide mental health promotion according to the level of mental health needs of the school community. This suggests that national and local assessments (e.g., school and community surveys) that enable school-based actions to match local needs are required, including knowledge of risk factors for mental health problems, as articulated in the new Global Standards and Indicators for Health-promoting Schools and Systems (15).

Over the two decades of this review, the clearest commitment around the scope of mental health prevention and promotion was to deliver universally framed interventions that aimed to reach all members of the school community (rather than targeting interventions for more at-risk students or to those identified with mental health problems). The universal approach appears to have been widely interpreted as reflecting aspects of school curricula (e.g., individual student-focused approaches to developing skills-based health education) and extra-curricular activities for students, together with efforts to promote the establishment of healthy school environments. Less frequently noted across policy documents was the need to promote the mental health and wellbeing of all school community members, including teachers and school staff, which was particularly noted in the new Global Standards and Indicators for Health-promoting Schools and Systems (15, 16).

What schools can do to promote mental health

These UN guidelines and manuals suggest that the role of schools is mainly focused on building enabling contexts for mental health and wellbeing. Within these documents, three strategies were recommended for schools to create the enabling structures, functions, and roles that underpin a supportive school system (47, 48). These were to:

1. Establish a school mental health implementation team. Schools can form a school mental health team, as a part of the school-health system, which may include school leaders, teachers, school-based mental health staff, and special education teachers. The school mental health team also needs to develop a network of connections within a school’s local community, which might include local health services, families, civil society organizations, and youth groups;

2. Profile existing needs, resources, and systems. Schools can conduct a mapping exercise as a strategy to identify gaps between needs and current resources, including accessibility. This will be relevant for approaches that aim: to identify students who may benefit from health services, to identify relevant curriculum materials, such as those that may help build mental health literacy and reduce stigma around people with mental health conditions, and to consider the role of the school’s social and physical environments in promoting wellbeing;

3. Partner with policymakers and the community. Schools are required to maintain cooperative engagement with governments and related stakeholders, as beyond ensuring that standards and regulations are implemented, access to resources and personnel are also needed.

Multiple meanings of “comprehensive school health”

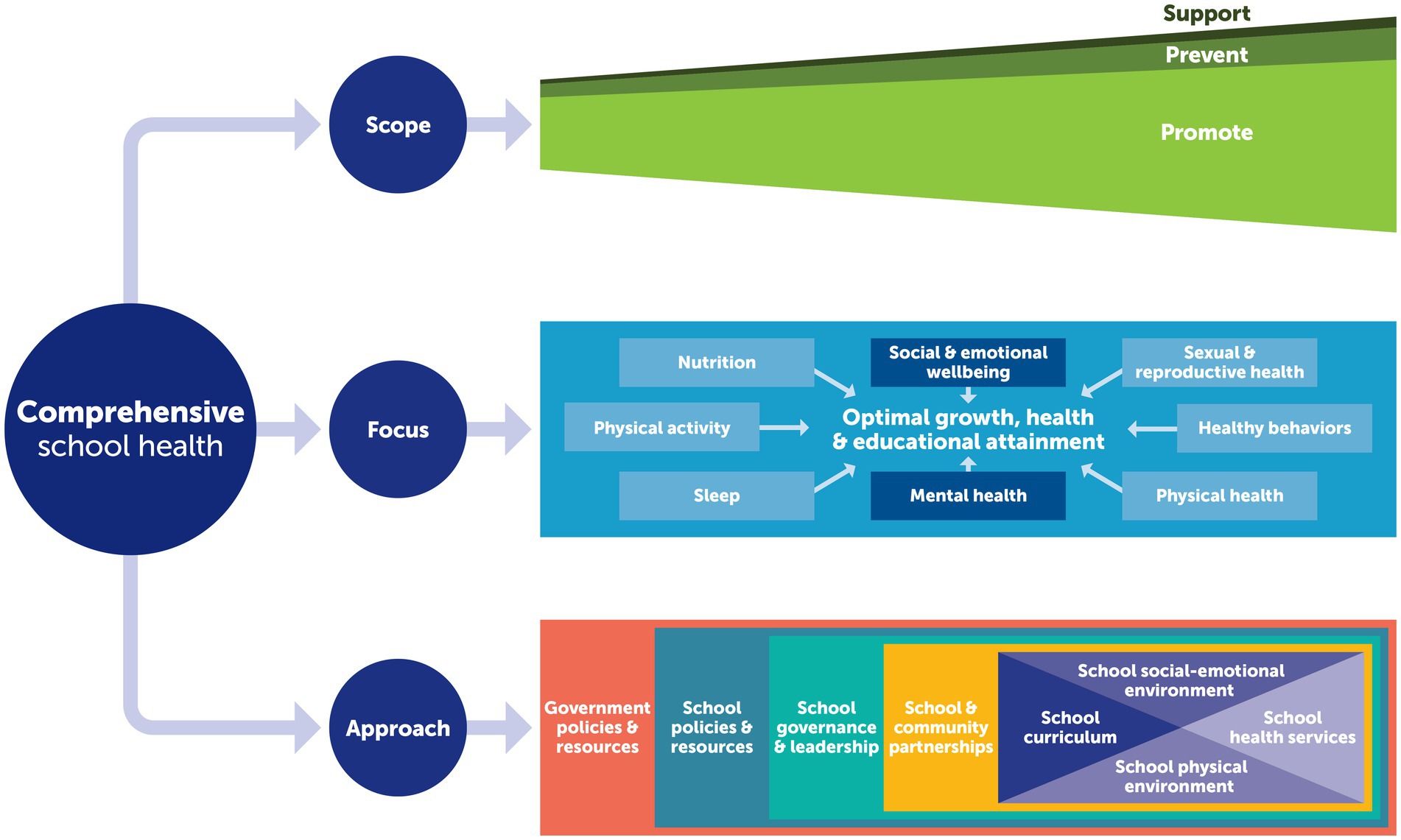

While a comprehensive school-health framework was commonly articulated within these documents, we identified three different conceptions of “comprehensive,” as shown diagrammatically in Figure 3. The first derives from the 1994 multi-tiered mental health model, which conceptualized a comprehensive suite of interventions that spanned from universally oriented health promotion and preventive interventions to more indicated interventions that support students with mental health issues at school (9). In this way, the notion of comprehensiveness is around scope, with the multi-tiered mental health model oriented to and inclusive of different populations, embodying different needs and risks.

A second concept, embodied within WHO’s more recent Health-promoting Schools policy documents, views comprehensiveness in relation to the focus of health addressed by school health. In this way, comprehensive health promotion conceptualizes mental health promotion as one of a range of health topics that schools need to address. For example, the Health-promoting Schools approach encourages schools to respond to the health priorities within its community, which beyond mental health might include aspects of nutrition, physical activity, unintentional injury and interpersonal violence, substance use, self-harm, gender norms and sexual and reproductive health, communicable and non-communicable disease, physical and sensory disabilities, and oral health (9, 15). A feature of this approach is its attention to the efficiencies that can be gained by taking a more comprehensive view of health; strategies to promote physical activity can be framed as mental health promotion, as can efforts to address more healthy gender norms, responses to student and teacher bullying and interpersonal violence at school. This approach also appreciates that attending to more generic aspects such as student–student relationships (e.g., zero bullying), student–teacher interactions (e.g., approaches to punishment and student recognition), and active pedagogy (e.g., leadership opportunities) can enhance school connectedness which benefits mental health.

The third conceptualization of comprehensive, embodied within FRESH and also within Health-promoting Schools, views comprehensive school health as an approach or framework for addressing health, including mental health, in a planned, integrated, and holistic approach while aiming to improve students’ educational outcomes (17). Rather than a focus on a particular population, or health topic, this notion of comprehensive refers to the breadth of approach, which is whole-school in its orientation and explicitly intended to promote health and wellbeing as well as educational attainment.

A further finding was the inconsistency in orientation and terminology between these guidelines and manuals, even within the same agency. For example, within WHO, one manual for mhGAP was referred to as an “intervention guide” (31) while another manual was called a “practical handbook” for school-based violence (35). UNICEF refers to its Child-Friendly School’s policy document as a manual, yet while its contents indeed focus on implementation (as expected from a manual), the inclusion of principles, indicators, and standards, and country case studies appear more appropriate content for a guideline (18).

Discussion

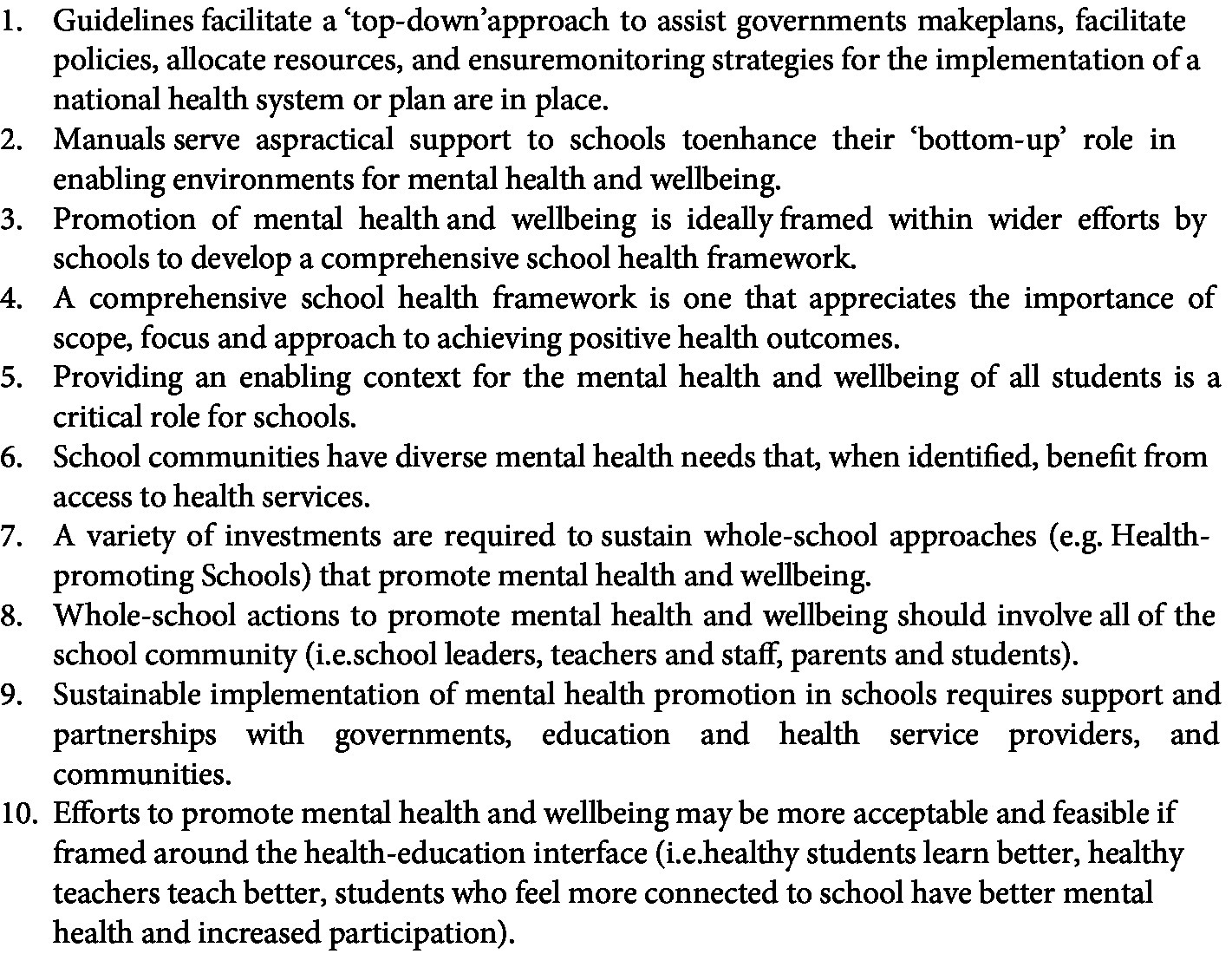

This policy review of global manuals and guidelines reveals that the UN agencies have made significant efforts to orient national governments and their schools to the importance of promoting the mental health and wellbeing of school-age children worldwide, a feature that has gained acute significance since the COVID-19 pandemic. We identified three major findings from this synthesis of 16 UN agency global policy documents on school mental health promotion. The first finding was that efforts to promote mental health are ideally framed within wider efforts by schools around health promotion. The second finding was the importance of schools engaging in health-promoting actions that are universal in their scope, that is, are aimed at all students. Linked to this is the third finding, which is the important role that schools have in providing an enabling context for mental health and wellbeing. A series of recommendations arising from this policy review are described in Figure 4.

These findings suggest the value of embedding a school mental health strategy within a school’s comprehensive health promotion framework, which will ideally appreciate the importance of scope, focus, and approach to achieving positive health outcomes. Such a framework reinforces that schools need to be able to deliver actions to address mental health by implementing strategies to prevent mental health problems, promote wellbeing, and manage students with mental disorders, with an eye to how these strategies intersect with other health issues and themes (e.g., gender norms, safety, nutrition, physical activity). Attending to student mental health exemplifies the complex relationships between health and educational attainment, given the effects of mental disorders on student motivation and attention, school engagement, absenteeism, early school completion and learning outcomes, and the knowledge of how school connectedness predicts mental health (15, 16, 49). Investment will be required to orient school communities to this knowledge, as without this, an obvious challenge for schools is that addressing health concerns may not be perceived as a priority by those in the education sector, including families and communities (50).

Sustainable implementation of mental health promotion in schools will require investment by governments in school communities to equip them with the resources they need to actively engage in whole-school approaches (50, 51). One challenge is that many of the guidelines and manuals we reviewed used more individually-oriented approaches (e.g., curriculum-based interventions to promote socio-emotional learning). Using all the levers available to schools to promote mental health is required, including approaches that engage a school’s social mechanisms to promote connectedness and belonging (49).

Collaboration between the UN agencies creates opportunities for more specific guidelines around mental health. In this way, for example, WHO’s mental health Gap Action Program-Intervention Guide (mhGAP-IG) can be seen to intersect with more generic approaches such as Accelerated Action for the Health of Adolescents (AA-HA!), INSPIRE, and Health-promoting Schools. Similarly, UNICEF has promulgated efforts to address mental health in specific contexts, such as humanitarian settings, through the Inter-Agency Standing Committee Guidelines in Mental Health and Psychosocial Supports (IASC-MHPS) (52, 53), which has developed a module on Community-based Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in Humanitarian Settings (CBMHPSHS). While these approaches were not explicitly created for school contexts, they are also relevant for promoting mental health in schools. Given these opportunities, it would be pleasing to see future generic policy documents articulate how they link to specific guidelines, and vice versa, as articulated by at least some of these documents (37).

This policy review suggests that over the past two decades, there has been a growing trend toward advocating universal approaches that target all school populations (i.e., students, teachers, and school staff) and that aim to reduce the population burden of mental health conditions. There is also growing emphasis on the interface between educational attainment and health. For example, FRESH aims to promote safe learning environments and improve children’s health skills with the goal of improving the quality of education delivered. UNICEF’s Child-Friendly Schools initiative focuses on the wellbeing of the whole child, including attention to the different needs of different groups according to gender, physical ability, and socio-economic status, appreciating the importance of these for health and education. The Global Standards for Health-promoting Schools encourages schools to create the type of social and learning environments that support respectful relationships between students and warm, engaging relationships between students and teachers (15, 54). The whole-school approach advocated within Health-promoting schools moves beyond a singular or narrow focus on health education to one that aligns curriculum approaches with efforts to build social and emotional literacy, positive peer-peer and student-peer relationships, and inclusive school communities with the knowledge that these are all reflected in mental health and wellbeing (55, 56). Schools are learning environments that, year by year, month by month, and even day by day, build on earlier investments that extend students’ engagement and capabilities, consistent with knowledge of their cognitive, social, and emotional capabilities. In this way, schools are inherently oriented to healthy growth and development based on incremental approaches to learning (17). Arguably, universal approaches to health promotion are highly consistent with this educational philosophy. While feasible for schools to implement, such universal approaches to mental health promotion require intentional, thoughtful, and measured approaches, just as schools require to achieve their learning objectives (16). These global documents encourage government agencies to contribute to the establishment of school health and support the sustainability of schools’ universal mental health programs by facilitating policies and regulations, funding, and resources. Overtly framing universal health initiatives around educational objectives may help schools and their staff to appreciate some of the important intersections between educational and health goals (e.g., good nutrition, physical activity, sleep).

These UN agency guidelines and manuals consistently reinforce the importance of supporting schools to provide an enabling context for mental health and wellbeing. Within a comprehensive school-health framework, the expectations are that schools invest in building their internal and external capacities around a variety of roles. These include developing intersectoral partnerships. Every school community needs access to referral networks, resources, and health professionals who are trained to diagnose and treat common mental disorders, whether those services are delivered within the school or beyond its walls (57). Embodying health and education sector expertise within school-health committees is also required. However, wider partnerships are needed for schools to become safe, non-punitive, and inclusive learning environments, including transport and welfare. Given their thought leadership in many communities, partnering with religious leaders will also be valuable for schools, as efforts to promote mental health are highly reliant on reducing the stigma around mental disorders (58, 59).

Within this global policy review, it is not surprising that the various manuals were oriented around school-led programs and focused on the delivery system using a school-led or “bottom-up approach.” In this context, schools initiate implementation because they seek specific education, social, or health benefits, which is commonly followed by efforts to seek support from community leaders and policymakers to promote sustainability. Many previous approaches to mental health promotion within a Health-promoting Schools framework started with school-level initiatives. For example, WHO’s guidance on suicide prevention (SUPRE) in schools was launched within a Health-promoting Schools approach in 1998 (60). Since then, guidelines for countries to develop national SUPRE plans and strategies have been developed as a more “top-down” approach (61, 62) consistent with the recent guidelines we reviewed that emphasize the importance of building a system for mental health promotion. These approaches recognize the importance of government investments that support schools in implementing specific actions. For example, FRESH is a top–down strategy that encourages governments to initiate and develop policies on school health, including creating a school-health system, and then working with schools to implement this approach.

Similarly, WHO’s school-based violence prevention is a practical approach that targets schools to support them to implement the earlier guideline of the Global Plan of Action on violence against women and children that had been accepted by the national governments of UN member states (35, 40, 60). Rather than individual schools taking responsibility for designing or developing mental health-promoting interventions, these top-down policies view schools as the extended arm of the government with the responsibility for implementation of the national health system or plan. While national accountability for school mental health promotion could be equally advocated through a top-down approach, the lack of a consistent approach to monitoring and accountability in these documents was disappointing.

It is hoped that, building on evidence of effectiveness, these findings can help guide national governments and schools in their decisions about what to target within school mental health promotion, which strategies they might select and what partnerships are required. However, this review also has wider learnings around the inconsistent use of language, whether around the meaning of “comprehensive school health” or indeed around the definition of a manual or guideline. We suggest that manuals should aim to support school initiatives in developing and implementing school-based mental health promotion initiatives; manuals should therefore be practically oriented and focus on troubleshooting or problem-solving. Guidelines can be less practical, as their top–down approach is intended to assist governments in making plans, facilitating policies, allocating resources, and ensuring monitoring strategies are in place and, in turn, will inform the next steps. We found that across these documents, very few manuals provided sufficient practical support to schools that would enhance their “bottom-up” role in providing enabling environments for mental health and wellbeing. This may suggest that manuals are more relevant at a country level, rather than globally. Regardless, beyond the need for both top–down and bottom–up approaches, individual guidelines and manuals should be supported by training materials and assessment tools for monitoring implementation and evaluating outcomes.

This study has several limitations. Firstly, notwithstanding active discussion between the authors of any questionable findings, the document searches and data extraction were identified by a single reviewer as part of the first author’s doctoral studies. Reliability might have been enhanced if more than one reviewer had been involved in screening and data extraction. Secondly, this global policy review did not extend beyond the network of UN agencies. Including global professional association documents may have widened the scope of identified documents. However, as these UN agency documents are evidence-based, we anticipate that they will have built on any important, relevant documents. Thirdly, we did not set out to capture country-level guidelines and manuals due to the challenge of identifying these and the variety of languages in which they are published. We fully expect that at least some of these would be relevant globally. Fourthly, the majority of documents were produced by the WHO. On the one hand, this is logical, given WHO is the primary global body managing health issues. Arguably, more documentation from UNESCO may have been expected given their school policy context. The predominance of WHO documents could also reflect the search strategy that used WHO-IRIS, a WHO library platform. Most health-related policy documents should be stored in this platform, regardless of the UN agency that produces them, but our inclusion of two additional search approaches was with the intention of mitigating this potential bias. Finally, we did not set out to evaluate the effectiveness of mental health promotion in schools, nor the costs of implementing any of these approaches, both of which are important to explore in further studies.

Conclusion

This policy review reveals that the UN agencies have made significant efforts to orient national governments and their schools to the importance of promoting the mental health and wellbeing of school-age children worldwide. Notwithstanding inconsistent terminology between guidelines and manuals, and a variety of ways that comprehensiveness could be conceptualized, we found that the scope of these guidelines and manuals was predominantly oriented toward universal interventions using the approach of Health-promoting Schools. While the global standards for Health-promoting Schools include a set of indicators, these do not focus on specific health topics such as mental health (15). Developing a set of indicators for specific health topics, such as mental health promotion, could be helpful for national governments, as this would drive accountability through monitoring and evaluation.

From the policy perspective, this review reinforces the importance of government, international agencies, and donors developing plans that support schools to provide enabling learning and social environments that promote mental health and wellbeing, which will benefit from both top-down and bottom-up approaches. An initial priority is ensuring that country-level policymakers create policies, operational guidelines, and regulations to facilitate how schools address the spectrum of mental health promotion, including health promotion, prevention, and the provision of health services for those who need them, whether at school or in the community.

Author contributions

MM led this research as part of her doctoral thesis at The University of Melbourne, which is supervised by SS, PA, and JF. MM contributed most to the research and writing of the manuscript. PA served as the second supervisor, outlined the concept, helped with writing ideas, and co-authored the abstract. JF served as the third supervisor, provided guidance throughout execution of the project, provided feedback on the writing draft, and co-authored the abstract. SS served as the primary supervisor, outlined the concept, secured funding and provided guidance throughout execution of the project, and co-authored the abstract, background, and method. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The publication of this manuscript was funded by the Centre for Adolescent Health, Royal Children’s Hospital, Parkville, VIC, Australia. MM was funded by the Australia Awards Scholarships from the Government of Australia.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Monika Raniti, Ruth Aston, and Katina Tan for helpful discussions and feedback on Figure 3.

Conflict of interest

SS contributed to the development of the WHO and UNESCO Global Standards and Systems for Health-Promoting Schools. SS was a member of the WHO Technical Advisory Committee for School Health Services.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The handling editor SS declared a past collaboration with the author SS.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1126767/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

References

1. Bor, W, Dean, AJ, Najman, J, and Hayatbakhsh, R. Are child and adolescent mental health problems increasing in the 21st century? A systematic review. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. (2014) 48:606–16. doi: 10.1177/0004867414533834

2. Loades, ME, Chatburn, E, Higson-Sweeney, N, Reynolds, S, Shafran, R, Brigden, A, et al. Rapid systematic review: the impact of social isolation and loneliness on the mental health of children and adolescents in the context of COVID-19. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2020) 59:1218–1239.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2020.05.009

3. Jones, EAK, Mitra, AK, and Bhuiyan, AR. Impact of covid-19 on mental health in adolescents: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:1–9. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18052470

4. Racine, N, Cooke, JE, Eirich, R, Korczak, DJ, McArthur, BA, and Madigan, S. Child and adolescent mental illness during COVID-19: a rapid review. Psychiatry Res. (2020) 292:113307–3. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113307

5. Busch, V, Rob, J, de Leeuw, J, de Harder, A, Jacobus, A, and Schrijvers, P. Changing multiple adolescent health behaviors through school-based interventions: a review of the literature. (2013) 83:514–523. doi: 10.1111/josh.12060

6. Patel, V, Flisher, AJ, Nikapota, A, and Malhotra, S. Promoting child and adolescent mental health in low and middle income countries. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. (2008) 49:313–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01824.x

7. UN. Social inclusion of youth with mental health conditions. (2014). Available at: http://undesadspd.org/Youth.aspx

8. Clark, AG, and Dockweiler, KA. Multi-tiered Systems of Support in elementary schools; the definitive guide to effective implementation and quality control. New York: Routledge (2020).

9. World Health Organization. Mental health Programmes in schools. Geneva: World Health Organization (1994).

10. Williams, I, Vaisey, A, Patton, G, and Sanci, L. The effectiveness, feasibility and scalability of the school platform in adolescent mental healthcare. Curr Opin Psychiatry. (2020) 33:391–6. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000619

11. Das, JK, Salam, RA, Lassi, ZL, Khan, MN, Mahmood, W, Patel, V, et al. Intervention models for increasing access to behavioral health services among youth: a systematic review. J Dev Behav Pediatr. (2018) 59:S49–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.06.020

12. World Health Organization. WHO technical report series promoting health through schools. Geneva: World Health Organization. (1997).

13. World Health Organization. WHO information series on school health: local action creating health promoting schools. Geneva: World Health Organization (2000).

14. World Health Organization. Health promoting schools. World Health Organization (2022). Available at: https://www.who.int/health-topics/health-promoting-schools (Accessed September 13, 2022)

15. World Health Organization. Making every school a health-promoting school: Implementation guidance. Geneva: World Health Organization (2021).UNESCO

16. World Health Organization. Guideline on school health services. Geneva: World Health Organization (2021).UNESCO

17. UNESCO. Focusing resources on effective school health (FRESH): A FRESH approach for achieving education for all (EFA). Paris: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (2002).

18. United Nations Children’s Fund. Child friendly schools: manual. New York: United Nations Children’s Fund.

19. Field, MJ, Marilyn, J, and Lohr, KN, Institute of Medicine (U.S.). Committee to advise the public health service on clinical practice guidelines, United States. Department of Health and Human Services. Clinical practice guidelines: Directions for a new program. Washington: National Academy Press (1990). 160 p.

21. Rosenfeld, RM, Shiffman, RN, and Robertson, P. Clinical practice guideline development manual, third edition: a quality-driven approach for translating evidence into action. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. (2013) 148:S1–S55. doi: 10.1177/0194599812467004

22. Munn, Z, Stern, C, Aromataris, E, Lockwood, C, and Jordan, Z. What kind of systematic review should i conduct? A proposed typology and guidance for systematic reviewers in the medical and health sciences. BMC Med Res Methodol. (2018) 18:5. doi: 10.1186/s12874-017-0468-4

23. McArthur, A, Klugárová, J, Yan, H, and Florescu, S. Innovations in the systematic review of text and opinion. Int J Evid Based Healthc. (2015) 13:188–95. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000060

24. Wei, Y, and Kutcher, S. International school mental health: global approaches, global challenges, and global opportunities. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. (2012) 21:11–27. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2011.09.005

25. Page, MJ, McKenzie, JE, Bossuyt, PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Sys. Rev. (2021) 10:89. doi: 10.1186/s13643-021-01626-4

26. World Health Organization. INSPIRE handbook: Action for implementing the seven strategies for ending violence against children. Geneva: World Health Organization (2018).

27. WHO. mhGAP intervention guide for mental, neurological and substance use disorders in non-specialized health settings: Mental health gap action programme (mhGAP). (2016).

28. WHO. Accelerated action for the health of adolescents (AA-HA!) a manual to facilitate the process of developing national adolescent health strategies and plans. (2019).

29. WHO. Guidelines on mental health promotive and preventive interventions for adolescents: Helping adolescent thrive (HAT). (2020).

30. UNESCO. Monitoring and evaluation guidance for school health programs: Eight Core indicators to support FRESH (focusing resources on effective school health). Paris: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (2013).

31. World Health Organization. Mental health gap action Programme intervention guide (mhGAP-IG) for mental, neurological and substance-use disorders in non-specialized health settings. Version 2.0. Geneva: World Health Organization (2016). Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241549790 (Accessed September 13, 2022)

32. World Health Organization. Mental health gap action Programme (mhGAP). Scaling up care for mental, neurological, and substance-use disorders. Geneva: World Health Organization (2008) [Accessed September 13, 2022]https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/43809.

33. World Health Organization. Mental health gap action Programme intervention guide (mh-GAP-IG) for mental, neurological and substance use disorders in non-specialized health settings. Version 1.0. Geneva: World Health Organization (2010). Available at: (Accessed September 13, 2022 https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/250239)

34. World Health Organization. Preventing suicide: A resource for teachers and other school staff. Geneva: World Health Organization (2000).

35. World Health Organization. School-based violence prevention: A practical handbook. Geneva: World Health Organization (2019).

36. United Nations Children’s Fund. INSPIRE indicator guidance and results framework: Ending violence against children - how to define and measure change. New York: United Nations Children’s Fund (2018).

37. United Nations Children’s Fund. Operational guidelines. Community-based mental health and psychosocial support in humanitarian Settings. Three-tiered support for children and families. New York: United Nations Children’s Fund (2018).

38. World Health Organization. Helping adolescents thrive (HAT): Guidelines on mental health promotive and preventive interventions for adolescents. Geneva: World Health Organization (2020).

39. World Health Organization. WHO information series on school health. Family life, reproductive health, and population education: Key elements of a health-promoting school. Geneva: World Health Organization (2003).

40. World Health Organization. Global plan of action to strengthen the role of the health system within a national multisectoral response to address interpersonal violence, in particular against women and girls, and against children. Geneva: World Health Organization (2016).

41. UNESCO. Education for health and wellbeing: Contributing to the sustainable development goals. Paris: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (2016).

42. World Health Organization. WHO information series on school health. Creating an environment for emotional and social well-being: An important responsibility of a health-promoting and child friendly school. Geneva: World Health Organization (2003).

43. World Health Organization. WHO information series on school health. School for Health. Skills-based health education including life skills: An important component of a child-friendly/health-promoting school. Geneva: World Health Organization (2003).

44. World Health Organization. Accelerated action for the health of adolescents (AA-HA!): A manual to facilitate the process of developing national adolescent health strategies and plans. Geneva: World Health Organization (2019).

45. World Health Organization. Global accelerated action for the health of adolescents (AA-HA!) guidance to support country implementation. Geneva: World Health Organization (2017).

46. United Nations Children’s Fund. INSPIRE indicator guidance and results framework: ending violence against children - how to define and measure change. United Nations Children’s Fund (2018). Available at: https://www.unicef.org/documents/inspire-indicator-guidance-and-results-framework (Accessed September 13, 2022)

47. Fixsen, D, Hassmiller-Lich, K, and Schultes, M. Shifting Systems of Care to support school-based services In: AW Leschied, DH Saklofske, and GL Flett, editors. Handbook of school-based mental health promotion: An evidence-informed framework for implementation. Cham: Springer (2018). 51–63.

48. Patel, V, and Rahman, A. Editorial commentary: an agenda for global child mental health. Child Adolesc Ment Health. (2015) 20:3–4. doi: 10.1111/camh.12083

49. Raniti, M, Rakesh, D, Patton, GC, and Sawyer, SM. The role of school connectedness in the prevention of youth depression and anxiety: a systematic review with youth consultation. BMC Public Health. (2022) 22:2152–73. doi: 10.1186/s12889-022-14364-6

50. Jourdan, D, Gray, NJ, Barry, MM, Caffe, S, Cornu, C, Diagne, F, et al. Supporting every school to become a foundation for healthy lives. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. (2021) 5:295–303. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30316-3

51. Taylor, L, and Adelman, HS. Toward ending the marginalization and fragmentation of mental health in schools. J Sch Health. (2000) 70:210–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2000.tb06475.x

52. Inter-Agency Standing Committee. Inter-agency standing committee (IASC) guidelines on mental health and psychosocial support in emergency settings. Geneva: Inter-Agency Standing Committee (2007).

53. Inter-Agency Standing Committee. A common monitoring and evaluation framework for mental health and psychosocial support in emergency settings. Geneva: Inter-Agency Standing Committee (2017).

54. World Health Organization. Making every school a health-promoting school: Global standards and indicators. Geneva: World Health Organization (2021).

55. Bonell, C, Allen, E, Warren, E, McGowan, J, Bevilacqua, L, Jamal, F, et al. Effects of the learning together intervention on bullying and aggression in English secondary schools (INCLUSIVE): a cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet. (2018) 392:2452–64. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31782-3

56. Shinde, S, Weiss, HA, Varghese, B, Khandeparkar, P, Pereira, B, Sharma, A, et al. Promoting school climate and health outcomes with the SEHER multi-component secondary school intervention in Bihar, India: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. (2018) 392:2465–77. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31615-5

57. Baltag, V, Pachyna, A, and Hall, J. Global overview of school health services: data from 102 countries. Health Behav Policy Rev. (2015) 2:268–83. doi: 10.14485/hbpr.2.4.4

58. Kutcher, S, Wei, Y, and Coniglio, C. Mental health literacy: past, present, and future. Can J Psychiatr. (2016) 61:154–8. doi: 10.1177/0706743715616609

59. Shu-Ping Chen, ES, Sargent, E, and Stuart, H. Effectiveness of school-based interventions on mental health stigmatization In: A Leschied, D Saklofske, and G Flett, editors. Handbook of school-based mental health promotion an evidence-informed framework for implementation. Cham: Springer (2018). 201–12.

60. World Health Organization. WHO information series on school health. Violence prevention: An important element of a health-promoting school. Geneva: World Health Organization (1998).

61. World Health Organization. Live life: An implementation guide for suicide prevention in countries. Geneva: World Health Organization (2021).

Keywords: school, mental health promotion, United Nations (UN), guideline, manual, global policy

Citation: Margaretha M, Azzopardi PS, Fisher J and Sawyer SM (2023) School-based mental health promotion: A global policy review. Front. Psychiatry. 14:1126767. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1126767

Edited by:

Sachin Shinde, Harvard University, United StatesReviewed by:

Urvita Bhatia, Sangath, IndiaPadmavati Ramachandran, Schizophrenia Research Foundation, India

Copyright © 2023 Margaretha, Azzopardi, Fisher and Sawyer. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Margaretha Margaretha, bWFyZ2FyZXRoYUBwc2lrb2xvZ2kudW5haXIuYWMuaWQ=

Margaretha Margaretha

Margaretha Margaretha Peter Sebastian Azzopardi

Peter Sebastian Azzopardi Jane Fisher

Jane Fisher Susan Margaret Sawyer

Susan Margaret Sawyer