- 1Division of Psychology and Mental Health, School of Health Sciences, Faculty of Biology, Medicine and Health, The University of Manchester, Manchester, United Kingdom

- 2Perinatal Mental Health and Parenting (PRIME) Research Unit, Research and Innovation Department, Greater Manchester Mental Health National Health Service (NHS) Foundation Trust, Manchester, United Kingdom

- 3Greater Manchester Mental Health NHS Foundation Trust, Perinatal Specialist Service, Manchester, United Kingdom

Background: Dialectical Behaviour Therapy (DBT) combines cognitive-behavioural techniques and mindfulness practices to more skilfully regulate intense emotions and navigate interpersonal issues. While traditional DBT (skills group, individual therapy and crisis support) is well-studied in clinical populations, particularly for emotion regulation in conditions like borderline personality disorder or emotionally unstable personality disorder, recent research has explored alternative formats, such as skills-only groups. Although quantitative studies report positive outcomes (e.g., reduced self-injury and suicidality), less is known about patient experiences, which are crucial for developing effective interventions. This systematic review explored patient experiences of DBT skills groups across mental health conditions and age groups, considering the processes patients perceived as contributing to therapeutic change and outcomes.

Method: A systematic search was conducted across five databases following PRISMA guidelines, using search terms related to DBT and patient experience. Peer-reviewed papers employing qualitative or mixed-methods were included. Thematic synthesis was used for analysis.

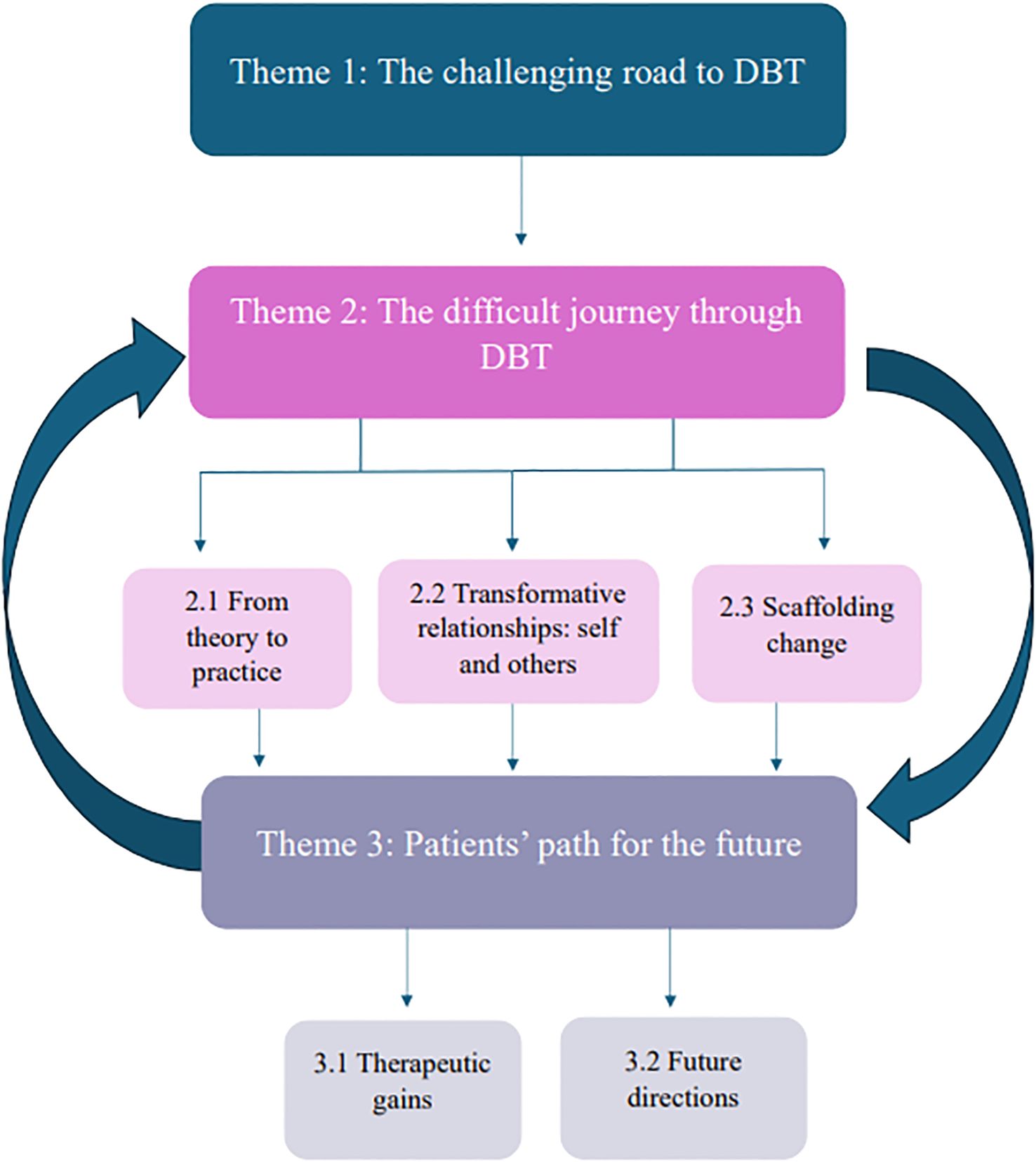

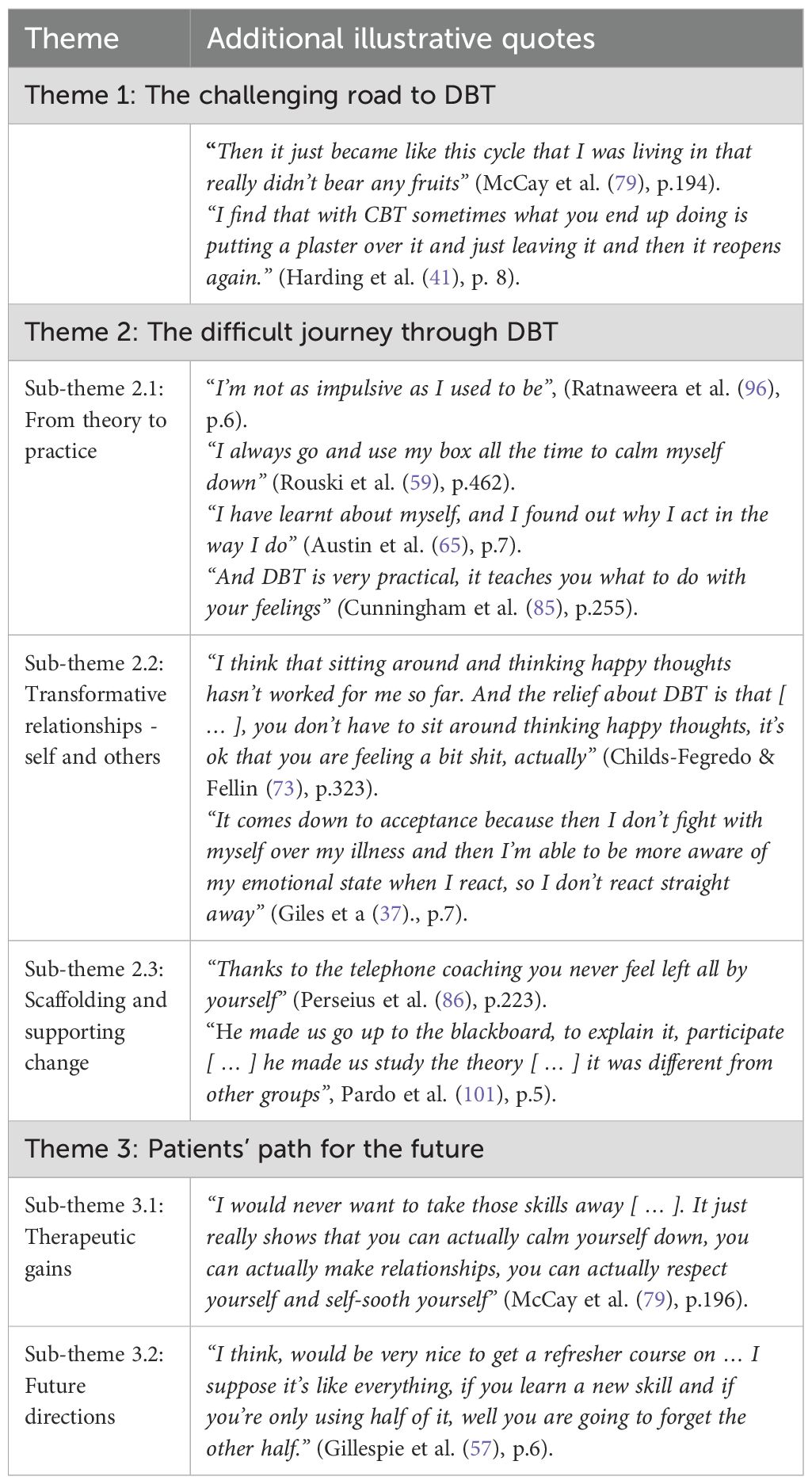

Results: Thirty-two papers were eligible for inclusion. Three main themes were generated: 1) the challenging road to DBT, 2) the difficult journey through DBT, and 3) patients’ path for the future. Theme two contained three sub-themes (from theory to practice, transformative relationships - self and others, scaffolding and supporting change) and theme three included two sub-themes (therapeutic gains, future directions).

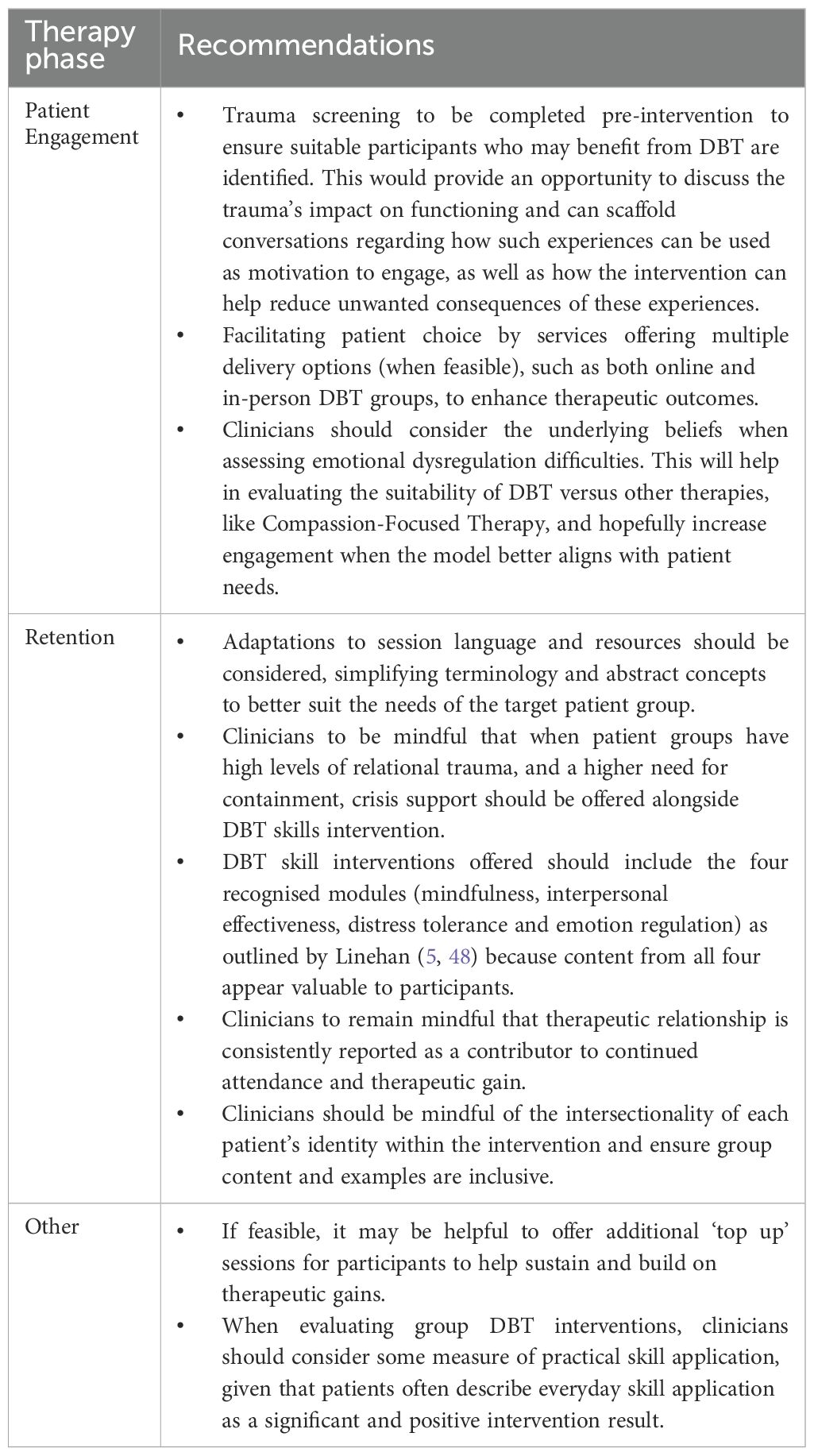

Conclusions: Findings highlight the importance of pre-treatment and in-treatment experiences alongside relational factors like safety and validation and practical skill application. Key processes, including peer support and changed perspectives, shape therapeutic outcomes. Recommendations include flexible delivery formats and aligning patient preferences with intervention to maximise gains.

Systematic review registration: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/login, identifier PROSPERO (CRD42024604496).

1 Introduction

DBT is a well-established psychological intervention, originally developed by Linehan (1, 2) as a comprehensive treatment for individuals with borderline personality disorder (BPD), which is characterised by interpersonal relationship difficulties and ineffective emotion regulation, often leading to self-injury or suicidality. Originally, DBT was designed as an intensive year-long programme, covering four modules (mindfulness, interpersonal effectiveness, distress tolerance and emotion regulation), to address the chronic and pervasive nature of difficulties faced by those diagnosed with BPD. DBT combined group skills training, individual psychotherapy, telephone coaching and therapist team consultations. Over the past two decades, continued research has demonstrated DBT’s effectiveness in reducing self-injury and suicidal behaviours (3–6).

While DBT research has historically focussed on adults with BPD, its emphasis on addressing emotion regulation difficulties (such as intense mood swings, impulsivity, and interpersonal challenges) has led to its broader application in treating other presentations underpinned by these difficulties, including eating disorders (7), attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (8) and trauma-related conditions (9–11). Numerous systematic reviews and meta-analyses highlight DBT’s effectiveness across mental health conditions and clinical settings, consistently demonstrating reductions in distress-related behaviours, such as suicidality and self-injury in adults (12–16), and adolescents (17). However, while various studies and reviews provide evidence for DBT’s effectiveness transdiagnostically, they reveal little about the mechanisms of change or the patient experience.

A growing body of literature emphasises the importance of understanding patient perspectives, including treatment acceptability, satisfaction, and perceived therapeutic gains (18, 19). McPherson et al. (18) argue that while RCTs and meta-analyses are invaluable for assessing efficacy and effectiveness, they often overlook critical contextual factors that shape treatment engagement and outcomes. Without qualitative insights, systematic reviews risk presenting an incomplete understanding of why DBT is helpful for various mental health conditions, and how it impacts patients’ daily lives.

Given the resource demands of traditional DBT, a stand-alone DBT skills group format emerged over time through clinical and research adaptations. This format is increasingly used as a cost-effective alternative to traditional DBT (5, 20) given the time and financial constraints healthcare settings often face. For example, DBT skills groups alone have been found to significantly reduce emotional dysregulation and depressive symptoms (21–24). By retaining DBT’s modular structure (mindfulness, interpersonal effectiveness, distress tolerance and emotion regulation) and core principles (such as dialectics, validation, and behavioural change), the stand-alone skills group format offers a more accessible and resource-efficient alternative to traditional DBT programmes for individuals with emotion regulation difficulties across diverse clinical populations. Furthermore, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis of 11 studies with adolescents (25) underscored the therapeutic value and positive impact of these skills groups on suicidal ideation and risk management.

As both stand-alone DBT skills groups and those delivered as part of comprehensive DBT programmes are increasingly used in clinical practice, understanding patient experiences of the group-based components becomes especially important. To date, only two systematic reviews synthesised qualitative or mixed-methods research on patient experiences of traditional DBT. Using a meta-ethnographic approach, Little et al. (26) analysed seven studies and identified four main themes: life before DBT, supportive relationships for change, shifts in perspective and the development of self-efficacy. More recently, Middlehurst et al. (27) expanded on this work, synthesising 11 studies and highlighting three main themes: impact of DBT, supportive structure and 1:1 therapy component. Advocating for further research to deepen understanding of patient perspectives, the authors of both reviews concluded that adult patient experiences of DBT were complex and multifaceted. Although quantitative research supports DBT’s transdiagnostic effectiveness across different age groups (e.g., adolescents and adults), qualitative insights remain underexplored. The aforementioned reviews focussed solely on adults with a diagnosis of BPD, thereby leaving a crucial gap in the literature regarding patient experiences across ages and mental health conditions.

Thus, in this systematic review we aimed to explore patient experiences of DBT skills groups, whether delivered as stand-alone interventions or embedded within full DBT programmes, across mental health conditions and age groups (adolescents and adults). Additionally, we considered the processes patients perceived as contributing to therapeutic change and outcomes. By addressing this gap, the review could provide valuable insights to support patient-centred care and enhance the refinement of DBT interventions in diverse clinical settings.

2 Methods

A systematic review and meta-synthesis, informed by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (28) was undertaken to address the review’s aims. The protocol was registered with PROSPERO on 23/10/2024 (Ref: CRD42024604496). The Enhancing Transparency in Reporting the Synthesis of Qualitative Research (ENTREQ) checklist (29) was completed to ensure appropriate reporting of review findings (see Appendix 1 for completed checklist).

2.1 Search strategy

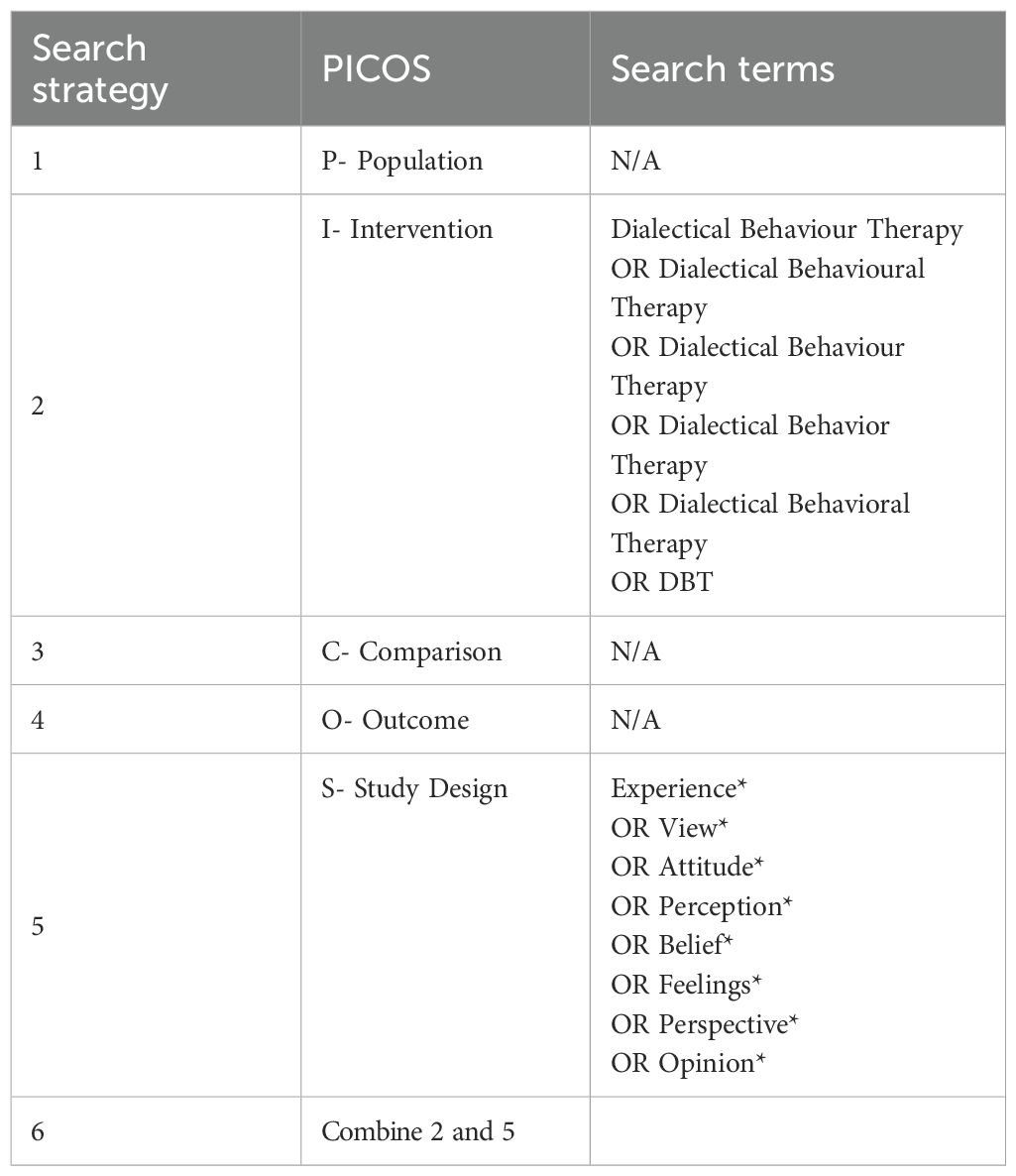

The search strategy was developed in collaboration with the University of Manchester library service, following the Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, and Study Design (PICOS) framework (30) (see Table 1 for details). A preliminary search indicated that terms associated with the intervention and the study design only were required to achieve appropriate sensitivity and specificity. Specific search criteria did not include “qualitative” because the study design related terms already identified qualitative research. Furthermore, the authors wished to include mixed-method papers which met the eligibility criteria.

Five electronic databases were searched in October 2024, with updated searches completed in February 2025, for peer reviewed articles: CINAHL Plus (EBSCOhost), Web of Science (Clarivate), PsycINFO, EMBASE and Medline (all OVID). Databases were selected due to their relevance to this topic area. Searches were conducted using the terms outlined in Table 1, with the use of Boolean operators (“and”, “or”) and were not restricted by publication date. Reference lists of identified papers were also searched.

References were exported into EndNote and duplicates were removed. Title and abstract screening was carried out by the first author, who reviewed papers to confirm they employed qualitative or mixed-methods designs. An independent reviewer carried out a second screening on a random sample of 25% of the identified references. Perfect agreement regarding which papers to include/exclude was found between both reviewers (100%, kappa = 1.0).

2.2 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were included if they 1) involved empirical research with adolescents and/or adults, 2) used either qualitative or mixed-method approaches, 3) were published in English in peer-reviewed journals and 4) included stand-alone data on patient views or experiences (i.e., patient data could be separated from clinicians or family members) of a DBT intervention, which included a group component (either in person or online). Studies featuring group-only or group-based interventions with additional support (e.g., crisis or one-on-one support) were included because these are increasingly offered in services to enhance the real-world applicability of the findings.

Studies were excluded if they focussed on 1) a specific aspect of DBT only (e.g., experiences of “opposite action” skill only), 2) app use only, or 3) radically open DBT [which differs theoretically from traditional DBT; Gilbert et al. (31)]. As group skills training is a core component of the DBT model, studies lacking this element were excluded to maintain fidelity to the model. Conferences, theses and grey literature were excluded to reduce studies lacking peer review and which were therefore potentially conducted with less standardised scientific rigour.

2.3 Methodological quality and risk of bias assessment

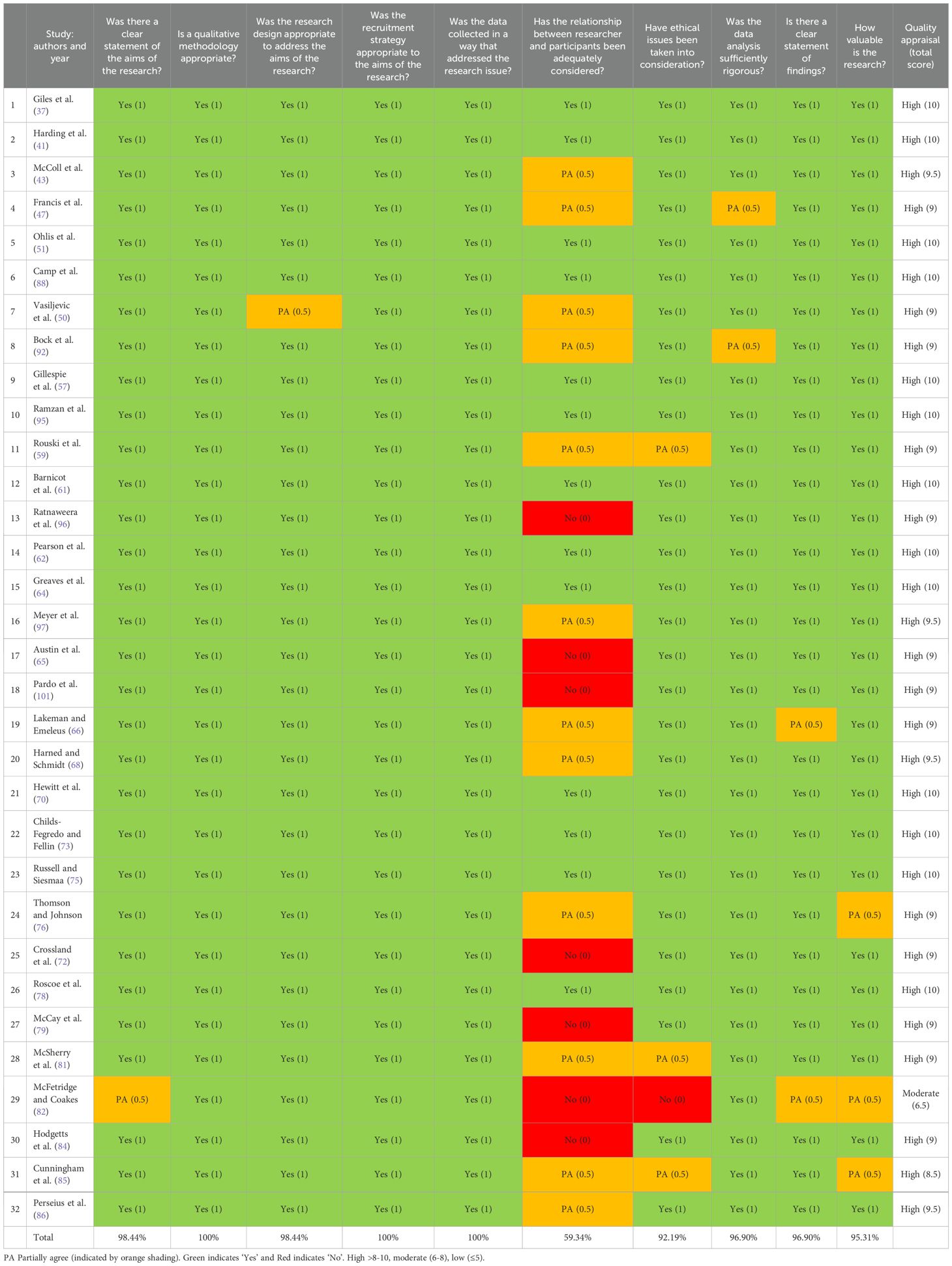

The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (32) for qualitative studies was used to evaluate each study’s methodological quality and risk of bias, by answering its ten questions with “yes”, “no” or “can’t tell”. Questions covered domains such as appropriacy of methodology and ethical considerations. Each item was answered for each study.

To assist with the clearer interpretation of quality and to allow for comparison across studies, the authors decided to assign numerical values to the three possible item responses (No = 0, Partially Agree = 0.5, Yes = 1). Overall methodological quality was then categorised as high (> 8–10), moderate (6–8), or low (≤ 5), allowing for easier reporting of quality [e.g., see Butler et al. and Harries et al. (33, 34)]. Additionally, an independent reviewer quality-rated all included papers, with substantial agreement initially (kappa = 0.65, 93.79%), and almost perfect agreement following discussion of discrepancies (kappa = 0.97, 99.31%).

2.4 Data analysis

Data from the “Results” or “Findings” sections, including participant quotes, author interpretations and themes, were extracted into Microsoft Word, transferred to NVivo, and analysed using Thomas and Harden’s (35) thematic synthesis approach. This approach integrates findings from multiple qualitative studies, including mixed-method studies, by identifying and synthesising common themes, providing insights into the acceptability and appropriateness of services or interventions, which can inform policy and practice (36).

Thematic synthesis was conducted in three stages by the first author. First, all extracted text underwent line-by-line coding. Next, similar descriptive codes were grouped inductively, identifying patterns and variations. Finally, analytical themes were developed by reviewing descriptive themes in relation to the study’s aims.

The analysis was undertaken by the first author (AH), with other members of the team (AW and LG) reviewing the credibility and soundness of the themes, in relation to the included studies. This approach was adopted to ensure a thorough approach and minimise bias. All authors approved the final analysis.

2.5 Reflexivity statement

The authors were three women and one man, from White European backgrounds. The first author was a trainee clinical psychologist with several years of experience in various clinical roles. The second author was an academic researcher specialising in family and parental mental health, the third was a National Health Service (NHS) clinical psychologist with an interest in DBT, while the final author was a clinical psychologist working both in the NHS and academia. Acknowledging the limitations of an all-white research team, we aimed to minimise potential biases towards a white, Western, or Eurocentric perspective through research team discussions and a rigorous, transparent analytical approach.

3 Results

3.1 Study characteristics

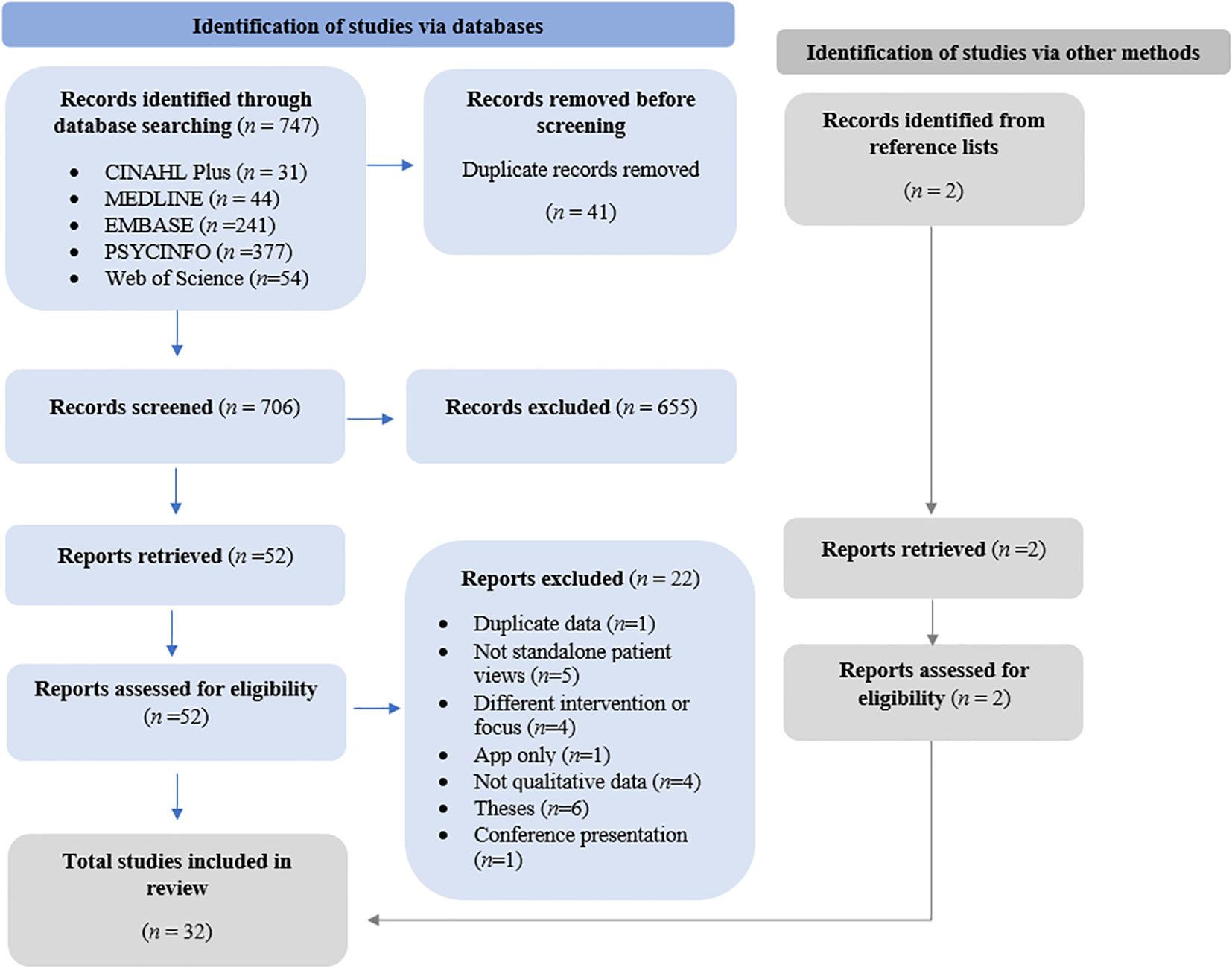

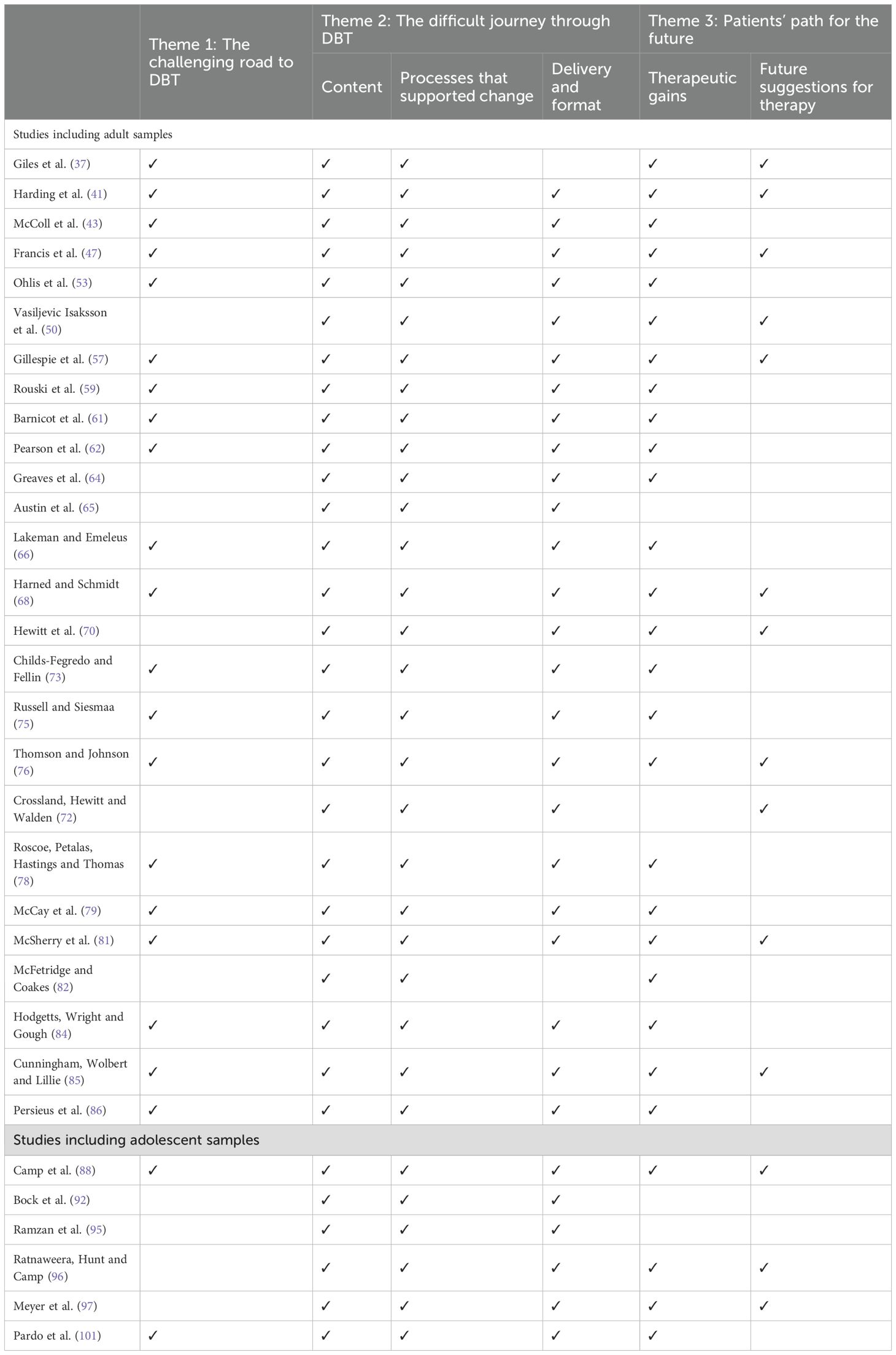

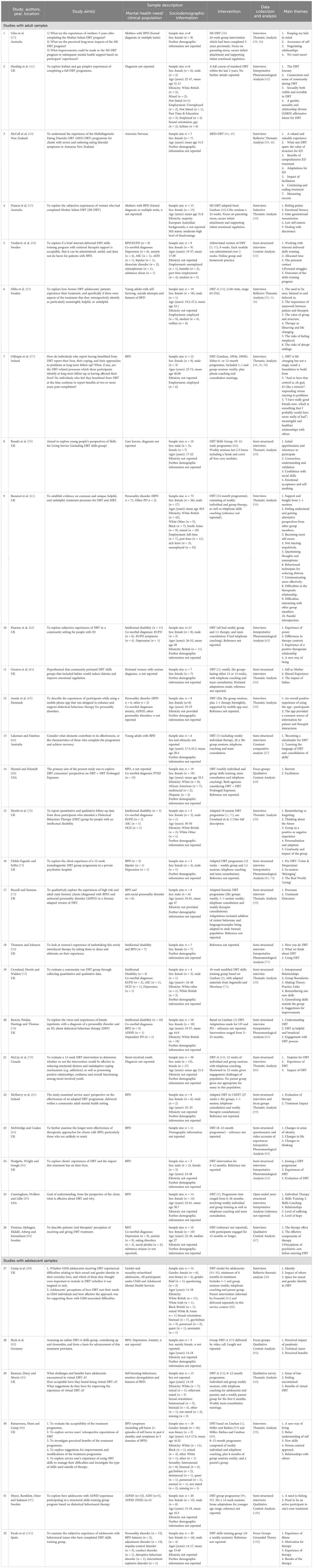

A total of 747 records were identified by the electronic database search and two records were identified via reference list searching, with 41 identified as duplicates (see Figure 1 for details). After screening and review, 32 studies were identified as eligible for inclusion and were synthesised, capturing the perspectives of 414 participants on DBT across ten countries over 21 years (2003–2024).

Sample sizes ranged from three to 73 (see Table 2 for more details). Among studies reporting mental health conditions or clinical populations (n=26), most explored experiences of people with personality disorders or related traits (n=17), including ten specifically on BPD (see Table 2). Other participant groups included intellectual disabilities (n=4), perinatal women (n=3), sexual/gender diversity (n=2), anorexia nervosa (n=1), and ADHD (n=1). Five studies took a transdiagnostic approach or did not limit sampling to specific mental health conditions.

Table 2. Characteristics of included studies presented in reverse chronological order (adult then adolescent papers).

Eleven studies focussed on female perspectives, one on male perspectives, 16 reported mixed-sex views, and four studies did not provide this information. Most studies examined adult experiences (n=26), while six focussed on adolescents or young people (aged 14-27). Ethnicity was rarely reported, with only 12 studies providing data.

Of the 32 studies, 22 used a qualitative approach, while ten employed mixed-methods. Interviews were the most common data collection method (n=26), followed by focus groups (n=2). Three studies combined interviews with focus groups or questionnaires, and one used a qualitative survey. Thematic Analysis was the most frequently used analysis method (n=17), followed by Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) (n=7), Content Analysis (n=5), other approaches (n=2) and Grounded Theory (n=1).

3.2 Methodological quality of the 32 included studies

Thirty-one of the 32 studies were assessed as having high methodological quality, while only one was rated to have moderate methodological quality (82). This study involved a qualitative survey. The methodological quality of included studies is detailed in Table 3.

Thirteen studies received the maximum quality rating: a rating of “yes” for all items (or a score of 10/10). Notably, only 13 of the 32 included studies considered the researcher-participant relationship sufficiently, meaning that item six of the CASP was rated the lowest across studies. Four studies had not sufficiently stated if ethical issues were taken into consideration (59, 81, 82, 85).

3.3 Thematic synthesis

Three over-arching themes, with six sub-themes were developed representing how people experienced DBT: 1) the challenging road to DBT, 2) the difficult journey through DBT and 3) patients’ path for the future. Figure 2 illustrates the themes relationship to each other. Illustrative quotes are provided below each theme, with additional data presented in Table 4. Table 5 presents a matrix of themes, illustrating which themes were present in each study.

3.3.1 Theme 1: the challenging road to DBT

This theme focussed on the constellation of participant experiences prior to DBT, which motivated individuals to engage with the intervention. It describes how difficult journeys characterised by physical and relational trauma, adversity, isolation, and the subsequent harmful coping patterns that emerged led people to DBT.

Across study samples of adults and adolescents, participants described various traumas, including physical and sexual abuse, bullying and hospitalisation for mental health needs. A sense of loneliness (“being the only one in the world feeling this way”, Ohlis et al. (53), p.418), low self-esteem (“I always used to doubt myself and tell myself I wasn’t good enough”, Rouski et al. (59), p.460) and emotional overwhelm (“I tend to internalise everything and then things just boil over”, Francis et al. (47)., p.1250) were common psychological sequelae of trauma, which, linked with harmful coping patterns, often appeared to perpetuate distress. According to participant narratives, further impacts of these traumas, including their impact on functioning (“since then I have no idea how to be an adult really because I just behave like a child when I am stressed”, Francis et al. (47), p.1252), a desire to be relieved from the pain (“it was spiralling down, downwards … I was like, why is this happening, like how do I get out of this?”, McCay et al. (79), p.194) and a desire not to be a victim (“I want to take it and show those morons who abused me that I am the warrior, that I am the victor”, Cunningham et al. (85), p.248) encouraged individuals to seek psychological support and access DBT.

Participant narratives also indicated that increased self-awareness, combined with internally (“I just don’t want to be like this for the rest of my life”, Hodgetts et al. (84), p.174) and externally “I really really want to prove to them [ … ] that I can actually do this”, Russell & Siesmaa (75), p.51) focussed desires to change these patterns facilitated initial engagement, alongside sustaining participation with DBT. Furthermore, self-recognition of functioning abilities and attempts to cope were reported to have a negative impact on their lives, and to influence motivation and commitment to the intervention. Many individuals described that they had previously engaged in therapy without success, likely because first-line interventions did not address their complex needs, seemingly leading to an increased willingness to engage with DBT.

Overall, this theme illustrates the difficult and often traumatic experiences that led individuals to engage with DBT, highlighting how a combination of personal struggles, harmful coping mechanisms, and a deep desire for change appeared to drive their engagement with this intervention.

3.3.2 Theme 2: the difficult journey through DBT

This theme, comprising three sub-themes, describes the content and processes of DBT that were reported to affect psychological recovery, thereby exploring how practical aspects, such as mode of delivery, were perceived as helping or hindering progress.

3.3.2.1 Sub-theme 2.1: from theory to practice

The content of DBT, particularly the structured worksheets and skill-building resources, was described as integral to navigating the journey through DBT. Skills and content from all four modules (mindfulness, interpersonal effectiveness, distress tolerance and emotion regulation) helped individuals to better cope with distress and challenges in their daily lives, through improved impulse control, self-regulation and self-awareness. Module content enabled individuals to learn how to pause and process thoughts and feelings with greater clarity, enabling different behavioural responses to be selected.

Particularly helpful was having a variety of skills to choose from (“I can get myself into wise mind and use the skills. And then if I need to blow off steam, I can just go through the skills and pick out the ones to calm myself down”, Cunningham et al. (85), p.2005) and facilitators giving relatable examples (“Role play [ … ] you know things that we would have to cope with. Like say we are in a supermarket or something” Roscoe et al. (78), p.271). These factors allowed application of learned content more broadly in participants' lives, supporting skill use in various situations. As a result, skills were practiced more often and became second nature:

“Since the beginning what he taught us was what to do in situations like that, so I would always try to put it to the test, I even got the point where I could do it without thinking” (Pardo et al. (101), p.6).

Furthermore, the tangible and practical nature of DBT skills, and how these were learnt contributed to psychological change. The learning process including the use of physical items (such as sensory boxes and diary cards) and practical strategies (such as grounding or mindfulness techniques) helped individuals to better process and apply the new knowledge to their lives. Participants elaborated on how structured resources were useful, because they helped track progress and maintain motivation because people could visually see their progress week by week:

“…when it first started, I used to have quite high scores on my diary card, mmm … and now I only have like ones and twos…!” (Roscoe et al. (78), p.271).

Participants also reported that information being taught in a way that felt less abstract and more accessible contributed to psychological recovery. However, some aspects were experienced as less helpful. Participants found the DBT terminology complex (“like a lot of the jargon that’s read out to you – does that come with subtitles?”, McSherry et al. (81), p.2) or the therapeutic concepts too abstract (“um I didn’t like the mindfulness bit when they said you were hot headed and in a hot mind or a cool mind. I didn’t understand that very well”, Crossland-Hewitt (72), p.212).

3.3.2.2 Sub-theme 2.2: transformative relationships - self and others

While undertaking DBT, perhaps unsurprisingly, relational factors played a crucial role in the therapeutic process, including peer support which emerged as a significant influence, with group members learning from one another’s experiences, as intended by Linehan (1, 2, 5):

“…so, we give each other tips and exchange ideas and sort of: ‘I liked this, it might work for you too” (Ohlis et al. (53), p. 418).

While DBT structure varied across studies, common core components, such as crisis support and the support of the group, were important because these components were reported to reduce feelings of isolation, which helped maintain engagement.

Participant narratives also showed that validation from therapists was highly valued by participants, especially given their trauma histories, because this validation allowed them to feel accepted for who they were. However, importantly, therapeutic relationships that provided both psychological safety and challenge were pivotal in fostering behavioural change, because these relationships they facilitated growth and challenged individuals with a history of avoidance and interpersonal conflict, to make behavioural changes in a relatively comfortable way:

“My therapist is fantastic because he doesn’t sugar-coat anything, he tells me how it is [ … ] if I don’t want to come to therapy, he helps me understand where that feeling is coming from and to evaluate the impact that not coming would have” (Barnicot et al. (61), p.217).

Participant narratives indicated that DBT had led to a dramatic shift in their perspective, with their view of themselves, others and the world changing through the DBT experience. Attitudes shifted towards greater self-acceptance, which often led to improved symptoms. An increased sense of self-confidence, purpose and hope for the future was reported, which contributed to psychological recovery and long-term maintenance of gains:

“It’s thanks to DBT that I’m alive today … now I can see myself as a person that shall go on living … I don’t think I’d be around anymore, if it wasn’t for DBT…” (Perseius et al. (86), p222).

3.3.2.3 Sub-theme 2.3: scaffolding and supporting change

Additionally, the structure and format of DBT, which are essential elements of the broader therapeutic journey, played a significant role in shaping participants’ progress.

Groups were described as engaging (“some balloons in the air and also when we watched these short [film] clips. I think that’s fun.”, Meyer et al. (97), p.674). Individual therapy was described as intense and difficult, meaning that the more entertaining approach taken within group delivery was experienced as helping to prevent individuals falling into their previous patterns of isolation, avoidance and overwhelm:

“To feel as though you are not alone in the world with your problems [ … ] I feel very isolated in the community [ … ] DBT helped me to feel part of something” (Russell & Siesmaa (75), p.52).

Concerns about confidentiality and the prevention of discussing or utilising self-harm commonly being a group rule were described as challenging aspects, because some individuals described feeling unsafe, and pre-existing feelings of uncertainty and fear were reinforced:

“Even now that frustrates me, cos I think, what if I’m not allowed to self-harm, what do I do … it’s not an option anymore” (Hodgetts et al. (84), p.175).

Polarised views regarding online delivery reflected individual circumstances. For some, online delivery promoted attendance and was helpful (“I thought it was very good that it was online based, because I did not have to keep any appointments”, Vasiljevic et al. (50), p.60), meaning their therapeutic exposure, and therefore possibly their therapeutic gains, increased. Others described how online delivery facilitated disengagement (“was less willing to work on things over a video call, whereas when we had face-to-face sessions, I was always more enthusiastic and ready to talk and work” (Ramzan et al. (95), p.8). Importantly, views regarding delivery format highlighted the increased gains and engagement when intervention aligned with patient preferences.

Together, the content, relational processes, and delivery format of DBT each played a crucial role in participants’ engagement with the intervention. While each element presented unique obstacles, they ultimately contributed to the transformative process of learning new coping strategies and gaining better control over emotional responses.

3.3.3 Theme 3: patients’ path for the future

This theme emerged through people reflecting on their DBT intervention ending and it consists of two sub-themes: therapeutic gains and future suggestions for therapy. These sub-themes capture the perceived transformative impact of DBT and offer ideas for future intervention refinement.

3.3.3.1 Sub-theme 3.1: therapeutic gains

As individuals reflected on their experiences of DBT, the transformative impact of the intervention became apparent. Individuals reported numerous relational gains, including fewer conflicts with others and improved parenting skills (“I’m more assertive with the way that I speak to people and so people aren’t treating me the way they were and I’m not bottling it in and getting angry at them”, Francis et al. (47), p.1255). Often these relational gains stemmed from personal gains, such as decreased impulsivity, increased emotion regulation ability, the development of adaptive coping skills, or improved self-esteem and compassion, leading to greater prioritisation of their own needs:

“Something I wouldn’t have done before DBT, I am thinking of myself and what’s best for me and my whole family … The whole time gently pulling back because I think it will be healthier for me” (Gillespie et al. (57), p.9).

An increased sense of self-kindness was experienced by many, with individuals learning to show themselves greater compassion when they were struggling. This compassion often coincided with better boundaries, and subsequently less emotional distress:

“I have come to realise I do not judge myself in the same way as everyone else does. I’ve been so super hard on myself. I recognise now that I have to judge myself the same way I judge others and be kind to others” (Meyer et al. (97), p.675).

New skills had incredible value in people’s lives, which was evident across the reviewed studies, with some people reflecting how they would not want to lose them in future. Additionally, some studies considered the long-term impact of therapy, with the value still evident years later, while the importance of skill maintenance was reflected on to maintain therapeutic gain:

“One thing I’ve learned is you just gotta keep doing them. Like, if you don’t keep up this, it’s like learning a language, if you don’t keep it up, you lose it” (McColl et al. (43), p. 8).

3.3.3.2 Sub-theme 3.2: future directions

While participants expressed overall satisfaction with their experiences of DBT, several shared suggestions to enhance the therapeutic journey for future participants. For example, some reported that their programme should have been longer, or offered refresher sessions, to help embed the skills more.

Several participants expressed that simplifying language and using more relatable concepts was needed, given it would prevent people feeling inferior and reduce attrition, particularly for those who had previously struggled with traditional therapy approaches:

“I was ready to quit because I couldn’t get these big words, and I didn’t know some of the language” (Cunningham et al. (85), p.253).

Some participants reported feeling that broader representation within therapists would be beneficial. If group members had seen their characteristics better reflected in group facilitators, they expressed that it might have increased therapeutic gain given that therapeutic relationships were a process that supported change:

“I found that a lot of the [therapists] are like cis-gendered or heterosexual. So maybe if there was some … queer or … transgender or non-binary [therapists] in DBT” (Camp et al. (88), p.13).

Overall, this theme captured participants’ reflections on the lasting impact of DBT, including personal growth, improved relationships and increased self-compassion. It also considered refinements for future intervention delivery to enhance these impacts further.

4 Discussion

This systematic review synthesised data from 32 studies to identify key themes relating to patient experiences of DBT, across mental health conditions and age groups. It considered the processes (peer support, validation, psychological safety, changed perspectives, increased sense of purpose and hope) patients perceived as contributing to, or impeding, therapeutic change, as well as considering ways to enhance DBT offers to maximise patient gains in the future. The findings highlight the significance of both pre-treatment (trauma, self-awareness, coping behaviours and previous therapy) and in-treatment (structured resources, modular content, practical skills and relatable examples) patient experiences in shaping engagement and reported psychological outcomes, emphasising how these specific aspects of DBT content and delivery can either promote or hinder progress transdiagnostically.

Findings from previous reviews of DBT (e.g., (26, 27)) highlighted the importance of skill development, hope, and the therapeutic relationship. The current review builds on this identified importance by offering a deeper understanding of the experiential aspects of DBT that contribute to transdiagnostic change, such as the development of self-compassion, sustained motivation, and peer connection, across both adult and adolescent populations. The current review findings offer a unique contribution to clinical psychology and can be operationalised through trauma-informed clinical training, experiential learning, supervision that emphasises therapist relatability, and service development that supports diverse, accessible, and modular DBT delivery.

Relational factors, such as feeling safe, validated, and connected to both peers and therapists, have been recognised as contributing to therapeutic gains in various group therapies (103, 104), a sentiment supported by the current review. However, the current review also found that certain DBT components, such as crisis support, bolstered these feelings of safety and connection, ultimately amplifying reported therapeutic outcomes for some individuals. Furthermore, given the transdiagnostic experiences of trauma in the 32 reviewed studies, feelings of low self-esteem and fear were typically prevalent for those undertaking DBT. For these participants, experiencing validation and safety in group therapy may be particularly impactful compared to other clinical populations (105).

The current review highlights the value of skills across all four DBT group components, with patients often benefiting from the variety offered, underscoring the strengths of DBT’s modular design (5, 48). Notably, participants frequently reflected on using these skills in everyday life. This focus on practical skill application contrasts with previous research, which often considers DBT’s impact through outcomes like reduced self-injury or mood instability (17, 106, 107). As DBT’s treatment hierarchy, understandably, prioritises self-injury and suicidality, these measures have traditionally dominated research. However, with DBT’s growing use among more diverse clinical groups, in which such behaviours may be less common, there is a need to expand outcome measures. The current review suggests that in these cases, exploration of real-world skill use and emotion regulation through interview may better capture DBT’s therapeutic impact.

Variation in DBT formats across the included studies, such as stand-alone skills training groups versus full DBT programmes, may have influenced the review’s findings. These differences in treatment intensity, structure, and therapeutic components (e.g., absence of individual therapy or phone coaching in skills-only formats) could have shaped how participants experienced the intervention and the specific mechanisms of change they reported. As a result, some themes identified in the synthesis might reflect format-specific experiences rather than transferable features of DBT as a whole.

4.1 Clinical implications

Clinical recommendations, developed based on the identified themes and grounded in qualitative data, are provided to inform the delivery of DBT and guide practice (see Table 6 for details). As this review highlights the importance of aligning intervention offers with patient preferences, and the variation in patient preferences (e.g., regarding favoured delivery and modules), commissioners and clinicians could consider adapting these elements based on patient feedback and service need, as recommended in Table 6. At a broader level, these findings may also inform public policy by supporting investment in accessible, modular, and patient-centred DBT programmes that foster self-compassion, sustained motivation, and peer connection across diverse populations, thereby shaping equitable mental health service provision and guiding resource allocation at a system’s level.

4.2 Strengths, limitations and future research

This review involved a comprehensive and systematic search, with data synthesised from 32 studies, reflecting the voices of 414 people, from ten countries, spanning 21 years. This review deliberately included diverse voices across age, sex, and clinical groups in an attempt to provide a holistic view of experiences. Furthermore, 31 of the 32 included studies were rated as having high methodological quality on the CASP. The inclusion of a second independent reviewer further supported the review’s strong methodological rigour (29). However, the lack of methodology exclusion criteria enabled the inclusion of a lower quality study (82), which future studies may seek to exclude.

The CASP tool is widely used and was chosen to enhance methodological rigour and credibility, ensuring the synthesis was based on high-quality evidence. However, subjectivity and quality concerns regarding the CASP are acknowledged, for example, its lack of sensitivity to validity when compared with other tools (108). Furthermore, although selected for their relevance to the topic area, the authors acknowledge possible limitations associated with the databases used; for example, that they might have over-prepresented research from high income countries leading to a skewed sample. In addition, this review did not incorporate trial registries (e.g., CENTRAL, ICTRP, ClinicalTrials.gov) or grey literature sources such as dissertation repositories. Including these might have yielded a more comprehensive dataset and ensured broader coverage of the existing evidence base. While we opted for the inclusion of peer reviewed academic literature only, a future review may consider the inclusion of grey literature.

The included studies varied substantially in intervention length (ranging from three to 36 months), delivery model (online vs. in-person), and treatment structure (e.g., stand-alone skills groups vs. full DBT programmes). This heterogeneity in intervention design and implementation might have contributed to variability in outcomes, complicating the synthesis and interpretation of reported effectiveness.

Ethnicity was reported in only 12 of the 32 studies included in the systematic review, suggesting a significant gap in the representation and reporting of participant diversity. This lack of demographic detail raises concerns about the potential homogeneity of study populations and might limit the transferability of findings across ethnically diverse groups. These omissions underscore the importance of applying an intersectional lens in research and highlight the need for more inclusive clinical care practices that account for the complex ways in which ethnicity, culture, and other identity factors shape health outcomes.

As non-English studies were excluded due to time and resource constraints, potentially introducing publication and language biases, future reviews may want to include studies published in other languages. Nevertheless, included studies spanned ten countries, six of which do not have English as their primary language.

This review also synthesised various intervention formats that included a group element, including traditional and skills group only DBT. Future studies may wish to select one particular variation to focus on to explore if there are any unique benefits or challenges associated with each, offering a deeper understanding of their relative value.

4.3 Conclusion

To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first review to comprehensively synthesise qualitative research on patient experiences of DBT, including a group component, across mental health conditions and clinical populations, as well as age groups from adolescence to adulthood. The findings supported the previously identified multifaceted impact of DBT on adolescents’ and adults’ emotional and relational well-being transdiagnostically. These findings build on previous reviews by highlighting DBT’s transdiagnostic impact on self-compassion, motivation, and real-world skill application. Relational elements, such as feeling validated and psychologically safe, were particularly important for individuals with trauma histories, reinforcing the value of DBT’s structure and delivery. Furthermore, given patients' complexity offering DBT in flexible formats is beneficial to improve accessibility. Notably, participants described everyday use of skills as a key therapeutic outcome, suggesting future research should include measures of functional change, not just symptom reduction. Clinical recommendations are provided to guide more responsive and inclusive DBT delivery, promoting long-term therapeutic benefit and enhancing DBT’s ability in addressing the diverse needs of patients across different backgrounds and settings.

Data availability statement

Publicly available datasets were analysed in this study. All data can be found in tables in the main text.

Author contributions

AH: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LG: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. BO’C: Investigation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. AW: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The University of Manchester covered the cost of the publication fee.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Clair Davison for her support as an independent reviewer, with screening and quality appraisal of the literature search results. Clair was a Trainee Clinical Psychologist from the University of Manchester.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2025.1640341/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Linehan MM. Cognitive-behavioral therapy of borderline personality disorder. USA: Guilford Press (1993).

2. Linehan MM. Skills training manual for treating borderline personality disorder. USA: Guilford Press (1993).

3. Bohus M, Haaf B, Simms T, Limberger MF, Schmahl C, Unckel C, et al. Effectiveness of inpatient dialectical behavioral therapy for borderline personality disorder: A controlled trial. Behav Res Ther. (2004) 42:487–95. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(03)00174-8

4. Linehan MM, Comtois KA, Murray AM, Brown MZ, Gallop RJ, Heard HL, et al. Two-year randomized controlled trial and follow-up of dialectical behavior therapy vs. therapy by experts for suicidal behaviors and borderline personality disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (2006) 63:757–66. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.7.757

6. Linehan MM, Korslund KE, Harned MS, Gallop RJ, Lungu A, Neacsiu AD, et al. Dialectical behavior therapy for high suicide risk in individuals with borderline personality disorder: A randomized clinical trial and component analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. (2015) 72:475–82. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.3039

7. Rozakou-Soumalia N, Dârvariu Ş, and Sjögren JM. Dialectical behaviour therapy improves emotion dysregulation mainly in binge eating disorder and bulimia nervosa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pers Med. (2021) 11:931. doi: 10.3390/jpm11090931

8. Halmøy A, Ring AE, Gjestad R, Møller M, Ubostad B, Lien T, et al. Dialectical behavioral therapy-based group treatment versus treatment as usual for adults with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: A multicenter randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry. (2022) 22:738. doi: 10.1186/s12888-022-04356-6

9. Harned MS, Korslund KE, and Linehan MM. A pilot randomized controlled trial of dialectical behavior therapy with and without the dialectical behavior therapy prolonged exposure protocol for suicidal and self-injuring women with borderline personality disorder and PTSD. Behav Res Ther. (2014) 55:7–17. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2014.01.008

10. Bohus M, Schmahl C, Fydrich T, Steil R, Müller-Engelmann M, Herzog J, et al. A research programme to evaluate DBT-PTSD, a modular treatment approach for complex PTSD after childhood abuse. Borderline Pers Disord Emot Dysregul. (2019) 6:7. doi: 10.1186/s40479-019-0099-y

11. Maercker A, Cloitre M, Bachem R, Schlumpf YR, Khoury B, Hitchcock C, et al. Complex post-traumatic stress disorder. Lancet. (2022) 400:60–72. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00821-2

12. Valentine SE, Smith AM, and Stewart K. A review of the empirical evidence for DBT skills training as a stand-alone intervention. In: The Handbook of Dialectical Behavior Therapy USA (2020). p. 325–58. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-816384-9.00015-4

13. Delaquis CP, Joyce KM, Zalewski M, Katz L, Sulymka J, Agostinho T, et al. Dialectical behaviour therapy skills training groups for common mental health disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Behav Res Ther. (2020) 135:103732. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.12.062

14. Ciesinski NK, Sorgi-Wilson KM, Cheung JC, Chen EY, and McCloskey MS. The effect of dialectical behavior therapy on anger and aggressive behavior: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Behav Res Ther. (2022) 154:104122. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2022.104122

15. Salles BM, Maturana de Souza W, Dos Santos VA, and Mograbi DC. Effects of DBT-based interventions on alexithymia: A systematic review. Cognit Behav Ther. (2023) 52:110–31. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2022.2117734

16. Hernandez-Bustamante M, Cjuno J, Hernández RM, and Ponce-Meza JC. Efficacy of dialectical behavior therapy in the treatment of borderline personality disorder: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Iran J Psychiatry. (2024) 19:119. doi: 10.18502/ijps.v19i1.14347

17. Kothgassner OD, Goreis A, Robinson K, Huscsava MM, Schmahl C, and Plener PL. Efficacy of dialectical behavior therapy for adolescent self-harm and suicidal ideation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med. (2021) 51:1057–67. doi: 10.1017/S0033291721001355

18. McPherson S, Wicks C, and Tercelli I. Patient experiences of psychological therapy for depression: A qualitative metasynthesis. BMC Psychiatry. (2020) 20:1–18. doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-02682-1

19. Batbaatar E, Dorjdagva J, Luvsannyam A, Savino MM, and Amenta P. Determinants of patient satisfaction: A systematic review. Perspect Public Health. (2016) 137:89–101. doi: 10.1177/1757913916634136

20. McMain SF, Guimond T, Barnhart R, Habinski L, and Streiner DL. A randomized trial of brief dialectical behaviour therapy skills training in suicidal patients suffering from borderline disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. (2017) 135:138–48. doi: 10.1111/acps.12664

21. Neacsiu AD, Eberle JW, Kramer R, Wiesmann T, and Linehan MM. Dialectical behavior therapy skills for transdiagnostic emotion dysregulation: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Behav Res Ther. (2014) 59:40–51. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2014.05.005

22. Sambrook S, Abba N, and Chadwick P. Evaluation of DBT emotional coping skills groups for people with parasuicidal behaviours. Behav Cognit Psychother. (2006) 35:241–4. doi: 10.1017/S1352465806003298

23. Cowperthwait CM, Wyatt KP, Fang CM, and Neacsiu AD. Skills training in DBT: Principles and practicalities. In: Swales MA, editor. The Oxford Handbook of Dialectical Behaviour Therapy. Oxford University Press, Oxford (2019). p. 167–200.

24. Lyng J, Wilks CR, Arundel C, Cotter P, and Linehan MM. Standalone DBT group skills training versus standard (i.e. all modes) DBT for borderline personality disorder: A naturalistic comparison. Community Ment Health J. (2019) 55:1394–404. doi: 10.1007/s10597-019-00485-7

25. McKay JG. Dialectical behavior therapy skills group component as a stand-alone treatment for children, adolescents, and university students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Chicago School of Professional Psychology, Chicago (2023). doctoral dissertation.

26. Little H, Tickle A, and das Nair R. Process and impact of dialectical behaviour therapy: A systematic review of perceptions of clients with a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder. Psychol Psychother. (2018) 91:278–301. doi: 10.1111/papt.12156

27. Middlehurst R, Moghaddam N, Dawson DL, and Reeve A. Perceived change processes in dialectical behaviour therapy from the perspective of clients with a diagnosis or traits of borderline personality disorder: A systematic literature review. Clin Psychol Psychother. (2024) 31:e3038. doi: 10.1002/cpp.3038

28. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int J Surg. (2021) 88:105906. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71

29. Tong A, Flemming K, McInnes E, Oliver S, and Craig J. Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Med Res Methodol. (2012) 12:181. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-12-181

30. Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, et al. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Version 6.3. London: Cochrane (2021). Available online at: https://training.cochrane.org/handbook (Accessed October 14, 2024).

31. Gilbert K, Hall K, and Codd RT. Radically open dialectical behavior therapy: Social signaling, transdiagnostic utility and current evidence. Psychol Res Behav Manage. (2020) 13:19–28. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S201848

32. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP tools and checklists (2025). Available online at: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/ (Accessed 2024 Dec 5).

33. Butler J, Gregg L, Calam R, and Wittkowski A. Parents’ perceptions and experiences of parenting programmes: A systematic review and metasynthesis of the qualitative literature. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. (2020) 23:176–204. doi: 10.1007/s10567-019-00307-y

34. Harries CI, Smith DM, Gregg L, and Wittkowski A. Parenting and serious mental illness (SMI): A systematic review and metasynthesis. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. (2023) 26:303–42. doi: 10.1007/s10567-023-00427-6

35. Thomas J and Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. (2008) 8:45. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-8-45

36. Barnett-Page E and Thomas J. Methods for the synthesis of qualitative research: A critical review. BMC Med Res Methodol. (2009) 9:59. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-9-59

37. Giles A, Sved Williams A, Webb S, Drioli-Phillips P, and Winter A. A thematic analysis of the subjective experiences of mothers with borderline personality disorder who completed Mother-Infant Dialectical Behaviour Therapy: a 3-year follow-up. Borderline Pers Disord Emot Dysregul. (2024) 11:25. doi: 10.1186/s40479-024-00269-w

38. Sved Williams A and Apter G. Helping mothers with the emotional dysregulation of borderline personality disorder and their infants in primary care settings. Aust Fam Physician. (2017) 46:669–72. doi: 10.3316/informit.075046366263492

39. Braun V and Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. (2006) 3:77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

41. Harding C, Pratt D, and Lea J. All the horrible emotions have passed, I still remained, and I was safe”: A qualitative study of lesbian and gay people’s lived experience of completing a full Dialectical Behaviour Therapy programme. Psychol Psychother. (2025) 98:1–24. doi: 10.1111/papt.12555

42. Smith JA and Osborn M. Interpretative phenomenological analysis. In: Smith JA, editor. Qualitative psychology: A practical guide to research methods. UK/USA: Sage (2003). p. 51–80.

43. McColl C, Hindle S, and Donkin L. I mean, it kind of saved my life, to be honest”: A qualitative study of participants’ views of a dialectical behaviour therapy for multidiagnostic eating disorders programme. J Eat Disord. (2024) 12:186. doi: 10.1186/s40337-024-01142-5

44. Wisniewski L and Ben-Porath DD. Dialectical behavior therapy and eating disorders: The use of contingency management procedures to manage dialectical dilemmas. Am J Psychother. (2015) 69:129–40. doi: 10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.2015.69.2.129

45. Donkin L, McColl C, and Hindle S. Life-saving,” but was it clinically effective? An analysis of psychometrics and clinical data of a pilot dialectical behaviour therapy for multiproblematic restrictive eating disorders group programme. J Eat Disord. (2024) 12:186. doi: 10.1186/s40337-024-01142-5

46. Clarke V and Braun V. Thematic analysis. J Posit Psychol. (2017) 12:297–8. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2016.1262613

47. Francis JL, Sawyer A, Roberts R, Yelland C, Drioli-Phillips P, and Sved Williams AE. Mothers with borderline personality disorders’ experiences of mother–infant dialectical behavior therapy. J Clin Psychol. (2023) 79:1245–60. doi: 10.1002/jclp.23465

49. Braun V and Clarke V. Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. London: Sage (2013).

50. Vasiljevic S, Isaksson M, Wolf-Arehult M, Öster C, Ramklint M, and Isaksson J. Brief internet-delivered skills training based on DBT for adults with borderline personality disorder: A feasibility study. Nord J Psychiatry. (2023) 77:55–64. doi: 10.1080/08039488.2022.2055791

51. Linehan MM. Dialektisk beteendeterapi: Arbetsblad för färdighetsträning. 1st ed. Sweden: Natur Kultur Akademisk (2016).

52. Graneheim UH and Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures, and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. (2004) 24:105–12. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001

53. Ohlis A, Bjureberg J, Ojala O, Kerj E, Hallek C, Fruzzetti AE, et al. Experiences of dialectical behaviour therapy for adolescents: A qualitative analysis. Psychol Psychother. (2023) 96:410–25. doi: 10.1111/papt.12447

54. Miller AL, Rathus JH, and Linehan MM. Dialectical behavior therapy with suicidal adolescents. USA: Guilford Press (2007).

55. Braun V and Clarke V. (Mis)conceptualising themes, thematic analysis, and other problems with Fugard and Potts’ (2015) sample-size tool for thematic analysis. Int J Soc Res Methodol. (2016) 19:739–43. doi: 10.1080/13645579.2016.1195588

56. Braun V and Clarke V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual Res Sport Exerc Health. (2019) 11:589–97. doi: 10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

57. Gillespie C, Murphy M, Kells M, and Flynn D. Individuals who report having benefitted from dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT): A qualitative exploration of processes and experiences at long-term follow-up. Front Psychol. (2022) 13:904756. doi: 10.1186/s40479-022-00179-9

58. Braun V and Clarke V. Thematic analysis. In: Cooper H, editor. APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology. American Psychological Association, Washington (DC (2012). p. 57–71. doi: 10.1037/13620-004

59. Rouski C, Yu S, Edwards A, Hibbert L, Covax A, Knowles SF, et al. Dialectical behaviour therapy ‘Skills for Living’ for young people leaving care: A qualitative exploration of participants’ experiences. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. (2022) 27:455–65. doi: 10.1177/13591045211056690

60. Andrew E, Williams J, and Waters C. Dialectical behaviour therapy and attachment: Vehicles for the development of resilience in young people leaving the care system. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. (2014) 19:503–15. doi: 10.1177/1359104513508964

61. Barnicot K, Redknap C, Coath F, Hommel J, Couldrey L, and Crawford M. Patient experiences of therapy for borderline personality disorder: Commonalities and differences between dialectical behaviour therapy and mentalization-based therapy and relation to outcomes. Psychol Psychother. (2022) 95:212–33. doi: 10.1111/papt.12362

62. Pearson A, Austin K, Rose N, and Rose J. Experiences of dialectical behaviour therapy in a community setting for individuals with intellectual disabilities. Int J Dev Disabil. (2021) 67:283–95. doi: 10.1080/20473869.2019.1651143

63. Smith JA, Flowers P, and Larkin M. Interpretative phenomenological analysis: Theory, research, practice. UK/USA: Sage Publications (2009).

64. Greaves AE, McKenzie H, O’Brien R, Roberts A, and Alexander K. The impact of including babies on the effectiveness of dialectical behaviour therapy skills groups in a community perinatal service. Behav Cognit Psychother. (2021) 49:172–84. doi: 10.1017/S1352465820000673

65. Austin SF, Jansen JE, Petersen CJ, Jensen R, and Simonsen E. Mobile app integration into dialectical behavior therapy for persons with borderline personality disorder: Qualitative and quantitative study. JMIR Ment Health. (2020) 7:e14913. doi: 10.2196/14913

66. Lakeman R and Emeleus M. The process of recovery and change in a dialectical behaviour therapy programme for youth. Int J Ment Health Nurs. (2020) 29:1092–100. doi: 10.1111/inm.12749

67. Glaser BG and Strauss AL. The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. London: Routledge (2017). doi: 10.4324/9780203793206

68. Harned MS and Schmidt SC. Perspectives on a stage-based treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder among dialectical behavior therapy consumers in public mental health settings. Community Ment Health J. (2019) 55:409–19. doi: 10.1007/s10597-018-0358-1

69. Elo S and Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. (2008) 62:107–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

70. Hewitt O, Atkinson-Jones K, Gregory H, and Hollyman J. What happens next? A 2-year follow-up study into the outcomes and experiences of an adapted dialectical behaviour therapy skills training group for people with intellectual disabilities. Br J Learn Disabil. (2019) 47:126–33. doi: 10.1111/bld.12267

71. Ingamells B and Morrissey C. I can feel good: Skills training for people with intellectual disabilities and problems managing emotions. Brighton: Pavilion Publishing Ltd (2014).

72. Crossland T, Hewitt O, and Walden S. Outcomes and experiences of an adapted dialectic behaviour therapy skills training group for people with intellectual disabilities. Br J Learn Disabil. (2017) 45:208–16. doi: 10.1111/bld.12194

73. Childs-Fegredo J and Fellin L. ‘Everyone should do it’: Client experience of a 12-week dialectical behaviour therapy group programme – An interpretative phenomenological analysis. Couns Psychother Res. (2018) 18:319–31. doi: 10.1002/capr.12178

74. Smith JA. Reflecting on the development of Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis and its contribution to qualitative research in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. (2004) 1:39–54. doi: 10.1191/1478088704qp004oa

75. Russell S and Siesmaa B. The experience of forensic males in dialectical behaviour therapy (forensic version): A qualitative exploratory study. J Forensic Pract. (2017) 19:47–58. doi: 10.1108/JFP-01-2016-0003

76. Thomson M and Johnson P. Experiences of women with learning disabilities undergoing dialectical behaviour therapy in a secure service. Br J Learn Disabil. (2017) 45:106–13. doi: 10.1111/bld.12180

77. Greenhalgh T and Taylor R. How to read a paper: Papers that go beyond numbers (qualitative research). BMJ. (1997) 315:740–3. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7110.740

78. Roscoe P, Petalas M, Hastings R, and Thomas C. Dialectical behaviour therapy in an inpatient unit for women with a learning disability: Service users’ perspectives. J Intellect Disabil. (2016) 20:263–80. doi: 10.1177/1744629515614192

79. McCay E, Carter C, Aiello A, Quesnel S, Langley J, Hwang S, et al. Dialectical behavior therapy as a catalyst for change in street-involved youth: A mixed methods study. Child Youth Serv Rev. (2015) 58:187–99. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2015.09.021

80. Miles MB and Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. USA: Sage Publications (1994).

81. McSherry P, O’Connor C, Hevey D, and Gibbons P. Service user experience of adapted dialectical behaviour therapy in a community adult mental health setting. J Ment Health. (2012) 21:539–47. doi: 10.3109/09638237.2011.651660

82. McFetridge M and Coakes J. The longer-term clinical outcomes of a DBT-informed residential therapeutic community; An evaluation and reunion. Ther Communities. (2010) 31:406–16.

83. Conrad P. The experience of illness: Recent and new directions. Res Sociol Health Care. (1987) 6:1–31.

84. Hodgetts A, Wright J, and Gough A. Clients with borderline personality disorder: Exploring their experiences of dialectical behaviour therapy. Couns Psychother Res. (2007) 7:172–7. doi: 10.1080/14733140701575036

85. Cunningham K, Wolbert R, and Lillie B. It’s about me solving my problems: Clients’ assessments of dialectical behavior therapy. Cognit Behav Pract. (2004) 11:248–56. doi: 10.1016/S1077-7229(04)80036-1

86. Perseius KI, Öjehagen A, Ekdahl S, Åsberg M, and Samuelsson M. Treatment of suicidal and deliberate self-harming patients with borderline personality disorder using dialectical behavioral therapy: the patients’ and the therapists’ perceptions. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. (2003) 17:218–27. doi: 10.1016/S0883-9417(03)00093-1

87. Burnard P. A method of analysing interview transcripts in qualitative research. Nurse Educ Today. (1991) 11:461–6. doi: 10.1016/0260-6917(91)90009-Y

88. Camp J, Morris A, Wilde H, Smith P, and Rimes KA. Gender-and sexuality-minoritised adolescents in DBT: A reflexive thematic analysis of minority-specific treatment targets and experience. Cognit Behav Ther. (2023) 16:e36. doi: 10.1017/S1754470X23000326

89. Miller AL, Rathus JH, and Linehan MM. 1st ed. In: Dialectical behavior therapy with suicidal adolescents. USA: Guilford Press (2006).

91. Fruzzetti AE. Dialectical behaviour therapy with parents, couples, and families to augment stage 1 outcome. In: Swales MA, editor. The Oxford Handbook of Dialectical Behaviour Therapy. Oxford University Press, Oxford (2019).

92. Bock MM, Graf T, Woeber V, Kothgassner OD, Buerger A, and Plener PL. Radical acceptance of reality: Putting DBT-A skill groups online during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative study. Front Psychiatry. (2022) 13:617941. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.617941

93. Rathus JH and Miller AL. Dialectical behavior therapy adapted for suicidal adolescents. Suicide Life Threat Behav. (2002) 32:146–57. doi: 10.1521/suli.32.2.146.24399

94. Mayring P. 12th ed. In: Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse: Grundlagen und Techniken. Germany: Beltz (2015).

95. Ramzan N, Dixey R, and Morris A. A qualitative exploration of adolescents’ experiences of digital dialectical behaviour therapy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Cognit Behav Ther. (2022) 15:e48. doi: 10.1017/S1754470X22000460

96. Ratnaweera N, Hunt K, and Camp J. A qualitative evaluation of young people’s, parents’, and carers’ experiences of a national and specialist CAMHS dialectical behaviour therapy outpatient service. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:5927. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18115927

97. Meyer J, Öster C, Ramklint M, and Isaksson J. You are not alone: Adolescents’ experiences of participation in a structured skills training group for ADHD. Scand J Psychol. (2020) 61:671–8. doi: 10.1111/sjop.12655

98. Hesslinger B, Tebartz van Elst L, Nyberg E, Dykierek P, Richter H, Berner M, et al. Psychotherapy of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in adults. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. (2014) 252:177–84. doi: 10.1007/s00406-002-0379-0

99. Hirvikoski T, Waaler E, Alfredsson J, Pihlgren C, Holmström A, Johnson A, et al. Reduced ADHD symptoms in adults with ADHD after structured skills training group: Results from a randomized controlled trial. Behav Res Ther. (2011) 49:175–85. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2011.01.001

100. Krippendorff K. Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. 2nd ed. Sage Publications (2004).

101. Pardo ES, Rivas AF, Barnier PO, Mirabent MB, Lizeaga IK, Cosgaya AD, et al. A qualitative research of adolescents with behavioral problems about their experience in a dialectical behavior therapy skills training group. BMC Psychiatry. (2020) 20:245. doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-02649-2

102. Kitzinger J. Qualitative research: Introducing focus groups. BMJ. (1995) 311:299–302. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7000.299

103. Schnur JB and Montgomery GH. A systematic review of therapeutic alliance, group cohesion, empathy, and goal consensus/collaboration in psychotherapeutic interventions in cancer: Uncommon factors? Clin Psychol Rev. (2010) 30:238–47. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.005

104. Scope A, Booth A, and Sutcliffe P. Women’s perceptions and experiences of group cognitive behaviour therapy and other group interventions for postnatal depression: A qualitative synthesis. J Adv Nurs. (2012) 68:1909–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2012.05954.x

105. Murphy D and Joseph S. Trauma and the therapeutic relationship: Approaches to process and practice. Palgrave Macmillan;. (2013) p:1–11.

106. Feigenbaum JD, Fonagy P, Pilling S, Jones A, Wildgoose A, and Bebbington PE. A real-world study of the effectiveness of DBT in the UK National Health Service. Br J Clin Psychol. (2012) 51:121–41. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.2011.02017.x

107. Panos PT, Jackson JW, Hasan O, and Panos A. Meta-analysis and systematic review assessing the efficacy of dialectical behavior therapy (DBT). Res Soc Work Pract. (2014) 24:213–23. doi: 10.1177/1049731513503047

Keywords: qualitative research, psychological therapy, patient-centred care, literature review, thematic synthesis

Citation: Hall A, Gregg L, O’Ceallaigh B and Wittkowski A (2025) Transdiagnostic patient experiences of dialectical behavioural therapy: a systematic review and metasynthesis. Front. Psychiatry 16:1640341. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2025.1640341

Received: 03 June 2025; Accepted: 08 September 2025;

Published: 06 October 2025.

Edited by:

Jorge Sinval, Nanyang Technological University, SingaporeReviewed by:

Érica Duran, Federal University of Bahia (UFBA), BrazilCopyright © 2025 Hall, Gregg, O’Ceallaigh and Wittkowski. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Anja Wittkowski, YW5qYS53aXR0a293c2tpQG1hbmNoZXN0ZXIuYWMudWs=

Abigail Hall1,2

Abigail Hall1,2 Anja Wittkowski

Anja Wittkowski