Abstract

The energy-efficient extraction of oxygen directly from air remains a significant technological challenge. Anion-exchange membranes (AEMs) play a critical role in electrochemical systems due to their ability to provide high ionic conductivity and chemical stability, achieved through rational design of polymer backbones combined with functional cationic groups. In this study, we combine fuel cell and water electrolyzer electrodes to allow a unique electrochemical device to selectively extract oxygen from air. Specifically, we present a hydrophilic imidazolium group that was introduced as a “performance-assisting moiety” onto a poly (2,6-dimethyl-1,4-phenylene oxide) (PPO) backbone to fabricate novel AEMs. The resulting membranes exhibited controlled water uptake of 21.2%–53.7%, moderate swelling ratios of 3.5%–18.3% below 70 °C, and satisfactory thermal and mechanical stability. Selected AEMs that demonstrated moderate ionic conductivity and ion exchange capacity (IEC) were incorporated into an electrochemical anion exchange membrane oxygen separator (AEMOS). The resultant device can achieve a high current density of 109 mA cm-2, reflecting its strong potential for efficient oxygen separation. This work presents a promising solid‐state and electrolyte‐free strategy for oxygen extraction, which is expected to contribute to the development of sustainable oxygen generation technologies.

Graphical Abstract

1 Introduction

Accounting for 21 vol% of the air, oxygen holds a significant position in the global chemical commodity market and is widely used across nearly all industrial sectors. (Hashim et al., 2010; Burggraaf and Cot, 1996). As a raw material, it has been employed in large-scale clean energy technologies and has experienced consistent market growth in recent decades. (Burggraaf and Cot, 1996; Zhu and Yang, 2019). It is extensively applied in industries such as chemical production, iron and steel metallurgy, glass manufacturing, and environmental protection. (Wegewitz et al., 2023; Hashim et al., 2011). Currently, the primary methods for separating oxygen from air include cryogenic distillation, pressure swing adsorption (PSA), and membrane separation. (Singh et al., 2024). Cryogenic distillation plants require substantial investment, are energy-intensive, and involve complex operations. (Eckl et al., 2025; Adhikari et al., 2021). PSA-derived oxygen is often limited by factors such as molecular sieve performance and air humidity, making it challenging to meet high-purity requirements or achieve large-scale application. (Si et al., 2025; Zhang et al., 2025). Membrane-based separation, on the other hand, depends heavily on the performance and cost of the membrane materials, which directly affect process economics. (Lei et al., 2021). Thus, developing advanced oxygen separation technologies is imperative to satisfy the increasing global demand for high-purity oxygen.

Besides physical air-separation methods, high-purity O2 can also be generated electrochemically through water oxidation in systems such as water electrolysis. (Kempler et al., 2024; Li et al., 2022; Ding et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2022; Langer and Haldeman, 1964; Goldstein and Tseung, 1972; Tseung and Jasem, 1981). The development of electrochemical oxygen production technology has led to increased efforts aimed at designing more efficient and stable oxygen generators, with particular emphasis on material selection and system configuration. (Park et al., 2022; Mardle et al., 2023; Hua et al., 2023). Recently, the electrochemical oxygen generator (EOG) has emerged as a promising alternative, offering high energy efficiency and rapid, stable production of high-purity oxygen through targeted optimizations and sophisticated design. (Arishige et al., 2014; Tian et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2022). These improvements enable EOG to achieve high current density under moderate overvoltage while maintaining excellent long-term operational stability. It is worth noting that these systems typically utilize anion exchange membranes (AEMs) as the core component to effectively separate oxygen from the O2/N2 mixture gas. Here, the selection of an AEM over a proton exchange membrane (PEM) is primarily motivated by the alkaline operating environment. This alkalinity presents a potential pathway for future use of non-precious group metal catalysts, (Zhang et al., 2021; You et al., 2020; Gao et al., 2024), offering a significant advantage over PEM-based systems which typically rely on platinum-group metals. (Zhao et al., 2024; Liu et al., 2023). Despite this advancement, the early designs of EOG still relied on corrosive liquid electrolytes such as KOH or sweep gas, which not only caused equipment corrosion and safety hazards but also limited the current density and oxygen production efficiency of the system. (Tian et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2022). To overcome these limitations, researchers have made numerous innovations in material and system design. A significant advancement in the technology was recently reported by Dekel et al., who developed a solid-state device known as the Anion-Exchange Membrane Oxygen Separator (AEMOS), capable of producing high-purity oxygen at high current densities, without the need for sweeping gases or liquid electrolytes. (Faour et al., 2024). The AEMOS device incorporates a solid polymer electrolyte membrane and stable electrode materials, forming a compact cell comprising an anode, a cathode, and an AEM. In this configuration, O2 from a cathode-side O2/N2 mixture is electrochemically separated, generating high-purity oxygen (>96%) at the anode. Furthermore, this study employs an electrolyte-free configuration, which simplifies the device architecture and operation by avoiding the complications associated with handling liquid electrolytes, such as leakage, evaporation, and concentration changes, thereby enabling researchers to focus on the membrane performance for gas separation and facilitating straightforward scaling, paving the way for industrial-level applications. These advancements represent significant progress toward practical electrochemical oxygen production, offering a promising solution for high-purity oxygen supply in medical, aerospace, and water treatment. However, the AEM used in this previous study is a commercial Aemion™ membrane. (Faour et al., 2024). Thus, further enhancement of the system’s performance, particularly in terms of efficiency and durability, could potentially be achieved through the strategic design and optimization of the AEM material.

AEMs are central to electrochemical devices, mainly including fuel cells, electrolyzers, and metal-air batteries. (Zhang et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2022a; Li et al., 2014; Swain et al., 2025; Yassin and Dekel, 2025; Muhyuddin et al., 2025; Yusibova et al., 2025; Raut et al., 2025). Among these, anion exchange membrane fuel cells (AEMFCs) have garnered considerable interest in recent years due to their compatibility with non-precious metal catalysts and their performance over a wide temperature range, thereby reducing system costs. (Willdorf-Cohen et al., 2023; Haj-Bsoul et al., 2022; Douglin et al., 2021; Xue et al., 2024). As a critical component of AEMFCs, the AEMs must not only facilitate efficient ion conduction but also exhibit robust chemical stability and mechanical strength to ensure long-term operational durability. (Dekel, 2018; Hren et al., 2021; Couture et al., 2011; Yassin et al., 2024). Research efforts have focused on designing novel polymer structures with functionalized cations to enhance AEM performance. (Yin et al., 2024; Zeng et al., 2023). Various polymer backbones-such as poly (phenylene oxide)s, poly (arylene ether sulfone)s, polybenzimidazoles, and poly (olefin)s-have been explored for AEM fabrication. (Liang et al., 2022; Serbanescu et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2021; Xue et al., 2025). Further modifications with functional groups, including quaternary ammonium, tertiary amine, secondary amine, and phenoxide cations, have been pursued to improve ion exchange capacity (IEC) and ionic conductivity. (You et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2023; Aggarwal et al., 2022). For instance, the quaternary ammonium (QA) cation [2-(Methacryloyloxy) ethyl trimethyl ammonium] chloride (MTAC) was selected to be grafted on the polymer backbone of polybenzimidazole (PBI) to increase the ionic conductivity while keeping the outstanding properties of PBI. (Merle et al., 2013). The methacryloyloxy group enabled graft-polymerization with PBI, which provides a robust method for functionalizing the polymer backbone with cation groups to improve AEM performance. Similarly, the influence of the functionalization route of poly (2,6-dimethyl-1,4-phenylene)oxide (PPO) with grafted QA cations on alkaline stability on AEMs was investigated by researchers. (Becerra-Arciniegas et al., 2019). Two synthetic routes, bromination and chloromethylation, were employed to incorporate ammonium groups into PPO. The results demonstrate that AEMs derived from the bromination route present enhanced ionic conductivity, presumably because of the decreased alkaline attack of QA cations. Additionally, imidazolium-based cations, such as 1-allyl-3-methylimidazolium chloride copolymerized with methyl methacrylate or butyl methacrylate, as well as 1-vinyl-3-methylimidazolium iodide and 1-vinyl-3-butylimidazolium bromide copolymerized with styrene, have also been developed as AEMs. (Ouadah et al., 2017; Chat et al., 2022). The five-heterocyclic-ring of imidazolium delocalizes the positive charge, mitigating nucleophilic attack under alkaline conditions via Hofmann or SN2 elimination pathways. (Guo et al., 2010; Fang et al., 2015). These systems exhibit superior chemical and thermal stability compared to conventional alkyl QA-functionalized polymers, highlighting their potential for AEM applications.

In this work, we synthesized functionalized PPO bearing imidazolium cations for the preparation of AEMs, following a synthetic route similar to those reported in the literature. (Wang et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2015; Sheng et al., 2020). The stoichiometry of the reactants was specifically tailored to obtain AEMs with distinct properties compared to prior studies. This study aims to enhance the performance of AEMOS device by optimizing the chemical structure of the AEMs, thereby laying a foundation for tuning their operational characteristics. The synthesized polymer exhibits excellent thermal stability, and the derived AEMs present controlled water uptake of 21.2%–53.7% and moderate swelling ratios of 3.5%–18.3% below 70 °C. This solid polymer membrane serves as the sole electrolyte in an oxygen separation device. The resulting solid-state electrochemical unit operates under a low external potential gradient to extract oxygen from O2/N2 mixtures simulating air, which can achieve a high current density of 109 mA cm-2 at 1.2 V, showing a promising potential for oxygen separation in practical applications. In contrast to the previous study, (Faour et al., 2024), this work emphasizes the significance of membrane chemical structure by synthesizing and evaluating AEMs based on cation-grafted functional polymers. This approach provides an alternative pathway for regulating the performance of the AEMOS device by altering the polymer structure in the future.

2 Experimental

2.1 Materials

PPO powder was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. N-bromosuccinimide (NBS), 2,2′-azo-bis-isobutyronitrile (AIBN), chlorobenzene and 1-methylimidazole were obtained from Shanghai Titan Scientific Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Ethanol, dimethylformamide (DMF), and ethyl acetate were provided by Guangdong Guanghua Sci-Tech Co., Ltd. (Guangdong, China). Chloroform was supplied by Shanghai Maclin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Chloroform-d and dimethyl sulfoxide-d6 were bought from Anhui Zesheng Technology Co., Ltd. (Anhui, China). NaCl and KNO3 powders were purchased from Merck Chemicals.

2.2 Synthesis of functionalized PPO

2.2.1 Synthesis of brominated PPO

Brominated PPO was synthesized by dissolving PPO (6.0 g) in chlorobenzene (40 mL), followed by the addition of NBS (7.2 g) and AIBN (0.3 g). The reaction mixture was conducted at 135 °C for 12 h. The resulting mixture was then precipitated in ethanol, and the crude product was dissolved in chloroform. This solution was subsequently washed with ethanol three times and dried under vacuum at 65 °C to yield brominated PPO (BPPO).

2.2.2 Synthesis of imidazolated PPO

The modification was performed by dissolving 6.0 g of BPPO and 9.0 g of 1-methylimidazole in DMF, followed by stirring the solution at 100 °C for 24 h. The crude product was then purified via repeated washing with ethyl acetate and dried overnight under vacuum at 65 °C, yielding the target product imidazolium-functionalized PPO (imPPO). The overall synthesis procedure is illustrated in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1

The synthetic route of the imPPO.

2.3 Preparation of imPPO-based membranes

The synthesized imPPO (1.5 g) was dissolved in 10 mL DMF and stirred at 60 °C for 6 h to prepare casting solutions. Then a certain volume of resultant casting solutions was poured onto a watch glass after removing air bubbles through ultrasonic treatment, which was put into an oven at 80 °C for 48 h to evaporate the solvents. The obtained membranes were stripped from the watch glass with a thickness of around 60–100 µm. The membrane preparation process is summarized in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2

Illustration of the preparation process of the imPPO-based membranes.

2.4 Characterization and measurements

2.4.1 Material characterization

The synthesized polymers were tested using hydrogen nuclear magnetic resonance (1H NMR), which were dissolved in the deuterated solvent in the instrument (Bruker Ascend 400, 400 MHz, Germany) to analyze the chemical structures of the synthesized products. The successful functionalization of PPO was further confirmed using Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy conducted on a Thermo Scientific spectrometer (Thermo Nicolet In10, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, United States). The composition of resultant AEMs was also analyzed by FTIR. The thermal stability of the synthesized material was assessed by thermogravimetric analyzer (TGA, TGA 55, United States). The measurement was performed under a nitrogen atmosphere by heating the sample from 50 °C to 600 °C at a constant rate of 10 °C min-1. The mechanical tensile properties of fabricated AEMs were detected through a tensile testing machine (Instron 5,966, United States) with a fixed extension rate of 2 mm min-1 under room temperature. The primary membrane investigated in this study had a thickness of approximately 84 µm. To this end, a thinner membrane (approximately 67 µm) was also prepared, and its properties were analyzed for a comparative analysis (see Supplementary Material).

2.4.2 Water uptake and swelling of the membranes

The water uptake (WU) of the prepared membranes was determined by immersing these samples in deionized water at 30, 60, 70, and 80 °C for 48 h to ensure complete hydration. The weights and dimensions of the hydrated samples were then recorded. Subsequently, the samples were dried at 60 °C for 48 h to measure the weight and length of the dry membranes. The WU was calculated using Equation 1:where and are the weights of the hydrated and dry membranes, respectively.

Similarly, the swelling ratios (SR) of the membranes were calculated by Equation 2where and represent the lengths of the full hydrated and dry membranes, respectively. And the WU and SR were measured in the Br− form.

2.4.3 Ion exchange capacity

The IEC of the prepared AEMs was measured via a standard titration method, following existing procedures. (Li et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2022b; Wang et al., 2021). In brief, membrane samples were first cut into approximately 1 × 1.5 cm2 pieces and immersed in a 1 M NaCl aqueous solution for 48 h at ambient temperature to achieve complete ion exchange. Subsequently, the samples were thoroughly rinsed with deionized water over a period of 48 h to eliminate any residual salt. Afterwards, the samples were equilibrated in 1 M KNO3 solution for a subsequent 48-h period. The resulting solution containing the AEM sample was then titrated with 0.01 M AgNO3 aqueous solution utilizing an automated titrator (751 GPD Titrino, Metrohm) to quantify the amount of released chloride ions. Finally, the membrane was carefully washed with deionized water and dried at 50 °C for 24 h. The IEC value, expressed in milliequivalents per gram of dry membrane (meq g-1), was then determined using Equation 3:where refers to the volume of AgNO3 solution titrated, is the concentration of the AgNO3 solution, and represents the dry weight of the membrane sample in the NO3− form.

2.4.4 Ionic conductivity

The in-plane ionic conductivity of the AEM samples in chloride form (Cl−) was evaluated by the four-probe method using a potentiostat (Ivium-n-Stat, Ivium Technologies), following conventional procedures reported elsewhere. (Willdorf-Cohen et al., 2023; Li et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2022b; Wang et al., 2021; Zhegur-Khais et al., 2020). In brief, the membranes were cut into rectangular strips measuring 1 × 3 cm2 and immersed in deionized water at 70 °C. Prior to measurement, all samples were stabilized for no less than 30 min under the specified conditions. The membrane resistance (R) was determined via the cyclic voltammetry method, with the value obtained from the slope of the linear current-voltage (I-V) response. The ionic conductivity () was then determined from the following Equation 4:where corresponds to the inter-electrode distance (4.25 mm), while and refer to the width and thickness of the membrane, respectively.

2.4.5 Anion exchange membrane oxygen separator testing

The prepared imPPO-based AEM was installed in the AEMOS device. Figure 3 presents a schematic diagram of an AEMOS, an electrochemical device designed for oxygen separation and concentration, which comprises an anode and a cathode, separated by an AEM. A mixed O2/N2 stream is fed to the cathode, while O2 is generated and released as the anode. Under an applied potential, hydroxide ions (OH−) generated at the cathodic ORR migrate across the AEM to the anode. On the anode side, the OER occurs, electrooxidizing the OH− ions, producing O2 gas. The corresponding half-cell reactions are given as:

FIGURE 3

Schematic diagram of the anion exchange membrane oxygen separator (AEMOS).

Cathode:

Anode:

This system allows selective oxygen separation from gas mixtures, leveraging the conductive properties of the AEM and the electrocatalytic activity of the electrode materials. Additionally, it should be noted that the feed gas O2/N2 mixture was used to avoid the carbonation of the AEM, which would occur in the presence of CO2, such as in ambient air, due to its reaction with hydroxide ions (OH−) to form carbonate (CO32-) and bicarbonate (HCO3−) species. (Faour et al., 2024; Kubannek et al., 2023; Krewer et al., 2018).

The AEMOS cells were evaluated using an 850E Scribner Associates Fuel Cell test station (United States). Prior to operation, the anode inlet was sealed, and the cell was heated to a certain temperature (60, 70, and 80 °C) with N2 gas continuously supplied to the cathode at a flow rate of 500 mL min-1 until thermal stability was achieved. System pressure was regulated at 0, 50, 100, 150, and 200 kPa (g) to examine its influence on cell behavior. Upon confirmation of adequate sealing, the cathode was supplied with synthetic air (79% N2/21% O2 mixture) humidified to 100% relative humidity at a flow rate of 500 mL min-1. Linear sweep voltammetry was employed to obtain polarization curves by scanning from 0.0 V to 1.2 V at a rate of 10 mV s-1 without iR compensation.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Synthesis of derived PPO

In this work, PPO was selected as the base polymer due to its robust mechanical properties, chemical stability, and good film-forming ability. To impart high ion conductivity, PPO was first brominated to yield bromomethyl-functionalized BPPO, which served as an intermediate for further quaternization with 1-methylimidazole. The resulting imPPO was designed to facilitate the formation of efficient ion-conducting pathways. Structural verification of each synthetic step was conducted using 1H NMR spectroscopy. As illustrated in Figure 4, the spectrum of pristine PPO displays characteristic resonance signals corresponding to its aromatic and methyl protons. Following bromination, the emergence of new peaks attributed to bromomethyl groups (−CH2Br) in BPPO confirms the successful synthesis of the target product. Most notably, the 1H NMR spectrum of imPPO exhibits distinct signals in the region of 7–10 ppm, which are assigned to the aromatic protons of the grafted 1-methylimidazolium cations. These features provide clear evidence for the conversion of BPPO to imPPO and the successful anchoring of the cationic groups onto the polymer backbone.

FIGURE 4

1H NMR characterization of synthesized materials.

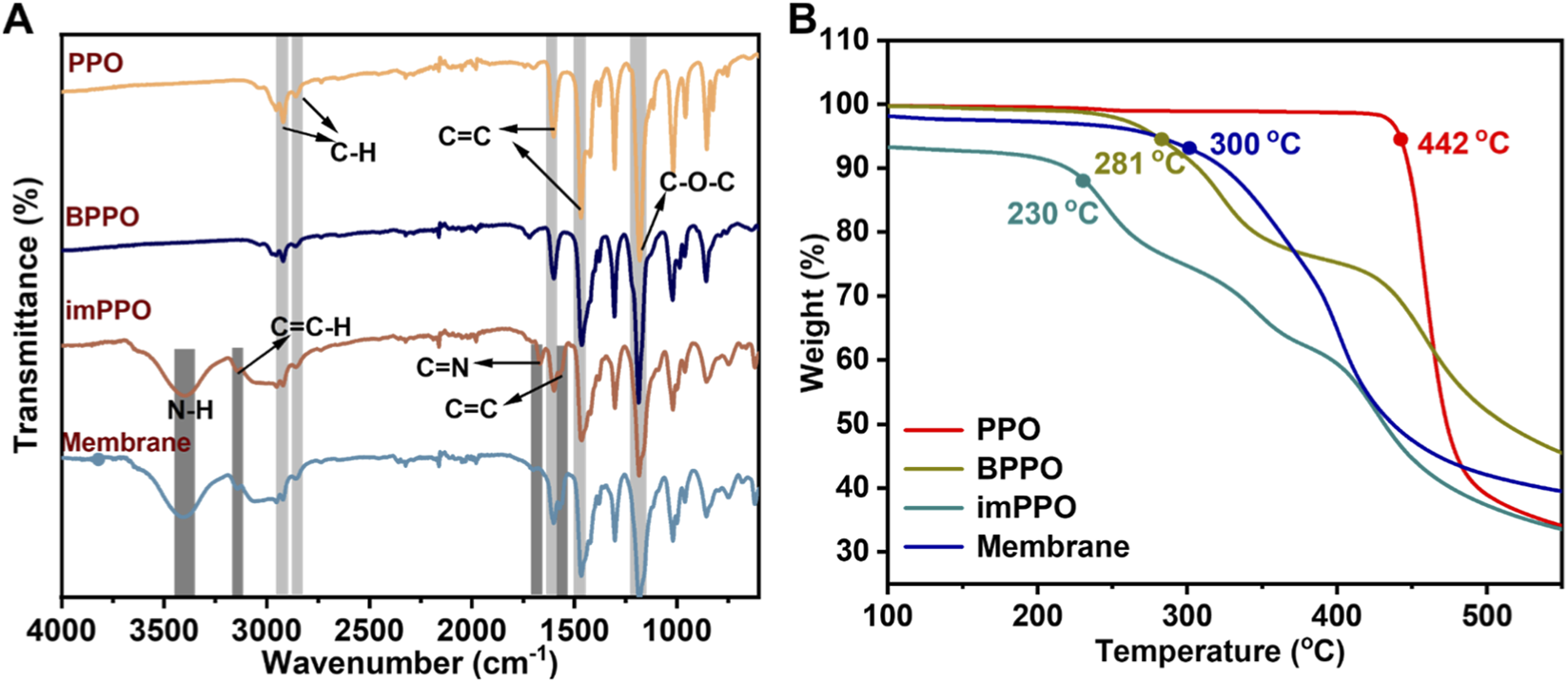

The chemical structures of the synthesized polymers were further analyzed using FTIR spectra (Figure 5A). The FTIR spectra of pristine PPO, exhibited characteristic absorption bands corresponding to its aromatic ether structure. A strong band at approximately 1,180 cm-1 corresponds to the asymmetric stretching vibration of the C-O-C in the polymer main chain. Additional signals at 1,602 and 1,468 cm-1 arise from aromatic C=C ring stretching vibrations, while signals at 2,917 cm-1 and 2,855 cm-1 are ascribed to C-H stretching vibrations of methyl groups. These peaks also existed in FTIR of BPPO and imPPO. In the FTIR spectra of imPPO, new peaks emerged at 1,560 cm-1 and 1,663 cm-1, which are attributed to C=C and C=N stretching vibrations within the imidazolium ring, respectively. Furthermore, absorptions near 3,155 cm-1 and 3,389 cm-1 are ascribed to C=C-H stretching and N-H stretching vibration of the imidazolium ring. These peaks demonstrate that the target product imPPO was successfully synthesized.

FIGURE 5

(A) FTIR spectra of synthesized polymers and prepared membranes. (B) TGA curves of synthesized polymers.

TGA curves were detected to analyze the thermal stability of the synthesized polymers. As demonstrated in Figure 5B, the 5% weight loss temperature of these polymers follows the order: imPPO < BPPO < PPO, indicating that incorporation of functional groups into the side chains reduces the thermal stability of polymers. Despite this trend, imPPO still maintains reasonable thermal stability, which is suitable for high-temperature industrial applications.

3.2 Performance of AEMs

The membranes were successfully fabricated and exhibited good thermal stability, as confirmed by the characteristic FTIR peaks in Figure 5A and the TGA curves in Figure 5B. The performance of the AEMs in practical applications is influenced not only by their thermal stability but also by their water uptake and swelling characteristics. Water uptake is critical in dissociating ion pairs, enabling the subsequent transport of free ions among adjacent conductive sites. Accordingly, higher water uptake is generally associated with improved ion conductivity. (Liang et al., 2022; Liu et al., 2019). As illustrated in Figure 6A, the water uptake of the prepared AEMs enhanced with the temperature increase. The AEMs exhibit moderate water uptake under 60 °C and 70 °C, while a remarkable increase is observed at 80 °C. Although enhanced hydrophilicity can reduce the formation of isolated conductive regions and lessen the restrictive effect of restriction of hydrophobic domains on the ion transport, (Liang et al., 2022), excessive water absorption induces undesirable swelling of the membrane, dilutes the concentration of fixed charge carriers, and accelerates chemical degradation processes, including nucleophilic attacks on cationic head groups and hydrolysis of the polymer backbone, particularly at elevated temperatures. (Sriram et al., 2023; Yang et al., 2022; Li and Baek, 2021). Correspondingly, in Figure 6A, the swelling ratio exhibits a marked increase compared to the values recorded at 30, 60, and 70 °C. Such a pronounced swelling ratio adversely affects ionic conductivity and poses a considerable challenge to the chemical stability and long-term durability of AEMs. Additionally, the water uptake and swelling ratio of thinner membranes with 67 µm were also evaluated. As summarized in Supplementary Table S1, a comparable trend to that of the 84 µm membrane was observed, implying a limited dependence on thickness.

FIGURE 6

(A) Water uptake and swelling ratio of prepared AEMs (error bars represent the standard deviation from four independent membrane samples); (B) Stress-strain curves of AEMs (Membrane thickness: ∼84 µm).

The mechanical tensile performances of the membranes were evaluated. As depicted in Figure 6B and Supplementary Table S1, 84 µm membrane exhibits a higher tensile stress at break than 67 µm membrane, reflecting the effect of membrane thickness. In contrast, the elongation at break increases with thinner membrane thickness. The results demonstrate that increasing membrane thickness can reduce the mechanical strength of these membranes but increase the flexibility of the membranes.

Ion conductivity is a critical parameter for assessing the performance of AEMs. The ion exchange capacity (IEC), which reflects the density of ionic groups in the membranes, also plays a significant role in facilitating anion transport. As summarized in Supplementary Table S1, both the IEC and ionic conductivity were measured for membranes of different thicknesses. While IEC values remained similar across the membranes, M2 demonstrated higher ionic conductivity than M1, suggesting that membrane thickness has a discernible, though modest, influence on conductivity. These results indicate that reduced membrane thickness is conducive to enhanced ion conduction. The lower overall resistance of the thinner membrane is consistent with a shortened ion transport pathway. While this discovery should be considered preliminary due to the limited sample set, and the underlying mechanism may involve factors beyond simple geometric effects.

3.3 Performance of AEMOS

Following a previously reported procedure, (Faour et al., 2024), the AEMOS device was fabricated using the prepared imPPO-based AEMs combined with catalyst materials. Among them, the ORR and OER were conducted using Pt/C and IrO2 as the cathode and anode catalysts, respectively, given their status as standard materials in alkaline media. AEMs with different thicknesses were individually integrated into the AEMOS device. The resulting polarization curves were analyzed to assess the properties of AEMOS, as depicted in Figure 7.

FIGURE 7

(A) Polarization curves of AEMOS cells at different cell temperatures in the conditions of 500 mL min-1 synthetic cathode air flow, 100% RH, and a pressure of 200 kPa (g). (B) Polarization curves of AEMOS cells under a synthetic air cathode flow of 500 mL min-1, 100% RH, and a temperature of 60 °C (Thickness: ∼84 µm).

Figure 7A displays the polarization curves of AEMOS cells measured under a synthetic air cathode flow of 500 mL min-1, 100% relative humidity (RH), and a pressure of 200 kPa (g). The results reveal that the cell performance is influenced by operating temperature. As illustrated in Figure 7A, the current density reached 58 mA cm-2 when the temperature was elevated from 60 °C to 70 °C. However, a further increase to 80 °C led to a decline in current density. This performance decay is likely attributed to the chemical degradation of the PPO-based membrane, which is known to be vulnerable under harsh alkaline and high-temperature conditions. (Chen et al., 2022a; Liang et al., 2022; Nuñez and Hickner, 2013; Mohanty et al., 2016; Lin et al., 2013). This observation is consistent with the higher water uptake and swelling ratio observed at 80 °C (Figure 6A), which may accelerate membrane degradation and result in unstable polarization behavior. In contrast, the polarization curves in Supplementary Figure S1A, obtained with a thinner membrane (∼67 µm), display greater instability at 70 °C and 80 °C, though a higher current density of 103 mA cm-2 was achieved at 60 °C. This suggests that thinner AEMs facilitate higher current densities, indicating an enhanced oxygen generation capacity of the AEMOS cell, which provides an alternative solution for further improving the performance of AEMOS in the future. However, the inferior mechanical strength of thinner membranes (as evidenced in Figure 6B; Supplementary Table S1) likely contributes to the observed performance instability at higher temperatures (Figure 7B).

The effect of operating pressure on cell performance was also investigated under a synthetic air cathode flow of 500 mL min-1, 100% RH, and a temperature of 60 °C. As shown in Figure 7B, the current density at 1.2 V increases with rising pressure, indicating that higher pressure at the cathode promotes oxygen generation capacity at the anode. This is attributed to enhanced ORR achieved at higher pressures. (Faour et al., 2024). Although a similar trend is observed for the thinner membrane in Supplementary Figure S1B, the current density at 200 kPa (g) is lower than that at 150 kPa (g). This deviation may be attributed to the limited mechanical robustness of the thinner membrane, which could be compromised under higher pressures. Nonetheless, the overall current density values in Supplementary Figure S1B are higher than those in Figure 7B, which can be primarily ascribed to its reduced ionic resistance when using a thinner membrane, a phenomenon consistent with observations in AEM-based fuel cells. (Faour et al., 2024; Yassin et al., 2022).

Overall, the synthesized membrane operated in the AEMOS cell in this work achieved a current density of up to 109 mA cm-2 at 1.2 V, demonstrating its promising potential for further optimization and scale-up. As summarized in Supplementary Table S2, the current density obtained at 0.7 V surpasses those reported in the literature, (Arishige et al., 2014; Tian et al., 2022), although it remains lower than the values documented in references. (Zhang et al., 2022; Faour et al., 2024). Notably, the superior performance was obtained using a corrosive liquid KOH electrolyte, (Zhang et al., 2022), which, although it increases membrane conductivity, raises concerns regarding long-term safety and practicality. Although previous work done on AEMOS (Faour et al., 2024) exhibits superior current density compared to our cells in imPPO-based AEM, this comparison emphasizes the substantial opportunity for further refinement of the membrane structure developed in this study.

4 Conclusion

The imidazolium-functionalized PPO was successfully synthesized and fabricated into AEMs. The incorporation of imidazolium cations as functional groups effectively enhances membrane performance, demonstrating its role as a beneficial “performance-assisting moiety” for developing high-performance AEMs. The resulting membranes exhibit excellent thermal stability and dimensional integrity at temperatures up to 60 °C. These membranes were further integrated into an all-solid-state electrochemical AEMOS, which operates without the need for liquid electrolytes or sweep gases. The device achieved a high current density of 109 mA cm-2, indicating its strong potential for efficient oxygen separation and generation. Future studies will focus on optimizing the chemical structure of the membranes to improve their ionic conductivity and mechanical robustness under more demanding operating conditions. In parallel, a comprehensive post-mortem analysis of the membrane, employing techniques such as NMR and FTIR to compare pristine and operated samples, is essential to confirm the chemical degradation and elucidate the underlying mechanisms, which will guide the development of more robust next-generation membranes. The membrane-based oxygen separation strategy presented in this work offers a promising, energy-efficient alternative to conventional methods and represents a meaningful step forward in the development of solid-state oxygen separation and generation technologies.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Author contributions

MZ: Formal Analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft. AS: Investigation, Writing – original draft. JZ: Writing – original draft. XH: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review and editing. DD: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The authors declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The authors would like to acknowledge the major project (JSGG20220831105403006) from Shenzhen Science and Technology Innovation Commission for supporting this work. This work was also partially funded by the GTIIT Guandong Technion Seed Grants, grant No. 2071822; by the Guangdong Major Project of Basic and Applied Basic Research (Future functional materials under extreme conditions), grant NO. 2021B0301030005; by the Nancy and Stephen Grand Technion Energy Program (GTEP), grant No. 2072181; by the European Union’s Horizon 2021 research and innovation program under grant agreement 101071111, and by the European Union’s Horizon 2024 research and innovation program under grant agreement 101192454. The research was conducted with the support of the Israel National Institute for Energy Storage (INIES), funded by the council for higher education, grant No. 2072133.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frmst.2025.1732112/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Adhikari B. Orme C. J. Klaehn J. R. Stewart F. F. (2021). Technoeconomic analysis of oxygen-nitrogen separation for oxygen enrichment using membranes. Sep. Purif. Technol.268, 118703. 10.1016/j.seppur.2021.118703

2

Aggarwal K. Gjineci N. Kaushansky A. Bsoul S. Douglin J. C. Li S. et al (2022). Isoindolinium groups as stable anion conductors for anion-exchange membrane fuel cells and electrolyzers. ACS Mater. Au2 (3), 367–373. 10.1021/acsmaterialsau.2c00002

3

Arishige Y. Kubo D. Tadanaga K. Hayashi A. Tatsumisago M. (2014). Electrochemical oxygen separation using hydroxide ion conductive layered double hydroxides. Solid State Ionics262, 238–240. 10.1016/j.ssi.2013.09.009

4

Becerra-Arciniegas R.-A. Narducci R. Ercolani G. Antonaroli S. Sgreccia E. Pasquini L. et al (2019). Alkaline stability of model anion exchange membranes based on poly (phenylene oxide)(PPO) with grafted quaternary ammonium groups: influence of the functionalization route. Polymer185, 121931. 10.1016/j.polymer.2019.121931

5

Burggraaf A. J. Cot L. (1996). Fundamentals of inorganic membrane science and technology. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier.

6

Chatenet M. Pollet B. G. Dekel D. R. Dionigi F. Deseure J. Millet P. et al (2022). Water electrolysis: from textbook knowledge to the latest scientific strategies and industrial developments. Chem. Soc. Rev.51, 4583–4762. 10.1039/d0cs01079k

7

Chen H. Tao R. Bang K. T. Shao M. Kim Y. (2022a). Anion exchange membranes for fuel cells: state‐of‐the‐art and perspectives. Adv. Energy Mater.12 (28), 2200934. 10.1002/aenm.202200934

8

Chen Q. Luo J. Liao J. Zhu C. Li J. Xu J. et al (2022b). Tuning the length of aliphatic chain segments in aromatic poly (arylene ether sulfone) to tailor the micro-structure of anion-exchange membrane for improved proton blocking performance. J. Membr. Sci.641, 119860. 10.1016/j.memsci.2021.119860

9

Couture G. Alaaeddine A. Boschet F. Ameduri B. (2011). Polymeric materials as anion-exchange membranes for alkaline fuel cells. Prog. Polym. Sci.36 (11), 1521–1557. 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2011.04.004

10

Dekel D. R. (2018). Review of cell performance in anion exchange membrane fuel cells. J. Power Sources375, 158–169. 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2017.07.117

11

Ding H. Liu H. Chu W. Wu C. Xie Y. (2021). Structural transformation of heterogeneous materials for electrocatalytic oxygen evolution reaction. Chem. Rev.121 (21), 13174–13212. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00234

12

Douglin J. C. Singh R. K. Haj-Bsoul S. Li S. Biemolt J. Yan N. et al (2021). A high-temperature anion-exchange membrane fuel cell with a critical raw material-free cathode. Chem. Eng. J. Adv.8, 100153. 10.1016/j.ceja.2021.100153

13

Eckl F. Moita A. Castro R. Neto R. C. (2025). Valorization of the by-product oxygen from green hydrogen production: a review. Appl. Energy378, 124817. 10.1016/j.apenergy.2024.124817

14

Fang J. Lyu M. Wang X. Wu Y. Zhao J. (2015). Synthesis and performance of novel anion exchange membranes based on imidazolium ionic liquids for alkaline fuel cell applications. J. Power Sources284, 517–523. 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2015.03.065

15

Faour M. Yassin K. Dekel D. R. (2024). Anion-exchange membrane oxygen separator. ACS Org. and Inorg. Au4 (5), 498–503. 10.1021/acsorginorgau.4c00052

16

Gao W. Gao X. Zhang Q. Zhu A. Liu Q. (2024). Durable poly (binaphthyl-co-p-terphenyl piperidinium)-based anion exchange membranes with dual side chains. J. Energy Chem.89, 324–335. 10.1016/j.jechem.2023.11.008

17

Goldstein J. Tseung A. (1972). Kinetics of oxygen reduction on graphite/cobalt-iron oxide electrodes with coupled heterogeneous chemical decomposition of hydrogen peroxide. J. Phys. Chem.76 (24), 3646–3656. 10.1021/j100668a025

18

Guo M. Fang J. Xu H. Li W. Lu X. Lan C. et al (2010). Synthesis and characterization of novel anion exchange membranes based on imidazolium-type ionic liquid for alkaline fuel cells. J. Membrane Science362 (1-2), 97–104. 10.1016/j.memsci.2010.06.026

19

Haj-Bsoul S. Varcoe J. R. Dekel D. R. (2022). Measuring the alkaline stability of anion-exchange membranes. J. Electroanal. Chem.908, 116112. 10.1016/j.jelechem.2022.116112

20

Hashim S. M. Mohamed A. R. Bhatia S. (2010). Current status of ceramic-based membranes for oxygen separation from air. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci.160 (1), 88–100. 10.1016/j.cis.2010.07.007

21

Hashim S. Mohamed A. Bhatia S. (2011). Oxygen separation from air using ceramic-based membrane technology for sustainable fuel production and power generation. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev.15 (2), 1284–1293. 10.1016/j.rser.2010.10.002

22

Hren M. Božič M. Fakin D. Kleinschek K. S. Gorgieva S. (2021). Alkaline membrane fuel cells: anion exchange membranes and fuels. Sustain. Energy and Fuels5 (3), 604–637. 10.1039/d0se01373k

23

Hua D. Huang J. Fabbri E. Rafique M. Song B. (2023). Development of anion exchange membrane water electrolysis and the associated challenges: a review. ChemElectroChem10 (1), e202200999. 10.1002/celc.202200999

24

Kempler P. A. Coridan R. H. Luo L. (2024). Gas evolution in water electrolysis. Chem. Rev.124 (19), 10964–11007. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.4c00211

25

Krewer U. Weinzierl C. Ziv N. Dekel D. R. (2018). Impact of carbonation processes in anion exchange membrane fuel cells. Electrochimica Acta263, 433–446. 10.1016/j.electacta.2017.12.093

26

Kubannek F. Zhegur-Khais A. Li S. Dekel D. R. Krewer U. (2023). Model-based insights into the decarbonation dynamics of anion-exchange membranes. Chem. Eng. J.459, 141534. 10.1016/j.cej.2023.141534

27

Langer S. H. Haldeman R. G. (1964). Electrolytic separation and purification of oxygen from a gas mixture. J. Phys. Chem.68 (4), 962–963. 10.1021/j100786a508

28

Lei L. Lindbråthen A. Hillestad M. He X. (2021). Carbon molecular sieve membranes for hydrogen purification from a steam methane reforming process. J. Membr. Sci.627, 119241. 10.1016/j.memsci.2021.119241

29

Li C. Baek J.-B. (2021). The promise of hydrogen production from alkaline anion exchange membrane electrolyzers. Nano Energy87, 106162. 10.1016/j.nanoen.2021.106162

30

Li Q. Cao R. Cho J. Wu G. (2014). Nanocarbon electrocatalysts for oxygen reduction in alkaline media for advanced energy conversion and storage. Adv. Energy Mater.4 (6), 1301415. 10.1002/aenm.201301415

31

Li L. Wang J.-a. Ma L. Bai L. Zhang A. Qaisrani N. A. et al (2021). Dual-side-chain-grafted poly (phenylene oxide) anion exchange membranes for fuel-cell and electrodialysis applications. ACS Sustain. Chem. and Eng.9 (25), 8611–8622. 10.1021/acssuschemeng.1c02189

32

Li W. Tian H. Ma L. Wang Y. Liu X. Gao X. (2022). Low-temperature water electrolysis: fundamentals, progress, and new strategies. Mater. Adv.3 (14), 5598–5644. 10.1039/d2ma00185c

33

Liang M. Peng J. Cao K. Shan C. Liu Z. Wang P. et al (2022). Multiply quaternized poly (phenylene oxide) s bearing β-cyclodextrin pendants as “assisting moiety” for high-performance anion exchange membranes. J. Membr. Sci.660, 120881. 10.1016/j.memsci.2022.120881

34

Lin B. Dong H. Li Y. Si Z. Gu F. Yan F. (2013). Alkaline stable C2-substituted imidazolium-based anion-exchange membranes. Chem. Mater.25 (9), 1858–1867. 10.1021/cm400468u

35

Liu J. Yan X. Gao L. Hu L. Wu X. Dai Y. et al (2019). Long-branched and densely functionalized anion exchange membranes for fuel cells. J. Membr. Sci.581, 82–92. 10.1016/j.memsci.2019.03.046

36

Liu X. Xie N. Xue J. Li M. Zheng C. Zhang J. et al (2022). Magnetic-field-oriented mixed-valence-stabilized ferrocenium anion-exchange membranes for fuel cells. Nat. Energy7 (4), 329–339. 10.1038/s41560-022-00978-y

37

Liu R.-T. Xu Z.-L. Li F.-M. Chen F.-Y. Yu J.-Y. Yan Y. et al (2023). Recent advances in proton exchange membrane water electrolysis. Chem. Soc. Rev.52 (16), 5652–5683. 10.1039/D2CS00681B

38

Mardle P. Chen B. Holdcroft S. (2023). Opportunities of ionomer development for anion-exchange membrane water electrolysis: focus review. ACS Energy Lett.8 (8), 3330–3342. 10.1021/acsenergylett.3c01040

39

Merle G. Chairuna A. Ven E. V. d. Nijmeijer K. (2013). An easy method for the preparation of anion exchange membranes: graft‐polymerization of ionic liquids in porous supports. J. Applied Polymer Science129 (3), 1143–1150. 10.1002/app.38799

40

Mohanty A. D. Tignor S. E. Krause J. A. Choe Y.-K. Bae C. (2016). Systematic alkaline stability study of polymer backbones for anion exchange membrane applications. Macromolecules49 (9), 3361–3372. 10.1021/acs.macromol.5b02550

41

Muhyuddin M. Santoro C. Osmieri L. Ficca V. C. A. Friedman A. Yassin K. et al (2025). Anion-exchange-membrane electrolysis with alkali-free water feed. Chem. Rev.125 (15), 6906–6976. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.4c00466

42

Nuñez S. A. Hickner M. A. (2013). Quantitative 1H NMR analysis of chemical stabilities in anion-exchange membranes. Acs Macro Lett.2 (1), 49–52. 10.1021/mz300486h

43

Ouadah A. Xu H. Luo T. Gao S. Wang X. Fang Z. et al (2017). A series of poly (butylimidazolium) ionic liquid functionalized copolymers for anion exchange membranes. J. Power Sources371, 77–85. 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2017.10.038

44

Park E. J. Arges C. G. Xu H. Kim Y. S. (2022). Membrane strategies for water electrolysis. ACS Energy Lett.7 (10), 3447–3457. 10.1021/acsenergylett.2c01609

45

Raut A. Fang H. Lin Y.-C. Fu S. Rahman M. F. Sprouster D. et al (2025). The impact of graphene-based materials on anion-exchange membrane fuel cells. Carbon Trends19, 100451. 10.1016/j.cartre.2025.100451

46

Serbanescu O. Voicu S. Thakur V. (2020). Polysulfone functionalized membranes: properties and challenges. Mater. Today Chemistry17, 100302. 10.1016/j.mtchem.2020.100302

47

Sheng W. Zhou X. Wu L. Shen Y. Huang Y. Liu L. et al (2020). Quaternized poly (2, 6-dimethyl-1, 4-phenylene oxide) anion exchange membranes with pendant sterically-protected imidazoliums for alkaline fuel cells. J. Membr. Sci.601, 117881. 10.1016/j.memsci.2020.117881

48

Si H. Hong Q. Chen X. Jiang L. (2025). Pressure swing adsorption for oxygen production: adsorbents, reactors, processes and perspective. Chem. Eng. J.509, 161273. 10.1016/j.cej.2025.161273

49

Singh R. Prasad B. Ahn Y.-H. (2024). Recent developments in gas separation membranes enhancing the performance of oxygen and nitrogen separation: a comprehensive review. Gas Sci. Eng.123, 205256. 10.1016/j.jgsce.2024.205256

50

Sriram G. Dhanabalan K. Ajeya K. V. Aruchamy K. Ching Y. C. Oh T. H. et al (2023). Recent progress in anion exchange membranes (AEMs) in water electrolysis: synthesis, physio-chemical analysis, properties, and applications. J. Mater. Chem. A11 (39), 20886–21008. 10.1039/d3ta04298g

51

Swain S. S. Swain A. K. Jena B. K. (2025). Anion exchange polymer membrane (AEPM)-based separators: an unexplored frontier for ZAB and AAB systems. J. Mater. Chem. A Mater. Energy Sustain.13 (9), 6274–6313. 10.1039/d4ta07636b

52

Tian B. Y. Deng Z. F. Xu G. Z. Song X. Y. Zhang G. Q. Deng J. Y. (2022). Oxygen electrochemical production from air by high performance anion exchange membrane electrode assemble devices. Key Eng. Mater.920, 166–171. 10.4028/p-o3mj79

53

Tseung A. Jasem S. (1981). An integrated electrochemical-chemical method for the extraction of O2 from air. J. Appl. Electrochem.11 (2), 209–215. 10.1007/bf00610983

54

Wang J. Wei H. Yang S. Fang H. Xu P. Ding Y. (2015). Constructing pendent imidazolium-based poly (phenylene oxide) s for anion exchange membranes using a click reaction. RSC Adv.5 (113), 93415–93422. 10.1039/c5ra17748k

55

Wang Z. Parrondo J. Ramani V. (2016). Alkaline stability of poly (phenylene oxide) based anion exchange membranes containing imidazolium cations. J. Electrochem. Soc.163 (8), F824–F831. 10.1149/2.0551608jes

56

Wang K. Zhang Z. Li S. Zhang H. Yue N. Pang J. et al (2021). Side-chain-type anion exchange membranes based on poly (arylene ether sulfone) s containing high-density quaternary ammonium groups. ACS Appl. Mater. and Interfaces13 (20), 23547–23557. 10.1021/acsami.1c00889

57

Wang J. J. Gao W. T. Choo Y. S. L. Cai Z. H. Zhang Q. G. Zhu A. M. et al (2023). Highly conductive branched poly(aryl piperidinium) anion exchange membranes with robust chemical stability. J. Colloid Interface Science629 (Pt A), 377–387. 10.1016/j.jcis.2022.08.183

58

Wegewitz L. Maus-Friedrichs W. Gustus R. Maier H. J. Herbst S. (2023). Oxygen‐free production—from vision to application. Adv. Engineering Materials25 (12), 2201819. 10.1002/adem.202201819

59

Willdorf-Cohen S. Zhegur-Khais A. Ponce-Gonzalez J. Bsoul-Haj S. Varcoe J. R. Diesendruck C. E. et al (2023). Alkaline stability of anion-exchange membranes. ACS Applied Energy Materials6 (2), 1085–1092. 10.1021/acsaem.2c03689

60

Xu F. Qiu K. Lin B. Ren Y. Li J. Ding J. et al (2021). Enhanced performance of poly (olefin)-based anion exchange membranes cross-linked by triallylmethyl ammonium iodine and divinylbenzene. J. Membr. Sci.637, 119629. 10.1016/j.memsci.2021.119629

61

Xue J. Douglin J. C. Yassin K. Huang T. Jiang H. Zhang J. et al (2024). High-temperature anion-exchange membrane fuel cells with balanced water management and enhanced stability. Joule8 (5), 1457–1477. 10.1016/j.joule.2024.02.011

62

Xue J. Douglin J. C. Huang T. Jiang H. Zhang J. Yin Y. et al (2025). Chain entanglement and free-volume effects in branched poly(arylene piperidinium) anion-exchange membranes: random-branched versus end-branched. J. Membr. Sci.717, 123519. 10.1016/j.memsci.2024.123519

63

Yang Y. Li P. Zheng X. Sun W. Dou S. X. Ma T. et al (2022). Anion-exchange membrane water electrolyzers and fuel cells. Chem. Society Reviews51 (23), 9620–9693. 10.1039/d2cs00038e

64

Yassin K. Dekel D. R. (2025). Grand challenges in anion exchange membrane energy applications. Front. Membr. Sci. Technol.4, 1691096. 10.3389/frmst.2025.1691096

65

Yassin K. Douglin J. C. Rasin I. G. Santori P. G. Eriksson B. Bibent N. et al (2022). The effect of membrane thickness on AEMFC performance: an integrated theoretical and experimental study. Energy Convers. Manag.270, 116203. 10.1016/j.enconman.2022.116203

66

Yassin K. Rasin I. G. Brandon S. Dekel D. R. (2024). How can we design anion-exchange membranes to achieve longer fuel cell lifetime?J. Membr. Sci.690, 122164. 10.1016/j.memsci.2023.122164

67

Yin L. Ren R. He L. Zheng W. Guo Y. Wang L. et al (2024). Stable anion exchange membrane bearing quinuclidinium for high‐performance water electrolysis. Angew. Chem.136 (19), e202400764. 10.1002/anie.202400764

68

You W. Noonan K. J. Coates G. W. (2020). Alkaline-stable anion exchange membranes: a review of synthetic approaches. Prog. Polym. Sci.100, 101177. 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2019.101177

69

Yusibova G. Douglin J. C. Vetik I. Pozdnjakova J. Ping K. Aruväli J. et al (2025). Pyrolytic transformation of Zn-TAL metal–organic framework into hollow zn–n–c spheres for improved oxygen reduction reaction catalysis. ACS Omega10 (15), 15280–15291. 10.1021/acsomega.4c11318

70

Zeng M. He X. Wen J. Zhang G. Zhang H. Feng H. et al (2023). N‐Methylquinuclidinium‐based anion exchange membrane with ultrahigh alkaline stability. Adv. Mater.35 (51), 2306675. 10.1002/adma.202306675

71

Zhang J. Zhu W. Huang T. Zheng C. Pei Y. Shen G. et al (2021). Recent insights on catalyst layers for anion exchange membrane fuel cells. Adv. Sci.8 (15), 2100284. 10.1002/advs.202100284

72

Zhang Y. Xie K. Zhou F. Wang F. Xu Q. Hu J. et al (2022). Electrochemical oxygen generator with 99.9% oxygen purity and high energy efficiency. Adv. Energy Mater.12 (29), 2201027. 10.1002/aenm.202201027

73

Zhang Q. Wang S. Li S. Liu Y. Yang X. Li Z. et al (2025). PSA oxygen generation: process parameter optimization and improved oxygen production performance in plateau regions. Sep. Purif. Technol.374, 133620. 10.1016/j.seppur.2025.133620

74

Zhao X. Zhao J. Li D. Zhou F. Li P. Tan Y. et al (2024). Electrolyte-free electrochemical oxygen generator for providing sterile and medical-grade oxygen in household applications. Device2 (9), 100360. 10.1016/j.device.2024.100360

75

Zhegur-Khais A. Kubannek F. Krewer U. Dekel D. R. (2020). Measuring the true hydroxide conductivity of anion exchange membranes. J. Membr. Sci.612, 118461. 10.1016/j.memsci.2020.118461

76

Zhu X. Yang W. (2019). Microstructural and interfacial designs of oxygen‐permeable membranes for oxygen separation and reaction–separation coupling. Adv. Mater.31 (50), 1902547. 10.1002/adma.201902547

Summary

Keywords

anion exchange membrane, oxygen separation, ionic conductivity, ion exchange capacity, current density, cell performance

Citation

Zhang M, Suslonova A, Zhong J, He X and Dekel DR (2025) Solid-state oxygen separation from air using imidazolium-functionalized anion exchange membranes. Front. Membr. Sci. Technol. 4:1732112. doi: 10.3389/frmst.2025.1732112

Received

25 October 2025

Revised

22 November 2025

Accepted

26 November 2025

Published

12 December 2025

Volume

4 - 2025

Edited by

Bharat Shrimant, Dioxide Materials, United States

Reviewed by

Peter Mardle, National Research Council Canada (NRC), Canada

Tanmay Kulkarni, Solidec, United States

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Zhang, Suslonova, Zhong, He and Dekel.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xuezhong He, xuezhong.he@technion.ac.il; Dario R. Dekel, dario@technion.ac.il

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.