- 1Melbourne Sustainable Society Institute, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

- 2Just Space, London, United Kingdom

- 3Bartlett School of Planning, University College London, London, United Kingdom

- 4Beyond Just Now, London, United Kingdom

This community case study describes the process of developing a strategy for community-university engagement, as an example of co-production, and presents the strategy and early outcomes of the work. Based in London, the strategy and the process of co-production are of international relevance in supporting more productive relationships between universities and their cities, as a foundation for repurposing universities for sustainable human progress. The case study is presented in the context of literature related to community engagement with universities and co-production, an area of growing concern as universities seek to strengthen relationships and contribution to sustainable human progress in their home cities. London is one of the world's great university cities, with more than 40 higher education institutions contributing ground-breaking research and educating students from across the globe. London is also home to vibrant local communities, with a strong tradition of grassroots action, community organization and citizen participation. Community groups and universities have a strong history of working together, often without formal recognition or resources. The Community university Knowledge Strategy for London, known as Collaborate!, was a collaboration between universities and grassroots community groups in London, co-convened by Just Space and University College London (UCL). A series of workshops, guided by two steering committees of community and university members, explored principles for working together, cultural and institutional barriers, decolonization, industrial strategies, community spaces and case studies of good practice. The final conference outlined the basis for a London-wide strategy to enable better engagement between universities and grassroots community groups. The strategy addresses core principles, curriculum, evaluation and evidence, resources, relationship building, governance and structures to support collaboration. Co-production ensured high levels of trust between participants and commitment to the outcomes. Implementation of the strategy actions requires ongoing resources to support intermediary structures to overcome misalignment between universities as large, hierarchical institutions and community groups as dynamic, informal, social organizations.

Introduction

Grassroots community groups are vital elements of social and political responses to sustainability and climate crises (Smith et al., 2017; Tokar and Gilbertson, 2020). Universities, as places of learning and research, also contribute to understanding the nature of the problems of unsustainability, options for solving them and the grounds for good judgement (Maxwell, 2014). In a complex techno-scientific society, where knowledge claims are central to political discourse, universities should be open and accessible to all sectors in good faith. Existing university structures, management and drivers encourage engagement with large institutions and participation in the market, but mitigate against sustained, meaningful collaboration with grassroots communities and movements outside formal modern institutions (Conn, 2011). Universities have struggled to engage with small and micro community groups who constitute 81% of voluntary organizations in the United Kingdom (UK) (NCVO, 2020). Given that much of the energy and action in relation to the climate and extinction emergencies, and social movements such as Black Lives Matter and #MeToo, is to be found in informal, grassroots groups, it is important that universities improve their capacity to build critical, collaborative partnerships beyond large institutional and commercial actors and interests. Repurposing universities to support sustainable human progress requires the development of new structures and processes to enable engagement with a wide range of stakeholders, including grassroots groups and informal, dynamic social movements.

Universities' ability to engage grassroots groups is constrained by their own hierarchical structures and funding and policy models that encourage partnerships based on economic and political strength. Engaging with industry, policy and large third-sector organizations with similarly formalized management structures and systems, whilst non-trivial, is relatively straightforward for universities compared to working with grassroots groups that operate in more fluid, dynamic, non-hierarchical, poorly-resourced contexts (Conn, 2011). For individual university staff, increasing workloads undermine their capacity and motivation to engage with grassroots groups, as such work is often unrecognized by university reward structures and incompatible with management processes.

The Community University Knowledge Strategy for London, or Collaborate!, project, aimed to improve partnerships between universities and grassroots community groups. A collaboration between university and community members, the project co-created strategies, structures, and actions at the city scale, beyond the interests of individual universities or community groups. The project's primary purpose to improve London-wide community-university engagement addressed a need identified by Just Space, a network of grassroots community groups who have more than 13 years' experience working with universities in London in teaching, research, and public engagement. The project engaged more than 100 people in participatory events which contributed to the development of a strategic action document, a draft Charter for Community University Partnerships, a case study report, and a short film (Just Space, 2019; Magar, 2020). This community case study reviews literature related to university-community partnerships and co-production, describes the local policy and institutional context for Collaborate!, presents the process and outputs, and reflects on its wider relevance.

Context

The roles of universities have been shaped by their relationship with their stakeholders: from specialist and sheltered enclaves in the medieval ages, they moved to serve emerging nation states, before developing into national and regional institutions serving the growing professions of the industrial society (Watson et al., 2011). Since the 1980s, increasing privatization and marketisation have challenged the role of the university as a potential institution to address social inequality and injustice, and facilitate the circulation of knowledge (Choudry and Vally, 2020). Throughout, the university has performed a distinct and important civic function (Goddard and Vallance, 2014). How this has been shaped or will be shaped by local communities to address current sustainability challenges, is being questioned, both from the perspective of the university as site for community and civic engagement (Watson, 2007; Watson et al., 2011), and considering broader questions of social justice and social responsibility (Choudry and Vally, 2020).

These concerns are of international relevance to higher education institutions who see themselves as having a role in the finding of solutions to tackling some of the worlds' most serious problems including climate change, poverty, public health and environmental quality. In a UNESCO report from 2009 Trends in Global Higher Education: Tracking an Academic Revolution the key drivers affecting universities included the “massification of tertiary systems everywhere, the ‘public good' vs. ‘private good' debate, the impacts of information communication technology, and the rise of the knowledge economy and globalization” (Watson et al., 2011, p. 24).

Policy

Universities in the United Kingdom (UK) are increasingly encouraged to widen their engagement with external partners and to generate meaningful social and economic impact from their research and teaching. This is evident in several agendas being promoted across the sector, including public engagement (NCPE, 2020), the civic university (Civic University Network, 2020), and government funding mechanisms through the Research, Teaching and Knowledge Exchange Excellence Frameworks. Programs have emerged to address specific disciplines and communities, such as the Common Cause Project focused on partnerships between university researchers and Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) communities in the arts and humanities (Common Cause, 2017). These initiatives and policies create a nested hierarchy of drivers for stronger community and public engagement.1

At the level of the institution, drivers for engaging with the public in general include:

• Generation of better quality and more successful research grant applications;

• Expection of research funders;

• Demonstrating the impact of research, which is assessed in the Research Excellence Framework (REF);

• Expections of the national Vitae Researcher Development Framework2 to improve researcher skills in engagement, influence and research impact.

There next set of drivers, operating at the level of disciplines or departments, include:

• Research and teaching that has had some element of public and community engagement is more likely to be transparent and relevant to society;

• Helping researchers to explore new perspectives and new research angles;

• Public and community engagement experience is increasingly being used as a promotion criteria;

• Moral reasons, like accountability for funding or addressing a social justice agenda through research and teaching.

Finally, there are drivers at the individual staff or student level, some of which will be personal drivers, inspirations, ambitions or values, which may be reflected in the pursuit of public engagement and community partnerships:

• Development of new skills;

• Fun and enjoyable work;

• Opportunities to discover new angles on research or practice.

Community-University Engagement

Previous research on university-community partnerships has focused on the experiences of individual colleges or universities in relation to their civic engagement and social responsibility activities (Watson et al., 2011; Goddard and Vallance, 2014). Collaborate! aimed to develop a city-wide strategy, beyond the level of individual institutions.

A useful framing for how to conceptualize organizational and structural relationships between universities and communities was the theoretical work of one of the project's community steering group members Eileen Conn, who has written about the structural incompatibilities of community engagement (Conn, 2011). Conn (2011) describes a social eco-systemic dance which goes on between two structurally different systems, within which university and community groups operate. At an institutional level, universities operate in a hierarchical system as an incorporated organization, with vertical management systems, contractual employment relations, and resourcing based on recurring annual incomes. Community organizations operate within a horizontal peer-based system, where organizations are often unincorporated, management is based on peer relationships and personal links, employment is voluntary, precarious and informal, and resources are based on unpaid labor, donations, ad-hoc grants and in-kind services (Conn, 2011).

These two systems must work with each other and are co-evolving through this process, but are fundamentally incompatible at an organizational level. This creates many mutual misunderstandings, yet it also opens up useful “spaces of possibilities” where these systems can work together and where the horizontal peer forms of local systems and structures can be supported. Parts of the community sector can indeed be vertical hierarchical systems (charities or larger voluntary organizations) whereas smaller communities of interest, identity or place are likely to be more horizontally organized. Within the vertical hierarchical system of the university, scholars, researchers and teachers might be operating quite autonomously (Harney and Moten, 2013), opening up progressive spaces in universities which “are able to connect with community organizations and social movements and accomplish valuable counter-hegemonic work” (Choudry and Vally, 2020, p. 12).

Both university and community systems have internal networks. Universities across London have both formal and informal relations with each other. For example, as signatories to the Civic University Network or the Manifesto for Public Engagement, or as part of institutional networks (for example, the Russell Group or London Higher). Community groups are also networked either through organizations such as Just Space or specific issue-based networks solidarity and collaboration, sustaining horizontal work across different scales (Lipietz et al., 2014). Each system can also embed versions of the other system within itself. For example, efforts to open up more progressive spaces can be seen alongside institutional drivers to widen public engagement, and through practical co-production of knowledge through university-community collaborations.

Collaborative working and co-production have had a long tradition in different disciplines. Ostrom usefully defined co-production as “the process through which inputs used to produce a good or service is contributed by individuals who are not ‘in' the same organization” (Ostrom, 1996, p. 1073). Indeed, Ersoy (2017) points out in The impact of co-production: From community engagement to social justice, that co-production has to a certain extent replaced partnerships and contractualism as the main form of collaboration. However, this needs to be accompanied by an explicit “move towards more democratic involvement which…empowers community-oriented practices” (Ersoy, 2017, p. 3).

This broad trend toward co-production opens opportunities for different forms of knowledge production which are mutually beneficial for both community and university, in the eco-systemic dance between two different structural. These processes however, have to be accompanied by the awareness of differences in power, structures of organization, the wider agendas of decolonization of knowledge institutions, precarity, trust, forms of communication, forms of ownership and diversity of communication tools. The challenge includes finding ways of opening up “spaces of possibility” between the hierarchies of London-based universities in this case, and the dynamic, horizontal structures of community groups they currently and potentially could work with.

London

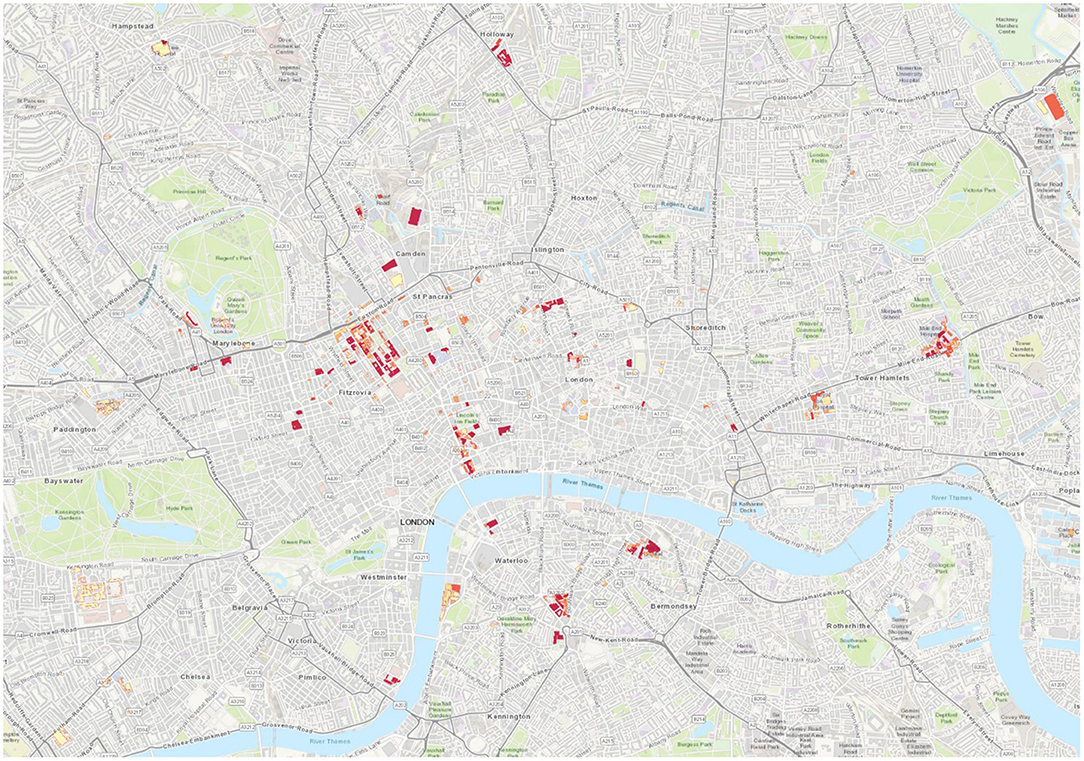

London hosts a diverse university sector, with more than 40 higher education institutions spread across the city (University of London, 2018; London Higher, 2021). London universities vary in size, from small, discipline specific colleges to large multi-disciplinary, multi-campus institutions. Seventeen autonomous university colleges are part of the University of London federation. There are significant differences in the research and teaching profiles, age, origins, income and financial stability, and estates of London universities. London's universities are primarily located close to the center of the city (Figure 1). Beyond central London there are notable, well-established universities (such as Queen Mary University of London, University of East London and Brunel University), as well as recent and planned new campuses for central universities who are expanding their estates (such as Kings College London, University College London and Imperial College London). Whilst the university sector faces many common challenges, these may be experienced very differently in different institutions. London universities vary in their relationships with local communities, with some founded explicitly to serve local educational needs while others have focused on international research agendas and students. Each university has a distinct public engagement profile, dependent on institutional priorities, subject strengths and staff interests and capacities.

Figure 1 illustrates the estates owned and used by universities in the Central London area, giving an indication of the concentration of real estate associated with higher education, and the distribution of the major universities in London. The spatial relationship the university has with its surrounding area, whether it is based in the urban center (e.g., University College London, Kings College London, London School of Economics) or in a suburb (e.g., University of East London, Brunel University, Kingston University) carries some important social and economic impacts for the city-region: “For the university, this urban location – even if it is not integral to the institution's identity – forces a relationship with other institutional actors and communities that are also inhabitant in the city” (Goddard and Vallance, 2014, p. 1).

The Just Space network included university members from its inception in 2007. Just Space community members have worked collaboratively with universities on a range of activities for more than a decade, on issues such as urban planning, environmental quality, social and racial equality, housing, and transport (Just Space, 2021). Significant achievements for the network include developing a community-led plan for London and facilitating community responses to the examination in public of the London Plan. University collaboration with community members is guided by the Just Space Research Protocol, which outlines principles and commitments to ensure mutual benefit and minimize harm (Just Space, 2018). Just Space's experience of university collaboration has been largely with “committed academics,” many of whom work under precarious employment conditions with limited institutional support or recognition of the value of their collaboration with grassroots groups.

In 2018 Just Space identified the opportunity to enhance collaboration with universities across London. Just Space member organization Just Map, identified and mapped specific community needs that could be met in through collaboration with universities, highlighted cases of best practice, and convened a workshop with community groups and committed university staff and students. This work clarified the need for better co-ordination of university-community engagement across London, which formed the basis for the Collaborate! project.

The Collaborate! Project

Community University Knowledge Strategy for London (Collaborate!) was a co-designed project funded by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) Impact Acceleration Account (IAA) at University College London (UCL). The EPSRC IAA is a funding allocation to universities in the UK who are in receipt of EPSRC research grants to facilitate impact from EPSRC funded research. To reflect the collaborative partnership, 50% of the £30,000 awarded was allocated to Just Space to facilitate community involvement in the project, while UCL's role was to engage university partners and manage the administration of the grant. The core project team was Richard Lee from Just Space and Sarah Bell from UCL, with Sona Mahtani employed by Just Space to lead community engagement and strategy, and Daniel Fitzpatrick working as a research associate for UCL.

The project aims were:

1) Document and share best practice in community-university partnership for urban research and action in London.

2) Develop a strategy and action plan for improved co-ordination and impact of community-university partnerships in London.

3) Identify resources required for implementation.

4) Launch a business plan for university and stakeholder investment to deliver the strategy.

The project plan included a steering group, a series of public events and working papers, and strategy launch and dissemination.

Steering Groups

The proposal included a steering group composed of equal numbers of community and university members. In the early stages of the project this was adapted to two separate steering groups for each constituency. This was to ensure community members were empowered to direct the project and that university members were aware of the focus on grassroots community partnerships, rather than preconceived institutional framings of community and stakeholder engagement. The separate steering groups developed rapport with the project co-ordination team and colleagues with similar interests. The groups had more free discussion and made open contributions to the project direction as trust was built with the project team and each other. When the steering groups met together they worked effectively from a shared understanding of the project and mutual interests, and clearer grounding in their own roles. The separate steering groups evolved to provide support networks within and across each constituency, and have formed the basis for implementation actions beyond the life of the project.

The university steering group included staff from UCL, Kings College London (KCL), Brunel University (Brunel), University of East London (UEL), Queen Mary University of London (QMUL), London Metropolitan University (London Met), University of the Arts London (UAL), Birkbeck University of London (Birkbeck), and the cross-sector representative group, London Higher. Steering group members held different roles within their university, for example, Vice Provost, professional services in London, public and civic engagement, and academic research and teaching. They had different experiences of community partnerships and different levels of power and influence within their own institutions. There were three women and six men on the group, with seven people identifying as white, one as black, and one Asian. Defining the focus of the project as grassroots community groups was an important first step with university steering group members, whose initial conceptualisations of “community” included wider civil society groups, local government, charities, large non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and the general public.

Community steering group members were recruited by Just Space, and were from community groups who had prior connections to the network and typically had prior experience of working with universities. The organizations were Just Map, Peckham Vision, Newham Union of Tenants, Grand Union Alliance, Community Centered Knowledge, Millbank Creative Works, Wards Corner Community Coalition, Westway 23, Equality and Human Rights Network, and Friends of Queen's Market. There were six men and five women on the community steering group, with three people identifying as black, two as Asian and five white. The issues of interest to the community groups included local and London-wide planning and development, the creative arts, racial equality, community development, food, disability rights, local economies and housing.

Early meetings of the separate steering groups focused on creating a shared understanding of the project, London communities and universities. This included analysis of the different motivations and needs of each group, and the complexity within both universities and community organizations. The early meetings provided clarity of the project purpose, and the aspirations and constraints of both universities and communities in building partnerships. Decolonization emerged as an early theme of high priority to community members, and influenced the delivery of the project as well as specific actions and themes in the project outputs (Harney and Moten, 2013; Bhambra et al., 2018). The two separate steering groups came together to plan the public events, and to provide feedback as the project developed, and co-produce the project outputs.

Best Practice Review

A review of best practice consisted of three tasks—a literature and internet search for UK and international case studies of universities engaging communities, a questionnaire for London-based universities on their work with community groups, and identification of community-based case studies of effective relationships with universities. The outcomes of the review informed the steering group discussions, public events and strategy development through internal discussion papers and presentations. The case studies were published in the project booklet, which was disseminated at the project conference (Just Space, 2019). The case studies were:

- KCL's programme to provide free meeting space to community groups.

- “Introduction to Housing Services” course offered for free to Lewisham Homes residents, delivered by London Met.

- Just Map's community mapping projects.

- UCL's Civic Design Continuing Professional Development Course delivered with Granville Community Kitchen and residents of the William Dunbar and William Saville Estates.

- Community leadership training provided by Birkbeck for community group leaders in Newham.

- Wards Corner Community Coalition collaboration with several universities to develop an alternative neighborhood regeneration plan.

- Future of London's Street Markets collaboration between multiple community groups and Leeds University.

- The London Journey and The Food Journey immersive training programmes delivered to university students and others by Community Centered Knowledge.

- The Local Energy Adventure Partnership (LEAP) micro-biodigestion model, which has collaborated with several London universities and demonstrated renewable energy and waste management technology in the Calthorpe Project, Camley Street Nature Park and other community spaces.

- The Engineering Exchange at UCL which supported collaboration between local community groups and engineering and built environment researchers.

- QMUL Legal Advice Center, providing free legal advice to local residents, with students supervised by academics.

- Milbank Creative Works collaboration with UAL to create a social hub supporting innovation, sustainability and creativity in the local community.

- 3D Print the Future of East London, a community arts project based in Loughborough University's campus in east London.

The review revealed examples of productive relationships at a project or programme level, innovative strategies from individual universities, and principles for good practice, but showed no evidence of a city-wide strategy involving multiple universities elsewhere in the world.

Public Events

Two public events were held to explore wider themes, share knowledge and experience, and gather input into the strategy and action plan. A workshop was held in July and a conference in October 2019. The public events are documented in a short film (Magar, 2020).

The public first workshop was held in partnership with Public Voice as part of the Tate Exchange, a series of community-based events hosted at the Tate Modern art museum in Central London. This half-day event at the beginning of the project focused on barriers and opportunities for stronger partnerships, and principles to underpin the strategy. It built on the event held as part of the same series in the previous year organized by Just Space and Just Map, which had formed part of the preliminary work. The workshop began with welcome from the project team and Public Voice host, followed by a presentation on the “The Nature of Community,” by Eileen Conn. A first session of small group work divided attendees into university or community sector groups, to identify synergies and barriers to collaboration. Plenary feedback facilitated communication of core issues from university and community perspectives. Small groups of mixed community and university delegates then worked to discuss practicalities of building and maintaining collaboration for mutual benefit. The final session allowed feedback and discussed next steps, including plans for the conference.

The second public event was the Collaborate! conference, held toward the end of the project, at the East London Tabernacle, a community space owned and operated by a church group. The conference booklet, which was available to delegates as they arrived, presented the case studies of existing community collaboration, and formed an important documentation of the project (Just Space, 2019). Following a general introduction to the project and its preliminary outcomes, four of the case studies from the booklet formed the basis of breakout groups where collaborators discussed their work with delegates. During the tea break university staff were available to provide one-on-one advice surgeries to connect community members to relevant academics and programmes. The second series of breakout group addressed themes that had emerged from the steering groups—decolonisation of universities, community economic and industrial strategies, community spaces and the need for a London-wide strategy for community-university collaboration. After the feedback from the workshops a discussion panel from the community and university steering group addressed key themes, before an independent summary from a community-based planner and organizer. The conference ended with an evening meal. Evaluation of the event indicated that it succeeded in achieving its objectives, and that it created an environment where community and university members contributed on equal terms.

Strategy and Actions

The steering group meetings and public events, together with case studies, research, and analysis, provided the basis for developing a strategic actions document and a charter for community-university partnerships in London. The strategy addresses the purpose and principles of partnerships between universities and grassroots community groups, and outlines actions for implementation through organizational governance and structures, facilitating connections, the curriculum, access to resources and evaluation. The actions are:

1) A Charter for Community-University Partnerships in London for universities and community groups, outlining shared principles and commitments.

2) Adopt a protocol for ethical community-based research, teaching and public engagement by university staff and students, based on the Just Space research protocol.

3) Universities and community groups to share strategic plans with each other, including processes for how they are developed, to consider how community groups can contribute to future strategic planning for universities and how universities can enhance and support effective community strategies.

4) Universities to widen and promote opportunities for community representation on committees and boards, including Senate or Council, whilst working to ensure their presence is effective and relevant.

5) Community groups to be supported to develop case studies based upon experiences of engagement with universities to decolonize university structures and processes and transform relationships with all affected, particularly with Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic communities.

6) Establish London Community - University Collaborate network to build partnerships and develop suitable, and decolonial, systems and structures for the interface between local community groups and anchor universities, located in different parts of the city.

7) Expand, promote, support and co-ordinate community brokerage services in London universities, involving community groups in service design and delivery.

8) Universities and community groups to explore opportunities for greater, more effective interfaces through co-produced networking and partnership building activities that are adequately resourced.

9) Develop a pilot residency program for the collaborative exchange of university staff and community members.

10) Publish a prospectus document of strengths of different universities for community groups to know where to access specific expertise in London. This will work alongside ongoing community-led mapping of community groups and their activity and needs, which needs to be constantly updated.

11) Engage expertise from diverse community groups to develop learning materials for use across different university-community programs that support wider and deeper community engagement and address issues in London that are challenging and meaningful.

12) Establish a platform within London universities to share best practice and materials for decolonizing the curriculum, including co-production of curriculum with organizations and members of colonially exploited communities.

13) Establish Action Learning Sets of university staff and community members on issues of mutual interest, such as partnership working, decolonization and curriculum design.

14) Universities to provide formal recognition and accreditation of learning from community members who contribute to and participate in community-based projects or teaching, to support lifelong learning and widen access to education. Recognition should also be given to learning from the experiences of community groups, and the access provided to data.

15) Free places available to eligible community members on short-courses or summer schools that involve community-based learning or case studies. Community groups can be supported to offer residencies for staff and students on such courses within community spaces.

16) Universities to work with grassroots community groups to develop a process for registration of community groups for enhanced access to university resources.

17) University libraries to work with registered community groups to provide access to academic journals, books and other resources.

18) Universities to provide no cost room hire to registered community groups, share best practice and publicize to appropriate community groups.

19) Community groups to work with university libraries and research administration to develop policies and systems that provide open access to academic research publications.

20) Research outputs from community collaboration or participation to be disseminated in a format that is appropriate, accessible and agreed by community members (see Just Space research protocol).

21) Establish a comprehensive, long term evaluation framework for community-university partnerships.

Charter

A Charter for Community University Partnership was drafted to fulfill Action 1 of the strategy. The purpose of the charter is for universities and communities to commit to core principles as the foundation for undertaking further action. Future signatories of the London Charter for Community University Partnership agree to the following commitments:

1) Community-based research, teaching and public engagement are undertaken in accordance with agreed ethical protocols, jointly produced by community groups and universities, that seeks mutual respect, reciprocity and recognition.

2) Universities and community groups share strategic plans and governance processes with each other and work together to identify opportunities to strengthen partnership in decision-making and planning.

3) Structures for supporting university-community partnerships recognize the different forms of organization of universities and community groups and respond to each other's needs and capacities.

4) Communities that experience marginalization, particularly Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic communities, are supported to engage with universities to decolonize university structures, processes and curriculum, and transform relationships with all affected.

5) University curriculum development in relevant programs engages expertise from community groups in design and delivery of modules and provides appropriate recognition for community contributions.

6) Universities work with community groups to develop systems for sharing resources such as university spaces, libraries and academic publications.

7) Evaluation of the impacts of community-university partnerships is undertaken within a comprehensive, long term framework.

Implementation

The project achieved its objectives of developing a strategy and actions for supporting stronger community-university partnerships in London. The strategic actions are not a plan for implementation, as the project has not yet been able to secure ongoing funding or long-term commitment from partners to implement the complete strategy. An initial business model of contributions from subscribing universities has been disrupted by the financial and operational impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic for universities. However, individual actions are being implemented, include university funding of specific, small projects.

The steering committee structure has continued beyond the project to explore opportunities for implementation and future funding, working remotely and meeting online during the pandemic. The community steering committee undertook a detailed review of fundraising options to support a Collaborate! network organization to implement the strategy across London. The university steering committee members identified priority actions that were pursued within their own organizations and developed small working groups across institutions to share best practice in supporting implementation. Implementation within universities has been dependent on the level of influence of the steering committee member and their capacity to commit resources and time. In the short term, priority actions are focused on decolonization (action 5), access to resources (actions 16–19) and establishing action learning sets (action 13).

Discussion

The Collaborate! project succeeded in its aims through a strong commitment to partnership and co-production in practice (Ersoy, 2017). The project was community-led, building on previous unfunded work by Just Space, to address a specific need identified by grassroots community groups in London. Funding for the project was secured through a university funding scheme, and shared equally between UCL and Just Space, providing autonomy and flexibility in how the project was delivered. Community leadership enabled strong participation from community members in the steering committee and public events. Community resilience and adaptability has enabled progress toward implementation in the changing circumstances of the pandemic, as community groups have greater flexibility and responsiveness than the hierarchical structures of universities (Conn, 2011).

The pandemic has provided both a threat and opportunities for stronger collaboration between universities and community groups. The pandemic and lockdowns have highlighted social and environmental inequalities in London, and the role of universities in the local economy and communities. This provides an opportunity for Collaborate!, as university leaders seek to reposition their institutions to demonstrate their immediate social value. However, resource constraints, increased workloads and highly challenging conditions for communities and universities alike have also led to a focus on “core-business” of teaching and essential research. While community partnerships remain an additional activity for individual staff and university administration, the future development of university actions will be constrained to implementation of high priority strategic actions.

Community leadership in co-producing the strategy and implementing actions was important as a means to avoid unhealthy competitiveness between universities in the same city who are working toward the same objectives. While individual universities have developed strategies to be more “outward looking” this typically refers to non-university partners (Watson et al., 2011; Goddard and Vallance, 2014). Beyond collaboration in research, and higher education policy lobbying, it is uncommon for universities as institutions to work together, despite clear common interests. Each institution develops its own strategy and partnerships, with limited motivation and significant barriers to working with other universities. Community leadership of Collaborate!, in the project and in future delivery, is an important mechanism for maintaining the “space of possibility,” avoiding fragmentation between universities and ensuring a city-wide perspective on the challenges and benefits of community partnerships (Conn, 2011).

Collaborate! steering committee members, both university and community, were invited to join the project because of their expertise and experience, across a range of groups and institutions. They were not “representative” of particular interests, but were able to contribute to the project based on lived and professional experience, and relevant knowledge. Community members are often subject to expectations of “representativeness” in their engagement with universities in a way that industrial or policy partners are not. Industrial advisors or collaborators in university research, teaching and governance are rarely scrutinized based on how well they “represent” their sector of the economy or technical specialty. The “tyranny of representation” applied to community members by contrast often precludes meaningful engagement of committed, knowledgeable local people with university structures and activities. The success of Collaborate! demonstrates the value of recognizing specific community expertise in strategic partnerships, without expecting individuals to “speak for” complex constituencies.

Co-production of the project outputs was an essential feature of the project, enabling deep collaboration and commitment. However, the implementation of the strategy is constrained by the profile of the participants in the co-production process. The hierarchical structures of the university limit the immediate uptake of the project outcomes, depending on the power and influence of University participants in the process (Conn, 2011; Ersoy, 2017). Community engagement remains lower priority to leadership addressing teaching, research and industry partnerships, particularly under the financial and operational difficulties presented by the pandemic. Senior leaders involved in the process were able to immediately implement priority actions and commit funding, while professional services and academic participants worked to align existing projects and develop stronger support networks. Broader implementation requires ongoing commitment and co-ordination, which community partners are most strongly placed to deliver as a non-hierarchical network than universities who are constrained by hierarchy and competition (Harney and Moten, 2013).

The Collaborate! project is of wider relevance to other cities and communities (Goddard and Vallance, 2014; Ersoy, 2017). Its applicability to other contexts is constrained by its focus on urban and planning issues, as reflective of the core interest of Just Space members and required to demonstrate relevance to the funder. The UK and London context provide specific boundaries for policy and social replicability, but the core principles of co-production and partnership working, in the outcomes as well as the process, will be of relevance to other democratic jurisdictions with active grassroots civil society.

Conclusion

Repurposing the universities for sustainable human progress requires expanding the range of stakeholders and partners they engage with and the quality of that engagement (Maxwell, 2014). Effective engagement with grassroots community groups and emerging social movements are particularly important in addressing current and future crises (Ersoy, 2017). However, the hierarchical structures and competitive cultures of universities are fundamentally incompatible with the organizational form of many groups working for sustainable change (Conn, 2011).

The Collaborate! project began with community groups identifying the potential for mutual benefit from a more strategic approach to university partnerships across London. The city scale reflects community interests in knowledge and resources sharing, beyond the expertise and programmes of any specific university. The co-production of the project began with the initiation and funding, and continued through the development and delivery of outputs, and implementation of agreed actions. A commitment to co-production was evident in the project structures and roles, as well resourcing. The project created a “space of possibility” which drew on both the autonomy and adaptability of community partners, and the formal structures and resources of universities.

Co-production processes and structures supported trust and commitment between participants in the project (Ersoy, 2017). However, implementation has been constrained by the relative power and level of influence of participants, particularly those working in universities. Co-ordination and implementation of university actions is limited by the hierarchy and fragmentation of the sector. For this reason, it is important to move beyond co-production to co-delivery, drawing on the strengths and flexibility of community-based partners to act beyond the boundaries of individual universities. Securing the “spaces of possibility” created by Collaborate! requires continuation of intermediary organizational forms, decentring power and resources from university hierarchies into genuinely collaborative structures (Conn, 2011).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary materials, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author Contributions

SB is the co-convenor of the project with RL, who provided oversight to the paper. DF led the writing of the Context section of the paper, contributed to the Collaborate, and Discussion sections. SM provided practical delivery of the project, contributed to analysis, outputs, evaluation, and led the writing and production of the best practice case study document, which supports this paper. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was funded by the UK Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, UCL Impact Acceleration Account 2017–2020.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This case study was made possible by the contributions of members of the steering group, including Victor Adegbuyi, Toby Laurent Belson, Robin Brown, Eileen Conn, Nicolas Fonty, Hester Gartrell, Sarah Gifford, Christine Goodall, Shirley Hanazawa, James Jennings, William Leahy, Darryl Newport, Saif Osmani, Wilfried Rimensberger, Shibboleth Shechter, Matthew Scott, Paresh Shah, James Tortoise-Crawford, and Mama D Ujuaje.

Footnotes

1. ^From interview with Dr. Gemma Moore, Evaluation Manager, Public Engagement, University College London (UCL), 2019.

2. ^https://www.vitae.ac.uk/researchers-professional-development/about-the-vitae-researcher-development-framework

References

Bhambra, G. K., Gebrial, D., and Nişancioglu, K., (eds.). (2018). Decolonising the University. London: Pluto Press.

Choudry, A., and Vally, S. (2020). The University and Social Justice: Struggles Across the Globe. London: Pluto Press.

Civic University Network (2020). Civic Agreements. Available online at: https://civicuniversitynetwork.co.uk/civic-agreements/ (accessed January 31, 2021].

Conn, E. (2011). “Community engagement in the social eco-system dance,” in Moving Forward With Complexity, eds A. Tait, and K. A. Richardson (Litchfield Park, AZ: Emergent Publications), 285–308.

Ersoy, A. (2017). The Impact of Co-production: From Community Engagement to Social Justice. Bristol: Policy Press.

Just Space (2018). Research Protocol. Available online at: https://justspace.org.uk/history/research-protocol/ (accessed January 31, 2021).

Just Space (2019). Collaborate. Available online at: https://justspacelondon.files.wordpress.com/2019/10/justspaceucl_final-23-oct2019.pdf (accessed January 31, 2021).

Just Space (2021). About Just Space. Available online at: https://justspace.org.uk/about/ (accessed January 31, 2021).

Lipietz, B., Lee, R., and Hayward, S. (2014). Just space: building a community-based voice for London planning. City Anal. Urban Change Theory Action 18, 214–225. doi: 10.1080/13604813.2014.896654

London Higher (2021). About London Higher. Available online at: https://www.londonhigher.ac.uk/about/ (accessed January 31, 2021).

Magar, J. (2020). Collaborate. Available online at: https://youtu.be/G_mISxL8U2w (accessed April 9, 2021).

NCPE (2020). What Does an Engaged University Look Like? National Coordinating Centre for Public Engagement. Available online at: https://www.publicengagement.ac.uk/about-engagement/what-does-engaged-University-look (accessed April 9, 2021).

NCVO (2020). UK Civil Society Almanac 2020. National Council of Voluntary Organisations. Available online at: https://almanac.fc.production.ncvocloud.net/profile/size-and-scope/ (accessed January 31, 2021).

Ostrom, E. (1996). Crossing the great divide: Coproduction, synergy, and development. World Dev. 24, 1073–1087. doi: 10.1016/0305-750X(96)00023-X

Smith, A., Fessoli, M., Abrol, D., Elisa, A., and Ely, A. (2017). Grassroots Innovation Movements. London; New York, NY: Routledge.

Tokar, B., and Gilbertson, T. (2020). Climate Justice and Community Renewal: Resistance and Grassroots Renewal. London; New York, NY: Routledge.

University of London (2018). Planning and Higher Education in London. Available online at: https://uol18.maps.arcgis.com/apps/MapSeries/index.html?appid=a2e6bc9593e64c8d966f3b86a33c3109 (accessed March 30, 2021).

Watson, D. (2007). Managing Civic and Community Engagement. Maidenhead: McGraw Hill, Open University Press.

Keywords: grassroots action, decolonization, bottom-up approach, urban, citizens

Citation: Bell S, Lee R, Fitzpatrick D and Mahtani S (2021) Co-producing a Community University Knowledge Strategy. Front. Sustain. 2:661572. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2021.661572

Received: 31 January 2021; Accepted: 21 May 2021;

Published: 18 June 2021.

Edited by:

Iain Stewart, University of Plymouth, United KingdomReviewed by:

Mark Reed, Newcastle University, United KingdomPaul Michael Manners, National Co-ordinating Centre for Public Engagement, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2021 Bell, Lee, Fitzpatrick and Mahtani. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sarah Bell, cy5iZWxsQHVuaW1lbGIuZWR1LmF1

Sarah Bell

Sarah Bell Richard Lee2

Richard Lee2 Daniel Fitzpatrick

Daniel Fitzpatrick Sona Mahtani

Sona Mahtani