- 1Department of Business-Administration, University of Shkoder, Shkoder, Albania

- 2Department of Tourism, University of Shkoder, Shkoder, Albania

Albania’s transition from a centralized to a market economy has resulted in a fragmented and mostly informal business landscape, where small enterprises dominate and sustainability-oriented strategies remain underdeveloped. However, with EU accession, Agenda 2030 commitments, and global climate objectives, there is a growing urgency to align local business models with circular and inclusive practices. This study aimed to explore how sustainable business model frameworks can be effectively applied in emerging contexts by the Triple Layered Business Model Canvas (TLBMC) to Mrizi Zanave, a leading agrotourism enterprise in North Albania. The research employs a qualitative case study approach, combining two semi-structured interviews with founders/managers and desk research across multiple data sources, including the National Business Center registry, company websites, and social media communications. The results indicated that Mrizi Zanave creates value across economic, social, and environmental layers by embedding traditional knowledge, regional supply chains, and community-based employment. Quantitatively, the enterprise cooperates with 400 smallholder farmers, employs 105 staff and hosts approximately 90,000 visitors annually [As by the latest data delivered by the company on National Business Center registry (data for the business fiscal year 2024)]. However, formal measurement of environmental and social impacts remains limited, reflecting institutional and infrastructural constraints. By operationalizing the TLBMC in a context shaped by structural informality and historical marginalization, the study contributes to the international literature on business model innovation in post-socialist and emerging European contexts, particularly within the Western Balkans. It highlights both the opportunities and challenges of place-based entrepreneurship for sustainable rural generation in the Western Balkans.

1 Introduction

With ongoing changes in the global economy, it is crucial for businesses to prioritize being customer-oriented. Practice has shown that managers often enter the market by imposing their ideas on the customer. This may pose an issue as their concepts may not align with customer expectations, potentially leading to failure—a scenario undesirable for any manager. Thus, the business model (BM) concept has been the focus of academics and practitioners over the last few decades (Zott et al., 2011), even though models and discussions about them had been initiated before the emergence of the BM in management. The idea of BM is considered valuable for managers to improve their overall performance (Baden-Fuller and Morgan, 2010; Giesen et al., 2010), but also the innovation on BM is emphasized (Barjak et al., 2014; Teece, 2010; Baden-Fuller and Haefliger, 2013). It is already well-known that innovation on BM is more successful than innovation on products and processes (Gassmann et al., 2013). Circular business model innovation (CBMI) emerges as a strategic necessity for enabling transition toward a circular economy by rethinking how value is created, delivered, and captured in alignment with regenerative and restorative principles. CBMI involves redesigning products and services and restructuring the entire business logic to support closed-loop systems, resource efficiency, and long-term sustainability (Pieroni et al., 2019). The process is inherently complex, often requiring firms to challenge dominant linear paradigms and engage with multiple stakeholders across the value chain. This transformation is both systematic and experimental, calling for iterative design, prototyping, and stakeholder integration. Many researchers have already spoken about successful BMs, but a BM is not successful on its own. It may be a good BM, but it needs implementation. As a good BM may be mismanaged and may fail, the other way, a “poor” BM may result in success as it is managed well and the proper abilities are used during implementation. The implementation of BM and its management involves translating the model into more concrete elements, such as the business structure (hierarchy and divisions), its vertical and horizontal functioning (responsibilities, chain of command, and interfunctional cooperation), infrastructure, and systems. Furthermore, the implementation of BM must be financed by both internal and external financial resources (Osterwalder et al., 2010), embedding dynamic capabilities (Teece, 2018) and generative mechanisms (Lecocq and Demil, 2010), which are capable of adaptation, reconfiguration, and coevolution in response to changing contexts. The TLBMC, designed by Joyce and Paquin (2016), interrogates the nature of BM’s existence: Is it a representation, a process, a socio-material configuration, or a performative act? By addressing these questions, TLBMC supports the development of sustainability-oriented business, requiring deep reflections on what BMs are and how they come into being. Recent policy discourse in the Western Balkans highlights the need to promote sustainable transitions at the regional level (Rexhepi Mahmutaj et al., 2025). As Albania aligns its entrepreneurial ecosystems with broader EU frameworks, empirical studies are essential to support locally adapted circular strategies, particularly within informal and rural economies. And applying the TLBMC to a practical case study (like Mrizi Zanave) involves positioning the canvas not only as an analytical tool but also as a reflective, relational, and context-sensitive framework. Through the TLBMC, the situated logic of the case becomes visible and traceable across systematic dimensions, allowing the broader commitment to be visualized, tracked, and debated, offering a concrete guide for further model innovation.

2 Methodology

This research adopts a qualitative case study approach, underpinned by two semi-structured interviews with the managers and owners to explore the BM of the agrotourism enterprise Mrizi Zanave.

The choice of agrobusiness, and especially an agrobusiness model like Mrizi ZanaveI, is deliberate and theoretically informed. Agrobusinesses in Albania, especially those practicing slow food and place-based development, represent a fertile ground for exploring new business models in the context of rural resilience, cultural recognition, and circularity. As Albania continues to transition economically and institutionally post-1990, businesses in the agrotourism sector often serve as catalysts for socio-economic transformation in marginal rural areas. This aligns with the wider goals of CBMI, which emphasize place-based regeneration, stakeholder inclusion, and value recirculation (Pieroni et al., 2019; Santa-Maria et al., 2022). Agrotourism provides a unique lens through which circularity principles, such as short supply chains, local valorization, and food system sustainability, can be investigated empirically.

To analyze and visualize the BM, this study applies the Triple Layered Business Model Canvas (TLBMC) developed by Joyce and Paquin (2016). Unlike the traditional Business Model Canvas (BMC) (Osterwalder et al., 2010). The TLBMC includes three integrated layers: economic, social, and environmental. This tool was chosen due to its suitability for exploring sustainability-oriented business models holistically. The TLBMC facilitates a systems thinking approach to business design, helping to uncover dynamic interconnections between stakeholders, resources, environmental flows, and societal impacts (Hassan and Faggian, 2023). This is especially relevant in CE research, where the interplay between value creation, resource loops, and cultural meaning must be simultaneously understood and communicated (De Angelis, 2022; Jha et al., 2024). In agrotourism contexts, where heritage, food systems, and local economies intersect, the TLBMC has shown particular promise in visualizing and designing regenerative business strategies (Akomea-Frimpong et al., 2024; João et al., 2025). These approaches link local gastronomy with rural livelihoods and regional branding, aligning well with the values embedded in sustainable tourism, sustainable consumption behaviors, and place-based entrepreneurship. Therefore, the TLBMC supports the design and evaluation of circular strategies that are deeply embedded in regional systems, an essential feature of Mrizi Zanave, which depends heavily on local supply chains, cultural heritage, and community-based governance. Through the application of this model, the study not only captures the complexity and sustainability of the business but also reveals potential areas for replication and policy support in other regions undergoing transition.

The methodology was designed to gain in-depth insights into how sustainability is embedded in the firm’s economic, social, and environmental dimensions. Two semi-structured interviews were selected as the primary data collection tool due to their flexibility in uncovering rich, contextual data while allowing space for new themes to emerge through the interaction with respondents (Buriro et al., 2017). This was a deliberate choice given the exploratory and case-focused design of the study. In the Albanian context, owners/managers hold a central role in decision-making, governance, and strategic orientation of agrotourism businesses, making them the most relevant informants for understanding the internal logics of the business model. Interviews are especially useful in BM research where the aim is to understand internal reasoning, decision-making processes, and stakeholder dynamics from the perspective of business owners and managers (Clausen, 2012).

The interviews were conducted with informed consent, following ethical guidelines for qualitative research. Participants were assured confidentiality, and identifying information was omitted. Since the interviews involved adult business representatives discussing professional matters, the risk of ethical issues was minimal, and no institutional ethical clearance was required in Albania for this type of research.

We acknowledge that the small sample limits the depth of perspectives; therefore, triangulation was essential. To reduce bias, we incorporated complementary viewpoints through extensive desk research, analysis of Booking-com customer reviews, and open data from the National Business Center (NBC), a governmental platform that provides open access to records for all registered businesses. This allowed us to capture not only managerial perspectives but also the lived experiences of customers, interaction with suppliers, and the employment figures of staff.

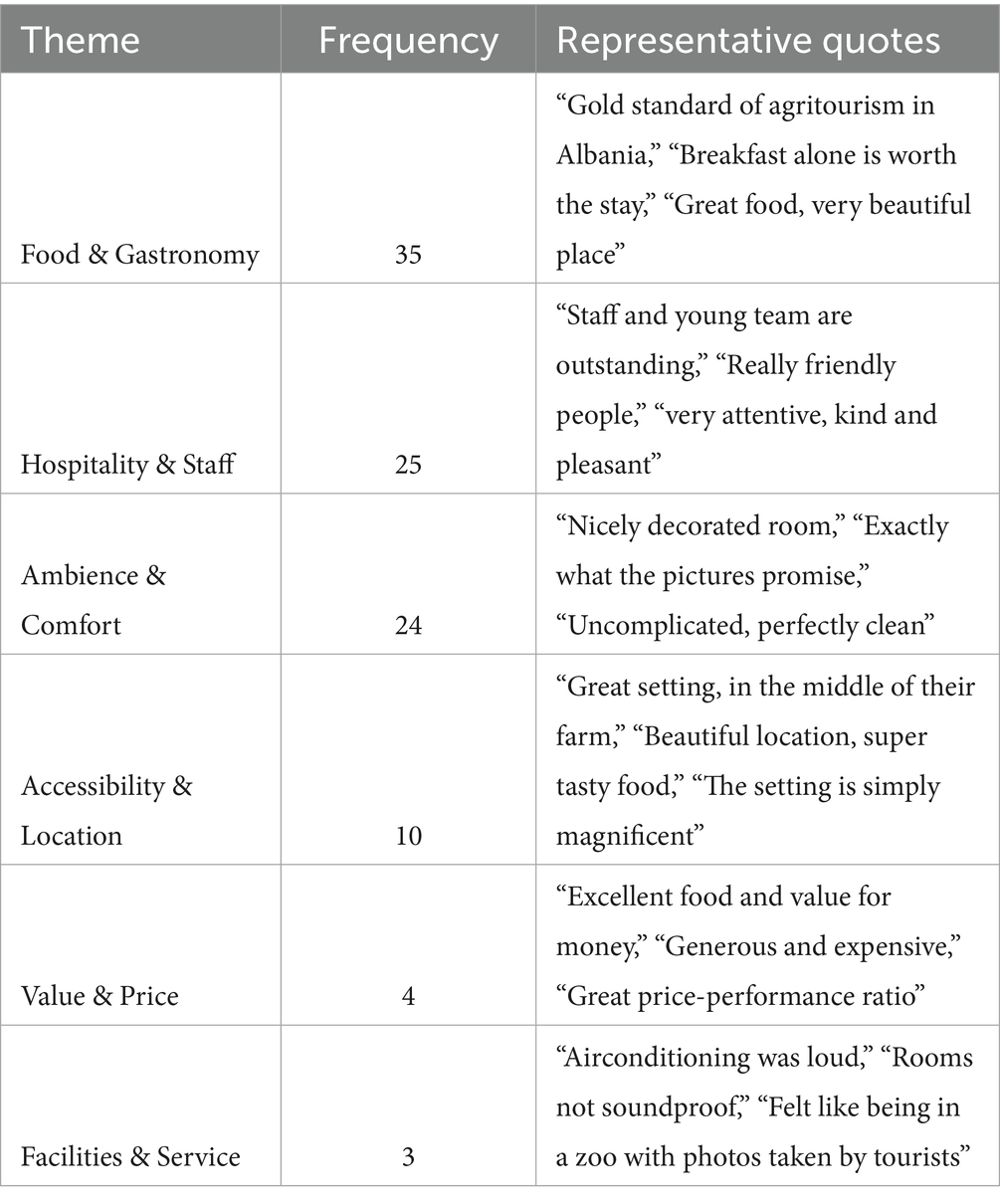

The Booking platform contained a total of 2297 reviews covering the period from 30 August 2022 to 29 August 2025. For this study, we focused on a subsample of the August 2025 reviews (in total, 68). This subsample was selected as a recent and information-rich corpus, allowing for a more contemporaneous understanding of guests’ experiences and facilitating triangulation with the interview data. We have to consider also that the customers giving feedback on Booking.com experienced all the services of the business (accommodation, restaurant, and shop). Following established approaches in qualitative research (Braun and Clarke, 2006; Flick, 2018). We conducted a thematic analysis of the review texts. Both the “positive” and “negative” comments were included, ensuring a balanced capture of strengths and weaknesses. An inductive-deductive strategy was applied; while the coding began with open reading of the material, categories were progressively structured around six thematic areas frequently highlighted in hospitality and tourism research, namely “food and gastronomy,” “hospitality and staff,” “ambience and comfort,” “accessibility and location,” “value and price,” and “facilities and service.” Representative quotes were extracted to illustrate each theme. Although the dataset is limited to 1 month, saturation was evident, as the same themes appeared repeatedly across reviews. This analytical choice allowed the study to employ triangulation of methods (Denzin, 2017), thereby enhancing validity by combining self-reported interview data with unsolicited user-generated content from Booking.com.

The dataset from NBC spans from 2012. For this study, we focused on the period from 2019 to 2024, which captures the latest years, including the COVID-19 period when there were limitations on free movement, forcing companies to adapt and find ways to remain in the market. The analysis focused on relative changes year-over-year in key indicators, including annual turnover, net profit, and long-term assets.

As environmental data at the enterprise level are not systematically reported in Albania, this study adopted a proxy-based estimation approach. Following international benchmarks (Nicolae, 2017; World Tourism Organization, 2022), we calculated approximate indicators for energy use and associated CO2 emissions, food waste generation and reuse, water consumption per guest night, and reduction of food miles through local sourcing. These proxies were complemented by qualitative evidence from interviews and guests’ reviews mentioning sustainability practices. Although approximate and not including all customers (only those using accommodation service who gave feedback on the Booking platform), these calculations allow us to integrate an environmental dimension (the first time in Albanian business) into the triangulation of economic and social data.

This qualitative study design relied on triangulation across heterogeneous sources, compensating for the limited number of interviews. This combination of interviews, user-generated content, official records, and proxy-based calculations provides a robust foundation for analyzing the economic, social, and environmental dimensions of Mrizi Zanave’s business model.

3 Results

3.1 Framing sustainable business models

The study of BMs has gained considerable attention over the past few decades, particularly in the context of sustainability and CE transitions. According to Heidegger (2010), existential ontology, particularly his notion of “being in the world” (Dasein), suggested that BMs are to be conceptualized not as static entities but as rational constructs formed through situated practice. Mason and Spring (2011) propose that BMs are structures of activity rather than simply plans or tools. Such an approach echoes Latour’s actor-network theory (Latour, 2005), wherein a BM is a network effect, stabilized through continuous negotiation among human and non-human actors (technologies, legal norms, platforms, etc.). Emphasizing the concept of “becoming” over “being,” which is inspired by process theory, particularly promoted by Whitehead (2010) and Bergson (2002), the perspective views of BM is not a thing but as a process that develops over time, making BM emergent, inseparable from the context in which it is embedded. Furthermore, even if the BM concept initially emerged to elucidate how companies create, deliver, and capture value (Magretta, 2002; Osterwalder et al., 2010), contemporary discussions frame BM innovation as a strategic necessity for organizations navigating within complex socio-environmental contexts (Teece, 2010; Baden-Fuller and Haefliger, 2013). Besides circular BM innovation as a strategic necessity, how businesses operate in alignment with regenerative principles, aiming to reduce waste, extend product lifecycles, and establish closed-loop systems (Pieroni et al., 2019). Circular BM innovation emphasizes redesigning not only products and services but also the fundamental logic of business operations. Muller et al. (2025) considered that a system-thinking-based sustainable BM framework is important to introduce feedback mechanisms, scenario planning, and stakeholder networks to support dynamic decision-making. Furthermore, Lozano et al. (2021) argued that visual tools supporting systematic insights are crucial for enabling sustainable transitions across organizations. This transition requires collaboration, systems thinking, and stakeholder integration Santa-Maria et al., 2022. Systems-thinking approaches to sustainable business modeling reinforce the need for integrated tools. Tools like TLBMC have emerged as practical and conceptual instruments for mapping and assessing circular BM innovation developed by Joyce and Paquin (2016). The TLBMC extends the original BM Canvas by incorporating social and environmental dimensions, which are added to the economic layer, resulting in three distinct but interconnected layers that engage the user in a process of meaning-making. Through these interactions, the BM is co-constituted by actors, systems, and materialities. This system-thinking tool enables businesses to visualize their value creation holistically, accounting for ecological flows, social impacts, and stakeholder dynamics. Heidegger (2010) emphasized that entities gain meaning through use and context, rather than through abstract categorization.

Within the Albanian context, the adoption of such integrated frameworks is particularly relevant given the nascent stage of sustainability practices and BM innovation. Through the TLBMC layered structure, a different way of being in business is enacted, one that foregrounds ecological embeddedness and social responsibility as intrinsic to value creation, rather than externalities. Dionizi and Kercini (2025) argue that sustainable BMs in agritourism, like the case in the study, are instrumental in achieving Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and enhancing regional resilience. These models promote value chain integration, community participation, and environmental stewardship (Dionizi and Kercini, 2025), aligning well with the TLBMC structure, which has the capacity to mediate conversations between diverse stakeholders.

3.2 Triple layered business model canvas and sustainable business model transformation

For an established organization, revisiting and transforming its BM becomes a strategic necessity in response to evolving market dynamics and sustainability pressures (Kropfeld and Reichel, 2019). However, such a transformation often encounters resistance, as managers tend to adhere to familiar models that offer them operational comfort and a sense of identity. This inertia can be overcome through strategic agility, which enables the organization to anticipate environmental shifts, unify internal commitment, and reallocate resources to support new value creation logics (Doz and Kosonen, 2010). Achieving this transformation is not straightforward. It requires maintaining existing performance while engaging in experimentation to develop a new model, a tension that often results in the temporary coexistence of old and emerging models. To navigate this complexity, structured tools such as the BMC have been widely adopted. Initially, researchers (Osterwalder, 2004) proposed that the BMC provides a shared visual framework for practitioners and researchers to communicate and reflect on business logic. Nonetheless, as societal and environmental challenges intensify, the traditional BMC’s narrow economic focus has been increasingly critiqued for overlooking the full spectrum of stakeholder and system-level impacts (Osterwalder et al., 2010; Bocken et al., 2016). In response, extended tools such as the Triple Bottom Line (Savitz, 2013), Value Proposition Canvas (Pokorná et al., 2015), and most notably, the TLBMC (Pigneur et al., 2015) have emerged. These models aimed to integrate the economic, environmental, and social dimensions of value creation, aligning with the triple bottom line philosophy (Joyce and Paquin, 2016; Chaves and Raufflet, 2020).

TLBMC, in particular, offers a practical framework for operationalizing systems thinking in sustainable business model design. It maps value creation across three interrelated layers (economic, environmental, and social), facilitating a holistic view of business activity and its systematic impacts (Joyce and Paquin, 2016). Rather than simply extending the BMC, the TLBMC reframes it. It helps firms not only diagnose current sustainability gaps but also articulate transformation pathways over time (Chaves and Raufflet, 2020).

Researchers (Muller et al., 2025) argued that embedding sustainability requires a shift toward dynamic modeling that captures interdependencies. The TLBMC embodies this logic, enabling organizations to reflect on their embeddedness in larger social-ecological systems. In terms of Heideggerian philosophy, this involves a shift from viewing businesses as isolated “essences” to understanding them as “beings-in-context,” interwoven with ecological and social relations (Heidegger, 2010). This view is echoed in Jha et al. (2024), who underscore the need for stakeholder coordination and long-term thinking in BM transitions, precisely what the TLBMC facilitates while remaining accessible to practitioners.

In the context of this study, the TLBMC is deployed as both an analytical and transformative tool. It offers a visual and strategic guide to map Mrizi Zanave’s BM and to uncover how environmental sustainability and community engagement are embedded in its operations. Drawing on focused interviews (Clausen, 2012; Buriro et al., 2017) and following the structured elaboration by Pigneur et al. (2015) and Lewandowski (2016). We completed the TLBMC for the case.

Recent studies in Albania affirm the relevance of this approach. Dionizi and Kercini (2025) propose sustainable BM patterns tailored to the agritourism sector that emphasize circularity, local resource use, and community value creation. Our case study of Mrizi Zanave exemplifies how these models can be grounded in practice, aligning heritage, sustainability, and innovation through a system-oriented business logic.

3.3 Sustainability explored through the case study

“Mrizi Zanave” is an agro-touristic farm where the movement “Slow Food Tourism” was launched in Albania. It is situated in a rural area in North Albania, a village that has experienced great persecution during the communist era in Albania (before 1990). There was an internment camp for the people contradicting the ideology of the time, being evidence of suffering, fear, and death (Lubonja, 2021). The place where many people once suffered from hunger has now become a food laboratory, recognized for its natural approach to producing local products. “Mrizi i Zanave” was one of the first local businesses initiating the reevaluation of the territory, visualizing the local economy as a turning point in the development of this abandoned city. This agro-touristic farm maintains a cooperative relationship with 400 small-scale farmers, obtaining 90% of the products from the region. It has a significant impact on the development of the region. From 1989 to 2001, Albania underwent a significant demographic movement. Lezha (the district part of which is the village) had one of the highest levels of rural immigration (INSTAT, 2024) during this period. Villages were abandoned, leaving land uncultivated. But things happened when two entrepreneurs (Altin & Anton Prenga) returned from Italy (where they lived and worked for 15 years) and opened the business “Mrizi i Zanave.” The business was a source of inspiration for the local farmers (who collaborated with it) and other entrepreneurs in the region for coping with the new business model. The tradition, which had shrunk during the communist era due to starvation caused by collectivization and the damaged history of the village, presented a challenge for this business to revive everything from scratch. The rediscovery of tradition, essentially based on food and typical products, the past dark regime, and some cultural attractions in the region, has brought a new alternative for tourism development. The preparation realized at the food processing center and the variety of food offered a powerful way of expressing culture and local heritage. With the deep commitment “Think global, eat local,” the business combines sustainable agriculture, agritourism, and family heritage. With approximately 20 hectares of cultivated land, the business has introduced vegetables that are not commonly grown or even known by farmers but are suitable for the Mediterranean climate. Despite insufficient grape production for winemaking, they collaborated with over 400 local farming families in the area to provide dairy, meat, and honey. Their on-site facilities include a restaurant, farm dairy shop (selling their products and also promoting other local production), winery, bakery, and guest accommodation, blending gastronomic, agricultural, and hospitality operations (Sherifi, 2023) into a cohesive BM. According to the owners’ estimation, the site hosts roughly 90,000 guests annually, drawing both domestic families and international visitors interested in a sustainable food experience and cultural heritage. The business employs 105 staff members (according to the latest data from NCB) across diverse roles, supporting rural employment and strengthening local capacities. Among the suppliers, 70% are from local farmers. It also gives support to local entrepreneurs through knowledge sharing and promotion through its own channels.

Aligned with the Slow Food Alliance, the business prioritizes local diversity, seasonality, and fair trade, using artisanal methods to produce its products.

The business is rooted in the legacy of a well-known national figure (Gjergj Fishta), whose work inspired the name Mrizi Zanave, referencing the mythical “noon of the fairies,” creating a strong narrative connection to local identity (Angelucci, 2023). During COVID-19 lockdowns, the business demonstrated adaptive capacity by repurposing staff to help local farmers and initiating direct delivery of farm products to urban customers, mainly in the capital, where 32% of the Albanian population is situated (INSTAT, 2023), ensuring this way community support and organizational survival.

Mrizi Zanave represents a holistic and replicable model (as discussed forward) of sustainable agrotourism. Its unique system of agri-hospitality reflects the interconnected sustainability dimensions central to TLBMC.

To obtain financial data, we utilized data extracted by NCB (historical data) and analyzed the business growth rate over the last 5 years (2020–2024). As shown in Table 1, even if the period includes the COVID-19 period (movement was almost stopped for 1 year and limited for another year), the enterprise adapted very well to the new situation. The financial data show a steady growth over the years. We have analyzed annual turnover, net profit, and long-term assets as key financial indicators to assess the business’s progress. On the booking platform, we have also analyzed the feedback of the customers. Table 2 presents the thematic analysis of customer reviews for a one-month period. The business has data from August 30, 2022, and has a total of 2297 reviews, with an excellent evaluation of 9.5 points. Going through all reviews, it has only 33 reviews with less than 6 points for the entire period (2022–2025).

Table 1. Growth rate of the business “Mrizi i Zanave” for 2020–2024 data extracted from National Business Center Albania database on National Business Center, AL

Table 2. Thematic analysis of Booking.com reviews for Mrizi Zanave (August 2025) data extracted from booking platform on Booking.com Mrizi Zanave reviews.

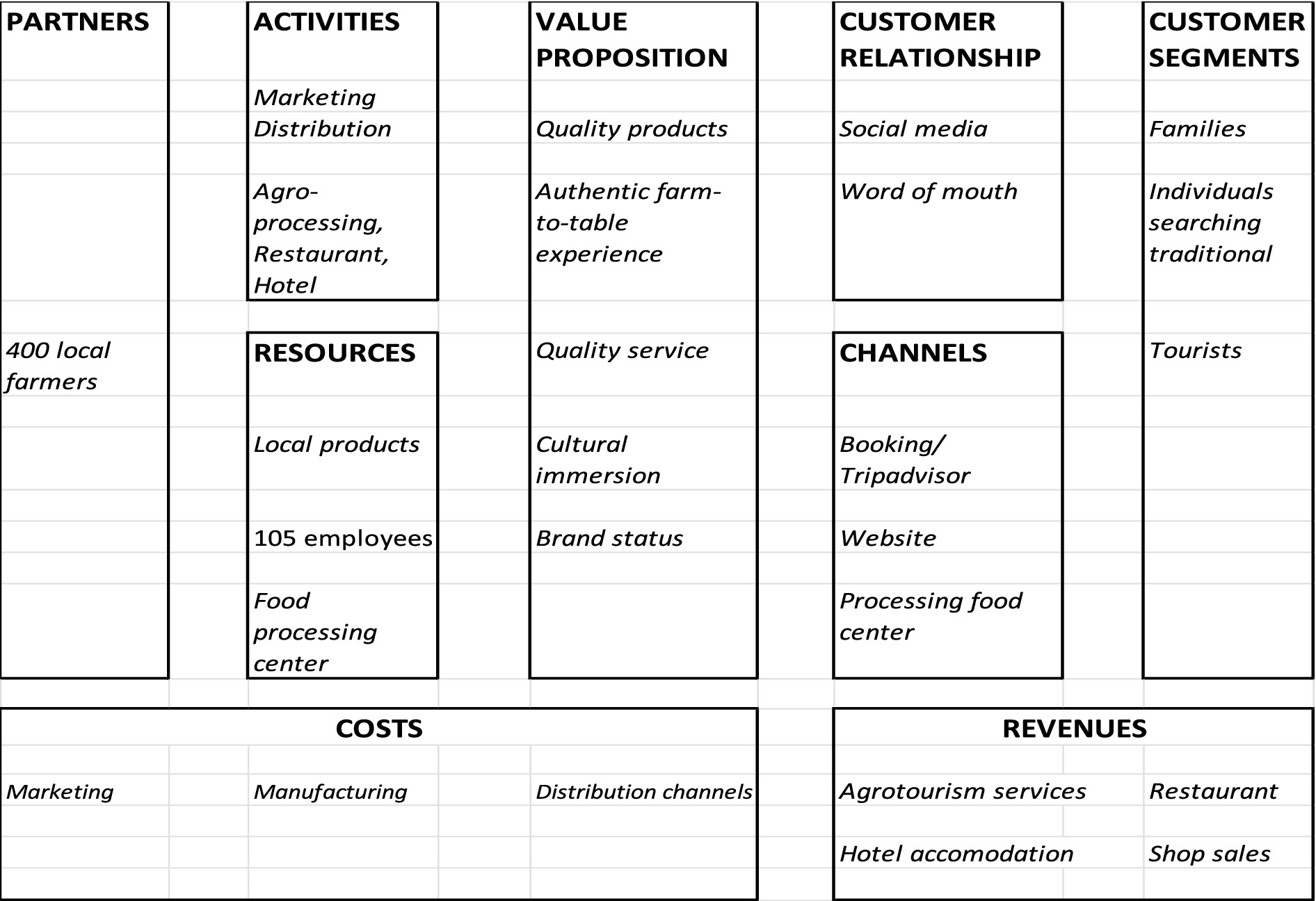

Going to the TLBMC, the economic layer of “Mrizi i Zanave” (Figure 1) highlights the traditional components of the business model, completed using NBC open-data financial statements (2019–2024), Booking.com reviews, and interviews. Partners include 400 local farmers. Key activities involve marketing, agro-processing, restaurants, hotels, and distribution. Resources comprise the 105 employees (data taken from the financial documents for 2024 delivered on the NBC database) and the food processing center. The value proposition is presented as an authentic farm-to-table experience with high-quality products and services. Customer segments are families, tourists, and individuals seeking cultural authenticity. Channels include the restaurant, farm shop, website, Booking.com, and TripAdvisor. Revenues stem from restaurant, accommodation, and product sales, while costs are related to manufacturing, marketing, and distribution.

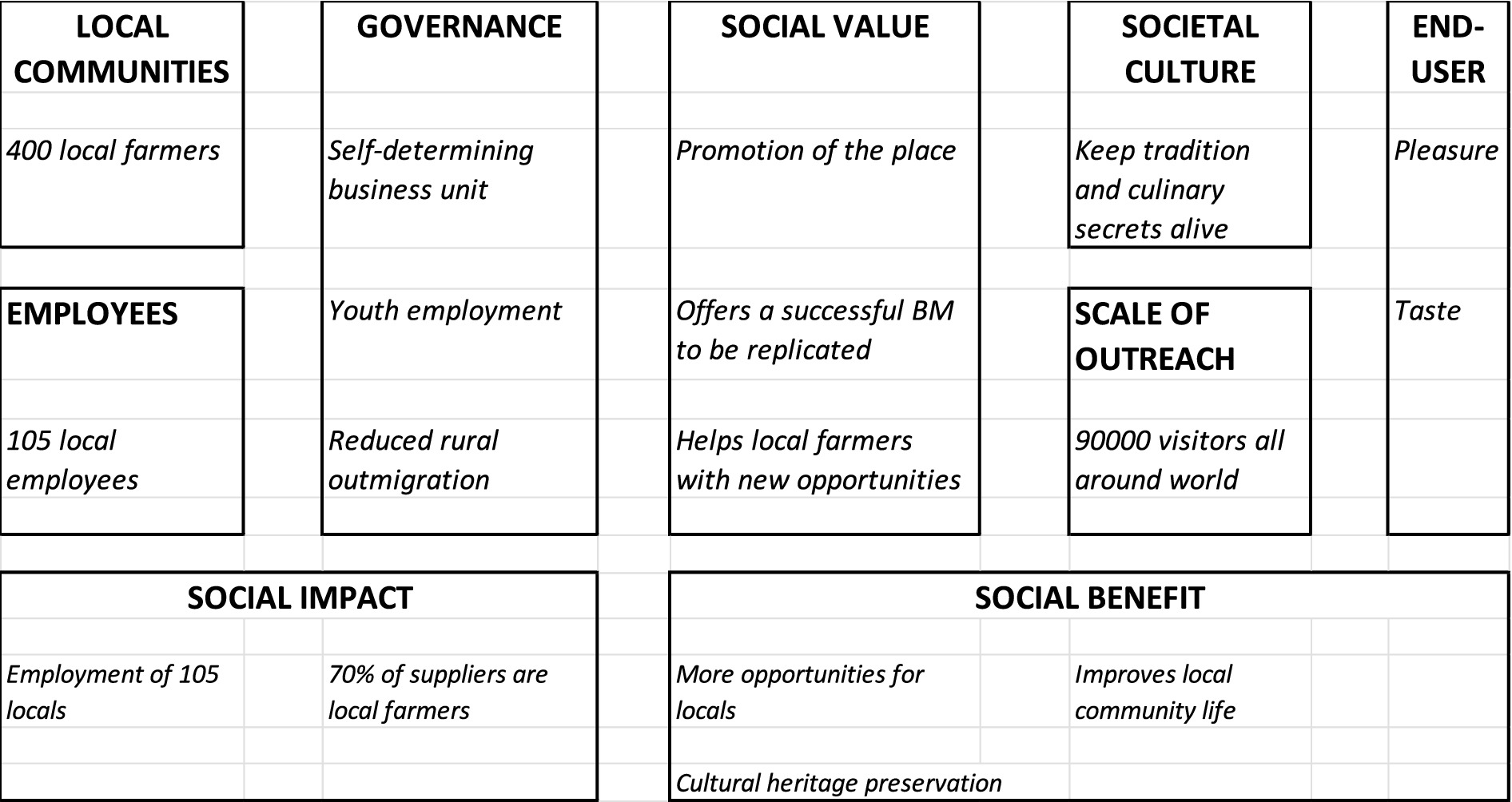

The Social Layer (Figure 2) emphasizes how the enterprise creates and distributes social value. Information was derived mainly from the interviews and customer reviews. Governance reflects a self-determining business unit anchored in the local community. Social value propositions encompass the preservation of culinary traditions, cultural promotion, and the creation of opportunities for local farmers. The business had a great influence in revitalizing the area. Outreach is evidenced by 90,000 visitors worldwide and a strong word-of-mouth reputation. Social impact includes the creation of 105 jobs, reliance on 70% local suppliers (both data taken from the NBC database), and the improvement of local community life. The business has a rating of 9.5/10 on Booking.com and a rating of 9.6/10 for staff. Risks such as potential dependency on farmers for the enterprise were acknowledged.

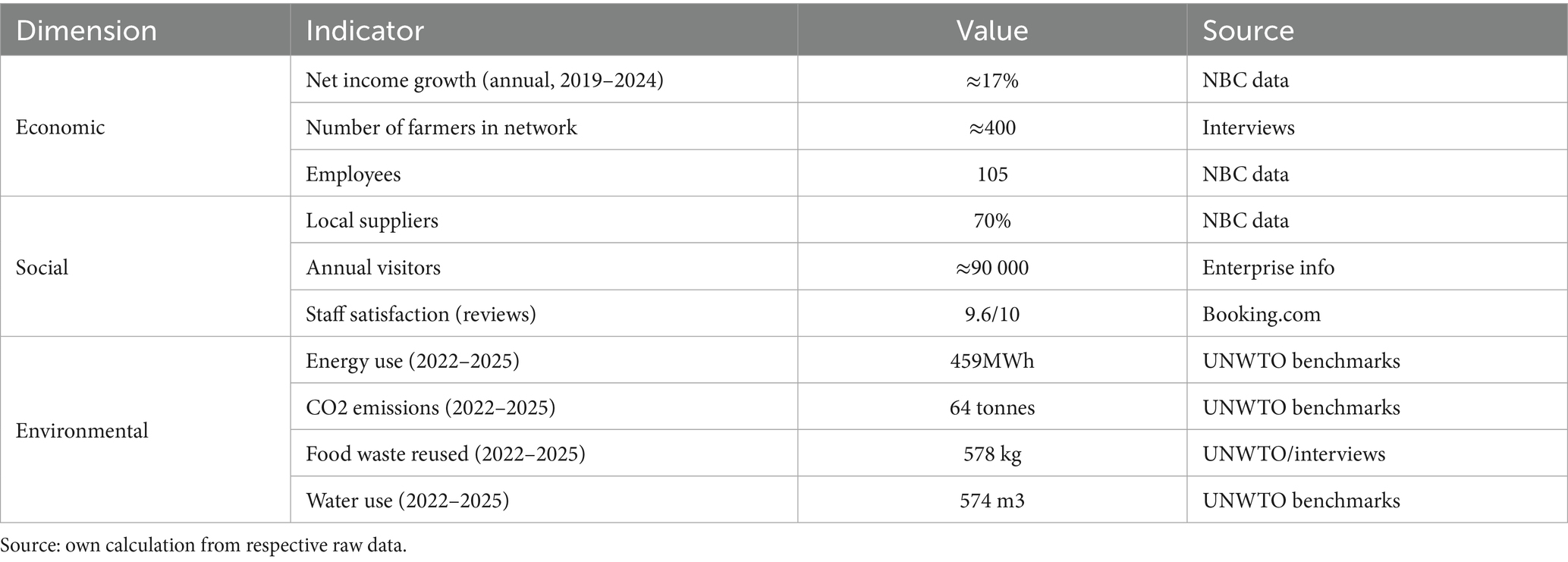

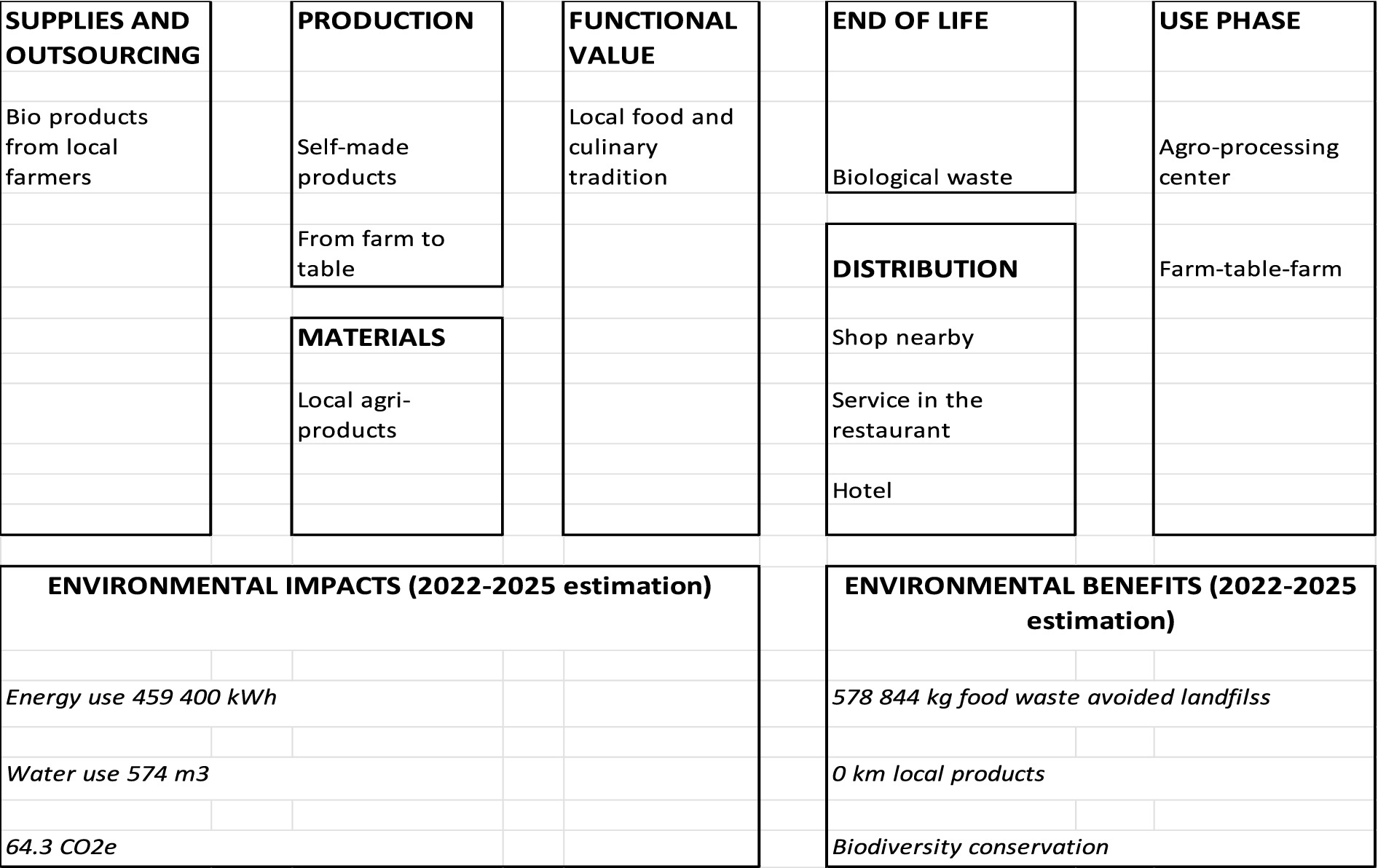

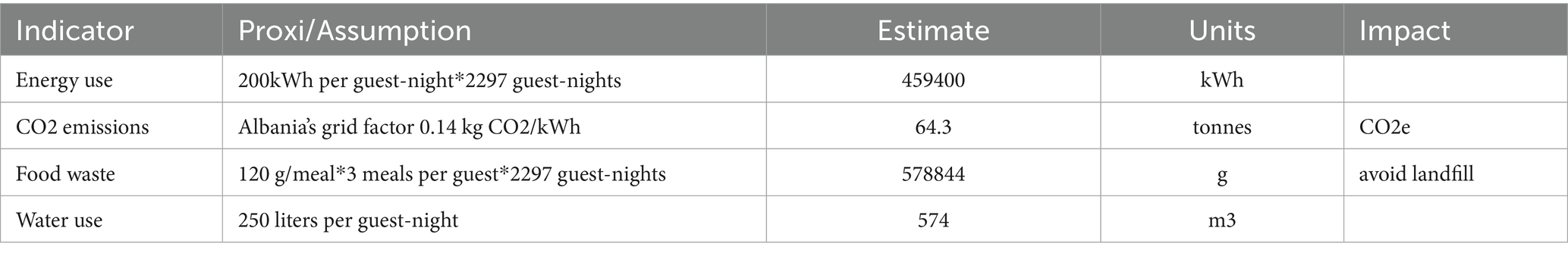

The Environmental Layer (Figure 3) captures value related to natural resources, production, and ecological impacts. Data taken from proxy-based calculations (energy use, food waste, and water consumption) using international benchmarks (World Tourism Organization, 2022; Nicolae, 2017) were complemented by interview insights. Calculations (on Table 3) include the period of 2022–2025, and they are based only on the data taken from Booking.com. It means that they exclude customers who used just the restaurant and those who did not write any review. Energy use per guest-night was calculated using WUNWTO benchmarks, adjusted for Albania’s predominantly hydropower electricity grid, yielding a relatively low footprint of approximately 64 tonnes CO2e over the 3 years. Food waste was estimated as 826 kg, of which 70% is reused through composting and animal feeding (551 kg avoided landfills), illustrating the business’s circular economy practices. Water use was approximated at 574 m3, a modest level of resource consumption in line with the scale of operations. Even if the data are partial, the results provide indicative insights into Mrizi Zanave’s environmental profile.

Figure 3. Triple Layered Business Model Canvas, environmental layer business model canvas Mrizi Zanave.

Table 3. Proxy based environmental indicators for Mrizi i Zanave (2022–2025) reference UN Tourism on UN Tourism

All the data about the layers of the business model are summarized in Table 4.

4 Discussion

The interviews provided in-depth insights into how owners/managers perceive the business’s evolution and contribution to the local community. They emphasized the business’s role in reviving rural traditions, having a BM that is replicated in other similar businesses in similar contexts, creating employment opportunities and a market for the local produce, and promoting sustainable gastronomy. The interviews highlighted adoption strategies during the COVID period, as well as strategic and long-term dimensions such as community empowerment, ecological sustainability, and the transfer of know-how to younger generations. The information on financial data confirmed the steady growth of the business over the years. Furthermore, the analysis of reviews demonstrates the value of user-generated content as a complementary source of evidence in tourism research. Online reviews provide unsolicited, spontaneous feedback that captures guests’ perceptions in real time. Thus, the integration of these sources through triangulation (Denzin, 2017) reduces the potential bias of relying on a single data type and allows for a multiple-perspective understanding of “Mrizi i Zanave.”

Analyzing the economic layer (Figure 1) of the TLBMC for the agrotourism business “Mrizi i Zanave” in Albania offers a valuable perspective on how sustainable and circular value creation can be embedded in core business functions. The economic layer of the TLBMC corresponds closely to the classic BM canvas (Osterwalder et al., 2010), focusing on elements such as value proposition, customer segments, revenue streams, and key partnerships, as in the following:

Key partnerships: Mrizi i Zanave collaborates with over 400 local farmers, forming the backbone of its agrifood supply chain. This network facilitates a short supply chain, ensuring authenticity and quality while stimulating the rural economy. The business also engages the local community as employees and informal partners. These relationships represent horizontal cooperation, which supports regional development and creates shared value. But on the other hand, this non-institutionalized relationship with local farmers (common in Albania’s small farm-dominated landscape) creates limited scalability and a lack of quality control mechanisms.

Key activities: The key economic activities include marketing, agro-food production, and agro-tourism services. Marketing leverages digital platforms (social media, TripAdvisor, and Booking.com), enhancing the visibility of the business to both domestic and international visitors. Other activities include running the food processing center, supporting on-site production of traditional food, ensuring value capture within the region, and differentiating its product offerings, which include food items and artisanal produce.

Value proposition: The BM is explicitly territorial, as it uses agrotourism to revalorize a historically marginalized area (Fishte, once a site of repression under communist dictatorship). Business functions as a catalyst for regional development by restoring social, cultural, and economic vibrancy. This was the business that offered a multi-dimensional value proposition: high-quality locally sourced food, authentic culinary experiences tied to Albanian tradition, employment and capacity-building for the local population, branding of tradition and place, and evaluation of regional identity through gastronomy. These aspects make “Mrizi i Zanave” not just a business but a place-based innovation hub rooted in food heritage and sustainability.

Customer segments: Our customers include Albanian families seeking traditional food experiences, domestic and international tourists interested in slow food and agritourism, as well as individuals motivated by cultural exploration and ethical consumption. This segmentation is inclusive and appeals to eco-conscious and experiential consumers.

Customer relationships and channels: The business fosters direct relationships with clients through social media and word-of-mouth marketing, both of which are effective in high-trust, experience-driven markets like agrotourism. Booking and feedback platforms (e.g., TripAdvisor, Booking.com) are leveraged to create reputational capital and extend the customer base globally, while also serving as a branding mechanism that associates the business with authenticity, locality, and ethical food tourism. The website serves as a gateway for storytelling, promotion, and direct reservations.

Key resources: The founder returned from Italy after 15 years, bringing back knowledge and capital. This repatriated know-how played a crucial role in establishing a hybrid model of tradition and innovation, making the case a strong example of diaspora-driven sustainable entrepreneurship. Furthermore, the key resources include local agricultural products, cultural knowledge, and culinary skills. A processing center for food production, a highly committed entrepreneurial team. This reflects an effective integration of tangible and intangible assets, building resilience through embeddedness in the local context.

Cost structure: Costs are associated with marketing and branding, manufacturing and processing, distribution, and logistics. While the use of local resources reduces procurement costs and carbon footprint, the business still incurs operational costs associated with quality assurance and logistics, especially in serving a growing tourist base.

Revenue streams: Revenue is generated from on-site restaurant and hotel services, sales of processed food and beverages, and cultural and gastronomic tourism experiences. The diversified income structure enhances financial sustainability and buffers against seasonality typical of rural tourism businesses.

Going on the social layer (Figure 2), Mrizi Zanave’s BM is deeply embedded in its local context (local communities and stakeholder inclusion), collaborating with over 400 smallholder farmers, positioning them as integral contributors to the value chain. This form of stakeholder empowerment builds local ownership and trust. The social inclusion of farmers not only provides them with economic opportunities but also re-establishes a sense of agency in a post-communist rural landscape. However, these relationships are informal, which raises questions about long-term resilience and dependency. An important aspect of the social layer concerns Mrizi Zanave’s response during the COVID-19 pandemic. According to interviews, the enterprise mobilized its employees (who are local), sending them to nearby villages to support farmers with planting and harvesting activities. Simultaneously, it employed its distribution and marketing networks to sell not only its products but also those of the surrounding farmers. This initiative not only safeguarded local employment but also strengthened social cohesion and mutual trust between business and the rural community. Given that approximately 70% of suppliers are local, it can be reasonably assumed that such growth was also reflected in the economic situation of local farmers. In this sense, the social impact extends beyond direct employment (105 staff members) to the creation of distributional benefits throughout the community.

Governance – Being a self-determining business unit, Mrizi Zanave operates with a level of autonomy and grassroots orientation. Decision-making seems to be centralized yet strongly informed by community interests. While the governance model is not formally participatory, the business’s consistent collaboration with local actors suggests an embedded governance approach that aligns with the principles of community-based entrepreneurship.

Social value creation – The business fosters the intergenerational transmission of knowledge, especially around food, crafts, and farming practices. Its emphasis on “keeping culinary secrets alive” illustrates a cultural valorization strategy, preserving intangible heritage while turning it into an economic asset. Mrizi Zanave’s social value lies in its role as a cultural intermediary, giving value to local traditions and translating them into meaningful experiences.

Societal culture & outreach – With over (estimated) 90,000 visitors from around the world, Mrizi Zanave has scaled its cultural outreach far beyond its regional borders. It positions rural Albania as a site of cultural authenticity and sustainable living. This societal impact is twofold: internally, as it enhances community pride and reduces rural outmigration, and externally, as it reshapes perception of Albania through the lens of sustainability and heritage. Such outreach contributes to soft diplomacy by improving the international image of marginalized territories.

End-users and user experience – Tourists and local visitors alike benefit from an experience that offers pleasure, authenticity, and taste with deep emotional and cultural resonance. The business does not just serve food; it tells a story of the place, memory, and resilience. This enhances the emotional engagement and social capital of the business.

Social impacts and benefits – While Mrizi Zanave (it) offers clear social benefits, including rural employment, entrepreneurial inspiration for others, and community cohesion, there are risks as well, particularly the potential dependency of farmers on the business’s purchasing decisions. This creates asymmetrical power dynamics, especially if no formal agreements support these relationships. Therefore, future scaling could consider formalizing these partnerships or introducing shared governance models to enhance equity and resilience.

Continuing the analysis, the environmental layer (Figure 3) of the TLBMC provides a structured analysis of Mrizi Zanave’s environmental interactions across its supply chain, production processes, and post-consumption impact. As a prominent agrotourism business rooted in the principles of localism and slow food, Mrizi Zanave employs several environmentally responsible practices that align with circular economy values.

Supplies and outsourcing – The business sources bio-products primarily from over 400 local farmers, ensuring low transportation emissions and supporting sustainable agricultural practices. This localized supply chain significantly reduces the business’s ecological footprint while strengthening rural livelihoods.

Production – The business emphasizes the “farm-to-table” model, using self-made products and traditional processing methods. Food preparation occurs on-site, employing low-intervention techniques that preserve natural flavors and minimize chemical inputs. This reflects an operational philosophy grounded in eco-efficiency.

Functional value and use phase: Mrizi Zanave generates value through the revival of local culinary traditions, which resonates with environmentally conscious consumers. The use phase involves the agro-processing center and dining facilities, creating a closed-loop “farm-to-farm” cycle. By reintegrating organic waste into farming activities, the business reduces landfill use and enhances soil health.

End-of-life – Biological waste is systematically handled through composting or reuse, contributing to a circular system. However, there is a need for clearer data on waste volumes and treatment efficiency, which could improve transparency and traceability.

Distribution – The environmental cost of distribution is minimized by operating mainly on-site consumption and selling through a nearby shop, thus avoiding energy-intensive logistics. However, the popularity of the site has increased private traffic, resulting in minor air and noise pollution, an externality that is not currently mitigated by sustainable transport initiatives.

Environmental impacts and benefits – The proxy-based estimates suggest that Mrizi Zanave operates with a relatively light environmental footprint (64 tonnes CO2e). The predominance of renewable energy in Albania’s electricity mix significantly reduces carbon intensity. Regarding food waste, at least 578 kg of food waste is avoided in landfills. Importantly, relying on local suppliers not only strengthens the social dimension but also reduces food kilometers, further lowering emissions.

Although based on secondary benchmarking rather than direct monitoring, these estimates add credibility to the claim that Mrizi Zanave’s BM integrates environmental responsibility alongside economic success and social embeddedness.

5 Conclusion

Designing business models for sustainability requires a blend of strategic insight, contextual sensitivity, and stakeholder engagement. Successful (Teece, 2010) BM design demands a nuanced understanding of value creation, delivery, and capture, anchored in customer, competitor, and partner ecosystems. This paper contributes to the growing literature on sustainable and circular BMs by applying the TLBMC to the case of Mrizi Zanave, a pioneering agrotourism business in North Albania. The model gives the possibility to link local gastronomy with rural livelihoods and regional branding, aligned with place-based entrepreneurship (João et al., 2025).

The interview data show the business’s situation in detail. While the NBC financial data confirms steady economic growth between 2019 and 2024 (even during the COVID-19 years), interviews provide evidence of how this growth is anchored in community-oriented practices, and online reviews attest to the visitor satisfaction that underpins financial success.

The findings from the analysis of model layers illustrate how Mrizi Zanave integrates economic, social, and environmental value creation through embedded local networks, circular food systems, and place-based branding rooted in cultural heritage. The business has played a transformative role in revitalizing a region historically shaped by socio-political trauma (Lubonja, 2021), fostering a regenerative narrative of sustainable entrepreneurship that is deeply rooted in regional identity and food traditions (Mutanga and Chikuta, 2025). Through informal but impactful collaborations with over 400 local farmers, the enterprise exemplifies a decentralized value chain that sustains livelihoods and preserves traditional knowledge. As per the latest financial data (explained) for the year 2024, the business has 105 employees (they are all from the local community), and 70% of the suppliers are local farmers, which shows that the business embeds itself deeply into the socio-economic fabric of the region. Researchers (Dionizi and Kercini, 2025) argued that agrotourism-based BMs offer viable pathways to achieving the SDGs while enhancing local resilience.

Applying the TLBMC framework has proven particularly valuable in this context. It enabled a multidimensional analysis of how value is created, delivered, and captured across three interconnected layers: economic, social, and environmental. In this regard, the TLBMC functioned both as a diagnostic and storytelling tool, supporting reflective business practice and offering visual clarity on sustainability-oriented trade-offs and synergies (Joyce and Paquin, 2016) in the Western Balkans context (Rexhepi Mahmutaj et al., 2025). However, the study also revealed notable gaps. The lack of structured metrics to assess environmental and social performance, such as pollution from added traffic or the exact measurable socio-economic uplift of partnering farmers, points to the need for greater formalization and monitoring, as highlighted by Dionizi and Kerçini (2015).

5.1 Contributions and implications

This study makes several contributions. Conceptually, it extends the literature on BM innovation by demonstrating the practical applicability of the TLBMC in an emerging economy and post-socialist context. Empirically, it offers a rich, place-based case study of sustainable entrepreneurship in Albania, adding to the limited body of research on agrotourism and circular BMs in the Western Balkans. Methodologically, this study employs a qualitative, interpretive approach that combines semi-structured interviews and desk research with model-driven analysis, informing similar inquiries in comparable regional contexts.

For practitioners, the study illustrates how integrating circular practices with heritage-based entrepreneurship can yield systematic benefits at the community level. The TLBMC can also be a strong tool for long-term planning when companies want to innovate their BM. For policymakers, it underlines the need to support data infrastructures, environmental monitoring, and SME formalization to enable the scaling of such models. For researchers, it demonstrates the analytical utility of the TLBMC and its potential to support storytelling, stakeholders’ engagement, and sustainability reflection.

5.2 Limitations and future research

Several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the study is based on a single case study, which limits the generalizability of the findings. Second, the data is largely qualitative, and the absence of quantitative measures on environmental and social impacts constrains a full sustainability assessment. Third, the informal structure of supplier relations, a common feature in Albanian agribusiness (Dionizi and Kerçini, 2015), poses methodological challenges in tracking systematic outcomes.

Future research should aim to complement qualitative insights with quantitative indicators, particularly for environmental metrics (official data on energy use, emissions, waste reduction) and social impact (e.g., income improvements, health outcomes). Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment (LCSA) or other tools may be used to quantify data for the case.

Comparative case studies across different regions or sectors also enrich our understanding of how the TLBMC adapts to varying institutional and cultural contexts. Moreover, exploring the integration of system thinking and digital tools with the TLBMC could offer new opportunities for dynamic sustainability assessment and circular transition planning.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The patients/participants provided written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

BD: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. RD: Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of University of Shkoder “Luigj Gurakuqi” in enabling the publication of this article. Sincere thanks are also extended to the reviewers for their constructive feedback and valuable suggestions, which significantly improved the quality of the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Generative AI (ChatGPT, developed by OpenAI) was employed solely to enhance the clarity, grammar, and academic tone of the manuscript. No part of the content (ideas, data analysis, or conclusions) was generated by AI. All research design, data collection, interpretation, and authorship remain the original work of the authors. The use of AI was limited to language refinement to support readability and professionalism of the final text.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frsus.2025.1665635/full#supplementary-material

References

Akomea-Frimpong, I., Tetteh, P. A., Addo Ofori, J. N., Ofori, J. N. A., Tumpa, R. J., Pariafsai, F., et al. (2024). A bibliometric review of barriers to circular economy implementation in solid waste management. Discover Environment 2:20. doi: 10.1007/s44274-024-00050-4

Angelucci, G. (2023). “The Albanian Chef Who Turned an Agriturismo into a Global Destination: ‘This Is How I Support My Land.’ Altin Prenga Shares His Story.” Available online at: https://reportergourmet.com/en/news/6017-altin-prenga-the-albanian-chef-who-made-his-agriturismo-a-global-icon.

Baden-Fuller, C., and Haefliger, S. (2013). Business models and technological innovation. Long Range Plan. 46, 419–426. doi: 10.1016/j.lrp.2013.08.023

Baden-Fuller, C., and Morgan, M. S. (2010). Business models as models. Long Range Plan. 43, 156–171. doi: 10.1016/j.lrp.2010.02.005

Barjak, Franz, Bill, Marc, and Perrett, Pieter Jan (2014) Paving the Way for a New Composite Indicator on Business Model Innovations Available online at: http://hdl.handle.net/11654/9987

Bocken, N., Miller, K., and Evans, S. (2016). Assessing the environmental impact of new circular business models. Available online at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/305264490_Assessing_the_environmental_impact_of_new_Circular_business_models

Booking. (n.d.) “Mrizi i Zanave Agroturizëm, Lezhë, Albania. Accessed September 6, 2025. Available online at: https://www.booking.com/hotel/al/mrizi-i-zanave-agroturizem.en-gb.html.

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Buriro, A., Awan, J., and Lanjwani, A. (2017). Interview: a research instrument for social science researchers. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Humanities Educ. 1, 1–14.

Chaves, R., and Raufflet, E. (2020). Circular economy, organizations, and business models: a literature review. Acad. Manage. Proc. 2020:17143. doi: 10.5465/AMBPP.2020.17143abstract

Clausen, A. (2012). The individually focused interview: methodological quality without transcription of audio recordings. Qual. Rep. 17, 1–17. doi: 10.46743/2160-3715/2012.1774

De Angelis, R. (2022). Circular economy business models as resilient complex adaptive systems. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 31, 2245–2255. doi: 10.1002/bse.3019

Denzin, N. K. (2017). The research act: A theoretical introduction to sociological methods. New York: Routledge.

Dionizi, Brikene, and Kerçini, Donika. (2015). Thinking strategically in agribusiness, case of Albania.

Dionizi, B., and Kercini, D. (2025). Sustainable business models in agritourism: an opportunity for achieving SDGS and circular economy. J. Lifestyle SDGs Rev. 5:e03957. doi: 10.47172/2965-730X.SDGsReview.v5.n01.pe03957

Doz, Y. L., and Kosonen, M. (2010). Embedding strategic agility: a leadership agenda for accelerating business model renewal. Long Range Plan. 43, 370–382. doi: 10.1016/j.lrp.2009.07.006

Elm, Mike. (2020). “Think Global, Eat Local – Mrizi I Zanave, Albania.” Available online at: https://newstoryride.wordpress.com/2020/11/20/think-global-eat-local-mrizi-i-zanave-albania/.

Gassmann, Oliver, Frankenberger, Karolin, and Csik, Michaela (2013) The St.Gallen Business Model Navigator Available online at: https://www.alexandria.unisg.ch/handle/20.500.14171/90052

Giesen, E., Riddleberger, E., Christner, R., and Bell, R. (2010). When and how to innovate your business model. Strateg. Leadersh. 38, 17–26. doi: 10.1108/10878571011059700

Hassan, H., and Faggian, R. (2023). System thinking approaches for circular economy: enabling inclusive, synergistic, and eco-effective pathways for sustainable development. Front. Sustain. 4, 1–8. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2023.1267282

INSTAT (2023) “Population Albania 2023.” Available online at: https://www.instat.gov.al/al/temat/treguesit-demografik%C3%AB-dhe-social%C3%AB/popullsia/#tab2

INSTAT. (2024). “Business Registers.” Available online at: https://www.instat.gov.al/en/themes/industry-trade-and-services/business-registers/.

Jha, S., Nanda, S., Zapata, O., Acharya, B., and Dalai, A. K. (2024). A review of systems thinking perspectives on sustainability in bioresource waste management and circular economy. Sustainability 16:23. doi: 10.3390/su162310157

João, I. M., Alves, N. M. H., and Silva, J. M. (2025). Motivations, barriers, drivers, and benefits of circular economy in EMAS and ISO 14001-certified companies. Circ. Econ. Sustain. doi: 10.1007/s43615-025-00635-y

Joyce, A., and Paquin, R. L. (2016). The triple layered business model canvas: a tool to design more sustainable business models. J. Clean. Prod. 135, 1474–1486. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.06.067

Kropfeld, Maren, and Reichel, André. The value of “enough” – Sufficiency-based consumer practices and value creation in business models. (2019).

Latour, B. (2005). Reassembling the social: An introduction to actor-network-theory. Oxford: OUP Oxford.

Lecocq, X., and Demil, B. (2010). Business models as a research program in strategic management: an appraisal based on Lakatos. M@n@gement 13, 214–225. doi: 10.3917/mana.134.0214

Lewandowski, M. (2016). Designing the business models for circular economy—towards the conceptual framework. Sustainability 8:1. doi: 10.3390/su8010043

Lozano, R., Barreiro-Gen, M., and Zafar, A. (2021). Collaboration for organizational sustainability limits to growth: developing a factors, benefits, and challenges framework. Sustain. Dev. 29, 728–737. doi: 10.1002/sd.2170

Lubonja, Liri. (2021). “Larg dhe mes njerëzve, Liri Lubonja.” Available online at: https://www.shtepiaelibrit.com/store/sq/letersia-shqiptare/9213-larg-dhe-mes-njerezve-liri-lubonja-9789951613309.html.

Mason, K., and Spring, M. (2011). The sites and practices of business models. Ind. Mark. Manag. 40, 1032–1041. doi: 10.1016/j.indmarman.2011.06.032

Mrizi, Zanave. (n.d.) “Mrizi i Zanave Agroturizem.” Accessed September 6, 2025. Available online at: https://www.mrizizanave.al/.

Muller, D. P., Holzner, M., and Zurn, S. G. (2025). A systems thinking based sustainable business model framework –an appropriate approach for the design of sustainable business models in start-up consulting. Int. Bus. Res. 18:54. doi: 10.5539/ibr.v18n1p54

Mutanga, C. N., and Chikuta, O. (2025). Editorial: Agritourism and local development: innovations, collaborations, and sustainable growth. Frontiers in Sustainable Tourism 4, 1–3. doi: 10.3389/frsut.2025.1576829

National Business Center, AL. (n.d.) “Kërko Për Subjekt – QKB.” Accessed September 6, 2025. Available online at: https://qkb.gov.al/site/index.php/kerko-per-subjekt/.

Nicolae, Paul. (2017). Indicators of Sustainable Development for Tourism Destinations A Guide Book by UNWTO. Available online at: https://www.academia.edu/30852110/Indicators_of_Sustainable_Development_for_Tourism_Destinations_A_Guide_Book_by_UNWTO.

Osterwalder, Alexander. (2004). The Business Model Ontology – A Proposition in a Design Science Approach

Osterwalder, A., Pigneur, Y., and Tucci, C. (2010). Clarifying business models: origins, present, and future of the concept. Communications of AIS 16, 1–28. doi: 10.17705/1CAIS.01601

Pieroni, M., McAloone, T., and Pigosso, D. (2019). Business model innovation for circular economy: integrating literature and practice into a conceptual process model. Proc. Design Soc. 1, 2517–2526. doi: 10.1017/dsi.2019.258

Pigneur, Yves, Joyce, Alexandre, and Paquin, Raymond. (2015). The triple layered business model canvas: A tool to design more sustainable business models. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.06.067

Pokorná, J., Pilař, L., Balcarová, T., and Sergeeva, I. (2015). Value proposition canvas: identification of pains, gains and customer jobs at farmers’ markets. AGRIS On-Line Papers in Econ. Inform. VII, 123–130. doi: 10.22004/ag.econ.231899

Rexhepi Mahmutaj, L., Jusufi, N., Krasniqi, B., Mazrekaj, L., and Krasniqi, T. (2025). Barriers to transitioning to circular economy within firms in Western Balkans countries. Front. Sustain. 6, 1–12. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2025.1546110

Santa-Maria, T., Vermeulen, W. J. V., and Baumgartner, R. J. (2022). The circular sprint: circular business model innovation through design thinking. J. Clean. Prod. 362:132323. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.132323

Savitz, A. (2013). The triple bottom line: How today’s best-run companies are achieving economic, social and environmental success - and how you can too, revised and updated. New Jersey: Wiley : Wiley.Com.

Sherifi, Nisa. (2023). “Lost in Translation: True Sustainability and Enchantment at ‘Mrizi i Zanave’ Agrotourism.”Available online at: https://europeandme.eu/lost-in-translation-true-sustainability-and-enchantment-at-mrizi-i-zanave-agrotourism/.

“Slow food heroes and Mrizi i Zanave: The Agritourism that takes Care of the Land and People.” (2021). Slow Food, Available online at: https://www.slowfood.com/blog-and-news/slow-food-heroes-and-mrizi-i-zanave-the-agritourism-that-takes-care-of-the-land-and-people/.

Teece, D. J. (2010). Business models, business strategy and innovation. Long Range Plan. Bus. Models 43, 172–194. doi: 10.1016/j.lrp.2009.07.003

Teece, D. J. (2018). Business models and dynamic capabilities. Long Range Plan. 51, 40–49. doi: 10.1016/j.lrp.2017.06.007

TripAdvisor. (n.d.) “Mrizi i Zanave Agroturizem Restaurant: Pictures & Reviews.” Accessed September 6, 2025. Available online at: https://www.tripadvisor.com/Hotel_Feature-g19261519-d17562889-zft9165-Mrizi_i_Zanave_Agroturizem.html.

World Tourism Organization (Ed.) (2022). Measuring the sustainability of tourism – Learning from pilots. Madrid: UNWTO.

Keywords: sustainable business models, Triple Layered Business Model Canvas (TLBMC), agrotourism, circular economy, Western Balkans, emerging economies, place-based entrepreneurship

Citation: Dionizi B and Dhora R (2025) Reinventing rural economies through sustainable business models: a triple-layered analysis. Front. Sustain. 6:1665635. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2025.1665635

Edited by:

Ioannis Kostakis, Harokopio University, GreeceReviewed by:

Gandhi Pawitan, Parahyangan Catholic University, IndonesiaAbdullah Haidar, Tazkia University, Indonesia

Copyright © 2025 Dionizi and Dhora. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Brikene Dionizi, YnJpa2VuZS5kaW9uaXppQHVuaXNoay5lZHUuYWw=

†ORCID: Romina Dhora, orcid.org/0000-0002-1431-3871

Brikene Dionizi, orcid.org/0000-0002-6832-7072

Brikene Dionizi

Brikene Dionizi Romina Dhora

Romina Dhora