- 1Sociology Department, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden

- 2Pebl Feedback C.I.C., Colchester, UK

- 3Department of Anthropology, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, Netherlands

Medical sociology has a poor track record of researching diversity in theoretically innovative ways. This paper notes usage of the term superdiversity in migration and urban studies, to ask about its utility in general and more specifically for researching the social production of health and illness. Referring to a multi-country interview study about healthcare seeking strategies, the need to understand the diversification of diversity and the challenges for multi-method health research are described. Six interviews each were conducted in Germany, Spain, Sweden, and the UK, to give a diversity sample of 24 adults who described their strategies and practice when seeking healthcare. In discussing how far superdiversity can help to model socioeconomic and cultural changes already identified as challenging health policy and service provision, the paper draws on case study material. The complex intersecting dimensions of population diversity to which superdiversity draws attention are undoubtedly relevant for commissioning and improving healthcare and research as well as policy. Whether models that reflect the complexity indicated by qualitative research can be envisaged in a timely fashion for quantitative research and questions of policy, commissioning, and research are key questions for superdiversity’s ongoing usefulness as a concept.

Introduction

British Medical Sociology was castigated in its own newsletter for racism (Ahmad, 1992). Using the metaphor of an ostrich with its head in the sand, a community of scholars was accused, in no uncertain terms, of ignoring Black and minority ethnic issues in the social production of health and illness and thereby perpetuating oppressive structures and practices. In response, the then editor of the journal Sociology of Health and Illness described the small number of papers received on the topic of “race” and pointed to the invisibility of “race” in official data sets (Blaxter, 1992). In retrospect, this was part of the shift in terminology and research categories, which, as Ahmad suggested back in the early 1990s, the sociology of health and illness was particularly slow to take up, when compared with other social sciences. Despite honorable exceptions, it is still the case that in general sociology tends to leave questions of racialization, ethnicity, and difference to other disciplines (Bhambra, 2014), and medical sociology follows this trend. Furthermore, medical sociology’s affiliations with public health and social epidemiology can mean an unreflective use of existing official categorizations, for various socially constructed concepts, such as age, gender, class, ethnic group, and migration status. Ethnic census classifications have been adopted as a routine healthcare variable in the UK although the quality of the data is generally thought to be poor. Such data are contested not only for failing to capture identity appropriately and for being incomplete but also for being an inflexible means of tracking ongoing population changes and so being of limited use in planning and developing responsive healthcare practices. In this paper, we ask whether medical sociology has been too slow to notice new descriptions of diversity that might make sense of dilemmas in the experience and provision of healthcare.

In some scholarly and policy oriented research circles, the term superdiversity has become an accepted shorthand to describe the twenty-first century nature of what used to be called multicultural or multiethnic society. Initially coined to describe population changes in the south east of England, particularly London (Vertovec, 2007), the term has found global resonance (Berg and Sigona, 2013; Meissner and Vertovec, 2014). The idea of superdiversity has been picked up across a range of scholarly disciplines (Blommaert, 2013; De Bock, 2015), public policy (Fanshawe and Sriskandarajah, 2010; Phillimore, 2011; Aspinall, 2012), and political discourse (Muir, 2015; Ratcliffe, 2015) to call attention to a set of changes that are demographic, economic, and social and to index an increase in the speed, spread, and scale of migration. Our own research has highlighted that “superdiversity has the potential to throw new light on how healthcare is sought and negotiated, particularly in terms of the assistance provided by others” (Green et al., 2014, p. 1217). But the term superdiversity has not caught on in medical sociology.

In the early 1990s, when Ahmad was chiding medical sociology, the terminology of ethnicity seemed to offer the flexibility to apprehend the complex contingency of subjective and objective aspects of identity and structure that racialized terms could not (Bradby, 1995). Ethnic terminology and understandings of diversity have themselves suffered from racialization, promoted by the different meanings in American versus European settings, combined with a definitional vagueness in research and clinical writing (Bradby, 2003). Qualitative research which might employ subtle categorizations in its original language is subsequently published in English-language journals and translated into recognizable, shared Anglophone categories (Helberg-Proctor et al., 2016) which may reinscribe crude racialized divisions.

This paper examines the concept of superdiversity as proposed by Vertovec (2007) and developed by Meissner and Vertovec (2014) and asks what it might offer critical studies of illness, health, and healthcare. We draw case studies from our multi-country interview study of adults’ strategies for healthcare that demonstrated the complexity of diversity such that simple divisions between migrants and non-migrants or ethnic minority and majority have limited explanatory power (Green et al., 2014).

Superdiversity’s Origins

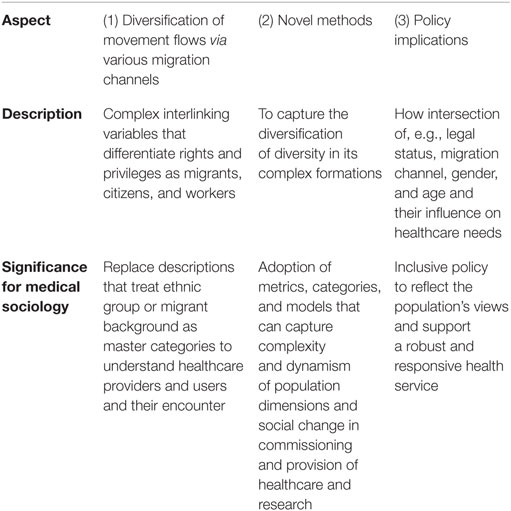

Vertovec elaborates his original formulation of superdiversity, to emphasize three interrelated aspects, summarized in Table 1.

(1) A description of the changing population configurations arising from global migration flows of the past several decades. Attention is drawn not only to the movement of people from an increasing range of national, ethnic, linguistic, and religious backgrounds but also to how such categories coincide with:

a worldwide diversification of movement flows through specific migration channels (such as work permit programmes, mobilities created by EU enlargement, ever-changing refugee and ‘mixed migration’ flows, undocumented movements, student migration, family reunion, and so on); the changing compositions of various migration channels themselves entail ongoing differentiations of legal statuses (conditions, rights and restrictions), diverging patterns of gender and age, and variance in migrants’ human capital (education, work skills and experience) (Meissner and Vertovec, 2014, p. 542).

The enormous complexity of the population of England and of London in particular (Vertovec, 2007) was illustrated with reference to:

net inflows, countries of origin, languages, religions, migration channels and immigration statuses, gender, age, space/place, and practices of transnationalism. In this respect superdiversity is proposed as a summary term to encapsulate a range of such changing variables and their interlinkages which amount to complexities that supersede previous patterns of migration-driven diversity (Meissner and Vertovec, 2014, p. 542).

Thus, superdiversity does not simply mean “more ethnic diversity” but draws attention to complex interlinking variables that differentiate people’s rights and privileges as migrants, citizens (including those who have not migrated and have no migrant forebears), and workers in novel ways.

(2) These complex new social formations imply the need for novel social scientific methods and theories that will supersede a focus on ethnic group.

(3) Finally, there is an underlining that practical policy-based implications of new social formations need to be studied, with greater attention to “for instance legal status and its articulation with migration channel, ethnicity and gender” (Meissner and Vertovec, 2014, p. 542).

Meissner and Vertovec ask whether scholars can describe a recognizable characteristic termed superdiversity in a range of settings and if so, whether it can be measured for comparative purposes. In so doing they point to the alliterative “spread, speed and scale” of diversified diversity and ask about connections with the “three P’s—power, politics and policy” (Meissner and Vertovec, 2014, p. 546).

Superdiversity is proposed to supersede a concept of diversity as a form of “multiculturalism” built around distinct “ethnic communities.” Put bluntly, migration scholars have noted that global migration patterns have changed from involving many migrants from and to few places to patterns involving fewer migrants from and to more places. So even if some versions of ethnicity have sometimes offered plural and multivalent meanings, the notion of ethnic communities does not work where migrant populations are extremely diverse, composed of small numbers and scattered geographically (Schierup et al., 2006). Berg and Sigona (2013) claim that the term superdiversity is increasingly used instead of multiculturalism and cite a report entitled “You can’t put me in a box” as evidence of the demise of ethnicity-inflected identity politics, at least in Britain (Fanshawe and Sriskandarajah, 2010).

Other advantages of the term superdiversity come from its derivation from migration studies, anthropology, and urban geography such that the spatial dimensions of the politics of difference are signaled (Berg and Sigona, 2013, p. 349). Various commentators have pointed to the parallels between the role of superdiversity in migration studies and the feminist model of “intersectionality” (Yuval-Davies, 2006), which might have parallels for how migrant studies should meet public health (Zeeb et al., 2015). While superdiversity is more closely focused on “nationality/country of origin/ethnicity, migration channel/legal status and age as well as gender” (Meissner and Vertovec, 2014, p. 545), intersectionality theories ask us to not take for granted when and how race, gender, and class become important, but rather to explore how they come to be articulated with one another. In this respect, intersectionality attends to the situational nature of categories of difference, while superdiversity describes multiple variables.

Vertovec (2016) has emphasized the need for new concepts and theories to get to grips with complex social formations that have continued to change, without our vocabulary and models having kept pace. The idea that current concepts and models are not adequate to the dynamic cultural context of European has been articulated for well over a decade:

A new imaginary of European belonging is needed … one that acknowledges cultural difference without assuming any order of worth based on ethnicity or religion, and one that is also able to forge a new commons based on values and principles that resonate across Europe’s diverse communities (Amin, 2004, p. 3).

The term superdiversity indicates the need for theoretical and methodological approaches that can cope with the changing complexities of populations encountered in healthcare settings. Medical sociology in the UK has committed to the language of ethnicity, reflecting the categories used in official data collection, but this is not true in all European settings (Stronks et al., 2009). Where ethnic categories are rejected as divisive, distinctions are made on the grounds of people’s “migrant or foreign background” which has an equally racializing and crudely dichotomous effect, the limitations of which are underlined by advocates of superdiversity. The need to appraise policy implications of superdiversity in populations of health service providers and users is urgent, particularly in the context of austerity-justified resource limitations restricting and withdrawing specialist provision for minorities (Phillimore, 2011, p. 21).

Below, we survey the way that superdiversity is being used in different research contexts in order to offer some suggestions as to whether it is useful for thinking through the role of diversity in the sociology of health, illness, and medicine. Our own analysis of interview material describing strategies around healthcare is cited for illustration of how superdiversity might work in qualitative research.

Superdiversity as a Feature of Cosmopolitan Urban Settings

Superdiversity characterizes urban diversity as

a multiplicity of ethnic minorities but also by differentiations in terms of migration histories, religions and educational and economic backgrounds, both among long-term residents and newcomers (Wessendorf, 2014, p. 393).

Crucially superdiversity implies a certain “civility towards diversity” because it is a “strategy to both engage with difference as well as avoid deeper contact” (Wessendorf, 2014, p. 393). Where multicultural models of diversity were engaged with overcoming conflict to promote integration, this vision of the microlevel interaction in superdiverse settings posits a resulting benign disinterest. The superdiverse context differs from a multicultural setting in that there is simply too much diversity to learn all the specificities such that “you cannot treat people differently according to their backgrounds because almost every-body comes from elsewhere” (Wessendorf, 2014, p. 397). Crucially, this “excess” of diversity becomes normal, and the civility that it provokes implies no particular appreciation or knowledge of diversity, but rather a certain indifference (Wessendorf, 2014). For European welfare settings, densely populated urban neighborhoods have a high level of diversity such that people cannot know or learn everyone’s background, and everyone in a single locality is accessing the same official services. A “relationship of mutual dependency” on crucial infrastructures, such as transport, education, and healthcare, is what characterizes a superdiverse neighborhood in the Global North (Blommaert, 2014, p. 448), as a context where polite, or at least neutral indifference to background can develop.

Without concepts that encapsulate new patterns of complex diversity, there is a risk of “missing the opportunities offered by superdiversity while only experiencing the costs of marginalizing new migrants” (Phillimore, 2011, p. 24). Identifying beneficial, constructive aspects of diversity arising from migration was an aspect of multicultural politics with, for instance, the validation of “migrant entrepreneurship.” Parallel claims about “new arrival enterprise” (Sepulveda et al., 2011) where new migrants successfully establish new business in already highly diverse settings have been made. Health and social care provision in European welfare states employ migrants, providing the impetus for intra- and international migration, with skilled medical professionals, as well as lower skilled cleaning, catering, and care staff all in demand (Connell, 2008). What role does the existence of the indifferent civility that Wessendorf identifies as characterizing superdiverse environments play in health and social care settings?

Negative Implications of Superdiversity

Negative aspects of labeling the diversification of diversity as superdiversity have been highlighted. On the grounds that “the realities of superdiversity” are unevenly distributed across Europe, being concentrated in a relatively small number of urban areas, there is little general interest for public policy (Sepulveda et al., 2011). Even if superdiversity is taken up in public policy, what work does it do? Neighborhoods that are altered by the arrival of new comers who render the societal conditions “unpredictable” can mean that superdiversity (in common with other terminology around diversity) becomes yet another mechanism for dividing us from them (Reyes, 2014). Along similar lines, the notion of superdiversity is criticized as reinforcing the same ideas that it purports to question and challenge, that is, “the tendency to homogenize cultural and social groups, and the uncritical embrace of elitist neoliberal conceptualizations of culture and identity” (Ndhlovu, 2016).

The claim that superdiversity has something to offer in making sense of the challenges that migration, mobility, and public service provision hinges on the diagnosis of an era of “transformative diversification of diversity” (Vertovec, 2007) which has rendered the notion of ethnicity analytically useless. However, it is possible that superdiversity will become just another way of referring to a racialized other, with essentialist connotations, as has already happened to the terminology of ethnicity and culture via the so-called “new racism.” Whether the concept superdiversity becomes a useful description of the political dynamics of citizenship to inform public service provision hinges on the degree to which “people—experts, legislators, opinion makers—are capable of imagining the levels of complexity that characterize the real social environments in which people integrate” (Blommaert, 2013, p. 195). The difficulty of imagining complexity, and of encapsulating it in research design, is a significant potential stumbling block.

Healthcare Settings

Superdiversity has been used to research linguistic (Blommaert, 2014) and convivial aspects (Wessendorf, 2014) of everyday spontaneous interactions as well as being applied to business enterprise (Sepulveda et al., 2011) and identity (Fanshawe and Sriskandarajah, 2010). It has not been used in the study of health and healthcare (Zeeb et al., 2015) although there is undoubtedly a need for “greater recognition of multi-variable migration configurations that underpins the concept of superdiversity” (Meissner and Vertovec, 2014, p. 545) in the encounter between the complex and mobile populations of health professionals and of health service users. Specifically superdiversity indexes how the complexity of populations’ rights and entitlements to healthcare raises profound challenges for healthcare provision, especially around consultation, needs assessment and assessing effective service provision across the range of population variables (Phillimore, 2011). Where planning for healthcare has been predicated on ethnic group data such complexity is simply not being captured (Aspinall, 2012).

Alongside the reasons why the diversification of diversity is relevant to studies of healthcare are conditions that make the analyses of aspects of globalized movements of people particularly problematic. The nation state is the territorial unit within which healthcare is planned in terms of funding, provision, and uptake and while transnational patient (Glinos et al., 2010) and despite increasing widespread professional mobility (Hörbst and Gerrits, 2016), people would nonetheless prefer to access care locally (Migge and Gilmartin, 2011). The nation state’s healthcare provision is directed at residents within its borders, and the system is designed for relatively immobile patients who stay within a given locality. When it comes to coping with diversity, ethnic approaches have depended on people with similar language needs or cultural preferences being concentrated in urban locations such that specialist services can be provided. As a larger number of languages and cultures are more widely dispersed within a health system this ethnic-group focused approach breaks down. It is no longer possible to provide staff who speak the larger number of languages represented or who are aware of the larger number of cultures in play. Despite the difficulty of coping with diversity and the system’s design that favors patients remaining within their locality, certain sorts of migrants and refugees are preferentially given access to this relatively closed system. Some European countries, while “increasing the number of restrictions on immigration of asylum seekers from conflict areas,” have simultaneously eliminated “restrictions in the case of highly skilled migrants (Finlay et al., 2011, p. 190). Such policies have the effect of “supporting brain drain flows,” while failing to “meet moral obligations to protect individuals seeking asylum” who are not trained health professionals (Stewart, 2008, p. 223).

Accessing Healthcare

Thus healthcare provision continues to be organized as if service users and providers were a stable local residential population bounded by national borders, even while supporting greater mobility of migrants who are skilled health professionals. Our research showed some of the complexity in the strategies that people employed to solve the problem of getting suitable healthcare.

We interviewed 24 adults (over 18 years of age) in four different countries in 2012, looking for a diversity sample in terms of age, place of residence, newness of migration, migration status, employment, and well-being. We sought participants from existing networks including an adult language class in Sweden, an ethnic diversity outreach service in rural England, and a solidarity organization in Spain, as well as snow-balling from informal contacts. Represented in the sample were people from urban, suburban, coastal, and rural neighborhoods; different economic backgrounds (wealthy retired, undocumented, unemployed, salaried, and on benefits); and various countries of origin (European and non-European migrants as well as locally born). Furthermore, those interviewed had spent different times resident in the country (from a lifetime to less than a year); various migration status (undocumented, asylum seeker, new, and long-standing citizens); different ages (from 18 to 73 years); and family status (single, widowed, married, and partnered with and without dependants).

Written and informed consent was given for the interviews to be audio recorded and to be used for research purposes, with ethical permission granted for the study granted via the School of Health and Human Sciences, University of Essex ethics committee and the Max Planck Institute for the Study of Religious and Ethnic Diversity, Department of Socio-Cultural Diversity, Göttingen, Germany. For further details of the methods see Green et al. (2014).

We were told complicated stories about the process of seeking out suitable care, circumnavigating a range of difficulties, and making use of different resources. Across our diversity sample in all four country settings, we found evidence of the need to accommodate “the views and perceptions of others (including institutionalised norms and restrictions)” in gaining access to suitable healthcare gave rise to “the need for navigational assistance” (Green et al., 2014, p. 1205).

This need for navigational assistance manifested as an expressed desire for:

advice on a range of symptoms, ailments, therapies, and treatment locations; facilitation with access to care (including making contact with services, companionship, and transport); financial or material help; linguistic and conceptual assistance to access and engage with healthcare at critical moments (Green et al., 2014, p. 1209).

This need for navigational help was evident in new and old migrants with various migration statuses, as well as those with long-standing and secure citizenship. In attempting to account for the patterns of diversity that gave rise to this need for navigational assistance, we set out some conditions of superdiversity influencing the nature of navigational assistance in healthcare as shown in Table 2.

Table 2. The conditions of superdiversity which shape the need for navigational help, adapted from Green et al. (2014).

In short, there was no single variable (such as being undocumented or a newly arrived immigrant or not speaking the local language) that explained who needed navigational assistance to access suitable healthcare. The fields of diversity described in the table intersected in such complex and various ways to influence who could gain access to the services they felt they needed.

This is illustrated by the case of a middle aged, highly educated German woman who was married to a West African Muslim and who, having converted to Islam, wore a headscarf. Although she was fluent in German, an insider to German culture with full entitlement to services, other aspects of her identity hindered her access. She described how interactions with healthcare professionals made her feel as though she did not belong, due to being Muslim and the mother of several Black children. In this woman’s case, despite having the full official and legal entitlement, as well as high cultural competency, her treatment as an outsider significantly hindered her access. By her own account, this woman’s gendered religious appearance as a Muslim woman and her role as a mother of Black children overrode other characteristics, which might have facilitated healthcare access, such as fluent language, a good education level, and knowledge of how the healthcare system worked, to undermine her claim to entitlement.

Our interviews illustrated that even where people reported fulfilling all the official, legal, and bureaucratic criteria for entitlement to services and had significant cultural competency, this did not guarantee access to services once serious illness struck. A Swedish citizen in Sweden, with full entitlement, described how her complex history of multiple cancers left her in acute need of sustained navigational help. She felt learning one means of accessing care did not help her once she moved to a new phase of treatment: for instance transferring from chemotherapy to radiotherapy (which were provided by different sections of the hospital) meant losing contact with a trustworthy nurse who had acted as a care coordinator. With each additional diagnosis a whole new set of routines had to be established. Having grown up in Sweden and being highly educated in science, this woman had no obvious communication barriers with healthcare staff, beyond having a serious disease. Her account illustrates the immense challenge of making sense of a healthcare system as a patient, even when motivated and apparently able to do so. Her case suggested that those who felt fully able to access the local healthcare system while in good health, such as a Latvian woman who had integrated into her Spanish boyfriend’s family and a Mauritanian who overcame his initial undocumented status through Spanish employment, might experience difficulties in the face of serious illness. Illness can make one a stranger in a formerly familiar territory, as illustrated by the case of an elderly German woman, who developed a chronic condition while also caring for a blind relative. The healthcare system in the rural area where she lived had been restructured, which this woman found alienating to the extent that she had no sense of where to look for help. Similarly, migrants arriving in a new healthcare system have to relearn ways of getting access, a process which can be bewildering.

One might expect people accessing care who are themselves healthcare professionals (both migrant and non-migrant) to be at an advantage, but this was not necessarily so. A woman who was undergoing specialist healthcare training in the UK was deeply dissatisfied with the quality of the services that she had received for an episode of depression and did not complete her full course of treatment, avoiding further contact with her general practitioner. And yet, she was utterly committed to the National Health Service in principle. The dual role of being both a patient and a skilled professional (whether in medicine, acupuncture, or herbalism) was described by others too, with people operating different logics in parallel to access services for themselves and for others. Having access to professional knowledge was sometimes useful, as with a trained nurse in the UK who successfully challenged the medication prescribed by her doctor. But in other cases such knowledge did not help.

How people experience their entitlement to services and their ability to negotiate is strongly influenced by their experience of illness. We had examples of people without formal entitlement, nonetheless arranging access to services that they needed and, as described above, we had people with full entitlement who found their access significantly blocked. How people experience their entitlement and cultural competency relates strongly to other aspects of identity, including as a patient and is not determined by having professional knowledge and experience.

This evidence from a small qualitative study supports the idea that there is no single dimension of diversity that has a determining effect on access to healthcare since unmet healthcare need or difficulties in accessing suitable care in our diversity sample was not associated with a single characteristic. We found evidence that discrimination can be a powerful impediment to accessing care, as is a lack of formal entitlement. A model for conceptualizing the effects of diversity in populations of health service users needs to take into account the interplay of different fields of diversity over time. Superdiversity’s description of multiple variables was relevant, but the situation in which a particular variable became significant was not predictable, suggesting the more situational or contingent approach of intersectionality.

Concluding Thoughts

Advocates of superdiversity suggest that we have an obligation to educate society regarding the new era wherein social reality is structured by diversity driven by ongoing global migration (Phillimore, 2011). This task is made more difficult by the rise of populist xenophobic political parties, rendering the expression of anti-immigrant sentiments acceptable, including around restricting newcomers’ access to healthcare and welfare.

The challenge is to conceptualize population complexity as a collective feature that influences shared social life and public service provision of the whole population, not just racialized or otherwise visible minorities or new immigrants. Alongside transnational migrants, this needs to include “internal migrants and to those individuals who do not move at all” (Meissner and Vertovec, 2014, p. 546). Furthermore, the implications for healthcare professionals as well as service users need to be covered. Contexts in which to consider such complexities include (1) the encounter between healthcare professional and patient; (2) representation in healthcare commissioning and research; and (3) health policy.

The Healthcare Encounter

Under “old” postcolonial migration regimes, we were urged toward “sympathetic imagination, tolerance, openness to other ways of life and thought, curiosity and mutual respect” (Parekh, 2008, p. 94), while widening access to welfare systems through multi-format, multilingual communication. In healthcare encounters, professionals were advised toward a welcoming style to “the stranger,” a tolerance of ambiguity, and even uncertainty in some clinical communication as better than rushing to a diagnosis based on misunderstood or missing patient evidence thereby giving an impression of certainty, but in fact covering up that which remained unknown (Gerrish et al., 1996). As the ongoing diversification of diversity plays out in professional as well as patient populations, common cultural knowledge cannot be assumed at any given healthcare encounter, and it is unclear who counts as the stranger.

While “old” migration brought together unfamiliar cultures and languages in healthcare settings, current migration, supported as it is by low-cost air-travel and internet-supported communication, involves virtual as well as physical transnationalism. Our interviews showed various strategies of accessing knowledge, opinion, and material from other countries, which add complexity to the clinical encounter. Managing patient and staff expectations that are formed in a range of different spaces introduces new challenges.

Alongside developing ways of managing consultations under conditions of multilingual superdiversity is the drive to increase the quality of care through standardized protocol-driven approaches, and the swift distribution of patient notes through digital methods. Educating trainee healthcare professionals how to manage the tension between distributed standardization and flexibility (Svenberg et al., 2013; Swinglehurst et al., 2014) involves modeling how to stay aware of the values that are important to individuals via interpersonal negotiation and avoid stereotyping (Culley, 2014) while attending to the protocol.

The idea of cultural competence, sometimes taught as part of “diversity training,” has been promoted as a means of addressing these tensions. Critique of cultural competency models has described two interrelated problems: first, cultural competency tends to treat patients’ minority culture as problematic, while leaving the professional culture of healthcare providers under-interrogated; and second it follows a model which perceives culture as something static and belonging to groups (Baumann, 1999, p. 81f). Could healthcare professional training interrogate the culture of medicine as part of what is structuring healthcare encounters? Awareness of the particularities of medical professional culture through critical reflexive practice represents one means of avoiding the pathologization of patients labeled as diverse, while simultaneously ignoring the diversity in the professional population. In addition to a more reflexive approach to cultural difference, migration related literacy is needed regarding how legal status is constructed and how migration trajectories shape the process of being ill and of looking for help.

Beyond the Healthcare Consultation

Beyond the interpersonal encounter between patient and professional are the longer term issues of the work of primary research (Redwood and Gill, 2013), in which diverse groups are underrepresented, as well as the commissioning and evaluating of services. Despite this underrepresentation being well documented, it remains routine to exclude participants from research and consultation if they do not speak good English, on grounds of expense. If health services are to respond to superdiversity, there needs to be greater involvement of minorities and new migrants in shaping service delivery (Phillimore, 2011). In order to develop excellent research that is relevant to a population’s needs, a diverse public has to be involved (Chief Medical Officer and NIHR, 2015) otherwise the range of world views that reflect the diversity of the public is missed (Green, 2016). Such involvement should not simply benefit the new arrivals and marginalized minorities, but rather be a means of building a sustainable and inclusive health service that will benefit the whole population and be robust enough to respond to future forms of diversity. The successful management of multiple cultural identities has been associated with well-being (Yampolsky et al., 2013), which counters the tendency to research pathological aspects of minority racialized experience and suggests the beneficial possibilities of an inclusive way of working. Since healthcare providers, like service users, are highly diverse, the benefit of inclusive working that acknowledges everyone’s contribution is a key social good for the whole population.

Policy

The difficulty is to create a model or concept that can cope with great complexity that is also contingent, particularly when this complexity may include contradictions that cannot be easily resolved. For instance, ill people may desire authoritative medical care, while also wishing to be treated as individuals and consulted at key, although not necessarily predictable, moments: and how to resolving these two competing needs is not straightforward. Another of these contradictions is including the interactional identity work of diversity in the context of powerful discriminatory structures that individual agency cannot easily affect. Furthermore, such a model or concept needs to be dynamic enough to keep up with ongoing changes.

The policy implications of the diversification of diversity are urgent, perhaps so much so that the term superdiversity has been adopted before the research models and methods have been developed to support it. This carries the risk of the terminology of superdiversity failing, as have previous vocabularies of difference, because they have not been conceptualized properly. Medical sociology should be taking ideas from social science to apply them to medical contexts, thereby testing the concepts as well as informing practice. In this respect, the answer to the question of this paper’s title is “yes.” But whether superdiversity can be operationalized in healthcare settings before the idea is itself superseded by the next set of changes is a question that is being tested in ongoing research (Phillimore et al., 2015). Another question is whether the complexity that superdiversity seeks to describe can be modeled for quantitative research as well as described in qualitative research.

Author Contributions

All authors were involved in the original devising of the research project, the ongoing gathering of interview material, the coding of interview material, and in theoretical development of concepts reported here. HB first drafted this article, with the other authors commenting and revising the draft prior to submission.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Funding

Funding for this study was granted by the Max Planck Institute for the Study of Religious and Ethnic Diversity, Department of Socio-Cultural Diversity, Göttingen, Germany.

References

Ahmad, W. I. U. (1992). Is medical sociology an ostrich? Reflections on “race” and the sociology of health. Med. Soc. News 17, 16–20.

Amin, A. (2004). Multi-ethnicity and the idea of Europe. Theory Cult. Soc. 21, 1–24. doi:10.1177/0263276404042132

Aspinall, P. J. (2012). Answer formats in British census and survey ethnicity questions: does open response better capture “superdiversity”? Sociology 46, 354–364. doi:10.1177/0038038511419195

Baumann, G. (1999). The Multicultural Riddle: Rethinking National, Ethnic, and Religious Identities. Zones of Religion. New York: Routledge.

Berg, M. L., and Sigona, N. (2013). Ethnography, diversity and urban space. Identities 20, 347–360. doi:10.1080/1070289X.2013.822382

Bhambra, G. (2014). Connected Sociologies. London: Bloomsbury Open Access. Available at: https://www.bloomsburycollections.com/book/connected-sociologies/

Blommaert, J. (2013). Citizenship, language, and superdiversity: towards complexity. J. Lang. Identity Educ. 12, 193–196. doi:10.1080/15348458.2013.797276

Blommaert, J. (2014). Infrastructures of superdiversity: conviviality and language in an Antwerp neighborhood. Eur. J. Cult. Stud. 17, 431–451. doi:10.1177/1367549413510421

Bradby, H. (1995). Ethnicity: not a black and white issue. A research note. Sociol. Health Illn. 17, 405–417. doi:10.1111/1467-9566.ep10933332

Bradby, H. (2003). Describing ethnicity in health research. Ethn. Health 8, 5–13. doi:10.1080/13557850303555

Chief Medical Officer, NIHR. (2015). Going the Extra Mile: Improving the Nation’s Health and Wellbeing through Public Involvement in Research. The Final Report and Recommendations to the Director General Research and Development/Chief Medical Officer (CMO) Department of Health of the “Breaking Boundaries” Strategic Review of Public Involvement in the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). Available at: https://www2.warwick.ac.uk/fac/med/about/centres/clahrc/ppi/resources/final_published_copy_-_extra_mile_-_march_2015.pdf

Connell, J. (2008). A Global Health System? The International Migration of Health Workers. New York: Routledge.

Culley, L. (2014). Editorial: nursing and super-diversity. J. Res. Nurs. 19, 453–455. doi:10.1177/1744987114548755

De Bock, J. (2015). Not all the same after all? Superdiversity as a lens for the study of past migrations. Ethn. Racial Stud. 38, 583–595. doi:10.1080/01419870.2015.980290

Fanshawe, S., and Sriskandarajah, D. (2010). Super-Diversity and the End of Identity Politics in Britain. Available at: http://www.ippr.org/files/images/media/files/publication/2011/05/you_cant_put_me_in_a_box_1749.pdf

Finlay, J. L., Crutcher, R. A., and Drummond, N. (2011). “Garang”s Seeds’: influences on the return of Sudanese-Canadian refugee physicians to post-conflict South Sudan. J. Refug. Stud. 24, 187–206. doi:10.1093/jrs/feq047

Gerrish, K., Husband, C., and Mackenzie, J. (1996). Nursing for a Multi-ethnic Society. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Glinos, I. A., Baeten, R., Helble, M., and Maarse, H. (2010). A typology of cross-border patient mobility. Health Place 16, 1145–1155. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.08.001

Green, G. (2016). Power to the people: to what extent has public involvement in applied health research achieved this? Res. Involv. Engagem. 2. doi:10.1186/s40900-016-0042-y

Green, G., Davison, C., Bradby, H., Krause, K., Mejías, F. M., and Alex, G. (2014). Pathways to care: how superdiversity shapes the need for navigational assistance. Sociol. Health Illn. 36, 1205–1219. doi:10.1111/1467-9566.12161

Helberg-Proctor, A., Meershoek, A., Krumeich, A., and Horstman, K. (2016). Ethnicity in Dutch health research: situating scientific practice. Ethn. Health 21, 480–497. doi:10.1080/13557858.2015.1093097

Hörbst, V., and Gerrits, T. (2016). Transnational connections of health professionals: medicoscapes and assisted reproduction in Ghana and Uganda. Ethn. Health 21, 357–374. doi:10.1080/13557858.2015.1105184

Meissner, F., and Vertovec, S. (2014). Comparing super-diversity. Ethn. Racial Stud. 38, 541–555. doi:10.1080/01419870.2015.980295

Migge, B., and Gilmartin, M. (2011). Migrants and healthcare: investigating patient mobility among migrants in Ireland. Health Place 17, 1144–1149. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2011.05.002

Muir, H. (2015). Labour and Tories face decline if they ignore minority vote, study finds. Guardian. Available at: http://www.theguardian.com/politics/2014/jun/20/labour-tories-minority-vote

Ndhlovu, F. (2016). A decolonial critique of diaspora identity theories and the notion of superdiversity. Diaspora Stud. 9, 28–40. doi:10.1080/09739572.2015.1088612

Parekh, B. C. (2008). A New Politics of Identity: Political Principles for an Interdependent World. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Phillimore, J. (2011). Approaches to health provision in the age of super-diversity: accessing the NHS in Britain’s most diverse city. Crit. Soc. Policy 31, 5–29. doi:10.1177/0261018310385437

Phillimore, J., Bradby, H., Knecht, M., Padilla, B., Brand, T., Cheung, S. Y., et al. (2015). Understanding healthcare practices in superdiverse neighbourhoods and developing the concept of welfare bricolage: protocol of a cross-national mixed-methods study. BMC Int. Health Hum. Rights 15:16. doi:10.1186/s12914-015-0055-x

Ratcliffe, R. (2015). How will “super diversity” affect the future of British politics? Guardian. Available at: http://www.theguardian.com/education/2014/oct/08/immigration-britains-changing-identity

Redwood, S., and Gill, P. S. (2013). Under-representation of minority ethnic groups in research – call for action. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 63, 342–343. doi:10.3399/bjgp13X668456

Reyes, A. (2014). Linguistic anthropology in 2013: super-new-big: year in review: linguistic anthropology. Am. Anthropol. 116, 366–378. doi:10.1111/aman.12109

Schierup, C., Hansen, P., and Castles, S. (2006). Migration, Citizenship, and the European Welfare State: A European Dilemma. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sepulveda, L., Syrett, S., and Lyon, F. (2011). Population superdiversity and new migrant enterprise: the case of London. Entrepreneur. Reg. Dev. 23, 469–497. doi:10.1080/08985620903420211

Stewart, E. (2008). Exploring the asylum-migration nexus in the context of health professional migration. Geoforum 39, 223–235. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2007.04.002

Stronks, K., Kulu-Glasgow, I., and Agyemang, C. (2009). The utility of “country of Birth” for the classification of ethnic groups in health research: the Dutch experience. Ethn. Health 14, 255–269. doi:10.1080/13557850802509206

Svenberg, K., Mattsson, B., and Lepp, M. (2013). Encounters with patients from Somalia: experience among vocational trainees in Swedish general practice. Int. J. Med. Educ. 4, 162–169. doi:10.5116/ijme.51fc.dc05

Swinglehurst, D., Roberts, C., Li, S., Weber, O., and Singy, P. (2014). Beyond the “dyad”: a qualitative re-evaluation of the changing clinical consultation. BMJ Open 4, e006017. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006017

Vertovec, S. (2007). Super-diversity and its implications. Ethn. Racial Stud. 30, 1024–1054. doi:10.1080/01419870701599465

Vertovec, S. (2016). Super-Diversity as Concept and Approach: Whence It Came, Where It’s At, and Whither It’s Going – MPI-MMG. Keynote Address for the Conference on ‘Super-Diversity: A Transatlantic Conversation’, Graduate Center, City University of New York, 4-5 April 2016. Available at: http://www.mmg.mpg.de/online-media/online-lectures/2016/steven-vertovec-mpi-mmg-super-diversity-as-concept-and-approach-whence-it-came-where-its-at-and-whither-its-going/

Wessendorf, S. (2014). “Being open, but sometimes closed”. Conviviality in a super-diverse London neighbourhood. Eur. J. Cult. Stud. 17, 392–405. doi:10.1177/1367549413510415

Yampolsky, M. A., Amiot, C. E., and de la Sablonnière, R. (2013). Multicultural identity integration and well-being: a qualitative exploration of variations in narrative coherence and multicultural identification. Front. Psychol. 4:126. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00126

Yuval-Davies, N. (2006). Intersectionality and feminist politics. Eur. J. Womens Stud. 13, 193–209. doi:10.1177/1350506806065752

Keywords: healthcare access, diversity, barriers, superdiversity, migration

Citation: Bradby H, Green G, Davison C and Krause K (2017) Is Superdiversity a Useful Concept in European Medical Sociology? Front. Sociol. 1:17. doi: 10.3389/fsoc.2016.00017

Received: 08 November 2016; Accepted: 23 December 2016;

Published: 20 January 2017

Edited by:

Sakari Karvonen, National Institute for Health and Welfare, FinlandReviewed by:

Fátima Alves, Universidade Aberta, Portugal; University of Coimbra, PortugalManbinder Singh Sidhu, University of Birmingham, UK

Martha Judith Chinouya, University of Liverpool, UK

Copyright: © 2017 Bradby, Green, Davison and Krause. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hannah Bradby, aGFubmFoLmJyYWRieUBzb2MudXUuc2U=

Hannah Bradby

Hannah Bradby Gill Green

Gill Green Charlie Davison2

Charlie Davison2 Kristine Krause

Kristine Krause