- Faculty of Medicine, Institute for Social Medicine and Health Economics, Otto-von-Guericke University, Magdeburg, Germany

Social studies on close relationship (CR) in old age of Western societies present the heterosexual couple as the dominant model of the late CR. Researchers focus mainly on couples in long-term relationships living in a common household. But in Germany, for example, only about half of all men and women between the ages of 65 and 75 live in a marital heterosexual relationship (Statistisches Bundesamt, 2016). In addition to the increasing change in the bonding behavior of older people, a differentiated picture of CR is already emerging. Accordingly, there are a large number of people for whom other forms of living together in old age are important. In population statistics (multiple) re-married, same-gender or non-marital relationship models in old age are underrepresented although they are particularly relevant in modern societies, for example in East Germany and for younger generations. This article is a critical reflection on the heteronormative view of late-life CR in the current gerontological research that leads to marginalization of older people whose CR does not correspond to this ideal. Heteronormativity refers to the “assumption of two clearly distinguishable, mutually exclusive sexes” according to which heterosexual desire is regarded as natural and normal (Hartmann and Klesse, 2007, p. 7). With a de-constructionist approach the heteronormative foundation of scientific categories can be demonstrated using the example of two gerontological studies. A normativity-critical research practice (Katz, 1996; Estes, 2011, p. 314) can help to make the diversity of late CR visible and support realistic empirical findings in gerontology.

Introduction: Research On Close Relationships (CR) in Old Age

In Western gerontology, close relationships (CR) are regarded as contributing to individual well-being and health in old age (Franke and Kulu, 2018, p. 841). The intimate bonding between (two) individuals appears as a source of social recognition, commitment and support (Walker and Luszcz, 2009). CR in later life is recognized as an institution that creates sense for its participants (Calasanti and Kiecolt, 2007; Métrailler, 2018). Sociologists characterize CR as a maximum form of personal relationship (Hirschauer, 2013, p. 40) through the (at least assumed) temporally and personally consistent and exclusive commitment between (often two) individuals. Its emotional impact sets it apart from other social relationships (Hirschauer, 2013). There is no common definition of CR in science. De Vries and Blando describe: “[A] wide array of definitions has been offered, leading authors to call for self-definitions of couplehood. That is, just because two people live together does not mean that they are a “couple”; similarly, just because a person lives alone does not mean that he or she is ‘single'.” (de Vries and Blando, 2004, p. 20). Terms such as “romantic,” “intimate,” and “close” relationship must be distinguished to describe this unique form of “personal relationship” (Lenz, 2006). In gerontology, the discourse on CR is inadequate.

Scientific authors who use the term “romantic relationship” (Bennett et al., 2013; Kuchler and Beher, 2014) refer to the ideal of romantic love, which is consistent in modern societies (Bachmann, 2014; Burkart, 2014, 2018; Kuchler and Beher, 2014). This term emphasizes the specificity of this relationship, which lies in its emotional impact. Georg Simmel, one of the founding fathers of German sociology, already ascribes an inherent value to “intimate relationships” for participants. In a couple relationship arises a “personal interdependence” developing on the basis of an emotional structure, in which everyone refers to the only other and no one else (Kuchler and Beher, 2014 pp. 127). Simmel understands this as a prerequisite for intimacy that occurs only in dyadic relationships (Kuchler and Beher, 2014, p. 128). In literature the term “intimate relationship” (Karlsson and Borell, 2002), related to Simmel, as well as terms that transfer other theoretical approaches such as “long-term relationship” (Calasanti and Kiecolt, 2007) are often used without explication.

Following the concern of sociology to disenchant the idealized model of love relationship (Kuchler and Beher, 2014, p. 8), a large number of social scientists have already attempted to counter the transfigured ideal of love by theorizing CR. In the theoretical distinction to other social relationships, they have referred to duration and stability of relationships, residential arrangement between its participants, and types of shared intimacy and sexuality (Kuchler and Beher, 2014 p. 11). Aging studies discuss CR within these three domains, particularly in connection to age-related social, psychological and physical changes (Walker and Luszcz, 2009). As theoretical concepts are limited open questions remain regarding the relationship between emotional value in CR and its significance to old age.

Through an ethnographic lens, research approaches to the phenomenon of CR in old age are always historically, socially, and personally contextualized. This influences the discourse within the different scientific communities (Klesse, 2007, p. 45). For example, there are considerable differences in the discourse modi between German aging studies and other international (especially US-American or Scandinavian) perspectives (Settersten and Angel, 2011; Gardner et al., 2012; Neysmith and Aronson, 2012). Thus, certain aspects of social normative frame research practice. Researchers reference certain concepts of aging, such as successful, healthy or active aging and theoretical approaches such as disengagement or activity theory (Jones and Higgs, 2010; Bülow and Söderqvist, 2014; Van Dyk, 2015). Often, Sociology of CR in old age focuses on dealing with increasing needs for support and care as well as their effect on relationship dynamics and gender-specific role distribution (Walker and Luszcz, 2009). Therefore, the impact of CR on quality of life and health is often examined (Settersten and Angel, 2011). It is also noticeable that most researchers refer to traditional forms of CR while ignoring discontinuous and dynamic CR-concepts. These include, for example, CRs with periods of separate living in non-institutionalized arrangements, or non-sexual CRs. Furthermore, the “supraindividual” emotional impact of CR between its participants and its significance for old age remains underexposed (Kuchler and Beher, 2014, p. 124).

There are other phenomena that remain invisible if CR is to be captured in its intertwining with aging. Despite intended reflexive investigations of phenomena around CR in old age, scientific processes are based on actions of selection, emphasis, omission and re-contextualization (Klesse, 2007, p. 45). This limits the perception of the research subject from the outset. CR and its relevance in experiencing aging can only be partially reconstructed. A reflexive analysis makes it possible to distinguish CR in its peculiarity from other forms of relationship. Besides, it would support the visibility of social normative to gender-specific interaction in partnerships, stereotypical division of labor or heterosexual monogamous dyadic cohabitation (Klesse, 2007).

This article is intended to inspire a discussion about the hegemonic assumption of two-gender sexuality in CR research in old age (Hartmann and Klesse, 2007, p. 9) that generates heteronormativity through scientific techniques of selection and highlighting. After a first de-constructionist step finally an anti-categorical perspective1 provides impulses for a reflective research practice and to a theoretical concept of CR in gerontology that integrates its diversity and its emotional impact in late life phases.

Social Change and Non-Traditional Relationships in Old Age

Most research about CR is based on methodological sexism (Hirschauer, 2013, p. 43), because the gender-unequal coupleship is assumed as a natural form of close or intimate bonding. In addition, many analyses based on large representative surveys define forms of CR through a limiting category system such as single, married/unmarried, divorced/separated, widowed, remarried, or new non-married relationship (Calasanti and Kiecolt, 2007, p. 12). At the same time, they hold up the ideal of heterosexual couple relationship.

In contrast, especially for the younger generation of older people, non-traditional forms of CR are a reality (Kimmel et al., 2006). Franke and Kulu state that in the UK, for example, premarital and postmarital cohabitation are increasing, foremost in younger cohorts born in the 1960s (Franke and Kulu, 2018, p. 838). This just applies to CRs that are recognizable as heterosexual. In Germany, only half of all men and women between the ages of 65 and 75 live in a marital heterosexual relationship (Statistisches Bundesamt, 2016). Most statistics do not take into account the different relationship systems of the other half, nor the importance that older people associate with CR.

Processes of social transformation have influenced the institutionalized patterns of biography and family patterns after increasing prosperity by the establishment of welfare state (Beck, 1986; Giddens, 1993; Lenz, 2006, p. 127). This is accompanied in particular by the women's movement and their participation in education and labor market. These processes also influenced concepts of CR (de Vries and Blando, 2004; Lenz, 2006; Burkart, 2018). The traditional model of marriage between men as breadwinners and decision-makers in family matters and women as those responsible for domestic, family and “emotional work” (Pugh, 2017) is now being extended by various forms of CR that reflect the characteristics of individualized lifestyles (Kimmel et al., 2006; Burkart, 2018). Since the 1980s at the latest, sociologists have been observing married coupleship as a discontinued model (Engstler and Klaus, 2017) that has been replaced by non-traditional forms of living together (Beck, 1986). The change in values of CR in the course of social change has been sociologically theorized but inadequately considered methodically. Franke and Kulu therefore propose a differentiation of CR, as many studies dealing with CR in old age generate omissions due to a lack of methodology. “With declining marriage rates and the spread of cohabitation and separation, a distinction between partnered and non-partnered individuals is critical to understanding whether and how having a partner influences the individuals' health behavior and mortality” (Franke and Kulu, 2018, p. 838).

In context of social change, liberalization processes have paved the way to make non-traditional CR models livable, both socially and legally. The variation of modern CR is reconstructed according to sexual orientation/desires, gender of the respective partners, duration or “union type” (Brown and Kawamura, 2010) as well as to the number of individuals involved (e.g., ranging from dyadic-monogamous-exclusive to polygamous-inclusive). de Vries and Blando, 2004 complement these characteristics by pointing out relationship constellations that are “socially or legally sanctioned,” for example co-relations that exist alongside socially and legally recognized CRs (p. 20). The dynamics of (de-) institutionalized forms of living together in CR is reflected, both biographically and socially (Calasanti and Kiecolt, 2007; Bildtgard and Öberg, 2017). From a biographical perspective the dynamics of CR can be seen in the individual life course. At the socio-structural level dynamics of modern CR are interwoven with social determinants such as age, cohort affiliation, gender, social origin, educational level, and socio-economic status (Karlsson and Borell, 2002; Franke and Kulu, 2018). CR is therefore an intersectionally embedded social phenomenon (McCall, 2005). To capture its complexity, gerontology has to develop useful theoretical and methodological approaches. The scientific discourse on CR in old age should take place at the international level to transfer methodological developments in the future (Gardner et al., 2012).

Methodological Blindness for “Emotional Change”

Methodological selectivity, omissions and misrepresentations consistently lead to biased findings. It can therefore be assumed that results in population studies are limited in relation to aging and CR. A closer look at the stock of statistical data on CR-constellations of the LSBT*I population in old age confirms this assumption: A lack of data can be observed particularly in German-speaking countries (Kroh et al., 2017; Langer, 2017). In gerontology research, these topics are mostly examined with qualitative research designs (Lottmann et al., 2016; Langer, 2017).

Moreover, many studies are blind to the differences that persist in older generations of countries formerly ruled by socialism. In the GDR, other forms of bonding behavior have emerged due to labor market participation, womens' and family policies. The position of the individual in socialism was subordinated to the collective. With the reunification of Germany, the effects of system differences became noticeable. The socialist ideology intended the equation of man and woman on the legal level in that the state grouped both genders into a category of “workers.” But with the integration of women into full employment, they have always been exposed to a double burden (Richter, 2018, p. 38). In comparison to women in West Germany, East German women have already carried out much earlier family work in addition to employment. Economically, women in the former GDR had a more independent position and were not socially excluded during maternity or even after divorce (Klärner and Knabe, 2016; Matthäus and Kubiak, 2016). In comparison to western Germany, divorce was less socially sanctioned which led more often people to remarry or enter a new partnership. Framework conditions affected self- and partnership-concepts. Consequently, the ideal of staying in the same CR for life became less significant. In the GDR, unmarried forms of CR and patchwork families were an early phenomenon. Despite the formal framework of the state gender equalization, structural inequalities and the traditional gender-specific dynamic in coupleship remained intact. The couple's interaction was still characterized by the traditional heterosexual model of CR with the stereotype division of labor between men and women (Richter, 2018, p. 41). And even though the traditional model has been reproduced in coupleship, it is plausible that the structural framework has influenced the individual to associate CR with an emotional value that is common in capitalist societies. Current gerontological research should consider how partnership concepts of couples socialized in the socialist system can be methodically treated.

The effects of social change on CR in old age are also reflected in expectations of (re-)entering CR. From a life-course perspective the goals and expectations of CR in later life differ from those in younger years (Jong Gierveld and Peeters, 2003; Bennett et al., 2013; Koren, 2015). In later stages of life, a relationship (if intended at all) is no longer entered into with starting a family and securing the livelihood of children (Lenz, 2006, p. 15). The decision to enter or to maintain CR in old age is often chosen, consciously or unconsciously, as a strategy preventing loneliness and experiencing affection and intimacy (Calasanti and Kiecolt, 2007). Moreover, older people seem to be concerned with preserving autonomy and their own independence without the help of children or professional support systems (Koren, 2015, pp. 1876, 1879; Bildtgard and Öberg, 2017).

In old age, the expectations and demands to arrange living together in a CR also change. Karlsson and Borell (2002) prove in their study that especially women in a non-marital heterosexual CR in old age report the advantages of separate households (p. 17). By living apart together (LAT) they experience a high degree of autonomy toward their male partners. In this way, women can strike a self-determined balance between privacy and intimacy with their partner without giving up their (possibly struggled) independence (Karlsson and Borell, 2002).

As unmarried forms of CR and patchwork families play an increasingly important role in modern societies, this will require more attention in gerontology.

As Walker and Luszcz (2009) suggest in their literature review, three domains of research of CR on old age can be identified: First, researchers refer to the sexual orientation/desire within the relationship as well as to gender composition, second, the duration of a relationship in order to make subsequent statements about its stability, and third, residential arrangements. The task of capturing further dimensions of CR in old age scientifically has not yet been solved. The sociological concepts of CR used in gerontology approach the phenomenon only instrumentally in limited categories. Moreover, research about CR is blind to certain phenomena beyond categories of heteronormativity and monogamy. Explorative studies that focus on under-represented phenomena make them visible, but also run the risk of marginalizing them as “special cases.”

Consequences for Gerontological Research Practice

One way to overcome this dilemma may be to de-construct research methods of gerontological studies by an anti-categorical approach (McCall, 2005; Walgenbach, 2012). With this perspective it is possible to examine intertwined phenomena of CR in old age. Thereby, relevant markers of difference are considered in their interdependence to overcome isolated or one-dimensional perspectives on power and domination relations in scientific processes (Walgenbach, 2012, p. 65). This is preceded by the understanding that scientific practice holds a powerful social position (Katz, 1996). This critical approach has three aims: First, to uncover processes and structures of selectivity and omission that lead to under-representation and gaps in the definition and construction of social reality (Berger et al., 2016), second, to make visible people whose identity crosses the boundaries of traditionally constructed groups (McCall, 2005, p. 1774); and third, to adequately determine the facets of CR and its significance for individuals in later adulthood.

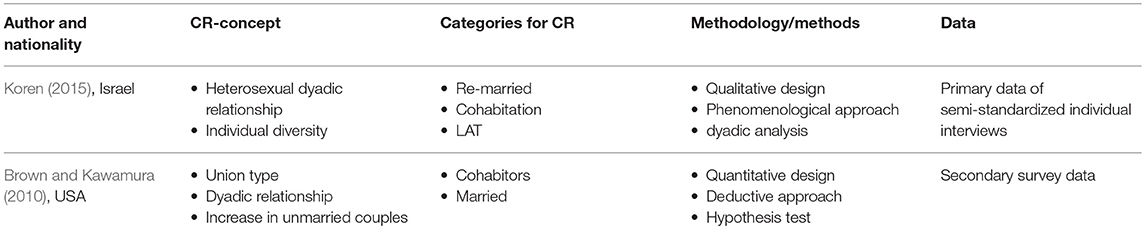

Table 1 (p. 7) compares underlying CR-concepts of a quantitative and a qualitative study. In the first study, a hypothesis-based analysis by Brown and Kawamura (2010) examines the relationship quality of non-married and married couples. The study is based on longitudinal data from a representative sample of the National Life, Health, and Aging Project (NSHAP) from 2005 to 2006. These data were supplemented by qualitative data of a subsequent semi-standardized questionnaire (Brown and Kawamura, 2010, p. 780). The researchers assumed that there is a correlation between union type and relationship quality in the age bracket of 57–85 (Brown and Kawamura, 2010, p. 779). The authors divide the sample into two groups, cohabitants and married. They take into account the increase of cohabitation and non-married couples in the American population, but create a dichotomous concept of CR. The sample description can be considered as a selective act, in which forms deviating from these two categories remain invisible. The second study by Koren (2015) is based on a qualitative interview questionnaire of 20 heterosexual Israeli couples aged 66–92. She examines the relationship between second couplehood and aging. Using primary data opens up other analysis options, but also involves a high degree of responsibility for theoretical conception by researchers. Koren divides her sample into three CR-categories: (1) remarried coupleship, (2) cohabitants, and (3) LAT-couples (p. 1870). She points out that two pairs could not be included in the comparative analysis because their CR-concept did not correspond to the categories. The specificity of this qualitative study is the direct contact between the participating couples and the researchers. In this way, couples could personally describe their current relationship constellation.

A common feature of these studies is presupposing CR only occurs as a dyad. The categories used in the studies are the results of selection procedures carried out by researchers ahead preparing analyses. These constructions limit the breadth of the CR phenomenon. Moreover, the defined CR-categories of both studies do not integrate the inherent emotional significance of CR in old age. Both studies capture CR only in the three domains described by Walker and Luszcz (2009) mentioned above.

Reconstructing CR comprehensively can be achieved strategically by excluding limitations in research design. Researchers should ask themselves how they structure a phenomenon with research practice. As Erel et al., 2007, (p. 247) point out, this seems to be challenging, since many selection mechanisms often remain unspoken in research processes.

Researchers can give informants the opportunity to define their “union type” themselves and to describe the associated significance for them. Traunsteiner (2016), for example, chooses this strategy in her study on lesbian CR in old age in Austria.

In quantitative surveys, open questions could be used to an intra-categorical extension obtaining a comprehensive design (McCall, 2005; Walgenbach, 2012). The questionnaire of the German SOEP survey2 for example, observes since 2016 the sexual orientation of informants based on a categorical self-classification as homosexual, bisexual or none of them (Kroh et al., 2017, p. 688). Nevertheless, the new SOEP strategy fails because it just includes couples living in the same household. It shows that it will become increasingly difficult for researchers to methodically address the partnership's diversity in old age in a changing society. A first step would be to let participants speak.

Author's Note

The article was written in context of the author's dissertation project, who works as a research assistant in the research project “Autonomy in Old Age”. The research project is funded by the EU-funding program EFRE and by the Ministry of Economics, Science and Digitization of Saxony-Anhalt.

Author Contributions

JP is the main author of this article and, with the support of B-PR, structured and finalized the argumentation. JP is therefore the contact person for the reviewers involved.

Funding

The publication costs of the contribution are covered by the financial budget of the Institute for Social Medicine and Health Economics of the Medical Faculty of Otto-von-Guericke University.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

CR, Close relationship; LAT, Living apart together; SOEP, Socio-economical panel.

Footnotes

1. ^ Dietze, Haschemi Yekani, and Michaelis (2018, August 8). Queer und Intersektionalität [Queer and intersectionality] Retrieved from www.portal-intersektionalität.de.

2. ^ The Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP) is an Important German Longitudinal Study With Annual Data on Private Households Since 1984. German Institute for Economic Research (DIW) (2018, November 8). Available online at https://www.diw.de/en/diw_02.c.221178.en/about_soep.html

References

Bachmann, U. (2014). Romantische Liebe zwischen Ideen, Institutionen und Interessen. Zur Ausdifferenzierung der erotischen Wertsphäre bei Max Weber [Romantic love between ideas, institutions and interests. To differentiate Max Weber's erotic sphere of values], in T. Morikawa, ed Kulturen der Gesellschaft. Die Welt der Liebe: Liebessemantiken Zwischen Globalität und Lokalität, 101–137.

Beck, U. (1986). Risikogesellschaft: Auf dem Weg in Eine Andere Moderne [Risk society. On a way into Another Modern Era] (Erstausg., 1. Aufl.). Edition Suhrkamp.

Bennett, K. M., Arnott, L., and Soulsby, L. K. (2013). You're not getting married for the moon and the stars: the uncertainties of older British widowers about the idea of new romantic relationships. J. Aging Studies 27, 499–506. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2013.03.006

Berger, P. L., Luckmann, T., and Plessner, H. (2016). Die Gesellschaftliche Konstruktion der Wirklichkeit: Eine Theorie der Wissenssoziologie [The Social Construction of Reality: A Theory of Sociology of Knowledge] (26. Auflage). Fischer 6623. Frankfurt am Main: Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag.

Bildtgard, T., and Öberg, P. (2017). Intimacy and Ageing: New Relationships in Later Life. Ageing in a Global Context. Bristol: Policy Press.

Brown, S. L., and Kawamura, S. (2010). Relationship quality among cohabitors and marrieds in older adulthood. Soc. Sci. Res. 39, 777–786. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2010.04.010

Bülow, M. H., and Söderqvist, T. (2014). Successful ageing: a historical overview and critical analysis of a successful concept. J. Aging Stud. 31, 139–149. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2014.08.009

Burkart, G. (2014). “Paarbeziehung und Familie als vertragsförmige Institutionen? [Couple relationship and family as contractual institutions?],” in Familienforschung. Familie im Fokus der Wissenschaft, eds A. Steinbach, M. Hennig, and O. Arránz Becker (Wiesbaden: Springer VS), 71–91.

Burkart, G. (2018). “Soziologie der Paarbeziehung: eine Einführung [Sociology of the couple relationship: an introduction],” in Studientexte Soziol (Wiesbaden: Springer VS). doi: 10.1007/978-3-658-19405-5

de Vries, B., and Blando, J. A. (2004). “The study of gay and lesbian aging: lessons for social gerontology,” in Gay and Lesbian Aging: Research and Future Directions, eds G. Herdtand and B. de Vries (New York, NY: Springer), 3–28.

Engstler, H., and Klaus, D. (2017). “Auslaufmodell traditionelle Ehe‘? Wandel der Lebensformen und der Arbeitsteilung von Paaren in der zweiten Lebenshälfte [Discontinued 'traditional marriage' model? Change in living arrangements and division of labour of couples in the second half of life],” in Alter im Wandel, eds K. Mahne, Wolff, Julia, Katharina, J. Simonson, and C. Tesch-Römer (pp. 201–213). Wiesbaden: VS Springer. Available online at https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007%2F978-3-658-12502-8_13.pdf

Erel, U., Haritaworn, J., Gutiérrez Rodríguez, E., and Klesse, C. (2007). “Intersektionalität oder simultaneität?! – Zur verschränkung und gleichzeitigkeit mehrfacher machtverhältnisse – eine einführung [Intersectionality or simultaneity?! - on the entanglement and simultaneity of multiple power relations - an introduction],” in Heteronormativität: Empirische Studien zu Geschlecht, Sexualität und Macht, eds J. Hartmann, C. Klesse, P. Wagenknecht, and B. Fritzsche (Wiesbaden: VS-Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften), 239–250.

Estes, C. L. (2011). “Crisis and old age policy: Chapter 19,” in Handbook of Sociology of Aging, eds R. A. Settersten and J. L. Angel (New York, NY; Heidelberg; London: Springer Science and Business), 297–320.

Franke, S., and Kulu, H. (2018). Cause-specific mortality by partnership status: simultaneous analysis using longitudinal data from England and Wales. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 27, 838–844. doi: 10.1136/jech-2017-210339

Gardner, P., Katagiri, K., Parsons, J., Lee, J., and Thevannoor, R. (2012). “Not for the fainthearted”: engaging in cross-national comparative research. J. Aging Studies 26, 253–261. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2012.02.004

Giddens, A. (1993). Wandel der Intimität: Sexualität, Liebe und Erotik in Modernen Gesellschaften [The Transformation of Intimacy: Sexuality, Love and Eroticism in Modern Societies (Dt. Erstausg). Frankfurt am Main: Fischer-Taschenbücher.

Hartmann, J., and Klesse, C. (2007). “Heteronormativität. empirische Studien zu Geschlecht, Sexualität und Macht–eine Einführung [Heteronormativity. empirical studies on gender, sexuality and power-an introduction],” in Heteronormativität: Empirische Studien zu Geschlecht, Sexualität und Macht, eds J. Hartmann, C. Klesse, P. Wagenknecht, and B. Fritzsche (Wiesbaden: VS-Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften), 7–16.

Hirschauer, S. (2013). Geschlechter(un)gleichheiten, Paarfindungen, Paarbindungen: Geschlechts(in)differenz in geschlechts(un)gleichen Paaren. Zur Geschlechterunterscheidung in intimen Beziehungen [Gender (in)equality, pair finding, pair bonding: Gender(in)difference in gender(in)equal pairs. Gender differentiation in intimate relationships]. GENDER, 37–56. Available online at https://www.theorie.soziologie.uni-mainz.de/files/2015/11/Geschlechtsindifferenz-in-geschlechtsungleichen-Paaren.pdf

Jones, I. R., and Higgs, P. F. (2010). The natural, the normal and the normative: contested terrains in ageing and old age. Soc. Sci. Med. 71, 1513–1519. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.07.022

Jong Gierveld, J. D., and Peeters, A. (2003). The interweaving of repartnered older adults' lives with their children and siblings. Ageing Society 23, 187–205. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X02001095

Karlsson, S. G., and Borell, K. (2002). Intimacy and autonomy, gender and ageing: living apart together. Ageing Int Fall 27, 11–26. doi: 10.1007/s12126-002-1012-2

Katz, S. (1996). Disciplining Old age: The Formation of Gerontological Knowledge. Knowledge: Disciplinarity and Beyond. Charlottesville, VA: University Press of Virginia.

Kimmel, D., Rose, T., and David, S. (2006). Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Aging. New York, NY; Chichester: Columbia University Press.

Klärner, A., and Knabe, A. (2016). “Tradierter pragmatismus in der privaten lebensführung: die entkopplung von ehe und familie in ostdeutschland [Traditional pragmatism in private life: the decoupling of marriage and family in east Germany],” in Der Osten: Neue Sozialwissenschaftliche Perspektiven auf Einen Komplexen Gegenstand Jenseits von Verurteilung und Verklärung, eds S. Matthäus and D. Kubiak (Wiesbaden: Springer VS), 45–69.

Klesse, C. (2007). “Heteronormativität und qualitative Forschung. Methodische Überlegungen [Heteronormativity and qualitative research. Methodological considerations],” in Heteronormativität: Empirische Studien zu Geschlecht, Sexualität und Macht, eds J. Hartmann, C. Klesse, P. Wagenknecht, and B. Fritzsche (Wiesbaden: VS-Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften), 35–51.

Koren, C. (2015). The intertwining of second couplehood and old age. Ageing Soc. 35, 1864–1888. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X14000294

Kroh, M., Kühne, S., Kipp, C., and Richter, D. (2017). Einkommen, soziale Netzwerke, Lebenszufriedenheit: Lesben, Schwule und Bisexuelle in Deutschland [Income, Social Networks, Life Satisfaction: Lesbians, Gays and Bisexuals in Germany] (DIW Wochenbericht No. 35). Berlin.

Kuchler, B., and Beher, S. (eds) (2014). Soziologie der Liebe: Romantische Beziehungen in theoretischer Perspektive [Sociology of Love: Romantic Relationships in a Theoretical Perspective] (1. Aufl.). Suhrkamp Taschenbuch Wissenschaft. Berlin: Suhrkamp.

Langer, P. C. (2017). Gesundes Altern schwuler Männer: Kurzbericht zum Stand der Internationalen Forschung [Healthy Aging of Gay Men: A Brief Report on the State of International Research]. Köln. Available online at http://schwuleundalter.de/download/gesundes-altern-schwuler-maenner/

Lenz, K. (2006). Soziologie der Zweierbeziehung: Eine Einführung [Sociology of the Couple Relationship: An Introduction] (3., überarbeitete Auflage). Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften/GWV Fachverlage GmbH Wiesbaden. Available online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-531-90669-0 doi: 10.1007/978-3-531-90669-0

Lottmann, R., Lautmann, R., and Castro Varela, M. d. M. (eds) (2016). Homosexualität_en und Alter(n) [Homosexuality_ies and aging]. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien.

Matthäus, S., and Kubiak, D. (eds) (2016). Der Osten: Neue sozialwissenschaftliche Perspektiven auf einen komplexen Gegenstand jenseits von Verurteilung und Verklärung [The (German) East: New Social Science Perspectives on a Complex Object Beyond Condemnation and Transfiguration]. Wiesbaden: Springer VS. Available online at https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-658-06401-3#about

Métrailler, M. (2018). Paarbeziehungen bei der Pensionierung: Partnerschaftliche Aushandlungsprozesse der nachberuflichen Lebensphase [Pair relationships at retirement: Partnership-based negotiation processes in the post-work phase of life]. Wiesbaden: VS Springer. Available online at https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007%2F978-3-658-18679-1#about

Neysmith, S. M., and Aronson, J. (2012). Global aging and comparative research: pushing theoretical and methodological boundaries. J. Aging Studies 26, 227–231. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2012.02.001

Pugh, A. J. (2017). “Transformationen der Arbeit und das flexible Herz [Transformations of work and the flexible heart],” in Geschlecht und Gesellschaft. Geschlecht im flexibilisierten Kapitalismus? Neue UnGleichheiten, eds I. Lenz, S. Evertz, and S. Ressel (Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden), 109–130.

Richter, A. S. (2018). Intersektionalität und Anerkennung: Biographische Erzählungen älterer Frauen aus Ostdeutschland. Weinheim Basel: Beltz Juventa.

Settersten, R. A., and Angel, J. L. (eds) (2011). Handbook of Sociology of Aging. New York, NY; Heidelberg, London: Springer Science and Business. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-7374-0

Statistisches Bundesamt (2016). Familie, Lebensformen und Kinder: Auszug aus dem Datenreport 2016 [Family, Living arrangements and Children: Excerpt from the Data Report 2016]. Available online at https://www.destatis.de/DE/Publikationen/Datenreport/Downloads/Datenreport2016Kap2.pdf?__blob=publicationFile

Traunsteiner, B. S. (2016). “Gleichgeschlechtlich l(i)ebende Frauen im Alter. Aspekte von lesbischem Paarbeziehungsleben in der dritten Lebensphase [Same-gender l(o)iving women in old age. Aspects of lesbian couple relationship life in the third phase of life],” in Homosexualität_en und Alter(n), eds R. Lottmann, R. Lautmann and M. d. M. Castro Varela (Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden), 163–178.

Van Dyk, S. (2015). Soziologie des Alters [Sociology of Aging]. Einsichten Themen der Soziologie. Bielefeld: Transcript-Verlag.

Walgenbach, K. (2012). Intersektionalität - Eine Einführung. [Intersectionality -An Introduction]. Available online at www.portal-intersektionalität.de

Keywords: aging, older couples, sociology of aging, aging in close relationship, critical gerontology

Citation: Piel J and Robra B-P (2018) Reconstructing Research About Close Relationships in Old Age: A Contribution From Critical Gerontology. Front. Sociol. 3:36. doi: 10.3389/fsoc.2018.00036

Received: 08 October 2018; Accepted: 09 November 2018;

Published: 29 November 2018.

Edited by:

Andrzej Klimczuk, Warsaw School of Economics, PolandReviewed by:

Daniela Soares, Centro Interdisciplinar De Ciências Sociais (CICS.NOVA), PortugalPiedade Lalanda, Universidade dos Açores, Portugal

Copyright © 2018 Piel and Robra. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Julia Piel, SnVsaWEucGllbEBtZWQub3ZndS5kZQ==

Julia Piel

Julia Piel Bernt-Peter Robra

Bernt-Peter Robra