- 1Department of Sociology, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

- 2School of Public Administration, University of Victoria, Victoria, BC, Canada

The rise of the far-right poses a pressing challenge to democratic politics and the democratization of political participation in Western Europe. This paper addresses this issue in the Scandinavian context, examining the importance of welfare chauvinism and gendered citizenship claims in the political rhetoric of the far-right. In so doing, we contribute to a need to examine closely the interplay between gender, citizenship, and welfare politics and the rise of exclusionary and anti-democratic politics. The paper draws on an examination of the party platforms of the three principle far-right-wing parties currently active in Scandinavia: the Danish People's Party, the Norwegian Progress Party, and the Sweden Democrats as well as descriptive statistics on ethnonationalist tendencies among the Scandinavian populations in recent years, retrieved from the International Social Survey Programme's (ISSP) 2013 survey on nationalism. We conclude that the far-right in Scandinavia uses gender and ethno-nationalist claims to simultaneously valorize and challenge egalitarianism in the welfare state while also shoring up exclusionary and anti-democratic claims to citizenship and belonging in the Nordic welfare state.

Introduction

The rise of the far-right poses a pressing challenge to democratic politics and the democratization of political participation in Western Europe. This paper addresses this issue in the Scandinavian context, examining the importance of welfare chauvinism and gendered citizenship claims in driving support for the far-right. In this we contribute to a need to examine closely the interplay between gender, citizenship, and welfare politics and the rise of exclusionary and anti-democratic politics.

There are many recent signs pointing to a resurgence of far-right nationalist politics in Europe (Roodujin, 2015). Far-right parties have had a strong showing in recent elections all across Europe, including in Hungary, Germany, Greece, and France (New York Times, 2016; Kirk and Scott, 2017). This trend is also apparent in the Nordic countries: in the recent Swedish elections, the far-right Sweden Democrats won 17.6% of the vote, up from 12.9% in 2014. The failure of the incumbent Red-Green coalition (the Greens, Social Democrats, and the Left party) to secure a majority, combined with poor showing from the other moderate parties, means that the Sweden Democrats will likely play a disproportionate role in the formation of the new government (Mudde, 2018). Sweden is not unique among the Nordic welfare states in having a strong far-right presence; both the Norwegian Progress Party and Danish People's Party are well-established in their respective political systems, and have significant parliamentary representation (Coman, 2015).

The rise of the far-right in Scandinavia represents a conundrum for scholars examining the resurgence of xenophobia and nationalism in Europe. Despite the rich literature produced on the subject, there is little consensus on what allows for far-right parties to take root and thrive in any particular political and socio-economic context. Scholarship on continental Europe has mainly focused on Western Europe, where far-right political parties have had an established foothold in politics for some time (Betz, 1994; Swyngedouw and Ivaldi, 2001; Mudde, 2007) and are thought to be rooted in the interaction between higher levels of unemployment and high levels of immigration, particularly immigration of unskilled workers from the Global South (Golder, 2003). In Southern Europe, the recent success of the Golden Dawn in Greece as well as the Northern League in Italy has led scholars to examine the links between recessions, austerity policies, and the rise of anti-immigrant and Eurosceptic parties (Ellinas, 2013; Vieten and Poynting, 2016). In this, in spite of different histories and different contexts, researchers have identified common threads of ethnonationalist xenophobia and antiestablishment populism running through the European far-right (Rydgren, 2007; Moffitt, 2015; Vieten and Poynting, 2016).

How do these explanations play out in understanding movements like the Sweden Democrats, the Norwegian Progress Party and the Danish People's Party? Scandinavia, with its low unemployment and moderate levels of immigration, seems to lack the structural conditions that support the growth of the far-right in other parts of Europe. In addition, with the exception of Iceland, Scandinavia emerged relatively unscathed from the 2008 global recession in terms of its social welfare system and social programs, suggesting also that arguments around social polarization and austerity require some nuance (Einhorn and Logue, 2010; Finseraas and Vernby, 2011). Clearly, economistic and structural explanations are not adequate for understanding why far-right movements gain foothold in the Nordic welfare state.

In this paper, we argue that understanding the rise of the far-right in the Nordic welfare states requires attention to the interplay of gender with ethnonationalist politics within the specific context of a cradle-to-grave welfare state. In particular, we point to the gendered dynamics and subtexts of right-wing politics and claimsmaking, as well as to conceptions of citizenship. Among other things, these conceptions position the Scandinavian welfare state as a zero-sum social good that cannot be shared with outsiders, while at the same time framing outsiders as risks to the social contract that has created the welfare state. In this we contribute to a small literature outlining the importance of examining the gendered dimensions of far-right politics in Europe (Vieten, 2016). In addition, this paper contributes to understanding the complex pathways through which right-wing politics can take hold by examining how a strong inclusionary welfare state can provide the context for the emergence of exclusionary politics.

As we argue below, gender is inextricable from these processes. Gendered politics signal the difference between insiders and outsiders (i.e., the gender egalitarianism of the Nordic welfare state that needs to be safeguarded against the influence of immigrants); in other words, gendered politics and gendered meanings provide resonance and content for nativist framings of belonging in Scandinavia (Siim and Meret, 2016). In particular, gendered citizenship—drawing on notions of egalitarianism, social support for families, and high economic participation of women—becomes inflected with ethno-nationalism in the perpetuation of a kind of welfare state chauvinism (Siim, 2008; Lister, 2009). We begin with an overview of our key concepts: gendered citizenship and welfare state chauvinism. We then move on to a discussion of the far-right in Scandinavia, and the prevalence of ethnonationalist tendencies among the Scandinavian populations. We finish with an analysis of the party platforms of the Danish People's Party, the Norwegian Progress Party, and the Sweden Democrats, and a discussion of how these parties are working to rewrite citizen subjectivities within the welfare state.

Data and Methods

The data in this paper are drawn from an examination of the party platforms of the three principle far-right-wing parties currently active in Scandinavia: the Danish People's Party, the Norwegian Progress Party, and the Sweden Democrats. The websites for these three parties were reviewed in detail in order to gather an overall understanding of their various social and fiscal policy positions. All three parties post platform information on their website in English, and in their respective languages; analysis of material in both languages was included. An understanding of texts as discourse moves us past a reading of the texts as existing in a vacuum and allows for situating the texts within their social and political contexts, granting insight into both the language and the meaning of the text. In this way, discourse analysis allows for the study of both the underlying structures and ideologies of the text (Dijk, 2006). Understanding the ideologies underlying party platforms is of key importance, especially given the role played by ideologies in shaping shared social representations of a group, and, as such, their positions and actions (Dijk, 2006). To this end, we conducted a discourse analysis of party materials, working both to decipher the meanings within those texts, and to situate them within the larger political projects being undertaken by these parties.

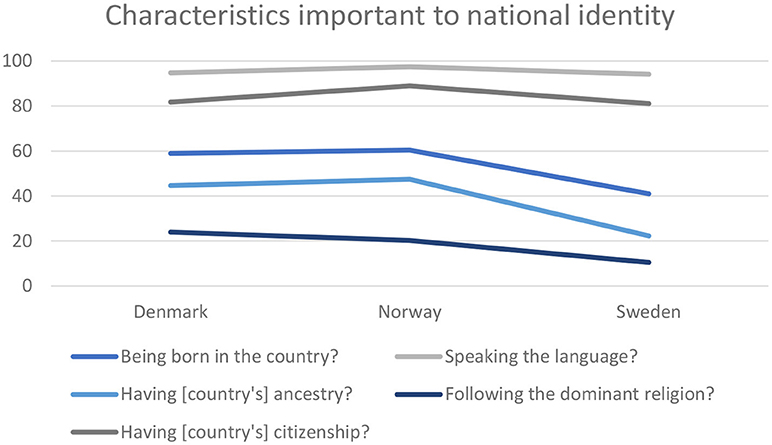

Besides these qualitative data, we also present some descriptive statistics on ethnonationalist tendencies among the Scandinavian populations in recent years. These data were retrieved from the International Social Survey Programme's (ISSP) 2013 survey on nationalism (ISSP Research Group, 2015). The surveys gather information from a nationally representative sample on respondents' understandings of national identity (Brien and Beck, 2015). Respondents were asked how important certain characteristics were for being truly [nationality], including speaking the dominant language, having that country's ethnic ancestry, having citizenship, and following the dominant religion, and being born in the country. Descriptive statistics for these five questions are presented below. Sample sizes from the 2013 ISSP surveys were 1,315 from Denmark, 1,585 from Norway, and 1,090 from Sweden (Brien and Beck, 2015).

Welfare State Chauvinism

Nationalism is a part of the process of constructing a social-political entity: the creation of a collective identity from which a society can be constructed (Breton, 1988). Breton (1988) identifies four basic components of nationalism as an ideology: the principles of inclusion or exclusion; a conception of the “national interest;”comparisons with other groups; and specific views as to the ways in which the social environment can threaten or support the group. Scholars draw a distinction between civic nationalism and ethnonationalism based on modes of inclusion and exclusion to the national identity category (Fozdar and Low, 2015). Ethnically based conceptions of nationalism arise when the society and the institutions that are constructed are based on cultural unity, and the basis for exclusion or inclusion within that society is ethnic (Breton, 1988; Fozdar and Low, 2015). Conversely, civic nationalism ties individuals together through an ideological commitment to civic institutions and government (Fozdar and Low, 2015). That said, civic nationalism is not necessarily more inclusive of diversity than ethnonationalism; rather frameworks can vary in the restrictiveness of their criteria for membership in a collective identity (Fozdar and Low, 2015).

Given that civic nationalism is not inherently more inclusive than ethnic nationalism, the discursive framing of “the Other” plays a significant role in determining the inclusiveness of national identity, whether determined civically or ethnically (Fozdar and Low, 2015). Political parties take part in this discursive work; in order to succeed in the polls and the legislature, parties must convince voters of their ideology. For this to be successful, their frameworks must resonate with the population—discursive work is necessary to ensure that their frames align with individual understandings and values (Snow et al., 1986). With ethnonationalism playing such a prominent role in shaping far-right ideology, one significant task faced by the far right is to marry nationality and ethnicity in the minds of the population. Then, “the Other,” or the “outsider,” becomes defined both ethnically and nationally. That is to say, far-right parties work both to frame the insider/outsider division as ethnically based, and to define the national membership criteria as ethnic. Other scholars studying this issue have drawn connections between citizenship strategies and conceptions of citizenship and belonging; in particular, those nations with closed citizenship regimes tend to conceive of citizenship in ethnic terms, meaning that these ethnic conceptions of belonging can have significant legal ramifications (Wodak, 2013).

One way in which the understanding of outsiders as threats to the well-being of the nation state is practiced is through welfare chauvinism—“a system of collective social protection that is restricted to those belonging to the ethnically defined community who has contributed to it” (Careja et al., 2016, p. 436). One of the key functions of the state is the demarcation of “the people.” That is, the state is integral in determining who belongs within its protective borders, and who does not: only citizens that are recognized by the state are placed within its care (Mann, 1999; Revi, 2012). Welfare states, in particular, draw clear boundaries between citizens and non-citizens because of the wealth of resources being distributed, and the widespread reach of the state into everyday life. Welfare chauvinism, then, occurs when outsiders are understood as threats to the well-being of the people of a welfare state by taking too much of the state resources—specifically, within this framework of anti-immigrant sentiment, they are seen as taking more from the state than they rightfully deserve (Hjorth, 2016). In a context where ethnic criteria are used to determine national belonging, conceptions of “ethnic group outsider” and “non-citizen” converge, so that the rights of citizenship become contingent on ethnonationalist conceptions of belonging.

The freedom of movement in the EU, and the cross-border welfare rights that follow it, have challenged and redefined the traditional relationship between the state and the citizen (Hjorth, 2016). For one, by decoupling the right to social protection from membership to the national political community, cross-border welfare rights have weakened the binding ties of solidarity within territorial nation states (Hjorth, 2016). This has, in certain cases, triggered concerns about “benefit tourism”—the notion that EU migrants are crossing borders for the sole purpose of accessing social services; however, these concerns tend to be restricted to certain kinds of migrants (Hjorth, 2016). That is, rather than a simple dichotomy between co-nationals and foreigners, individuals draw distinctions between different kinds of migrants, largely relying on stereotypes. In this way, the understandings of who are deserving recipients of social protection, and who are not, inherent in welfare chauvinism are shaped by conceptions of difference. Thus, welfare chauvinism is a logical outcome of ethnonationalism: when legitimate access to the services provided by the state is defined ethnically, those who are understood as outsiders will be seen as accessing state services rightfully belonging to (ethnic) nationals. Furthermore, according to Hjorth (2016), welfare chauvinism tends to be triggered by fears of cultural threat, as well as economic scarcity.

This fear of a cultural threat posed by ethnic outsiders takes on decidedly gendered dimensions in the West. Families in general, and women in particular, are often seen as key institutions in the transmission of culture and tradition. For this reason, socially conservative policies tend to focus on the protection and preservation of the family, to the point of using the welfare state to promote and enshrine the heteronormative family (Sherry and Ornstein, 2014; Hausermann, 2018; Williams, 2018). Thus, (perceived) threats to the welfare state often correspond with (perceived) threats to the family, playing as important a role as it does in socially conservative ideology. Concerns for the preservation of the culture, as articulated by far-right and socially conservative groups, imply a sense of threat from some group too different. In the case where the nation comes to be defined ethnically, so too do these threatening differences. In fact, the concerns about “benefit tourism” common in Western Europe underscore the importance of perceptions of difference in evaluations of deservingness in welfare chauvinist ideologies (Hjorth, 2016). The gendered implications here are clear—given the responsibility placed on women in racial ideologies for the maintenance of the racial identity group, they are particular vulnerable to scrutiny and control. Similarly, families, as key cultural institutions, are privileged within the welfare state.

Gendered Citizenship

Building on Marshall's seminal work on citizenship, we understand citizenship to be a complex and multi-layered concept that involves not only the rights that flow from the legally recognized residence within a particular territory, but also identities and statuses that accompany those rights and the processes and actions that realize them (Marshall, 1950, 1964; Turner, 1990; O'Connor, 1993; Somers, 1993; Soysal, 2000; Isin and Turner, 2007; Somers and Roberts, 2008; Isin and Nielsen, 2013). While Marshall cited universalism as a fundamental attribute of citizenship, it is clear that citizenship in practice is both particularistic and differentiated (Soysal, 2000). Birthplace, gender, race and ethnicity, language, legal status all interplay to create hierarchies and inequalities between and amongst citizens. Indeed, citizenship's potential to create inequalities has received much more recent scholarly attention than the reverse; in the European context, inequalities around birthplace, race and ethnicity have been shown to be associated with significant “thinning” of citizenship rights, especially for migrants and immigrants.

That being said, Marshall's fundamental contribution—that citizenship and citizenship rights were layered around three different dimensions of participation and belonging: the political, the civic, and the social, remains the dominant frame through which citizenship is analyzed even today. This is particularly true in terms of scholarship of the Nordic welfare state, which, beginning with Esping-Andersen (1999) has been fundamentally framed around Marshall's interventions. More recent work on the welfare state, developing in large part as a critique to the gender blindness of Esping-Andersen's work, has examined the gendered frames and subjectivities that constitute citizenship in all its dimensions (social, civic, and political) (Orloff, 1993; Sainsbury, 1999; Lister, 2009; Munday, 2009; Kananen, 2016; Siim and Borchorst, 2017).

Citizenship in the Nordic countries in this literature is characterized by an assumed embrace of key progressive values, such as equality, solidarity, and universalism, and of equal and inclusionary citizenship (Lister, 2009). According to Lister (2009), this emphasis on equality and solidarity translates into a model of citizenship that is more focused on the bonds between citizens than on the bonds between the citizen and the state: in general terms, the welfare state is viewed positively, and seen to be an integral part of citizenship. From a gendered citizenship perspective, the Nordic welfare states have taken different paths than other nations (notably corporate welfare-states like France and Germany, or liberal states like the United Kingdom) in particular through an emphasis on using policy instruments to support the economic participation of women in the workforce as well as creating other conditions for gender equality. More recently, scholars have commented on the apparent move of the Scandinavian welfare states away from a “universal breadwinner model” to a “universal care-giver model;” that is, rather than emphasizing the importance of working for women, state policies work to support both men and women as “citizen-earner/carers” (Lister, 2009, p. 249). One example of this tendency are the “use it or lose it” paternal leave policies common in Scandinavia.

Recently, scholarly attention to the outcomes of these policy interventions for gender equality has focused on the resistance of “glass ceilings” (in terms of career progressions), as well as income differences and occupational gender segregation to change. This work has identified persistent inequalities according to gender as well as family status even in countries that have an explicit policy emphasis on correcting gender inequality (Siim and Borchorst, 2017). While recent scholarship has called for an increased attention to the intersectionalities that might underlie here, there has been comparatively less attention however to the role of race relations, and in particular, nativism and constructions of whiteness, to the politics of citizenship and inclusion in the Nordic states (Siim and Meret, 2016).

Our interest below is in particular on the interplay of race, especially whiteness, with gender, in the construction of citizenship identities within radical right wing parties in Scandinavia. As (Mulinari and Neergaard, 2014), p. 20) point out, gender provides a rich resource through which to mobilize ethno-nationalist capital. Research on the creation of racial identities—white racial identities included—has pointed to the key role assigned to women. As (potential) mothers, women are made to bear responsibility for the continuation of the racial/ethnic group, so that their bodies are placed under significant control and scrutiny (Bonnett, 1998). This point is particularly salient in the Nordic countries, where Nordic identity has become so enmeshed with a white racial identity so as to be almost synonymous (Lundström and Teitelbaum, 2017). The hyper-whiteness embodied by Nordic women has produced a specific white femininity, one characterized by norms of respectability, morality, and beauty (Lundström, 2017). In this vein, the conflation of whiteness, Europeanness, and Christianity in the process of creating white, European racial identities imparted a higher moral position to whiteness (Bonnett, 1998). That said, these white racial identities are always in crisis, as they depend primarily upon the differentiation of white from non-white (Bonnett, 1998). This means that significant work must go into the maintenance of white racial identities, both at the individual and the societal level.

The European Far-right

In keeping with the post-materialist thesis—where generational changes in material security have led to a shift in values—new political parties have sprung up across the political spectrum (Inglehart and Rabier, 1986). On the right, this has meant the emergence of new far-right parties, primarily focused on the perceived threats of immigration, unemployment, and crime (Veugelers, 2000). This demand for new far-right parties is further evidenced by a rise in general political apathy and distrust of institutions. Younger voters, in particular, are less likely today to be invested in liberal ideals of democracy than in prior cohorts (Foa and Mounk, 2016). Furthermore, the rise in anti-democratic sentiment has been especially marked among the wealthiest citizens of liberal democracies, indicating that the support for illiberal politics is being led by the young and wealthy, not only the disempowered and disenfranchised (Foa and Mounk, 2016). Given the wide variety of ideologies and party positions held by Western far-right parties, we will be relying on the general definition offered by Rydgren (2007): far-right parties are generally characterized by xenophobic ethnonationalism and anti-elitist populism, and their platforms tend to be embedded in a kind of sociocultural authoritarianism that stresses the importance of putting the collective good above individual rights.

Despite the wealth of research on the subject, there is little consensus in the literature over the ideal structural conditions for the growth of a far-right political movement. For instance, research on the political system has shown that proportional representation, in particular, benefits the far-right, as does a system with a weak conservative party (Carter, 2002; Arzheimer and Carter, 2006). Far parties can also have a lasting impact on their political systems, namely by polarizing the party structure (Harmel and Svasand, 1997; Bale, 2003). Beyond that, scholars have found that immigration and unemployment are key structural factors that contribute to the success of the far-right in Europe. However, there remain significant questions about the role of these two factors; in particular, scholars disagree on the importance of objective levels of immigration and unemployment in promoting demand for far-right politics (Golder, 2003). For one, Cochrane and Nevitte (2012) have argued that unemployment rates only predict anti-immigrant sentiment in countries where there is already a far-right political presence. Essentially, they argue that existing far-right parties use high rates of unemployment to support their anti-immigrant agendas, arguing that immigrants are to blame for the lack of work available to native-born citizens (Cochrane and Nevitte, 2012). In this vein, Lamprianou and Ellinas (2017) found that economic grievances do not directly predict far-right voting; rather economic grievances erode public trust in political institutions, leading voters to look for alternatives such as far-right parties.

The legacy of European fascism is also apparent in the rhetoric and beliefs of the far-right. For one, far-right parties work toward a vision of the population as a single political identity, bound together by a shared ethnic, cultural, linguistic, and/or religious history, so as to make inclusion within a national group based on ethnic criteria. In general, the far-right favors an ethnic understanding of citizenship (jus sanguinis) over a territorial one (just soli) (Rydgren, 2007). This insistence on the importance of language and culture to nationality is not restricted to the far-right: of the 27 European Union member states, only six had citizenship/language tests in 2006, compared to 18 in 2013 (Wodak, 2013). In this vein, European far-right parties tend to promote “ethno-pluralism,” which entails the notion that, in order to preserve the unique characters of each nation state, their peoples must be kept separate (Rydgren, 2007). In fact, the far-right tends to position group outsiders as threats to the well-being of the ethnically homogenous population. In general, this is manifested in a distrust of immigrants and international elites—in fact, many far-right parties promote the idea that the nation state is being weakened by undesirable immigration and the overinvolvement of international players in the economy (Rydgren, 2007). For this reason, most scholars agree that there is a common thread of ethnonationalist xenophobia and antiestablishment populism running through the European far-right (Rydgren, 2007). Thus, in the absence of definitive structural conditions, it would seem that culture has a significant role to play in the emergence of far-right parties.

The Scandinavian Far-right

The Sweden Democrats, the Danish People's Party, and the Norwegian Progress Party have all experienced a remarkable level of electoral success over the past decades. In the last election, held in the summer of 2015, the Danish People's Party took over 20% of the vote, giving them the largest share of the vote of any right-wing party (Nardelli and Arnett, 2015). Following the 2018 Swedish election, the Sweden Democrats hold 62 seats in the parliament; although they are far from forming a majority, the coalitionary nature of Swedish government means that the Sweden Democrats will likely exercise a significant amount of power in the new parliament (Mudde, 2018). The Norwegian Progress Party, for its part, joined in a coalition government following the 2013 election in Norway (Nardelli and Arnett, 2015). At one level, this success is, in part, due to the proportional representation electoral systems popular in the Scandinavian countries which, unlike the first past the post system practices in the UK and Canada, allow parties with sparse, geographically widespread support to gain a foothold in parliament (Nardelli and Arnett, 2015). At another level, however, the success of the far-right in these countries is also reflective of changing attitudes and preferences among the electorate in these countries. That said, given the lack of other structural factors supporting the growth of the far-right, such as high unemployment, it is remarkable that these parties have enough support across their respective countries to form a powerful political entity.

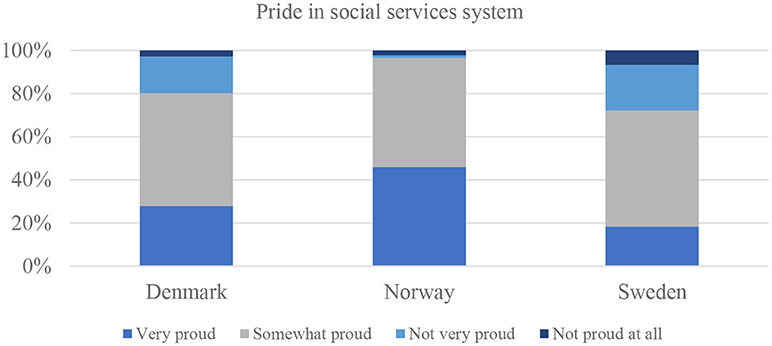

The Scandinavian countries—Norway, Sweden, and Denmark—are characterized by strong welfare states. In Esping-Anderson's (1990) typology, the Scandinavian states typify the social democratic welfare state; these states push for the highest level of equality, rather than simply an equality of minimum needs. In these states, the state assumes responsibility for a large range of social rights, and takes over the burden of care of the population (Swenson, 2004). As Table 1 shows, data from the International Social Survey Programme's 2013 survey on National Identity (ISSP Research Group, 2015) show that the social services system in Denmark, Norway and Sweden are overwhelmingly popular with their respective populations (see Table 1). As the delivery of social services is a key feature of the welfare state, their popularity can be taken as a measure of popular support for the welfare state. The far-right in these three countries is unusually supportive of the welfare state; while some far-right groups rail against big government, the Scandinavian parties argue for a strong welfare state whose protections are limited to an ethnically bounded national polity (Nordensvard and Ketola, 2015). This feature alone distinguishes the Scandinavian far right from far-right politics in North America, that tend to feature a strong distrust of the state (Lyons, 2017).

The lack of key structural conditions—such as high immigration rates, or high unemployment—makes the strength of the Scandinavian far-right parties of particular interest. Unemployment is low in all three countries: in early 2018, the unemployment rate was 4.8% in Denmark, 4% in Norway, and 6.2% in Sweden (Eurostat, 2018). Furthermore, immigration into the Scandinavian states is on par with, or lower than, other European countries. For example, over one fifth of the German population were first or second-generation immigrants, while only roughly 17.3% of the Norwegian population is first or second generation, as is roughly 13% of the Danish population (Thomasson, 2017; Statbank Denmark, 2018; Statistics Norway, 2018). Rates of immigration to Sweden are higher than in the other two countries, in part due to more relaxed immigration laws (Jakobsen et al., 2018), so that, in 2017, about 2.5 million of the population of roughly 10 million in Sweden were first or second-generation immigrants (Statistics Sweden, 2017). Given research that suggests that high immigration and high unemployment—specifically, high immigration in a context of high unemployment—are key structural conditions for the success of far-right parties, the success of the Scandinavian far-right suggests that there must be something over and above structural conditions allowing for their success. One possible explanation is that ideological undercurrents of ethnonationalism and welfare chauvinism among the Scandinavian populations provide a fertile ground for the growth of far-right parties, regardless of the structural conditions of the country in question.

Ethnonationalist Sentiments Among the Scandinavian Populations

Ethnonationalism involves the imposition of ethnic criteria for belonging to a national identity group; that is, when national identity is conceptualized as ethnically bounded. In this scenario, criteria for belonging tend to be linguistic, cultural, religious, and ethnic (Fozdar and Low, 2015). Table 2 below presents data from the International Social Survey Programme's 2013 survey on national identity, which asked respondents from across Europe about their opinions on what was important for national identity (Brien and Beck, 2015).

Data from the Danish, Norwegian, and Swedish surveys show that speaking the language was generally seen as the most important marker of national identity; citizenship, too, was seeing as highly important. Birthplace and ethnic ancestry were also seen as fairly important overall, however to a lesser degree than language and citizenship. This trend, however, does not hold for religion, which only about a fifth of the respective population found to be important for establishing the national identity (ISSP Research Group, 2015). This points to a specific kind of ethnonationalist sentiment, one where national identity is centered around a shared language and history, and around a sense of belonging, and obligation, to the state (in the form of citizenship), and one where religion plays and insignificant role. The secularity of the Scandinavian states may explain the little importance placed on religion by the survey respondents.

In conclusion, our analysis here shows that there is a strong foundation of ethno-nationalist conceptions of citizenship and identity amongst Norwegians, Danes, and Swedes. We now move to a qualitative analysis of party platforms of the far-right political parties in each country, with an eye to identifying the interplay between gender, ethno-nationalism and race in creating anti-immigrant and exclusionary framings of citizenship and belonging.

Party Platforms: Findings

The Danish People's Party, the Sweden Democrats, and the Norwegian Progress Party are all clear on their view of the family as the foundation of society, and advocate state protection and promotion of children's interests, in particular their right to both parents. The Danish People's Party even goes so far as to say that “[t]he ties of intimacy between husband and wife and children and parents are the pillars of Danish society and of great importance for the future of the country.” (2002). Furthermore, the Sweden Democrats (2018) take a strong stance against child marriage, and forced marriage, advocating, like the (Danish People's Party, 2002), for an age limit of 24 years on marriage for foreign nationals. The Sweden Democrats also push natalist policies, such as government allowances for parents, and argue against the “use it or lose it” paternal leave common in Scandinavia. The Sweden Democrats (2018) clarify that their stance on the family comes from their view of it as an important carrier of culture and tradition. In this vein, all three parties worry about the threats to their cultures posed by immigration, advocation “fair and sustainable” immigration policies that control levels of immigration and allow for integration and assimilation of immigrants (Danish People's Party, 2002; Norwegian Progress Party, 2017; Sweden Democrats, 2018).

In line with their reputations, all three Scandinavian far-right parties maintain anti-immigrant stances. The Danish People's Party says it perhaps the clearest, declaring on their website that “Denmark is not an immigrant-country and never has been. Thus, we will not accept transformation to a multiethnic society” (2002). The three parties emphasize restricting immigration to those immigrants who would respect the laws, cultures, and traditions of Sweden, Norway, or Denmark, and who would be easily assimilated (Danish People's Party, 2002; Norwegian Progress Party, 2017; Sweden Democrats, 2018). In this vein, both the Sweden Democrats (2018) and Norwegian Progress Party (2017) advocate for strict linguistic and cultural requirements for citizenship, even arguing for mandatory social orientation. The Sweden Democrats (2018), on their website, also call for a crackdown on illegal immigration. In this vein, all three parties are united in their calls for a strengthened security state, arguing for stricter laws, harsher punishments, more surveillance, and a stronger police force (Danish People's Party, 2002; Norwegian Progress Party, 2017; Sweden Democrats, 2018).

The three parties are vocal about their support for the welfare state, advocating for strong health care and social services. Common to all three is also the idea that care for children, for the elderly, and for persons with disabilities is a national responsibility, and should be taken seriously (Danish People's Party, 2002; Norwegian Progress Party, 2017; Sweden Democrats, 2018). However, the Norwegian Progress Party (2017), Sweden Democrats (2018) clearly argue for a privileging of Swedish citizens within the welfare state; they both go so far as advocating that access to social services be linked to citizenship status.

As the only country out of the three to still have a state church, the Danish People's Party are the clearest of the three parties about the importance of Christianity to their society. In the English language section of their website, the Danish People's Party (2002) argues that Christianity is crucial to Danish culture, and critical for the development of freedom, openness and democracy in any country. Interestingly, the Danish People's Party (2002) also stands in support of the monarchy, displaying a fundamentally conservative social stance. All three parties, however, advocate for Islamophobic policies, although at times covertly. For example, the Sweden Democrats propose banning halal slaughter of animals under the guise of preventing animal cruelty. Similarly, they also argue for a special category of punishment for the perpetrators of “honor crimes,” a clear allusion to religiously motivated crimes (Sweden Democrats, 2018). Moreover, the Sweden Democrats (2018) contend that, while life for sexual and gender minorities is (and should be) improving in Sweden, the threat to LGTBQ peoples is worst in those parts of the country where Swedish culture is the weakest, and “foreign” cultures are the strongest.

The three parties also all display isolationist tendencies when it comes to foreign affairs. All three are anti-EU, arguing that the EU robs countries of their sovereignty. They also argue that their governments should be doing peacekeeping work so as to allow migrants and refugees to return to their homelands, rather than offering them asylum: the Sweden Democrats (2018) go so far as to say that they “want to stop receiving asylum seekers in Sweden and instead go for real aid for refugees. We want to enable more immigrants turning back to their native countries.” They further propose that the Scandinavian countries need stronger militaries and police, and more secure borders to protect their citizens (Danish People's Party, 2002; Norwegian Progress Party, 2017; Sweden Democrats, 2018). As the Danish People's Party says, “Denmark belongs to the Danes, and its citizens must be able to live in a secure community founded on the rule of law” (2018).

There is a striking similarity between the three parties in their stated goals and positions. All three parties look for a return to a more homogenous, more conservative society. The parties also show consistency in terms of diagnosing social ills and identifying scapegoats: the Sweden Democrats (2018) paint a dystopian picture of Sweden, of its civil society as crumbling and overrun by criminals, terrorists and gangs. Similarly, Norwegian Progress Party (2017) may lament the state of affairs in Sweden, arguing that the only way for Norwegian society to avoid falling into disorder like in Sweden is to place strict limits on immigration. In sum, not only are the Sweden Democrats (2018), Norwegian Progress Party (2017) and the Danish People's Party (2002) alike in their anti-immigrant stances, our examination of their platforms showed them to be closely aligned in their positions on security, on foreign relations, on the role of the family, and on the welfare system.

Discussion

We find that the party platforms for the three main Scandinavian far-right parties—the Danish People's Party, the Norwegian Progress Party, and the Sweden Democrats—present a vision of society with the nuclear family as the foundation; the Sweden Democrats are particularly vocal in the support for the heteronormative nuclear family. All three parties further advocate for strong social support for the family, such as government support for young children, placing the family in a privileged position within the welfare state. Beyond that, all three parties advocate for strong border control, and severe limitations on both the number and the kind of immigrants that should be admitted. They are all vocal on the threat to their respective national cultures posed by excessive levels of immigration, with a special focus on immigrants from non-Christian, non-European, and non-white backgrounds. Coupled with their anti-immigrant stances—party rhetoric tends to frame immigrants as threats to the culture of the nation—their view of the family points to a construction of the ideal citizen as white, middle-class, and heteronormative. We argue that the success of far-right parties is due, at least in part, to a fertile ground of pre-existing ethnonationalist tendencies among the Scandinavian populations. More than that, these pre-existing tendencies have given rise to a unique form of far-right politics: one focused on transforming citizenship within the welfare state. Key to this project is a particular vision of what the citizen and the state are/should be; gender underpins both.

Recently, Elgenius and Rydgren (2018) highlighted the role of anti-immigrant sentiment in driving support for far-right parties. Our analysis confirms this and points to three main frames through which these ideas are refracted and disseminated: first, that immigrants compete with native-born for welfare state resources; second, that immigrants present a critical threat to ethno-national identity; third, that immigrant values pose a threat to social-democratic and progressive values of the Nordic states (Elgenius and Rydgren, 2018). This kind of framing is for instance reflected in the Norwegian People's Party platform that highlights “Western” values of freedom and opportunity Norwegian Progress Party (2017) and suggests that Norway welcome only those who conform with those values.

These framings are intimately linked to popular understandings that merge belonging to a nation-state with having access to valuable social rights: for instance, Nordensvard and Ketola (2015) argue that the Swedish far-right, in particular, exemplifies a populist discourse that brings together the nation state and the welfare state. In general, Scandinavian far-right parties work to reframe the welfare state as belonging to a particular, distinct political community, where inclusion within the state's protective framework is dependent on ethnic and national belonging (Nordensvard and Ketola, 2015). In our analysis, we found that both Norwegian Progress Party (2017) and the Sweden Democrats (2018) advocate for tying access to certain welfare state services to citizenship, and for ending what they refer to as “special benefits” for immigrants Norwegian Progress Party (2017).

We find, however, in addition, and following on recent work (see in particular Siim and Meret, 2016; Siim and Borchorst, 2017) that gendered understandings are used to amplify these frames, and create urgency and resonance to far-right claims. Interestingly, however, gendered understandings of citizenship are used to contradictory purposes in far-right rhetoric: First, to use Nordic values of gender egalitarianism in a way so as to create hierarchical distinctions between Nordic citizens and others; at the same time, the party platforms also reject the Nordic brand of egalitarianism, in favor of more traditionalist constructions of women's role in society and politics.

This first use of gender can be seen, for one, in rhetoric among the parties that gender inequality and oppression is a feature of minority groups, whereas it has been eliminated in mainstream society (see also Siim, 2008). The Danish People's Party, 2002) has an official stance against forced marriage, while failing to differentiate it from arranged marriage. This is a useful rhetoric device for these groups as it portrays women (of color) as victims of their own culture, but also sets up a dichotomy between Danish culture and other cultures, providing the former with a kind of progressive moral superiority. Another example here can be seen in the “cultural racism” of the Sweden Democrats (Mulinari and Neergaard, 2014); racism is given the cloak of gender egalitarianism through claims of the need to protect Swedish women from immigrants and migrants. At the same time, embedded in the party platforms of all parties are policy ideas that reject contemporary egalitarianism: for instance, the removal of mandatory “father” days as part of parental leave policies, as well as policies to give biological fathers' rights prior to the birth of a child (Sweden Democrats, 2018). Interestingly, these parties are not overtly homophobic—the Sweden Democrats (2018) even go so far as to argue that gender and sexuality and inborn and that individuals should not be harassed for their sexual orientation—but still strongly advocate policies that support and promote heteronormative family structures.

However, perhaps the most prominent theme of our analysis is the interplay and intersection between gendered claims and ethno-nationalist claims to citizenship. It is important here to emphasize some of the unique features of the Scandinavian far-right, in particular in comparison to other European members of the far-right political family. There are, first of all, key differences in terms of immediate structural triggers of far-right mobilization, as we discussed above. Second, as also mentioned earlier, the Scandinavian far-right has emerged in the context of a strong social welfare state and a strong social and political attachment to that state. A final point of difference, although one less explored in this paper, has to do with the historical backdrop against which the far-right in Europe currently operates. In continental Europe, new far-right parties must contend with the living history and ongoing memorialization of a traumatic fascist past. The citizen-nation framework is an important element of the memorializations of this past; official and unofficial accounts of the 2nd world war in Europe must account not just for the role of fascist state actors but also the role of the citizenry. How memorialization activities of the 2nd world war provide context for the emergence of far-right remains somewhat understudied, but there is emerging research on how these memorializations provide the context for both official and unofficial re-casting of citizens' roles in fascist regimes as well as “forgetful” renderings of the 2nd world war (Forest et al., 2004; Fisher, 2007). Examples here include both Hungary and Poland, where there has been a significant official campaign to rewrite the role of citizenry during the Nazi years (Barna, 2015; Grunwald, 2017). These histories however, play both a less prominent and a different role in Nordic memorializations of the twentieth century. The Scandinavian far-right, is in this way, a new discourse on Nordic belonging and citizenship, one that is less bound by both direct and mediated memories of European fascism, racism, and genocide.

Far-right groups do not exist outside of existing citizen-nation frameworks—that is, they are not free from the influences of existing conceptions of the role of state and of citizen in the welfare state. The welfare state structure implies a particular formation of citizenship—one where the lines of obligation between state and citizen are reciprocal. Welfare states, like the Scandinavian ones, work to create reciprocal lines of obligation between state and citizen by introducing laws and social programs which all citizens pay into, and are dependent upon, all the while working to instill feelings of obligation in the population (Esping-Anderson, 1990). In this way, the state structure shapes understanding of citizenship—both the rights attached to it, and the responsibilities. The state also performs important work in drawing the line between group insiders and outsiders—between citizens and foreigners (Revi, 2012). Social citizenship grants citizens access to services and goods administered by the state irrespective of their market capacities (Korpi, 2006). Because of this, the distribution of services, and social rights, serves to draw boundaries around “the people,” distinguishing between citizens and non-citizens; only those recognized by the state are placed under its protection (Revi, 2012). The sheer wealth of resources and services available within the welfare state mean that these boundaries are especially clear. When conceptions of national belonging based on ethnic criteria are institutionalized, then, citizenship, in turn, becomes based on ethnic criteria. When far-right parties engage in discourse of welfare chauvinism, they are not only advocating for a restriction of kinds of individuals that can access the social services system; rather, they are also advocating for a restricted understanding of citizenship within the welfare state, one that is based upon ethnic understandings of national belonging. We find by appealing to gendered values, in particular valorizing gender egalitarianism while simultaneously rewriting gender platforms into more traditionalist and heteronormative conceptions, far-right parties use gender as signal or trope for exclusionary, and ethno-nationalist politics.

Conclusion

In 2015, one in six people living in Sweden were born outside of the country, a 67% increase since 2000; half of those are from non-European countries (Statistics Sweden, 2017). Norway and Denmark have seen similar, albeit smaller increases in foreign-born residents over the same time period. Understanding the conditions and contexts for the emergence of far-right politics in response to this trend is clearly important and pressing, as is understanding how far-right politics place more generally a challenge to democratic politics in Northern Europe.

Far-right politics in the Nordic welfare states are characterized by a strong element of welfare state chauvinism, in which social rights are posited as rare, valuable, and zero-sum, and that their distribution must therefore rest on having appropriate ethno-nationalist credentials. This is an interesting phenomenon; whereas in other contexts, far-right politics seek to dismantle the state, in Scandinavia, far-right politics appear to seek to reconceptualize citizenship rights along ethno-nationalist dimensions, while at the same time deepening and thickening these rights. Given the pre-existing importance of ethnic markers to national identity in Nordic countries, however, the main work done by the far-right in these countries is not so much to convince them of the importance of ethnic markers in national identity, but of the threat to the welfare state posed by “outsiders.”

Gendered conceptions of citizenship—who belongs, what constitutes belonging, and what web of mutual obligations exist between states and citizens—are key to far-right politics in Scandinavia. Far-right parties in Scandinavia emphasize the thickness of the relationships between the state and the citizen, but they impose ethnic and gendered criteria on those relationships. Outsiders, especially those of suspect origins (that is not European or Christian) are positioned as undeserving of the social protections of the state by dint of their social distance from the “ideal” (white) citizen. This tactic is integral to the success of these parties in Scandinavia: instead of threatening the welfare state, the far-right in these countries frames itself as the defender of the welfare state against outside forces.

The far-right in Scandinavia thus uses gender and ethno-nationalist claims to simultaneously valorize and challenge egalitarianism in the welfare state while also shoring up exclusionary and anti-democratic claims to citizenship and belonging in the Nordic welfare state. The case of the emergence of far-right politics in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark, illustrates that even strong states that are ostensibly formed around inclusionary politics can provide the context for the emergence of exclusionary politics and rhetoric. In this, the Scandinavian nations form a sort of exception to the pathways taken by right-wing parties in Southern Europe or in the United Kingdom and the United States. Whereas, in these states, there is a growing consensus that far-right politics has grown out of social and economic rupture and political polarization, the Nordic case illustrates that ethno-nationalism can also provide fodder for far-right movements on their own. In addition, within the context of a cradle-to-grave welfare state, inclusionary citizenship discourse could be used to justify exclusionary politics, by emphasizing the importance of shared history and shared ethno-national identity to the access of valuable social rights. Our focus was on how gendered language in their political platforms was used to amplify and strengthen ethno-nationalist conceptions of citizenship. The limitations of this study include however its focus on the party platforms of political parties; there is a pressing need to understand the complex ways in which the messaging of these parties is taken up and understood by citizens of these states, and to understand the contexts through which these claims may find resonance.

Author Contributions

MF completed the quantitative analysis and the bulk of the qualitative analysis and conducted the literature review for right-wing activism in Europe and welfare state chauvinism. HH contributed the literature review around gender and citizenship and to the qualitative analysis. Both authors are equally responsible for the framing of the paper, the writing, editing, and direction.

Funding

This work was supported by Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada Insight Grant, Grant No. 435-2016-0642.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Arzheimer, K., and Carter, E. (2006). Political opportunity structures and right-wing extremist party success. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 45, 419–443. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6765.2006.00304.x

Bale, T. (2003). Cinderella and her ugly sisters: the mainstream and extreme right in Europe's bipolarising party systems. West Eur. Polit. 26, 67–90. doi: 10.1080/01402380312331280598

Barna, I. (2015). Teaching about and against hate in a challenging environment in hungary: a case study. Casopis za Kritiko Znanosti 260, 272–283. Available online at: https://search.proquest.com/openview/befd219fc0c137ee19352e8a3e0a3c38/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=237824

Bonnett, A. (1998). Who was white? The disappearance of non-European white identities and the formation of European racial whiteness. Ethnic Rac. Stud. 216, 1029–1055. doi: 10.1080/01419879808565651

Breton, R. (1988). From ethnic to civic nationalism: English Canada and Quebec. Ethnic Rac. Stud. 11, 85–102.

Brien, P., and Beck, K. (2015). GESIS-Variable Reports No. 2015/35: ISSP-National Identity III Variable Report. International Social Survey Programme Research Group. Cologne: Leibniz Institute for the Social Sciences.

Careja, R., Elmelund-Praesteker, C., Klitgaard, M. B., and Larsen, E. G. (2016). Direct and indirect welfare chauvinism as party strategies: an analysis of the Danish People's Party. Scan. Polit. Stud. 39, 435–457. doi: 10.1111/1467-9477.12075

Carter, E. L. (2002). Proportional representation and the fortunes of right-wing extremist parties. West Eur. Polit. 25, 125–146. doi: 10.1080/713601617

Cochrane, C., and Nevitte, N. (2012). Scapegoating: unemployment, far-right parties and anti-immigrant sentiment. Compar. Eur. Polit. 12, 1–32. doi: 10.1057/cep.2012.28.

Coman, J. (2015, July 26). How the Nordic far-right has stolen the left's ground on welfare. The Guardian. Available online at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/jul/26/scandinavia-far-right-stolen-left-ground-welfare

Danish People's Party (2002). The Party Program of the Danish People's Party. Available online at: https://danskfolkeparti.dk/politik/in-another-languages-politics/1757-2/

Dijk, T. A. V. (2006). Ideology and discourse analysis. J. Polit. Ideol. 11, 115–140. doi: 10.1080/13569310600687908

Einhorn, E. S., and Logue, J. (2010). Can welfare states be sustained in a global economy? Lessons from Scandinavia. Polit. Sci. Q. 125, 1–29. doi: 10.1002/j.1538-165X.2010.tb00666.x

Elgenius, G., and Rydgren, J. (2018). Frames of nostalgia and belonging: the resurgence of ethno-nationalism in Sweden. Eur. Soc. doi: 10.1080/14616696.2018.14297

Ellinas, A. A. (2013). The rise of golden dawn: the new face of the far-right in Greece. South Eur. Soc. Polit. 18, 543–565. doi: 10.1080/13608746.2013.782838

Esping-Anderson, G. (1990). The three political economics of the welfare state. Int. J. Soc. 20, 92–123.

Eurostat (2018). Unemployment by Sex and Age – Monthly Average. Eurostat, the Statistical Office of the European Union, Labour Market Unit. Available online at: http://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=une_rt_mandlang=en

Finseraas, H., and Vernby, K. (2011). What parties are and what parties do: partisanship and welfare state reform in an era of austerity. Soc. Ecol. Rev. 6, 613–638. doi: 10.1093/ser/mwr003

Fisher, J. (2007). Disciplining Germany: Youth, Reeducation, and Reconstruction After the Second World War. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press.

Foa, R. S., and Mounk, Y. (2016). The danger of deconsolidation: the democratic disconnect. J. Democr. 27, 5–17. doi: 10.1353/jod.2016.0049

Forest, B., Juliet, J., and Karen, T. (2004). Post-totalitarian national identity: public memory in Germany and Russia. Soc. Cul. Geogr. 5, 357–380. doi: 10.1080/1464936042000252778

Fozdar, F., and Low, M. (2015). They have to abide by our laws and stuff: ethnonationalism masquerading as civic nationalism. Nat. Nat. 21, 524–543. doi: 10.1111/nana.12128

Golder, M. (2003). Explaining variation in the success of extreme right parties in Western Europe. Comp. Polit. Stud. 36, 432–466. doi: 10.1177/0010414003251

Grunwald, H. (2017). “Genocide memorialization and the Europeanization of Europe,” in The Use and Abuse of Memory, ed C. Karner (New York, NY: Routledge), 23–41.

Harmel, R., and Svasand, L. (1997). The influence of new parties on old parties' platforms: the cases of the progress parties and conservative parties of Denmark and Norway. Party Polit. 3, 315–340.

Hausermann, S. (2018). The multidimensional politics of social investment in conservative welfare regimes: family policy reform between social transfers and social investment. J. Eur. Public Pol. 25, 862–877. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2017.1401106.

Hjorth, F. (2016). Who benefits? Welfare chauvinism and national stereotypes. Eur. Union Polit. 7, 3–24. doi: 10.1177/1454116515607371

Inglehart, R., and Rabier, J.-R. (1986). Political realignment in advanced industrial society: from class-based politics to quality of life politics. Govern. Oppos. 21, 456–479.

Isin, E. F., and Turner, B. S. (2007). Investigating citizenship: an agenda for citizenship studies. Citizenship Stud. 11, 5–17. doi: 10.1080/13621020601099773

ISSP Research Group (2015). International Social Survey Programme: National Identity III - ISSP 2013. GESIS Data Archive, Cologne. ZA5950 Data file Version 2.0.0

Jakobsen, V., Korpi, T., and Lorentzen, T. (2018). Immigration and integration policy and labour market attainment among immigrants to Scandinavia. Eur. J. Popul. 1–24. doi: 10.1007/s10680-018-9483-3.

Kananen, J. (2016). The Nordic Welfare State in Three Eras: From Emancipation to Discipline. London: Routledge.

Kirk, A., and Scott, P. (2017). June 19. French election results: how the parliament looks as Macron's party claims an astounding majority. The Telegraph. Available online at: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/new/2017/06/19/french-election-results-new-parliament-looks-macrons-new-party/

Korpi, W. (2006). Power resources and employer-centered approaches in explanations of welfare states and varieties of capitalism: protagonists, consenters, and antagonists. World Polit. 58, 167–206. doi: 10.1353/wp.2006.0026

Lamprianou, I., and Ellinas, A. A. (2017). Institutional grievances and right-wing extremism: Voting for Golden Dawn in Greece. South Eur. Soc. Polit. 22, 43–60. doi: 10.1080/13608746.2016.1207302

Lister, R. (2009). A Nordic nirvana? Gender, citizenship, and social justice in the Nordic welfare states. Soc. Polit. 16, 242–278. doi: 10.1093/sp/jxp007

Lundström, C. (2017). Embodying exoticism: gendered nuances of Swedish hyper-whiteness in the United States. Scand. Stud. 89, 179–199. doi: 10.5406/scanstud.89.2.0179

Lundström, C., and Teitelbaum, B. R. (2017). Nordic whiteness: an introduction. Scan. Stud. 89, 151–158. doi: 10.5406/scanstud.89.2.0151

Lyons, M. N. (2017). Ctrl-Alt-Delete: The Origins and Ideology of the Alternative Right. Somerville, MA: Political Research Associates.

Mann, M. (1999). The dark side of democracy: the modern tradition of ethnic and political cleansing. New Left Rev. I/235, 18–45.

Marshall, T. H. (1964). “Class, citizenship and social development,” in Democracy: A Reader, eds R. Blaug, and J. Schwarzmantel (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press), 203–206.

Moffitt, B. (2015). How to perform crisis: a model for understanding the key role of crisis in contemporary populism. Govern. Opp. 50, 189–217. doi: 10.1017/gov.2014.13

Mudde, C. (2007). Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe, Vol. 22. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mudde, C. (2018). Septamber 10. Sweden's election is no political earthquake despite far-right gains. The Guardian. Available online at: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/sep/10/sweden-election-no-political-earthquake-bloc-politics

Mulinari, D., and Neergaard, A. (2014). We are sweden democrats because we care for others: exploring racisms in the swedish extreme right. Eur. J. Women's Stud. 21, 43–56. doi: 10.1177/1350506813510423

Munday, J. (2009). Gendered citizenship. Soc. Compass 3, 249–266. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9020.2008.00187.x

Nardelli, A., and Arnett, G. (2015). June 19. Why are anti-immigrant parties so strong in the Nordic states? The Guardian. Avaialble online at: https://www.theguardian.com/news/datablog/2015/jun/19/rightwing-anti-immigration-parties-nordic-countries-denmark-sweden-finland-norway

New York Times (2016, December 4). Europe's rising far right: A guide to the most prominent parties. Available online at: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2016/world/europe/europe-far-right-political-parties-listy.html.,

Nordensvard, J., and Ketola, M. (2015). Nationalist reframing of the Finnish and Swedish welfare states – The nexus of nationalism and social policy in far-right populist parties. Soc. Pol. Admin. 49, 356–375. doi: 10.1111/spol.12095

Norwegian Progress Party (2017). Information in English. Available online at: https://www.frp.no/english

O'Connor, J. S. (1993). Gender, class and citizenship in the comparative analysis of welfare state regimes: theoretical and methodological issues. Br. J. Soc. 44, 501–518.

Orloff, A. S. (1993). Gender and the social rights of citizenship: the comparative analysis of gender relations and welfare states. Am. Sociol. Rev. 303–328.

Revi, B. (2012). T.H. Marshall and his critics: reappraising ‘social citizenship’ in the twenty-first century. Citizenship Stud. 18, 452–464. doi: 10.1080/13621025.2014.905285

Roodujin, M. (2015). The rise of the populist radical right in Western Europe. Eur. View. 14, 3–11. doi: 10.1007/s12290-015-0347-5

Rydgren, J. (2007). The sociology of the radical right. Ann. Rev. Sociol. 33, 241–262. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.33.040406.131752.

Sherry, S., and Ornstein, A. (2014). The preservation and transmission of cultural values and ideals: challenges facing immigrant families. Psychoanal. Inquiry 34, 452–462. doi: 10.1080/07351690.2013.846034

Siim, B. (2008). “Dilemmas of citizenship: tensions between gender equality and cultural diversity in the Danish welfare state,” in Gender equality and welfare politics in Scandinavia: The Limits of political Ambition, eds K. Melby, A. B. Ravn, and C. C. Wetterberg (Bristol: The Policy Press), 149–165.

Siim, B., and Borchorst, A. (2017). “Gendering European welfare states and citizenship: revisioning inequalities,” in Handbook of European Social Policy, eds P. Kennett and N. Lendvai-Bainton (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing), 60–75.

Siim, B., and Meret, S. (2016). “Right-wing populism in denmark: people, nation and welfare in the construction of the ‘Other’,” in The Rise of the Far-Right in Europe, eds G. Lazaridis, G. Campani, and A. Benveniste (London: Palgrave Macmillan), 109–136.

Snow, D. A., Rochford, J.r,. E. B, Worden, S. K., and Benford, R. D. (1986). Frame alignment processes, micromobilization, and movement participation. Am. Soc. Rev. 51, 464–481.

Somers, M. R. (1993). Citizenship and the place of the public sphere: law, community, and political culture in the transition to democracy. Am. Soc. Rev. 58, 587–620

Somers, M. R., and Roberts, C. N. (2008). Toward a new sociology of rights: a genealogy of “buried bodies” of citizenship and human rights. Annu. Rev. Law Soc. Sci. 4, 385–425. doi: 10.1146/annurev.lawsocsci.2.081805.105847

Soysal, Y. N. (2000). Citizenship and identity: living in diasporas in post-war Europe?. Ethnic Rac. Stud. 23, 1–15. doi: 10.1080/014198700329105

Statbank Denmark (2018). Population at the First Day of the Quarter by Age, Sex, Region, Time and Ancestry. Statistics Denmark. Available online at: http://www.statbank.dk/10021

Statistics Norway (2018). Immigrants and Norwegian-Born to Immigrant Parents. Statistics Norway, Division for Population Statistics. Available online at: https://www.ssb.no/en/befolkning/statistikker/innvbef

Statistics Sweden (2017). Number of Persons by Region, Foreign/Swedish Background. Statistics Sweden, Statistical Database. Available online at: http://www.statistikdatabasen.scb.se/pxweb/en/ssd/START__BE__BE0101__BE0101Q/UtlSvBakgGrov/table/tableViewLayout1/?rxid=c5eed20f-68de-4d2a-881e-1fa8b3c8ad6f#

Sweden Democrats (2018). About Us. Available online at: https://sd.se/english/

Swenson, P. A. (2004). Varieties of capitalist interests: power, institutions, and the regulatory welfare state in the United States and Sweden. Stud. Am. Polit. Dev. 18, 1–29. doi: 10.1017/S0898588X0400001X

Swyngedouw, M., and Ivaldi, G. (2001). The extreme right utopia in Belgium and France: the ideology of the flemish vlaams blok and the french front national. West Eur. Polit. 24, 1–22. doi: 10.1080/01402380108425450.

Thomasson, E (2017, August 1). Immigrant Population hits new high in Germany. Reuters World News. Available online at: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-germany-immigration/immigrant-population-hits-new-high-in-germany-idUSKBN1AH3EP?fbclid=IwAR3rS9xUOsMC6HDRA5G-zh4LNVO_xvPu7Fm5hEOU06IjHF_gvEWuJB_HaIk.

Turner, B. S. (1990). Outline of a theory of citizenship. Sociology 24, 189–217. doi: 10.1177/0038038590024002002

Veugelers, J. W. P. (2000). Right-wing extremism in contemporary France: a ‘silent counterrevolution’?. Sociol. Q. 41, 19–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-8525.2000.tb02364.x

Vieten, U. M. (2016). Far-right populism and women: the normalisation of gendered anti-Muslim racism and gendered culturalism in the Netherlands. J. Inter. Stud. 37, 621–636. doi: 10.1080/07256868.2016.1235024

Vieten, U. M., and Poynting, S. (2016). Contemporary far-right racist populism in Europe. J. Inter. Stud. 37, 533–540. doi: 10.1080/07256868.2016.1235099

Williams, H. H. (2018). From family values to religious freedom: conservative discourse and the politics of gay rights. Nw Polit. Sci. 40, 246–263. doi: 10.1080/0793148.2018.1449064

Keywords: right-wing activism, welfare state, scandinavia, gender, citizenship

Citation: Finnsdottir M and Hallgrimsdottir HK (2019) Welfare State Chauvinists? Gender, Citizenship, and Anti-democratic Politics in the Welfare State Paradise. Front. Sociol. 3:46. doi: 10.3389/fsoc.2018.00046

Received: 02 October 2018; Accepted: 20 December 2018;

Published: 14 January 2019.

Edited by:

Jana Günther, Technische Universität Dresden, GermanyReviewed by:

Daniela Soares, Centro Interdisciplinar De Ciências Sociais (CICS.NOVA), PortugalMargaret Grogan, Chapman University, United States

Copyright © 2019 Finnsdottir and Hallgrimsdottir. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Helga Kristin Hallgrimsdottir, aGtiZW5lZGlAdXZpYy5jYQ==

Maria Finnsdottir

Maria Finnsdottir Helga Kristin Hallgrimsdottir

Helga Kristin Hallgrimsdottir