- 1Department of Public Relations and Strategic Management Communication, College of Media and Communication, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX, United States

- 2The State University of New York (SUNY) Brockport, Brockport, NY, United States

Facebook is the most popular social media platform and often used by news organizations to distribute content to broad audiences. Features of this online news environment, especially user-generated comments shown to news consumers, have the potential to induce audience perceptions of hostile media bias. This study furthers investigation into the influence of exposure to Facebook comments and news topics on consumers. Using a sample of U.S. adult Facebook users (N = 1,274), this work utilized a 2 (likeminded comments or disagreeable comments) × 2 (story topic of requiring COVID-19 vaccines to receive a monetary bonus or maintain employment) between-subjects experimental design. While controlling for the influence of partisanship, this work further proves that features of the Facebook environment uniquely influence news audience perceptions of neutral news content. Specifically, findings indicate that news story topic can influence perceptions of bias. Further, topic and comment exposure interacted, demonstrating the intensity of story topic and likeminded comments enhance hostile media perceptions.

Introduction

Deployment of the COVID-19 vaccine across the United States (U.S.) began in early 2021, with an initial focus on older adults and vulnerable populations. By June 2021, the vaccine became available to all adults and children aged 12 and above. According to public health experts, vaccination remains the best way to end the global COVID-19 pandemic, especially as society attempts to stay open. However, while public health experts and public figures encouraged vaccination, segments of the U.S. population remained skeptical. Just as mask-wearing was divisive, the subsequent vaccines were further politicized (Albrecht, 2022; Bolsen and Palm, 2022).

Media outlets and public service campaigns joined medical professionals' efforts to increase vaccine uptake. Non-profit organizations such as the Advertising Council launched multi-million-dollar campaigns targeting a wide variety of communities to help them overcome the hesitancy and skepticism that characterized the vaccine conversation (Montgomery, 2021). These carefully tailored pro-vaccination campaigns made their way into mainstream news and social media, successfully gaining traction among wider audiences. One of a journalist's primary functions is to equip citizens with the information they need to make critical decisions. During the COVID-19 pandemic this included information about this new virus and how to prevent it (i.e., the COVID-19 vaccine; Dean, 2021).

In the United States, 53% of adults get their news from social media; online news was and continues to be a major source of COVID-19 and vaccine information (Shearer, 2021). However, the online news environment created by social media platforms like Facebook introduces the influence of other users into the picture, shaping the transfer of information in a new way. For example, a Facebook user is subject to viewing a teaser posted by news outlets to promote a particular news story while simultaneously encountering comments posted by other users before viewing the article.

As a result of technological changes, news outlets increasingly use social media for news dissemination and news consumers are exposed to comments posted by others before they read a news article. Therefore, this work is theoretically guided by the hostile media bias. The first aim of this study is to experimentally test whether comments, appearing below a Facebook post promoting a news story, influence perceptions of bias. In addition, this work aims to test whether the influence of comments vary across news stories related to different tactics used to encourage COVID-19 vaccines. Results provide further evidence of the hostile media phenomenon in social media contexts and expand the theoretical knowledge and breadth of application.

Literature review

Theoretical foundation: hostile media bias

Hostile media bias is a phenomenon that occurs when audiences perceive media coverage as being biased against their opinion (Perloff, 2015). In their seminal experimental investigation into the theory, Vallone et al. (1985) exposed participants to a neutral news segment depicting the 1982 invasion of Lebanon by Israel to establish hostile media bias as an ongoing phenomenon. Results indicated that participants who harbored strong partisan views or were highly invested in an issue perceived media coverage as biased against their own view or sentiment, a finding that subsequent hostile media bias researchers later replicated (e.g., Vallone et al., 1985; Gunther, 1992; Dalton et al., 1998). While this early work was instrumental in establishing the hostile media phenomenon, the focus only on strong partisans may been seen as a shortcoming.

A growing body of empirical work testing hostile media bias has observed a variety of mediums, including newspaper, television, and social media, across a wide range of content with the added notion that sources (e.g., channels or outlets) may impact perceptions of hostile media bias (Gearhart et al., 2020). Past researchers have attempted to determine what factors can contribute to hostile media bias as it may influence other important communication behaviors such as audiences' explorations of social alienation and political dialogue (Tsfati, 2007; Barnridge and Rojas, 2014; Perloff, 2015). Identified factors have included the likelihood to assimilate, accept face-value information, or scrutinize information that opposes partisan positions, along with common social identity precursors (e.g., Lord et al., 1979; Perloff, 1989; Giner-Sorolla and Chaiken, 1994). For example, Tsfati (2007) found that minority perceptions of media bias might heighten minority opinion holders' feelings of alienation or social exclusion. Further, Barnridge and Rojas (2014) found perceived bias in media content “makes people attempt to ‘correct' perceived ‘wrongs' by voicing their own opinions in the public sphere” (p. 135).

Studies on hostile media bias have turned their attention toward online news stories from both mainstream outlets and blogs and found consistent results (e.g., Gunther and Liebhart, 2006; Kim, 2015). Perloff (2015) claims a gap in scholarly understanding of how hostile media bias occurs via online platforms that remain limited or nascent at best. Specifically, there is an urgent need for research focusing on user-generated comments paired with online news. User comments may influence perceptions due to the ability of third-party audience members to shape others' perceptions of a news story or its editorial frame and may ultimately contribute to perceptions of an implied lean to the story depending on the audience's pre-conceived sentiments (Gearhart et al., 2021). Moreover, studies found that user comments may exaggerate elements that appear within news segments and may further guide certain cognitive processes (Lee and Tandoc, 2017). Individuals who perceive the media as hostile to their own views will attempt to resolve this perceived hostility by discussing political issues more often, including discussion in comment sections under a news story (Barnridge and Rojas, 2014). As such, user-generated comments are an important and essential consideration of this current study, providing a unique avenue for the extension of hostile media bias research.

Building on these observations, it is necessary to examine whether elements of online news consumption platforms can further influence hostile media perceptions. Facebook, one of the most popular social media platforms used by nearly 70% of American adults, is a popular place for users to share and consume news content (Auxier and Anderson, 2021). Elements of this platform, including user-generated comments, are displayed to news consumers and have the potential to differently influence perceptions of hostile media bias (Tsfati, 2007; Barnridge and Rojas, 2014; Perloff, 2015; Gearhart et al., 2020, 2021). Further, comments may have varying influence of comments across politically related, controversial issue topics. Therefore, the current study examines whether encounters with user comments influence perceptions of news content across topics.

Journalistic objectivity: perceptions of bias and ethical values

One other important aspect to consider when examining hostile media bias influenced by user-generated comments is the role of journalistic objectivity. In an effort to maintain fairness and civility, the U. S. Federal Communications Commission (F.C.C.) concluded in 1949 that the duty of broadcast licenses was to cover controversial issues in a fair and balanced manner, also known as The Fairness Doctrine (Ruane, 2011). This duty required that broadcasters “devote a reasonable portion of broadcast time to the discussion and consideration of controversial issues of public importance” (Caldera, 2020, p. 11), making available for the expression of opposing perspectives that stem from responsible elements within controversial issues. Abolished in 1987 by the F.C.C., The Fairness Doctrine was perceived as hindering the types of democratic debate it was intended to promote (Hershey, 1987). However, it was not formally rescinded until 2011 (Matthews, 2011). The decision to abolish The Fairness Doctrine has been attributed to increases in conservative talk radio, which gained popularity during the 1980s and 1990s. Among other forms of journalistic activity, political talk radio was rationalized in 1987 to fall under first amendment protections of speech, despite mostly advocating for a certain partisan viewpoint (Hagey, 2011). This discussion is relevant to today's social media environment, which is driven by capitalistic forces and allows controversial and problematic discourse to accompany legitimate news content, potentially influencing audiences. This threatens perceptions of journalistic objectivity, which has long been the gold standard.

Furthermore, especially in times of crisis, news outlets and journalists are expected to go beyond simply covering the news to help the public make sense of what is going on, solve or better the situation, and even cope (Grusin and Utt, 2005; Bressers and Hume, 2012). Bias, a dimension of credibility, and credibility itself have long been subjects of research (e.g., Rouner et al., 1999; Fico et al., 2004; Gil de Zúñiga et al., 2018). For example, in a vaccine context, Gunther et al. (2012) found anti-vaccination partisans perceived pro-vaccine content as more unfavorably biased. Moreover, research has shown that different factors can affect the public's perceptions of bias in a news story, from the story's internal elements such as structure (Fico et al., 2004) to external elements such as the comments accompanying the news article (Weber et al., 2019), or social media news posts (Kümpel and Unkel, 2020).

Perceptions of ethical values in journalism

Closely related to journalistic objectivity, another fundamental aspect of journalism is the assumption that each journalist adheres to personal values, attitudes, and philosophical principles that affect how the profession is carried out and ultimately perceived. Journalists also see themselves as governed by outside social influences, such as professional norms, the law, and intrinsic motivations (Voakes, 1997). Journalistic codes of ethics come into play when ethical dilemmas arise. Yet, it remains the responsibility of each journalist to abide by these guidelines at an individual level by drawing their own lines between what they consider to be ethical and not (Holt, 2012). However, it is not enough for journalists alone to be ethical. The way publics perceive the ethics of news media is also very important. For example, Culver and Lee (2019) found that liberals were more likely to perceive news media as ethical than conservatives and, consequently, trusted media more than their conservative counterparts. Even more critically, they found that audiences' participation in the news (e.g., sharing the story with a friend or commenting on a story) was positively connected to perceptions of ethical performance. More recently, according to a Pew Research Center study, Americans ranked journalists' ethical standards below doctors, police, and clergy (Gottfried et al., 2020). Moreover, Democrats were found “far more likely” than Republicans to believe journalists have high or very high ethical standards (Gottfried et al., 2020).

Journalism and the struggle to maintain an unbiased perception

While journalistic objectivity and ethical values remain critical to the profession, modern journalism continues to struggle with its audience's migration to online spaces and its potential effect on their perceptions. As such, a two-pronged ethical tension has reared its head. While traditional journalism values accuracy, verification, balance, gatekeeping, and impartiality, online journalism seeks to emphasize immediacy, transparency, partiality, and post-publication corrections when or if needed. However, fake news, disinformation, political propaganda, and other creative forms of masking content as “Journalism” remain a direct threat to democracy as it unveils new frontiers for free-speech advocates, among them policymakers, pundits, and professional journalists (Wagner and Boczkowski, 2019). Furthermore, digital technology and ruthless politics alongside commercial exploitation of mass disseminated content, whether in audio, print, broadcast, or digital formats, has contributed to concerns pertaining to bias, ethics, and the foundations of classical democratic procedures for the foreseeable future (White, 2017). Finally, according to Wagner and Boczkowski (2019), perceptions of the media landscape include: (a) carrying a negative connotation of the overall perception of the quality of news reporting; (b) ever-existing distrust of news circulation, specifically as it appears on social media; and (c) an overall concern about the effects of these trends mainly on the perceived information habits of others. Considering these historical backgrounds and current concerns, this study aims to discern how ethical participants perceive stories to be.

Issue topics: COVID-19 vaccine requirements

Controversial news story topics are ideal for applying the hostile media bias phenomenon in experimental settings. Thus, COVID-19 vaccination is a suitable topic for application and empirical testing. In particular, the implementation of tactics used to encourage vaccine uptake in the workplace have been and continue to be highly contested in the U.S. Since not all Americans took the free and widely available vaccines, private employers took additional measures to encourage the COVID-19 vaccine. For instance, some employers in the U.S. began offering incentives for recipients of the COVID-19 vaccination (Terrell, 2021), while others started to mandate that employees get vaccinated to remain in their positions (Messenger, 2021). However, both practices were deemed controversial in different ways by some publics. Thus, the two types of vaccine requirements (i.e., requiring COVID-19 vaccination to receive a monetary bonus or requiring a COVID-19 vaccination to keep one's job) are used in the current study as controversial topics suitable for testing the hostile media phenomenon.

The controversial nature of news content about COVID-19 vaccination requirements is suitable for testing the hostile media phenomenon. Furthermore, the review above demonstrates how the features of Facebook might inherently expose news consumers to factors that may induce hostile media perceptions, such as user-generated comments. Therefore, the following research questions and hypothesis guide this study:

RQ1: Do perceptions of story bias vary as a function of exposure to one-sided Facebook user comments and news story topic?

H1: Perceptions of reporting bias will vary as a function of exposure to both one-sided Facebook user comments and news story topic.

RQ2: Do perceptions of ethical reporting vary as a function of exposure to one-sided Facebook user comments and news story topic?

Method

Participants and procedures

Using a 2 (likeminded comments or disagreeable comments) × 2 (story topic of requiring vaccines to receive a monetary bonus or maintain employment) between-subjects experimental design, the current study recruited adult Facebook users to participate. Despite the abundant amount of user-generated data online (e.g., social media feedback on the pandemic), the use of alternative approaches is an important and necessary requirement for testing and advancing the hostile media bias phenomenon. Thus, an experimental research design allows for conditions to be created that provide a controlled and manipulated environment for Facebook news audiences. Furthermore, these conditions represented the various situations that were being experienced among employees in the U.S. at the time. With approval from the university-affiliated Institutional Review Board, the current study recruited adult Facebook users to participate using Dynata, a professional survey company contracted to collect a nationwide sample of U.S. adults (N = 1,274). The survey was fielded from May 9, 2021 to May 11, 2021. Dynata solicited potential respondents and asked them to voluntarily participate in exchange for credit to be used in their internal reward system. The online survey was hosted on a Qualtrics account associated with the university, and the data collection instrument did not collect any identifying information from participants.

Stimulus

Upon agreeing to participate, respondents were asked several questions about their personal media use and psychological attributes, and then were randomly assigned to one of the two topics, either (a) offering monetary bonuses to employees who receive a COVID-19 vaccine; or (b) requiring employees to receive a COVID-19 vaccine to maintain their employment. After answering questions about their own opinions on the topic (i.e., either offering monetary bonuses to employees for receiving a COVID-19 vaccine or requiring employees to receive a COVID-19 vaccine to maintain their employment), participants were exposed to a Facebook news teaser—a post advertising a news story, from the Associated Press (A.P.), a news outlet audiences perceive as a balanced source (AllSides, 2021; Media Bias Fact Check, 2021).

Respondents were asked a series of questions that led them to reveal their own opinion on the randomly assigned topic before then being randomly assigned to a news teaser with comments that either agreed or disagreed with their stance on the topic. The Facebook post included a neutral headline and image. It featured three comments from users that were intentionally manipulated to represent likeminded (i.e., agreeable) or dissimilar (i.e., disagreeable) opinions on the issue as compared to the participant's opinion.

After reviewing the Facebook post and comments, each participant was directed to read a neutral news article on their assigned topic. The news stories that served as stimuli were created for this study by the authors, who have expertise in news writing and A.P. style. Stimuli content was created to present balanced content on either approach taken to increase the rate of COVID-19 vaccinations (i.e., the use of monetary incentives to employees who receive a vaccine or requiring employees to receive a vaccine to maintain their job). The only difference between the two stories was the topic, title, and in-text mentions of the respective approach used to increase vaccinations. Otherwise, the stimuli were standardized to maintain the story content across the two news stories. Once the news story was read, participants were then asked questions to assess their perceptions of story bias, reporting bias, and ethical reporting.

Measures

Perceived story bias

Mirroring measurement from Fico et al. (2004), this item assesses the individual perception of news story bias. Measurement was accomplished with three items, which asked the participants to think about the news article they had just read and indicate how they felt the article provided information on the debated topic. The items included: (a) the amount of space and prominence the story gave to each side; (b) the strength of the arguments included for each side; and (c) the quality of the sources cited for each side. Responses were recorded using a 7-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly opposes requiring COVID-19 vaccines to _______ to 7 = strongly favors requiring COVID-19 vaccines to ______). The blank space was replaced with the randomly assigned topic condition (i.e., either receive a bonus or maintain employment). All items were found to be reliably related and were subsequently merged to form an index (α = 0.84; M = 4.38, SD = 1.12).

Reporting bias

Following previously validated measurement from Gunther and Schmitt (2004), this study examined multiple dimensions of perceived bias in reporting. Using items modified to fit the goals of this work, participants were asked three questions, including: (a) Do you feel that the news story was greatly biased against or in favor of your opinion about requiring vaccination to work?; (b) Do you feel that the writer of the news story was greatly biased against or in favor of your opinion about requiring vaccination to work?; and (c) Do you feel that the news outlet that published this story was greatly biased against or in favor of your opinion about requiring vaccination to work? Participant responses were collected with a 7-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly biased against my opinion _______ to 7 = strongly biased in favor of my opinion _______). The blank space was replaced with the randomly assigned topic condition (i.e., either receive a bonus or maintain employment). All items were found to be reliably related and were subsequently merged to form an index (α = 0.84; M = 4.04, SD = 1.16).

Perceived ethics

Perceptions of how ethically the news story was presented to readers were measured with the use of a single item. After reading the assigned article, participants were asked, “Did the article present _________ as unethical or ethical?” Responses were collected with a 7-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly unethical to require vaccines to _______ to 7 = strongly ethical to require vaccines to ______). The blank was replaced with the assigned topic (i.e., either receive a bonus or maintain employment) condition (M = 4.26, SD = 1.40).

Demographics

The average respondent was found to be 61.25 years old (SD = 15.70), and the slight majority were male (52.3%). Regarding educational status, the majority reported having completed between a 2-year and a 4-year college degree (M = 4.29, SD = 1.55). Most considered themselves to be between moderately conservative and independent in terms of their political ideology (1 = very conservative to 7 = very liberal) (M = 3.67, SD = 1.82). Concerning the race/ethnicity of respondents, the majority self-reported themselves as White/Caucasian (88.3%) and the estimated household income was found to range from $60,000 to under $70,000 (1 = <$20,000 to 10 = $100,000 or more) (M = 6.20, SD = 3.22).

Results

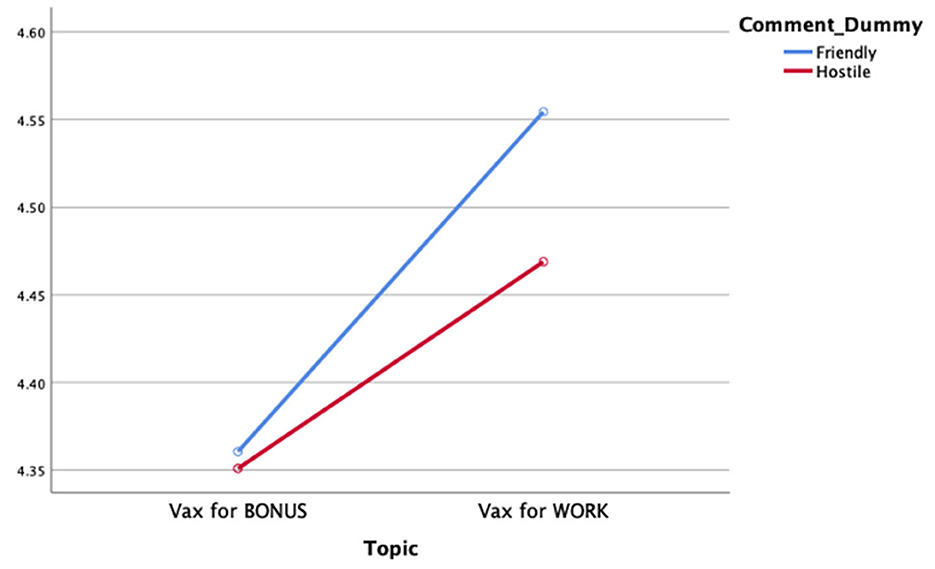

RQ1 asked whether perceptions of news story bias vary as a function of exposure to one-sided Facebook comments and news story topic. Data analysis revealed no main effect of exposure to one-sided Facebook comments on perceptions of story bias [F(1,849) = 0.38, p = ns; ηp2 = 0.00]. However, as seen in Figure 1, data analysis demonstrated a significant main effect of news story topic on perceived bias [F(1,849) = 5.12, p = 0.04; ηp2 = 0.01]. Review of associated means demonstrated that stories about requiring vaccinations to maintain employment are perceived to have a higher level of bias within the story (M = 4.51, SD = 1.16) than do stories about offering monetary incentives for receiving the vaccine (M = 4.35, SD = 1.08). No interaction effect was identified.

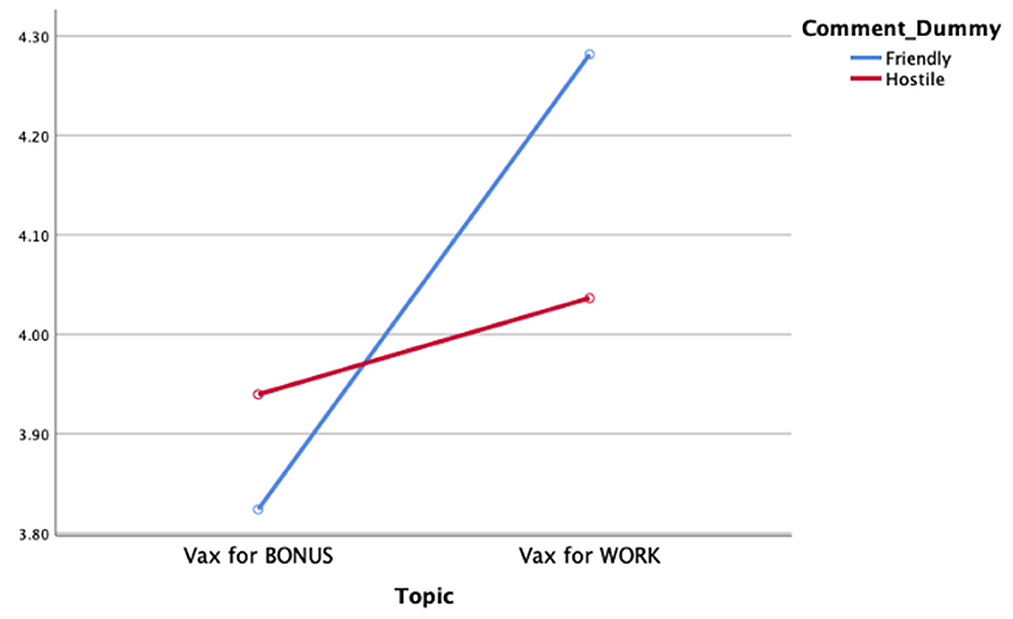

H1 predicted that perceptions of reporting bias will vary as a function of exposure to both one-sided Facebook user comments and news story topic. Data analysis revealed no main effect of exposure to one-sided Facebook comments on perceptions of story bias [F(1,851) = 0.65, p = ns; ηp2 = 0.001]. Data analysis revealed a significant main effect of news story topic on reporting bias [F(1,851) = 11.85, p = 0.001; ηp2 = 0.014]. Review of the associated means demonstrated that stories about requiring vaccinations to maintain employment are perceived to have a higher level of perceived reporting bias (M = 4.15, SD = 1.16) than do news stories about offering monetary incentives for receiving the vaccine (M = 3.87, SD = 1.14).

Data analysis further revealed a significant interaction effect between exposure to one-sided Facebook comments and news story topic on perceptions of reporting bias among audiences [F(1,851) = 5.03, p = 0.03; ηp2 = 0.01]. Review of the associated means indicate that exposure to likeminded comments before reading a story about requiring the vaccine to work result in higher perceptions of reporting bias (M = 4.25, SD = 1.11) than do viewing likeminded comments before the same story (M = 3.82, SD = 1.20), and when exposed to disagreeable Facebook user comments about either requiring vaccines for either employment or receipt of a financial incentive (M = 4.04, SD = 1.28; M = 3.94, SD = 1.06; respectively). Therefore, H1 was partially supported (see Figure 2).

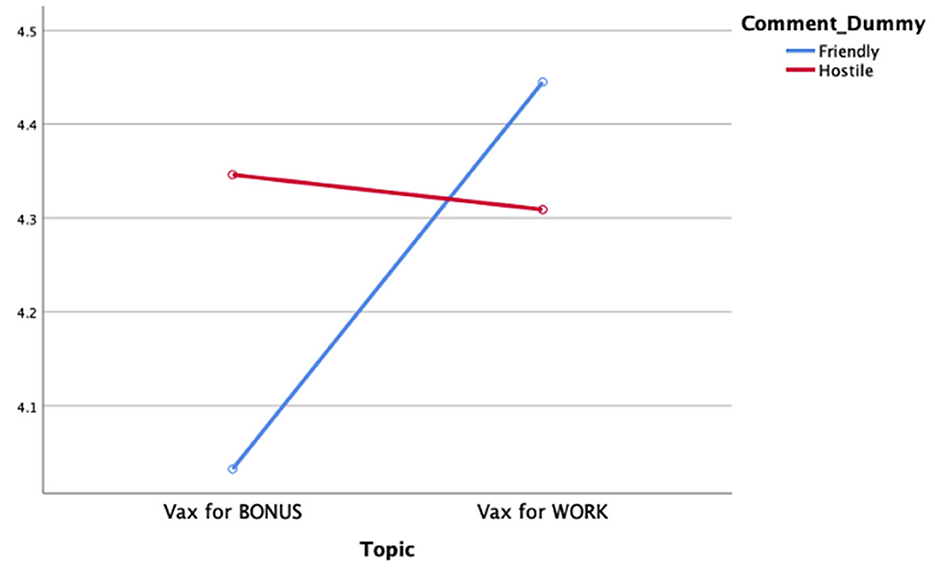

RQ2 asked whether perceptions of ethical reporting vary as a function of exposure to one-sided Facebook user comments and news story topic. Data analysis revealed no main effect of exposure to one-sided Facebook comments on perceptions of ethical reporting [F(1,853) = 0.86, p = ns; ηp2 = 0.001]. Data analysis further revealed a significant main effect of news story topic on perceived ethical reporting [F(1,853) = 3.84, p = 0.04; ηp2 = 0.004]. Review of the associated means demonstrated that stories about requiring a COVID-19 vaccine to keep one's job are perceived to have a higher level of ethical reporting (M = 4.37, SD = 1.47) than were news stories about offering monetary incentives for vaccination (M = 4.18, SD = 1.33).

As seen in Figure 3, data analysis further revealed a significant interaction effect between exposure to one-sided Facebook comments and news story topic on perceptions of reporting bias among audiences [F(1,853) = 5.50, p = 0.02; ηp2 = 0.006]. Review of the associated means indicates that exposure to likeminded comments before reading a story about requiring the vaccine to maintain employment resulted in higher perceptions of ethical news reporting (M = 4.45, SD = 1.37) than when viewing likeminded comments before a story about requiring vaccinations to receive a monetary bonus (M = 4.03, SD = 1.35). However, perceptions of ethical reporting did not differ from other conditions when exposed to dissimilar Facebook comments for stories about requiring vaccines for either employment or receipt of a financial incentive (M = 4.31, SD = 1.55; M = 4.35, SD = 1.30; respectively).

Discussion

The goal of the current study was to investigate how exposure to Facebook user comments can influence news audience perceptions of actual news content. Previous studies have investigated the influence of comments across controversial topics (Arceneaux et al., 2013; Kim, 2015; Gearhart et al., 2021). This project aimed to broaden the theoretical scope by testing whether different parts of the online news experience, like the inclusion of opinionated commentary before reading a neutral news story across different topics, influence one another rather than working in isolation. This work also systematically examines the influence of hostile media bias while removing the influence of partisanship and opinion strength, isolating the influence of comments and news story topic. Furthermore, this study uniquely assesses this variation across COVID-19 vaccine-related topics during the height of the pandemic to investigate responses related to tactics used to encourage vaccinations.

First, results demonstrate that only the more serious story topic directly influences perceptions of bias (i.e., vaccine necessary to keep employment). Specifically, Facebook users who were exposed to a news story about requiring vaccines to maintain one's employment found the news to strongly favor requiring COVID-19 vaccines, regardless of comment condition. However, the same was not true when the news story discussed the topic of requiring a vaccine to receive a financial incentive. Journalists reporting news in mainstream media tend to prioritize objective information, aiming to present a balanced story to audiences (Benham, 2020). In the case of the stories seen here, they were nearly identical, with the only variation concerning the type of requirement (i.e., either required to receive financial bonus or to maintain employment). Therefore, the serious nature of potentially losing one's employment appeared to have stronger implications for audiences. Audience perceptions of reporting bias differed based on the topic of the news story. Higher perceptions of reporting bias indicated that news audiences felt the story itself, the writer, and the news outlet that published the report were biased in favor of their own opinion on the topic (Gunther and Schmitt, 2004). D'Alessio (2003) found that news readers were more likely to view material as biased depending on the topic, especially when the topic was political in nature. In this case, both news stories were politically related. However, the topic with the stronger consequences, potentially facing punishment by losing one's job for refusing the COVID-19 vaccine, was found to induce perceptions of reporting bias.

Results also revealed that user-generated comments influence audience perceptions of news content. That is, exposure to likeminded Facebook comments encouraged perceptions of reporting bias when the news was about requiring COVID-19 vaccines to retain one's current employment. Identifying the influence of user comments on audience perceptions aligns with a growing body of research (e.g., Lee et al., 2018; Prochazka et al., 2018; Gearhart et al., 2020, 2021). More importantly, the identified interaction between exposure to opinion-congruent comments and news on the topic of employment requirements suggests that likeminded comments can enhance perceived bias in favor of one's opinion, especially when seen alongside intense story topics. While the intensity of a news topic may be viewed as a subjective construct often based on perceptions of personal topic importance (Tunney et al., 2021), the severity of losing one's job indicates the seriousness of the subject matter.

The topic of the news story was also found to influence perceptions of ethical reporting. Results regarding perceived reporting bias indicate news audiences found the news article to be more ethical when exposed to Facebook comments expressing compatible viewpoints on the topic of limiting employment to vaccinated individuals. This might be explained by the fact that audiences might perceive vaccine incentives as similar to offering a bribe, thus perceiving the news story about incentives as less ethical. Since this direction has not yet been further explored, the specialized focus on perceptions of ethical news reporting in this study encourages further hostile media bias research to include this concept. Future studies should further explicate the concept of ethical reporting as part of the hostile media phenomenon.

In summary, findings strongly suggest that the hostile media effect remains relevant in social networks. Overall, results align with previous research that has found perceptual biases linked to exposure to Facebook comments seen before viewing news content (Gearhart et al., 2020, 2021). This work may be limited by the quality of the sample, indicating that the Dynata sample may attract an older population of respondents. However, the sample notably features an audience of older Americans reminiscent of those adult U.S. Facebook users consuming news on the platform (Auxier and Anderson, 2021). While the current study supports existent findings regarding the influence of Facebook comments, this work uniquely identifies limitations to this influence that are dependent upon story topic. Specifically, the more intense topic of restricting employment only to individuals who have received the COVID-19 vaccine was found to interact with exposure to likeminded user comments. While this work indicates that the influence of social media comments may vary based on the intensity of news topic, future research directions should further explore how limiting the influence of comments seen before accessing news content to the most controversial issues. Therefore, results demonstrate the broad reach of perceptual biases and extend the theoretical scope. Practically speaking, implications of this work indicate that journalists should be aware of the impact that user-generated comments may have on perceptions of their reporting practices. Furthermore, social media users should consider how user-generated comments may hinder their ability to engage in meaningful dialogue and thoughtful exchanges through these platforms.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Texas Tech University Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

SG led this grant-funded project alongside co-PI, IC, and led the methodological execution and data analysis. AM and SB supported the project through stimulus creation. All authors contributed to planning of the project, including theoretical scope, topic choice, literature review, and discussion. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was completed with grant funding from the Waterhouse Family Institute for the Study of Communication and Society (WFI Grant Number: 20210076). Open access publication fees were supplied by Texas Tech University and the College of Media and Communication at Texas Tech University.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Waterhouse Family Institute for its financial support.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Albrecht, D. (2022). Vaccination, politics and COVID-19 impacts. BMC Public Health 22, 96. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-12432-x

AllSides (2021). Associated Press News Media. Available online at: https://www.allsides.com/newssource/associated-press-media-bias (accessed July 20, 2022).

Arceneaux, K., Johnson, M., and Cryderman, J. (2013). Communication, persuasion, and the conditioning value of selective exposure: like minds may unite and divide but they mostly tune out. Polit. Commun. 30, 213–231. doi: 10.1080/10584609.2012.737424

Auxier, B., and Anderson, M. (2021). Social Media Use in 2021. Pew Research Center. Available online at: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2021/04/07/social-media-use-in-2021/ (accessed July 20, 2022).

Barnridge, M., and Rojas, H. (2014). Hostile media perceptions, presumed media influence, and political talk: expanding the corrective action hypothesis. Int. J. Public Opin. Res. 26, 135–156. doi: 10.1093/ijpor/edt032

Benham, J. (2020). Best practices for journalistic balance: gatekeeping, imbalance and the fake news era. J. Pract. 14, 791–811. doi: 10.1080/17512786.2019.1658538

Bolsen, T., and Palm, R. (2022). Politicization and COVID-19 vaccine resistance in the US. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 188, 81–100. doi: 10.1016/bs.pmbts.2021.10.002

Bressers, B., and Hume, J. (2012). Message boards, public discourse, and historical meaning: an online community reacts to September 11. Am. J. 29, 9–33. doi: 10.1080/08821127.2012.10677846

Caldera, C. (2020). Fact Check: Fairness Doctrine Only Applied to Broadcast Licenses, Not Cable T.V. Like Fox News. U.S.A. Today. Available online at: https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/factcheck/2020/11/28/fact-check-fairness-doctrine-applied-broadcast-licenses-not-cable/6439197002/ (accessed July 20, 2022).

Culver, K. B., and Lee, B. (2019). Perceived ethical performance of news media: regaining public trust and encouraging news participation. J. Media Ethics 34, 87–101. doi: 10.1080/23736992.2019.1599720

D'Alessio, D. (2003). An experimental examination of readers' perceptions of media bias. J. Mass Commun. Quart. 80, 282–294. doi: 10.1177/107769900308000204

Dalton, R. J., Beck, P. A., and Huckfeldt, R. (1998). Partisan cues and the media: information flows in the 1992 presidential election. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 92, 111–126. doi: 10.2307/2585932

Dean, W. (2021). What is the Purpose of Journalism? American Press Institute. Available online at: https://www.americanpressinstitute.org/journalism-essentials/what-is-journalism/purpose-journalism/ (accessed July 20, 2022).

Fico, F., Richardson, J. D., and Edwards, S. M. (2004). Influence of story structure on perceived story bias and news organization credibility. Mass Commun. Soc. 7, 301–318. doi: 10.1207/s15327825mcs0703_3

Gearhart, S., Moe, A., and Holland, D. (2021). Social media users (under)appreciate the news: an application of hostile media bias to news disseminated on Facebook. Newspaper Res. J. 42, 433–448. doi: 10.1177/07395329211047009

Gearhart, S., Moe, A., and Zhang, B. (2020). Hostile media bias on social media: testing the effect of user comments on perceptions of news bias and credibility. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2, 140–148. doi: 10.1002/hbe2.185

Gil de Zúñiga, H., Diehl, T., and Ardèvol-Abreu, A. (2018). When citizens and journalists interact on Twitter: expectations of journalists' performance on social media and perceptions of media bias. J. Stud. 19, 227–246. doi: 10.1080/1461670X.2016.1178593

Giner-Sorolla, R., and Chaiken, S. (1994). The causes of hostile media judgments. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 30, 165–180. doi: 10.1006/jesp.1994.1008

Gottfried, J., Walker, M., and Mitchell, A. (2020). American's Views of the News Media During the COVID-19 Outbreak. Pew Research Center. Available online at: https://www.pewresearch.org/journalism/2020/05/08/americans-are-more-negative-in-their-broader-views-of-journalists-than-they-are-toward-covid-19-coverage/

Grusin, K. E., and Utt, S. H. (2005). “The challenge: to examine media's role, performance on 9/11 and after,” in Media in an American Crisis: Studies of September 11, 2001, eds K. E. Grusin and S. H. Utt (Lanham, MD: University Press of America), 1–12.

Gunther, A. C. (1992). Biased press or biased public? Attitudes toward media coverage of social groups. Public Opin. Quart. 56, 147–167. doi: 10.1086/269308

Gunther, A. C., Edgerly, S., Akin, H., and Broesch, J. A. (2012). Partisan evaluation of partisan information. Commun. Res. 39, 439–457. doi: 10.1177/0093650212441794

Gunther, A. C., and Liebhart, J. L. (2006). Broad reach or biased source? Decomposing the hostile media effect. J. Commun. 56, 449–466. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2006.00295.x

Gunther, A. C., and Schmitt, K. (2004). Mapping boundaries of the hostile media effect. J. Commun. 54, 55–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2004.tb02613.x

Hagey, K. (2011). Fairness Doctrine Fight Goes On. Politico. Available online at: https://www.politico.com/story/2011/01/fairness-doctrine-fight-goes-on-047669 (accessed July 20, 2022).

Hershey, R. D. (1987). F.C.C. Votes Down Fairness Doctrine in 4-0 Decision. The New York Times. Available online at: https://www.nytimes.com/1987/08/05/arts/fcc-votes-down-fairness-doctrine-in-a-4-0-decision.html (accessed July 20, 2022).

Holt, K. (2012). Authentic journalism? A critical discussion about existential authenticity in journalism ethics. J. Mass Media Ethics 27, 2–14. doi: 10.1080/08900523.2012.636244

Kim, M. (2015). Partisans and controversial news online: comparing perceptions of bias and credibility in news content from blogs and mainstream media. Mass Commun. Soc. 18, 17–36. doi: 10.1080/15205436.2013.877486

Kümpel, A. S., and Unkel, J. (2020). Negativity wins at last: how presentation order and valence of user comments affect perceptions of journalistic quality. J. Media Psychol. Theor. Methods Appl. 32, 89. doi: 10.1027/1864-1105/a000261

Lee, E.-J., and Tandoc, E. C. Jr. (2017). When news meets the audience: how audience feedback online affects news production and consumption. Hum. Commun. Res. 43, 436–449. doi: 10.1111/hcre.12123

Lee, T. K., Kim, Y., and Coe, K. (2018). When social media become hostile media: an experimental examination of news sharing, partisanship, and follower count. Mass Commun. Soc. 21, 1–23. doi: 10.1080/15205436.2018.1429635

Lord, C. G., Ross, L., and Lepper, M. R. (1979). Biased assimilation and attitude polarization: the effects of prior theories on subsequently considered evidence. J. Person. Soc. Psychol. 37, 2098–2109. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.37.11.2098

Matthews, D. (2011). Everything You Need to Know About the Fairness Doctrine in One Post. Washington Post. Available online at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/ezra-klein/post/everything-you-need-to-know-about-the-fairness-doctrine-in-onepost/2011/08/23/gIQAN8CXZJ_blog.html (accessed July 20, 2022).

Media Bias Fact Check (2021). Associated Press. Available online at: https://mediabiasfactcheck.com/associatedpress/ (accessed July 20, 2022).

Messenger, H. (2021). From McDonald's to Goldman Sachs, Here are the Companies Mandating Vaccines for All or Some Employees. N.B.C. News. Available online at: https://www.nbcnews.com/business/business-news/here-are-companies-mandating-vaccines-all-or-some-employees-n1275808 (accessed July 20, 2022).

Montgomery, D. (2021). How to Sell the Coronavirus Vaccines to a Divided, Uneasy America. The Washington Post Magazine. Available online at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/magazine/2021/04/26/coronavirus-vaccines-ad-council/ (accessed July 20, 2022).

Perloff, R. M. (1989). Ego-involvement and the third person effect of televised news coverage. Commun. Res. 16, 236–262. doi: 10.1177/009365089016002004

Perloff, R. M. (2015). A three-decade retrospective on the hostile media effect. Mass Commun. Soc. 18, 701–729. doi: 10.1080/15205436.2015.1051234

Prochazka, F., Weber, P., and Schweiger, W. (2018). Effects of civility and reasoning in user comments on perceived journalistic quality. J. Stud. 19,62–78. doi: 10.1080/1461670X.2016.1161497

Rouner, D., Slater, M. D., and Buddenbaum, J. M. (1999). How perceptions of news bias in news sources relate to beliefs about media bias. Newspaper Res. J. 20, 41–51. doi: 10.1177/073953299902000204

Ruane, K. A. (2011). Fairness Doctrine: History and Constitutional Issues. Congress Research Service. Available online at: https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/R40009.pdf (accessed July 20, 2022).

Shearer, E. (2021). More Than Eight-in-Ten Americans Get News from Digital Devices. Pew Research Center. Available online at: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/01/12/more-than-eight-in-ten-americans-get-news-from-digital-devices/ (accessed July 20, 2022).

Terrell, K. (2021). These Companies are Paying Employees to Get Vaccinated. AARP. Available online at: https://www.aarp.org/work/working-at-50-plus/info-2021/companies-paying-employees-covid-vaccine.html (accessed July 20, 2022).

Tsfati, Y. (2007). Hostile media perceptions, presumed media influence, and minority alienation: the case of Arabs in Israel. J. Commun. 57, 632–671. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2007.00361.x

Tunney, C., Thorson, E., and Chen, W. (2021). Following and avoiding fear-inducing news topics: fear intensity, perceived news topic importance, self-efficacy, and news overload. J. Stud. 22, 614–632. doi: 10.1080/1461670X.2021.1890636

Vallone, R. P., Ross, L., and Lepper, M. R. (1985). The hostile media phenomenon: biased perception and perceptions of media bias in coverage of the Beirut massacre. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 49, 577–585. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.49.3.577

Voakes, P. S. (1997). Public perceptions of journalists' ethical motivations. J. Mass Commun. Quart. 74, 23–38. doi: 10.1177/107769909707400103

Wagner, C. M., and Boczkowski, P. J. (2019). The reception of fake news: the interpretations and practices that shape the consumption of perceived misinformation. Digital J. 7, 870–875. doi: 10.1080/21670811.2019.1653208

Weber, P., Prochazka, F., and Schweiger, W. (2019). Why user comments affect the perceived quality of journalistic content: the role of judgment processes. J. Media Psychol. 31, 24–34. doi: 10.1027/1864-1105/a000217

White, M. A. (2017). Ethical Journalism: Back in the News. UNESCO. Available online at: https://en.unesco.org/courier/july-september-2017/ethical-journalism-back-news (accessed July 20, 2022).

Keywords: hostile media bias, Facebook, news, comments, perception, COVID-19

Citation: Gearhart S, Coman IA, Moe A and Brammer SE (2023) Public thoughts on incentivizing COVID-19 vaccine uptake in the United States: testing hostile media bias with user-generated comments. Front. Sociol. 8:1041454. doi: 10.3389/fsoc.2023.1041454

Received: 10 September 2022; Accepted: 20 July 2023;

Published: 31 October 2023.

Edited by:

Pradeep Nair, Central University of Himachal Pradesh, IndiaReviewed by:

Ivo Furman, Istanbul Bilgi University, TürkiyeIuliana Raluca Gheorghe, Carol Davila University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Romania

Michele Marzulli, Ca' Foscari University of Venice, Italy

Copyright © 2023 Gearhart, Coman, Moe and Brammer. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sherice Gearhart, c2hlcmljZS5nZWFyaGFydEB0dHUuZWR1

Sherice Gearhart

Sherice Gearhart Ioana A. Coman

Ioana A. Coman Alexander Moe

Alexander Moe Sydney E. Brammer

Sydney E. Brammer