- Department of Geography and the Environment, California State University, Fullerton, CA, United States

Southern California has witnessed a burgeoning Indian immigrant population in recent decades. And among the cultural features that most distinguishes Indians is their cuisine. Their use of herbs and spices in food and medicine, in particular, is tightly bound to language, religion, gender, and overall cultural identity. Identifying how Indian immigrants' culinary choices adapt to southern California's varied and often fast-food based gastronomy, particularly impacts on the inter-generational transmission of traditional culinary knowledge, is important in terms of understanding the role of cultural retention and assimilation, as well as culturally-defined notions of food in physical and psychological well-being. We explored these questions by means of interviews with 31 Indian immigrant women in southern California. Participants were selected by means of snowball sampling. Our working hypothesis was that problems with sourcing and cultural assimilation pressures would have eroded the use of traditional herbs and spices. A total of 66 herbs and spices (and associated seasonings) were reported. Of these, the highest frequency of use was recorded for turmeric (100% of respondents) followed by cilantro, cinnamon, clove, cumin, curry leaves, and ginger (all 97%). The highest Species Medicinal Use Values were recorded, in descending order, for turmeric, ginger, fenugreek seeds, clove, cinnamon, curry leaves, and Tulsi. Contrary to expectations, there was no significant association between years resident in the United States and decreasing use of herbs and spices. Indeed, in some cases the confluence of northern and southern Indian immigrant women with a new identity simply as “Indian” resulted in an increase in the knowledge and use of herbs and spices. Spices are nearly all locally sourced, and where specific herbs are not readily accessible, they are cultivated in homegardens or brought directly from India. Many Indian immigrants are relatively prosperous and able to travel frequently to and from India, thus maintaining close cultural ties with their homeland. Indian immigrant women are fully aware of the health benefits associated with the use of traditional herbs and spices, and all participants reported that Indian food is a healthier choice than American cuisine. Knowledge is passed via vertical transmission, primarily through mothers and grandmothers to daughters. Overall, there is little concern among female Indian immigrants to southern California that knowledge and use of their traditional herbs and spices are in a state of decline.

Introduction

The sumptuous flavors, aromas, and colors derived from spices and herbs represent pivotal elements in the march of world history and the development of regional identities. For ancient peoples, spices truly were “fantasy substances” (Morton, 2000). The Chinese were importing various spices from Southeast Asia well before the Common Era, and vast quantities of spices flowed into ancient Egypt and later the Roman Empire from India and unknown points of the mysterious east (Warmington, 1928, p. 182; Dalby, 2000). Throughout the Middle Ages, exotic and astronomically expensive spices represented items of conspicuous consumption for Europeans of wealth and position. To serve highly spiced foods to guests was considered the highest form of snobbery (Freedman, 2008; Voeks, 2018, p. 120). And of course, the European Age of Discovery was fueled by dreams of discovering sea routes to eastern spice lands (Parry, 1955). It is not an overstatement to say that Columbus, de Gama, and Magellan, the three standard-bearers of the Age of Discovery, “were spice seekers before they became Discoverers” (Turner, 2004, p. 36).

But spices were not just pricey organoleptic enhancers. Various lines of evidence suggest that herbs and spices were in the past important elements in neutralizing harmful bacteria in tropical cuisines (Sherman and Billing, 1999). And they have long been perceived to possess miraculous medicinal virtues. The medicinal value of spices has deep historical roots in South Asia, and much of this was transferred to European medical practices by Arab pharmacologists (Gupta, 2012). In ancient Rome, black pepper from India's Malabar Coast was often referred to as “the Indian remedy,” especially for treating malaria (Warmington, 1928, p. 182). In Medieval Europe, spices were similarly revered for their medicinal attributes, particularly in their ability to harmonize the bodily humors (Freedman, 2008). During the fourteenth century, incense pouches containing pepper, ginger, cinnamon, cloves, turmeric, and other exotic plant products, were used to prevent “bad air,” which Europeans of that era regarded as a cause of the plague (Kuk, 2014). Strongly aromatic herbs have long been associated with rituals by the principal monotheistic religions, principally for purification, good luck, protection from disease and evil eye, and associations with witches and other demons (Dafni et al., 2020). Even today, many spices and herbs serve the dual function of livening up meals and treating medical maladies.

Spices and herbs also serve as cultural markers for the diverse ethnic peoples of the world. Just as foods and dining patterns serve as powerful symbols of cultural identity (Narayan, 1995; Flitsch, 2011), so to do the symphonies of scents, colors, and flavors of local herbs and spices serve to identify to which group individuals belong, and to which ones they do not (Etkin, 2009, p. 66). Some nationalities have become associated with a single spice or herb, such as paprika for Hungarians and peri-peri for Mozambicans. Other peoples are rather evenly identified with two or more spices and herbs, such as ginger and garlic for Koreans, shiso and sansho pepper for Japanese, and ginger and turmeric for Moroccans. Some groups are situated in the culture hearth of globally significant spices or herbs, such as chilis, vanilla, and Mexican oregano from Mexico, whereas others enjoy native spices that have remained largely endemic, such as wattle seed, lemon myrtle, and mountain pepper from Australia.

Among all the nationalities of the world, perhaps none is as readily identifiable as herb and spice lovers as Indians. Indeed, India's ancient Malabar Coast, today's Kerala, is often referred to as “the land of spices.” The use of herbs and spices is an integral component in the preparation of nearly every Indian dish, and it is not unusual to include 20 or more herbs and spices in a single recipe. The items used most commonly in India are black pepper, chili, mustard seed, cumin, turmeric, fenugreek seed, ginger, coriander, asafetida, and curry leaves, as well as spice mixtures that incorporate cloves, cardamom, and cinnamon (Srinivasan, 2010, pp. 66–67). In addition to the intoxicating mix of colors, flavors, and aromas, the presence of herbs and spices in Indian cuisine is keenly understood by Indians to also provide medicinal benefits. Whereas for some contemporary food cultures the concept of food as medicine is relatively novel, for the Indian community it is a long-standing tradition (Kessler et al., 2013; Chandra, 2016). Because the use of these spices and herbs is deeply lodged in India's various medical beliefs and practices, the retention and inter-generational transference of these culinary traditions among the Indian diaspora is culturally reinforced with religious reverence and belief. For Hindu culture, food is “the fundamental link between men and gods” (Appadurai, 1981, p. 496).

We are living in the age of human migration. There are at present an estimated 272 million international migrants, or some 3.5% of the total global population. Among the myriad sources of immigrants, India continues to have the largest number of migrants (17.5 million) living abroad (United Nations, 2020, p. 19). And whereas immigrants to the United States (US) arrive from varied socio-economic backgrounds, from refugees and low-skilled urban workers to highly skilled professionals and entrepreneurs (Zhou et al., 2008; Zong and Batalova, 2017), most of the Indian immigrants that arrive in the US are skilled laborers, filling the need in the labor market primarily in the fields of engineering and medicine (Rumbaut, 2008; Zong and Batalova, 2017). According to the U.S. Census Bureau, in 2017 a total of 712,532 people in California reported as Asian Indian, representing a growth of over 16% in just 2 years.

This article documents the culinary and medicinal uses of spices and herbs among Indian women residing in southern California. Immigration is underpinned by various cultural assimilating forces, among these being changes in foods and cuisines. Given these influences as well as the sharp distinction between the knowledge and use of spices and herbs between Indian and Anglo-American cuisine, our working hypothesis was that there would be an overall reduction in the usage of traditional herbs and spices over time among Indian women immigrants to southern California, and that this reduction would be most evident in those who had resided in the US longer (see Benson and Helzer, 2017). Based on research concerning the importance of language as an indicator of a strong and confident cultural identity, we further hypothesized that participants who were more likely to speak English as their dominant language instead of the traditional Indian language with which they were raised were more likely to accept change in their food habits as well, assimilating to a more American or western cuisine (Wallendorf and Reilly, 1983; Montanari, 2006; Rumbaut, 2008; Kang, 2013; Parasecoli, 2014). Finally, we hypothesized that although there would be differences between the types of meals, as well as spices and herbs used to prepare them, based on the North Indian and South Indian cultural identification, the connections and sharing of knowledge that exists within the Indian immigrant community in southern California would blur these distinctions over time.

Materials and Methods

Thirty-one Indian female immigrant research participants were selected through the snowball sampling method in Los Angeles and Orange counties during a 5-month period in 2017. The women were all over the age of 18, of Indian descent, and living in southern California. We focused our interviews on Indian women because they are primarily in charge of domestic responsibilities, including food preparation (Appadurai, 1981), even after migration to the North America (Ray, 2004 p. 115; Acharya and Acharya, 2008; Vallianatos and Raine, 2008). Data were obtained by means of personal interviews and a questionnaire with respondents, both of which were approved by the California State University, Fullerton Institutional Review Board. Participants were asked for permission to use the results of their interview through oral consent preceding the personal interview process, and to audio record their interview. At the end of each interview, respondents relayed contact information about other potential participants in the project. The majority of participants were parents of children who were born in the US. Most of their children were under the age of 18; however, some participants had adult children who had children or families of their own.

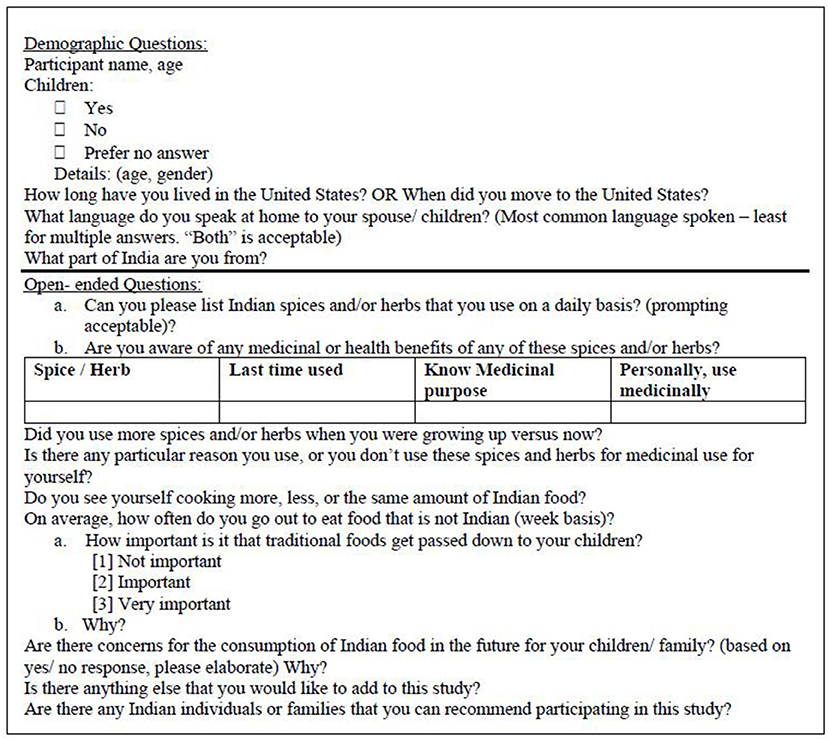

The questionnaire consisted of demographic and socio-cultural questions, as well as freelisting of herb and spice usage. We inquired about cultivation of traditional herbs at home, as well as about usage and perceived knowledge of the medicinal qualities of herbs and spices (Figure 1). Species Use Value for medicine was calculated with reference to Hoffman and Gallaher (2007). Quantitative data were assessed by means of linear regressions and Student's t-tests. A few questions were considered but eventually omitted before the final version. The question of religious lifestyle of the participants upon immigration to the US was considered for the purpose of measuring cultural identity. The ability to comfortably practice the religion of an immigrant's homeland plays a significant role in cultural identity, and Indian medicinal and health beliefs are often rooted in religious beliefs. However, the sensitive nature of a person's religious beliefs raised some ethical concerns, and we therefore omitted reference to religious beliefs, using instead language use as a reasonable proxy of cultural identity and assimilation.

Results

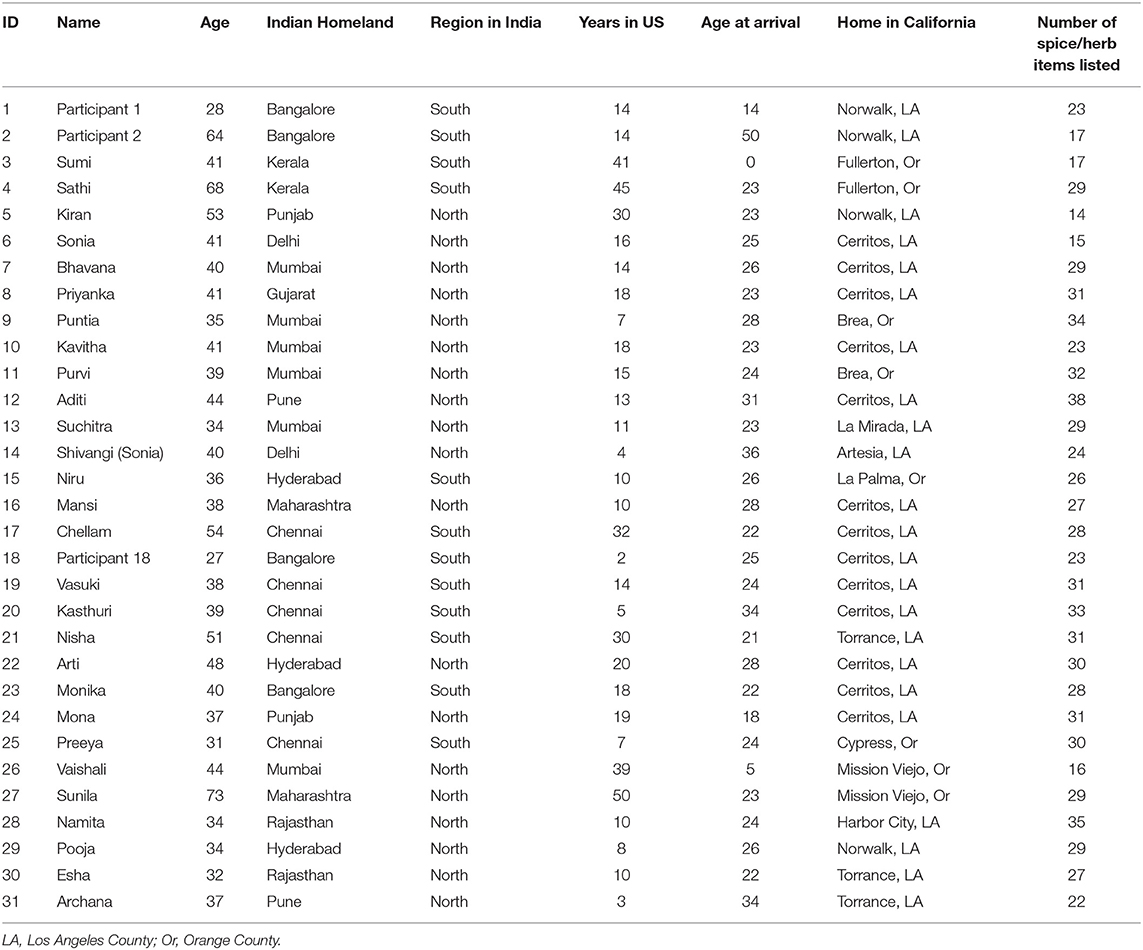

The socio-cultural results and the total number of spices and herbs recorded by the respondents are listed in Table 1. First names of participants who chose to reveal their names are included. Many of the study participants lived in relatively close proximity to one another in southern California, but they originated from various regions of India (Figure 2). Although India is home to many different languages, clothing styles, and cuisines that often vary on a state-by-state basis, a clear north-south distinction exists; most Indians identify as being either North Indian or South Indian. The majority of participants in the study (19) hale from North India, whereas fewer came from South India (12).

Table 1. Participant socio-cultural information, including name, age, original homeland, North or South India origin, years living in the US, age at arrival in US, city and county in US, and total number of herbs/spices listed.

The number of years female participants had lived in the US varied from 3 to 50 years. Using number of years living in the US as a proxy for likely degree of cultural assimilation, our first hypothesis, that usage of traditional herbs and spices would decline over time, was not supported by the data. There was no significant linear association (y = 28.791-0.1125x, p > 0.05) between number of years living in the US and the total number of herbs and spices used by respondents in cooking. Women who had lived in the US for several decades were just as likely to use the same number or even more herbs and spices than women who had recently arrived. Sunila, for example, had resided in southern California for fifty years and was able to list 29 herbs and spices that she used on a frequent basis. Archana, on the other hand, who had been in the US for just 3 years, listed only 22 herbs and spices that she regularly used. Overall, number of years of exposure to American culture and cuisine seems not to be leading to an evident erosion of knowledge and use of herbs and spices among Indian immigrants.

Moreover, in response to the question of whether they were using more, less, or the same herbs and spices after arriving in the US, 35% indicated that they were using more, and 39% said about the same. Only 13% of respondents thought that they were using less traditional herbs and spices.

Regarding language continuity, 19 of 31(61%) participants spoke primarily English or a mixture of English and an Indian language at home, whereas 12 of 31 (39%) spoke primarily an Indian language. Indian languages spoken at home included: Dogri (3%), Gujarati (13%), Hindi (16%), Kannada (3%), Kutchi (6%), Malayalam (3%), Marathi (23%), Marwari (3%), Punjabi (10%), Saurashtra (3%), Tamil (19%), and Telugu (6%). Percentages exceed 100% because several participants spoke more than one Indian language at home. The mean number of herb and spice items used by those who spoke either English or English and an Indian language was 26.7; the mean number for those who spoke primarily an Indian language was nearly identical at 26.9. These means were not significantly different (t = −0.0786, p > 0.05).

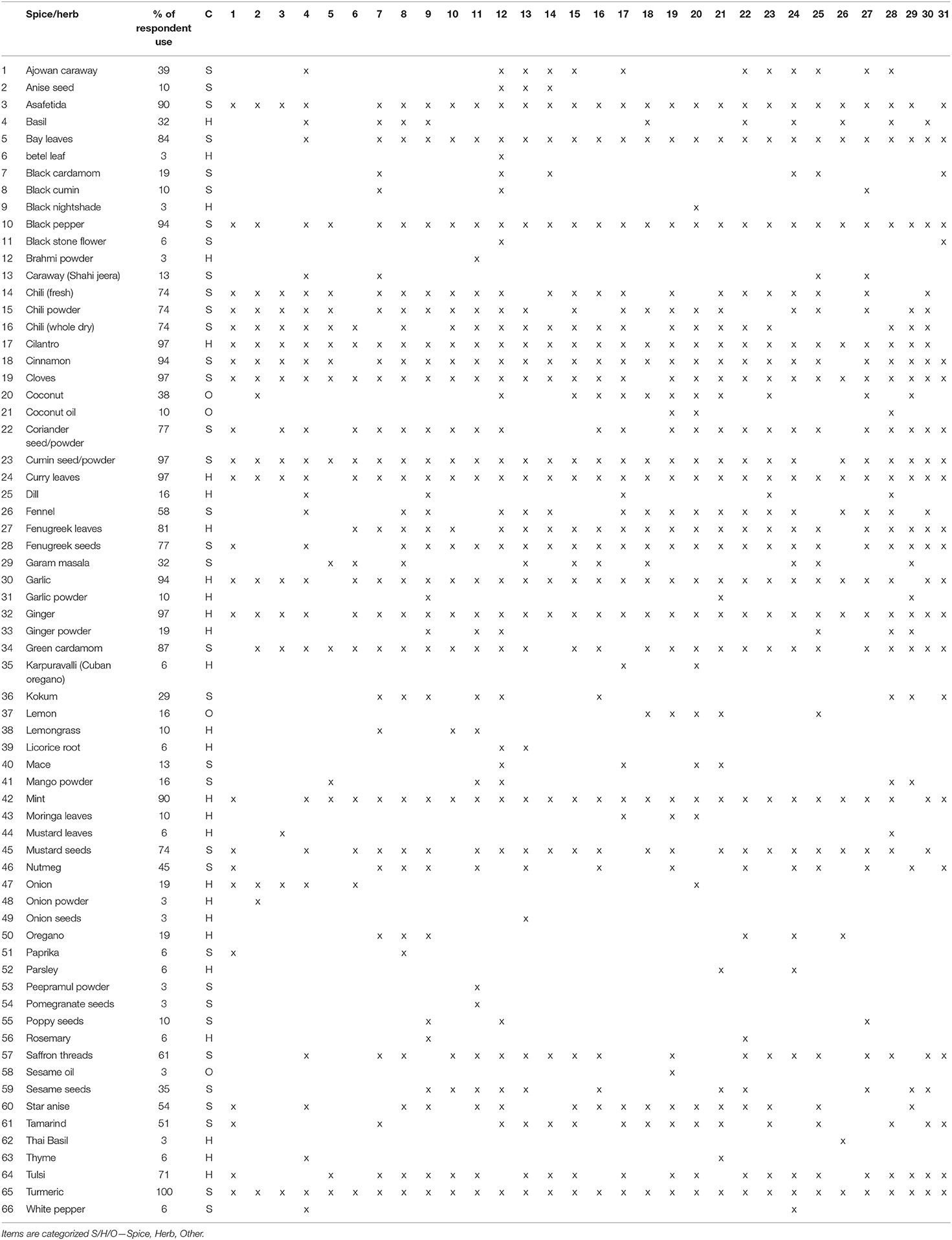

Respondents originally listed 78 unique culinary items. Of these, 12 did not constitute proper herbs or spices, but rather seasonings or condiments, such as black salt, ghee, honey, ready-made masalas, and yogurt, and these were culled from the data. The only exceptions were coconut oil, coconut meat, lemon, and sesame oil, all of which are used in cooking as if they were herbs and spices, and all of which are perceived to have medicinal properties. The final list includes 66 items-−35 spices, 27 herbs, and 4 “others” (Table 2). Species usage per culinary item varied from 100% of respondents to a single respondent. The most commonly used item was turmeric, which was used by 100% of respondents, followed by cilantro, cloves, cumin seed, curry leaves, and ginger, which were used by 30 of 31 respondents. All of these species are native to the Old World, and all have been important elements in Indian cuisine since ancient times.

The 31 participants listed between 14 and 35 herbs and spices, with a mean of 26.8. In terms of regional provenance, participants from North India averaged 27.1 herbs and spices, whereas those from South India averaged 26.3. There was no significant difference in herb and spice usage between North and South India respondents (t = 0.334, p > 0.05).

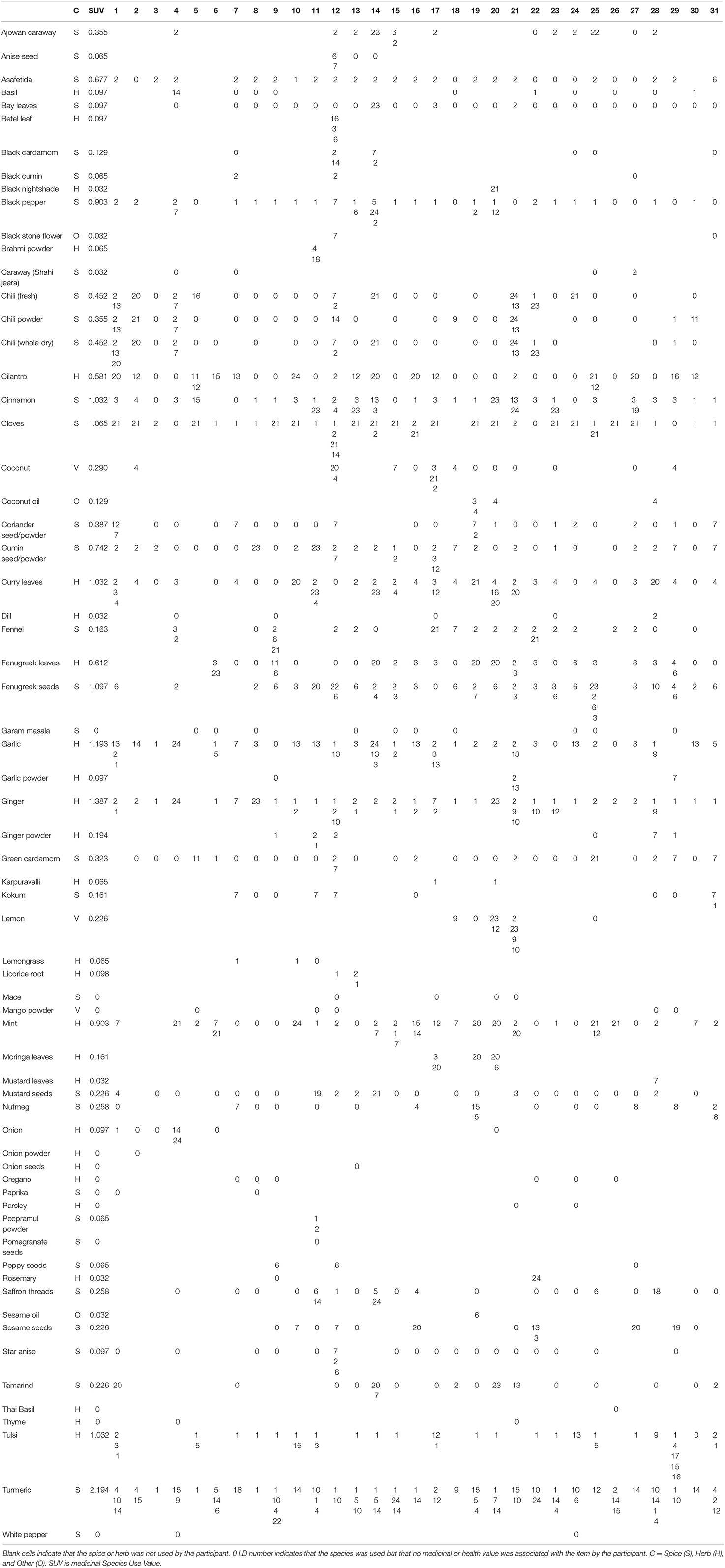

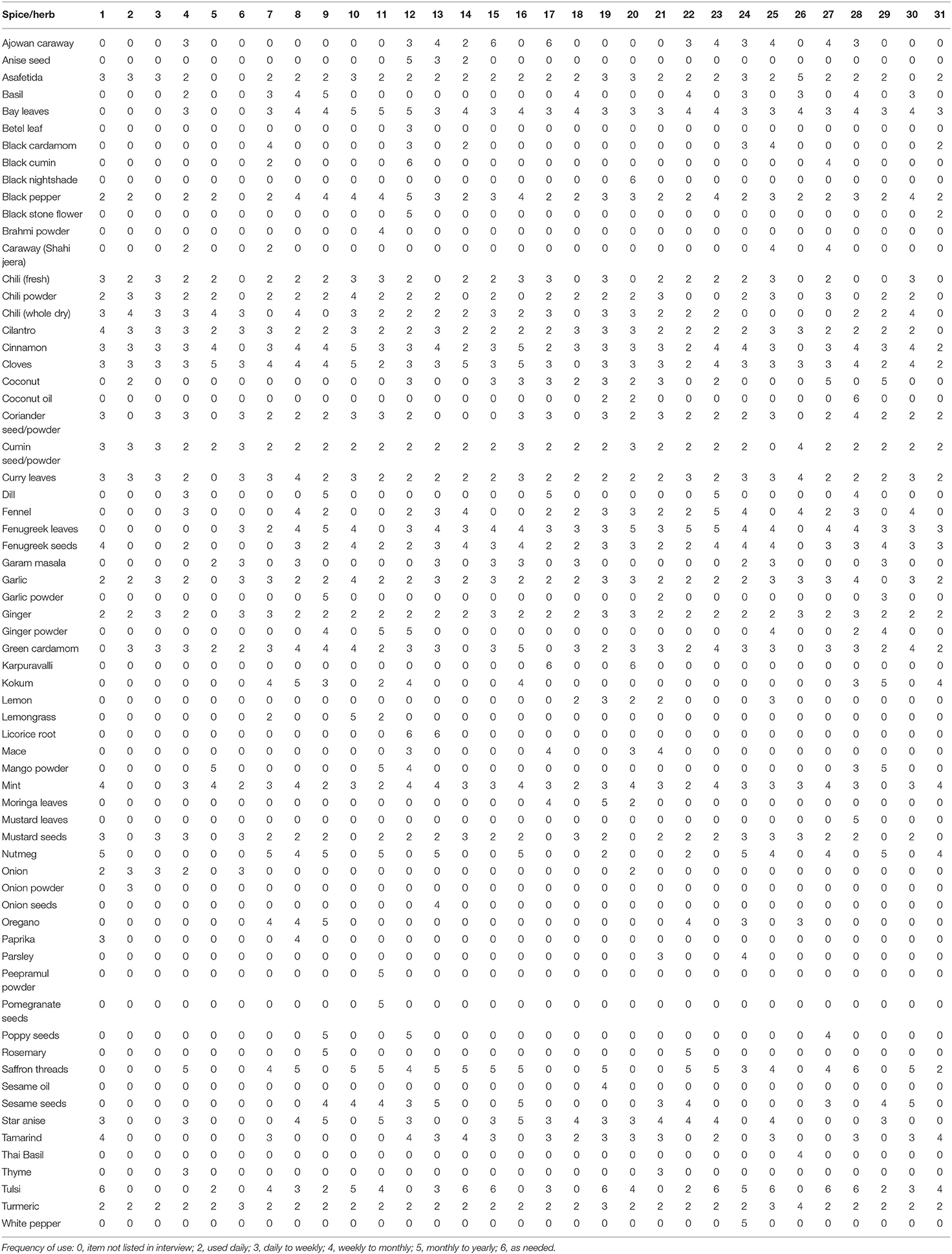

The frequency with which herbs and spices are used by individual respondents is also an indicator of the item's importance to the individual and the greater community. Frequency of use was calculated into five categories. A numeric value between two and six was attached to each of the categories to classify the data. The frequency of use for each participant for the items listed in their corresponding interviews are listed in Table 3. Many of these items were used daily or weekly; however, there were a few items on the list, such as Tulsi and saffron threads, that were primarily listed as “used as needed” indicating that their purpose in Indian households is not specifically related to food. The frequency of use of each of the items is an important dimension of overall importance. Items that are used daily are usually considered more important than items that are used seldom or rarely. Items that are “used as needed” are also important, however, because they are used either specifically for their medicinal properties when the occasion arises, or they are used on special occasions. Items that are rarely used, noted as a numeric value of four or five, are overall less important than items that are rated two, three, or six.

Table 3. Frequency of Use for Items listed during participant interviews (0 indicates that participants did not list the item during the interview process).

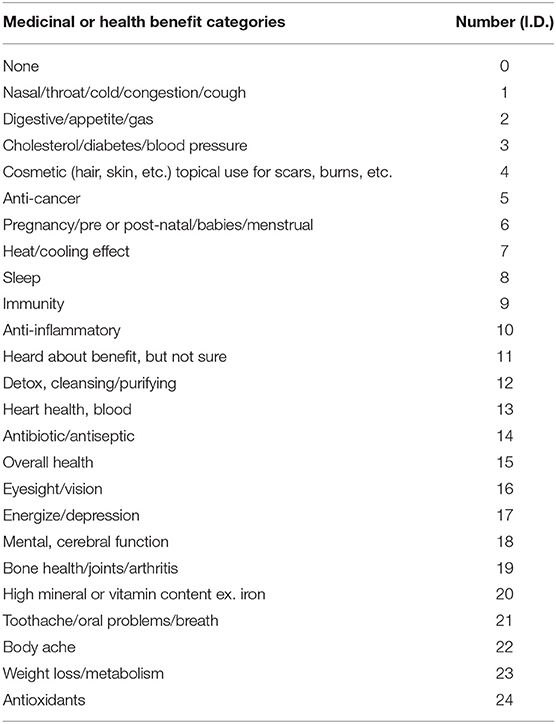

Participants revealed various medicinal and health benefits associated with the spices and herbs they used in cooking. These are organized into 24 categories in Table 4. Categories range from preventative measures, to treatments for minor ailments such as coughs and digestion, to claims of preventing or treating more serious health issues such as cancer, diabetes, high blood pressure, and cholesterol. Other uses were oriented to overall well-being, such as cosmetic, weight loss, detoxing, and heating/cooling down the system. Remedies were used for personal and family care, especially in treating influenza, colds, and coughs in children. Medicinal and health benefits for each herb and spice item are listed in Table 5.

Table 4. Medicinal and/or health benefit categories and identification (I.D.) number (corresponding with Table 5).

The Species Use Values (SUV) for medicinal applications and health benefits were calculated using Hoffman and Gallaher (2007, p. 209): UVis = (∑UVis)/(ni), where Uis is the total number of uses mentioned for item s, ni is the number of respondents (Table 5). The highest medicinal SUV was for turmeric (2.109), meaning that on average the 31 respondents perceived turmeric to have over two medicinal properties. Six other herbs and spices contained on average more than one medicinal use per respondent, including cinnamon (1.032), clove (1.065), curry leaves (1.032), fenugreek seeds (1.097), ginger (1.387), and Tulsi (1.032). Although a wide range of perceived medicinal properties were listed, several species retained relatively consistent values.

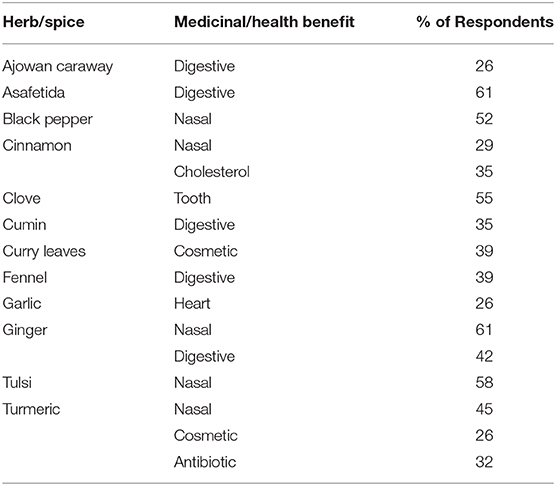

Although many of the medicinal benefits were idiosyncratic among the respondents, that is, often only one or a very few respondents associated a particular herb or spice with a particular medicinal or health benefit, some perceived benefits were fairly consistent among respondents. In Table 6, 12 herb and spice items with > 25% consistency among respondents are listed. These include three that were perceived useful for more than one purpose, including cinnamon, which was useful for nasal problems, colds and cough, and cholesterol, ginger, which was useful for nasal (and associated issues) and digestive issues, and turmeric, which was considered useful for nasal problems, cosmetic uses, and as an antibiotic.

Table 6. Herbs and spices with >25% consistency of medicinal/health benefits among southern California Indian immigrant women.

Discussion

Traditional Herbs and Spices

The relationship between food and people is a complex connection involving both tangible and intangible elements. It is influenced by the availability of ingredients, as well as through the cultural environment into which intangible factors, such as ideas, perceptions, and belonging, play key roles influencing the people-food nexus. From a cultural perspective, food and cuisine are fundamental means through which cultural identity can be expressed and shared. They are central components to the sense of collective belonging (Narayan, 1995), and they are highly visible and olfactory means through which people separate themselves from others (Narayan, 1995; Fischler, 2011; Flitsch, 2011; Bailey, 2017). Thus, “Man [and woman] eats, so to speak, within a culture, and this culture orders the world in a way specific to itself” (Fischler, 2011, p. 281). Food not only creates a sense of oneness within a community or cultural group, but it also creates a sense of otherness, wherein people identify themselves as different from others based on food and cuisine choices. A person's culture is the foundation upon which their food and their culinary choices are determined, and each possess cuisines or dishes that are considered traditional and therefore fundamental to a person's sense of identity.

In the case of international immigrants, there are many obstacles-socio-cultural, economic, and material-that can hinder and otherwise suppress the preparation or consumption of their traditional foods, or that can facilitate it (Vallianatos and Raine, 2008). At a basic level, they have two options—follow traditional assimilation models and conform to mainstream cultural norms of their adopted home, or create a new cultural niche where they can continue and perpetuate the culture and identity of their homelands. The former is historically the rule rather than the exception among most immigrant groups to the US. According to Gabaccia (2009, p. 225), in spite of the various motivations for preserving traditional ethnic food customs, American immigrants “play with our food” far more often than we preserve the culinary traditions of our ancestors. Many second-generation Sikh immigrants in California's Central Valley, for example, report a total transition to American fast food and snacks (Benson and Helzer, 2017). Drivers of culinary preservation or re-creation, on the other hand, include the profound culture-bound role of food in Indian culture, as well as the complex gendered role of women in the kitchen (Appadurai, 1981). It is also driven by nostalgia that is “predetermined, indeed overdetermined, in scripting immigrant attachment to the past” (Mannur, 2009, p. 28). Food-based nostalgia can be as much for a cuisine that is unknown and untasted, and for a homeland to which one never wishes to return (Roy, 2002). In the case of Indian immigrants to southern California, gastronomic preservation rather than assimilation has predominated, with notable exceptions. Many have the financial resources and security to live differently than unskilled immigrant laborers and refugees, and these conditions allow Indian immigrants to live within their personal cultural comforts without much opposition or motivation to assimilate. This includes the option of continuing culinary traditions. Many Southern California Indians travel on an annual basis to their homeland, or even more frequently, where their traditional culinary practices are reinforced and, perhaps, new ones introduced.

Availability, access to, and affordability of culinary resources is another factor that either facilitates or hinders the transfer of food and cuisine traditions. Arab immigrants to Canada, for instance, were unable to source fresh parsley, a key ingredient in Arab cuisine. And Indian immigrants were limited by the high cost of imported foods and spices (Vallianatos and Raine, 2008). In most cases, however, this has not posed a challenge for Indian women immigrants to southern California. Indian shops have become a ubiquitous feature of southern California's urban landscapes. And if an important culinary item is not found in one or another local shop, they have the option of making a short trip to “Little India” in the city of Artesia, where more than 100 shops cater to the needs of the Indian community. As for the rare or specialty items that are not available, these can be purchased in bulk during visits to India.

The participants in this study were eager to share their knowledge about Indian cuisine and the medicinal and health benefits of spices and herbs that are used frequently in Indian cooking. While some were more knowledgeable than others, all employed a wide array of herbs and spices in their cooking, and all were familiar with some of their medicinal and/or health benefits. Participants ranged from 2 to 50 years of residence in southern California. They listed an average of roughly 27 herb and spice items, with no significant difference between North and South Indian women, and they averaged 10 items used daily among all participants. Because it is not possible to know how many spices were being used in their cooking prior to immigration, there is no way to quantitatively determine whether there has been continuity of herb and spice usage. However, there was no evidence, either in terms of years living in the US and herb/spice usage, or in terms to respondent's perception, that traditionally used herbs and spices were declining in usage. Indeed, nearly 40% of respondents reported increased knowledge and usage of both. The most commonly known and used herbs and spices used in cooking by Southern California Indian women—asafetida, black pepper, chili, cilantro, cilantro, cloves, coriander, cumin seed, curry leaves, fenugreek, garlic, ginger, mustard seeds, and turmeric—are identical to the most commonly used herbs and spices in India (Srinivasan, 2010). At least in terms of usage of core herbs and spices, migration to southern California appears not to have led to significant culinary abandonment.

Regarding the perceived medicinal and health value of culinary items, the usage frequency list was nearly the same, with the exception of cinnamon and Tulsi. Neither are used in cooking on a daily basis by many of our respondents, but both are known and used when needed for their medicinal qualities. Although respondents cited a wide range of medicinal benefits from their culinary herbs and spices, from antibacterial to cancer to weight loss, the most common gastronomic treatments were for respiratory ailments (cough, colds, sore throats) and digestive complaints (stomachache, gas).

The source of the participant's knowledge was an important component of our findings. Indian immigrant women's herb and spice knowledge was derived from various of sources, but primarily from their mothers, or mothers-in-law, that is, via vertical or horizontal matrilineal transmission, well as through female friends. There was also a strong sense of pride in their medicinal knowledge of spices and herbs, as women who knew more about Indian medicine and the medicinal use of spices and herbs were considered particularly valuable members of the Indian immigrant community.

In terms of perceived health benefits, all 31 participants reported that Indian food was much healthier than alternative local food options, especially for those who followed a vegetarian diet. Vegetarian participants often reported that by preparing Indian food, they not only had more culinary options, but also had the opportunity to eat food that they considered palatable. For example, one participant (Arti) noted “For us it [Indian food] is better because how often can we eat out? If we get fast food, we are limited to cheese quesadillas at Del Taco, and even then, we don't know how they are prepared—if they actually are vegetarian.” This perspective was true for a large number of the participants, as many followed a strict vegetarian lifestyle. Their vegetarian dietary restrictions enabled them to continue to prepare Indian recipes, perpetuating the use of Indian spices and herbs as part of a daily routine. Thus, as similarly reported for Indian immigrants in the Netherlands (Bailey, 2017), cultural identity is maintained not only with food choices, but also through following dietary restrictions as part of religious beliefs.

Language is also a fundamental factor in cultural identity (Wallendorf and Reilly, 1983; Montanari, 2006; Kang, 2013; Parasecoli, 2014), especially as it relates to communication and understanding, but also as it relates to food and spiritual practices. In India, each region is characterized by a separate language, and it is common to know, speak, and/or understand more than one Indian language. The national language in India is Hindi, which is taught is most schools. The majority of the participants in this study referred to the Indian spices and herbs they used on a regular basis in their language of origin, for example “jeera” for cumin seeds, “elaichi” for green cardamom, or “dhaniya” for coriander seeds or powder. There were instances in which the participants did not know the English name for certain spices and herbs, instead referring to them in Hindi, Tamil, or Kannada. Some of these items were purely medicinal in nature, such as “karpuravalli,” commonly known as Cuban oregano, Mexican mint, Indian borage, or Caribbean oregano; and “meeta laghdi” (literally translates to “sweet stick”) for licorice root. Both these items are used to prepare medicinal concoctions to help fight minor ailments such as coughs, colds, and digestion problems, especially with infants and small children. Some participants referred to spices and herbs in their Indian name and followed with the English equivalent, such as “jeera” followed by “cumin seed.” This indicated that they knew the English name for some of the items listed, but preferred to call the items in their language of origin. The knowledge of spices and herbs is thus closely linked to the Indian language of their homeland.

Language is a significant dimension of cultural assimilation. In this sample, a majority of participants spoke either English or a mix of English and an Indian language (or more than one), whereas a minority spoke primarily an Indian language at home. Although we hypothesized that traditional herb and spice usage would decline among English speakers, this was not the case. Both groups used nearly identical numbers of herbs and spices in their cooking.

Passing the Torch

Identifying the factors that are involved in the intergenerational passage of knowledge pertaining to Indian cuisine improves our understanding of cultural traditions, cultural erosion, and cultural identity. But the transfer of the culinary torch from one generation to the next means much more than the passing of culture and cultural identity, especially because of the abundant medicinal health benefits of a majority of the spices and herbs used in Indian cooking (Dhandapani et al., 2002; Hemphill and Cobiac, 2006; Muthu et al., 2006; Srinivasan, 2010; Srivastava and Vankar, 2012; Kessler et al., 2013; Murugan et al., 2013; Malav et al., 2015; Siruguri and Bhat, 2015), as well as the linguistic connection created through the transfer of traditional food knowledge and practice. For many of the women in this study, intergenerational cuisine continuity ensured the health of generations to come. And all participants indicated that passing down the knowledge and use of Indian spices and herbs to future generations was of paramount importance.

Participants strongly supported the idea that Indian food was synonymous with a healthy lifestyle. And surprisingly, none were concerned that their children would have difficulty continuing to prepare and consume traditional food. All had confidence that their children would continue to cook and prepare Indian food, and would continue to use Indian spices and herbs on a regular basis, especially their female children. The reasons listed were both related to access and acceptance of Indian food in the region. The diversity of southern California's cultures fosters an environment in which cultural identities can be easily and confidently expressed through the use of traditional language, clothing, religion, and food. Bhavana, for example, when asked to elaborate her highest rating on the level of importance of passing down Indian culinary traditions from one generation to the next, stated “I really feel we are passing down culture because I am the only person who will pass it down to my daughter and son, more my daughter I feel. I think it is very important that they know what language we speak, which region we came from, what our origins are, and what food we eat.” In addition to passing down language and regional origins, Bhavana's statement also underscores the fact that traditional gender roles are still an important consideration, even after immigration to the US. Although she was eager to share her knowledge of the use of Indian spices and herbs with both her son and daughter, Bhavana clearly felt it was her duty as a woman to pass it down to her daughter, more so than to her son. This identifies the gendered roles that are prevalent in Indian culture, with the woman's responsibility to maintain and pass on Indian culture, as Acharya and Acharya (2008) identify with the term “bharatiyanari” which encompasses many gendered ideals, including the transfer of culture.

These gender ideals have been much discussed elsewhere. Ray (2004) reported that many Bengali-American women, regardless of education, preferred to stay home to do housework and raise children. “One woman with a medical degree classified herself in the survey as a ‘housewife,’ while another was a physician's assistant; another woman with a Ph.D. stayed home” (Ray, 2004, pp. 115–116). Acharya and Acharya (2008, p. 39) state that Gujarati women are often expected to be “repositories and transmitters of culture.” They are also expected to handle duties that are labeled “Pativrata Dharma (the duty of the wife),” which include responsibilities such as cooking, housework, and childcare. Contrary to the fluid and changing gendered roles in the western world, traditional male and female roles are still very much alive in Indian households. According to the participants in this study, the duty of passing culinary knowledge to the next generation remains a primarily female responsibility.

In at least one case, recollection of superstitions and stories helped perpetuate the use of spices and herbs. Paraphrasing one of the statements made by Kasthuri during an interview, when asked about the health or medicinal benefits of black pepper, she stated “Even if you eat at the house of your enemy, if you put a lot of black pepper in your food, you will survive.” She explained that black pepper is medicinally valuable as a detox, removing toxins, heavy metals, and poisons from the body.

Regional Identity

Participants reported that a portion of their knowledge of the medicinal benefits of spices and herbs was made through friendships they made after arrival in southern California. Indian immigrants in southern California no longer distinguished themselves as being from a particular region in India, but rather identify as being “simply Indian.” This homogenization of cultures has resulted in a blending of regional cooking traditions and the transfer of culinary knowledge across boundaries that are no longer perceived to be relevant. Indian cuisine varies considerably from region to region, in particular, between foods and culinary items that are “North Indian” or “South Indian.” These dishes vary not only in the way they are prepared and taste, but also in the herbs and spices used. South Indian food is rarely prepared or consumed in North Indian households, and vice-versa (Narayan, 1995). Crossing the international boundaries from India to the US allowed participants to cross culinary boundaries that they probably never would have crossed if they still lived in India. Identifying as simply Indian, without regional distinctions, has allowed immigrants to identify as a unified group, separated from “the other” non-Indians (Flitsch, 2011).

An example can be seen by considering the participants' use of curry leaves. Whereas curry leaves are primarily seen in South Indian cuisine (Joseph and Peter, 1985; Hema et al., 2011; Singh et al., 2014), 96% (30 out of 31) of participants mentioned that they used curry leaves in their cooking. Sixty-one percent of these participants identify themselves as being from North India, where curry leaves are not traditionally used in meal preparation. Many of these participants mentioned that they had begun to use curry leaves after their migration to southern California and learning about the medicinal benefits that curry leaves are thought to contain. Most of their knowledge was derived from association with friends from South India, as well as research on social media and the internet.

Homegardens

Southern California's Mediterranean climate allows for near year-round cultivation of tropical and subtropical plants. Homegardens, where familiar fruits, vegetables, and herbs can be grown, as well as plants used for medicine and religious purposes, are exceptionally important for immigrant cultures (Helzer, 1994; Ban and Coomes, 2004; Vandebroek and Voeks, 2018). They represent personal space where useful plants that are not available in local markets may be grown, and they often represent botanical symbols of the process of cultural continuity. Many Indian spices and herbs have significance to Indian cultural history and cuisine beyond simple gastronomy. This is especially true of holy basil—Tulsi—whose significance in India extends beyond its use in the pantry and kitchen and into religious practices and symbolism. It is “the most sacred of all Hindu plants” (Simoons, 1998, p. 8), and this special standing is still prevalent within the Indian immigrant community in southern California. Participants indicated that Tulsi was a very important plant in their lives and for Indian culture in general. In India, it is tightly connected with the god Vishnu, and it is in its own right, considered a goddess. In terms of access, all 31 participants either personally cultivated or knew someone who cultivated Tulsi plants in their homegardens. At least one medicinal use for Tulsi was listed by 22 of the 31 female participants. Tulsi plants usually adorn front entranceways, pathways, or are potted in planters on apartment balconies and porches. The herb's vital spiritual role was elaborated by Kiran, who noted that she makes a religious food offering with Tulsi every day during her daily prayers. She declared that the goddess Tulsi would not “bhog” (Hindi word for consume or eat) the food offerings if she does not eat some Tulsi first. Every morning, both Kiran and the goddess consume Tulsi leaves before any other food. Another participant, Pooja, recalled that when she was considering removing one of the Tulsi plants that her mother had planted in the yard, her mother responded “If you cut this plant, you will cut my life.” When asked about the significance of Tulsi in her household, Preeya stated that “Tulsi is the mother of all herbs.” The front gateway of Arti, another participant, is adorned with a lush and bountiful Tulsi bush from which she picks off a few leaves and consumes them whenever she passes the plant (Figure 3A). She believes that it is good for her overall health. In addition to providing “good oxygen” (Preeya), a majority of respondents reported its use to treat coughs and colds. The presence of a Tulsi plant in a homegarden is a cultural marker that Indian people live in that home.

Figure 3. Home sources of selected herbs by southern California Indian immigrant women. (A) Tulsi in homegarden; (B) Karpuravalli in homegarden; (C) Curry leaf tree in homegarden; (D) Meeta lagdhi (licorice root) brought from India.

Other plants that are used in Indian cooking or for medicine and were difficult to source were also found in some of the homegardens. These included karpuravalli, a species of oregano used to treat coughs and colds (Figure 3B), as well as curry leaves, which as noted earlier, are a mainstay of South Indian cuisine that have been adopted by almost all North Indian women immigrants to southern California (Figure 3C). In addition to livening up their foods, curry leaves are employed to treat a wide array of illnesses. Finally, in those rare cases where a traditional herb or spice cannot be locally sourced, respondents noted that they are able to bring these in on their frequent trips to their homeland. This includes licorice root (meeta laghdi), which is used by a few participants as flavoring and medicine (Figure 3D). The inclusion of these plants into homegardens is important because, in addition to their utility for the family, they are shared among their community of Indian friends.

Traditions in Transition?

For female Indian immigrants living in southern California, association within the greater Indian community is pivotal to the presence and perseverance of culinary traditions. Community identity encourages cultural continuity. However, some culinary changes were reported. Although relatively minor, these changes were mostly focused on convenience and increasing the health value of the food consumed. For example, although Indian food is consumed daily, participants reported that they made compromises when it came to work and school, that is, in the public sphere (Vu and Voeks, 2012). This was not because of embarrassment, but rather because of convenience. Children carry peanut-butter and jelly sandwiches and Oreo cookies from home for lunch and snack time because there is not enough time to eat roti (Indian flat bread) and curry at school (see also Vallianatos and Raine, 2008). Parents carry salads to work because rice and curry is an inconvenient food to heat and consume in the office. The sheer complexity that embodies Indian cuisine makes it a difficult food, not only to prepare, but to transport to work or school. For these reasons, Indian food in many instances is substituted with another alternative that was easier to eat and consume in public places; they are Americans when eating out, and Indians when eating at home.

Another example can be seen with the substitution of ingredients. Most participants indicated that they had modified the ingredients in their cooking to include healthier options, while maintaining the integrity of traditional Indian dishes. For example, many said that they substituted quinoa for rice, and that they made chapatis and rotis healthier by substituting multi-grain flour for the traditional rice flour during preparation. It is unclear whether these substitutions would have occurred with the participants had they been living in India, especially with increased global connectivity and social media platforms such as Facebook and WhatsApp, which are widely used by the participants to communicate and discover new knowledge about Indian spices and herbs, Indian cooking, and their traditional medicinal use. However, living in southern California, these participants are exposed to a wide array of alternative ingredients making it easy to substitute traditional ingredients with healthier choices, creating a variation of Indian cuisine that converges ingredients in a best-of-both-worlds scenario.

The elaborate process to prepare ingredients that enter into cooking traditional Indian dishes serves as a challenge for busy participants. Therefore, it is often easier for them to use the ready-made masalas (spice blends), that can be purchased at any Indian store and are widely used in India as well. The most popular is garam masala that contains “five or more dried spices, commonly comprised of cardamom, cinnamon, and clove” (Srinivasan, 2010, p. 67), and is used in a variety of Indian recipes. Because these items are readily accessible in southern California, it adds an element of convenience to preparation allowing the participants to prepare traditional Indian meals.

Other changes were the result of personal choice and, in all likelihood, the influence southern California gastronomic culture. One participant, for example, was special in that although she was the most recent immigrant to the US, having emigrated from India only 2 years prior, she exhibited the most change in her consumption of Indian food. She had come to southern California to finish her education at a university and to procure a job. However, in her college experience, she had decided to adopt a vegan lifestyle, which is much different and significantly more “American” than an Indian culinary choice. Many Indians are vegetarian (estimated at about 20%, Natrajan and Jacob, 2018), but even among vegetarians there is considerable consumption of dairy and dairy-based products within Indian cuisine that does not fit into a vegan diet. She did, however, continue to prepare most of her food with Indian spices and herbs, albeit to a lesser extent than would be necessary in traditional Indian recipes. This was done not only to preserve flavors that were desirable or familiar but also because she was aware that Indian spices and herbs added medicinal elements to her vegan dishes. In this case, she had not moved away completely from the use of Indian spices and herbs in cooking, but rather had adopted what she considered to be a healthier alternative to fit her lifestyle needs.

Finally, although the knowledge of traditional spices and herbs is primarily rooted in knowledge that has been passed down from generation to generation, many of the women in this study owed part of their knowledge of their medicinal value to other less conventional sources. Several stated that some of their knowledge of the health dimension of Indian food expanded out of their own personal research using the internet, social media, and through informal conversations with friends within the Indian immigrant community.

There were acknowledged limitations to this study. First, the exclusion of men from the data set may well have led to omissions in understanding the herb and spice transference process and the nuances of gendered roles. In the Netherlands, for example, Indian immigrant men are often forced to learn to cook because they often emigrate alone (Bailey, 2017). Moreover, as noted by several Canadian Indian and Muslim women, men may not take an active role in cooking, but they often help much more in kitchen duties, thus modifying traditional gendered roles (Vallianatos and Raine, 2008). Second, there was an apparent bias toward Hindus in the sample. Although we did not ask participants about their religion, most self-reported being Hindus, with only two noting that they were Christians. A larger sample that included a greater cross section of underrepresented groups might have changed the results. Finally, the snowball sampling method led us to mostly middle and upper middle class Indian Americans. Although Indian immigrants to the US are more likely to be highly educated, occupy management or otherwise professional positions, and have lower poverty rates than other immigrant groups (Zong and Batalova, 2017), purposeful sampling among less prosperous Indians may have amplified the findings.

Conclusions

This research explored the importance of spices and herbs to Indian immigrant women in southern California. We investigated their role in traditional Indian cuisine, their medicinal and healing properties, and the intergenerational transfer of traditional knowledge. We found that the use of traditional Indian herbs and spices is thriving among California's Indian diaspora. The most important herbs and spices used in cooking are nearly identical to those used in their homeland. Indian cuisine among female immigrants to southern California is synonymous with functional food—food with perceived medicinal and health values. Many of the herbs and spices used by participants have been shown to possess therapeutic benefits, and all participants expressed their belief that Indian food was a healthier choice than American cuisine. There was no indication, either in terms of years living in the US or the use of English language in the home, that the usage of traditional herbs and spices is declining among Indian immigrants. Indeed, as North and South Indian immigrants self-identify as simply “Indian,” distinctive herbs and spices that were once regional culinary markers are now shared by all members of the greater Indian community.

Culinary continuity is attributed in part to the sizeable Indian presence in southern California. The spices and herbs needed to prepare most Indian dishes are easily accessible from shops located throughout the region. And those that are not readily available are cultivated in homegardens or brought directly from India. Moreover, given the region's large and diverse immigrant population, there is a general acceptance of cultures and the cultural traditions of immigrants. There is no sense of embarrassment among the Indian community regarding their food choices; rather, they are proud of their culinary heritage, and are keenly interested in transferring these traditions to the next generation. Respondents reported that gender is a significant feature of the intergenerational passage of culinary knowledge. And despite ongoing challenges to traditional gendered roles, the Indian immigrant community in southern California adheres in many respects to the traditional role of women in the household. This translates in almost all instances to Indian women passing their knowledge of herbs and spices to their daughters and daughters-in-law. Moreover, the strong community that exists through connections—both physical and technological—through social media outlets and ethnic enclaves, empowers Indian women immigrants in southern California to have a strong sense of cultural identity that they are passing to the next generation.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions generated for the study are included in the article/supplementary material; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by IRB, California State University, Fullerton. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author Contributions

EJ contributed 75% of the research and writing. RV contributed 25% of the research and writing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the women who participated in this study for sharing their knowledge of Indian herbs and spices, and cuisine in general. We also thank California State University, Fullerton, for providing funding for the research through a Jr/Sr Grant.

References

Acharya, S., and Acharya, L. (2008). Boundaries of gender and ethnicity: Gujarati Hindu Women in Artesia's “Little India”. Amerasia J. 34, 37–51. doi: 10.17953/amer.34.3.f63426546u4613w6

Bailey, A. (2017). The migrant suitcase: food, belonging and commensality among Indian migrants in the Netherlands. Appetite 110, 51–60. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2016.12.013

Ban, N., and Coomes, O. (2004). Home gardens in Amazonian Peru: diversity and exchange of planting material. Geogr. Rev. 94, 348–367. doi: 10.1111/j.1931-0846.2004.tb00177.x

Benson, H., and Helzer, J. (2017). Central Valley culinary landscapes: ethnic foodways of Sikh transnationals. Calif. Geographer. 56, 55–95.

Chandra, S. (2016). Ayurvedic research, wellness and consumer rights. J. Ayurveda Integr. Med 7, 6–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jaim.2016.05.002

Dafni, A., Petanidou, T., Vallianatou, I., Kozhuharova, E., Blanché, C., Pacini, E., et al. (2020). Myrtle, basil, rosemary, and three-lobed sage as ritual plants in the monotheistic religions: an historical-ethnobotanical comparison. Econ. Bot. 74, 330–355. doi: 10.1007/s12231-019-09477-w

Dalby, A. (2000). Dangerous Tastes: The Story of Spices. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Dhandapani, S., Subramanian, V. R., Rajagopal, S., and Namasivayam, N. (2002). Hypolipidemic effect of Cuminum cyminum L. in alloxan-induced diabetic rats. Pharmacol. Res. 46, 251–255. doi: 10.1016/S1043-6618(02)00131-7

Etkin, N. (2009). Foods of Association: Biocultural Perspectives on Foods and Beverages That Mediate Sociability. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press.

Fischler, C. (2011). Commensality, society and culture. Soc. Sci. Information 50, 528–548. doi: 10.1177/0539018411413963

Flitsch, M. (2011). Hesitant hands on changing tables: negotiating dining patterns in diaspora food culture transfer. Asiactische Stud. 65, 969–984.

Freedman, P. (2008). Out of the East: Spices and the Medieval Imagination. New Haven, CN: Yale University Press.

Gabaccia, D. R. (2009). We Are What We Eat: Ethnic Food and the Making of Americans. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Gupta, A. (2012). “A different history of the present. The movements of crops, cuisines, and globalization,” in Curried Cultures. Globalization, Food and South Asia, eds K. Ray and A. Srinivas (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press), 29–46.

Helzer, J. (1994). Continuity and change: Hmong settlement in California's Sacramento Valley. J. Cult. Geogr. 14, 51–64. doi: 10.1080/08873639409478373

Hema, R., Kumaravel, S., and Alagusundaram, K. (2011). GC/MS determination of bioactive components of Murraya koenigii. J. Am. Sci. 7, 80–83.

Hemphill, L., and Cobiac, L. (2006). Health benefits of herbs and spices: the past, the present, the future. Med. J. Austral. 185, S5–S17. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2006.tb00548.x

Hoffman, B., and Gallaher, T. (2007). Importance indices in ethnobotany. Ethnobot. Res. Appl. 201, 201–218. doi: 10.17348/era.5.0.201-218

Joseph, S., and Peter, K. V. (1985). Curry leaf (Murraya koenigii), perennial, nutritious, leafy vegetable. Econ. Bot. 39, 68–73. doi: 10.1007/BF02861176

Kang, H. (2013). Korean American college students' language practices and identity positioning: “not Korean, but not American”. J. Lang. Identity Educ. 12, 248–261. doi: 10.1080/15348458.2013.818473

Kessler, C., Wischnewsky, M., Michalsen, A., Eisenmann, C., and Melzer, J. (2013). Ayurveda: between religion, spirituality, and medicine. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2013, 1–11. doi: 10.1155/2013/952432

Kuk, N. J. (2014). Medieval European medicine and Asian spices. Korean J. Med. 23, 319–342. doi: 10.13081/kjmh.2014.23.319

Malav, P., Pandey, A., Bhatt, K. C., Krishnan, S. G., and Bisht, I. S. (2015). Morphological variability in holy basil (Ocimum tenuiflorum L.) from India. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 62, 1245–1256. doi: 10.1007/s10722-015-0227-5

Mannur, A. (2009). Culinary Fictions: Food in South Asian Diasporic Culture. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

Morton, T. (2000). The Poetics of Spice: Romantic Consumerism and the Exotic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Murugan, S. M., Deepika, R., Reshma, A., and Sathishkumar, R. (2013). Antioxidant perspective of selected medicinal herbs in India: a probable source for natural antioxidants. J. Pharm. Res. 7, 271–274. doi: 10.1016/j.jopr.2013.04.023

Muthu, C., Ayyanar, M., Raja, N., and Ignacimuthu, S. (2006). Medicinal plants used by traditional healers in Kancheepuram District of Tamil Nadu, India. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2, 1–10. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-2-43

Narayan, U. (1995). Eating cultures: incorporation, identity, and Indian food. Soc. Identities 1 63–86. doi: 10.1080/13504630.1995.9959426

Natrajan, B., and Jacob, S. (2018). ‘Provincialising’ vegetarianism: putting Indian food habits in their place. Econ. Polit. Wkly. 53, 54–64.

Parasecoli, F. (2014). Food, identity, and cultural reproduction in immigrant communities. Soc. Res. 81, 415−439.

Roy, P. (2002). Reading communities and culinary communities: the gastropoetics of the South Asian diaspora. Positions East Asia Cultures Critique 10, 471–502. doi: 10.1215/10679847-10-2-471

Rumbaut, R. G. (2008). The coming of the second generation: immigration and ethnic mobility in Southern California. Ann. Am. Acad. Pol. Soc. Sci. 620, 196–236. doi: 10.1177/0002716208322957

Sherman, P. W., and Billing, J. (1999). Darwinian gastronomy: why we use spices. Spices taste good because they are good for us. BioScience 49, 453–463. doi: 10.2307/1313553

Singh, S., More, P. K., and Mohan, S. M. (2014). Curry leaves (Murraya koenigii Linn. Sprengal) – a miracle plant. Indian J. Sci. Res. 4, 46–52.

Siruguri, V., and Bhat, R. V. (2015). Assessing intake of spices by pattern of spice use, frequency of consumption and portion size of spices consumed from routinely prepared dishes in southern India. Nutr. J. 14:7. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-14-7

Srinivasan, K. (2010). “Traditional Indian functional foods,” in Functional Foods of the East, eds J. Shi, C. T. Ho, and F. Shahidi (Boca Raton, FL: Taylor & Francis Group), 51–84. doi: 10.1201/b10264-4

Srivastava, J., and Vankar, P. S. (2012). Antioxidant profile in North Eastern India: traditional herbs. Nutr. Food Sci. 41, 26–33. doi: 10.1108/00346651211196500

U.S. Census Bureau (2017). Selected Population Profile in the United States, 2016 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates. Available online at: https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=ACS_16_1YR_S0201&prodType=table

United Nations (2020). World Migration Report 2020. Geneva: International Organization for Migration. Available online at: https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/wmr_2020.pdf

Vallianatos, H., and Raine, K. (2008). Consuming food and constructing identities among Arabic and South Asian immigrant women. Food Cult. Soc. 11, 55–373. doi: 10.2752/175174408X347900

Vandebroek, I., and Voeks, R. (2018). The gradual loss of African indigenous vegetables in tropical America: a review. Econ. Bot. 72, 543–571. doi: 10.1007/s12231-019-09446-3

Voeks, R. (2018). The Ethnobotany of Eden: Rethinking the Jungle Medicine Narrative. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Vu, V., and Voeks, R. (2012). Fish sauce to french fries: changing foodways of the Vietnamese diaspora in Orange County, California. Calif. Geographer. 52, 35–55.

Wallendorf, M., and Reilly, M. D. (1983). Ethnic migration, assimilation and consumption. J. Consum. Res. 10, 292–302. doi: 10.1086/208968

Warmington, E. (1928). Commerce Between the Roman Empire and East India. Cambridge: The University Press.

Zhou, M., Tseng, Y. F., and Kim, R. (2008). Rethinking residential assimilation: the case of a Chinese ethnoburb in the San Gabriel Valley, California. Amerasia J. 34, 55–83. doi: 10.17953/amer.34.3.y08124j33ut846v0

Zong, J., and Batalova, J. (2017, August 21). Indian immigrants in the United States. Migration Information Source. Available online at: http://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/indian-immigrants-united-states

Keywords: Indian diaspora, cuisine, gastronomy, herbs and spices, homegardens

Citation: Joseph E and Voeks R (2021) Indian Diaspora Gastronomy: On the Changing Use of Herbs and Spices Among Southern California's Indian Immigrant Women. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 5:610081. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2021.610081

Received: 25 September 2020; Accepted: 01 March 2021;

Published: 29 April 2021.

Edited by:

Michele Filippo Fontefrancesco, University of Gastronomic Sciences, ItalyReviewed by:

Jayeeta Sharma, University of Toronto, CanadaRodolfo Maggio, University of Turin, Italy

Copyright © 2021 Joseph and Voeks. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Robert Voeks, cnZvZWtzQGZ1bGxlcnRvbi5lZHU=

Elois Joseph

Elois Joseph Robert Voeks

Robert Voeks