- 1University of Natural Resources and Life Science, BOKU, Institute for Development Research, Vienna, Austria

- 2TMG Thinktank for Sustainability, Berlin, Germany

- 3Heinrich Boell Foundation Southern Africa, Cape Town, South Africa

- 4Food Agency Co-research Group, Cape Town, South Africa

The COVID-19 pandemic and its control measures had a devastating impact on household food security in South Africa. The pandemic brought existing food injustice patterns, such as spatial inequality, intersectionality, and the causes of food poverty to the forefront, especially for women. It also galvanized momentum in the people's agenda for solidarity and stimulated community members' calls for an overhaul of the existing commercialized food system toward hyper-localized, community-led solutions such as food dialogs and community kitchens. First and foremost, that meant talking about hunger and addressing its root causes. This paper reports on a co-research process on household food security during the pandemic in four neighborhoods of the Cape Flats. This study found that household food insecurity and the roles women play in food systems are significantly shaped by intersectionality: the consequences of being women, Black or Persons of Color, residents of geographies of social and economic marginalization within the city, and historically excluded from higher education. In this paper, we provide reflections on the co-research process from the perspectives of co-researchers, the project coordinator, and the project funder by applying a critical feminist framework and by answering the question: How can critical feminist research steer community-led action? Community members from the Cape Flats and five post-graduate students from a Berlin-based institute conceptualized this study and it was implemented by community researchers and projects partners in 2020. The paper highlights important aspects of the methodology, particularly the joint contextualization and sense making of findings by community researchers who placed food insecurity results in the context of their lived experiences. Based on their discussions, the co-researchers created visions for post-COVID-19 food environments, one of which is discussed in this paper: destigmatization of hunger. Hunger was described by co-researchers as a problem hidden by individuals and silenced by communities.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic and its lockdowns resulted in immediate economic shocks and a lasting aggravation of household food insecurity. South Africa was identified as a “hunger hotspot” as the first lockdown exacerbated hunger in vulnerable households (Oxfam, 2020, p. 1). A nation-wide survey found that “while some households have managed to recover from the initial devastating effects of the pandemic and hard lockdown, a large proportion of households remain economically extremely vulnerable” (Van der Berg et al., 2021, p. 5). The burden of food insecurity in South Africa is carried by Black women (Cock's, 2016). An intersectional lens is required to understand the role of women and food security which goes beyond questions on access and production and is situated in power struggles, invisibility of care work, and constraining relationships and discourses (Lewis, 2016).

This paper reflects on a 1-year post-graduate programme offered by the Center for Rural Development (SLE) at Humboldt University of Berlin which examined food security in marginalized communities in the Western Cape during the COVID-19 pandemic (see Paganini et al., 2021). Here, we share three perspectives on the study: the community members, the project coordinator, and the funder. At the same time, we show how critical feminist research steered community-led action.

The SLE course normally allows five post-graduates to conduct 6-month empirical field research in a country in the South; however, due to COVID-19 travel restrictions, planned projects were canceled and the SLE improvised and designed remote projects, relying on existing research partners to activate remote studies. While SLE was reconfiguring their post-graduate overseas programme component, one of their project partners, an urban farmer in Cape Town, was grappling with the market losses facing small-scale farmers and the growing resulting threats to food security, especially in the so-called “townships.” She sought collaborative, community-driven research to quantify the effects of COVID-19 restrictions on food security to better position her community to advocate for change (see Buthelezi et al., 2020; Paganini et al., 2020). Her vision transpired as a co-research study1 co-developed and conducted by community researchers (referred to as co-researchers) and an interdisciplinary team of SLE students who hold master's degrees in development studies, food security studies, natural resource management, geography, and political science. The team was accompanied by a team coordinator (the first author) and supported by an academic advisor and South African partners from civil society organizations. Their joint research generated qualitative and quantitative findings on the state of food security through a household survey, the development of an agency index, and a place-based perspective through photovoices and food environment maps. The study generated transformative impacts on the community level and inspired plans for a pilot community-driven, cross-sectoral platform in which hunger is destigmatized through care-guided conversations, food agency is progressively nurtured, and local food dialogs are formed. The current paper builds on the final report of the larger study described above (see Paganini et al., 2021) and contextualizes the study's co-research process, results, and recommendations using Donna Andrews' critical feminist framework (2020).

The present paper narrows in on a central finding identified by female co-researchers: the urgent need to destigmatize hunger. The shame of being food insecure is often felt, reinforced, and exemplified by women. In joint reflections, the authors were inspired by Hayes-Conray and Hayes-Conray and their work on critical feminist reflections on food and place (2008), Cock (2016) notion of the nexus of intersectionality and food insecurity, eco-feminist and activist Andrews (2020) framework for guiding socio-ecologically transformative research, and Lewis (2015) work on gender and feminism in food research, particularly in the Western Cape. Lewis' general critique of food security studies is that they often aim to respond to crises with statistics and “prioritize productivity, immediate results and short-term solutions, often ignoring the over-arching processes” (Lewis, 2015, p. 3). Lewis encourages feminist approaches in food security research to unearth root causes of broken systems and power struggles by shifting away from the notion of increasing food production and availability for the poor. She recognizes that marginalized voices are largely excluded in mainstream food security research and, like Freire (1970), encourages research that solicits marginalized voices, links hunger, and dignity, and actively responds to communities' self-identified food and hunger challenges as a way of knowledge creation and empowerment. It is from these perspectives that we argue that a critical exploration of food insecurity requires more than merely monitoring numbers.

Research Context: Place and Space

Cock's (2016, p. 122) asserts the South African food regime is “profoundly unjust” and ecologically unsustainable and that African working-class women bear the brunt of this reality. Women face hunger more often than men due to disparities in income, limited access to employment or means of production, and cultural practices that put them last or allow them smaller portions when food is in short supply (Oxfam, 2020). Due to the gendered division of labor, women are burdened with food and energy provisioning and the unpaid care work of the young, elderly, and sick (Cock's, 2016; Swanby, 2021). It is for these reasons that women often lead struggles to transform food systems (Andrews, 2020).

Our study was conducted in Cape Town, South Africa. The research sites are located in the Cape Flats, which are built on a low-lying, flat area east of the city center. This former military area and dumpsite was populated during the apartheid era with so-called “townships” where People of Color were forcibly relocated from the city center and economically displaced internal migrants from rural areas settled. The country's spatial planning separated people by race to make it easier for the apartheid government to control access to resources by race. Until today, the city's spatial design is characterized by racial segregation with Black and People of Color communities sequestered on the outskirts of the city.

This racially segregated spatial planning created an intersection between food security and location and persists in how food systems aregoverned (or not governed) while perpetually continuing to reproduce inequalities. Site-specific differences were noted in the four research sites and possibly attributed to the formality of the settlement community as well as employment availability for its residents. Khayelitsha, Gugulethu, and Mfuleni are historically Black communities and their occupants' lack of formal employment is a reflection of the quality of education and work opportunities afforded to Black people before 1994. Mitchell's Plain is a historically Colored neighborhood and, during apartheid years, its residents were afforded a different level of education and work opportunities. Mfuleni is a neighborhood with both formal settlements and informal settlements. Female residents of the neighborhood of Mitchell's Plain and Mfuleni are more likely to be formally employed and earn regular salaries than female residents living in the other research sites. Women living in the Black neighborhoods of Khayelitsha, Gugulethu, and Mfuleni are more likely to have temporary or casual jobs and thus a higher risk of food insecurity.

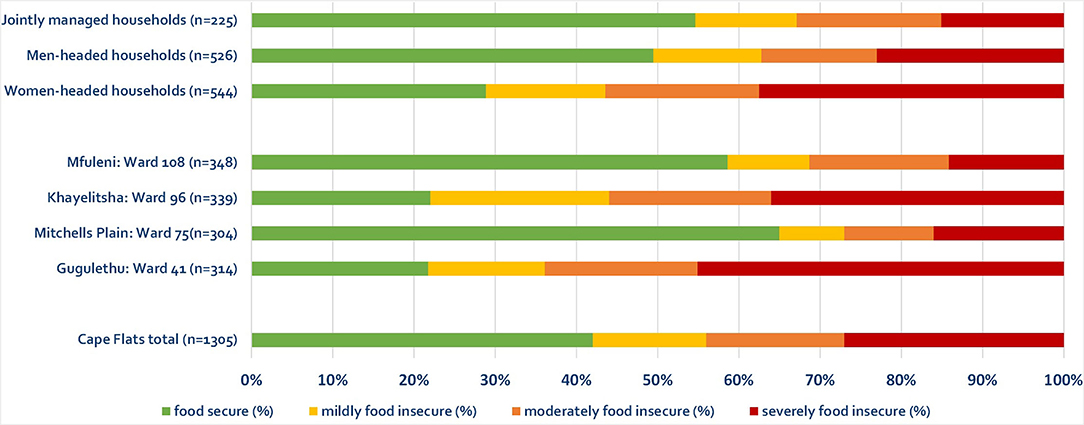

The four neighborhoods differ significantly, yet all areas are characterized by high unemployment. The highest level of unemployment was found in Khayelitsha, with 73% of respondents unemployed, followed by 66% in Gugulethu, 45% in Mitchell's Plain, and 38% in Mfuleni. Not surprisingly, these areas are also distressed by food insecurity. Ranking using the Food Insecurity Experience Scale (FIES) revealed 44% of households in these areas are food insecure, with woman-headed households more often severely food insecure (38%) than male-headed households (23%) and jointly-managed households2 (15%). The correlation between unemployment and food insecurity is clear: 45% of respondents from Gugulethu are severely food insecure and 66% are unemployed, for example. Similarly, 36% of respondents in the Khayelitsha site are severely food insecure and 73% are unemployed. Figure 1 provides further evidence of this.

Figure 1. Food Insecurity Experience Scale (FIES) rating of four communities in the Cape Flats in September 2020, by gender of household head and location.

From Research to Community-Led Action

As co-researchers came to realize the severity of the state of food insecurity in their own communities through the study, they continuously reminded the project team in project meetings and feedback calls to create an environment in which decision makers and people with power talk with them, not about them and not without them. Their previous experience with research had exposed them to multiple rounds of data harvesting yet they had not experienced immediate impacts from the research activities. They critiqued other food security research projects for focusing on statistics and excluding their lived experiences and, thus, demanded that their voices be heard in the current study.

The network of co-researchers challenged its project partners to avoid power imbalances, for example, co-researchers and academically affiliated researchers or men and women, and to put mechanisms in place to identify, discuss, and counter those power imbalances. In a joint reading and writing retreat, we questioned the ontological basis of the hegemony that drives inequality and injustice in our food system and and the research paradigms of colonized educational institutions conducting work in countries in the South. The reification of the intellect and vilification of the body, emotion, and the material world by a rational ontology is key to a culture of domination, exploitation and imperialism (Shiva, 1994; McClintock, 1995; Merchant, 2006). New materialist feminist works by scholars such as Haraway (1988), Barad (2007), and Grosz (2010) show that biology and matter are shaped by multiple forces, but at the same time also have agency in forging social and political realities (Frost, 2011). Our research methodology therefore sought to take the subjective and the visceral into account. Indeed, when co-researchers presented the findings in community feedback workshops, they were always at pains to point out that “there are human beings behind these numbers,” human beings with unique stories, feelings, and motivations. We wanted to bring forth a relationship with micro- and macro-sociologies, allowing us to take political and economic insights from daily activities and focus on the production of the social world at the everyday event. We also drew from decolonial literature which emphasizes relationality, acknowledgment of non-human agency, and the particular and concrete as opposed to the abstract and universal (Tuck and McKenzie, 2015). Decolonial scholars note that the academic imperative to find universal truths through aggregating results and abstracting findings that can be generally applied effectively negates place-based and indigenous knowledge (Shiva, 1994).

A wish to address these issues and acknowledge the relational culture of the Cape Flats led us to the guiding question of this paper: How can critical feminist research enhance community-led action?

A Critical Feminist Research Framework

Feminist research is often qualitative research and applies methods such as in-depth interviews, participatory observations, contextualization, and reflections on the findings. It creates space for listening and sharing emotions.

To situate our research results, we used a critical feminist research framework developed by African eco-feminist scholar and activist, Andrews (2020), as a lens. Andrews' framework lays out a guide for research that aims for socio-ecological transformation. It is based on three main tenets, which we explore further in this section as related to our work. In her analysis, research for socio-ecological transformation should have (1) eco-feminist conceptions of earth democracy and earth justice at its heart; (2) awareness of the gaze and costs of solution-oriented research; and finally, (3) researcher recognition of positionality and ideology. These principles resonate powerfully with the experiences of women researchers on this project; we expand on this in Section Reflection on the process, providing reflections from different perspectives according to our roles in the process.

Eco-Feminist Conceptions of Earth Democracy and Earth Justice

The eco-feminist notion of earth democracy is a transformative paradigm that struggles against capitalist patriarchy and seeks to dismantle the hegemony that incentivizes exploitation, extraction, and control by the elite (Andrews et al., 2019). Women suffer multiple layers of oppression and violence while abundance and comfort is produced at the expenses of nature, women, and the working class (Merchant, 1989). Due to the unfair division of labor in the patriarchy, womens' invisible and unpaid reproductive work maintains and subsidizes the neoliberal food regime (Andrews, 2020). This requires us to move beyond violent economy and patriarchy toward respect for women and the Earth (Shiva, 2013).

“It is in the face of systemic violence—which is inherent in patriarchal capitalism and underpins the current ecological crisis—that women's individual and collective struggles for the right to food and nutrition are located” (Andrews et al., 2019, p. 7). Shiva (2005) lays out principles of earth democracy which include species' intrinsic value and interconnectedness; defense and promotion of species diversity; protection and reclamation of commons; protection of all ecosystems and the right to all basic needs and subsistence for all; localization; unity; and dignity, peace, and compassion for all life forms. The co-research methodology that we used acknowledges these structural and visceral issues that contextualize and inform food work. It creates spaces for these issues to emerge and unfolds learning processes for understanding the meaning of each issue's individual and collective role within the food system. For example, in our triangulation and findings feedback workshops, an eco-feminist approach enabled analysis and solutions to be strongly premised on the desire to strengthen and draw on community, family relations, and indigenous cultural practices. Here, co-researchers prepared a two-day workshop to present findings, guide community members through food and power systems maps, exhibit photovoices, and showcase music and poems related to food. While typical development themes of markets, livelihoods, and production methodologies emerged from this workshop as necessary areas of focus, there was a constant return to meeting the sustenance needs of people who are “falling between the cracks” in local communities and meeting those needs with dignity. There was however, no naivety in regard to understanding the many “lock-ins” (Frison, 2016) to our current food systems and the challenges implicit in imagining a radical transformation of existing normalities. For example, strong recommendations were to review related policies to assess how they privilege actors in the industrial food system and to advocate for enabling policy for small and micro food producers and informal traders.

The Gaze and Costs of Solution-Oriented Research

Solution-oriented research often creates one-size-fits-all, output-driven solutions based on technological fixes, replacing and renewing limited natural resources, and setting thresholds for harmful activities (Liboiron et al., 2018) such as pesticide maximum residue levels, fishing quotas, or greenhouse gas emmision caps. This approach seeks to control nature (Merchant, 1989) and extract general insights or truths that can be universally applied (Rosenow, 2019). The imperative of western scholarship to arrive at concrete recommendations through abstraction and generalization renders place-based and subjective knowledge invisible (Rosiek et al., 2019). (Ndlovu, 2014, p. 84) shows that indigenous knowledges have been rendered obsolete by the hegemony and contends that “the idea of indigenous ways of knowing, seeing and imagining the world has the potential of enabling another imagination of the world beyond the now defunct Western-centric one.” Decolonial research should disturb rather than settle, as this is indicative of acknowledging pluralities—the existence of many worlds that may never reach agreement (Rosenow, 2019). Through decolonial research methods, answers and questions are equally valued and the imperative to settle is resisted.

The subjective and the visceral are not easily accommodated in research methodologies that value generalization and abstraction. However, these subjectivities point to emancipatory and transformative pathways, giving access to lived experience, and the structures and networks that are shaped and shape subjective experience. Hayes-Conray and Hayes-Conray (2008) remind us that individual visceral feelings are entwined with the economic structures and systems of meaning-making in which we are embedded. Haraway (1988) contends that true objectivity does not exist in generalizations and abstractions, but rather in the acceptance of partial and subjective perspectives. She makes a strong case for “trusting the vantage point of the subjugated” (p. 584) by tapping into situated and embodied knowledges. These vantage points hold great transformative capacities because they can take us beyond the blind spots of the dominant perspective. Indeed, one of the most powerful ways forward in our research emerged from the identification of feelings of shame and indignity related to food insecurity as stated by one co-researcher:

The hardest was using the space of reflection to put together strategies for solutions: sitting with all these community members in focus group workshops and reflecting on the results and how each individual relates to them. There was a theme of the shame of being poor: the feelings of personal failure as opposed to seeing poverty as a collective issue. Poverty should not isolate people.

This lead to inquiries into the structural, societal, and cultural forces that engender these feelings and solutions extending beyond the quick-fix, technological, and a-political recommendations typical of solution-oriented research.

Researcher Recognition of Positionality and Ideology

Andrews (2020) contends that we need to consider positionality, methodology, and accessibility of the research by asking ourselves what the political objective is. She provided three positions:

(a) Does the research emerge from a preconceived framework constructed in the North, e.g., imperatives to modernize or “develop” ? (Note that such imperatives have been recognized by most governments of the South)

(b) Is the research carried out alongside those who are affected?

(c) Does the research endeavor to bring to the fore the complexity of social-ecological relations?

From an eco-feminist point of view, an important political objective is to ask how we move past exploitative and extractivist systems that are “industrialized, formalized, regulated, extracted, waged, commodified and alienated” (Andrews, 2020, p. 15) to social systems based on reciprocity, care, and wellbeing for people and all living beings. It is important to consider research methodologies that are fit for this task; PAR and co-research methodologies acknowledge and draw on the expertise and vantage points of those affected and make a concerted effort to understand the research findings within discursive, historical, and structural contexts. Of great importance is that we, as researchers, continuously share and reflect on our work, positionality, and feelings amongst ourselves as well as with the larger activist-scholar community to gain reflection and introspection on our work. We conducted a 2-day reflection retreat with the core team of co-researchers to critically think about what the research has and has not achieved and which of our own ideologies and positions influenced the research. Relatedly, a desire emerged from the feedback session to bring co-researchers into the academic canon with the vision of being able to cite authors from local communities rather than exclusively more distant scholars.

An important guideline for socio-ecological transformation that we learned from Andrews (2020) is that research cannot be substituted for activism and civil society work in democratic society. Therefore, it was crucial for this group of co-researchers to reconnect with their communities and civil society organizations to share their findings and collect feedback. This contextualization of findings grounds research in actual community needs rather than the research questions posed by academics.

Methodology And Research Design

The methodology used to gather food security statistics was designed and adapted by a remote team of five post-graduate students steered by an advising researcher in Cape Town and a coordinator in Berlin. However, the study is grounded in co-research, an inclusive and radical approach to participatory action research. In co-research, the main actors (community members) are involved in planning, coordinating, and implementing the methods while assuring quality through constant triangulation and intense contextualization of the findings. The joint sense-making of the findings is “a key component of individual agency and collective adaptive capacity” (Vanderlinden et al., 2020, p. 2). The research process was informed by ongoing and frequent interactions and aimed at developing long-term visions and debates on the transformation of food systems. Building and owning these visions is slow work based on iterative learning processes to ground communities' understanding of root causes of vulnerability before forging forward. Co-researchers were urban farmers from Cape Town, fisherwomen, and other food actors, such as food activists and community kitchen chefs, who drove this participatory research despite and because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

A quantitative household survey was conducted in four research sites in the Cape Flats of Cape Town to generate a representative picture of food security in the communities, coping strategies employed during the pandemic, perceived agency, and power to instigate change in their food system. With a total sample size of 1,824 households, the survey is statistically representative with a confidence level of 95%. Data collection by co-researchers was supported by enumerators and the team used the KoBoToolbox. Interviews were conducted in person or over the phone or digitally by the respondents themselves, making use of social media groups. To measure food security, we applied the FIES (Food Insecurity Experience Scale) tool developed by the FAO's Voices of the Hungry Project. This is a metric, experience-based scale that ranks food security status in four categories: food secure, mildly food insecure, moderately food insecure, and severely food insecure.

This paper focuses primarily on the insights of individual team members who looked back on the project and drew lessons from the critical feminist framework. A central result is that dynamics emerged in the research process that could not have been planned in advance in the research design. The easing of COVID-19 restrictions in the spring of 2021 allowed 3 months to flush out qualitative aspects of the research through in-person workshops, reflection discussions, and less conventional methods which provided space for creativity, abstraction, and emotions: sharing poems and music, dancing and yoga to shake off feelings that emerge when talking about hunger, photovoices, results dissemination in communities, and joint production of a podcast.3 The contextualization and the profound focus on contextualization framed the quantitative results and gave weight to the co-researchers' insight that they are part of the food insecurity numbers.

Reflection On The Process

This research was a multi-authored work; it speaks with many voices and mirrors the unique working and writing styles, passions, and learnings of each contributor. In the following sections, different team members speak about their experiences and observations with the research methodology and findings: the co-researchers, the study coordinator, and one of the project partners and funder. The following sub-sections are the original writings of each team member.

The Co-researchers' Perspective

Being part of a food-insecure community makes the co-researchers' perspective intrinsic when formulating thinking around food security research, even though their lived experience and often-invisible daily coping and survival strategies don't usually make it into the statistics and academic papers. Food security is usually explained by data-driven entities who cannot approximate the reality and daily emotions of a person who experiences food insecurity. The co-researchers' unique positioning as fellow community members allowed them to get the stories behind the numbers.

Researching the effects of COVID-19 on food security and agency in South Africa allowed co-researchers to learn and ask significant questions and tease out answers to the “whys?” Asking questions such as “How many meals did you have today?” or “How often did members of your household experience hunger this week?” allowed us to talk and come upon answers around attitudes toward food insecurity that we, as fellow community members, have internalized but never questioned. In these conversations, we repetitively sensed and observed shame and isolation alongside poverty. People spoke of the shame of having to ask for food; this shame was connected to lack of money and employment. While the research provided the realization that food insecurity is a collective and societal problem, individuals saw their hunger as a personal, shameful issue.

While the issue of shame rocked individual respondents, the co-researchers grappled with anger as they discovered the injustices their marginalized neighbors and neighboring communities faced. This became particularly apparent when discussing the indignity of accessing feeding schemes and so-called “soup kitchens” during times of adversity during the pandemic. Community members expressed difficulties stepping out of one's house to stand in line for food in the public view. A more dignified approach is to understand those kitchens as community places, not merely as soup kitchens where people feel stigmatized as too poor (or lazy) to look after themselves. Through the data analysis, the co-researchers came to see that hunger dominated the lives of the majority of their neighbors and community members and also the lives of members of surrounding marginalized communities. They were not alone. Their problems were not created by themselves as individuals, but handed down to them as victims of historical and structural oppression. Joined in solidarity, their sense of shame dissolved away and was replaced by anger.

Women, in particular, are taught that it is not acceptable to feel and express anger, yet many reported feeling angry about a system that excludes community members from both decision making processes in food systems and knowledge systems classically determined by Western cultures and researchers who rarely involve community voices in their work. Is it location that describes who is part of the majority world but not the majority of power? Or is it knowledge which was, in our case, not accessible for many of us because of our skin color? There was a survey question on education level which continuously elicited a tense response as respondents revealed how little education they had received under the post-apartheid “Bantu” education system. This system afforded People of Color low-quality education that limited many to informal work, burdened them with social and economic exclusion, and encumbered them with shame. Academia itself recognizes intellectual contribution into its space only to its own set standards. You need to be academically affiliated with a post-secondary institution to be published and you need to be able to express your thinking in one of a narrow set of languages. As the drivers and contributors to an academic study, we noted the power of language to exclude many from academia and growth. Cape Town's food environment has an absurd admiration for academics who forge strategic collaborations for us. Although we envision a time when academics do not talk about us without us, we still tend to send the White professor from our team (who works at a university in our city that we don't have access to) to speak on our behalf rather than empowering ourselves to speak with our own voices.

The skill sharing and collaborative learning process used in this study gave us a sense of belonging and unity in communal problem solving. Through this work, a bridge of learning was built between a group of co-researchers and a group of advocacy partners and academics who are dedicated to this slow work. Co-research requires community researchers to transcend unequal power and bring voices into discussions. Co-research helped us understand the colonial educational system and how it has excluded us. Many “poor” and “hungry” people who live in the Cape Flats don't know what many researchers have discovered, written, and recommended for their “poor” and “hungry” research subjects.

Being able to contribute to the analysis of this research and co-design the next research phases made us aware of how research design shapes narratives. As inclusive as this co-research is, there are still boundaries that we can't yet cross. We can't apply for our own grants and we continue to depend on the university affiliation of (foreign) researchers for publishing and project work.

The Coordinator's Perspective

In “normal” years, the learning and training component of SLE's post-graduate studies is conducted in-person overseas; in 2020, COVID-19 travel restrictions forced us to stay at home and encouraged us to test and adapt new remote methods. The research team (co-researchers, enumerators, and remotely working post-graduate students) collected large data sets and learned (and accepted) that the route we take in field research should not always entail a flight path. With a project team on two different continents, questions emerged: How do we hold partner meetings? How do we create a safe space for those who aren't used to digital tools? How can the Berlin students map food environments without being physically present? How can we build connections to people and spaces in unfamiliar contexts? How can our project design meet the needs of both students (who wish to fulfill graduation requirements) and community partners (who have more diverse and urgent survival needs) so that it is meaningful for them beyond their engagement with each other? Here, two aspects were crucial: to ensure safe and secure field research for the enumerators and co-researchers during the pandemic and to ensure appropriate supervision and support for the co-researchers who conducted interviews on a highly sensitive topic with so many interlocking layers of pain within the contested and politicized space of their own neighborhoods.

In the process of collaboratively discovering answers to these questions, we rooted remote research strategies in a mutual agreement on ethics and grounded those in feminist research approaches which actively sought to remove power imbalances between researchers and “the researched.” This was especially important as the involved co-researchers struggle personally with not being recognized as salient opinion holders in the system. The power question should not be answered by saying, “I am doing my research under an eco-feminism paradigm.” That is too naïve, too simplistic, and disrespectful of those team members who are not part of an academic institution that affords participants access to funding and further research opportunities and who are, hence, dependent on those affiliated with research institutions. Only through constant reflection, checking privileges, forward movement, pauses, and adaptation did an adaptive process unfold an adaptive process that enabled trust. However, it is important not to put co-research on a pedestal as a silver bullet alternative to conventional research. These processes require time, solid relationships, and unfoundering commitment to a deep dive into the messiness of human relationships.

Often, these components don't fit into the ever-faster world of academia. Indeed, the short-term nature of the the SLE programme meant the important phase of contextualizing the findings happened after the Berlin-based students left the programme and missed an incredible, unique opportunity to observe how research transformed into community-led action. Simultaneously, the co-researchers stated they would not have delved into and shared personal experiences during results contextualization in the presence of “outsiders” around them. Here, co-researchers constantly spoke about creating safe spaces and they understood those spaces as places which are not associated with conventional knowledge and power systems such as university buildings or Zoom calls. They felt more comfortable holding in-depth conversations in Mama Hazel's kitchen using their own cultural norms to discuss sensitive topics; very often, questions and answers were not related to their own personal experiences, but raised as personal abstractions, hypothetical situations, or stories from their sisters, mothers, and grandmothers.

The results contextualization was carefully guided by the co-researchers who invited community members to a 2-day community food dialog to digest the results and co-develop visions for future action. Understanding the results as a research team was an important part of the co-research approach. To this end, three visions for reshaping post-COVID-19 food systems were written up by co-researchers based on their understanding of the findings. The iterative process to understand research findings on their lived experience gave depth and perspective to the co-researchers' data (as per Maguire, 2001). The following is a summary of the vision “Destigmatise hunger and increase individual agency by understanding systemic causes of food security” and discussion as per Andrew's framework originally presented in Paganini et al. (2021, p. 126–128):

We learned about deep struggles to put food on the table, heart-breaking stories of women who give their bodies for food, and the levels of (silent) violence people face in their searches for food. Sharing these experiences was perceived as a painful process for co-researchers, but powerful in the same way, leading to a few “a ha!” moments during contextualization sessions and the consolidation of our common theory of change. A first “a ha!” amongst enumerators, co-researchers, and the study team was that hunger is not an issue created by individuals, but societies; yet individuals (both male and female) carry the burden of guilt and shame associated with hunger. This is a profound injustice, given that their situations, when dealt with individually under a cloud of shame and secrecy, are very much uncontrollable and unsolvable.

The co-researchers came to understand that food insecurity and household hunger is systemic rather a result of personal incapability. While participants focused their energies on coping strategies which addressed their personal capacity to produce food (planting food, selling food, or making use of marine resources), these solutions do not address the systemic nature of the problem. Co-researchers who had been involved in years of research on food justice had a greater understanding of systemic issues and encouraged community dialogue and advocacy work to overcome shame and stigma and to address food insecurity through societal change. This requires us to think about how to change a deeply entrenched narrative, but also to think about the words we use. This is echoed in the communities' strong recommendation that soup kitchens be renamed community kitchens to shift the welfare narrative and allow communities to take control of the food in these kitchens for building healthy and vibrant local economies. The power to label things is a political question and something we should look at in our research practice: who is naming things?

This process of putting thoughts onto paper created a great sense of ownership; in the end, it is the community who has the power to leverage visions into action. In that process, it was compulsory to acknowledge local wisdom and observational, traditional, and indigenous knowledge as of equal importance to what we learn at school and university and not downgrade it as life experience.

We learned digital and remote research cannot be implemented as a spontaneous and fast-track form of PAR and that contextualizing findings must be performed jointly to bring ownership to the communities and, therefore, elongate the project duration and amplify the scalability of the project and its recommendations. It is important to note that this study would not have been possible without the co-researchers, but it would also not have been possible without five team members working remotely from Berlin who, although they had no personal connection and had never been to Cape Town, carried out the project with great ambition and creativity. Their main tasks were to develop and steer the household food security study, conduct key informant (expert) interviews, organize remote mapping, design factsheets, and write up the results.

It is nevertheless important to constantly question the process and one's own bias and interest and internalize introspection. The important thing here is that White (or privileged) researchers do not perceive that it is enough to generously make space and give room to the voices of community members in workshops or virtual spaces. Rather, we should openly contemplate our own power, acknowledge the power of academia and the colonial structures that determine our research institutions' and donors' processes, and consider the feelings (intimidation) of participating co-researchers who have historically been excluded from academia. Several times, co-researchers reminded us that, as academics, we are part of an oppressive system; therefore, we must weigh up how we organize ourselves; who coordinates the team; who speaks for whom, when, and how; and which voices are elevated.

This adaptive approach to doing community research allowed us to involve more and more people in dialogs to co-develop their theories of change as articulated by Vanderlinden et al.'s co-research work that states, “Along the way, we reflected, and are still reflecting, on a world that changes, and on the ways we and our partners changed along the way” (2020, p. 3).

A Funder's Perspective

Funding guidelines and bureaucratic instruments in the international cooperation field often narrow on timebound, measurable outcomes, and reporting requirements. Funds allocated for human resources are frowned upon and treated with suspicion, with a preference for supporting “project costs” such as printing, travel, or equipment. Yet, investing in open-ended processes, particularly those seeking to foster women's abilities to assert their lived experience as a valid form of knowledge, is key to decolonial and feminist work. Both a rethinking of “which way of knowing and what kind of knowledge is most helpful at a time that cries out for affirmation of life” (Salleh, 2017, as cited in Walters and von Kotze, 2021, p. 49), as well as a change in who is recognized as “knowing” is necessary if one is to begin to transform deeply embedded and overlapping systems of apartheid, colonial, patriarchal, and economically extractive relations.

Working in this way on questions of food justice could be a particularly powerful intervention. The structure of food systems is at the heart of commodification and the exploitation of both labor (paid and unpaid) as well as ecosystems. Simultaneously, food is at the heart of community relations, family, and cultural identities.

Launched at the height of the COVID-19 crisis, a period that forced a reckoning with the inequitable distribution of resilience capacities in South Africa, this food justice co-research provided an open-ended process for reflection and knowledge and network building focused on food injustice. Initially, however, the project was not framed in this way. Originally, according to the project documentation produced in partnership with the Heinrich Boell Foundation4 Cape Town office (HBF CT), the study would ambitiously seek to answer the following questions:

1. How has COVID-19 impacted the state of food and nutrition security in Cape Flats households?

2. What coping strategies did households use to survive the negative impacts of COVID-19 on their food security?

3. How does the community imagine just and resilient post-COVID-19 community food systems? What opportunities exist for a more just food system?

4. Where are smallscale food producers and processors based?

5. What does this information suggest with regard to municipal and provincial policy interventions?

6. What options exist both within and outside the state to support smallscale producers and processors?

While the research explored these questions, its real insights and gains had to do with the act of opening up conversations in Cape Town's marginalized neighborhoods to talk about hunger and problematize its stigmatization. At the heart of this was the empowerment of a group of (primarily) female co-researchers, many of whom had also been food producers, some of whom had not engaged in systematically questioning the food system or its governance, and some of whom had previously cooperated in co-research on food justice. While seemingly minor, this outcome provides a powerful basis for the collective rethinking of food as a commodity and a private problem as well as a foundation for building localized food system governance structures aimed at justice.

Why did HBF CT recognize the gains of opening conversations as opposed to delivering neatly packaged solutions? In its work to support activism for ecological, social, and economic justice in the region over the past 20 years, HBF CT gained the institutional knowledge that supporting the work of individual activists and loose networks is as important as supporting “blue chip” NGOs. For all its brilliance, South African civil society's roots remain shallow (Friedman and McKaiser, 2009), inadequately representative of or driven by the country's economically marginalized majority, and reflective of the deep divides across class, race, and geography that were formed by apartheid and colonialism. Enabling the development of political agendas and work from “the margins” requires recognition that not all actors can manage donors' bureaucratic burdens.

This has meant building systems and practices that enable partners to work with flexibility, namely valuing grassroots work, and recognizing the challenges faced by grassroots activists. This recognition and appreciation is something that has been built across all parts of the organization (programmatic, administrative, and finance). It is enabled by a leadership that values the knowledge and experience of local staff and trusts them to work independently via their own priorities. While the research was tightly framed, the HBF allowed its “deliverables” and values to shift in recognition of the importance of grassroots activism.

It is not unusual for civil society work, even that dedicated to decolonial and feminist transformations, to itself wrestle with problematic power relations and this project was no different. Although the project team was dominated by women, it was neither simple to assert the legitimacy of a feminist lens nor bypass deeply etched markers of status and power including gender, age, and professional status. These struggles played out between the students and the co-researchers and, once the students were gone, between the co-researcher group itself, as well as with the academics accompanying it. The most common expression was an emphasis on White men with professional status as both interlocutors and audience. While these individuals no doubt are strategically positioned and hold power that must be engaged, it was clear that engaging them without falling into the performance and reproduction of existing hierarchies required careful and strategic thinking. While the coordinator acted as a buffer between donor interests and the research team, these interests, as expected, influenced the process and its outcomes. The strategy was to make donor input transparent and subject it to collectivized processes.

Discussion

In this co-research, participating communities did not focus on results related to food security statistics, but explored the issues at the heart of those statistics that are found inside the homes. Donna Andrews' paradigm (2020) encourages rooting eco-feminist work in the South in concepts developed in the South, this research gained depth and meaning through the contextualization in a large community workshop.

Talking Food in Community Kitchens

In a joint sense-making process, co-researchers explained results to their wider communities, shared statistical findings (noting that the numbers represent actual human beings), and added their stories to the findings. Women co-researchers set a tone for a more empathetic view of the results and generated a greater understanding that being hungry and economically disadvanted is not a consequence of individual failure, but rather the consequence of traditional marginalization, oppression, and racial discrimination. Two writings by Sanelisiwe Nyaba illustrate her feelings about being poor and her inner conflict in her search for invisibility whilst simultaneously grasping for identity:

I guess then I am poor“Hide your poverty child! They must not see it written on your body the smell of it will water their eyes they may sneeze you out all of you and then they will cover their noses to erase the sight of you.

Well, nobody wants to be forgotten.”

…I grew up in informal settlements. Struggle engulfed my own life and that of those around me. I do not remember feeling poor until I entered school and break time became awkward because I seemed to always lag behind on the way to the tuck shop5. The idea of poverty having to be hidden comes from this experience; no one wanted to know whether you were poor or struggling, the same story became boring. So you did not speak of it until serious inquiries were made: that I did not come to school because I did not have money for transport, that I am late because I spent the first few hours of my morning knocking on neighbors' doors to borrow transport money. At least then you have an identity: the student that stays absent or that is always late or that does not care.

Looking at the individual and collective experience of women behind the findings in the context of a capitalistic and patriarchal food system, the intersection between gender and food transpires, evoking a multitude of well-documented, nearly universal gendered norms which place women at a disadvantage in attaining food sovereignty (Cock's, 2016; Andrews et al., 2019). Land rights and tenure oriented to male ownership impact women's access to food, as does women's heavy responsibilities in unseen care work. Women also face unique safety concerns in accessing food. For example, during the period of politically motivated violence, looting, and civil unrest in the days preceeding former president Zuma's arrest in 2021, many women were unable to travel to work as taxis were targeted and many food businesses, including community kitchens, were temporarily closed. For women, living in an environment shaped by brutal violence limits their financial, mental, and physical wellbeing. The pandemic created a necessity for many women to initiate and operate solidarity initiatives to support themselves, their social capital, neighbors, communities, and extended families.

We contemplated an ideal conversation space and found ourselves in a food dialog in a community kitchen, a place associated with women's stories, discussions, and mutual understanding. Outside kitchens, personal stories are rarely shared and even denied. Destigmatizing hunger and overcoming the compulsion to internalize lack of food as personal failure is an arduous challenge within a culture driven by pride. One co-researcher stated that “culture has put us in the kitchen and culture has muted us.” Women's self-localizations into these hidden spaces perpetuate shame and pain. However, claiming spaces in their own community and in governance processes to express their voices requires a safety net for women and active addressing of structural problems. Rethinking community kitchens is a central solution developed by community members who argue that these spaces should not be reduced to feeding places but rather to nourishing spaces fostering solidarity.

Women's ability to be active and mobilise is rooted in a history of deep-seated exclusion from economic activity, such as the migrant labor system (Vosloo, 2020) which left women at the helm of their homesteads and co-reliant on other women whose husbands were engaged in migrant labor. The present situation is reminiscent of these times as women continue to lead and significantly contribute to society without due credit. The “personal is political” paradigm described by Hanisch (1970) motivated the co-research community to hone the next research phase on methods of destigmatizing food security. Women co-researchers sensed urgency in unpacking the shame around food insecurity and food relief by using stories to share, open, and learn to accept (Hemmings, 2011). One co-researcher phrased this as:

I think being Black puts one in a complicated position where this question of “the personal is political” is concerned. At one point, you're systematically disadvantaged from generations of racial discrimination. On the other, you're a young woman with potential that wants to pursue her dreams. For years, for example, you're unemployed and have trouble putting food on the table. Accepting that you're systematically disadvantaged and explaining your position from this standpoint is only reassuring for so long. Accepting is scary because you risk dying with your dreams, like many others you've seen before. It's hard to accept that. The shame, the fear, the guilt is heavy to carry… There is a bigger fear of letting it go (besides that the insecurity is ongoing) because it means giving up. It means not fighting. I think a large part of Black resilience comes from this pain. Not quite something to be admired if we look at it like this.

Promoting Critical Feminism in Food Research

Andrews (2020) asks how to bring to the fore the complexity of socio-ecological relations, reflect on our positions in this co-research collaboration, and consider knowledge co-creation in food research. Feminist research actively seeks to remove power and imbalances (Lewis, 2015). A pragmatic step to doing this is to make the power and importance of relationality visible by noting which relationships are strong, difficult, or impactful. The research that is most often deployed creates knowledge that is not connected to the realities of localities or inclusive of political and ideological agendas and therefore not able to bring about meaningful change. Critical feminist approaches to food studies have the potential to transcend and challenge dominant forms of scholarship and research on food security (Lewis, 2015).

This desire for equity and our commitment to a feminist, post-colonial research approach is important to us, yet as a mixed-race team, we struggled with it. The more we reflect, the more we struggle. When asked if authors considered themselves feminists, White authors replied positively, yet Black authors answered negatively, reflecting their understanding that feminism was associated with man-hating and trouble-making women. While seeking to find a common language, the concept of feminism was understood by us as strongly linked to seeking social justice, particularly for those oppressed by gender, race, class, and knowledge and information injustice.

Promoting critical feminist research requires a co-developed research design which allows for collective analysis of findings. It requires safe spaces for analysis that are not undermined by unequal power relations resulting from constructs around educational status, yet give credence to anecdotal information, creative expression, and cultural knowledge. Digesting the findings required physical activity (stretching, dancing, laughing) in order to let the findings arrive.

A podcast produced by two co-researchers explains, “It all started with five women on a trip to Scarborough: five women with different lived experiences, but all connected through this research” (Nyaba et al., 2021). This trip aimed at dismantling what we mean by feminism. Contemporary feminism was significantly impacted by the outbreak of COVID-19. Its devastating impact on women, who carried the burden of the pandemic, forced a step back into the private and virtual. Duncan and Claeys (2020) reflected that “… [COVID-19] is a profound and unprecedented global crisis that is exacerbating and leveraging preexistent systemic forms of patriarchal inequalities, oppressions, racism, colonialism, violence and discrimination that cannot be tolerated” (Duncan and Claeys, 2020, p. 6). In the group of co-researchers, Black women were at the forefront of community mobilization, local leadership, and grassroots activism responding to the increasing number of food-insecure households. Interventions were orchestrated mainly by women who advocated for more local food dialogs in their communities and argued with (Chilisa (2017), p. 825): “The unequal power relations between indigenous and western academic knowledge are the greatest threat to any form of collaborative research that seek to address Africa's sustainability challenges.”

Conclusion

After more than a year of virtual conversations, online research and remote work, it is crucial to think about information injustice and the digital divide. Given that virtuality, access to social media and the skills to use it for campaigning is a privilege that may help link the fourth wave of feminism occurring online with real-world politics. We discovered that working across two continents, staying at home due to curfews, and coping with the pandemic meant that much of our work involved digital communication and maneuvering in virtual spaces. While fast wifi is the norm for part of the writing team, access to virtual communication and information is expensive and far from a given for the majority of the wider research team.

This paper reports on different experiences from a short-term study. Central results were the gained understanding that food security research has to go beyond statistics and that practical work must destigmatize lack of food from a personal problem and view it as a structural issue caused by inequitable patriarchal and colonial systems. This paper also highlights experiences in collaborative research that led to action. Promoting critical feminist approaches can advance communities' ownership of research findings and co-developed solutions, while adding depth to academic work. Using critical feminist research approaches is, therefore, a range of qualitative methods aimed at generating unexpected findings and translating lived experience into scientific language. It suggests knowledge systems have to be decolonialized, socially inclusive, and provide a space for reflection on power and powerlessness and how this determines our understanding of food.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: https://edoc.hu-berlin.de/bitstream/handle/18452/23545/SLE285_Agency_in_South_Africas_food_systems.pdf?sequence=1.

Author Contributions

NP: study coordinator, introduction, methodology, and discussion. HS: theoretical framework. SN, NB, and KB-Z: perspectives on research findings. NB and SN: author of co-researcher perspective. NB and KB: coordination of field research and in-depth phase. KB-Z: co-author and commenter on the study and publication, and funder. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This study was funded by the Heinrich Boell Foundation Southern Africa and the Centre for Rural Development (SLE) through its post-graduate programme funded by the Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) and the Senate Department for Economics, Energy and Public Enterprises, Berlin.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the funders of this research, namely the Heinrich Boell Foundation and the Centre of Rural Development at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. We thank all people who provided their insights during the household survey. We wish to thank the five post-graduate students of the SLE who were at the heart of this work: Alexander Mewes, Johanna Hansmann, Lara Sander, Moritz Reigl, Vincent Reich—and a special thank you to Silke Stöber from the SLE who was the studies' backstopper and a passionate supporter of co-research. We wish to thank Jane Battersby for acting as an advisor on the SLE study. Thank you to Stefanie Lemke who invited us to this special issue and who supported the co-researchers with podcast training. A special thank you goes to all co-researchers who collaborated on the larger study. We wish to express our gratitude to Carmen Aspinall for editing this paper. Your language skills certainly improved this work.

Footnotes

1. ^Co-research is an inclusive and radical approach to participatory action research. For more details on this approach, please see Methodology and Research Design.

2. ^We interpret this to mean that jointly managed households are not headed by single parents and that having two potential income-producing adults in the household leads to a better financial situation for the household.

3. ^https://soundcloud.com/user-374323030/uphakantoni-first-episode.

4. ^The Heinrich Boell Foundation is the political foundation affiliated with Alliance 90/The Greens. Its work in the global south is primarily funded by the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ). one of the project's funding and advocacy partners.

5. ^A small, independently operated convenience store located on school property which sells prepackaged foods and snack items, primarily confectionaries.

References

Andrews, D. (2020). “Reflexion der sozialökologischen transformationsforschungin shrinking spaces—Mehr Raum für globale Zivilgesellschaft! “ in Dokumentation der 16. Entwicklungspolitischen Hochschulwochen an der Universität Salzburg, eds F. Gmainer-Pranzl and A. Rötzer, 11.

Andrews, D., Smith, K., and Alejandra Moreno, M. (2019). Enraged: women and nature. Right Food Nutri. Watch 11, 1–10.

Barad, K. M. (2007). Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Durham: Duke University Press.

Buthelezi, N., Karriem, R., Lemke, S., Paganini, N., Stöber, S., and Swanby, H. (2020). Invisible urban farmers and a next season of hunger—Participatory co-research during lockdown in Cape Town, South Africa. Cape Town: Critical Food Studies.

Chilisa, B. (2017). Decolonising transdisciplinary research approaches: an African perspective for enhancing knowledge integration in sustainability science. Sustain. Sci. 12, 813–827. doi: 10.1007/s11625-017-0461-1

Cock, J. (2016). A feminist response to the food crisis in contemporary South Africa. Agenda. 30, 121–132. doi: 10.1080/10130950.2016.1196983

Duncan, J., and Claeys, P. (2020). Gender, Covid-19 and Food Systems: Impacts, Community Responses and Feminist Policy Demands. Available online at: https://bit.ly/2Ya4vwj

Friedman, S., and McKaiser, E. (2009). Citizen Groups Need to Grow Deeper Roots Among the Poor. Available online at: https://za.boell.org/en/2009/11/10/civil-society-and-post-polokwane-south-african-state-assessing-civil-societys-prospects

Frison, E. A. (2016). “From uniformity to diversity. A paradigm shift from industrial agriculture to diversified agroecological systems,” in International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems. Available online at: http://www.ipes-food.org/_img/upload/files/UniformityToDiversity_FULL.pdf

Frost, S. (2011). “The implications of the new materialisms for feminist epistemology,” in Feminist Epistemology and Philosophy of Science: Power in Knowledge, ed H.E. Grasswick (Springer Science and Business Media BV).

Grosz, E. (2010). “Feminism, materialism, and freedom,” in NewMaterialisms: Ontology, Agency, and Politics. Duke University Press, eds D. Coole, and S. Frost, 11–24.

Hanisch, C. (1970). “The personal is political,” in Notes From the Second Year: Women's Liberation, eds S. Firestone and A. Koedt, 77–86. Available online at: http://carolhanisch.org/CHwritings/PIP.html

Haraway, D. (1988). Situated knowledges: the science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspective. Feminist Stud. 14, 575–599. doi: 10.2307/3178066

Hayes-Conray, A., and Hayes-Conray, J. (2008). Taking back taste: feminism, food and visceral politics. Gender Place Cult. 15, 461–473. 03 doi: 10.1080/09663690802300803

Hemmings, C. (2011). Why Stories Matter: The Political Grammar of Feminist Theory. New York, NY: Duke University Press.

Lewis, D. (2015). Gender, feminism and food studies. African Secur. Rev. 24, 414–429. doi: 10.1080/10246029.2015.1090115

Lewis, D. (2016). Bodies, matter and feminist freedoms: Revisiting the politics of food. Agenda 30, 6–16. doi: 10.1080/10130950.2017.1328807

Liboiron, M., Tironi, M., and Calvillo, N. (2018). Toxic politics: acting in a permanently polluted world. Soc. Stud. Sci. 48, 331–349. doi: 10.1177/0306312718783087

Maguire, P. (2001). “Uneven ground: Feminisms and action research,” in Handbook of Action Research, eds P. Reason and H. Bradbury (New York, NY: Sage), 590–599.

McClintock, A. (1995). Imperial Leather: Race, Gender, and Sexuality in the Colonial Contest. London: Routledge.

Merchant, C. (1989). Ecological revolutions: nature, gender, and science in New England. Bull. Sci. Technol. Soc. 10, 118–118.

Merchant, C. (2006). The scientific revolution and the death of nature. Isis. 97, 513–533. doi: 10.1086/508090

Ndlovu, M. (2014). Why indigenous knowledges in the 21st century? a decolonial turn. Yesterd. Tod. 11, 84–98. doi: 10.S2223/03862014000100006andlng=enandtlng=en

Nyaba, S., Buthelezi, N., and Lemke, S. (2021). Uphakantoni—First Episode. Available online at: https://soundcloud.com/user-374323030

Oxfam (2020). The hunger virus: How COVID-19 is fuelling hunger in a hungry world. [media brief]. Available online at: https://oxfamilibrary.openrepository.com/bitstream/handle/10546/621023/mb-the-hunger-virus-090720-en.pdf

Paganini, N., Adams, H., Bokolo, K., Buthelezi, N., Hansmann, J., Isaacs, W., et al. (2021). “Agency in South Africa's Food Systems. A food justice perspective of food security in the Cape Flats and St. Helena Bay during the COVID-19 pandemic,” in SLE Series, 285.

Paganini, N., Adinata, K., Buthelezi, N., Harris, D., Lemke, S., Luis, A., et al. (2020). Growing and eating food during the COVID-19 pandemic: farmers' perspectives on local food system resilience to shocks in Southern Africa and Indonesia. Sustainability 12:8556. doi: 10.3390/su12208556

Rosenow, D. (2019). Decolonising the decolonisers? Of ontological encounters in the GMO controversy and beyond. Glob. Soci. 33, 82–99. doi: 10.1080/13600826.2018.1558181

Rosiek, J., Pratt, S. L., and Snyder, J. (2019). The new materialisms and indigenous theories of non-human agency: making the case for respectful anti-colonial engagement. Qual. Inq. 26, 331–346. doi: 10.1177/1077800419830135

Shiva, V. (1994). Monocultures of the Mind: Understanding the Threats to Biological and Cultural Diversity. London: SAGE.

Shiva, V. (2005). Earth Democracy; Justice, Sustainability, and Peace, South End Press. London: Zed Books.

Swanby, H. (2021). Embracing humanity and reclaiming nature: neglected gendered discourses in the struggles of western cape farm workers. Gender Quest. 9:14. doi: 10.25159/2412-8457/7409

Tuck, E., and McKenzie, M. (2015). Place in Research: Theory, Methodology, and Methods. London: Routledge.

Van der Berg, S., Patel, L., and Bridgman, G. (2021). Food insecurity in South Africa. Evidence from NIDS-CRAM Wave 5. Available online at: https://cramsurvey.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/13.-Van-der-Berg-S.-Patel-L-and-Bridgeman-G.-2021-Food-insecurity-in-South-Africa—-Evidence-from-NIDS-CRAM-Wave-5.pdf

Vanderlinden, J. P., Baztan, J., Chouinard, O., Cordier, M., Da Cunha, C., Huctin, J. M., et al. (2020). Meaning in the face of changing climate risks: connecting agency, sensemaking and narratives of change through transdisciplinary research. Clim. Risk Manage. 29:100224. doi: 10.1016/j.crm.2020.100224

Vosloo, C. (2020). Extreme apartheid: the South African system of migrant labour and its hostels. Image Text. 34, 1–33. doi: 10.17159/2617-3255/2020/n34a1

Keywords: food security, transdisciplinary co-research, urban food systems, COVID-19 pandemic, critical feminist methodology, food dialogues, Cape Town

Citation: Paganini N, Ben-Zeev K, Bokolo K, Buthelezi N, Nyaba S and Swanby H (2021) Dialing up Critical Feminist Research as Lockdown Dialed us Down: How a Pandemic Sparked Community Food Dialogs in Cape Town, South Africa. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 5:750331. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2021.750331

Received: 30 July 2021; Accepted: 21 October 2021;

Published: 15 November 2021.

Edited by:

Jo Howard, Institute of Development Studies (IDS), United KingdomReviewed by:

Mutizwa Mukute, Rhodes University, South AfricaKatharine McKinnon, University of Canberra, Australia

Copyright © 2021 Paganini, Ben-Zeev, Bokolo, Buthelezi, Nyaba and Swanby. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nicole Paganini, bmljb2xlLnBhZ2FuaW5pQHRtZy10aGlua3RhbmsuY29t

Nicole Paganini

Nicole Paganini Keren Ben-Zeev3

Keren Ben-Zeev3