- 1Council on Energy, Environment and Water, New Delhi, India

- 2Scriptoria Ltd., London, United Kingdom

Introduction: The Indian food system faces a nexus of challenges in supply, demand and market linkages in the face of environmental and human development needs. The current agri-food system demands large-scale sustainable innovations, facilitated by an action-oriented approach by the rising number of actors in the agricultural space. These actors include public, private, non-profit and research institutions. They increase the scope for innovations to emerge and scale up through refocused investments and novel collaborations. Such successes in India, furthermore, can provide models of promising innovation pathways for many other countries in the Global South. Yet few case studies are available on successful innovations that have gone beyond the longstanding technology-led approach.

Methods (case study methods): This article presents two cases of other pathways. The first is an example of a differentiated new product category: the “pesticide-free” food product category and dedicated value chain established by Safe Harvest Private Limited. The second is an example of self-regulation through a certification standard: the Trustea code created within the Indian domestic tea industry.

Results: Both are driving sustainability at scale in Indian agri-food systems in two very different contexts, with the private sector leading the way.

Discussion: They offer insights on the roles of end users, trust, informal and formal links and actions, government endorsement, innovation bundling, and partnership.

Introduction

Since the Green Revolution hit India, productivity-raising agricultural innovations have transformed agri-food systems, and 92% of these have been technological solutions such as high-yielding crop varieties and chemical fertilizers. The focus of the Green Revolution was on increasing production and commodity specialization, supported by government policies. Currently, however, India is experiencing productivity stagnation; the technological approaches of the past face challenges in improving productivity further while also accounting for environmental and social needs (Singh, 2004). The small and marginal farmers who make up the largest share of country's agrarian economy are facing serious livelihood risks, exacerbated by rising income inequalities and a steep increase in their seasonal vulnerability due to the impacts of climate change. Input-intensive production that focuses on monocultures is not proving resilient to either socioeconomic or climatic shocks.

The opportunities for innovation in India's agri-food systems lie in the nexus of these challenges. Change is coming, and farmers need more support to move from high-input conventional cropping to innovative sustainable practices. The report Sustainable Agriculture in India 2021 (Gupta et al., 2021) shows that there is a dearth of transitional support to farmers as they shift from conventional practices to low-input sustainable practices—and farmers require such support to cope with the initial income loss risks and develop new capacities. There are limited incentives from the market such as price premiums, and implements are not widely available to reduce the labor costs of weeding and residue management. Farmers who already engage in sustainable practices do not have access and connections to appropriate markets. To make matters worse, the public incentive structure actively discourages the transition to sustainable agriculture. The government allocated half of the Ministry of Agriculture's INR 142,000 crore (USD 19.2 billion1) budget to subsidize chemical fertilizers in 2021, while allocating just 0.8% to the flagship National Mission for Sustainable Agriculture (Gupta et al., 2021). Furthermore, half a century of focus on irrigated regions has limited investment and innovation in the other 55% of India's net sown area.

All of the above has maintained the prevalence of practices—such as indiscriminate use of pesticides—that do not necessarily improve productivity, but have severe repercussions on profitability, the environment and human health (Bhardwaj and Sharma, 2013; Shetty et al., 2014; Sharma and Singhvi, 2017). The uptake of sustainable agri-food practices and systems remains low. Of the 16 sustainable practices and systems studied by Gupta et al. (2021), only six had been scaled up beyond 5% of the net sown area and/or 4% of the farmers in India. In descending scale these are crop rotation, agroforestry, rainwater harvesting, mulching, precision farming, and integrated pest management.

Nevertheless, a patchwork of interesting experiments and initiatives are appearing around India to enable the introduction and scaling of more sustainable innovations. An encouraging rise in the number of actors in the agricultural space—from among public, private, non-profit, and research institutions—is multiplying the possibilities to broker innovation networks (World Bank, 2012; Moschitz et al., 2015; Saravanan and Suchiradipta, 2017). There has always been strong potential for innovation in these systems, but its feasibility at scale is only emerging with the increasing number and diversity of actors. Repurposing investments can further build and expand the scope of this innovation—spurring transitions to more socio-ecologically resilient pathways.

Recognizing this, the Commission on Sustainable Agriculture Intensification (CoSAI) initiated a series of country studies with India, Brazil and Kenya, for documenting notable innovation pathways in sustainable agri-food systems (Chiodi Bachion et al., 2022; Khandelwal et al., 2022; Mati et al., 2022). The studies used a shared analytical framework to generate lessons on factors leading to successful innovation pathways, aiming to guide future investment. Successes in India can thus provide models of promising pathways for many other countries to follow in the Global South.

In the past there have been few case studies generated on successful innovations that have driven sustainability at scale in Indian agri-food systems. The available ones generally fall short of providing transferrable insights to innovation managers, investors, and other stakeholders around the world seeking to instigate large-scale innovation. Among others, models are lacking that fulfill the promises of product differentiation through new product categories, and of industry-led standards and certification in domestic markets of the Global South. This study presents two such cases that are driving sustainability in agri-food systems in two very different contexts, with the private sector leading the way. It focuses on the scaling up of non-pesticide management pursued by Safe Harvest Private Limited through its “pesticide-free” product category; and the Trustea standard and certification effort in Indian tea production.

Materials and methods

The innovation pathway studies undertaken across India (Khandelwal et al., 2022), Brazil (Chiodi Bachion et al., 2022), and Kenya (Mati et al., 2022) used a common investigative approach and analytical framework co-developed by CoSAI and the country partners. In India, we created a list of potential cases based on web searches, and complemented this with additional suggestions sourced from partner organizations of the Council on Energy, Environment and Water working on the topic of sustainable agri-food systems. We considered the following definition of innovation while identifying these cases:

• An innovation is an intervention or a bundle of interventions that have created a long-lasting, measurable, and transformative change.

• The change should be reflected as a positive impact on social, economic, and/or environmental dimensions.

• The intervention(s) may be in areas inclusive of, but not limited to, technology, finance, institutional structures, governance, policy, and business.

• Innovation is not necessarily a novel idea; it can also refer to an old idea that has been applied in a new way.

• A successful innovation is the one that has scaled up significantly in the given context.

The master list was screened for sufficient availability of data, scale achieved, evidence of transformational change, financial sustainability, and representation of a variety of farms and farmers in diverse agro-ecological zones. We selected three cases for analysis. While the first of these was the case of Andhra Pradesh Community Managed Natural Farming (detailed in Khandelwal et al., 2022), we devote this paper to the two private-sector-driven cases of Safe Harvest Private Limited and Trustea.

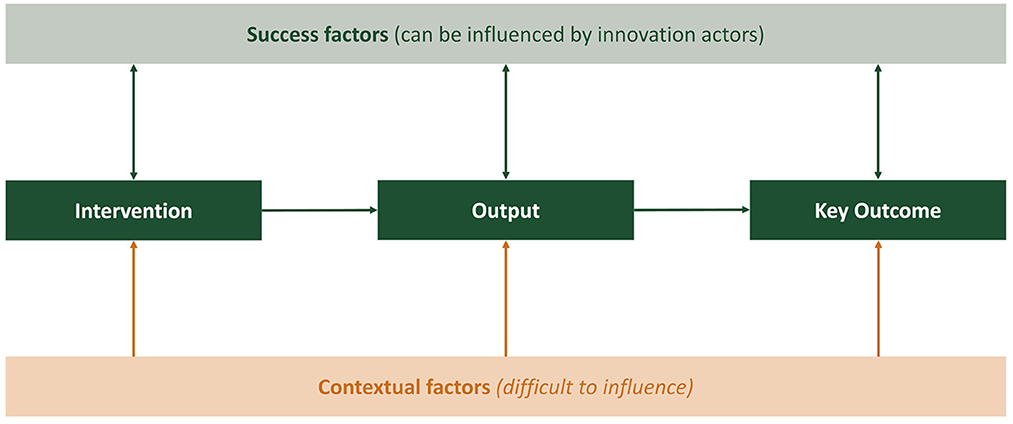

The objective of the case study process was to capture the key takeaways from each of the cases: practical, evidence-based lessons on factors that influence success in innovation pathways for sustainable agri-food systems. The analytical approach was based on developing and analyzing a theory of change (considering factors inside and outside the scope of influence of innovation actors, that affect the results of an intervention) for each case (Figure 1), based on relevant literature on the selected cases and detailed interviews with key informants. The literature consisted of documents available from the case websites as well as independent research papers where available. The primary informants were identified through this literature, and a snowball sampling method was used to identify others. We sought out independent case experts to triangulate research findings, and ensure presentation of unbiased analysis. Beyond the theory of change, each case was analyzed using a question shared across the three country studies: In your opinion, justified by evidence, what role did the following factors play in explaining the outcome at scale?

• The innovation processes.

• Innovation characteristics, including business/delivery/funding models.

• Relevance to demand, needs, and priorities of users, other stakeholders.

• Characteristics of the users or places, e.g., infrastructure, education.

• Context, e.g., policy enabling environment, public sector organizations and capacity, value chain or market system actors.

• Choice of scaling pathway and strategy.

• Specific scaling activities, e.g., evidence generation, advocacy/marketing, community engagement, pricing, risk mitigation, use of champions.

• Characteristics of organizations/actors leading or driving the innovation and scaling process.

• Characteristics of partnerships and the organizations/actors that served as partners in the innovation and scaling process.

Figure 1. A modified version of the results chain, which additionally shows how various factors, inside or outside the scope of the influence of innovation actors, affect the results of an intervention.

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, we conducted all interviews online or over the telephone, holding multiple interviews with individual stakeholders to compensate for the lack of physical interaction. Given the snowball sampling method we adopted to conduct the key informant interviews, interviewees were largely limited to contacts shared by the key stakeholders or drivers of Safe Harvest and Trustea. It was not in the scope of the study to interview end users, such as customers of Safe Harvest or its farmers.

Results

Safe Harvest

Safe Harvest Private Limited is a triple bottom line company based in Bengaluru that retails “pesticide-free” food, backed up by publicly available records of its product testing for chemical residues. Under the triple bottom line concept, it is committed to measuring its social and environmental impact on profit, people, and planet. It was the first business in India to retail products in the “pesticide-free” product category, where agricultural produce is grown under non-pesticide management. It also introduced a “zero certification” mark on its products signals the differentiation of its offerings.

Safe Harvest directly sources non-pesticide-managed produce including lentils, beans, whole-grain cereals and flours, millets, spices, herbs, sugar, and other sweeteners from farmer producer organizations (FPOs) situated across 12 states of India. FPOs are legal entities composed of primary producers who share in profits; it is an umbrella term for farmer producer companies, cooperatives, and societies. Partner FPOs connect Safe Harvest to more than 100,000 farmers. Most of these are small and marginal farmers, and close to 2,500 are tribal farmers (Safe Harvest interviews).

Safe Harvest understands non-pesticide management as something economically viable and practical for small and marginal farmers in India, as opposed to organic farming, where farmers would also need to give up chemical fertilizers. Most small and marginal farmers cultivate low-fertility soils and cannot give up chemical fertilizers without a yield dip in the transition period that comes with a complete phase-out of chemical inputs. On the other hand, it is chemical pesticides that have the most immediate and hazardous impacts on human health—especially on farmers, who have direct contact—and the ecosystem (Bhardwaj and Sharma, 2013; Sharma and Singhvi, 2017). Transitioning out of these was a more accessible path that would not necessarily demand compromising on yields and productivity. In fact, much of Safe Harvest's demographic of farmers were already farming with minimal or no chemical pesticides, as these inputs were not affordable, accessible, and available to them. Non-pesticide management was thus a highly viable and scalable option for these farmers, compared with totally organic farming practices.

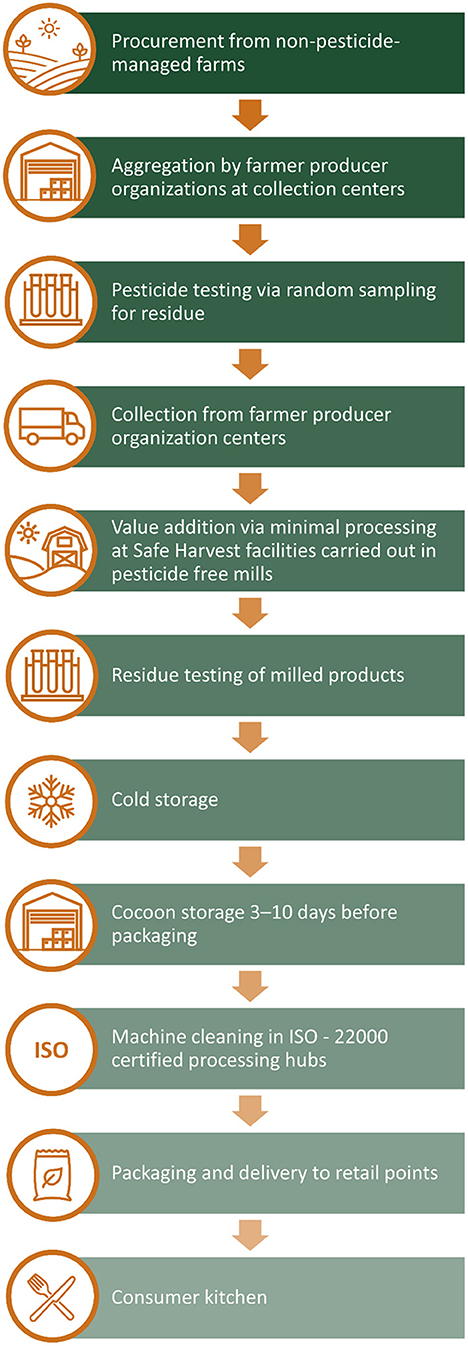

The partner FPOs promote and adhere to non-pesticide management practices among their members. Safe Harvest ensures the absence of chemical pesticide residues and adulterants via rigorous testing during the storing, cleaning, and value-addition processes of its consumer food products. The company works via a farm-to-kitchen model (Figure 2), making its products available at a price point that is only 10%−20% higher than conventional branded food products at large retailers across India—both brick-and-mortar stores and popular e-commerce platforms such as Flipkart and Big Basket (interview with leadership at Safe Harvest, October 2, 2021). This taps into that sub-segment of the middle-income consumer market where there is awareness of and demand for “pesticide-free” foods for health and safety.

History of Safe Harvest

Grassroots beginnings

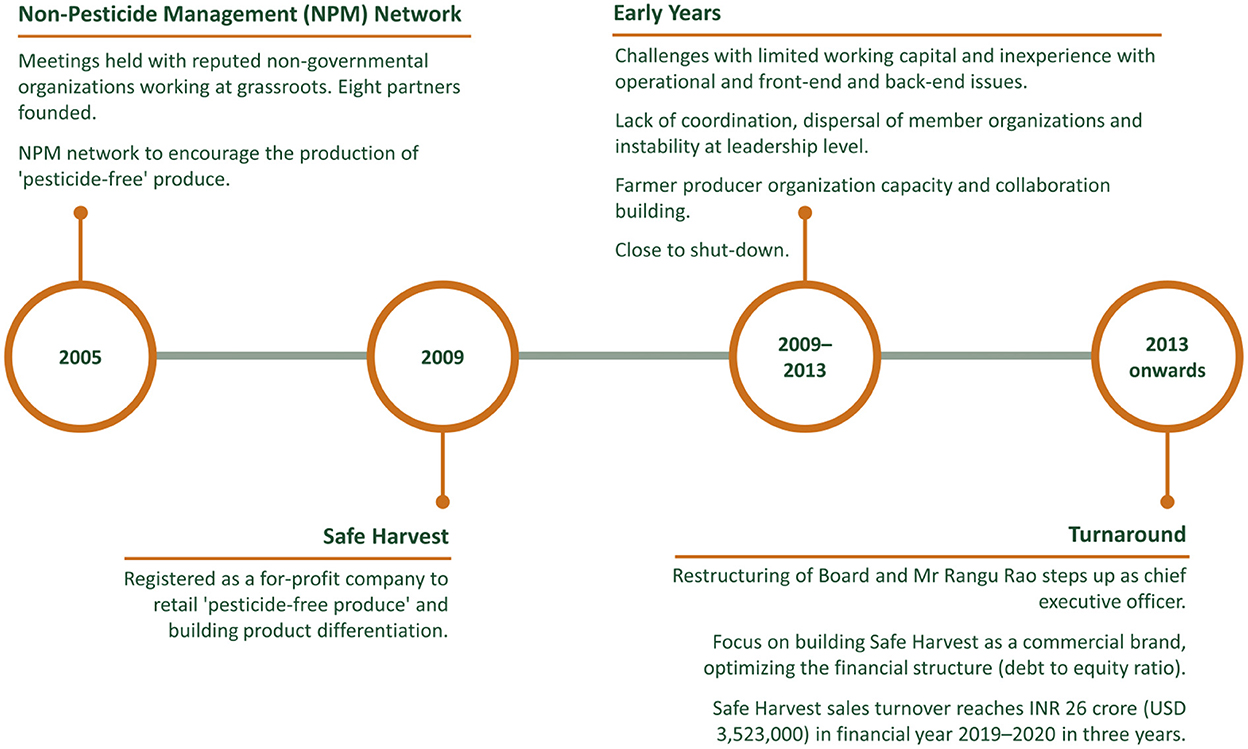

Experimentation with the Safe Harvest business model began in 2005, when eight NGOs who had been working with agricultural communities and environmental sustainability at the grassroots level founded the Non-Pesticide Management (NPM) Network with funding from the Ford Foundation. This initial grant was essential for the NPM Network members to pilot their ideas for the Safe Harvest model, deepen their understanding of non-pesticide management practices, build their collaborative capacities, develop the capacities of their partner FPOs, and align their long-term visions in the process. In 2009, Safe Harvest was registered as a for-profit company to address the goal of bridging market access for “pesticide-free” produce for small and marginal farmers.

As Safe Harvest emerged from grassroots work with agricultural communities, its services were rooted in the needs and the priorities of these communities. It built on the existing non-pesticide management practices of the farmers to build a new product category, a well-controlled supply chain, and a market for their products. The “pesticide-free” category solved issues associated with organic cultivation on both ends: the costs of transition and certification for farmers; and the affordability of products to price-sensitive middle-income consumers, who were excluded from the higher pricing of the organic market.

Working with farmer producer organizations

Safe Harvest also built on the rising level of farmer collectivization in India. However, farmer collectivization is still evolving in the country and the necessary ecosystem to adequately support FPOs is in development. FPOs require special support in their early years, with NABARD (2020) reporting that the “majority of these FPOs are in the nascent stage of their operations with shareholder membership ranging from 100 to over 1,000 farmers and [they] require not only technical hand-holding support but also adequate capital and infrastructure facilities, including market linkages for sustaining their business operations.” Still, Safe Harvest decided to establish business relationships at the FPO level instead of procuring produce from individual farmers. The company understood the limits faced by small and marginal farmers and the need for collective efforts, particularly considering issues around pesticide cross-contamination from neighboring fields. Additionally, each farmer's limited marketable surplus alone would be very difficult to bring into the organized bulk and retail markets.

At the same time, the relationships with FPOs were more than purely transactional. Safe Harvest had a long-term perspective on nurturing trust. This ensured sustainability in the relationships, encouraged buy-in by farmers and FPOs, helped them endure through times of conflict, and enabled Safe Harvest to support FPO development through the NPM Network. FPOs were not contractually barred from selling to other buyers, and when Safe Harvest had to pause a relationship because the output did not pass residue testing, they could still return to the FBO the following year. Because the company grew out of NGO roots, it was guided by an effort to build a pan-Indian non-pesticide management movement committed to food safety and farmer access. It ensured training of FPOs on market preparedness, value addition, aggregation, and storage, building up its supply chain partners—while also explicitly building up the bargaining power of small, marginal and tribal farmers.

Value chain and consumer base development

When Safe Harvest first came into the market, there was no pre-existing supply chain specifically designed for retailing “pesticide-free” products, so there were myriad risks of cross-contamination. Furthermore, there was limited consumer awareness—not only of its brand and products, but more generally of non-pesticide management, and of the importance of testing and evidencing claims on food products. Safe Harvest had limited working capital, it lacked experience engaging with the market, and almost all of its FPO partners were accessing organized markets for the first time (Anil, 2019). In a highly competitive market, maintaining relatively affordable pricing and ensuring product availability were steep challenges. In 2012 and 2013, Safe Harvest was close to shutting down (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Safe Harvest's flow of a farm-to-kitchen model. Authors' creation based on Safe Harvest website, inputs from interviews and Anil (2019).

However, post-2013, it experienced a turnaround. The company internally restructured its board and Rangu Rao, a founding member of the non-pesticide management movement and Safe Harvest, stepped up as the CEO. The focus shifted to building Safe Harvest as a commercial brand, optimizing the financial structure in its debt-to-equity ratio, and ensuring market differentiation for “pesticide-free” products, including generating evidence to support the claim for differentiation. Safe Harvest transitioned from its NGO approach to operating as a commercial social enterprise, while retaining its mission-driven approach—which was key in defining how it built relationships, what processes it engaged with, how it formulated solutions, and where it looked for funding partners.

Commercial success

In 2016, it received institutional funding in both debt and equity. Safe Harvest has since garnered traction among consumers for its products, with sales turnover reaching INR 26 crore (USD 3.5 million) in financial year 2019–20 (Safe Harvest interviews). It built its early customer base in South India, where it observed a strong initial awareness around food safety. It was then able to build its presence as this awareness spread across the country—especially in light of the COVID-19 pandemic and increased consumer concern for health and food safety. In 2019–20 its sales territories were limited to Chennai, Bengaluru, Hyderabad, Visakhapatnam, and Vijayawada, but this has since expanded to include the National Capital Region, Mumbai, and Pune.

Rather than investing in advertising through newspapers, billboards, or television (which the company lacked the funds to pursue), Safe Harvest used its on-shelf product availability, selection, and “zero certification” mark to register its presence in multiple product categories. According to its financial reports, 15%−20% of its revenue is invested in marketing and distribution. Its communication and sales teams also work closely on social media and direct consumer outreach (Anil, 2019). Consumers are offered discounts through brick-and-mortar retail chains and e-commerce platforms, and the visibility of Safe Harvest on these platforms is rising. As of 2021, Safe Harvest was working on making the “zero certification” on its packaging traceable.

Safe Harvest's innovation

Launching a new product category

The core innovation at Safe Harvest was the creation of a new product category, “pesticide-free” food, and a specialized supply chain for it. Before this, the existing product categories were organic and conventional foods. Organic foods can be extremely price exclusive in India and may have gaps between their claims and evidence of safety. Conventional foods are prone to environmentally unfriendly means of production and may be laden with chemical pesticides that are hazardous to both producers and consumers. Safe Harvest actively built a third category of products, “pesticide-free” foods, driven by its mission of providing safe and healthy food for all while supporting smallholder farmers.

Maintaining compliance

It keeps the promise of “pesticide-free” foods from farm to kitchen by providing end-to-end solutions to its supplier FPOs (which are also value chain partners) and having Safe Harvest staff present at facilities from harvesting through to final procurement. Its network approach enables training, grading, and ensuring FPOs and farmers can comply with standards. Safe Harvest procures multiple commodities from different FPOs across India to ensure steady supply despite environmental and other fluctuations, maintaining a diverse offering of products. It also oversees rigorous compliance across its partners and adherence to the maximum pesticide residue limits set by the Food Safety and Standards Authority of India's Jaivik Bharat (Organic India) standards. It then publicly shares the results of its product test reports to back up the “zero certification” label, reinforcing its product differentiation. Pricing the products at only 10%−20% higher than conventional products unlocks the price-sensitive but enormous middle-income consumer segment for these products (Safe Harvest interviews).

Raising finances

One of Safe Harvest's key sub-innovations was its capacity to effectively plan and raise finances. Since it was introducing a whole new category of food products, there was a longer timeline envisioned to establish the concept, build the market supply chain, bring economic returns, and see a greater benefit to the public, especially as it worked with small and marginal farmers who were often more remote. Even without the existence of a supportive financial ecosystem for such an enterprise, Safe Harvest innovated on its capacity to tap into varied sources of finance to suit its needs throughout this journey. The initial grant from the Ford Foundation helped establish the category by catalyzing the NPM Network's efforts to help farmers commit to “pesticide-free” practices. It also allowed the Network to collectivize and align on its priorities, which was key in defining financial goals, among others.

After its 2013 restructuring, Safe Harvest raised four rounds of equity and was able to attract key impact investors like Ashish Kacholia, who continues to support the company in improving its financial credibility and raising debt with his investment expertise. The increased confidence from investors led to unique tripartite agreements with credit institutions and increased Safe Harvest's and its partner FPOs' operational capacity, as the FPOs' creditworthiness also improved. One key agreement was with Friends of Women's World Banking–India and Ananya Finance as a direct lender; here, Safe Harvest took the cost of financing and FPOs transferred custody of aggregate commodities to Safe Harvest. The novelty here lay in Safe Harvest's willingness to repay loans on behalf of the FPOs. Taking on the interest liability of separate organizations, especially young FPOs without credit history, is an uncommon practice, and shows the long-term perspective of Safe Harvest. Having underwritten many such agreements, Safe Harvest has been successful in acquiring debt to support its operations and growth.

Encouraging buy-in

Some FPOs even invested in Safe Harvest in 2014 and 2015 to increase the scope of how the farmers and company work together; in 2022, FPOs held 0.5% of shares. Moving from stakeholders to shareholders also provides evidence of the FPOs' commitment to non-pesticide management and direct market linkage. Together, the innovations in funding enabled Safe Harvest to increase its volume and reach and establish the “pesticide-free” category. By actively building this context for itself, Safe Harvest has also built the context for other market players to enter and retail under the “pesticide-free” category of food.

Outcomes and impacts

Through Safe Harvest's network, FPOs have gained skills in market preparedness, value addition, aggregation, and storage. Some have climbed up the value chain, allowing them to earn a greater share of the consumer rupee: 15 FPOs now supply clean and graded agricultural commodities to Safe Harvest; one of these also packages more than a dozen products for the retail market; and five others are able to supply Safe Harvest with retail-quality products that don't require further processing or manual cleaning. These FPOs have also been able to increase their collective negotiation capacity and power with different potential buyers.

Social impacts

The social impacts begin with health. Studies evidence the ill effects of chemical pesticides on human health, and reducing exposure to these pesticides also reduces the scope of hazardous exposure (Bhardwaj and Sharma, 2013; Grewal et al., 2017; Sharma and Singhvi, 2017). Transitioning to non-pesticide management reduces hazardous exposure and improves the health of farmers, their families, and their communities. Consumers of “pesticide-free” products, too, avoid pesticide residues in their food. Safe Harvest has always advocated for compulsory residue testing and greater transparency to the consumer in general, and set the benchmark by being the first to have its testing information available publicly. The Food Safety and Standards Authority now mandates testing for pesticide residue for all agricultural commodities.

Economic impacts

In terms of economic impact, Safe Harvest has enabled access to a stable, profitable, transparent and organized market for 100,000 small, marginal, and tribal farmers across 12 states of India. Transacting directly with FPOs, it offers farmgate prices that are comparable to those of the Agricultural Produce Market Committees run by state governments. By collecting at the farm gate, Safe Harvest saves farmers the fees, commissions, and transport costs associated with the Market Committees, which can be considerable for farmers located in remote areas (Anil, 2019). Safe Harvest also reported a drastic reduction in farmers' input costs from INR 2,500 (USD 33.8) to INR 100 (USD 1.35) per hectare because of non-pesticide management practices (Safe Harvest, n.d.). The amalgamation of reduced cost of inputs and increased savings led to most farmers reporting a 20% or more increase in income (Anil, 2019). On the consumer end it has brought accessibly priced products to a greater group of consumers who are conscious of health and environmental issues but cannot afford organic food.

FPO development also has socioeconomic benefits. Due to assured market access and available working capital, FPOs can invest and upgrade their capital assets (Anil, 2019). They are able to build capacity to vertically integrate value-addition activities like aggregation, stockage, cleaning, and grading, diversifying their income and capturing more of the consumer rupee. Furthermore, FPOs are able to access finance via tripartite agreements with Safe Harvest and formal lenders, improving their creditworthiness and allowing them to deal with larger volumes. Safe Harvest also helps young FPOs with no credit history access credit from institutions like NABKISAN (a subsidiary of the National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development) and Friends of Women's World Banking–India. With such formal financial access enabled, the government's infusion of up to INR 10 lakh (USD 13,345) more under the matching equity program has helped FPOs raise equity and proportionately higher debt. Eleven FPOs have received loan linkage facilities via Safe Harvest from non-banking financial companies like NABKISAN, Ananya, Avanti, and Friends of Women's World Banking–India on different occasions, varying from INR three lakh (USD 3,998) to INR three crore (USD 400,384).

Environmental impacts

Finally, Safe Harvest's new product category has had multiple positive environmental impacts. Non-pesticide management training to farmers has reduced the entry of hazardous compounds into the environment and food chain, mitigating well-documented ill effects of pesticides on ecosystems (Bhardwaj and Sharma, 2013; Grewal et al., 2017; Sharma and Singhvi, 2017). The management approach is also water smart: by focusing on limiting chemical fertilizers and progressively increasing organic manure and biofertilizers, in situ moisture is maintained and the need for irrigation is reduced. FPO partners are mindful of the depth of irrigation for crops such as monsoon-season rice, which increases the efficiency of water cycling through the system and reduces risks of water quality deterioration (Safe Harvest interviews). Soil-enhancing practices are further combined with crop rotation, mixed cropping, and intercropping to generate positive impacts on soil health. Biodiversity is enhanced as the adoption of non-pesticide management reduces the harm from chemical pesticides and fertilizers.

While an immediate transition from input-intensive farming to chemical-free farming is very risky and difficult for small and marginal farmers, the adoption of non-pesticide management has created an essential stepping stone toward it. Many farmers have upgraded to further environmentally positive practices beyond non-pesticide management over the years, including the full transition to organic and other chemical-free farming models (interviews with leadership of Nature Positive Farming, Wholesome Foods Foundation and Samuha, August 17, 2021).

Success factors

A foundation in experience

The founding members and leaders in Safe Harvest came from well-established NGOs with years of field experience in development. They were able to leverage their experience, knowledge, and networks to build solutions grounded in a nuanced understanding of immediate context and farmer needs. Just as importantly, Safe Harvest as an organization has been well aligned to its principal value of making safe and healthy food available to all by supporting small and marginal farmers. The company ensured internal alignment to this value and the need for long-term thinking and trust-building. This allowed it to persist and invest in building itself, its supply chains, and its partnerships through all the ups and downs that have led to its current growth phase. Because the vision aligns closely with that of the NPM Network from which Safe Harvest emerged, the network has offered key support in training and developing the capacity of Safe Harvest's FPOs.

Evidence and presence

The characteristics of the “pesticide-free” product category as an innovation are also key to its success. Notably, the innovation is based on a foundation of sharing evidence to build trust of the consumers in Safe Harvest's “zero certification” label. This includes making the results of product verification tests publicly available, ensuring all claims are verified and reliable. Meanwhile, procurement from multiple states across the country not only supports the year-long on-shelf presence of Safe Harvest's products, building resilience against environmental and supply variability, but also broadens its product selection. These factors significantly increase the potential touch points with any prospective consumer, giving Safe Harvest a notable market presence while keeping the organization lean. The number of commodities that Safe Harvest deals in increased from 40 in 2018–19 to 55 in 2021–22.

Farmer ownership

As Safe Harvest brings in FPOs as partners, it enables the FPOs' sense of ownership. Such partnerships have allowed the company to bridge expertise gaps and strengthen its operational capacity. As it showed its commitment to working with FPOs and supporting them through the process of training and procurements, Safe Harvest was able to build good faith, with some FPOs even displaying their ownership by becoming shareholders. This made the process of developing supply partners for a new market context easier, and attracted other FPOs to seek out Safe Harvest. The number of partners that Safe Harvest transacts with increased from 22 in 2018–19 to 30 as of August 2021. By the latter date, Safe Harvest was working with 10 more organizations that were in the process of forming farmer collectives.

Investor trust

Safe Harvest also leveraged its financial and development-world networks and built relationships with institutions and individuals where they could mutually support Safe Harvest's financial needs and the partners' goals. Here, too, building trust was key. The partners included individual investors, institutional investors, formal institutional lenders, non-banking financial companies, and even FPOs that hold shares. The diversified pool of funds, including grants, debt, and equity from different funding partners, was put to judicious use by capitalizing on different funding mechanisms from different partners. Safe Harvest's investors have focused on particularly long time horizons and bought into Safe Harvest's capacity for social impact and its vision, which kept their buy-in through challenges. India's largest impact investor, Ashish Kacholia, was a determined investor with the resources to take on a high-risk venture with a long time horizon, and he also helped Safe Harvest strategize through its restructuring. Another investor, Friends of Women's World Banking–India, was able to provide financing even when Safe Harvest was a new entity that was incurring losses, didn't have an established supply chain, and was working with “higher-risk” farmers, because of the trust and vision Safe Harvest has built and evidenced in its institutional design and collaborative capacity.

Future challenges

Building a category, getting shelf space, selling the products, and reaching profits is a long journey that requires capital insertion and sustained support. Financiers are needed at different points of an enterprises' journey to support the unique needs in each stage, including both equity and debt. As debt financing isn't easily accessible from formal financial institutions, Safe Harvest has to rely on non-banking financing companies, which can be expensive. Along with equity investors who are aligned on values and are open to investing in a longer time horizon, support from formal banks to provide working capital at early stages over a longer period would enable the organization to grow and bring results faster. On the other hand, Safe Harvest has been prioritizing financial sustainability over fast results and the company seems content to scale up at its own speed.

Finding and matching investors who can align with the vision—where farmers are the final stakeholder and are willing to take on long-term investments—is essential, and remains a challenge for such enterprises. The vision requires eventual hand-off of greater shares of ownership over the value chain to FPOs and farmers, so that in the event of an investor wanting to exit and sell, the institutional design and the vision will stay intact. Safe Harvest has been actively engaging with its FPOs to ensure their ownership of the value chain, toward the goal of a complete hand-off where Safe Harvest only remains as their marketing and branding partner. This is central for other organizations within the social innovation and development sector, as well, to ensure impact beyond their tenure while also supporting systems resilience.

Trustea

Tea is a top consumer beverage in India, and the country comes second only to China in tea production (Jaisimha, 2019). While historically tea was primarily cultivated for export purposes, currently about 80% of India's tea production is for domestic consumption. This has changed the landscape of tea cultivation; while tea estates primarily cater to the global market, the supply to the domestic market comes from smallholders (Langford, 2019). Small tea growers (STGs, defined as having up to 25 acres or 10.12 hectares of tea cultivation) now contribute about 50% of India's tea production (Consultivo, 2020). While estates process their tea on-site, smallholders transport their tea to factories—either the estate factories or bought leaf factories that source at least two-thirds of their tea from outside growers. The factories then process the tea and sell it through auction centers or directly (Langford, 2019).

Historically, STGs and bought leaf factories often lacked knowledge on sustainable practices and the resources to adopt them, and the working conditions in both were often poor (Asia Monitor Resource Centre, 2010). Because the global market sourced its tea chiefly from large estates, the Indian estates that exported tea were governed by global private standards such as Rainforest Alliance and Fairtrade, which ensured that producers met certain product and process standards (Langford, 2019). Standards only governed this small fraction of India's tea producers, however. STGs were disconnected from global standards, and concerns arose regarding the well-being of their workers, the quality of their tea, and the sustainability of their production (Langford, 2019).

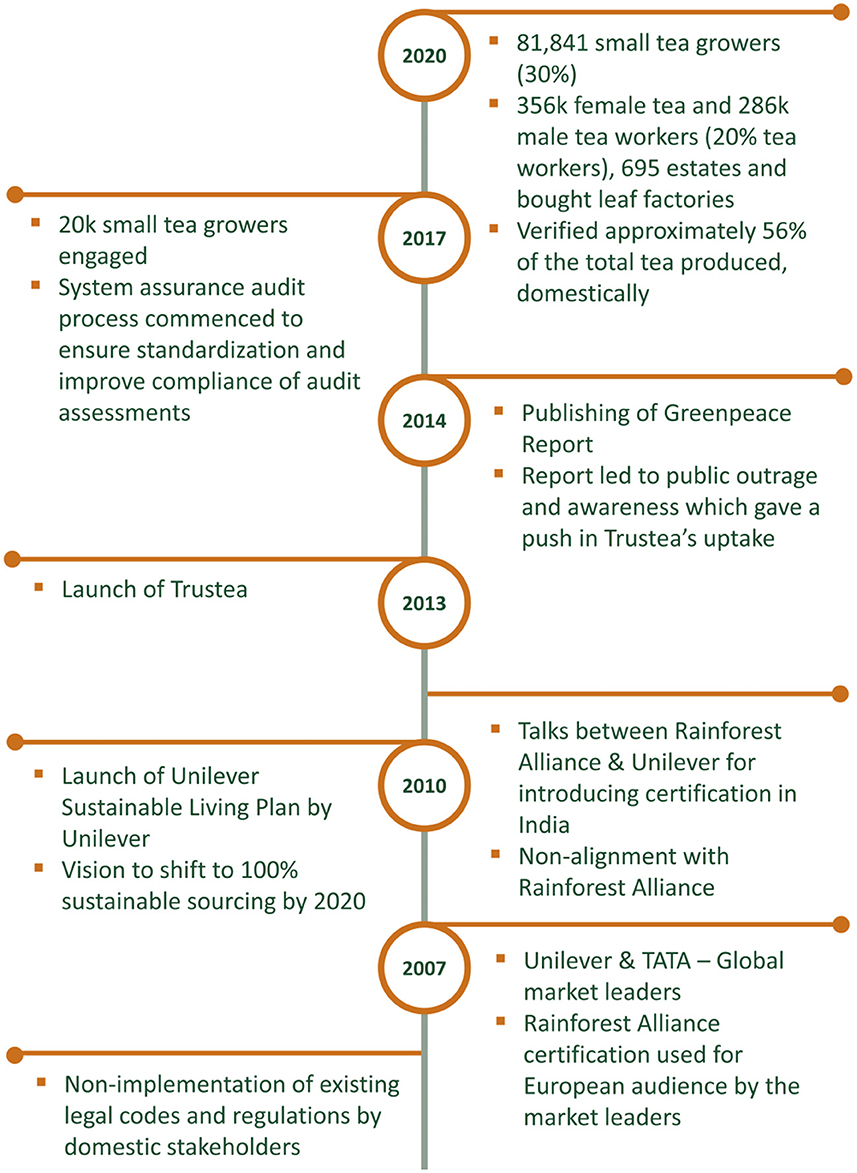

History of trustea

The push for self-regulation

A confluence of actors in the global and domestic markets has facilitated the push for self-regulation among STGs in producer countries (Langford, 2019). While Unilever and Tetley (owned by Tata Consumer Products) control 16% of the global tea market (Potts et al., 2010), about 45% of India's domestic market is controlled by Hindustan Unilever Limited, a subsidiary of Unilever, and Tata (Singh et al., 2021). As early as 2007, Unilever took the lead in adopting Rainforest Alliance certification for all their tea sold in the European Union, and in 2010 they announced a vision to shift to 100% sustainable sourcing by 2020 (Unilever, 2010; interview with Mr. Daleram Gulia, Procurement Manager for Sustainability at Hindustan Unilever, August 24, 2021). To achieve this, Unilever attempted to introduce Rainforest Alliance certification across all their tea sourcing regions. This proved difficult in India, as there existed differences between Rainforest Alliance's code of conduct and Indian labor laws (Langford, 2019). For example, the minimum permitted age for a tea worker under the Rainforest Alliance code was higher than the age allowed under Indian labor laws.

In the face of differences in product and process standards between global and domestic markets, as well as other challenges from the fragmented smallholder tea industry in India and the organization's lack of outreach to STGs, Rainforest Alliance was not successful in bringing self-regulation to STGs as per its global standards (Langford, 2019). While creating an India-specific Rainforest Alliance standard that aligns with Indian labor laws could have been easier, Rainforest Alliance did not wish to create regional variation in its certification. These factors led to the recognition of the need for a domestic standard that was specific to the Indian domestic market. Based on this context, Hindustan Unilever envisaged the establishment of a multi-stakeholder program based on industry realities and globally accepted sustainability principles. Unilever's existing Sustainable Agriculture Code—a collection of Good Practices which aim to codify important aspects of sustainability in farming and apply them to supply chains—would provide the standard with a robust and credible framework (interview with Sustainability leadership at Hindustan Unilever, August 24, 2021).

Around the same time, Indian consumers were gaining awareness of the need for safer tea. A report by Greenpeace (2014) found “highly hazardous” and “moderately hazardous” pesticides in tea samples, including those collected from major brands such as Hindustan Unilever, Tata, and Wagh Bakri, outraging tea drinkers. To counter this, the Tea Board of India—a quasi-autonomous government body that authorizes, registers, and licenses industrial activities within the tea industry—came out with a Plant Protection Code for the use of pesticides on tea. However, the Tea Board of India didn't have the wherewithal to enforce the code, and Indian NGOs felt that this move was insufficient to address the spectrum of challenges faced by smallholder producers, such as deplorable working conditions (Langford, 2019).

A tea standard for India

Interests and influences driving self-regulation in the Indian tea industry were not limited to Hindustan Unilever alone. The Dutch organization IDH–The Sustainable Trade Initiative was also working for sustainability in the tea industry through their Tea Improvement Program. Upon seeing IDH's interest in funding standards for self-regulation within domestic markets, Hindustan Unilever approached IDH about the Indian tea industry (Langford, 2019). Later, IDH reached out to Tata Consumer Products, making Trustea an industry-wide initiative. Tata also brought in a collaboration with the Ethical Tea Partnership, which played an important role as one of the implementation partners in Assam, West Bengal, and Kerala (interview with Sustainability leadership at Tata, August 18 and 23, 2021).

To design a standard for tea production in India, Unilever approached Solidaridad Asia, an NGO based in New Delhi. Its parent NGO, Solidaridad, had previously played a key role in designing, developing, and mainstreaming standards within the markets of global firms for many commodities. The organization also provided training to improve producers' uptake of certifications. Solidaridad Asia collaborated with Hindustan Unilever, and together they developed the initial draft for a standard of self-regulation for Indian tea producers that accounted for the intricacies of the domestic tea market (Langford, 2019).

Building on this foundation, Hindustan Unilever, Tata, and IDH came together to launch Trustea in 2013—an Indian verification system and sustainability code for the tea sector. After the launch, these three partners plus the Ethical Tea Partnership and Solidaridad co-created the final form of the code. Sector-level multi-stakeholder engagement, decision making, and action via Trustea ensured that the further evolution of the Trustea code and its mainstreaming would happen in a planned and strategic manner. With early support from a state regulatory body, the Tea Board of India, Trustea further ensured that it would not face any administrative hurdles with the government.

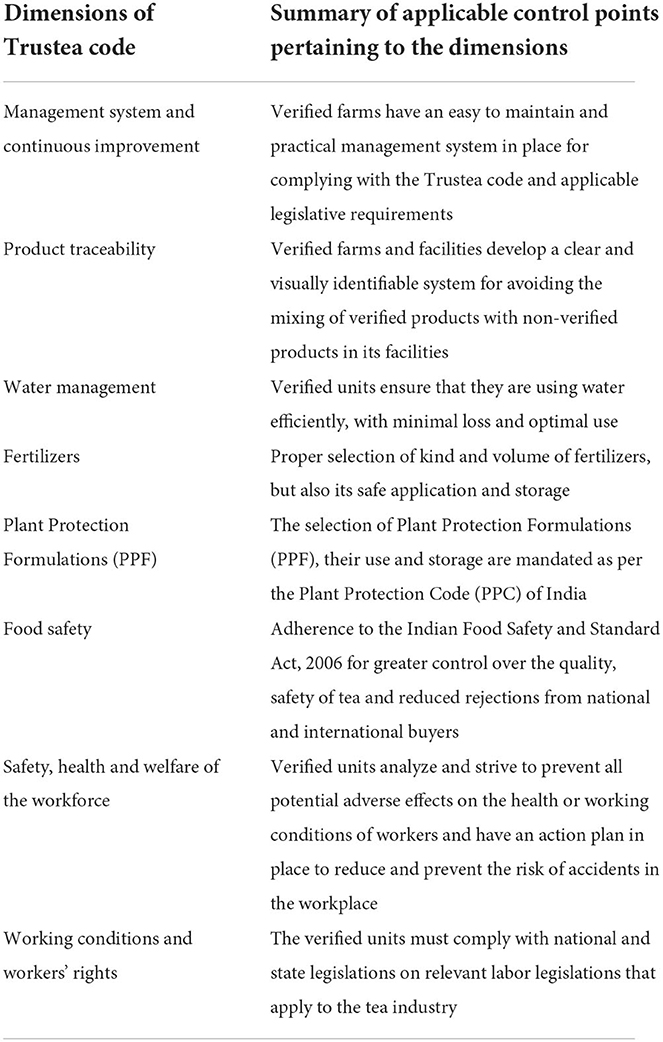

Industry engagement

The Trustea code works toward overcoming the multiple challenges of the tea industry (Table 1). It enables producers, buyers and others involved in the Indian tea business to obtain tea produced according to “agreed, credible, transparent and measurable criteria” (Trustea, 2021). Many STGs were initially unable to adopt the practices of the sustainability code, whereas large tea estates had the resources and infrastructure to adopt the certification, but had to be aligned to the business case and understand the benefits. Trustea, therefore, engaged with factories in estates, bought leaf factories, and representatives of grower groups for compliance and certification under the code; these, in turn, worked with STGs. Trustea certified bought leaf factories, and the chain of custody established here let Trustea train STGs and build their capacity through factories. This chain of custody also aided factories in keeping track of the quality of tea (Trustea, 2021). The stakeholders who engage with Trustea continue to take note of changes happening in the market, consumer demand, and environment, in order to upgrade or modify the Trustea code accordingly.

Trustea began operation with funds provided by IDH, Hindustan Unilever, and Tata, later strengthened by the joining of Wagh Bakri Group in 2017. Hindustan Unilever and Tata have contributed equally to the Trustea code, to the tune of INR two crore (USD 265,362) every year. IDH contributed INR three crore (USD 398,044) a year until 2020, and Wagh Bakri has contributed INR 50 lakh (USD 66,350) a year since joining (interview with Sustainability leadership at Tata, October 18, 2021). Currently, Trustea is transitioning toward a new business model where it will monetize the Trustea seal on retail packs. Trustea will continue to provide free-of-cost training and capacity-building activities to all stakeholders, and the cost will only be borne by companies who put Trustea seals on their packaging. Until such a time as it reaches a break-even point, Trustea will continue to receive financial support from its funders.

Out of an estimated 250,000 STGs and 3.5 million tea workers in India (Rajbangshi and Nambiar, 2020), Trustea had by 2020 engaged with 81,841 tea growers and 640,000 workers (Figure 4). The STGs with whom Trustea has engaged are an average of 57 years old; most have completed a primary level of education; and 90% own an estate smaller than five hectares (Trustea, 2021). Trustea has certified 695 estates and bought leaf factories, covering 56% of all tea produced in India (Trustea, 2020a).

Trustea's innovation

Establishing private self-regulation

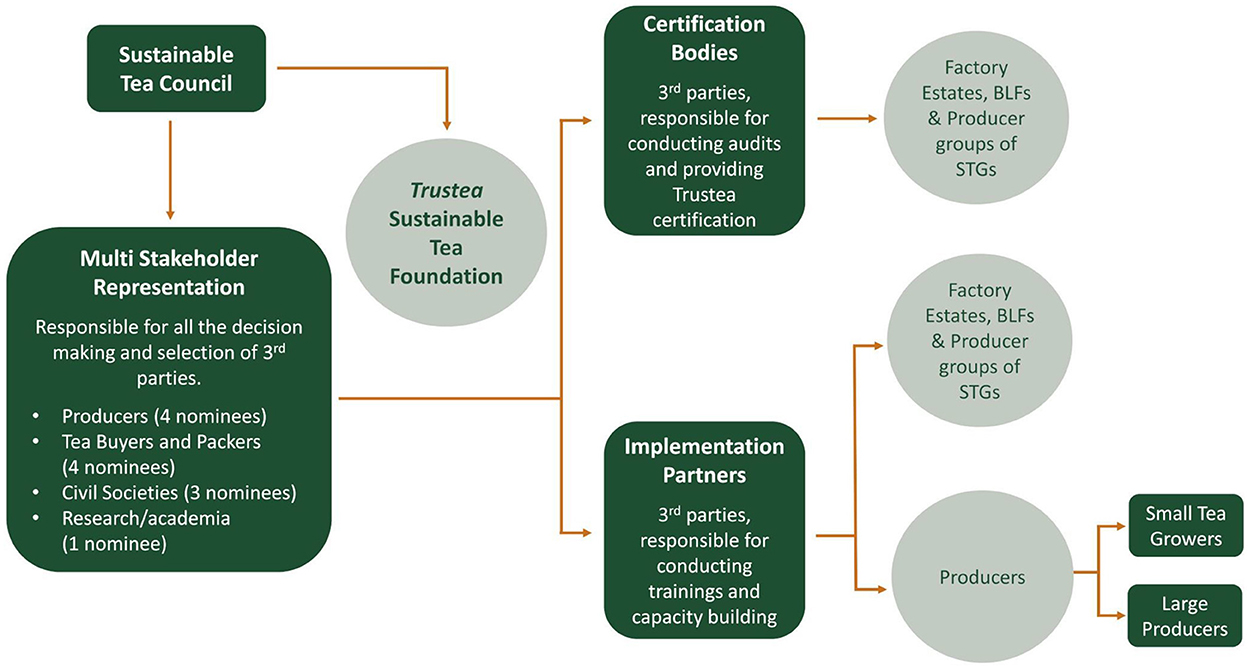

Trustea's core innovation is its process of self-regulation (as defined in Gupta and Lad, 1983). Its code is governed and facilitated by a diverse and inclusive multi-stakeholder council with buy-ins from tea brands, tea producers (large tea estates, STGs, bought leaf factories), NGOs, civil society, research and academia (Figure 5). The council is divided into a funding committee (IDH, Tata, Hindustan Unilever and Wagh Bakri) and a program committee (IDH, Tata, Hindustan Unilever, United Planters' Association of Southern India, Indian Tea Association, Confederation of Indian Small Tea Growers' Associations, Assam Bought Leaf Tea Manufacturers' Association, Tea Research Association, Gujarat Tea Processors and Packers Limited, and UN Women). The council is collectively responsible for taking all the decisions of Trustea in a consensual and aligned manner. The decision to have representation from various categories of stakeholders in the domestic tea industry is a strategic one to ensure impact and buy-in throughout the industry.

Figure 5. Representation of Trustea stakeholders, including bought leaf factories (BLFs) small tea growers (STGs). Authors' creation based on Trustea (2020b).

Building small tea grower capacity

Trustea does not stop at verification, like some other certification efforts, but also invests in building the capacity of STGs, bought leaf factories, tea workers, and other producers to ensure compliance. A unique aspect of this procedure is that Trustea engages with STGs through estate factories and bought leaf factories. These factories share lists of STGs who provide them with their tea, and Trustea undertakes training of these STGs as per the requirements of the code. By establishing this chain of custody and putting the onus on these factories, Trustea has attempted to address the problem of chasing every STG to ensure their compliance and adherence to the code. This process also aids the factories and Trustea in maintaining traceability and quality of the produce.

Trustea's capacity-building processes are tailored for easy comprehension by STGs and tea workers and employ community engagement, community building, and experiential learning. Based on observations that STGs learn well through live demonstrations, Trustea devised a concept of model farms wherein tea growers learn to practice sustainable methods on farm, discuss their challenges, and seek resolution by trained personnel and fellow growers. One of the most recent efforts, Tracetea, is a digital platform and traceability application where STGs can register, conduct business, discuss their problems, suggest solutions, and interact with other STGs across the nation. Tracetea has been successfully piloted in West Bengal, Assam, and South India (Trustea, 2021).

Implementing with a local presence

For implementation, Trustea linked up with multiple entities such as the Tea Research Association, Action for Food Production, Reviving the Green Revolution (an associate of Tata Trusts), Ambuja Cement Foundation, and the National Skills Foundation of India. These implementation partners were selected after evaluation of their alignment with Trustea and their local presence, and they play an instrumental role in providing training and hand-holding support to stakeholders. The implementation partners employ local personnel and execute capacity-building activities so that there are few trust, language, or community/region-specific barriers. Audits on the stakeholders are conducted via third-party vendors.

Outcomes and impacts

Environmental impacts

As an initiative rooted in sustainability goals, the Trustea code has had multiple positive environmental impacts. Tea being a water-intensive crop, Trustea encourages the adoption of practices that improve water use efficiency and sewage management by mandating these in the code. They have introduced extensive training and guidance on water management practices for verified units, but have not been able to verify compliance, especially by STGs (interview with leadership at Trustea, October 11, 2021). More than 50% of STGs associated with Trustea have, at least, introduced control mechanisms for chemical runoff and sewage (Consultivo, 2020). To enhance the soil quality of tea estates, Trustea also mandates adherence to the Plant Protection Code and the use of Food Safety and Standards Authority-approved chemicals within allowed limits. Through the training and capacity building of STGs, adherence to the Plant Protection Code has seen noticeable improvement (Langford, 2019). Additionally, more than 80% of certified STGs were recorded to have adequate storage and segregation facilities in their tea gardens (Consultivo, 2020).

Food safety impacts

All verified STGs and bought leaf factories have been introduced to food safety guidelines of the Tea Board of India and the Food Safety and Standards Authority of India on good hygiene and manufacturing practices through systematic training and assessment programs. The training and knowledge have led to increased awareness of the guidelines and facilitated their compliance, resulting in higher production of safe tea (Trustea, 2021).

Social impacts

From the beginning, Trustea has focused on achieving compliance with national and sector-specific labor laws among its target entities and STGs. The zero-tolerance approach and training on eliminating child labor (under 14 years of age, as per Indian law) and wage disparity have led to decreases in both at Trustea-verified entities (Trustea interviews). Workers are given extensive training on the handling of fertilizers using safety equipment, and the Trustea code only allows fertilizers and plant protection formulations that are non-hazardous and approved by the Plant Protection Code. These practices have reportedly resulted in reduced worker exposure to chemicals and improvement in their health conditions [Trustea interviews and (Consultivo, 2020)]. In 2020, Trustea further ramped up hygiene and sanitation requirements for certified entities in light of COVID-19, which led to the establishment of sanitizer provisioning facilities in tea estates.

Success factors

Enabling environment

The circumstances and enabling environment in which Trustea emerged have without a doubt been key to its success. The Greenpeace (2014) report was instrumental in raising awareness among Indian tea consumers and other stakeholders about sustainability challenges in the sector. Even after the Tea Board of India launched its Plant Protection Code, the clear gaps in the regulation of the domestic tea industry necessitated a self-regulation mechanism. The Tea Board of India therefore supported Trustea from the start, chairing Trustea meetings, sending out invitations, and gathering rapid approval from the entire industry. This then led to easy collaboration with other regulatory bodies like the Food Safety and Standards Authority, enabling the development and standardization of safety standards for tea.

Industry commitment and credibility

While regulatory endorsement created a push for the adoption of Trustea standards, a corresponding pull came from the strong commitment of market leaders like Hindustan Unilever, Tata, and Wagh Bakri, who controlled more than half of the tea market and made clear their preference for purchasing only sustainably produced tea. Trustea worked with research institutions like the Tea Research Association, as well, to ensure that its practices were backed and validated by the scientific community. Their involvement gives credibility to the code's manual and guidelines, and authentication to its requirements and benefits, leading to greater acceptability of the code in the tea industry.

A diverse governing council

The diversity of the Trustea council ensured that Trustea had access to domestic and international expertise, market knowledge, and networks to enable informed strategy and decisions. Its association with the international organization IDH, which had expertise in driving sustainability in supply chains of food commodities, tremendously aided in the development and drafting of the code (Langford, 2019). The support of domestic implementing partners like the Ethical Tea Partnership (associated with Trustea until 2019) and Solidaridad Asia (associated until 2018) provided an in-depth understanding of domestic tea production and supply chains. Their technical expertise ensured the successful development of the field implementation chain for the code, which resulted in higher compliance rates.

A shared understanding

The multi-stakeholder council has been able to function effectively around a shared understanding of the need for sustainability standards. Trustea holds multiple pre-engagements talks with prospective council members before inviting them in to cement their shared understanding. The council's consensus-based decision making and voting procedures aid in developing trust, and it is strictly enforced that all activities of Trustea are in a pre-competitive space; the only objective of collaboration among stakeholders is for achieving the common goals of the Trustea program. The shared outlook of the council members has also transformed into shared investment. Hindustan Unilever and IDH brought in the first funds, and their commitment reinforced the credibility of Trustea, motivating other stakeholders to step in. The funds contributed each year by funding partners are allocated against the activities that are planned for that particular year; this clarity, flexibility, and transparency works as a catalyst for establishing trust among the funding partners.

Interactive learning

As a business model, Trustea believes that a high compliance rate can be achieved among financially and educationally weaker audiences through interactive learning. Research shows that these audiences comprehend information better via live demonstration (Consultivo, 2020), which inspired Trustea's model farms and the creation of animated videos for STGs. The training manuals and education modules under the code are also creative and interactive and are made available to growers in their regional languages. In addition, Trustea-provided market intelligence on auction centers, purchasers, and new varieties of tea has ensured the interest and participation of STGs, bought leaf factories, and factories in estates.

An evolving code

Although Trustea is clear in its vision and goals, the diversity and magnitude of the Indian tea sector means that the model also has to be flexible and responsive to feedback from stakeholders. The initial version of the code launched in 2013 received a great deal of this feedback that was later re-worked into the current code, resulting in high acceptability and compliance. Further, in order to enhance the credibility of the Trustea code and accredit it with the globally accepted sustainability principles, Trustea has become a community member of the ISEAL Alliance, a global organization working toward tackling sustainability issues through a collaborative approach.

Future challenges

Tea is sensitive to the environment in which it is grown, and any change in conditions can affect production in terms of quality and quantity. Climate change is already being witnessed in tea-producing areas of India in the form of erratic rainfall, new pest infestations, and changes in temperature (Nowogrodzki, 2019). However, the Trustea code is yet to introduce guidelines on adapting to climate change for its verified units.

Another challenge is traceability. Trustea engages with STGs through estate factories and bought leaf factories, and both are stringent in ensuring that STGs provide them with tea produced to the Trustea standard. Though this chain of custody helps the factories maintain traceability and quality of tea, certain aspects bring down the efficiency of the process. The tea produced by bought leaf factories and factories, apart from being sold directly to big private players, is also sold through auction centers. The buyers at these auction centers may or may not care about the sustainability and quality of tea. When tea is sold to such buyers, there arises a possibility that factories will not be sufficiently compliant with the certification code. Though Trustea has introduced the Tracetea traceability application to overcome this problem, the application is still in its pilot phase and has a long way to go.

Public procurement is also an open question. Government institutions such as Indian Railways and the military Canteen Stores Department are major bulk buyers of tea, and Trustea is yet to tap into this market. This is a long procedure to traverse in the absence of factors like a sustainability-focused policy framework, advocacy, lobbying, and consumer demand. Though Trustea has had the support of the Tea Board of India, given the lack of coordination among different government ministries and departments, that initial support will not help Trustea in this respect.

Lastly, sustainability as a concept in tea is still nascent in India. Though Indian consumers are slowly beginning to recognize the importance of consuming safe and sustainably produced tea, there is a lack of knowledge and interest in recognizing and rewarding tea brands working on these parameters. Brands that have faced similar challenges in different industries in the past have spent copious time and money to overcome them. For example, in order to get Indian consumers accustomed to sanitizing their hands, the Savlon brand launched a massive campaign in India with the hashtag #NoHandUnwashed (exchange4media, 2020). Given this precedent, it will be interesting to witness how Trustea as a sustainable tea brand can overcome the existing gaps in consumers' minds and create a space for its Trustea seal in the Indian tea market.

Discussion

Safe Harvest was founded as an answer to farmers' demands for market access and product differentiation. As a case study, it demonstrates the capacity for impact when small and marginal farmers and their needs are centered in the innovation process. Safe Harvest created a new market category of “pesticide-free” products and supported FPOs to become supply chain partners, which was crucial for smallholder farmers who lack access to consistent market linkages and pricing mechanisms and who have no viable path to organic farming. Non-pesticide management and Safe Harvest's back-end design ensured accessibility for farmers in line with the vision for impact. Safe Harvest has been able to do this by keeping value-driven leadership at the helm and creating trust, long-term engagement, and collaborative capacities as part of its institutional design. Transparency and inclusiveness were key characteristics of its successful partnerships with FPOs, as opposed to top-down dynamics and transactionality. These choices also created operational sustainability by positioning farmers as primary stakeholders with a sense of ownership, demonstrated in the independence of partner FPOs, which are now engaging with other market players.

Safe Harvest has required continuous support from financiers who share its vision, align on the innovation model, understand the need for long time horizons, and are willing and able to creatively support a growing organization's changing needs. It has been able to find this by tapping into a network of diverse financiers in grants, debt, and equity, and the case displays the need for an aligned investor ecosystem for any ventures taking on similar challenges. Empowering localized economies and contextualized financing mechanisms can build pathways for ventures like Safe Harvest to flourish and grow, opening up possibilities of well-supported, value-driven, grassroots-centered social enterprises if supported by the right investment ecosystem.

The case of Trustea, meanwhile, carries important lessons on how self-regulated certification alongside strategically planned bundles of interventions can create impact on an entire value chain. Trustea has emerged as a significant player who successfully set up a sustainability standard for the Indian tea industry. Through its targeted focus on establishing a multi-stakeholder council and capitalizing on the skillsets of its members, Trustea ensured support from every key player in the industry. One of the most notable outcomes of the council was its ability to maximize the market hold and strength of players like Hindustan Unilever Limited and Tata Consumer Products and pull tea producers toward sustainability. The success of this multi-stakeholder initiative highlights the significance of alignment, clear goals, and well-defined operational procedures among such collaborators.

The initial support offered by the Tea Board of India played an instrumental role in Trustea gaining acceptability in the tea industry, underlining the ease which comes with the backing of a state regulatory body. The focus of Trustea on creating tailored capacity-building activities led to high compliance with its code, and working with varied value chain actors created interdependency among these actors, enabled the smooth operation of value chains, and developed accountability. Inclusivity in collaborations worked as another important factor for Trustea's scaling and outreach to a diverse audience. Continuous internal and external audits have aided Trustea in keeping track of compliance rates and addressing gaps. While it has achieved notable scale, it remains to be seen how the program can adapt and maintain its growth, build its brand image among Indian consumers, and deal with changes in climatic conditions.

Conclusions

A number of conclusions from these case studies provide learnings—not only for India, but also for other countries in the Global South seeking to enable innovation pathways toward sustainable agri-food systems.

Firstly, end users need to be placed at the center of innovation through sustained engagement and tailored, context-specific solutions. Even top-down programs (as both of our cases ultimately are) can maintain such bottom-up characteristics through a constant push by the leadership: building bottom-up communication channels, training and sensitizing staff, and instituting a project design that enables sustained community engagement. Safe Harvest and Trustea ensured that they weren't only top-down efforts; they actively worked with farmers and ensured information flowed both ways. The creation of Safe Harvest itself was driven by the need expressed by end users, and the needs of smallholder and tribal farmers were centered throughout the creation of FPOs, supporting access to finance, and the focus on pesticide-free as opposed to organic production. In both of our cases, we note that engaging and understanding end users and their context not only led to high uptake but also built trust and credibility among end users.

Trust is a transcendental element that is central to the sustainability of all stakeholder relationships, and thus of the innovation itself. It goes beyond trust with end users to trust between partners and the trust of funders. It's also inextricable from the values with which these private actors approach each relationship—and particularly relationships with farmers, where any extractive impulses must be countered. Alignment in long-term vision is key; Trustea, in its case, was able to work through a dynamic and diverse council because of its strong focus on establishing alignment within the stakeholders through multiple pre-engagement talks before formally collaborating with them. Trust is also established through evidence generation. Safe Harvest generates relevant evidence for its end users (both farmers and consumers) through its “zero certification” mark and the publicly available data from the verification tests behind it, while Trustea has been able to increase the acceptability of its code among stakeholders by engaging research and academic institutions to validate the code.

Our third conclusion is that leveraging formal and informal networks and organizations in the producer ecosystem can be an efficient and effective way to engage with a broader base. This was particularly observed with Safe Harvest, where existing FPOs were a route to scaling the farmer base of the program; outreach to smallholder farmers succeeded by leveraging the existing formal and informal social networks in the community, with a multiplier effect in scaling farmer engagement. In the case of Trustea, a private company invested in the preliminary development of a sector-wide standard and reached out informally to other players to set up a multi-stakeholder initiative that later became a formalized certification system. This reinforces the need to create room for informal interactions and actions where experimental ideas can be validated.

The fourth conclusion from these private-sector-led innovations is that government support may not be essential—but its endorsement certainly helps. This is in fact a key aspect of the enabling environment for even fully industry-based initiatives like self-regulated standards. In the case of Trustea, endorsement given by the Tea Board of India was invaluable in building credibility and trust in Trustea's vision with numerous stakeholders.

Fifth, a strategically crafted but continuously evolving bundle of interventions is essential for long-term success and scale. Bundling means implementing interventions in different areas simultaneously, such as market creation, business, policy, technology, or value chain development. Some of these areas may be within the zone of influence of the initiator, as with Trustea, where the development and promotion of the domestic standards was bundled with extensive capacity building of tea producers and awareness generation on sustainability. Other areas of intervention are outside the zone of influence of the initiator, and partnerships can enable the required bundling. For example, almost all of Safe Harvest's partner civil society organizations had highly trained agricultural professionals who enabled the development of rigorous internal systems to help farmers strictly adhere to non-pesticide management as envisioned by Safe Harvest.

Finally, partnerships drive success when they are crafted based on the needs of the innovation program, are managed rigorously, and evolve with the changing context. Staff and partners also must have a shared vision and be aligned on innovation goals. The Safe Harvest case shows that alignment to a long-term vision—including with financiers and suppliers—imparted resilience through tough times. Trustea conducted cautious pre-engagements before accepting new members into its council to ensure that all members, who might have competing interests, were well aligned with a long-term vision of sustainability in the Indian tea sector. Furthermore, the council's clear processes for decision making aided in developing transparency, trust, and communication.

It is no coincidence that partnership is so central to both of these cases. Given the many public, private, non-profit, and research entities now operating in India's agricultural landscape, partnerships seem certain to play a part in any innovation efforts—or, more likely, innovation networks—that will reach scale in the years ahead. The financial landscape will need to keep pace. Repurposed investments can power this innovation, but will also play a role in determining its direction; therefore, investors as much as all other partners have to be aligned on a vision of transitioning to more sustainable agri-food systems for India.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Written informed consent from the participants was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

AK led the execution of the entire project, provided inputs at every stage, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. NA contributed to the finalization of the research methodology, provided inputs for all case studies, and co-authored the discussion section. BJ led and authored the case study on Safe Harvest, provided inputs for all case studies, led the organization of the report structure, reviewed, proofread and edited the manuscript, and coordinated communication logistics. DG and ATJ co-led and co-authored the case study on Trustea. ATJ provided inputs on all case studies. PFC contributed to the writing of the manuscript and coordinated the publication process. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The research communicated as part of this paper was funded by the International Water Management Institute (IWMI) on behalf of the International Commission on Sustainable Agriculture Intensification (CoSAI). The grant that CEEW received from IWMI was a total of USD 73,250.

Acknowledgments

Based on a research project conducted on behalf of the Commission on Sustainable Agriculture Intensification (CoSAI) (Khandelwal et al., 2022). The authors from CEEW gratefully acknowledge the contributions of stakeholders and external reviewers who were central for case study and analysis development, and research validation. The authors appreciate the support and inputs provided by the CoSAI Secretariat as well as associated commissioners toward the drafts, analysis, and approach for the study. Finally, the authors thank Richard Kohl for his extensive support through the process of drafting and analysis.

Conflict of interest

Authors AK, NA, BJ, DG, and ATJ were employed by Council on Energy, Environment and Water. Author PFC was employed by Scriptoria Ltd.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^Approximate exchange rate: USD 1 = INR 73.81 in 2021.

References

Anil, R. K. (2019). “Linking farmer producers and urban consumers for pesticide free and safe food: Safe Harvest Private Limited,” in Farming Futures: Emerging Social Enterprises in India, eds A. Kanitkar, and C. S. Prasad (New Delhi: AuthorsUpFront), 340–375.

Asia Monitor Resource Centre (2010). Struggle of Tea Plantation Workers in North East India. Asian Labour Updat. Available online at: https://amrc.org.hk/content/struggle-tea-plantation-workers-north-east-india (accessed August 12, 2022).

Bhardwaj, T., and Sharma, J. P. (2013). Impact of pesticides application in agricultural industry: an Indian scenario. Int. J. Agric. Food Sci. Technol. 4, 817–822.

Chiodi Bachion, L., Barcellos Antoniazzi, L., Rocha Junior, A., Chamma, A., Barretto, A., Safanelli, J. L., et al. (2022). Investigating Pathways for Agricultural Innovation at Scale: Case Studies from Brazil. Colombo, Sri Lanka: Commission on Sustainable Agriculture Intensification. Available online at: https://wle.cgiar.org/cosai/sites/default/files/CoSAI_IPS_Brazil_final_0.pdf (accessed August 12, 2022).

Consultivo. (2020). Trustea Impact Report. Kolkata: Consultivo. Available online at: https://trustea.org/trustea-impact-report/ (accessed August 12, 2022).

exchange4media (2020). Ogilvy India and ITC Savlon take up Mission #NoHandUnwashed. exchange4media. Available online at: https://www.exchange4media.com/advertising-news/ogilvy-india-itc-savlon-take-up-mission-nohandunwashed-108417.html (accessed October 25, 2021).

Greenpeace (2014). Trouble Brewing: Pesticide Residues in Tea Samples from India. Bengaluru: Greenpeace India. Available online at: http://www.greenpeace.org/india/Global/india/image/2014/cocktail/download/TroubleBrewing.pdf (accessed August 12, 2022).

Grewal, A. S., Singla, A., Kamboj, P., and Dua, J. S. (2017). Pesticide residues in food grains, vegetables and fruits: a hazard to human health. J. Med. Chem. Toxicol. 2, 40–46. doi: 10.15436/2575-808X.17.1355

Gupta, A. K., and Lad, L. J. (1983). Industry self-regulation: an economic, organizational, and political analysis. AMR 8, 416–425. doi: 10.2307/257830

Gupta, N., Pradhan, S., Jain, A., and Patel, N. (2021). Sustainable Agriculture in India 2021: What We Know and How to Scale Up. New Delhi: Council on Energy, Environment and Water. Available online at: https://www.ceew.in/sites/default/files/CEEW-Sustainable-Agricultre-in-India-2021-May21.pdf (accessed August 12, 2022).

Jaisimha, L. (2019). 11 tea producing countries that won the world tea production game. Teafloor Blog. Available online at: https://teafloor.com/blog/11-tea-producing-countries/ (accessed October 18, 2021).

Khandelwal, A., Agarwal, N., Jain, B., Gupta, D., and John, A. T. (2022). Investigating Pathways for Agricultural Innovation at Scale: Case Studies from India. Colombo, Sri Lanka: Commission on Sustainable Agriculture Intensification. Available online at: https://wle.cgiar.org/cosai/sites/default/files/CoSAI_IPS_India_final_0.pdf (accessed August 12, 2022).

Langford, N. J. (2019). The governance of social standards in emerging markets: an exploration of actors and interests shaping Trustea as a Southern multi-stakeholder initiative. Geoforum 104, 81–91. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2019.06.009

Mati, B. M., Sijali, I. V., and Ngeera, K. A. (2022). Investigating Pathways for Agricultural Innovation at Scale: Case Studies from Kenya. Colombo, Sri Lanka: Commission on Sustainable Agriculture Intensification. Available online at: https://wle.cgiar.org/cosai/sites/default/files/CoSAI_IPS_Kenya_final_0.pdf (accessed August 12, 2022).

Moschitz, H., Roep, D., Brunori, G., and Tisenkopfs, T. (2015). Learning and innovation networks for sustainable agriculture: processes of co-evolution, joint reflection and facilitation. J. Agric. Educ. Ext. 21, 1–11. doi: 10.1080/1389224X.2014.991111

NABARD (2020). Farmer Producers' Organizations (FPOs): Status, Issues and Suggested Policy Reforms. Mumbai, India: National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development. Available online at: https://www.nabard.org/auth/writereaddata/CareerNotices/2708183505Paper%20on%20FPOs%20-%20Status%20&%20%20Issues.pdf (accessed August 12, 2022).

Nowogrodzki, A. (2019). How climate change might affect tea. Nature 566, S10–S11. doi: 10.1038/d41586-019-00399-0

Potts, J., van der Meer, J., and Daitchman, J. (2010). The State of Sustainability Initiatives Review 2010: Sustainability and Transparency. Winnipeg: International Institute for Sustainable Development. Available online at: https://www.deslibris.ca/ID/225909 (accessed August 12, 2022).

Rajbangshi, P. R., and Nambiar, D. (2020). Think, before you have your cup of tea! India Water Portal. Available online at: https://www.indiawaterportal.org/articles/think-you-have-your-cup-tea (accessed September 25, 2021).

Safe Harvest (n.d.). The ‘nature positive' revolution. Available online at: https://safeharvest.co.in/mission (accessed September 21 2021).

Saravanan, R., and Suchiradipta, B. (2017). Agricultural Innovation Systems: Fostering Convergence for Extension. MANAGE Bulletin 2. Hyderabad: National Institute of Agricultural Extension Management.

Sharma, N., and Singhvi, R. (2017). Effects of chemical fertilizers and pesticides on human health and environment: a review. Int. J. Agric. Environ. Biotechnol. 10, 675–675. doi: 10.5958/2230-732X.2017.00083.3

Shetty, P. K., Manorama, K., Murugan, M., and Hiremath, M. B. (2014). Innovations that shaped Indian agriculture—then and now. Indian J. Sci. Technol. 7, 1176–1182. doi: 10.17485/ijst/2014/v7i8.3