- 1Environmental Policy Group, Wageningen University and Research Centre, Wageningen, Netherlands

- 2Department of Agricultural Economics, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Nigeria

In many parts of the world, food consumption is shifting from mostly home-based to out-of-home due to transforming of everyday lives as a result of urban development and changing infrastructure. This trend has spurred the expansion of informal ready-to-eat food vending, particularly among the urban poor. However, informal ready-to-eat food vending practices have faced challenges in provisioning menu settings with high energy and calories foods. Moreover, there are concerns about the safety, health, and diversity of food purchased through ready-to-eat food vending. This paper explores practice-oriented strategies, suggestions, and mechanisms through key actors’ experiences and perspectives to understand how the provisioning of healthy and diverse food in informal ready-to-eat food vending can be improved in urban Nigeria as a future transformative initiative. A social practice-oriented approach, combined with participatory future visioning and back-casting, was employed in a multi-phase process of interlinked focus group discussions and workshops involving key food sector stakeholders. The findings reveal that achieving an increase in diverse foods and integration of fruits and vegetables requires changing food norms and promoting sensitization to the importance of diverse diets through training initiatives involving primary actors. Additionally, key skills/competences in the provisioning of healthy and diverse foods need to be learned and relearned, while adequate food materials, finance and effective and efficient integration of the different food vending practice elements are required for the realization of these initiatives. Furthermore, understanding the relationships between food vending and other food-related provisioning practices within the food vending environment is essential in transitioning to healthier and more diverse food provisioning in the informal food vending sector. Our findings provide insights for policymakers to provide strategic pathways for practical interventions to improve food vending practices that meet the food security and nutritional needs of the urban poor.

1. Introduction

Urbanization, complex urban infrastructural change, and rural–urban migration are transforming food consumption practices in cities in the Global South (Karamba et al., 2011; Adeosun et al., 2022a). One key change in food consumption brought about by these dynamics is the shift from home-based to out-of-home food consumption, particularly among the urban poor (Piaseu and Mitchell, 2004; Tsuchiya et al., 2017). In many developing countries like Nigeria, ready-to-eat food vending has expanded tremendously (Adeosun et al., 2022b). This has raised concerns about poor urban dwellers who disproportionally depend on out-of-home food outlets, for whom food insecurity intersects with multiple other challenges in daily life, such as inadequate housing and long working hours in informal jobs (Adeosun et al., 2022a). These developments suggest that out-of-home food consumption will continue to grow and this trend has a range of consequences. Recent research reveals that changes in daily practices such as mobility, work, and family life associated with socio-economic transformations in urban settings have contributed to increasing out-of-home food consumption (Thornton et al., 2013; Adeosun et al., 2022a). In response, out-of-home food provisioning is expected to align more along these situational dynamics to ensure the food security of the concerned groups consumers.

Despite their increasing reliance on out-of-home food, low-income consumers do not have absolute control over the kinds of foods and the composition of meals provisioned by food vendors, so their out-of-home food intake is limited to what these vendors provide. However, the kinds of food provisioned intersect with different dynamic activities happening within the food vending environment. This includes location specific activities such as of the employment context of consumers, the period of the day that food is being provisioned and the mobility dynamics of food vendors (Adeosun et al., 2022a,b). More so, research shows that even though food vendors are aware of nutrition imbalances in current food provisioned, profit-making takes priority in selecting the food they offer (Githiri et al., 2016; McKay et al., 2016; Adeosun et al., 2022b). Furthermore, the tendency for most out-of-home food consumers to stick to a particular food vendor they trust in terms of factors such as hygiene, food safety and sometimes the perceived satiety and energy the food provides, rather than the food’s nutritional benefits (Adeosun et al., 2022a), increases the likelihood of them consuming mostly monotonous diets. Even though some food vendors offer different food groups, some are provided and consumed in small quantities only (Adeosun et al., 2022b). Despite multiple benefits attributable to the intake of fruit and vegetables in daily diets, poor consumers still eat below the usual recommendation by (WHO, 2003). In most poor households in developing countries, Nigeria included, the consumption of fruits and vegetables is far below the minimum recommended level of 400 g per capita per day (WHO, 2003; Ruel et al., 2004; Lee, 2016).

Given these trends, it is therefore critical to consider how out-of-home food can be improved to enable consumers to access healthy and adequate diets. This study conceptualizes healthy food in a way that departs from a focus on individual choice alone to direct attention to the contexts of provisioning and consumption that shape whether and how consumers can access a diverse diet that includes a variety of food items and fruits and vegetables (WHO, 2015). In directing attention to the contexts of food provisioning and consumption, the paper investigates practice-oriented strategies and mechanisms that can aid improving the health and balance of ready-to-eat food.

Most studies on ready-to-eat food provisioning have until now focused on food handling practices, food hygiene, provision of high-calorie foods, and monotonous menu settings (Mwangi et al., 2002; Story et al., 2008; Muyanja et al., 2011; Lucan et al., 2014; Kolady et al., 2020; Adeosun et al., 2022b). However, it remains unclear how these interconnections and intersections of practices can aid the improvement of food vending practices in terms of the health and diversity of the ready-to-eat foods provisioned. In this research the study conceptualizes health and diversity of ready-to-eat food as two distinct aspects of obtaining an adequate diet through: (1) the integration of fruits and vegetables into menu settings and meals and (2) increasing the diversity of food groups provisioned.

In addressing this aim, the study builds on previous research on informal food vending in the Global South and in particular in Nigeria (Chukuezi, 2010; Leshi and Leshi, 2017; Dai et al., 2019; Kazembe et al., 2019; Resnick et al., 2019; Swai, 2019; Tawodzera, 2019; Wegerif, 2020; Zhong and Scott, 2020; Adeosun et al., 2022a,b). In doing so, this study adopts a social practice-oriented approach using participatory back-casting methods (Davies and Doyle, 2015; Oomen et al., 2022; Van der Gaast et al., 2022) to unpack practices, strategies and mechanisms suitable for improving food diversity in ready-to-eat food vending practices among the urban poor. A study by Davies and Doyle (2015) confirmed that only few studies in the domain of food vending apply back-casting using everyday social practices as their unit of analysis. Welch et al. (2020) studied the connections between social practices and regimes of engagement to understand future practices. Some studies applied visioning and back-casting in studying food futures in the Global North (Quist et al., 2011; Mangnus et al., 2019). For instance, Van der Gaast et al. (2022) employ social practice and future engagements in food entrepreneurship to understand possible transformations toward a sustainable food system. However, while the use of futuring and visioning methods has somewhat increased in food consumption research in the Global North, there is a lack of applying such methods in food studies in the Global South. This paper intends to fill this gap.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows: section two outlines the conceptual-methodological framing underpinning of study. In section three, we present the study context and the methods used to collect and analyze the data. Section four reports the findings from the study, which are discussed in section five to arrive at a conclusion on the implications of the insights generated for urban food system research and out-of-home food policy.

2. Conceptual-methodological framework

2.1. Visioning and practice-oriented back-casting methodology

A practice-oriented participatory back-casting method was applied to collect empirical information on visioning on ways to improve the health and diversity of ready-to-eat food provisioning during focus group discussions and as well as a stakeholders’ workshop. This combined approach was chosen because a social practice approach is inadequate for developing a normative direction to guide future transformational strategies. Thus combining a practice perspective with a normatively focused back-casting methodology can help to overcome this limitation to explore visions for alternative practice arrangements as well as pathways to their realization.

According to Davies and Doyle (2015), back-casting implies an overarching, multi-phased methodology. It starts first with generating future ambitions or possibilities and is followed by a process of back-casting which involves developing strategies, mechanisms and frameworks from the present to the future that can enable the realization of these future ambitions. Building on this, the approach employed in this study stimulates face-to-face interactions between diverse stakeholders who have some knowledge of food vending practices. It started with first generating future ambitions and was followed by a process of back-casting, which involved developing strategies, mechanisms and frameworks from the present to the future that would enable the realization of these future ambitions. According to Ahlqvist and Rhisiart (2015) and Kanatamaturapoj et al. (2022) present actions are crucial for directing how we think about the future in the present. The approach therefore allows for the co-creation of strategies for improving food vending practices in the present. The study therefore take every day social practices as the starting point for discussing present arrangements to enable future changes (Mandich, 2019; Welch et al., 2020; Oomen et al., 2022).

According to Shove et al. (2012), social practices might be transformed in different ways, for instance, by reconfiguring, substituting or changing how practices interlock (see also Spurling and McMeekin, 2015). Reconfiguring practices means rearranging one or more of the practice-elements (meanings, competences, materials) comprising them (Shove et al., 2012, 2015). Practices can also be transformed by substituting one practice for another to achieve the expected outcome. For example, consumers might shift from eating their lunch at home to eating it out-of-home. As practices interlock with other practices in practice-arrangement bundles, these connections may also change (Schatzki, 2002). For instance, the rise of out-of-home food consumption is interconnected to other related practices, including in food systems, the economy and the government. Consequently, attention should be paid to how transformations in routinised practices connect with dynamics in the wider socio-technical and socio-material contexts that both shape and are part of the practice. On a more situated level, daily food practices are linked with other practices in daily life, such as work and mobility. Thus identifying the linkages between these other practices allows for identifying options to re-arranging them and achieving the desired changes (Castelo et al., 2021). In this study, possibilities for more healthy and diverse food vending provisioning practices are explored through a lens that focuses on food vending practices and their arrangements with other related practices within the food environment.

The conceptual framework of this study envisages the changing interactions between food vending practices and governing practices and re-integrating the elements of these practices and how the practices themselves interlink to enable an improvement in the provision of healthy and diverse ready-to-eat foods.

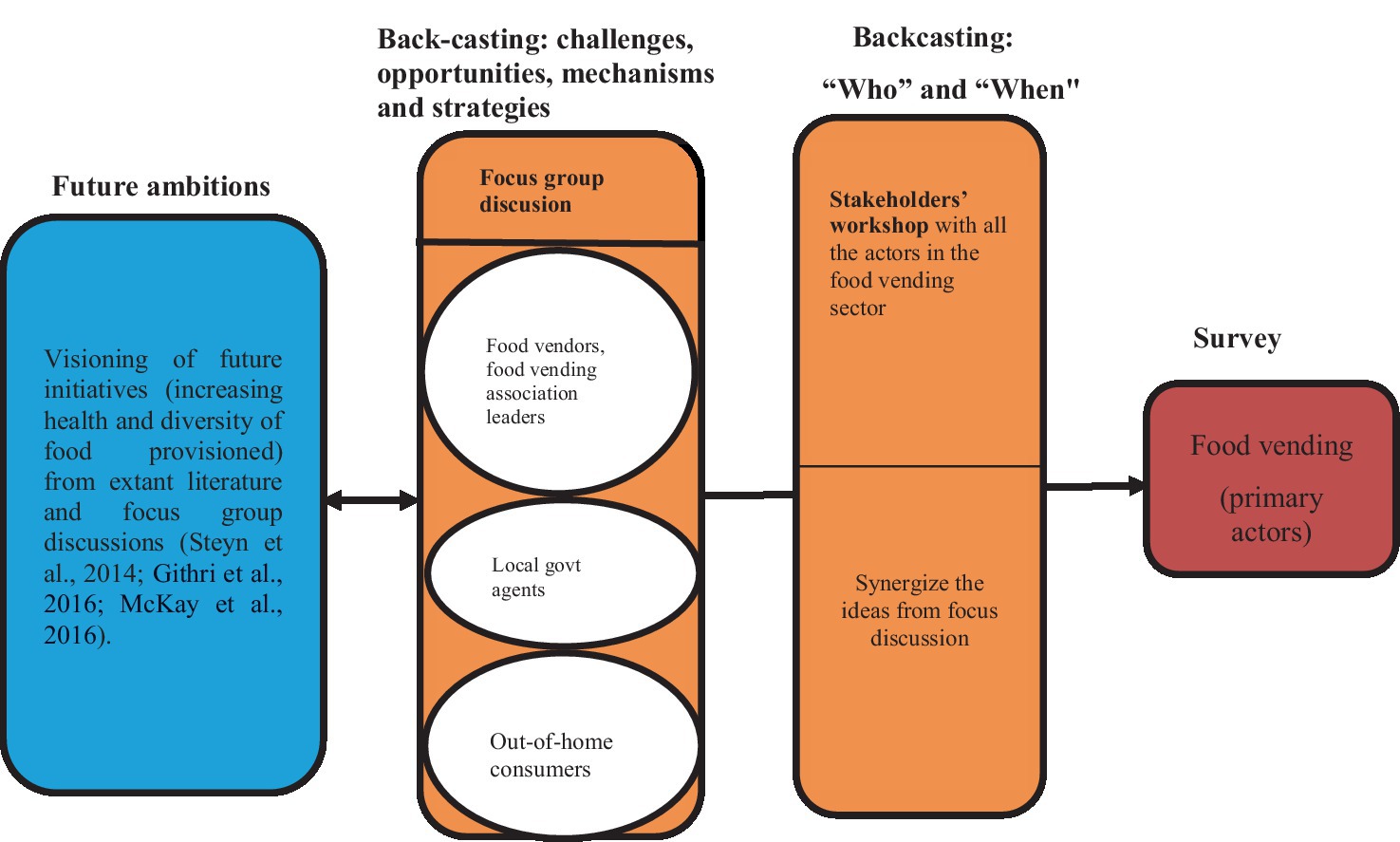

The process of envisioning future ambitions and practice arrangements was informed by existing literature and insights from focus group discussions concerning the delivery of healthy and diverse foods (Steyn et al., 2014; Githiri et al., 2016; McKay et al., 2016; Adeosun et al., 2022a). Using insights from the literature combined with insights from the focus group discussions, a picture of what the future food vending landscape should look like (the “what”) was generated. This was followed by back-casting to understand “how” this aimed-for future can be achieved and “who” should be responsible for particular actions and the probable prospects and challenges it may face. The process of visioning and back-casting used in this study followed two stage of visioning and back-casting.

The focus group discussions involved stakeholder-specific discussions. During these discussions, back-casting of key challenges, opportunities and mechanisms and strategies for the envisioned future initiatives (i.e., improving health and diverse ready-to-eat foods) provisioned were co-generated. The practice-based approach helped to embed this discussion in the changes, re-arrangements, and transformations of food vending and governance practices.

The results from the focus group discussions and the stakeholder workshop were further deployed to see whether they are practicable, implementable and will be widely adopted by the majority of the primary actors, i.e., the food vendors. A semi-structured questionnaire seeking to gain a wider view on food vendors views on the proposed visions and strategies was designed and administered to randomly selected food vendors from the study area. See Figure 1 for an overview of the methodological process.

Figure 1. Participatory practice-oriented visioning and back-casting methodological process (adapted from Davies and Doyle, 2015).

3. Research context and methods

3.1. Study location

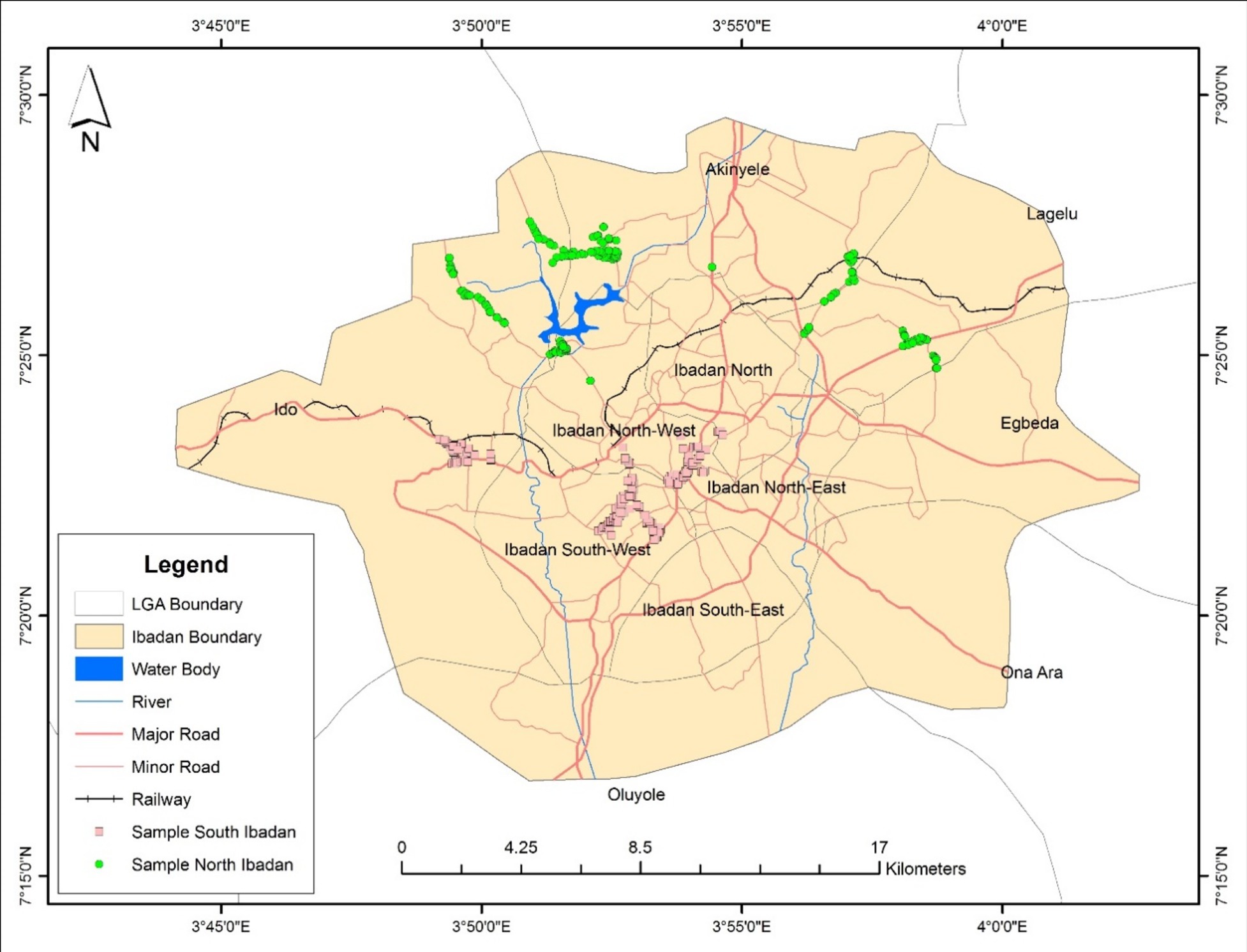

The study is carried out in Ibadan, Nigeria. Ibadan is one of the largest cities in Nigeria with about 4 million inhabitants (Adelekan, 2016). As an ancient city, it accommodates different ethnic groups and people from different religious backgrounds. It has about 11 local government areas (LGAs) with five in the city metropolis and six in the peri-urban area where the majority of the low-income people reside. Most people in these communities live below the standard urban poverty line of $1.90 per day (UNDP, 2004). The study selected these poor urban communities because relative to other social groups in the city, they rely most prominently on ready-to-eat food provisioning.

3.2. Food vending mapping

The study took a census of food vending outlets in the selected communities using Geographical Information System (GIS) to provide a spatial overview (see Figure 2). This method was applied to represent and analyze the food vending environment in the study area based on three identified food vending categories, that is: (1) traditional cooked meals local foods such as cooked rice, yam, soups, pounded yam, cassava mash “eba” and cassava flour “amala”; (2) processed foods (fried foods, roasted foods, smoked, snacks and beverages); and (3) unprocessed foods (fruits and vegetables). Six hundred eighty-six food vending outlets were mapped by taking the coordinates of all the food vending outlets in the selected communities, including 319 traditional food vending outlets, 268 processed food vending outlets and 98 unprocessed food vending outlets. From this larger sample, The study selected a diverse sample of food vending outlets for participating in the focus group discussions, stakeholders’ workshop and survey.

3.3. Sampling procedures

An exploratory sequential mixed-method design was applied in the sampling and data collection. This approach was applied to generate a broad range of empirical data. The sample for this study was selected on the basis of information from the state ministry allowing us to categorize the Local Government Areas (LGAs) in Ibadan. Based on this information, The study selected the lowest income LGAs, as areas where a majority of low-income residents live, for further investigation. To ensure a good representation of the study area, the study purposively (based on their revenue size) selected two LGAs from the Northern part of Ibadan where seven LGAs are located, one LGA from the Southern part of Ibadan where three LGAs are located and one LGA from Central Ibadan, located at the boundary between the Northern and Southern parts of the city. Thus, in total, four LGAs were selected as the sample area for the study and within each LGA, two communities were randomly selected as sites for the study.

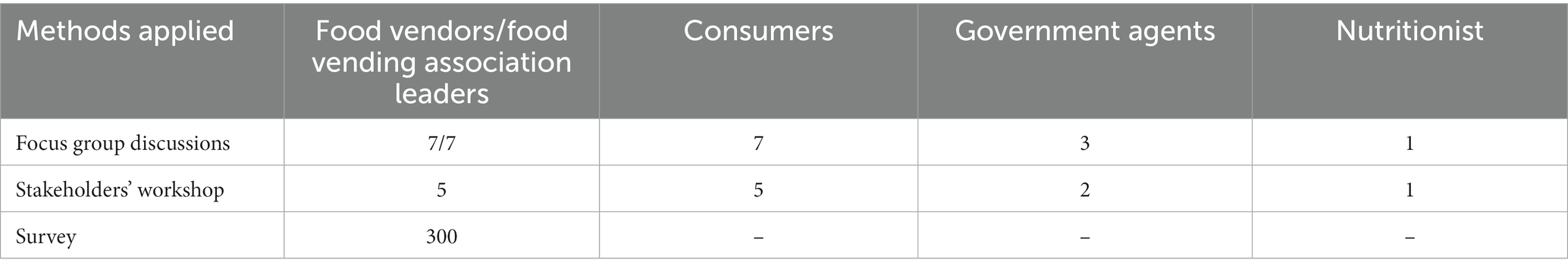

The study developed a multi-modal approach that started with focus group discussions involving different food vending stakeholders. This was followed by a stakeholders workshop that brought them all together and a larger quantitative survey among the food vendors. Based on the particular research method, concurrent sampling techniques were applied. First, the study selected different groups of stakeholders for a series of four stakeholder-specific focus group discussions, i.e., (1) two groups of seven food vendors including food vending association leaders (elected leaders that supervise and manage the affairs of the food vending association); (2) one group of three local government agents who supervise the activities of food vendors and a nutritionist from the University of Ibadan, and (3) one group of seven out-of-home food consumers. These amount to a total four focus group discussion meetings conducted. For the stakeholders’ workshop, the study included 13 stakeholders: (1) five food vendors including food vending association leaders, (2) five out-of-home food consumers, (3) two government agents and a nutritionist. These stakeholders were selected from the participants in the focus group discussions to participate in the stakeholder workshop. The overview of methodology applied and food vending’s stakeholders selected are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Showing different methodology applied and the numbers of food vending stakeholders selected.

Quantitative data were obtained from 300 food vendors who were systematically selected from the list of each food vending outlet’s category mapped and a semi-structured questionnaire was administered to collect their opinions. Based on the mapping results, three lists of food vending categories were produced, and considering the size of each list, a systematic sampling was applied to select the respondents for the survey. Thus, 165 respondents were systematically selected from the list of traditional food vending, and 135 respondents were systematically selected from the list of processed food vending. Only traditional and processed food vending was considered in this study because they provide low food group diversity (Adeosun et al., 2022b). The consent letter was read to the respondents in their local language to seek their consent and the study only interviewed the respondents that gave their consent verbally, while, those that did not give consent were not interviewed.

The respondents were selected from across the four selected local government areas, based on their readiness to participate in the discussion as well as on specific conditions. These conditions differ per category: food vendors should be at least 5 years in service, association leaders should be active in service and have spent at least 1 year in that position, government agents should be from an office linked to food vending activities, consumers should regularly use out-of-home food (at least one meal out-of-home every day) outlet and rely on different categories of food vending. These criteria were applied to receive first-hand information from practitioners and stakeholders who have a wide range of experiences in food vending. Field work was organized by the first author between July to September 2022, with the support of four research assistants.

Data from the focus group discussions and stakeholders’ workshop was recorded, transcribed, and coded inductively using (Atlas. ti). The open codes that were identified were then analyzed, compared and grouped into categories. An iteration between inductive and deductive analysis was used for particular themes and patterns and then this data was reviewed and further categorized in accordance with the social practice approach.

4. Results

This paper aimed to understand future strategies and mechanisms that can contribute to improved food vending practices in the contexts of health and diversity of food provisioned. Taking a nuanced approach the study analyzed different interconnections and interactions of practices, (sub) practices, elements of practices, and elements of governance that can support the future improvement of food vending practices. The study presents the findings under the following headings: first, the study analyzes the views of food practitioners (vending and consumption) on the benefits of increased health and diversity of food provisioned. This is followed by the expected future strategies. Different suggestions were made on practice-oriented mechanisms, including learning practice meanings, norms, competences and materials, as well as reshaping links and synergies among different food markets within the food vending environment and establishing more effective and efficient regulatory frameworks guiding food vending practices. The last section of the results is based on the envisioned challenges and implementation process.

4.1. A paradigm shift in food vending practices

While there is variation among the different food vending categories (Adeosun et al., 2022b), changes in the ready-to-eat food vending practices are indispensable for ensuring healthy and adequate diets. The study explored potential arrangements and interconnections between different practices, that can support these needed improvements.

4.1.1. Future benefits of increasing the health and diversity of ready-to-eat food provisioned

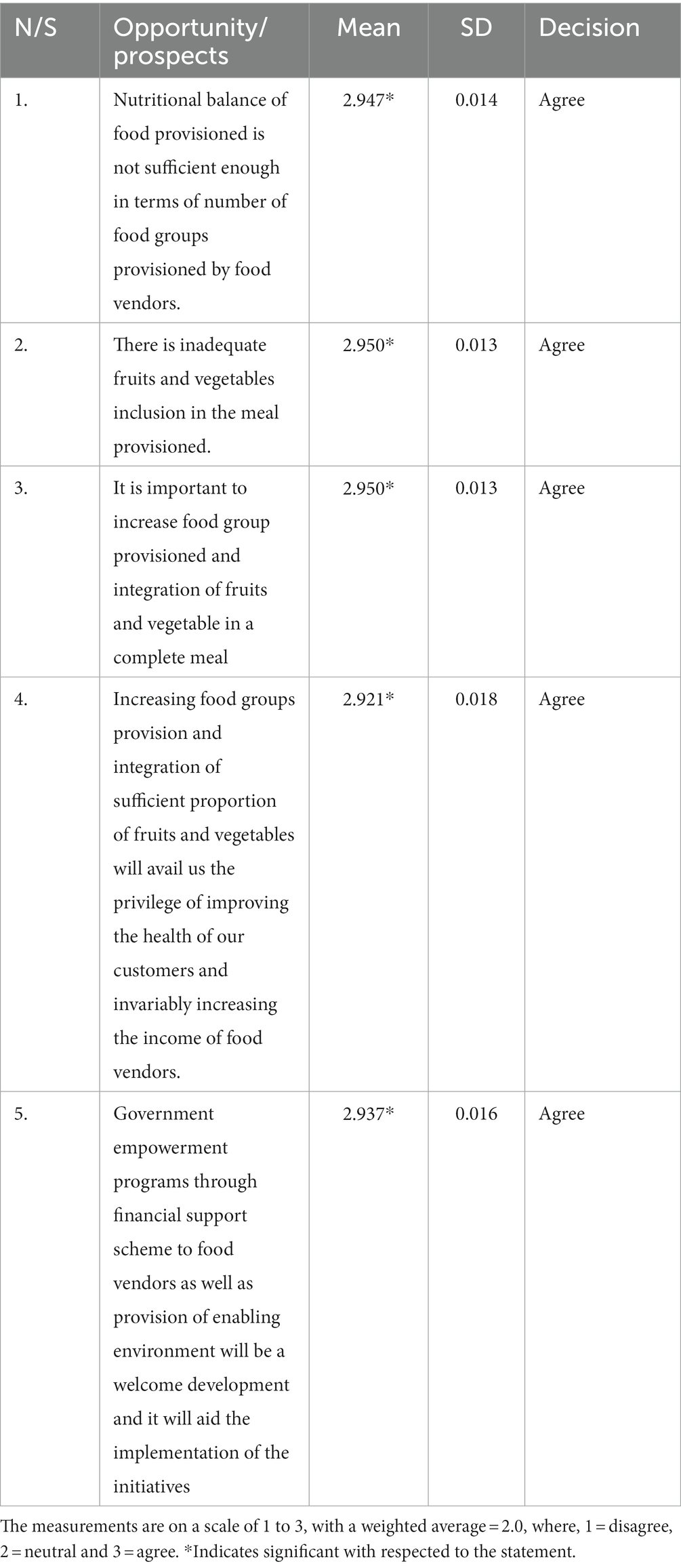

Table 2 presents the vendors perceptions of the benefits of increasing the health and diversity of food provisioned and the possible processes of achieving this in the future.

The results showed that vendors agree that the food currently provided is not sufficiently diverse and that there is inadequate integration of fruits and vegetables in the meals provisioned. This was also a viewpoint shared with the wider stakeholder groups. During the stakeholder focus group discussions, it was reported that an increase in the diversity of the foods provided offers an opportunity for consumers to access more healthy diets.

… Increasing food groups provision and inclusion of a good proportion of fruits and vegetables will avail us the privilege of improving the health of our customers and invariably increasing our income as vendors, (FGD, food vendor).

… It is quite necessary for the food vendors to increase their menu settings because of the nutritional level we obtain from different varieties of food, each food supplies different nutrients to the body, more so as the adage goes that health is wealth, (FGD, nutritionist).

The majority of the food vendors also confirmed that increasing the number of food groups and an integration of sufficient fruits and vegetables is a welcome future initiative. The stakeholders agree that fruits and vegetables should be integrated in meals rather than provisioned as a separate dish as some consumers may not be interested to purchase it this way. This is important as the WHO (2015) recommends that 400 g of vegetables are consumed by individuals per day. Consumers in particular reported a need for food vendors to lead by integrating more fruits and vegetables into meals at affordable prices:

… I would rather prefer fruits and vegetables integrated into my meals when I go to the food vending outlet and to not eat them necessarily as a sole meal, (FDG, consumer).

However, despite this general agreement, most stakeholders agreed that current food norms and practices as well as limited availability of diverse and healthy foods impeded this:

… Most of the foods we eat outside of our homes are starchy foods with inadequate vegetables. We are just managing them since we have little or no option once we are out of our homes, (FGD, consumer).

For out-of-home food consumers, increasing the degree of food group diversity provisioned was understood as providing access to more variety of food items, thus enabling more diverse nutrient intakes, and enjoying good health through consuming an adequate diet. Food vendors were also seen as benefiting from a greater diversity of food groups as they generally also consume the meals they provision (Adeosun et al., 2022b).

… Our customers will have easy access to a adequate diet at their door steps and we the food vendors make more profit providing nutritious food for them, (FDG, food vendor).

The food vendors asserted that having additional varieties of foods to provision without reducing the number of existing food items provisioned will likely increase patronage as well as their business’ profit. This implies a win-win situation for both parties (vendors and consumers).

… The benefit we will enjoy is that we will be able to make better choices of the right combination of different classes of foods, (FDG, consumer).

4.2. Expected future changing strategies

4.2.1. Changing food norms and sensitization

For both initiatives (increasing food group diversity and integration of fruits and vegetables in meals) to be fully accepted, there is a need for proper and intensive understanding of changing food norms and sensitization among both food vendors and consumers. The stakeholders reported that first the consumers and food vendors should be educated about the need to increase fruits and vegetables in daily diets. The government and food vending associations should have a mutual agreement in bringing food vendors together to educate them on the reasons why they need to change their menu settings and how they can go about it and benefit in terms of profit making.

This would involve challenging a belief, especially among the urban poor, that stresses the quantity rather than the quality of the food consumed. The government can play a critical role in this sensitization through public awareness campaigns using different media (i.e., TV stations, radio stations, newspapers, and social media). In particular using sell-designed jingles into these campaigns will drive home the importance of consuming fruits and vegetables and more food groups.

… I think there is a need for the creation of awareness not only among the food vendors but also among the consumers because if the food vendors increase their menu and the consumers are not ready to buy, the seller will be at a loss, (Stakeholders’ joint assertion).

The food vendors reported that they may change their provisioning strategy and provide different types of food at different periods of the day. For instance, they can have a timetable for provisioning different classes of foods so their customers know when a particular type of food is available. Likewise, their presentation might change because each type of food has a unique presentation style.

The different stakeholders are of the opinion that the campaign for increasing the provision of fruits, vegetables, and diversity of food groups should be linked to health benefits to enable both vendors and consumers to understand and absorb these initiatives. This is because the ideas cannot be forced upon food vendors or consumers. Rather, they should find ways to educate them on why these initiatives are important. Probably, the government can aid this via the food vending association leaders by organizing training, seminars, and workshops.

… The government can also help in the area of publicity by creating awareness among the public about the benefits of eating vegetables and fruits in sufficient quantity, (FDG, government agent).

Non-governmental organizations and food vendors can also take the role of enlightening consumers about the essentials of the initiatives. This should also include efforts to improve engagement through embodied knowhow. For example, stakeholders discussed how awareness can also be increased through demonstrations by food vendors in public places by offering tastings of new dishes and speak with consumers about the nutritional importance of the menu settings provisioned.

4.2.2. Training needed for future changing food vending practices

This section presents the food vendors’ perspectives on the possibilities, prospects and strategies embedded in the envisioned transformative initiative in food vending regarding the increasing food groups and integration of fruits and vegetables.

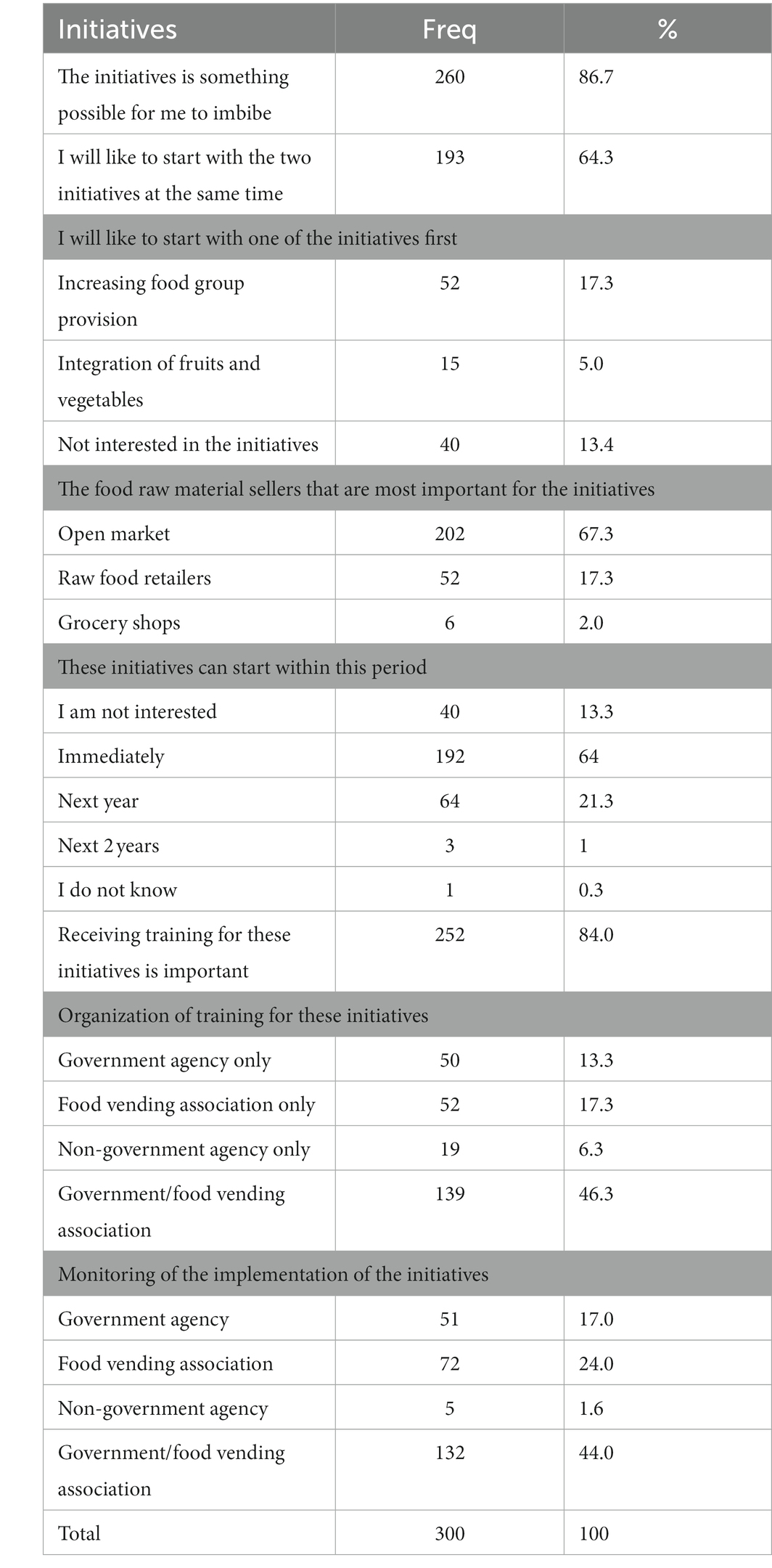

The food vendors reported that for these initiatives to be materialized, they need to procure new cooking utensils, improve existing skills and learn new skills. Changing food vending practices was recognized as a process that requires support and training to enable vendors to acquire the necessary skills and competences. Healthy and diverse food provisioning requires vendors to go beyond what they presently do. For example, as the number of food items increases, they need to develop skills to manage different food types, increase their menu settings, and discover ways to increase their income. Thus, the importance of training on increasing the variety of food groups provisioned and the integration of fruits and vegetables in meals was strongly emphasized. A food vendor will only prepare what he/she is skilled at, but once he/she has knowledge about different methods of preparation, different food items can be added to the menu. Food vendors in the survey also supported this, with about 84% asserting that they like to undergo training to improve health and diversity of ready-to-eat food provisioned. Regarding the organization of the training, about 46.3% of the food vendors suggest that collaboration between government agents and food vending association leaders is the most effective option (Table 3).

Table 3. Food vendors’ perspectives on increasing food group provision and integration of fruits and vegetables provisioned.

… Some of our fellow food vendors who are not exposed to these different food preparation methods before would have to go and learn it. For instance, a vendor amongst us who hasn’t prepared salad before will have to go learn it for the sake of its necessity and inclusion (FDG, food vendor).

The stakeholders also reported that such training is needed and should be organized by the government in consultation with food vending association leaders. Trained food vending association leaders can then train their members at their various clusters in developing new competences and skills. Trainings should be accessible and motivate the food vendors to adopt the content.

… I can tell you that the language of people those food vendors listen to and comply with is their association leaders (FDG, government agent).

In the past, the government has organized a series of trainings with food vendors centered on food safety and hygiene practices, which generally had positive impacts on vendors. A training specifically focused on health and diversity of ready-to-eat food provisioned and the skills and competences needed for increasing the variety of food groups and the integration of fruits and vegetables could be usefully integrated here.

… Although our training has been on sanitation, food hygiene, personal hygiene, and how to prepare their meal in a neat environment, the government can also include the food nutrition balance benefit in the training (FDG, government agent).

Access to material resources in the context of executing the initiatives is important as the food vendors would need to add additional materials and the government could acquire more resources for training, sensitization and coordination. Trainings should also integrate information on prices, free training opportunities, loans and grant opportunities. There is a need to form synergies between nutrition experts, government, and food vending associations in organizing trainings. The food vendors further suggested that trainings would be more accessible if they were organized on a zonal basis.

4.3. Practice-oriented mechanisms

4.3.1. Materials and financing

The focus group and workshop discussions revealed practices and practice arrangements that can contribute to the execution of the proposed healthy and diverse food initiatives.

Important practices that would need to change to support more healthy food include food preparation and preservation techniques, food procurement processes, storage and stocking, menu-setting and vendor-consumer relations. These require hiring more staff to work in the food vending outlets, buying new kitchen tools, such as pots, more plates, bowls, different sizes of cutlery, equipment such as a freezer for the preservation of foods, and a generator for constant power supply and many more. They might also need to re-position their staff due to the expansion of activities in the food vending outlets.

… I will surely need more hands in food preparation since I will be preparing many food items (FDG, food vendor).

The visioning and back-casting discussions identified different mechanisms that may need to be adopted in sourcing additional food materials. For example, procuring more food will impact the current way of sourcing food. As they require larger quantities, vendors need to transport raw food materials via reliable ways from their providers in the open market using logistic staff. This would require a shift from cash to online payment. It is also likely to impact the temporality of procurement practices: procurement of food currently occurs every day or every 3 days but may be adjusted to a weekly or bi-weekly basis. As it is envisioned, vendors would have less time to go to the market due to the increased labor demand at the vending outlets associated with the preparation of healthier and more diverse meals. This means they may buy larger quantities in fewer shopping trips or employ logistic personnel. To accommodate the changed procurement practices, storage practices would also need to change in the future. Storage space, infrastructure and materials will need to be improved, bought, or replaced. Since more food items need to be provisioned, current practices of selling all food items in 1 day are likely to be replaced by practices that allow for food to be preserved for several days. This means an increased demand for storage facilities for stocking and restocking prepared food items and raw food materials to preserve perishable foods and prevent it from being attacked by animals.

… I can get people to help me construct a safe cabinet for stocking food raw materials to save me the stress of going to the market every day (FDG, food vendor).

The stakeholders agreed that food vendors would need financial support to be able to effectively engage in the new initiatives. Previous studies revealed that most people in food vending practices are of low-income status (Panicker and Priya, 2020). Therefore they will need more finance to be able to add to their menu settings. Stakeholders believe this support can come from either the government, food vending associations, or non-government organizations. The government can empower vendors through financial support schemes as well as by creating an enabling environment.

… The support that we need is that of finances, for instance most of us use soft loans and thrift to support our food provisioning business (FDG, food vendor).

There is a need to support training programs for food vendors, equip farmers, and reduce the levy for food vendors. The food vendors believe that more support for farmers would positively impact the price of food raw materials who may sell their raw food materials at a lower price. The government can aid the implementation of these initiatives through an economic-friendly policy formulation and the creation of wider public awareness. Food vending associations in connection with the government can roll out proposals to banks and other financial bodies to finance training programs for its members and seek soft grants or loan schemes for their members to provide them with the means to effectively take up the initiatives.

4.3.2. Regulations

The focus group discussion included back-casting of different governing practices and arrangements that can support the envisioned future. Different governing practices and how they interconnect in shaping the future improvement of ready-to-food vending practices were identified. The stakeholders discussed and brainstormed governing practices that can increase the rate at which the initiatives are implemented in themes related to coordination and monitoring, to controlling and supervision, and to implementation. The results are presented below.

Coordination of transformations in the food vending sector can be carried out by both the government and association leaders. Food vendors trust and listen to their association leaders more than to any other stakeholder. Hence, whenever the government seeks to influence food vendors, they seek to mediate this through the food vending association leaders.

… This new initiative can be successful when the coordination is done by the leaders of the food vendors association with the support of government agents. They are the closest to the food handlers (FDG, government agent).

The focus group discussions suggested that the association leaders should play a major role in the coordination and monitoring of the activities supporting future initiatives. Therefore, there must be a good understanding between the government and food vending leaders about the aim and the importance of the future initiatives, as that would make coordination easy. The food vending association leaders should champion the coordination with the support of the government agents. The leaders can take advice from the government agents on how to ensure voluntary compliance by the food vendors. Constant inspection at the point of operation of food vendors by government agents and association leaders will make the implementation of the future initiatives more effective. The government can carry out monitoring by improving the policies and guiding the actions and operations of food vendors in the communities. This can be achieved through roundtable meetings between the government agents and the food vending association leaders. About 44% of the food vendors in the survey believe that monitoring the implementation of initiatives will be effective if it is inclusively executed (Table 3).

To avoid price disparity for similar food items among food vendors, price control and standardization must be considered. The government can also support the initiatives by setting up a quality control agency that involves the leaders of the food vending associations and nutrition experts.

… Key leaders among the food vendors must be contacted first, sensitized about the new initiatives after which, they can be released to disseminate and step down the idea to their colleagues at the grassroot level (FDG, government agent).

4.4. Synergies within food vending environment

4.4.1. Raw food markets

The food vendors reported that for the initiatives to be successful they need the support of other actors. Actors, such as unprocessed food (fruits and vegetables) sellers, raw food retailers, open wet markets, and small grocery shops, are important for ensuring accessible and stable raw food material supplies. About 67.3% of the food vendors perceive that open markets will be important in supplying raw food materials, while about 17.3% indicate that raw food retailers will be important (Table 3). Raw food suppliers could play an essential role in reducing the burden of procurement. In this case, food vendors could more easily call on them to supply the needed ingredients through delivery.

… I would not need to stress myself going to the market as people who are selling fruits and vegetables here can help me buy in bulk from the market (FDG, food vendor).

4.5. Envisioned challenges and implementation process

Starting new initiative the initiatives to provision more food groups and the integration of fruits and vegetables come with their own future challenges and depend on ongoing dynamics. Some of the challenges that could hinder the rapid implementation of this scheme include a lack of sufficient staff at food vending outlets, inadequate start-up capital, and lack of storage facilities. Other constraining factors discussed include the instability in governmental policies, the persistent rise in the price of food commodities, the erratic power supply, and the vendors’ and consumers’ resistance to change.

Adding more food groups may also reduce the patronage of existing food items. For instance, if a food vendor is selling four food items before and she decides to add two food items, this addition is likely to reduce the sale of the existing ones. The food vendors also reported that the increase in food group diversity will largely depend on the prices of the food raw materials they get from the market.

… Another issue is the uncertainties that may come with consumers’ acceptance of the initiatives. This can be handled by starting with a small quantity at first and then improving on that later as demand increases (FDG, food vendor).

The integration of fruits and vegetables into meals may likely lead to an increase in price per meal and vendors do not know if the consumers will be ready to pay for this.

It was, however, recognized that these initiatives will not only have positive but also negative effects for food vendors. For instance, positive effects may include access to diverse diets and an increase in profit in the long run, if the consumers patronage increased. Negative effects might encompass an initial loss of profit due to consumers lagging to adopt the new food groups.

Food vendors are of the opinion that a process of incremental change is the most feasible option. For instance, they may start with two or three food groups and see how consumers respond. According to the survey (Table 3), about 64% of the food vendors believe that the implementation of initiatives in an incremental fashion can commence immediately, while, 21.3% indicate that this process should start next year. Similarly, about 86.7% of the food vendors surveyed agree that the initiatives are possible and they can imbibe them in the future. Also about 64.3% of the food vendors indicate that they can undertake both initiatives (increase diversity in food group provision and integrate fruits and vegetables into a meal) at the same time, while, 17.3% prefer to start first with increasing food group diversity and 5% to start with the integration of fruits and vegetables (Table 3).

5. Discussion and conclusion

The study presents deeper insight into how informal food vending practices can be improved to deliver healthy and diverse foods to the urban poor. The study presents its findings to corroborate with existing literature on identifying practice-oriented processes that can enable/engineer solutions to multiple challenges and shortcomings of ready-to-eat food vending practices in the Global South (Mattioni et al., 2020; Adeosun et al., 2022b; Bezares et al., 2023). Being the most commonly used food provisioning outlet among the urban poor (Mwangi et al., 2002; Steyn et al., 2014), ready-to-eat food vending is an important food supply channel through which to focus attention in efforts to achieve healthy and diverse food systems. This study takes a practice-centered participatory back-casting methodological approach to explore mechanisms, strategies, and empirical information that can aid the improvement of urban food vending practices.

Our methodology and practice-oriented approach enabled us to analyze the “future in the present,” and provided an analytical framework to understand the improvement of food vending practices. In doing so, we have responded to the call by Van der Gaast et al. (2022) for more research on the interactions between near and distant futures in different contexts and circumstances. Our approach deviated somewhat from the usual application of visioning and back-casting by implementing both into a process that involved two stages of visioning combined with one stage of back-casting. Previous studies have employed back-casting and visioning approach to other situational dynamics (Bibri and Krogstie, 2019; González-González et al., 2019; Sisto et al., 2020; Soria-Lara et al., 2021; Villman, 2021) but none has been applied in the study of informal ready-to-eat food vending. The application of our method of two-staged visioning and back-casting may also be applied to analyze challenges and solutions for other components of the food system in the Global South.

The results from mapping the food vending environment indicate that out-of-home food provisioning has expanded and continues to expand in the food landscape. These observations underline the importance of food vending for the food security of the urban poor. This agrees with the findings of Swai (2019) and Tawodzera (2019) that street food vending is expanding and serving most people food needs in the city of Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania and Cape town, respectively. Most out-of-home consumers depend on street foods for at least one to two of their daily meals and they patronize food vendors for their daily meals regularly (Ogundari et al., 2015). This implies that any transformation toward improving food vending will directly benefit the urban poor consumers.

First, we analyzed the perspective different stakeholders have on the prospects of food vending and we found that there is wide agreement that transformations in the food vending sector are overdue and necessary to adequately meet the nutritional needs of consumers. According to Mwangi et al. (2002), a high proportion of food vendors do not sell food that is sufficiently diverse for a healthy diet. If consumers have access to and consume an adequate diet, this will be reflected in their health. According to Branca et al. (2019), transforming the food system can contribute to reducing non-communicable diseases. This study found that this transformation should entail two initiatives: (i) the increased consumption of fruits and vegetables and (ii) access to more diverse diets that include a broader range of the different food groups. The stakeholders reported that it is important that fruits and vegetables are integrated into meals sold in the food outlets rather than servicing them as separate meals. This is also important as WHO (2015) recommended that 400 g of fruits and vegetable should be consumed per day. This way, low-income consumers can have access to a portable meal with fruits and vegetables as well as an adequate diet at affordable prices. However, the stakeholders suggest that more is needed for these initiatives to be successful. Both food vendors and consumers should be made more aware and sensitized on the competencies that are needed for the success of these initiatives. According to Panicker and Priya (2020) street vending can supply healthy and nutritious food to consumers if it is well organized.

Extant literature further indicates that some out-of-home food consumers prefer to eat food that has high satiety value, can fill their stomachs quickly and enable them to withstand their often physically intense daily jobs with a consequence that they ignore healthy foods (Adeosun et al., 2022a). However, consumers should be encouraged to seek food that can suits their physical demands as well as provide enough nutrients, i.e., an adequate diet. Even though consumers follow their normal food routines, changes in a practice they are connected to can change the actual food they consume. Since, food consumption practices are interconnected with food vending practices (Adeosun et al., 2022a), transforming food vending practices can lead to changing food consumption practices.

Second, the starting point in transforming food vending practices should be a focus on changing food norms and practices through training-related activities supported by the government and food vending association leaders. NGOs aiming for increasing the consumption of healthy foods should also be carried along in implementing the initiatives. Training of food vendors centered on the know-how of the necessary skills and competencies and material resources usage required to execute the initiatives is indispensable. The stakeholders suggested that such training should be organized by the government with the collaboration of the food vending association leaders. This suggestion is in line with insights from research that highlight mutual understanding between the government and food vending association leaders on organizing training for food vendors (Zhong et al., 2019).

Third, the study analyzed different elements that are integrated to form the social practice of ready-to-eat food vending. Seeking to transform these, existing practice-elements and activities may need to be adjusted, changed, or supplemented. From our findings, adjusting practice-elements and processes that include skills, material resources, and capital are considered essential for the implementation of the initiatives. Buying additional food raw materials, kitchen utensils, other food preparatory materials and effective storage facilities will be needed to accommodate more food materials to be stored and ensure they are prevented from being spoiled and eaten by rodents. In addition, the initiatives will require more capital as they have to buy additional food and other materials. The study suggested that such capital can come via soft loans from the government as a special package for these initiatives. NGOs can also provide financial support to food vendors. From our findings, confirming Herrero et al. (2020), it can be inferred that transforming food vending components of the food system involves the re-integration of key practice-elements such as procurement of raw food materials, storage facilities, food preparation and presentation, stocking, and re-stocking.

Fourth, the study analyzed how interconnections between food vending and governing practices can support the implementation of the initiatives. We found that governing practices can drive changes in food vending practices. The government should play this role in conjunction with food vending association leaders. This is because food vendors trust and listen to their leaders more than to government staff. This implies that for formal actions to be effective in informal settings, the stakeholders of the informal settings need to be included from the start of the discussions. According to Vermeulen et al. (2020) bottom-up and top-down approaches to dietary and food system transformations should be complementary. The study also suggested that past intervention strategies in food vending in the area of food safety and hygiene practices can be built on for the implementation of the initiatives.

In conclusion, transforming food vending practices to increase the diversity of food groups provisioned and the integrations of fruits and vegetables in meals, involves the integration of practice-elements, interconnection of practices, and interconnections with governing practices. The study identified several key food vending practice-elements and elements of governance that need transforming. Specifically, adjustments in the procurement of raw food materials, food preparation and presentation, storage, and stocking strategies will enable the realization of the initiatives. Furthermore, key governance elements, including monitoring, supervision, coordination, and steering in collaboration with food vending association leaders will facilitate the implementation of the initiatives. Our findings also provide some insights for policymakers to support the improvement of food vending practices. The study recommends further research on understanding consumers’ receptiveness toward an increase in the diversity of foods provisioned by informal food vending.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

KA, MG, and PO conceived and designed the paper and wrote the paper. KA collected and analyzed the data. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The research was funded by Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) as part of Agriculture for Nutrition and Health (A4NH) project under the interdisciplinary project: Food Systems for Healthier Diets (FSHD).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adelekan, I. O.. (2016). Urban African Risk Knowledge, Ibadan City Diagnostic Report, Working Paper, No. 4.

Adeosun, K. P., Greene, M., and Oosterveer, P. (2022a). Urban daily lives and out-of-home food consumption among the urban poor in Nigeria: a practice-based approach. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 32, 479–491. doi: 10.1016/j.spc.2022.04.024

Adeosun, K. P., Greene, M., and Oosterveer, P. (2022b). Informal ready-to-eat food vending: a social practice perspective on urban food provisioning in Nigeria. Food Secur. 14, 763–780. doi: 10.1007/s12571-022-01257-0

Ahlqvist, T., and Rhisiart, M. (2015). Emerging pathways for critical futures research: changing contexts and impacts of social theory. Futures 71, 91–104. doi: 10.1016/j.futures.2015.07.012

Bezares, N., McClain, A. C., Tamez, M., Rodriguez-Orengo, J. F., Tucker, K. L., and Mattei, J. (2023). Consumption of foods away from home is associated with lower diet quality among adults living in Puerto Rico. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 123, 95–108.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2022.06.009

Bibri, S. E., and Krogstie, J. (2019). Generating a vision for smart sustainable cities of the future: a scholarly backcasting approach. Eur. J. Futures Res. 7, 1–20. doi: 10.1186/s40309-019-0157-0

Branca, F., Lartey, A., Oenema, S., Aguayo, V., Stordalen, G. A., Richardson, R., et al. (2019). Transforming the food system to fight non-communicable diseases. BMJ 364:l296. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l296

Castelo, A. F., Schäfer, M., and Silva, M. E. (2021). Food practices as part of daily routines: a conceptual framework for analysing networks of practices. Appetite 157:104978. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2020.104978

Chukuezi, C. O. (2010). Food safety and hygienic practices of street food vendors in Owerri, Nigeria. Stud. Sociol. Sci. 1, 50–57.

Dai, N., Zhong, T., and Scott, S. (2019). From overt opposition to covert cooperation: governance of street food vending in Nanjing, China. Urban Forum 30, 499–518. doi: 10.1007/s12132-019-09367-3

Davies, A. R., and Doyle, R. (2015). Transforming household consumption: from backcasting to home labs experiments. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 105, 425–436. doi: 10.1080/00045608.2014.1000948

Githiri, G., Ngugi, R., Njoroge, P., and Sverdlik, A.. (2016). Nourishing livelihoods: Recognising and supporting food vendors in Nairobi’s informal settlements. IIED Working Paper, IIED, London.

González-González, E., Nogués, S., and Stead, D. (2019). Automated vehicles and the city of tomorrow: a backcasting approach. Cities 94, 153–160. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2019.05.034

Herrero, M., Thornton, P. K., Mason-D’Croz, D., Palmer, J., Benton, T. G., Bodirsky, B. L., et al. (2020). Innovation can accelerate the transition towards a sustainable food system. Nat. Food 1, 266–272. doi: 10.1038/s43016-020-0074-1

Kanatamaturapoj, K., McGreevy, S. R., Thongplew, N., Akitsu, M., Vervoort, J., Mangnus, A., et al. (2022). Constructing practice-oriented futures for sustainable urban food policy in Bangkok. Futures 139:102949. doi: 10.1016/j.futures.2022.102949

Karamba, W. R., Quiñones, E. J., and Winters, P. (2011). Migration and food consumption patterns in Ghana. Food Policy 36, 41–53. doi: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2010.11.003

Kazembe, L. N., Nickanor, N., and Crush, J. (2019). Informalized containment: food markets and the governance of the informal food sector in Windhoek, Namibia. Environ. Urban. 31, 461–480. doi: 10.1177/0956247819867091

Kolady, D. E., Srivastava, S. K., Just, D., and Singh, J. (2020). Food away from home and the reversal of the calorie intake decline in India. Food Secur. 13, 369–384. doi: 10.1007/s12571-020-01107-x

Lee, A. (2016). Affordability of fruits and vegetables and dietary quality worldwide. Lancet Glob. Health 4, e664–e665. doi: 10.1016/s2214-109x(16)30206-6

Leshi, O. O., and Leshi, M. O. (2017). Dietary diversity and nutritional status of street food consumers in Oyo, south western Nigeria. Afr. J. Food Agric. Nutr. Dev. 17, 12889–12903. doi: 10.18697/ajfand.80.15935

Lucan, S. C., Maroko, A. R., Bumol, J., Varona, M., Torrens, L., and Schechter, C. B. (2014). Mobile food vendors in urban neighborhoods–implications for diet and diet-related health by weather and season. Health Place 27, 171–175. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2014.02.009

Mandich, G. (2019). Modes of engagement with the future in everyday life. Time Soc. 29, 681–703. doi: 10.1177/0961463X19883749

Mangnus, A. C., Vervoort, J. M., McGreevy, S. R., Ota, K., Rupprecht, D. D., Oga, M., et al. (2019). New pathways for governing food system transformations: a pluralistic practice-based futures approach using visioning, back-casting, and serious gaming. Ecol. Soc. 24:2. doi: 10.5751/ES-11014-240402

Mattioni, D., Loconto, A. M., and Brunori, G. (2020). Healthy diets and the retail food environment: a sociological approach. Health Place 61:102244. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2019.102244

McKay, F. H., Singh, A., Singh, S., Good, S., and Osborne, R. H. (2016). Street vendors in Patna, India: understanding the socio-economic profile, livelihood and hygiene practices. Food Control 70, 281–285. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2016.05.061

Muyanja, C., Nayiga, L., Brenda, N., and Nasinyama, G. (2011). Practices, knowledge and risk factors of street food vendors in Uganda. Food Control 22, 1551–1558. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2011.01.016

Mwangi, A., Den Hartog, A., Mwadime, R., Van Staveren, W., and Foeken, D. (2002). Do street food vendors sell a sufficient variety of foods for a healthful diet? The case of Nairobi. Food Nutur. Bull. 23, 48–56. doi: 10.1177/156482650202300107

Ogundari, K., Aladejimokun, A. O., and Arifalo, S. F. (2015). Household demand for food away from home (FAFH) in Nigeria: the role of education. J. Dev. Areas 49, 247–262. doi: 10.1353/jda.2015.0004

Oomen, J., Hoffman, J., and Hajer, M. A. (2022). Techniques of futuring: on how imagined futures become socially performative. Eur. J. Soc. Theory 25, 252–270. doi: 10.1177/1368431020988826

Panicker, R., and Priya, R. S. (2020). Paradigms of street food vending in sustainable development–a way forward in Indian context. Cities Health 5, 234–239. doi: 10.1080/23748834.2020.1812333

Piaseu, N., and Mitchell, P. (2004). Household food insecurity among urban poor in Thailand. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 36, 115–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2004.04023.x

Quist, J., Thissen, W., and Vergragt, P. J. (2011). The impact and spin-off of participatory backcasting: from vision to niche. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 78, 883–897. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2011.01.011

Resnick, D., Sivasubramanian, B., Idiong, I. C., Ojo, M. A., and Likita, T. (2019). The enabling environment for informal food traders in Nigeria’s secondary cities. Urban Forum 30, 385–405. doi: 10.1007/s12132-019-09371-7

Ruel, M. T., Minot, N., and Smith, L.. (2004). Pattern and determinant of fruit and vegetable consumption in sub-sahara Africa: A muiltcountry comparism, international food policy resaerch institute, joint FAO/WHO workshop on fruit and vegetable for health 1–3 sept, Kobe, Japan.

Schatzki, T. (2002). The site of the social: A philosophical account of the constitution of social life and change, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Shove, E., Pantzar, M., and Watson, M. (2012). The dynamics of social practice: Everyday life and how it changes. Sage, New York.

Shove, E., Watson, M., and Spurling, N. (2015). Conceptualizing connections: energy demand, infrastructures and social practices. Eur. J. Soc. Theory 18, 274–287. doi: 10.1177/1368431015579964

Sisto, R., Sica, E., and Cappelletti, G. M. (2020). Drafting the strategy for sustainability in universities: a backcasting approach. Sustainability 12:4288. doi: 10.3390/su12104288

Soria-Lara, J. A., Ariza-Álvarez, A., Aguilera-Benavente, F., Cascajo, R., Arce-Ruiz, R. M., López, C., et al. (2021). Participatory visioning for building disruptive future scenarios for transport and land use planning. J. Transp. Geogr. 90:102907. doi: 10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2020.102907

Spurling, N., and McMeekin, A. (2015). “Interventions in practices: sustainable mobility policies in England” in Social practices, interventions and sustainability: Beyond behaviour change. eds. Y. Strengers and C. Maller (London: Routledge)

Steyn, N. P., Mchiza, Z., Hill, J., Davids, Y. D., Venter, I., Hinrichsen, E., et al. (2014). Nutritional contribution of street foods to the diet of people in developing countries: a systematic review. Public Health Nutr. 17, 1363–1374. doi: 10.1017/S1368980013001158

Story, M., Kaphingst, K. M., Robinson-O’Brien, R., and Glanz, R. (2008). Creating healthy food and eating environments: policy and environmental approaches. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2008, 253–272. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090926

Swai, O. A. (2019). Architectural dynamics of street food-vending activities in Dar Es Salaam city Centre, Tanzania. Urban Des. Int. 24, 129–141. doi: 10.1057/s41289-019-00083-9

Tawodzera, G. (2019). The nature and operations of informal food vendors in Cape Town. Urban Forum 30, 443–459. doi: 10.1007/s12132-019-09370-8

Thornton, L. E., Lamb, K. E., and Ball, K. (2013). Employment status, residential and workplace food environments: associations with women's eating behaviours. Health Place 24, 80–89. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2013.08.006

Tsuchiya, C., Amnatsatsue, K., Sirikulchayanonta, C., Kerdmongkol, P., and Nakazawa, M. (2017). Lifestyle-related factors for obesity among community-dwelling adults in Bangkok, Thailand. J. Int. Health 32, 9–16. doi: 10.11197/jaih.32.9

UNDP (2004). Human development report. United Nations Development Programme. Available at: www.hdr.undp.org.

Van der Gaast, K., van Leeuwen, E., and Wertheim-Heck, S. (2022). Sustainability in times of disruption: engaging with near and distant futures in practices of food entrepreneurship. Time Soc. 31, 535–560. doi: 10.1177/0961463X221083184

Vermeulen, S. J., Park, T., Khoury, C. K., and Béné, C. (2020). Changing diets and the transformation of the global food system. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1478, 3–17. doi: 10.1111/nyas.14446

Villman, T. (2021). The preferred futures of a human-centric society: A case of developing a life-event-based visioning approach. Thesis.

Wegerif, M. C. A. (2020). “Informal” food traders and food security: experiences from the Covid-19 response in South Africa. Food Secur. 12, 797–800. doi: 10.1007/s12571-020-01078-z

Welch, D., Mandich, G., and Keller, M. (2020). Futures in practice: regimes of engagement and teleo-affectivity. Cult. Sociol. 14, 438–457. doi: 10.1177/1749975520943167

WHO (2003). Report of a joint WHO/FAO expert consultation, Diet, Nutrition and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

Zhong, T., and Scott, S. (2020). " Informalization" of food vending in China: from a tool for food security to employment promotion. J. Agric. Food Syst. Community Dev. 9, 1–3. doi: 10.5304/jafscd.2020.094.006

Keywords: street food vending, nutrient intake, social practice, future initiatives, urban poor, Nigeria

Citation: Adeosun KP, Greene M and Oosterveer P (2023) Practitioners’ perspectives on improving ready-to-eat food vending in urban Nigeria: a practice-based visioning and back-casting approach. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 7:1160156. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2023.1160156

Edited by:

Hettie Carina Schönfeldt, University of Pretoria, South AfricaReviewed by:

Oluwatosin Leshi, University of Ibadan, NigeriaHenrietta Ene-Obong, University of Calabar, Nigeria

Copyright © 2023 Adeosun, Greene and Oosterveer. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kehinde Paul Adeosun, a2VoaW5kZS5hZGVvc3VuQHd1ci5ubA==

Kehinde Paul Adeosun

Kehinde Paul Adeosun Mary Greene1

Mary Greene1 Peter Oosterveer

Peter Oosterveer