Abstract

Different authors from academia and social movements point to agroecology as a path to food sovereignty and as a way out of multiple social-ecological crises. Peasant feminism (feminismo campesino) informs the daily practice of women, and has contributed to broaden the meanings of food sovereignty as a political framework. Vinculación y Desarrollo Agroecológico en Café (VIDA) is a Mexican coffee growers’ organization that is centrally guided by principles of agroecology, food sovereignty, and peasant feminism. A transdisciplinary study held with VIDA members shows how food sovereignty is based on more dimensions than the official ones. In this paper, we use the Mexican art of embroidery as an integrating metaphor to analyze how female coffee growers’ practices around integral health, food gathering, and bartering contribute to food sovereignty. Our intention is also to analyze how these activities expand from the family unit to the territory, as well as from human to more than human beings. Based on their agroecological knowledge and practice, VIDA’s feminist peasant women invite us to consider agroecology and food sovereignty as key dimensions of Earth stewardship.

1 Introduction

Climate change, the dominant agricultural model and its drive for hyperproductivity, the energy crisis and the precariousness of labor are serious problems of the current food system (Giraldo, 2022). Against this backdrop, various scholars support the peasant, black, feminist and indigenous movements (Vivas, 2012; Nyeléni, 2014; LVC, 2015, 2021; Shiva, 2016; Montoto, 2017; Montano Morales, 2021)1 that point to agroecology as a path toward food sovereignty as a way out of the current food system problems and other social-ecological crises.

Food sovereignty is a political framework proposed by the international peasant organization La Via Campesina (LVC). It emerged in 1996 as a response to the concept of food security (LVC, 2015) put forward by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Based on notions of poverty and scarcity, food security is denounced by Colombian indigenous movements as an exercise of welfarism and power over biocultural territories (Montano Morales, 2021). In contrast, food sovereignty offers a new paradigm with the strategic objective of creating alternatives to neoliberal policies based on local cultural, political, and economical systems (Nyeléni, 2014).

The food sovereignty framework recognizes an agriculture linked to the territory, oriented to local and national markets, and that takes life as a central concern. It promotes autonomy by valuing peasant and indigenous’ ways of production and management of the territory, common goods, knowledge, and organizational forms (LVC, 2016). Agroecology and food sovereignty advocate for political equality, which implies an end to the various forms of physical and structural violence to which women are subjected (Nyeléni, 2014; LVC, 2015). Thus, women’s and children’s rights are key issues for the current debate on food sovereignty (Nyeléni, 2017).

Since 1996, organized women have promoted a strong gender perspective in the initiatives and decision making within LVC, so that their rights are recognized as central to the food sovereignty of the household and the community (LVC, 2021). Regarding contributions to the concept, it was women who raised the banner of food sovereignty as a right (Montoto, 2017), pointed to the dimension of human health (Vivas, 2012), and argued that peasants and indigenous peoples have the right to produce their own food in their territory, recognizing their role as guardians of seeds (LVC, 2021). Through the construction of peasant and popular feminism, they integrated gender issues, the full demand for human rights, actions to combat violence in rural areas and gender equity within peasant organizations (LVC, 2021).

The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Peasants and Other People Working in Rural Areas (UNDROP) was published in 2020. It is a legal document that recognizes the identity linked to the ways of producing, being and relating with people and nature (LVC, 2021). This document focuses on all rights anchored in food sovereignty and proposes feminist agrarian reform. In the construction of this declaration, peasant women uncompromisingly defended collective and organizational rights, seeds, land and territory, the right to ancestral knowledge and wisdom, the defense of biodiversity and the participation of women and youth in related issues (LVC, 2021).

Despite the mentioned contributions to feminist struggles, the final text of the UNDROP does not directly address several key gender equality issues. As Claeys and Edelman (2020) point out, the document does not discuss the right of women to inherit land; equality in family relations; sexual and reproductive health and rights; the disproportionate burden of reproductive and productive work; and gender identity and discrimination. Furthermore, it does not directly mention patriarchy as a source of structural oppression, which debilitates its political nature. These limitations are mainly due to the “counter-mobilization” by conservative government alliances and supportive non-governmental actors to oppose the development of feminist human rights policies (Claeys and Edelman, 2020).

Considering that the concept of food sovereignty is still under construction, it can benefit from numerous experiences that integrate it, and critically reflect on it to generate contributions that strengthen it. This has been the case of the contributions made by the Andean indigenous peoples who, based on the paradigm of abundance and liberation of Mother Earth, join the proposal of food sovereignty by conceptualizing food autonomy (Montano Morales, 2021).

The perspectives of peasant and popular feminism that have contributed to broaden the meanings of food sovereignty as a political framework also constitute the daily life of peasant women in several localities around the word. In Mexico, female coffee growers of the organization Vinculación y Desarrollo Agroecológico en Café (VIDA), with whom we collaborated in this study, also show us that food sovereignty is made up of dimensions that are less discussed in official documents, such as spirituality and the emotions around food and territory. Their ways of life based on agroecology, the ethic of care and alternative economies are expressed through diverse practices and daily art such as embroidery. In this article, we take embroidered napkins as an integrating metaphor. During our meetings, embroidered napkins were present in all the kitchens and territories visited. The napkins are a symbol of knowledge and experiences shared by women and among women, they accompany the family when they gather to share food, at the table and in the field, they keep the corn tortillas warm. Through the strength of the material and symbolic presence of the napkins, in this article, the colorful threads of the Mexican ancestral art of embroidery help us to show how the knowledge and practices of the peasant women of VIDA are interwoven with food sovereignty.

The purpose of this paper is to expand previous reflections on how integral health, food gathering, and bartering expand the concept of food sovereignty (Pontes et al., 2021, 2023a,b). We are especially interested in how feminist peasant movements from the Global South contribute to this discussion, as it can directly impact the lives of those people involved in such reflexive and practical process. In sum, this article demonstrates how integral health, food gathering and bartering contribute significantly to food sovereignty as a political framework. These contributions emerge from the experiences and knowledge of peasant women of the organization VIDA, who have embroidered napkins of food sovereignty and shared their words with dignity, love, and transformative strength (Figure 1).

Figure 1

The colored threads that make up the food sovereignty napkin. Art by Florencia Rothschild and Thelma Pontes composed of napkins embroidered by Clara Palma (green thread: woman enjoying the territory), Irma Moreno (pink thread: the flower of life), Gisela Illescas (purple thread: strength of a woman), and Briseida Venegas (brown thread: barter), all peasant feminist coffee-growing women.

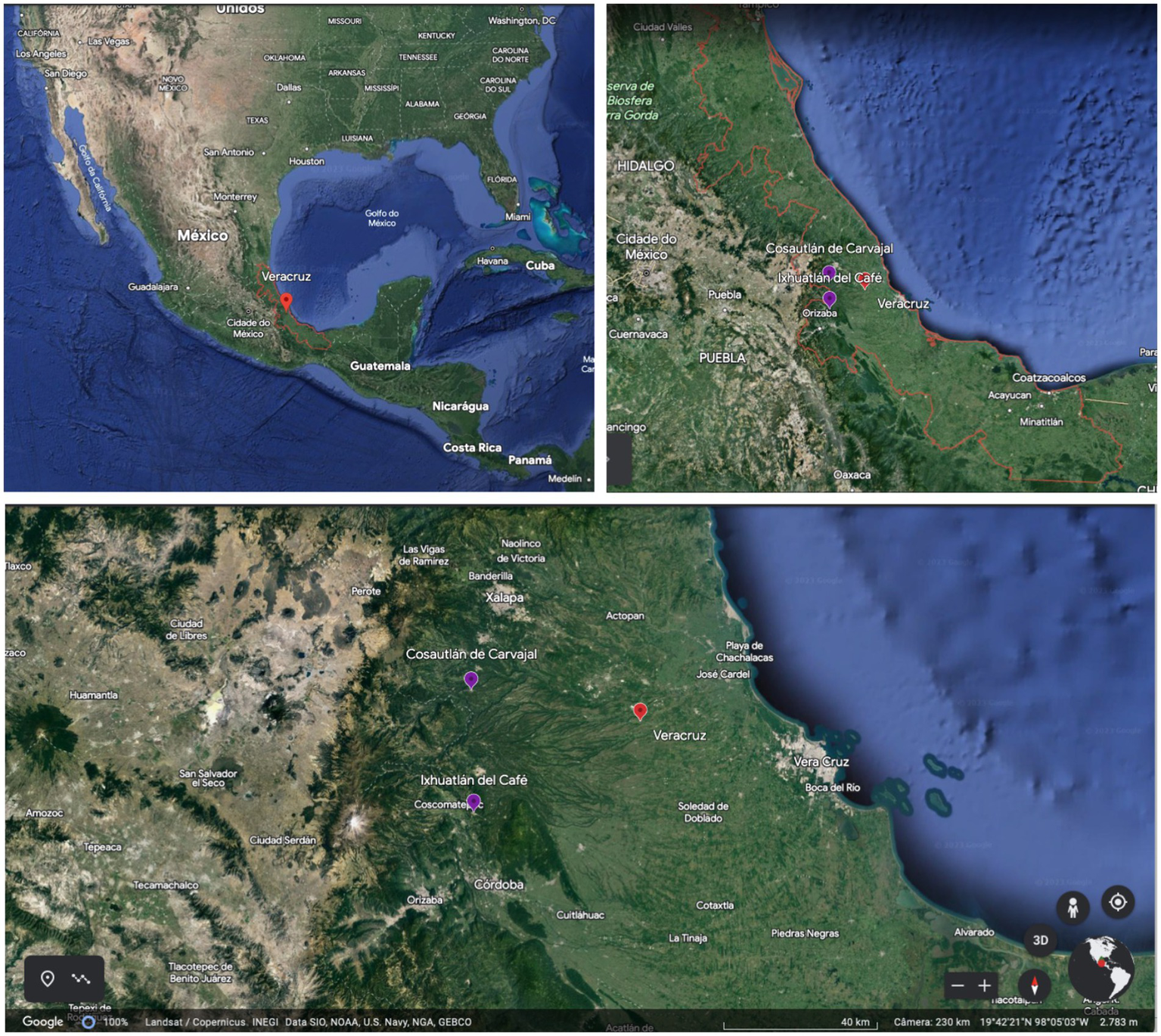

2 Stages of our transdisciplinary research

The study on which this paper is based was carried out in Ixhuatlán del Café and Cosautlán de Carvajal, in the center of the state of Veracruz, Mexico (Figure 2). These localities were selected for the larger number of participants and their higher level of participation in the processes organized by VIDA. The edible coffee plantations2 maintained by women of VIDA are located in areas of mountain cloud forest, which offer favorable conditions for the production of shade coffee, with diverse flora and fauna species (Figure 3). Reciprocally, agroecological coffee farming contributes to the recovery and conservation of the benefits provided by this ecosystem (Severiano Hernández, 2021).

Figure 2

Geographic location of the municipalities of Ixhuatlán del Café and Cosautlán de Carvajal, Veracruz, Mexico. Own elaboration using Google Earth images.

Figure 3

Edible coffee plantations in the communities of Gusmantla and Ixcatla, Ixhuatlán del Café, Veracruz, Mexico.

Vinculación y Desarrollo Agroecológico en Café is a 30-year-old organization that has women coffee growers in charge of various processes. VIDA3 is made up of 800 families and has a large participation of women in its cooperative called Campesinos en la Lucha Agraria (Farmers in Agrarian Struggle). The women were the driving force behind the transition to agroecology in 1999. Five years later they obtained organic production certification and began exporting high quality coffee.

The transdisciplinary research (Cuéllar-Padilla and Calle-Collado, 2011; Chilisa, 2017; Merçon, 2021, 2022) we conducted puts the voice of coffee women at the center of epistemological production. The research was conducted between 2020 and 2023. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, virtual meetings were initiated to establish the research team and the co-design of the different stages of the process. In 2020, the concept and practice of food sovereignty was discussed in more depth by VIDA and the first article was collaboratively generated (Pontes et al., 2021). The first face-to-face meetings were held in 2021 (Figure 4), in compliance with security protocols and with a small number of people.

Figure 4

Meetings with women coffee growers’ peasant feminists organized in VIDA, in Ixhuatlán del Café and Cosautlán de Carvajal, Veracruz, Mexico, in 2021.

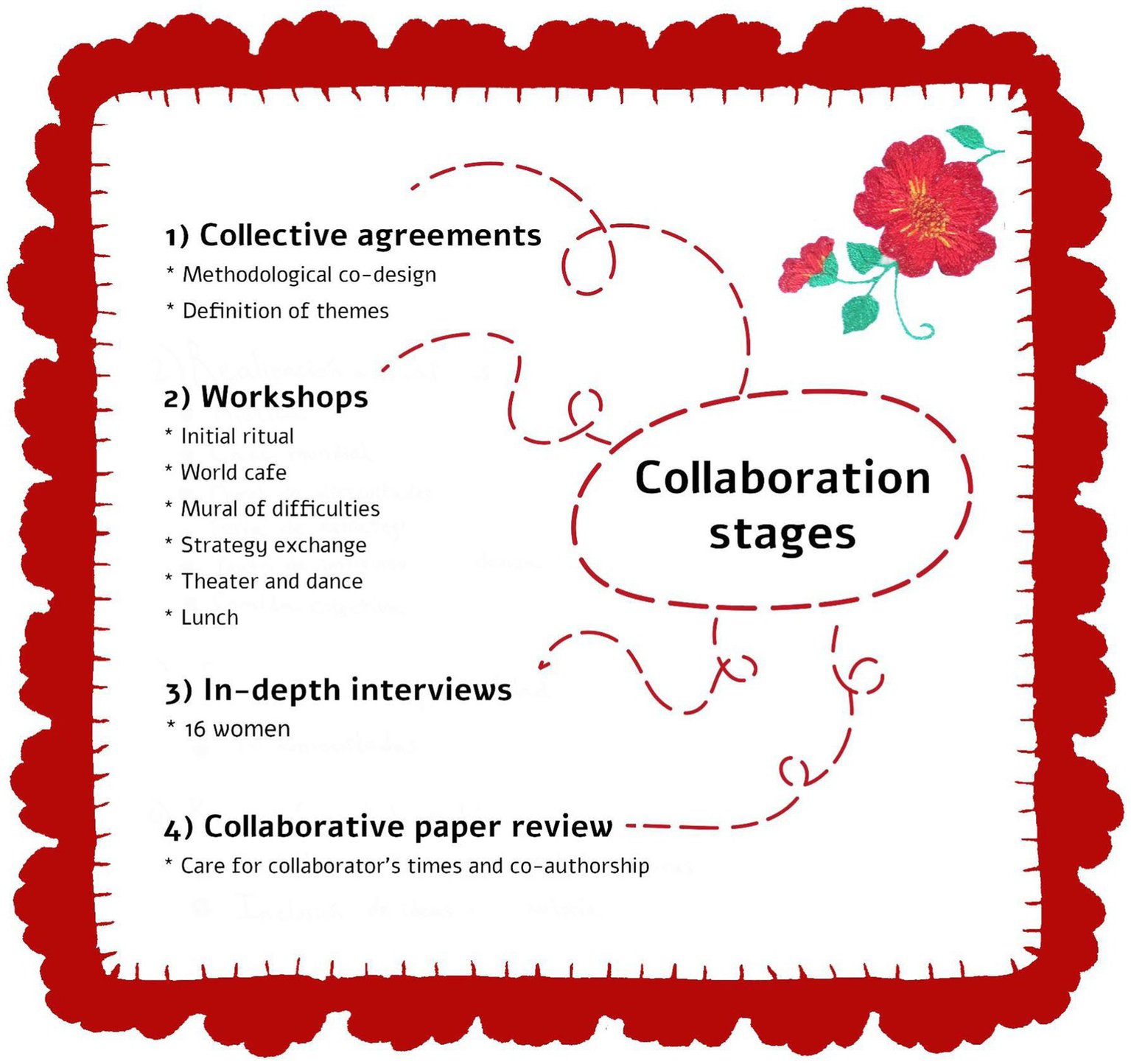

The collaboration took place in four stages (Figure 5). In the first stage we reached agreements around the research team, forms of exchange, and the elaboration of the collaborative texts that would emanate from this research. In the second stage, we conducted two participatory workshops based on the dynamics of World Cafe (Dawkins and Solomon, 2017; O’Connor and Cotrel-Gibbons, 2017). In the workshop, the themes of each table were identified: integral health, food gathering and bartering. Subsequently, three questions were formulated to guide the dialogues on each topic: (1) What is it? How is it practiced? Who does it? Where and when is it done?; (2) Is it linked to food sovereignty? How?; (3) What helps and what hinders this practice? In the third stage, 16 in-depth interviews were conducted around the same themes of integral health, food gathering and bartering to learn about: how these practices are learned and transmitted; the effects of the pandemic; the importance of these practices and their relationship with the coffee plantation, gender and rural–urban links; and the identification of plants.

Figure 5

Stages of transdisciplinary research and co-production of this study. Own elaboration with art by Florencia Rothschild from a napkin embroidered by Floriberta Jiménez Cruz, herbalist and coffee grower of VIDA, from the community of Guzmantla in Ixhuatlán del Café, Veracruz, Mexico.

The narratives derived from the workshops and interviews were systematized for the creation of critical explanations (Holliday, 2006) and discourse analysis (Santander, 2011). This type of analysis conceives communication events and verbal interactions, such as the women narratives, as a social practice linked to their cultural and historical conditions of life.

Eleven women between the ages of 27 and 64 years participated in the collaboration, all of them members of the peasant feminist civil organization VIDA.4 In addition to growing and commercializing coffee, they make handicrafts and flower arrangements, produce anthurium flowers in greenhouses and in 2022 inaugurated the first Femcafé coffee shop in Ixhuatlán del Café. They cultivate their edible coffee plantations, their milpas, medicinal gardens for herbal medicine, and generate by-products from native bees and maintain five collective brands: Femcafé5 (agroecological and specialty coffee), Mujer que Sana (herbal medicine and traditional medicine), Mujeres de la Niebla (traditional cuisine), Familias de la Niebla (peasant tourism), and Bordadoras de Vida (embroidery). In this paper, we included the real names and ages of VIDA women as we present their ideas. This was done with their prior and informed consent.

3 Embroidering food sovereignty

In the following sections, we invite readers to embroider, with the women coffee growers, a napkin for food sovereignty tortillas. With the pink thread we will embroider ideas around integral health care, with the green thread the gathering of food and medicinal plants, with the brown thread the barter basket and in the last section of the discussion, with the purple thread, we present a definition of peasant and popular feminism as lived and practiced by the women coffee growers of VIDA (Figure 4). Before exploring the threads of our food sovereignty napkin, we briefly present a reflection on food sovereignty: at the beginning of each workshop, we cocreated a “mystique”6 and answered what food sovereignty is for me to value and recognize the multiple ways in which knowledge is expressed (Figure 6) (Pimbert, 2017).

Figure 6

The colored threads representing the knowledge of women coffee growers on integral health, food gathering and bartering as contributions to food sovereignty. Photo-embroidery by Thelma Pontes.

3.1 Embroidering hands: women’s expressions about food sovereignty

For me food sovereignty is to sow a seed of life and hope, a seed that can be reborn in our hearts, to feed our people, to feed our hope, a seed that gives us vitality, that gives us life, but also a seed that will produce more seeds of conscience to continue sowing our food and harvesting and cooking it, eating and above all sustaining us in the field (Clara Palma, 64 years old).

For many peasant communities, the foundation of their worldviews “resides in the necessary balance between nature, the cosmos, and human beings” (LVC, 2015, p. 16), recognizing that humans are part of nature and the cosmos. As an expression of their spiritual connection with their land and the web of life, the peasant women of VIDA began each meeting with an offering in which each participant placed what she considered to be of greatest social-spiritual value in the center of a circle. The things they presented as an offering ranged from food, medicinal plants, representations of the four elements, as well as objects used for food gathering, production, and cooking. They offered food, seeds, especially coffee beans which are “part of our identity, what makes us be, what makes us feel” (Gisela Illescas, 43 years old), a “molcajete,” a “guaje,” a “machete,”7 a flower syrup and many medicinal plants.

As they offered the symbolic elements at the center of the circle, the women expressed their feelings about food sovereignty (Table 1). Emotions generated in the mystique promote the expression of convictions and values held and reinforce group cohesion (Lara Junior, 2010). In addition, the atmosphere generated at this moment allows for the encounter between the sacred and social causes, connecting two fundamental elements: the culture itself and the community environment, attributing new meanings and senses to the things that come from nature and with which women live and work every day (Lara Junior, 2010). A sense of belonging and collective identity is also reinforced through the mystique (Lara Junior, 2010). For coffee grower women, the mystique also has the following meanings:

Table 1

| Relationship | Meaning | Level | Quotes or Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Barter (Tracaleo or Change) | Exchange between objects, food, or services that have approximate values1 | Intrafamily, between families and between communities | “In tracala, sometimes, it may be that mine is worth more than yours, so you have to give me a difference (the edging) (…) for me it was always like that part of saying well, you do not always have to change all for money, there are other ways” (Denisse García, 37 years old). |

| Cambalache | Exchange between objects or food of the same value | Intrafamily and between families | “Changing one thing for another and that it is worth the same, the same as mine costs, yours costs” (Denisse García, 37 years old). |

| Faena | Contribute some work that is of benefit to the entire community | Between families | “It is something voluntary that is like an obligation (…), it is like a contribution of work to the community, for the improvement of the community,” (Irma). “It is our turn once a year, my husband is never there, so if I have to contribute one hundred pesos so that someone else can represent my husband” (Adriana Quiroz, 35 years old). |

| Mano Vuelta or días vueltos | Support with some seasonal activity | Between families | “For example, I go with a neighbor who maybe has a cornfield or a farm, I help him one day and between the two of us and then we come to my farm, that is the hand turned, and money does not necessarily intervene there” (Irma). |

| Invite/Share/Give | Gift of objects, services, or food | Intrafamily and between families | “My mother, who would go with my aunt or with close relatives and well, they would do just those food changes” (Denisse García, 37 years old). “Then my aunt would say that you do not have to stay owing anything, it is as if they bring you, you have to pay, but it is a civic duty, and it is like your feelings, like the need to pay for work or the help they give you” (Adriana Quiroz, 35 years old). |

| Share tasks and activities | Distribution of tasks or activities | Intrafamily | For example, in the kitchen, for a better distribution of work where, while some prepare the dish, others wash the dishes. |

| The traje or traje party | Distribution of dishes and food to live together | Intrafamily, between families or between communities. | For example, when they are going to have a party, they agree on what each person or family is going to bring to live together. |

| Food cooperation | Distribution of food prepared to live together | Between communities | “In Ixcatla, for the festival of San José, the community itself helps to live together, because many people from the communities come, so they give them food, they help each other” (Irais Venegas, 27 years old). |

| Solidarity support | Material or service support to individuals or families | Between families | For example, some people get together to support a person or family that needs help, be it material or service, especially if there are sick people. |

Relationships based on the gift in the coffee communities of Ixhuatlán del Café and Cosautlán de Carvajal, Mexico.

1The value is established according to the reasonable prices of the same products in the market.

The mystique is a way through which spirituality manifests itself. It is also a way of connecting with oneself and womanhood. For us, peasant women, there is a very close relationship between being a woman, food, and food sovereignty. Mother Earth is a woman, at the same time she is the womb that feeds us and she is also part of us. All the elements that are put in the mystique have to do with, from our worldview, with the four elements: water, air, fire, and earth. The fruits symbolize our work with our hands on the earth, the food, and there is also the part of health and other elements of art, such as embroidery. That is to say that it is not something rigid, that is why the altars are so different. Each alter is different, because of what we can offer, we have harvested or we have brought and it is also to share (Gisela Illescas, 43 years old).

Broadening political and epistemological horizons, in the sections that follow, we will seek to contribute to the discussions that expand the concept of food sovereignty. To broaden the concept of food sovereignty and produce a transformation in the field of rights, Micarelli (2018) argues that it is necessary to unlearn hegemonic conceptions of sovereignty and theorize beyond the notion of nation-state. Historically, the concept of sovereignty was born in the Middle Ages in the context of absolute monarchies, in which sovereignty was exercised by the King. In its etymology, the word sovereignty comes from the Latin word superanus, which refers to someone who has authority above all others.8 For Foucault (1996) sovereign power implies obedience to the king, who exercises the power to dispose of the lives of individuals. It is a form of power over lives, both to make die or let live, through control over bodies and space, organizing fixed ties and obligations that bind people to a particular place. In face of these and other historic meanings associated with the notion of sovereignty, Micarelli (2018) proposes that we disconnect the concept of sovereignty from its Eurocentric roots and question the assumptions of an idea of power modeled in terms of the monarch or the state to give rise to plural ways of understanding, feeling and relating to the world. In contrast, she argues that sovereignty is a social creation, aimed at a social, political and cultural order. For example, according to indigenous peoples of the Colombian Amazon, the notion of sovereignty is interpreted as care, protection and responsibility, rather than authority, control and ownership. In these logics, neither land, food, nor common goods belong to human beings; on the contrary, people belong to them, in relations of reciprocity that unite communities and territories. In this living tissue of relationships, nature is recognized as a subject of rights, natural goods are valued by criteria far beyond the economic, and collective work is what makes common life possible (Micarelli, 2018).

In a conversation about the notion of sovereignty, Gisela Illescas, a feminist peasant woman and co-author of this article, argued that this notion has for her a deep meaning of connection, recognition, freedom and unity. “Connection with our own body-territory; recognition of our place in the body-territory; being free from oppressions and neocolonialism (including academic) and unity with ourselves and with everything, including non-human energies.” By re-signifying the notion of sovereignty, Gisela Illescas reaffirms the meanings proposed by LVC (2015) around the autonomy of peoples and the necessary union between humans and nature: “Sovereignty obviously comes from a colonial concept, but when it is embraced to talk about food sovereignty it is aimed precisely at freedom, autonomy, connection, and the recognition of the common. When I speak of unity, I am referring to the community and to the connection with Mother Earth” (Gisela Illescas, 43 years old).

Considering the current political dispute around the notions of food sovereignty and food security, it is important to strengthen the struggle of peasant peoples for the meanings and uses of the concept of food sovereignty that they have been building for almost 40 years. It is not the purpose of this article to deepen this discussion, but we believe that it may be of interest to peasant and other social movements to rethink the use of the term sovereignty in their worthy struggles, as it may be appropriate to decolonize the term “food sovereignty,” considering that many indigenous peoples and peasant communities teach us that the relationship built around food is one of interdependence, cooperation, solidarity, reciprocity, collective autonomy and not sovereignty in its dominant political sense.

In counterpoint to the sovereign State power, a recurrent aspect of indigenous struggles in Mexico refers to the defense of local autonomy (Cerda García, 2011). Two key examples of indigenous autonomy in Mexico include: (i) the autonomous governance of the Caracoles Zapatista,9 who do not cease to recognize rights and obligations before the State but redefine this relationship from the capacity and right to govern themselves (Cerda García, 2011); and (ii) the autonomy exercised by the Purepecha people in the municipality of Cherán K’eri,10 where in 2011, the community decided to stop illegal logging of its forests and reorganize local political institutions, with the expulsion of political parties and the creation of a communal government structure (Ramos, 2018).

We can also think of the food issue in terms of food autonomy, the right and the power of each citizen to decide autonomously about what to grow and eat, respecting the different ways of being. In Colombia and Peru, indigenous peoples and peasants’ communities defend food autonomy in relation to sowing and eating, looking inward, retaking ancestral knowledge, reciprocity, and mutual nurturing for the care of life (Montano Morales, 2021). Food autonomy is conceptualized as “legacy of socio-cultural, environmental, economic and spiritual wisdom and practices that have been woven over time and are raised in a cosmogonic relationship according to the biological diversity and culture of a territory” (Montano Morales, 2021, p. 117).

One of the main struggles for food sovereignty and autonomy corresponds to the resistance against the hoarding of the commons. These struggles allow us to understand that what is at stake are not simply resources, but the meanings attributed by indigenous peoples and peasant communities to these (non) common goods (De la Cadena, 2015). Many of these meanings are based on relationships of care and reciprocity with Mother Earth, which makes possible the coexistence in the web of life, identity, good living, and dignity (Cariño Trujillo, 2019).

Various practices that contribute to expand the concept of food sovereignty by women coffee growers were strengthened throughout the pandemic (Pontes et al., 2023b). They refer to the care for physical, emotional, mental, and spiritual health, food gathering, bartering, and peasant feminism sorority as alternatives based on interdependence instead of competition, on reciprocity and gift, autonomy and collective work. They challenge hegemonic visions of development, politics and economy based solely on money and profit. From these practices, women model reality, strengthening and broadening food sovereignty in its concept and practice.

3.2 The pink thread: integral health

Being able to decide about one’s body is part of health. However, due to lack of experience or lack of knowledge, sometimes we allow external agents to decide for us (Irma Moreno, 56 years old).

The women coffee growers of VIDA define integral health as a process of balance between: “heart, body–mind, and nature” (Denisse García, 37 years old). Health is “having access to information, it is self-care, it is letting go of what depresses, eliminating fears, it is having harmony, peace, balance of emotions, of thoughts” (Irma Moreno, 56 years old), and it is also feeling “love for ourselves, as you cannot transmit it to others if you do not love your own self” (Gisela Illescas, 43 years old).

Integral health is “being able to decide about your body, about the way you heal yourself” (Irma), it is based on self-care and collective care, through harmonious relationships with the environment. Plants are its strong allies, used for the maintenance of a healthy diet and medicines for physical, spiritual, and emotional benefits. Health care depends on innumerable factors, many of which are connected to the customs and food traditions of each person and place. According to the women coffee growers, being healthy should be our priority as human beings, because if we are healthy, in harmony with everything around us, this is transmitted to the family, to the community, to the territory.

Healthy eating inspires them to take care of the first territory: the body in harmony with nature, providing physical and spiritual satisfaction. According to this approach, the body is one with the territory (body-territory), and is conceived as a physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual entity. When coffee women take care of their integral health through traditional knowledge about plants, emotions, spirituality, and the human body, they affirm counter-hegemonic ways of life in connection with their territories, and the construction of peasant feminism from the grassroots. In the last section of the discussion, we present with the purple thread a definition of peasant and popular feminism as lived and practiced by the women coffee growers of VIDA. These views around the body-territory are also present in the Mayan and Shinka women of Guatemala (Cabnal, 2010; De la Vega, 2019) and the fisherwomen from Oaxaca (Espinal and Azcona, 2020),

In this napkin of food sovereignty, the coffee-growing women embroider integral health with the pink thread of care for the body, mind, and spirituality. Reciprocity, love, and care for Mother Earth are also part of a healthy life. Moreover, VIDA women claim that integral health is a path that is necessarily shared with others, nourishing, and being nourished by the collective.

3.2.1 The core of collective health care

We have to be strong and continue to fight. That is a very serious thing to say. We now see that those people we admire are getting old and sick, you say “hey, what have we fought so hard for?” (Gisela Illescas, 43 yerars old).

The existence, vitality, and perpetuation of peasant women’s worldview, practices, and values depend on complex processes of knowledge transmission and construction. One of the most valuable contributions of VIDA peasant women refers to how the network of integral health care is constituted, and how transmission of ancestral knowledge is intertwined with contemporary practices and knowledge, leading to its current cultural expression.

Throughout life, learning about health care is done “as a whole, in several links: my family, my mother, other women I have lived with and my personal experience” (Denisse García, 37 years old). A practice that they consider very important is “listening to one’s own body” (Denisse García, 37 years old). Most traditional knowledge related to healing processes is applied out of necessity, mainly when they get sick in a more severe way or when they have small children. Because “if you do not have money, I’m going to give you a cup of tea (…) the economy has a lot to do with it” (Adriana Quiroz, 35 years old). Healing is a process of straight connection with the plants and the knowledge of women. To heal is a practice that women learn from their mothers “who are always attentive to the look on their faces” (Adriana Quiroz, 35 years old), from their grandmothers or mothers-in-law “who investigate and see the faces of the children” (Irma Moreno, 56 years old), and “from their great-grandmothers, with the curative plants of the coffee plantation” (Irais Venegas, 27 years old), from the backyard and the forest (Table 2).

Table 2

Food sovereignty…

|

| ¨Food sovereignty comes from all the mothers, we, who help each other (…). Feeding ourselves and feeding our children too, so that they can move forward" (Maria del Rosario, 40 years old). ¨Food sovereignty is what people have been accustomed to planting for hundreds of years and how they want to eat it. That makes us resilient, that makes me feel secure in my territory and I don't have to go begging in the big cities ̈ (Clara Palma, 64 years old). |

|

| ¨We decide what we eat, when we eat it, how we prepare it and (…) this implies the recovery of knowledge of how they did it before" (Denisse García, 37 years old). ¨It is like an inheritance that comes from my family. I have a grandmother who is a healer (…) she taught me how to make different types of tea (…) so for me it is more than anything else, it is a family inheritance" (Lucía Moreno, 29 years old). ¨We barter what we have and we don't need cash to buy food. From bartering we bring everything we don't have, and we barter or sell what we have" (Esperanza Reynoso, 57 years old). |

|

| ¨It is that reminder of the importance of eating to be able to live. So every time we have the opportunity to decide what we want to eat, knowing that food not only feeds our body, as it also feeds our soul (…). To be able to eat with family, with friends (…), to enjoy, to laugh, to live together (…). It makes us think a lot… For those of us who have children or family, what we want for them, (…) all that memory of your grandmothers, your grandfathers, the crops, but also those hopes for the future, where we want to go" (Gisela Illescas, 43 years old). |

|

| ¨It is health and family well-being, so as long as we are all well at home and we have health and healthy food, it is a nice thing, it is the good life¨ (Lucía Méndez, 31 years old). |

|

| ¨We women become guardians of the seeds, of the cornfield, of the orchard, of whatever comes. Yes, we women are guardians, we do not allow it to be lost (…) in food sovereignty we dignify the path of other people in this struggle for food¨ (Denisse García, 37 years old). ¨It is to feed and it is food. It is knowledge about food and how to pass it on to other generations (…) you preserve the seeds and this is like a generation, a family, (…) if you keep giving to the family you keep giving the seed, it is conservation, it is life. If you don't have seed, you don't have life¨ (Adriana Quiroz, 35 years old). |

|

| ¨In this time of crisis, food sovereignty encompasses the economy. The diversity of food we grow and have is beautiful. It has allowed us to resist this pandemic (…). We have a lot of food to eat (…), to barter. We have it because we grow it" (Clara Palma, 64 years old). ¨It reflects dignity, this part of rebelling, that is, I don't have to do what capitalism says, but what we decide as peoples (…) Food sovereignty cannot be done individually, you have to be together with other people¨ (Denisse García, 37 years old). ¨It makes me think a lot about the whole production, in the kitchen and in the commercial relations as well, to whom our products go, where they travel (…) I think about them, in their forests (…), sovereignty is like that connection that unites people" (Gisela Illescas, 43 years old). |

VIDA women coffee growers’ expressions on food sovereignty.

In recent years, they have paid special attention to collective practices of mental and emotional health, focusing on individual and collective self-care based on reciprocity. Just as for the indigenous Mayan women of Quintana Roo (Arrese Alcalá, 2021), the women coffee growers of VIDA know that maintaining these practices is crucial for the sustainability of the organizations and to break with the oppressions of patriarchal and capitalist structures, which are based on false individuality, and the cycle of exploitation of bodies through unpaid work. To set limits to these structures and cultivate collective care involves affection, enjoyment, and pleasure (Arrese Alcalá, 2021).

Being a part of a women’s support network has shown to be key for their emotional and mental health, because, according to them, health is a collective matter; being well and looking after others is a type of political action (Arrese Alcalá, 2021). The network gives them support, allow them to listen to each other, and make them feel safe and confident, “if I talk about it with my friends, I feel better. They encourage me and tell me: ‘keep going, we are here, and we need you’” (Asunción Hernández, 42 years old), “you feel that someone else loves you and you reinforce that love for yourself” (Adriana Quiroz, 35 years old). Through mutual care, they strengthen immediate ties, frame their position as social actors, and their sense of belonging to the community (Arrese Alcalá, 2021).

Women coffee growers have learned throughout this health care journey that the interconnection between physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual health is crucial (Box 1). Women feel spiritually healthier when they listen to their intuition, seek help from healers whenever they need it, and maintain some protective practices, mainly with their children, when they are babies and when they go to the fields. In the territory, they maintain respect for certain sacred spaces or for places where things that cannot be explained happen. Every year, on the first Friday of March, they perform a flower harvesting ritual and prepare a compound called Marzo. This is the first medicine they use for healing, in the face of various ailments, mainly stomach related ones.

BOX 1 Gisela Illescas (43 years old) and Irma Moreno’s (56 years old) accounts of their personal experiences of self-care with spiritual health and reconnection with spirituality.

Gisela says that her great-grandmothers were midwives, and one of her grandmothers and many uncles are healers. As a child, she talked to the angels, but her very Catholic grandmother kept her away from the visions. Until she became seriously ill and sought for conventional medicine aid, reconnection with spirituality, with meditation practices, yoga and rituals with Ayahuasca.

I am in this process of reconnecting with myself, it has been very beautiful, it has been very painful, it has been the most difficult but at the same time it is very important to make big changes, then, in a meditation I could see what terrified me, what I had hidden from myself all my life (…). The first days of May we did an ayahuasca ceremony, a beautiful message came from “grandma,” through a friend, who told me: we have to warm the heart of humanity, the heart of humanity is very cold, and we need to warm it. So I think this is a good point to talk about health, to feel again, to remember why we are here, what we are here for, to build different dreams, to enjoy, not competitiveness, productivity, but to feel, to feel alive, to feel connected, to have hope, to have faith, to believe that everything is going to be fine, and to flow with the process (Gisela Illescas, 43 years old).

Irma relates that her experience comes from her childhood when she helped and observed how an aunt did the cures, she was learning throughout her life and with the work in the organization many things about herbalism. Some years ago, when she was 48 years old, she took a course in traditional Mexican medicine with a witchdoctor, which removed the stigma of witchcraft. ̈When I took this course, I saw that witchcraft is wonderful, because it is for the purpose of healing people, for the family, for the community, for care, for protection. Connecting with spiritual guides that help us to redirect our paths and also to maintain contact with mother earth, which is what gives us power, through plants, nature, through the rain, through the sun, and that all of this is healing” (Irma). In this workshop she learned how to unblock energy points, to balance energy and do cleansing with herbs and the egg. On how to direct her inner divinity with the help of spirit guides for cures. It also made her understand historically and politically how important it is to fight to maintain this knowledge and the traditions of the midwives, healers and bonesetters.

Irma says that all of us have this capacity and that you can develop it. For this you have to have discipline and go into meditation. You have to think positive thoughts, not have addictions, learn to turn to your inner child and maintain a good diet, with food that comes from your agro-ecological farm or harvesting and reduce the consumption of meat, mainly from animals that are raised in violent conditions.

Spirituality does not apply only to us, the people in communities. It is that link with the physical body, with the mental body, with the energetic body, and with the spiritual body of all people. So, when we talk about food sovereignty, we refer to how we can reconnect ourselves, in our own body, in our territory and as humanity. And I think this is where all these expressions of how we have been taking care of food fit in, but also how women have been a fundamental part of all of this. So much for the conservation of seeds, of biodiversity, but also for the whole of the food part. The consumption of food that gives life, of food that nourishes, of food that heals, of food that connects (Gisela Illescas, 43 years old).

From a feminist perspective, women’s spirituality can be defined as the ability to assert and affirm themselves in other ways to improve each other’s lives (Heath, 2006). The spirituality of women coffee growers is centered on relationships; firstly, with their bodies: looking, feeling, listening to intuition, valuing their personal experiences; secondly, in interpersonal relationships, being in a network with other women, caring and healing collectively; and thirdly, maintaining and strengthening the relationship of reciprocity with nature, with the land.

For the coffee grower women of VIDA in Veracruz, the Mayan women of K-luumil X’koóleloób in Quintana Roo (Arrese Alcalá, 2021) and the Mayan and Xinka women of Guatemala (Cabnal, 2010), the defense of their territory begins with the defense of the physical, mental, and spiritual body. It also involves naming, recognizing, and legitimizing the knowledge, resistance and wisdom of ancestral women, all beings, and the territory (Cabnal, 2010). In sacred spaces, they evoke voices, silences, pain, and joy in a liberating action that energetically connects them with the cosmos. Based on peasant feminism, they create libertarian symbols for a transgressive practice, integrating a new imaginary of spirituality (Cabnal, 2010). Their practices and knowledge of care and self-care are reflected in the quality of the relationship they maintain with the environment and are also political tools to defend life, linking a sense of identity to sustainable and reciprocal agro-ecological practices and food sovereignty. In capitalist societies where rest and non-productive practices are often rejected or not valued, care and self-care are political tools that allow women to have health and strength to remain in the struggle for their rights.

To better interpret socio-cultural realities and how these factors disproportionately influence the health of black, indigenous and rural women, it is important to critically study theoretical frameworks that focus on race, class, and gender (Heath, 2006). From the perspective of VIDA women’s relational ontology (Escobar, 2011), whereby humans and extra-humans develop relationships of care and reciprocity, other meanings are given to health and illness. For them, life experiences, human bonds and relationships with the environment are key elements to be considered in situations of illnesses; and explanations based exclusively on organic or psychological factors are insufficient (Remorini et al., 2018). The environment can be both the cause and the solution to a problem. Alongside physical symptoms, emotional issues, energetic and spiritual connections play a central role in the cause and choice of treatment.

3.3 The green thread: food and medicinal plant gathering

Throughout evolution, food gathering has been crucial for humans. The gathering of wild plants (Milton, 1993) has long played an important role, complementing the diet of the agricultural societies of Mesoamerica (McClung de Tapia et al., 2014). In previous work, we presented a list of spaces where women of VIDA practice food gathering, the seasons and the types of collected food, and some care practices (Pontes et al., 2023a). We also highlighted the political, social, economic, emotional, and spiritual importance of this practice, which has reciprocity with the Mother Earth as central.

For agroecology and food sovereignty, food gathering is linked to place-based dietary traditions, from women’s decision-making in the household to the preparation and consumption of food (Morgan and Trubek, 2020). These processes are governed by their ways of relating to the territory and the recognition that the right to food goes beyond the human, thus implying extended forms of care and Earth stewardship (Micarelli, 2020).

The above connections are also reflected in the rescue, sowing, and gathering of native seeds, edible resources, and medicinal plants, in conserving native vegetation, eating well and valuing local and healthy food. They also entail spirituality for “food, as the sacred, penetrates our being” (Gisela Illescas, 43 years old) and taking care of spaces and animals, like the “little bees that take care of the common wellbeing” (Irma Moreno, 56 years old). Decisions made by the women about what they are going to sow and gather to feed the family and to cure foster their independence from the pharmaceutical industry and rescues their autonomy in the healing process: “we have within our reach what we need to maintain our health” (Denisse García, 37 years old).

Gathering provides them with access to diverse foods and medicines, which are healthy not only because of their nutritional properties, but also due to links to their family history, local customs, and traditional knowledge. Moreover, seeds are often conserved through generations, to care for the territory and cultural identity through flavors, textures and smells of the foods gathered and sown: “We drink purple atole.11 It satisfies all the symbolic senses linked to it” (Nelly Sánchez, 32 years old).

Irma tells us about the strong and beautiful connection between health, fruits, medicinal plants, and the seasons of the year. The spring plants, which “are going to hydrate you, to prevent from dehydration when the summer comes.” The autumn and winter plants “will help you prevent respiratory diseases and then there are many other fruits, herbs that provide you with warmth. The winter herbs are the same ones that midwives recommend when you are in labor, so that your body recovers all that energy, that warmth that it lost during the birth” (Irma Moreno, 56 years old).

Gathering from an integral health perspective also means going to the spaces of life, coexistence, work, and individual and collective leisure, and among these places, the coffee plantation has a very important place. In the edible coffee plantation, women gather many medicinal plants and wild foods, and reconnect with the knowledge of their ancestors. “Within the coffee plantation there are spaces that we like. When we go to cut coffee, we do not eat just anywhere (…). We have a harmonious connection between us and the coffee plantation” (Clara Palma, 64 years old). Gisela Illescas adds: “The coffee plantation for me represents all that: the history, the food, the abundance, the roots, and also the health, the roots, the connection.” It is also where the women meditate and look for the necessary energy to continue, to have self-confidence, “think positive from my privileges and my context, to be grateful and to change my way of thinking” (Denisse García, 37 years old). “So those of us who are in the field are happy, we live in glory and sometimes we do not know it, because we do not value our territory” (Lucia Méndez, 31 years old). “In the coffee plantation near where I live, there are some very big trees. I call one in particular grandmother. That is where I like to go when I want to meditate (…), that type of connection also represents going to the coffee plantation, or when you are a child, it is to go to play, to eat, to have fun, to discover, to feel alive” (Gisela Illescas, 43 years old).

The “March compound” made of citric flowers or “azahares” is a product that symbolizes the reciprocal connection between the women coffee growers, the coffee plantation, the medicinal plants and Mother Earth. This is commonly prepared by the women and is the first medicine they use for the cure of any illness, physical or emotional (Box 2).

BOX 2 Lucía Méndez’s (31 years old) account of the preparation and medicine of the

According to Lucía Méndez, the first Friday of March “which is a mystical day, a day when many doors open, it is a special day, when all the plants, all the beings, all the stars, at that moment are working, it is a day when the plants bring out their greatest power.” At dawn they collect the flowers of all the fruit trees (azahares) and the medicinal plants that you have in your coffee plantation and in your backyard “on this day, in this season, there are a thousand and one azares and all the medicinal plants that you know.” All these flowers and plants are put to macerate in aguardiente, in a glass bottle with a lid, for 40 days, in a dark place. After these 40 days, it is ready for consumption. It can be taken in various ways, depending on the body’s needs and age, from a small glass, or a spoonful to 20 drops in a glass of water. It has its benefits: depression, stress, pains of all kinds, colic pains, stomach pains, even if you cannot sleep, even if you cannot sleep it helps you, because as the azares are relaxing then it helps you a lot, it really cures you of everything.”

In sum, food and medicinal plant gathering is an important component of culturally appropriate food sources, that invites us to think about non-capitalist economies for which money is not pivotal. The act of gathering also entails collective care that unites and strengthens coffee grower women in their feminist peasant struggle for autonomy over their food and health. Finally, gathering also implies a deep act of reciprocity and gratitude for the gifts of Mother Earth.

3.4 The brown thread: the barter basket

This is a movement against capitalism, it is a movement that the poor are making, it is their movement for the resistance of the people, to save their seeds, their ways of life, it is a movement to survive in time, with our culture, with other ways of life, with what we are. We have to strengthen this movement, and it has to be much bigger every day, and to combine it with everyone, with the young people (Clara Palma, 64 years old).

The community experiences of Mesoamerican and South American indigenous peoples demonstrate that the ethic of gift and solidarity is essential for humans (Arai, 2020). All people, at some point in history, benefit from mutual support and reciprocity systems (Pardo et al., 2019). These are always present in interactions between humans and extra-human entities, as Barabas (2010) argues in her study of Mesoamerican cultures. Clara Palma, one of the founders of VIDA, confirms that idea: “In different places, in different cultures, people have subsisted through more than 500 years of conquest. How do they continue in their villages? Through what? Barter may seem to be a small contribution, but behind it there are many, many things, much bigger and much deeper” (Clara Palma, 64 years old).

To expand non- or post-capitalist experiences, it is important to make them visible, research them, and learn about their ethical values, forms of operation, and factors that motivate communities to continue to nourish them (Acosta and Guijarro, 2018). In this section, we attempt to highlight these aspects to analyze the practice of bartering carried out by women coffee growers in their territory and how this practice contributes to food sovereignty.

Within the activities based on the ethics of gift12 (Barabas, 2010) among coffee-growing families in the mountains of Veracruz, women highlighted that they practice different activities related to bartering (Table 1). The reciprocity system maintained by VIDA women in their communities in Veracruz includes mutual support for multiple tasks, for community self-organization, and allows the exchange of what is needed, especially in times of great difficulty and crises. Among these practices, tracala, exchange or barter, are practiced at all levels: between members of the family unit or between families, at the community level and between communities, in the tianguis (popular street market).

Everything is exchanged” (Denisse García, 37 years old): from gathered and grown food and medicines to services. In the practice of barter, women are the ones who exchange food to ensure that the family fulfills its needs. The main exchanged products are fruits and coffee, which are mainly exchanged for seasonal fruits, vegetables, creole beans and maize.

According to the coffee grower women from VIDA, barter is important for food sovereignty for three main reasons: (i) Diet diversification: “It allows a diversified diet with what grows in other regions. We can then have things that do not grow here” (Denisse García, 37 years old); (ii) Social support and care: “Exchanging is sharing” (Esperanza Reynoso, 57 years old). “The most important thing is sharing food as a sacred act, because a lot of what is bartered is from gathering, and it is how you are willing to share life when it comes to bartering.” (Gisela Illescas, 43 years old). “Knowing that we all have needs, and that we can all help each other, that is an advantage” (Lucía Méndez, 31 years old), the “feeling of collective care” (Denisse García, 37 years old). “Normally when you bring a lot, you tend to give it away to other much more vulnerable women, so that is also this gesture of generosity that also motivates me a lot, impresses me and I think that the cooperation between people and the love that it shows, that is invaluable” (Gisela Illescas, 43 years old); and (iii) Economic complementation: Barter renders value the women’s work and supports the household economy with what they save. According to women from VIDA, they manage to save 600–800 Mexican pesos per week through bartering.

The peasant economy is sustained by alternative practices, including the maintenance of ancestral economic practices. The recognition of women’s work supports their position as economic subjects, also in the case of barter. Barter and other alternative economic practices reposition the patriarchal biases of the economy and agricultural production and offer a political contribution for the construction of sustainable food systems and counter-hegemonic economies (LVC, 2010; Escobar, 2011). As women state: Barter “values my effort” (Lucía Méndez, 31 years old) and shows that “(…) money is not essential, but rather, what is essential is to give value and dignify the work of peasant men and women (…) because you put love into it, you put passion in it, you worked it with love” (Denisse García, 37 years old). Through barter one “learns to value, question, and be more aware of what you really need” (Irma). “The most important thing is that I can help here at home, because, well, I also put part of my work into what is food” (Esperanza Reynoso, 57 years old). It is also “to support each other and allow that the children see that everything in this life costs. It helps to make them value what they sow, what they love” (Lucía Méndez, 31 years old).

Margarita Flores (59 years old) teaches us the symbolic importance of barter as an instrument of food sovereignty and peasant feminist struggle. In her dignified rebellion to maintain the practice and knowledge of barter in her family, she sees it as a means to have access to local, diverse, healthy and nutritious food (Box 3). Barter also represents other forms of articulation between productive and reproductive work. Coffee grower women, by collectively participating in this activity, contribute to the cohesion of the social fabric, to individual and collective growth, providing learning, autonomy, and sociability (Nobre, 2015). In the studied communities, both the contemporary reproduction of barter and the practices around integral health appear as important political instruments promoted by organized women, who demonstrate how non-hegemonic social and environmental relationships are enacted and nurtured.

BOX 3 Story about the barter of Margarita Flores (59 years old), co-founder of VIDA.

“I got married for 49 years, I already missed that here (going to barter with his mother), and because I would see here with my husband and say: My God, here every day eggs, beans, chopped, all the days! (…) With my husband, well, he told him: I want to go to Cosco (Coscomatepec) to change! what are you going to go for? People are going to say that they cannot keep you! (…) I mean, no old man, look, my mom taught me, we bring potatoes, squash, chayotes… my mom even changed meat or pork rinds. (…) You are not going!

One day I already had my little girl, Rosario was little and I was pregnant with another girl, (…), Sunday came, and I start roasting coffee (…), I say: No! Now if I’m not going to obey him, I’m going to go, get ready, I’ll tell my mother-in-law: (…) Doña Matilde! Do you take care of me my Charito? Right now I’m going to Cosco and I’ll be right back! (…) I take my bag, my petaca (basket) and my coffee. I changed, it was around 12 and I was already here, back. When she arrives (…) and she tells me (Madam rest in peace!): Did you bring all that? How soon did you take the money? No! just my ticket and that changed everything!

I started taking out my things, (…), I’m going to make bean chilatole for my husband too, I’ll make him mole from fat beans, those tender ones. And he arrives and you say: Where did you get fat beans? I went to Costco! (…) He got angry, he says: I do not want to eat! (…). He did not eat, but the next day (…) I make his beans again, and I put his bean cubes, he already had lunch, it arrived in the afternoon, he already ate! I made him some chips, out of what he brought, he already ate!

Well, about a fortnight later, I’m leaving again, and the more he saw how I brought things and all that. Later he tells me: No, well, yes it’s true, you are right, well, I’m going to plant plantains and you are going to change (…), and every 8 days I would go, he would accompany me and we would even bring corn, beans, good of everything that is up there (Citlaltépetl Volcano), and I tell him: And what you earn in the week, well, for a little piece of meat, bread, milk for our children. He already looks! We have corn, beans, we have potatoes, everything. He says: No, yes, you are right!”

Barter favors the creation of bonds of friendship and the street market or “tianguis” becomes a meeting space, where links are made and created between “people who share this idea of believing that we can change some situations in our country, simple people, with values” (Irma Moreno, 56 years old). In addition to admiration and respect for the older women who keep the practice alive, VIDA women express their hope for those who are learning to barter or “tracalear.” Solidarity bonds are created around food between peasant communities, around this form of collective organization, the roots and dignity of being peasants, maintaining the spirit of community and the traditions they inherited from their ancestors.

According to peasant feminist women from VIDA, barter has as main values: (i) Trust in each other’s word: People talk honestly, negotiate and “opportunities are only given once” (Adriana Quiroz, 35 years old); (ii) Humility and justice: Both when assessing the quality of the products and setting the barter cost; (iii) Solidarity: between more experienced women who share their knowledge with those who are learning to barter; among women who go together to the tianguis; and among those who exchange products. Bartering requires diverse values, knowledge, and skills (Table 3). Women reproduce and reinforce social and economic ties, relationships of trust (the word, clients, quality and agroecological products, and friendship ties), socializing relationships (ability to relate, to negotiate), and promote values such as reciprocity, loyalty, honesty, humility, in opposition to capitalist competitive values (Moctezuma Pérez et al., 2021).

Table 3

| Required | Knowledge, willingness, develop aptitude and negotiation skills and have self-confidence. So that you can offer and value your products and those that are going to be exchanged, so that you feel good and safe at the time of making the negotiation and so that reciprocity prevails. |

| Learned | Relate commercially and socially with the clients and with the people who live in the tianguis, to remove the shame and grief. ¨There are fellows that I would not know if it were not through barter, I already know many people from the communities above, they especially go to my post, they even speak to me by name¨ (Esperanza Reynoso, 57 years old). To eat and try different foods, as well as exchange knowledge and recipes. |

| Strengthened | Bond of trust and loyalty between women. Link between generations when children and young people are involved in barter. Respect for the knowledge of the elderly and the strengthening of leadership and autonomy. |

Diverse aptitudes and abilities developed by the women coffee growers of VIDA with the practice of barter.

Vinculación y Desarrollo Agroecológico en Café women comment that many people feel ashamed of bartering, mainly young people. However, during the COVID-19 pandemic, young people began to use their virtual contact networks to barter through Facebook groups, showing that peasant youth can contribute to the development of solutions to challenges faced by their communities (Pontes et al., 2023b). This and other actions support and adds to the struggle of rural youth around the world (Nyeléni, 2021).

Bartering also symbolizes the importance of collectively occupying public spaces. The street is claimed as a space for creativity, emancipation, and democracy (Moctezuma Pérez et al., 2021). In this occupation, there have been conflicts of interest between VIDA women themselves and local political authorities, which indicates how this form of bottom-up social activity is a target of constant dispute and negotiation (Moctezuma Pérez et al., 2021).

Furthermore, the practice of barter creates lasting obligations and mutual recognition (Moctezuma Pérez et al., 2021), promotes collective care, cooperation, trust, loyalty, and solidarity between people. The barter market is a historical, political and biocultural process (Moctezuma Pérez et al., 2021), where cultural continuity and transformations occur in regard to identity, knowledge, values, and the territory. “It is a big movement that we must cultivate and that we must motivate others to do. That’s what we have to tell city people, even if at the moment it seems romantic” (Clara Palma, 64 years old). The women coffee growers expand the space of the tianguis as a meeting place, for community and intergenerational ties, and for the transmission of knowledge within their territory and beyond.

Participating in barter and other economic processes based on solidarity promotes autonomy (SOF, 2015). From a feminist economic perspective, barter contributes to rethinking unpaid productive work, and the reproduction of care that generates savings in the family and community nucleus. It also contributes to food sovereignty and to economic systems based on the values of solidarity, reciprocity, and justice toward the sustainability of human and extra-human life.

3.5 The connecting purple thread: peasant and popular feminism

We, women, have no time, no land, no water (Irma Moreno, 56 years old).

Peasant and popular feminism, as it has been conceived and practiced by the women of VIDA, is in line with feminist theorizations put forward by the women organized in LVC and by the women of various Latin American peasant movements. In Gisela Illescas’ words:

Peasant and popular feminism recognizes how the peasantry live, in ways that centrally involve the family and the community. It is a political stance in which women occupy decision-making spaces both at the family and community levels, and it recognizes all the inequality gaps. It intersects with different feminisms, for example with decolonial feminism, for the spiritual dimension; with ecofeminism, for the connection with the Earth and it also connects with food sovereignty. It is putting life, collective care, spirituality, community organization, the body-Earth-territory connection and shared knowledge at the center. It is not a simple definition but something that crosses many of these spheres. In VIDA we have put it into practice by designing different tools to facilitate the participation of women, as in the solidarity savings group, the work with herbal medicine, with backyard gardens and food sovereignty, in youth leadership. This feminism is the dignification of peasant life, the recognition of how peasant life is reconstructed, recognizing that we exist, that we have been and that we will continue to be here, in contact with the Earth, despite the colonialist invasion that transformed our lives. Peasant and popular feminism promotes strategies of community care, such as the reciprocity of barter that contributes to a dignified life, and the balance with the environment that also contributes to creating dignified livable lives for the peasant families (Gisela Illescas, 43 years old).

The women coffee growers confirm that in respect to health “in different ways, both (women and men) have been violated, and all these violations of rights have made us see men and women as enemies, and not as partners, as comrades, as a team” (Irma Moreno, 56 years old). According to them, Mexican peasant women are vulnerable due to cultural and political systems such as patriarchy and capitalism, which are responsible for the sexual division of labor. Sexism made men vulnerable for since they are children, they are judged and punished; they learn not to externalize their emotions, their illnesses or whatever is associated with their fragility.

Women are the ones who wake up earlier and go to bed later (Gisela Illescas, 43 years old). Women repress many feelings and emotions so that they are not judged. They learn how to take care of others, but do not learn self-care practices, nor to respect the right to “do nothing.” They socialize less and have fewer leisure opportunities. They are socially conditioned, since they were girls, as the only ones responsible for the care of others and motherhood, a type of work that is romanticized, made invisible, not recognized, or valued. “I think that our gender condition decreases our health, and added to that, all the intersection of gender, race, class, ethnicity, and everything else you want to add, in short” (Gisela Illescas, 43 years old).

Clara Palma, as an adult of 64 years of age, recounts that, throughout life, peasant women are subjected to too much workload inside and outside the home. Since childhood, women learn to give up their own care to care for everyone else: “women are compared to the Virgin Mary, who gives up everything,” reaching the point of feeling guilty if they get sick. Added to this, multiple gestations and breast feeding without specific care and accompaniment contribute to the fact that “our health is lessened.” All these factors, according to Clara, make it very difficult for rural women to empower themselves and feel like subjects of rights in health care. Therefore, a key challenge is to change perceptions around women and promote self-respect and women’s rights. As an organization, they have significantly learned about collective ways to change this oppressive reality (Box 4).

BOX 4 Narrative of Margarita Flores (59 years old), Irma Moreno (56 years old) and Clara Palma (64 years old) on how comprehensive health care practices began within VIDA.

Margarita relates that in the early years of the organization none of them worried much about health care, they were young and what they worried about was work at home, in the fields and with productive projects. But that today she feels that if from the beginning they already had the rescue of herbal knowledge and the collective health care that they have today, she feels that she would not have accumulated so many health problems. For this reason, VIDA has organized workshops on caring for reproductive and sexual health, self-esteem, human rights, food, and since the 2000s on herbal medicine and botanical walks, which has contributed to motivate and awaken more women. Youth for the importance of health care.

Irma and Clara tell what this experience of starting health care as an organization was like. They found that women, due to having many children and poor nutrition, had various diseases in the womb and that, in the 90s, with the coffee crisis, men began to emigrate to other cities or countries and when they returned, wives contracted sexually transmitted diseases. Due to machismo, they could not question, nor demand the use of a condom. In addition to the stress to which they were subjected by being left alone for up to 10 years, with their young daughters, in charge of the elderly and the coffee plot, which awaited them various diseases, mainly in the reproductive system. So Clara, Irma and Águeda began to promote work with women to raise awareness, self-care and to look for alternatives and ways to support these women, “so that’s how we trained ourselves to be able to follow up and accompany women who had this type of situation, so that they could get ahead together” (Irma Moreno, 56 years old).

They learned from a gynecologist how to do and read the Pap smear, and they sought treatment with medicinal plants and only sent serious cases to the health center. They also investigated the main illnesses of the children and concluded that they got sick more from respiratory problems, because they did not have adequate clothing and footwear for winter or because of the conditions of the houses, so they began to make syrups to cough. They sought to exchange experiences with midwives, healers from the community itself, they were invited to herbalist workshops, health courses and, with a group of women in the Sierra de los Tuxtlas, who were dedicated to the preparation of medicines based on plants, they learned to do the botanical walks and the preparations. They also shared experiences with another women’s organization in the State of Morelos, Clara went to Guatemala to the University of San Carlos and they also did exchanges with the University of Chapingo “and this is how we gradually enriched ourselves, all this knowledge of plants, not only with external people, but from the community” (Irma Moreno, 56 years old).

Care work reveals social inequalities, relations of exploitation, and domination (Molinier and Paperman, 2020). The stories and desires of coffee farming women provide numerous elements for academic feminists to think of a care society in which key ethical dimensions guide policies that consider vulnerabilities from the bottom up (Molinier and Paperman, 2020). When you are born economically impoverished, your fundamental concern is to eat. If you do not have food, if you do not have enough to feed your family, the emotional stress you suffer because of that is terrible (Gisela). Mexican rural women have been historically deprived of the right to land property and to decide over land management and common goods (García, 2001; Cuaquentzi Pineda, 2007), which makes them more vulnerable in health care. “That is why food and care are fundamental issues. We must not struggle alone; it is a very heavy burden” (Gisela Illescas, 43 years old).

Within the thought of peasant feminism, coffee-growing women consider it important for health care to recognize the feminine and masculine energy that exists within oneself, seeking to balance it, love it, and not judge it. They argue that it is necessary to continue to change how people think within the families so that everyone is co-responsible for care work. To transform patriarchal cultural impositions, it is key to empower girls so that they do not reproduce roles of vulnerability.

At the community and organizational level, they consider it important to actively participate in collective work such as health brigades, promote care spaces that take emotional health in consideration, share specific self-care practices for each phase of life, including moments of rest and leisure, and valuing the care work done by women. In the box Gisela Illescas (43 years old) explains some of these practices and how care and self-care are at the core of peasant and popular feminism (Box 5). They consider it important to maintain a feminist movement that promotes change in the family nucleus and that, based on the creation and maintenance of a solidarity networks between women and other genders, strengthen health: “between us, we have built a family and it gives us that closeness and that confidence to ask, to talk, to guide you” (Denisse García, 37 years old). For women coffee growers, good care occurs collectively, with autonomy, with equality, in the daily practices of self-care and care for the family, the community, the territory, and Mother Earth.

BOX 5 Narrative of Gisela Illescas (43 years old) about care and self-care of coffee grower women’s popular and peasant feminism.

Care is made tangible in women’s circles. These are women’s gatherings for emotional health, spaces for each woman to focus on herself, on her self-care, especially emotional, spiritual and physical health. This also implies the appropriation of common spaces within the communities for women’s healing. We had to break many taboos that there were no spaces where women gathered to heal themselves and take those spaces, make use of them for such a beautiful activity as self-care. We have also carried out different strategies for the care of the body, for example, rural yoga, where in addition to having yoga exercises, we also did all the work of reflection within the women, about care, in addition to bringing women together. We also manage the funds that are designated for this, so that there is also a budget for these activities.

Regarding patriarchal inequalities in access to land, we have promoted the recognition in the families, that the women coffee growers are also the owners of the land. We created Femcafé brand, which arose precisely to support the women who were not the owners of the land and to ensure that a percentage of the harvest, which is produced by the women, could be commercialized directly, so that the percentage of the harvest that the family produces is negotiated by each woman. She thus has the right to commercialize it and to receive the price for her product and this ensures that she can make decisions about this income.

Decision-making positions within the cooperative have been led by women, and have also included the participation of young people. For example, those who lead the cafeteria are now young women and the strengthening of the youth network. Economic empowerment with women and children groups in solidarity savings also underpin these processes.

Care and self-care refer to how women occupy spaces in their own life, their family life, community life, organizational life, not only working but also taking care of themselves through resting. For example, in the last women’s circle we went to the beach—it was fascinating! (Gisela Illescas, 43 years old).

Another fundamental aspect of peasant feminism is related to collective and community work. In the communities, there is no individual leadership but collective leadership, where women share problems and inequalities, but also build transformations and hope in the collective. Peasant feminism is to think of each woman as part of a community.

The experience of women coffee growers contributes to think about collective strategies for the defense of common goods and life as important tools to politicize care, breaking gender roles and taking as a starting point that everyone can position themselves and taking responsibility in their processes (Molinier and Paperman, 2020). A key goal is to integrate care in our society as a widely shared practice, where the values of all and everyone are balanced to make ethically valid choices (Mol, 2008).

The practice of care and intuitive action also implies collaborations with extra-humans and their inclusion in the construction collective care (Rico, 2022). That places the question of reciprocity at the center of thinking and living carefully in a complex network that sustains life (De La Bellacasa, 2017). The knowledge and practices of women are key to the set of relationships that entail the care of the land, the reproduction of collective life, and the territory (Rico, 2022). Collective care is not limited to the human dimensions, breaking androcentric, capitalist, and patriarchal hierarchies. From an ontology produced from their peasant and feminist perspective, coffee-growing women construct daily care connections between their own body (physical, emotional, mental, and spiritual), their family, community, and territorial landscape. By placing care at the center of their relationships, they invite us to think about agri-food systems and food sovereignty from these other relationships of interdependence and reciprocity.

4 Conclusion

The concept of food sovereignty is plural and reflects the multiplicity of meanings and relationships between communities, food, and their food systems (Micarelli, 2020). This notion is still under construction and for this reason it is important to integrate contributions from diverse social groups, especially those who have been historically marginalized. Peasant women of the South have long been excluded from dominant debates and decision-making processes. This study shows how their understandings and commitments with collective life greatly contribute to broaden conceptions, values, and practices around food sovereignty. The particular contributions from feminist peasant women from VIDA point to integral health care, food and medicinal plant gathering, and bartering as crucial practices through which food sovereignty and political-economic autonomy are reinforced.