- College of Animal Science and Technology, Henan University of Science and Technology, Luoyang, China

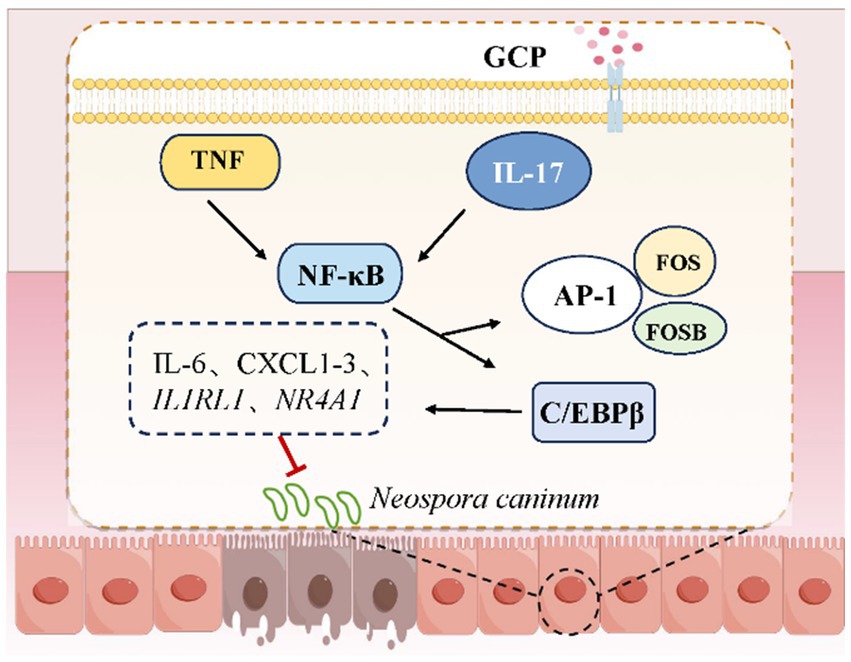

Intestinal epithelial cell (IEC) damage is a crucial event in pathogen-induced intestinal inflammation and systemic pathological responses, and their functional integrity directly affects animal health. This study used bovine intestinal epithelial cells (BIECs-21) and mouse models to examine the protective effects of Glycyrrhiza polysaccharide (GCP) against Neospora caninum (NC)-induced IEC damage and investigate its underlying mechanisms. In vitro, BIECs-21 were infected with NC to establish an intestinal epithelial injury model. In vitro experiments revealed that GCP pretreatment effectively inhibited NC infection-induced decreases in cell viability and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release, preserving intestinal epithelial homeostasis. Transcriptomic analysis results showed that NC infection activated the interleukin (IL)-17 and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) signaling pathways, increasing the expression of chemokines (CXCL1/2/3) and inflammatory genes (FOSB). In contrast, GCP inhibited the expression of transcription factors CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein β (C/EBPβ) and FOS, reduced pro-inflammatory factors (e.g., IL-6, IL1RAP), and mitigated excessive inflammatory responses. In vivo experiments confirmed that low-dose GCP intervention significantly reduced intestinal hemorrhage and edema, decreased parasite loads in intestinal and cerebral tissues of infected mice, and suppressed protein expression of IL-17RA, TNF-α, p-C/EBPβ and p-NF-κB in intestinal tissues. These findings demonstrate that GCP mitigates NC-induced IEC injury by modulating intestinal immune homeostasis through the C/EBPβ/IL-17/TNF signaling pathway, thus establishing a theoretical basis for developing natural therapeutics against pathogen-induced gut damage.

1 Introduction

The intestine is not only a vital organ for nutrient digestion and absorption but also the largest immune organ in the body, performing essential roles in immune barrier maintenance and systemic physiological regulation (1, 2). Thus, ensuring animal intestinal health is one of the key links in safeguarding the healthy development of the livestock industry. Intestinal epithelial cell (IEC), the primary barrier against exogenous pathogens, maintain intestinal homeostasis through tight junction complexes, mucus layers, and antimicrobial peptide secretion systems (3). However, the intestine is susceptible to invasion by pathogens including bacteria, viruses, and parasites, resulting in compromised barrier integrity and systemic immune dysregulation (4).

Neospora caninum (NC) infection begins with IEC invasion and intracellular proliferation, essential steps for systemic dissemination. However, the endogenous defense mechanisms of IECs against NC remain inadequately characterized. Improving intestinal health is a crucial strategy to inhibit intracellular pathogen proliferation and prevent infection progression (5–7). Thus, understanding IEC defense mechanisms and identifying natural compounds that enhance resistance to intracellular pathogens are important for improving livestock productivity and public health security. Although human infections remain undocumented, anti-NC antibodies have been detected in humans (8, 9), and transplacental transmission has been demonstrated in primate models (Macaca mulatta) (10, 11), indicating potential zoonotic risks.

Glycyrrhiza polysaccharide (GCP), a bioactive compound extracted from the traditional Chinese herb licorice, demonstrates immunomodulatory, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and gut microbiota-regulating properties (12, 13). It decreases intestinal permeability and serum levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1, IL-6, TNF-α) while increasing anti-inflammatory IL-10, thus ameliorating murine colitis (14). Furthermore, GCP modulates gut microbiota composition by enhancing beneficial bacterial growth and inhibiting pathogenic species (15, 16). However, the role of GCP in regulating IEC-intrinsic defense mechanisms against NC infection remains unexplored.

This study used BIECs-21 to assess NC-induced cellular damage and the protective effects of GCP. Transcriptomic profiling was used to elucidate underlying mechanisms, with in vivo experiments validating the findings.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Cell culture and treatment

BIECs-21, previously immortalized by our laboratory (17), and Vero cells (African green monkey kidney epithelium, kindly provided by Prof. Lei He, Henan University of Science and Technology) were utilized. NC tachyzoites were obtained from Prof. Qun Liu at China Agricultural University.

BIECs-21 were maintained in DMEM (Gibco, USA) supplemented with 10% FBS (Cegrogen, Germany) and 500 μg/mL G418 (Beyotime, China) at 37 °C under 5% CO₂. Vero cells were cultured in DMEM with 10% FBS for NC propagation. Infection models were established by inoculating BIECs-21 with NC tachyzoites at a 3:1 parasite-to-host cell ratio. For pretreatment experiments, BIECs-21 were incubated with the optimal dose of GCP (1,000 μg/mL, Supplementary Figure 1) for 12 h prior to NC exposure.

2.2 Cell viability assay

BIECs-21 were seeded in 96-well plates and divided into four groups: control (C), GCP-treated (GCP), NC-infected (NC), GCP-pretreated + NC-infected (GNC). After 12 h GCP incubation and 4 h NC infection (MOI = 3:1), cell viability was assessed using CCK-8 (Solarbio, China). Following reagent addition (10 μL CCK-8 + 90 μL DMEM), plates were incubated at 37 °C for 1.5 h. The absorbance of the supernatant was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader (Thermo, USA).

2.3 Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release

BIECs-21 cells were seeded in a 96-well plate and the lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) activity in the culture supernatant was quantified using a Lactate Dehydrogenase Assay Kit (Nanjing Jiancheng, China). After incubation at 37 °C for 1 h, the absorbance of the supernatant was measured at 490 nm to assess membrane integrity.

2.4 Transcriptomic profiling

Total RNA from four experimental groups (C, GCP, NC, GNC) was extracted with TRIzol (Ambion, USA). RNA libraries were prepared using NEBNext Ultra II reagents (New England Biolabs) and sequenced on Illumina NovaSeq 6,000 (150-bp paired-end) by Personalbio (Shanghai, China). Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified with |log₂FC| > 1 and p < 0.05. Functional enrichment analyses were performed using topGO (v2.40.0) for Gene Ontology and ClusterProfiler (v3.16.1) for KEGG pathways.

2.5 Quantitative PCR

Total RNA was extracted from cells or tissues using TRIzol (Ambion). Specific primers were designed and synthesized by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China), and the primer sequences can be found in the Supplementary Table 1. cDNA was synthesized using a reverse transcription kit (Vazyme, China). SYBR Green-based qPCR (Vazyme, China) was conducted on a Bio-Rad system(Bio-Rad, USA) with β-actin as endogenous control. Relative expression was calculated via 2^(-ΔΔCt) method.

2.6 Animal experimentation

Fifty female Kunming mice (6 ~ 8 weeks old) were housed under controlled conditions (20 ~ 24 °C, 40 ~ 70% humidity, 12 h light/dark cycle) with ad libitum access to food and water. Mice were randomized into five groups (n = 10/group): control (no treatment), NC-infected (NC), low-dose GCP (100 mg/kg) + NC infected (NC + L), medium-dose GCP (200 mg/kg) + NC infected (NC + M), High-dose GCP (400 mg/kg) + NC infected (NC + H). GCP was administered via drinking water for 25 days pre-infection. All groups except controls were intraperitoneally inoculated with 1 × 10⁶ tachyzoites/mouse. GCP supplementation continued for 8 days post-infection.

2.7 Parasite load quantification

Brain and duodenal tissues collected 8 days post-infection were homogenized for genomic DNA extraction. Absolute qPCR was performed using standardized DNA (200 ng/μL) to quantify parasite load. Primer sequences for NC: F: 5’-ACTGGAGGCACGCTGAACAC-3′, R: 5’-AACAATGCTTCGCAAGAGGAA-3′.

2.8 Western blot assays

Total proteins extracted with RIPA buffer (Solarbio, China) were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes. After blocking with 5% BSA, membranes were probed with primary antibodies followed by HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies. Signals were detected using ECL substrate (Millipore, USA) and analyzed with Image J.

2.9 Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Group comparisons employed Student’s t-test (pairwise) or one-way ANOVA with Duncan’s post hoc test (SPSS v19.0). Graphical outputs were generated using GraphPad Prism 8. Significance thresholds: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

3 Results

3.1 Damage to BIECs-21 by NC and protective effects of GCP

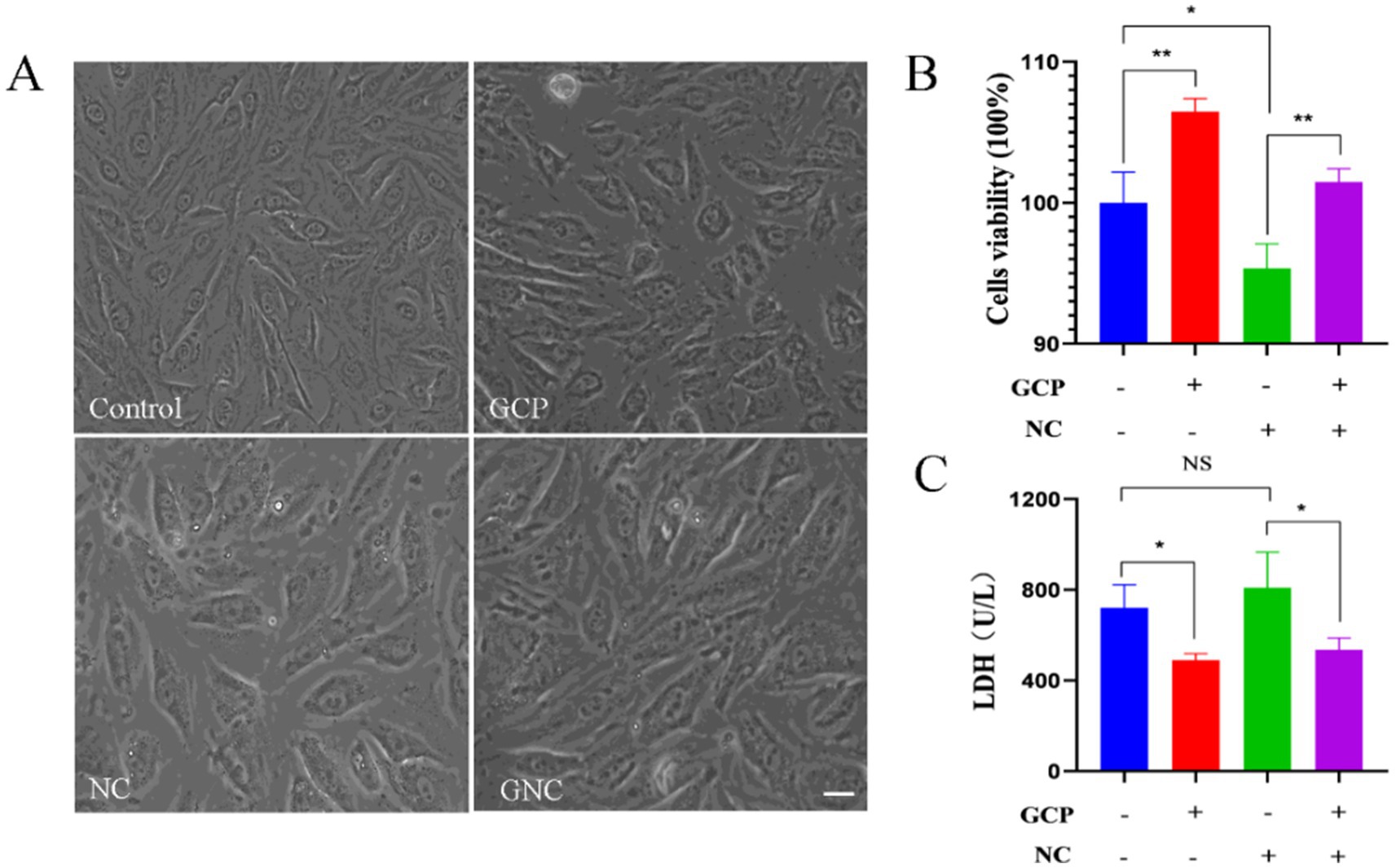

No morphological changes were observed in BIECs-21 among control, NC group, GCP group or GNC group (Figure 1A). However, cell viability significantly increased in the GCP group and decreased in the NC group compared to controls. GCP pretreatment markedly inhibited NC-induced viability reduction (Figure 1B). Furthermore, LDH activity was significantly lower in the GCP group than in controls, while the NC group exhibited a trend toward elevated LDH. Notably, GCP pretreatment (GNC group) substantially reduced LDH activity relative to the NC group (Figure 1C).

Figure 1. Damage to BIECs-21 by NC and protective effects of GCP. (A) Morphology of BIECs-21 cells in different treatment groups. (B,C) Cells viability and LDH activity of BIECs-21 with NC infected for 4 h and pretreated with GCP for 12 h. p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. NS, no significant differences.

3.2 Transcriptomic profiling of differentially expressed genes (DEGs)

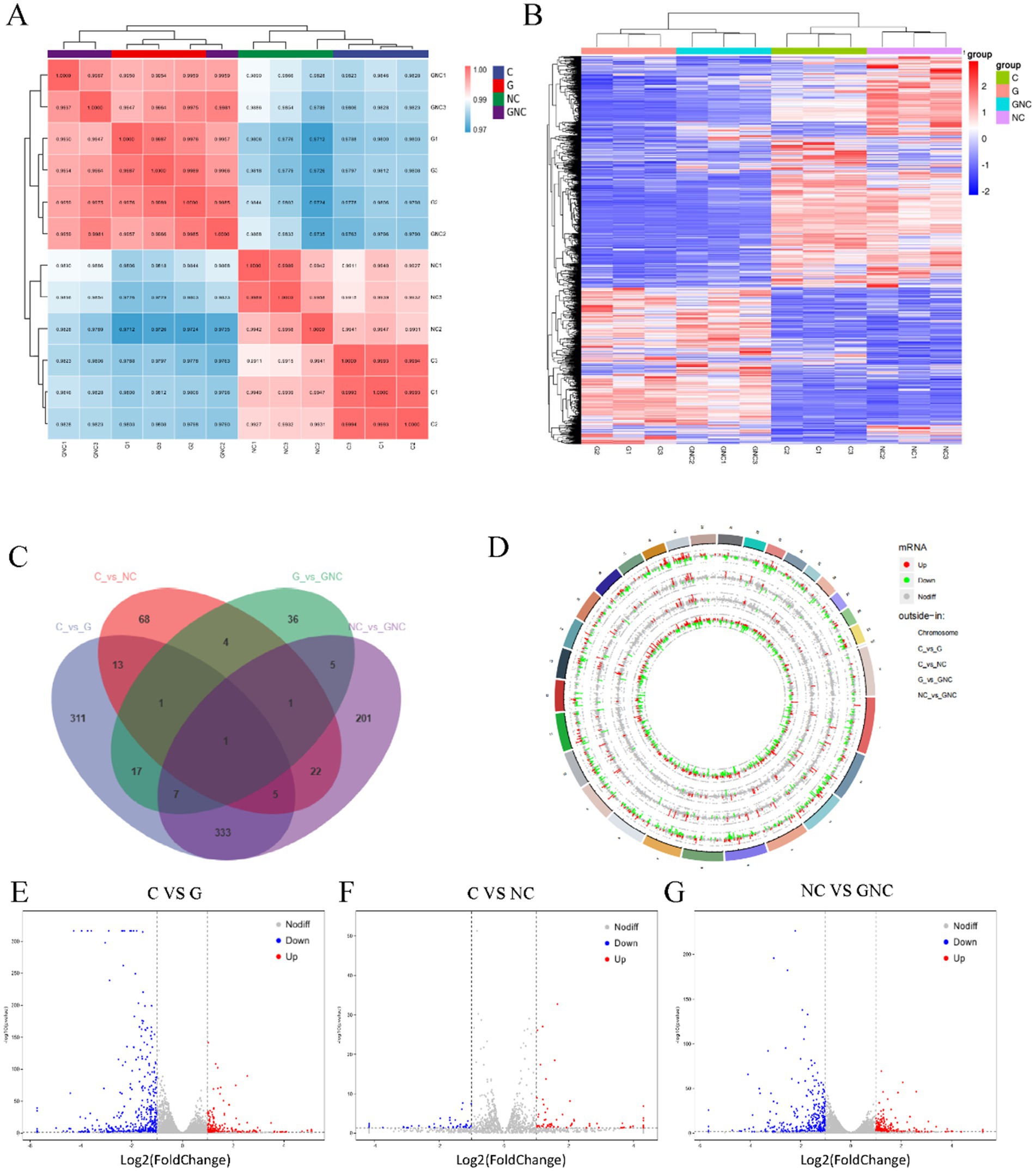

Transcriptomic analysis revealed high reproducibility and intergroup correlation (Figure 2A). Comparative DEG analysis identified significant differences between G (GCP-treated) vs. C (control), NC vs. C, and GNC vs. NC groups, with pronounced changes in G vs. C and GNC vs. NC (Figure 2B). Specifically, 688 DEGs (226 upregulated, 462 downregulated) were detected in G vs. C, 115 DEGs (69 upregulated, 46 downregulated) in NC vs. C, and 575 DEGs (216 upregulated, 359 downregulated) in GNC vs. NC (Figures 2C–G).

Figure 2. Transcriptome analysis of BIECs-21 pretreated with GCP and infected with NC. (A) Correlation analysis of patterns of gene expression in each group. (B) A heatmap of DEGs in each group. (C) Venn diagram of the number of DEGs in each group. (D) Circular visualization of the genomic alterations in BIECs-21 exposed to NC and pretreated with GCP. (E) A volcanic map of DEGs in control and GCP group. (F) A volcanic map of DEGs in control and NC group; (G) A volcanic map of DEGs in NC group and GCP-pretreated group.

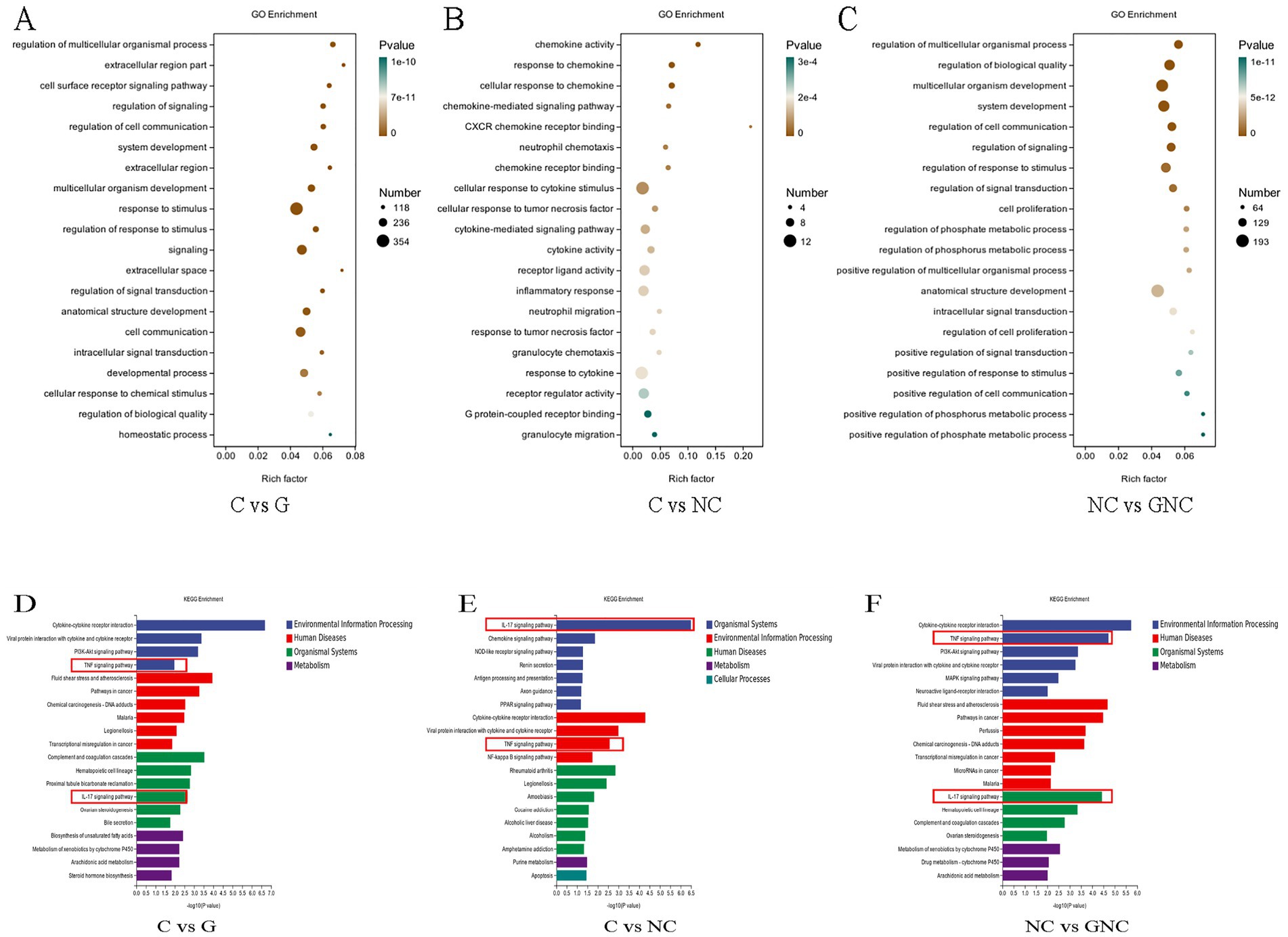

3.3 Functional annotation of DEGs

GO enrichment analysis indicated that NC altered immune-related processes in BIECs-21, including chemokine-mediated signaling, neutrophil chemotaxis and inflammatory response. GCP exerted protective effects by modulating stimulus response regulation, signal transduction and cell proliferation (Figures 3A–C). KEGG pathway analysis highlighted significant enrichment of DEGs in IL-17 and TNF signaling pathways across groups (Figures 3D–F). Cross-comparison of these pathways revealed upregulated inflammatory genes (FOSB) in NC vs. C and downregulated CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein β(C/EBPβ) and FOS in GNC vs. NC.

Figure 3. Functional annotation of DEGs. (A–C) GO enrichment analysis of DEGs. (D–F) KEGG enrichment pathway analysis of DEGs.

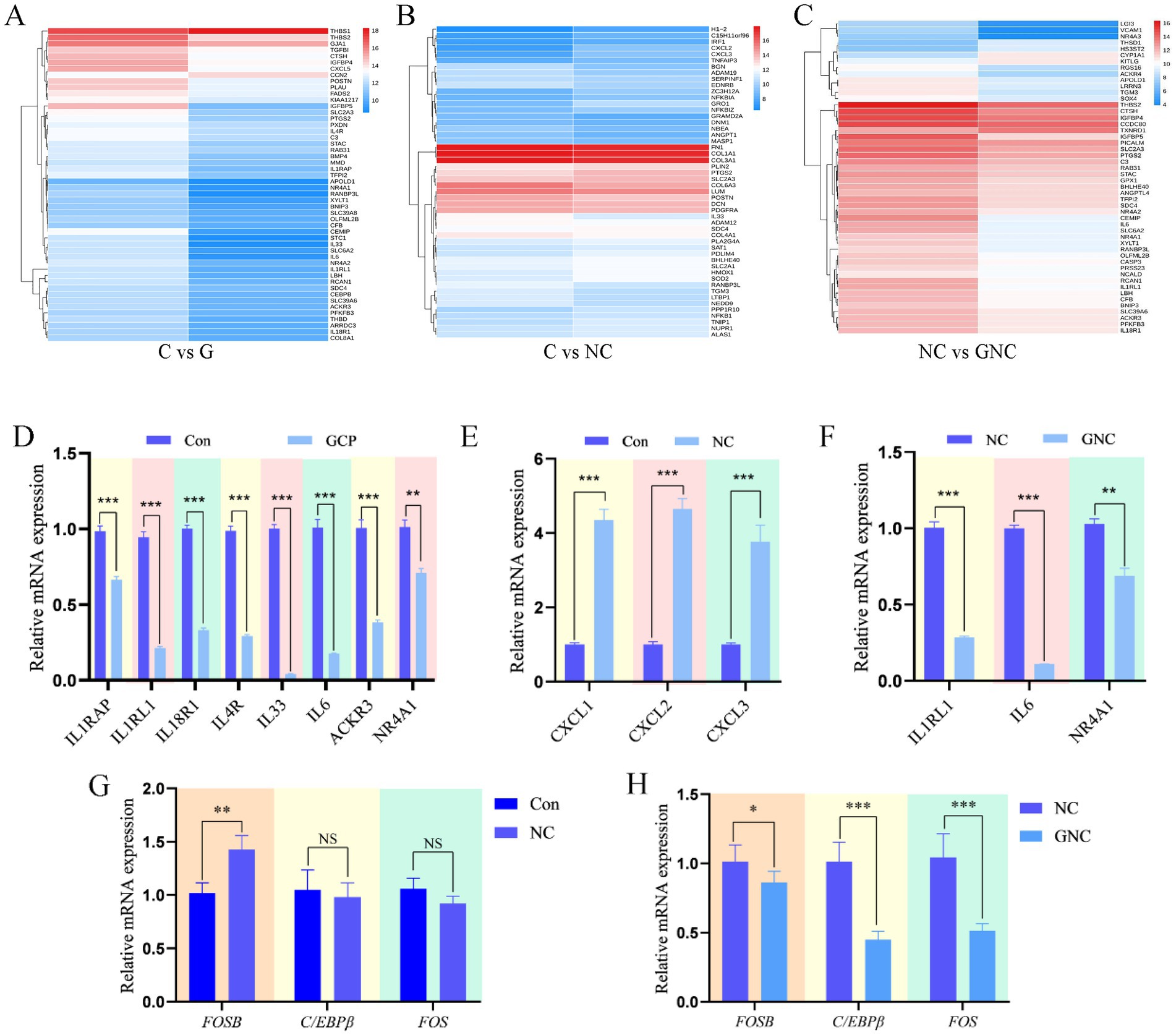

3.4 Validation of DEGs

Cluster heatmaps of top 50 DEGs (Figures 4A–C) and qRT-PCR validation confirmed transcriptomic data consistency. Compared to controls, GCP downregulated IL1RAP, IL1RL1, IL18R1, IL4R, IL33, IL6, ACKR3, and NR4A1 mRNA (Figure 4D), and NC upregulated CXCL1, CXCL2, and CXCL3 mRNA (Figure 4E). GNC downregulated IL1RL1, IL6, and NR4A1 mRNA versus NC (Figure 4F). Additionally, FOSB mRNA was elevated in NC vs. C, while C/EBPβ and FOS mRNA were reduced in GNC vs. NC (Figures 4G,H). These results suggest that NC exacerbates inflammation via FOSB upregulation, whereas GCP attenuates damage by suppressing C/EBPβ and FOS expression.

Figure 4. qRT-PCR validation of transcriptome sequencing data. (A–C) DEG heatmaps of top 50 in each group. (D–F) qRT-PCR validation of differentially expressed genes among groups. (G,H) qRT-PCR was used to verify the signaling pathways identified by transcriptome sequencing. The data are expressed in the form of “Mean±SEM.” Statistical significance was calculated by Student’s t test. Significance: *p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, p < 0.001. NS, no significant differences.

3.5 GCP alleviates NC-induced intestinal damage in mice

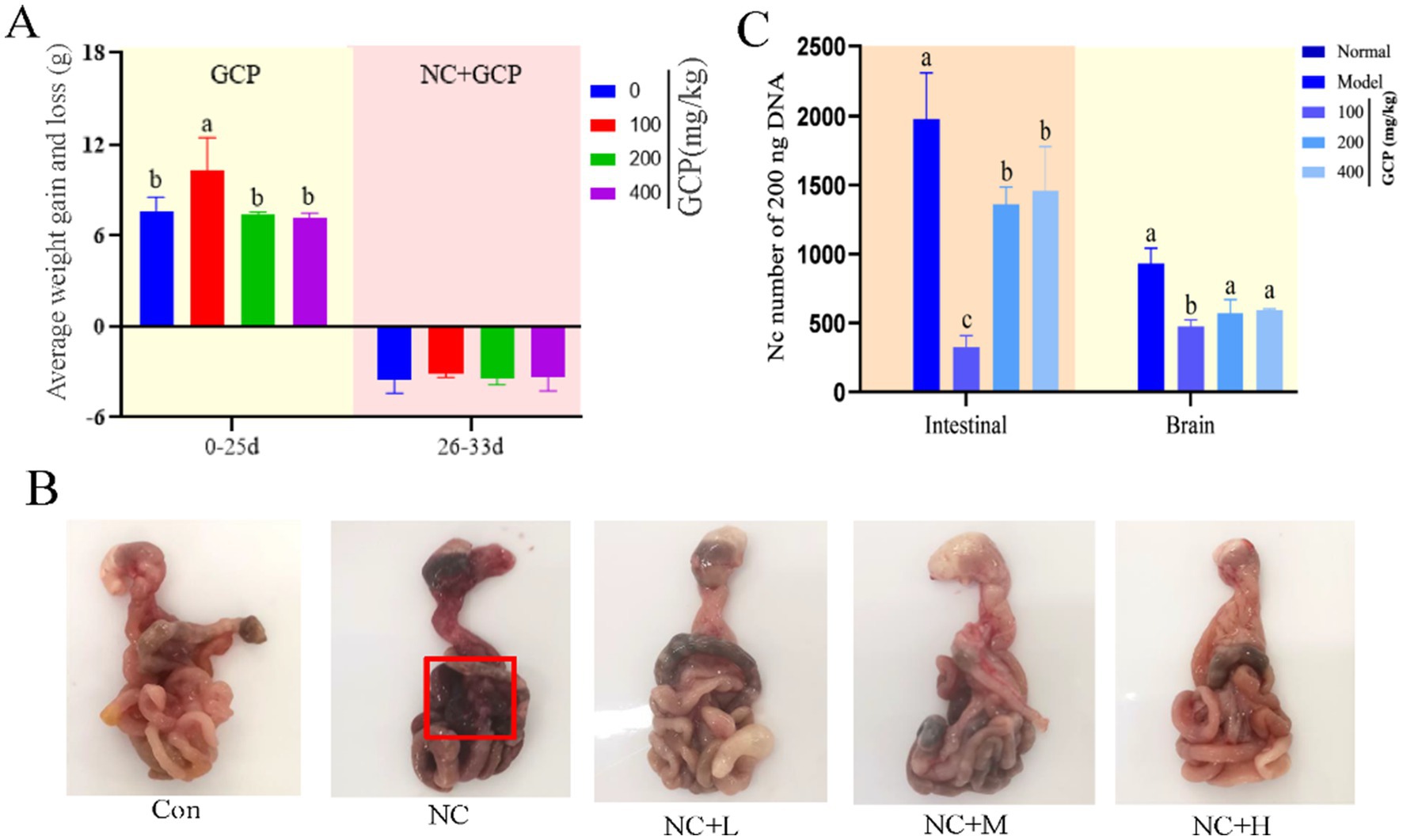

To validate the in vivo efficacy of GCP, this study established a NC-infected mouse model. In vivo, low-dose GCP (50 mg/kg) significantly increased body weight gain pre-infection and reduced post-infection weight loss (8 days post-infection) compared to untreated controls (Figure 5A). GCP improved survival rates (Supplementary Figure 2) and mitigated intestinal hemorrhage and swelling (Figure 5B). Further analysis of parasite load in the duodenum and brain tissues of mice across groups revealed that, compared with the NC group, the low-dose GCP treatment significantly reduced parasite load in these two tissues (Figure 5C).

Figure 5. The effect of GCP on body weight and intestinal injury in mice after NC infection. (A) Weight gain and loss of mice in each group. (B) Intestinal morphology of mice in each group (mesenteric bleeding is marked with a red box). (C) Parasites loaded in the duodenum and brain tissues of mice in each group. Statistical significance was calculated by one-way ANOVA with a Duncan test. The same letter in the histogram indicates that there is no significant difference between groups (p > 0.05), but different letters indicate significant difference (p < 0.05).

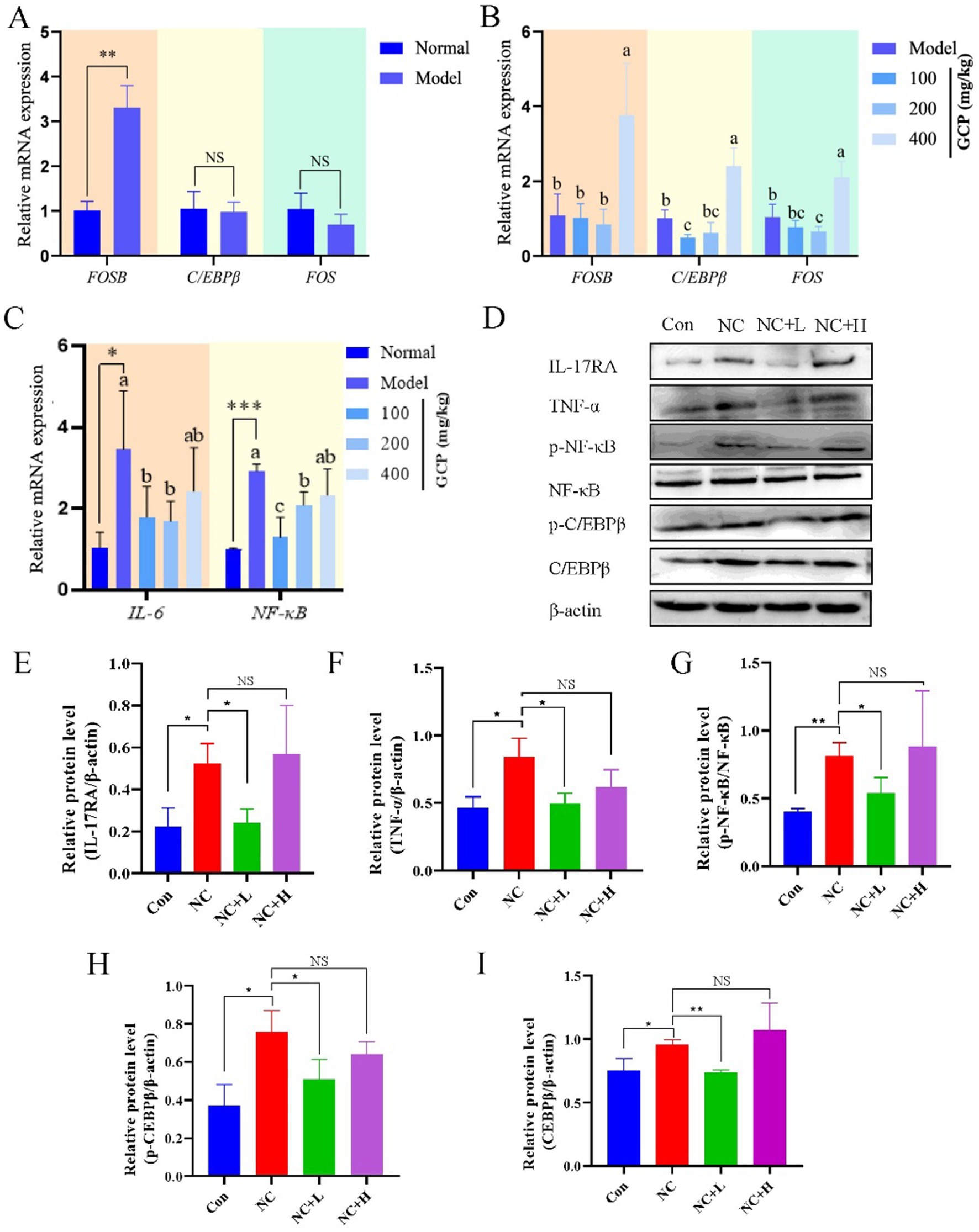

3.6 Mechanistic insights into GCP-mediated protection

To investigate the mechanism by which GCP alleviates NC-induced intestinal damage in mice, this study detected relevant biomarkers in duodenal tissues based on transcriptome sequencing. qRT-PCR analysis revealed significantly higher FOSB mRNA levels in the NC group compared with uninfected controls. C/EBPβ and FOS mRNA levels were significantly lower in GCP-treated groups versus the NC group. However, no significant differences in IL-6 or NF-κB mRNA levels were observed between the high-dose GCP group and the NC group (Figures 6A–C). Western blot analysis of proteins associated with the IL-17 and TNF signaling pathways revealed that the expression levels of TNF-α, p-NF-κB/NF-κB, IL-17RA, and p-C/EBPβ in the NC group were significantly higher than those in the control group. These elevated protein levels were effectively attenuated by low-dose GCP intervention, whereas high-dose GCP exhibited no significant regulatory effects (Figures 6D–I).

Figure 6. GCP alleviates intestinal injury induced by NC through the C/EBPβ-TNF/IL-17 signaling pathway. (A–C) Validating in vitro transcriptome sequencing data using qRT-PCR. The same letter in the histogram indicates that there is no significant difference between groups (p > 0.05), but different letters indicate significant difference (p < 0.05). (D) Detecting proteins related to the C/EBPβ-TNF/IL-17 signaling pathway using western blot. (E–I) Bar graphs show the relative protein levels, with data derived from three independent experiments. Significance: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

4 Discussion

The intestine, a critical organ for digestion, absorption, and immunity, maintains a central role in systemic homeostasis. IECs, the foundation of the intestinal mucosal barrier (18), function not only as barriers but also as frequent primary targets for pathogen attack. For example, NC, an obligate intracellular parasite, can penetrate IECs to spread to nucleated cells throughout the host (19, 20). Therefore, understanding the specific mechanisms by which GCP reduces damage to IECs caused by such pathogens holds significant importance for protecting intestinal health.

In this study, BIECs-21 served as an in vitro model to investigate cellular responses to NC infection. NC infection significantly reduced BIECs-21 viability, which was effectively mitigated by GCP pretreatment. LDH release, an indicator of cell membrane integrity, was markedly suppressed by GCP (21), demonstrating its protective effect against NC-induced cytolysis.

Transcriptome sequencing was used to screen DEGs in order to examine the interaction mechanisms between NC infection and BIECs-21, as well as the mechanism of action of GCP. Transcriptomic profiling and pathway analysis (GO/KEGG) revealed that NC infection disrupted immune regulation and signal transduction, particularly activating TNF and IL-17 signaling pathways. NC infection elevated transcript levels of IL-17 pathway-associated chemokines (CXCL1/2/3) and inflammatory genes (e.g., FOSB), while GCP pretreatment reduced IL-17/TNF pathway components, including IL-6 and IL1RAP.

TNF-α, a critical immune-regulatory cytokine in the TNF signaling pathway, activates the NF-κB and MAPK pathways by binding to TNFR1, thereby mediating cell survival/death signaling and inflammatory responses (22–25). Similarly, IL-17 cytokines (IL-17A-F) enhance antimicrobial defenses and inflammatory reactions by activating the NF-κB, MAPK, and C/EBP pathways (26–28). The AP-1 transcription factor family (e.g., c-Fos, FosB) and C/EBPβ, a member of the C/EBP transcription factor family, bind promoters of inflammatory genes (e.g., IL-6, TNF-α), amplifying inflammatory signals (29, 30). C/EBPβ, a transcription factor common to both TNF and IL-17 pathways, undergoes phosphorylation upon IL-17 stimulation, modulating inflammatory gene expression (31–33).

IL-17A enhances host immune responses to suppress Trypanosoma cruzi infection by promoting macrophage microbicidal activity (34, 35). In this study, NC infection upregulated FOSB expression, whereas GCP suppressed C/EBPβ and FOS expression, suggesting that GCP alleviates NC-induced inflammation by targeting C/EBPβ.

In vivo, low-dose GCP attenuated weight loss, mesenteric hemorrhage, and parasite loads in intestinal and cerebral tissues of NC-infected mice. Consistent with transcriptome data, NC infection elevated duodenal FOSB mRNA and IL-17/TNF pathway-related protein expression, while GCP inhibited C/EBPβ/FOS expression and downstream signaling. Furthermore, GCP significantly reduced both total C/EBPβ protein level and its phosphorylation level, resulting in a decrease in the absolute level of the active phosphorylated form, p-C/EBPβ. These findings indicate that GCP not only inhibits C/EBPβ protein synthesis but also effectively suppresses its phosphorylation. In addition, the findings support the role of GCP in alleviating intestinal damage by modulating C/EBPβ activity. However, high-dose GCP did not demonstrate a therapeutic effect, potentially due to adverse effects on pathways related to gut microbiota and glucose metabolism (36–38).

Several questions warrant further investigation, including the mechanisms underlying the role of gut microbiota in the anti-NC effects of GCP, and the molecular cascades through which GCP regulates the IL-17 and TNF signaling pathways by C/EBPβ. Nevertheless, this study demonstrates that GCP enhances the ability of IECs to resist NC infection by modulating immune-related signaling pathways (Figure 7).

5 Conclusion

In conclusion, this study provides an in vitro model for elucidating the pathogenic mechanisms of host-pathogen interactions and establishes a theoretical foundation for developing natural medicinal agents aimed at preventing and treating pathogen-induced intestinal injury.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are publicly available. This data can be found here: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA1398535.

Ethics statement

The animal study was approved by the Experimental Animal Care and Utilization Committee of Henan University of Science and Technology (AW20602202-1-2). The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

SW: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SM: Data curation, Validation, Writing – review & editing. YA: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Data curation. WQ: Resources, Writing – review & editing. YM: Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition. SG: Writing – review & editing, Resources. CZ: Funding acquisition, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This work was supported by the grants from National Key Research and Development Program of China (No.2024YFE0111600), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31872537), Young Scientists Fund project of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31502053), Natural Science Foundation of Liaoning Province (2024-MS-238).

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge TopEdit LLC for the linguistic editing and proofreading during the preparation of this manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that Generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fvets.2025.1753653/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Oswald, IP. Role of intestinal epithelial cells in the innate immune defence of the pig intestine. Vet Res. (2006) 37:359–68. doi: 10.1051/vetres:2006006,

2. Neurath, MF, Artis, D, and Becker, C. The intestinal barrier: a pivotal role in health, inflammation, and cancer. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2025) 10:573–92. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(24)00390-X,

3. Tang, X, Liu, H, Yang, S, Li, Z, Zhong, J, and Fang, R. Epidermal growth factor and intestinal barrier function. Mediat Inflamm. (2016) 2016:1927348. doi: 10.1155/2016/1927348,

4. Hansen, R, Thomson, JM, El-Omar, EM, and Hold, GL. The role of infection in the aetiology of inflammatory bowel disease. J Gastroenterol. (2010) 45:266–76. doi: 10.1007/s00535-009-0191-y,

5. Sweeny, AR, Clerc, M, Pontifes, PA, Venkatesan, S, Babayan, SA, and Pedersen, AB. Supplemented nutrition decreases helminth burden and increases drug efficacy in a natural host-helminth system. Proc Biol Sci. (2021) 288:20202722. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2020.2722,

6. Yau, C, Low, JZH, Gan, ES, Kwek, SS, Cui, L, Tan, HC, et al. Dysregulated metabolism underpins Zika-virus-infection-associated impairment in fetal development. Cell Rep. (2021) 37:110118. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.110118,

7. Rosenberg, G, Riquelme, S, Prince, A, and Avraham, R. Immunometabolic crosstalk during bacterial infection. Nat Microbiol. (2022) 7:497–507. doi: 10.1038/s41564-022-01080-5,

8. Nam, HW, Kang, SW, and Choi, WY. Antibody reaction of human anti-toxoplasma gondii positive and negative sera with Neospora caninum antigens. Korean J Parasitol. (1998) 36:269–75. doi: 10.3347/kjp.1998.36.4.269,

9. Petersen, E, Lebech, M, Jensen, L, Lind, P, Rask, M, Bagger, P, et al. Neospora caninum infection and repeated abortions in humans. Emerg Infect Dis. (1999) 5:278–80. doi: 10.3201/eid0502.990215,

10. Lobato, J, Silva, DA, Mineo, TW, Amaral, JD, Segundo, GRS, Costa-Cruz, JM, et al. Detection of immunoglobulin G antibodies to Neospora caninum in humans: high seropositivity rates in patients who are infected by human immunodeficiency virus or have neurological disorders. Clin Vaccine Immunol. (2006) 13:84–9. doi: 10.1128/CVI.13.1.84-89.2006

11. Stenlund, S, Björkman, C, Holmdahl, O, Kindahl, H, and Uggla, A. Characterization of a Swedish bovine isolate of Neospora caninum. Parasitol Res. (1997) 83:214–9. doi: 10.1007/s004360050236,

12. Qiao, Y, Guo, Y, Wang, X, Zhang, W, Guo, W, Wang, Z, et al. Multi-omics analysis reveals the enhancing effects of Glycyrrhiza polysaccharides on the respiratory health of broilers. Int J Biol Macromol. (2024) 280:135953. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.135953,

13. Wu, L, Ma, T, Zang, C, Xu, Z, Sun, W, Luo, H, et al. Glycyrrhiza, a commonly used medicinal herb: review of species classification, pharmacology, active ingredient biosynthesis, and synthetic biology. J Adv Res. (2025) 75:249–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jare.2024.11.019,

14. Huang, C, Luo, X, Li, L, Xue, N, Dang, Y, Zhang, H, et al. Glycyrrhiza polysaccharide alleviates dextran sulfate sodium-induced ulcerative colitis in mice. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. (2022) 2022:1345852. doi: 10.1155/2022/1345852,

15. Song, W, Wang, Y, Li, G, Xue, S, Zhang, G, Dang, Y, et al. Modulating the gut microbiota is involved in the effect of low-molecular-weight Glycyrrhiza polysaccharide on immune function. Gut Microbes. (2023) 15:2276814. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2023.2276814,

16. Ye, J, Ma, J, Rozi, P, Kong, L, Zhou, J, Luo, Y, et al. The polysaccharides from seeds of Glycyrrhiza uralensis ameliorate metabolic disorders and restructure gut microbiota in type 2 diabetic mice. Int J Biol Macromol. (2024) 264:130622. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.130622,

17. Meng, S, Wang, Y, Wang, S, Qian, W, Shao, Q, Dou, M, et al. Establishment and characterization of an immortalized bovine intestinal epithelial cell line. J Anim Sci. (2023) 101:skad215. doi: 10.1093/jas/skad215,

18. Sang, G, Wang, B, Xie, Y, Chen, Y, and Yang, F. Engineered probiotic-based biomaterials for inflammatory bowel disease treatment. Theranostics. (2025) 15:3289–315. doi: 10.7150/thno.103983,

19. Hemphill, A, Vonlaufen, N, and Naguleswaran, A. Cellular and immunological basis of the host-parasite relationship during infection with Neospora caninum. Parasitology. (2006) 133:261–78. doi: 10.1017/S0031182006000485,

20. Khan, A, Shaik, J, Sikorski, P, Dubey, J, and Grigg, M. Neosporosis: an overview of its molecular epidemiology and pathogenesis. Engineering. (2020) 6:10–9. doi: 10.1016/j.eng.2019.02.010

21. Wu, J, Yang, JJ, Cao, Y, Li, H, Zhao, H, Yang, S, et al. Iron overload contributes to general anaesthesia-induced neurotoxicity and cognitive deficits. J Neuroinflammation. (2020) 17:110. doi: 10.1186/s12974-020-01777-6,

22. Mujal, AM, Owyong, M, Santosa, EK, Sauter, JC, Grassmann, S, Pedde, AM, et al. Splenic TNF-α signaling potentiates the innate-to-adaptive transition of antiviral NK cells. Immunity. (2025) 58:585–600.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2025.02.012,

23. Albini, A, Di Paola, L, Mei, G, Baci, D, Fusco, N, Corso, G, et al. Inflammation and cancer cell survival: TRAF2 as a key player. Cell Death Dis. (2025) 16:292. doi: 10.1038/s41419-025-07609-w,

24. Shi, ZQ, Wen, X, Wu, XR, Peng, HZ, Qian, YL, Zhao, YL, et al. 6′-O-caffeoylarbutin of Vaccinium dunalianum alleviated ischemic stroke through the PI3K/AKT/NF-κB pathway. Phytomedicine. (2025) 139:156505. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2025.156505,

25. Gu, Y, Liu, M, Niu, N, Jia, J, Gao, F, Sun, Y, et al. Integrative network pharmacology and multi-omics to study the potential mechanism of Niuhuang Shangqing pill on acute pharyngitis. J Ethnopharmacol. (2025) 338:119100. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2024.119100,

26. Yu, C, Qiu, J, Xiong, M, Ren, B, Zhong, M, Zhou, S, et al. Protective effect of Lizhong pill on nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced gastric mucosal injury in rats: possible involvement of TNF and IL-17 signaling pathways. J Ethnopharmacol. (2024) 318:116991. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2023.116991,

27. Wu, Y, Ning, K, Huang, Z, Chen, B, Chen, J, Wen, Y, et al. Nets-cd44-il-17a feedback loop drives th17-mediated inflammation in behçet's uveitis. Adv Sci. (2025) 12:e2411524. doi: 10.1002/advs.202411524,

28. Gaffen, SL. Structure and signalling in the IL-17 receptor family. Nat Rev Immunol. (2009) 9:556–67. doi: 10.1038/nri2586,

29. Ye, N, Ding, Y, Wild, C, Shen, Q, and Zhou, J. Small molecule inhibitors targeting activator protein 1 (AP-1) miniperspective. J Med Chem. (2014) 57:6930–48. doi: 10.1021/jm5004733,

30. Yu, X, Wang, Y, Song, Y, Gao, X, and Deng, H. AP-1 is a regulatory transcription factor of inflammaging in the murine kidney and liver. Aging Cell. (2023) 22:e13858. doi: 10.1111/acel.13858,

31. Ren, Q, Liu, Z, Wu, L, Yin, G, Xie, X, Kong, W, et al. C/EBPβ: the structure, regulation, and its roles in inflammation-related diseases. Biomed Pharmacother. (2023) 169:115938. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2023.115938,

32. Luo, Y, Ge, P, Wen, H, Zhang, Y, Liu, J, Dong, X, et al. C/EBPβ promotes LPS-induced IL-1β transcription and secretion in alveolar macrophages via NOD2 signaling. J Inflamm Res. (2022) 15:5247–63. doi: 10.2147/JIR.S377499,

33. Chen, Y, Man-Tak Chu, J, Liu, JX, Duan, YJ, Liang, ZK, Zou, X, et al. Double negative T cells promote surgery-induced neuroinflammation, microglial engulfment and cognitive dysfunction via the IL-17/CEBPβ/C3 pathway in adult mice. Brain Behav Immun. (2025) 123:965–81. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2024.10.029,

34. Bermejo, DA, Jackson, SW, Gorosito-Serran, M, Acosta-Rodriguez, EV, Amezcua-Vesely, MC, Sather, BD, et al. Trypanosoma cruzi trans-sialidase initiates an ROR-γt–AHR-independent program leading to IL-17 production by activated B cells. Nat Immunol. (2013) 14:514. doi: 10.1038/ni.2569

35. Cobb, D, and Smeltz, RB. Regulation of proinflammatory Th17 responses during Trypanosoma cruzi infection by IL-12 family cytokines. J Immunol. (2012) 188:3766–73. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103478,

36. Montrose, DC, Nishiguchi, R, Basu, S, Staab, H, Zhou, X, Wang, H, et al. Dietary fructose alters the composition, localization, and metabolism of gut microbiota in association with worsening colitis. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2021) 11:525–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2020.09.008,

37. Khan, S, Waliullah, S, Godfrey, V, Khan, MAW, Ramachandran, RA, Cantarel, BL, et al. Dietary simple sugars alter microbial ecology in the gut and promote colitis in mice. Sci Transl Med. (2020) 12:eaay6218. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aay6218,

Keywords: C/EBPβ/IL-17/TNF signaling pathway, Glycyrrhiza polysaccharide, inflammatory regulation, intestinal damage, intestinal health

Citation: Wang S, Meng S, An Y, Qian W, Ma Y, Guo S and Zhang C (2026) Glycyrrhiza polysaccharide attenuates Neospora caninum-induced intestinal epithelial cell damage by the C/EBPβ/IL-17/TNF signaling pathway. Front. Vet. Sci. 12:1753653. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2025.1753653

Edited by:

Jing Yang, Yunnan Agricultural University, ChinaReviewed by:

Aoyun Li, Huazhong Agricultural University, ChinaZhenbiao Zhang, Shanxi Agricultural University College of Veterinary Medicine, China

Copyright © 2026 Wang, Meng, An, Qian, Ma, Guo and Zhang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Shuai Guo, c2h1YWlndW85MzIyQGhhdXN0LmVkdS5jbg==; Cai Zhang, emhhbmdjYWlAaGF1c3QuZWR1LmNu

Shuai Wang

Shuai Wang Sudan Meng

Sudan Meng Yanbo Ma

Yanbo Ma Cai Zhang

Cai Zhang