- Carroll Community College, Westminster, LDN, United States

We present a new empirical model for galaxy rotation curves that introduces a velocity correction term

1 Introduction

The search for the mysterious force that explains overly fast stellar rotation curves in galaxies has been going in earnest for over 40 years without a satisfactory resolution. The theory of Dark Matter was first proposed in the 1930s by Fritz Zwicky (Famaey and McGaugh, 2012; Lelli et al., 2016); Supplementary Appendix B, More than 40 years after that, Vera Rubin and Kent Ford from the Carnegie Institution of Washington noticed that stars were all rotating1 at the same speed no matter how far from the center of the Andromeda galaxy (Rubin, 2011; Bertone and Hooper, 2016).

Using

• The largest group seeks Dark Matter in various forms, like

• Another group seeks to modify the second law by multiplying

• Our approach is to look for a hidden acceleration

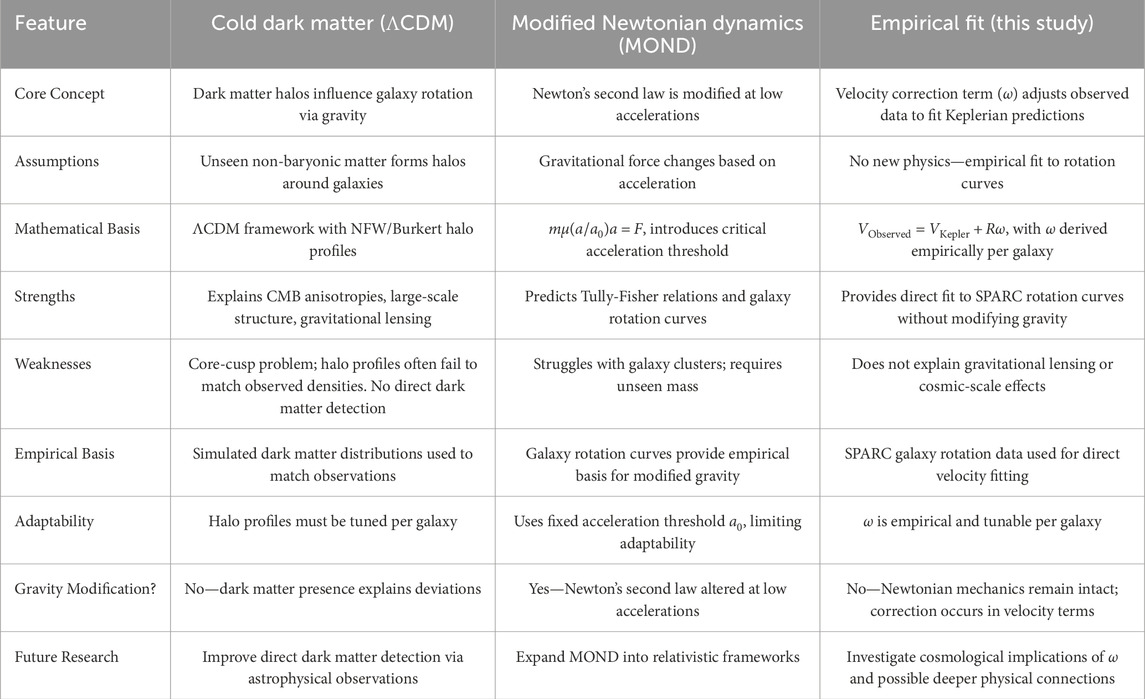

1.1 Comparison with

Various approaches have been proposed to explain galaxy rotation curves. The two dominant models—

The

• Dark matter remains undetected, despite intensive searches using direct and indirect detection methods.

• Tuning issues arise when fitting rotation curves for individual galaxies, requiring adjustments to halo profiles.

• Small-scale structure inconsistencies suggest dark matter might behave differently than originally modeled.

MOND: Modified Gravity Approach

Modified Newtonian Dynamics (MOND) seeks to eliminate dark matter by modifying Newton’s laws at low accelerations (Sanders et al., 2002). It introduces a function

• Fails to explain gravitational lensing effects, which require an unseen mass component.

• Does not naturally fit large-scale cosmic observations, such as CMB patterns and galaxy clustering.

• Requires an arbitrary acceleration scale

While both

2 Methods

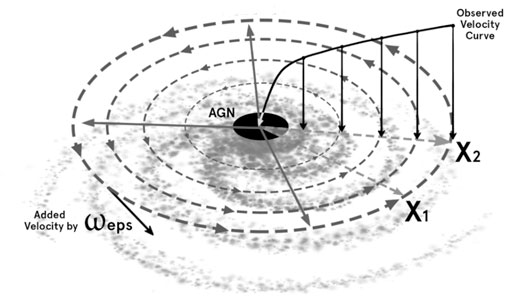

The goal of this effort was to reproduce the Expected Kepler stellar velocity graphs by working backwards from the observed velocities. We mathematically superimposed a disk over the stars for each data set, then rotated opposite the stellar direction in each galaxy. We thus subtracted the angular velocity of this rotating disk

3 Data elements

3.1 The rotation curve velocities predicted by kepler

Although we have been able to collect observations of stellar velocities for the subjects of this study, the complexity of calculating Expected Kepler results for each galaxy is daunting. This is because the methods used to accomplish this require the aggregation of several data sets from luminosity to HI mass. Conveniently, the SPARC provides 12 such calculations for each galaxy which we include in the bottom 12 graphs of our Figures 5–8. Our task is measuring stellar velocity, which is simpler than determining the distribution of potentially undetectable galactic mass. Therefore, we employ a shortcut that calculates the Kepler end points for the nearest and farthest stars from the center of the galaxy. This simplification removes the need to detail the shape of the curve between the two end points. This is reasonable because the observed nearest star’s velocity is very close to identical under both observed and Keplarian predictions. As a rule, the observed inner-most star is moving just slightly faster than a Kepler prediction. The farthest star is easy to calculate with Kepler. Being out on the rim of the galaxy, for our selections, it is often well outside any massive halo that might affect its velocity. This allows us compute our projected velocity curves aligned with known predictions at both inner and outer extremes of the galaxy.

3.2 Description of an empirical footprint that is tunable

We overlay a flat, spinning empirical correction layer that accounts for the difference between observed stellar positions versus those predicted by Kepler. By adding this theoretical disk to all the observed stellar velocities, each inherits some velocity offset that is added to all observed measurements. Figure 1 shows positions

Figure 1. Conceptual framework illustrating the relationship between key variables and model outcomes.

3.3 SPARC - data selection and filtering

The rotation curve data used in this study originates from the Spitzer Photometry and Accurate Rotation Curve (SPARC)project http://astroweb.cwru.edu/SPARC/. Of the 175 galaxies surveyed, we selected only the 99 with the highest quality rating

Two galaxies—NGC5005 and UGC11914—were excluded due to statistically significant deviation from the velocity correction trend. Specifically, their

SPARC also provides 12 expected galaxy rotation curves, which we present below our findings in Figure 5 through Figure 8. These reference models—selected by SPARC for their popularity and diagnostic clarity—show strong visual and structural similarity to our results. To clarify the nature of our own fits: all curve fits in Figures 9–12 are exploratory and selected post hoc for visual alignment; no unified model class was applied.

The observational data used in Tables 1, 2 include published 1-sigma uncertainties for velocity and radius measurements, sourced from Corbelli et al. (1999, 2003) and the SPARC database. In this study, we treated these values as point estimates to isolate and characterize the correction term

3.4 M33 as a case of one

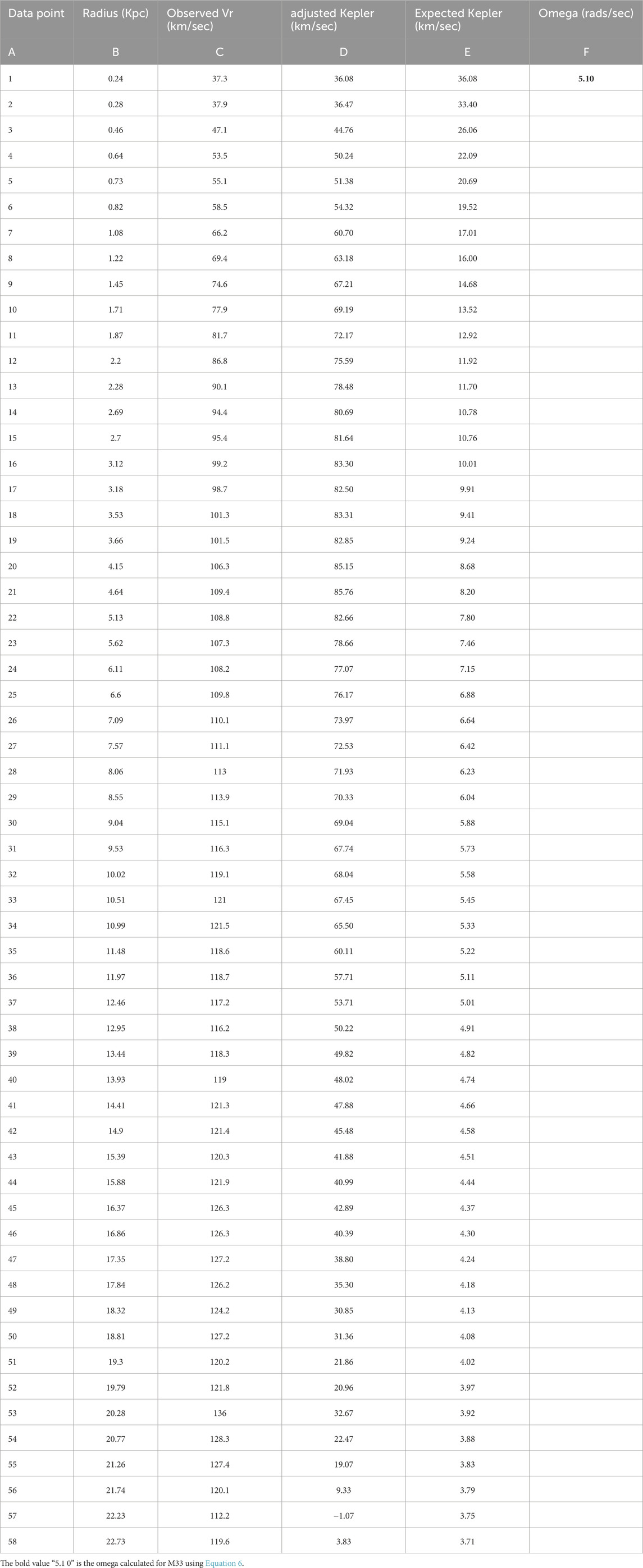

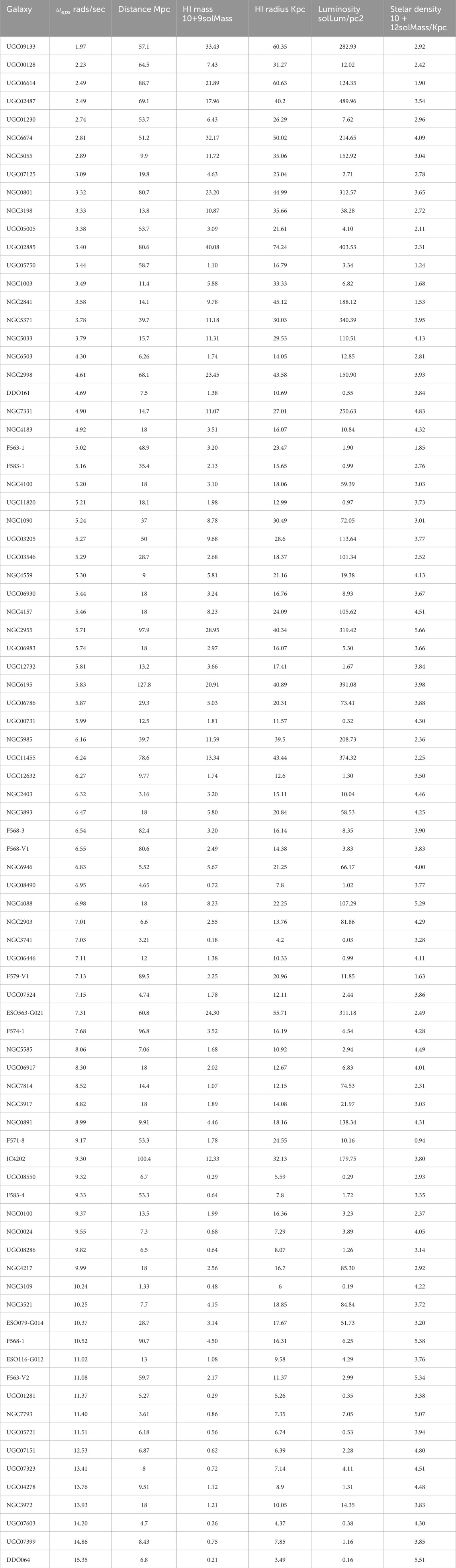

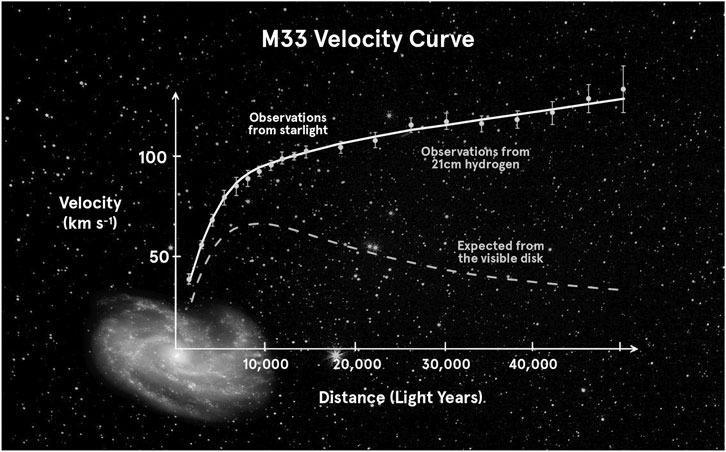

The graph of M33’s rotation curve is well-known and the observed stellar velocities are faster than Kepler predicts. The data from the charts in Table 1 (Corbelli et al., 2014); and our artists rendering of the M33 Velocity Curve in Figure 2; (Corbelli and Salucci, 1999); come from Corbelli’s work in two papers. In Table 1, note that columns 2 and 3, Radius in

Using Equation 1, the tangential velocity formula:

The hidden angular velocity is calculated using Equation 2 (below),

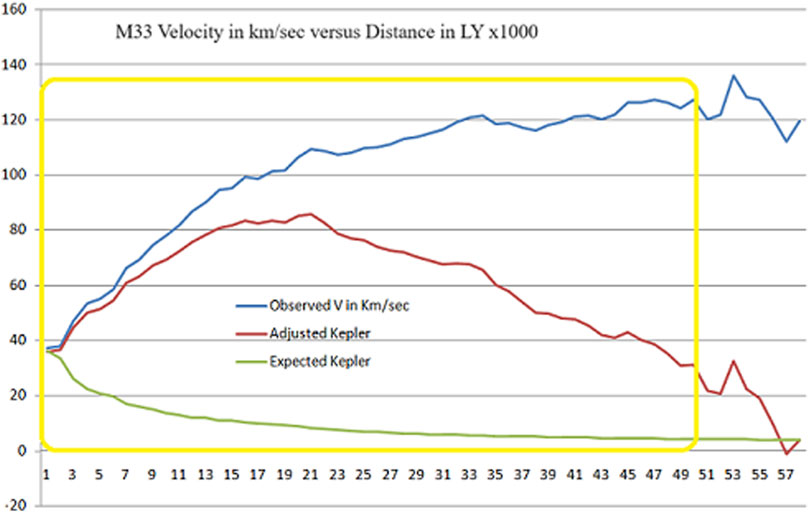

This yields column 6 in Table 1 which is detailed in Section 4.2. Note the interesting similarity between the black M33 Classic Velocity Curve (Figure 2) and the

3.5 Examination and comparison of the M33

Figure 2 shows M33’s rotation curve (Corbelli and Salucci, 1999) as the target of comparison with Figure 3 which was created using the method described in this work. The goal was to show that the graph could be entirely reproduced using just two things; our method and observed velocity data. The yellow boxed in area of Figure 3 highlights the same distance versus velocity footprint shown in Figure 2. Note that Figure 3 data extends beyond the 50,000 light year limit on Figure 2. Figures 2, 3 are what we are comparing. The adjusted Kepler line in red agrees with theory. The Observed V in km/sec is taken straight from data Table 1 data (Corbelli et al., 2014). More detailed comparisons will follow in Sections 4.3 and 4.4.

3.6 Working examples for Table 1

The Appendix contains working examples for Table 1 that demonstrate how calculations were made in each column. Examples are from the top or first entries of the table. Supplementary Appendix Figures 14, 15 may help to visualize our methods.

4 Method of calculation

4.1 Calculations with kepler

In order to test our model with a larger data set, we needed to have a method to calculate the angular velocity of the spinning empirical correction layer we predict. That angular velocity would have to be such that each observed rotation curve would get corrected back to Kepler’s predictions when it was accounted for. Equation 2 is the starting point to solve for

4.2 Solving for omega

The SPARC data set contains the observed rotation curves and accurate radius data. It also contains 12 different predicted velocity curves in a separate section that we do a closer comparison to in Section 4.4. Accurate Kepler predictions are reliant on a combination of mass distribution and luminosity factors that project where the mass is in a galaxy. We will save doing point-by-point comparisons for a later paper, since there are 12 types for each of our 84 results. As mentioned previously, we only need to do the calculation for the closest and farthest stars from the center of the galaxy in each data set. We used Kepler’s third law (Equation 4) for all our predictions. Then we converted it to a form that related velocity and radius. Subscript “1” is the closest3 star, subscript “2” is the farthest star from galactic center. To get Equation 5,

Equation 4 was converted to Equation 5.

Finally, substituting Equation 5 above into Equation 2 yields Equation 6.

This provides Expected Kepler

4.3 Shortcut to understanding this method

a. Find the star with the greatest radius from the center of the galaxy that has reliable data.

b. Note its observed velocity.

c. Take the velocity and radius and input into section 4.2 to calculate

d. Redraw the velocity graph using

4.4 Tests using the SPARC data

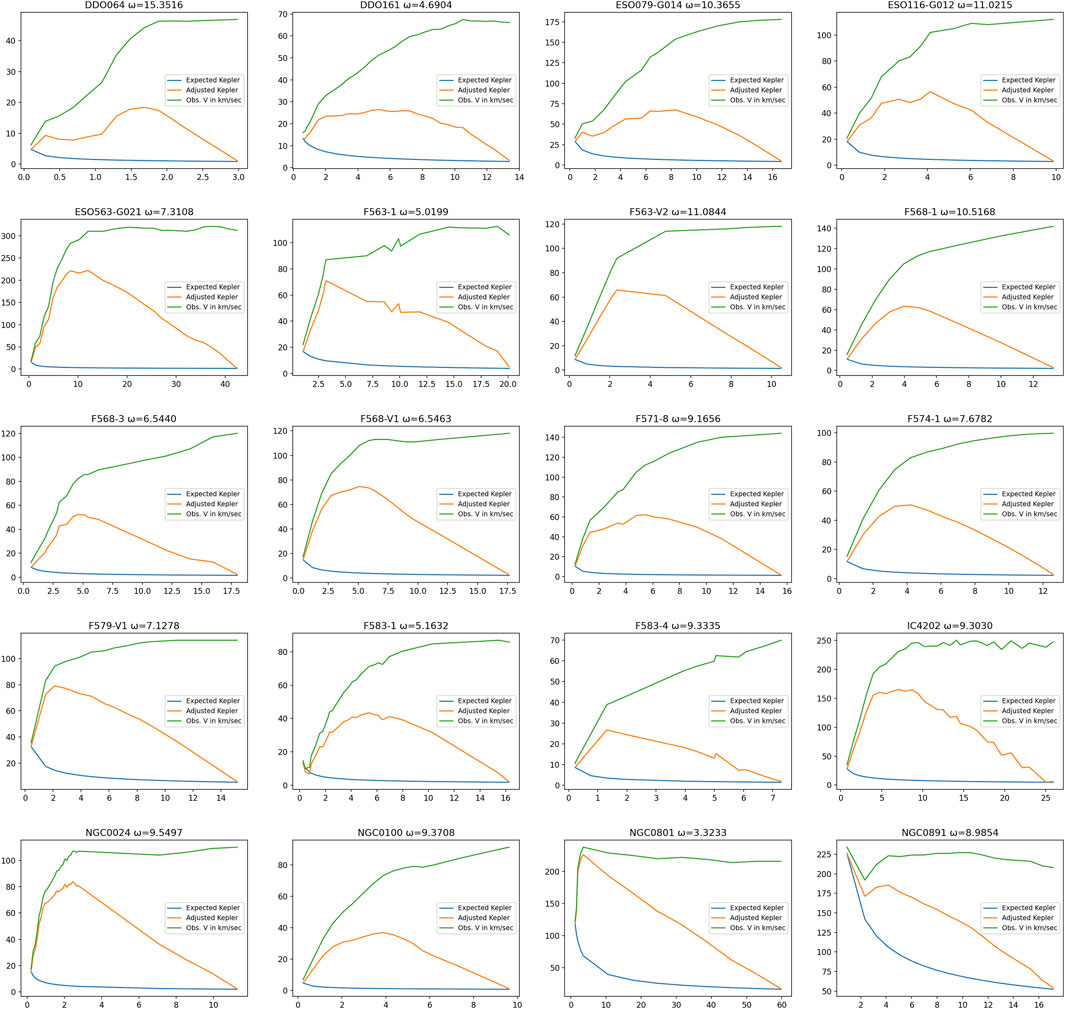

We used a Jupyter Labs program with Equations 2, 5 and 6 above and applied them to the 84 galaxies selected for this survey. Section 3.2 delineates what criteria were used for the 84 selected. The goal was to see if an

Data came from the SPARC tables at http://astroweb.cwru.edu/SPARC/MassModels. The first 20 of galaxy plots are displayed in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Comparative visualization of model performance across input scenarios, highlighting predictive accuracy and R-squared values. The figure presents 20 representative selections from our dataset, all sourced from the SPARC archive.

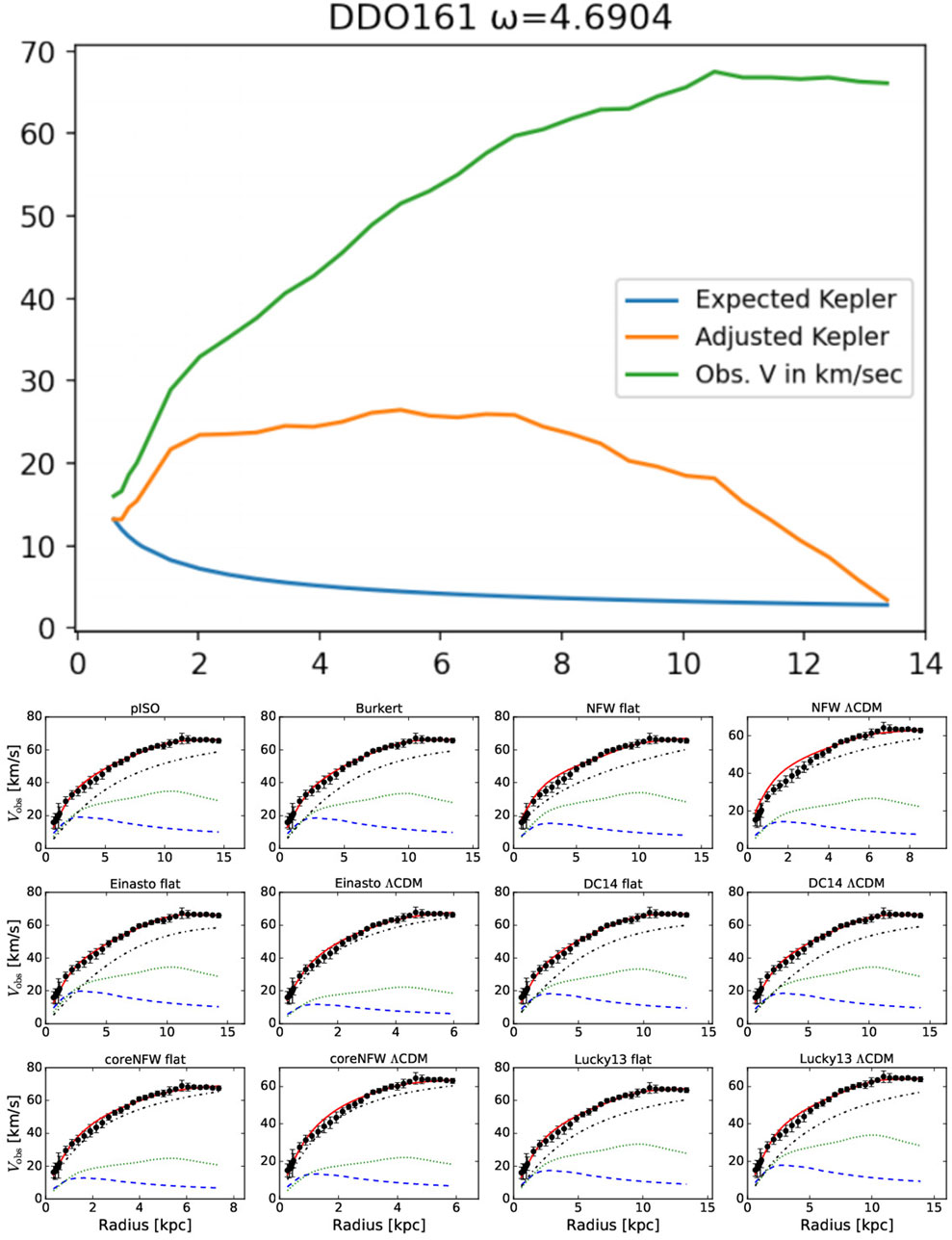

4.5 A closer examination of our results versus SPARC velocity curves

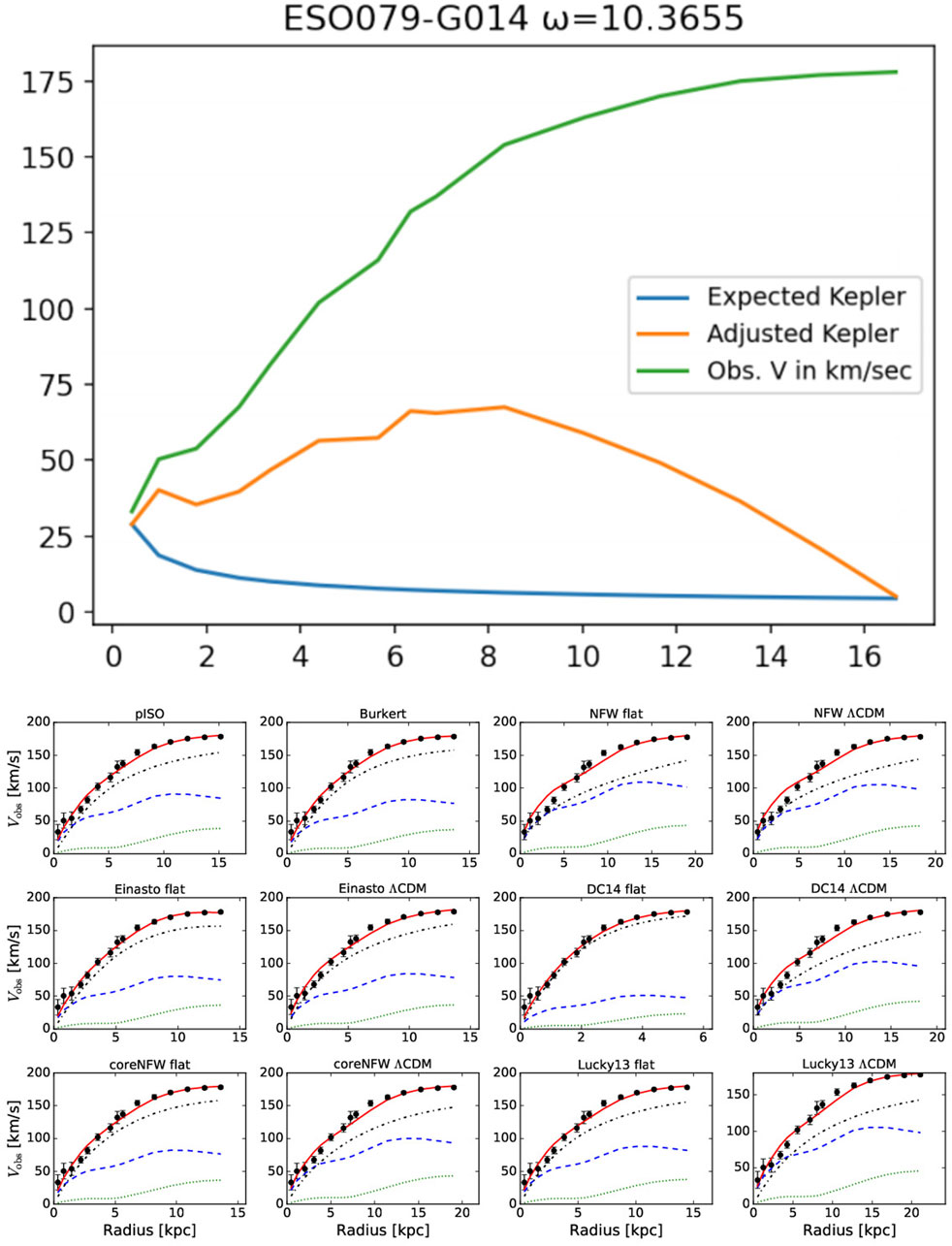

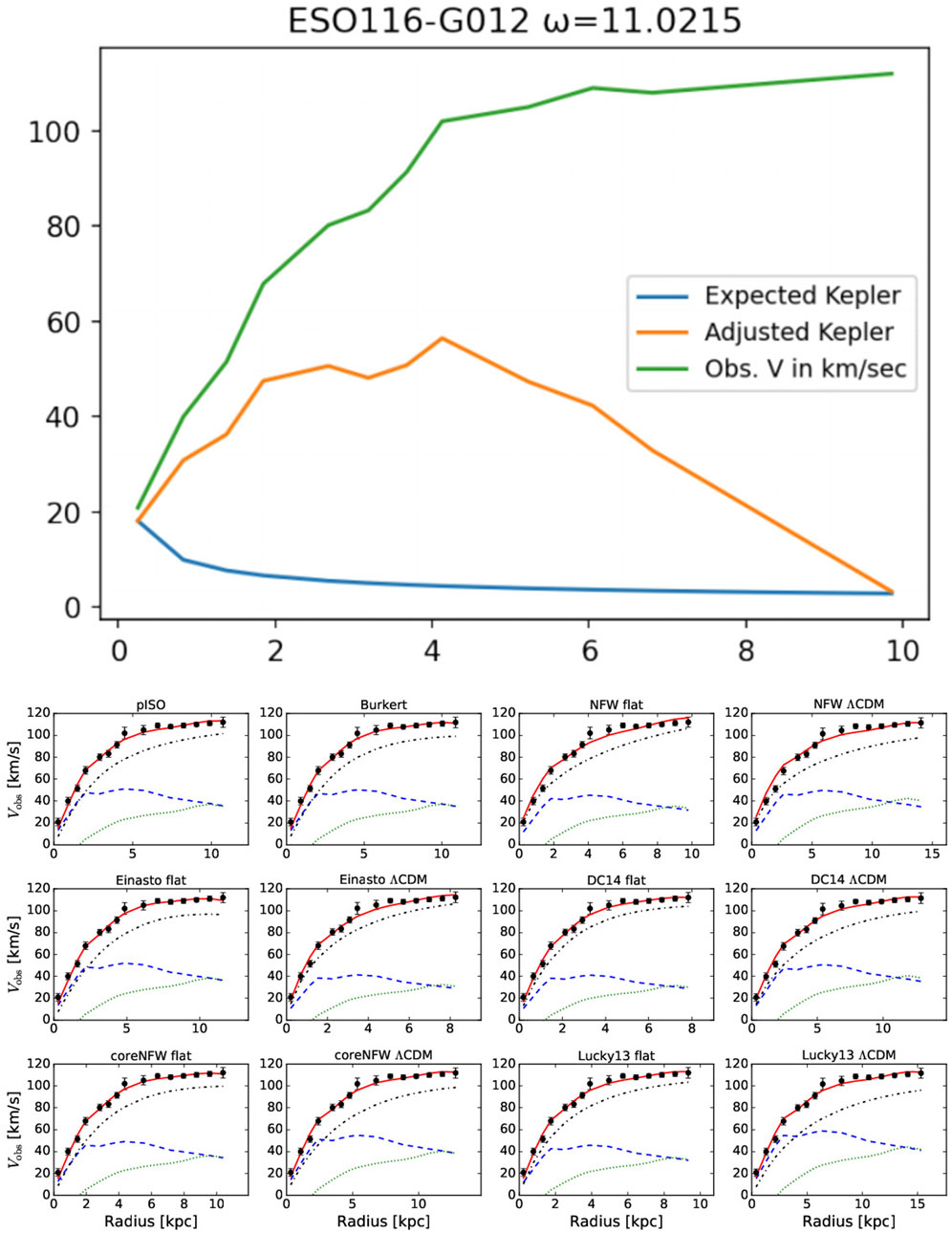

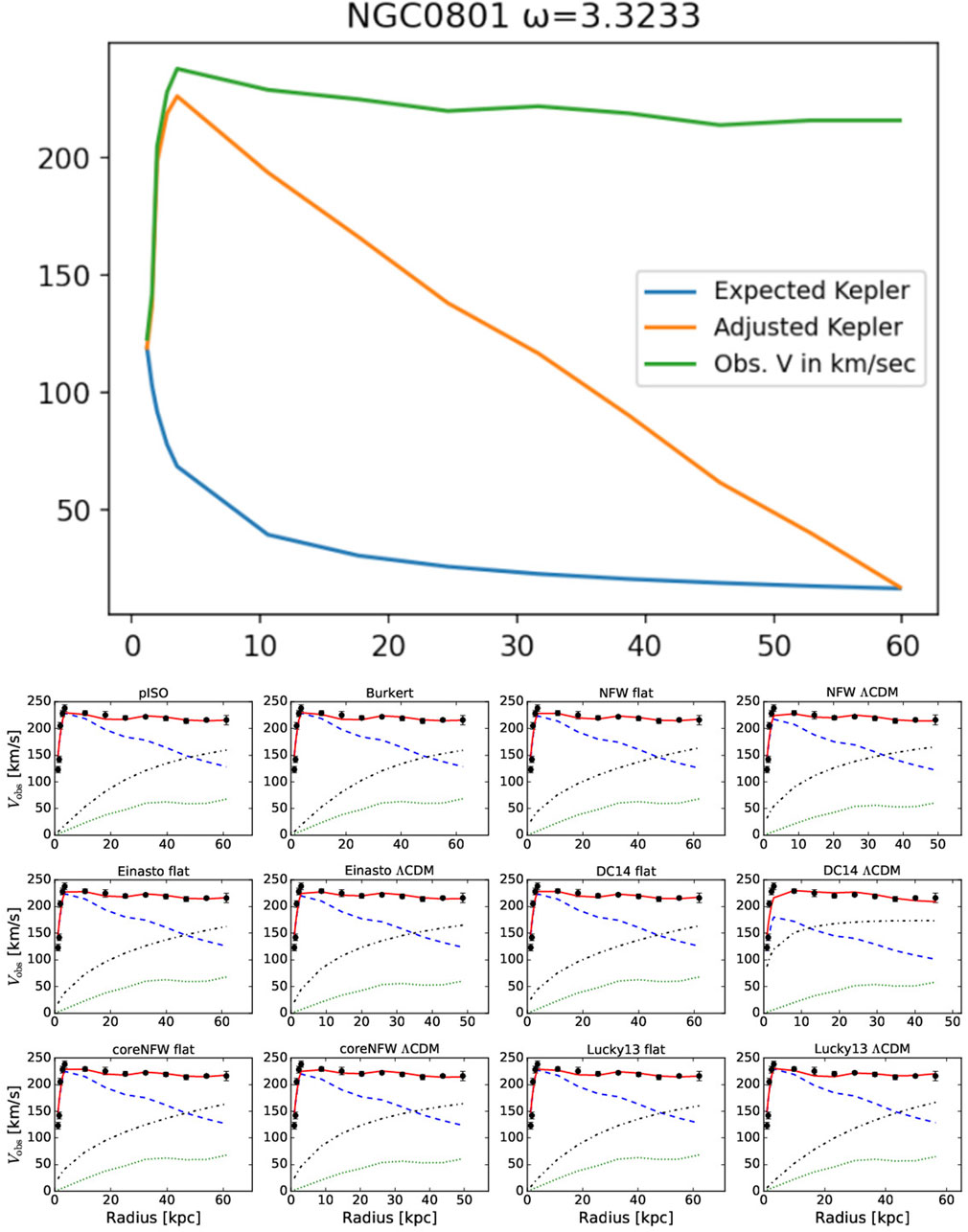

Figure 5 through Figure 8 present direct comparisons between SPARC rotation curve models and our own velocity reconstructions for four representative galaxies: DDO161, ESO079-G014, ESO116-G012, and NGC0801. Each figure contains two components: a top panel showing our EPS-generated velocity curves, and a bottom grid of twelve SPARC model fits using various dark matter halo profiles. In the top panel, the green line represents observed rotational velocities, the red line is our EPS-projected fit, and the blue line is our Kepler approximation—calculated using only the innermost and outermost stellar radii, rather than a full baryonic mass aggregation.

Figure 5. Model output for galaxy DDO161, generated using adjusted Keplerian dynamics via Equation 2. The graph overlays our computed trajectory with SPARC-derived data curves from multiple reconstruction methods, providing contextual comparison across empirical and theoretical profiles.

The SPARC team’s bottom-panel graphs employ twelve distinct modeling algorithms (e.g., NFW, Burkert, DC14), each shown with a blue dashed line representing the dark matter halo contribution. For methodological details, refer to the SPARC database and documentation.

Figure 9 through Figure 13 extend this comparison across all 84 galaxies in our final dataset. These figures visualize the curve fittings derived from Table 2, which contains our calculated velocity correction term,

The proposed velocity correction model offers a pragmatic alternative to full baryonic mass aggregation by leveraging only the innermost and outermost stellar radii. This simplification yields substantial computational efficiency—reducing preprocessing time and eliminating the need for detailed photometric decomposition—while still achieving high-fidelity alignment with observed rotation curves. Scientifically, the model is especially useful in scenarios where:

• High-resolution mass maps are unavailable or incomplete.

• Rapid screening of large galaxy datasets is required.

• Morphological irregularities make full aggregation unreliable.

While the approach omits intermediate mass contributions, the empirical correction term

Figure 6. Model output for galaxy ESO079-G014, generated using adjusted Keplerian dynamics via Equation 2. The graph overlays our computed trajectory with SPARC-derived data curves from multiple reconstruction methods, providing contextual comparison across empirical and theoretical profiles.

Figure 7. Model output for galaxy ESO116, generated using adjusted Keplerian dynamics via Equation 2. The graph overlays our computed trajectory with SPARC-derived data curves from multiple reconstruction methods, providing contextual comparison across empirical and theoretical profiles.

Figure 8. Model output for galaxy NGC0801, generated using adjusted Keplerian dynamics via Equation 2. The graph overlays our computed trajectory with SPARC-derived data curves from multiple reconstruction methods, providing contextual comparison across empirical and theoretical profiles.

4.6 Re-examining the problem as a possible after effect

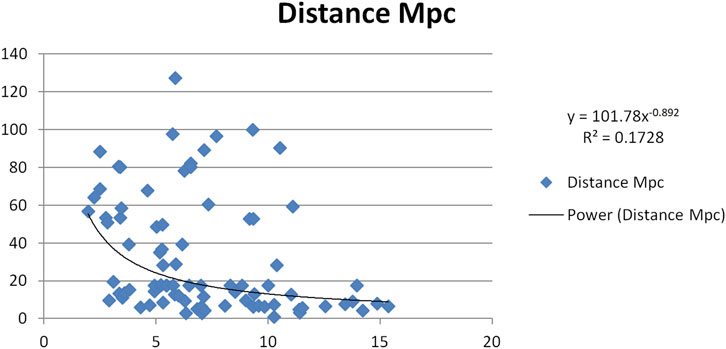

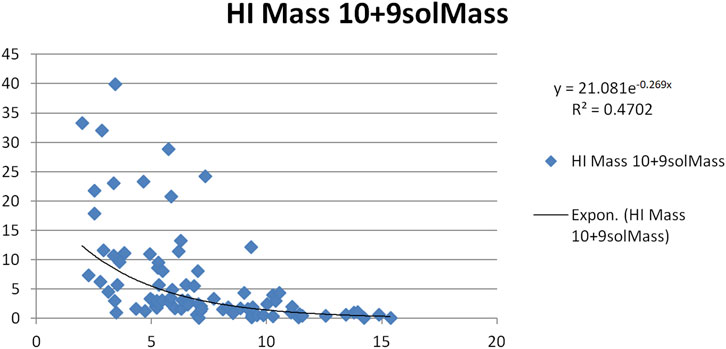

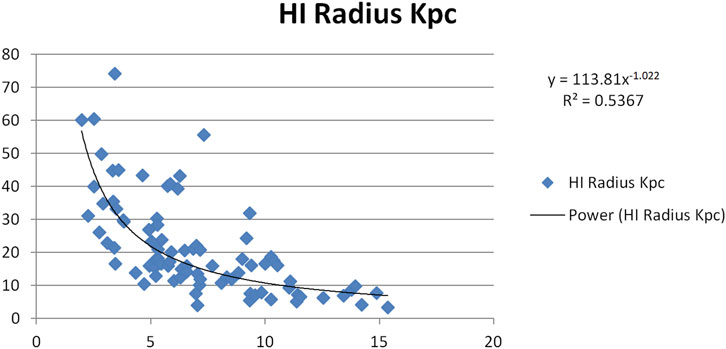

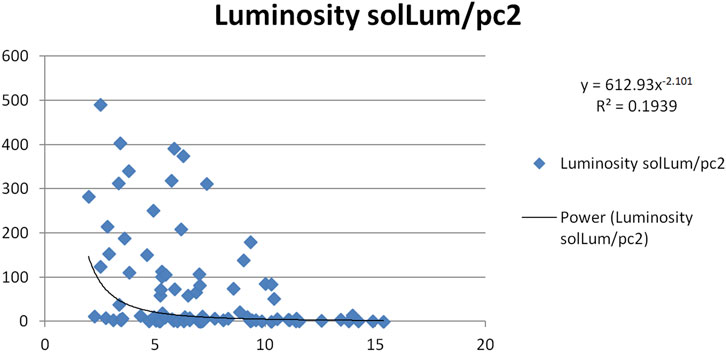

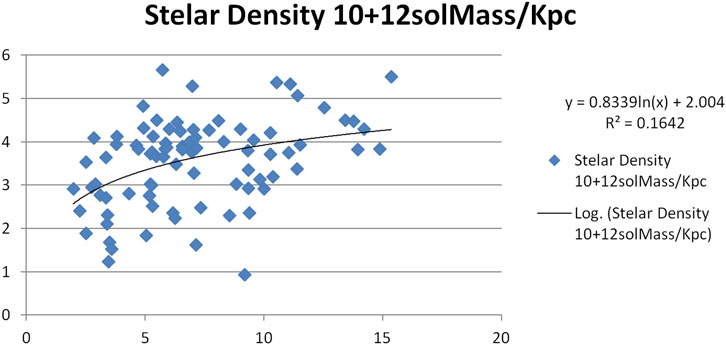

Figures 9–13 present scatter plots correlating the velocity correction terms

To address reviewer concerns, we now report the 1

• Figure 9:

• Figure 10:

• Figure 11:

• Figure 12:

• Figure 13:

These uncertainties reflect moderate dispersion, consistent with the hypothesis that

These error bars were computed using standard least-squares regression with bootstrapped re-sampling across the 84-galaxy data set. Full regression diagnostics are available in Supplementary Appendix B.

Five Curve Fittings for Table 2.

5 Other papers with supporting themes

We summarize sections of several papers that either influenced or support the framework we use to simulate our stellar velocity solution.

5.1 Lovas and linear scaling of mass

In his June 2022 paper, Lovas (2022) said, “Measurements from galaxies spanning a broad range of morphology reveal a linear scaling of enclosed dark to luminous mass that is not anticipated by standard galaxy formation cosmology.” Some of the conclusions Lovas makes about the SPARC database parallel our own. Lovas finds that, “No dark matter candidate possesses a theoretical property that would lead to a linear scaling.” He then uses the same SPARC data set that we do in this paper, and selects 4 galactic candidates as test cases. In the summary, Lovas states, “In the framework of standard galaxy formation theory, the linear scaling of enclosed dark to luminous mass would require tuning the dark matter profile of each galaxy.”

• Lovas finds that linear scaling exists in the SPARC data and that tuning for each galaxy is recommended.

5.2 Chan and universal dark matter-baryon relations

In December 2022, Chan (2022) related total dynamical mass with total baryonic mass in galaxies. Chan’s conclusions align with our findings. Notably, he selected the same SPARC database we used for our study. Chan states, “We can derive the enclosed baryonic mass and the total enclosed mass by Vb and V respectively. The total baryonic mass for each galaxy can be approximately indicated by the last data point of Vb at the largest radius r = rb while the final data point of V (i.e., Vc) can give the total enclosed mass M500 for each galaxy.”

We also chose the last data point for our Kepler calculation using the same reasoning.

• Chan relates total dynamical mass with total baryonic mass.

5.3 Clowe and the bullet cluster

In their 2006 paper, Clowe et al. showed images of the Bullet cluster with gravitational lensing (Clowe et al., 2006). They stated, “By using both wide-field ground-based images and HST/ACS images of the cluster cores, we create gravitational lensing maps showing that the gravitational potential does not trace the plasma distribution, the dominant baryonic mass component, but rather approximately traces the distribution of galaxies. An

• Clowe’s Magellan and Chandra images show that dark matter’s gravitational lensing is persistent even after being separated from large numbers of their stars.

5.4 Comparison with the Mezzi effect

A recent preprint by Benaissa (2025) introduces a relativistic framework for reconciling galactic rotation curve discrepancies without invoking dark matter. Central to this framework is the Mezzi effect, a proposed observational distortion arising from space flow dynamics. The effect suggests that distant galaxies appear compressed due to relativistic curvature, leading to systematic underestimation of orbital radii and luminous mass. Benaissa formalizes this through a radial scaling factor,

While both models—ours and Benaissa’s—achieve high-fidelity fits to SPARC data, they diverge sharply in physical assumptions and methodological design. The Mezzi effect is rooted in Painlevé–Gullstrand coordinates and geometric reinterpretation of spacetime, whereas our model remains strictly Newtonian and empirical. We introduce a velocity correction term,

Benaissa’s framework operates on a broader dataset (175 SPARC galaxies) and offers cosmological implications beyond local kinematics. Our model, by contrast, emphasizes reproducibility, transparency, and diagnostic modularity across 84 high-quality SPARC galaxies selected for data integrity. While Benaissa’s work has not yet undergone formal peer review, its empirical convergence with our findings invites further synthesis between observational kinematics and foundational physics.

This comparison underscores the growing diversity of non-dark matter approaches to galactic rotation modeling. By situating our velocity correction model alongside relativistic alternatives such as the Mezzi effect, we aim to scaffold a broader empirical dialogue that respects both methodological clarity and theoretical innovation.

6 What is omega?

The empirical correction factor

Unlike dark matter halo models or modified gravity theories, our method does not require adjusting Newtonian dynamics or invoking unseen mass. This simplicity points toward a dynamic influence with possible rotational or inertial properties at the space-time level. While we refrain from asserting a physical model in this paper, the repeatability of

At present,

Throughout this work, we remain acutely aware of the limitations imposed by velocity curve reconstruction via quadrature, as well as the constraints of Lense–Thirring (Bardeen and Petterson, 1975) frame-dragging in relativistic contexts.

Future investigations will assess whether

Our forthcoming paper will incorporate Gadget-4 simulations with two key methodological shifts: first, we model acceleration directly rather than inferring mass distributions; second, we treat

Table 3. Comparison of Cold dark matter (

7 Conclusion

The empirical model’s performance is quantitatively validated in Supplementary Appendix B, where rotation curve fits are compared head-to-head with MOND and CDM models across multiple galaxies.

• Of the 84 galaxies tested,

• HI radius has an correlation coefficient of

• HI mass has an correlation coefficient of

• The survey yielded an

• The resemblance between Figures 2, 3 for M33 is striking. Figure 4 is a partial data dump of the curves for the first 20 of our 84 galaxies surveyed which all were a very good fit for this method. Figures 5–8 show head-to-head comparisons of our Figure 4 curves (top) to SPARC calculations (bottom) that are also impressively similar using a completely different approach for calculation. We noticed that the

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

DF: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. JC: Data curation, Software, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge Robert Scherrer of Vanderbilt University for his guidance throughout this effort. We also thank Brian Riely for his contributions to statistical interpretation and graphical modeling. Figures 1, 2, Supplementary Appendix Figures 14, 15 were created by our visual artist, Katherine Flynn.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Generative AI (Microsoft Copilot) was used to assist with structural refinement and scientific phrasing throughout the manuscript. Specific contributions include: - Suggestions and refinements to the Abstract - Drafting of Section 1.1 (“Comparisons with ΛCDM and MOND”) - Assistance in defining ω and refining Table 3 language (Section 6) - Support for bitmap comparison calculations in Appendix B and B.1 All modeling, analysis, and scientific conclusions were authored and verified by the submitting author. The process improved clarity, reproducibility, and editorial precision without altering the empirical findings.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fspas.2025.1680387/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1Throughout this paper, we use the term “rotation curve” in its observational context—referring to measured velocity profiles as a function of radius, typically derived from Doppler shift data (e.g., HI or stellar spectral lines). While sometimes used interchangeably with “circular speed,” we do not claim that all measured velocities represent perfectly circular orbital motion.

1Throughout this work, and are used interchangeably to represent angular velocity estimates derived from distinct but functionally equivalent approximations. Unless otherwise specified, their usage is intended to convey observational parity rather than a strict mathematical identity

1The terms “closest” and “farthest” star are not used here as absolute measurements, but rather indicate selections based on the most reliable available distance data.

References

Bardeen, J. M., and Petterson, J. A. (1975). The lense-thirring effect and accretion disks around kerr black holes. Astrophysical J. 195, L65–L67. doi:10.1086/181711

Benaissa, B. (2025). Resolving galactic rotation curve discrepancies through a proposed relativistic observation effect. SSRN Electron. J. doi:10.22541/au.174189026.62416989/v1

Bertone, G., and Hooper, D. (2016). A history of dark matter. Available online at: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1605.04909.

Chan, M. H. (2022). Two mysterious universal dark matter–baryon relations in galaxies and galaxy clusters. Phys. Dark Universe 38, 101142. doi:10.1016/j.dark.2022.101142

Clowe, D., Bradač, M., Gonzalez, A. H., Markevitch, M., Randall, S. W., Jones, C., et al. (2006). A direct empirical proof of the existence of dark matter. Astrophysical J. 648, L109–L113. doi:10.1086/508162

Corbelli, E., and Salucci, P. (1999). The extended rotation curve and the dark matter halo of M33. Mon. Notices R. Astronomical Soc. 311, 441–447. doi:10.1046/j.1365-8711.2000.03075.x

Corbelli, E., Thilker, D., Zibetti, S., Giovanardi, C., and Salucci, P. (2014). Dynamical signatures of a ΛCDM-halo and the distribution of the baryons in M33. Astronomy and Astrophysics 572, A23. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201424033

de Blok, W. J. G., Walter, F., Brinks, E., Trachternach, C., Oh, S. H., and Kennicutt, R. C. (2008). High-resolution rotation curves and galaxy mass models from THINGS. Astronomical J. 136 (6), 2648–2719. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/136/6/2648

Famaey, B., and McGaugh, S. S. (2012). Modified newtonian dynamics (MOND): observational phenomenology and relativistic extensions. Living Rev. Relativ. 15 (10), 10. doi:10.12942/lrr-2012-10

Gentile, G., Famaey, B., and de Blok, W. J. G. (2011). THINGS about MOND. Astronomy and Astrophysics 527, A76. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201015283

Katz, H., Lelli, F., McGaugh, S. S., Di Cintio, A., Brook, C. B., and Schombert, J. M. (2017). Testing feedback-modified dark matter haloes with galaxy rotation curves: estimation of halo parameters and consistency with ΛCDM scaling relations. Mon. Notices R. Astronomical Soc. 466 (2), 1648–1668. doi:10.1093/mnras/stw3101

Lelli, F., McGaugh, S. S., and Schombert, J. M. (2016). SPARC: mass models for 175 disk galaxies with spitzer photometry and accurate rotation curves. Astronomical J. 152 (6), 157. doi:10.3847/0004-6256/152/6/157

Lin, W., and Chen, D. M. (2021). Comparison of modeling SPARC spiral galaxies’ rotation curves: halo models vs. MOND. Res. Astronomy Astrophysics 21 (11), 271. doi:10.1088/1674-4527/21/11/271

Lovas, S. (2022). Linearity: galaxy formation encounters an unanticipated empirical relation. Mon. Notices R. Astronomical Soc., Letters. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2206.11431

McGaugh, S. S., Lelli, F., and Schombert, J. M. (2016). Radial acceleration relation in rotationally supported galaxies. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117 (20), 201101. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.117.201101

Milgrom, M. (1983). A modification of the Newtonian dynamics as a possible alternative to the hidden mass hypothesis. Astrophysical J. 270, 365–370. doi:10.1086/161130

Rubin, V. C. (2011). An interesting voyage. Annu. Rev. Astronomy Astrophysics 49, 1–28. doi:10.1146/annurev-astro-081710-102545

Keywords: galaxy rotation curves, keplerian velocity, SPARC dataset, velocity correction factor (ω), empirical modeling, rotation curve fitting, dark matter alternatives, MOND

Citation: Flynn DC and Cannaliato J (2025) A new empirical fit to galaxy rotation curves. Front. Astron. Space Sci. 12:1680387. doi: 10.3389/fspas.2025.1680387

Received: 05 August 2025; Accepted: 10 October 2025;

Published: 10 December 2025.

Edited by:

Jirong Mao, Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), ChinaReviewed by:

Hyungsuk Tak, The Pennsylvania State University (PSU), United StatesBrahim Benaissa, Ho Chi Minh City University of Technology, Vietnam

Copyright © 2025 Flynn and Cannaliato. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: David C. Flynn, ZGZseW5uNTY1NkBnbWFpbC5jb20=

David C. Flynn

David C. Flynn Jim Cannaliato

Jim Cannaliato