- Geophysical Institute, College of Natural Sciences and Mathematics, University of Alaska Fairbanks, Fairbanks, AK, United States

Space Weather encompasses multiple elements of the Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) education standards, offering an optimum context for interdisciplinary learning. Because space is inherently interesting to young learners, it presents a unique opportunity to enhance engagement and curiosity in science. Although Space Weather is not typically included in K–5 curricula due to its perceived conceptual complexity, we developed and implemented a 4-week “Northern Lights” curriculum for grades K-5 to introduce physical components at the elementary level. The course introduced concepts spanning from the Sun to Earth and emphasized connections between physical and Earth sciences. Through hands-on, inquiry-based activities, students demonstrated a strong grasp of fundamental principles and were able to relate their learning to real-world phenomena. This paper presents the design, implementation, and outcomes of these activities, highlighting the potential of Space Weather as an accessible and inspiring framework for early STEM education.

1 Introduction

Aurorae are striking visual manifestations of the complex Sun-Earth system and have inspired folklore and cultural narratives across the world (Brekke and Asgair, 1983; Brekke and Asgair, 1994; Akasofu, 2003). As captivating displays of Space Weather, they naturally bridge advanced physical concepts with experiences that are accessible and engaging to broad audiences. In high-latitude regions, aurorae occur commonly enough to be incorporated into elementary science curricula, reinforcing multiple National Science Education Standards (NSES) and Next-Generation Science Standards (NGSS) in areas such as Scientific Inquiry, Physical Science, Earth and Space Science, and Engineering, Technology, and Applications of Science (Board on Science Education et al., 2012; National Research Council, 1996; NGSS Lead States, 2013). In contrast, most U.S.-based students are first introduced to Space Weather concepts only in elective high school courses or later during undergraduate studies (NGSS Lead States, 2013). Given that space and space travel are especially inspiring to children as young as ages 4-7 (BBC Newsround, 2023), integrating Space Weather into earlier stages of science education represents a valuable opportunity for strengthening STEM learning and fostering future recruitment (National Research Council (2012)).

A variety of successful workshops and outreach initiatives introduce Space Weather concepts to students at the elementary level and beyond. In the U.S., resources aligned with national science education standards include the NOAA Space Weather Prediction Center (SWPC) curriculum for grades 7-12 (NOAA Space Weather Prediction Center, 2025), NASA’s Heliophysics Education Activation Team, Space Place, and My NASA Data modules for grades 6-8 and above (NASA Science, 2025), and the University of Colorado Boulder’s Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics (LASP) Space Weather Compendium (University of Colorado Boulder, Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics, 2025), which begins at grades K-5. Internationally, additional valuable resources are offered through agencies and education centres such as, but not limited to, the European Space Agency (European Space Agency, 2025), Canadian Space Agency (Canadian Space Agency, 2025), Royal Observatory Greenwich (Royal Observatory Greenwich, 2025), Japan’s National Institute of Information and Communications Technology (Japan National Institute of Information and Communications Technology, 2025), Australia’s Bureau of Meteorology Space Weather Services (Australian Bureau of Meteorology, Space Weather Services, 2025), the South African National Space Agency Space Weather Centre (South African National Space Agency, 2025), and the Andøya Space Education Centre in Norway (Andøya Space ducation Centre, 2025).

At the University of Alaska Fairbanks (UAF), the Summer Sessions & Lifelong Learning Centre hosts the 365 SMART (Science, Math, Art, Recreation, and Technology) Academy, which is a program that offers enrichment classes geared towards K-12 students (UAF Summer Sessions and Lifelong Learning, 2025). The program consists of semesterly in-person classes offered through a partnership with the university and other educational institutions in the Fairbanks North Star Borough. Drawing from the UAF Museum of the North’s “Learning through Cultural Connections” (UAF GI Education and Outreach Office, 2025) and the UAF Geophysical Institute Education and Outreach Office’s prior experience in co-production of educational resources, a new class called “Northern Lights” was designed and offered to grades 2–5 students in Spring 2023 and 2024 as a part of the SMART 365 Academy. These local resources helped greatly with incorporating students’ own lived experiences in Alaska and integrating Iñupiaq vocabulary into the course curriculum to engage students in place-based learning. This article presents the design, content, and outcomes of a 4-week aurora-focused course for second to fifth-grade students.

2 Course overview and design rationale

The “Northern Lights” course was designed to introduce Space Weather to K-5 students using the standards and practices laid out by the Board on Science Education et al. (2012). The following sections are organized based on the discipline.

2.1 Physical science

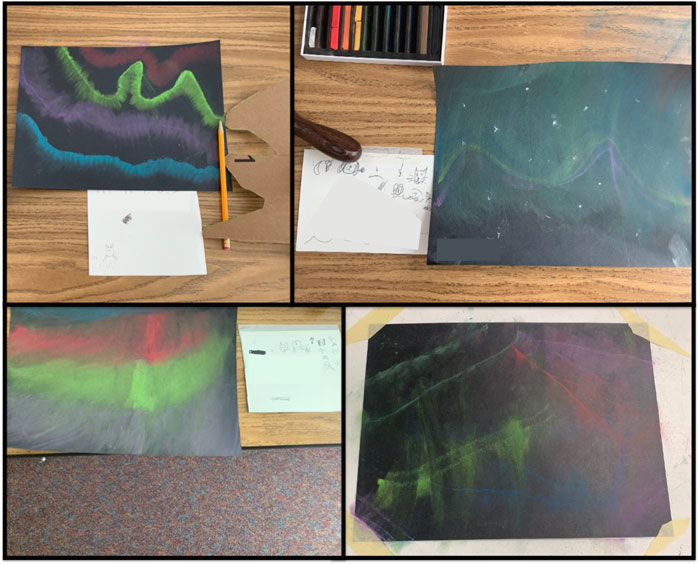

The physical science national standards consist of the following components: motion and stability: forces and interactions; energy; waves and their applications in technologies for information transfer; matter and its interactions. Some of the concepts related to these disciplinary core ideas (DCIs) are properties of objects and materials; position and motion of objects; and light, heat, electricity, and magnetism. The concepts and examples used in the classroom for physical science standards are provided in Table 1. Topics about light, heat, and electricity were extensively discussed throughout the course, with multiple examples from across the Sun-Earth system used to solidify these concepts.

Table 1. The weekly distribution of topics, grade levels, and concepts covered in the Northern Lights class.

2.2 Earth and space science

The Earth and Space Science DCIs for K-5 are Earth’s systems; Earth and human activity; and Earth’s place in the universe. These DCIs can be exemplified by identifying the objects in the sky; differences between day and night, seasons, and weather; and Earth’s materials, resources, and processes. These concepts are used to set the stage for Space Weather discussions in the classroom, during which the solar system is used as the starting point to describe the relative position and motion of planets, specifically the Earth, around the Sun. The details of the Space Weather concepts used for each learning standard are detailed in Table 1.

2.3 Engineering design

The DCIs for Science and Technology education aim to develop a student’s ability to comprehend design and technology, acquire problem-solving skills, and distinguish between natural and human-made objects. Although the class had direct examples and discussions of scientific discoveries and how scientists and researchers approach a problem, the Engineering Design component was primarily incorporated through hands-on activities in the classroom. The concepts adopted in the classroom for Engineering Design are provided in more detail in Table 1.

2.4 Science in personal and social perspectives and history of science

Considering the Space Weather impacts, especially in high-latitude areas more prone to regular and more visible outcomes like aurora, the class provided a great opportunity to discuss science from a personal and social perspective for students. The students were encouraged to discuss the conditions under which they observed aurora, what other changes they noticed when aurora was present, and what they heard about aurora from their families and friends. The class discussions included brainstorming about how aurora was first discovered, what people may have thought about it at the time, and how it impacted their daily lives. The students were further encouraged to use the UAF Geophysical Institute’s resources at home, for example, the “Aurora Forecast” website, to plan for aurora forecasting with their parents. In addition, the UAF Cultural Connections website was offered as a resource to learn more about aurora in Iñupiaq culture through interviews with elders to promote place-based learning.

2.5 Science as inquiry

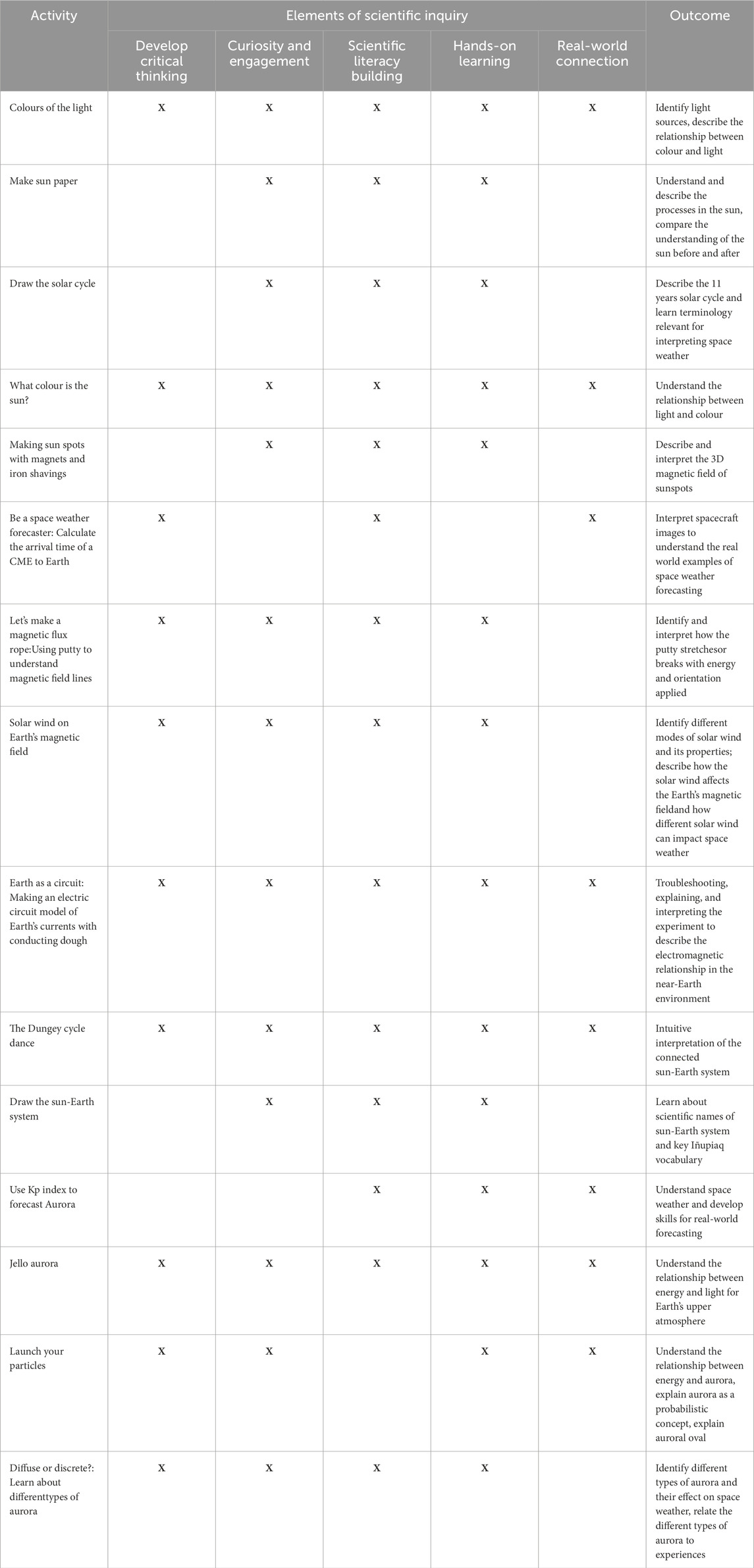

Science as Inquiry is a fundamental standard for STEM Education as it is directly related to developing critical thinking and problem-solving skills while encouraging curiosity and self-driven literacy building. The K-5 national standards include developing abilities for scientific inquiry and understanding scientific concepts with evidentiary support. Therefore, the class included a review of previous lectures, guiding discussions, hands-on experiments, their troubleshooting and interpretations, games, and tests. The activities specifically designed for elements of scientific inquiry and their outcomes are detailed in Table 2.

3 Weekly curriculum breakdown

The ‘Northern Lights’ class was offered as four weekly, in-person modules. Each weekly module was 2 h long. The class sizes ranged from two to 4, depending on the attendance. The classroom was designed in a workshop format, where students could move around but also follow the presentation materials and videos. Each week was designed around a topic that introduces the Sun-Earth system, targeting the national standards laid out in Section 2. The following subsections are designed to introduce the topic focus, learning objectives, in-class activities, Iñupiaq vocabulary taught, key concepts, and assessment questions.

3.1 Week 1: the sun

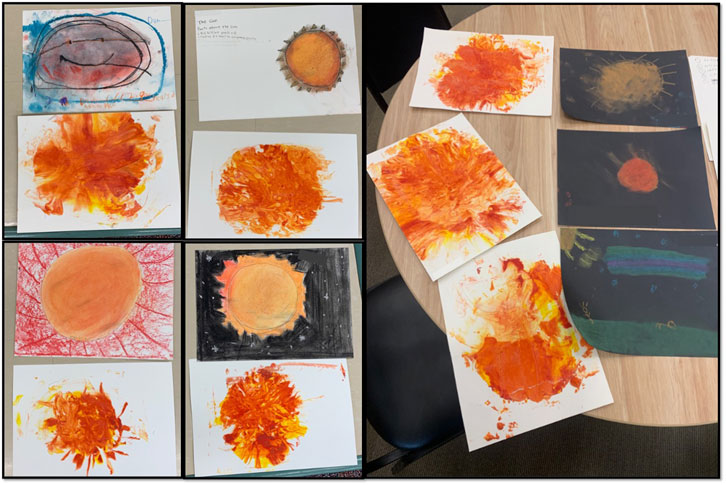

The first class introduces the Sun and its importance for Space Weather. Students learn that the Sun is responsible for the Space Weather at Earth. Students learn the Iñupiaq names for the Sun, mazaq (Northern Seward Peninsula dialect) and siqiñiq (North Slope dialect), using the resources provided at the UAF Cultural Connections Website. Students are asked to discuss the Sun’s properties and its place in the solar system. Class activities start with students using black drawing paper and chalk crayons to draw the Sun. Students comment on what colour they picked to fill in the Sun and why. The Sun’s rotation around itself (i.e., differential rotation) and how it differs from a solid body rotation are discussed using examples. Satellite images of the Sun are displayed, and how it differs from student drawings is discussed as a classroom activity. The student drawings from Week one can be seen in Figure 1.

3.1.1 Concepts

The key concepts for the class are: Sun’s rotation, sunspots, Sun’s layers and its atmosphere, solar light spectrum.

3.1.2 Activities and experiments

• Drawing the Sun.

• What Colour is the Sun? by Douma (2008).

• Make Sun paper by NASA Space Place by NASA SpacePlace (2025b)

3.1.3 Learning objectives

• The Sun is made out of very hot gas called plasma.

• The Sun’s light contains all the colours.

• The Sun rotates around itself.

• The Sun’s surface is grainy and active.

3.1.4 Assessment and reflection questions

• What do you know about the Sun?

• What do you know about our Solar System?

• What colour is the Sun?

• How do we observe the Sun?

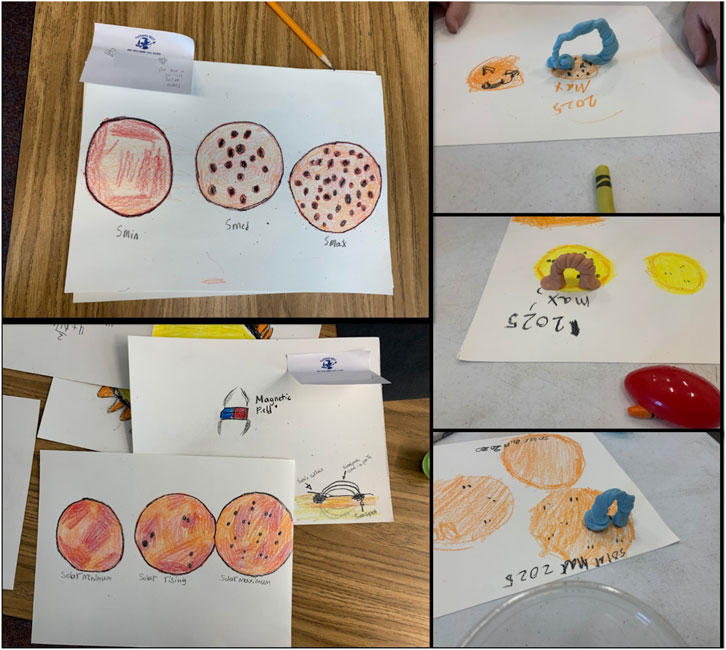

3.2 Week 2: the solar activity

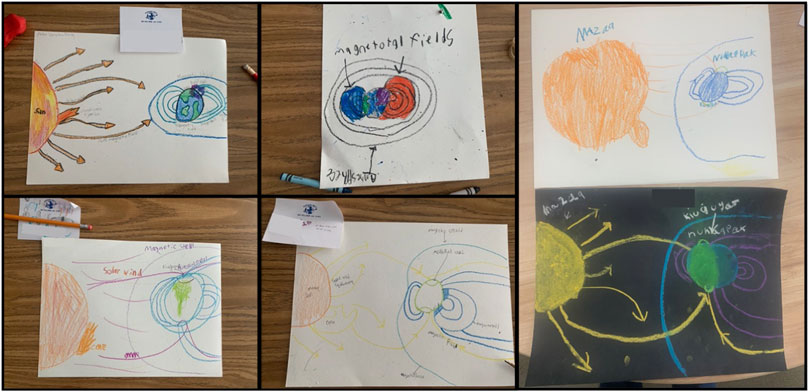

The second class introduces solar activity and its importance for Space Weather. Students learn that there are magnetic sunspots at the surface of the Sun, and they determine other irregular Space Weather events such as solar flares, coronal mass ejections (CMEs), and coronal holes. Students also learn about the regular Space Weather events that occur as a result of the processes at the Sun, such as the solar wind. Class activities include making 3D sunspots from iron shavings and magnets, drawing the solar cycle, stretching putties to understand magnetic field lines that are associated with sunspots, and eventually flares and coronal mass ejections. Students are introduced to coronographs and evaluate the arrival time of CMEs to Earth. They are introduced to the concept of Space Weather forecasting and make comparisons between weather and space weather. The student activities from Week two can be seen in Figure 2.

Figure 2. The students drew solar activity in 2023 (left) and in 2024 (right). On the right, students also made flux ropes emerging from the sunspots.

3.2.1 Concepts

The key concepts of this class are: magnetism, the Sun’s magnetic field, magnetic reconnection, sunspots, solar cycle, active regions, solar flares, coronal holes, coronal mass ejections, solar wind, and Space Weather forecasting.

3.2.2 Activities and experiments

• Let’s make sun spotsIngredients: Iron shavings, a plastic cup, and round magnets.Directions: Place round magnets inside the cup, and place the cup close to the iron shavings to attract them as shown in the figure.

• Paint the Solar Cycle and Label the Solar Cycle Phase.

• Let’s make a magnetic flux rope.

• Be a Space Weather Forecaster by NASA HEAT (2023).

3.2.3 Learning objectives

• The sunspots are signs of solar activity.

• The Sun has an 11-year cycle.

• When sunspots get tangled close to the Sun, they create solar flares.

• The magnetic reconnection gives rise to plasma bubbles called coronal mass ejections.

• There is a constant wind coming out of the Sun, called solar wind.

3.2.4 Assessment and reflection questions

• What is a weather forecast? What is “bad” weather?

• What is Space Weather? Do you check the Space Weather forecast?

3.3 Week 3: The near earth environment

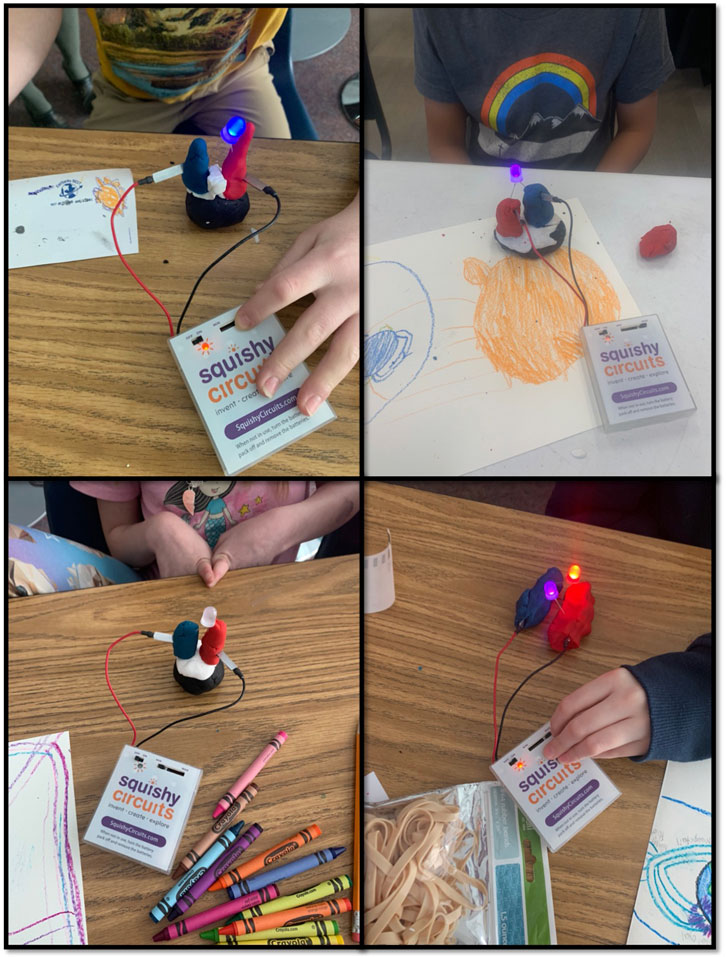

The third class introduces the near-Earth environment, its importance for humans, and the physical processes that govern the properties of this environment. Students interpret the near-Earth environment using electromagnetic terminology and understand that it is a changing system. They are introduced to Earth’s magnetic field using simple bar magnet analogies and hands-on experiments. They begin to learn how different regions of the Earth respond differently to Space Weather due to its dipole configuration. They are introduced to the relationship between electricity and magnetism through short video lectures. Students learn the Iñupiaq name for the Earth, Nunaqpak. Class activities include understanding solar wind impact on Earth’s magnetic field, drawing the Sun-Earth system, understanding magnetic reconnection and cyclic motion of magnetic field lines around the Earth, and the electric currents that form a circuit around the Earth and give rise to aurora. They also learn about the Kp index and how to forecast aurora. The student activities from Week three can be seen in Figures 3, 4.

3.3.1 Concepts

The key concepts of this class are: electricity, electric circuits, electromagnetism, the Earth’s magnetic field, magnetosphere, auroral oval, solar wind - Earth interactions, mainly the cyclic circulation of the plasma around the Earth’s magnetosphere due to solar wind forcing known as the Dungey cycle (Dungey, 1961), Earth’s current systems, geomagnetic storms, Kp index.

3.3.2 Activities and experiments

• Solar wind on Earth’s magnetic fieldIngredients: Hair dryer with multiple settings, plastic bag.Directions: Fill the plastic bag with air, using slow and fast settings. Comment on the changes.

• Draw the Sun-Earth system.

• The Dungey Cycle danceCross arms in the front to mimic reconnection and move arms backwards to show the dayside-to-nightside transition of magnetic field lines. Comment on how arms connect to shoulders as an analogy for the auroral oval.

• Earth as a circuitIngredients: Light bulbs, cables, conductive and insulative dough, and a battery.Directions: Make a round sphere from conductive dough (black), add an insulative layer to mimic the atmosphere (white), add red and blue doughs as elongated cylinders to mimic Birkeland currents, insert one end of cable to red and another end of the cable to blue dough, connect cables to the battery, add a lamp between red and blue dough to show Earth as a circuit system.

• Use the Kp index to forecast and find a good day to see the aurora in the next 2 weeks.

3.3.3 Learning objectives

• Earth has a magnetic shield that protects us from the bad Space Weather.

• Particles move around Earth’s magnetosphere, creating electric currents.

• Electric currents flow along magnetic field lines into and out of the polar regions, producing auroral emissions.

• Kp index is used to forecast Space Weather.

3.3.4 Assessment and reflection questions

• What is “bad” Space Weather?

• What happens at Earth during a storm? What happens at Earth during a solar storm? What happens at Earth during a substorm?

3.4 Week 4: The ionosphere and aurorae

The fourth and final class focuses on Earth’s ionosphere, an ionized region of the Earth’s atmosphere, and how aurora, as students know it, is generated. They learn about different gases in Earth’s atmosphere and how they interact with particles from the near-Earth environment that travel along the magnetic field lines into the auroral oval. They learn about particles and their different energies as a fundamental concept, resulting in the differing colours and shapes of aurora through experiments. Students are introduced to the Iñupiaq names for the aurora, kiuġiyaq (Northern Seward Peninsula dialect) and kiuġuyat (North Slope dialect), via the UAF Cultural Connections Website. The students were also introduced to all-sky cameras and how we use them to take photos of aurora at different wavelengths (colours) corresponding to different heights. Class activities include pushing marbles into different regions of the jello aurora to understand the relationship between different altitudes, energies, and aurora colours; launching particles (marshmallows) into an auroral oval with slingshots, playing an identification game using different shapes for aurora, and drawing aurora with chalks. At the end of the class, students are able to identify the properties of different shapes and colours of aurora. The class wraps up with an overall assessment of the class and a reflection. The student activities from Week four can be seen in Figures 5–7.

Figure 5. Students complete their Jello ionospheres and push marbles to different depths to create different colours of aurora.

3.4.1 Concepts

The key concepts of this class are: Earth’s atmosphere, atmospheric gases, ionosphere, and the colours and shapes of aurora.

3.4.2 Activities and experiments

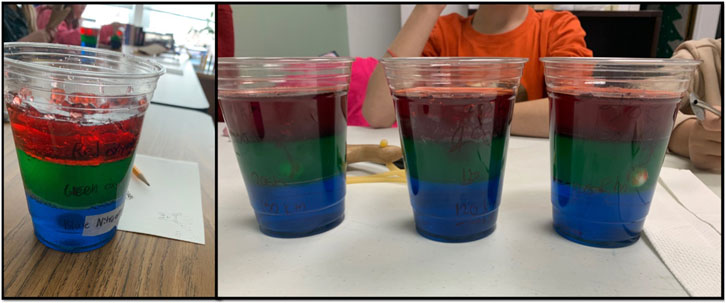

• Jello AuroraIngredients: Plastic cup, three different colours (red, green, blue) jelly, black marker.Directions: Prepare in advance. Layer red, green, and blue jellies to create a jelly aurora in layers. Use the marker to mark altitude and dominant gas for each colour. Beware of allergens and dietary preferences.

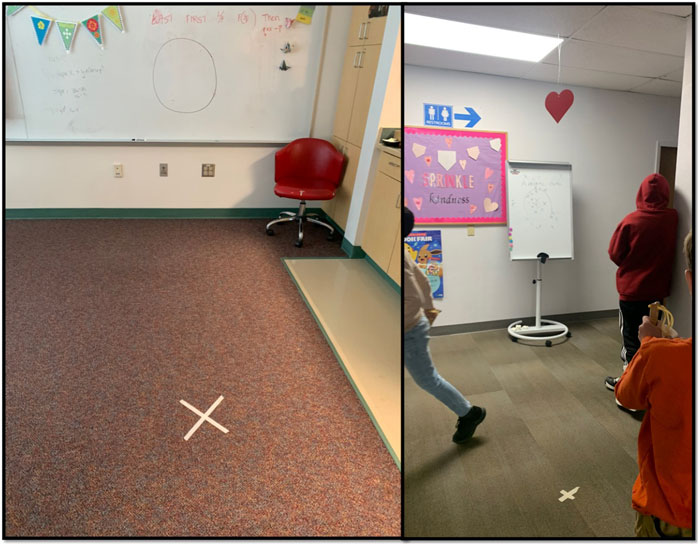

• Launch your auroral particlesIngredients: Marshmallows, slingshot, pen, tape, paper or whiteboard.Directions: Mark an X point on the floor with tape. Draw an oval to the whiteboard. Have students aim marshmallows with slingshots into the auroral oval. Mark the target with a pen. Beware of allergens and dietary preferences.

• How aurora gets different coloursIngredients: Jello aurora, marbles, thick straws.Directions: Have students push marbles into different colours of jelly using straws. Comment on the most difficult colour. Comment on energy.

• Diffuse or discrete?Introduce diffuse and discrete aurora, show images and ask students what type of aurora they see. Have them discuss their answers.

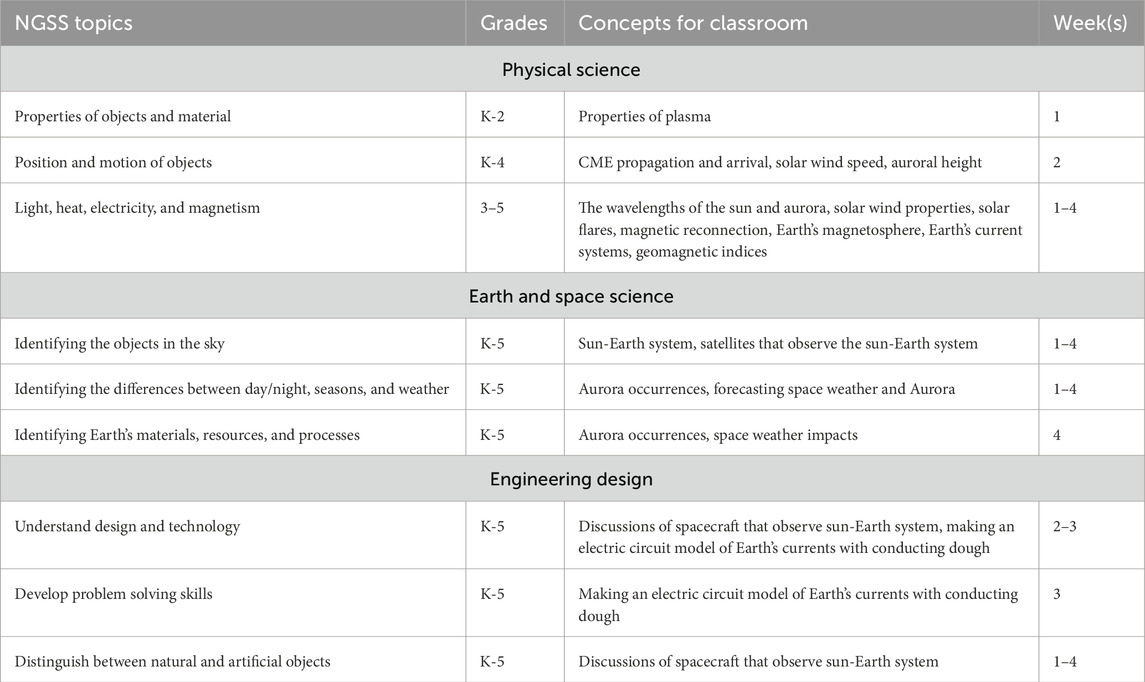

• Make pastel aurora by NASA Space Place (2025a).

3.4.3 Learning objectives

• Earth’s atmosphere has different layers.

• The ionosphere is the charged layer of the atmosphere.

• There can be different shapes and colours of aurora.

3.4.4 Assessment and reflection questions

• How many colours of aurora are there?

• How many shapes of aurora are there?

• Where do aurorae occur?

4 Evaluation and feedback

The SMART 365 classes often only award a graduation certificate and do not have an official assessment framework in place. Therefore, to assess student understanding, in-class activities such as discussions, games, and pre- and post-lecture drawings were used. Outcomes listed in Table 2 were posed as reflection questions at the beginning and end of lectures, while remaining questions and brainstorming sessions took place in tandem with the hands-on class exercises. Below are some individual examples from classes that show students’ understanding of the class and exercises.

4.1 Make sun paper activity

During the first class, students were asked to draw the Sun using crayons and white or black drawing paper. Most of the students draw the Sun as a composite yellow-orange filled circle with rays extending out as shown in Figure 1. After the “Make Sun Paper” activity was complete, students were able to comment on the different colours that make up the Sun and its dynamic structure. In the following classes, some students opted to use orange, yellow, and red to draw the Sun as a heterogeneous structure without being prompted, as can be seen in Figure 3, carrying their understanding from the first lecture throughout the course.

4.2 Drawing the solar cycle

In the second week of the class, the students were able to carry their understanding from Week one that the Sun was not one single colour. Most of them used red, orange, and yellow to colour in the circles as shown in Figure 2. They were able to represent sunspots in pairs or clusters and accurately name the different phases of the solar cycle and the number of sunspots. In year 2, the students also places their magnetic flux rope putties on top of the sunspots indicating their understanding of the magnetic field of sunspots.

4.3 Draw the sun-earth system

During this activity, students were asked to draw the Sun-Earth connectivity however they wished and had a reference image shown. They have connected the structures in the Sun all the way to the Earth. Some of them were able to differentiate between solar flares, coronal mass ejections, and solar wind in their drawings, which is already quite advanced. On Earth, students were able to demonstrate the dipole magnetic field, magnetopause as a shield, and the auroral oval. Most students successfully showed the compression of the magnetosphere on the dayside and the stretching of the magnetotail on the nightside. Some students even added the Iñupiaq vocabulary on their drawings. The drawings from these activities are shown in Figure 3.

4.4 Earth as a circuit

During this activity, the students were asked to make a conductive ball to represent the Earth and an insulated layer to represent the upper Atmosphere. These features are shown with the black and white doughs in Figure 4. The students were then asked to make a red and a blue conductor to represent electric current systems (Birkeland currents) that flow along magnetic field lines and connect the solar wind to the Earth (Birkeland (1908); Egeland (2009)). They picked lamps with the colour of their choice. If the red and blue conductor doughs are connected, the system short short-circuited, and the lamps do not give off light. The students had to troubleshoot components of this circuit to have their lamps illuminate. This reinforced their basic knowledge of electricity and circuits. The students were then able to use the lamps as an analogue for the aurora, describing how connected and externally driven the current system was.

4.5 Jello aurora

The jello aurora activity aims to demonstrate the relationship between incoming particle energy and the observed colours of aurora. Prior to the class, the students discussed having mostly seen green aurora in Alaska and they only knew of other colours from photographs. The students were then given a reference image with the names of dominant atmospheric gases and their respective altitudes. They used permanent markers to label the atmospheric components. Students were then given marbles and straws. They were asked to push the marble into the red jelly layer to create a red aurora. After the task was completed, they were asked to push the marble further into the green jelly. They started to notice that more effort was required to push the marble to deeper layers. The final task was to push the marble into the blue jelly. As a result of this activity, students compared different colours and how much energy was needed to push the marble into them. When asked which colour of aurora would then require more energy, they were all able to make the connection that blue aurora was more energetic, followed by green and red. The jello aurora activity is shown in Figure 5.

4.6 Launch your particles

For this activity, the students were given a slingshot and large marshmallows. The goal was described as standing on the x-line, where reconnection occurs, and aiming at the oval on the whiteboard, which represented the auroral oval. Students took turns launching marshmallows into the auroral oval, and the instructor marked the locations where the marshmallows landed. Students were then asked to comment on how fast or slow their particles were. They were asked to draw connections with the impact speed and the marbles that they pushed into the different colours of jellies, and to comment on what colour of aurora each marshmallow hit would generate. They also understood that not all particles would land on the auroral oval. Later on, the students were asked to move along the x-line and launch marshmallows without stopping. The instructor marked the locations where the marshmallows landed on the whiteboard. The instructor then connected these points. The students were asked to comment on what the connected lines looked like, and most of them were able to make connections with the ridged shape of aurora, arriving at an understanding that the X-line was not a single stationary point. The results of this activity is shown in Figure 6. As a result of this activity, students shared how the resulting drawings looked more similar to their observations of the aurora.

4.7 Pastel aurora

The final activity was to make a pastel aurora. Students were not given a reference image, however, they were able to accurately represent different colours at different heights, diffuse and discrete features and even colours mentioned in passing. The drawings from this activity is shown in Figure 7

At the end of the class, all parents were invited to the classroom, and students got their certificates. They showed their parents what they had learnt about aurora in the last class, and each of them explained their experiments and drawings and discussed Space Weather from the Sun to Earth. One noteworthy quote from a student, who was 11 years old, was that “Making aurora is hard”.

To assess the students’ understanding of the material and the learning outcomes, we used discussions, games, and pre- and post-lecture drawings. Outcomes listed in Table 2 were posed as discussion questions at the end of the classes and revisited at the beginning of new classes. Students.

5 Discussion

As an enrichment course, the “Northern Lights” class brought together students from diverse backgrounds and varying academic levels, creating a heterogeneous learning environment. The course was offered at a partner institution rather than a traditional classroom, which contributed to a novel learning setting and reduced distractions, as students did not already know one another. In-class observations also indicated that young learners have relatively short attention spans. Therefore, it is recommended not to use traditional slideshows and educational videos longer than 1–2 min. Additionally, students responded positively to hands-on activities and collaborative group work, suggesting that future iterations of the course could incorporate more cooperative elements.

Another key consideration in course design is participant safety and accessibility. Materials such as food products, balloons, putties, or slingshots containing latex should be avoided when allergies are present. We recommend that instructors survey for allergies prior to the course and replace experiment materials where possible. The course was also showcased to instructors during the ‘Innovative Differentiated Exploration Activities in Space Science (IDEAS) NASA in the Classroom Educator Professional Development Workshop on Space Science Activities & Universal Design,’ highlighting best practices for inclusive teaching. The participating teachers’ experiences from traditional classrooms will be invaluable for future iterations of this course. As more feedback becomes available, we will strive to accommodate learners with disabilities and ensure that the course is accessible to all students.

A unique advantage for the “Northern Lights” class was that most students were already very familiar with aurora. However, across the globe, most students are familiar with space through popular culture. Incorporating references to cartoons, movies, or books helps students relate more to the presented material. Some cartoons, such as “Frozen” (Buck and Lee, 2013) and “Molly of Denali” (Gillim and Waugh, 2019), can provide opportunities to address aurora through popular culture elements in the classrooms. This strategy is especially valuable when adapting the course to regions where aurorae are rarely visible. The class, offered in February and March in Fairbanks, was limited by short daylight hours and cold temperatures, but in other locations or seasons, tools such as sundials and telescopes could be used for hands-on activities on solar topics. Leveraging place-based tools, as well as historical and cultural references, where possible, will further reinforce the real-world connections, helping students internalize these complex concepts.

Finally, what empowered students the most was the opportunity for trial-and-error during experiments. Allowing sufficient time for them to explore independently, collaborate with peers, and solve problems within groups significantly increased their self-confidence. Activities such as making forecasts, discussing them with family members, and dedicating time at the end of each session for reflection helped students envision themselves as future scientists.

6 Conclusion

As a part of the SMART 365 program, we have developed the “Northern Lights” course, which aims to incorporate Space Weather as a unifying theme for K-5 STEM education within the cultural and geographical framework of Alaska. As aurorae are a commonly visible phenomenon in Alaska, they provided a natural entry point to engage students with hands-on activities that address various science topics aligned with the National Science Education Standards and the Next-Generation Science Standards. Through the development of this course, we have found that multiple physical concepts can be effectively addressed within the Space Weather framework, ranging from matter to electromagnetism. Moreover, the immediate impacts of Space Weather on infrastructure and satellites provide a natural link to Science and Technology standards, helping students make meaningful real-world connections. This approach not only fosters curiosity and inquiry but also scaffolds more advanced science topics by building a foundational understanding. Finally, given children’s strong interest in space, incorporating Space Weather into K-5 education offers a powerful opportunity to inspire young learners and strengthen the future STEM pipeline.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the minor(s) legal guardian/next of kin for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

DO: Visualization, Writing – original draft, Resources, Investigation, Methodology, Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The authors declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The material required for the class was acquired through the University of Alaska Fund-1 and Summer Sessions, and Lifelong Learning financial support.

Acknowledgements

DSO gratefully acknowledges Kalee Meurlott from the Geophysical Institute Education and Outreach Team for sharing the Cultural Connections resources and the UAF Summer Sessions and Lifelong Learning for initiating this class. DSO expresses special gratitude to James A. Slavin (Dungey cycle dance), Daniel J. Price (Launch your particles), and Andrés Muñoz-Jaramillo (Let’s make a magnetic flux rope) for conversations and demos that inspired material development.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Andøya Space Education Centre (2025). Educational programs. Available online at: https://www.andoyaspace.no/education (Accessed July 01, 2025).

Australian Bureau of Meteorology, Space Weather Services (2025). Education resources. Available online at: https://www.sws.bom.gov.au/Education (Accessed July 01, 2025).

BBC Newsround (2023). Space is the Most inspiring science topic for kids aged 4–7. Available online at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/newsround/69091514 (Accessed July 01, 2025).

Birkeland, K. (1908). “The Norwegian Aurora polaris expedition 1902-1903,”, 1. Oslo: H. Aschehoug and Co.

Board on Science Education (2012). “Division of behavioral and social sciences and education, committee on conceptual framework for the new K-12 science education standards, and national research council,” in A framework for K-12 science education. Washington, D.C., DC: National Academies Press.

Brekke, A., and Egeland, A. (1983). The northern lights from mythology to space research. Heidelberg, Germany: Grøndahl Dreyer. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-69106-5

Brekke, A., and Egeland, A. (1994). The northern lights their heritage and science. Oslo: Grøndahl Dreyer.

Canadian Space Agency (2025). Learning and activities. Available online at: https://www.asc-csa.gc.ca/eng/educators/default.asp (Accessed July 01, 2025).

Douma, M. (2008). Causes of Color: Why does the aurora glow? Available online at: https://www.webexhibits.org/causesofcolor/14F.html (Accessed October 13, 2025).

Dungey, J. W. (1961). Interplanetary magnetic field and the auroral zones. Phys. Rev. Lett. 6, 47–48. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.6.47

Egeland, A. (2009). Kristian birkeland: the first space scientist. J. Atmos. Solar-Terrestrial Phys. 71, 1749–1755. doi:10.1016/j.jastp.2009.09.008

European Space Agency (2025). Education resources. Available online at: https://www.esa.int/Education (Accessed July 01, 2025).

Gillim, D., and Waugh, K. (2019). Molly of Denali GBH Kids and Atomic Cartoons / PBS Kids. United States / Canada: Television series.

Japan National Institute of Information and Communications Technology (2025). Space weather education and outreach. Available online at: https://swc.nict.go.jp (Accessed July 01, 2025).

NASA HEAT (2023). Coronal mass ejection science lesson plan. Available online at: https://science.nasa.gov/learn/heat/resource/coronal-mass-ejection-science-lesson-plan/ (Accessed September 01, 2025).

NASA Science (2025). Heat: framework for heliophysics education. Available online at: https://science.nasa.gov/learn/heat/(Accessed July 01, 2025).

NASA Space Place (2025a). Make a pastel Aurora. Available online at: https://spaceplace.nasa.gov/pastel-aurora/en/(Accessed July 01, 2025).

NASA Space Place (2025b). Make sun paper. Available online at: https://spaceplace.nasa.gov/sun-paper/en/(Accessed July 01, 2025).

National Research Council (1996). National science education standards. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

National Research Council (2012). A framework for K–12 science education: practices, crosscutting concepts, and core ideas. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

NGSS Lead States (2013). Next generation science standards: for states, by states. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

NOAA Space Weather Prediction Center (2025). Space weather curriculum for grades 7–12. Available online at: https://www.swpc.noaa.gov/education-and-outreach (Accessed July 01, 2025).

Royal Observatory Greenwich (2025). Education and learning resources. Available online at: https://www.rmg.co.uk/schools (Accessed July 01, 2025).

South African National Space Agency (2025). Space weather centre education. Available online at: https://spaceweather.sansa.org.za (Accessed July 01, 2025).

UAF GI Education and Outreach Office (2025). Cultural connections to alaska science. Available online at: https://culturalconnections.gi.alaska.edu/(Accessed July 01, 2025).

UAF Summer Sessions and Lifelong Learning (2025). Uaf summer sessions and lifelong learning courses. Available online at: https://www.uaf.edu/summer/(Accessed July 01, 2025).

University of Colorado Boulder, Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics (2025). Space weather compendium. Available online at: https://lasp.colorado.edu/education (Accessed July 01, 2025).

Keywords: space weather, hands-on learning, northern lights, stem education, K-5 education

Citation: Ozturk DS (2025) Integrating Space Weather into K-5 STEM education through hands-on learning. Front. Astron. Space Sci. 12:1723676. doi: 10.3389/fspas.2025.1723676

Received: 12 October 2025; Accepted: 11 November 2025;

Published: 05 December 2025.

Edited by:

Patricia H Reiff, Rice University, United StatesReviewed by:

Silvia Casu, National Institute of Astrophysics (INAF), ItalyPhilip Valek, Southwest Research Institute (SwRI), United States

Copyright © 2025 Ozturk. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Dogacan Su Ozturk, ZHNvenR1cmtAYWxhc2thLmVkdQ==

Dogacan Su Ozturk

Dogacan Su Ozturk