- 1Department of Infectious Diseases, Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University, Wuhan, China

- 2Wuhan Research Center for Infectious Diseases and Cancer, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, Wuhan, China

- 3Department of Pharmacy, Hubei No.3 People’s Hospital of Jianghan University, Wuhan, China

- 4Department of Pathology, Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University, Wuhan, China

- 5Department of Pathology, School of Basic Medical Sciences, Wuhan University, Wuhan, China

- 6Department of Nosocomial Infection Management, Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University, Wuhan, China

- 7Hubei Engineering Center for Infectious Disease Prevention, Control and Treatment, Wuhan, China

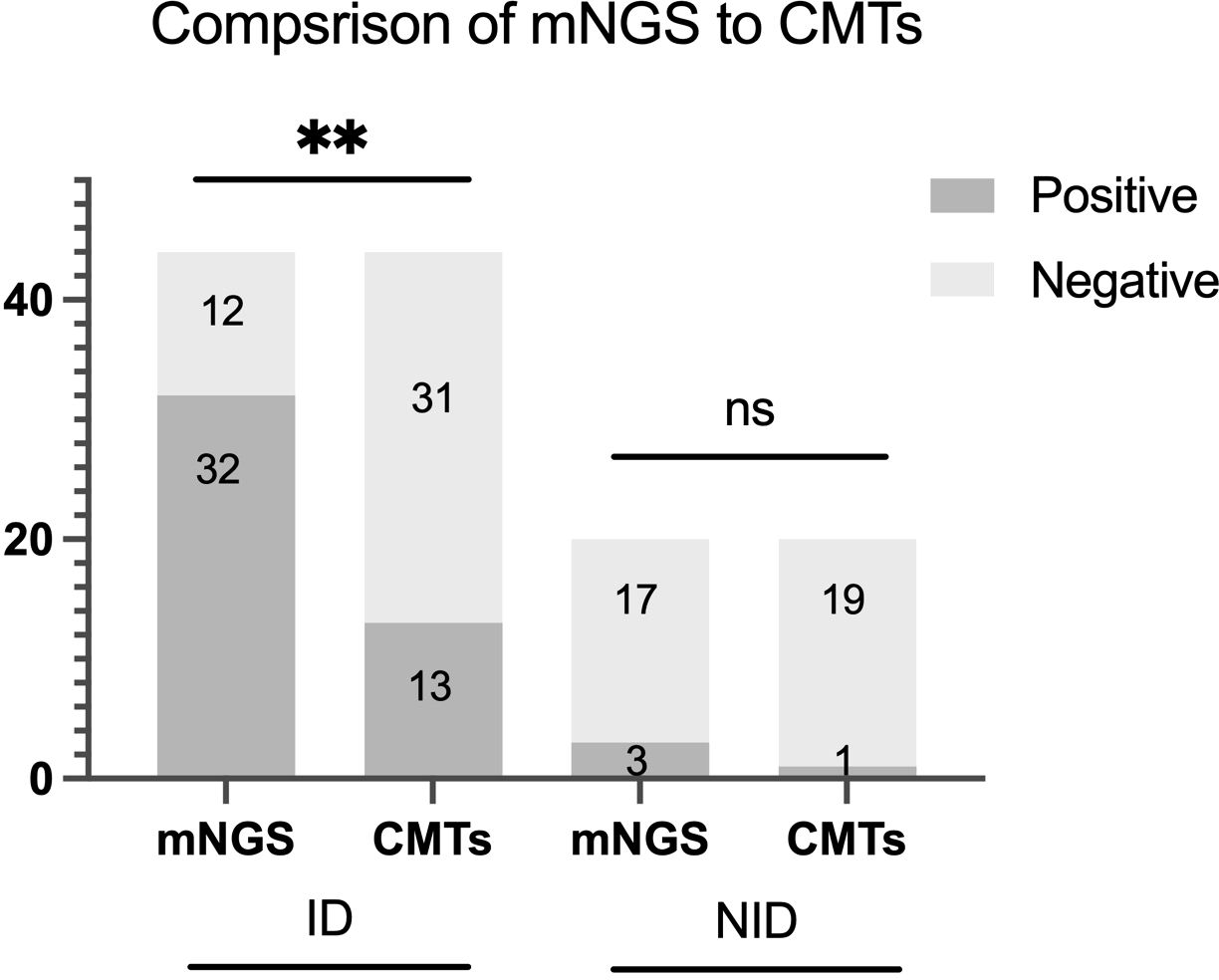

Metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) was suggested to potentially replace traditional microbiological methods because of its comprehensiveness. However, the diagnostic utility of mNGS for tissue hasn’t been fully explored, especially for patient with HIV infection. HIV-positive and negative patients with suspected infectious diseases who performed tissue mNGS and conventional microbiological tests (CMTs) were retrospectively enrolled between October, 2020 and May 2024. The microbial spectrum of tissue mNGS and CMTs was analyzed, and the diagnostic accuracy and consistency of mNGS and CMTs for tissue were compared. The related factors of positive rate of mNGS was analyzed. Of 70 patients with suspected infectious diseases, 44 cases were confirmed with the infectious diseases. Among 44 patients with infectious diseases, aerobic bacteria (36.4%) was the most common detected pathogen, followed by mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB, 18.2%), non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM, 13.6%) and fungus (11.4%). The sensitivity of tissue mNGS (72.7%, 95%CI 56.9%-84.5%) was significantly higher than that that in tissue CMTs (29.5%, 95%CI 17.2%-45.4%) (p<0.001), but the specificity was not statistically significant(P = 0.656). mNGS demonstrated higher detection rates than CMTs in the case with single microbial infections (70.0% vs. 30.0%; p<0.01). For the case with multiple microbial infections, the detection rates of mNGS and CMTs was 100.0% and 25.5% (p=1.000), respectively. Both positive mNGS and CMTs were observed in 22.7% patients with infectious diseases, and sole positive mNGS and sole positive CMTs were observed in 50.0% and 6.8% patients, respectively. There were no statistically differences in age, gender, HIV infection, PCT levels, neutrophil counts, CD4+ lymphocyte count and antibiotic exposure between mNGS positive and mNGS negative groups (P > 0.05). Tissue mNGS could provide a higher sensitivity, more robust and broader method for pathogen identification by comparison with CMTs. However, CMTs shouldn’t be ignored since the low consistency between CMTs and mNGS.

Introduction

The expanding spectrum of pathogenic microorganisms and the rising incidence of challenging-to-diagnose infections have significantly complicated etiological identification in clinical practice. The conventional microbiological tests(CMTs), including staining, culture, and polymerase chain reaction (PCR), etc, currently fail to detect pathogens in up to 60% of infectious disease cases (Schlaberg et al., 2017). Such diagnostic delays critically impede timely antimicrobial stewardship, potentially exacerbating patient outcomes.

Metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) has emerged as a transformative diagnostic paradigm, offering distinct advantages over conventional approaches. By enabling hypothesis-free detection of all microbial genetic material (bacteria, virus, fungus, and parasite) within 24–48 hours, this high-throughput technology demonstrates particular utility in complex infection scenarios (Miao et al., 2018; Qian et al., 2020; Duan et al., 2021). While existing validation studies have primarily focused on liquid biospecimens (blood, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, cerebrospinal fluid, etc) or single tissue samples (Miller et al., 2019; Jin et al., 2022; Sun et al., 2022; Dong et al., 2024), a critical knowledge gap persists regarding mNGS performance in a such large-scale investigation for diverse tissue samples.

To address this unmet need, we conducted a study to investigate the diagnostic accuracy and consistency of mNGS and CMTs in the tissue sample. Our findings establish a reference for optimizing infection diagnosis and antimicrobial decision-making in scenarios where conventional diagnostics prove inadequate.

Methods

Study participants

The hospitalized patients with suspected infectious diseases in Zhongnan Hospital who performed tissue mNGS and CMTs at the same time were retrospectively enrolled from October 2020 to May 2024. The inclusion criteria included: 1) clinical evidences of infectious diseases existed, including fever, elevated white blood cell (WBC) count and/or elevated serum inflammatory markers; 2) both mNGS and CMTs (including staining, culture, PCR, Geen/Xpert, etc) of tissue were performed during hospitalization.

Data collection

Clinical data were retrospectively collected from the medical records of Zhongnan Hospital. These following data were extracted: age, gender, HIV infection status, collection date, type of tissue sample, antibiotic use within 3 months, immunosuppressive therapy (glucocorticoids and immunosuppressants) within 3 months, lymphocyte count, CMTs and mNGS results of tissue samples.

Positive criteria of tissue mNGS

The criteria for the positive result of tissue mNGS referred to previous studies (Miao et al., 2018; Tan et al., 2023; Chen et al., 2024; Zou et al., 2024): (1) Bacteria (excluding mycobacteria), viruses, and parasites: mNGS identified a microbe at the species level with a coverage rate that was 10-fold greater than that of any other microbes. (2) Fungi: mNGS identified a microbe at the species level with a coverage rate that was 5-fold higher than that of any other fungus, attributed to its low biomass during DNA extraction. (3) Mycobacteria: Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB) was deemed positive when at least one read was mapped to either the species or genus level, owing to the challenges associated with DNA extraction and the low risk of contamination. Non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) were classified as positive when the number of mapping reads (at the genus or species level) ranked among the top 10 in the bacterial list, reflecting the balance between hospital-to-laboratory environmental contamination and low yield rates. (4) The identification of pathogenicity is based on the patient’s clinical manifestations, immune status, underlying diseases, imaging results, mNGS findings, other auxiliary examinations, response to antibiotic treatment, and the assessments of clinical experts.

CMTs methods

1.Staining Methods: Gram staining for bacteria (aerobic/anaerobic) and fungal hyphae; Acid-fast staining (Ziehl-Neelsen) for mycobacteria (MTB/NTM); Gomori methenamine silver (GMS) and Periodic Acid-Schiff (PAS) staining for fungi; Histopathological examination (H&E staining) for tissue architecture assessment. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) employed pathogen-specific monoclonal antibodies on tissue sections via automated staining (Leica Bond RX; polymer-HRP/DAB). 2.Culture Techniques: Aerobic cultures: Blood agar and MacConkey agar incubated at 35°C for 48–72 hours; Anaerobic cultures: Brucella agar with vitamin K1/hemin, incubated anaerobically for 5–7 days; Mycobacterial cultures: Löwenstein-Jensen medium and MGIT 960 system (Becton Dickinson), incubated for 6–8 weeks. Fungal cultures: Sabouraud dextrose agar incubated at 30°C for 4 weeks. 3. Molecular Assays: PCR Targets: 16S rRNA gene for bacteria, ITS for fungi, and rpoB gene for MTB/NTM. GeneXpert MTB/RIF Assay: For MTB detection and rifampin resistance screening.

Statistical analysis

SPSS 27.0 and GraphPad Prism 10.0 were used for the statistical analyses and plotting. Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to evaluate whether the measurement data conformed to the normal distribution. Continuous variables that conformed to the normal distribution were analyzed by group t-test, and vice were analyzed by non-parametric rank sum test. Comparative analysis was conducted by Pearson χ2 test. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Ethics

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University (2024310K).

Results

Patients’ characteristics

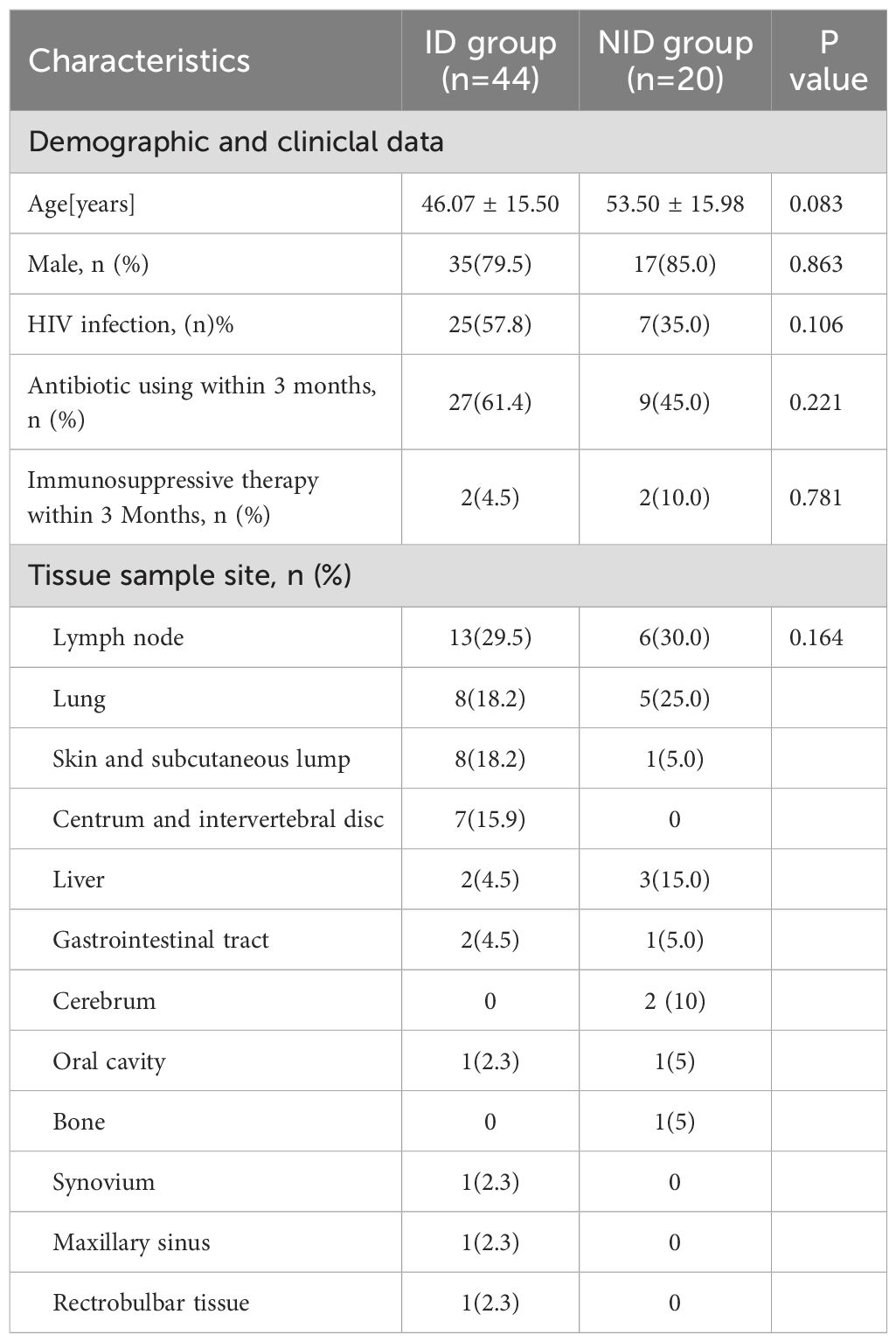

Among 70 patients with suspected infectious diseases, 6 patients were finally excluded for undefined diagnosis. Total 44 cases were diagnosed with infectious diseases (ID), and 20 cases were diagnosed with no-infectious diseases (NID) were enrolled in the study. Among the enrolled patients, 32(50.0%)were HIV positive, and 25(57.8%) were HIV negative. There was no significant difference between ID group and NID group in age, HIV status, sex, antibiotic using within 3 months, immunosuppressive therapy within 3 months, tissue type. The most of tissue samples were obtained from lymph nodes, followed by lung, skin and subcutaneous lump (Table 1).

Pathogens spectrum among ID group

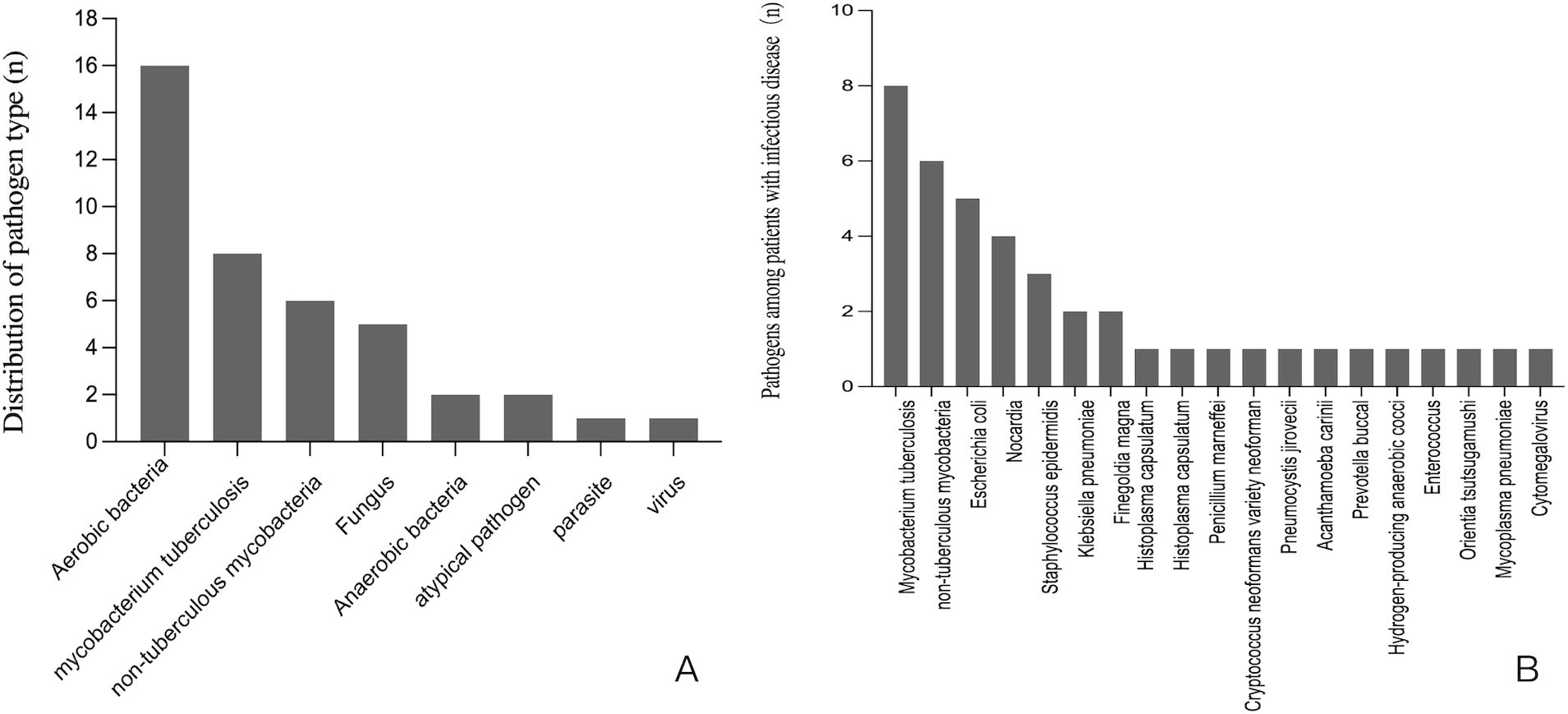

Among 44 patients ultimately diagnosed with infectious diseases through tissue-based mNGS and/or CMTs, 72.7% were HIV-positive. The distribution of pathogen type was shown in Figure 1A. Aerobic bacteria (n=16) was the most frequently detected, followed MTB (n=8), NTM (n=6), fungus (n=5), anaerobic bacteria (n=2), atypical pathogen (n=2), parasite (n=1) and virus (n=1). As shown in Figure 1B, for pathogens spectrum of 44 patients with infection, MTB (n=8) was the most common detected pathogen, followed by NTM (n=6), Escherichia coli (n=5), Nocardia (n=4), Staphylococcus epidermidis (n=3), Klebsiella pneumoniae (n=2) and Finegoldia magna(n=2).

Figure 1. (A) The distribution of pathogen type among patients with infectious disease. (B) The pathogens spectrum among 44 patients with infectious disease.

In ID group, there were 40 cases (90.9%) diagnosed with monomicrobial infection and 4 cases (9.1%, all are HIV positive) diagnosed with polymicrobial infection (≥2 non-HIV pathogens). Among 40 patients with monomicrobial infection, 12 cases (30.0%) were detected via CMTs, while 28 cases (70.0%) were detected by mNGS. Among 4 polymicrobial infections, 1 case (25.5%) were detected via CMTs, while 4 cases (100.0%) were detected by mNGS. For monomicrobial infection, the detection rate of mNGS was higher than that of CMTs (p <0.001).

Consistency between mNGS and CMTs in ID group

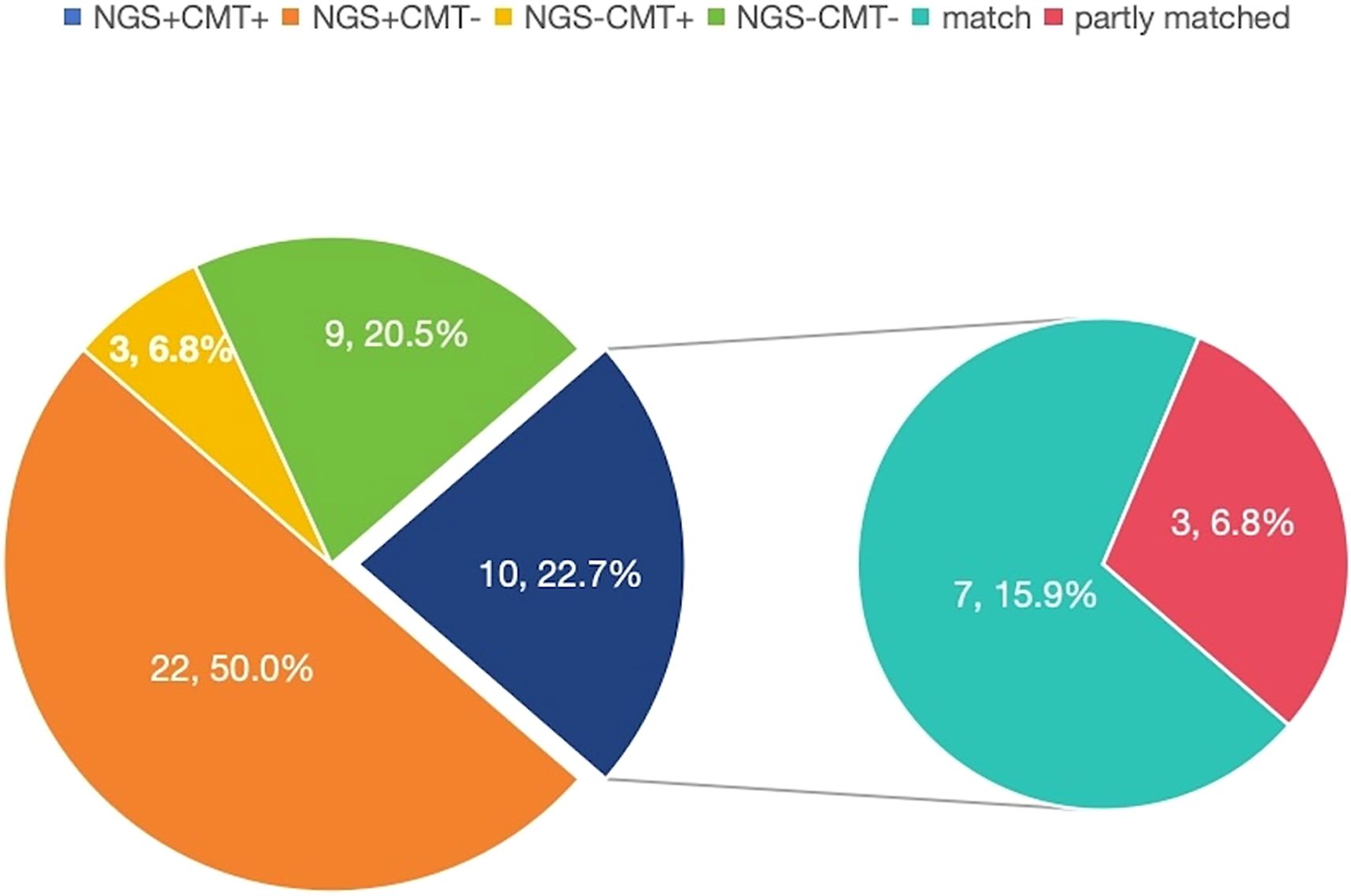

In ID group, both positive mNGS and CMTs were observed in 10 (22.7%) patients, and both negative mNGS and CMTs were observed in 9 (20.5%) patients. Sole positive mNGS and sole positive CMTs were observed in 22 (50.0%) and 3 (6.8%) patients, respectively. For double-positive samples, the 2 results were completely matched in 7 cases (Figure 2).

Comparison of diagnostic performance between mNGS and CMTs

The diagnostic accuracy was further compared between mNGS and CMTs for tissue. The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) of tissue mNGS were 72.7% (95%CI 56.9%-84.5%), 85.0% (95%CI 61.1%-96.0%), 91.4% (95%CI 75.8%-97.8%) and 58.6% (95%CI 39.1%-75.9%), respectively. The sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV of tissue CMTs were 29.5% (95%CI 17.2%-45.4%), 95.0% (95%CI 73.0%-99.7%), 92.9% (CI 64.3%-99.6%), 38% (CI 25.5%-52.8%), respectively. Compared with CMTs, the sensitivity of mNGS was significantly higher (p<0.001), but the specificity between the two methods had no significant difference (p=0.625). When combined with tissue mNGS and CMTs, the sensitivity was raised to 75.6%(p=0.250), the specificity was decreased to 78.9% (p=1.000) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Positive rate comparison and concordance analysis between metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) and conventional microbiological tests (CMTs) for infectious disease (ID) group and noninfectious disease (NID) group. There were statistical differences between mNGS and CMTs of ID group (P < 0.01), but no differences in NID group (P > 0.05). The number of positive samples (y-axis) for pairwise mNGS and CMTs testing is plotted against the ID and NID groups (x-axis). **P<0.01, ns P>0.05.

Correlative factors for detection of mNGS

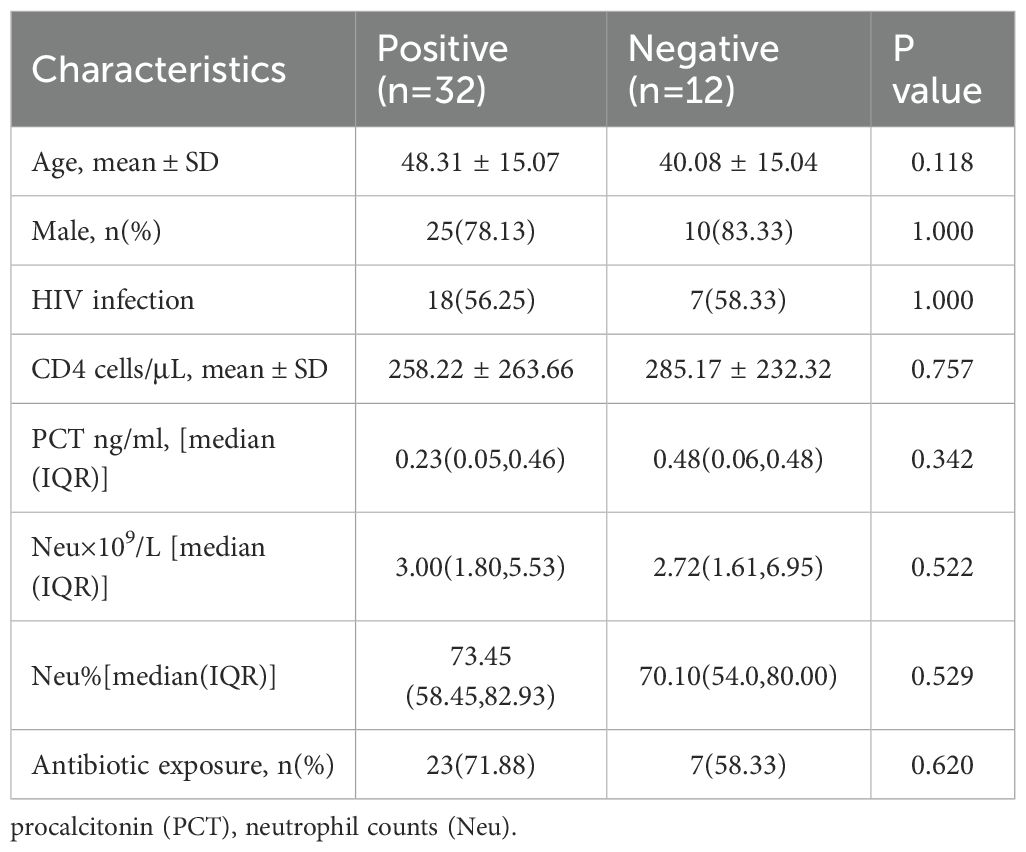

The correlative factors including demographic characteristics, inflammatory and immune function indicators, and antibiotic exposure are analyzed. The results showed (Table 2) that there were no statistically differences in the average age, gender, HIV infection status, CD4+ lymphocyte count (CD4 count), PCT level, absolute neutrophil count, percentage of neutrophil and antibiotic exposure between positive and negative groups by mNGS (P > 0.05).

Discussion

CMTs with low positive rate are still the routine examination methods for the diagnosis of infectious diseases. Despite the high sensitivity of mNGS in the liquid samples, the diagnostic value of mNGS for tissue in infection disease was rarely reported. Our study supplemented the associated data, demonstrating that tissue mNGS could be a useful tool for identifying the pathogens due to its higher sensitivity, more robust and broader pathogen spectrum than CMTs, which might be conductive for prompt diagnosis and early treatment in infectious disease. However, tissue CMTs should also be performed since the low consistency between mNGS and CMTs.

To date, few studies have confirmed the sensitivity and specificity of tissue mNGS. Our study found that mNGS of tissue had significantly higher sensitivity by comparison with CMTs of tissue (72.7% vs. 29.5%, p<0.001), and the comparison of specificity was 85.0% vs. 95.0% (p=0.625). Studies demonstrated that mNGS exhibits significantly enhanced diagnostic sensitivity compared to CMTs when analyzing tissue and other samples for infectious pathogens (Wang et al., 2020; Duan et al., 2021; Hao et al., 2023; Qin et al., 2024; Yang et al., 2024). In addition, our results revealed no statistically significant difference in specificity between tissue mNGS and CMTs for the diagnosis of infectious diseases. Similar to our findings, studies showed that the specificity of mNGS and CMTs in tissue and other samples was not statistically different (p>0.05) (Chen et al., 2023; Pang et al., 2023; Lv et al., 2024). One study conducted a comprehensive systematic literature review and meta-analysis of mNGS outcomes in patients with unexplained fever, the results for mNGS and CMTs revealed a pooled sensitivity of 0.91 and 0.34, with a pooled specificity of 0.64 and 0.90, respectively (Marra et al., 2024). The above results indicate that mNGS demonstrates significantly enhanced diagnostic sensitivity relative to CMTs while maintaining equivalent specificity, positioning it as a valuable diagnostic modality for detecting tissue-based infections in clinical practice. Due to the limitation of sample size, we did not analyze the sensitivity and specificity of mNGS in different tissue samples, which is worth further exploration.

The culture of tissue was an important means of obtaining a clear etiological diagnosis. However, its positive rate is often influenced by factors such as bacterial load and cultivation techniques (Miao et al., 2018). A research exploring the diagnostic value of mNGS in infectious diseases, explored the correlation between the status of immune function in patients and the positive results of pathogen examination. Similar with our results, they found that no statistical significance was observed in the neutrophil count, the CD4 count and PCT level between mNGS-positive and mNGS-negative patients (Duan et al., 2021). A study found that the use of antibiotics will reduce the positive rate of mNGS, but its positive duration is significantly longer than that of conventional blood culture (Xu et al., 2025). However, in our study, the positive rate of mNGS for tissue sample was not decreased by the use of antibiotics, which also indicates the robustness of mNGS technology in the diagnosis of infectious diseases, although it was not statistically significant. The lack of significant differences in age, gender, HIV infection, PCT levels, neutrophil counts, and antibiotic exposure between the two groups suggests that these factors may not be strong predictors of mNGS positivity in this cohort and mNGS is robust in the diagnosis of pathogen infection.

Our study suggested that mNGS and CMTs of tissue had a low consistency (43.2%) in detecting pathogens in tissue sample, and the double positive rate of these two methods was just 22.70%, only 15.9% patients detected the same pathogens exactly. Consistent with our data, studies showed that the double positive rate of mNGS and traditional culture in identifying pathogens of different clinical samples in 109 patients with different infectious diseases was 19.27% (Duan et al., 2021). Another study showed that the double positive rate of mNGS and traditional diagnostic methods in identifying pathogens of different clinical samples in 372 patients with different infectious diseases was 24.2%, but the double positive rate of diverse tissue mNGS hasn’t been studied (Wang et al., 2022). In addition to its high specificity and the low consistency between the two methods—which make CMTs indispensable—other unique advantages over mNGS cost-effectiveness, accessibility, and resistance profiling. The affordability and accessibility of CMTs make it as the preferred choice in clinic. CMTs also could provide the results of phenotypic antibiotic susceptibility. All these reasons demonstrated that tissue mNGS couldn’t replace tissue CMTs in patients with suspected infectious disease completely, and both the two methods should be performed in order to better identify the pathogens.

Study showed that bronchoalveolar lavage fluid mNGS was superior to CMTs in diagnosing monomicrobial infections (92% vs. 52%, p=0.000) and polymicrobial infections (66% vs. 14%, p=0.000) (Deng et al., 2022). Our study observed that the detection rate of mNGS (70.0%) was higher than that of CMTs (30.0%) in monomicrobial infection(p<0.01), and the detection rate of mNGS (100.0%) was higher than that of CMTs (25.5%) in polymicrobial infection, although the difference was not statistically significant. The marked disparity in detection rates likely reflects methodological advantages of mNGS, with the lack of significance potentially attributable to the limited sample size in this subgroup analysis. In our study, all patients with polymicrobial infection were HIV positive. It is well known that immunodeficient patients (HIV-Infected individuals, patients taking immunosuppressive agents, etc) are more susceptible to opportunistic infections and co-infection with multiple pathogens, therefore, tissue mNGS plays an crucial role in more comprehensive and sensitive pathogen detection for immunodeficient patients.

Our study revealed that aerobic bacteria, MTB, NTM, and fungi constituted the predominant pathogens identified. This microbial profile may be associated with two notable characteristics of our cases: a substantial proportion of HIV-positive patients (56.8%) and frequent lymph node biopsy specimens (29.5%). MTB was the most common pathogen identified by tissue mNGS, followed by NTM. Study showed people living with HIV are more likely to develop active tuberculosis than those without HIV (Adhikari et al., 2022). The clinical significance of MTB and NTM detection warrants particular emphasis. As increasingly recognized opportunistic pathogens (Cowman et al., 2019), NTM can manifest through diverse clinical presentations including pulmonary infections, pediatric cervical lymphadenitis, post-vaccination soft tissue infections, and disseminated disease in immunocompromised hosts (Daley et al., 2020; Ricotta et al., 2021). These varied manifestations underscore the critical importance of early pathogen identification and prompt therapeutic intervention. Our findings align with growing evidence highlighting the diagnostic advantages of mNGS, particularly for detecting fastidious organisms like MTB and NTM that present challenges for conventional culture-based methods. The mNGS’s capacity to overcome traditional diagnostic limitations suggests its potential value in managing complex infections, especially in immunocompromised populations.

The relative small sample size was the primary limitation of our study. Although many results demonstrated certain trends, they did not reach statistical significance. And due to the limited sample size, subgroup analyses by HIV status, tissue type or antibiotic exposure were not statistically viable, which may limit the generalizability of our findings. Therefore, future studies with expanded cohorts should validate these relationships.

Conclusions

In summary, mNGS demonstrates superior sensitivity, more robust results and a broader pathogen detection spectrum compared to CMTs in tissue samples, particularly for fastidious organisms, as well as polymicrobial infections. mNGS should be used in combination with CMTs to optimizes diagnostic yield.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University (2024310K). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and institutional requirements. The manuscript presents research on animals that do not require ethical approval for their study.

Author contributions

YL: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YT: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Project administration, Writing – original draft. FX: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Resources, Writing – review & editing. SW: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Software, Writing – review & editing. SZ: Investigation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. QC: Investigation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. JL: Investigation, Software, Writing – review & editing. SS: Project administration, Resources, Writing – review & editing. QD: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. WG: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. KL: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by Medical Science and Technology Innovation Platform Support Project of Zhongnan Hospital, Wuhan University, grant number PTXM2020008, the Science and Technology Innovation Cultivation Fund of Zhongnan Hospital, Wuhan University, grant number cxpy2017043, Non-profit Central Research Institute Fund of Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, grant number 2020-PT320-004.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adhikari, N., Bhattarai, R. B., Basnet, R., Joshi, L. R., Tinkari, B. S., Thapa, A., et al. (2022). Prevalence and associated risk factors for tuberculosis among people living with HIV in Nepal. PloS One 17, e0262720. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0262720

Chen, H., Tang, M., Yao, L., Zhang, D., Zhang, Y., Zhao, Y., et al. (2023). Early application of metagenomics next-generation sequencing may significantly reduce unnecessary consumption of antibiotics in patients with fever of unknown origin. BMC Infect. Dis. 23, 478. doi: 10.1186/s12879-023-08417-3

Chen, Q., Chen, Z., Tan, Y., Wu, S., Zou, S., Liu, J., et al. (2024). Blood microbiota in HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected patients with suspected sepsis detected by metagenomic next-generation sequencing. BMC Infect. Dis. 24, 1210. doi: 10.1186/s12879-024-10009-8

Cowman, S., van Ingen, J., Griffith, D. E., and Loebinger, M. R. (2019). Non-tuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease. Eur. Respir. J. 54,1900250. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00250-2019

Daley, C. L., Iaccarino, J. M., Lange, C., Cambau, E., Wallace, R. J., Jr., Andrejak, C., et al. (2020). Treatment of nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease: an official ATS/ERS/ESCMID/IDSA clinical practice guideline. Eur. Respir. J. 56. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00535-2020

Deng, W., Xu, H., Wu, Y., and Li, J. (2022). Diagnostic value of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid metagenomic next-generation sequencing in pediatric pneumonia. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 12, 950531. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2022.950531

Dong, G., Hao, Z., Zhang, C., and Deng, A. (2024). Unveiling challenging corneal infections: a comprehensive etiological diagnosis through metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) of corneal tissue samples. Int. Ophthalmol. 44, 246. doi: 10.1007/s10792-024-03201-x

Duan, H., Li, X., Mei, A., Li, P., Liu, Y., Li, X., et al. (2021). The diagnostic value of metagenomic next rectanglegeneration sequencing in infectious diseases. BMC Infect. Dis. 21, 62. doi: 10.1186/s12879-020-05746-5

Hao, J., Li, W., Wang, Y., Zhao, J., and Chen, Y. (2023). Clinical utility of metagenomic next-generation sequencing in pathogen detection for lower respiratory tract infections and impact on clinical outcomes in southernmost China. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 13, 1271952. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2023.1271952

Jin, X., Li, J., Shao, M., Lv, X., Ji, N., Zhu, Y., et al. (2022). Improving suspected pulmonary infection diagnosis by bronchoalveolar lavage fluid metagenomic next-generation sequencing: a multicenter retrospective study. Microbiol. Spectr. 10, e0247321. doi: 10.1128/spectrum.02473-21

Lv, H., Liao, S., Shi, Z., Guo, Y., Zhou, J., Chen, H., et al. (2024). Application of metagenomic next-generation sequencing for rapid molecular identification in spinal infection diagnosis. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 14, 1382635. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2024.1382635

Marra, A. R., Lopes, G. O. V., Pardo, I., Hsieh, M. K., Kobayashi, T., Marra, P. S., et al. (2024). Metagenomic next-generation sequencing in patients with fever of unknown origin: A comprehensive systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 110, 116465. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2024.116465

Miao, Q., Ma, Y., Wang, Q., Pan, J., Zhang, Y., Jin, W., et al. (2018). Microbiological diagnostic performance of metagenomic next-generation sequencing when applied to clinical practice. Clin. Infect. Dis. 67, S231–SS40. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy693

Miller, S., Naccache, S. N., Samayoa, E., Messacar, K., Arevalo, S., Federman, S., et al. (2019). Laboratory validation of a clinical metagenomic sequencing assay for pathogen detection in cerebrospinal fluid. Genome Res. 29, 831–842. doi: 10.1101/gr.238170.118

Pang, F., Xu, W., Zhao, H., Chen, S., Tian, Y., Fu, J., et al. (2023). Comprehensive evaluation of plasma microbial cell-free DNA sequencing for predicting bloodstream and local infections in clinical practice: a multicenter retrospective study. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 13, 1256099. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2023.1256099

Qian, Y. Y., Wang, H. Y., Zhou, Y., Zhang, H. C., Zhu, Y. M., Zhou, X., et al. (2020). Improving pulmonary infection diagnosis with metagenomic next generation sequencing. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 10, 567615. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2020.567615

Qin, W., Guo, T., You, T., Tian, R., Cui, X., and Wang, P. (2024). Metagenomic next generation sequencing of bronchoalveolar lavage fluids for the identification of pathogens in patients with pulmonary infection: A retrospective study. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 110, 116402. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2024.116402

Ricotta, E. E., Adjemian, J., Blakney, R. A., Lai, Y. L., Kadri, S. S., and Prevots, D. R. (2021). Extrapulmonary nontuberculous mycobacteria infections in hospitalized patients, United States, 2009-2014. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 27, 845–852. doi: 10.3201/eid2703.201087

Schlaberg, R., Chiu, C. Y., Miller, S., Procop, G. W., Weinstock, G., Professional Practice, C., et al. (2017). Validation of metagenomic next-generation sequencing tests for universal pathogen detection. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 141, 776–786. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2016-0539-RA

Sun, L., Zhang, S., Yang, Z., Yang, F., Wang, Z., Li, H., et al. (2022). Clinical application and influencing factor analysis of metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) in ICU patients with sepsis. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 12, 905132. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2022.905132

Tan, Y., Chen, Z., Zeng, Z., Wu, S., Liu, J., Zou, S., et al. (2023). Microbiomes detected by bronchoalveolar lavage fluid metagenomic next-generation sequencing among HIV-infected and uninfected patients with pulmonary infection. Microbiol. Spectr. 11, e0000523. doi: 10.1128/spectrum.00005-23

Wang, Q., Miao, Q., Pan, J., Jin, W., Ma, Y., Zhang, Y., et al. (2020). The clinical value of metagenomic next-generation sequencing in the microbiological diagnosis of skin and soft tissue infections. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 100, 414–420. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.09.007

Wang, C., Yan, D., Huang, J., Yang, N., Shi, J., Pan, S., et al. (2022). The clinical application of metagenomic next-generation sequencing in infectious diseases at a tertiary hospital in China. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 12, 957073. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2022.957073

Xu, Y., Peng, M., Zhou, T., Yang, Y., Xu, P., Xie, T., et al. (2025). Diagnostic performance of metagenomic next-generation sequencing among hematological Malignancy patients with bloodstream infections after antimicrobial therapy. J. Infect. 90, 106395. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2024.106395

Yang, H., Xu, N., Yan, M., Yang, L., Wen, S., Wang, S., et al. (2024). Comparison of metagenomic next-generation sequencing and conventional culture for the diagnostic performance in febrile patients with suspected infections. BMC Infect. Dis. 24, 350. doi: 10.1186/s12879-024-09236-w

Keywords: metagenomic, next-generation, sequencing, tissue, conventional, microbiological tests, consistency, sensitivity

Citation: Liu Y, Tan Y, Xia F, Wu S, Zou S, Chen Q, Liu J, Song S, Du Q, Guo W and Liang K (2025) Diagnostic utility of metagenomic next-generation sequencing for tissue in patients with suspected infectious diseases. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 15:1634406. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2025.1634406

Received: 24 May 2025; Accepted: 06 November 2025; Revised: 01 November 2025;

Published: 25 November 2025.

Edited by:

Li Ang, First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University, ChinaCopyright © 2025 Liu, Tan, Xia, Wu, Zou, Chen, Liu, Song, Du, Guo and Liang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ke Liang, a2VsaWFuZ0B3aHUuZWR1LmNu; Wei Guo, Z3Vvd2VpQHdodS5lZHUuY24=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Yaqing Liu1,2†

Yaqing Liu1,2† Yuting Tan

Yuting Tan Songjie Wu

Songjie Wu Qianhui Chen

Qianhui Chen Wei Guo

Wei Guo Ke Liang

Ke Liang