- 1Department of Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine, School of Public Health and Preventive Medicine, Monash University, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

- 2Prothikrit Institute of Health Studies (PIHS), Dhaka, Bangladesh

- 3Diabetes and Population Health, School of Public Health and Preventive Medicine, Monash University, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

- 4Baker Heart and Diabetes Institute, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

- 5Centre for Injury Prevention and Research, Bangladesh (CIPRB), Dhaka, Bangladesh

- 6Department of Population Science, Jatiya Kabi Kazi Nazrul Islam University, Department of Public Health, First Capital University of Bangladesh, Chuadanga, Bangladesh

- 7Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Faculty of Medicine, Dentistry and Health Sciences, The University of, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

- 8Department of Molecular and Translational Science, Monash University, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

Objective: To estimate the prevalence of inadequate glycaemic control and identify factors associated with it among people with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) living in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).

Methods: A systematic literature search was conducted in the Medline, Embase, CINAHL, PsychINFO, and Global Health databases for articles published between 1 January 2001 and 15 April 2025. Information was descriptively summarised following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses guidelines. The quality of the articles was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale. Random effects model was used to obtain the pooled proportion of inadequate glycaemic control. Heterogeneity (I2) was tested, sensitivity analyses were performed, and publication bias was examined using Egger’s regression test.

Results: Among 12,985 records, 62 studies from 28 countries involving 176,349 participants were reviewed. The estimated pooled proportion of inadequate glycaemic control (glycosylated haemoglobin [HbA1c] ≥7%) was 69% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 66%–72%, p <0.001, I2 = 99.10%), with no publication bias (Egger’s test, p = 0.489). A number of factors were associated with inadequate glycaemic control (overall p < 0.001), including education below secondary level (OR: 1.47, 95% CI: 0.98–1.97), rural residence (OR: 1.80, 95% CI: 1.33–2.28), obesity (OR: 1.17, 95% CI: 1.11–1.22), use of oral glucose-lowering drugs and/or insulin (OR: 4.06, 95% CI: 2.58–5.54 and OR: 2.44, 95% CI: 1.70–3.19, respectively), non-adherence to diet (OR: 2.13, 95% CI: 1.33–2.93) and treatment (OR: 2.08, 95% CI: 1.61–2.54), and physical inactivity (OR: 2.15, 95% CI: 1.35–2.95).

Conclusion: More than two-thirds of people with T2DM in LMICs have inadequate glycaemic control. Urgent interventions are needed, focusing on sociodemographic, lifestyle, and treatment-related factors.

Systematic Review Registration: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO, identifier CRD: 42023390577.

1 Introduction

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is a major global public health challenge with an increasing burden, particularly in resource-limited settings. In 2024, an estimated 589 million adults were living with diabetes worldwide, with approximately 80% residing in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) (1–3). The number of people living with diabetes is projected to reach 853 million by 2050, with LMICs accounting for 95% of this increase, reflecting a growing disparity in disease burden (1–3). According to the World Bank classification (2024), low income countries have a gross national income (GNI) per capita of USD 1,145 or less, lower-middle-income countries range between USD 1,146 and 4,515, and upper-middle-income countries range between USD 4,516 and 14,005 (4). These countries face significant challenges in diabetes prevention and management, including limited healthcare infrastructure, restricted access to diagnostic testing such as glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c), and inconsistent long-term follow-up care.

T2DM substantially increases the risk of major macrovascular (heart disease, stroke, lower-limb amputation) and microvascular (retinopathy, nephropathy, neuropathy) complications, which contribute to disability and premature mortality (5). Maintaining adequate glycaemic control, most commonly assessed by HbA1c, is a cornerstone of diabetes management and is strongly linked to a reduced risk of complications and improved quality of life. The American Diabetes Association recommends an HbA1c target of <7% (6), yet globally only 50% of people with diabetes achieve this target. Control rates are markedly lower in LMICs (37%) compared with high-income countries (52.2–53.6%) (7–9).

Multiple interrelated factors influence glycaemic control. Individual-level determinants include obesity, physical inactivity, unhealthy dietary patterns, and medication non-adherence (10–12), while sociodemographic factors such as lower educational attainment and rural residence, and low socioeconomic status are associated with suboptimal control (12). Health system barriers including limited access to healthcare, fragmented care continuity, and medication shortages further exacerbate poor outcomes (12). Moreover, cultural and lifestyle factors, such as dietary patterns and healthcare-seeking behaviours, differ significantly from those in high-income countries, influencing diabetes outcomes in unique ways (13).

Although several reviews have examined glycaemic control, most have included both type 1 and type 2 diabetes or focused on specific regions such as sub-Saharan Africa or the Gulf countries (10, 12–14). Consequently, available evidence remains fragmented and highly context-specific, limiting the generalisability of findings across LMICs. Understanding the magnitude and determinants of inadequate glycaemic control in these settings is crucial for developing targeted, context-appropriate interventions and informing national and global policy to improve diabetes outcomes in resource-limited environments.

The rationale for this systematic review and meta-analysis is therefore stems from the global rise in T2DM, its disproportionate impact on LMICs, and the lack of comprehensive synthesis of existing evidence. Hence, this review aims to estimate the prevalence of inadequate glycaemic control (HbA1c ≥7%) and identify its associated factors among adults with T2DM in LMICs. By integrating data from diverse settings, this study seeks to provide a more complete understanding of the determinants of inadequate glycaemic control and to highlight priority areas for targeted intervention.

2 Methods

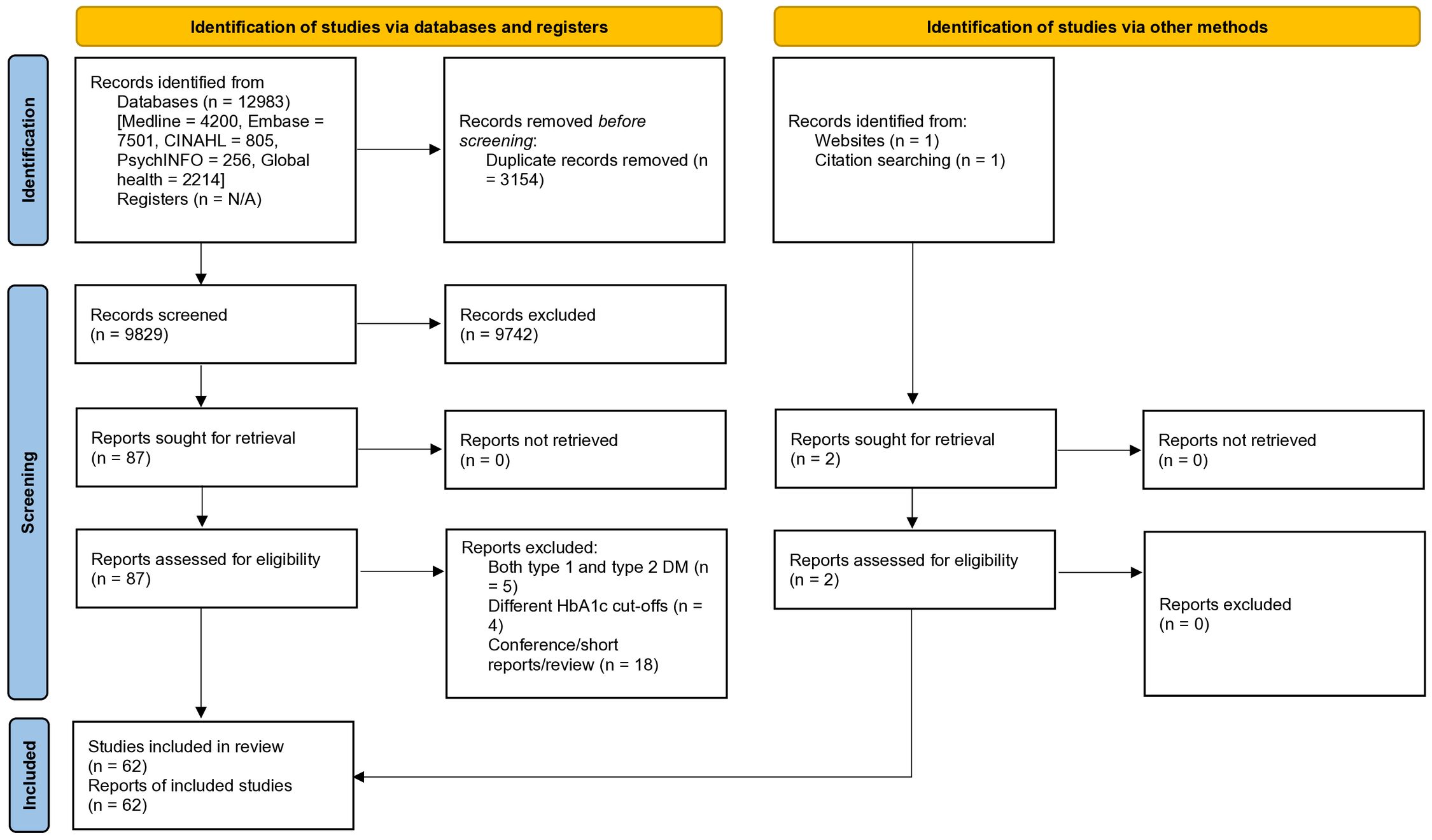

This systematic review and meta-analysis was registered with PROSPERO (CRD: 42023390577) and conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Appendix 1) (15). The review process is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) 2020 flow diagram.

2.1 Selection criteria

This review followed the PECO framework: P (population), E (Exposure), C (comparison), O (outcome). Population – adults (≥18 years) with type 2 diabetes mellitus living in low- and middle-income countries; Exposure – sociodemographic, lifestyle, and clinical factors potentially associated with glycaemic control; and Outcome – inadequate glycaemic control, defined as HbA1c ≥7%.

All published observational studies (cross-sectional, case–control, and retrospective or prospective cohort designs) reporting the prevalence of inadequate glycaemic control, assessed by HbA1c testing, among adults with T2DM in LMICs were eligible for inclusion. There were no restrictions on language or publication year.

Studies were excluded if they:

1. Focused exclusively on individuals with type 1 diabetes, both type 1 and type 2 diabetes, gestational diabetes, or diabetes-related complications;

2. Did not define or report glycaemic control, or used non-standard HbA1c thresholds or mean HbA1c values instead of categorical definitions;

3. Were qualitative studies, randomised controlled trials, or were not primary research (e.g., editorials, commentaries, abstracts, dissertations, reviews, or case reports).

2.2 Search strategy

A systematic literature search strategy was developed in consultation with a librarian from Monash University. The search focused on a range of keywords relating to glycaemic control, T2DM and a list of LMICs based on the current World Bank Database (4). Five databases (Medline, Embase, CINAHL, PsychINFO and Global Health) were searched between 1 January 2001 and 15 April 2025 by two authors (BNS and HAC) independently, following the developed search strategy. The detailed search strategy is provided in Appendix 2. Additionally, reference lists of the included studies and websites (e.g., Google Scholar) were manually searched to identify potential articles.

2.3 Study selection process

Searched articles were stored and managed using the citation software EndNote X20. After the searches, BNS and HAC independently removed the duplicates. Furthermore, titles and abstracts were screened independently for inclusion in the review. The authors also independently reviewed the full text of the remaining articles. Any discrepancies between reviewers were addressed by consultation with the senior author (BB). Finally, 62 articles were included in this review.

2.4 Study outcome and exposures

The outcome of this review was the prevalence of people with T2DM who had inadequate glycaemic control (expressed as a percentage), defined as an HbA1c level of ≥7% (6). The exposures included any factors associated with inadequate glycaemic control (e.g., socio-demographic, clinical, anthropometric, behavioural, and psychological), reported as odds ratios.

2.5 Data extraction

Two authors (BNS and MRKC) independently extracted data from the included articles using Microsoft Excel. Another author (HAC) then cross-checked the extracted data. Any discrepancies were discussed and resolved between the authors, and the senior author BB made the final recommendation where necessary. The following information was extracted: publication details (authors, year of publication, journal), study characteristics (country where the study was conducted, study design, study setting, study population, sample size), participants’ demographics (gender, age, education, occupation) and the prevalence of poor/inadequate or good/adequate glycaemic control and factors associated with it. Missing data were sought from the authors of the studies, where required.

2.6 Quality assessment

The quality of all included studies was independently assessed by two authors (BNS and HAC) using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for observational studies (cross-sectional, case-control and cohort studies) (16). The tool utilises a ‘star system’ to evaluate studies from three primary perspectives: the selection of study groups, the comparability of those groups, and the identification of the exposure of interest (outcome) for cross-sectional and cohort studies. Cut-off values of 0-4, 5–6 and ≥7 were used to classify the studies as poor, fair and good quality, respectively. Discrepancies were resolved by the senior author BB. A detailed description of the quality assessment tool is provided as supporting information (Appendix 3).

2.7 Data analysis

Extracted data were analysed (BNS) and cross-checked by another author (AA). A random-effects model was used to estimate the pooled prevalence of inadequate glycaemic control and other relevant quantitative data with a 95% confidence interval (CI). Heterogeneity among studies was tested using the χ2 test on Cochran’s Q statistic, which was calculated using H and I2 indices. Along with a non-significant result (p-value >0.05), an I² value >50% was considered to indicate substantial heterogeneity, while a value >75% was considered considerable heterogeneity (17). An individual study contribution to overall heterogeneity was assessed by excluding each study and recording the change in overall heterogeneity (18). Subgroup/sensitivity analyses were also performed with the covariates such as participants’ sociodemographic, clinical, and behavioural characteristics, as well as study quality, geographic region, and the income level of the country, to identify possible substantial/considerable heterogeneity. The income level of each country was classified as low-income, lower-middle-income and upper-middle-income according to the World Bank (4). Publication bias was examined by generating funnel plots and quantitatively by Egger’s regression test (19). All the statistical analyses were conducted using Stata V.16 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA).

3 Results

A total of 12,985 articles, published between 1 January 2001 and 15 April 2025, were retrieved. These articles were sourced from five databases and supplemented with manual searches. After the removal of duplicate records and screening based on titles and abstracts, a refined selection of 89 articles was deemed suitable for full-text review. From this refined pool, 27 articles were excluded due to non-compliance with the inclusion criteria. Eventually, a dataset of 62 studies, spanning 28 different countries, was identified (Figure 1) (20–81). These studies collectively represented a participant pool of 176,349 individuals (the study’s sample size ranged from 92 to 55,639).

3.1 Characteristics of the study participants

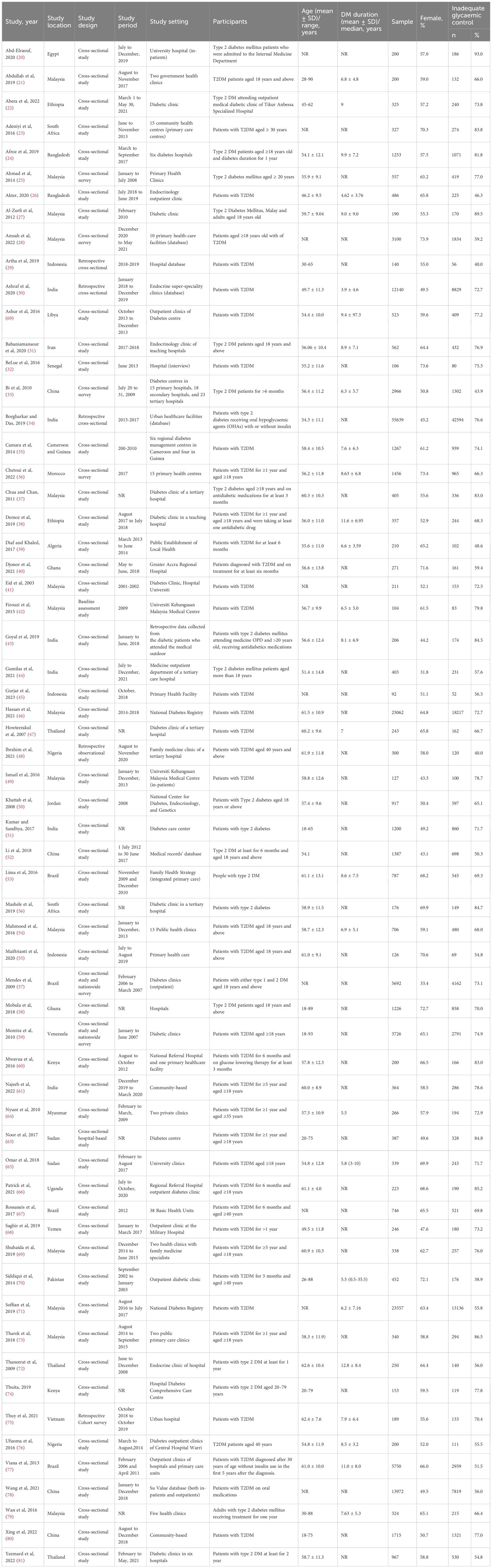

All included studies were cross-sectional, except for one retrospective cohort survey. Approximately half were conducted in hospitals (diabetes clinics/centres) (n = 33; 53%), followed by primary care centres (n = 23; 38%) and hospital in-patient settings (n = 2; 3%). Only four were community-based studies (6%). All of the studies included people with T2DM except one which included people with type 1 and those with T2DM but reported results separately. In this review, only data on T2DM were included in the analysis. Most of the studies (57 out 62) were published in the year 2010 or later. Of the included studies, 31 (50%) were conducted in upper-middle- income countries, 26 (42%) in lower-middle-income countries and only five (8%) in low-income countries. By geographic region, 38 (61%) studies were from Asia, 19 (31%) studies were from Africa and the remaining five (8%) were from South America. Gender was reported in the majority of the studies with 54.3% of participants across the combined sample being female. The age of the study participants ranged from 18 to 93 years. Out of 62 studies, 44 studies reported participants’ educational attainment; only 21.7% of participants had continued beyond secondary school. Employment status was reported in 32 studies and 34.7% of participants were employed. Table 1 shows the detailed characteristics of the included studies. No studies addressed the handling of missing information. Multiple logistic regression was used to identify factors related to glycaemic control. Although machine learning algorithms are emerging as an efficient method for determining factors related to health outcomes, none of the studies included in this review utilised them.

3.2 Quality of included studies

The quality of the included studies was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for cross-sectional and cohort studies, with ratings ranging from poor to good. Most studies scored well in the selection domain, particularly in terms of the representativeness of the study population, although limitations were noted in the ascertainment of exposure (19 studies). The comparability domain revealed shortcomings, as 10 studies did not adjust for key confounders such as age and sex. Additionally, 10 studies had issues in the outcome domain, particularly related to statistical analysis. Overall, 19 studies were rated as poor quality, 26 as fair, and 17 as good. These quality categories were considered in the sensitivity analysis (Appendix 4 and 5).

3.3 Glycaemic control (assessment and prevalence)

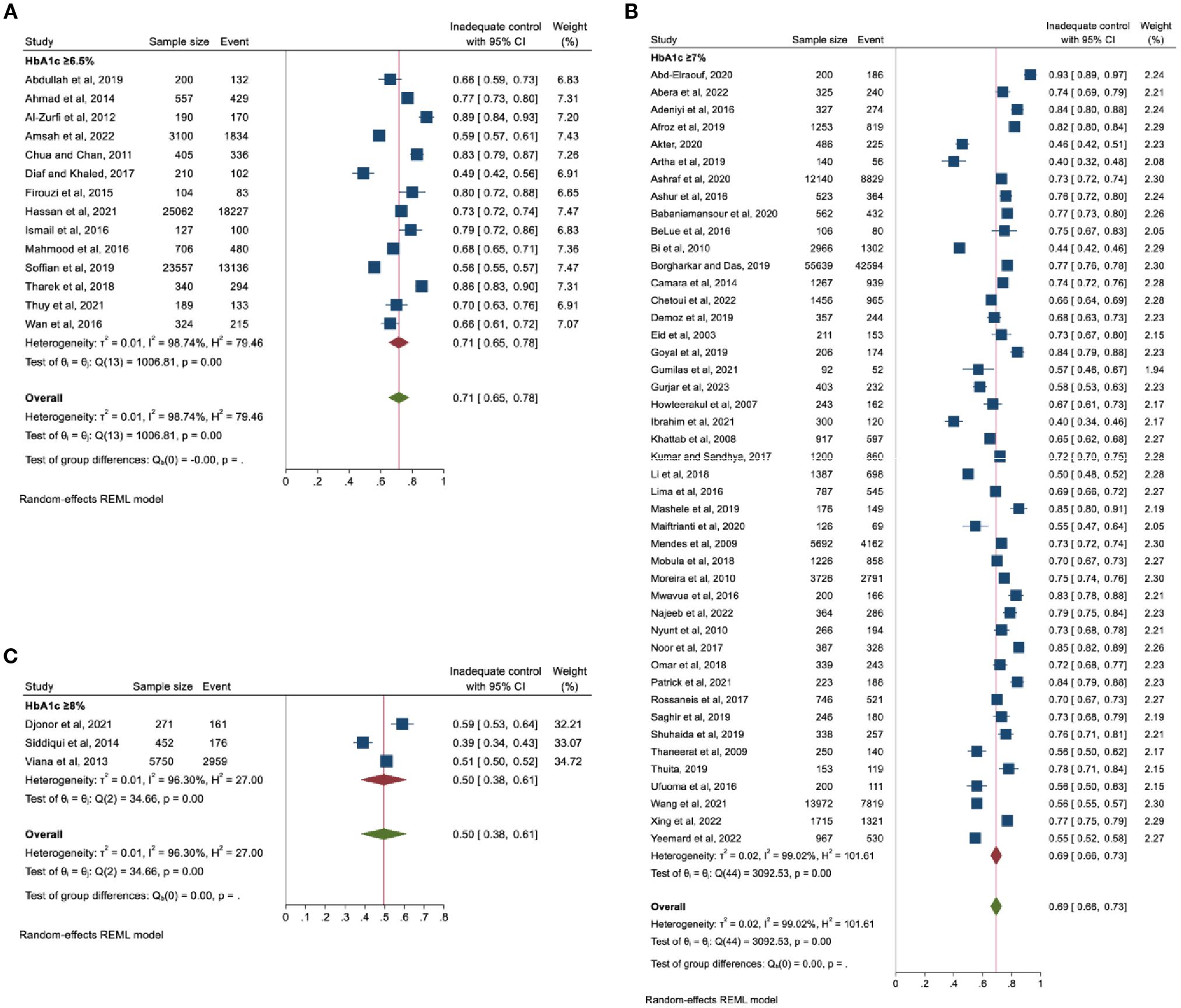

All the included studies assessed glycaemic control by HbA1c (%), but the cut-offs for inadequate glycaemic control varied: 14 studies used HbA1c ≥6.5%, 45 used HbA1c ≥7% and the remaining three used HbA1c ≥8% (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Pooled prevalence of inadequate glycaemic control based on HbA1c thresholds (A) ≥6.5%, (B) ≥7%, and (C) ≥8%.

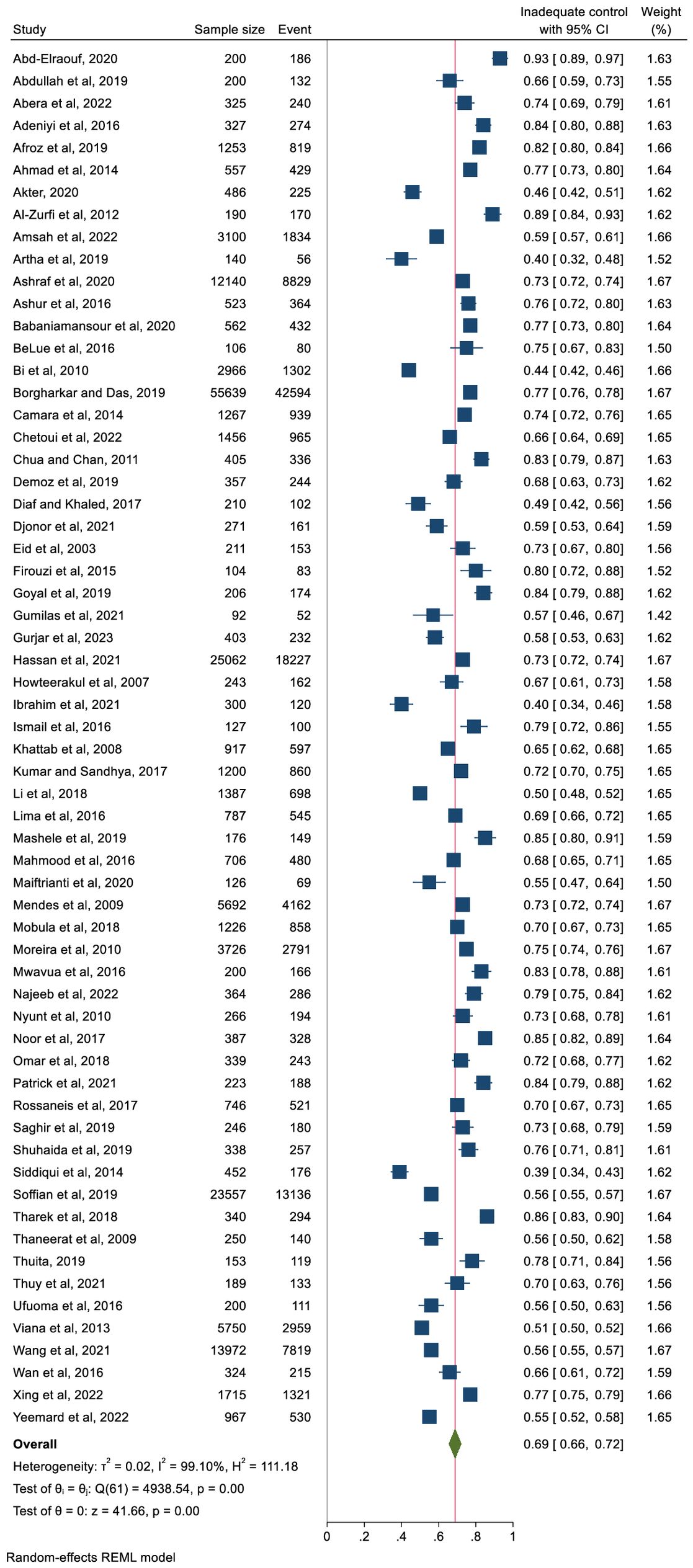

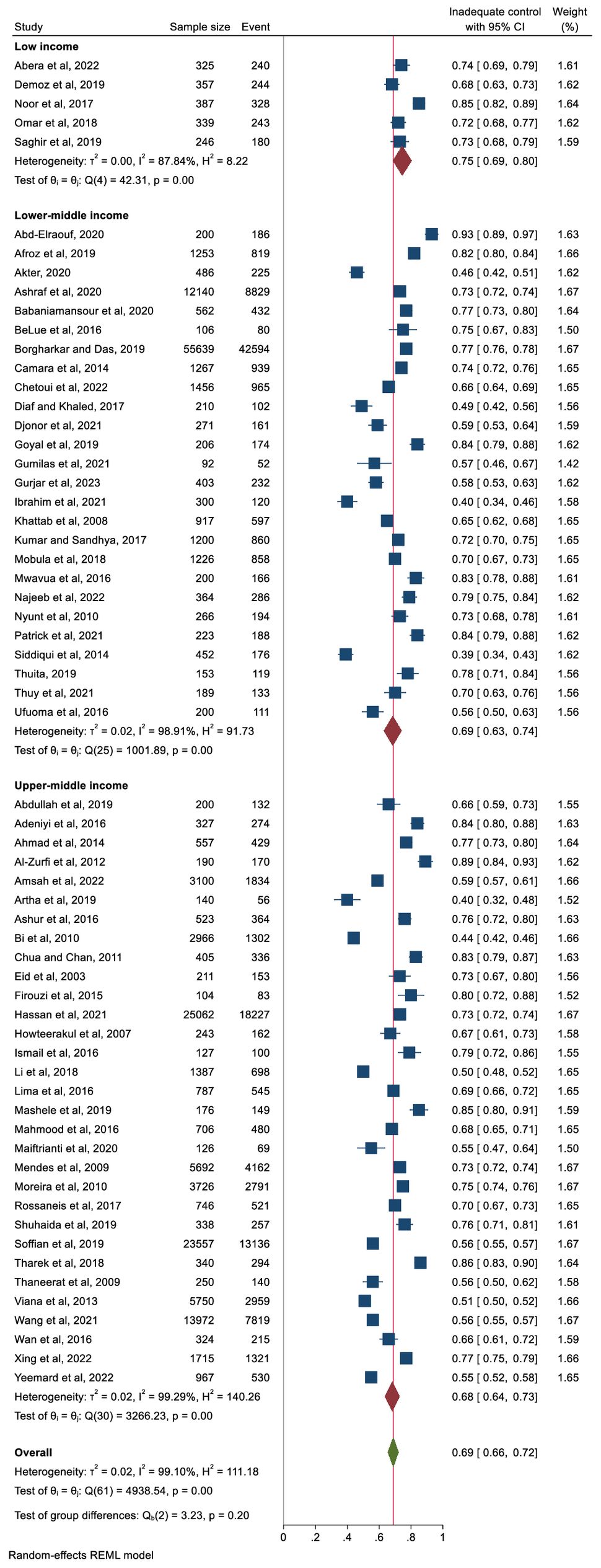

Figure 3 represents the pooled proportion of inadequate glycaemic control. The findings demonstrated that 69% (n = 127,577) of the study participants had inadequate glycaemic control (95% CI: 66%–72%, p <0.001). The prevalence ranged from 40% (in Nigeria) to 93% (in Egypt). High heterogeneity was observed (I2 = 99.10%) with no publication bias (Egger’s regression test, p = 0.489).

In terms of the income level of the country, the pooled proportion of participants with inadequate glycaemic was 68% in upper-middle income countries and 69% in lower-middle-income countries and 75% in low-income countries (Figure 4). However, the differences were not significant. Analysis by geographic region also showed non-significant differences. The pooled proportion of people with inadequate glycaemic control was 72% (95% CI: 66%–78%) in Africa, 68% (95% CI: 59%–76%) in South America and 67% in Asia (95% CI: 63%–72%). The prevalence of people with inadequate glycaemic control in each country included in this review is presented in Supplementary Figure 1.

Figure 4. Pooled prevalence of inadequate glycaemic control (defined as HbA1c ≥6.5%, ≥7%, or ≥8%) stratified by country income level.

A trend analysis using linear regression was performed to assess changes in the prevalence of inadequate glycaemic control across study years. The fitted line indicates a slight, non-significant overall decline in prevalence from 2003 to 2023 (p-value = 0.52) (Supplementary Figure 2). The prevalence was also stratified by study setting and presented in Supplementary Figure 3.

3.4 Factors associated with inadequate glycaemic control

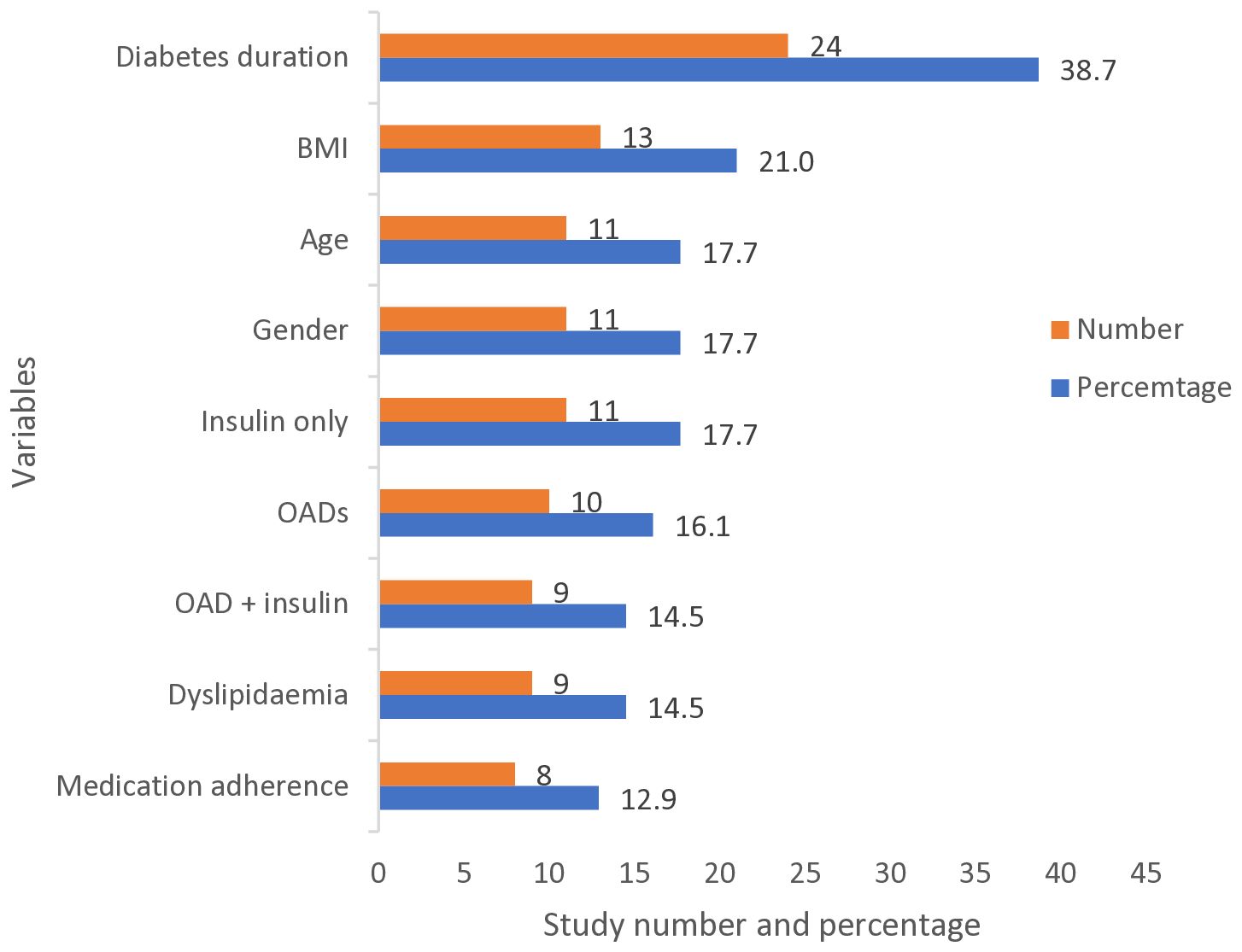

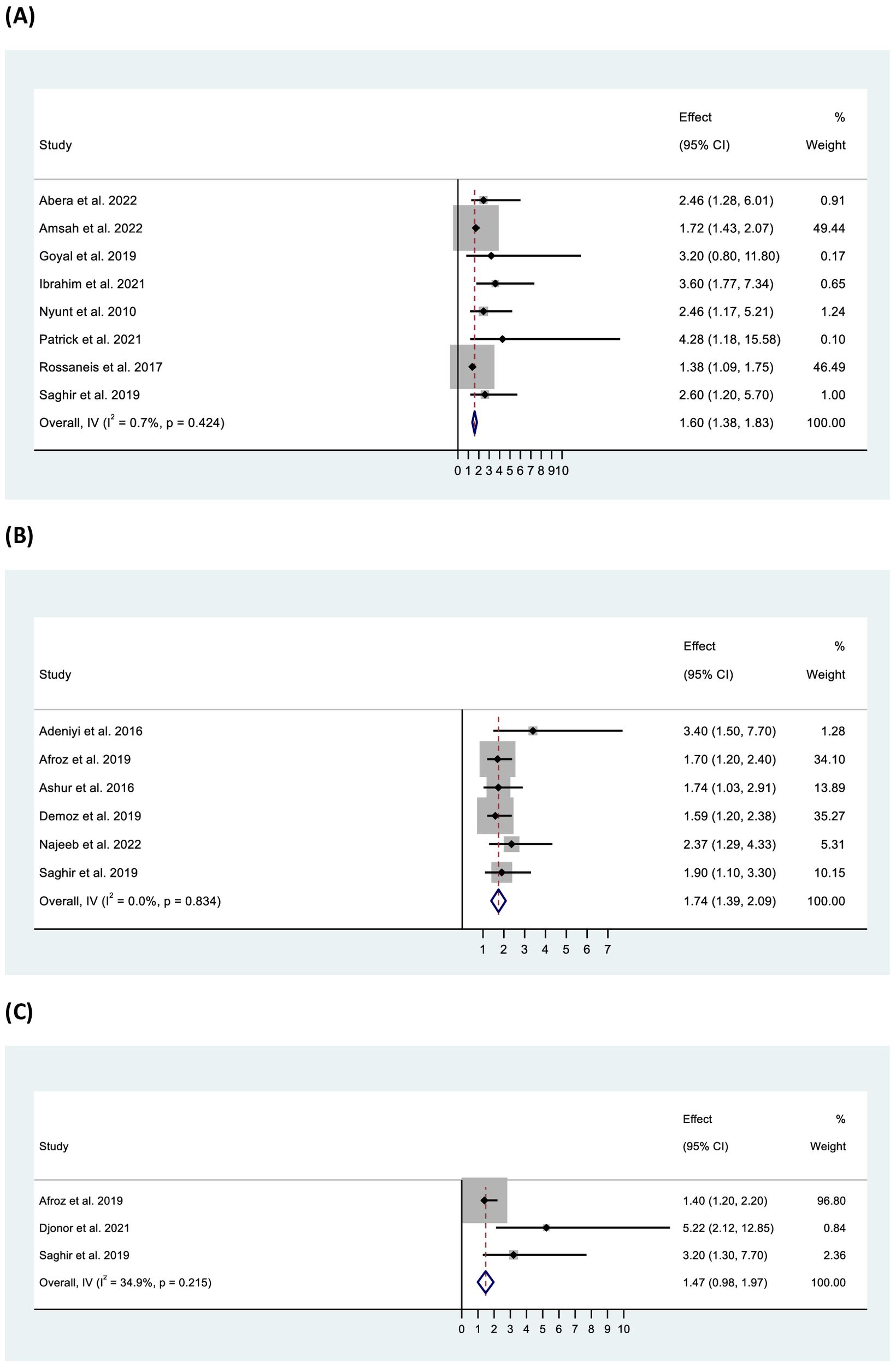

Factors associated with inadequate glycaemic control reported in the included studies are presented in the supporting information (Appendix 6). A total of 35 factors were reported by these studies. Seven factors – longer diabetes duration, older age, overweight/obesity, diabetes treatment modalities (oral antidiabetic drugs [OADs] and/or insulin), female gender, medication non-adherence, and the presence of dyslipidaemia – were reported by ≥10% of the studies (Figure 5). Other factors, including education below secondary, rural residence, presence of hypertension, high waist circumference, physical inactivity, dietary non-adherence and presence of micro- and macrovascular complications were reported by <10% of the studies. Overall pooled data from eight studies showed a significant association between inadequate glycaemic control and older age (>60 years) (OR: 1.60, 95% CI: 1.38–1.83, p < 0.001), whereas three studies found inadequate control among participants aged <60 years (OR: 2.06, 95% CI: 1.51–2.62, p < 0.001). Women had higher odds than men of inadequate glycaemic control (OR: 1.74, 95% CI: 1.39–2.09, p < 0.001). Analysis showed significantly higher odds of inadequate control in participants with an education level below secondary, on lower income and residing in rural areas. The studies were homogenous in all of the above analyses except for the analysis related to education which showed low to moderate heterogeneity (Figure 6).

Figure 5. Most frequent factors associated with inadequate glycaemic control (defined as HbA1c ≥6.5%, ≥7%, or ≥8%) reported by the studies. BMI, Body Mass Index; OAD, Oral Anti-diabetic Drug.

Figure 6. Forest plot of odds ratio of inadequate glycaemic control in relation to (A) age (>60 years), (B) gender (female), and (C) education (below secondary school).

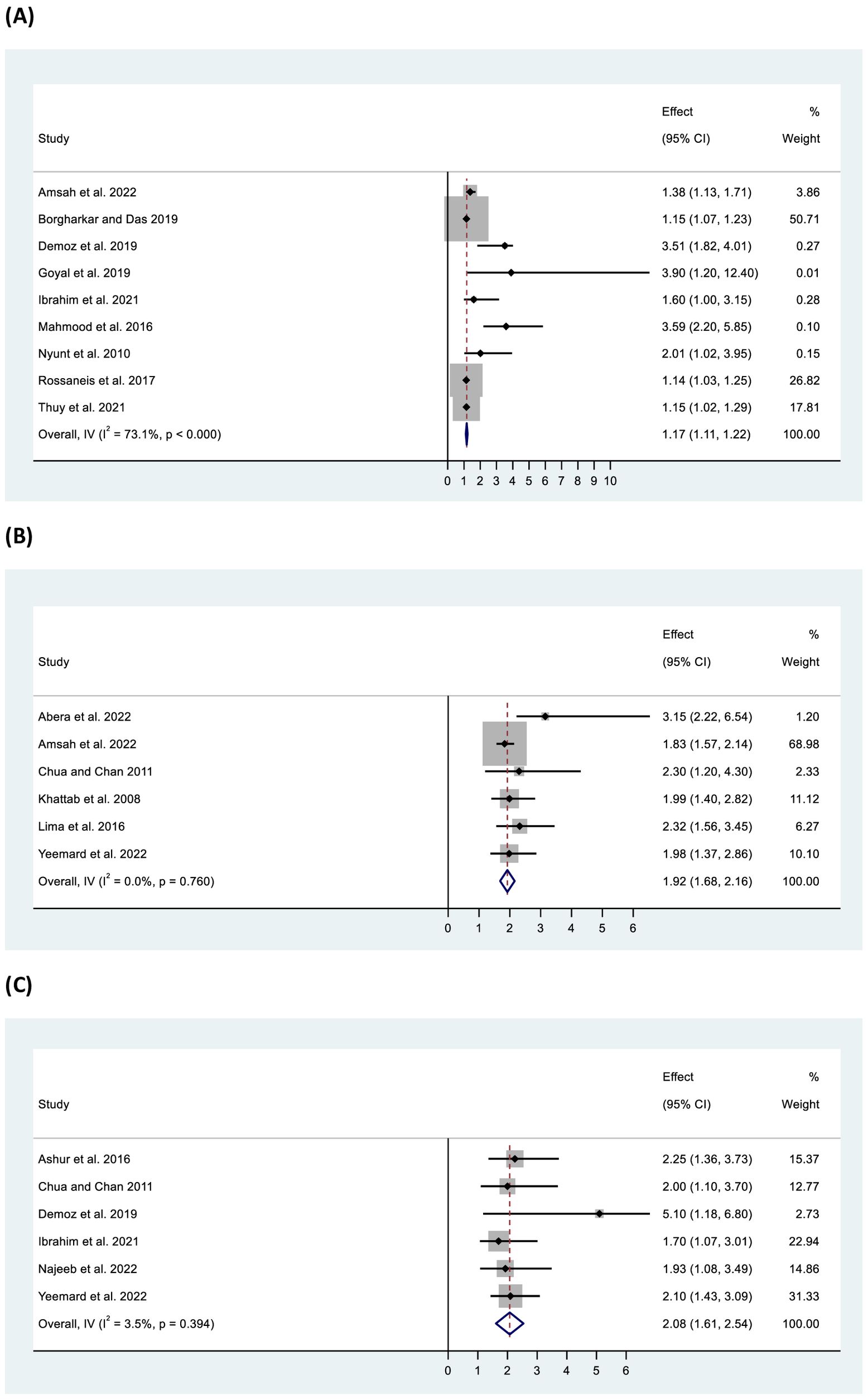

Pooled data from 11 studies showed significant odds of inadequate control among overweight/obese participants (OR: 1.17, 95% CI: 1.11–1.22, p < 0.001) with high heterogeneity (I2 = 68.80%, p <0.001) (Figure 7). Further, higher waist circumference was found to be significantly associated with inadequate control (OR: 1.09, 95% CI: 1.03–1.15, p < 0.001) with homogeneity (I2 = 0%, p = 0.72). Increased odds of inadequate glycaemic control were found among participants with longer diabetes duration (>10 years) (OR: 1.92, 95% CI: 1.68–2.16, p < 0.001), as well as in those receiving more than one OAD (OR: 2.13, 95% CI: 1.89–2.37, p < 0.001), OADs and insulin together (OR: 4.06, 95% CI: 2.58–5.54, p < 0.001), or insulin only (OR: 2.44, 95% CI: 1.70–3.19, p < 0.001) compared with those on a single OAD. Additionally, participants with low or no medication adherence (OR: 2.08, 95% CI: 1.61–2.54, p < 0.001), low dietary adherence (OR: 2.13, 95% CI: 1.33–2.93, p < 0.001), and physical inactivity (OR: 2.15, 95% CI: 1.35–2.95) had two-fold higher odds of inadequate glycaemic control compared with their counterparts (Figure 7). Furthermore, individuals with dyslipidaemia (OR: 1.43, 95% CI: 1.22–1.64, p < 0.001) or high low-density lipoprotein (LDL) levels (OR: 1.97, 95% CI: 0.97–2.96, p < 0.001) were also found to be at higher odds of inadequate glycaemic control. In all cases, the studies were found to be homogeneous (except for dyslipidaemia).

Figure 7. Forest plot of odds ratio of inadequate glycaemic control in relation to (A) BMI (overweight/obese), (B) diabetes duration (>10 years), and (C) medication adherence (low/no).

3.5 Subgroup analysis

Supplementary Table 1 presents the subgroup analysis for inadequate glycaemic control by socio-demographic, behavioural, anthropometric and clinical variables. Participants with a history of smoking had a higher prevalence of inadequate glycaemic control (74%) compared with non-smokers (67%). Similarly, those with no or minimal physical activity had higher inadequate glycaemic control (73%) than those engaging in moderate/vigorous activity (63%). Diet and treatment adherence were also significant, with non-adherent individuals having higher inadequate glycaemic control (diet: 78% vs 63%; treatment: 76% vs 67%). Obese participants showed higher inadequate control (71%) compared with those with a normal body mass index (BMI) (63%), though the difference was not statistically significant. No publication bias was detected. Inadequate glycaemic control was higher in those with diabetes for ≥10 years (74%) versus those with a shorter duration (63%) and in participants treated with both OAD and insulin (81%) compared with those treated with a single OAD (59%). Participants with dyslipidaemia had higher inadequate glycaemic control than those without it. In contrast, participants without hypertension had higher inadequate glycaemic control than those with hypertension. In both cases, the differences were non-significant. Regarding diabetes-related complications, participants having retinopathy had the highest prevalence of inadequate control, followed by neuropathy, nephropathy and coronary artery disease respectively. Heterogeneity was high (>86%) across all subgroup analyses.

Furthermore, analysis was performed on the quality of the studies to identify possible sources of substantial/considerable heterogeneity. The pooled prevalence of inadequate glycaemic control was higher for studies ranked as good (70%, 95% CI: 63%–76%) compared with those ranked as fair (68%, 95% CI: 63%–72%) and poor (69%, 95% CI: 63%–76%). However, high heterogeneity was present (I2 > 99%) with minimal publication bias.

4 Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis examined the literature on glycaemic control and its related factors in people with T2DM in LMICs. The results showed that in most studies from LMICs, overall, more than two-thirds (69%) of people with diabetes had inadequate glycaemic control. By income level of the country, the pooled proportion of participants with inadequate glycaemic control was 68% in upper- middle-income countries, 69% in lower-middle-income countries, and 75% in low-income countries. Regionally, the proportion of participants with inadequate glycaemic control was highest in Africa (72%). In addition, inadequate glycaemic control was associated with sociodemographic factors (older age, female gender, education level below secondary and rural residence), lifestyle and behavioural factors (physical inactivity, dietary non-adherence, and medication non-adherence) and clinical factors (longer duration of diabetes, treatment modalities, high BMI and presence of dyslipidaemia).

This review highlights the significant challenge in controlling glycaemic levels among people with T2DM living in LMICs, with 69% failing to achieve the recommended HbA1c target. Previous review that included studies from sub-Saharan Africa also reported a similar pooled prevalence of people with inadequate control of 70% (10), and attributed this to the quality of diabetes care and fragmented health systems in these countries (82). Another systematic review conducted with studies in Ethiopia also reported similar prevalence (66.6%) and identified poor medication adherence, low education and health literacy as contributing factors (83). In line with these results, Manne-Goehler et al. (2019) reported that 77% of individuals with diabetes across 28 LMICs had inadequate glycaemic control (HbA1c ≥8%), based on nationally representative, community-based surveys (13). Compared to the current review, which largely includes facility-based studies, the higher rate in Manne-Goehler et al.’s study may reflect differences in study setting, sampling strategy, and access to care. Facility-based studies typically include individuals already diagnosed and linked to care, whereas community-based surveys capture a broader and more representative population—including those undiagnosed or not receiving regular care. Limited access to essential diagnostics, such as HbA1c testing, remains a major barrier to improving diabetes outcomes in these settings (84). This review also included studies that used various HbA1c thresholds (≥6.5%, ≥7%, or ≥8%) to define inadequate glycaemic control, further contributing to heterogeneity. Notable variations in prevalence were also observed across studies. For example, a hospital-based study in South Africa reported a high prevalence (83%)among participants with high obesity rates (BMI >30 kg/m²: 63% and central obesity: 95.4%) and complex treatment regimens combining insulin and metformin (56), whereas a study in Nigeria reported a lower prevalence (40%) among participants with lower obesity rates (18%), simpler treatment modalities, and better medication adherence (48). These contrasting findings underscore the influence of clinical characteristics, obesity burden, and treatment complexity on glycaemic outcomes, even within similar care settings.

The high heterogeneity observed across studies, despite multiple subgroup and sensitivity analyses, highlights the complex and diverse nature of diabetes management in LMICs. This variation likely reflects differences in healthcare infrastructure, diagnostic criteria, data collection methods, and population characteristics. Furthermore, one-third of the included studies were rated as poor quality, and nearly all were cross-sectional, limiting causal inference. Many studies also had small sample sizes and incomplete adjustment for potential confounders, which may have introduced bias and reduced the precision of effect estimates. Consequently, the pooled estimates and observed associations should be interpreted with caution, as study quality directly affects the reliability and generalisability of the findings. These methodological limitations underscore the need for future large-scale, longitudinal studies using robust designs and rigorous control for confounding factors.

The findings of this review underscore ongoing challenges in achieving glycaemic control in LMICs, particularly when compared to high-income countries (HICs), where control rates typically range from 52.2%–53.6% due to better health infrastructure, regular monitoring, access to newer therapies, and comprehensive patient education (7–9). In contrast, LMICs face systemic barriers such as financial constraints, understaffed health systems, and weak integration of diabetes care into primary health services, all of which contribute to suboptimal outcomes (7). However, data from the United States and European countries show that, even with advanced treatments and monitoring tools, a substantial proportion of people with diabetes still fail to meet the HbA1c target of <7% due to disease complexity, comorbidities, individual variability, and behavioural challenges such as poor adherence) (85). Therefore, this target may not be universally appropriate, particularly in low-resource settings. In populations with limited access to blood glucose monitoring and healthcare support, strict glycaemic targets may increase the risk of hypoglycaemia, particularly among those using sulfonylureas or insulin. Current guidelines emphasise individualising treatment goals based on patient characteristics, comorbidities, and healthcare system capacity (86). Thus, the threshold used in this review should be interpreted within the context of local resources and patient safety considerations.

In this review, 35 factors were identified as being associated with inadequate glycaemic control. The most commonly associated factors included longer diabetes duration, older age, higher BMI (overweight/obesity), female gender and various diabetes treatment modalities (OADs/OADs and insulin/insulin only). Additionally, low medication adherence and the presence of dyslipidaemia were notable contributors. Other factors, though less frequently reported, included low income, rural residence, below secondary education, high waist circumference, physical inactivity, dietary non-adherence and the presence of micro- and macrovascular complications. While individual-level factors were commonly assessed, important system-level and contextual factors—such as access to care, service continuity, quality and coordination of care, availability of healthcare providers (including community health workers), and person-centred service delivery—were not consistently measured across studies. These dimensions are particularly relevant in LMICs, where fragmented health systems and limited resources can substantially affect diabetes outcomes. Incorporating these healthcare delivery aspects into future research is essential to better understand the drivers of inadequate glycaemic control.

The current review found that older age was associated with inadequate glycaemic control, which could be explained by the natural decline in pancreatic β-cell function, increased prevalence of comorbidities, interference with diabetes management due to multiple medications, cognitive decline, reduced physical activity and dietary changes (14, 83). It is important to consider that glycaemic targets should be individualised, particularly in older adults, where strict control may increase the risk of hypoglycaemia. Current clinical guidelines recommend more relaxed glycaemic goals in this population, balancing the benefits of glucose lowering with potential treatment-related risks (86). Therefore, the interpretation of inadequate control should be contextualised within patient age, comorbidity burden, and functional status, rather than applying a uniform target across all subgroups. This review also found that women tended to have inadequate glycaemic control, which is consistent with the findings from previous research in Ethiopia (87). This could be due to hormonal changes throughout their lifespan and experience of higher levels of stress, depression and anxiety compared with men, which can affect insulin sensitivity and glucose metabolism (88). Additionally, some socioeconomic factors (e.g. lower income, limited access to healthcare and disparities in education) and lifestyle factors (e.g. poor dietary intake, less physical activity) may impact their ability to manage diabetes effectively (89, 90). Moreover, some women may prioritise the health of others before themselves, and their responsibilities such as caregiving and household duties may leave them with less time and energy to focus on self-care. Participants with education levels below secondary and those living in rural areas also had inadequate glycaemic control, which is supported by a previous study (24). Lower levels of education may impact health literacy and the ability to understand and adhere to treatment plans, as well as adopt healthy lifestyle behaviours (24). Limited healthcare facilities, shortages of healthcare professionals, transportation problems and longer travel distances in rural areas can result in suboptimal management and irregular follow-up (24). Regarding lifestyle and behavioural factors, inadequate control was associated with non-adherence to the recommended diet and prescribed medications. Poor medication adherence can be attributed to people-related factors, such as accessibility and affordability of medications, dosage and quantity of medicines and knowledge about their illness and medications. It can also be due to provider-related factors, such as the lack of continuous support and awareness regarding the disease and the importance of adherence to medication (38). These results highlight the need to identify people with T2DM who are socially disadvantaged, improve access to healthcare and implement effective self-care management strategies for people with varying health literacy.

Participants with a high BMI (overweight/obese) were more likely to have inadequate glycaemic control compared with those with a normal BMI, consistent with findings from previous studies (91). Obesity is a complex, multifactorial condition, and its association with inadequate glycaemic control in T2DM is mediated by several interrelated mechanisms. Excess adiposity contributes to insulin resistance through increased free fatty acid flux, ectopic fat deposition, and chronic low-grade inflammation driven by adipokines and pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) (92–94). These processes impair glucose uptake in peripheral tissues and reduce insulin sensitivity, thereby making it more difficult to achieve optimal HbA1c levels even with pharmacological therapy. Additionally, obesity is often accompanied by increased hepatic fat accumulation, dyslipidaemia, physical inactivity, and excessive caloric intake, all of which further exacerbate hyperglycaemia and insulin resistance (95). Managing both obesity and T2DM often requires a comprehensive approach that includes weight management, physical activity, dietary changes and medication when necessary. Healthcare providers can help individuals in developing personalised management plans to address both conditions and improve glycaemic control.

Participants with longer duration of diabetes (>10 years) were found to have inadequate glycaemic control, which may be explained by the progressive nature of β-cell dysfunction and declining insulin secretion over time. Chronic exposure to hyperglycaemia and elevated free fatty acids leads to glucotoxicity, lipotoxicity, oxidative stress, and islet inflammation, all of which accelerate β-cell failure (96, 97). In addition, persistent insulin resistance, often exacerbated by aging and adiposity, further impairs glucose homeostasis (92). These progressive metabolic alterations collectively make it increasingly difficult to maintain optimal glycaemic control as the duration of diabetes lengthens. Furthermore, individuals with longer disease duration are more likely to develop comorbidities and complications that can interfere with diabetes self-management, medication adjustment, and overall metabolic control (98).

This review also found that participants on combinations of OAD and/or insulin had inadequate glycaemic control. The use of higher- intensity glucose-lowering medications may reflect the severity of the disease and the difficulty of achieving adequate glycaemic control while balancing possible risks of treatment, such as hypoglycaemia. A few of the more recent studies included in this review from countries such as Bangladesh (2021) (26), India (2021) (30), and Ethiopia (2019) (38) did report the use of newer classes of oral antidiabetic drugs (OADs), including sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT2i), dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors (DPP-4i), and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RA). However, these reports were limited, and access to these newer agents remains constrained in many low- and middle-income country settings, potentially contributing to suboptimal treatment outcomes. Participants who had dyslipidaemia had also inadequate glycaemic control. Dyslipidaemia, particularly elevated levels of TG and LDL, is often associated with insulin resistance and poorer glycaemic control (99).

Interestingly, the study found that individuals without hypertension had a higher prevalence of inadequate glycaemic control compared to those with hypertension. This counterintuitive result may be explained by the increased frequency of healthcare interactions and more comprehensive disease management among patients with multiple comorbidities. Those with both diabetes and hypertension are more likely to be under routine monitoring, receive medication adjustments, and adhere to lifestyle changes, which may contribute to better glycaemic control. However, it is important to note that being under treatment does not necessarily translate into achieving target glycaemic levels, highlighting the need for ongoing evaluation of treatment effectiveness and patient adherence.

Despite differences in disease pathophysiology, comparisons with successful chronic disease programs—such as HIV viral suppression initiatives—highlight the urgent need for strengthened diabetes care systems in LMICs (100, 101). The consistently low glycaemic control rates observed across time and settings in this review underscore significant gaps in access, continuity, and quality of diabetes management. These findings point to the need for integrated, scalable, and patient-centred approaches—similar to those used in HIV care—that prioritise regular monitoring, adherence support, task-shifting to community health workers, and decentralised care delivery (102, 103). Future research should focus not only on individual-level predictors but also on evaluating health system interventions that can sustainably improve glycaemic outcomes in resource-constrained settings.

4.1 Strengths and limitations

This review has several limitations. First, while the review exclusively incorporated studies that measured glycaemic control using HbA1c, it is important to note that variations in the HbA1c test methods and cut-off values could potentially introduce errors in the estimates. Additionally, differences in HbA1c levels across ethnic and racial groups may affect comparability, as certain populations may exhibit varying HbA1c levels independent of glucose concentrations (104). Second, it is crucial to recognise that all the studies included in this review were cross-sectional (except one retrospective cohort survey), which limits the ability to establish causality between the identified factors and glycaemic control. The associations observed may reflect consequences rather than causes. For instance, individuals with high BMI or comorbidities such as dyslipidaemia may already have poor glycaemic outcomes, making it difficult to determine directionality. Similarly, treatment-related factors—such as the use of oral hypoglycaemic agents—may indicate poor control rather than predict it, introducing potential reverse causality. Third, the majority of the included studies were not community-based; only four were. Most studies used selected populations from hospitals or primary care centres, which may represent individuals already linked to care and thus fail to capture the broader population, particularly those who are undiagnosed or untreated. Limited access to diagnostics, such as HbA1c testing, in LMICs may further contribute to underestimating the true burden of poor glycaemic control. As a result, the generalisability of the findings to the wider community is limited. Fourth, significant heterogeneity was observed among some of the categories of studies, and despite conducting various subgroup analyses, the sources of heterogeneity could not be determined. This persistent heterogeneity likely reflects diversity in study populations, measurement tools, clinical practices, healthcare access, and unmeasured contextual factors across LMICs. Several potentially relevant variables—such as health system differences, quality of care, health insurance coverage, medication availability, and cultural influences—were not consistently reported, limiting further exploration. Fifth, the exclusion of grey literature such as theses, conference abstracts, and unpublished studies, may have introduced publication bias by omitting potentially relevant but non-peer-reviewed evidence. Finally, none of the studies addressed missing data or used newly emerged machine learning methods to identify the predictors of glycaemic control.

Despite these limitations, to the best of our knowledge, this systematic review and meta-analysis is the first comprehensive attempt to estimate the prevalence of inadequate glycaemic control and its associated factors in people with T2DM in LMICs. It should be noted that this review exclusively considered studies that conducted multivariable analyses during data analysis, thus excluding factors lacking a clear link to glycaemic control.

5 Conclusion

The overall prevalence of people with T2DM in LMICs with inadequate glycaemic control was 69%, underscoring a significant public health challenge. Poor glycaemic control is influenced by a range of sociodemographic, lifestyle, clinical and treatment-related factors. Addressing these determinants is the key to achieving better glycaemic control and reducing diabetes-related complications. However, service delivery factors—such as access, continuity, care coordination, and the role of community health systems—remain underexplored despite their potential impact. Future research should prioritise community-based studies that incorporate both individual and health system-level variables to more comprehensively understand the prevalence and factors associated with inadequate glycaemic control among disadvantaged populations within LMICs.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

BS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DM: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. HC: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. MC: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. AA: Conceptualization, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. SS: Writing – review & editing. BB: Conceptualization, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcdhc.2025.1695235/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Figure 1 | Prevalence of inadequate glycaemic control (defined as HbA1c ≥6.5%, ≥7%, or ≥8%) by country.

Supplementary Figure 2 | Prevalence of inadequate glycaemic control (defined as HbA1c ≥6.5%, ≥7%, or ≥8%) by study years.

Supplementary Figure 3 | Pooled prevalence of inadequate glycaemic control (defined as HbA1c ≥6.5%, ≥7%, or ≥8%) stratified by study setting.

References

1. Sun H, Saeedi P, Karuranga S, Pinkepank M, Ogurtsova K, Duncan BB, et al. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global, regional and country-level diabetes prevalence estimates for 2021 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. (2022) 183:109119. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2021.109119

2. Grant P. Management of diabetes in resource-poor settings. Clin Med. (2013) 13:27–31. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.13-1-27

3. International Diabetes Federation. IDF diabetes Atlas (2025). Brussels, Belgium. Available online at: https://www.diabetesatlas.org (Accessed June 11, 2025).

4. The World Bank. World bank country classification by income level (2024). Available online at: https://data.worldbank.org/country (Accessed June 11, 2025).

5. Vos T, Lim SS, Abbafati C, Abbas KM, Abbasi M, Abbasifard M, et al. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. (2020) 396:1204–22. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30925-9

6. American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 6. Glycemic Targets: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2022. Alexandria, Virginia, United States: American Diabetes Association (2021). pp. S83–96. doi: 10.2337/dc22-S006

7. Aschner P, Galstyan G, Yavuz DG, Litwak L, Gonzalez-Galvez G, Goldberg-Eliaschewitz F, et al. Glycemic control and prevention of diabetic complications in low-and middle-income countries: an expert opinion. Diabetes Ther. (2021) 12:1491–501. doi: 10.1007/s13300-021-00997-0

8. Ali MK, Bullard KM, Saaddine JB, Cowie CC, Imperatore G, Gregg EW, et al. Achievement of goals in US diabetes care, 1999–2010. New Engl J Med. (2013) 368:1613–24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1213829

9. Stone MA, Charpentier G, Doggen K, Kuss O, Lindblad U, Kellner C, et al. Quality of care of people with type 2 diabetes in eight European countries: findings from the Guideline Adherence to Enhance Care (GUIDANCE) study. Diabetes Care. (2013) 36:2628–38. doi: 10.2337/dc12-1759

10. Fina Lubaki J-P, Omole OB, and Francis JM. Glycaemic control among type 2 diabetes patients in sub-Saharan Africa from 2012 to 2022: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetol Metab Syndrome. (2022) 14:134. doi: 10.1186/s13098-022-00902-0

11. Brown SA, García AA, Brown A, Becker BJ, Conn VS, Ramírez G, et al. Biobehavioral determinants of glycemic control in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Patient Educ Couns. (2016) 99:1558–67. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2016.03.020

12. Cheng LJ, Wang W, Lim ST, and Wu VX. Factors associated with glycaemic control in patients with diabetes mellitus: a systematic literature review. J Clin Nurs. (2019) 28:1433–50. doi: 10.1111/jocn.14795

13. Manne-Goehler J, Geldsetzer P, Agoudavi K, Andall-Brereton G, Aryal KK, Bicaba BW, et al. Health system performance for people with diabetes in 28 low-and middle-income countries: a cross-sectional study of nationally representative surveys. PloS Med. (2019) 16:e1002751. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002751

14. Alramadan MJ, Afroz A, Hussain SM, Batais MA, Almigbal TH, Al-Humrani HA, et al. Patient-related determinants of glycaemic control in people with type 2 diabetes in the Gulf cooperation council countries: A systematic review. J Diabetes Res. (2018) 2018:9389265. doi: 10.1155/2018/9389265

15. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. bmj. (2021) 372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71

16. Wells G, Shea B, O’connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, et al. Newcastle-Ottawa quality assessment scale cohort studies. Univ Ottawa. (2014).

17. Deeks JJ, Higgins JP, Altman DG, and Cochrane Statistical Methods Group. Analysing data and undertaking meta-analyses. In: Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons (2019). p. 241–84.

18. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Methods guide for effectiveness and comparative effectiveness review (2014). Available online at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK47095/.

19. Egger M, Smith GD, Schneider M, and Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. bmj. (1997) 315:629–34. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629

20. Abd-Elraouf MSE-D. Factors affecting glycemic control in type II diabetic patients. Egyptian J Hosp Med. (2020) 81:1457–61. doi: 10.21608/ejhm.2020.114454

21. Abdullah NA, Ismail S, Ghazali SS, Juni MH, Shahar HK, Aziz NR, et al. Predictors of good glycemic controls among type 2 diabetes mellitus patients in two primary health clinics, kuala selangor. Malaysian J Med Health Sci. (2019) 15:58–64.

22. Abera RG, Demesse ES, and Boko WD. Evaluation of glycemic control and related factors among outpatients with type 2 diabetes at Tikur Anbessa Specialized Hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Endocr Disord. (2022) 22:54. doi: 10.1186/s12902-022-00974-z

23. Adeniyi OV, Yogeswaran P, Longo-Mbenza B, Ter Goon D, and Ajayi AI. Cross-sectional study of patients with type 2 diabetes in OR Tambo district, South Africa. BMJ Open. (2016) 6:e010875. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010875

24. Afroz A, Ali L, Karim MN, Alramadan MJ, Alam K, Magliano DJ, et al. Glycaemic Control for People with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in Bangladesh - An urgent need for optimization of management plan. Sci Rep. (2019) 9:10248. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-46766-9

25. Ahmad NS, Islahudin F, and Paraidathathu T. Factors associated with good glycemic control among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Invest. (2014) 5:563–69. doi: 10.1111/jdi.12175

26. Akter N. Pattern of treatment and its relation with glycaemic control among diabetic patients in a tertiary care hospital of Bangladesh. Endocr Pract. (2020) 26:86–7. doi: 10.1016/S1530-891X(20)39417-9

27. Al-Zurfi BMN, Abd Aziz A, Abdullah MR, and Noor NM. Waist height ratio compared to body mass index and waist circumference in relation to glycemic control in Malay type 2 diabetes mellitus patients, Hospital Universiti Sains Malaysia. Int J Collab Res Internal Med Public Health. (2012) 4:406.

28. Amsah N, Isa ZM, and Kassim Z. Poor Glycaemic Control and its Associated Factors among Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients in Southern Part of Peninsular Malaysia: A Registry-based Study. Open Access Macedonian J Med Sci. (2022) 10:422–27. doi: 10.3889/oamjms.2022.8696

29. Artha I, Bhargah A, Dharmawan NK, Pande UW, Triyana KA, Mahariski PA, et al. High level of individual lipid profile and lipid ratio as a predictive marker of poor glycemic control in type-2 diabetes mellitus. Vasc Health Risk Manage. (2019) 15:149–57. doi: 10.2147/VHRM.S209830

30. Ashraf H, Faraz A, and Ahmad J. Achievement of guideline targets of glycemic and non-glycemic parameters in North Indian type 2 diabetes mellitus patients: A retrospective analysis. Diabetes Metab Syndrome. (2021) 15:425–31. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2021.02.003

31. Babaniamansour S, Aliniagerdroudbari E, and Niroomand M. Glycemic control and associated factors among Iranian population with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a cross-sectional study. J Diabetes Metab Disord. (2020) 19:933–40. doi: 10.1007/s40200-020-00583-4

32. BeLue R, Ndiaye K, Ndao F, Ba FN, and Diaw M. Glycemic control in a clinic-based sample of diabetics in M'Bour Senegal. (Supplement Issue: Noncommunicable diseases in Africa and the global south.). Health Educ Behav. (2016) 43:112S–116S. doi: 10.1177/1090198115606919

33. Bi Y, Zhu D, Cheng J, Zhu Y, Xu N, Cui S, et al. The status of glycemic control: a cross-sectional study of outpatients with type 2 diabetes mellitus across primary, secondary, and tertiary hospitals in the Jiangsu province of China. Clin Ther. (2010) 32:973–83. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2010.05.002

34. Borgharkar SS and Das SS. Real-world evidence of glycemic control among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in India: the TIGHT study. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. (2019) 7:e000654. doi: 10.1136/bmjdrc-2019-000654

35. Camara A, Balde NM, Sobngwi-Tambekou J, Kengne AP, Diallo MM, Tchatchoua AP, et al. Poor glycemic control in type 2 diabetes in the South of the Sahara: the issue of limited access to an HbA1c test. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. (2015) 108:187–92. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2014.08.025

36. Chetoui A, Kaoutar K, Elmoussaoui S, Boutahar K, El Kardoudi A, Chigr F, et al. Prevalence and determinants of poor glycaemic control: a cross-sectional study among Moroccan type 2 diabetes patients. Int Health. (2020) 14:390–97. doi: 10.1093/inthealth/ihz107

37. Chua S and Chan S. Medication adherence and achievement of glycaemic targets in ambulatory type 2 diabetic patients. J Appl Pharm Sci. (2011) 2011:55–9.

38. Demoz GT, Gebremariam A, Yifter H, Alebachew M, Niriayo YL, Gebreslassie G, et al. Predictors of poor glycemic control among patients with type 2 diabetes on follow-up care at a tertiary healthcare setting in Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes. (2019) 12:1–7. doi: 10.1186/s13104-019-4248-6

39. Diaf M and Khaled BM. Metabolic profile, nutritional status and determinants of glycaemic control in Algerian type 2 diabetic patients. Kuwait Med J. (2017) 49:135–41.

40. Djonor SK, Ako-Nnubeng IT, Owusu EA, Akuffo KO, Nortey P, Agyei-Manu E, et al. Determinants of blood glucose control among people with Type 2 diabetes in a regional hospital in Ghana. PloS One. (2021) 16:e0261455. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0261455

41. Eid M, Mafauzy M, and Faridah AR. Glycaemic control of type 2 diabetic patients on follow up at Hospital Universiti Sains Malaysia. Malaysian J Med Sci. (2003) 10:40–9.

42. Firouzi S, Barakatun-Nisak MY, and Azmi KN. Nutritional status, glycemic control and its associated risk factors among a sample of type 2 diabetic individuals, a pilot study. J Res Med Sci. (2015) 20:40–6.

43. Goyal J, Kumar N, Sharma M, Raghav S, and Bhatia PS. Factors affecting glycemic control among patients with type 2 diabetes at a tertiary health care center of western up region: A cross-sectional study. Int J Health Sci Res. (2019) 9:12–20.

44. Gumilas NSA, Harini IM, Samodro P, and Ernawati DA. MMAS-8 score assessment of therapy adherence to glycemic control of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, Tanjung Purwokerto, Java, Indonesia (october 2018). Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. (2021) 52:359–70.

45. Gurjar SS, Mittal A, Goel GS, Mittal A, Ahuja A, Kamboj D, et al. Glycemic control and its associated determinants among type II diabetic patients at tertiary care hospital in North India. Healthline Journal. (2023) 14:17–22.

46. Hassan MR, Jamhari MN, Hayati F, Ahmad N, Zamzuri MA, Nawi AM, et al. Determinants of glycaemic control among type 2 diabetes mellitus patients in Northern State of Kedah, Malaysia: a cross-sectional analysis of 5 years national diabetes registry 2014-2018. Pan Afr Med J. (2021) 39. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2021.39.206.30410

47. Howteerakul N, Suwannapong N, Rittichu C, and Rawdaree P. Adherence to regimens and glycemic control of patients with type 2 diabetes attending a tertiary hospital clinic. Asia-Pac J Public Health. (2007) 19:43–9. doi: 10.1177/10105395070190010901

48. Ibrahim AO, Agboola SM, Elegbede OT, Ismail WO, Agbesanwa TA, Omolayo TA, et al. Glycemic control and its association with sociodemographics, comorbid conditions, and medication adherence among patients with type 2 diabetes in southwestern Nigeria. J Int Med Res. (2021) 49:3000605211044040. doi: 10.1177/03000605211044040

49. Ismail A, Suddin LS, Sulong S, Ahmed Z, Kamaruddin NA, Sukor N, et al. Profiles and factors associated with poor glycemic control among inpatients with diabetes mellitus type 2 as a primary diagnosis in a teaching hospital. Indian J Community Med. (2016) 41:208–12. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.183590

50. Khattab M, Khader YS, Al-Khawaldeh A, and Ajlouni K. Factors associated with poor glycemic control among patients with type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Its Complicat. (2010) 24:84–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2008.12.008

51. Kumar SP and Sandhya AM. A study on the glycemic, lipid and blood pressure control among the type 2 diabetes patients of north Kerala, India. Indian Heart J. (2018) 70:482–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ihj.2017.10.007

52. Li J, Chattopadhyay K, Xu M, Chen Y, Hu F, Chu J, et al. Glycaemic control in type 2 diabetes patients and its predictors: a retrospective database study at a tertiary care diabetes centre in Ningbo, China. BMJ Open. (2018) 8:e019697. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019697

53. Lima RF, Fontbonne A, Carvalho E, Montarroyos UR, Barreto MN, Cesse EÂ, et al. Factors associated with glycemic control in people with diabetes at the Family Health Strategy in Pernambuco. Rev da Escola Enfermagem da USP. (2016) 50:00937–45. doi: 10.1590/s0080-623420160000700009

54. Mahmood MI, Daud F, and Ismail A. Glycaemic control and associated factors among patients with diabetes at public health clinics in Johor, Malaysia. Public Health. (2016) 135:56–65. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2015.07.043

55. Maifitrianti NW, Haro M, Lestari SF, and Fitriani A. Glycemic control and its factor in type 2 diabetic patients in Jakarta. Indones J Clin Pharm. (2020) 9:198–204. doi: 10.15416/ijcp.2020.9.3.198

56. Mashele TS, Mogale MA, Towobola OA, and Moshesh MF. Central obesity is an independent risk factor of poor glycaemic control at Dr George Mukhari Academic Hospital. South Afr Family Pract. (2019) 61:18–23. doi: 10.1080/20786190.2018.1527134

57. Mendes ABV, Fittipaldi JAS, Neves RCS, Chacra AR, and Moreira ED Jr. Prevalence and correlates of inadequate glycaemic control: results from a nationwide survey in 6,671 adults with diabetes in Brazil. Acta Diabetol. (2010) 47:137–45. doi: 10.1007/s00592-009-0138-z

58. Mobula LM, Sarfo FS, Carson KA, Burnham G, Arthur L, Ansong D, et al. Predictors of glycemic control in type-2 diabetes mellitus: Evidence from a multicenter study in Ghana. Trans Metab Syndrome Res. (2018) 1:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tmsr.2018.09.001

59. Moreira ED Jr., Neves RCS, Nunes ZO, de Almeida MC, Mendes AB, Fittipaldi JA, et al. Glycemic control and its correlates in patients with diabetes in Venezuela: results from a nationwide survey. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. (2010) 87:407–14. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2009.12.014

60. Mwavua SM, Ndungu EK, Mutai KK, and Joshi MD. A comparative study of the quality of care and glycemic control among ambulatory type 2 diabetes mellitus clients, at a Tertiary Referral Hospital and a Regional Hospital in Central Kenya. BMC Res Notes. (2016) 9:1–8. doi: 10.1186/s13104-015-1826-0

61. Najeeb SS, Joy TM, Sreedevi A, and Vijayakumar K. Glycemic control and its determinants among people with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Ernakulam district, Kerala. Indian J Public Health. (2022) 66:S80–6. doi: 10.4103/ijph.ijph_1104_22

62. Nini Shuhaida MH, Siti Suhaila MY, Azidah KA, Norhayati NM, Nani D, Juliawati M, et al. Depression, anxiety, stress and socio-demographic factors for poor glycaemic control in patients with type II diabetes. J Taibah Univ Med Sci. (2019) 14:268–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jtumed.2019.03.002

63. Noor SK, Elmadhoun WM, Bushara SO, Almobarak AO, Salim RS, Forawi SA, et al. Glycaemic control in Sudanese individuals with type 2 diabetes: Population based study. Diabetes Metab Syndrome: Clin Res Rev. (2017) 11:S147–S51. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2016.12.024

64. Nyunt SW, Howteerakul N, Suwannapong N, and Rajatanun T. Self-efficacy, self-care behaviors and glycemic control among type-2 diabetes patients attending two private clinics in Yangon, Myanmar. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. (2010) 41:943–51.

65. Omar SM, Musa IR, Osman OE, and Adam I. Assessment of glycemic control in type 2 diabetes in the eastern Sudan. BMC Res Notes. (2018) 11. doi: 10.1186/s13104-018-3480-9

66. Patrick NB, Yadesa TM, Muhindo R, and Lutoti S. Poor glycemic control and the contributing factors among type 2 diabetes mellitus patients attending outpatient diabetes clinic at mbarara regional referral hospital, Uganda. Diabetes Metab Syndrome Obes. (2021) 2021:3123–30. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S321310

67. Rossaneis MA, Andrade S, Gvozd R, Pissinati PD, and Haddad MD. Factors associated with glycemic control in people with diabetes mellitus. Ciencia Saude Coletiva. (2019) 24:997–1005. doi: 10.1590/1413-81232018243.02022017

68. Saghir SAM, Alhariri AEA, Alkubati SA, Almiamn AA, Aladaileh SH, Alyousefi NA, et al. Factors associated with poor glycemic control among type-2 diabetes mellitus patients in Yemen. Trop J Pharm Res. (2019) 18:1539–46. doi: 10.4314/tjpr.v18i7.26

69. Ashur ST, Shah SA, Bosseri S, Fah TS, and Shamsuddin K. Glycaemic control status among type 2 diabetic patients and the role of their diabetes coping behaviours: a clinic-based study in Tripoli, Libya. Libyan Journal of Medicine. (2016) 11. doi: 10.3402/ljm.v11.31086

70. Siddiqui FJ, Avan BI, Mahmud S, Nanan DJ, Jabbar A, Assam PN, et al. Uncontrolled diabetes mellitus: Prevalence and risk factors among people with type 2 diabetes mellitus in an Urban District of Karachi, Pakistan. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. (2015) 107:148–56. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2014.09.025

71. Soffian SSS, Ahmad SB, Chan HK, Soelar SA, Abu Hassan MR, Ismail N, et al. Management and glycemic control of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus at primary care level in Kedah, Malaysia: A statewide evaluation. PloS One. (2019) 14. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0223383

72. Thaneerat T, Tangwongchai S, and Worakul P. Prevalence of depression, hemoglobin A1C level, and associated factors in outpatients with type-2 diabetes. Asian Biomed. (2009) 3:383–90.

73. Tharek Z, Ramli AS, Whitford DL, Ismail Z, Mohd Zulkifli M, Ahmad Sharoni SK, et al. Relationship between self-efficacy, self-care behaviour and glycaemic control among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in the Malaysian primary care setting. BMC Family Pract. (2018) 19:39. doi: 10.1186/s12875-018-0725-6

74. Thuita AW, Kiage BN, Onyango AN, and Ann AM. The relationship between patient characteristics and glycemic control (HbA1c) in type 2 diabetes patients attending Thika Level Five Hospital, Kenya. Afr J Food Agricult Nutr Dev. (2019) 19:15041–59. doi: 10.18697/ajfand.87.18420

75. Thuy LQ, Nam HTP, An TTH, Van San B, Ngoc TN, Trung LH, et al. Factors Associated with Glycaemic Control among Diabetic Patients Managed at an Urban Hospital in Hanoi, Vietnam. BioMed Res Int. (2021) 2021:8886904. doi: 10.1155/2021/8886904

76. Ufuoma C, Godwin YD, Kester AD, and Ngozi JC. Determinants of glycemic control among persons with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Niger Delta. Sahel Med J. (2016) 19:190–95. doi: 10.4103/1118-8561.196361

77. Viana LV, Leitão CB, Kramer CK, Zucatti AT, Jezini DL, Felício J, et al. Poor glycaemic control in Brazilian patients with type 2 diabetes attending the public healthcare system: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. (2013) 3:e003336. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003336

78. Wang J, Li J, Wen C, Liu Y, and Ma H. Predictors of poor glycemic control among type 2 diabetes mellitus patients treated with antidiabetic medications: A cross-sectional study in China. Medicine. (2021) 100:e27677. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000027677

79. WFF WH, Juni MH, Salmiah M, Azuhairi A.A., and Zairina A.R.. Factors associated with glycaemic control among type 2 diabetes mellitus patients. Int J Public Health Clin Sci. (2016) 3:89–102.

80. Xing X-Y, Wang X-Y, Fang X, Xu JQ, Chen YJ, Xu W, et al. Glycemic control and its influencing factors in type 2 diabetes patients in Anhui, China. Front Public Health. (2022) 10:980966. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.980966

81. Yeemard F, Srichan P, Apidechkul T, Luerueang N, Tamornpark R, Utsaha S, et al. Prevalence and predictors of suboptimal glycemic control among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in northern Thailand: A hospital-based cross-sectional control study. PloS One [Electronic Resource]. (2022) 17:e0262714. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0262714

82. Mercer T, Chang AC, Fischer L, Gardner A, Kerubo I, Tran DN, et al. Mitigating the burden of diabetes in Sub-Saharan Africa through an integrated diagonal health systems approach. Diabetes Metab Syndrome Obesity: Targets Ther. (2019) 2019:2261–72. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S207427

83. Tegegne KD, Gebeyehu NA, Yirdaw LT, Yitayew YA, and Kassaw MW. Determinants of poor glycemic control among type 2 diabetes in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Public Health. (2024) 12:1256024. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1256024

84. Fleming KA, Horton S, Wilson ML, Atun R, DeStigter K, Flanigan J, et al. The Lancet Commission on diagnostics: transforming access to diagnostics. Lancet. (2021) 398:1997–2050. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00673-5

85. Fang M, Wang D, Coresh J, and Selvin E. Trends in diabetes treatment and control in U.S. Adults, 1999–2018. New Engl J Med. (2021) 384:2219–28. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa2032271

86. American Diabetes Association. Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2024. Alexandria, Virginia, United States: American Diabetes Association (2024). pp. S1–S330. doi: 10.2337/dc24-S001.

87. Gebreyohannes EA, Netere AK, and Belachew SA. Glycemic control among diabetic patients in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One. (2019) 14:e0221790. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0221790

88. Duarte FG, da Silva Moreira S, Maria da Conceição CA, de Souza Teles CA, Andrade CS, Reingold AL, et al. Sex differences and correlates of poor glycaemic control in type 2 diabetes: a cross-sectional study in Brazil and Venezuela. BMJ Open. (2019) 9:e023401. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023401

89. Salcedo-Rocha AL, de Alba-García JEG, Frayre-Torres MJ, and López-Coutino B. Gender and metabolic control of type 2 diabetes among primary care patients. Rev Méd del Inst Mexicano del Seguro Soc. (2008) 46:73–81.

90. Seidel-Jacobs E, Ptushkina V, Strassburger K, Icks A, Kuss O, Burkart V, et al. Socio-economic inequalities in glycaemic control in recently diagnosed adults with type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Diabetic Med. (2022) 39:e14833.

91. Al-ma'aitah OH, Demant D, Jakimowicz S, and Perry L. Glycaemic control and its associated factors in patients with type 2 diabetes in the Middle East and North Africa: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. J Adv Nurs. (2022) 78:2257–76. doi: 10.1111/jan.15255

92. Kahn SE, Hull RL, and Utzschneider KM. Mechanisms linking obesity to insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Nature. (2006) 444:840–46. doi: 10.1038/nature05482

93. Wellen KE and Hotamisligil GS. Inflammation, stress, and diabetes. J Clin Invest. (2005) 115:1111–19. doi: 10.1172/JCI25102

94. Guilherme A, Virbasius JV, Puri V, and Czech MP. Adipocyte dysfunctions linking obesity to insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. (2008) 9:367–77. doi: 10.1038/nrm2391

95. Ahmed B, Sultana R, and Greene MW. Adipose tissue and insulin resistance in obese. Biomed Pharmacother. (2021) 137:111315. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2021.111315

96. American Diabetes Association. Standards of Medical care in diabetes - 2019. Diabetes Care. (2019) 42:S1–193.

97. Cerf ME. Beta cell dysfunction and insulin resistance. Front Endocrinol. (2013) 4:37. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2013.00037

98. Stratton IM, Adler AI, Neil HAW, Matthews DR, Manley SE, Cull CA, et al. Association of glycaemia with macrovascular and microvascular complications of type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 35): prospective observational study. bmj. (2000) 321:405–12. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7258.405

99. Nnakenyi ID, Nnakenyi EF, Parker EJ, Uchendu NO, Anaduaka EG, Ezeanyika LU, et al. Relationship between glycaemic control and lipid profile in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients in a low-resource setting. Pan Afr Med J. (2022) 41. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2022.41.281.33802

100. Hladik W, Stupp P, McCracken SD, Justman J, Ndongmo C, Shang J, et al. The epidemiology of HIV population viral load in twelve sub-Saharan African countries. PloS One. (2023) 18:e0275560. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0275560

101. Petersen M, Balzer L, Kwarsiima D, Sang N, Chamie G, Ayieko J, et al. Association of implementation of a universal testing and treatment intervention with HIV diagnosis, receipt of antiretroviral therapy, and viral suppression in East Africa. Jama. (2017) 317:2196–206. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.5705

102. Nachega JB, Sam-Agudu NA, Mofenson LM, Schechter M, and Mellors JW. Achieving viral suppression in 90% of people living with human immunodeficiency virus on antiretroviral therapy in low-and middle-income countries: progress, challenges, and opportunities. Clin Infect Dis. (2018) 66:1487–91. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy008

103. Goldstein D, Salvatore M, Ferris R, Phelps BR, and Minior T. Integrating global HIV services with primary health care: a key step in sustainable HIV epidemic control. Lancet Global Health. (2023) 11:e1120–e24. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(23)00156-0

Keywords: systematic review, meta-analysis, prevalence, factors, glycaemic control, type 2 diabetes mellitus, low- and middle-income countries

Citation: Siddiquea BN, Magliano DJ, Chowdhury HA, Chowdhury MRK, Afroz A, Shah SS and Billah B (2025) Glycaemic control and its related factors among people with type 2 diabetes in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Clin. Diabetes Healthc. 6:1695235. doi: 10.3389/fcdhc.2025.1695235

Received: 09 September 2025; Accepted: 10 November 2025; Revised: 28 October 2025;

Published: 27 November 2025.

Edited by:

Nikos Pantazis, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, GreeceReviewed by:

Hala Elmajnoun, De Montfort University, United KingdomRoghayeh Molani-Gol, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Iran

Copyright © 2025 Siddiquea, Magliano, Chowdhury, Chowdhury, Afroz, Shah and Billah. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Bodrun Naher Siddiquea, Ym9kcnVuLnNpZGRpcXVlYTFAbW9uYXNoLmVkdQ==

†Present address: Mohammad Rocky Khan Chowdhury, Department of Population Science, Jatiya Kabi Kazi Nazrul Islam University, Mymensingh, Bangladesh

Bodrun Naher Siddiquea

Bodrun Naher Siddiquea Dianna J. Magliano3,4

Dianna J. Magliano3,4 Hasina Akhter Chowdhury

Hasina Akhter Chowdhury Mohammad Rocky Khan Chowdhury

Mohammad Rocky Khan Chowdhury Afsana Afroz

Afsana Afroz Baki Billah

Baki Billah