- Faculty of Education, School of Early Childhood Education, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, Greece

Introduction: This study investigates the efficacy of Video‑Stimulated Recall Interviews (VSRI) in enhancing multimodal awareness among adolescent emergent multilinguals in non‑formal educational settings for migrant and refugee children.

Methods: Through task‑based interventions and subsequent video analysis, our research elucidates how participants employ diverse communicative modalities—including verbal expression, gesture, and visual cues—to negotiate meaning in contexts where shared language resources are limited.

Results: Our findings reveal that VSRI sessions facilitate the identification and orchestration of multiple semiotic resources while fostering reflective insight, defined as the capacity to critically evaluate and adapt one’s own communicative practices. Analyses of classroom interactions demonstrate that learners effectively coordinate gestures and visual aids to overcome linguistic barriers, thereby empowering them as active agents and meaning‑makers.

Discussion: These results underscore the transformative potential of reflective video methodologies in enhancing multimodal communication skills, with significant implications for educational practice and the social integration of emergent multilingual learners. By aligning with Frontiers in Communication’s specialty on Multimodality of Communication, this study offers novel insights into theoretical frameworks and practical strategies for supporting diverse linguistic communities in educational contexts.

1 Introduction

Since 2015, the significant influx of adolescent refugees and asylum seekers to Europe has underscored the pervasive nature of human mobility across the global landscape. Many young refugees now encounter an ever-changing environment that exposes them to diverse languages and cultures, navigating a complex tapestry of diversity and societal constructs. During these transitions, a critical issue emerges regarding the acquisition and negotiation of communicative practices among emergent multilinguals that underpin their integration into new social environments.

In the broader context of multimodal communication, individuals draw on a range of communicative modes that include language variations, speech patterns, and idiosyncratic communicative components reflecting their life trajectories. According to Wei (2018), human interactions embody multimodal communication. As a result, every interaction becomes “multimodal, “as it involves the fusion of different communicative elements (Rymes, 2014). Bateman and Schmidt-Borcherding (2018) highlight the increasing complexity of multimodal interactions, emphasizing the need for a comprehensive view of multimodal communication. This broad perspective is essential for enabling learners to effectively navigate different forms of media, while simultaneously adapting to the dynamics of communication. Modes of communication encompass a range of multimodal sets of resources available to individuals for communication within a given culture (Bainbridge and Malicky, 2000). Modes function in synergy within an individual’s communicative repertoire, shaping their interactions across different social spheres (Norris, 2004). By using various modes of communication, such as spoken language, posture, gesture, and proxemic behavior in different configurations (Norris, 2004; Denizci and Azaoui, 2020), people assemble and construct their diverse communicative repertoires. The term “communicative repertoire” encompasses the full range of linguistic and embodied modalities that individuals employ to effectively engage in different social contexts (Rymes, 2010). Viewing interactions through a repertoire-oriented lens acknowledges the intricate interplay between modes of communication and provides a framework for navigating the complexities inherent in diverse communicative encounters (Rymes, 2014). Building upon this comprehensive view, it is essential to recognize that these diverse modes do not operate in isolation but interact dynamically to co-construct meaning, as later explored by Cappellini and Azaoui (2017).

In environments where shared linguistic resources are limited, the interplay between different languages and modes adds complexity and fosters unique and diverse forms of expression. This is particularly evident in multilingual learning environments where individuals are constantly negotiating linguistic and cultural boundaries, further emphasizing the significance of exploring this dynamic interaction. Learning is a complex interplay of emotional and cognitive processes, where affective states influence how individuals perceive and process information (Dylman and Bjärtå, 2018). In a multimodal learning environment, students actively engage with instructors and peers, interacting through different modes of communication and environments. This concept of multimodality encompasses different aspects of interaction, including visual, auditory, and tactile modalities that shape the learning experience. Understanding these multimodal interactions is crucial as they influence the ways knowledge is acquired and applied, thus, highlighting the dynamic nature of learning processes in educational settings (Guo, 2023).

Transnational and translingual learners employ their multilingual, multimodal and multisemiotic repertoires, as resources in language learning (Wei and Ho, 2018) to overcome numerous communicative barriers (Zhu and Gu, 2022). Liang (2021) noted that by conceptualizing and operationalizing mediation (i.e., the process by which communicative resources are employed to bridge and negotiate meaning across different modes and languages) in broader translingual and multimodal contexts, researchers can describe and explain multilingual students’ practices across languages and modalities. Thus, multimodality conceptually enables the exploration of multiple perspectives, different narratives, and translations, fostering a dynamic process that allows multilingual learners to harness their engagement in social interaction using all their available communicative repertoires.

Kusters et al. (2017) highlight that in most studies exploring multimodality, the focus of the research is on participants using a single-named spoken language within a broader context of embodied human action. As a result, while they attend to multimodal communication, they often ignore multilingual communication. On the other hand, in most translanguaging studies, scholars focus predominantly on multilingual communication, failing to equally address aspects related to multimodality, simultaneity, and the hierarchies inherent in the combination of different resources (Kusters et al., 2017). Currently, there is little overlap between these research fields. The limited research on multimodality within superdiverse contexts hinders the understanding of how individuals, with limited shared linguistic resources, communicate, interact, and make meaning (Adami, 2023). At the same time, this limitation delays the validation of theoretical, methodological, and analytical frameworks of multimodality within a rapidly changing social landscape.

A review of the literature on multimodal communication among young emergent multilinguals, especially in multilingual contexts, reveals a lack of studies that examine the ability of emergent multilinguals to use diverse communicative repertoires for effective meaning-making and communication (Wilmes et al., 2018). Recent research on multimodal communication practices in multilingual settings is oriented toward the fields of science education, sociodramatic play (Bengochea et al., 2017), and language acquisition (e.g., Wilmes and Siry, 2021; Siry and Gorges, 2019; Williams et al., 2019; Wilmes et al., 2018; Sembiante et al., 2020). Given that there is limited research data on the micro-level of discourse according to Escobar-Alméciga and Brutt-Griffler (2022), the present study aimed to examine the potential of reflective discussions on videotaped classroom snapshots in providing insight into the semiotic modes employed by emergent multilingual adolescents in communication and meaning-making. Detailed analyses of teaching and learning interactions highlight how knowledge can be distributed across a multitude of physical, digital, cultural, and social resources (Walkington et al., 2024). According to Norris (2004), social actors’ levels of awareness and different uses of multimodal resources (e.g., language, gesture, posture, and eye gaze) for performing situated identities can be observed and analyzed in a network of communicative practices (i.e., interconnected and dynamic assemblages of communicative actions that collectively form complex interaction patterns) (Geenen, 2023).

To address these intricate dynamics and to systematically investigate the orchestration of semiotic repertoires, a robust methodological framework was developed, integrating reflective video-based techniques to capture and analyze these multimodal interactions. After carefully reviewing and comparing various reflective methodologies, including essays, blogs, and audio-based approaches, we concluded that a reflective video-based approach better met the study’s objectives by providing more direct insight into participants’ cognitive and communicative processes. This methodological choice is particularly relevant for exploring language learners’ multimodal communication, as it enables an in-depth examination of their semiotic choices in simulated pedagogic scenarios.

Furthermore, literature on informal learning among refugee adolescents, although still emerging, suggests that non-formal educational settings play a crucial role in addressing their unique learning needs and contextualizing their communicative practices.

Building on the theoretical background outlined above, this research addresses the identified needs and gaps in literature by integrating insights from multimodal communication, language acquisition, and informal learning. Specifically, we develop a comprehensive framework for understanding how emergent multilingual refugee adolescents navigate complex communicative challenges.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

This research draws upon a comprehensive array of data sources to facilitate an in-depth exploration of the spectrum of emergent multilinguals’ communicative repertoires used for communication, participation, and meaning-making. Initially, field notes were used for systematic observation of their interactions during their courses. Consequently, data collection incorporated task-based interventions and learning artifacts produced during the implementation. Finally, to introduce VSRIs, a camera, a tablet, and a smartphone were utilized to capture close-up videos of participants’ interactions. Ultimately, data sources for this study included video recordings of participant interactions, transcribed dialogues from VSRI sessions, and reflective insights garnered from participant reflections. The video recordings provided a rich and multifaceted view of the participants’ communicative exchanges, capturing verbal and embodied aspects of their interactions. Transcribed dialogues from VSRI sessions served as a textual representation of participants’ reflections, offering valuable insights into their cognitive processes and semiotic choices (Gass and Mackey, 2016). The combination of these data sources, encompassing video recordings, field notes, transcribed dialogues, and reflective insights, formed the basis for the analysis. Through the use of diverse data sources, this research aimed to uncover the intricacies of emergent multilingual communication within the context of non-formal education, shedding light on the participants’ communicative repertoires and strategies used in/for communication.

2.2 Methods

Following the task-based interventions, participants were stratified into two groups—Beginners and Advanced—based on their proficiency in Greek, the host language, with home languages including Albanian, Dari, Farsi, Somali, and Ukrainian. In view of the ethical considerations inherent in research with minors, informed consent was obtained from both participants and their guardians using translated forms in strict accordance with established ethical guidelines (e.g., Kilburn et al., 2014). Moreover, before each session, the study’s aims and procedures were clearly communicated to ensure ethical compliance and to minimize any potential distress.

2.2.1 Data analysis

A multi-level analytical approach was employed. In the first level, researchers reviewed video material from Phase B to identify instances of non-communication-moments characterized by high modal density. For clarity, “modal density” is defined as the intensity and complexity of the various modes of communication employed simultaneously during an interaction (Norris, 2004). For example, in Extract 1, the coordinated use of gestures to represent a “café” exemplified high modal density, as multiple communicative modes were engaged concurrently to convey meaning.

The second level focused on designing the VSRI protocol to encourage reflective processes. Here, participants were asked to review video excerpts and articulate their cognitive and emotional responses. Structured questions, informed by the identified critical communicative instances, guided this elicitation process (Gass and Mackey, 2016).

In the third level, transcriptions from VSRI sessions were analyzed in depth to examine how participants navigated communication within their multilingual groups. Special attention was paid to how participants integrated multiple semiotic resources in their reflective accounts.

3 Results

Three communicative episodes are presented below to illustrate how a group of emergent multilingual adolescents employed their available linguistic resources for communication and to demonstrate their growing awareness regarding the effectiveness of their communication strategies. We also show how they slowly gained empowerment through reflection on their communication choices. In the first episode, the participants attempt to explain the word “Cafe” /kafe/ without relying on language. In the second one, they try to communicate the meaning of the word “souvlaki”/suvlaki/ (a kind of sandwich in Greek), and in the third episode, they reflect on the modes of communication used as they were trying to find alternative ways to convey meaning.

The participants in the following episodes have one of the following languages as their mother tongue: Arabic, Persian, Albanian, Somali, and French and they all belong to the beginners’ group. Some of the students have a certain level of familiarity with the Greek language, some have sporadically attended Greek classes in the past and others have no familiarity with the Greek language at all.

Similarly, their proficiency levels in English vary, while most of them have some basic knowledge. Therefore, English was chosen as the language of instruction to better serve the purposes of the VSRIs. The participants’ responses were transcribed exactly as they were said by the participants themselves and where there are errors in the English language, it is precisely because the researchers are quoting the data exactly as they were said by the participants themselves.

EXTRACT 1 A multilingual “Café”

Three students, identified as N, B and R, attempt to explain the word ‘café’ to their classmate identified as L. The researcher initiated the session by saying:

01. Researcher: And what do you tell her? You tell her… (0.2)

02. N: She writes… “Café”, yes. (0.2)

03. Researcher: And then L comes ((gaze shift to L)). She told you to make a “Café”. And what did you understand, do you remember? (0.4)

04. L: I thought it was the color brown. (0.4) {“café” sounds the same as the Greek word «καφέ» (kafe) for the brown color}.

05. Researcher: Well-done, you thought it was the color brown. What did B do? She's showing you it's a … (0.9)

06. V: ((gestures indicating 'house'))

07. L: A place… where we drink coffee. (0.2)

08. Researcher: What did N do? (0.9)

09. N: I said “Café” ((gesture indicating drinking coffee)) (0.5)

10. Researcher: And she explained she's drinking “Café”. You understood the color brown, B came and showed you with her hands that it's a coffee house, and what did N do? She made the gesture of drinking coffee to help you, right? So, did they finally explain to you what they wanted? Did they manage to explain it to you?

11. L: Yes. (0.2)

12. Researcher: Even though they don't speak either Greek or Albanian… (0.1)

13. L: Yes. (0.1)

14. Researcher: And you understood what you had to do… (0.2)

15. L: Yes, I understood afterward. (0.2)

3.1 Analysis

The participants observe a task-based intervention in which they attempt to explain to a participant, L, that they want her to draw a coffee house on the collectively constructed map (Figure 1).

The dialogue unfolds as they observe the participants’ reactions and interactions. Participant L initially misinterprets the meaning of the word “Café” as the color brown (sounding identically in Greek), demonstrating a cognitive link between the word and its visual connotation. The other participants, recognizing her misinterpretation, use hand gestures to explain the intended message (Figure 2).

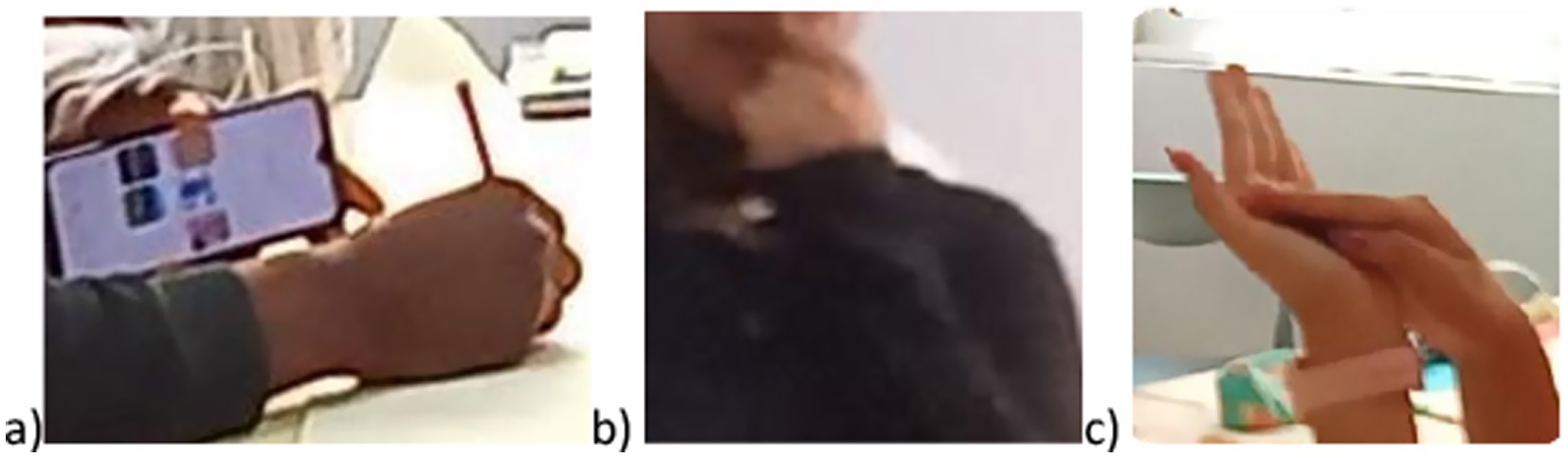

Figure 2. Snapshots of participants’ gestures. (a) deictic pointing gesture; (b) “glass” iconic gesture; (c) “building” shaping gesture; (d) sipping gesture.

Frames a to d show the participants producing a variety of hand gestures in their attempt to convey the meaning of the word ‘Café’. Frame a illustrates the stroke phase of a deictic gesture produced by Participant L in turn 4. Participant L attempts to confirm her interpretation of the meaning by using an object, such as a brown marker, to clarify whether she is being asked to draw with the color brown. Frames b to d present sequences of iconic gestures that participants V and N use to convey the visual content of the word “Café” as a place for coffee consumption. These frames include imitating the glass in which coffee is served (frame b), using the hands to create an imaginary shape of a ‘building’ in which coffee is served (frame c), and representing the act of drinking (frame d). Through these hand gestures, the participants attempt to give form and shape to what is challenging to communicate verbally, trying to represent the meaning in the movement and space of their gestures, thus serving as an additional mode of communication.

3.2 Comments

The dialogue shows how the participants, reflecting on their previous interactions, strategically use different modes to explain the meaning of “Café” to participant L, given her lack of understanding of the English word. They see themselves strategically coordinating gestures, expressions, and interactive exchanges, to navigate the task, confirming their successful multimodal communication strategies. This highlights their awareness of using complementary communication practices to convey meaning, regardless of language barriers. Participants acknowledge their multimodal engagement in specific instances, recognizing that multimodal communication is a versatile means of experimenting with different ways of conveying messages. Participant L’s statement, “Yes, I understand it afterward,” underlines the realization of the effectiveness of multimodal communication in achieving mutual understanding.

EXTRACT 2 A different kind of “souvlaki”

In the second episode, the participants endeavored to convey the meaning of the word “souvlaki.” The exchange involves four students - F, Y, D, and H. (The inclusion of H clarifies the group composition.)

0.1. Researcher: What were you trying to do?

0.2. F: I am trying to explain Y about souvlaki. I know what this is. I want to tell him about the souvlaki.

0.3. Researcher: Nice. What about you Y? Was it difficult to understand what souvlaki is?

0.4. F: For him to explain is difficult.

0.5. Researcher: Yes but, what have you done? He did not know what souvlaki is, but what have you done to make him understand what souvlaki is? What have you done? Let us see… (continues the video).

0.6. Researcher: Now look how H is going to explain to him what souvlaki is. Listen to what she said!

0.7. F: I stay like this because I know H no speak English.

0.8. Researcher: But what did she say?

0.9. Y: When she speaks Arabic me no understand, when I speak Mali she does not understand.

10. Researcher: But did you listen to her? She said that souvlaki is a sandwich! She just said that!

11. F: Arabic.

12. D: Yes, Arabic!

13. F: Speak English no Arabic.

14. Researcher: She told Y that souvlaki is a sandwich!

15. D: Sandwich.

16. Researcher: He still did not understand. And now look at what A is going to do… (continues the video).

17. A: Yes, I showed him a picture (gesture indicating that he was holding a phone and displaying an image of souvlaki).

18. Researcher: What about H? She acts like she is eating. She said “Food” (plus a gesture to indicate eating) you see. She is making the gesture, ok? She’s trying to show you that souvlaki is a food. So, Y… You did not understand the word “souvlaki,” but there were three ways they tried to explain to you. They told you that souvlaki is a sandwich. Then A came with a picture. And then, H made that gesture (indicating eating). And did Y finally understand?

19. Y: I understand a little bit, but I understand.

3.3 Analysis

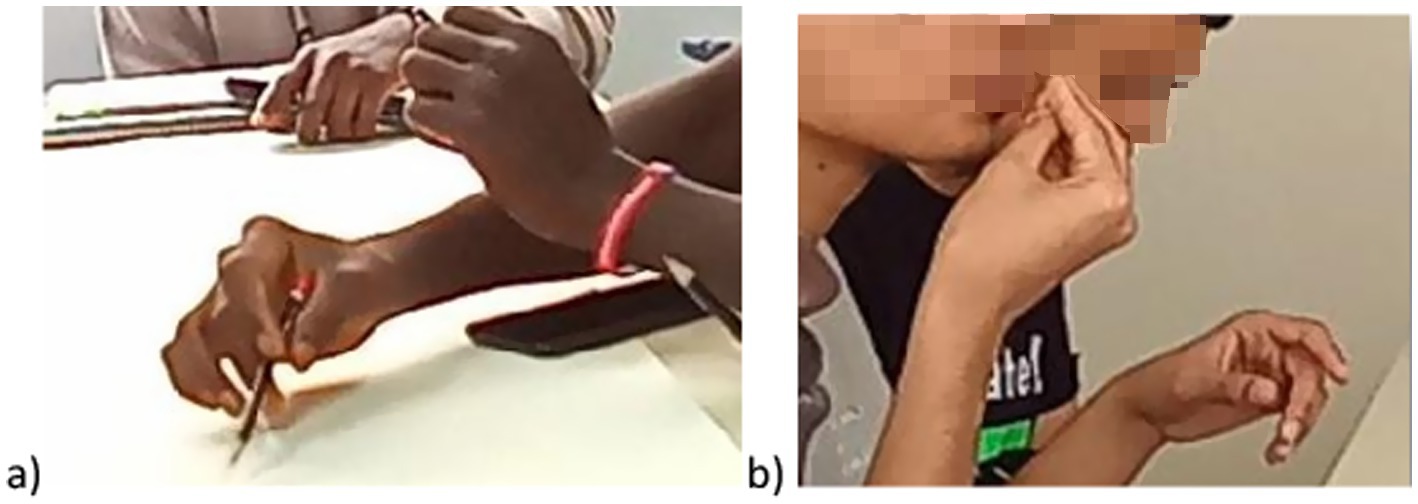

In response to the researcher’s question “What were you trying to do,” participant F points to the challenge of explaining the meaning of the word “souvlaki” to participant Y “For him to explain is difficult” (line 04). The researcher encourages the participants to reflect on the challenges and the practices used to facilitate understanding. Participant Y highlights the challenge regarding the lack of shared language resources, referring to participant H’s attempt to communicate in Arabic “When she speaks Arabic, me no understand, when I speak Mali she does not understand” (line 09). Participant H uses the word “sandwich” to explain to participant Y what souvlaki is, but Y does not seem to understand the English word. The researcher then asks the participants to observe themselves in the video interaction to detect what other ways they used to communicate the intended message. Participant A commented on his choice to show participant Y a picture of souvlaki to help him understand “I saw him a picture (gesture indicating that he was holding the phone and showing the picture of souvlaki that he found) (line 17) (Figure 3).”

Figure 3. Snapshots of participants’ gestures. (a) picture-showing gesture; (b) eating gesture; (c) verbal “sandwich” explanation.

Participant H chose a combination of a verbal explanation “food” and a gesture indicating eating. Despite initial challenges, through these assemblages of embodied actions employed by the participants, participant Y acknowledges understanding “I understand a little bit, but I understand,” illustrating the effectiveness of the use of alternative modes employed during the interaction.

3.4 Comments

The dialogue offers insight into the embodied and multimodal engagement of the participants in overcoming communication challenges and achieving understanding. Reflecting on their communicative practices, participants identify the resources they used to explain the meaning of the word souvlaki. Failing to achieve the communicative goal through language, participants cooperatively use additional modes, such as gestures and visual means, to achieve shared meaning. The video contributed significantly to this temporally unfolding process of awareness by providing a richer view of the communicative, interactive resources employed by the participants. This growing awareness empowers participants as meaning-makers as they observe that successful instances of communication result from the orchestration of different communication modalities.

EXTRACT 3 Finding different ways to explain myself

The final episode features a reflective discussion on communicating in the absence of shared language. A group of four male students – A, D, Y, and R- were asked to analyze a previously recorded interaction and identify the alternative modes of communication they employed.

01. Researcher: Ok. If we take language out of the context—no English, no Greek, no Mali, no Farsi—what other ways did you find to communicate? How did you manage when you did not have any common language?

0.2. A: He cannot speak like that yeah? He cannot speak… exactly.

0.3. Researcher: But what did Y do?

0.4. Y: I… (gestures indicating that he was drawing).

0.5. Researcher: You were drawing, remember?

0.6. Y: Yes.

0.7. D: He was drawing.

0.8. Researcher: So, one way is drawing. Another is?

0.9. A: Imagine like… (performs gestures to explain the concept of ‘gesture’).

10. Researcher: How did you explain it before using your hands?

11. A: Food + (gesture indicating eating) I am full… (laughter).

12. Researcher: So, if we remove language, there are other ways to communicate. Alright, thank you very much.

3.5 Analysis

Given the lack of a common language between participant Y and V, the researcher explores how they managed to communicate, asking them to reflect on the modes of communication they used during their previous interaction, which was captured on video (line 01). As the conversation progresses, participant Y responds with a gesture, suggesting that drawing has served as a means of communication for him (line 04) (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Snapshots of participants’ gestures. (a) drawing gesture; (b) “food” gesture indicating eating.

This form of non-verbal communication is acknowledged and emphasized by the researcher (line 05) and reiterated by other participants, thereby reinforcing the importance of drawing as a means of communication. (line 07). Participant A recognizes gestures as another way of communicating. He uses hand movements and demonstrates the act of eating, creating a light-hearted moment for the participants (line 11).

3.6 Comments

This dialogue explores how participants gradually become aware of how they, as intentional and agentive signifiers, meaningfully and responsively orchestrate different modes of communication to achieve their communication purposes. Specifically, they identify gestures, drawing, and demonstrating the act of eating as embodied ways of expressing intended messages. Interactants also gain awareness of their capacity to respond to the communication “demands” through their multimodal engagement with other participants and the researcher. In doing so, they increase their understanding of the affordances of the multimodal practices they have used to convey intended communicative purposes. This process deepens as the participants’ reflective process unfolds, gradually leading them to realize how actively they are involved in the co-construction of meaning.

4 Discussion

In the present study, we argued that classroom video analysis, grounded in embodied, reflective, and multimodal analytical approaches, can highlight the extended spectrum of communicative repertoires employed by emergent multilinguals for communication, active participation, and meaning-making. Data analysis elucidated three episodes of VSRIs, revealing how this analytical process could contribute to fostering awareness and reflective engagement in navigating communication within a multifaceted and dynamic social context.

By reflecting on specific communication instances observed in the videos, participants acknowledged that they achieved communication through the use of a variety of embodied modes such as gestures, facial expressions, body movements, and gaze, and disembodied modes, such as drawing. Azaoui (2015) demonstrates that nonverbal orchestration—particularly the interplay of gaze and hand gestures—offers critical insights into how participants overcome communicative barriers, a finding that is mirrored in our study’s observations of multimodal interactions. Through these reflective sessions, participants not only improved their communicative strategies but also showed subtle shifts in their self-perception as effective communicators. Participants acknowledged that the increased clarity of their communicative practices was recognized by both peers and researchers.

The results of this study are consistent with those of recent research on the significance of reflective practice in educational settings (Kilburn et al., 2014; Endacott, 2016; Gazdag et al., 2019). Reflection through interaction with others cultivates the sharing and integration of different experiences and ideas, promotes broader understanding, and provides the basis for reinterpreting and developing one’s own perspectives (Allas et al., 2016). Given recent academic research highlighting the central role of peer interaction in reflective practice, particularly in facilitating the exchange of ideas and enhancing communication (Petsilas et al., 2020; Chan and Wong, 2021), our research sought to explore this phenomenon further. In our study, participants identified their multimodal engagement within video-recorded interactions, unraveling the ensembles of multimodal resources used, and reflected on their thoughts and feelings.

The methodological choice of VSRI helped the participants to become aware of how they orchestrate their semiotic repertoires to make themselves more comprehensive to their interlocutors. Data analysis revealed a remarkable correlation between moments of non-understanding and high modal density –i.e., the intensity or complexity of modes engaged simultaneously. For instance, in Extract 1, the coordinated use of gestures to represent a “café” exemplified high modal density, as multiple communicative modes were engaged concurrently to convey meaning. According to Norris (2004), modal density allows both participants and analysts to perceive the weight placed on a particular action by the individual. Thus, as participants attempted to overcome the lack of common language resources, their interactions were characterized by high modal complexity through a variety of intricately intertwined modes of communication to facilitate their communication intentions. In reflecting on these instances, the participants were encouraged to take an introspective look at how they used different modes to achieve communication. VSRI makes their choices more visible, increases their self-awareness and thus strengthens their role as agents. As a result, this process has contributed to their increased awareness that communication is not limited to language. Participants used a variety of representational modes and highlighted their active role to orchestrate their available resources for meaning-making.

The flexible protocol facilitated the processing of findings by adapting to the dynamic nature of the multilingual non-formal education environment. This adaptability allowed for invaluable adjustments during sessions, given the fluid conditions of such settings. Additionally, the reflective features of the VSR methodology, along with its flexibility (Martinelle, 2020), proved to be a valuable methodological choice, contributing significantly to the results obtained. Through these affordances, participants gained a deeper understanding of their experiences, became aware of their multimodal repertoires, and were thus empowered as agents and meaning-makers within the learning context.

In their research, Cappellini and Azaoui (2017) demonstrated that the affordances of the desktop videoconference (DVC) environment support a wide range of modes to achieve mutual understanding and co-construct meaning locally, especially when communicative barriers arise. This is consistent with our findings where, despite language barriers, participants commented on specific instances of high modal density and observed themselves interacting effectively. They reported an increased understanding of intended messages, even without shared language resources, indicating their ability to overcome communicative challenges through diverse multimodal choices. Reflecting on the video interactions, participants acknowledged successful instances of communication through different modes, emphasizing their role in facilitating mutual understanding and, thus, increasing their awareness of their multimodal communication skills. Furthermore, Cappellini and Azaoui (2017) suggested that additional sources of data, such as participants’ comments or stimulated recall, could deepen the understanding of multimodal interactions. In our study, which employs video-stimulated recall methodology, participants reflected on video interactions and acknowledged successful communication through different modes, highlighting their role in facilitating mutual understanding.

This reflective process enhanced their awareness of their multimodal communication skills, supporting Azaoui’s assertion that the modes and modalities of the DVC environment can become affordances for language learning and teaching.”

It was acknowledged that multimodal communication is not only a fundamental aspect of connecting across cultural and linguistic boundaries but also that it plays a role in sharing information and explaining thoughts in a multilingual and multicultural context. Despite the limitations in formulating detailed VSRI questions and the time constraints affecting thorough multimodal analysis, participants became aware that embracing different modes of communication enriches their multimodal repertoires and acts as a driving force for their empowerment as active agents and meaning-makers in their communicative endeavors. This awareness promotes their communicative empowerment and enables them to navigate and improve their communicative practices in multilingual interactions.

Exploring participants’ learning as design, as described by Adami et al. (2022), reveals profound implications for educational practice. Understanding learners’ use of available resources to make meaningful connections highlights the transformative potential of this approach. Following Gunther Kress’s perspective, the concept of learning as design emphasizes that students, as meaning makers, act as agents in selecting and utilizing various semiotic resources to purposefully construct meaning. By situating students as active designers of meaning, this perspective highlights the importance of choice, influenced by the range of resources available and driven by individual interests. Within VSRI sessions, participants immerse themselves in the learning process, become active contributors, and act collectively as designers of meaning. As such, they actively shape social interactions through communication, illustrating the transformative impact of their engagement in the reflective sessions. As highlighted by Kress and Selander (2012), this collaborative process involves the orchestration of embodied semiotic resources and the active shaping of social interactions through communication. For example, the dynamic manipulation of gestures and visual aids in Extracts 1 and 2 underscores this design process in action. This perspective positions learners as active agents who purposefully construct meaning by integrating various resources—a finding with profound implications for pedagogical practice. Such a learning-as-design approach enriches pedagogical practices and fosters an inclusive, empowering educational environment. This collaborative endeavor underlines profound implications for pedagogy, highlighting the transformative potential of adopting a learning-as-design perspective, enriching pedagogical practices, and fostering a more inclusive and empowering educational environment.”

Within the diverse social backgrounds of students, the use of this methodology not only increases students’ awareness of their multimodal representations but also enables them to reconfigure existing resources to suit their unique meaning-making needs. The core principle of Kress (2010) design perspective comes to the fore when communication is seen as a transformative process, where participants are actively engaged as influential agents and are seen as designers of meaning, as both are involved in shaping social interaction between them through communication (Kress and Selander, 2012).

In conclusion, the present study highlights the efficacy of classroom video analysis in revealing the diverse communicative repertoires employed by emergent multilinguals, illuminating their ability to communicate multimodally beyond language barriers. Through an embodied, reflective, and multimodal analytical approach, the participants gained awareness of their communicative abilities, recognized their role as active agents in communication regardless of linguistic constraints, and, were thus empowered as active agents in their learning journey.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Ethics committee of Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin. Written informed consent was not obtained from the minor(s)’ legal guardian/next of kin, for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article because consent was obtained from both the minors and their legal guardians to participate in the study, with the understanding that publication of personal information would require explicit consent from the minors when they reached the age of majority. Despite the lack of written consent for publication, the utmost care was taken to maintain the confidentiality and anonymity of participants throughout the study and dissemination of results.

Author contributions

MT: Conceptualization, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MP: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adami, E. (2023). Multimodality and the issue of culture. Multim. Commun. Intercult. Interact. 17–40. doi: 10.4324/9781003227281-3

Adami, E., Diamantopoulou, S., and Lim, F. V. (2022). Design in Gunther Kress’s social semiotics. Lond. Rev. Educ. 20. doi: 10.14324/lre.20.1.41

Allas, R., Leijen, Ä., and Toom, A. (2016). Supporting the construction of teacher’s practical knowledge through different interactive formats of oral reflection and written reflection. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 61, 600–615. doi: 10.1080/00313831.2016.1172504

Azaoui, B. (2015). Polyfocal classroom interactions and teaching gestures. An analysis of nonverbal orchestration. Gesture and speech in interaction (GESPIN), Sep 2015 (France: Nantes Press). Available at: https://hal.science/hal-01228911v1

Bainbridge, J., and Malicky, G. (2000). Constructing meaning: balancing elementary language arts. New York, NY: Harcourt Canada.

Bateman, J. A., and Schmidt-Borcherding, F. (2018). The communicative effectiveness of education videos: Towards an empirically-motivated multimodal account. Multim. Technol. Interact. 2:59. doi: 10.3390/mti2030059

Bengochea, A., Sembiante, S. F., and Gort, M. (2017). An emergent bilingual child’s multimodal choices in sociodramatic play. J. Early Child. Lit. 18, 38–70. doi: 10.1177/1468798417739081

Cappellini, M., and Azaoui, B. (2017). Sequences of normative evaluation in two telecollaboration projects: a comparative study of multimodal feedback through desktop videoconference. Lang. Learn. Higher Educ. 7, 55–80. doi: 10.1515/cercles-2017-0002

Chan, C. K., and Wong, H. Y. (2021). Students’ perception of written, audio, video and face-to-face reflective approaches for holistic competency development. Act. Learn. High. Educ. 24, 239–256. doi: 10.1177/14697874211054449

Denizci, C., and Azaoui, B. (2020). Analyzing interactive dimension of teacher gestures in naturalistic instructional contexts. TIPA 36. doi: 10.4000/tipa.3843

Dylman, A. S., and Bjärtå, A. (2018). When your heart is in your mouth: the effect of second language use on negative emotions. Cognit. Emot. 33, 1284–1290. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2018.1540403

Endacott, J. L. (2016). Using video-stimulated recall to enhance preservice-teacher reflection. New Educ. 12, 28–47. doi: 10.1080/1547688x.2015.1113351

Escobar-Alméciga, W. Y., and Brutt-Griffler, J. (2022). Multimodal communication in an early childhood bilingual education setting: a social semiotic interactional analysis. Íkala 27, 84–104. doi: 10.17533/udea.ikala.v27n1a05

Gass, S. M., and Mackey, A. (2016). Stimulated recall methodology in applied linguistics and L2 research. 2nd Edn. London: Routledge.

Gazdag, E., Nagy, K., and Szivák, J. (2019). I spy with my little eyes… The use of video stimulated recall methodology in teacher training – the exploration of aims, goals and methodological characteristics of VSR methodology through systematic literature review. Int. J. Educ. Res. 95, 60–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ijer.2019.02.015

Geenen, J. (2023). Introduction: multimodal (inter) action analysis. Multim. Commun. 12, 1–6. doi: 10.1515/mc-2023-0010

Guo, X. (2023). Multimodality in language education: implications of a multimodal affective perspective in foreign language teaching. Front. Psychol. 14:1283625. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1283625

Kilburn, D., Nind, M., and Wiles, R. (2014). Learning as researchers and teachers: the development of a pedagogical culture for social science research methods. Br. J. Educ. Stud. 62, 191–207. doi: 10.1080/00071005.2014.918576

Kress, G. (2010). Multimodality: a social semiotic approach to contemporary communication. London: Routledge.

Kress, G., and Selander, S. (2012). Multimodal design, learning and cultures of recognition. Internet High. Educ. 15, 265–268. doi: 10.1016/j.iheduc.2011.12.003

Kusters, A., Spotti, M., Swanwick, R., and Tapio, E. (2017). Beyond languages, beyond modalities: transforming the study of semiotic repertoires. Int. J. Multiling. 14, 219–232. doi: 10.1080/14790718.2017.1321651

Liang, M. Y. (2021). Multilingual and multimodal mediation in online intercultural conversations: a translingual perspective. Lang. Aware. 30, 276–296. doi: 10.1080/09658416.2021.1941069

Martinelle, R. (2020). Using video-stimulated recall to understand the reflections of ambitious social studies teachers. J. Soc. Stud. Res. 44, 307–322. doi: 10.1016/j.jssr.2020.03.001

Petsilas, P., Leigh, J., Brown, N., and Blackburn, C. (2020). Creative and embodied methods to teach reflections and support students’ learning. Dance Prof. Pract. Workplace, 47–66. doi: 10.4324/9780367822071-4

Rymes, B. (2010). Why and why not? Narrative approaches in the social sciences. Narrat. Inq. 20, 371–374. doi: 10.1075/ni.20.2.07rym

Rymes, B. (2014). “The Routledge companion to English studies” in New York. eds. C. Leung and B. V. C. Street (NY: Routledge).

Sembiante, S. F., Bengochea, A., and Gort, M. (2020). Want me to show you?: Emergent bilingual preschoolers’ multimodal resourcing in show-and-tell activity. Linguist. Educ. 55:100794. doi: 10.1016/j.linged.2019.100794

Siry, C., and Gorges, A. (2019). Young students’ diverse resources for meaning making in science: learning from multilingual contexts. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 42, 2364–2386. doi: 10.1080/09500693.2019.1625495

Walkington, C., Nathan, M. J., Huang, W., Hunnicutt, J., and Washington, J. (2024). Multimodal analysis of interaction data from embodied education technologies. Educational technology research and development, 72, 2565–2584. doi: 10.1007/s11423-023-10254-9

Wei, L. (2018). Translanguaging as a practical theory of language. Appl. Linguis. 39:261. doi: 10.1093/applin/amx044

Wei, L., and Ho, W. Y. J. (2018). Language learning sans frontiers: a translanguaging view. Annu. Rev. Appl. Linguist. 38, 33–59. doi: 10.1017/S0267190518000053

Williams, M., Tang, K. S., and Won, M. (2019).ELL’s science meaning making in multimodal inquiry: A case‑study in a HongKong bilingual school. Asia‑Pacific Science Education, 5, 1–35. doi: 10.1186/s41029-019-0031-1

Wilmes, S. E., Fernández, R. G., Gorges, A., and Siry, C. (2018). Underscoring the value of video analysis in multilingual and multicultural classroom contexts. Video J. Educ. Pedag. 3, 1–14. doi: 10.1186/s40990-018-0016-0

Wilmes, S. E. D., and Siry, C. (2021). Multimodal interaction analysis: a powerful tool for examining plurilingual students’ engagement in science practices: proposed contribution to RISE special issue: analyzing science classroom discourse. Res. Sci. Educ. 51, 71–91. doi: 10.1007/s11165-020-09977-z

Keywords: multimodal awareness, emergent multilinguals, video-stimulated recall, non-formal education, reflection

Citation: Tsikou M and Papadopoulou M (2025) Video-stimulated recall interviews for multimodal awareness raising in communication among adolescent emergent multilinguals. Front. Commun. 10:1432271. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2025.1432271

Edited by:

Brahim Azaoui, Université de Montpellier, FranceReviewed by:

Thomas Amundrud, Nara University of Education, JapanCan Denizci, Dokuz Eylül University, Türkiye

Copyright © 2025 Tsikou and Papadopoulou. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Maria Tsikou, bW50c2lrb3VAbnVyZWQuYXV0aC5ncg==;

Maria Tsikou

Maria Tsikou Maria Papadopoulou

Maria Papadopoulou