- 1LIDS Research Group, Faculty of Education, Hamburg University, Hamburg, Germany

- 2Icare Research Group, Université de la Réunion Réunion, Saint-Denis, France

Introduction: This paper defines plurilingual assessment and shows the semantic ambiguities present in the concept. Specifically, it addresses two understandings of the concept: one related to the valuation of the plurilingual individual and the other to the evaluation of the plurilingual competence.

Methods: The above-mentioned distinction is treated theoretically only, through the revision of available and emergent literature, which serve as a springboard to present, describe, and compare two European projects dealing with plurilingual assessment in formal language education settings.

Results: The two European projects present commonalities and differences and show that the valuation of the plurilingual individual and the evaluation of the plurilingual competence can be blurred in assessment practices.

Discussion: The paper finishes with recommendations for the development of plurilingual pedagogical and assessment approaches for all students, as a way to enhance the plurilingual competence of all at school.

1 Introduction

Since the 1980s, researchers have created several models to describe the specific features of plurilingual individuals and plurilingual communication. These models show that the plurilingual competence is complex, dynamic, and may involve mixing different languages (Grosjean, 1982, 2008; Cummins, 1981, 2001, 2019; Cook, 1992, 2016; García and Wei, 2014; Coste et al., 1997; García et al., 2017; Cenoz and Gorter, 2021).

At the same time, plurilingual education, in particular the use of existing language skills to learn new languages and the development of plurilingual competences, has become a priority in language education. In Europe, these educational objectives are promoted by supranational organizations such as the European Union and the Council of Europe, which aim to preserve and promote plurilingualism among European citizens. The dissemination of the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR, Council of Europe, 2001) and its Companion Volume is an example of the political will to promote plurilingual education. In these documents, the Council of Europe declares the development of the plurilingual competence as the main objective of language education. The CEFR is complemented by various guides (e.g., Beacco et al., 2016; Beacco and Byram, 2007) and recommendations for language policy and practice (Committee of Ministers, 2014; Civil Society Platform on Multilingualism, 2011; Conseil de l’Europe, Comité des Ministres, 2022).

However, educational practices do not always match the demands of science and the political will. This is particularly true in the case of plurilingual education, as Beacco et al. (2016) stated in the preface of a guide for the development of plurilingual curricula. Very few curricula actually emphasize the importance of promoting plurilingual competence even though they officially declare their alignment with the CEFR. The European Union has also identified shortcomings in the European plurilingual policies, pointing out the “lack of multilingual competence” in the Council recommendation on a comprehensive approach to the teaching and learning of languages (Council of the European Union, 2019, p.15).

The aforementioned points regarding plurilingual education are of even greater significance in the context of plurilingual assessment. The Council of Europe published a satellite study on this topic (Lenz and Berthele, 2010) and the recent Recommendation CM/Rec (2022)1 of the Committee of Ministers to member States on the importance of plurilingual and intercultural education for democratic culture (Conseil de l’Europe, Comité des Ministres, 2022) explicitly states that “the responsible for national, regional and institutional policy in all educational sectors should […] support the creation and use of assessment instruments that are fully aligned with the goals of plurilingual and intercultural education for democratic culture.” However, even if scholars have begun to investigate this domain (Melo-Pfeifer and Ollivier, 2023a) - particularly in the context of migration, as well as within the framework of pluralistic approaches in education - plurilingual assessment remains a still under-researched and largely unimplemented area.

In light of the aforementioned situation, this paper aims at feeding the theoretical academic discussion on plurilingual assessment and opening concrete pedagogical avenues to address the challenges posed, on one hand, by the assessment of plurilingual competence and, on the other hand, by the assessment of non-linguistic competences of plurilingual individuals. In order to do so, this paper will compare two different approaches in two different projects: one assessing the plurilingual communicative competence in Romance languages, and the other focusing on the assessment of crosslinguistic mediation competences. It will allow a comparison of the approaches, and a description of some specificities of both assessment types. In doing so, it will offer a better understanding of the diversity and complexity of plurilingual assessment.

2 Theoretical underpinnings

In the introduction, we focused on the political context underlying the emergence of plurilingual assessment as a research field. In this section, two key aspects of the situation in research will be highlighted. First, we will address the discrepancy between the multilingual turn in (language) education and the persistence of the monolingual mindset and practices in assessment. Second, we will discuss the ambiguity of the concept of “plurilingual assessment.”

2.1 Discrepancy between multilingual turn and monolingual assessment practices

Similarly to the tension between the political will and the actual practices mentioned above, a discrepancy can be identified between the multilingual turn in the domain of second language acquisition (May, 2013) and the assessment practices and teachers’ beliefs, which remain strongly monolingual – and monoglossic (i.e., promoting the separation of languages). This paper aims to provide evidence for the possibility of aligning plurilingual teaching and assessment. It will analyze concrete ways of assessing plurilingual competence as a teaching and learning goal, and will show how plurilingual education can integrate plurilingual assessment practices.

The pedagogical interest in plurilingual education is a long-standing phenomenon, with evidence of its existence dating back to a considerable period in the past. In his PhD thesis, Fornel (2023) presents a comprehensive analysis of various publications from the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries that address the topic of Romance languages and promote plurilingual learning to varying degrees. A substantial number of projects and publications from the past 40 to 50 years address the topic of plurilingual education. A reference framework has even been developed by Candelier et al. (2012) for the pluralistic approaches that have been extensively investigated in recent years, including the intercultural approach (Abdallah-Pretceille, 2011; Byram, 2003; Dervin and Liddicoat, 2013), intercomprehension (Caddéo and Jamet, 2013; Escudé and Janin, 2010; Garbarino and Degache, 2017; Ollivier and Strasser, 2013), integrated didactics (Hufeisen and Lindemann, 1998; Hufeisen and Neuner, 2003), and Awakening to Languages (Candelier et al., 2003). A recent publication (Candelier et al., 2023) provides an overview of the latest developments.

Despite the fact that all of these approaches are designed to support learners in enhancing their schooling integration and developing their plurilingual competence, there has been a notable lack of interest for plurilingual assessment within the academic and pedagogic community over a considerable period of time. Indeed, while “from a social justice perspective, discrimination of multilingual practices as well as marginalization of (certain) multilingual speakers are to be contested by multilingual assessment” (Vogt and Antia, 2024, p.11), assessment tends to stay monolingual, perpetuating linguistic and cognitive injustices. This is true even in contexts where teachers implement more or less systematic practices. This means that “assessment practices that make use of more than just the target language or the full repertoire of the students to access their content knowledge” (Stathopoulou et al., 2024, p. 236) are seen with mistrust and are rarely used.

2.2 Ambiguity of the concept of plurilingual assessment

One of the challenges to mainstream plurilingual assessment (practices) might be the ambiguity of the concept itself. To start with a simple yet operative definition, Vogt and Antia, (2024, p.11) declare that “multilingual assessment can be understood as incorporating multilingual elements into assessments, whether they are content-related or language-related”. A search on academic search engines for the term “multilingual (or plurilingual) assessment” will return publications addressing the assessment of non-linguistic competences of plurilingual individuals, as well as papers and books on the assessment of plurilingual competences (for more information, see below in section 3). Both underscore that plurilingual assessment is broadly about evaluating individuals who are fluent, in various degrees, in multiple languages.

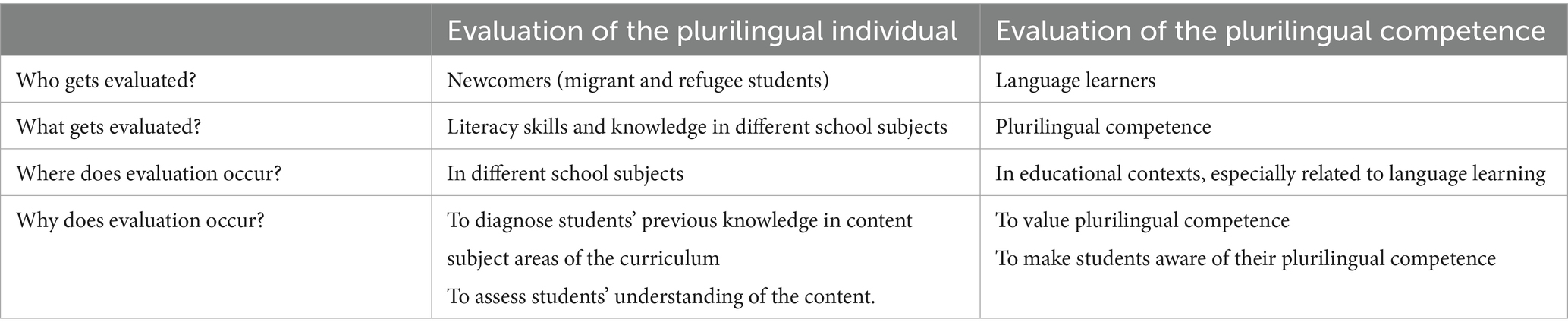

Table 1 presents some of the differences and commonalities between two main conceptual strands, in terms of: (a) characteristics of the individual, (b) the skills and competencies being evaluated, (c) the context where the evaluation occurs and, finally, (d) the purpose of the evaluation process and outcomes.

With assessment of non-linguistic competences of plurilingual individuals, we refer to the evaluation of skills or competencies such as cognitive or problem-solving abilities and subject content. Assessment of plurilingual competences is understood as the evaluation of language-related abilities, evaluating how individuals use their linguistic repertoire holistically.

This dichotomy shows that both strands share some similarities but also have distinct features, based on what and how they assess, and the borders can be blurry. Evaluation of the plurilingual individual tends to be conceived in contexts of welcoming students with a mobility history into a new educational system, to diagnose their command of or to strengthen their acquisition of school subjects’ content. This strand is concerned with issues of linguistic, social, and cognitive justice. Evaluation of the plurilingual competence is a construct developed to assess the command and use of different languages, either cumulatively or in more holistic and integrated terms. In the next section, we delve deeper into these differences.

3 Evaluation of the plurilingual individual and/or of the plurilingual competence

3.1 Assessment of the competences of the plurilingual individual

A high number of publications focus on the assessment of knowledge and competences in non-linguistic subjects (Canagarajah, 2006, 2012; Schissel, 2019; Schissel et al., 2018; Shohamy, 2011, 2006, 2022, 2001; Shohamy et al., 2017). Most of them show that monolingual practices are creating cruel inequity and do not allow a fair and valid evaluation of what is supposed to be assessed.

Melo-Pfeifer and Ollivier (2023b, pp. 8-9) highlight that one form of discrimination in education is the practice of testing individuals from diverse linguistic and cultural backgrounds using a uniform, standardized format. The lack of consideration for the familiarity of test-takers with the language and culture of the test can have adverse effects on the results (Altakhaineh and Melo-Pfeifer, 2022). For example, Shohamy (2011) observed that Russian immigrants in Israel who were tested in Hebrew on their mathematical competencies achieved lower scores than native speakers. The research also indicated that the scores of this population were higher when the test was conducted in their first language. Furthermore, the study demonstrated that the disparate scores persisted over time, with Russian immigrants requiring 9 to 11 years to attain the same scores as native speakers.

Wright and Li (2008) demonstrated that poor proficiency in the language used in national tests in the USA creates “a source of construct irrelevance” (p. 8). They showed that the vocabulary and syntactic complexity of the task, as well as the cultural content of the tests, made them difficult for non-native speakers to understand.

This understanding of the plurilingual assessment is concerned with social justice and equity in education, through the development of “fair and equitable forms of evaluation for all students, regardless of prior language background, educational context and geographical location” (De Angelis, 2021, p. 1). Under the practices developed to reach fairer formats of evaluation, we could name testing accommodations (De Backer et al., 2019; Shohamy and Menken, 2015) including, for instance, providing students with more time to answer, reducing the number of questions or allowing students to use external resources (for example, dictionaries and online translation tools). Other strategies, more responsive in terms of students’ communicative repertoires, include presenting content in the student’s own language, allowing answers in multiple languages, and the use of home languages and other semiotic resources (Shohamy and Pennycook, 2019; Vogt and Antia, 2024).

3.2 Assessment of the plurilingual competence

In the domain of plurilingual competence assessment, research has particularly documented and analyzed practices since the end of the previous century. The methods of assessment can be grouped into two principal categories: hybrid and holistic/integrated (Melo-Pfeifer and Ollivier, 2023b).

3.2.1 Hybrid assessment

The term “hybrid” is used to describe any form of evaluation that involves the assessment of language skills separately, rather than as a unified competence. In this category we can distinguish between assessment procedures that aim to establish a plurilingual profile and procedures that calculate plurilingual indices.

An exemplary illustration of the profile approach can be found in the work of Jamet (2010) within the context of intercomprehension. The author delineates the methodology employed for the assessment of students’ receptive skills in distinct Romance languages. Monolingual tests were used for the certification of proficiency levels in the respective languages. This procedure enabled the construction of a competence profile in intercomprehension, specifically with regard to the various languages belonging to the Romance group.

The use of self-assessment grids in various languages within the European portfolio, particularly within the language passport, is grounded in the same fundamental principle, albeit with a specific emphasis on self-assessment. The absence of “can do” descriptors for plurilingual competence in the original version of the CEFR is indicative of a similar approach to assessment, namely one that is conducted for each language separately.

A score-based approach is advocated by authors who propose to utilize the scores obtained in distinct language assessments to calculate a plurilingualism index. Cenoz et al. (2013) describe an assessment procedure in the Spanish Basque Country in which learners’ competencies were assessed in three languages: Basque, Spanish and English. Subsequently, the scores in Basque and Spanish were added to calculate an index of bilingualism, and the score in all three languages was used to determine a plurilingualism index.

Another score-based approach is presented by Mueller Gathercole et al. (2013), who argue that it is not possible to evaluate a child’s abilities in one language and use the results as a measure of their skills in another language, or as an indicator of their general language proficiency. To address this issue, the authors propose two solutions. First, they recommend developing assessment tools that take each child’s individual language background and experiences into account, particularly the language used at home. Second, when tests are conducted in only one language, they suggest that each child should be given two standardized scores: one that compares their results to those of all children of the same age, and another that compares them to peers with similar language backgrounds.

In all these forms of assessment, monolingual tests are used to construct a plurilingual profile or to calculate an index of plurilingualism. We will now look at procedures that are basically plurilingual and integrate different languages in the same test.

3.2.2 Holistic/integrated assessment

Assessment designated as “holistic/integrated” focuses on the evaluation of plurilingual competence as a unique and complex ability, integrating the use of multiple languages into the assessment process. Two main options in this category can be identified: the promotion of the use of translanguaging, and integrated assessment of plurilingual assessment, especially in intercomprehension across languages of the same linguistic family.

Considering that assessment procedures should allow students to use and value their entire linguistic or semiotic repertoire [or, in the words of García and Wei (2014, p. 127), to be “virtuoso language users, rather than just careful and restrained language choosers”], a number of scholars working in the field of translanguaging advocate for forms of assessment that accept and nurture translinguistic and transsemiotic practices. Students should be allowed or even encouraged to make full use of all their resources without being restricted by socially and politically established language boundaries (García and Kleifgen, 2019; García and Wei, 2014). Consequently, plurilingual tasks should be provided “for which it is understood by the test-takers that mixing languages is a legitimate act that does not result in penalties but rather is an effective means of expressing and communicating ideas that cannot be transmitted in one language” (Shohamy, 2011, p. 427).

The following section presents two European projects that have adopted a distinct holistic/integrated approach. The projects have been chosen because they address two aspects of the plurilingual competence (the communicative competence in Romance languages through intercomprehension and crosslinguistic mediation competences) and use distinct procedures. The analysis of the different aims and approaches provides insights into commonalities and divergences in the assessment procedures and help to understand the diversity of possible types of assessment.

4 Two European projects

4.1 EVAL-IC: evaluation of competences in intercomprehension

The EVAL-IC project (https://www.evalic.eu) is a European project co-funded by the European Union within the Erasmus+ program. It aimed at describing and assessing plurilingual competence, in particular Romance intercomprehension competence. Intercomprehension is understood as a form of plurilingual competence in which speakers of different languages can understand each other using different languages of the same group - in this case Romance languages.

Descriptors have been designed for oral and written comprehension of narrow languages, for production in a familiar language so that speakers/writers can make themselves understood by people who have never learnt the language they use, and for plurilingual interaction. These descriptors address the different dimensions of the communicative competence: linguistic, sociocultural, pragmatic, etc., and establish six levels of proficiency (Ollivier et al., 2019).

On the basis of these descriptors and the above-mentioned definition of intercomprehension as a plurilingual form of communication involving four different language activities, an assessment protocol was designed and a pilot test carried out. The project team decided to apply the TBLA-approach (task-based language assessment) (Bachman, 1990; Bachman and Palmer, 1996; Ellis et al., 2020; Norris, 2016). Therefore, a global scenario has been chosen including different subtasks, each contributing to a coherent project.

This test was intended to be plurilingual, not only because several languages had to be activated by the students at different stages, but also because different languages were used in the subtasks.

The pilot scenario for Romance languages designed by the EVAL-IC team for university students reflects the application and selection process for the participation in an international conference on sustainable development in higher education. In the initial stage, which addresses written reception, students are required to complete an application form in a Romance language of their choice or in the official language of their university. The questions are posed in a variety of romance languages. Thereafter, the students are provided with written and video materials pertaining to sustainable solutions for universities in five Romance languages (French, Italian, Portuguese, Romanian, and Spanish). Based on their comprehension of these materials, the students are required to produce a PowerPoint presentation and an oral presentation for a plurilingual jury, who will engage in questioning in different languages. The final phase is dedicated to the participation in an online forum with other students writing in different languages in order to select a concrete action for sustainable development that can be implemented during the conference.

4.2 METLA: mediation in teaching, learning and assessment

The METLA project (www.ecml.at/mediation), running from 2020 to 2022 and coordinated by Maria Stathopoulou, was rooted in educational methodologies that embrace diversity, particularly focusing on the significance of plurilingual and pluricultural competence. The project highlights the importance of students becoming proficient in navigating multiple languages and cultures, preparing them for effective communication across languages instead of in monolingualized communicative contexts. A key objective of the project was to provide teachers with the tools and knowledge to help them cultivate, nurture, and assess their students’ mediation skills (Stathopoulou et al., 2023). Crosslinguistic mediation involves facilitating understanding and communication between individuals or groups from different linguistic and cultural backgrounds.

The project’s outcomes strongly resonate with the core values and principles championed by the Council of Europe (see Introduction to this paper). These include a firm commitment to upholding (linguistic) human rights, fostering mutual understanding, and encouraging social cohesion across communities. The METLA project also places a strong emphasis on language inclusion, promoting the idea that multiple languages should be embraced rather than excluded in educational settings, in general, and in the language classroom more specifically. Indeed, since the introduction of the direct method - derived from foreign language learning theories based on L1 acquisition concepts such as exposure to input and immersion - the language classroom has tended to banish other languages from students’ repertoires, whether or not acquired in formal contexts. By introducing the skill of crosslinguistic mediation into the list of skills to be developed in the language classroom, the CEFR challenges this hegemony of monolingualism and the monolingualization of students in the classroom. As promoted by the CEFR Companion Volume, “in mediation, the user/learner acts as a social agent who creates bridges and helps to construct or convey meaning, sometimes within the same language, sometimes from one language to another (crosslinguistic mediation)” (2020, p. 90). This means that crosslinguistic mediation (also called interlinguistic mediation in the above-mentioned Companion Volume), as a competence integrated in language curriculum, legitimized the use of different languages in the classroom, providing realistic scenarios to understand the concomitant use of languages in communication, instead of aiming at monolingualization of communication through the use of a common language only.

As put forward by Stathopoulou et al. (2024), “Mediation in METLA tasks entails the purposeful selection of information by the mediator from a source text in one language and the relaying of this information into another language, with the intention of bringing closer interlocutors who do not share the same language. Cross-linguistic mediation can thus be taught and assessed through METLA tasks which ask for the use of different languages (i.e., passing on information from one language to another), thus softening linguistic and cultural gaps in the process” (p. 247).

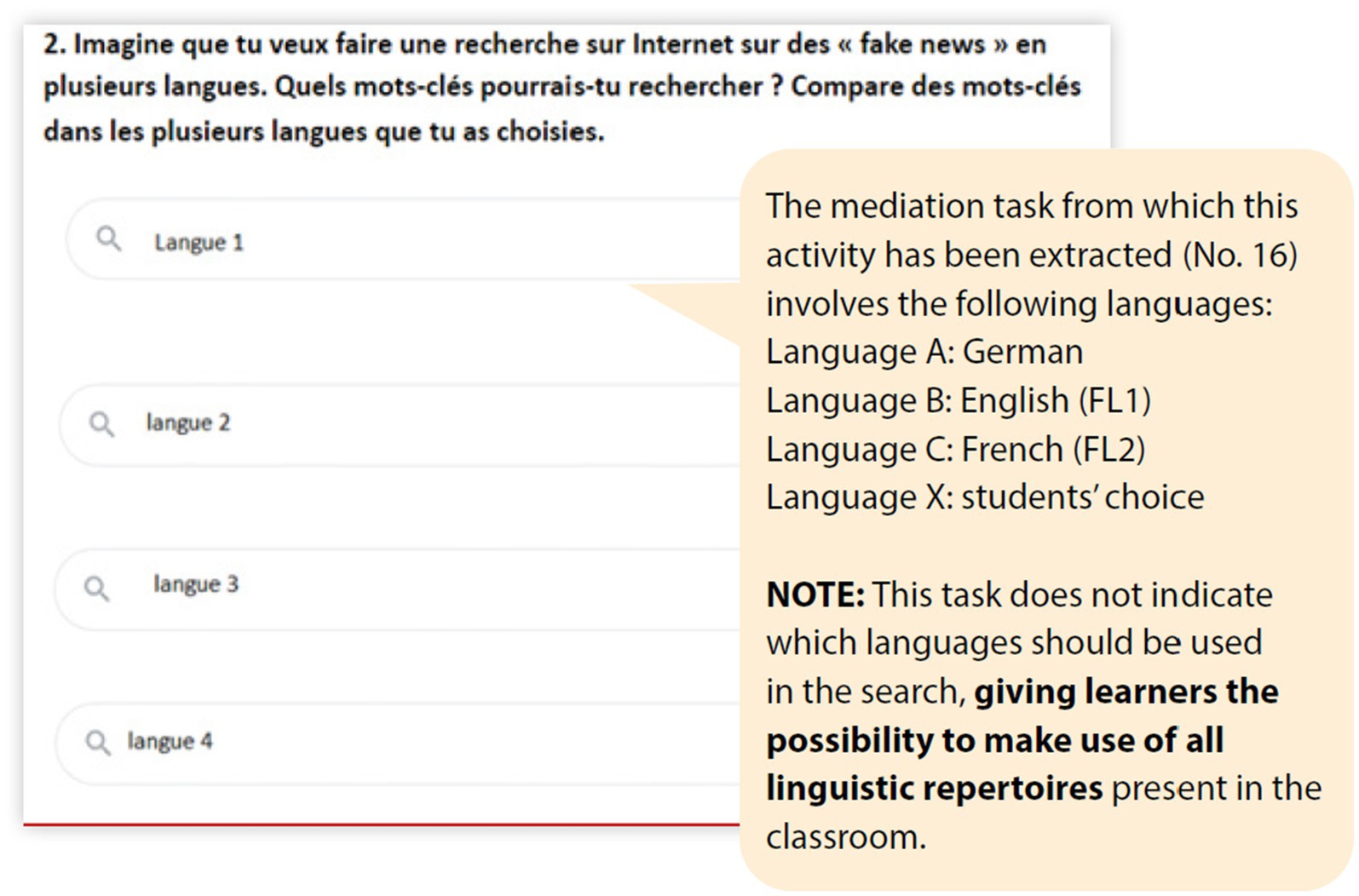

Figure 1 reproduces one task of the METLA project, which shows the incorporation of students’ plurilingual C the task. The students are also required, after task completion, to evaluate their learning process.

Figure 1. Example of mediation task (Stathopoulou et al., 2023, p. 49).

In the METLA project, the cross-linguistic mediation tasks are designed to be inherently plurilingual, encouraging learners to recognize and utilize their additional or foreign languages, grounding these activities in their linguistic biographies and sociolinguistic realities. These tasks specifically prompt students to purposely build linguistic connections, identify similarities and differences between languages, and combine various languages with non-verbal resources (such as gestures, facial expressions, body language, and visual aids) for diverse communicative purposes (sending an email, communicating in online applications, producing flyers, etc.). By doing so, the tasks promote students’ engagement in and appreciation of language negotiation, encouraging them to navigate across languages and collaboratively construct meaning in plurilingual contexts (Stathopoulou et al., 2023, 2024). Privileged formats of assessment in this project are formative and based in self-reflection (such as Portfolios), encouraging students to return to their production and to the learning process, so that they develop agency over the learning processes.

4.3 Commonalities and differences

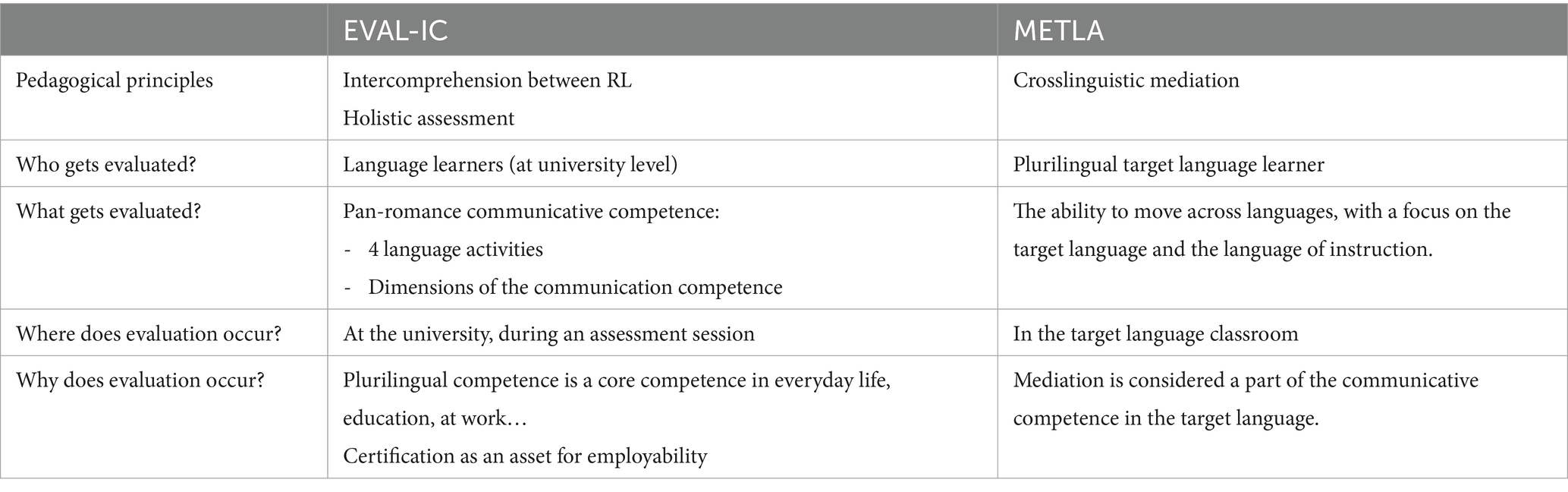

Both projects were designed for language education programs and focus on the plurilingual competence of plurilingual subjects. The main goal was not to assess the student’ proficiency and knowledge in subjects other than languages but to evaluate their capacity to use their entire linguistic and semiotic repertoires for effective plurilingual communication. EVAL-IC and METLA opened space to languages beyond the language of instruction and the target language in the language classroom, creating - among other - spaces for translanguaging in a holistic approach to plurilingual communication and plurilingual competence. Table 2 reflects the main key-points of the two projects.

In the EVAL-IC and METLA projects, because they targeted mostly language learners, plurilingual assessment formats were not specifically drawn for newcomers to a new school system. Nevertheless, such formats can be used to show the unique challenges newcomer students face and the potential they bring with. Indeed, when integrating a new school system, especially in the European context where the learning of two foreign languages is mandatory, newcomer students are concomitantly learning the language of schooling and potentially two other languages. Even if students do not have a mobility background, they already developed skills in the language of schooling and are developing competences in two additional languages. In some cases, they also have some or full command in a heritage language. Such consideration for a plurilingual competence also calls for the development of plurilingual pedagogies and the implementation of multilingual assessment formats.

As shown in Table 2, both projects emphasized the importance of valuing plurilingual education for all students, highlighting how such formats not only support language learning but also enhance the development of transversal competences, such as cognitive flexibility, critical thinking, and intercultural understanding in diverse educational contexts. By encouraging students to draw on their entire linguistic repertoire, both projects fostered deeper engagement with the learning process and contributed to a more inclusive, learner-centered environment. By legitimizing multilingual learning pedagogies for all students, plurilingual assessment formats as promoted in the two projects also address some potential otherization occurring when these pedagogies and assessment formats are exclusively tailored to plurilingual students’ (supposed) needs.

Additionally, EVAL-IC and METLA aimed at promoting an appreciation for and recognition of individual plurilingualism, not only in the classroom but across various social and cultural settings, ensuring that students’ plurilingual abilities are acknowledged and nurtured as valuable assets, inside and outside the school.

Our study shows that new formats for assessing plurilingual competence are possible, especially procedures that integrate different languages without separating them, but rather promoting the holistic activation of all the students’ semiotic resources. Both approaches are different from those suggested by Jamet (2010), Mueller Gathercole et al. (2013) or Cenoz et al. (2013). They show that it is realistic to conceptualize and successfully implement types of assessment that do not measure competences in different languages in order to establish a plurilingual profile or calculate an index of plurilingualism. Instead, the projects consider plurilingualism as a holistic competence which makes use of all semiotic resources in order to accomplish complex communicative tasks. This study therefore provides evidence that the multilingual turn in education can include assessment and that alignment between teaching and assessment is achievable.

5 Synthesis and pedagogical implications

EVAL-IC and METLA projects highlighted a shift in language education from monolingual practices and traditional language proficiency assessment toward a more holistic understanding of the plurilingual competence. Their suggestions place the languages at the core of the activities and embrace holistic language assessment. Indeed, both projects prioritize evaluating students’ ability to use their full linguistic and semiotic repertoire rather than focusing solely on their proficiency in specific languages. In terms of pedagogical implication, this could encourage language educators to assess how students navigate and cross different languages and communicative tools for effective plurilingual communication. By emphasizing such a stance, EVAL-IC and METLA offer a broader and more inclusive understanding of language learning and of competence as going beyond mastery of isolated, juxtaposed (named) languages.

Because EVAL-IC and METLA were designed mainly for mainstream formal language education settings, they do not target newcomers to a new school system, learning the language of schooling. Their plurilingual evaluation formats support plurilingual learners with different profiles, also when they have developed such a profile “just” by learning foreign languages at school. By doing this, the two projects promote plurilingualism to all students, and make it clear that the development of a plurilingual competence is (also) a task of the school. Nevertheless, although the projects were not specifically designed for newcomers to a new school system, the frameworks they provide can still benefit these students, as they encourage the recognition and integration of all the languages in a student’s repertoire for assessment purposes. Additionally, the task formats developed in the two projects can play an important role in supporting students, especially those with heritage language or mobility backgrounds. These students may feel more validated and engaged in their learning when they see that their languages are not merely used as tools or scaffolds for learning - a practice that can sometimes be viewed through a deficit lens. Instead, the plurilingual procedures developed in the projects consider the learners’ languages as genuine and legitimate means of demonstrating their abilities and the outcomes of their learning.

In a nutshell, the EVAL-IC and METLA projects suggest that language education should move toward a more dynamic, inclusive, and competency-based model that reflects the plurilingual realities of learners and the multilingualism of societies. More importantly, both projects call for the development and implementation of plurilingual pedagogies and assessment formats that challenge the monolingual mindset in language education and reflect real-world plurilingual communication.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

SM-P: Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CO: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The study was carried out in the framework of the PEP project (2023–1-FR01-KA220-HED-000160820), co-funded by the European Commission as an Erasmus+ cooperation partnership in Higher Education. The EVAL IC project (https://www.evalic.eu), run from 2016 to 2019, was coordinated by Christian Ollivier (University of Réunion Island). It was co-funded by the European Union within the Eramus+ program, with the project number 2016-1-FR01-KA203-024155. The METLA project (www.ecml.at/mediation), which run from 2020 to 2022, was coordinated by Maria Stathopoulou, and financed by the European center for Modern Languages from the Council of Europe. Funding from the University of Hamburg was received for the publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Altakhaineh, A., and Melo-Pfeifer, S. (2022). ‘This topic was inconsiderate of our culture’: Jordanian students’ perceptions of intercultural clashes in IELTS writing tests. Appl. Linguist. Rev. 15, 263–286. doi: 10.1515/applirev-2021-0183

Bachman, L. F. (1990). Fundamental considerations in language testing. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bachman, L. F., and Palmer, A. S. (1996). Language testing in practice: Designing and developing useful language tests. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Beacco, J.-C., and Byram, M. (2007). From linguistic diversity to Plurilingual education: Guide for the development of language education policies in Europe. Main version. Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing.

Beacco, J.-C., Byram, M., Cavalli, M., Coste, D., Cuenat, M. E., Goullier, F., et al. (2016). Guide for the development and implementation of curricula for plurilingual and intercultural education. Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing.

Caddéo, S., and Jamet, M.-C. (2013). L’intercompréhension, Une autre approche pour l’enseignement des langues. Paris: Hachette.

Canagarajah, S. (2006). Changing communicative needs, revised assessment objectives: testing English as an international language. Lang. Assess. Q. 3, 229–242. doi: 10.1207/s15434311laq0303_1

Canagarajah, S. (2012). Translingual practice: Global Englishes and cosmopolitan relations. London: Routledge.

Candelier, M., Andrade, A. I., Bernaus, M., Kervran, M., Martins, F., Murkovska, A., et al. (2003). Janua linguarum: The gateway to languages: The introduction of language awareness into the curriculum: Awakening to languages. Strasbourg: Council of Europe.

Candelier, M., Camilleri-Grima, A., Castellotti, V., De Pietro, J.-F., Lörincz, I., Meißner, F.-J., et al. (2012). FREPA. A framework of reference for pluralistic approaches to languages and cultures: competences and resources. Graz: Conseil de l’Europe, Centre européen pour les langues vivantes CELV, Strasbourg.

Candelier, M, Manno, G, and Escudé, P. (2023). La Didactique Intégrée Des Langues – Apprendre Une Langue Avec d’autres Langues? ADEB. Available online at: http://www.adeb-asso.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/2023-La-didactique-Int%C3%A9gr%C3%A9e-des-langues.pdf.

Cenoz, J., Arozena, E., and Gorter, D. (2013). “Multilingual students and their writing skills in Basque, Spanish and English,” in Bilingual assessment: Issues and solutions. ed. V. M. Gathercole (Bristol: Multilingual Matters), p. 186–205.

Cenoz, J., and Gorter, G. (2021). Pedagogical Translanguaging. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Civil Society Platform on Multilingualism. (2011). Policy Recommendations for the Promotion of Multilingualism in the European Union. Full Version. Available online at: http://ec.europa.eu/languages/pdf/doc5088_en.pdf (Accessed June 19, 2025).

Committee of Ministers (2014). Recommendation CM/Rec(2014)5 of the committee of ministers to member states on the importance of competences in the language(s) of schooling for equity and quality in education and for educational success. Council of Europe. https://search.coe.int/cm/Pages/result_details.aspx?ObjectID=09000016805c6105.

Conseil de l’Europe, Comité des Ministres (2022). Recommandation CM/Rec(2022)1 du comité des ministres aux états membres sur l’importance de l’éducation plurilingue et interculturelle pour une culture de la démocratie. Available online at: https://www.ecml.at/Portals/1/documents/about-us/CM_Rec(2022)1F.pdf

Cook, V. (2016). Working Definition of Multi-Competence. Vivian Cook. Available at: http://www.viviancook.uk/Writings/Papers/MCentry.htm.

Coste, D., Moore, D., and Zarate, G. (1997). Compétence plurilingue et pluriculturelle. Vers un cadre européen commun de référence pour l’enseignement et l’apprentissage des langues vivantes. Études préparatoires. Strasbourg: Conseil de l’Europe.

Council of Europe (Ed.) (2001). Common European framework of reference for languages: Learning, teaching, assessment. Cambridge: Press syndicate of the University of Cambridge.

Council of the European Union (2019). Council recommendation of 22 May 2019 on a comprehensive approach to the teaching and learning of languages. Available online at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32019H0605(02)

Cummins, J. (1981). “The role of primary language development in promoting educational success for language minority students,” in Schooling and language minority students: A theoretical framework (Los Angeles: California State University: California State Department of Education), 16–62.

Cummins, J. (2001). Language, power and pedagogy: Bilingual children in the crossfire. London: Multilingual Matters.

Cummins, J. (2019). The emergence of Translanguaging pedagogy: a dialogue between theory and practice. J. Multilingual Educ. Res. 9:1.

De Backer, F., Slembrouck, S., and Van Avermaet, P. (2019). Assessment accommodations for multilingual learners: pupils’ perceptions of fairness. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 40, 833–846. doi: 10.1080/01434632.2019.1571596

Dervin, F., and Liddicoat, A. (2013) in Linguistics for intercultural education. eds. F. Dervin and A. Liddicoat, vol. 33 (Amsterdam; Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing).

Ellis, R., Skehan, P., Li, S., Shintani, N., and Lambert, C. (2020). Task-based language teaching: Theory and practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Escudé, P., and Janin, P. (2010). Le point sur l’intercompréhension, clé du plurilinguisme. Paris: Clé international.

Fornel, Th.de (2023). De l’intercompréhension entre langues romanes: sources, tensions et variations épistémologiques. Phd thesis, Université de Bordeaux; Universidade Federal do Paraná (Brésil). Available online at: https://theses.hal.science/tel-04417897 (Accessed June 19, 2025).

Garbarino, S., and Degache, C. (2017). Itinéraires pédagogiques de l’alternance des langues: L’intercompréhension. Grenoble: UGA.

García, O., and Kleifgen, J. A. (2019). Translanguaging and literacies. Read. Res. Q. 55, 553–571. doi: 10.1002/rrq.286

García, O., Lin, A. M. Y., and May, S. (Eds.) (2017). Bilingual and multilingual education. Cham: Springer.

García, O., and Wei, L. (2014). Translanguaging: Language, bilingualism and education. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Grosjean, F. (1982). Life with two languages: An introduction to bilingualism. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Hufeisen, B., and Lindemann, B. (1998). Tertiärsprachen: Theorien, Modelle, Methoden. Tübingen: Stauffenburg.

Hufeisen, B., and Neuner, G. (2003). Mehrsprachigkeitskonzept - Tertiärsprachenlernen - Deutsch nach Englisch. Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing.

Jamet, M.-C. (2010). Intercomprensione, Quadro Comune Europeo Di Riferimento per Le Lingue, Quadro Di Riferimento per Gli Approcci Plurilingui e Valutazione. Synergies Europe Intercompréhension(s) 5, 75–98.

Lenz, P., and Berthele, R. (2010). Assessment in plurilingual and intercultural education guide for the development and implementation of curricula for Plurilingual and intercultural education. Satellite study 2. Strasbourg: Council of Europe https://www.coe.int/t/dg4/linguistic/Source/Source2010_ForumGeneva/Assessment2010_Lenz_ENrev.pdf.

May, S. (2013). The multilingual turn: Implications for SLA, TESOL, and bilingual education. New York: Routledge.

Melo-Pfeifer, S., and Ollivier, C. (2023a). Assessment of plurilingual competence and plurilingual learners in educational settings: Educative issues and empirical approaches. London: Routledge.

Melo-Pfeifer, S., and Ollivier, C. (2023b). “On the unbearable lightness of monolingual assessment practices in education” in Assessment of Plurilingual competence and Plurilingual learners in educational settings. eds. S. Melo-Pfeifer and C. Ollivier (London: Routledge), 1–27.

Mueller Gathercole, V., Thomas, E. M., Roberts, E.J., Hughes, C.O., and Hughes, E.K. (2013). Why assessment needs to take exposure into account: vocabulary and grammatical abilities in bilingual children, in Issues in the assessment of bilinguals, ed. V. C. Mueller Gathercole (Bristol; Buffal; Toronto: Multilingual Matters), 20–55.

Norris, J. M. (2016). Current uses for task-based language assessment. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ollivier, C., Capucho, F., and Araújo e Sá, M. H. (2019). Defining intercomprehension competencies as prerequisites for their assessment. Rivista di psicolonguistica applicata. J. Appl. Psycholing. XIX, 15–30. doi: 10.19272/201907702002

Schissel, J. L. (2019). Social consequences of testing for language-minoritized bilinguals in the United States. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Schissel, J. L., De Korne, H., and López-Gopar, M. (2018). Grappling with translanguaging for teaching and assessment in culturally and linguistically diverse contexts: teacher perspectives from Oaxaca, Mexico. Int. J. Biling. Educ. Biling. 24, 340–356. doi: 10.1080/13670050.2018.1463965

Shohamy, E. (2001). The power of the tests. A critical perspective on the use of language tests. Harlow: Longman.

Shohamy, E. (2006). “Rethinking assessment for advanced language proficiency” in Educating for advanced foreign language capacities: Constructs, curriculum, instruction, assessment. eds. K. A. Sprang, H. Weger-Guntharp, and H. Byrnes (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press), 188–208.

Shohamy, E. (2011). Assessing multilingual competencies: adopting construct valid assessment policies. Mod. Lang. J. 95, 418–429. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4781.2011.01210.x

Shohamy, E. (2022). Critical language testing, multilingualism and social justice. TESOL Q. 56, 1445–1457. doi: 10.1002/tesq.3185

Shohamy, E., and Menken, K. (2015). “Language assessment: Past to present misuses and future possibilities”, in The handbook of bilingual and multilingual education, ed. W. E. Wright, S. Boun, and O. García (Oxford: Wiley Blackwell), 253–269.

Shohamy, E., Or, I. G., and May, S. (2017). Language testing and assessment. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Shohamy, E., and Pennycook, A. (2019). “Extending fairness and justice in language tests” in Social perspectives on language testing: Papers in honor of Tim McNamara. eds. C. Roever and G. Wigglesworth (Berlin: Peter Lang), 29–45.

Stathopoulou, M., Gauci, P., Liontou, M., and Melo-Pfeifer, S. (2023). Mediation in teaching, Learning & Assessment (METLA). A teaching guide for language educators. Graz: European Centre for Modern Languages of the Council of Europe.

Stathopoulou, M., Liontou, M., Gauci, Ph., and Melo-Pfeifer, S. (2024). “Assessing cross- linguistic mediation: Insights from the METLA project”, in Multilingual assessment – Finding the nexus?, ed. K. Vogt and B. Antia (Berlin: Peter Lang), 235–258.

Vogt, K., and Antia, B. (2024). “Introduction: Multilingual assessment – Finding the nexus?” in Multilingual assessment – Finding the nexus? eds. K. Vogt and B. Antia (Berlin: Peter Lang), 9–23.

Keywords: plurilingual competence, plurilingual individual, plurilingual assessment, crosslinguistic mediation, educational linguistic policies

Citation: Melo-Pfeifer S and Ollivier C (2025) Assessing the plurilingual competence and plurilingual individuals’ skills and knowledge: similarities and divergences. Front. Commun. 10:1498940. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2025.1498940

Edited by:

Andrea Listanti, University of Cologne, GermanyReviewed by:

Magdalena Lopez-Perez, University of Extremadura, SpainAntri Kanikli, University of Central Lancashire, Cyprus

Copyright © 2025 Melo-Pfeifer and Ollivier. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sílvia Melo-Pfeifer, c2lsdmlhLm1lbG8tcGZlaWZlckB1bmktaGFtYnVyZy5kZQ==

Sílvia Melo-Pfeifer

Sílvia Melo-Pfeifer Christian Ollivier

Christian Ollivier