- University of Tasmania, Hobart, TAS, Australia

This community case study explores the experiences of renters in Hobart, Australia’s most bushfire-prone capital, to understand how they live with and prepare for bushfire risk. Renters, a growing but often overlooked population, face distinct challenges, including limited property rights and communication that rarely reflects their circumstances. The study drew on arts-based workshops and follow-up surveys, guided by principles of disaster justice. Findings show that renters identified a series of anchors that sustained their sense of security in the face of bushfire risk. These anchors included tenure-related conditions that shaped perceptions of risk and capacity to act, sensory cues such as the smell of bushland that offered familiarity, ecological ties that connected people to land and more-than-human life, and social ties that reinforced belonging. Bushfire risk unsettled these anchors, disrupting routines and relationships that supported stability. Attending to these lived experiences highlights how preparedness strategies can be made more relevant to renters and support more inclusive approaches to bushfire readiness.

1 Introduction

The protection of life and property is articulated as the central objective of bushfire governance in Australia, and it directs how agencies communicate with the public (Council of Australian Governments, 2011). This objective reflects a settlement history shaped by low-density suburban expansion and the ideal of private ownership that came to define Australian peri-urban life (Davison, 2006). These conditions have positioned private property and nuclear families as the default units of governance. Over the past four decades, neoliberal reforms have reinforced this orientation by limiting the role of government agencies and expanding individual responsibility for risk (Beeson and Firth, 1998; Stonehouse et al., 2015). Scholars continue to debate the precise effects of these reforms (Higgins, 2014; Weller and O’Neill, 2014), yet one consequence is evident. Neoliberal governance promotes the autonomy of private individuals even as it contributes to declining home ownership and a rise in private renting. Real estate markets, structured as vehicles of capital accumulation, have intensified this shift (Booth et al., 2022).

Neoliberal influence on governance became visible in bushfire policy through the “shared responsibility” framework adopted after the 2009 Victorian fires (McLennan and Handmer, 2014; Crosweller and Tschakert, 2021). This framework positioned bushfire risk management as a partnership between individuals and agencies rather than a task of the agencies alone (Bushfire CRC, 2009). It redefined the scope of institutional responsibility by expanding agencies’ roles from operational response to the continual communication of preparedness (Council of Australian Governments, 2011). In this shift, responsibility was redistributed rhetorically as shared, but operationally extended to the public. Within these communications, preparedness is typically depicted as a private responsibility carried out within the household and represented through the cultural archetype of the home-owning nuclear family (Yildiz et al., 2025). Renters, who now account for 30.6% of Australia’s population (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2022a), remain largely absent from these campaigns, which, even when tenure is not specified, tend to suggest measures more accessible to owners than renters.

The population of Australian renters is both growing and diversifying (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2022a). Once linked primarily to low-socioeconomic groups, renters now include middle-class households, people from varied ethnic backgrounds, a range of household structures and different age groups and occupations, as well as those facing multiple forms of social marginalisation (Booth et al., 2022). This demographic shift reflects broader housing dynamics shaped by neoliberal reform, where markets channel investment into property and reduce access to ownership. In this context, assumptions about renters and their needs in bushfire preparedness can no longer be based on narrow categories but must account for this wider social and economic spectrum.

The growing diversity of renters contrasts with their continued absence from fire agency communication and bushfire research. One recent exception is a study in Hobart, which found that renters were less prepared for bushfire than homeowners, had less direct experience of bushfire and showed weaker comprehension of official warnings (Campbell et al., 2024). Australian research confirms these patterns (Beringer, 2000; Solangaarachchi et al., 2012; McDonald and McCormack, 2022), as does international scholarship (Collins, 2008; Wisner et al., 2012; Rivera, 2020; Dundon and Camp, 2021). Collectively, this body of work demonstrates consistent differences between renters and homeowners in levels of preparedness. Wisner et al. (2012) report that rental properties are often less well maintained than owner-occupied houses. Dundon and Camp (2021) identify that renters lack the incentive or authority to implement risk-reducing improvements, a challenge also observed by Collins (2008) in the United States, where insecure livelihoods and limited authority constrained preparedness. In Australia, McDonald and McCormack (2022) note that renters are legally restricted from modifying properties or clearing vegetation to reduce bushfire risk, while Solangaarachchi et al. (2012) highlight how the transient nature of renting limits awareness of local hazards. These findings suggest that housing systems privilege ownership as the basis for protective action, reducing renters’ capacity to address disaster risk. This has important implications for developing more inclusive approaches to preparedness.

Bushfire risk in Hobart is concentrated on the peri-urban fringe, where residential expansion extends into bushland valleys and ridges at the base of Kunanyi/Mount Wellington (City of Hobart, 2022; Anderson and Whitman, 1967). Scholars describe peri-urban zones also termed wildland-urban interfaces as thresholds where urban growth, conservation and fire management imperatives converge. This convergence creates landscapes that are dynamic and contested, shaped by competing pressures over how land is used and how risk is understood (Lucas et al., 2022; Koksal et al., 2020; Ondei et al., 2024). According to the Hobart Bushfire Exposure Index, more than 94,000 buildings across Greater Hobart are assessed for exposure, heavily concentrated in the Hobart and Kingborough Local Government Areas (National Emergency Management Agency, 2024; Geoneon, 2024).

Hobart’s history also shows how fires that ignite at the fringe can move inward: the 1967 fires advanced from the surrounding hills toward the city centre (Anderson and Whitman, 1967). The city’s risk profile reflects the interaction between its topography and its settlement history. Peri-urban residence expresses both a lifestyle preference for proximity to bushland and the housing market pressures that push people toward these areas. These conditions expose how bushfire risk is shaped through the entanglement of geography and housing systems.

This study examines renters’ experiences and feelings about bushfire risk and preparedness through the lens of disaster justice. Disaster justice refers to the fair treatment of all people in policies and practices relevant to catastrophic hazards, including preparedness (Verchick, 2012). Disasters are known to affect populations unevenly due to social and economic marginalisation (Blake et al., 2017), and housing tenure is an important contributor in this unevenness (McCarthy and Friedman, 2023; Lambrou et al., 2023). Renters are particularly exposed, yet their perspectives have rarely been included in bushfire research or preparedness communication.

The research draws on Playback Theatre workshops and follow-up surveys and addresses two questions:

RQ1: How do renters perceive and feel about bushfire risk?

RQ2: How can understanding renters’ experience (and feelings) about bushfires inform future bushfire communication?

As private renters make up a growing share of the Australian population (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2022a), their exposure to bushfire risk in a changing climate is becoming a critical issue (Li et al., 2024; Jones et al., 2024). This study investigates how renters experience bushfire risk and security, showing how these experiences reveal alternative ways of preparing that reflect their circumstances. Preparedness campaigns in Australia have centred on homeownership and property protection, while tenure insecurity and other constraints limit renters’ capacity to act. Addressing this gap requires attention to equity in preparedness communication so that renters’ security is recognised alongside that of homeowners. To support this, the analysis draws on the concept of ontological security to consider how security is sustained through continuities of place and relationships. The paper then outlines the methodology and presents findings from Hobart, where renters account for 35.6% of the population (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2022b) and the city is recognised as Australia’s most bushfire-prone capital (Lucas et al., 2022).

2 Homeowning democracies and security

In many Western societies, particularly in Anglophone countries such as Australia, home ownership has been central to discourses of nationhood, citizenship and personal security (Pawson et al., 2019; Crabtree, 2016; Donoghue, 2010; Parliamentary Library, 2025). In these home-owning democracies, the availability of property and the aspiration to own shape material lives, political values and personal identities, as well as class structures and social policies (Hulse et al., 2019; Booth et al., 2022; Dupuis and Thorns, 1998). Across Anglophone democracies, governments promoted home ownership throughout the twentieth century as a means of building territorial attachment, strengthening nation-building and securing social and economic cohesion (Clark, 2013).

Post-war housing policies in Australia reflected these patterns. They positioned home ownership as a marker of middle-class life and a symbol of stability, security and belonging for the settler population (Forrest and Hirayama, 2015; Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute, 2019). The Great Australian Dream of purchasing a detached home through capitalist real estate markets stood at the centre of the post-World War II social contract (Forrest and Hirayama, 2015). Owning a detached house with a private yard was treated as a measure of prosperity and reinforced the notion of an “Australian” identity. The aspiration for asset egalitarianism through home ownership (Gamble and Prabhakar, 2005) aimed to strengthen social cohesion and protect individuals during periods of economic volatility and precarity (Forrest and Hirayama, 2015; Hulse and Saugeres, 2008). Housing became the most significant store of intergenerational wealth and came to be regarded by governments and the public alike as an unofficial fourth pillar of the retirement system, alongside the age pension, compulsory superannuation and voluntary savings (Australian Government Treasury, 2020). Home ownership was intended to promote stability and cohesion. Yet financialised housing markets under neoliberal reform have made it increasingly exclusive, particularly across generations. A sustained decline in affordability has reframed the Great Australian Dream as a nightmare in mainstream media (Verrender, 2024). The State of the Housing System 2024 report, the first annual publication of the National Housing Supply and Affordability Council, records sharp declines in home ownership opportunities and surging rents in 2023 with record-low vacancy rates (National Housing Supply and Affordability Council, 2024). These pressures fall most heavily on vulnerable groups, including low-income households, single parents, young people, pensioners, people with disabilities, and First Nations Australians, as well as those fleeing domestic violence (National Housing Supply and Affordability Council, 2024).

Bushfires in Australia have long been defined as crises for the destruction they bring to homes and lives (Gill, 2005). This focus has tied disaster policy to the same cultural ideals of home that underpin Australia’s housing system, positioning property as the locus of safety, identity and responsibility. For decades, communication emphasised the right of homeowners to defend their properties, a belief that underpinned the “stay and defend or leave early” approach (Handmer and Tibbits, 2005; Strahan et al., 2018). Following the catastrophic fires of 2009, policy shifted toward stronger advocacy for leaving early (Victorian Bushfires Royal Commission, 2010). Despite these changes, inquiries continue to measure disaster primarily through the number of lives lost and the scale of property damage, reinforcing the link between bushfire risk, private property and personal responsibility. Public campaigns reflect this emphasis through messages that urge Australians to prepare their family and home (Yildiz et al., 2025).

Bushfire preparedness communication in Australia continues to emphasise survival, expressed through agency slogans such as “Prepare. Act. Survive” and campaigns that urge households to complete a Bushfire Survival Plan (New South Wales Rural Fire Service, 2021). Survival here conveys the urgency of protecting life and property when fire arrives. Yet, as Harries (2017) observes, “People not only want to be safe from natural hazards; they also want to feel they are safe” (p. 1). Safety is both condition and experience, shaped through the continuity of routines and the stability that anchor everyday life. Bushfire risk exposes how that stability is formed, revealing its dependence on social, material, and ecological relations (Sims et al., 2009; Wilford, 2008). In this way, the meaning of security extends beyond survival to include the endurance of stability through which life retains order and familiarity.

The experience of bushfire risk reveals the fragility of both material and emotional stability and shows how survival and stability intertwine in everyday life. Preparedness is therefore not only a technical matter of safety but a lived condition oriented toward sustaining continuity and a sense of order amid uncertainty. This relation draws attention to how coherence and stability are maintained through disruption, a concern central to ontological security. Giddens (1991) distinguishes between “security as survival” and “security as being” (p. 92), which situates stability in both physical safety and in the continuity that renders life predictable. Research on housing and tenure also links ontological security to the psychosocial stability derived from home and dwelling continuity (Kearns et al., 2000; Hiscock et al., 2001). Disaster research has largely applied this concept to post-disaster contexts (Hawkins and Maurer, 2011; Haney and Gray-Scholz, 2020), while its significance for preparedness remains under-examined. Reid and Beilin (2015) demonstrate that, in bushfire contexts, home extends beyond four walls to include the surrounding landscape, and that education confined to property boundaries overlooks this broader sense of security (see also Easthope, 2004; Webster and Allon, 2023). Baker (2014) observes that the routines that sustain stability can also restrict adaptive capacity. More recent work extends ontological security beyond individuals and shows that stability depends on relationships with others, communities, and ecological systems (Untalan, 2020; Banham, 2020; Dale et al., 2019; Wallis et al., 2022). This paper builds on these insights by examining how renters in Hobart experience bushfire risk and preparedness. It explores preparedness as a relational and ecological condition. The analysis shows that participants experience security through connections with place, social relationships and more-than-human worlds, where stability is sustained through interdependence rather than ownership.

3 Playback theatre workshops as a community-based participatory method

Playback Theatre workshops were employed as a participatory method to explore the relational aspects of security. This method made it possible to attend to emotion and connection; elements that are often difficult to capture within the abstractions of social science research (Lockie, 2016). Through working these embodied experiences, the research aligns with a growing body of human geography scholarship that employs arts-based methods to engage alternative ways of knowing and to amplify voices that are frequently overlooked in policy and research (Archibald et al., 2024; Hawkins, 2015; Hawkins, 2018).

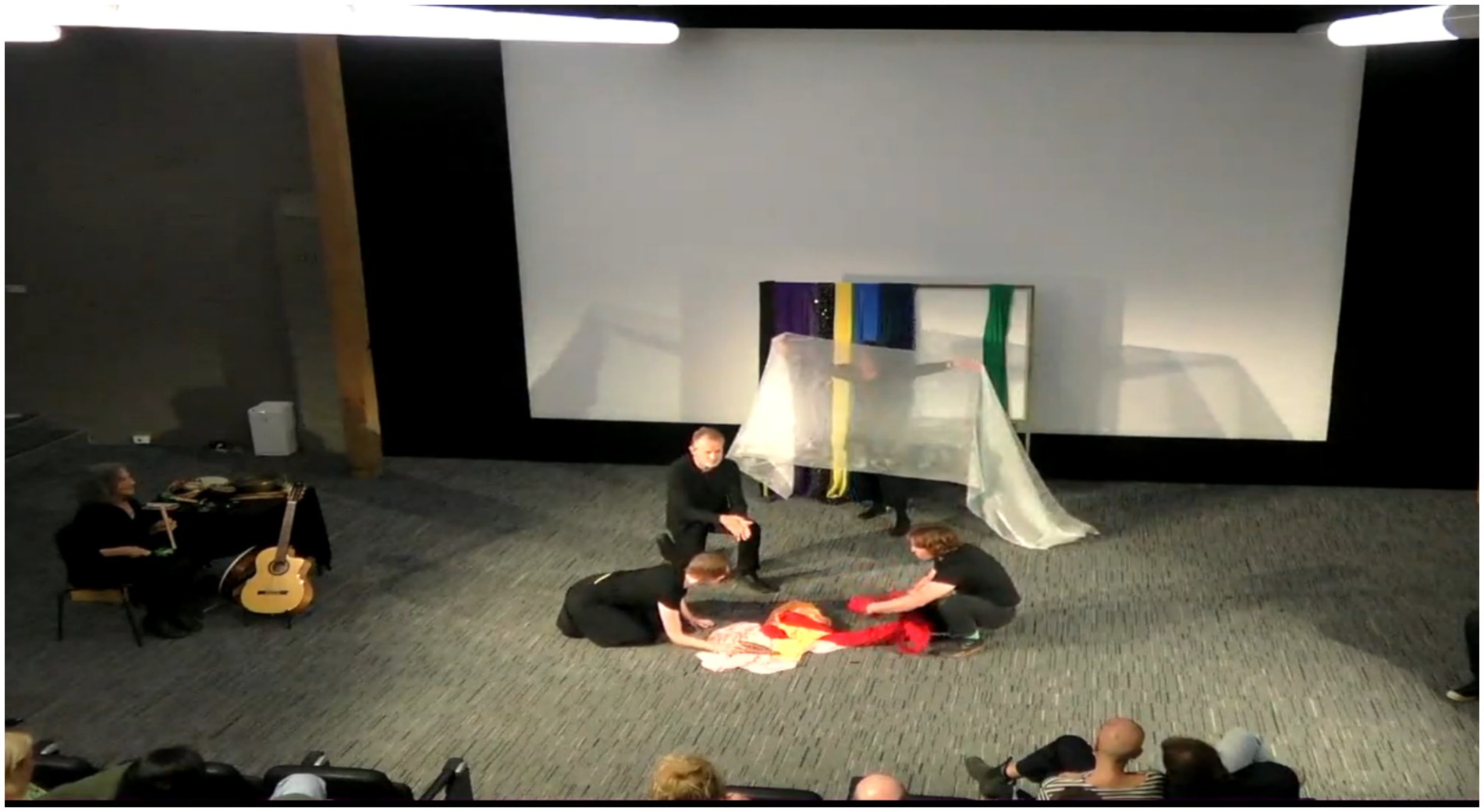

Playback Theatre is a storytelling practice that transforms personal accounts into improvised performances and produces shared meaning through embodied representation. In this study, it operated both as an art form and a research tool, with two workshops conducted in collaboration with Hobart Playback Theatre that focused on renters in the Greater Hobart region. A typical performance involves four actors, a conductor and a musician who re-enact participants’ stories in ways that emphasise their affective and relational dimensions (Chesner and Hahn, 2002; Fox and Leeder, 2018). The conductor gathers stories through prompts and dialogue, summarises them for the actors and guides the re-enactment. Through this structure, Playback produces performances that make participants’ stories tangible and open them for collective exploration.

In the workshops, the conductor acted as a bridge between participants and performers. The conductor invited personal stories through prompts and dialogue. These stories were translated into improvised performances using movement, props, music and the stage environment to create embodied representations. The performances drew participants into the sensory and emotional dimensions of their experiences. The immersive quality enabled participants to reflect on the meaning of their stories as well as on the emotions they evoked. By encountering different interpretations of their own and others’ stories, participants were encouraged to recognise connections between personal and collective experience. Playback’s emphasis on listening, storytelling and empathy (Keisari et al., 2020) also made the workshops valuable for participants navigating linguistic or cultural difference, since meaning was communicated through gesture, sound and shared performance as much as through words (Teruel and Fields, 2015).

The workshops established a setting where participants felt comfortable sharing their experiences (Keisari et al., 2020; Park-Fuller, 2003). This contrasted with the formality of interviews or focus groups. My role as researcher was limited to collaborating with the conductor to develop prompts, which helped reduce power dynamics and address positionality (Kostet, 2023; MacLean, 2013). The method, however, restricts the researcher’s influence over the interaction between conductor, actors and participants. To manage these limits, each session began with the topic of home before shifting to bushfire stories. Although only 8–9 stories could be enacted per session, post-workshop surveys captured additional reflections.

3.1 Data collection and analysis

Two Playback Theatre workshops were recorded and transcribed for analysis. After each workshop, participants completed surveys that included open-ended questions about their experience and multiple-choice questions on demographic information. The transcripts were read multiple times and codes were developed inductively. These codes were then organised in a structured codebook using Excel.

3.2 Participants

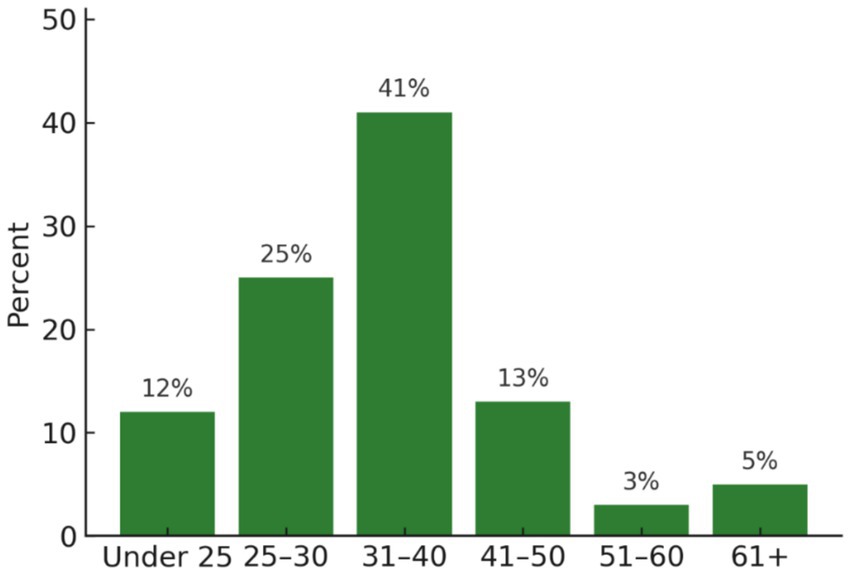

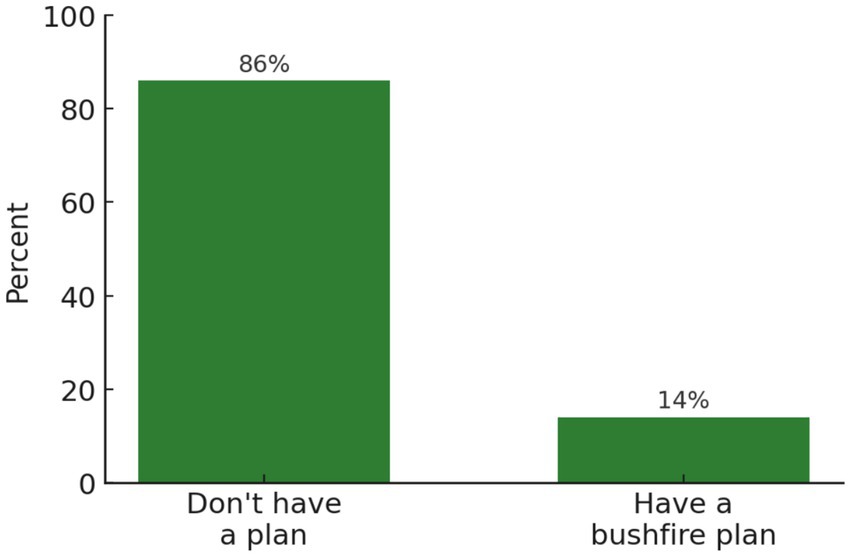

The study included 58 participants. Of these, 53% identified as female and 47% as male. Most participants were between 31 and 40 years old (41%), followed by those aged 25–30 (25%), 41–50 (13%), under 25 (12%), over 61 (5%) and 51–60 (3%) (Figure 1). Participants’ countries of origin included Afghanistan, India, Ethiopia, Chile, Lebanon, Greece, Sweden, Luxembourg, England, Canada and the United States (Figure 2). Eighty-five per cent of participants reported that they did not have a bushfire plan (Figure 3).

4 Housing, house and home: an interconnected series

The workshops began with the prompt about what home meant to participants. They described home in diverse ways to include neighbourhoods, relationships and sensory cues. Feeling at home relied on safety, the presence of loved ones and familiar environments such as the scent of gum trees or the sound the ocean. Joey captured this multiplicity when he explained: “I feel like I have many homes. One in Western Australia, one in Melbourne and now one in Hobart. The smell of the rainforest in Western Australia, or I smell coffee in Melbourne all makes me feel at home.” His story demonstrated how sensory cues carried home across different places through memory (Figure 4).

Some participants described home in relation to property and its absence. Max, reflecting on lifelong renting, said: “I have no house, but home is a different concept. Relating to bushfires, it was interesting to not hear anyone talk about property. I feel that would be very different to homeowners.” Georgia reinforced this point by noting that the workshops recognised renters’ experiences of bushfire threat when “it’s not just about losing a house/property but the intangible things that are lost, like a sense of home.” These reflections showed that what was at stake often centred on attachments and meanings that could not be reduced to the dwelling itself (Bate, 2018; Winter, 1994).

Bushfires unsettled participants’ sense of home when their familiar surroundings came under threat. Emerson recalled the 2018/19 fires in Tinderbox, where smoke was so thick it obscured the road and the water and the experience created a strong sense of apprehension: “I wasn’t worried about the rental I was living in, I did not have a big attachment to it, but to see everything around it burnt down, it’s very different.”

Sandy offered a similar experience during the 2019 bushfires in Tasmania (Figure 5). From his office at the Wilderness Society building in Hobart, he watched smoke spread across Kunanyi and across the hills. What struck him most was the stream of people in their forties to sixties who came in with tears in their eyes, concerned that fires were about to enter the Weld Valley1 and other places they knew intimately as bushwalkers and conservationists. Many of these landscapes had been protected through campaigns in their youth and now faced the possibility of burning.

Figure 5. Enactment of the 2018–2019 Tinderbox bushfires. The white cloth symbolises fog, while the other cloths represent flames.

For some participants, home was tied to practices of care that bushfires put under strain. Colin, a wildlife carer, recalled carrying possums down the mountain to his rental: “there was this element of, like, losing habitat and homes for all these things… millions out there. But then also this sense of, like, what’s the point of trying to protect all these places if they are just going to burn down?” When he later moved to a different rental property, his landlord prohibited wildlife care. That restriction severed an attachment that had once shaped his willingness to act during bushfires. He reflected that the absence of wildlife care made bushfire feel “less of an emotional thing.” When the conductor asked for a title, Colin responded with a question: “Where does the possum go?” (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Enactment of “Where does the possum go?.” The green cloth was used to symbolise Kunanyi and local wildlife, while the red cloth represented the bushfire. Sandy’s perspective was conveyed through the man on the left, shown holding an injured possum.

4.1 Tenure and preparedness

The workshops also prompted reflection on how tenure shapes bushfire preparedness. Several participants noted that they had not made this connection before. Hayley remarked, “It seems most renters, like, they have less to lose? Not too sure.” This sense of uncertainty echoed across the group, with many renters unsure of their position in preparedness. Survey results reinforced this: 85% of participants reported lacking a bushfire plan, consistent with Campbell et al.’s (2024) finding that renters are generally less prepared than households with secure tenure.

Some stories described preparedness as a shared responsibility rooted in land and community, rather than reduced to property or an individual plan. Sally reflected: “Yes! It provided a good opportunity to reflect and do some deep thinking about place, home, country and whether there is actually any difference at all between landowners and renters. We all are afforded the great privilege to be lucky enough to be custodians of the land.” Her perspective reoriented preparedness away from private property and toward collective care for community and ecosystems.

Other stories emphasised the constraints of renting. Kelly explained: “Would also be great to know some next stages about where or how renters could be better prepared, how do we talk to our rental agencies about huge broad scale issues when they will not even pay attention to our messages, calls and attempts to fix very real, unmet problems like the toilet, plumbing, the windows…? I feel like any concerns about bushfire will be ignored!” Her frustration highlights two obstacles: landlords who neglect basic maintenance and tenants’ lack of authority to make safety improvements. These insights set the stage for the theoretical discussion that follows, which interprets these stories through the lenses of ontological security and disaster justice.

5 Discussion

The following discussion interprets the findings in relation to Australian bushfire preparedness governance and communication and considers what they reveal about security and justice. Renters described bushfire risk as unsettling the relationships that made daily life feel stable and continuous. The dwelling formed part of this order yet held less significance than the ties that sustained coherence and meaning. These relations, expressed through ordinary routines, attachments, and responsibilities, formed the basis of ontological security in the context of bushfire risk (Reid and Beilin, 2015; Banham, 2020; Untalan, 2020). They show a search for security in the continuities of relationship and routine, a search that shaped how preparation itself was imagined (Reid and Beilin, 2015; Banham, 2020; Untalan, 2020). Table 1 summarises how these relations were expressed in practice and provides the grounding for examining how official preparedness discourse recognises or overlooks such conditions.

Table 1. Relations that sustain and disrupt ontological security in renters’ experiences of bushfire risk.

Preparedness in Australia remains governed by regulatory and communicative conventions that position property as the reference point for personal security. Official inquiries and strategic documents record bushfire impacts primarily through lives lost and houses destroyed (Victorian Bushfires Royal Commission, 2010; Council of Australian Governments, 2011). Physical survival forms the baseline of safety, a concern shared by all households. Beyond immediate survival, preparedness discourse defines security through the protection of houses and possessions.

Renters described security as taking shape through responsibilities to others, attachment to familiar landscapes, and the routines that held life steady. These attachments maintained continuity in ways that official measures of loss rarely recognise. Because bushfire preparedness has been defined through how loss and recovery are counted, it has also determined which forms of security are considered legitimate. Renters’ perspectives expand this definition, showing that preparedness can be understood through the ways people sustain stability and belonging in everyday life. Such an understanding points toward collective forms of readiness, grounded in relationships and the continuities that keep life steady amid uncertainty.

These insights have direct implications for how preparedness is communicated. Clear and direct information remains essential, yet its effectiveness depends on whether it resonates with the ways people sustain stability in their lives. For renters, advice that assumes property control overlooks their circumstances and obscures the concerns they identified: ties to place, ecological attachments, and community roles. When guidance fails to connect with these relations, structural barriers such as landlords’ neglect and restrictions on modifying dwellings become even more limiting (Collins, 2008; McDonald and McCormack, 2022; Campbell et al., 2024). A disaster justice perspective emphasises that preparedness communication must support readiness in both its material and lived dimensions, recognising that security is shared, relational, and unevenly supported across housing conditions.

6 Conclusion

This study identifies several categories through which renters perceive and engage with bushfire risk: tenure-contingent relations, sensory markers that anchor home in perception, ecological ties sustained through more-than-human relations and community attachments. These categories show that ontological security rests on the assurance of continuity in everyday life; the sense of coherence and belonging sustained through people, place and ecological relations. Bushfire risk was therefore experienced as a threat not only to physical assets but also to the lived attachments that give stability and meaning. Renters’ accounts point to ways of reimagining preparedness in terms that matter to them, even when authority to act is limited.

The perspectives presented here are not representative of all renters, nor do they suggest that every tenant experiences security through the same anchors. What they do show is that renters can draw on varied sources of stability. Many tenants live in properties for short periods, move frequently or experience home through mobility rather than sustained ties to place or community. Housing precarity and insecure tenure can disrupt the formation of continuities described in this study. Acknowledging this variation reinforces the significance of the findings, since it shows how uneven access to stability changes ways of seeking security and shapes preparedness. From a disaster justice perspective, this unevenness is itself important: it highlights the need to recognise both the continuities that sustain security and the conditions that deny them.

These insights extend, rather than replace, the practical messages of bushfire readiness. They suggest that bushfire readiness depends on recognising both the tangible and the intangible, on defending shelter as well as the sense of home. Attending to these conditions can make preparedness more relevant to renters, who often lack the authority to modify their dwellings and thus experience generic advice as distant from their circumstances. If these perspectives are incorporated, bushfire preparedness communication can advance disaster justice and extend its scope to include forms of security long overlooked in the lives of renters and across other walks of life.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the University of Tasmania Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

DY: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research funded by the Australian Research Council: Special Research Initiatives: SR200200441.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^The Weld Valley is in southern Tasmania, part of Tasmania’s southern forests, near the Southwest World Heritage Area.

References

Anderson, W. A., and Whitman, R. G. (1967). A few preliminary observations on “black Tuesday”: the February 7, 1967 fires in Tasmania, Australia. Mass Emerg. 2, 181–187.

Archibald, M. M., Makinde, S., and Tongo, N. (2024). Arts-based approaches to priority setting: current applications and future possibilities. Int J Qual Methods 23, 1–11. doi: 10.1177/16094069231223926

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2022a). Snapshot of Australia, 2021. Canberra, Australia: Author. Available online at: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/people-and-communities/snapshot-australia/latest-release (Accessed October 15, 2024).

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2022b). 2021 Hobart, census all persons QuickStats [local government area: LGA62810]. Available online at: https://abs.gov.au/census/find-census-data/quickstats/2021/LGA62810 (Accessed October 15, 2024).

Australian Government Treasury (2020) Retirement income review. Canberra: Australian Government. Available online at: https://treasury.gov.au/publication/p2020-100554 (Accessed October 15, 2024).

Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute. (2019). Australian home ownership: past reflections, future directions (final report no. 328). AHURI. Available online at: https://www.ahuri.edu.au/sites/default/files/migration/documents/AHURI-Final-Report-328-Australian-home-ownership-past-reflections-future-directions.pdf (Accessed October 15, 2024).

Baker, N. D. (2014). “Everything always works”: continuity as a source of disaster preparedness problems. Int. J. Mass Emerg. Disasters 32, 428–458. doi: 10.1177/028072701403200302

Banham, R. (2020). Emotion, vulnerability, ontology: operationalising “ontological security” for qualitative environmental sociology. Environ. Sociol. 6, 132–142. doi: 10.1080/23251042.2020.1717098

Bate, B. (2018). Understanding the influence tenure has on meanings of home and homemaking practices. Geogr. Compass 12, 1–15. doi: 10.1111/gec3.12354

Beeson, M., and Firth, A. (1998). Neoliberalism as a political rationality: Australian public policy since the 1980s. J. Sociol. 34, 215–231. doi: 10.1177/144078339803400301

Beringer, J. (2000). Community fire safety at the urban rural interface: the bushfire risk. Fire Saf. J. 35, 1–23. doi: 10.1016/S0379-7112(00)00014-X

Blake, D., Marlowe, J., and Johnston, D. (2017). Get prepared: discourse for the privileged? Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 25, 283–288. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2017.09.012

Booth, K., Davison, A., and Hulse, K. (2022). Insurantial imaginaries: some implications for home-owning democracies. Geoforum 136, 46–53. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2022.08.009

Bushfire CRC (2009) Victorian 2009 bushfire research response final report. (October).Available online at: https://www.bushfirecrc.com/sites/default/files/managed/resource/victorian-2009-bushfire-research-response-report-_-overview.pdf (Accessed November 12, 2024).

Campbell, S. L., Williamson, G. J., Johnston, F. H., and Bowman, D. M. (2024). Archetypes and change in wildfire risk perceptions, behaviours and intentions among adults in Tasmania, Australia. Int. J. Wildland Fire 33:24105. doi: 10.1071/WF24105

Chesner, A., and Hahn, H. (2002). Creative advances in Groupwork. London and New York: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

City of Hobart (2022). Bushfire management strategy 2022: A plan for the future. City of Hobart. Available online at: https://www.hobartcity.com.au/files/assets/public/v/2/council/strategies-plans-and-reports/bushfire-management-strategy-2022.pdf (Accessed November 12, 2024).

Clark, W. A. V. (2013). The aftermath of the general crisis for the ownership society: what happened to low-income owners in the US? Int. J. Hous. Policy 13, 227–246. doi: 10.1080/14616718.2013.796811

Collins, T. (2008). What influences hazard mitigation? Household decision making about wildfire risks in Arizona’s White Mountains. Prof. Geogr. 60, 508–526. doi: 10.1080/00330120802211737

Council of Australian Governments (2011) ‘National Strategy for disaster resilience: building the resilience of our nation to disasters.’ (February), p. 25. Available online at: https://www.ag.gov.au/EmergencyManagement/Documents/NationalStrategyforDisasterResilience.PDF (Accessed November 12, 2024).

Crabtree, L. (2016). Unbounding home ownership in Australia. In N. Cook, A. Davison, & L. Crabtree (Eds.), Housing and home unbound: Intersections in economics, environment and politics in Australia. Routledge. 173–189.

Crosweller, M., and Tschakert, P. (2021). Disaster management and the need for a reinstated social contract of shared responsibility. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 63:102440. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2021.102440

Dale, B., Veland, S., and Hansen, A. M. (2019). Petroleum as a challenge to arctic societies: ontological security and the oil-driven “push to the north”. Extr. Ind. Soc. 6, 367–377. doi: 10.1016/j.exis.2018.10.002

Davison, A. (2006). Stuck in a cul-de-sac? Suburban history and urban sustainability in Australia. Urban Policy Res. 24, 201–216. doi: 10.1080/08111140600704137

Donoghue, J. (2010). Citizenship, civic engagement and property ownership. Aust. J. Soc. Issues 45, 365–381. doi: 10.1002/j.1839-4655.2010.tb00181.x

Dundon, L. A., and Camp, J. (2021). Climate justice and home-buyout programs: renters as a forgotten population in managed retreat actions. J. Environ. Stud. Sci. 11, 420–433. doi: 10.1007/s13412-021-00691-4

Dupuis, A., and Thorns, D. C. (1998). Home, home ownership and the search for ontological security. The Sociological Review. London: SAGE Publications. 46, 24–47.

Easthope, H. (2004). A place called home. Hous. Theory Soc. 21, 128–138. doi: 10.1080/14036090410021360

Forrest, R., and Hirayama, Y. (2015). The financialisation of the social project: embedded liberalism, neoliberalism and home ownership. Urban Stud. 52, 233–244. doi: 10.1177/0042098014528394

Fox, H., and Leeder, A. (2018). Combining theatre of the oppressed, playback theatre, and autobiographical theatre for social action in higher education. Theatre Top. 28, 101–111. doi: 10.1353/tt.2018.0019

Gamble, A., and Prabhakar, R. (2005). Assets and poverty. ESRC end of award report, RES-000– 23–0053, nominated output 2.

Gill, A. M. (2005). Landscape fires as social disasters: an overview of ‘the bushfire problem’. Environ. Hazards 6, 65–80. doi: 10.1016/j.hazards.2005.10.005

Handmer, J., and Tibbits, A. (2005). Is staying at home the safest option during bushfires? Historical evidence for an Australian approach. Glob. Environ. Change B. Environ. Hazard 6, 81–91. doi: 10.1016/j.hazards.2005.10.006

Haney, T. J., and Gray-Scholz, D. (2020). Flooding and the “new normal”: what is the role of gender in experiences of post-disaster ontological security? Disasters 44, 262–284. doi: 10.1111/disa.12372

Harries, T. (2017). “Ontological security and natural” in HazardsOxford research encyclopedia of natural Hazard science, 1–22.

Hawkins, H. (2015). Creative geographic methods: knowing, representing, intervening. On composing place and page. Cult. Geogr. 22, 247–268. doi: 10.1177/1474474015569995

Hawkins, H. (2018). Geography’s creative (re)turn: toward a critical framework. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 43, 963–984. doi: 10.1177/0309132518804341

Hawkins, R. L., and Maurer, K. (2011). “You fix my community, you have fixed my life”: the disruption and rebuilding of ontological security in New Orleans. Disasters 35, 143–159. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7717.2010.01197.x

Higgins, V. (2014). Australia’s developmental trajectory: neoliberal or not? Dialogues Hum. Geogr. 4, 161–164. doi: 10.1177/2043820614536501

Hiscock, R., Kearns, A., Macintyre, S., and Ellaway, A. (2001). Ontological security and psycho-social benefits from the home: qualitative evidence on issues of tenure. Hous. Theory Soc. 18, 50–66. doi: 10.1080/14036090120617

Hulse, K., Morris, A., and Pawson, H. (2019). Private renting in a home-owning society: disaster, diversity or deviance? Hous. Theory Soc. 36, 167–188. doi: 10.1080/14036096.2018.1467964

Hulse, K., and Saugeres, L. (2008). Housing insecurity and precarious living: an Australian exploration (final report no. 124) Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Available online at: https://www.ahuri.edu.au/research/final-reports/124 (Accessed January 4, 2025).

Jones, M. W., Kelley, D. I., Burton, C. A., Di Giuseppe, F, Barbosa, M. L. F., Brambleby, E, et al. (2024). State of wildfires 2023–2024. Earth System Science Data 16:3601–3646. doi: 10.5194/essd-16-3601-2024

Kearns, A., Hiscock, R., and Ellaway, A. (2000). “Beyond four walls”. The psycho-social benefits of home: evidence from west Central Scotland. Hous. Stud. 15, 387–410. doi: 10.1080/02673030050009249

Keisari, S., Gesser-Edelsburg, A., Yaniv, D., and Palgi, Y. (2020). Playback theatre in adult day centers: a creative group intervention for community-dwelling older adults. PLoS One 15:e0239812. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0239812

Koksal, K., McLennan, J., and Bearman, C. (2020). Living with bushfires on the urban-bush interface. Aust. J. Emerg. Manag. 35, 21–28. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/339004646_Living_with_bushfires_on_the_urban-bush_interface

Kostet, I. (2023). Shifting power dynamics in interviews with children: a minority ethnic, working-class researcher’s reflections. Qual. Res. 23, 451–466. doi: 10.1177/14687941211034726

Lambrou, N., Kolden, C., Loukaitou-Sideris, A., Anjum, E., and Acey, C. (2023). Social drivers of vulnerability to wildfire disasters: a review of the literature. Landsc. Urban Plan. 237:104797. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2023.104797

Li, L., Xu, C., Huang, L., and Zhou, Q. (2024). Global expansion of wildland-urban interface intensifies human exposure to wildfire risk in the 21st century. Sci. Adv. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.ado9587

Lockie, S. (2016). The emotional enterprise of environmental sociology. Environ. Sociol. 2, 233–237. doi: 10.1080/23251042.2016.1237794

Lucas, C., Williamson, G. J., and Bowman, D. M. J. S. (2022). Neighbourhood bushfire hazard, community risk perception and preparedness in peri-urban Hobart, Australia. Int. J. Wildland Fire 31, 1129–1143. doi: 10.1071/WF22099

MacLean, L. (2013). “The power of the interviewer” in Interview research in political science. ed. L. Mosley (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press), 67–83.

McCarthy, S., and Friedman, S. (2023). Disaster preparedness and housing tenure: how do subsidized renters fare? Hous. Policy Debate 33, 1100–1123. doi: 10.1080/10511482.2023.2224309

McDonald, J., and McCormack, P. C. (2022). Responsibility and risk-sharing in climate adaptation: a case study of bushfire risk in Australia. Clim. Law. 12, 128–161. doi: 10.1163/18786561-20210003

McLennan, B., and Handmer, J. (2014). Sharing responsibility in Australian disaster management: Final report for the sharing responsibility project. Melbourne.

National Emergency Management Agency. (2024). Enhancing long-term preparedness for Hobart. NEMA. Available online at: https://www.nema.gov.au/about-us/media-centre/enhancing-long-term-preparedness-hobart (Accessed January 4, 2025).

National Housing Supply and Affordability Council (2024). State of the housing system 2024. Available online at: https://nhsac.gov.au/sites/nhsac.gov.au/files/2024-05/state-of-the-housing-system-2024.pdf (Accessed January 4, 2025).

New South Wales Rural Fire Service. (2021). Annual report 2021/22. New South Wales government. Available online at: https://www.rfs.nsw.gov.au/about-us/publications/annual-reports (Accessed September 7, 2024).

Ondei, S., Price, O. F., and Bowman, D. M. J. S. (2024). Garden design can reduce wildfire risk and drive more sustainable co-existence with wildfire. Nat. Hazards 1:18. doi: 10.1038/s44304-024-00012-z

Park-Fuller, L. M. (2003). Audiencing the audience: playback theatre, performative writing, and social activism. Text Perform. Q. 23, 288–310. doi: 10.1080/10462930310001635321

Parliamentary Library (2025). Implications of declining home ownership. Issues & insights. Parliament of Australia. Available online at: https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_departments/Parliamentary_Library/Research/Issues_and_Insights/48th_Parliament/Implicationsofdeclininghomeownership (Accessed May 10, 2025).

Pawson, H., Milligan, V., and Yates, J. (2019). Housing policy in Australia. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan.

Reid, K., and Beilin, R. (2015). Making the landscape “home”: narratives of bushfire and place in Australia. Geoforum 58, 95–103. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2014.10.005

Rivera, J. D. (2020). The likelihood of having a household emergency plan: understanding factors in the US context. Nat. Hazards 104, 1331–1343. doi: 10.1007/s11069-020-04217-z

Sims, R., Medd, W., Mort, M., and Twigger-Ross, C. (2009). When a “home” becomes a “house”: care and caring in the flood recovery process. Space Cult. 12, 303–316. doi: 10.1177/1206331209337077

Solangaarachchi, D., Griffin, A. L., and Doherty, M. D. (2012). Social vulnerability in the context of bushfire risk at the urban-bush interface in Sydney: a case study of the Blue Mountains and Ku-ring-gai local council areas. Nat. Hazards 64, 1873–1898. doi: 10.1007/s11069-012-0334-y

Stonehouse, D., Threlkeld, G., and Farmer, J. (2015). Housing risk’ and the neoliberal discourse of responsibilisation in Victoria. Crit. Soc. Policy 35, 393–413. doi: 10.1177/0261018315588232

Strahan, K., Whittaker, J., and Handmer, J. (2018). Self-evacuation archetypes in Australian bushfire. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 27, 307–316. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2017.03.013

Teruel, T. M., and Fields, D. L. (2015). Playback theatre: Embodying the CLIL methodology In Drama and CLIL: A new challenge for the teaching approaches in bilingual education. eds. S. N. Román and J. J. T. Núñez (Bern, Switzerland: Peter Lang AG, International Academic Publishers), 194, 47–75.

Untalan, C. Y. (2020). Decentering the self, seeing like the other: toward a postcolonial approach to ontological security. Int. Political Sociol. 14, 40–56. doi: 10.1093/ips/olz018

Verchick, R. (2012). Disaster justice: the geography of human capability. Duke Environ. Law Policy Forum 23, 23–71. Available online at: https://scholarship.law.duke.edu/delpf/vol23/iss1/2

Verrender, I. (2024) Will the Housing Affordability Crisis Eat Us up?, ABC News. Available online at: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2024-04-09/affordable-housing-home-ownership-rental-market-property-crisis/103681192 (Accessed October 15, 2024).

Victorian Bushfires Royal Commission (2010). Victoria’s bushfire safety policy (final report Vol. II). Government of Victoria. Available online at: https://royalcommission.vic.gov.au/Commission-Reports/Final-Report/Volume-2/Chapters/Victoria-s-Bushfire-Safety-Policy.html (Accessed October 15, 2024).

Wallis, A., Fischer, R., and Abrahamse, W. (2022). Place attachment and disaster preparedness: examining the role of place scale and preparedness type. Environ. Behav. 54, 670–711. doi: 10.1177/00139165211064196

Webster, S., and Allon, F. (2023). Domus, dream, Domicide: home as limit point in the Pyrocene lessons from the “black summer” Australian bushfires. Aust. Fem. Stud. 37, 242–258. doi: 10.1080/08164649.2023.2177829

Weller, S., and O’Neill, P. (2014). An argument with neoliberalism: Australia’s place in a global imaginary. Dialogues Hum. Geogr. 4, 105–130. doi: 10.1177/2043820614536334

Wilford, J. (2008). Out of rubble: natural disaster and the materiality of the house. Environ. Plan. D Soc. Space 26, 647–662. doi: 10.1068/d4207

Winter, I. C. (1994). “The meanings of housing tenure” in The radical homeowner. ed. I. Winter (London: Routledge), 69–92.

Wisner, B., Gaillard, J. C., and Kelman, I. (2012). The Routledge handbook of hazards and disaster risk reduction. New York: Routledge.

Keywords: disaster justice, renters, bushfire risk, ontological security, bushfire preparedness, disaster risk reduction

Citation: Yildiz D (2025) What’s to lose? A sensuous geography of renters’ bushfire experiences in Australia. Front. Commun. 10:1534572. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2025.1534572

Edited by:

Bruno Takahashi, Michigan State University, United StatesReviewed by:

Annelie Sjölander Lindqvist, University of Gothenburg, SwedenVoltaire Alvarado Peterson, University of Concepcion, Chile

Copyright © 2025 Yildiz. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Deniz Yildiz, ZGVuaXoueWlsZGl6QHV0YXMuZWR1LmF1

Deniz Yildiz

Deniz Yildiz