- 1Division of Emerging Media Studies, College of Communication, Boston University, Boston, MA, United States

- 2The Center for Excellence in Social Sciences, University of Warsaw, Warsaw, Poland

Introduction: This study explores motivations for the use of video games in coping, using the twin theoretical lenses of mood management and stress response theory, as well as how individual differences in motivational orientation moderate emotional regulation. The role of genres in selective exposure and the extent to which this overlaps with individual motivations for play are also addressed.

Methods: An exploratory survey (N = 348) was conducted to gather data on respondents’ personalities, gameplay habits, motivations, genre preferences, coping strategies, and emotional states.

Results: Gameplay as coping was found to be quite widespread, and associations were found between this behavior and respondents’ motivations for gaming in general, as well as with individual differences related to immersion. Motivational orientations towards narrative involvement, social interaction, and escapism were likewise associated with using games to cope with stress, while the regulatory effects of gameplay were also found to be moderated by players’ orientation towards autonomy and exploration.

Discussion: These findings suggest that individual differences in immersive tendencies and motivational orientations play a crucial role in determining when and how video games serve as effective tools for emotional regulation and coping with stress.

1 Introduction

The popularity of video games has often been articulated in terms of their unique motivational “pull,” and the features of the medium that drive this motivation have been the subject of much scholarly work (Ryan et al., 2006; Przybylski et al., 2010). It is generally understood that video games fulfill some set of psychological needs for their players, and that this makes the experience of play pleasurable (Tamborini et al., 2011). It is less clear how games affect players’ well-being, as scholars have identified both beneficial and detrimental correlates of gameplay habits (Granic et al., 2014; Pallavicini et al., 2018; Pine et al., 2020). The present study supposes that, alongside fun and enjoyment, a desire to support emotional well-being may be one of the factors motivating individuals to play video games and explores how the motivational aspects of the medium relate to its use for the purposes of emotional regulation and coping with stress. Emotional well-being, in this context, refers to the balancing of positive and negative affect, as well as the effective regulation of emotional arousal (Fredrickson and Joiner, 2002; Brockman et al., 2017; Oravecz and Brick, 2019).

1.1 Mood management and stress response

Mood management theory (MMT) accounts for the selection of mediated experiences by arguing that individuals are motivated in their behavior by a desire to experience pleasurable emotional states and to ameliorate negative ones (Bryant and Zillmann, 1984; Zillmann, 2000). On this basis, mood—defined as a relatively stable emotional state that operates in the background of experience and not in direct response to any single stimulus—and selected media experiences are conceptualized as elements in a self-regulating control system or feedback loop (Larsen, 2000). Undesirable mood states are predicted to lead to an emotion-regulatory response, involving the selection of media that will aid in the restoration of a more desirable mood state, whether by alleviating the cause of the negative mood or by providing a counterbalancing positive stimulus. Notably, this theoretical framework has been frequently invoked in the past to account for the appeal of video games as a general category of media activity (Bowman and Tamborini, 2012, 2015; Reinecke et al., 2012); however, the emotional regulation dynamics that lead to the selection of one game over another are significantly less well understood (Villani et al., 2018).

The process of coping with stress is closely related to emotional regulation and MMT, in that it also articulates a response motivated by a negative emotional state; however, the theoretical literature has remained strikingly divided between these two approaches, particularly on the uses of media (Wolfers and Schneider, 2020). Stress is typically theorized as a two-step process, whereby an individual first recognizes a potential threat to their goals or well-being and then evaluates their available psychological and instrumental resources for mounting a response (Lazarus and Folkman, 1984). More recent iterations of stress response theory tend to see this as a cyclical process of reappraisal and adaptive response (Smith and Lazarus, 1990), not dissimilar to MMT. Coping with stress has likewise been frequently identified as a motivating factor for video gameplay (Reinecke, 2009; Iacovides and Mekler, 2019; Cahill, 2021), although theories of coping have tended to take a dimmer view of media use on the whole, often reflexively framing it in terms of distraction or avoidance (Nabi et al., 2017).

1.2 Recovery and resilience

This view of media use as primarily oriented towards short-term hedonic needs, such as emotional avoidance or mood repair, is challenged by emerging perspectives that suggest the potential of entertainment media in general and interactive entertainment media in particular for supporting both short-term recovery and long-term resilience building. The Recovery and Resilience in Entertainment Media Use (R2EM) Model proposed by Reinecke and Rieger (2021) offers a comprehensive theoretical framework encompassing both of these elements: it incorporates hedonic motivations for engagement with entertainment media content that serve immediate needs of allostatic regulation and mood repair alongside eudaimonic motivations oriented towards personal growth and the development of psychological resilience through encounters with content that is cognitively and/or emotionally challenging, providing opportunities for meaning-making.

This more inclusive conceptualization aligns with empirical evidence suggesting that motivations for playing video games frequently extend beyond simple mood optimization into more eudaimonic domains (Bowman et al., 2024; Possler et al., 2024). Eudaimonic experiences are characterized by mixed affect—that is, by the simultaneous experience of positive and negative affective states—and a desire to seek deeper meaning, emotional engagement, or truth about oneself or the world (Oliver and Raney, 2011). There are numerous aspects of video games as a medium that may contribute to their potential for providing eudaimonic experiences to players, including the ability for players to exert agency over the narrative and make meaningful choices, the potential that this agency creates for introspection as players are prone to identify more strongly with the characters they control, the pairing of emotional engagement and cognitive demand, and in some games, the opportunity to interact and collaborate with other human players (Oliver et al., 2015; Daneels et al., 2021). Such eudaimonic play experiences may be particularly relevant when individuals use games to cope with significant life stressors, as research suggests that the ability to approach and engage with complex emotions in such circumstances (i.e., emotional approach coping) is frequently a predictor of positive long-term outcomes in terms of mental and physical health (Austenfeld and Stanton, 2004; Juth et al., 2015).

1.3 Immersive tendencies

Despite the growing recognition of gaming as a common means of coping with stress, a critical gap remains in the present understanding of the individual and situational factors that may affect this process. Much of the extant research literature treats gaming as a relatively monolithic activity and fails to account for the vast diversity of player motivations and gaming experiences within the medium (Dale and Green, 2017; Dale et al., 2020). Without understanding how these individual differences affect both the propensity to use games for coping and the efficacy of such use, it will remain difficult to adequately explain the mechanisms through which games may support or undermine emotional well-being. Moreover, this limitation constrains our ability to differentiate the circumstances under which gaming may serve as an effective response to stress from those under which gaming is potentially maladaptive.

Prior research has identified immersive tendencies—that is, the propensity to become involved and immersed in mediated experiences—as a meaningful predictor of the likelihood that an individual will play games to cope with stress (Cahill, 2021). However, this association has thus far been observed in a single exploratory study and therefore warrants further empirical testing. This observation is situated within a broader theoretical gap in our understanding of the ways in which individual differences and personality traits shape both selective exposure to game content under conditions of stress and the efficacy of game-based coping. While the role of individual differences and personality traits in media selection as part of mood management has been long-established across various contexts (Zillmann, 2000; Oliver, 2003; Luong and Knobloch-Westerwick, 2021), and individual preferences have likewise been studied with respect to game selection (Hartmann and Klimmt, 2006; Park et al., 2011; Braun et al., 2016), these two streams of research have yet to be integrated with one another in the context of gameplay that occurs in response to stress. Immersive tendencies represent a particularly relevant personality trait in this context, as individuals with a greater propensity towards immersion may find the fulfillment of certain emotional needs through gameplay more accessible (Tamborini et al., 2011). Therefore, we propose:

H1: The use of video games to cope with stress will be positively associated with individual differences in immersive tendencies.

1.4 Gaming motivations

Both MMT and stress response theory identify a connection between emotional and motivational processes: individuals are imagined to be driven in their actions—at least in part—by their emotional needs. These actions are also informed by the conditioned and individualized appraisal of the efficacy of similar actions in the past, such that individuals are likely to select media experiences for coping or emotional regulation on the basis of their individual experience (Smith and Lazarus, 1990; Zillmann, 2000; Klimmt and Hartmann, 2006). It has also been theorized that individuals’ appraisal of their own motivations for media use may moderate the emotional effects they subsequently experience: Reinecke et al. (2014) observed, for instance, that feelings of guilt experienced in relation to playing video games or watching television significantly attenuated both enjoyment of the experience and resulting ego recovery.

Motivations for playing games have been extensively theorized, and scholarship in this area builds on a variety of frameworks, most notably self-determination theory (Ryan et al., 2006), uses and gratifications theory (Jansz et al., 2010), and social cognitive theory (De Grove et al., 2016). Early approaches to this work tended to emphasize the identification of player types (Hamari and Tuunanen, 2014), influenced by Bartle’s (1996) typologizing of MUD players into achievers, explorers, socializers, and killers; these four categories were an extension of two dimensions of “playing style” theorized by Bartle, which contrasted world-oriented against player-oriented play and action against interaction. While this typological approach was influential, subsequent research has tended to focus more on developing more nuanced multidimensional models of player motivation that reflect the likelihood of multiple intersecting and interacting motivations for play (Király et al., 2022; Holl et al., 2024).

Given the interactive nature of video games, the staggeringly wide range of gameplay experiences possible within the medium, and the degree to which an individual’s experience is determined both by the choice of game and their choices within the game, we theorize that motivations for play will intervene in the use of games for coping and emotional regulation. The particular aspects of gameplay experiences that a player finds compelling (i.e., their motivations for play) may be predicted to influence both their likelihood of selecting one such experience in response to an undesirable emotional state, as well as the consequences of that choice. This would be consistent with the findings of prior studies that link both physical and mental health outcomes of gaming to player motivations (Comello et al., 2016; Kaczmarek et al., 2017; Sauter et al., 2021).

RQ1: How is the propensity to cope with stress through video games affected by the player’s motivations for play?

RQ2: How are the outcomes of coping with stress through video games affected by the player’s motivations for play?

Iacovides and Mekler’s (2019) qualitative study of gaming during difficult life experiences offers some hints as to what motivations might relate most strongly to coping behaviors: involvement with game narratives and social connections with other players both figure prominently in the accounts of their participants. Gaming also offers an escape from the stressful conditions of reality, which may offer either needed, temporary respite or lead to maladaptive disengagement, wherein individuals avoid stressors in a persistent way that allows those stressors to become exacerbated and which ultimately leads to non-beneficial outcomes (Bowditch et al., 2018; Plante et al., 2018). Alternatively, video games may function as a space where the player can experience a sense of autonomy or freedom that is absent from their day-to-day lives (Tamborini et al., 2011; Reinecke et al., 2012).

1.5 Preferred gameplay genres

On a related note, we should consider the role of genre in the selective exposure process implicated by MMT. While not central to their study, Bowman and Tamborini (2012) touch upon the fact that genre is generally predictive of the tone and affect of a given piece of media, and may therefore be used by individuals to estimate the effect it will have on their mood state. In addition to these aesthetic distinctions, the mechanical affordances of different game genres are such that they have been observed to have significantly different effects on cognitive function and brain structure (Denilson et al., 2019; Dale et al., 2020). Given the bodies of research tying games to well-being and game genre to cognition, it is surprising how little empirical research has been conducted on the relationships of genre and emotion (Pallavicini et al., 2018). In the context of the present study, we will begin to integrate game genre into the MMT and stress response frameworks by exploring the effect of genre preference on the self-identified use and selection of games in coping behavior.

RQ3: How is the propensity to cope with stress through video games affected by the genre of the games played?

1.6 Displacement effects

There is also the question of whether using games to regulate emotions or cope with stress has the potential to detract from available time and attentional resources that might otherwise be allocated to more productive activities. This possibility parallels Putnam’s (2000) well-known displacement hypothesis that time spent on media consumption has taken time away from social interaction. Similar offsets have been proposed between media use and other activities, such as physical activity and civic engagement, although empirical support for the hypothesis has been mixed (Moy et al., 1999; Mannell et al., 2013). MMT also frequently frames selective exposure to media in terms of allocation of a limited quantity of time, energy, or attention (Knobloch-Westerwick, 2007; Rieger et al., 2014a); in contrast, stress response approaches tend to emphasize the flexible deployment of multiple, complementary coping strategies (Bonanno and Burton, 2013). On the basis of past empirical research that supports this latter approach in the case of video games (Cahill, 2021), we propose:

H2: The use of video games for coping with stress relates positively to the use of other forms of coping, rather than displacing them.

1.7 Affective responses

Past work on both MMT and coping has been subject to a remarkable degree of theoretical inconsistency in terms of how emotional responses are characterized. While some early scholars conceptualized emotion as a simple, one-dimensional scale running from negative to positive—such that a positively valenced stimulus would offset a negative mood—this view struggles to account for any motivated selection of media content with a less-than-positive tone (Zillmann, 2000). Considering positive and negative affect as separate dimensions of an emotional construct helps to resolve this difficulty and opens the way for the possibility of media experiences that individuals are motivated to select for themselves, despite mixed-affective content (Oliver et al., 2015).

Additional dimensions of emotion have also been theorized in relation to emotional regulation, most notably arousal, which articulates both the subjective intensity of emotional experience and the magnitude of the associated physiological response (Mehrabian, 1996; Bolls, 2017). Reinecke (2009) articulates the apparent paradox of games as a medium that is both associated with excitement and relaxation, and suggests that short-term increases in arousal during play may nevertheless be associated with subsequent alleviation of stress, in a manner similar to the relaxing after-effects of intense physical activity.

On this basis, we may hypothesize the type of emotional response that we would expect after an efficacious session of gaming in terms of the different models of emotion discussed above: Following MMT, positive affect or pleasure should be heightened as a product of successful mood management. At the same time, arousal should be lowered following gameplay consistent with the hypothesized effect of stress relief. Both theoretical frameworks would then also predict a decrease in negative affect as perhaps the most salient indicator of their impact on the player’s mood. We therefore propose:

H3a: Positive affect will be elevated following the use of video games for coping with stress.

H3b: Pleasure will be elevated following the use of video games for coping with stress.

H3c: Arousal will be reduced following the use of video games for coping with stress.

H3d: Negative affect will be reduced following the use of video games for coping with stress.

1.8 Study overview

The present exploratory study investigated these relationships through a survey measuring video gameplay habits, motivations, genre preferences, and emotional outcomes. The conceptual relationships of interest investigated in this study are illustrated in Figure 1, however, it should be noted that this is merely intended as a conceptual diagram and not as a unified, cohesive theoretical model, given the exploratory nature of the study.

2 Materials and methods

An exploratory survey was conducted to study the relationships between video gameplay habits, individual-level motivations for play, genre preferences, coping, emotional regulation, and emotional outcomes. Given that the study did not collect personally identifiable information and participation was deemed to pose no more than minimal risk to respondents, approval was granted under a standing protocol for anonymous self-report surveys authorized by the Institutional Review Board at the authors’ home institution. Data collection took place from April to December 2020. All respondents received compensation in the form of transferable course credit.

2.1 Sample

A convenience sample was collected (N = 348) of students enrolled in undergraduate and graduate communication courses at a large private research university in the Northeastern United States. The use of student samples has been rightly criticized in psychology (Hanel and Vione, 2016) and communication research (Meltzer et al., 2012); however, the particular intersection of behaviors that this study examines—playing video games and coping with stressful circumstances—with the typical university student experience suggests that these concerns are slightly less salient in this case, and that students do represent an appropriate population for study given the topic area (Russell and Newton, 2008; Bowman and Tamborini, 2012) and the exploratory nature of the research.

As noted below, respondents were asked to report how frequently they played video games. Respondents who reported playing games on at least a monthly basis (n = 220, 63.2%) were directed to the complete version of the questionnaire, containing all of the measures described in the following section. Respondents who reported never playing video games (n = 123, 35.3%) were directed to a shortened version of the questionnaire with all items that referred specifically to gameplay behavior, motivations, and experiences removed. This latter subsample of respondents who did not play games at all was collected with the intent of forming a point of reference for comparison against the subsample of respondents who did play games regularly for measures related to immersive tendencies, coping strategies, and state affect, as described below. As many of the research questions and hypotheses concerned the incidence, motivation for and effects of gameplay for coping relative to the population at large, analyses included participants who did not play games at all whenever possible. Where relevant, these participants were excluded from individual analyses as described in the associated reporting of results.

2.1.1 Data cleaning

All incomplete responses (n = 7) were removed from the dataset prior to analysis. Additionally, extreme outliers (n = 4) were identified based on reported average weekly gameplay time, using 80 h as the upper fence. This yielded a similar range of acceptability to the standard rule of for extreme upper outliers, was aligned with the upper bound of weekly gameplay credibly reported in other studies (Williams and Skoric, 2007; Griffiths, 2009) and has been used elsewhere as a threshold for reported weekly usage of video games and the Internet (Barke et al., 2013). Other variables were not used as a basis for outlier detection, since most other measures included in the analysis (e.g., ITQ, PANAS) had a constrained range, and thus were less susceptible to overestimation. Following data cleaning, 336 cases remained in the dataset used for analysis.

2.1.2 Demographic characteristics

Out of the complete sample (following the data cleaning procedures described above), 285 (84.8%) of respondents identified as female, 48 (14.3%) identified as male, one (0.3%) identified as non-binary, and two (0.6%) chose not to indicate a gender. The proportion of male to female respondents was significantly higher among the sub-sample who self-identified as playing video games (χ2(1) = 16.61, p < 0.001). The median age of respondents was 21 years.

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 Immersive tendencies

Immersive tendencies—referring, again, to the propensity to become involved and immersed in mediated experiences—was measured using the Immersive Tendencies Questionnaire (Witmer and Singer, 1998), which consists of a battery of 18 statements (e.g., “Do you ever become so involved in a video game that it is as if you are inside the game rather than moving a joystick and watching the screen?”) with a 7-point Likert-type scale of agreement ranging from “Not at all” to “Almost always.” Overall scale reliability was acceptable for the purposes of exploratory research (α = 0.751).

2.2.2 Gaming motivations

Motivations for and attitudes towards video gaming as an activity were measured using the Gaming Attitudes, Motives, and Experiences Scales (GAMES), developed by Hilgard et al. (2013). The use of this instrument in the present study was informed by both methodological and theoretical considerations: As this study was conducted in the context of an ongoing program of research, the use of a consistent scale across multiple studies conducted as part of the research project enables comparability and aggregation of findings, and more direct analysis of patterns that may appear across samples. Moreover, the instrument is well-suited to the research purpose of the present study: In contrast to instruments that have been developed with respect to particular genres or even specific games, or for the evaluation of problematic or maladaptive gaming behavior (López-Fernández et al., 2020; Király et al., 2022), GAMES was developed to capture a broad range of potential motivations across diverse play contexts and player populations. The motivational dimensions reflected in the instrument’s scales encompass both hedonic aspects of gameplay that may facilitate mood repair and more complex emotional motivations theorized to support long-term psychological resilience (Reinecke and Rieger, 2021), and are relevant to both casual and highly-engaged players.

The GAMES battery consists of 59 declarative statements (e.g., “I feel emotionally attached to the characters in my favorite games,” “Violent games allow me to release negative energy,” “I get upset when I lose to other players”) along with 5-point Likert-type scales of agreement ranging from “Strong disagree” to “Strongly agree.” The items are divided into nine scales reflecting different motivations for playing games drawn from the literature: Story, violent catharsis, violent reward, social interaction, escapism, loss-aversion, customization, grinding/completion, and autonomy/exploration. The reliability (Cronbach’s α) of these scales varied substantially, from 0.485 to 0.879. Accordingly, the loss-aversion and grinding/completion scales should be interpreted with caution due to low reliability (α < 0.6).

2.2.3 Gaming habits

For the purposes of this study, gaming habits refer to the specific preferences and tendencies that individuals may have when playing games, such as frequency and duration of play, and the genres of games played (Manero et al., 2017). Respondents were asked how frequently they play video games on a single-item scale from “Never” to “Daily.” Those that indicated a frequency of “Monthly” or higher were classified as players and directed to a series of follow-up questions asking respondents to rate how casual they considered themselves with regard to video gameplay (on a 5-point scale from “Very hardcore” to “Very casual”) and what proportion of their spare time they spent playing video games (on a 5-point scale from “Almost none” to “Almost all”). Finally, respondents were asked to estimate how many hours (using a continuous slider from 0 to 6 h) they spent playing video games during each 6-h interval on an average weekday and an average weekend day. These scales were subsequently aggregated into a measure of average weekly play time. As would be expected, preliminary analysis showed a strong correlation between reported weekly play time and proportion of time spent gaming (ρ = 0.642, p < 0.001).

As a rough measure of genre preferences, respondents were also provided with a list of 18 common game genre designations (e.g., “Platformer,” “Third-Person Action,” “Real-Time Strategy”), along with an exemplar title for each category (“Donkey Kong,” “Tomb Raider,” “Age of Empires”), drawn from Von Der Heiden et al. (2019). Respondents were asked how frequently they played games within that genre on a 4-point scale from “Never” to “Very often.”

2.2.4 Coping strategies

Respondents also completed a modified version of Carver’s (1997) Brief COPE scale, which asks about the frequency of 30 common coping behaviors such as “reading,” “getting emotional support from others,” or “using alcohol or other drugs,” using a 4-point scale. For our purposes, the instructions were modified to emphasize that participants’ responses should reflect their coping strategies “since the COVID-19 pandemic began to affect your community,” on the basis of empirical evidence suggesting that individual responses to stress may have been altered significantly relative to a pre-pandemic context, particularly with respect to gaming behavior (Fu et al., 2020; King et al., 2020; Ko and Yen, 2020; Park et al., 2020; Cahill, 2021). Additionally, five items specifically addressing video gameplay and related behaviors were added to this instrument (e.g., “I’ve been playing video games with people I live with” and “I’ve been playing video games alone”). For most measures, these items were averaged into a single overall game-based coping scale. However, as we have specific theoretical interest in potential differences between multiplayer and single-player gaming experiences and coping, these two items were also used individually to report multiplayer coping and single-player coping.

2.2.5 State affect

Respondents’ emotional state was measured using two instruments, reflecting two different conceptualizations of affect (two-dimensional and three-dimensional), and on two different time scales (medium-term and short-term).

All respondents completed a version of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) (Watson et al., 1988), which provides a list of 10 positively-valenced and 10 negatively-valenced emotional descriptors (e.g., “Proud,” “Hostile”) and asks how well each describes their feelings over the past month on a 5-point scale from “Does not describe” to “Clearly describes.” These scores were then aggregated to reflect positive and negative dimensions of the respondents’ affective state.

All respondents also completed a version of the Pleasure, Arousal, and Dominance (PAD) scale (Mehrabian, 1996) using a series of three pictorial scales, each containing five pictorial (self-assessment manikin) representations of scale points ranging from negative to positive valence, from low to high arousal, and from low to high dominance, respectively (Morris, 1995).

Respondents who reported playing video games on at least a monthly basis were also directed to recall a specific time when they played a video game in the past month, and then completed versions of both the PANAS and PAD instruments to indicate how they recalled feeling after they completed their play session.

3 Results

3.1 Incidence of game-based coping

Before reporting analyses pertaining to research questions and hypotheses, we first note the prevalence of game-based coping, as well as its association with individual demographic characteristics. Consistent with past findings (Cahill, 2021), a substantial majority (n = 215, 64.0%) of all respondents reported engaging in some form of coping using video games. More than half of all respondents (n = 175, 52.1%) reported playing alone (single-player coping) to cope with stress, while an even greater number (n = 192, 57.1%) reported playing video games with others (multiplayer coping) to cope with stress, either in-person or online.

The incidence of game-based coping was first contrasted between male and female respondents (n = 333). Male respondents were significantly more likely than female respondents to report engaging in overall game-based coping, χ2(1) = 4.37, p = 0.037. This trend was even more pronounced for coping through single-player games (χ2(1) = 8.26, p = 0.004), but was not significant for coping through multiplayer games (χ2(1) = 3.29, p = 0.070). However, these group differences are at least partially a function of male respondents being generally more likely to play video games on a regular basis. As a demonstration of this, gender ceased to be a significant predictor of game-based coping when controlling for the frequency of overall video gameplay using a logistic regression model, χ2(1) = 3.73, p = 0.053.

3.1.1 Immersive tendencies

To test the first hypothesis, regarding the relationship between immersive tendencies and game-based coping, a series of t-tests were conducted, comparing immersive tendencies among both those who did and did not use games for coping (n = 336). Those who reported engaging in game-based coping ranked significantly higher on the immersive tendencies scale than those who did not (d = 0.32, t(334) = 2.85, p = 0.005). This trend held true for coping activity through both single-player (d = 0.32, t(334) = 2.97, p = 0.003) and multiplayer games (d = 0.33, t(334) = 2.96, p = 0.003). Likewise, immersive tendencies were positively correlated with the extent of reported game-based coping in both single-player (r = 0.19, p < 0.001) and multiplayer (r = 0.17, p = 0.001) contexts. H1 was therefore supported, and these findings were consistent with past research indicating the relevance of immersive tendencies as a notable predictor of a preference for game-based coping styles in individuals.

3.1.2 Gaming motivations

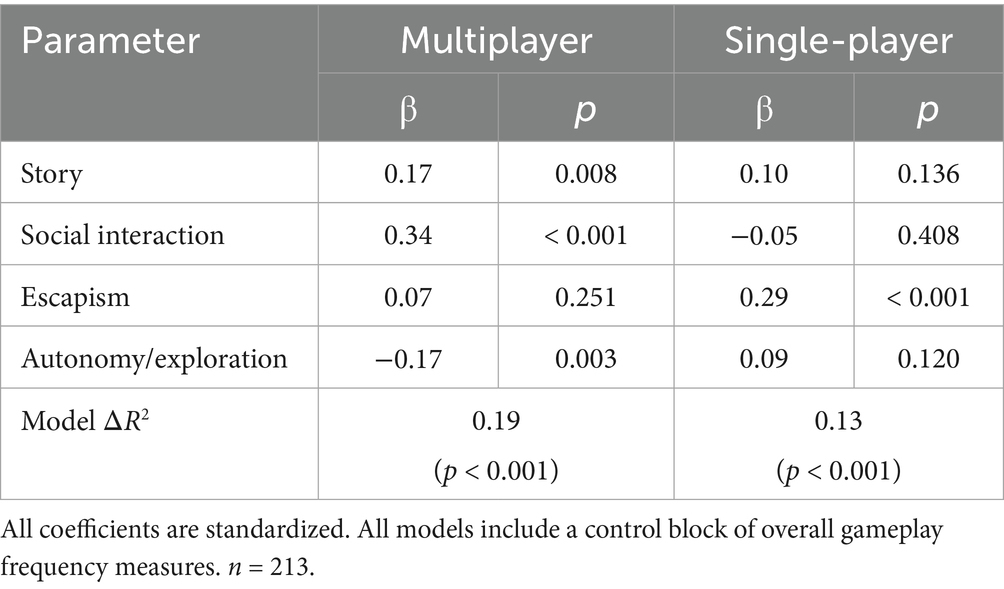

A set of hierarchical linear models was used to investigate the first research question, regarding the effects of gaming motivations on the extent to which individuals reported engaging in coping through video gameplay. Since the gaming motivation measures refer specifically to those who actively play video games in some capacity, only those who reported playing games on at least a monthly basis (n = 213) were included in these models. A control model was fit containing ordinal measures of overall gameplay frequency. This control model accounted for a significant proportion of the observed variance in game-based coping, F(3, 209) = 44.28, R2 = 0.389, p < 0.001. Scales of gameplay motivation from the GAMES battery were then entered into the model in two blocks: The first block contained those aspects of gameplay motivation that were associated, on some level, with coping in the literature, and were thus considered most theoretically salient: story, social interaction, escapism, and autonomy/exploration. The second block contained the remaining gaming motivation scales. The impetus for this approach was to balance the desire for a parsimonious, theoretically grounded model while also reflecting the exploratory nature of the study. See Table 1 for a complete reporting of all model parameters.

The first block showed a significant improvement over the control model, together accounting for over half of the observed variance, F(7, 205) = 34.89, p < 0.001; R2 = 0.544. Motivational orientations towards story (β = 0.16, t = 2.84, p = 0.005), social interaction (β = 0.23, t = 4.17, p < 0.001), and escapism (β = 0.18, t = 2.97, p = 0.003) were all statistically significant predictors of increased game-based coping behavior. By contrast, none of the alternative scales contained in the second block showed a statistically significant relationship with coping, and the addition of the block as a whole did not result in a significant improvement in model performance, supporting the theoretical orientation of the selected motivational parameters, F(5, 200) = 0.61, p = 0.689; ΔR2 = 0.007.

On this basis, two additional models were fit on reported levels of coping through multiplayer and single-player games, separately. These models contained a similar control block reflecting gameplay frequency, as well as the four theoretically salient motivational scales (see Table 2). Notable differences emerged in these two models reflecting potentially distinct motivational antecedents for coping through play with others, as opposed to play alone: Motivation through social interaction was the main predictor of increased coping through multiplayer games (β = 0.34, t = 5.81, p < 0.001), but was not a significant predictor of coping through single-player games. In contrast, escapism was the only statistically significant predictor of coping through single-player games (β = 0.29, t = 4.26, p < 0.001), but did not predict coping through multiplayer games. Story motivation was also a significant predictor of coping through multiplayer games (β = 0.17, t = 2.68, p = 0.008), and while a similar relationship was observed for single-player games (β = 0.10), it was not statistically significant within the model. Motivation based on autonomy and exploration appeared to negatively influence the propensity to cope through multiplayer games (β = −0.17, t = −2.98, p = 0.003), but did not have a significant impact on single-player games.

3.1.3 Moderating effects of motivation

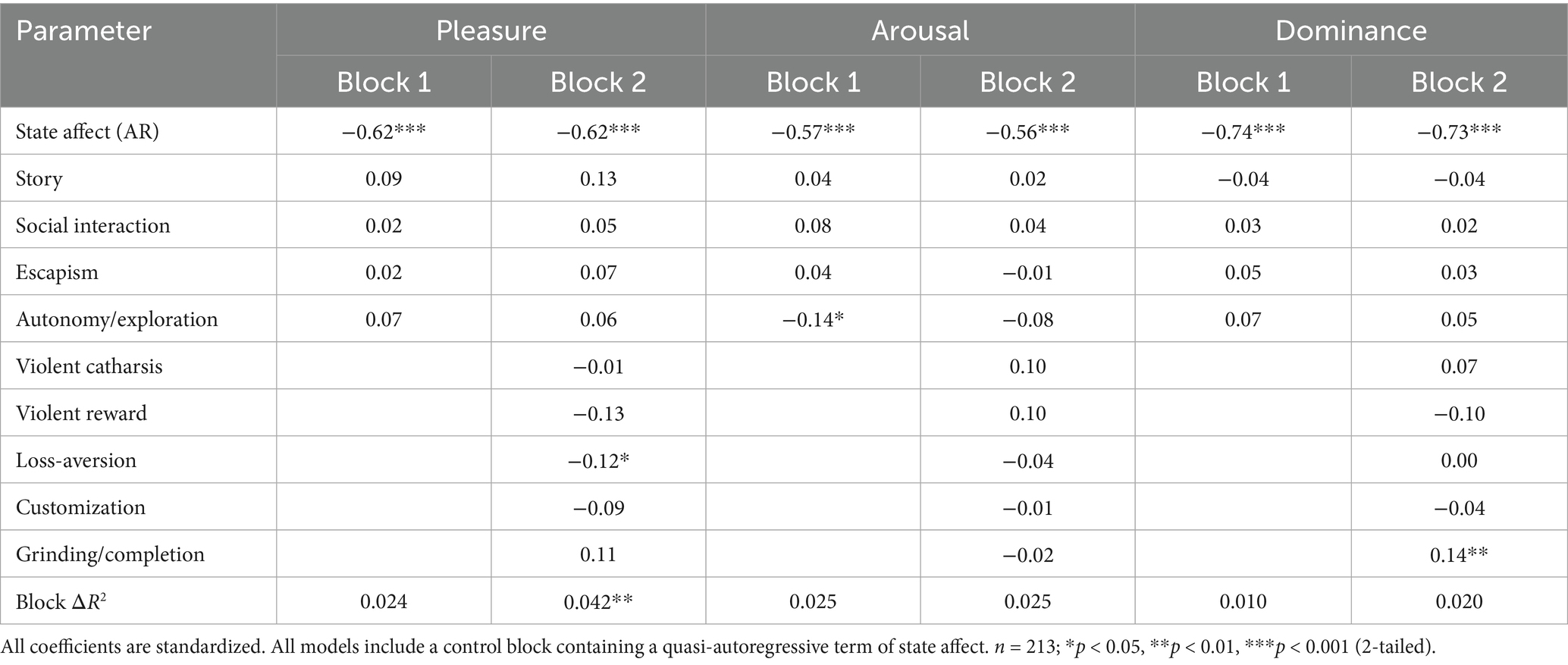

The second research question regards the extent to which individual gaming motivations influenced the effectiveness of gameplay for mood repair and coping with stress. To investigate RQ2, change scores were calculated first based on reported medium-term and post-gaming levels of each dimension of state affect (using both PAD and PANAS scores) to approximate the short-term effect of a gaming session on each respondent who reported playing games at least monthly on their emotional state (n = 213). A series of linear regression models were then fit on these difference scores using the same hierarchical block design outlined in the preceding section. For several of these dimensions, the change scores were also correlated with medium-term state affect levels (e.g., reduction in negative affect from medium-term to post-gaming levels was significantly greater for those with an overall higher level of medium-term negative affect, r = − 0.601, p < 0.001). For this reason, state affect was entered as a quasi-autoregressive control term for each model. See Tables 3, 4 for a complete reporting of model and block-level parameter estimates.

On the whole, motivational factors accounted for a small, yet statistically significant proportion of post-gaming differences in respondents’ emotional state1, along the dimensions of positive affect (ΔR2 = 0.20, F(9, 202) = 8.03, p < 0.001), negative affect (ΔR2 = 0.11, F(9, 202) = 4.65, p < 0.001), and pleasure (ΔR2 = 0.07, F(9, 202) = 2.76, p = 0.005). Notably, in several of these models, alternative motivational factors that have not been well-covered in the literature were observed to have a significant effect, as discussed below.

Distinct motivations were implicated in the moderation of post-gaming emotion, compared to the decision to play games to cope with stress. When only the first block of motivational factors was considered, motivational orientation towards story (β = 0.17, p = 0.012), social interaction (β = 0.13, p = 0.037), and escapism (β = 0.17, p = 0.014) were associated with greater increases in positive affect. With the inclusion of the second block, orientation towards grinding and completionism was also associated with greater increases in positive affect (β = 0.27, p < 0.001). Uniquely among all of the models incorporating motivational parameters, an orientation towards grinding/completion was also observed to correspond to post-gaming increases in dominance (β = 0.14, p = 0.010). Similarly, autonomy and exploration motivations enhanced reductions in post-gaming negative affect (β = −0.19, p = 0.002) and arousal (β = −0.14, p = 0.026). By contrast, story motivations were associated with increases in negative affect (β = 0.15, p = 0.023), as were motivations associated with violent catharsis when entered as part of the second block (β = 0.17, p = 0.024). Finally, there was a statistically significant association of loss-aversion with post-gaming reductions in pleasure (β = −0.12, p = 0.037); however, this effect should be interpreted with caution given the comparatively low performance and fit of the model, as noted above.

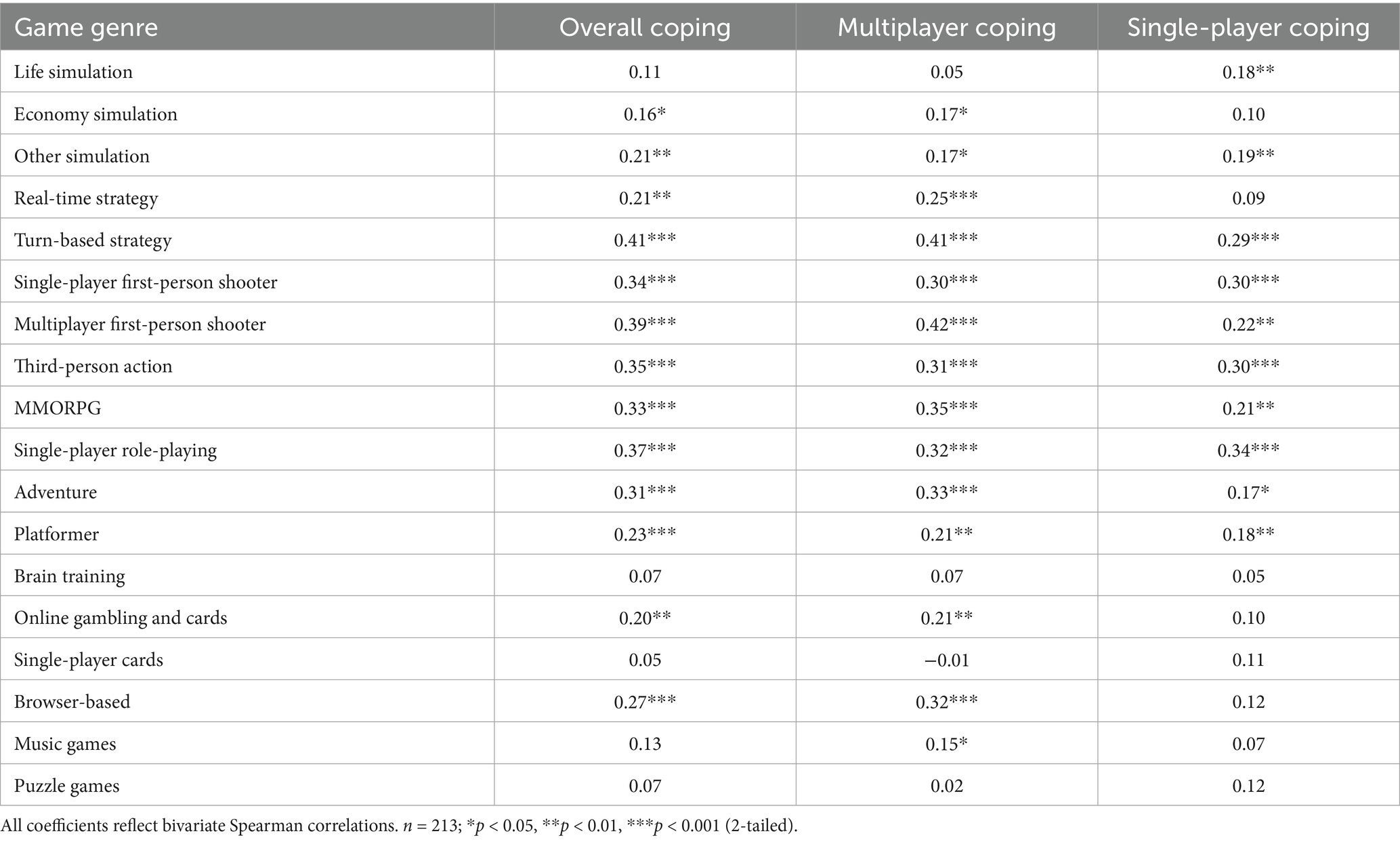

3.1.4 Preferred gameplay genres

The third research question concerns genre preferences and the use of video games for coping. To present the relationships involving preferences for many different genres and game-based coping clearly and directly, Spearman correlations2 were established between the reported frequency of play in 18 game genres and reported game-based coping (see Table 5). These allow for a parsimonious account of the relationship between observed genre preferences and coping, without controlling for factors that might closely relate to genre preferences (e.g., overall time spent gaming, motivations for gaming). Correlations were also established with coping specifically through single-player and multiplayer games, keeping in mind that some genre designations are explicitly associated with multiplayer modes of play (e.g., MMORPGs) while others may have both single-player and multiplayer elements (e.g., real-time strategy). Notably, these analyses compare participants’ preference for games as a coping tool with their preference for certain genres, rather than the specific instance of playing each genre as a form of coping strategy and should be interpreted with caution.

Nonetheless, numerous significant positive correlations were observed between preferences for several genres and the tendency to cope with stress through video games: The strongest associations were with turn-based strategy (ρ = 0.41, p < 0.001), single-player and multiplayer first-person shooters (ρ = 0.34, p < 0.001; ρ = 0.39, p < 0.001), single-player and multiplayer role-playing games (ρ = 0.37, p < 0.001; ρ = 0.33, p < 0.001), third-person action games (ρ = 0.35, p < 0.001), and adventure games (ρ = 0.31, p < 0.001). While all observed correlations were positive, several were small enough not to be statistically significant, for example, puzzle games (ρ = 0.07) and single-player card games (ρ = 0.05).

After dividing game-based coping behavior into play alone and play with others, some notable differences in the associated genre preferences emerged: for instance, preference for the life simulation genre was uniquely associated with coping through solo play (ρ = 0.18, p = 0.010), while preference for the economy simulation genre was more strongly associated with coping through multiplayer activity (ρ = 0.16, p = 0.016). Stronger preferences for real-time strategy games (ρ = 0.25, p < 0.001), online gambling and card games (ρ = 0.21, p = 0.002), browser-based games (ρ = 0.32, p < 0.001), and music games (ρ = 0.15, p = 0.031) were likewise uniquely associated with coping through play with others.

Given that both genre preferences and gaming motivations arguably relate to the predilection of the individual player towards particular mechanical or narrative gameplay elements—albeit through very different conceptual lenses—it seemed worthwhile to investigate the possibility that these two factors overlapped to the point of redundancy. For this reason, an additional parameter block containing all genre preference measures was added to the previously fit model containing gaming motivation measures (see Table 1). While this expanded model was not parsimonious enough for the parameter estimates to be illustrative on their own, it was observed that the addition of genre measures resulted in a small but significant increase in model performance (ΔR2 = 0.08, F(18, 182) = 2.17, p = 0.005). This suggests that genre designations capture some dimension of difference between games that is both salient for use in coping and not fully accounted for by motivational factors.

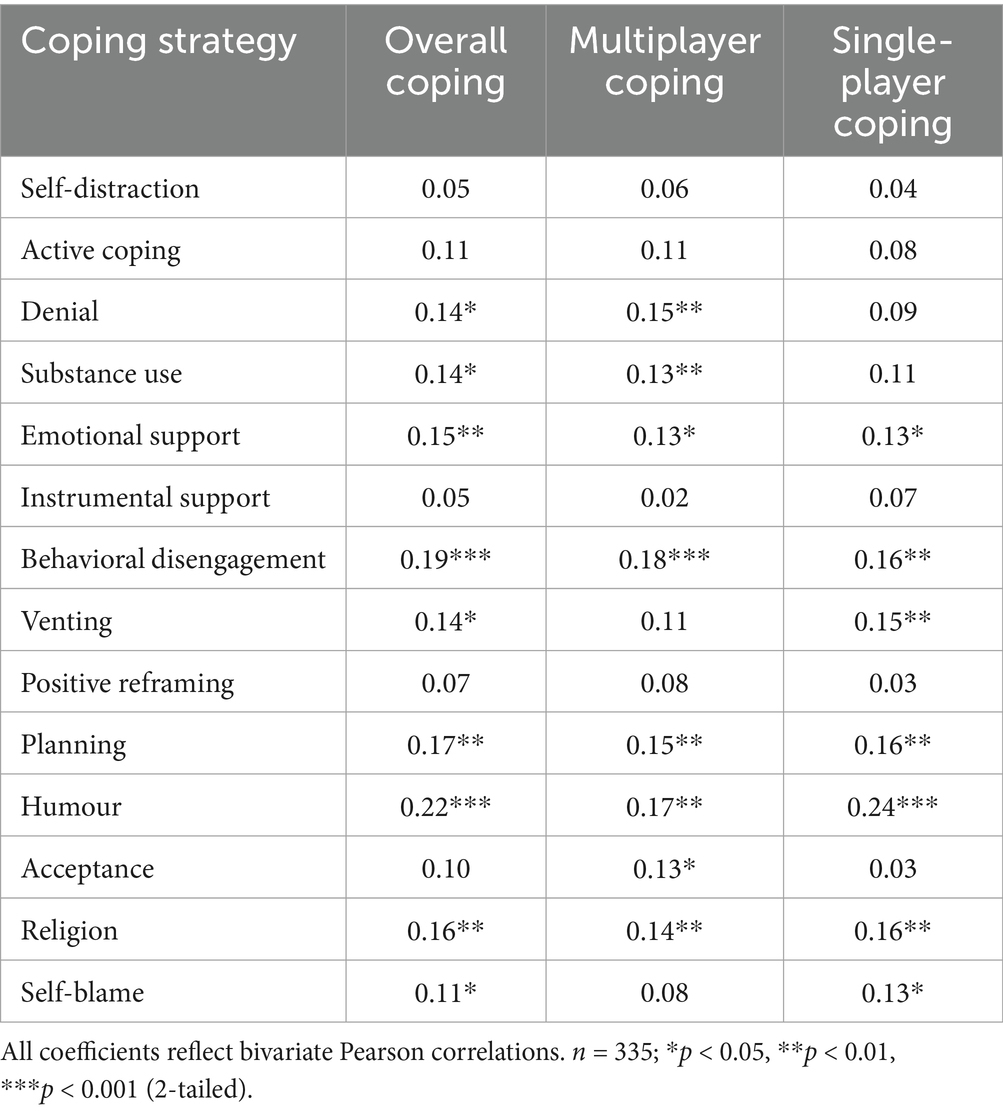

3.2 Displacement effects

The second hypothesis, that the use of games for coping would be positively associated with other forms of coping, was assessed through a series of bivariate Pearson correlations comparing coping through gaming to the other components of the Brief COPE scale. Here, 11 out of 14 other coping behaviors showed significant positive, albeit weak, correlations with coping through gaming, providing support for H2. This suggests a complementary approach between a wide variety of coping techniques, including the use of video games, rather than the displacement of other coping behaviors by gameplay. Notably, significant positive correlations were observed between game-based coping and coping behaviors that are typically appraised as adaptive in the literature, such as emotional support (r = 0.15, p = 0.007) and planning (r = 0.17, p = 0.002), as well as those typically appraised as maladaptive, such as denial (r = 0.14, p = 0.011), behavioral disengagement (r = 0.19, p < 0.001), and substance use (r = 0.14, p = 0.012). Only small differences were observed in the correlations of single-player and multiplayer gameplay with alternative coping styles. See Table 6 for a complete reporting of all correlation coefficients.

3.3 Affective responses

To test the hypotheses regarding state affect before and after gaming, a series of t-tests were conducted, first comparing medium-term PANAS and PAD scores between participants who reported playing games as a means of coping and those who did not, to establish potential emotional precursors to game-based coping behavior. As these hypotheses are primarily concerned with the effects of a session of gameplay, t-tests were also conducted to compare the medium-term affect of participants who played games at least monthly with the state affect they described following a session of gameplay. In conjunction, these analyses allow us to understand both how participants who use games to cope differ from those who do not, as well as how gameplay directly influences affective states.

Within the entire sample (including respondents who did not play video games at all; n = 336), the general medium-term positive affect and pleasure of those who chose to use video games to cope with stress was significantly lower than those who did not, d = −0.27, t(334) = −2.39, p = 0.018; d = −0.27, t(334) = −2.34, p = 0.020. No significant differences were observed in the medium-term levels of negative affect, arousal, or dominance.

Conversely, for those who did play video games on at least a monthly basis (n = 213), reported post-gaming positive affect was elevated, although the increase from the medium-term baseline was not statistically significant (d = 0.80, t(212) = 1.17, p = 0.121). Reported post-gaming levels of pleasure were significantly higher than their overall medium-term levels over the preceding month (d = 0.65, t(212) = 9.50, p < 0.001). Post-gaming levels of arousal were also significantly lower (d = −0.40, t(212) = −5.81, p < 0.001), indicating a potential short-term calming or stress reduction effect of gameplay. Post-gaming levels of negative affect were also significantly lower (d = −0.95, t(212) = −13.84, p < 0.001). Taken as a whole, these results support H3b, H3c and H3d, but not H3a. In sum, these results provide support for both mood management and stress relief as outcomes of game-based coping.

4 Discussion

This exploratory study of coping activity and mood management using video games builds upon previous research in the area by confirming the widespread prevalence of the phenomenon and the salience of individual psychological differences, as well as by expanding our nascent understanding of the differences between games in this context. Approaching the choice to play video games during times of stress, ego depletion, or negative emotion as an instance of selective exposure driven by individual needs allows the field to move away from the paradigm of treating gaming as a monolithic activity. From here, scholars can move towards theoretical models that can articulate different dimensions of the play experience in terms of their psychological significance for players. Our key findings support this reorientation at the intersection of game studies and media psychology by providing a tentative outline of the motivational pathways that lead to coping through video games, and how the interactions between player motivations and the play experience predict psychological outcomes of this behavior.

4.1 Key findings

The results of this study suggest connections between the use of video games for coping and mood repair and individual psychological needs on the level of both stable personality traits and medium-term emotional states. Immersive tendencies were identified as a relevant predictor of an individual’s likelihood of using games to cope with stress, further establishing this as a salient aspect of personality for understanding behavioral patterns of engagement with new media (Cahill, 2021; Cummings et al., 2022). This measure is often deployed in studies involving the use of games and virtual reality but remains undertheorized to the point where it remains unclear whether this reflects a latent psychological need, or merely an affinity for certain types of mediated experience.

Several novel relationships emerged between individuals’ motivations for gaming and their propensity to cope through video games. This builds upon recent studies that have illustrated the important role of player motivations in the complex relationships between video game use and psychological well-being (von der Heiden et al., 2019) and also addresses gaps in the literature on mood management (Villani et al., 2018) by attempting to isolate specific motivational pathways that lead to selective exposure. The results of the present study confirm the overall relevance of player motivations for coping behavior, and in particular, orientations towards story, social interaction, and escapism. The nature of these motivations suggests that while some players do use games for the purpose of avoidant coping and recovery, there may be other psychological needs at play that encourage players to seek out meaningful narrative experiences or social connection in games as a response to stress (Rieger et al., 2014a).

Notable differences were observed between the motivations involved in coping through playing single-player games versus coping through multiplayer games. As might be expected, social interaction was closely associated with multiplayer game-based coping but was not significantly associated with coping through single-player games. In addition to being a fairly intuitive finding given the intrinsically social component of multiplayer game design, this observation aligns with past studies that focused on the motivations of online players (Yee, 2006; Hainey et al., 2011; Bonny and Castaneda, 2022). Conversely, coping by playing games alone was closely associated with a motivational orientation towards escapism, while this was not significantly associated with coping through multiplayer games. This association of escapist motivations with exclusively single-player game-based coping may be accounted for by noting that escapism typically implicates a desire to separate or remove oneself, at least temporarily, from “the real world” and its associated concerns. The fulfillment of this desire may therefore be made more difficult by the intrusion of real-world interpersonal relationships and social interactions into the game world. This aligns with the grouping of escapism into the “self-oriented play” cluster of motivations observed by Tychsen et al. (2008) in their study of play motivations in the context of role-playing games (RPGs).

Preferences for genres were also observed to be associated with the use of games for coping, to a degree not entirely accounted for by motivational factors alone. This suggests that subjective understanding of genre categories by players—which they presumably use to appraise and select from potential games—captures some salient aspects of the experience that go beyond the largely mechanical affordances addressed through the GAMES framework (Hilgard et al., 2013). Understanding genre as a heuristic for multi-layered, evolutionary combinations of game mechanics, aesthetics, narratives, and production practices, as has been suggested by numerous critical scholars (Apperley, 2006; Arsenault, 2009; Clearwater, 2011; Clarke et al., 2017), may thus lead to a deeper understanding of both selective exposure and media effects as they pertain to video games.

Following the model of emotional regulation as a control system (Larsen, 2000; Villani et al., 2018), coping or mood management strategies will inherently operate as both a response to and an influence upon the emotional state of the individual. This dynamic was observed in the present study, which found that respondents were more likely to engage in game-based coping when their overall mood was lower, as indicated by lower levels of pleasure and positive affect. Subsequent to a gaming session, however, respondents reported significantly improved mood states—notably, this was marked by a decrease in negative affect and arousal, suggesting that not only did playing games provide players with enjoyment, but also relaxation and relief. Theoretically, this helps to situate games within the intersection of mood management and stress response.

In addition to affecting the decision to use games to cope with stress, gaming motivations were also observed to moderate the effects of play on respondents’ emotional state, in an interaction that has been frequently theorized (Villani et al., 2018) but rarely measured empirically. In this context, greater post-gaming improvements in positive affect were associated with motivational orientations towards story, social interaction, and escapism, while players who were motivated by a sense of autonomy and the ability to explore appeared to experience the greatest reduction in negative affect as a result of playing video games, which aligns with suggestions that the innate psychological need for autonomy is related to mood repair (Reinecke et al., 2012; Rieger et al., 2014b). In this study, autonomy also strengthened the observed attenuating effect of gameplay on arousal, suggesting that fulfillment of this need plays a role in stress response as well.

While the present study was not intended to test the R2EM model (Reinecke and Rieger, 2021), its findings can nevertheless be productively interpreted through this framework. In particular, the observation of motivational orientation towards narrative involvement as a significant predictor of game-based coping aligns with the eudaimonic elements of the model by suggesting that when coping with stress, players seek not only distraction but also opportunities for meaning-making through engagement with interactive narrative. The observation that narrative motivations were associated with post-gaming increases in both positive and negative affect is also consistent with the mixed affect typical of eudaimonic experience (Oliver and Raney, 2011). Our findings also broadly align with Possler et al.’s (2024) observation that game selection is informed in part by both hedonic and eudaimonic motivations, which are in turn influenced by individual and situational factors.

4.2 Limitations and future directions

The results of this study are unfortunately bounded by the inherent limitations of a cross-sectional survey design—by observing respondents’ emotional states at a single point in time, we are prevented from making causal inferences, and must rely, to some extent, on the memory of respondents, which may be prone to error (Kahn et al., 2014; Araujo et al., 2017; Sewall et al., 2020). Additionally, the cross-sectional design limited our ability to investigate the longer-term resilience-building effects proposed by the R2EM model (Reinecke and Rieger, 2021). Future studies may address these shortcomings by collecting longitudinal data on user experiences through panel surveys or journal studies, and by leveraging software logging through platforms like Steam to generate more reliable measures of behavior (Dale and Green, 2017; Vuorre et al., 2022).

It should also be noted that our analysis involved multiple hypothesis tests, thereby inflating the family-wise error rates for the study (i.e., the probability for each group of tests that the results include one or more Type I errors). We have elected not to attempt to control the family-wise error rate in our reporting of results, given the exploratory nature of the study. Additionally, the degree of statistical significance in most instances where we have rejected the null hypothesis is such that even a relatively conservative correction such as the Bonferroni procedure would not substantively alter our conclusions. This being said, those results with more marginal significance (0.001 < p < 0.05) should be interpreted with greater caution.

Since the inception of this research project, additional instruments for the measurement of gaming motivations have been developed, such as the Gaming Motivation Inventory (Király et al., 2022) and the Motivation to Play Scale (Holl et al., 2024), which may have superior psychometric properties or expanded coverage of relevant motivational factors compared to the GAMES instrument (Hilgard et al., 2013) used in the present study. Therefore, future research examining the relationship between gaming motivations and game-based coping may benefit from evaluating these newer scales. Comparative studies using multiple instruments in parallel could also help clarify which theoretical constructs are most relevant for understanding players’ motivations in the specific context of emotional regulation and stress management.

The generalizability of this research is also constrained by the nature and context of the sample used. While we contend that the population of university students is more relevant to this topic than most, efforts should nonetheless be made in future studies to recruit a more diverse sample of respondents and to employ probabilistic sampling techniques. There may be substantive differences in the frames of reference used by older adults to engage in emotional appraisal, as well as to select gaming experiences. Furthermore, the findings of this study are limited by a geographic focus on the United States and would ideally be contrasted against parallel data drawn from other national and cultural contexts. Finally, our sample consisted predominantly of women (84.8%), limiting our ability to generalize to men. However, while gender differences were noted with regard to gameplay for coping, these differences vanished when controlling for time spent playing games. On the whole, this suggests that gender is principally meaningful in this context insofar as it serves as a weak proxy for interest in video games, and is of limited theoretical concern once time or interest in games is accounted for.

Data collection for the study also took place in the midst of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, which likely affected respondents’ daily routines and levels of stress. While this fact does demand confirmation of these findings through future studies as the immediate social and psychological effects of the pandemic dissipate, the context arguably renders the present study even more necessary. Initial research suggests that the stress of the pandemic and the associated public health restrictions may have led individuals to adopt new patterns of coping behavior, particularly with respect to video games and entertainment media (Fu et al., 2020; King et al., 2020; Cahill, 2021), and there is no guarantee that this behavioral shift will simply reverse once the conditions that necessitated it subside.

Finally, while the results of this study demonstrate the continued practical relevance of genre distinctions to media psychology, the instrument used for operationalizing genre preferences was fairly crude and relied on an arbitrary typology, which has been used in past research (von der Heiden et al., 2019) but lacks a strong theoretical basis. This is indicative of the significant work that still remains to be done in forming psychologically meaningful genre classifications for video games and accompanying measurement techniques (Apperley, 2006; Prena et al., 2018; Dale et al., 2020), including a general tendency towards inconsistent, arbitrary, and contradictory approaches to classifying games in psychological research (Starosta et al., 2024).

The challenges inherent in video game genre classification are further compounded by a historical increase in what have been variously referred to as “hybrid genres” (Dale and Green, 2017; Dale et al., 2020) or “genre collapse” (Bowman et al., 2025), based on the observation that modern games increasingly include design aspects that would conventionally be associated with several different game genres, and thereby resist categorization using established genre labels. Dale et al. (2020) give as examples of games belonging to a hybrid genre the action-RPGs The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim (2011) and Mass Effect: Andromeda (2017), observing that “each contain elements of both classic RPGs and classic shooter games” (p. 5). A preliminary cluster analysis of 100 modern and 100 retro games by Bowman et al. (2025) indicated that more than half of modern games may be described as “mixed genre” in contrast to retro games, which displayed much more clearly delineated boundaries between genre categories. The implications of genre collapse for research into the psychological effects of video games on players are significant in that the utility of categorical genre designations for generalizing and contrasting results is substantially reduced (Dale and Green, 2017; Dale et al., 2020).

Several approaches have been taken in recent years to address these issues, including preliminary attempts to operationalize genre in non-discrete ways that account more readily for hybridity, such as a semantic network (Li and Zhang, 2020) or continuous multidimensional space (Bowman et al., 2025); in these models, differentiating the genre from one game to another is more a matter of distance than boundary conditions. Starosta et al. (2024) argue that there may also be some utility in treating genres as “constellations of lower-order characteristics” (p. 26) and that, for at least some research questions, “we should not divide games into MMORPGs and non-MMORPGs but ask what mode the participants of the study play in, or at least what modes the game offers” (p. 26). Given these limitations, the use in the present study of conventional genre categories represented a pragmatic compromise, which was justified by the absence of a practically implementable and widely accepted alternative methodology. However, we nevertheless observe that our results are in line with the general principle that lower-order measures of engagement, such as player motivations, may ultimately prove to be more valuable within the domain of media psychology.

Despite these limitations, this study nevertheless offers a novel contribution to the scientific understanding of how individuals select game experiences to support their own emotional well-being through coping and mood regulation, and the role that individual differences play in moderating the emotional effect of these experiences.

Data availability statement

The original dataset generated as part of this study contains individual survey responses and is considered confidential per the approved research protocol for the study. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to TC, dGpjYWhpbGxAYnUuZWR1.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Boston University Charles River Campus IRB. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

TC: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JC: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. EW: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^For these comparisons only, ΔRwas calculated for the joint entry of both blocks of motivation variables (i.e., all of the GAMES gaming motivation scales).

2. ^Given the unequal distribution of preferences across different genre categories, Spearman’s rank-order correlation was used for this analysis.

References

Apperley, T. H. (2006). Genre and game studies: Toward a critical approach to video game genres. Simul. Gaming 37, 6–23. doi: 10.1177/1046878105282278

Araujo, T., Wonneberger, A., Neijens, P., and de Vreese, C. (2017). How much time do you spend online? Understanding and improving the accuracy of self-reported measures of internet use. Commun. Methods Meas. 11, 173–190. doi: 10.1080/19312458.2017.1317337

Arsenault, D. (2009). Video game genre, evolution and innovation. Eludamos 3, 149–176. doi: 10.7557/23.6003

Austenfeld, J. L., and Stanton, A. L. (2004). Coping through emotional approach: A new look at emotion, coping, and health-related outcomes. J. Pers. 72, 1335–1364. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2004.00299.x

Barke, A., Nyenhuis, N., Voigts, T., Gehrke, H., and Kröner-Herwig, B. (2013). The Compulsive Internet Use Scale (CIUS) adapted to assess excessive multiplayer gaming. J. Addict. Res. Ther. 4, 164–170. doi: 10.4172/2155-6105.1000164

Bolls, P. D. (2017). “Arousal and activation,” in The international encyclopedia of media effects, eds. P. Rössler, C. A. Hoffner, and L. Zoonen (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons) doi: 10.1002/9781118783764.wbieme0202

Bonanno, G. A., and Burton, C. L. (2013). Regulatory flexibility: An individual differences perspective on coping and emotion regulation. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 8, 591–612. doi: 10.1177/1745691613504116

Bonny, J. W., and Castaneda, L. M. (2022). To triumph or to socialize? The role of gaming motivations in multiplayer online battle arena gameplay preferences. Simul. Gaming 53, 157–174. doi: 10.1177/10468781211070624

Bowditch, L., Chapman, J., and Naweed, A. (2018). Do coping strategies moderate the relationship between escapism and negative gaming outcomes in World of Warcraft (MMORPG) players? Comput. Human Behav. 86, 69–76. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2018.04.030

Bowman, N. D., Daneels, R., and Possler, D. (2024). Excited for eudaimonia? An emergent thematic analysis of player expectations of upcoming video games. Psychol. Pop. Media 13, 416–427. doi: 10.1037/ppm0000474

Bowman, N. D., Klecka, H., Li, Z., Yoshimura, K., and Green, C. S. (2025). A continuous-space description of video games: A preliminary investigation. Psychol. Pop. Media 14, 187–193. doi: 10.1037/ppm0000522

Bowman, N. D., and Tamborini, R. (2012). Task demand and mood repair: The intervention potential of computer games. New Media Soc. 14, 1339–1357. doi: 10.1177/1461444812450426

Bowman, N. D., and Tamborini, R. (2015). “In the mood to game”: Selective exposure and mood management processes in computer game play. New Media Soc. 17, 375–393. doi: 10.1177/1461444813504274

Braun, B., Stopfer, J. M., Müller, K. W., Beutel, M. E., and Egloff, B. (2016). Personality and video gaming: comparing regular gamers, non-gamers, and gaming addicts and differentiating between game genres. Comput. Human Behav. 55, 406–412. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2015.09.041

Brockman, R., Ciarrochi, J., Parker, P., and Kashdan, T. (2017). Emotion regulation strategies in daily life: Mindfulness, cognitive reappraisal and emotion suppression. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 46, 91–113. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2016.1218926

Bryant, J., and Zillmann, D. (1984). Using television to alleviate boredom and stress: Selective exposure as a function of induced excitational states. J. Broadc. 28, 1–20. doi: 10.1080/08838158409386511

Cahill, T. (2021). Gaming as coping in response to COVID-19 pandemic-induced stress: Results from a U.S. national survey. Paper presented at the 71st Annual International Communication Association Conference, Virtual.

Carver, C. S. (1997). You want to measure coping but your protocol’s too long: consider the brief COPE. Int. J. Behav. Med. 4, 92–100. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm0401_6

Clarke, R. I., Lee, J. H., and Clark, N. (2017). Why video game genres fail: A classificatory analysis. Games Cult. 12, 445–465. doi: 10.1177/1555412015591900

Clearwater, D. A. (2011). What defines video game genre? Thinking about genre study after the great divide. Loading. J. Canad. Game Stud. Assoc. 5, 29–49.

Comello, M. L. G., Francis, D. B., Marshall, L. H., and Puglia, D. R. (2016). Cancer survivors who play recreational computer games: Motivations for playing and associations with beneficial psychological outcomes. Games Health J. 5, 286–292. doi: 10.1089/g4h.2016.0003

Cummings, J. J., Cahill, T. J., Wertz, E., and Zhong, Q. (2022). Psychological predictors of consumer-level virtual reality technology adoption and usage. Virtual Reality 27, 1357–1379. doi: 10.1007/s10055-022-00736-1

Dale, G., and Green, C. S. (2017). The changing face of video games and video gamers: Future directions in the scientific study of video game play and cognitive performance. J. Cogn. Enhanc. 1, 280–294. doi: 10.1007/s41465-017-0015-6

Dale, G., Joessel, A., Bavelier, D., and Green, C. S. (2020). A new look at the cognitive neuroscience of video game play. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1464, 192–203. doi: 10.1111/nyas.14295

Daneels, R., Bowman, N. D., Possler, D., and Mekler, E. D. (2021). The ‘eudaimonic experience’: A scoping review of the concept in digital games research. MaC 9, 178–190. doi: 10.17645/mac.v9i2.3824

De Grove, F., Cauberghe, V., and Van Looy, J. (2016). Development and validation of an instrument for measuring individual motives for playing digital games. Media Psychol. 19, 101–125. doi: 10.1080/15213269.2014.902318

Denilson, B. T., Nouchi, R., and Kawashima, R. (2019). Does video gaming have impacts on the brain: Evidence from a systematic review. Brain Sci. 9:251. doi: 10.3390/brainsci9100251

Fredrickson, B. L., and Joiner, T. (2002). Positive emotions trigger upward spirals toward emotional well-being. Psychol Sci. 13, 172–175. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00431

Fu, W., Wang, C., Zou, L., Guo, Y., Lu, Z., Yan, S., et al. (2020). Psychological health, sleep quality, and coping styles to stress facing the COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. Transl. Psychiatry 10:225. doi: 10.1038/s41398-020-00913-3

Granic, I., Lobel, A., and Engels, R. C. M. E. (2014). The benefits of playing video games. Am. Psychol. 69, 66–78. doi: 10.1037/A0034857

Griffiths, M. D. (2009). The role of context in online gaming excess and addiction: Some case study evidence. Int. J. Ment. Heal. Addict. 8, 119–125. doi: 10.1007/S11469-009-9229-X

Hainey, T., Connolly, T., Stansfield, M., and Boyle, E. (2011). The differences in motivations of online game players and offline game players: A combined analysis of three studies at higher education level. Comput. Educ. 57, 2197–2211. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2011.06.001

Hamari, J., and Tuunanen, J. (2014). Player types: A meta-synthesis. Trans. Digital Games Res. Assoc. 1:13. doi: 10.26503/todigra.v1i2.13

Hanel, P. H. P., and Vione, K. C. (2016). Do student samples provide an accurate estimate of the general public? PLoS One 11:e0168354. doi: 10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0168354

Hartmann, T., and Klimmt, C. (2006). “The influence of personality factors on computer game choice” in Playing video games: Motives, responses, and consequences. eds. P. Vorderer and J. Bryant (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum), 115–131.

Hilgard, J., Engelhardt, C. R., and Bartholow, B. D. (2013). Individual differences in motives, preferences, and pathology in video games: The Gaming Attitudes, Motives, and Experiences Scales (GAMES). Front. Psychol. 4:608. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00608

Holl, E., Sischka, P. E., Wagener, G. L., and Melzer, A. (2024). The Motivation to Play Scale (MOPS) - introducing a validated measure of gaming motivation. Curr. Psychol. 43, 31068–31080. doi: 10.1007/s12144-024-06631-z

Iacovides, I., and Mekler, E. D. (2019). “The role of gaming during difficult life experiences” in CHI ‘19 (New York, NY: ACM).

Jansz, J., Avis, C., and Vosmeer, M. (2010). Playing the Sims2: An exploration of gender differences in players’ motivations and patterns of play. New Media Soc. 12, 235–251. doi: 10.1177/1461444809342267

Juth, V., Dickerson, S. S., Zoccola, P. M., and Lam, S. (2015). Understanding the utility of emotional approach coping: Evidence from a laboratory stressor and daily life. Anxiety Stress Coping 28, 50–70. doi: 10.1080/10615806.2014.921912

Kaczmarek, L. D., Misiak, M., Behnke, M., Dziekan, M., and Guzik, P. (2017). The pikachu effect: Social and health gaming motivations lead to greater benefits of Pokémon GO use. Comput. Human Behav. 75, 356–363. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2017.05.031

Kahn, A. S., Ratan, R., and Williams, D. (2014). Why we distort in self-report: Predictors of self-report errors in video game play. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 19, 1010–1023. doi: 10.1111/JCC4.12056

King, D. L., Delfabbro, P. H., Billieux, J., and Potenza, M. N. (2020). Problematic online gaming and the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Behav. Addict. 9, 184–186. doi: 10.1556/2006.2020.00016

Király, O., Billieux, J., King, D. L., Urbán, R., Koncz, P., Polgár, E., et al. (2022). A comprehensive model to understand and assess the motivational background of video game use: Gaming Motivation Inventory (GMI). J. Behav. Addict. 11, 796–819. doi: 10.1556/2006.2022.00048

Klimmt, C., and Hartmann, T. (2006). “Effectance, self-efficacy, and the motivation to play video games” in Playing video games: Motives, responses, and consequences. eds. P. Vorderer and J. Bryant (Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum), 133–145.

Knobloch-Westerwick, S. (2007). Gender differences in selective media use for mood management and mood adjustment. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 51, 73–92. doi: 10.1080/08838150701308069

Ko, C. H., and Yen, J. Y. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 on gaming disorder: Monitoring and prevention. J. Behav. Addict. 9, 187–189. doi: 10.1556/2006.2020.00040

Larsen, R. J. (2000). Toward a science of mood regulation. Psychol. Inq. 11, 129–141. doi: 10.1207/S15327965PLI1103_01

Li, X., and Zhang, B. (2020). “A preliminary network analysis on steam game tags: another way of understanding game genres” in Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on Academic Mindtrek (Tampere, Finland: ACM), 65–73. doi: 10.1145/3377290.3377300

López-Fernández, F. J., Mezquita, L., Griffiths, M. D., Ortet, G., and Ibáñez, M. I. (2020). The development and validation of the Videogaming Motives Questionnaire (VMQ). PLoS One 15:e0240726. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0240726

Luong, K. T., and Knobloch-Westerwick, S. (2021). “Selection of entertainment media: From mood management theory to the SESAM model” in The Oxford handbook of entertainment theory. eds. P. Vorderer and C. Klimmt (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

Mannell, R. C., Kaczynski, A. T., and Aronson, R. M. (2013). Adolescent participation and flow in physically active leisure and electronic media activities: Testing the displacement hypothesis. Soc. Leisure 28, 653–675. doi: 10.1080/07053436.2005.10707700

Manero, B., Torrente, J., Fernández-Vara, C., and Fernández-Manjón, B. (2017). Investigating the impact of gaming habits, gender, and age on the effectiveness of an educational video game: An exploratory study. IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies. 10, 236–246. doi: 10.1109/TLT.2016.2572702

Mehrabian, A. (1996). Pleasure-arousal-dominance: A general framework for describing and measuring individual differences in temperament. Curr. Psychol. 14, 261–292. doi: 10.1007/BF02686918

Meltzer, C. E., Naab, T., and Daschmann, G. (2012). All student samples differ: On participant selection in communication science. Commun. Methods Meas. 6, 251–262. doi: 10.1080/19312458.2012.732625

Morris, J. D. (1995). The self-assessment manikin: An efficient cross-cultural measurement of emotional response. J. Advert. Res. 35, 63–68.

Moy, P., Scheufele, D. A., and Holbert, R. (1999). Television use and social capital: Testing Putnam’s time displacement hypothesis. Mass Commun. Soc. 2, 27–45. doi: 10.1080/15205436.1999.9677860

Nabi, R. L., Torres, D. P., and Prestin, A. (2017). Guilty pleasure no more: The relative importance of media use for coping with stress. J. Media Psychol. 29, 126–136. doi: 10.1027/1864-1105/a000223

Oliver, M. B. (2003). “Mood management and selective exposure” in Communication and emotion: Essays in honor of Dolf Zillman. eds. J. Bryant, D. R. Roskos-Ewoldsen, and J. Cantor (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum), 85–106.

Oliver, M. B., Bowman, N. D., Woolley, J. K., Rogers, R., Sherrick, B. I., and Chung, M.-Y. (2015). Video games as meaningful entertainment experiences. Psychol. Pop. Media Cult. 4, 1–16. doi: 10.1037/ppm0000066

Oliver, M. B., and Raney, A. A. (2011). Entertainment as pleasurable and meaningful: identifying hedonic and eudaimonic motivations for entertainment consumption. J. Commun. 61, 984–1004. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2011.01585.x

Oravecz, Z., and Brick, T. R. (2019). Associations between slow- and fast-timescale indicators of emotional functioning. Social Psychological and Personality Science. 10, 864–873. doi: 10.1177/1948550618797128

Pallavicini, F., Ferrari, A., and Mantovani, F. (2018). Video games for well-being: A systematic review of the application of computer games for cognitive and emotional training in the adult population. Front. Psychol. 9:e02127. doi: 10.3389/FPSYG.2018.02127

Park, C. L., Russell, B. S., Fendrich, M., Finkelstein-Fox, L., Hutchison, M., and Becker, J. (2020). Americans’ COVID-19 stress, coping, and adherence to CDC guidelines. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 35, 2296–2303. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-05898-9

Park, J., Song, Y., and Teng, C.-I. (2011). Exploring the links between personality traits and motivations to play online games. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 14, 747–751. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2010.0502