- 1Design and Manufacturing Engineering, Jeonbuk National University, Jeonju, Republic of Korea

- 2College of Art and Design, Nanjing Forestry University, Nanjing, China

- 3School of Business, Qingdao University, Qingdao, China

- 4School of Media, Jiangsu Second Normal University, Nanjing, China

Introduction: Artificial intelligence (AI) technology empowers businesses to bypass designers and create brand logos directly through AI tools. We focus on the effectiveness of AI-generated logos in brand communication when AI acts as an autonomous designer. Relevant research on visual attention has demonstrated the beneficial impact of innovation and relevance on brand communication. However, the combined impact of innovation and relevance on users’ sustained attention in AI-generated logos remains unclear.

Methods: To address this gap, this research demonstrates the synergistic effect of innovation and semantic relevance on users’ sustained attention under different creator type through two studies.

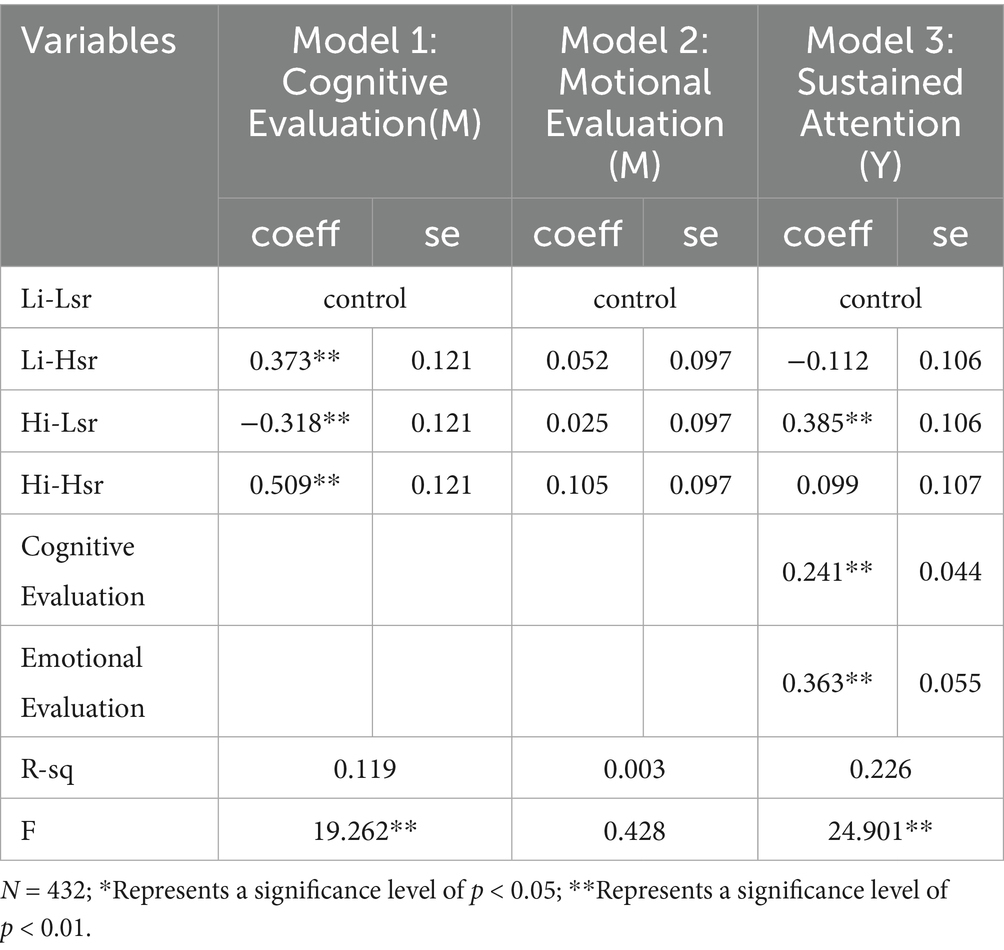

Results: Specifically, Study 1 explored the synergistic effect of innovation and semantic relevance on cognitive evaluation, emotional evaluation, and sustained attention using 434 questionnaires, and also observed the mediating effect of cognitive evaluation and emotional evaluation. The mediation regression model found that the synergistic effect of innovation and relevance significantly affected users’ cognitive evaluation (F(3,428) = 19.262, MSE = 0.785, p < 0.001) and sustained attention (F(3,428) = 4.197, MSE = 0.737, p < 0.05), with cognitive evaluation playing a mediating effect. Building on these findings, Study 2 verified the moderating effect of creator type by employing 54 valid eye-tracking samples. The results indicate that disclosure of creator type significantly moderates the degree of users’ cognitive evaluation and sustained attention.

Discussion: When the creator type was disclosed as AI, logos with high innovation and semantic relevance tended to receive sustained attention, and users exhibited more positive cognitive engagement. In contrast, when the creator type was disclosed as human, logos with weak semantic relevance received more sustained attention. These findings provide a basis for integrating AI tools and human creativity in future design.

1 Introduction

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is transforming our way of working with significant strides in using AI in design (Verganti et al., 2020). According to IDC FutureScape (2023) forecast, by 2025, over 40% of the core expenditures of the world’s top 2000 companies will be directed toward AI-related projects, establishing AI as a key driver of product and process innovation. AI programs are redefining the rules of creation, enhancing design efficiency, and transitioning the design process from “machine-assisted designer creation” to “designer-assessed machine creation” (Wu et al., 2024). The rapid development of AI has broken traditional industry barriers, enabling untrained individuals to participate in the design process easily. As Renner and Chaban (2024) claim: “With creative agents, anyone can become a designer, artist, or producer.” With simplified AI tool usage standards, more companies bypass traditional designers and generate design content directly via AI tools. By merely inputting their core keywords into the AI program, companies can now select from dozens of generated options, significantly boosting design efficiency and demonstrating the potential of AI to replace human designers.

Major technology companies such as Google, Adobe, and NVIDIA have recognized the potential of applying generative AI to brand design. They have developed user-friendly AI tools to reduce barriers to entry for AI in design. However, integrating generative AI into brand design still faces challenges. AI-generated content (AIGC) relies on existing training data and algorithmic approaches, it lacks an intrinsic understanding of real content and is prone to significant information distortion (Sun et al., 2024). Brand design should take into account the cognitive structure and cultural heterogeneity of potential users to ensure that AIGC communicates effectively between the brand and users and avoids providing misleading information. Multiple studies have compared the impact of AIGC and human-created content on user perception, but findings on the effectiveness of AIGC are generally polarized (Li et al., 2023; Ozdemir et al., 2023; Park et al., 2024; Lian et al., 2024). Nevertheless, AI’s advanced language comprehension capabilities and powerful image processing capabilities still contribute to the efficient generation of personalized brand logos. Several studies have proposed computer-aided methods based on generative adversarial networks (GANs) to enhance logo design (Mino and Spanakis, 2018; Ter-Sarkisov and Alonso, 2021; Wang, 2024; Zhang, 2024). Other studies have focused on addressing challenges related to AIGC quality detection and intellectual property, including authenticity detection of logo graphics (Pinitjitsamut et al., 2021), quality of scalable vector graphics (Mateja et al., 2023), and detection of synthetic images (Ghiurău and Popescu, 2024).

AI technology is a tool for businesses to accelerate creative generation, but it also brings risks of semantic deviation and content homogeneity. In the AI-driven design, the semantic deviation and content homogeneity of AI-generated logos (AIGLs) can lead to unexpected losses. As a representative symbol of brand equity, logos reflect users’ long-term attachment to a brand (Keller, 1993). Previous research suggests a positive impact on users’ brand perception and emotional experience of semantic distance (De Lencastre et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2024), brand symbol consistency (Salgado-Montejo et al., 2014), interaction strategies (Ma et al., 2022; Su et al., 2019), and novelty experiences (Van Noort et al., 2012; Walsh et al., 2010; Shin et al., 2017). Semantic relevance is the core of information communication. High relevance increases the speed of understanding and classification, thereby enhancing trust, memory, and functional fit (Demirbilek and Sener, 2003; Bao et al., 2008; Choi and Kang, 2013). Childers and Jass (2002) noted in a study on brand perception and consumer memory that the more closely semantic cues are related to advertising promotions, the higher the memorability. Wang and Lin (2021) explored the semantic relevance of product appearance from the perspective of cognitive load, finding that high semantic relevance improves the fluency of product information communication. Samu and Shanker Krishnan (2010) focusing on brand names, argued that brand information with strong semantic relevance can improve users’ memory and brand selection efficiency. Innovation is a measure of brand differentiation in design form, and is often considered by marketers as a source of competitive advantage (Beverland, 2005; Beverland et al., 2010). While the beneficial effect of innovation on brands has been widely discussed, He and Luo (2017) found that excessive novelty increases the cost of understanding, raising the threshold for design acceptance and, in turn, reducing the communication value. Their research urges designers to identify the “sweet spot” of novelty. That has indeed promoted academic attention to novelty and innovation. Collectively, innovation and semantic relevance are key indicators for enhancing users’ esthetic perception and design effectiveness. While the independent impact of innovation and semantic relevance has been widely explored by brand researchers, few have considered them as a pair of interrelated observational indicators. In fact, there is a complementary relationship between innovation and semantic relevance, but existing research still lacks an understanding of their synergistic effect. Therefore, our research will focus on the synergistic effect of innovation and semantic relevance on brand design.

In the era of intense scrutiny in AI technology, AIGLs have significantly improved enterprise design efficiency in terms of time cost and production speed, which explains the current research focus on AI technology (Jiao and Cao, 2024; Sun and Liu, 2025; Wang and Chen, 2024). Numerous reviews and reports have prioritized efficiency as the primary value proposition of AIGC (Rizzi and Bertola, 2025; Al Naqbi et al., 2024; Heigl, 2025). However, as a symbol of future brand equity, the hidden risks of AIGLs quality on brand communication effectiveness and user perception are often overlooked. From a long-term perspective of value creation, increased efficiency may have the side effect of shallow processing and distracted attention (Gerlich, 2025). Systematic research on AIGLs in maintaining esthetic perception and sustained attention in marketing communications is still rare and lacks empirical evidence. Existing research tends to focus on the beneficial impact of AI technology in improving design efficiency (Wu et al., 2025; Cao and Duan, 2024). Few studies have examined the impact of AIGLs on users’ sustained attention and esthetic perception during actual communication from the perspective of designers.

Consequently, this study begins with the question of “Whether AI has the Potential to Serve as an Independent Designer” and explores the impact of AIGLs on user perception and sustained attention from the perspective of differentiated creator type. Furthermore, to provide practical design advice to AI developers interested in promoting the quality of AIGLs and to facilitate its adoption in the brand market, we use innovation and semantic relevance as indicators of logo validity, further examining the synergistic effect of innovation and semantic relevance on user perception and sustained attention in AIGLs.

In summary, this research takes innovation and semantic relevance as independent variables to explore their impact on user perception and sustained attention. We considered cognitive evaluation and emotional evaluation as mediating variables and hypothesized that the creator type (AI and human) would have a moderate effect in this process to determine the differences in user perception and sustained attention to AIGLs. To this end, we conducted two studies. In Study 1, we used a questionnaire survey to examine the synergy of innovation and semantic relevance on users’ sustained attention, while also testing the mediating effects of cognitive evaluation and emotional evaluation in this process. The results showed that the synergy of innovation and semantic relevance positively influenced sustained attention. Cognitive evaluation significantly mediated the relationship between the independent variables and sustained attention. In Study 2, we employed eye-tracking tests to verify the moderate effects of creator type. The findings confirmed the moderate effects: when the creator was AI, users showed greater sustained attention toward logos with high innovation and high semantic relevance. Conversely, logos with low innovation received more sustained attention when the creator was human.

Our research differs from the existing literature in three ways. First, we evaluate the synergistic effect of innovation and semantic relevance on brand communication in brand logo design. While previous research has largely explored the separate effects of innovation and semantic relevance, we are interested in understanding the combined effect of innovation and semantic relevance on the communication effectiveness of brand logos in sustained attention and user perception. Secondly, we considered AI as an independent designer and evaluated the potential for companies to independently generate meaningful brand logos using AI tools without designer intervention. We also used creator type as an observation variable to compare users’ trust in human and AI creative agents, finding that users have a strong wait-and-see attitude toward AI as a creative agent. This provides theoretical evidence for future research exploring the relationship between AI creativity and human trust and acceptance. Finally, combining the synergistic effect of innovation and semantic relevance, we highlight the cognitive biases caused by creator type in brand identity design. Users are more receptive to AIGLs with high semantic relevance and are more likely to pay attention to human-created logos with high innovation. This research explores the boundaries of user perception of creative agency and provides some reference evidence for explaining how humans perceive AI creators and whether they are willing to trust AI creators. From the perspective of design cognition, the involvement of AI changes the design construction process, and the cognitive adaptation between designers and AI algorithms has become a key issue in human-computer collaboration in design.

2 Literature review and hypotheses

2.1 Innovation and semantic relevance in AIGLs

AI technology has sparked a stir on social media, and related research on how AIGC can aid brand marketing has also been widely discussed. However, few studies have treated AI as an independent designer and explored its role in brand logo research. Logo design is a meticulous task that requires the integration of various design concepts and repeated adjustments. With the widespread use of AI tools, businesses are choosing to bypass designers and use AI tools to generate brand logos directly. Without the screening process performed by designers, the effectiveness of AIGLs for brand marketing remains unclear. AI algorithms bring diversity and uniqueness to logo design, but they also present challenges. The Diffusion Model, a predominant model in current image generation technology, teaches the computer to use an original noisy image and progressively remove extraneous noise to produce a clear image. The U-Net Model facilitates image segmentation in this process, extraneous noise is segmented based on feature prompt words to ensure the final image aligns with initial specifications (Jiao and Zhao, 2019; Croitoru et al., 2023). The model-driven image generation method greatly improves the efficiency of image production. However, the inherent randomness of AI models in the image generation process may prevent AIGLs from reflecting the underlying concepts of a brand and producing logos that are inconsistent with the brand’s original intent, thereby compromising its practical applicability (Kreafolk, 2023).

Although AIGC demonstrates significant advantages in improving creative efficiency (Lin et al., 2024; Lou, 2023; Huang et al., 2024), existing research lacks a systematic understanding of AIGC quality assessment. Many researchers attribute the value of AIGC primarily to improved production efficiency, but rarely examine user perception of content quality under these high-efficiency models (Gerlich, 2025; Georgiou, 2025). This efficiency approach offers some superficial benefits, but it undermines the deeper value of generated content, leading users to question AIGC (Li et al., 2025; Li et al., 2025). As a countermeasure, some studies have examined AIGC from the perspectives of innovation and semantic relevance (Wang et al., 2024; Liu et al., 2024). Some researchers have confirmed the potential of AI in creativity and novelty through empirical research (Guzik et al., 2023; Wingström et al., 2024). Other researchers criticize that AI relies on pre-set algorithms and datasets to recombine existing elements through machine learning, lacking the spontaneity of true originality (Koivisto and Grassini, 2023; Runco, 2023; Ding and Li, 2025). Understanding how AIGLs influence user perception of innovation will help marketers make better brand promotion decisions and expand brand influence.

Semantic relevance and semantic deviation are relative concepts. McDougall et al. (1999) identified five key characteristics of logos based on user perception: “concreteness, complexity, meaningfulness, familiarity, and semantic distance.” Semantic distance, the measure of a design’s connection to the concept it represents, is critical in evaluating a logo’s effectiveness in communication (Miceli et al., 2014; Van Grinsven and Das, 2016; Silvennoinen et al., 2017). Humans can interpret complex semantics and identify multiple semantic connections within the same design element based on context. In contrast, AI’s understanding of semantics is often superficial, limited to pattern matching with restricted capability to handle complex semantics. Research on semantic relevance within AIGC has primarily focused on the field of semantic communication. Liu et al. (2024) evaluated the semantic relevance of AIGC at the level of factual accuracy or grammatical coherence. However, for the visual design, this superficial semantic coherence is insufficient to support AIGC in conveying deeper meaning through visual design, because graphic semantics and textual semantics are distinct signifying systems. Textual semantics is rational cognition based on consensus and is characterized by certainty and logic. In contrast, graphic semantics is intuitive and perceptual cognition, characterized by polysemy and ambiguity. In traditional brand design, designers gather brand knowledge and convey semantics to viewers through visual design. Viewers are more likely to interpret more meanings from graphics. This ambiguity in graphic semantics enables designers to create more innovative brand images. In the AIGC generation process, whether the algorithmic model fully understands the design intent and accurately conveys meaning through graphics has not received sufficient attention in previous research.

In summary, innovation and semantic relevance are ways to enhance users’ positive perception of content quality. A brief review of previous related work can help us clarify the concepts of innovation and semantic relevance in brand design and avoid confusion with similar concepts in other disciplines.

2.2 The interactive effect of innovation and semantic relevance on sustained attention

Sustained attention is a necessary means of increasing brand exposure and establishing brand awareness in the emerging brand (Keller, 1993). Numerous studies have demonstrated that innovation and semantic relevance positively affect users’ sustained attention (Radford and Bloch, 2011; De Groot et al., 2016; Shen and Lin, 2021; Sun and Liu, 2025). Semantic relevance corresponds to the information communication function, determining whether the brand accurately conveys its core meaning through its graphics and builds a consistent brand semantic network (Bao et al., 2008; Colladon, 2018; Batra, 2019). Innovation corresponds to the esthetic experience function, determining whether the brand create positive emotional resonance through its graphic (Kapferer, 1994; Beverland, 2005). In other words, information communication function satisfies users’ cognitive needs for the brand and enhances their continued engagement with the brand (Van Grinsven and Das, 2016; Huang et al., 2021). The esthetic experience function satisfies users’ esthetic needs for the brand and enhances their emotional evaluation of the brand. Our research suggests that cognitive and esthetic needs are mediated by the synergistic effect of innovation and semantic relevance. Specifically, while semantic relevance is beneficial for enhancing an information communication function, excessive semantic relevance can compromise associative space for graphics. Meanwhile, innovation is beneficial for enhancing esthetic experience function, but excessive innovation leads to semantic deviation. While innovation and semantic relevance are complementary, excessive innovation and weakens semantic relevance, making it difficult for users to understand the design intent weakening their sustained attention. Overemphasizing semantic relevance inhibits innovation and reduces users’ interest. However, few literatures focus on the interactive effects of innovation and semantic relevance on users’ sustained attention from an empirical research perspective. In fact, there exists an inherent tension between innovation and semantic relevance: excessive innovation may dilute semantic relevance, complicating users’ understanding of the design’s purpose and diminishing their sustained attention. Conversely, excessive emphasis on semantic relevance can stifle innovation, diminishing users’ interest. To a certain degree, innovation and semantic relevance maintain a complementary yet competitive relationship, where an increase in one could potentially reduce the efficacy of the other. This does not mean that innovation and semantic relevance cannot coexist. When innovation and semantic relevance are maintained at a moderate balance, they can work in synergy to jointly enhance a brand’s sustained appeal. This study first seeks to identify strategies to balance these elements in logo design to optimize their benefits and enhance users’ sustained attention.

To investigate this dynamic, the study established two levels of innovation and two levels of semantic relevance, denoted as High (H) and Low (L), respectively. High innovation is labeled Hi; low innovation is labeled Li; high semantic relevance is Hsr; low semantic relevance is Lsr. Consequently, four interaction terms are formulated: high innovation × high semantic relevance (Hi-Hsr); high innovation × low semantic relevance (Hi-Lsr); low innovation × high semantic relevance (Li-Hsr); low innovation × low semantic relevance (Li-Lsr). The following hypotheses are proposed:

H1: The interactive effect of innovation and semantic relevance impacts users’ sustained attention.

H1a: High innovation (Hi-Hsr / Hi-Lsr) positively influences users’ sustained attention.

H1b: High semantic relevance (Hi-Hsr / Li-Hsr) positively influences users’ sustained attention.

2.3 The mediating effect of perceived evaluation

The outcomes of user perception evaluations are crucial for designers to anticipate users’ reactions and make necessary modifications to designs. In logos designed by humans, semantic relevance significantly enhances cognitive outcomes. Logos with pronounced semantic relevance are more likely to attract visual attention and promote sustained users’ engagement (Zhang et al., 2024). Moderate innovation has also been shown to affect user perception in a beneficial way. In a 2016 study, Pappu and Quester (2016) examined consumer perceptions of innovative brand design and their effect on brand loyalty, finding that innovative brand design improves brand favorability by eliciting positive emotional responses, which further foster loyalty.

Research on user perception evaluation has traditionally concentrated on cognitive and emotional aspects. Cognitive evaluation involves users’ understanding and memory. When users correctly understand and remember a brand logo, the design is considered effective. Brand equity theory states that when user perception are consistent with their expectations, their preference and loyalty to a brand will increase (Keller, 1993). Research has confirmed the impact of innovation and semantic relevance on sustained attention. Research on emotional responses to advertising has shown that such reactions significantly moderate users’ attitudes toward both the ad and the brand (Holbrook and Batra, 1987). Van der Lans et al. (2008) suggest that a brand characterized by perceived solidity can enhance sustained attention and drive purchasing behavior. Although the beneficial impacts of innovation and semantic relevance on users’ cognition and emotion are established, it remains uncertain whether their interaction in AIGLs similarly influences user perception. Therefore, this study posits that both innovation and semantic relevance affect user perception evaluations. The following hypotheses are proposed:

H2: The interactive effect of innovation and semantic relevance impacts users’ cognitive evaluation.

H2a: High semantic relevance (Hi-Hsr / Li-Hsr) positively impacts users’ cognitive evaluation.

H3: The interactive effect of innovation and semantic relevance impacts users’ emotional evaluation.

H3a: High innovation (Hi-Hsr / Hi-Lsr) positively impacts users’ emotional evaluation.

The Dual-Process Model can clearly explain the influence of cognitive and emotional evaluation on brand communication. According to the Dual-Process Model (Kahneman, 2011), individuals’ information processing of external stimuli relies on two systems: the rapid emotional response system and the slow cognitive processing system. The Dual-Process Model explains how consumer behavior and decision-making are generated through information processing from two perspectives (Gawronski et al., 2013). The rapid emotional response system primarily relies on gut reactions, representing subconscious and automatic responses to external stimuli. The slow cognitive processing system evaluates through conscious analysis and reasoning. User perception of the innovation of a brand logo activates the emotional response system, triggering discrete emotions such as pleasure, surprise, and approval, thereby increasing their sustained attention to the brand. User perception of the relevance of brand information activates the cognitive processing system, which then processes the brand information in a refined manner. Furthermore, according to Esthetic Fluency Theory (Reber et al., 2004), an individual’s “perceptual fluency” stimulates positive emotions and influences esthetic judgments. When AIGLs are semantically coherent and formally innovative, they can simultaneously enhance information processing fluency and emotional pleasure responses. This supports the dual mediating mechanisms through which AIGLs influence brand perception.

In summary, based on the dual-process model and esthetic fluency theory, this study uses cognitive evaluation and emotional evaluation as dual mediating variables to examine the impact of these two pathways on users’ sustained attention. The following hypotheses are proposed:

H4: User perception evaluation (cognitive and emotional) affects sustained attention.

H4a: Cognitive evaluation mediates the synergistic effect of innovation and semantic relevance on sustained attention.

H4b: Emotional evaluation mediates the synergistic effect of innovation and semantic relevance on sustained attention.

2.4 The moderator effect of creator type

The idea that machines can generate creative and informative content raises concerns about the human-machine dynamic, such as text and artwork (Grassini and Koivisto, 2024). With the widespread application of AI technology in brand design, consumers are increasingly concerned about who created the work. Numerous studies have reported biases against AI designs, arguing that AI lacks the emotional depth of human designs (Magni et al., 2024). Waddell (2018) reported that machine authorship negatively impacts content credibility compared to human authors. Graefe and Bohlken (2020) found that while AI-generated news can be perceived as credible, it receives lower ratings for quality and readability. According to Grassini and Koivisto (2024), in the field of art, people tend to give negative evaluations to AI-generated artworks, which shows that people have a negative bias toward AI. Conversely, other studies have shown that when people recognize AI’s high efficiency, their evaluations may shift positively (Shaikh and Cruz, 2023). Chaisatitkul et al. (2024) found that consumers have positive views of AI-generated content. Previous research has shown that user perceived trustworthiness of design works influences their cognitive processing pathways and emotional responses to them (Newman and Bloom, 2012). However, existing literature lacks a systematic theoretical explanation of how creator type influences the relationship between AIGC and user perception.

Therefore, this study draws on source credibility theory (Hovland et al., 1953) to explain the psychological impact of AI as a virtual creator on users during brand communication. Source credibility theory has received widespread attention in the marketing field (Metzger et al., 2003; Pornpitakpan, 2004) and used to examine the effectiveness of celebrity endorsements. Communication researchers also tend to apply this theory to compare the credibility of different media channels (Johnson and Kaye, 2009). Previous research on source credibility usually links information source credibility with information accuracy. Ohanian (1991) defines credibility as “the consumer’s trust in a source that presents information objectively and honestly.” In this study, the source of credibility refers to the creator type. We specifically focus on the impact of AI creators’ credibility when using AI virtual creators as content sources. Human creators are generally considered to have higher intentionality and sociality, and are believed to reflect true esthetic judgments. In contrast, the output of AI creators is more attributed to algorithms and efficiency and is often seen as lacking subjective intention and emotional expression. When users are aware that an AI has designed a logo, its excessive innovation may be perceived as unrealistic or too risky, and diminishing their sustained attention. However, if the semantic relevance is high, users may be more accepting due to trust in AI’s comprehensive knowledge. In contrast, human-created innovations tend to be more favorably received, even when semantic relevance is low.

While researchers have extensively discussed the relationship between AI technology and human trust, further research is needed on the differences in user evaluations of AIGLs and human-created logos. Drawing on source credibility theory, this study proposes that users form different psychological attributions based on the creator type, which influences their credibility mechanisms in design works. This credibility mechanism modulates users’ cognitive and emotional evaluation toward AIGLs, ultimately mediating their sustained attention to it. The following hypotheses are proposed:

H5: Creator type moderates the interaction between innovation and semantic relevance.

H5a: With AI as the creator, high innovation (Hi-Hsr / Hi-Lsr) negatively impacts sustained attention.

H5b: With AI as the creator, high semantic relevance (Hi-Hsr / Li-Hsr) positively impacts sustained attention.

H5c: With a human as the creator, high innovation (Hi-Hsr / Hi-Lsr) positively impacts sustained attention.

H5d: With a human as the creator, high semantic relevance (Hi-Hsr / Li-Hsr) negatively impacts sustained attention.

3 Study 1

The first objective of this study is to investigate the interactive effects of innovation and semantic relevance on users’ sustained attention to provide evidence supporting H1. The second objective is to examine the mediating effect of cognitive evaluation on sustained attention to provide evidence supporting H2. The third objective is to examine the mediating effect of emotional evaluation on sustained attention, providing evidence to support H3.

3.1 Experimental materials

We invited three brand designers to collect logo proposals based on specific criteria. Ultimately, we collected 25 logo images to form the human-created logo database (see Supplementary Figure S1). We limited the logo features to control the confounding factors according to McDougall’s theory. Other logo features were controlled at the same level except for semantic relevance to avoid experimental errors caused by irrelevant variables (Collaud et al., 2022; Mu et al., 2022). The AIGLs database was created by designers using ChatGPT, following the process outlined below.

Step 1: ChatGPT was used to convert topic keywords into prompt words suitable for Midjourney (see Supplementary Table S1).

Step 2: In Midjourney, the “/imagine” command was employed to input prompt words and generate 4 images per cycle, totaling 60 images after 15 cycles.

Step 3: These 60 images were grouped by similarity into 18 clusters. Designers then voted on the image that best met esthetic and practical criteria for this experiment from each group, resulting in 18 selected logo images.

Step 4: The 18 images were input into Midjourney to generate descriptive prompt words using the “/describe” command. After eliminating duplicates, the remaining prompts were refined and reordered in ChatGPT to fit Midjourney’s input format.

Step 5: The revised prompt words were re-input into Midjourney, and the process was repeated to generate 60 images, from which designers selected 14 logos through discussion.

Step 6: The logos chosen in the two rounds were merged to create a database of 32 AIGLs images.

3.1.1 Selection of experimental materials

The logo images were scrutinized using four interaction levels of innovation and semantic relevance (Hi-Hsr /Hi-Lsr / Li-Hsr / Li-Lsr) as selection criteria.

Step 1: Each database was screened to remove overly complex, concrete, or three-dimensional logos.

Step 2: 6 designers formed an evaluation team to review and select the most esthetically pleasing logos from both databases, ultimately retaining 16 logos (see Supplementary Figure S2).

Step 3: 40 design professionals assessed these 32 logos, ranking them based on innovation and semantic relevance using an electronic questionnaire.

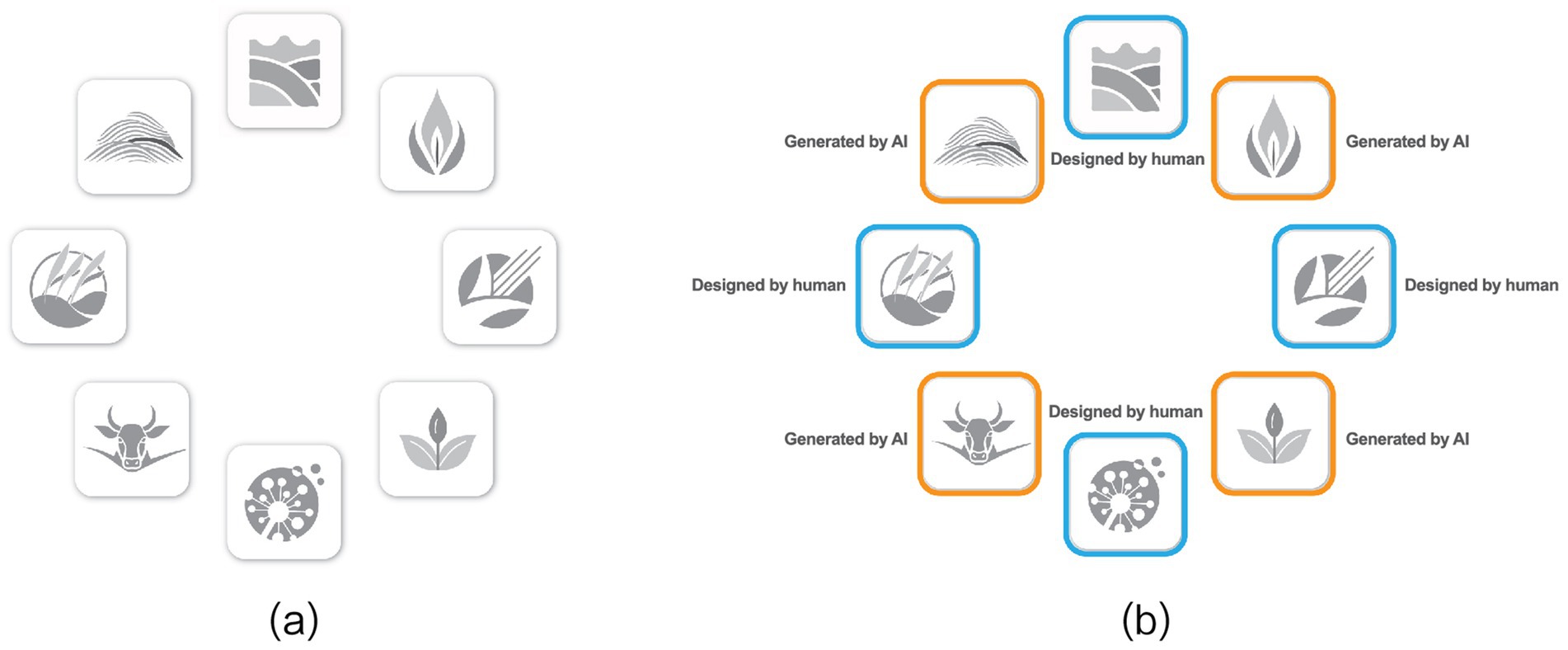

Step 4: Logos were scored and ranked according to their innovation and semantic relevance, selecting 8 logos representing each category as target experimental materials (see Figure 1).

Based on the ranking and evaluation results of 32 logos by 40 design professionals, we used a ranking assignment method to rank the experimental materials based on their innovation and semantic relevance. We selected the experimental materials with the high innovation and semantic relevance from the AIGLs and human-created logos and coded them as Ai-Hi-Hsr and Human-Hi-Hsr, respectively. We also selected the experimental materials with the high innovation and low semantic relevance and coded them as Ai-Hi-Lsr and Human-Hi-Lsr, respectively. Similarly, we coded the experimental materials with Ai-Li-Hsr, Human-Li-Hsr, Ai-Li-Lsr, and Human-Li-Lsr, respectively. The coding results are shown in Table 1. These coded logos will serve as categorical independent variables in subsequent study.

3.1.2 Adjustment of experimental materials

Existing research has identified logo design features that influence user attention, including graphic color (Lin et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2021; Shen and Lin, 2021; Huang et al., 2023; Yang et al., 2024), background color and background area (Lewandowska and Olejnik-Krugly, 2021; Shao et al., 2024), and graphic saturation (Yu and Ouyang, 2024; Deng et al., 2022). To eliminate these differences, this study used Photoshop to uniformly adjust the color, layout, and size of the logo images. To standardize the graphics presentation, each image was set on a rounded rectangle background with 230 pixels of rounded corners and dimensions of 830×830 pixels. All text was removed, leaving only the graphic elements converted to grayscale. The logo was removed, leaving only the graphic elements converted to grayscale. That was centered within this space, with a margin of 160 pixels between the graphic and the background edge (see Figure 2).

3.2 Experimental procedure

This study focused on the interaction between innovation and semantic relevance (independent variable), cognitive evaluation (mediator 1), emotional evaluation (mediator 2), and sustained attention (dependent variable) (see Figure 3). The synergistic effect between innovation and semantic relevance is a categorical variable and is structured into four groups: high innovation × high semantic relevance (Hi-Hsr), high innovation × low semantic relevance (Hi-Lsr), low innovation × high semantic relevance (Li-Hsr), and low innovation × low semantic relevance (Li-Lsr). Cognitive evaluation, emotional evaluation, and sustained attention were continuous variables, collected through a questionnaire survey. The three items in cognitive evaluation were based on the Need for Cognition Scale (NCS) by Cacioppo and Petty (1982), measuring users’ tendency to deeply process information. The three items in emotional evaluation were based on the PAD Emotion Scale by Mehrabian (1995), measuring users’ emotional states across the three dimensions of pleasure, arousal, and dominance. The three items on sustained attention were based on the Attention Self-Report Scale of Chen et al. (2023). Furthermore, our independent variable is represented by coded experimental materials. To verify the validity of the independent variable (experimental materials), we also included corresponding items on innovation and semantic relevance in the questionnaire. This aimed to further verify the credibility of the coding of the experimental materials through participant evaluation. All items in the questionnaire are measured using a five-point Likert scale. The questionnaire shown in Supplementary Table S2.

To conduct the questionnaire survey, we set up a repeated measures experiment. Since our independent variables were grouped by experimental materials, all participants were asked to carefully view the experimental materials and complete the corresponding questionnaires for each of the eight experimental materials. To prevent repeated measurements from causing participant fatigue and affecting data accuracy, we carefully controlled the number and duration of exposure to the experimental materials. This study has been approved by the relevant ethics committee (2025–03–018-002). The survey was started after confirming that the participants understood and agreed to the experimental content.

This study distributed an offline questionnaire survey at Jeonbuk National University in Jeonju, South Korea, and Shandong Jianzhu University in Jinan, China. A total of 480 questionnaires were distributed, and 46 invalid samples were eliminated due to incorrect completion. The reasons for invalid samples include filling out the questionnaire without checking the experimental materials, the questionnaire not matching the experimental materials, and filling out the questionnaire in less than 10 s. A total of 434 valid samples were retained (China = 52.6%, South Korea = 48.4%, male = 51.8%, female = 48.2%; age range = 20–48 years). To ensure sample quality, we only recruited participants aged between 20 and 50 who had some understanding of brand knowledge and AI technology. This study on culturally similar groups supports the applicability of these findings to Asian businesses that are interested in using AIGLs.

3.3 Analysis

3.3.1 Robustness checks

Table 2 presents the results of the robustness checks for the questionnaire. The Cronbach’s Alpha ranged from 0.601 to 0.812, all exceeding the threshold of 0.6, indicating internal consistency among the dimensions. The KMO value was 0.756, and Bartlett’s sphericity test results were statistically significant (p < 0.001). The cumulative percentage of explained variance was 72.568%, which was satisfactory, indicating that the scale had robust feasibility. The results allow the dimensions to be divided into three parts: cognitive evaluation, emotional evaluation, and sustained attention.

The robustness checks of the materials were examined by one-way ANOVA. Table 3 shows significant differences in users’ innovation evaluations of the experimental materials, F (7, 182) = 10.538, p < 0.001. For each creator type, the innovation evaluations of Hi-Hsr and Hi-Lsr were significantly higher than those of the other two groups. Similarly, significant differences were found in users’ evaluation of semantic relevance, F (7, 182) = 13.367, p < 0.001, with Hi-Hsr and Li-Hsr scoring significantly higher than the other groups. These results indicate that the interactive effects of innovation and semantic relevance exhibited significant differences across the eight images, confirming the validity of the experimental materials.

3.3.2 Results analysis of the questionnaire survey

ANOVA was used to examine the interactive effects on user perception and sustained attention in terms of innovation and semantic relevance. All data sets demonstrated homogeneity of variance. The results in Table 4 indicate that the four interaction terms had significant differences in users’ sustained attention [F (3,428) = 4.197, MSE = 0.737, p < 0.05] and cognitive evaluations [F (3,428) = 19.262, MSE = 0.785, p < 0.001]. In contrast, the differences in emotional evaluations were not significant. H1 and H2 were supported, while H3 was rejected. Further post hoc comparisons revealed that under high innovation (Hi-Hsr / Hi-Lsr), the logo had a significantly greater effect on sustained attention than under low innovation (Li-Hsr / Li-Lsr), while high semantic relevance did not have a significant effect on sustained attention. These findings support hypothesis H1a, while H1b was rejected. Additionally, high semantic relevance (Hi-Hsr / Li-Hsr) had a significantly greater impact on cognitive evaluation than low semantic relevance (Hi-Lsr / Li-Lsr). H2a was supported. Surprisingly, under conditions of low semantic relevance, low innovation logo (Li-Lsr) improved users’ cognitive evaluations.

Subsequently, the process macro model 4 was used to verify the mediating effect of user perception (cognitive evaluation/emotional evaluation) (see Table 5). Model 1 results indicate that the interaction effect of innovation and semantic relevance on cognitive evaluation was significant. Using Li-Lsr as a control, high semantic relevance (Hi-Hsr / Li-Hsr) had a positive effect on cognitive evaluation. Under low semantic relevance, logos with high innovation hurt cognitive evaluation. That was consistent with the ANOVA results, enhancing the robustness of the findings. Model 2 had no significant effect on emotional evaluation. After introducing the mediating variable in Model 3, the model’s explanatory power improved (R2 = 0.266), and there was no multicollinearity among the variables (VIF = 1.120). The results indicate that cognitive evaluation (B = 0.241, p < 0.01) and emotional evaluation (B = 0.363, p < 0.01) had a significant positive impact on sustained attention. H4 were supported. Comprehensive analysis of regression models with multiple categorical independent variables revealed that the synergistic effect of innovation and semantic relatedness significantly influenced cognitive evaluation and sustained attention, but had no effect on affective evaluation. Both cognitive and affective evaluations significantly affected sustained attention, indicating that mediating variables (cognitive and affective evaluations) could predict the dependent variable (sustained attention). However, the mediating mechanism of emotional evaluation was not activated. The mediating effect of cognitive evaluation was confirmed. H4a was supported, while H4b was rejected (see Figure 4).

At this stage, by manipulating four levels of interaction items and two mediating variables, we demonstrated the interaction effect of innovation and semantic relevance on sustained attention, as well as the mediating effect of user perception (cognitive/emotional). Specifically, highly innovative logos were more likely to attract sustained attention, and this process was not affected by user perception. Logos with high semantic relevance enhance users’ cognitive evaluations and further attract more sustained attention. Furthermore, we explored the mediating effect of user perception (cognitive evaluation and emotional evaluation). Specifically, cognitive evaluation played a significant mediating effect in the interactive effect of innovation and semantic relevance on sustained attention, while emotional evaluation did not. In other words, cognitive evaluation more effectively regulated users’ sustained attention than emotional evaluation. This result is consistent with previous research. The attention resource control model states that attentional resources are limited (Smallwood et al., 2006). When individuals need to maintain sustained attention, they must allocate cognitive resources efficiently and inhibit task-irrelevant thoughts or automatic responses (Thomson et al., 2015). Sustained attention is highly correlated with cognitive resource allocation, task monitoring, and alertness (Sarter et al., 2001; Robison et al., 2022). This pattern of attentional engagement is inherently consistent with the cognitive processing system in the dual-process model. In the process of brand communication, cognitive processing is initiated through cognitive evaluation, which is information-intensive and non-intuitive. In contrast, emotional evaluation is an intuitive, automatic response characterized by rapid activation but limited ability to sustain deep processing. Users’ emotional fluctuations toward brand logos often lead to fleeting attention. Compared to cognitive evaluation, emotional evaluation relies less on working memory and attentional resources, dimensions that are crucial for sustained attention. The results of Study 1 provide empirical theoretical support for understanding the potential mechanism by which brand logos attract users’ sustained attention, and extend related research on attention resource allocation and user perception evaluation. However, these results did not address the potential impact of creator type on sustained attention. Therefore, Study 2 explored the moderating effect of creator type on sustained attention using eye-tracking.

4 Study 2

The results of Study 1 provide supporting evidence for the validity of the mediating model. However, it did not discuss whether users’ attention to the experimental materials would change when the creator type was disclosed. Therefore, Study 2 used eye-tracking tests to validate the moderating effect of creator type on sustained attention, providing evidence to support H5. In this study, we divided the experiment into two stages: the pre-test and the post-test, based on whether the creator type was disclosed.

4.1 Experimental materials

Study 2 continued to use the experimental materials of Study 1. The difference was that Study 1 did not use the creator type as the division standard of the experimental materials, but only observed the relevant impact of the four interaction terms in the synergistic effect of innovation and semantic relevance. In order to reveal the moderating effect of creator type, Study 2 further divided the experimental materials into 8 groups, including AIGLs with high innovation and high semantic relevance (Hi-Hsr-Ai), AIGLs with high innovation and low semantic relevance (Hi-Lsr-Ai), AIGLs with low innovation and high semantic relevance (Li-Hsr-Ai), AIGLs with low innovation and low semantic relevance (Li-Lsr-Ai), and four human-created logos corresponding to the same interaction levels (Hi-Hsr-Human, Hi-Lsr-Human, Li-Hsr-Human, Li-Lsr-Human). To control the influence of screen position, the eight logos were arranged in a circular formation at the center of the screen (see Figure 5). To examine the moderating effect of disclosing creator type, these experimental materials were presented twice. The first presentation served as a control group, without disclosing the creator type and consisting solely of the logo image without any other cues. The second presentation served as an experimental group, with the phrases “Generated by AI” and “Designed by Humans” added next to the logo image. To control the influence of screen position, the AIGLs and human-created logos were interspersed. Eye-tracking data were collected during this period to analyze participants’ fixation on the logos.

Figure 5. Presentation of experimental materials in eye-tracking test. (a) The pre-test experimental materials. (b) The post-test experimental materials.

4.2 Experimental apparatus

This study used a Tobii Pro Nano screen-based eye tracker with a sampling rate of 60 Hz for data collection, and Tobii Pro Lab was used to program the experiment. The system was equipped with a laptop computer with a resolution of 1920×1080 dpi. The experimental environment was equipped with a work surface and adjustable chairs to facilitate participants of varying heights to adjust the distance between their eyes and the screen. Incandescent lamps were used for experimental lighting to reduce direct sunlight on the subjects and experimental equipment, thereby avoiding interference with the reliability and authenticity of the eye tracker data. The laboratory also provided a semi-enclosed experimental area that separates participants from researchers, aiming to provide participants with a sense of security so that they can focus more on the experiment.

4.3 Experimental procedure

For Study 2, we recruited 60 participants for a repeated eye-tracking test. Each participant was required to view the pre-test and post-test experimental materials twice. Before the experiment begins, participants need to read and sign the “Experimental Informed Consent Form” and familiarize themselves with the experimental plan under the guidance of the researchers. After confirming the participant’s understanding of the experimental procedures, the researcher assisted them in adjusting the relative position of the screen and the eye tracker. The researcher then instructed the participant to calibrate the eye tracker using a nine-point calibration. Once calibration was complete, the experiment began. The formal experiment was divided into two stages, and each stage had written instructions to ensure that participants could complete the test smoothly without external interference. The first stage measured initial user attention. To avoid interference from the initial fixation point, a fixation correction interface was played for 3,000 milliseconds before the presentation of the material to ensure that the participant’s initial fixation remained in the center of the screen. Participants were given 20 s to freely browse the screen and select the logo image that most captured their attention. The screen then briefly went black to give their eyes a rest. Once their attention was restored, they could press any key to continue the experiment. The materials in the first phase only showed logo images and did not disclose any information about the creator type (see Figure 5a). The materials in the second phase were based on the materials in the first phase and included a textual description of the creator type (see Figure 5b). The materials for the second stage were based on the materials from the first stage, with textual descriptions of the creator type (see Figure 5). Participants had 60 s to read each information segment. After reading, they were required to press the spacebar and answer the experimental questions to conclude the experiment. The experimental flow is shown in Figure 6. After checking the validity of the data, we excluded 6 samples with low sampling rates and retained 54 valid samples (China = 57.4%, Korea = 42.6%, Male = 37%, Female = 63%, Age range = 19–43 years).

The eye-tracking metrics selected for this experiment include the number of fixations on the area of interest (AOI), total fixation duration on the AOI, first fixation time on the AOI, and heatmaps. Areas of Interest (AOI) refer to specific regions designated in eye-tracking experiments for analyzing user attention and cognitive processes, typically focused on particular elements of the screen. Eye-tracking data collected within these AOIs were recorded separately to enable a detailed examination of user attention distribution and cognitive strategies toward content within these areas.

Fixation Count on AOI: This refers to the number of times participants fixated their gaze within an AOI, reflecting their level of interest and willingness to pay attention to that AOI.

Total Duration of Fixation on AOI: This refers to the sum of times participants spent fixating on AOI, reflecting their level of attention allocation and the duration of sustained attention to that AOI.

Time to First Fixation on AOI: This refers to the moment when participants first fixate on an AOI, reflecting their initial level of interest and willingness to pay attention to that AOI.

4.4 Results analysis of the eye-tracking test

4.4.1 Nonparametric comparative analysis of attention distribution

To verify the robustness of the data, a normality test was performed using the Shapiro–Wilk. The normality test showed that only a few parameters were normally distributed. Therefore, nonparametric Friedman test was applied for statistical analysis, with a significance level set at p < 0.05. Where significant, group differences were assessed using the Wilcoxon test. The effect sizes from the Wilcoxon test, intended to measure the magnitude of significant differences, were reported as absolute values: 0.1 as small, 0.3 as medium, and 0.5 as large (Zimmerman and Zumbo, 1993). In this study, the Wilcoxon test was corrected using the Bonferroni method, with a significance level set at p < 0.006 (i.e., 0.05 / 8). The effect of significant differences was determined by the absolute value, and the direction of the difference was determined by median comparison. These results are displayed in Table 6.

The Friedman test indicated no significant difference in the total duration of fixation within the group lacking creator type designation. Significant differences in total duration of fixation, fixation count, and time to first fixation were observed within the prompt creator type group. Results from the Wilcoxon test were visually represented to more clearly delineate significant differences between groups (see Figure 7). Differences in the interactive effects of innovation and semantic relevance within the same creator type (AI/Human) were analyzed horizontally, while the impact of creator type on user attention under the same interactive effects was compared vertically.

Figure 7. Visualized paired comparison using nonparametric test. (a) Fixation count. (b) Total duration of fixation. (c) Time to first fixation.

The fixation count was indicative of users’ willingness to engage. Figure 7a shows the difference in the fixation count on the logos. Analysis revealed that users were more inclined to focus on highly innovative logos when the creator type was Ai (Hi-Hsr-Ai > Li-Hsr-Ai). Comparing highly innovative AIGLs, users demonstrate more preference for AIGLs with high semantic relevance (Hi-Hsr-Ai > Hi-Lsr-Ai).

The total duration of fixation represents the users’ actual attention behavior. Figure 7b shows the difference in the total duration of fixation on the logos. The results show that when the creator type was AI, users paid more attention to highly innovative logos (Hi-Hsr-Ai > Li-Hsr-Ai, Hi-Lsr-Ai > Li-Lsr-Ai). This finding aligns with the results of the fixation count. Comparing logos with the same level of innovation found that at high levels of innovation, users paid more attention to AIGLs with high semantic relevance (Hi-Hsr-Ai > Hi-Lsr-Ai). Conversely, at low levels of innovation, users paid more attention to human-created logos with low semantic relevance (Li-Lsr-Hum > Li-Hsr-Hum).

The time to first fixation reflects the initial attraction to the experimental material. Figure 7c shows the difference in the time to first fixation on the logos. Analysis of this indicator reveals that when logos had high semantic relevance, both highly innovative AIGLs (Hi-Hsr-Ai > Hi-Lsr-Ai) and minimally innovative human-created logos (Li-Hsr-Hum > Li-Lsr-Hum) result in stronger initial appeal. That indicates that logos with high semantic relevance attract significantly more initial attention, regardless of who created them. Analysis of AIGLs with the same semantic relevance found that logos with low innovation levels exhibit stronger initial appeal (Li-Hsr-Ai > Hi-Hsr-Ai, Li-Lsr-Ai > Hi-Lsr-Ai). This phenomenon was not reflected in other indicators, suggesting that users first notice AIGLs with low innovation levels and gradually shift their attention toward AIGLs with high innovation levels during observation.

A comprehensive comparison of creator type reveals that when creator type was not disclosed, there was no significant difference in users’ sustained attention to AIGLs and human-created logos. However, when creator identities were disclosed, the distribution of sustained attention underwent a significant change, with AIGLs and human-created logos that exhibit high semantic relevance receiving greater attention. That indicates that the creator type moderates users’ sustained attention, supporting H5.

A comprehensive analysis of the three indicators reveals that when the creator type was AI, users demonstrated stronger sustained attention to highly innovative and highly relevant logos. Therefore, H5a was rejected. H5b was supported. Conversely, when the creator type was Human, logos with low innovation received more significant sustained attention, contradicting our hypothesis and leading to the rejection of H5c. Logos with low semantic relevance garner more sustained attention, supporting H5d.

4.4.2 Heatmap visualization of attention distribution

To observe changes in user attention distribution, we used Python to generate eye-tracking heat maps. This study calculated the start-end variation ratio based on the total duration of fixation and time to first fixation to analyze the weight of each AOI in overall visual attention. By calculating the start ratio and end ratio separately, we can compare the relative changes between the two and understand the degree of repeated attention users pay to the logo.

Start Ratio = Time to First Fixation/Total Duration of Fixation. The start ratio indicates the initial attention distribution weight of users to the logo.

End Ratio = (Total Duration of Fixation - Time to First Fixation)/Total Duration of Fixation. The end ratio indicates the retrospective attention distribution weight of users toward the logo, reflecting sustained interest in the logo during later visual processing.

Start-end Variation Ratio = Start ratio / End ratio. The higher the value of the start-end variation ratio, the more pronounced the initial behavior and the stronger the maintained attention.

Average Duration of Fixation = Total Duration of Fixation/Fixation Count. The average duration of fixation represents the cognitive depth of the users during the visual processing process, serving as an auxiliary indicator.

Figure 8 shows the distribution of user attention. Warmer colors indicate a more concentrated distribution of attention in that AOI, while cooler colors indicate that attention was more sparse. The heatmap shows that the start-end variation ratio for Hi-Hsr-AI, Hi-Lsr-AI, Hi-Hsr-Human, and Hi-Lsr-Human was significantly higher, indicating that these AOIs with highly innovative characteristics were more likely to attract subsequent attention. Analyzing the heatmap of human-created logos reveals that Hi-Hsr-Human had a low start-end variation ratio and a high average duration of fixation, indicating that users pay more attention in the early stages but revisit it less frequently later on. That suggests that human-created logos with high innovation and high relevance were easier to understand, resulting in weaker sustained attention. Li-Lsr-Human achieved the highest start-end variation ratio and average duration of fixation, indicating that users allocated the most attention to human-created logos with low innovation and low relevance, and demonstrated strong sustained attention.

5 Discussion

This research combines self-report and eye-tracking tests to investigate the moderating impact of creator type on the synergistic effect of innovation and semantic relevance in brand logo communication. Based on the two creator type, we established a human-created logo database and an AIGLs database. We selected four logos from each database to represent the four levels of the synergistic effect between innovation and semantic relevance (Hi-Hsr / Hi-Lsr / Li-Hsr / Li-Lsr). The experimental results confirmed that both the interaction between innovation and semantic relevance and creator type significantly influence users’ sustained attention.

The results of the questionnaire confirmed that the interaction between innovation and semantic relevance has an impact on sustained attention, with highly innovative and highly relevant logos more likely to attract sustained attention. We also observed that cognitive evaluation mediates the path through which semantic relevance influences sustained attention. This means that semantic relevance cannot directly attract users’ attention, but high semantic relevance significantly enhances users’ cognitive evaluation of the logo, thereby attracting sustained attention. Meanwhile, innovation has a significant direct impact on sustained attention. This result provides an explanation for the synergistic effect of innovation and semantic relevance on sustained attention. Sustained attention is a finite resource that can be depleted (Scerbo et al., 1987), typically fluctuating from seconds to minutes (Esterman et al., 2013). Physiological arousal is crucial for sustained attention. The innovation of a brand logo can quickly trigger an emotional response of pleasure or surprise, increasing users’ physiological arousal (Balters and Steinert, 2017). This arousal intensifies users’ emotional response to the brand logo (Schachter and Singer, 1962; Zillmann, 2018), thereby attracting their attention. In this process, physiological arousal activates the rapid emotional response system, attracting more immediate attention (Kahneman, 2011). Semantic relevance prompts slower cognitive processing systems to process brand information in detail. Selective attention models state that when external information is relevant to a current goal, people activate a top-down, goal-driven attentional mechanism (Treisman, 1960), proactively allocating more attentional resources to that information. The dual-process model and selective attention models both suggest that people rely on two systems simultaneously to process information. Information with high innovation can activate the emotional response system, triggering a bottom-up stimulus-driven attention, while information with high semantic relevance can activate the cognitive processing system, triggering a top-down goal-driven attention. In other words, innovation attracts immediate attention and is a prerequisite for sustained attention, while semantic relevance maintains attention, which is the main process for sustained attention. These two systems correspond to the emotional response system and the cognitive processing system, respectively, and have a dual effect in attracting sustained attention.

The results of the eye-tracking test validated the moderating effect of creator type. When the creator type is AI, innovation positively correlates with users’ sustained attention. This is attributed to users’ expectations of AI technology, which stemmed from their trust in the computational capabilities of AI. Literature in the field of human-computer interaction indicates that users’ trust in AI and the roles they assume influence the depth and quality of their interactions (Hou et al., 2023). Research by Reuter et al. (2025) indicates that the disclosure of the creator’s identity triggers user perception of their social presence. When a virtual system is given a higher degree of anthropomorphism or sociality, users are more willing to interact and have higher expectations of the system. In our research, when users realize that the logo is generated by AI, they tend to invest more attention and resources to witness the improvement in the quality of the AI’s work. Analysis of the moderating effect of creator type on semantic relevance reveals that when the creator type is AI, although semantic relevance positively correlated with attention behavior, it negatively correlated with initial attraction. This suggests that the high semantic relevance of AIGLs obscures the initial perception of innovation, while users tend to expect AI to provide diverse visual outputs. When the creator type is human, logos with high semantic relevance reduce users’ sustained attention. Human designers are skilled at integrating complex metaphors, and this pattern reflects users’ emotional expectations toward human-created logos. Therefore, compared to AIGLs, human-created logos with high semantic relevance effectively convey information, but overly explicit symbols weaken their emotional impact and fail to meet users’ expectations.

Interestingly, in the limited innovation cases, the human-created logos with low semantic relevance actually garnered more sustained attention, exceeding our expectations. This phenomenon can be explained by cognitive dissonance theory (Festinger, 1962), a theory of cognitive orientation in cognitive psychology. When individuals receive information that contradicts their existing cognitions, they experience a negative emotional state called dissonance (Festinger, 1962). Festinger proposed that this negative emotion motivates individuals to seek ways to reduce cognitive dissonance, often by taking actions to add new and consistent cognitions to reduce the discrepancy (Hinojosa et al., 2016; Morvan and O’Connor, 2017). The adjustment process of cognitive dissonance enhances users’ cognitive engagement. However, this phenomenon is not observed in AIGLs. This indirectly proves that users have a high tolerance for AIGLs but a low level of trust in them. User perception is that a product of data and algorithms, and they expect AIGLs to demonstrate higher brand consistency. Therefore, for AIGLs with low semantic relevance, users tend to attribute low quality to the emerging stage of AI technology. In contrast, human-created logos are typically perceived as capable of conveying deeper, multidimensional meanings, with users placing greater value on the emotional investment and innovation of designers. Therefore, for human-created logos with low semantic relevance, users are able to focus more intently on interpreting their underlying meanings. This observation aligns with the findings of Song et al. (2024) regarding the impact of declared creator type and advertising appeals on tourists’ intentions to visit. They found that designs attributed to human creators and characterized by emotional resonance are more appealing; meanwhile, those attributed to AI, highlighting rationality, are seen as more effective.

Additionally, when confronted with the same creator type, users prioritize logos with higher levels of innovation. This reminds us that while semantic relevance has been considered key to enhancing the effectiveness of information transmission, the results of this research indicate that users tend to prefer logos with high innovation. This preference suggests that users place greater value on the innovation of design rather than its ability to accurately convey semantic relevance, especially during initial exposure. These insights are crucial for designers striving to balance innovation and semantic relevance.

6 Conclusion

6.1 Theoretical implications

This research explores the synergistic effect of innovation and semantic relevance on sustained attention across different creator type through two studies, and explores the mediating effect of cognitive and emotional evaluations in this process. This research advances relevant theoretical research in the following three aspects.

First, our research extends the intrinsic driving mechanism of visual attention theory. Previous research on brand marketing has typically focused on consumers’ cognitive intentions and purchase decisions through visual design components such as logo color, size, form, and orientation (Zhang et al., 2006; Hagtvedt, 2011; Park et al., 2024; Miceli et al., 2014; Bresciani and Del Ponte, 2017; Huang et al., 2021; Xie et al., 2021; Peng et al., 2022). This emphasis has been placed on the influence of brand external salience on users’ behavioral responses. Our research extends theories of visual attention from external feature perception to internal meaning perception. Incorporating the selective attention model (Treisman, 1960), we focus on the synergistic effect of innovation and semantic relevance. We reveal the possibility of influencing users’ sustained attention through intrinsic motivation by balancing semantic comprehensibility with the unexpectedness of innovation.

Second, our research examined the mediating effects of cognitive and emotional evaluation. The results indicate that cognitive evaluation are more effective than emotional evaluation in influencing sustained attention, which further supports the dual-process model (Kahneman, 2011). Specifically, emotional evaluation corresponds to the rapid emotional response system, characterized by automatic responses that help capture fleeting attention. Cognitive evaluation corresponds to the slow cognitive processing system, emphasizing systematic information organization and sustained cognitive engagement, which helps enhance sustained attention.

Third, our research provides empirical evidence for theories related to human-computer interaction and trust in AI. While numerous research have compared AIGC with human creativity, few have considered AI as an independent designer and explored the impact of creator type heterogeneity on users’ sustained attention. This perspective fills a significant gap in current design research. Our research based on the AIGLs database, verifies the moderating effect of creator type on users’ sustained attention when AI acts as an independent designer. This explains users’ cognitive processing of AIGLs and also reflects their trust in AI and their attribution of its social role. When user perceive the creator as human, they assume the brand logo possesses emotional intent and cultural context. However, when they perceive the creator as AI, they may reassess the creative intent and authenticity. To our knowledge, our research is the first to explore the dual mechanisms of innovation and semantic relevance on users’ sustained attention in the context of AI generation. This provides theoretical support for improving the quality of AIGLs.

6.2 Practical implications

Our findings highlight the cognitive biases and expectations users have when engaging with AI- and human-created logos, and offer actionable insights into the practical role of AI technology in brand design.

For AIGLs, this research demonstrates that AI technology has a positive impact on users’ sustained attention in logo design. Most users have expressed a positive wait-and-see attitude toward AIGLs, anticipating that AI technology will bring more high-quality designs. Although this positive expectation is still based on a lack of trust in AI-generation technology, it highlights the potential for AI technology to integrate with the design industry and strengthens confidence in further research on AIGLs.

For companies intending to use AI to generate brand logos, the findings of this research indicate that when AI acts as an independent designer, it can provide a large number of logo designs with innovative features due to its different thought processes. These highly innovative logos attract sustained attention in practical applications. This provides reference experience for companies using AIGLs: when using AI to generate logos, it is more advantageous to focus on the innovation dimension of the logo. Additionally, disclosing to users that the AIGLs can attract more positive user attention.

For brand designers, this research confirms that in the field of brand logo design, especially in scenarios requiring complex emotional expression, human designers’ guidance, and screening remain an indispensable key step in improving design quality. Therefore, designers should actively explore how to reasonably apply AI technology to design, using it as an effective tool to supplement and enhance human creativity. The design industry should also promote cooperation models between AI and human designers, leveraging the strengths of both to meet the ever-changing needs of brands.

6.3 Limitations and future research

To investigate the factors influencing users’ sustained attention to AIGLs, this research made efforts to control for irrelevant factors. Although the experimental results supported our hypotheses, there are still some limitations.

First, there are limitations in the experimental materials. During the database construction process for AIGLs, we observed that AI exhibited excessive innovation and distortion in interpreting logo meanings. To control these variables, this research screened AIGLs based on moderate innovation levels. Therefore, logos created solely by AI without the involvement of designers may not perform as well as expected, indicating that AIGLs models still have a long way to go. In the future, we will further expand the AIGLs database and annotate logos to provide learning resources for AI models to better understand human intent.

Secondly, there are limitations to the research sample. Since the samples are drawn from China and South Korea, our research reveals the design acceptance mechanism of AIGLs in the Asian cultural context. Eastern esthetics tends to focus on integrity, emphasizing artistic conception and symbolic meaning (Yuan et al., 2021), while Western esthetics focuses more on formal innovation and cognitive differentiation (Leder and Nadal, 2014). This regional cultural difference may lead Asian participants to prioritize semantic coherence and symbolic meaning, and tend to focus on designs with high semantic relevance, which provides insights for companies intending to expand into the Asian market through AIGLs. However, the results should be applied with caution to users from other cultural backgrounds. Future research could conduct cross-cultural verification of AIGL’s market effectiveness on user groups with different cultural backgrounds. In addition, participants’ prior attitudes toward AI may influence their brand logo attention outcomes, but this research did not account for this factor. We will continue to explore this topic in future research.

Finally, there are limitations to the research method. Considering that AIGLs are still in the early stages of technological development, this research set a simple design theme, and the design elements used by AIGLs are more directly related to the brand meaning. This reduces the cognitive effort required by users when browsing AIGLs, making it easier to sustain attention. Therefore, the results of this research should be replicated in future research to determine whether AIGLs’s impact on sustained attention aligns with the findings of this research under complex semantic relationships. To deepen our understanding of user behavior, future research could combine eye-tracking tests with emotional tests to comprehensively evaluate the effectiveness of AIGLs through a cross-modal design approach.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Jeonbuk National University Institutional Review Board (JBNU IRB). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

WG: Validation, Visualization, Data curation, Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Formal analysis. SL: Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis. LZ: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. CZ: Formal analysis, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the editors and reviewers of Frontiers in Communication for their valuable feedback, which has made this article better.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. We used ChatGPT-4o and Midjourney-v5.2 to generate experimental material as an AI designer to explore the question of whether AI has the potential to serve as an independent designer. We review and edit the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcomm.2025.1667077/full#supplementary-material

References

Al Naqbi, H., Bahroun, Z., and Ahmed, V. (2024). Enhancing work productivity through generative artificial intelligence: a comprehensive literature review. Sustain 16:1166. doi: 10.3390/su16031166

Balters, S., and Steinert, M. (2017). Capturing emotion reactivity through physiology measurement as a foundation for affective engineering in engineering design science and engineering practices. J. Intell. Manuf. 28, 1585–1607. doi: 10.1007/s10845-015-1145-2

Bao, Y., Shao, A. T., and Rivers, D. (2008). Creating new brand names: effects of relevance, connotation, and pronunciation. J. Advert. Res. 48, 148–162. doi: 10.2501/S002184990808015X

Batra, R. (2019). Creating brand meaning: a review and research agenda. J. Consum. Psychol. 29, 535–546. doi: 10.1002/jcpy.1122

Beverland, M. B. (2005). Managing the design innovation–brand marketing interface: resolving the tension between artistic creation and commercial imperatives. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 22, 193–207. doi: 10.1111/j.0737-6782.2005.00114.x