- 1Department of Management, Marketing, Entrepreneurship, and Fire & Emergency Services Administration, Broadwell College of Business and Economics, Fayetteville State University, University of Tennesse, Fayetteville, NC, United States

- 2Graduate and Professional Studies in Business, Broadwell College of Business and Economics, Fayetteville State University, Washington University in Saint Louis, Fayetteville, NC, United States

Introduction: Nonprofit branding in today’s digital and social media landscape is increasingly shaped by active audience participation, rather than solely by messaging from the organization. This study investigates how donors’ perceptions of congruence between their ideal and actual charities, measured as donor–brand congruence, influence the amount of charitable giving.

Methods: Using a survey based on the Aaker Brand Personality Scale, participants evaluated both their actual and ideal charities across 15 facets within five brand personality dimensions, including Sincerity, Excitement, Competence, Sophistication, and Ruggedness. Participants also provided demographic data, personality traits, and annual donation amounts.

Results: The findings reveal that donors perceiving a match between their ideal and actual charity brands self-report more financial contributions. Additionally, age and emotional stability correlated with greater perceived congruence.

Discussion: The results suggest that forming a match between a nonprofit’s actual brand and the audience’s ideal brand can be essential for creating nonprofit brand identities that resonate within a hyper-personalized (tailored to individual preferences), polycentric (influenced by many actors) communications environment. By encouraging donor input and discovering their aspirational values, nonprofits can cultivate authentic connections, strengthen loyalty, and encourage word-of-mouth advocacy for their cause.

Introduction

According to the World Giving Index (Charities Aid Foundation, 2024; Charities Aid Foundation, 2021), 4.2 billion people, about 72 percent of the world’s adult population, contributed money, volunteered their time, or helped a stranger in 2022. These numbers illustrate the global reach of philanthropy. In the United States, nonprofits operate in a voluntary and individualistic society where they compete for attention and support. Brand personality can help connect mission-driven values with market-oriented appeals, particularly in individualistic societies where giving often reflects self-interest (Cai et al., 2022). Studies also link greater economic freedom with higher charitable giving, suggesting that free-market environments can foster philanthropy (Jackson and Beaulier, 2023). To earn this attention and support, nonprofits must do more than explain what they do; they must express who they are. Brand personality has become a powerful tool for generating audience connection and establishing market differentiation. When matched with donors’ values and self-concepts, brand personality can significantly influence audience engagement and giving (Lee et al., 2024; Mirzaei et al., 2021).

Examining the role of identity in giving is becoming increasingly important as donors face more choices than ever before. As donors navigate an increasingly personalized branding environment, understanding how donor traits shape and reflect brand image is imperative (Crawford and Jackson, 2019). Branding provides cues that shape donor perceptions. Donors are influenced not only by stated organizational missions but also by how well those missions resonate. Research by Wymer and Čačija (2025) demonstrates that strong nonprofit brands enhance volunteer retention and increase intentions to donate, establishing both organizational relevance and sustaining ongoing financial support. As Lim et al. (2021) argue, scholars continue to explore the utility of psychographic data, such as personality traits, in targeting consumers with nonprofit messages. However, the translation of brand perceptions into donations remains under explored, leaving a gap in philanthropic branding research.

Although interest in nonprofit branding is increasing, few studies have examined the impact of brand congruence, or the degree of psychological distance between donors’ real and perceived nonprofit brand personalities, on charitable giving and have addressed the need for more nuanced models of donor-brand relationships (Kumar and Chakrabarti, 2023). This study addresses that gap by examining how congruence between the brand image of a philanthropy that donors support (a real charity) and a philanthropy that reflects their aspirational values (an ideal charity) influences charitable giving instead of using individual brand traits (Sirgy, 1982; Groza and Gordon, 2016). In philanthropic markets such as those in the US (Cai et al., 2022), organizations use strategic branding to engage with donors. Previous work has shown that certain brand personalities or attributes can drive donations (Groza and Gordon, 2016). Building on prior work, this study examines whether congruence matters on its own. To address these issues, we propose the following two research questions: How does congruence relate to charitable donations? Specifically, does congruence between a person’s ideal and real charity result in higher donations? Therefore, this study advances our understanding of philanthropic branding by moving beyond an understanding of donor and brand traits and revealing how overall brand congruence drives donations.

By revealing that congruence between real and ideal brand perceptions is associated with increased donations, this study contributes to the philanthropy literature that connects brand attributes to giving (Kumar and Chakrabarti, 2023; Michel and Rieunier, 2012). Our research aligns with established scholarship by suggesting that congruence between real and ideal charities could foster self-congruence (Sirgy, 1982), reinforce social identity (Tajfel, 1978; Tajfel and Turner, 2004), and signal a similarity in values (Bekkers and Wiepking, 2011).

Using a survey instrument administered to donors serviced by a non-profit organization which assists other non-profits with donor engagement, we create a measure of donor congruence between the brand image of a charitable cause that they have donated to and their perception of what would be the ideal brand image of a charity. We employ ordinary least squares regression as well as two-stage least squares regression, which controls for potential endogeneity in the data, to examine the relationship between donor congruence between ideal and real charitable brand image and the size of the donation made to the charity. We find that increased congruence is associated with a larger donation.

Literature review

Brand personality and nonprofit identity

Developing a clear and compelling identity is essential for nonprofit organizations, yet many struggle to balance a utilitarian, business-oriented identity with a normative, mission-driven one (Lee and Bourne, 2017). Recent research emphasizes the importance of consumer perceptions and emotional resonance in shaping the effectiveness of nonprofit branding (Sandoval and García-Madariaga, 2024). Pereira et al. (2024) found that perceived consumer value acts as a mediator between cause-related marketing and brand engagement, particularly for brands with strong emotional appeal. This suggests that brand personality traits play a significant role in engaging donors.

According to Gardner and Levy (1955, p.35), “a character or personality may be more important for the overall status (and sales) of the brand than many technical facts about the product.” Brand personality traits communicate meaning beyond product features alone (Gardner and Levy, 1955). Brand personality originates from research on human attributes leading to personality-led branding, making it a central component of brand image (Kuenzel and Halliday, 2010; Malär et al., 2011). Brand personality refers to human characteristics associated with a brand (Aaker, 1997) that can embody lifestyle (activities, interests, beliefs, etc.), demographic (age, sex, socioeconomic status, etc.), and personality (sophistication, sincerity, excitement, etc.) attributes (Srivastava and Sharma, 2016). This construct is important because brand personality contributes to a brand’s success by establishing a preference (Mulyanegara et al., 2009; Freling and Forbes, 2005), fostering emotional brand attachments and identification (Swaminathan et al., 2009; Orth et al., 2010; Malär et al., 2011; Usakli and Baloglu, 2011), instilling trust and loyalty (Louis and Lombart, 2010; Lin, 2010; Ramaseshan and Stein, 2014), and creating a clear and distinctive brand message (Grossman, 1994; Kim et al., 2001; Ang and Lim, 2006). When a nonprofit’s brand personality aligns closely with a donor’s ideal self-image, it creates strong self-congruity, allowing the brand to serve as an extension of the donor’s identity and a signal of their values to others (Zhai and Shen, 2024; Aaker, 1997).

Historically, nonprofit marketing research has focused on donor characteristics rather than organizational attributes (Venable et al., 2005). Various empirical studies have explored donor preferences and behavior (Van Slyke and Brooks, 2005; Vesterlund, 2006; Lee and Chang, 2007; Shier and Handy, 2012), fundraising and solicitation techniques (Olsen et al., 2001; Hager et al., 2002; Bennett, 2005; Das et al., 2008; Bray, 2013) and communicating organizational values (Bart and Tabone, 1998; Rothschild and Milofsky, 2006; Sargeant et al., 2008; Khalifa, 2012).

More research is needed to understand how organizations can gain active support. Unlike other consumer brands, nonprofit organizations have distinctive altruistic qualities that resonate with their supporters. They aim primarily to improve society, offering intangible services and embodying ideals (Venable et al., 2005). Meeting audience ideals is key to achieving nonprofit brand congruence.

Social identity theory (Tajfel and Turner, 1979; Tajfel and Turner, 2004) explains how individuals form an identity through group membership. Group membership holds benefits such as an enhanced sense of connectedness and self-esteem. In a philanthropic context, this suggests that donors may align with nonprofits not only for personal self-expression but also to build in-group identification. Brand attitudes arise from both functional and emotional attributes, with self-expression and identity acting as key motivators in forming consumer–brand relationships (Aaker, 1997). Alignment between brand personality and a donor’s ideal self-fosters strong self-congruity (Aaker, 1997). Kumar and Chakrabarti (2023) extend this insight to nonprofits, suggesting that trust functions as a central mechanism linking donor perceptions to ongoing giving. When donors perceive alignment with nonprofit values and experience transparent, confidence-building communication, trust enhances both willingness to give and long-term commitment.

People consume products and services not only for what they do but also for what they mean (Levy, 1959). Building on this, Kressmann et al. (2006) provide empirical evidence that self-image congruence enhances brand loyalty both directly and indirectly through functional congruity, product involvement, and brand relationship quality. By cultivating a brand personality that resonates with donors’ ideal selves, nonprofits can strengthen emotional bonds and loyalty, encouraging sustained giving. When choosing the brand with the desired personality attributes, individuals communicate representations of themselves and/or reinforce their self-image (Ligas, 2000; Srivastava and Sharma, 2016).

Brands consumed publicly can also serve a signaling function, communicating about donors’ real and ideal selves (Swaminathan et al., 2009; Hollenbeck and Kaikati, 2012; Zhai and Shen, 2024). Signal theory can help explain how donors choose nonprofits when information is limited (Connelly et al., 2010). Donors tend to behave rationally, preferring high-quality projects. However, donors cannot always directly observe the quality of a philanthropy (Handy, 2000; Vesterlund, 2003). Although the evidence is mixed, some research has found that social cues, such as observing others’ donations, could serve as a signal for trustworthiness (Bekkers and Wiepking, 2011; Van Teunenbroek and Bekkers, 2020). Brand personality and real-ideal fit provide additional signals that indicate credibility and shared value (Aaker, 1997; Sirgy, 1982). Glazer and Konrad (1996) demonstrate that charitable organizations can use observable cues, such as prior fundraising success or visible endorsements, as signals to communicate competence and trustworthiness to potential donors. And, as Chapman et al.’s triadic model suggests, giving behavior is highly relational and donors depend upon interactions with others, such as fundraisers and beneficiaries, to assess impact (2022).

Organizations seek to establish a brand connection by making the brand’s personality fit the way their audience perceives themselves. This alignment is especially effective when it reflects the person’s real self (Malär et al., 2011). Researchers usually focus on two main aspects of self-concept: the actual and the ideal self. Brands may express who consumers are (actual self) or who they aspire to become (ideal self; Belk, 1988; Holt, 2002; Hollenbeck and Kaikati, 2012). Self-expressive traits included in brand personality can further shape identification. When branding seems authentic and aligned with audience values, it can establish trust and strengthen attachment (Behnke, 2025; Ghauri et al., 2025). According to self-concept theory, consumers’ decision making enhances, maintains, and protects their sense of self (Cheema and Kaikati, 2010). Consumers’ observable behaviors may be influenced more by their ideal self than by their actual self (Dolich, 1969; Ross, 1971; Alpert and Kamins, 1995; Graeff, 1996). Supporting this idea, Swaminathan et al. (2009) propose that brands serve a signaling function when consumed in public rather than in private. Hollenbeck and Kaikati (2012) argue that consumers express both their actual and ideal selves through their consumption habits. Aligning audience traits or context with the consumer can increase persuasive effectiveness, particularly for nonprofits where donors support causes reflecting who they aspire to be (Teeny et al., 2021). The distinction between actual and ideal self is especially applicable in the context of nonprofits, where donors may support philanthropies that reflect not just who they are but who they strive to become.

While the construct of consumer brand personality (Aaker, 1997) applies well to the nonprofit sector and generally enhances the image of nonprofits, social benefits and trust are especially applicable to nonprofits (Venable et al., 2005). Recent research emphasizes nonprofit-specific topics: brand personality and equity/goodwill (Singh, 2013), brand values and consumer attitudes (Marquardt et al., 2015), and advertising’s role in strong brands (Aaker and Biel, 2013).

When the research (Venable et al., 2005) explored whether Aaker’s (1997) brand personality scale applied to nonprofits, the results showed that brand personality could be used to craft a unique image. In addition, the research indicated that brand personality differences exist among nonprofits (Venable et al., 2005). For instance, Groza and Gordon (2016) found that the brand personality traits of nurturance and sophistication predicted volunteering, while nurturance and ruggedness predict recommendations. Importantly, in the context of nonprofits, self-brand congruence showed that alignment with the trait of nurturance drove overall engagement, including donating, volunteering, and recommending.

Consequently, when audiences perceive congruence between their values and a nonprofit’s brand personality, it triggers deeper psychological mechanisms that encourage altruism. Such alignment enables donors to express identity, strengthen self-concept, and enhance loyalty and trust (Swaminathan et al., 2009; Khamitov et al., 2019; Valette-Florence and Valette-Florence, 2020).

According to Shang et al. (2008), individuals are more likely to donate when they know someone like them has already donated. This effect is enhanced when people feel proud of their affiliation with their aspirational group (Shang et al., 2008). Chapman et al. (2025a) reviewed four decades of research and revealed that donors who feel connected to a cause or other donors are more likely to donate to charities. Experiencing strong brand congruence is more important than simply being a member of a group. Brands that resonate with individuals can serve a symbolic purpose, allowing them to express their identity or their aspirations in meaningful ways. This congruence can even enhance individual’s overall well-being (Kressmann et al., 2006; Parris and Guzmán, 2023).

Donating to a charity that represents one’s ideal traits can both foster social connections and fulfill self-verification and symbolic self-completion needs (Salimi and Khanlari, 2018), particularly when the act of giving is public or identity-relevant. Donor–brand congruence operates as a motivational driver, sustaining donor support and deepening emotional connection. Over the past two decades, the importance of brand congruence has made branding a central focus of both marketing practice and academic research, ushering in what Oh et al. (2020) describe as the “branding era.”

While prior studies highlight the role of value congruence, authenticity, and ideology in donor engagement, less is known about how donor–brand congruence, specifically alignment with a donor’s ideal self, shapes donation behavior. This perspective offers an opportunity to extend research on nonprofit identity by linking psychographic alignment to donation behavior through mechanisms such as self-expression, identity signaling, and trust, which can drive sustained giving.

Brand congruence: psychological foundations and strategic implications

While brand personality can help nonprofits connect with and retain donors, understanding the reasons why certain traits resonate requires an understanding of human personality theory. The following section uncovers how psychological traits shape donor preferences and how congruence between brand and self can deepen emotional connection and increase donations.

According to the American Psychological Association (2017), human personality can be defined as “individual differences in characteristic patterns of thinking, feeling, and behaving.” Therefore, personality is the intrinsic organization of an individual’s mental world that is enduring over time and consistent across situations (Piedmont, 1998). The five-factor model is a human psychological model providing the foundation for Aaker’s model. This model provides a framework for understanding human personality using five enduring traits, which include: agreeableness, extraversion (introversion), conscientiousness, openness, and emotional stability (neuroticism).

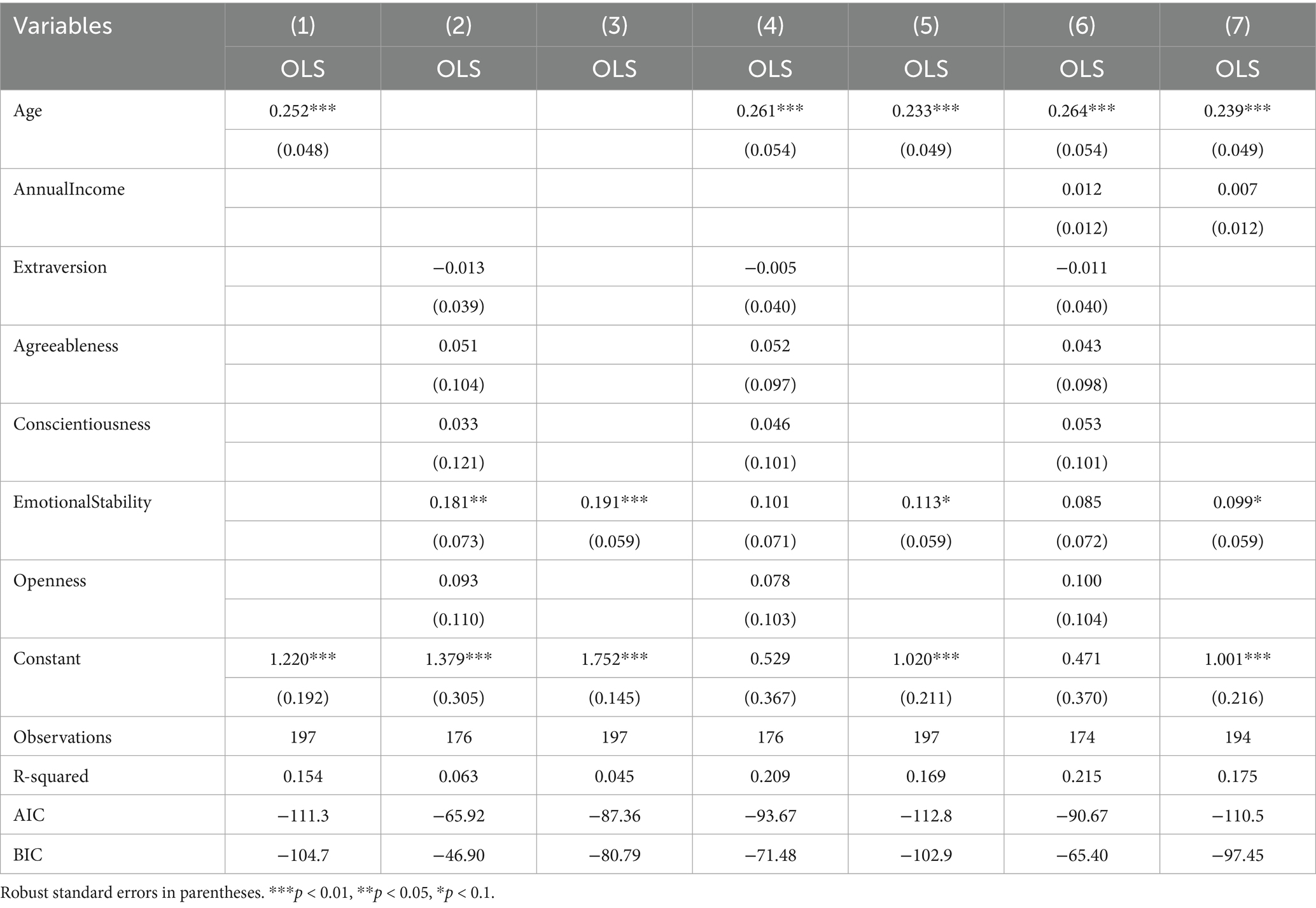

Agreeableness is defined as one’s predisposition to be or not to be good-natured, calm, trusting, and straightforward. Emotional stability is defined as one’s tendency to be calm, relaxed, hard, secure, and self-satisfied. Extraversion is one’s inclination to be sociable, active, talkative, optimistic, and affectionate. Conscientiousness is a preference for organization, reliability, orderliness, and diligence. Openness refers to being curious, creative, original, imaginative, and unconventional. An individual’s personality is formed from these five basic traits (John and Srivastava, 1999). Aaker’s scale for brand personality was based on these foundational human personality constructs which are found in Table 1 (Aaker, 1997).

Table 1. Aaker (1997) 5 brand personality dimensions and 15 facets.

While personality has long been studied in psychology, brand–consumer congruence remains underexplored, especially in nonprofit contexts. Though brand and human personality traits share a common conceptualization, their origins differ (Aaker, 1997). Individuals form perceptions of brand personalities based on direct and indirect contact with that brand (Aaker, 1997).

Aaker (1997) developed a robust scale to measure the Brand Personality construct across a variety of goods and services. To create a framework to measure Brand Personality, Aaker adjusted human psychology’s “Big Five” or five-factor personality model (McCrae and John, 1992). Aaker (1997) general brand framework presents five major traits: sincerity, excitement, competence, sophistication, and ruggedness. These traits subsume 42 individual traits clustered around 15 facets. This construct is based on the five-factor model for assessing human personality, though some of the traits do not correspond precisely to those in the original five-factor model. Some traits are distinct to brands, as customers may select brands that possess characteristics different from their own, sometimes reflecting ideals they value. The traits of sophistication and ruggedness apply only to brand personality measurement (Aaker, 1997).

In addition, there are some human personality traits that are less relevant to brands and are not captured by Aaker’s Brand Personality framework. The framework does not include traits that correspond with Neuroticism or Openness. Because branding is highly aspirational, efforts to base brand personality in human traits also mean that negative personality traits are rarely reported in brands (Aaker, 1997). Using a brand personality scale quantitatively relates brand personality to self-congruence. This relationship can then be related to symbolic consumption benefits such as aspirational branding and meeting self-esteem needs (Plummer, 2000; Kuenzel and Halliday, 2010).

Recent research emphasizes the influence of emotional resonance and individual differences on donor connection. Sandoval and García-Madariaga (2024) used neurophysiological measures to show that while positive emotional appeals enhance attitudes and emotional responses, negative appeals are more effective at eliciting immediate donations. Lee et al. (2024) show that nonprofit brand activism can enhance brand equity. Groenewold (2025) found that persuasive strategies boost donor loyalty, particularly among conscientious individuals. Likewise, Lim et al. (2021) reveal that donor personality traits, such as conscientiousness, influence attitudes and intentions to support nonprofits. Together, these studies demonstrate how emotional resonance and individual differences shape donor engagement.

Brand personality is not a fixed characteristic of a nonprofit organization, but a perceived concept shaped through interactions with stakeholders, media representations, and contextual cues over time. Ultimately, the actions of engaged consumers are the most potent influence on the brand (Black and Veloutsou, 2017). Research shows that brands are dynamic social processes, with branding being a cultural phenomenon driven by the interplay among managers, employees, consumers, and other stakeholders (Merz et al., 2009). These groups co-create brands through their actions, using language and images that represent the brand’s values and meaning (Vallaster and von Wallpach, 2013). Research by Iglesias et al. (2020) provides more detail regarding how philanthropic initiatives across organizational contexts can facilitate this collaborative brand creation process, solidifying customer trust and loyalty by fostering active audience participation.

While prior studies highlight the role of value congruence, authenticity, and ideology in donor engagement, this perspective offers an opportunity to extend research on nonprofit identity by linking psychographic alignment, through the Big Five personality traits, to donation behavior and ideal brand preference.

Theoretical framework, research question, and hypotheses

Although previous research has explored donor characteristics, nonprofit branding, and self-congruity theory independently, limited work has connected these concepts in the context of charitable giving. Few studies have examined how donors’ personality traits affect their alignment with a charity’s brand personality or how this congruence influences donation behavior. While consumer–brand congruity is well established in marketing literature (Aaker, 1997; Mulyanegara et al., 2009), its application to nonprofit giving, particularly through personality and congruence, remains underexplored (Romero and Abril, 2024; Werke and Bogale, 2024). Self-congruity theory (Sirgy, 1982) suggests that individuals are more inclined to prefer brands when the brand’s image aligns with their self-concept. This alignment influences their attachment to the brand and loyalty toward it. Empirical research has demonstrated the predictive validity of this theory in consumer contexts (Sirgy et al., 1997), indicating its potential relevance for understanding donor behavior. This study draws from these insights to examine how donor personality and demographic characteristics relate to alignment with nonprofit brand personality.

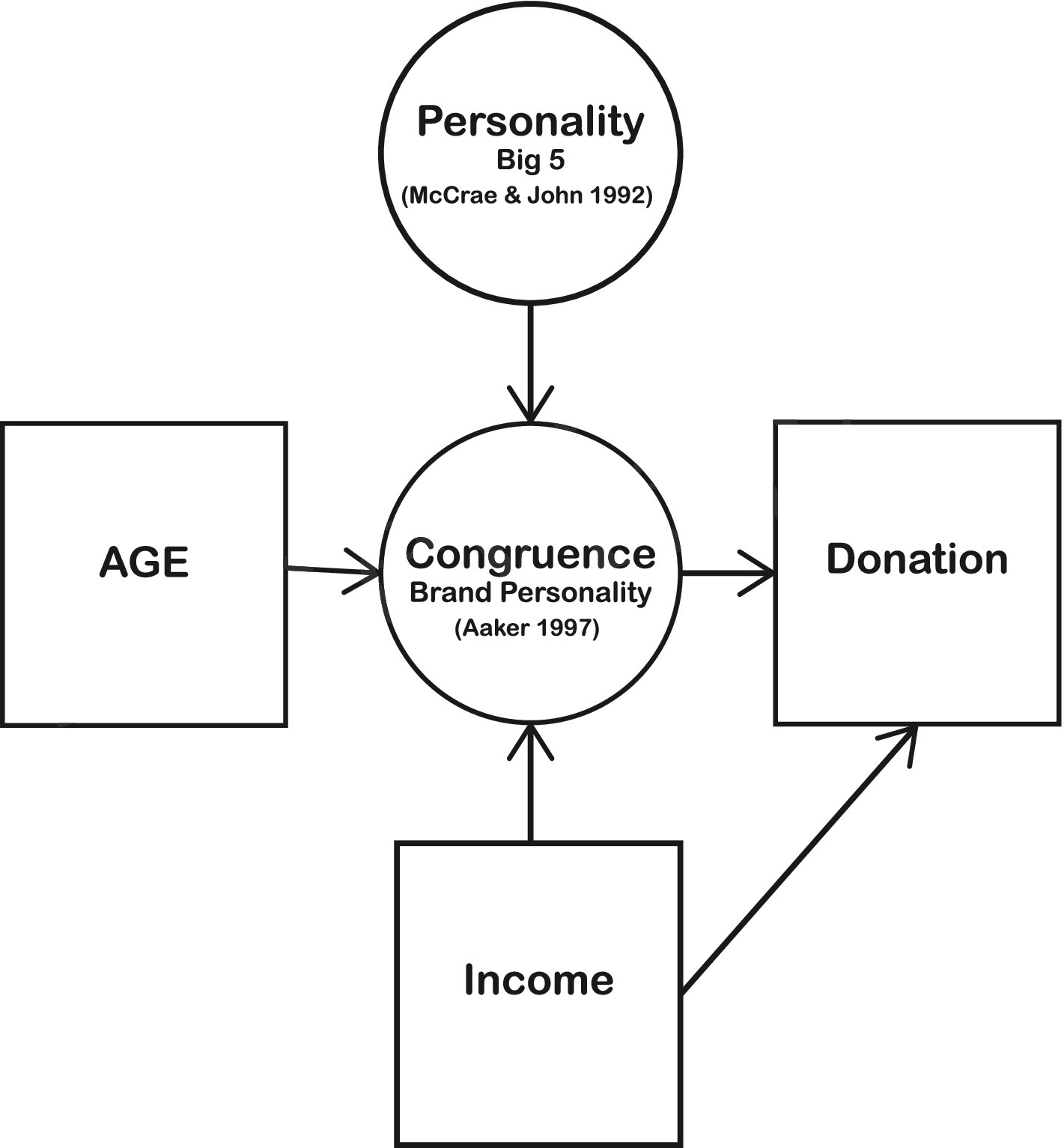

This research examines how closely a donor’s perception of a real charity corresponds to their concept of an ideal charity. It further analyses how this level of congruence, as well as factors such as age and personality traits, influences charitable giving. Figure 1 illustrates the conceptual framework of this study: personality, age and income feed into congruence, congruence feeds into donations, and income also has a direct relationship on donations. Although this model emphasizes the role of personality-driven congruence, it also aligns with established frameworks for explaining charitable behavior, including warm-glow (Bénabou and Tirole, 2006), signaling (Glazer and Konrad, 1996), and value alignment (Kelley and Тhibaut, 1978). Collectively, these mechanisms offer a comprehensive perspective on donor motivation and will be examined in the Discussion section.

Figure 1. Framework for ideal philanthropy: personality, congruence, and donations. Conceptual framework showing how personality, age, and income shape donor–brand congruence, which predicts donations, with income also having a direct effect on donation behavior.

Aaker and Fournier (1995) suggest that brands can function as characters, partners, or even extensions of the self. Brands offer consumers symbolic resources to express their identities. Donors, like consumers, may use charitable organizations to reflect and reinforce aspects of their self-concept. For example, individuals high in conscientiousness and neuroticism often prefer trusted, reliable brands, while those high in extraversion tend to be drawn to sociable or vibrant brands.

These personality-linked preferences extend beyond the brand itself to include the donor’s connection to a broader brand community. Research by Matzler et al. (2011) demonstrates that extraverts are more likely to feel a sense of community affiliation, form friendships through that community, and identify strongly with it. Introverts, on the other hand, may be less influenced by communal bonds. This distinction has important implications for charitable organizations. While some individuals may engage with a charity through social connection or community identity, others may develop loyalty through emotional or symbolic attachment to the brand alone.

Therefore, this research explores how real-ideal charity congruence relates to charitable donations. Specifically, this study focuses on congruence between a person’s ideal and real charity and if this congruence result in higher donations. Additionally, the study investigates whether there is a relationship between the Big Five personality traits and the level of congruence between the charities that participants support and their ideal charity.

Research questions and hypotheses

The degree of congruence between donor traits and charities may have a direct effect on giving. This study draws on several perspectives relevant to donor behavior, including concepts from self-congruity theory, suggesting that alignment between an individual’s self-concept and a brand’s personality can influence engagement (Sirgy, 1982; Sirgy et al., 1997; Michel and Rieunier, 2012; Zogaj et al., 2021). We focus on how congruence, age, and personality traits may shape alignment with nonprofit brand personality and charitable giving.

RQ1: How does congruence relate to charitable donations? Specifically, does congruence between a person’s ideal and real charity result in higher donations?

In nonprofit contexts, donors whose self-concept aligns with a nonprofit’s brand report stronger emotional attachment and are more likely to give (Zogaj et al., 2021; Michel and Rieunier, 2012). Michel and Rieunier (2012) further show that nonprofit brand image dimensions (such as usefulness, efficiency, affect, and dynamism) and perceived typicality of the organization can explain substantial variation in intentions to give money and time. These findings suggested that donors were more likely to donate when the organization’s image aligned with their own expectations and values, which reinforces the rationale for studying congruence between ideal and real charities and brand personality.

H1: Increased donor congruence is positively correlated with increased donations.

Greater knowledge and experience could enhance the likelihood of donors identifying an optimal charitable match. Older donors are more likely to find charities that align with their values, and age increases motivation to give. Research also shows older individuals experience greater satisfaction from donations, supporting an age-related positivity bias in charitable giving (Bjälkebring et al., 2016). Therefore, we use age as a predictor of congruence.

H2: There is a positive relationship between age and congruence.

Personality traits may shape how likely individuals are to select charities that align with their values. A meta-analysis of 29 studies found modest associations between Big Five traits and philanthropic behavior, with extraversion connected with volunteering and agreeableness with giving, while other associations were mixed, likely due to methodological differences (Bleidorn et al., 2025). Therefore, the following hypotheses examine personality traits as exploratory predictors of donor congruence.

H3: There is a positive relationship between emotional stability and congruence.

Emotionally stable individuals handle stress effectively and are responsive in social situations, which may help maintain connections with charitable organizations. Brown and Taylor (2015) found that neuroticism, or low emotional stability, is negatively linked to donating time and money. Brown and Taylor (2015) also found that openness to experience is positively linked to charitable actions. Individuals high in openness are more likely to explore various charities and align their choices with personal values.

H4: There is a positive relationship between agreeableness and congruence.

H5: There is a positive relationship between openness and congruence.

Extraverts often choose charities that match their social identity and community ties (Zogaj et al., 2021), while conscientious people tend to select charities based on personal values and goals (Brown and Taylor, 2015).

H6: There is a positive relationship between extraversion and congruence.

H7: There is a positive relationship between conscientiousness and congruence.

According to Meer and Priday (2021), higher-income and higher-wealth households are more likely to donate to charity and in larger amounts.

H8: (a) There is a positive relationship between annual income and donation size. (b) There is a positive relationship between annual income and congruence.

Methodology and sample

Building on the theoretical framework and the hypotheses above, we conducted a survey study in collaboration with a partner organization that supports a network of charities in the Midwest, primarily focusing on fundraising.1 The organization provided grant funding that sponsored this academic research and a broad-based donor report based on the survey instrument. In addition to capturing demographic details of donors, the survey was designed to measure how donor personality, age, and income relate to congruence with nonprofit brand personality and giving behavior. To answer the research questions and eight hypotheses, the researchers collaborated with an organization that supports a variety of charities to develop a survey that measured donor philanthropy congruence. Partnering with an organization that supports multiple charities, the researchers developed a survey using a 14-item, 7-point Likert scale adapted from Aaker (1997). Participants rated charities on facets of traits including excitement, competence, sophistication, and ruggedness, and provided demographic and giving behavior information. The data offers insights into the congruence between ideal and perceived nonprofit brand personalities and the role that personality congruence plays in donor engagement, illustrating how audience perceptions actively contribute to brand meaning and engagement within a hyper-personalized integrated marketing communications environment.

To assess brand personality traits, the study applied Aaker (1997) Brand Personality Scale, a validated framework that identifies five key dimensions of brand personality broken down into 15 facets and used it to measure differences between participants’ perceptions of their actual charity and their ideal charity. The participants evaluated charities based on the degree to which they perceived the real and ideal charities to be aligned with the facets corresponding with the five factors (Sincerity, Excitement, Competence, Sophistication, and Ruggedness) represented in Aaker (1997) scale. The survey included items that related to the 15 facets that correspond with the five brand personality factors included in Aaker’s scale. To answer the research questions and seven hypotheses, the researchers collaborated with an organization that supports a variety of charities to develop a survey that measured donor philanthropy congruence. Partnering with an organization that supports multiple charities, the researchers developed a survey using a 14-item, 7-point Likert scale adapted from Aaker (1997). Participants rated charities on facets of traits including excitement, competence, sophistication, and ruggedness, and provided demographic and giving behavior information. The data offers insights into the congruence between ideal and perceived nonprofit brand personalities and the role that personality plays in donor engagement, illustrating how audience perceptions actively contribute to brand meaning and engagement within a hyper-personalized integrated marketing communications environment.

The survey received 497 total responses with respondents residing in 11 states with the vast majority residing in one of two Midwestern states. The survey instrument, implemented via Qualtrics, contained a total of 254 questions. Due to the large scale nature of the survey requirements of the partner organization, it was necessary to keep research elements as concise as possible. As a result, we limited our inquiry to charity brand image to Aaker’s 15 facets as opposed to the full 44 items in the assessment. Participants were given a prompt to ascertain the individual donor’s ideal brand image across the 14 facets. Individuals were also asked to identify an actual charity that they donated to. The exact prompts are in Appendix A.

To assess brand personality traits, the study applied Aaker (1997) Brand Personality Scale, a validated framework that identifies five key dimensions of brand personality broken down into 15 facets and used it to measure differences between participants’ perceptions of their actual charity and their ideal charity. The participants evaluated charities based on the degree to which they perceived the real and ideal charities to be aligned with the facets corresponding with the five factors (Sincerity, Excitement, Competence, Sophistication, and Ruggedness) represented in Aaker (1997) scale. The survey included items that related to the 15 facets that correspond with the five brand personality factors included in Aaker’s scale.

In addition to the brand personality items, we also included the BFI-10. Although the BFI-10 is a shorter inventory for testing the five-factor personality construct, it still retains significant levels of reliability and validity (Rammstedt and John, 2007). The abbreviated ten-item five-factor scale was selected because the survey was already lengthy as it included two versions of Aaker’s scale measuring actual and ideal brand personalities. Along with gathering information about the branding of the charitable organization, participants also provided the answers to basic demographic items and questions related to their charitable giving. Our research was approved by the North Dakota State University IRB (protocol #AG16145) and granted exempt status under Category 2b for studies using educational tests, surveys, interviews, or public observations without identifiable information or risk of harm.

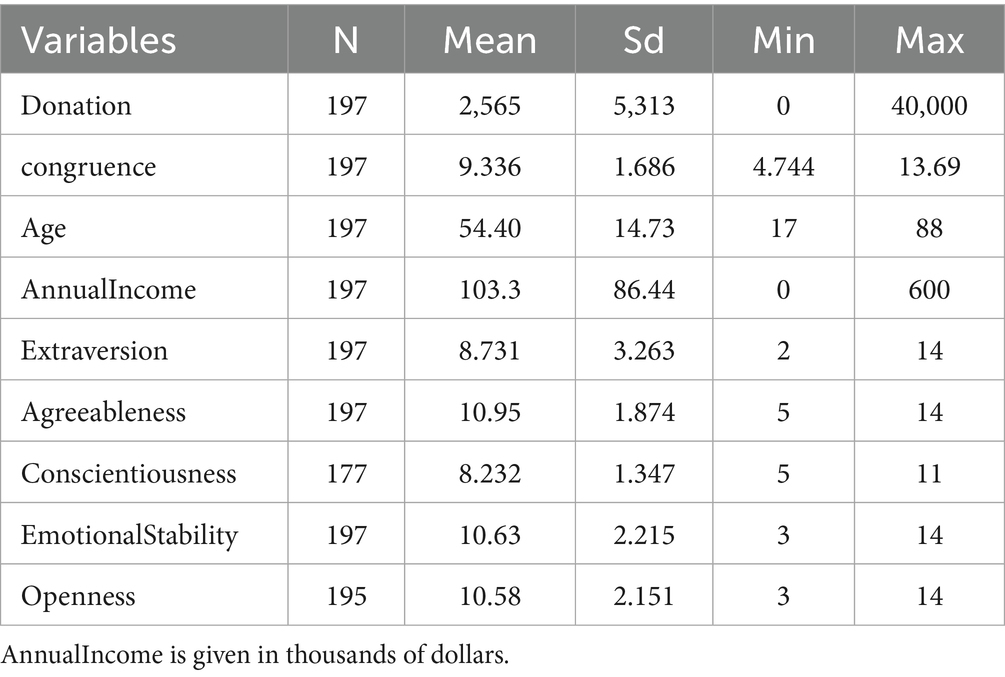

The researchers gathered a total of 497 responses, however many of these responses were incomplete. After deleting responses which did not answer our core questions needed for this study, we were left with 197 responses. The average respondent age was 54.4 years old. Regarding education, 51% reported having completed a bachelor’s degree, 25% reported possession of a master’s degree, 10% had some college or less, and 15% reported possession of a doctorate or professional degree. Respondents reported a combined total net worth of $169,440,576,2 resulting in an average net worth of $1,065,664. The distribution of net worth was highly skewed, as the median respondent reported a net worth of $500,000. Reported net worth ranged from a minimum of –$24,000 to a maximum of $15,000,000. Average annual income was $103,265.40. Summary statistics for all study variables are presented in Table 2.

Congruence between a donor’s ideal charity Brand Personality and the perceived Brand Personality of the real charity the donor identified is measured as a transformation of the Euclidian distance between these two measures. For each of the 15 facets we subtract the real brand personality from the ideal and square it. These squared differences are then summed for all 15 facets. The Euclidian distance between the two is then the square root of this sum. This is expressed mathematically in Equation 1.

The greater is congruence between the Real and Ideal brand personality the smaller is this distance. We aim to transform this distance into a measure where higher values represent greater congruence. This can be accomplished by taking the negative of the distance between Real and Ideal. However, for part of our analysis we will also be log transforming our data and it is not possible to log transform a variable that takes on negative values. Our final measure of congruence for individual is calculated as the maximum over all individuals of the distance between Real and Ideal minus the distance for individual plus one. This is expressed mathematically according to Equation 2.

The variable Congruence then has a minimum value of 1 representing the lowest congruence in the sample with the highest value being given to the individual with the smallest distance between Real and Ideal. This congruence measure has the intuitive appeal of increasing as the distance between Real and Ideal gets smaller and takes on values that can be log transformed.

Results

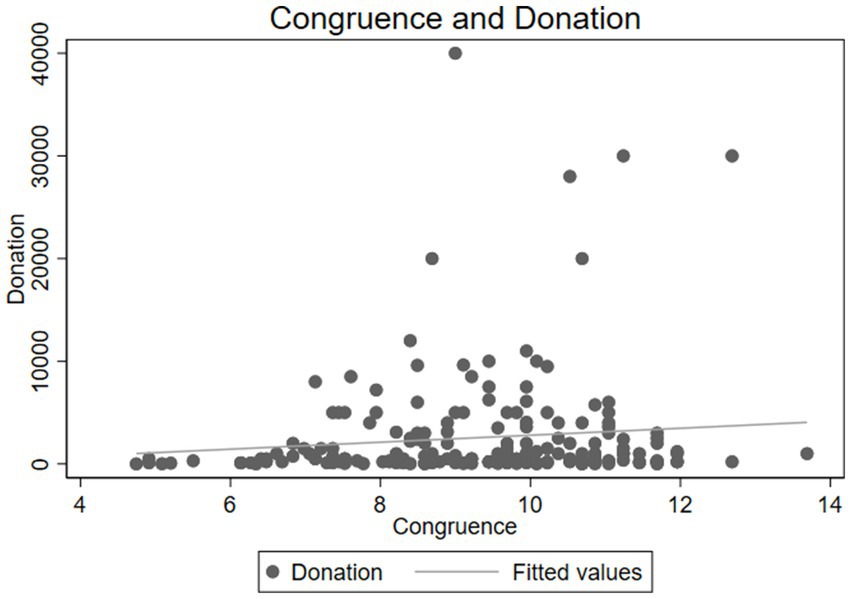

The simple and positive relationship between congruence and donations is easy to visualize in a scatterplot between congruence on the horizontal axis and donation amount on the vertical axis. Figure 2 shows such a scatterplot and also has the line of best fit inserted. While the data demonstrate a large amount of variation it is evident that the line of best fit has a positive slope which reflects the positive relationship between congruence and the amount donated to a charity by an individual.

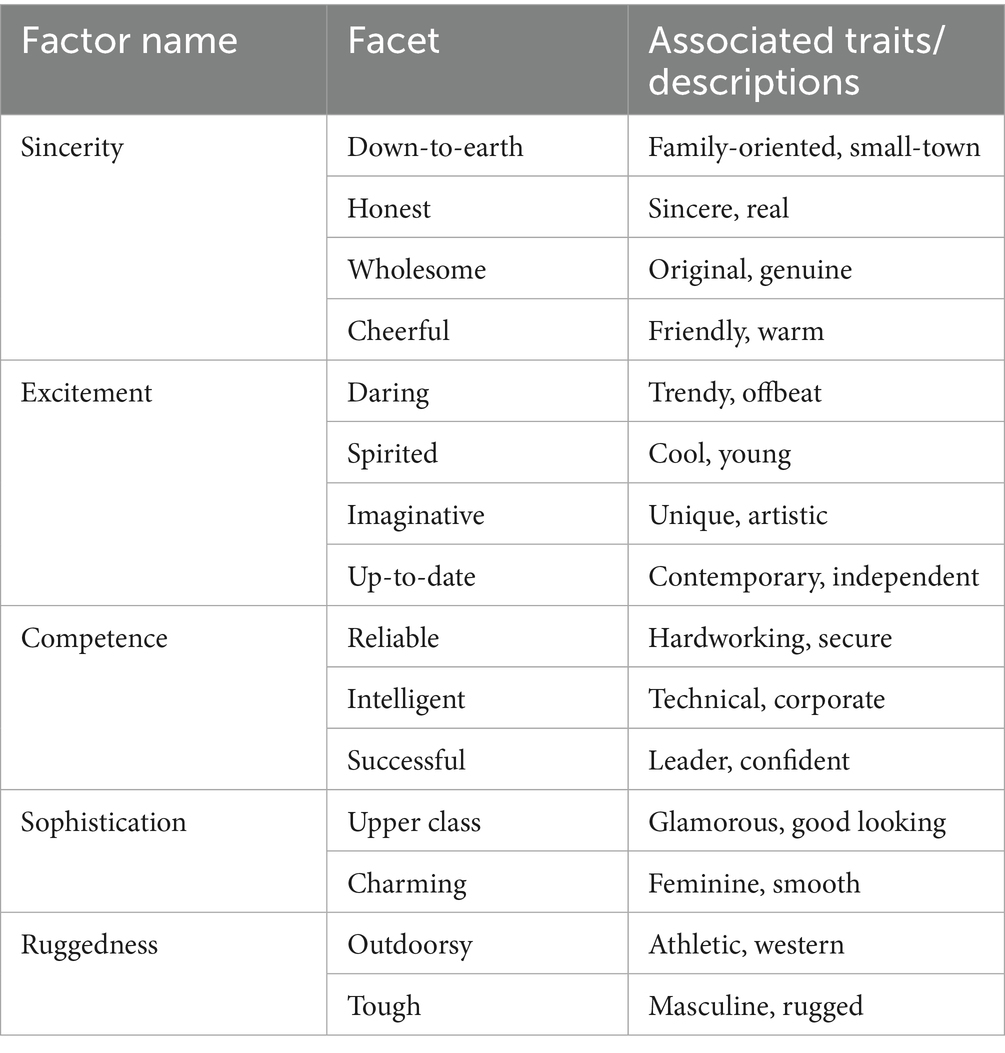

To examine the effect of congruence between Ideal and Real charity brand personality on charity donations more rigorously, a series of linear regressions were estimated. We also posit that there is concern for issues of endogeneity of congruence in such regression analysis. While it is plausible that a highly congruent match between donor ideal and the actual brand personality may cause higher donations, it is also plausible that donors who contribute larger sums specifically seek out charities whose real brand personality is highly congruent to their ideal brand personality. This suggests the causal path, and source of correlation could be from donations to congruence. To address this issue, we employ two-stage least squares regression using donor Age and Emotional Stability as instruments for congruence.

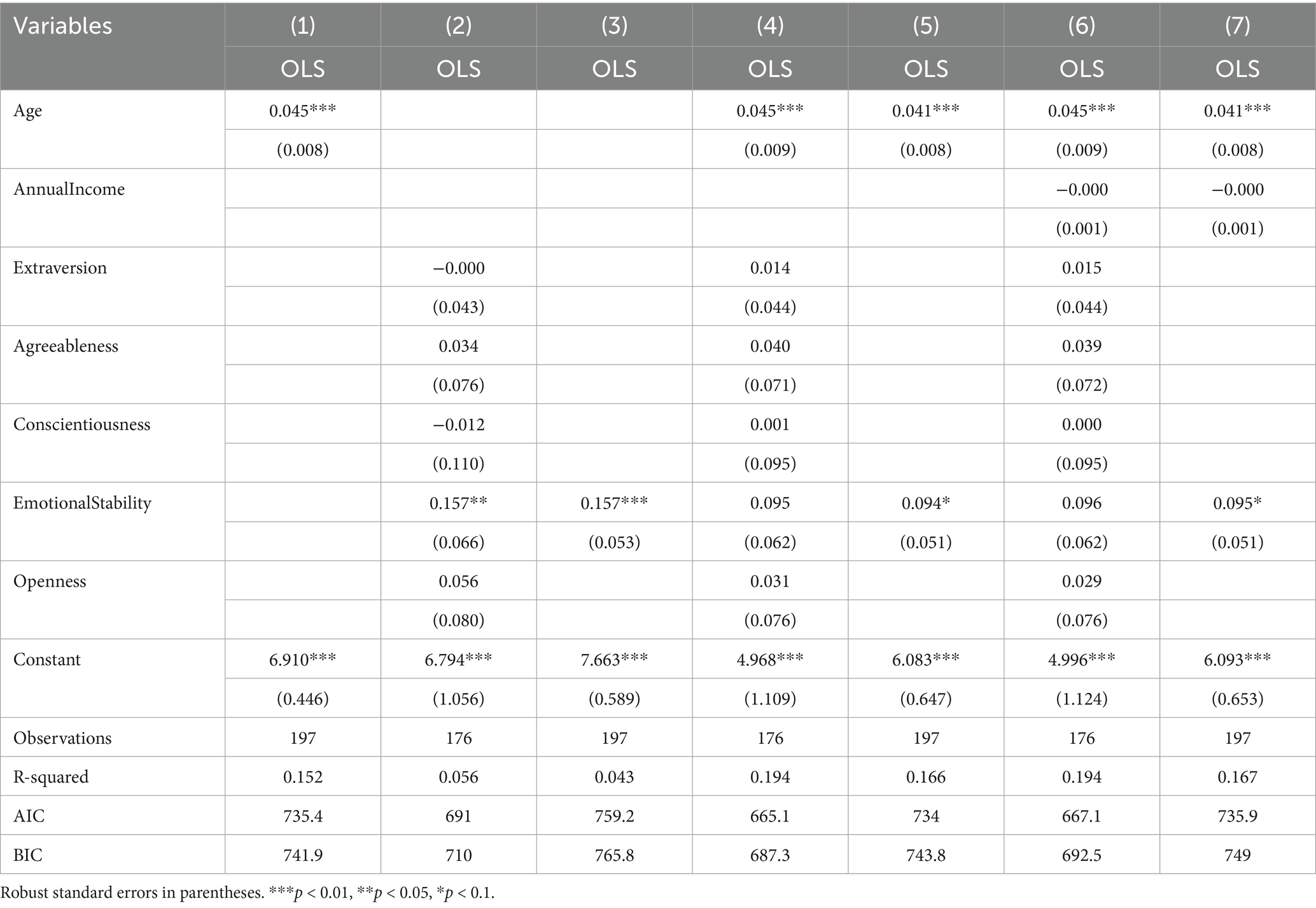

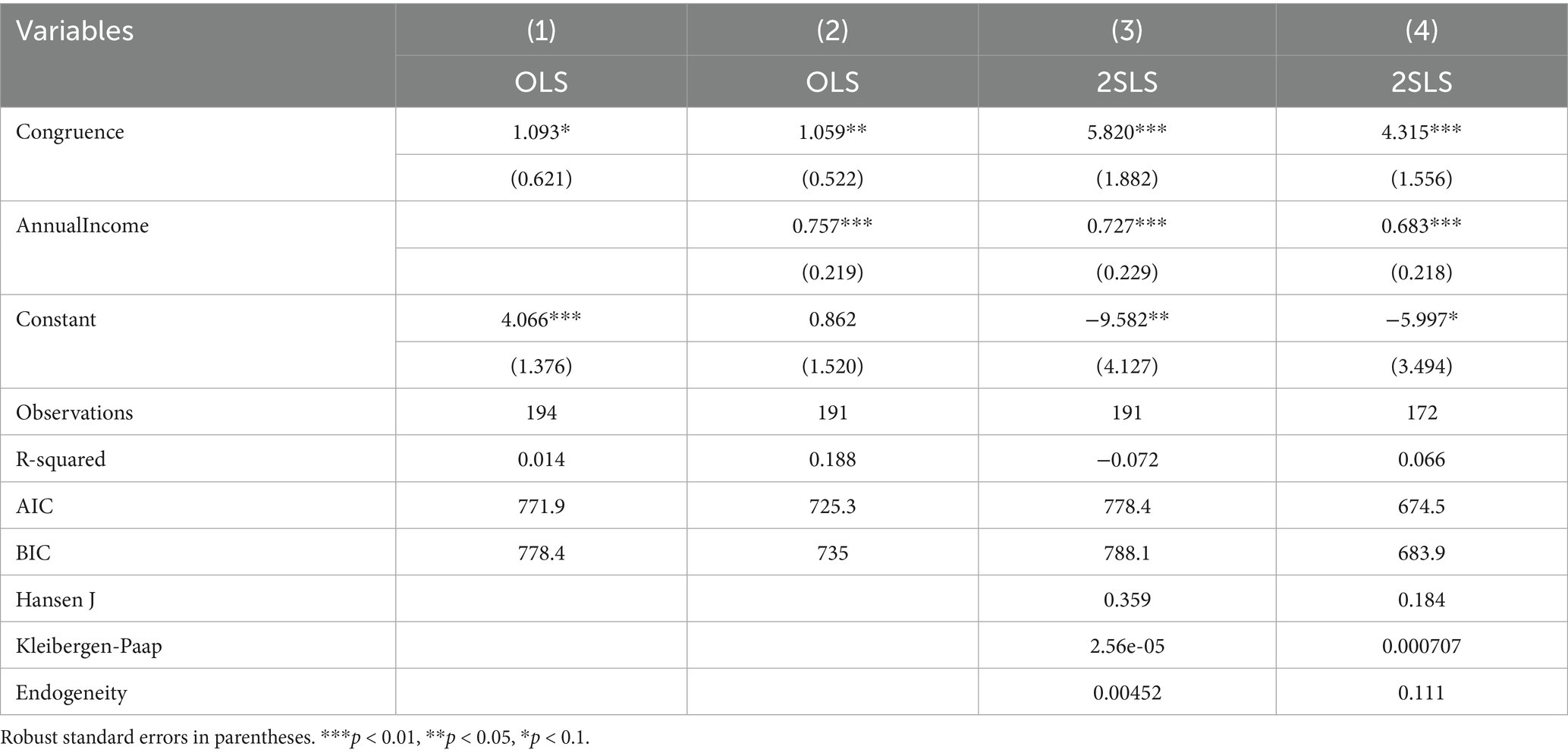

Table 3 gives estimation results for a variety of OLS regression specifications with congruence as the dependent variable.3 Independent variables included in the regressions are Age, Annual Income, and each of the Big Five personality trait scores. These results reveal that the main predictor of congruence is donor age thus confirming hypothesis H2. Older and more experienced donors are better equipped to find a charity that aligns its brand personality closely to their ideal. Annual Income and donor personality traits are largely uncorrelated with congruence. The exception is the donor personality trait of Emotional Stability which has a small positive correlation with congruence. Thus, hypothesis H3 is supported but hypotheses H4-H7 are not supported. The AIC and BIC criterion suggest that model (4) is the best model to predict congruence despite the inclusion of many insignificant variables. Model (5) includes only the statistically significant variables of Age and Emotional Stability.

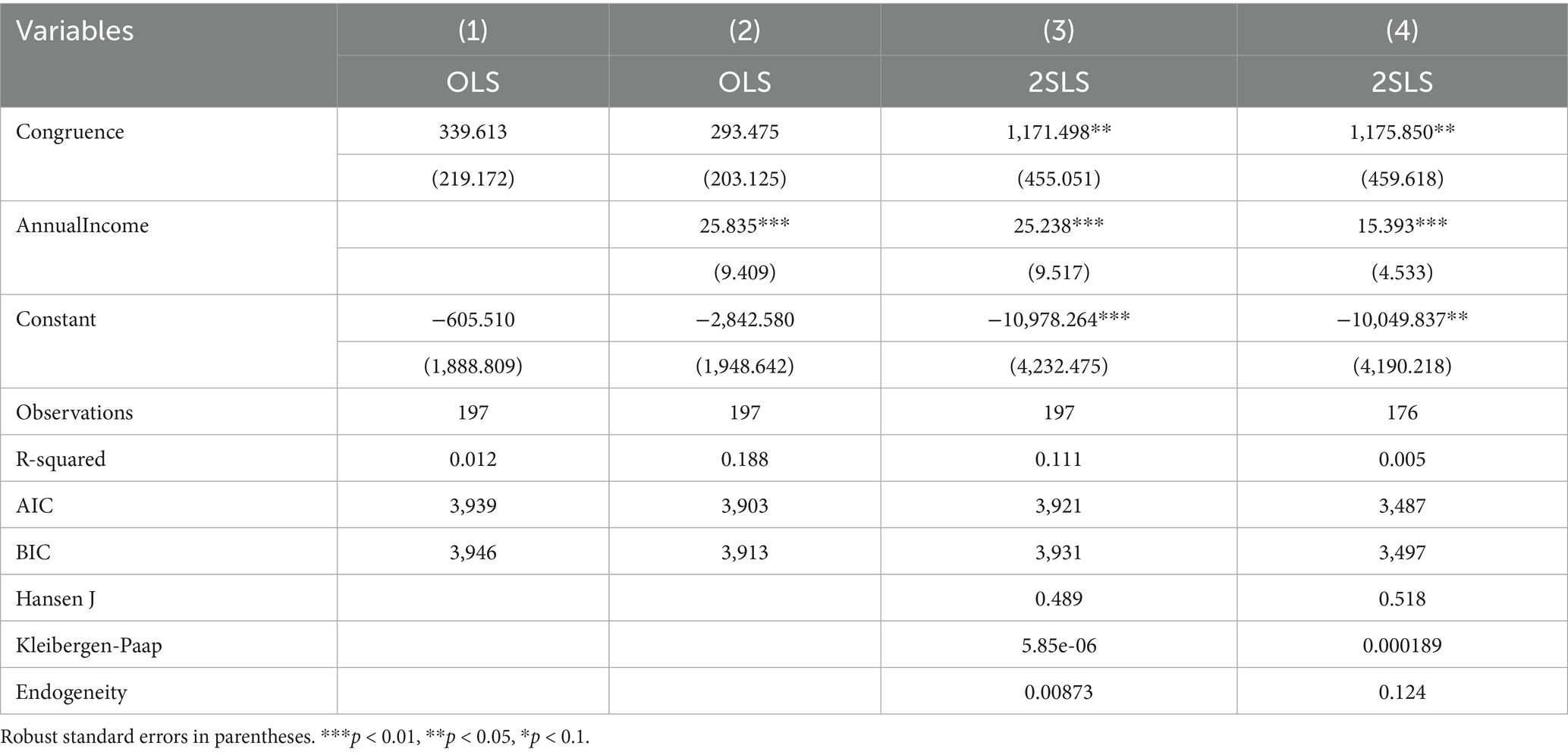

Table 4 provides estimation results which test the effect of donor congruence on the size of an individual’s charity donation. Columns (1) and (2) both report results from OLS regressions and reveal a positive, albeit statistically insignificant, relationship. The effect of congruence on donation is mitigated by the inclusion of the Annual Income variable, in column (2), which also has a positive and statistically significant correlation with donation size. Column (3) reports regression results for 2SLS using both Age and Emotional Stability of the donor as instrumental variables for congruence. Instrumental variables are valid if two conditions hold. Firstly, the instrumental variables must have the statistical strength to predict the variable they are instrumenting. They must have sufficient correlation so as to be relevant. Secondly, they must be valid. A valid instrument must meet the exclusion criterion meaning that the instruments themselves are not correlated with the error term of the regression. This is achieved when the instrumental variables are not correlated with the dependent variable, donation size. In the 2SLS regression of model (3), the magnitude of the effect of congruence is much greater that OLS and statistical significance at the 5% level is achieved. Table 4 also provides diagnostic tests of the strength and validity of our instrumental variables. The Hansen J test statistic has a p-value of 0.489 which allows us to accept the null hypothesis that our instruments are valid and uncorrelated with the error term. The Kleibergen-Paap test statistic is a test with a null hypothesis that our equation is under identified or has weak instruments. Rejection of the null provides evidence that our instruments are relevant. This test statistic has a p-value that is very close to zero leading us to reject the null. We further report the p-value of the Durbin–Wu–Hausman test for endogeneity of Congruence. A p-value of 0.00873 allows us to reject the null hypothesis and conclude that endogeneity is indeed a problem that must be addressed. Because of this, the 2SLS model would be the appropriate one for inference as opposed to those produced from standard OLS. We additionally include a second 2SLS model in column 4. Model (4) differs from model (3) in that all 5 personality traits along with Age are used as instrumental variables predicting congruence. This is informed by the low AIC and BIC of model (4) reported in Table 3. The results for model (4) are nearly identical to model 3 with both providing strong evidence in support of our main hypothesis of the study, H1. Congruence has a large positive effect on individual donation size. There is also support for hypothesis H8 in the Table 4 output. Annual income is positively associated with individual donation size.

To further explore the relationship between congruence and charity donations we also run the same regression analysis after taking log transformations of the data. This allows us to explore the possibility of non-linearities in the relationships and allows for the interpretation of coefficient estimates as elasticities. Again, Age and Emotional Stability are satisfactory predictors of Congruence as revealed in the regression out presented in Table 5 which is analogous to the output of Table 3. With a coefficient estimate of 0.233 for the variable age, a 10% increase in Age (increasing from 54.4 years of age to 59.84) results in a 2.33% increase in Congruence. Table 6 then reports regression models using logged donations as the dependent variable analogously to Table 4. Columns (1) and (2) report OLS results with columns (3) and (4) reporting 2SLS model results using the same instruments as columns (3) and (4) in Table 4. With log transformed data, the effect of Congruence on charity donations are even stronger with statistical significance at the 1% level using 2SLS as reported in columns (3) and (4). The coefficient estimate of 5.82 shows that a 2.5% increase in congruence, as would result from roughly a 10% increase in Age from Table 5 results, leads to a 14.55% increase in individual charity donation size. At the mean donation size of $2,565, a 14.55% increase in donations would amount to $374.21 which is approximately 7% of the standard deviation in donations. This demonstrates the magnitude of the effect of Brand Personality congruence with individual Ideal on charitable donations. Diagnostic tests again confirm the necessity, strength, and validity of the instrumental variables used in the 2SLS regressions.4

Discussion

When a nonprofit’s brand identity reflects a donor’s ideal brand image, donors will be more inclined to give generously. This study emphasizes the strategic importance of brand personality and the alignment between donors’ ideals and nonprofit branding. In doing so, this research moves beyond the study of donor static personality traits and addresses calls for more dynamic and nuanced models of donor-brand alignment (Kumar and Chakrabarti, 2023). Our results demonstrate the importance of emotional engagement and match in promoting charitable behavior, aligning with self-congruence theory (Zogaj et al., 2021) and the focus on emotional brand value in cause-related marketing (Pereira et al., 2024). We utilized a two-stage least squares approach to estimate the effect of congruence on donations. Our research indicates that congruence is a measurable factor driving charitable giving, rather than an abstract attitudinal variable.

By conceptualizing congruence as the distance between a donor’s ideal brand perceptions and nonprofits’ real brand identities, these findings move our understanding beyond binary notions of “fit” (Sirgy, 1982). This distance-based approach aligns with research focusing on brand identity gaps (Aaker, 1997) and adds nuance to self-congruence theory while providing actionable steps for enhancing nonprofit branding.

Secondary findings revealed that donor age and emotional stability are associated with higher perceived congruence. Age emerges as the strongest predictor of congruence between donors’ perceptions of their ideal charity and their evaluations of actual charitable organizations. Older and more experienced donors report a closer alignment between their ideals and a nonprofit’s brand identity. Emotional stability also shows a modest positive relationship with congruence, suggesting that donors with greater emotional regulation engage with brand alignment more deliberately and consistently. Even though these results offer valuable insights into which donors are more likely to experience congruence, they should be interpreted as a supportive context rather than the primary contribution of the study.

Prior research has focused mainly on intrinsic donor factors such as social responsibility, empathy, and issue awareness (Bennett, 2003), as well as demographics like income and education (Chrenka et al., 2003). While these traits help segment donor populations, they tend to be relatively stable and outside of nonprofit control. These findings support the dynamic and strategic role that brand identity plays in nonprofit marketing and communications strategy. Understanding the importance of brand identity is essential for nonprofits, as engaging audiences in the branding process can lead to increased donations, which is the goal of most philanthropic communications campaigns. By strategically developing brand messaging, tone, and visual elements to resonate with potential donors’ values and ideals, organizations can forge a strong connection and ultimately increase their contributions. This research shows that value-driven nonprofit brand alignment extends beyond traditional demographic targeting by providing a practical mechanism for increasing donations.

These findings support the two-stage model of charitable giving proposed by van Dijk et al. (2019), wherein universal personal values drive general donation behavior. However, the choice of nonprofit hinges on value congruence with organizational branding. They also connect with Zogaj et al.’s (2021) conclusion that ideal self-congruence and emotional involvement more strongly predict donor loyalty than actual self-congruence alone. Together, this body of evidence supports value-driven brand alignment as a core mechanism shaping donor decision-making. In addition, Social Identity Theory (Tajfel and Turner, 1979) suggests that donors’ sense of belonging is likely increased when a philanthropy reflects their ideals. This group-level affirmation increases both self-congruence and the “warm-glow” satisfaction from giving (Andreoni, 1990). This suggests that a combination of these two factors makes congruence a doubly potent driver of philanthropic giving.

Notably, the dependent variable in this study was a self-report of money donated, not donor engagement. By focusing on reported donation behavior rather than attitudinal or intention-based measures, the results provide direct evidence of the financial impact of donor–brand congruence. This focus on reported donations strengthens the case for value-driven branding as a practical tool for increasing charitable revenue.

Our findings can also be viewed through the lens of signal theory. As donors rarely directly experience the services that nonprofits provide, the organizational quality and value alignment may be uncertain (Connelly et al., 2010). Nonprofit brand personality and real-ideal congruence serve as signals that communicate organizational values, trustworthiness, and credibility. When a nonprofit brand is congruent with an ideal organization, it fosters feelings of organizational connection and reduces donor uncertainty. Therefore, real-ideal congruence functions as a psychological construct, consistent with self-congruence, and as a signal that provides observable cues about donating. When deciding on a message’s tone and visual identity, marketers should use this integrated approach to develop a communication strategy that aligns with donor ideals. Moving forward, research should widen its scope and methodological approach to understand how congruence forms across cultures, identities, and branding elements. The following section addresses these concepts in greater depth.

Limitations and future research

These findings have several limitations. The cross-sectional design limits the ability to make causal claims about how donor–brand congruence develops and affects giving over time; longitudinal studies would be needed to track changes and impacts. Further, this study relies on self-reported survey data instead of verified donation records (Chapman et al., 2025b). Future studies could partner with charities to obtain this information. The sample lacks cultural and geographic diversity, so future research should include non-Western contexts to assess global generalizability, as discussed by Kumar and Chakrabarti (2023). In addition, the generalizability of this research may also be limited by the sample which was comprised of older adults in a higher-than-average income category. Moreover, while Emotional Stability emerged as a noteworthy psychological predictor, further exploration of other traits such as altruism and moral identity may reveal stronger or complementary influences on donor-brand alignment and giving behavior. In addition, this study focused only on the congruence between the donor’s ideal charity brand and their perceived brand of an organization that they donate to. Future studies could compare congruence among a wider variety of nonprofits and geographic locations.

Future research could also examine the congruence between individual donor personality traits and perceived nonprofit branding. This type of research could reveal new pathways for increasing donations. Using qualitative, mixed-methods, or experimental approaches may offer more detailed information about how donors understand brand messaging and internalize nonprofit values. This information could assist nonprofits in identifying which branding elements, such as tone, symbolism, or storytelling, are most influential in establishing alignment and fostering continued engagement and financial support for the organization.

Although these limitations provide areas for future research, they also outline the importance of understanding how donor–brand congruence can be strategically employed. Building on these findings, several practical implications emerge for nonprofits seeking to create authentic, value-driven brand identities that foster stronger donor relationships and support. These findings also demonstrate the importance of studying donor-brand congruence as both a psychological phenomenon (i.e., identity and warm glow) and a signal of organizational credibility.

Implications

Theoretical implications

This study contributes to donor behavior theory by showing that congruence between a donor’s ideal brand and a nonprofit’s brand personality directly influences reported donation amounts. It extends Aaker (1997) brand personality framework and supports self-congruence theory (Zogaj et al., 2021) by empirically confirming the aspirational role of brand congruence in nonprofit contexts. Drawing from cause-related marketing research (Pereira et al., 2024), this study provides a comprehensive model that includes the relationship between donor identity, organizational branding, and giving. The findings open pathways for future research to explore these mechanisms across contexts, helping to develop more inclusive and dynamic models of donor-brand relationships and charitable behavior.

First, these results emphasize the strategic role of brand identity in nonprofit fundraising. In this context, brand identity communicates more than just an organizational mission. Branding operates as a differentiating mechanism in increasingly competitive fundraising environments. By clarifying and consistently projecting a distinctive personality, nonprofits can position themselves as aligned with donor ideals (Grossman, 1994; Amujo and Laninhun, 2013; Mirzaei et al., 2021).

Second, this study reveals the centrality of value-driven alignment. While demographics and intrinsic donor traits remain useful for segmentation, the findings show that congruence with aspirational values is a strong predictor of philanthropic giving. This contribution complements recent work in philanthropic marketing that emphasizes the importance of emotional brand value in shaping donor engagement (Pereira et al., 2024).

Third, this research advances the discipline by providing empirical evidence supporting congruence effects. By using a two-stage least squares strategy, the results reveal that congruence is not merely an abstract attitudinal variable but a measurable predictor of donations. This contribution bolsters the argument that congruence is both actionable and observable for nonprofit marketers (van Dijk et al., 2019).

Practical implications

In the nonprofit sector, congruence plays a uniquely powerful role because donors engage through values and identity rather than product benefits and features. Unlike commercial contexts, nonprofit-donor congruence influences not only loyalty but also perceptions of legitimacy and mission authenticity. Congruence could also amplify the “warm glow” effect, or the intrinsic satisfaction that donors experience when their giving reflects both their altruism and self-identity (Andreoni, 1990; Bekkers and Wiepking, 2011). Building on these insights, nonprofits can apply a congruence-based branding approach through a structured “Diagnose-Design-Deliver” framework that translates theory into practical steps while focusing on emotional connections and values. It also supports social identity formation as donors perceive themselves as part of a group that shares the organizations values (Tajfel and Turner, 1979).

Diagnose: Nonprofits should begin by assessing current donor–brand alignment through surveys, interviews, and digital engagement analytics. Research shows that brand image and perceived fit significantly influence charitable giving (Michel and Rieunier, 2012). Likewise, donor-brand value increases trust and the willingness to give (Van Dijk et al., 2019). When congruence is high, the “warm glow” effect is stronger, reinforcing the emotional rewards for donating (Grossman and Levy, 2024). Gregory et al. (2020) further demonstrate that brand salience and attitude guide donor decision-making, reinforcing the importance of systematic brand evaluation to identify gaps in brand congruence. Misalignment in tone, symbolism, or authenticity indicates that messaging should be adjusted. Once a lack of congruence is identified, nonprofits can proceed to the branding design stage, where understanding of the audience informs authentic messaging.

Design: By using a brand evaluation, organizations can develop authentic message strategies that communicate emotional depth and aspirational values. This approach to nonprofit branding extends beyond demographic segmentation and emphasizes messaging that resonates with donors. Cause-related marketing campaigns, narrative storytelling, and co-created brand identities can all reinforce congruence and strengthen engagement. Social media is essential in this context as nonprofits can cultivate community by inviting donors into the brand storytelling process (Lovejoy et al., 2012; Bortree and Seltzer, 2009; Prahalad and Ramaswamy, 2004). The DART model of Dialog, Access, Risk Assessment, and Transparency (Prahalad and Ramaswamy, 2004) provides a framework for maintaining brand congruence. By applying the DART model, philanthropies can establish trust and encourage donors to see congruence, which would enhance donor engagement and loyalty (Banik and Rabbanee, 2023). By involving donors in nonprofit marketing (Muntinga et al., 2011; Crawford and Jackson, 2019), organizations can develop a brand that cuts through the cluttered social media environment and creates authentic, participatory relationships. After creating authentic campaigns that involve the audience, nonprofits must deliver them ethically and effectively.

Deliver: Organizations should develop communications campaigns using congruent nonprofit branding that balances personalization and ethical responsibility. While donors appreciate personalization, protecting privacy and avoiding manipulation safeguards donor trust. In the context of nonprofits, congruence is about maintaining trust in the organization’s mission and matching donor preferences. A lack of congruence could be perceived negatively as a “mission drift,” undermining legitimacy and reducing donations (Suykens et al., 2025). When donors view the nonprofit brand as an extension of their own identity, loyalty and advocacy follow (Martínez and Del Bosque, 2013; Lai and Nguyen, 2025). Congruent branding can maintain “warm glow” when donors repeatedly experience satisfaction from giving to organizations that share their values. Continuous measurement of congruence through donor feedback and donations allows for continuous message refinement. Delivering marketing messages with transparency and ethical caution (such as safeguarding privacy and gathering data in a responsible manner) ensures long-term congruence and sustainability within increasingly competitive philanthropic markets.

By using the Diagnose–Design–Deliver framework, nonprofits can move beyond generic branding advice to adopt a systematic process. By identifying incongruent branding, designing authentic messaging, and prioritizing transparency and trust, organizations not only cultivate donor loyalty and “warm glow” but also employ congruence as a powerful tool for driving nonprofit donations (Grossman and Levy, 2024).

Conclusion

The power of brand congruence lies in its ability to transform donor perceptions into measurable fundraising success, ultimately leading to increased donations. Our findings also indicate that donor age and emotional stability significantly influence how well donors perceive alignment with nonprofit brands. By weaving these characteristics into their marketing communications campaigns, nonprofits can more effectively engage existing and prospective supporters, strengthen relationships, and ultimately increase donations.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by NDSU IRB Protocol #AG16145 was certified as exempt under category 2b—for research involving educational tests, surveys, interviews, or observation of public behavior. This category applies when the research involves collecting information that is recorded in such a way that the subjects cannot be readily identified directly or indirectly through linked identifiers. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The ethics committee/institutional review board waived the requirement of written informed consent for participation from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin because Informed consent was waived under IRB Category 2b because the study involves minimal risk to participants. Specifically, the survey was anonymous and did not collect identifiable private information. Requiring signed consent forms would introduce a new risk: it could inadvertently link participants to their responses, thereby compromising anonymity and increasing the potential for harm. The waiver helps protect participants’ privacy by avoiding the collection of identifying information. All required elements of informed consent were provided within the survey introduction, and participation was entirely voluntary.

Author contributions

EC: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. JJ: Methodology, Investigation, Resources, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Data curation, Formal analysis.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Generative AI (ChatGPT by OpenAI) was used as a writing support tool during the preparation of this manuscript to improve clarity, transitions, and tone. All content was written by the author, and AI-generated suggestions were critically reviewed, adapted, or omitted based on scholarly judgment. The final manuscript reflects the author’s original analysis, synthesis, and revisions. Generative AI was not used for data analysis, interpretation of findings, or methodological design.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^Data set is available on request; however, the data set cannot be made publicly available.

2. ^Only 159 of 197 responses reporting.

3. ^We calculated the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) for each regression model. All VIFs were approximately 1 indicating no concerns of multicollinearity.

4. ^While reported, the r-squared statistic does not have meaning in the 2SLS specifications as in OLS.

References

Aaker, D. A., and Biel, A. (2013). Brand equity and advertising: Advertising’s role in building strong brands. New York: Psychology Press.

Aaker, J., and Fournier, S. (1995). A brand as a character, a partner and a person: three perspectives on the question of brand personality. Advan. Consumer Res. 22, 391–395.

Alpert, F. H., and Kamins, M. A. (1995). An empirical investigation of consumer memory, attitude, and perceptions toward pioneer and follower brands. J. Mark. 59, 34–45.

American Psychological Association. (2017). Personality. Available online at: https://www.apa.org/topics/personality/ (Accessed July 31, 2025).

Amujo, C. O., and Laninhun, B. A. (2013). Organisational brand identity management: a critical asset for sustainable competitive advantage by non-profits. Third Sector Review 19, 97–126.

Andreoni, J. (1990). Impure altruism and donations to public goods: a theory of warm-glow giving. Econ. J. 100, 464–477.

Ang, S. H., and Lim, E. A. C. (2006). The influence of metaphors and product type on brand personality perceptions and attitudes. J. Advert. 35, 39–53. doi: 10.1080/00913367.2006.10639226

Banik, S., and Rabbanee, F. K. (2023). Value co-creation and customer retention in services: Identifying a relevant moderator and mediator. J. Consum. Behav. 22, 174–189. doi: 10.1002/cb.2150

Bart, C. K., and Tabone, J. C. (1998). Mission statement rationales and organizational alignment in the not-for-profit health care sector. Health Care Manag. Rev. 23, 54–69.

Behnke, M. (2025). “How self-expressive human values boost brand appeal?” in ed. M. Behnke, In one word: The power of razor-sharp brand positioning to lower costs and improve results (Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland), 83–94. doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-88202-9_6

Bekkers, R., and Wiepking, P. (2011). A literature review of empirical studies of philanthropy: eight mechanisms that drive charitable giving. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 40, 924–973. doi: 10.1177/0899764010380927

Bénabou, R., and Tirole, J. (2006). Incentives and prosocial behavior. Am. Econ. Rev. 96, 1652–1678. doi: 10.1257/aer.96.5.1652

Bennett, R. (2003). Factors underlying the inclination to donate to particular types of charity. Int. J. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Mark 8, 12–29.

Bennett, R. (2005). Competitive environment, market orientation, and the use of relational approaches to the marketing of charity beneficiary services. J. Serv. Mark. 19, 453–469. doi: 10.1108/08876040510625963

Bjälkebring, P., Västfjäll, D., Dickert, S., and Slovic, P. (2016). Greater emotional gain from giving in older adults: age-related positivity bias in charitable giving. Front. Psychol. 7:846. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00846

Black, I., and Veloutsou, C. (2017). Working consumers: co-creation of brand identity, consumer identity and brand community identity. J. Bus. Res. 70, 416–429. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.07.012

Bleidorn, W., Stahlmann, A. G., Orth, U., Smillie, L. D., and Hopwood, C. J. (2025). Personality traits and traditional philanthropy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 129, 363–383. doi: 10.1037/pspp0000556

Bortree, D. S., and Seltzer, T. (2009). Dialogic strategies and outcomes: An analysis of environmental advocacy groups, and Facebook profiles. Public Relat. Rev. 35, 317–319. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2009.05.002

Bray, I. (2013). Effective fundraising for nonprofits: Real-world strategies that work. Berkeley, CA: Nolo.

Brown, S., and Taylor, K. (2015). Charitable behaviour and the big five personality traits: Evidence from UK panel data, IZA discussion papers, no. 9318, Institute for the Study of labor (IZA), Bonn.

Cai, M., Caskey, G. W., Cowen, N., Murtazashvili, I., Murtazashvili, J. B., and Salahodjaev, R. (2022). Individualism, economic freedom, and charitable giving. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 200, 868–884. doi: 10.1016/j.jebo.2022.06.037

Chapman, C. M., Spence, J. L., Hornsey, M. J., and Dixon, L. (2025a). Social identification and charitable giving: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. doi: 10.1177/08997640251317403

Chapman, C. M., Thottam, A. K., Schultz, T., McKay, K. T., and Gulliver, R. (2025b). Measuring charitable giving: how to capture charitable behavior in philanthropy research. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. doi: 10.1177/08997640251351548

Charities Aid Foundation. (2021). World giving index 2021. Available online at: https://www.cafonline.org/about-us/publications/2021-publications/caf-world-giving-index-2021 (Accessed July 31, 2025).

Charities Aid Foundation. (2024). World giving index 2023. Available online at: https://www.cafonline.org/docs/default-source/updated-pdfs-for-the-new-website/world-giving-index-2023.pdf (Accessed July 31, 2025).

Cheema, A., and Kaikati, A. M. (2010). The effect of need for uniqueness on word of mouth. J. Mark. Res. 47, 553–563. doi: 10.1509/jmkr.47.3.553

Chrenka, J., Gutter, M. S., and Jasper, C. (2003). Gender differences in the decision to give time or money. Consum. Interes. Annu. 40, 1–4.

Connelly, B. L., Certo, S. T., Ireland, R. D., and Reutzel, C. R. (2010). Signaling theory: a review and assessment. J. Manag. 37, 39–67. doi: 10.1177/0149206310388419

Crawford, E. C., and Jackson, J. (2019). Philanthropy in the millennial age: trends toward polycentric personalized philanthropy. Indep. Rev. 23, 551–568.

Das, E., Kerkhof, P., and Kuiper, J. (2008). Improving the effectiveness of fundraising messages: the impact of charity goal attainment, message framing, and evidence on persuasion. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 36, 161–175. doi: 10.1080/00909880801922854

Dijk, M.van, Herk, H., and Prins, R. (2019). Choosing your charity: the importance of value congruence in two-stage donation choices J. Bus. Res. 105 283–292 doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.08.008

Dolich, I. J. (1969). Congruence relationships between self images and product brands. J. Mark. Res. 6, 80–84.

Freling, T. H., and Forbes, L. P. (2005). An empirical analysis of the brand personality effect. J. Prod. Brand. Manag. 14, 404–413. doi: 10.1108/10610420510633350

Ghauri, K., Ahmad, G., and Amin, M. A. (2025). Building consumer trust through influencer authenticity: a content analysis of sponsored posts on Instagram. J. Bus. Manag. Res. 4, 78–94.

Glazer, A., and Konrad, K. A. (1996). A signaling explanation for charity. Am. Econ. Rev. 86, 1019–1028.

Graeff, T. R. (1996). Using promotional messages to manage the effects of brand and self-image on brand evaluations. J. Consum. Mark. 13, 4–18.

Gregory, G., Ngo, L., and Miller, R. (2020). Branding for non-profits: explaining new donor decision-making in the charity sector. J. Prod. Brand. Manag. 29, 583–600.

Groenewold, D. A. (2025). The power of persuasion: Unlocking consumer loyalty on charity websites through personalized persuasive communication (Master’s thesis, University of Twente). University of Twente repository.

Grossman, P. J., and Levy, J. (2024). It’s not you (well, it is a bit you), it’s me: self-versus social image in warm-glow giving. PLoS One 19:e0300868. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0300868

Groza, M. P., and Gordon, G. L. (2016). The effects of nonprofit brand personality and self-brand congruity on brand relationships. Mark. Manag. J. 26, 117–129.

Hager, M., Rooney, P., and Pollak, T. (2002). How fundraising is carried out in US nonprofit organisations. Int. J. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Mark. 7, 311–324. doi: 10.1002/nvsm.188

Handy, F. (2000). How we beg: the analysis of direct mail appeals. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 29, 439–454. doi: 10.1177/0899764000293005

Hollenbeck, C. R., and Kaikati, A. M. (2012). Consumers’ use of brands to reflect their actual and ideal selves on Facebook. Int. J. Res. Mark. 29, 395–405. doi: 10.1016/j.ijresmar.2012.06.002

Holt, D. B. (2002). Why do brands cause trouble? A dialectical theory of consumer culture and branding. J. Consum. Res. 29, 70–90. doi: 10.1086/339922

Iglesias, O., Markovic, S., Bagherzadeh, M., and Singh, J. J. (2020). Co-creation: a key link between corporate social responsibility, customer trust, and customer loyalty. J. Bus. Ethics 163, 151–166. doi: 10.1007/s10551-018-4015-y

Jackson, J., and Beaulier, S. (2023). Economic freedom and philanthropy. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 214, 148–183. doi: 10.1016/j.jebo.2023.08.004

John, O. P., and Srivastava, S. (1999). “The big five trait taxonomy: history, measurement and theoretical perspectives” in Handbook of personality: Theory and research. eds. O. P. John and L. A. Pervin. 2nd ed (New York, NY: Guilford Press), 102–138.

Kelley, Н. Н., and Тhibaut, J. W. (1978). Interpersonal relations: A theory of interdependence. New York: Wiley, 3–24.

Khamitov, M., Wang, X., and Thomson, M. (2019). How well do consumer-brand relationships drive customer brand loyalty? Generalizations from a meta-analysis of brand relationship elasticities. J. Consum. Res. 46, 435–459. doi: 10.1093/jcr/ucz006

Kim, C. K., Han, D., and Park, S. B. (2001). The effect of brand personality and brand identification on brand loyalty: applying the theory of social identification. Jpn. Psychol. Res. 43, 195–206. doi: 10.1111/1468-5884.00177

Kressmann, F., Sirgy, M. J., Herrmann, A., Huber, F., Huber, S., and Lee, D. J. (2006). Direct and indirect effects of self-image congruence on brand loyalty. J. Bus. Res. 59, 955–964. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2006.06.001

Kuenzel, S., and Halliday, S. V. (2010). The chain of effects from reputation and brand personality congruence to brand loyalty: the role of brand identification. J. Target. Meas. Anal. Mark. 18, 167–176. doi: 10.1057/jt.2010.15

Kumar, A., and Chakrabarti, S. (2023). Charity donor behavior: a systematic literature review and research agenda. J. Nonprofit & Public Sect. Mark. 35, 1–46. doi: 10.1080/10495142.2021.1905134

Khalifa, S. A. (2012). Mission, purpose, and ambition: redefining the mission statement. J. Strateg. Manag. 5, 236–251. doi: 10.1108/17554251211247553

Lai, C. S., and Nguyen, D. T. (2025). The impact of perceived relationship investment and organizational identification on behavioral outcomes in nonprofit organizations: the moderating role of relationship proneness. Nonprofit Manag. Leadersh. 35, 527–542. doi: 10.1002/nml.21632

Lee, Z., and Bourne, H. (2017). Managing dual identities in nonprofit rebranding: an exploratory study. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 46, 794–816. doi: 10.1177/0899764017703705

Lee, Y. K., and Chang, C. T. (2007). Who gives what to charity? Characteristics affecting donation behavior. Soc. Behav. Pers. 35, 1173–1180. doi: 10.2224/sbp.2007.35.9.1173

Lee, Z., Spry, A., Ekinci, Y., and Vredenburg, J. (2024). From warmth to warrior: impacts of non-profit brand activism on brand bravery, brand hypocrisy and brand equity. J. Brand Manag. 31, 193–211. doi: 10.1057/s41262-023-00319-8

Ligas, M. (2000). People, products, and pursuits: Exploring the relationship between consumer goals and product meanings. Psychol Mark. 17, 983–1003.

Lim, H. S., Bouchacourt, L., and Brown-Devlin, N. (2021). Nonprofit organization advertising on social media: the role of personality, advertising appeals, and bandwagon effects. J. Consum. Behav. 20, 849–861. doi: 10.1002/cb.1898

Lin, L. Y. (2010). The relationship of consumer personality trait, brand personality and brand loyalty: an empirical study of toys and video games buyers. J. Prod. Brand. Manag. 19, 4–17. doi: 10.1108/10610421011018347

Louis, D., and Lombart, C. (2010). Impact of brand personality on three major relational consequences (trust, attachment, and commitment to the brand). J. Prod. Brand. Manag. 19, 114–130. doi: 10.1108/10610421011033467

Lovejoy, K., Waters, R. D., and Saxton, G. D. (2012). Engaging stakeholders through twitter: how nonprofit organizations are getting more out of 140 characters or less. Public Relat. Rev. 38, 313–318. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2012.01.005

Malär, L., Krohmer, H., Hoyer, W. D., and Nyffenegger, B. (2011). Emotional brand attachment and brand personality: the relative importance of the actual and the ideal self. J. Mark. 75, 35–52. doi: 10.1509/jmkg.75.4.35

Marquardt, A. J., Kahle, L. R., and Godek, J. (2015). “Values shopping: empirically examining the influence of brand values on consumer brand attitudes.” In: Proceedings of the 2007 academy of marketing science (AMS) annual conference (Cham: Springer), 108–108.

Martínez, P., and Del Bosque, I. R. (2013). Csr and customer loyalty: the roles of trust, customer identification with the company and satisfaction. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 35, 89–99. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2013.05.009