- 1Laboratory of Marine Ecology and Environmental Sciences, Institute of Oceanology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Qingdao, China

- 2College of Marine Sciences, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Qingdao, China

- 3Institute of Eco-Environmental Forensics, Shandong University, Qingdao, China

- 4State Key Laboratory of Environmental Criteria and Risk Assessment, Chinese Research Academy of Environmental Sciences, Beijing, China

- 5Jiaozhou Bay Marine Ecosystem Research Station, Institute of Oceanology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Qingdao, China

Studies on the formation process and physio-ecological characteristics of primary polyps would help understand the causes of giant jellyfish Nemopilema nomurai blooms in the coastal sea of East Asia. A new mode of settlement and metamorphosis from planulae into primary polyps was observed in this study by artificially breeding N. nomurai polyps in a large tank. N. nomurai planulae could successfully metamorphose into primary polyps with ≤4 tentacles in the seawater, even though they did not initially colonize the hard substrates as previously reported. The developed primary polyps were then able to hang upside down on detritus via the mucus secreted by planulae and float on the seawater surface. Their resettlement on the large, hard substrates showed significant preference to plastic materials (e.g., polyethylene plates); however, the resettlement density was significantly reduced owing to the increase of age. The resettlement of primary polyps was also affected by the combination of salinity and age. The survival of primary polyps increased, but their resettlement percentage significantly decreased at hyposalinity of 10–23 and older age. This study also found that primary polyps on the detritus could normally develop into individuals with 16 tentacles. There was no significant difference in their survival, development of 14–16 tentacles, and calyx growth at salinities of 15–33, indicating their euryhalinity adaptability. This study suggested that floating in the seawater by attaching to detritus was a possible living mode of N. nomurai polyps inhabiting the estuaries’ surroundings, which may favor polyp population recruitment and maintenance.

1 Introduction

The giant jellyfish Nemopilema nomurai Kishinouye, 1922, has been a cause of widespread concern, as its massive blooms in the coastal seas of East Asia have resulted in severe socio-economic and ecological damage in recent decades. Previously, N. nomurai bloomed approximately once every 40 years (in 1920, 1958, and 1995) in the Sea of Japan (Shimomura, 1959; Yasuda, 2004; Uye, 2011), but frequent outbreaks of medusae have occurred since the beginning of 21st century in the northern East China, Yellow, Bohai, Korean, and Japanese seas (Uye, 2014; Yoon et al., 2014; Sun et al., 2015; Dong et al., 2018). Massive aggregations of N. nomurai medusae in the cooling water intakes of some nuclear power plants in China have posed serious threats to the normal operation of nuclear reactors in recent years (Feng et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2023). Stinging cases caused by N. nomurai had obviously increased since 2012 in some touristic cities in China, such as Qingdao, Weihai, and Qin Huangdao, compared to before 2007 (Dong et al., 2010; Niu and Wang, 2014; Wen et al., 2014; Huo et al., 2017). The multitudinous aggregations of N. nomurai medusae also severely disturbed the normal fisheries production by clogging and destroying fishing nets, killing fish, increasing the extra workload of sorting fish, stinging fishermen, etc., which had been reported to cause economic losses of approximately $20 million in Aomori Prefecture, Japan, in 2003 (Kawahara et al., 2006). The frequent outbreaks of N. nomurai have been considered to probably cause a shift from a traditional fish-dominated ecosystem to a jellyfish-dominated ecosystem (Uye, 2011).

The large-scale outbreaks of N. nomurai were widely believed to be associated with the integrated effects of climate change and human activities in the coastal seas (e.g., eutrophication, increased artificial structures, and overfishing) (Uye, 2008, 2014; Purcell, 2012). However, there has always been a lack of conclusive evidence, as reported by Pitt et al. (2018). More investigations are needed to understand the causes of N. nomurai blooms in the coastal seas of East Asia. In the life cycle of N. nomurai, benthic polyps are the key links to the cause of outbreaks of medusae, as polyps release ephyrae by strobilation, which further develop into medusae, and they can also asexually reproduce by podocysts to maintain a sustainable development of polyp colonies (Kawahara et al., 2006; Feng et al., 2018). Thus, studies on the eco-physiologies of N. nomurai polyps are very meaningful to reveal the mechanisms of N. nomurai blooms.

Previous studies on N. nomurai polyps were mainly concerned with the effects of some environmental factors (e.g., temperature, salinity, and food supply) on the growth and asexual reproduction of their fully developed stage with 16 tentacles (Feng et al., 2015; Sun et al., 2015). However, the process of the formation of primary polyps that metamorphosed from planulae and their subsequent development under the stress of different environmental factors have rarely been considered. Although there have been some studies on the influence of salinity (Feng et al., 2018; Takao and Uye, 2018), most of these experiments mainly selected the polyps settling on the large, hard plates or substrates as the investigated objects (Feng et al., 2018, 2020). Few studies have involved other potential settlement modes of polyps. In this study, N. nomurai primary polyps were surprisingly discovered to settle in large quantities on detritus and float on the seawater surface during their artificial breeding (see Results), which was also mentioned in individual studies (Kawahara et al., 2006; Takao and Uye, 2018). It is worth investigating whether these floating primary polyps could resettle on other hard substrates and whether they are able to develop normally, to provide new ideas for exploring the potential survival strategies of N. nomurai polyps in the natural environment, as they have not been discovered in the field so far. Previous studies speculated that some areas around estuaries (e.g., Changjiang Estuary) were the major habitat of N. nomurai polyps (Kawahara et al., 2006; Toyokawa et al., 2012; Uye, 2014; Sun et al., 2015; Dong et al., 2018), and the formation of N. nomurai primary polyps by sexual reproduction occurred in the rainy late summer and autumn in the coastal sea of China (Feng et al., 2015, 2020). We, therefore, mainly investigated the effects of salinity on the resettlement and subsequent growth of these primary polyps on the floating detritus.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Acquisition of planulae and primary polyps

Six female and four male medusae of N. nomurai with mature gonads were captured in the coastal sea of Qingdao, China, on 11 October 2016. They were then immediately transported to a nearby aquaculture farm and introduced into a concrete tank (6 m × 5 m × 1.5 m) containing 30 m3 of filtered seawater through a 0.5-mm mesh. They were kept in the tank for 2 days until abundant fertilized eggs were spawned at the bottom, during which the seawater in the tank was replaced with freshly filtered seawater twice a day. The seawater temperature and salinity were 20 °C ± 0.5 °C and 30.5 ± 0.5, respectively. Then, all medusae were removed from the tank, and seawater renewal was terminated. Nine strings of polyethylene plates, each consisting of 10 pieces (40 × 30 × 0.5 mm), were subsequently placed evenly into the tank. Each string was positioned approximately 20 cm away from the surface and bottom layers of the seawater. The process of metamorphosis from planulae into primary polyps was subsequently observed in the tank. The number of developing planulae and primary polyps was continuously monitored at the surface of the tank on eight different occasions (i.e., 12, 24, 36, 48, 60, 96, 120, and 144 h) after the formation of the fertilized eggs (13 October 2016) by collecting 1 L of seawater and then observing under a dissecting microscope (ZEISS Discovery V20, Oberkochen, Baden-Wurttemberg, Germany). Three samples were collected for each monitoring session. On 18 October 2016, massive primary polyps with ≤4 tentacles were found hanging upside down on the detritus (i.e., some particles containing dust, impurities, and fragments; Figure 1l) and floating on the surface of the seawater (see Results) in addition to attaching to polyethylene plates.

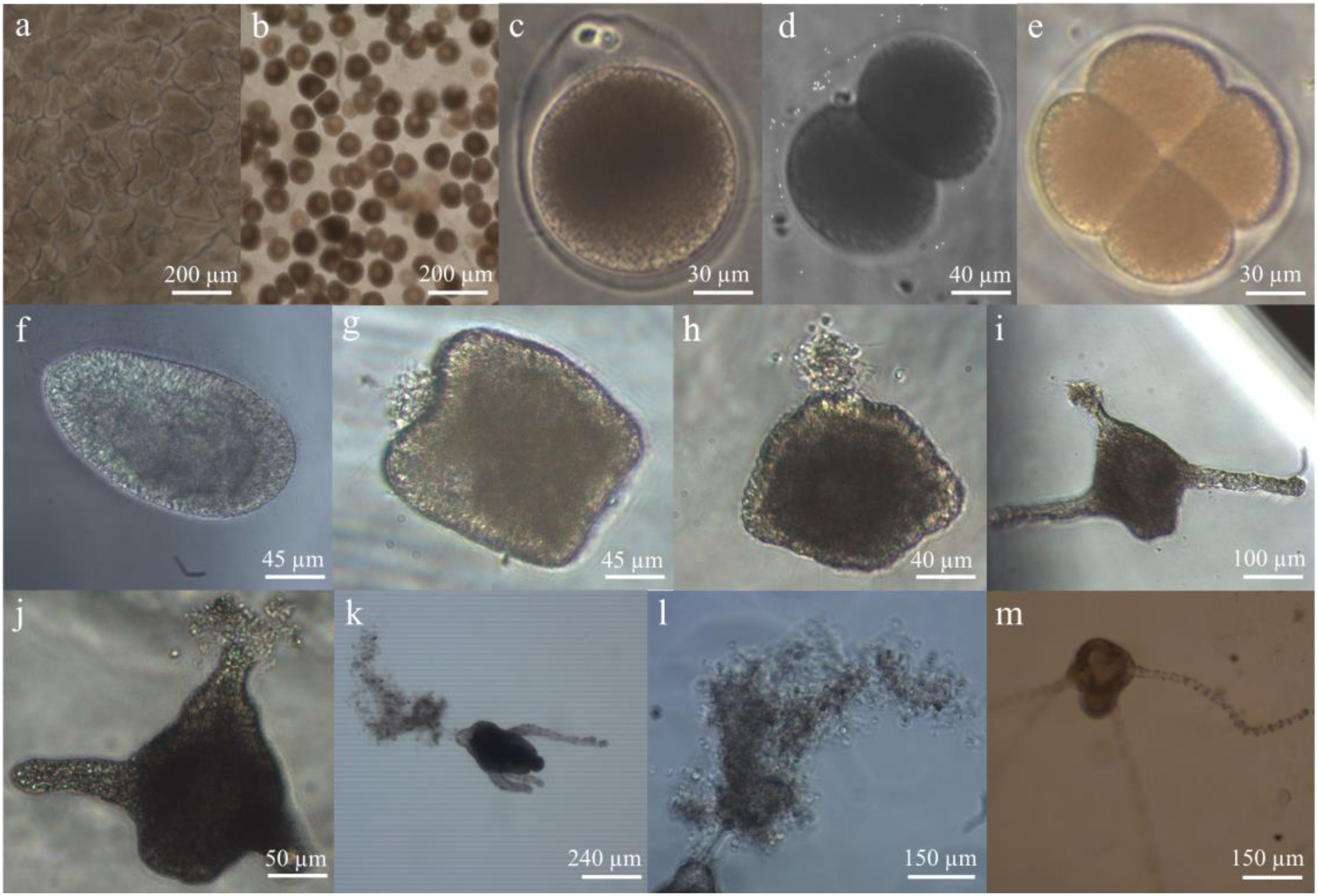

Figure 1. Developmental stages of Nemopilema nomurai observed in the tank. (a) The sperm follicles in the testis. (b) Oocytes in the ovary. (c) Fertilized egg with polar bodies. (d) Two-cell stage development of the fertilized egg. (e) Four-cell stage development of the fertilized egg. (f) Planula of N. nomurai. (g) The metamorphosing planula, whose anterior end was sagging, and mucus was secreted by the mucous cells. (h) The metamorphosing planula, whose posterior end bulged to form the primary mouth of polyps. (i) The two-tentacle primary polyps settling on the polyethylene plate. (j) The two-tentacle primary polyps floating in the seawater. (k) The four-tentacle primary polyps settling on the detritus and floating in the seawater. (l) The floating detritus stuck to the mucus of primary polyps. (m) The four-tentacle primary polyps settling on the polyethylene plate.

2.2 Resettlement of floating primary polyps to hard substrates

In order to clarify whether N. nomurai primary polyps on the floating detritus could resettle on other larger hard substrates, five types of hard substrates (i.e., transparent polyethylene plates, green fishing net, gray iron plate, gray concrete plate, and wood board) were selected in this experiment. The basic characteristics of these substrates are described by Feng et al. (2017a). Each substrate contained three replicates with a size of 10 cm × 10 cm. They were randomly placed on the seawater surface of the tank on the second day (on 20 October 2016), the 13th day (on 31 October 2016), and the 22nd day (on 9 November 2016) following the appearance of large quantities of primary polyps on the floating detritus (on 18 October 2016). The number of resettled polyps on each hard substrate was separately counted after 10 days using a dissecting microscope.

Nine salinities (10, 15, 18, 20, 23, 25, 28, 30, and 33) were designed to study their effects on the resettlement of floating primary polyps to the hard substrates in the experiment. Primary polyps growing on the floating detritus were collected on the 2nd and 22nd days after they appeared in large quantities by scooping the surface seawater of the tank with a 5-L plastic measuring cup on 20 October and 9 November 2016, respectively. For each age, they were then transferred and placed into each of nine plastic containers filled with 20-L filtered seawater with a salinity of 30.5. The seawater in each container was then gradually diluted with deionized water, or coarse salt was added at a rate of 1 salinity change every 1 h to achieve the desired salinities. The salinities were measured using a portable water quality analyzer (HI98195; HANNA, Padova, Italy). Afterward, more than 80 floating individuals were first picked out from each container using a plastic pipette and then were placed at the bottom of a plastic dish (diameter, 11 cm; height, 6 cm) filled with 200 mL of 0.45-μm filtered seawater with the same salinity in each replicate. At 3-day intervals, one-third of the seawater in each dish was first sucked out gently using a plastic pipette, and then the freshly prepared filtered seawater of the same salinity and volume was introduced. The removed seawater was inspected to ensure that no polyps were sucked away. Each treatment consisted of three replicates. The number of polyps surviving and resettling was counted after 10 days under a dissecting microscope.

2.3 Laboratory experiments on growth and development of primary polyps on detritus

The growth and development of primary polyps on detritus were investigated at six salinities (10, 15, 20, 23, 28, and 33). The 12-well culture plates were prepared with some similar detritus added to the bottom of each well at a height of approximately 2–4 mm. Ten primary polyps with an age of 22 days (calyx diameter, 277.1 ± 41.3 μm) settled on the detritus in the above-mentioned 20-L plastic container were randomly transferred to a 12-well culture plate using a plastic pipette on 9 November 2016. Each primary polyp was cultured in the detritus of each well, filled with 10 mL of 0.45-µm filtered seawater of the same salinity. All the culture plates were placed in an incubator at 20°C ± 0.5°C in the dark. Each salinity treatment included three replicates (i.e., three culture plates).

During the experiment, 10 rotifers Brachionus plicatilis (body length, 191.0 ± 17.0 μm) were added to each well of the culture plates to feed polyps once every 3 days (carbon density, 0.8 mg C·L−1). After approximately 2 h, the seawater was replaced with freshly prepared 0.45-µm filtered seawater of the same salinity using a plastic pipette. Polyp monitoring was performed once a week, when the polyp and detritus in each well were first transferred onto a plastic disc (diameter, 5 cm; height, 1 cm) using a plastic pipette and then examined under a dissecting microscope. The number of surviving polyps and the tentacles per polyp were counted. The diameter of the polyp calyx (mouth disc) was measured using an eyepiece micrometer scale. The experiment lasted for 60 days.

2.4 Calculations and statistics

The density of pre-metamorphosing and metamorphosing planulae and that of primary polyps at the seawater surface of the tank were calculated to reflect the process of planula metamorphosis into primary polyps. Their significant differences among various times were examined by one-way ANOVA. The resettlement ability of primary polyps among different hard substrates was represented by their resettled density. This parameter was also characterized by the percentages of polyp survival and resettlement among salinities. Two-way ANOVA was used to test the significant differences in the above-mentioned parameters among ages and substrates or salinities. Three parameters (including the percentage of polyp survival; the percentage of polyps with 4–8, 10–12, and 14–16 tentacles; and the growth of calyx) were determined to represent the growth and development of primary polyps among different salinities. The growth of the calyx was calculated by dividing the diameter of the polyp calyx at each observation by the initial calyx diameter. The significant difference in these parameters among salinities was tested using repeated-measures ANOVA. In all parameters, percentages were transformed by arcsine square root before statistical analysis. When using one-way and two-way ANOVA, data that failed to agree with the assumptions of normality or homogeneity of variance after transformation were analyzed using non-parametric analogues (Kruskal–Wallis one-way ANOVA on ranks). The Greenhouse–Geisser correction was applied when the data violated the assumption of sphericity in repeated-measures ANOVA. For each parameter, pair-wise comparisons were carried out using Tukey’s Honestly Significant Difference (HSD) if the overall ANOVA results were significant.

3 Results

3.1 Observation of the metamorphosis from planulae into primary polyps

Twenty-four hours after adding captured female and male medusae of N. nomurai with mature gonads (Figures 1a, b) into the culture tank, the fertilized eggs were first observed at the bottom of the tank (Figure 1c). They developed into planulae by cell division after 8 h (Figures 1d–f). The length and width of N. nomurai planulae ranged from 120 to 220 µm and 60 to 100 µm, respectively. The planulae not only rotated by themselves but also rose in a spiral to search for the attachment site by ciliary beating. During the process, the metamorphosis of the planulae synchronously occurred. The anterior (aboral) end of moving planulae gradually sagged, when some mucus was secreted by the mucous cells derived from ectodermal differentiation, and their posterior end bulged to form the primary mouth of polyps after 36 h of planula formation (Figures 1g, h). When the planulae encountered the hard substrates, the anterior end of the planulae stuck to their surfaces. However, those planulae that did not find the appropriate substrates continued to move. During that period, the metamorphosis from planulae into primary polyps, including the formation of four tentacles and a mouth, was ongoing (Figures 1i, j). After 6 days, primary polyps (≤4 tentacles) with a density of 77.6 ± 62.2 ind·L−1 were finally discovered to hang upside down on the floating detritus of the seawater surface in the tank (Figures 1k, l), except when settling on the polyethylene plates with a density of 0.4 ± 0.2 ind·cm−2 (Figure 1m).

The density of pre-metamorphosing and metamorphosing planulae and that of primary polyps with ≤4 tentacles significantly differed among various times at the seawater surface of the tank (Table 1). The density of pre-metamorphosing planulae gradually increased to the maximum (i.e., 405.5 ± 239.0 ind·L−1) at 36 h after the formation of the fertilized eggs and then sharply decreased (Figure 2). After 120 h, there were no pre-metamorphosing planulae observed in this study. The metamorphosing planulae were found to only appear at 48–60 h after the formation of the fertilized eggs, the maximum density of which was 146.6 ± 130.6 ind·L−1 at 48 h (Figure 2). Primary polyps with ≤4 tentacles settling on the floating detritus were discovered in large quantities at the seawater surface of the tank after 60 h of the formation of the fertilized eggs. Their density had no significant difference from 60 to 144 h. The maximum was 143.0 ± 74.9 ind·L−1 at 60 h (Figure 2).

Table 1. Summary of one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) results testing the difference in the density of planulae and primary polyps with ≤4 tentacles among various times in the tank; two-way ANOVA results examining the difference in resettlement density of floating primary polyps among substrates and ages, and survival and resettlement percentage among salinities and ages; and repeated-measures ANOVA results reflecting the difference in percentage of survival and tentacle development, and growth of calyx.

Figure 2. Changes in the densities of pre-metamorphosing and metamorphosing planulae, and primary polyps with ≤4 tentacles at the seawater surface of the tank in 144 h for Nemopilema nomurai. Error bars represent standard deviation (n = 3).

3.2 Effect of substrate and salinity on the resettlement of floating primary polyps

The resettlement density of floating primary polyps significantly differed among the substrates and developmental ages (Table 1). A maximum of 3.72 ± 2.19 ind·cm−2 occurred on the polyethylene plates at the 2-day age (Figure 3). The primary polyps showed a significantly higher resettlement density on the surfaces of plastic material (e.g., polyethylene plates) than on wood, iron, and concrete materials. The resettlement density of primary polyps decreased significantly with increasing age (Figure 3), but did not differ remarkably between the ages of 13 and 22 days.

Figure 3. Resettlement density of Nemopilema nomurai floating primary polyps at three ages (2, 13, and 22 days) and five substrates (PP, transparent polyethylene plate; FN, green fishing net; WB, wood board; IP, gray iron plate; CP, gray concrete plate). Error bars represent standard deviation (n = 3).

When the floating primary polyps at a salinity of 30.5 were gradually adapted to various desired salinities, they did not show obvious morphological stress responses, such as body shrinkage at higher salinities or tentacle elongation at low salinities. The survival and resettlement percentage of primary polyps exhibited significant differences among salinities and between both development ages by the end of the experiment (Table 1). The highest survival percentage was 96.0% ± 2.4% at a salinity of 23 and the age of 22 days (Figure 4a). The primary polyps showed the lowest survival percentage (20.0% ± 11.0%) at a salinity of 30 and the age of 2 days. There was a significantly higher survival percentage at low salinity of 10–28 than at high salinity of 30–33 for the primary polyps at the age of 2 days. However, there was no significant difference in the survival percentage at a salinity of 15–33 for the primary polyps at the age of 22 days. In terms of the resettlement percentage of primary polyps, their maximum reached 95.5% ± 6.4% at a salinity of 30 and the age of 2 days (Figure 4b). Only 2.8% ± 1.0% of primary polyps successfully resettled on the surface of 12-well plates at a salinity of 15 and the age of 22 days. The resettlement percentage showed no significant difference at a salinity of 15–33 for the primary polyps with the age of 2 days; however, the percentage was significantly higher at high salinities of 28–33 than at other salinities for those polyps with the age of 22 days. In general, with the increase in age of primary polyps, the survival percentage of polyps significantly increased; however, their resettlement ability significantly decreased. Under the conditions of hyposalinity of 10–23, the primary polyps showed high survival but significantly low resettlement percentage.

Figure 4. Survival (a) and resettlement percentage (b) of Nemopilema nomurai primary polyps at two ages (2 and 22 days) and nine salinities (10, 15, 18, 20, 23, 25, 28, 30, and 33). Error bars represent standard deviation (n = 3).

3.3 Growth and development of primary polyps on the detritus at different salinities

During the experiment, the primary polyps on the detritus were found to be capable of unceasingly growing and developing. The survival percentage of polyps exhibited a gradual decline over time in all the groups (Figure 5a), with significant differences among salinities (Table 1). At a salinity of 10, the decrease in survival percentage of polyps was more rapid after 0.5 months compared to other salinities (Figure 5a). By the end of the experiment, the survival percentage of polyps was only 33.3% ± 16.7% at a salinity of 10, which was significantly the lowest among all the treatments. In contrast, the eventual survival percentage of polyps did not significantly differ among other salinities, and the maximum was 71.9% ± 10.6% at a salinity of 23.

Figure 5. Survival percentage (a), percentage of tentacle development (b), and growth of calyx (c) of Nemopilema nomurai primary polyps with the age of 22 days at six salinities (10, 15, 20, 23, 28, and 33). Error bars represent standard deviation (n = 3).

The number of polyp tentacles gradually increased over time during the experiment. In 1 month, 41.4%–77.6% of polyps had fully developed 14–16 tentacles (Figure 5b). However, the percentages of 4–8 and 14–16 tentacles did not show a significant difference among salinities during polyp development (Table 1). By the end of the experiment, the percentage of fully developed polyps fluctuated from 66.7% to 94.4% (Figure 5b). The growth of the polyp calyx significantly differed among salinities (Table 1). Throughout the experimental period, the diameter of the polyp calyx exhibited a consistent increase at a salinity of 15–33, among which the maximum increase rate appeared at a salinity of 33 (Figure 5c). However, the change in the first increase and then the slight decrease after 1 month in the diameter of the polyp calyx was discovered at a salinity of 10. By the end of the experiment, the diameter of the polyp calyx was a maximum of 645.5 ± 30.1 µm at a salinity of 33 and a minimum value of 455.2 ± 51.1 µm at a salinity of 10.

4 Discussion

4.1 New insight into metamorphosis from N. nomurai planulae into primary polyps

In this experiment, N. nomurai planulae could develop in 8 h at the earliest after the eggs produced by the mature females were fertilized at the bottom of the tank. The time of planula formation was much shorter than that (approximately 24 h) reported by Kawahara et al. (2006). However, the size of the planulae was similar in both studies. It was observed that the planulae not only rotated by themselves but also swam in a spiral in the experimental tank. This geo-negative behavior was consistent with the reports of Takao and Uye (2018). Previous laboratory experiments demonstrated that scyphozoan planulae such as Aurelia spp., Cyanea spp., and N. nomurai usually began to metamorphose into polyps after completing settlement (Brewer, 1976; Holst and Jarms, 2007; Conley and Uye, 2015; Takao and Uye, 2018). However, our study found that N. nomurai planulae were able to metamorphose while swimming in the tank. The anterior end of N. nomurai planulae was gradually sunken to develop the base of primary polyps, where some mucus was secreted by the mucous cells derived from ectodermal differentiation for settlement as in Hydra (Bonner, 1955; Sommer, 1990; Müller and Leitz, 2002; El-Bawab, 2020). When the planulae encountered the polyethylene plates in the tank, the anterior ends of the planulae settled by sticking to their surfaces and then gradually developed into polyps. However, those planulae that did not encounter the plates continued to swim, and the mouth and tentacles of primary polyps gradually developed at the posterior end of the planulae. Compared to previous studies (Brewer, 1976; Holst and Jarms, 2007; Conley and Uye, 2015; Takao and Uye, 2018), this observed metamorphosis difference may be related to the experimental water volume used. In previous studies, scyphozoan planulae were usually cultured in well plates or small beakers, where it was easier for them to quickly discover the suitable settlement sites before metamorphosis. Thus, it was previously observed that planulae usually metamorphosed into polyps after finishing settlement. In this experiment, however, a tank filled with 30-m3 seawater was used to study the metamorphosis process of planulae. In such a large volume of seawater, N. nomurai planulae may spend more time finding the attachment sites. They thus had to synchronously develop into primary polyps before attachment. Since N. nomurai planulae moved in a spiral upward in the tank, this study found that massive individuals could finally hang upside down on the floating detritus of the seawater surfaces. This new insight into the metamorphosis of N. nomurai planulae may be more consistent with their in situ attachment behavior in the natural environment, owing to the large experimental seawater volume and the increased difficulty in seeking appropriate attachment sites for planulae. Settlement and metamorphosis on the water surface were also reported in previous studies for some scyphozoan planulae, including Aurelia spp. and N. nomurai (Korn, 1966; Kroiher and Berking, 1999; Kawahara et al., 2006; Holst and Jarms, 2007; Schiariti et al., 2024). However, this study further confirmed that they could float at the water–air interface by settling on the detritus of the seawater surface using the mucus.

4.2 Effect of abiotic factors on the resettlement and subsequent growth of floating primary polyps

Scyphozoan polyps such as Aurelia spp. and Cyanea spp. have been generally believed to settle on the surfaces of fixed hard substrates in the natural environment, in particular on some floating docks, piers, and artificial reefs, as well as the surfaces of some macro-fouling organisms (e.g., ascidians, bryozoans, oysters, and mussels) inhabiting these large substrates (Miyake et al., 2002; Makabe et al., 2014; Dong et al., 2018; Yoon et al., 2018; Feng et al., 2022). However, this study found that primary polyps of N. nomurai were also able to float by settling on the detritus of the seawater surfaces when planulae did not encounter large, suitable hard substrates. Then, when coming across proper substrates, they could resettle by directly sticking to their surfaces using the mucus. This settlement mode could provide a buffer period for the establishment of polyp population in the natural environment, which is meaningful since it may be difficult for many planulae to search for those large substrates within a short time in the huge sea. The resettlement density of N. nomurai primary polyps floating on the detritus was found to have a significant difference among various substrates and developmental ages in this study. The floating primary polyps showed a preference for plastic materials compared to other types of substrates (e.g., concrete, wood, and iron) during the resettlement, which was similar to the preference of some other scyphozoan planulae (e.g., Cyanea lamarckii and Aurelia spp.; Holst and Jarms, 2007; Hoover and Purcell, 2009). It was implied that submarine artificial substrates could also provide suitable habitats for the resettlement of N. nomurai floating primary polyps, except for the settlement of planulae (Kawahara et al., 2006; Uye, 2011).

However, with the increase in the development age of N. nomurai primary polyps, their resettlement density significantly decreased on the substrates in this study. On the one hand, this may be associated with the active time of the mucus, which was secreted by the mucous cells in the anterior end of planulae. The stickiness function of the mucus may be gradually deactivated over time due to the degradation of some relative substances (e.g., polysaccharides and glycoproteins), as previously studied in Hydra (Bonner, 1955). On the other hand, it was also seen that new mucus may be slowly and rarely secreted by the stem base of primary polyps in subsequent development, based on previous reports (Kepner and Thomas, 1928; Turk et al., 2021). Thus, the resettlement ability of N. nomurai polyps constantly reduced with age in this study.

Salinity was also found to have an important effect on the resettlement of N. nomurai primary polyps floating on the detritus. A higher survival percentage was observed under the condition of low salinity for the 2-day-old primary polyps, which was consistent with the studies of Feng et al. (2018, 2020). However, as the age of primary polyps increased, they could adapt to a wider range of salinity (15–33) with enhanced survival ability. It was easy to understand that as N. nomurai polyps gradually grew and developed into individuals with 16 tentacles, they became more resilient to environmental stress, just like those polyps attached to the polyethylene plates as previously reported (Dong et al., 2015; Feng et al., 2015, 2018, 2020). By contrast, the resettlement ability of N. nomurai floating primary polyps exhibited various responses to exposure to salinity in comparison with survival. Except at a salinity of 10, their resettlement percentage did not significantly differ among other salinities for the 2-day-old primary polyps, indicating that they could widely resettle in the natural environment. This euryhalinity characteristic was similar to that during the settlement of N. nomurai planulae as previously reported (Takao and Uye, 2018). However, with the increase in the age of primary polyps, the resettlement percentage sharply decreased at low salinity, which suggested that hyposalinity would be unfavorable to their resettlement in the process of subsequent development. It was speculated that this case may be attributed to the changes in individual physiology resulting from the decrease in body fluid osmolarity in a hyposaline environment. Deterministic reasons require further exploration, although similarly undesirable responses to low salinities had also been observed in many scyphozoan planulae, such as reduced planula swimming speed (Holst and Jarms, 2010; Conley and Uye, 2015; Takao and Uye, 2018).

This study also found that N. nomurai primary polyps were capable of developing into individuals with 16 tentacles even if they had been attached to the detritus. Although their survival percentage slowly declined with time, the difference among salinities was not significant except at an extreme hyposalinity of 10, where this reduced survival percentage was probably due to the swelling of some polyp bodies having reached a lethal level as some scyphozoan planulae (Holst and Jarms, 2010; Conley and Uye, 2015; Takao and Uye, 2018). The percentage of 14–16 tentacles did not significantly differ among salinities during the entire process of the experiment, suggesting that the tentacle development of primary polyps was less affected by salinity in general. However, the growth of the polyp calyx significantly decreased at hyposalinity of 10, which may also result from the drastic changes in the osmotic stress of polyp bodies as described above. In summary, even inhabiting the detritus, N. nomurai primary polyps with older age could still exhibit euryhalinity adaptability during subsequent growth and development, similar to those polyps settling on hard substrate surfaces (Feng et al., 2018, 2020).

4.3 Possible additional pattern of N. nomurai polyps inhabiting the field

N. nomurai is a distinctive regional blooming scyphozoan species because it is only distributed and massively blooms in the coastal seas of East Asia (Uye, 2011; Yoon et al., 2014; Sun et al., 2015; Dong et al., 2018; Kitajima et al., 2020). Many studies have speculated that some areas around estuaries, such as the Changjiang River estuary and the northern Liaodong Bay estuaries, may be important breeding places of N. nomurai by surveys on ephyrae and juvenile medusae (Toyokawa et al., 2012; Yoon et al., 2014; Sun et al., 2015; Dong et al., 2018) and laboratory simulation experiments on polyps (Feng et al., 2018, 2020). However, polyps of N. nomurai have not been discovered in the natural environment until now, unlike some other scyphozoan polyps such as Aurelia spp., which primarily inhabit the undersurfaces of artificial substrates in nearshore areas (Ishii and Katsukoshi, 2010; Makabe et al., 2014; Yoon et al., 2018; Feng et al., 2022), and Chrysaora spp., which were found to settle inside dead bivalve shells and small stones resting on the shallow bottom (Toyokawa, 2011; van Walraven et al., 2020). This was very confusing, and it was necessary to consider whether N. nomurai polyps had other unique inhabiting modes in the field. This study suggested a possible living mode of N. nomurai polyps located around estuaries; namely, polyps survived by settling on the floating detritus, which may have two advantages at least compared to settlement on the large fixed substrates.

On the one hand, the probability of successful attachment of N. nomurai planulae may be increased. With the difference from the habitats of Aurelia spp. polyps, usually located on some areas with low sea currents inshore semi-/enclosed ports and bays so that planulae could easily settle on the undersurfaces of many artificial substrates (Miyake et al., 2002; Yoon et al., 2018; Feng et al., 2022), the regions around the estuaries where N. nomurai polyps live often showed strong mixture of seawater and freshwater, particularly in the rainy summer and autumn when planulae of N. nomurai were produced in large quantities by sexual reproduction of medusae (Feng et al., 2015, 2018; Sun et al., 2015). In this case, not only the areas with stable and low water flow but also hard substrates for polyps on the soft sediments were scarce. It thus would be difficult for N. nomurai planulae to search for suitable hard substrates like those of Aurelia spp. However, there had indeed been a multitude of detritus in the turbid seawater around the estuaries because of the terrigenous input and violent, vertical, mixed disturbance of seawater as previously reported by Lucas et al. (2025). When N. nomurai planulae were produced in large quantities around the estuaries and swam up in a spiral motion to search for the attachment sites, the detritus in the seawater could exactly provide a good medium for their successful settlement and metamorphosis, and subsequent development of polyps based on this study.

On the other hand, the biofouling invasion against N. nomurai polyps would be weakened. Settling on the detritus in the seawater allowed N. nomurai primary polyps to be capable of drifting along with the current. Their high survival and low resettlement percentages at hyposalinity in this study indicated that the behavior of polyps floating and sinking repeatedly would become easier in hyposaline areas around estuaries. In this way, the invasion of fouling organisms into N. nomurai polyps is avoided in comparison to the adhesion mode on large, hard substrate surfaces, where N. nomurai polyps hardly survived for a long time, and they were usually completely eliminated by the invasion of many macro-fouling organisms (e.g., ascidian and bryozoan) on the substrates due to weak interspecific competitiveness (Feng et al., 2017b, 2018, 2022). Although some safe refuges with few or no biofouling, such as inside dead bivalve shells, had been suggested as the possible substrates that N. nomurai polyps inhabited, such as Chrysaora spp. previously reported (Toyokawa, 2011; Feng et al., 2018; van Walraven et al., 2020), the settlement on the detritus in the seawater around estuaries may also create biofouling-free conditions for N. nomurai polyps, which thus may be crucial to their population recruitment and maintenance.

Broadly speaking, this study further confirmed that N. nomurai polyps may widely distribute around estuaries; in particular, their habitats could be extended into brackish water. In addition to inhabiting the relatively large, hard substrates previously considered, floating in the seawater by attaching to the detritus around estuaries was also speculated to be a possible living mode of N. nomurai polyps, owing to the successful attachment and metamorphosis of planulae as well as the normal growth and development of subsequent primary polyps. Moreover, the primary polyps on detritus were still able to reattach to the large substrate surfaces under suitable conditions and opportunities. These survival strategies may be beneficial to the long-term maintenance of the polyp population around estuaries, although more in situ studies are needed to verify this in the future for a clear understanding of the mechanisms of N. nomurai blooms.

5 Conclusion

This study found that N. nomurai planulae could normally metamorphose into primary polyps with ≤4 tentacles, even if they did not initially colonize the hard substrates during the artificial breeding of polyps. Primary polyps could settle on the detritus using the mucus secreted by planulae and float on the surface of seawater. They could resettle on the large, hard substrate with a preference for plastic materials. The resettlement of floating primary polyps was also restricted by the combination of salinity and age. Their survival percentage was able to increase, but the resettlement percentage decreased at hyposalinity. With the increase in age, their survival was enhanced, but their resettlement ability decreased. Primary polyps on the detritus could also normally grow and develop into individuals with 16 tentacles. Their survival, development of 14–16 tentacles, and calyx growth did not significantly differ at a salinity of 15–33, suggesting that they had euryhalinity adaptability. This study highlighted a possible living mode of N. nomurai polyps located around estuaries; namely, polyps survived by settling on the detritus and floating in the seawater, which was presumed to benefit their population recruitment and maintenance.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The manuscript presents research on animals that do not require ethical approval for their study.

Author contributions

SF: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. XX: Formal Analysis, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. SM: Data curation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. YX: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. JL: Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. XW: Writing – review & editing. XJ: Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. SS: Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This research was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (grant no. 2023YFC3108204), National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 42176136 and 42130411), “Future Partner Network” Project of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (grant no. 058GJHZ2022097FN), Youth Innovation Promotion Association Project, Chinese Academy of Sciences and Huiquan Scholar, and Institute of Oceanology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, to Song Feng.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to fisherman Guangshui Yu for his help with the breeding of N. nomurai polyps.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Bonner J. T. (1955). A note concerning the distribution of polysaccharides in the early development of the hydromedusan Phialidium gregarium. Biol. Bull. 108, 18–20. doi: 10.2307/1538391

Brewer R. H. (1976). Larval settling behavior in Cyanea capillata (Cnidaria: Scyphozoa). Biol. Bull. 150, 183–199. doi: 10.2307/1540467

Conley K. and Uye S.-I. (2015). Effects of hyposalinity on survival and settlement of moon jellyfish (Aurelia aurita) planulae. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 462, 14–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jembe.2014.10.018

Dong Z., Liu D., and Keesing J. K. (2010). Jellyfish blooms in China: dominant species, causes and consequences. Mar. pollut. Bull. 60, 954–963. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2010.04.022

Dong J., Sun M., Purcell J. E., Chai Y., Zhao Y., and Wang A. (2015). Effect of salinity and light intensity on somatic growth and podocyst production in polyps of the giant jellyfish Nemopilema nomurai (Scyphozoa: Rhizostomeae). Hydrobiologia 754, 75–83. doi: 10.1007/s10750-014-2087-y

Dong J., Wang B., Duan Y., Yoon W. D., Wang A., Liu X., et al. (2018). Initial occurrence, ontogenic distribution-shifts and advection of Nemopilema nomurai (Scyphozoa: Rhizostomeae) in Liaodong Bay, China, from 2005-2015. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 591, 185–197. doi: 10.3354/meps12272

Dong Z., Wang L., Sun T., Liu Q., and Sun Y. (2018). Artificial reefs for sea cucumber aquaculture confirmed as settlement substrates of the moon jellyfish Aurelia coerulea. Hydrobiologia 818, 223–234. doi: 10.1007/s10750-018-3615-y

Feng S., Lin J., Sun S., and Zhang F. (2017a). Artificial substrates preference for proliferation and immigration in Aurelia aurita (s. l.) polyps. J. Oceanol. Limnol. 35, 153–162. doi: 10.1007/s00343-016-5230-y

Feng S., Lin J., Sun S., Zhang F., and Li C. (2018). Hyposalinity and incremental microzooplankton supply in early-developed Nemopilema nomurai polyp survival, growth, and podocyst reproduction. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 591, 117–128. doi: 10.3354/meps12204

Feng S., Lin J., Sun S., Zhang F., Li C., and Xian W. (2020). Combined effects of seasonal warming and hyposalinity on strobilation of Nemopilema nomurai polyps. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 524, 151316. doi: 10.1016/j.jembe.2020.151316

Feng S., Sun S., Li C., and Zhang F. (2022). Controls of Aurelia coerulea and Nemopilema nomurai (Cnidaria: Scyphozoa) blooms in the coastal sea of China: strategies and measures. Front. Mar. Sci. 9. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2022.946830

Feng S., Wang S. W., Zhang G. T., Sun S., and Zhang F. (2017b). Selective suppression of in situ proliferation of Scyphozoan polyps by biofouling. Mar. pollut. Bull. 114, 1046–1056. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2016.10.062

Feng S., Zhang F., Sun S., Wang S., and Li C. (2015). Effects of duration at low temperature on asexual reproduction in polyps of the scyphozoan Nemopilema nomurai (Scyphozoa: Rhizostomeae). Hydrobiologia 754, 97–111. doi: 10.1007/s10750-015-2173-9

Holst S. and Jarms G. (2007). Substrate choice and settlement preferences of planula larvae of five Scyphozoa (Cnidaria) from German Bight, North Sea. Mar. Biol. 151, 863–871. doi: 10.1007/s00227-006-0530-y

Holst S. and Jarms G. (2010). Effects of low salinity on settlement and strobilation of Scyphozoa (Cnidaria): is the lion’s mane Cyanea capillata (L.) able to reproduce in the brackish Baltic Sea? Hydrobiologia 645, 53–68. doi: 10.1007/s10750-010-0214-y

Hoover R. A. and Purcell J. E. (2009). Substrate preferences of scyphozoan Aurelia labiata polyps among common dock-building materials. Hydrobiologia 616, 259–267. doi: 10.1007/s10750-008-9595-6

Huo S., Tian Y., Zhang Y., Su X., and Liu J. (2017). Epidemiological analysis of jellyfish stings in 2577 cases in Qinhuangdao. J. Hebei Med. Univ. 38, 1141–1157.

Ishii H. and Katsukoshi K. (2010). Seasonal and vertical distribution of Aurelia aurita polyps on a pylon in the innermost part of Tokyo Bay. J. Oceanogr. 66, 329–336. doi: 10.1007/s10872-010-0029-5

Kawahara M., Uye S., Ohtsu K., and Iizumi H. (2006). Unusual population explosion of the giant jellyfish Nemopilema nomurai (Scyphozoa: Rhizostomeae) in East Asian waters. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 307, 161–173. doi: 10.3354/meps307161

Kepner W. A. and Thomas W. L. (1928). Histological features correlated with gas secretion in Hydra Oligactis pallas. Biol. Bull. 54, 529–533. doi: 10.2307/1536808

Kitajima S., Hasegawa T., Nishiuchi K., Kiyomoto Y., Taneda T., and Yamada H. (2020). Temporal fluctuations in abundance and size of the giant jellyfish Nemopilema nomurai medusae in the northern East China Sea 2006-2017. Mar. Biol. 167, 75. doi: 10.1007/s00227-020-03682-1

Korn H. (1966). Zur ontogentischen di verenzierung der coelenteratengewebe (Polypenstadium) unter besonderer Berücksichtigung des nervensystems. Z Morph Ökol Tiere 57, 1–118. doi: 10.1007/BF00578361

Kroiher M. and Berking S. (1999). On natural metamorphosis inducers of the cnidarian Hydractinia eChinata (Hydrozoa) and Aurelia aurita (Scyphozoa). Helgol Mar. Res. 53, 118–121. doi: 10.1007/s101520050014

Lucas C. H., Höhn D. P., and Trueman C. N. (2025). Insights into the feeding of jellyfish polyps in wild and laboratory conditions: do experiments provide realistic estimates of natural functional rates? Hydrobiologia 852, 5249–5259. doi: 10.1007/s10750-024-05783-0

Makabe R., Furukawa R., Takao M., and Uye S. (2014). Marine artificial structures as amplifiers of Aurelia aurita S.L. blooms: a case study of a newly installed floating pier. J. Oceanogr. 70, 447–455. doi: 10.1007/s10872-014-0249-1

Miyake H., Terazaki M., and Kakinuma Y. (2002). On the polyps of the common jellyfish Aurelia aurita in Kagoshima Bay. J. Oceanogr. 58, 451–459. doi: 10.1023/A:1021628314041

Müller W. A. and Leitz T. (2002). Metamorphosis in the Cnidaria. Can. J. Zool. 80, 1755–1771. doi: 10.1139/Z02-130

Niu S. J. and Wang W. L. (2014). Clinical analysis of 1136 stinging cases by Nemopilema nomurai. Clin. Focus 29, 188–189.

Pitt K., Lucas C. H., Condon R. H., Duarte C. M., and Stewart-Koster B. (2018). Claims that anthropogenic stressors facilitate jellyfish blooms have been amplified beyond the available evidence: a systematic review. Front. Mar. Sci. 451. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2018.00451

Purcell J. E. (2012). Jellyfish and ctenophore blooms coincide with human proliferations and environmental perturbations. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 4, 209–235. doi: 10.1146/annurev-marine-120709-142751

Schiariti A., Holst S., Tiseo G. R., Miyake H., and Morandini A. C. (2024). Life cycles and reproduction of Rhizostomeae. Adv. Mar. Biol. 98, 193–254. doi: 10.1016/bs.amb.2024.07.006

Shimomura T. (1959). On the unprecedented flourishing of‘Echizen Kurage’Stomolophus nomurai (Kishinouye), in the Tsushima Current regions in autumn, 1958. Bull. Japan Sea Reg. Fish. Res. Lab. 7, 85–107.

Sommer C. (1990). Post-embryonic larval development and metamorphosis of the hydroid Eudendrium racemosum (Cavolini) (Hydrozoa, Cnidaria). Helgolander Meeresunters 44, 425–444. doi: 10.1007/BF02365478

Sun S., Zhang F., Li C. L., Wang S., Wang M. X., Tao Z. C., et al. (2015). Breeding places, population dynamics, and distribution of the giant jellyfish Nemopilema nomurai (Scyphozoa: Rhizostomeae) in the Yellow Sea and the East China Sea. Hydrobiologia 754, 59–74. doi: 10.1007/s10750-015-2266-5

Takao M. and Uye S. I. (2018). Effects of low salinity on the physiological ecology of planulae and polyps of scyphozoans in the East Asian marginal seas: Potential impacts of monsoon rainfall on medusa population size. Hydrobiologia 815, 165–176. doi: 10.1007/s10750-018-3558-3

Toyokawa M. (2011). First record of wild polyps of Chrysaora pacifica (Goette 1886) (Scyphozoa, Cnidaria). Plankton Benthos Res. 6, 175–177. doi: 10.3800/pbr.6.175

Toyokawa M., Shibata M., Cheng J., Li H., Ling J. Z., Lin N., et al. (2012). First record of wild ephyrae of the giant jellyfish Nemopilema nomurai. Fisheries Sci. 78, 1213–1218. doi: 10.1007/s12562-012-0550-0

Turk V., Fortic A., Kramar M. K., Znidaric M. T., Strus J., Kostanjsek R., et al. (2021). Observations on the surface structure of Aurelia solida (Scyphozoa) polyps and medusae. Diversity-basel 13, 244. doi: 10.3390/d13060244

Uye S. I. (2008). Blooms of the giant jellyfish Nemopilema nomurai: a threat to the fisheries sustainability of the East Asian marginal seas. Plankton Benthos Res. 3, 125–131. doi: 10.3800/pbr.3.125

Uye S. I. (2011). Human forcing of the copepod-fish-jellyfish triangular trophic relationship. Hydrobiologia 666, 71–83. doi: 10.1007/s10750-010-0208-9

Uye S. I. (2014). “The giant jellyfish Nemopilema nomurai in East Asian Marginal Seas,” in Jellyfish blooms. Eds. Pitt K. A. and Lucas C. H. (Springer, Heidelberg), 185–205. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-7015-7

van Walraven L., van Bleijswijk J., and van der Veer H. W. (2020). Here are the polyps: in situ observations of jellyfish polyps and podocysts on bivalve shells. PeerJ 8, e9260. doi: 10.7717/peerj.9260

Wang X. C., Jin Q. Q., Yang L., Jia C., Guan C. J., Wang H. N., et al. (2023). Aggregation process of two disaster-causing jellyfish species, Nemopilema nomurai and Aurelia coerulea, at the intake area of a nuclear power cooling-water system in Eastern Liaodong Bay, China. Front. Mar. Sci. 9, 1098232. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2022.1098232

Wen Z. Y., Liu J. L., Kang X. H., Zhang Q., and Wu Q. (2014). Clinical analysis to 630 stinging cases of children by Nemopilema nomurai. Shandong Med. 54, 53–55.

Yasuda T. (2004). On the unusual occurrence of the giant medusa Nemopilema nomurai in Japanese waters. Bull. Jpn. Soc Sci. Fish 70, 380–386.

Yoon W., Chae J., Koh B.-S., and Han C. (2018). Polyp removal of a bloom forming jellyfish, Aurelia coerulea, in Korean waters and its value evaluation. Ocean Sci. J. 53, 499–507. doi: 10.1007/s12601-018-0015-1

Keywords: primary polyps, Nemopilema nomurai, planulae, detritus, resettlement

Citation: Feng S, Xu X, Mo S, Xu Y, Lin J, Wang X, Jia X and Sun S (2025) Floating primary polyps of Nemopilema nomurai on detritus: effects of abiotic factors on their resettlement and subsequent growth. Front. Ecol. Evol. 13:1675121. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2025.1675121

Received: 27 August 2025; Accepted: 28 November 2025; Revised: 21 November 2025;

Published: 19 December 2025.

Edited by:

André Carrara Morandini, University of São Paulo, BrazilCopyright © 2025 Feng, Xu, Mo, Xu, Lin, Wang, Jia and Sun. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Song Feng, ZmVuZ3NvbmdAcWRpby5hYy5jbg==; Xiaobo Jia, amlheGlhb2JvQGZveG1haWwuY29t; Song Sun, c3Vuc29uZ0BxZGlvLmFjLmNu

Song Feng

Song Feng Xueting Xu1,2

Xueting Xu1,2 Shiyu Mo

Shiyu Mo