- 1Unidad Académica de Sistemas Arrecifales, Instituto de Ciencias del Mar y Limnología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Puerto Morelos, Mexico

- 2Research Department, SECORE International, Miami, FL, United States

Research in the Mexican Caribbean on the use of assisted propagation to produce coral sexual recruits for outplanting onto local coral reefs has resulted in success as measured by the persistence of the recruits despite intensive heat waves and the production of colonies which are reproducing in the wild. This research is based on four cornerstones: 1) accurate prediction of coral spawning dates and times based on an analysis of almost 20 years of data that helps to make for efficient programming of field work to different sites; 2) the optimization of low-cost methods to assist in the sexual reproduction for five reef-building species through to outplanting and monitoring of the recruits in the wild; 3) the cryopreservation of sperm to form a gene bank of six species of reef-building corals for use in the future when environmental conditions improve and 4) knowledge sharing and capacity building of individuals and organizations around the Caribbean to increase the possibilities of success in using these techniques.

1 Introduction

Coral reefs house 25% of the ocean’s biodiversity, while occupying less than 1% of the ocean’s surface (Burke et al., 2011). These ecosystems benefit more than a billion people who depend directly or indirectly on coral reefs for food security, especially of healthy proteins, coastal protection of their homes and hotels, beach formation, and revenue from tourism and fisheries (Moberg and Folke, 1999; MEA, 2005).

Extreme marine heat waves correlated with high sea surface temperatures and climate cycles on a global scale have resulted in mass mortalities of corals and subsequent degradation of coral reefs (Donovan et al., 2021; Hughes et al., 2018). The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Species Survival Commissions’ Coral Specialist Group have been involved in documenting the decline of different species and, unfortunately, the decline of corals is faster than that of other groups (Gutierrez et al., 2024).

A long-term trend in declining coral cover has been documented in the Caribbean (Gardner et al., 2003; Jackson et al., 2014; Cramer et al., 2020). Reefs along the Mexican Caribbean have shown signs of degradation due to a combination of disturbances since the 1980s (Gómez et al., 2022) and are in a crisis that is bordering on a catastrophe. Devastation from hurricanes, coral diseases, and poor water quality due to inadequate sewage treatment plants (Gómez et al., 2022), in combination with the climate change related bleaching event of 2023 (Birkart and Álvarez-Filip, 2025) have resulted in a reduction in coral cover on the local coral reefs. Given the high level of mortality of colonies of many coral species, the remaining healthy colonies are much more widely dispersed and no longer found in groups or species-specific patches.

Restoration is becoming a key component to achieve functional, resilient and self-sustaining ecosystems for future generations (Hein et al., 2021; Banaszak et al., 2023). The loss of reef-building coral species is so extensive, widespread, and fast paced that passive restoration through the protection and conservation of this incredibly diverse and complex ecosystem is no longer enough. We need to actively produce reef-building corals to restore coral reef ecosystems, because these are the foundation species of coral reefs, forming the critical framework of coral reefs. Fewer reproductive colonies further apart, which potentially influences the success of natural fertilization and recruitment of mass spawning coral species. Even when spawning is synchronized, with colonies that are fewer and further apart, the probability that their gametes will coincide with gametes from a colony of the same species is effectively zero.

One approach to restoration is to produce sexual recruits using ex situ-assisted fertilization of wild-caught gametes from reef-building species. Using sexual recombination, we increase genetic diversity, thereby improving the chances of gametes fertilizing and surviving in the face of the multiple threats to which they are exposed. By actively collecting gametes from different colonies, mixing them together and fertilizing them, we greatly increase fertilization success and overcome the first barrier to successful recruitment by corals on coral reefs.

Given the changing conditions of the planet, the creation of genetic banks worldwide is a growing trend, driven by the need to preserve biodiversity and conserve endangered species (Kumaraswamy and Udayakumar, 2011; Hagedorn et al., 2017), which can serve as an alternative plan in case restoration efforts are not sufficiently effective.

In the Mexican Caribbean, research on assisted sexual reproduction as a tool has become a fundamental component in reef restoration efforts. Here we present what we consider to be the four cornerstones of a successful restoration program that have been developed and used in the Mexican Caribbean: 1) prediction of coral spawning dates and times based on an analysis of almost 20 years of data: 2) optimization of methods in assisted sexual reproduction for five reef-building species; 3) cryopreservation of sperm and vitrification of larvae and 4) knowledge sharing and capacity building. By sharing our approach, our hope is that it will motivate and encourage others to implement sexual coral reproduction as part of their restoration programs. In addition, we strongly believe that restoration efforts should always be science-based and include short, medium and long-term strategies to address the loss of coral cover and be adaptable and modifiable depending on the results obtained.

2 Four cornerstones to conserve and restore corals in the Mexican Caribbean

2.1 Prediction of coral spawning dates and times

One of the cornerstones for reef restoration is via assisted coral sexual reproduction, which requires the accurate prediction of coral spawning dates and times. Coral spawning of most Caribbean reef-building species generally takes place in the summer months. In the Mexican Caribbean, spawning takes place from July to September and rarely in October. Accurate predictions are crucial to efficiently allocate human and financial resources, particularly in developing countries where financial resources are limited. Yearly, prior to the summer, we analyze the information held in the Mexican Caribbean Coral Spawning Data Base to prepare spawning prediction calendars for the major Caribbean reef-building species (e.g. Banaszak et al., 2025). The Data Base contains 889 records collected between 2007 and 2024 of 13 hermatypic species (Table 1) from 29 sites distributed along 400 km of coast, located in Cancun, Puerto Morelos, Playa del Carmen, Cozumel, Akumal, and Punta Allen (Figure 1). Spawning dates are predicted relative to the number of days after the full moon in July, August and September and varies among species (Table 2). The probability of a spawning event shown in Table 2 is calculated by determining the number of spawning events relative to the night of the full moon using the time frames indicated in Table 2 for the different species. A larger number of observed spawning events on a given night after full moon results in a higher probability of spawning (and therefore a darker color in the Table).

Figure 1. Location of the 29 monitored sites from the Mexican Caribbean Coral Spawning Data Base. Close up of all sites are shown in panels (A-D) except for Pajaritos-Punta Allen (southern light blue circle in the general map at the top left).

Table 2. Total spawning events registered in the Mexican Caribbean at 29 monitored sites for five reef-building species: A palmata (2007 – 2024, blue), D. labyrinthiformis (2007 – 2023, green), O. faveolata (2019 – 2024, magenta), O. annularis (2018 – 2024, pink) and P. strigosa (2009, 2014, 2017, 2018, 2020 – 2024, light orange).

Using the Mexican Caribbean Coral Spawning Data Base records for the five coral species with the highest number of effective spawning events (n), we analyzed the spawning frequency for each week of the most likely spawning months (Table 2). The earliest and the latest dates of spawning events per species that are registered in the Data Base are shown in Table 3. Spawning times are predicted relative to local sunset time, and the range of times are shown in Table 4. Taken together, this information is very useful for decision-making as to when and where to send divers with a higher probability of successful monitoring and capture of spawn.

Table 3. Extreme dates for spawning events registered in the Mexican Caribbean at 29 monitored sites for five reef-building species: A palmata (2007 – 2024, blue), D.labyrinthiformis (2007 – 2023, green), O. faveolata (2019 – 2024, magenta), O. annularis (2018 – 2024, pink) and P. strigosa (2009, 2014, 2017, 2018, 2020 – 2024, light orange).

A closer analysis of the data indicates that a species such as Acropora palmata, whose patches belong to the same genetic population along the Mexican Caribbean (Baums et al., 2005; Gómez Campo, 2015), vary in terms of spawning dates by as much as five to seven days depending on the location of the patch. Currently, due to the decline in healthy, living colonies, we are exploring reefs further North and South, where we had never monitored spawning to date. Eventually we hope to have more information that will allow us to predict spawning along the Mexican Caribbean considering this spatial variation.

2.2 Optimization of methods in assisted sexual reproduction

Another cornerstone in the restoration of corals has been the optimization of methods in assisted sexual reproduction (Figure 2). Sexual reproduction allows for the increase of genetic diversity and the adaptability of its offspring to environmental and climatic changes. Based on these principles, our objective is to establish reproductive and self-sufficient corals in the reef that constitute the basis of restored coral reefs.

Figure 2. Flow diagram of assisted coral reproduction, considering the crucial stages from cross-fertilization, larval culture, larval settlement and finally transfer to the reef.

For each species that we work with, adult reproductive colonies are selected from different sites from as many reefs as possible and monitored for spawning activity. Their gametes are captured in synchronous spawning events, and either cross fertilized in batch cultures where gametes from all colonies are mixed or crosses are made from specific pairs of colonies. Fertilization of batch cultures can be initiated on the boat, controlling some conditions such as the use of filtered (1 micron) and UV sterilized seawater maintained at 28 °C and using disinfected glass and plasticware. This is done mainly when the distance to the laboratory requires a journey of more than one hour. Otherwise, gametes can be transported to the laboratory prior to assisted fertilization. Specific crosses of colonies are required, it is preferable to perform this in a controlled environment, however, in a few cases we have recorded incompatibilities between gametes of some colonies resulting in low or no fertilization (Grosso-Becerra and Banaszak, unpublished data). Under normal conditions, fertilization success of over 90% is generally obtained. Fertilization success of Acropora palmata ranged from 90% to 99% (Mendoza Quiroz et al., 2023a), whereas that of Pseudodiploria strigosa was 95% in 2020 (Mendoza Quiroz et al., 2023b). Using assisted fertilization with batch cultures and/or small-scale experiments, we have annually produced settlers of five species of reef-building corals. The timeframe for each step is species specific, and more information can be found in Chamberland et al. (2023a, b, c).

The embryonic or larval development, up to the settlement of larvae on specialized artificial substrates can be carried out in in situ or ex situ cultures. In situ, mainly Coral Rearing In-situ Basins (CRIB’s as described in Miller et al., 2022) or direct seeding (Waters et al., 2025) are used. Along the Mexican Caribbean, exposure to waves and currents as well as the annual presence of Sargassum blooms decaying on the coastline (Banaszak, 2021) are not favorable for applying in situ early-stage culturing methods, due to the reduction in water quality (Banaszak, 2021). An alternative is to use ex situ larval cultures, which have been very successful as a strategy allowing small scale (up to 1.5 L cultures) to larger scale (57 L cultures) if water quality can be controlled. Small scale cultures are easily replicable and are used for experiments with less than 500 larvae per culture vessel. For larger scale optimization experiments, a hatchery system was designed and installed inside a laboratory with continuously controlled temperature and water quality conditions. The modular hatchery system consists of 28 incubators with a culture capacity of up to 2ml of concentrated eggs per incubator. Given the modular design, this system can and has been installed in remote sites around the Wider Caribbean using resources generally available in local hardware stores.

When the larvae develop and reach the settlement stage, artificial substrates, previously conditioned in the sea for two months, are introduced into the incubators. Once the larvae undergo metamorphosis to form a polyp with a mouth, the water conditions are changed to allow for the uptake of symbiotic algae (Symbiodiniaceae). At this stage the skeleton begins to form.

In general, under the controlled culture conditions we use, larval settlement success is high if the substrates are non-toxic and pre-conditioned, with yields ranging from 3.5% (A. palmata) to 6.3% (D. labyrinthiformis) as presented in Mendoza Quiroz et al. (2025), but can be as high as 22% (P. strigosa in Mendoza Quiroz et al., 2023b). Cement substrates tend to be more favorable for settlement than ceramic substrates or glazed tiles. However, there are exceptions. For example, Orbicella faveolata larvae prefer ceramic tiles to cement-based substrates. We have achieved settlement success of over 500 larvae per substrate, but we aim for much lower settlement values as eventually one settler will outcompete the others to occupy the substrate. By renewing the substrates in the culture bins daily or more often, a settlement success of 30 larvae per substrate is desirable. Post-settlement coral mortality, while a normal part of the life cycle of an r-strategist, is nevertheless a bottleneck that has required the study of the many factors that can cause failure of settlers to survive. Controlling algal overgrowth using herbivores, such as snails, that do not damage the coral polyps, and complementary feeding are crucial factors at this stage (Lippens and Banaszak, 2025).

Once the uptake of symbionts is confirmed, these coral settlers can now be transferred to an outdoor aquarium facility under natural solar radiation. Water quality, temperature and salinity are controlled, and the corals are fed daily. The 10,000 L aquarium system currently used can hold more than 3,000 substrates, each approximately 7x7x7 cm. An alternative to the intensive care that ex situ nurseries require is to install in situ nurseries that require less intensive care. In this case, monthly monitoring is strongly advised.

As of 2015, we have outplanted 65 times in 14 reef sites along the Mexican Caribbean, including 280,000 Acropora palmata, 68,000 Orbicella faveolata, 16,500 O. annularis, 39,000 Diploria labyrinthiformis and 6,300 Pseudodiploria strigosa settlers on artificial substrates. Some A. palmata colonies are 14 years old, have developed gametes and have released them in spawning events synchronously with wild colonies that inhabit the same reef site and have generated new recruits, thus demonstrating that colonies that were obtained from the methods we have developed and implemented are fertile and viable to contribute to the population of their species (Mendoza Quiroz et al., 2023a, b). Of the other four species of reef-building corals that we have produced in the laboratory, some are already 7 years old, and all recruits survived the Stony Coral Tissue Loss Disease (SCTLD; Mendoza Quiroz et al., 2023b) and other younger recruits survived the 2023 mass bleaching event that affected the Mexican Caribbean (Miller et al., 2024). It should be noted that the species planted in the last decade have experienced regional stressors that have put the adult coral population at critical risk such as coral diseases, such as SCTLD, thermal stress events, intense hurricanes, among others; and despite these stressors, most of the recruits planted have not been affected (Mendoza Quiroz et al., 2023b; Miller et al., 2024), demonstrating that these new recruits are more resilient than the colonies that gave rise to them and that they can be the baseline in the reef recovery. Our results indicate that using sexual recruits in restoration programs is a viable alternative to outplanting fragments derived from pruning adult colonies, which suffered high mortality levels during the 2023 heatwave (Birkart and Álvarez-Filip, 2025).

Despite these achievements, the long-term survival of recruits on the reef is a bottleneck that needs to be addressed from several aspects such as improving seeding strategies from the individuals to be planted, the size of the colonies and even the fusion of colonies to form chimeras prior to outplanting, as well as the implementation of methods that allow greater stability of the substrates on the reef in the long term and at the same time its easy implementation on a large scale (Mendoza Quiroz et al., 2025). Site selection is also a key factor in post-outplanting success and is an important area of ongoing research.

In most countries, permits must be obtained, or to at least collaborate with staff from an institution that manages the areas where collecting and outplanting will take place. We encourage engaging local governments and authorities involved in coral reef protection, such as park rangers, and include them in training and field activities.

2.3 Sperm cryopreservation

Cryopreservation is a method for long-term, very low-temperature maintenance of living cells and tissues for later use such that on thawing they can be reactivated in another geographic location to improve genetic diversity in the face of low spawning activity. The cryopreserved material, maintained under adequate conditions, can be viable for years, decades and possibly centuries. The implementation of this method in corals is aimed at conservation (Hagedorn et al., 2012a, b, 2017, 2019, 2021), species rescue (Hagedorn et al., 2021; Daly et al., 2022), and research (Cirino et al., 2021, 2022). However, its application will be efficient if the donor populations are healthy, genetically diverse and reproductively active (Hagedorn and Spindler, 2014; Hagedorn et al., 2016; Grosso-Becerra et al., 2021).

The Mexican Coral Biorepository, established in 2017 as part of ongoing coral reef restoration research, is one of only four cryopreservation banks of its kind worldwide and the only facility located in a low- to middle-income country. As of the current reporting period, the repository holds 1,221 cryopreserved accessions, representing 131 distinct genotypes from six species of reef-building corals listed on the IUCN Red List. These samples were collected during 78 summer spawning events across 34 reef sites (see Tables 5, 6). The main objectives of this gene bank are to: 1. Safeguard the genetic diversity of corals through the cryopreservation of their sperm; 2. Preserve the viability and fertilization potential of sperm; 3. Contribute to genetic recovery in the face of the loss of connectivity between populations and 4. Support conservation and restoration efforts for threatened species.

Table 5. Summary of coral accessions in the Mexican Biorepository by collection site through to 2024.

Table 6. Summary of accessions in the Mexican Coral Biorepository by genotype, collection year, and species.

An example of one of our achievements using cryopreservation is the case of the reef-building coral Diploria labyrinthiformis, a species that has been severely impacted due to Stony Coral Tissue Loss Disease (SCTLD). Of the patch of nine colonies that we were following for several years before the outbreak, seven of these have succumbed to this disease. Although the colonies are now dead, the cryopreserved sperm remains viable and is securely stored in the Mexican Coral Biorepository (Grosso-Becerra et al., 2021). The samples can be thawed and used in species rescue efforts to cross-fertilize with freshly spawned coral eggs (which cannot be cryopreserved due to their high lipid content), making it possible to produce genetically diverse cohorts of this species at any time in the future. This is an example of a long-term strategy designed to ensure that this, and other coral species in our repository, survive well into the future.

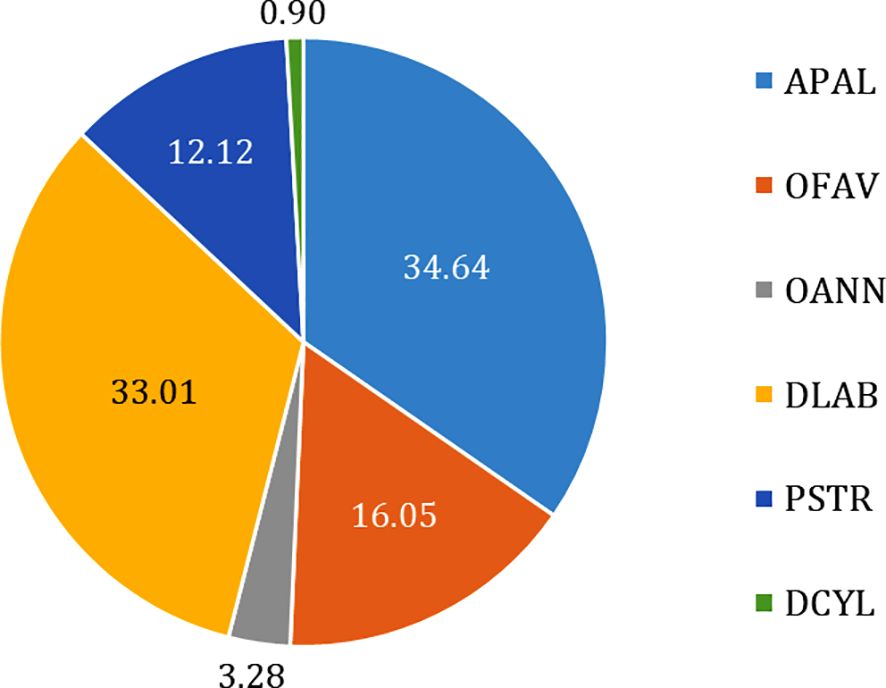

Six reef-building species are housed in our repository (Figure 3) with the most to least represented, in terms of number of samples being Acropora palmata (34.64%), Diploria labyrinthiformis (33.01%), Orbicella faveolata (16.05%), Pseudodiploria strigosa (12.12%), Orbicella annularis (3.28%) and Dendrogyra cylindrus (0.9%).

Figure 3. Accessions in the Mexican Coral Biorepository. Percentages are calculated based on the number of samples (cryovials) per species. Acropora palmata (APAL, light blue), Orbicella faveolata (OFAV, orange), O. annularis (OANN, grey), Diploria labyrinthiformis (DLAB, yellow), Pseudodiploria strigosa (PSTR, dark blue), Dendrogyra cylindrus (DCYL, green). Updated as of September 16, 2024.

The integrity of the gametes to be preserved is essential, however there are factors that put their viability at risk even prior to their cryopreservation. The detrimental effects of coral bleaching on reproductive parameters are well documented (Levitan et al., 2014; Hagedorn et al., 2016; Padilla-Gamiño et al., 2024). Specifically, bleaching events significantly reduce sperm motility and cryotolerance, thereby limiting their potential application in assisted reproductive efforts (Hagedorn et al., 2016; Daly et al., 2022). This presents a substantial challenge to cryopreservation-based strategies, particularly given the increasing incidence of mass coral bleaching events (Reimer et al., 2024). Given this scenario, we are also in the process of incorporating vitrification, an innovative technique in cryopreservation which can be applied to larvae (Cirino et al., 2019; Narida et al., 2023; Guo et al., 2024) and early-stage settlers, which does not rely on the collection of fresh gametes to complete the coral life cycle.

During the cryopreservation process, coral sperm are exposed to osmotic and thermal stress, which can compromise their viability and motility (Hagedorn et al., 2012a; 2014; 2021; Grosso-Becerra et al., 2021). However, several studies have demonstrated that cryopreserved sperm stored in cryobanks can retain fertilization competence for up to ten years (Hagedorn et al., 2017, 2021; Daly et al., 2022). Even sperm from diseased colonies that were cryopreserved maintained both viability and fertilization capacity (Grosso-Becerra and Banaszak, unpublished data).

Using cryopreserved sperm from the Mexican Coral Biorepository and assisted fertilization, we have produced recruits of Diploria labyrinthiformis, Acropora palmata, and Pseudodiploria strigosa, which show comparable development to those with fresh sperm. In controlled ex situ culture systems, no significant differences were observed in survival rates, early growth, or morphology during the initial post-settlement stages of Diploria labyrinthiformis (Grosso-Becerra et al., 2021). These findings confirm the functional viability of cryopreserved sperm in supporting early development and overall coral health. Because generating and maintaining these recruits is vital, ensuring their long-term survival remains a challenge, as they may be the only viable organisms available for future restoration efforts. Therefore, strategies aimed at improving post-settlement survival and performance both in ex situ systems and during in situ persistence focus on providing optimal nutrition to enhance their adaptability and resilience to environmental stressors.

Cryopreservation guarantees that coral reproductive materials are properly saved for future generations, especially if our restoration efforts fall short due to current or unexpected stressors like severe bleaching or new disease outbreaks. Our cryobank is a vital and valuable resource that will be accessible for future generations to grow corals once conditions are suitable for reef recovery. By cryopreserving sperm, we also help to increase genetic diversity, benefiting both local and distant populations now and in the future—be it one year, ten years, or even centuries later, when conditions improve. This approach is similar to the Svalbard Global Seed Vault in Norway. We aim to preserve coral gametes and larvae as a genetic resource and legacy for future generations, with the hope that future oceans will eventually recover.

Collecting gametes from different reefs with distinct environmental conditions requires a significant effort in terms of both human and economic resources, and timing is always of the essence, given that spawning events only occur on one or two nights a year for each species. We have collected from a variety of reef environments (considering species depth distribution, different light and wave energy environments, latitudes and adequate distance between colonies to avoid sampling clones) to ensure representation and allelic diversity in the repository. This has required substantial amounts of funding due to the complex infrastructure involved, which we have obtained from multiple national and international organizations and agencies.

2.4 Knowledge sharing and capacity building

One of the aims of our restoration program is to promote the establishment of successful restoration programs around the Wider Caribbean through mentoring, motivation and empowerment. The United Nations defines capacity building as “the process of developing and strengthening the skills, instincts, abilities, processes and resources that organizations and communities need to survive, adapt, and thrive in a fast-changing world” (www.un.org). This is different from traditional training, where the goal is to teach a person a particular skill. For example: you can teach a person to fish through training, but providing the knowledge of when to fish or not, where and where not to fish is different and requires applying the given information to the local conditions. It also empowers local communities to continue the efforts long after the capacity building is completed. We believe that this approach is more useful over the long-term to sustainably restore corals reefs.

Our goal is that participants in our capacity building program attain enough knowledge to sustain their organizations from within over time and to increase their chances of success. We teach them but also learn from them, and together we build upon the collective experiences to find viable and innovative, context-appropriate solutions to improve coral restoration methods custom designed for the local conditions. When engaging with communities, it can be advantageous to work alongside civil society organizations that have previously been involved with the communities and have established relationships based on trust. Capacity building can be adapted to different scenarios depending on available resources. As an example, in the most basic scenario where collection permits are not available, spawning monitoring can be done and a database initiated. An intermediate level, where permits are available, but infrastructure is limited could involve gamete collection followed by assisted fertilization for 15 to 20 minutes and release of the embryos into the ocean. At an advanced level, gamete collection followed by production and maintenance of sexual recruits in ex situ or in situ nurseries can be applied when infrastructure is available.

To date, we have trained approximately 260 people from 23 Caribbean countries, including Colombia, the Dominican Republic and Cuba, by offering over 20 workshops and courses including basic training and advanced methods in coral sexual reproduction and restoration (Figure 4). We do not charge course fees and when possible, find funding to cover all expenses. An additional key to the success of these workshops and courses, aside from their content, is that we teach them in English or Spanish thereby reaching a much wider audience throughout the Caribbean.

Figure 4. A Google Earth map (Data SIO, NOAA, U. S. Navy, NGA, GEBCO © 2018 Google) of the Caribbean Sea showing the country of origin of participants trained in workshops and capacity building courses led by Coralium lab. http://www.google.com/earth/index.html (Accessed September 9, 2018).

After the recent mass bleaching event in the Caribbean, many stakeholders are interested in introducing sexual reproduction into their restoration programs. We start by providing information on the simplest methods: from how to accurately predict coral spawning, collect the gametes and fertilize them whilst still in the boat and then to release the embryos, thus increasing the chances of successful recruitment by assisting in the fertilization process. This requires no land-based infrastructure but does require access to dive boats and equipment. Many Caribbean nations have dive shops to service the tourist industry as well as owners and staff are often keen to be involved in the night-time spawning activities. This is an example of a low cost, low technology method that can be easily taught and is another key feature of the research we undertake. As the local marine park managers gain experience and, if they have access to infrastructure (such as private or public aquaria), we teach them more advanced techniques to develop and maintain a successful restoration program.

We have formed and continue to form well trained and knowledgeable technicians who are now greatly sought after by restoration programs in other countries requesting aid in the early phases.

During the establishment of this restoration program we have learned a number of lessons. We have presented them for each of the four cornerstones in Table 7, to aid new practitioners in implementing these methods into their own programs. As a guide, Table 8 indicates relative costs and recommended actions depending on the local situation, in terms of level of access to infrastructure.

Table 8. Relative costs and recommended actions depending on level of access to infrastructure on a local level.

We need to restore corals and coral reefs before there are no corals left, and we hope that by sharing this information freely with others we can increase the chances that corals and coral reefs are maintained for future generations.

Data availability statement

The datasets analyzed in this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation. Requests to access this data should be directed to AB, YmFuYXN6YWtAY21hcmwudW5hbS5teA==.

Ethics statement

The manuscript presents research on animals that do not require ethical approval for their study.

Author contributions

AB: Methodology, Conceptualization, Validation, Investigation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Resources, Writing – original draft, Funding acquisition, Project administration. VF-R: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Investigation, Validation, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. SM: Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Validation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Data curation. MG-B: Data curation, Validation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Investigation.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. Funding for research and technical assistance was provided by SECORE International, Fundación Carlos Slim, CORDAP, CONAHCYT, Alianza World Wildlife Fund - Fundación Carlos Slim, CONANP, CONABIO, Quintana Roo State Government, MARFund, Benito Juarez Municipal Government (Quintana Roo). Cost of the article processing fee was paid by the Instituto de Ciencias del Mar y Limnología, UNAM.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Edén Magaña for generating Figure 1. We also thank all of the students, volunteers and technicians who have contributed to developing techniques and researching different aspects of coral reproduction and reef restoration.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Banaszak A. T. (2021). “Contamination of Coral Reefs in the Mexican Caribbean,” in Anthropogenic Pollution of Aquatic Ecosystems. Eds. Häder D. P., Helbling E. W., and Villafañe V. E. (Springer, Cham). doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-75602-4_6

Banaszak A. T., Marhaver K., Hartmann A. C., Miller M. W., Albright R., Hagedorn M., et al. (2023). Applying coral breeding to reef restoration: best practices, knowledge gaps, and priority actions in a rapidly evolving field. Restor. Ecol. 31, e13913. doi: 10.1111/rec.13913

Banaszak A. T., Mendoza Quiroz S., Francisco-Ramos V., and Grosso-Becerra M. V. (2025). Coral Spawning Prediction Calendar for the Mexican Caribbean 2025 (Mexico: CORALIUM-UNAM). Available online at: http://132.248.121.70/Coral/CalendarioI2025.pdf (Accessed August 17, 2025).

Baums I. B., Miller M. W., and Hellberg M. E. (2005). Regionally isolated populations of an imperiled Caribbean coral, Acropora palmata. Mol. Ecol. 14, 1377–1390. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02489.x

Birkart L. V. and Álvarez-Filip L. (2025). 2023 global heatwave causes mass mortality of a keystone coral on shallow western atlantic reefs. iScience 28, 5253072. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.5253072

Burke L., Reytar K., Spalding M., and Perry A. (2011). Reef at Risk Revisited (Washington: World Resources Institute).

Chamberland V. F., Latijnhouwers K. R. W., Marhaver K. L., O’Neil K., Vermeij M. J. A., Geertsma R. C., et al. (2023b). Diploria labyrinthiformis in Coral Breeding Reference Sheets on the Reproductive Biology, Early Life History, and Larval Propagation of Caribbean Corals (Coral Restoration Consortium), 6 pp.

Chamberland V. F., Mendoza Quiroz S., Bennett M.-J., Banaszak A. T., Marhaver K. L., Miller M. W., et al. (2023c). Orbicella faveolata in Coral Breeding Reference Sheets on the Reproductive Biology, Early Life History, and Larval Propagation of Caribbean Corals (Coral Restoration Consortium), 6 pp.

Chamberland V. F., Mendoza Quiroz S., Bennett M.-J., Banaszak A. T., Miller M. W., Marhaver K. L., et al. (2023a). Acropora palmata in Coral Breeding Reference Sheets on the Reproductive Biology, Early Life History, and Larval Propagation of Caribbean Corals (Coral Restoration Consortium), 6 pp.

Cirino L., Tsai S., Wang L. H., Hsieh W. C., Huang C. L., Wen Z. H., et al. (2022). Effects of cryopreservation on the ultrastructure of coral larvae. Coral Reefs 41, 131–147. doi: 10.1007/s00338-021-02209-4

Cirino L., Tsai S., Wen Z. H., Wang L. H., Chen H. K., Cheng J. O., et al. (2021). Lipid profiling in chilled coral larvae. Cryobiology 102, 56–67. doi: 10.1016/j.cryobiol.2021.07.012

Cirino L., Wen Z. H., Hsieh K., Huang C. L., Leong Q. L., Wang L. H., et al. (2019). First instance of settlement by cryopreserved coral larvae in symbiotic association with dinoflagellates. Sci. Rep. 9, 18851. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-55374-6

Cramer K. L., Jackson J. B. C., Donovan M. K., Greenstein B. J., Korpanty C. A., Cook G. M., et al. (2020). Widespread loss of Caribbean acroporid corals was underway before coral bleaching and disease outbreaks. Sci. Adv. 6, eaax9395. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aax9395

Daly J., Hobbs. R. J., Zuchowicz. N., O’Brien J. K., Bouwmeester J., Bay L., et al. (2022). Cryopreservation can assist gene flow on the Great Barrier Reef. Coral Reefs 41, 455–462. doi: 10.1007/s00338-021-02202-x

Donovan M. K., Burkepile D. E., Kratochwill C., Shlesinger T., Sully S., Oliver T., et al. (2021). Local conditions magnify coral loss after marine heatwaves. Science 372, 977–980. doi: 10.1126/science.abd9464

Gardner T. A., Côté I. M., Gill J. A., Grant A., and Watkinson A. R. (2003). Long-term region-wide declines in Caribbean corals. Science 301, 958–960. doi: 10.1126/science.1086050

Gómez I., Silva R., Lithgow D., Rodríguez J., Banaszak A. T., and Van Tussenbroek B. (2022). A review of disturbances to the ecosystems of the Mexican Caribbean, their causes and consequences. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 10, 644. doi: 10.3390/jmse10050644

Gómez Campo K. (2015). Variabilidad genética del coral Acropora palmata (Lamarck 1816) en el Caribe mexicano, un análisis espacial a microescala (UNAM). Available online at: https://tesiunam.dgb.unam.mx/F/I6958N8HHL6VG7RM54PHRP89M5NCG4J81DJ3K82VYU1PH7MYER-13084?func=short-0-b&set_number=012278&request=WRD%20%3D%20%28%20Kelly%20Gomez%20Campo%20%29 (Accessed August 17, 2025).

Grosso-Becerra M. V., Mendoza-Quiroz S., Maldonado E., and Banaszak A. T. (2021). Cryopreservation of sperm from the brain coral Diploria labyrinthiformis as a strategy to face the loss of corals in the Caribbean. Coral Reefs 40, 937–950. doi: 10.1007/s00338-021-02098-7

Guo Z., Zuchowicz N., Bouwmeester J., Joshi A. S., Neisch A. L., Smith K., et al. (2024). Conduction-Dominated Cryomesh for organism vitrification. Adv. Sci. (Weinh) 11, e2303317. doi: 10.1002/advs.202303317

Gutierrez L., Polidoro B., Obura D., Cabada- Blanco F., Linardich C., Pettersson E., et al. (2024). Half of Atlantic reef-building corals at elevated risk of extinction due to climate change and other threats. PLoS One 19, e0309354. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0309354

Hagedorn M., Carter V. L., Henley E. M., van Oppen M. J. H., Hobbs R., and Spindler R. E. (2017). Producing coral offspring with cryopreserved sperm: A tool for coral reef restoration. Sci. Rep. 7, 14432. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-14644-x

Hagedorn M., Carter V. L., Lager C., Camperio Ciani J. F., Dygert A. N., Schleiger R. D., et al. (2016). Potential bleaching effects on coral reproduction. Reproduction Fertility Dev. 28, 1061–1011. doi: 10.1071/RD15526

Hagedorn M., Carter V., Martorana K., Paresa M. K., Acker J., Baums I. B., et al. (2012a). Preserving and using germplasm and dissociated embryonic cells for conserving Caribbean and Pacific coral. PloS One 7, e33354. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033354

Hagedorn M., Page C. A., O'Neil K. L., Flores D. M., Tichy L., Conn T., et al. (2021). Assisted gene flow using cryopreserved sperm in critically endangered coral. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 118, e2110559118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2110559118

Hagedorn M. and Spindler R. (2014). “The Reality, Use and Potential for Cryopreservation of Coral Reefs,” in Reproductive Sciences in Animal Conservation. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology, vol. 753 . Eds. Holt W., Brown J., and Comizzoli P. (Springer, New York, NY). doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-0820-2_13

Hagedorn M., Spindler R., and Daly J. (2019). Cryopreservation as a tool for reef restoration advances in experimental medicine and biology. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. (Springer, Cham). 1200, 489–505. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-23633-5_16

Hagedorn M., van Oppen M. J., Carter V., Henley M., Abrego D., Puill-Stephan E., et al. (2012b). First frozen repository for the Great Barrier Reef coral created. Cryobiology 65, 157–158. doi: 10.1016/j.cryobiol.2012.05.008

Hein M. Y., Vardi T., Shaver E. C., Pioch S., Boström-Einarsson L., Ahmed M., et al. (2021). Perspectives on the use of coral reef restoration as a strategy to support and improve reef ecosystem services. Front. Mar. Sci. 8, 618303. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.618303

Hughes T. P., Anderson K. D., Connolly S. R., Heron S. F., Kerry J. T., Lough J. M., et al. (2018). Spatial and temporal patterns of mass bleaching of corals in the Anthropocene. Science 359, 80–83. doi: 10.1126/science.aan8048

Jackson J. B. C., Donovan K. L., Cramer V. V., and Lam M. K. (Eds.) (2014). Status and Trends of Caribbean Coral Reefs 1970-2012. Global Coral Reef Monitoring Network (Gland, Switzerland: IUCN).

Kumaraswamy S. and Udayakumar M. (2011). Biodiversity banking: a strategic conservation mechanism. Biodiversity Conserv. 20, 1155–1165. doi: 10.1007/s10531-011-0020-5

Levitan D. R., Boudreau W., Jara J., and Knowlton N. (2014). Long-term reduced spawning in Orbicella coral species due to temperature stress. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 515, 1–10. doi: 10.3354/meps11063

Lippens C. and Banaszak A. T. (2025). Integrating grazing and food supplementation in coral restoration to enhance settler survival and growth. Restor. Ecol. 33, e14303. doi: 10.1111/rec.14303

MEA (2005). Millenium ecosystem assessment: Ecosystems and human well-being - synthesis (Washington, DC: Millenium Ecosystem Assessment).

Mendoza Quiroz S., Banaszak A. T., McGonigle M. L., Bickel A. R., Guest J. R., and Miller M. W. (2025). Influence of attachment techniques on coral seeding unit deployment cost and performance. Restor. Ecol. 33, 1–9. doi: 10.1111/rec.70090

Mendoza Quiroz S., Beltrán Torres A. U., Muñoz Villareal D., Tecalco Rentería R., Grosso-Becerra M. V., and Banaszak A. T. (2023a). Long-term survival, growth, and reproduction of Acropora palmata sexual recruits outplanted onto two Mexican Caribbean reefs. PeerJ 11, e15813. doi: 10.7717/peerj.15813

Mendoza Quiroz S., Tecalco Renteria R., Ramírez Tapia G. G., Miller M. W., Grosso-Becerra M. V., and Banaszak A. T. (2023b). Coral affected by stony coral tissue loss disease can produce viable offspring. PeerJ 11, e15519. doi: 10.7717/peerj.15519

Miller M. W., Latijnhouwers K. R. W., Bickel A., Mendoza-Quiroz S., Schick M., Burton K., et al. (2022). Settlement yields in large-scale in situ culture of Caribbean coral larvae for restoration. Restor. Ecol. 30, e13512. doi: 10.1111/rec.13512

Miller M. W., Mendoza Quiroz S., Lachs L., Banaszak A. T., Chamberland V. F., Guest J., et al. (2024). Assisted sexual coral recruits show high thermal tolerance to the 2023 Caribbean mass bleaching event. PLoS One 19, e0309719. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0309719

Moberg F. and Folke C. (1999). Ecological goods and services of coral reef ecosystems. Ecol. Econ 29, 215–233. doi: 10.1016/S0921-8009(99)00009-9

Narida A., Tsai S., Hsieh W.-C., Wen Z.-H., Wang L.-H., Huang C.-L., et al. (2023). First successful production of adult corals derived from cryopreserved larvae. Front. Mar. Sci. 10. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2023.1172102

Padilla-Gamiño J. L., Timmins-Schiffman E., Lenz E. A., White S. J., Axworthy J., Potter A., et al. (2024). Coral long-term recovery after bleaching: implications for sexual reproduction and physiology. bioRxiv. doi: 10.1101/2024.04.09.588789

Reimer J. D., Peixoto R. S., Davies S. W., Traylor-Knowles N., Short M. L., Cabral-Tena R. A., et al. (2024). The Fourth Global Coral Bleaching Event: Where do we go from here? Coral Reefs 43, 1121–1125. doi: 10.1007/s00338-024-02504-w

Keywords: coral spawning timing, assisted sexual reproduction, sperm cryopreservation, knowledge sharing, capacity building

Citation: Banaszak AT, Francisco-Ramos V, Mendoza Quiroz S and Grosso-Becerra MV (2025) Strategies using sexual reproduction to conserve and restore corals: a case study from the Mexican Caribbean. Front. Ecol. Evol. 13:1688176. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2025.1688176

Received: 18 August 2025; Accepted: 19 November 2025; Revised: 15 November 2025;

Published: 16 December 2025.

Edited by:

Carlos Prada, University of Rhode Island, United StatesReviewed by:

Violeta Martinez-Castillo, Universidad Autónoma de Baja California Sur, MexicoMaria Geovana Leon Pech, IT Chetumal, Mexico

Copyright © 2025 Banaszak, Francisco-Ramos, Mendoza Quiroz and Grosso-Becerra. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Anastazia T. Banaszak, YmFuYXN6YWtAY21hcmwudW5hbS5teA==

†ORCID: Vanessa Francisco-Ramos, orcid.org/0000-0002-7736-7746

Anastazia T. Banaszak

Anastazia T. Banaszak Vanessa Francisco-Ramos

Vanessa Francisco-Ramos Sandra Mendoza Quiroz

Sandra Mendoza Quiroz María Victoria Grosso-Becerra

María Victoria Grosso-Becerra